How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

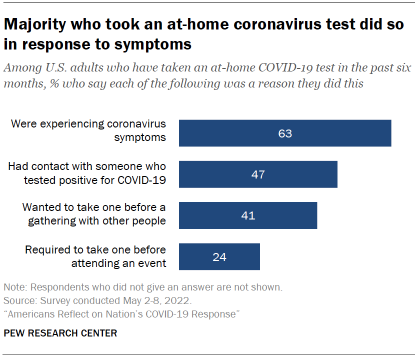

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Takeaways from the ncaa’s settlement.

Laura Mannweiler May 24, 2024

New Best Engineering Rankings June 18

Robert Morse and Eric Brooks May 24, 2024

Premedical Programs: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

10 Destination West Coast College Towns

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Federal vs. Private Parent Student Loans

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

The complexity of managing COVID-19: How important is good governance?

- Download the essay

Subscribe to Global Connection

Alaka m. basu , amb alaka m. basu professor, department of global development - cornell university, senior fellow - united nations foundation kaushik basu , and kaushik basu nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development @kaushikcbasu jose maria u. tapia jmut jose maria u. tapia student - cornell university.

November 17, 2020

- 13 min read

This essay is part of “ Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 world ,” a collection of 12 essays presenting new ideas to guide policies and shape debates in a post-COVID-19 world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacy of public health systems worldwide, casting a shadow that we could not have imagined even a year ago. As the fog of confusion lifts and we begin to understand the rudiments of how the virus behaves, the end of the pandemic is nowhere in sight. The number of cases and the deaths continue to rise. The latter breached the 1 million mark a few weeks ago and it looks likely now that, in terms of severity, this pandemic will surpass the Asian Flu of 1957-58 and the Hong Kong Flu of 1968-69.

Moreover, a parallel problem may well exceed the direct death toll from the virus. We are referring to the growing economic crises globally, and the prospect that these may hit emerging economies especially hard.

The economic fall-out is not entirely the direct outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic but a result of how we have responded to it—what measures governments took and how ordinary people, workers, and firms reacted to the crisis. The government activism to contain the virus that we saw this time exceeds that in previous such crises, which may have dampened the spread of the COVID-19 but has extracted a toll from the economy.

This essay takes stock of the policies adopted by governments in emerging economies, and what effect these governance strategies may have had, and then speculates about what the future is likely to look like and what we may do here on.

Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market.

It is becoming clear that the scramble among several emerging economies to imitate and outdo European and North American countries was a mistake. We get a glimpse of this by considering two nations continents apart, the economies of which have been among the hardest hit in the world, namely, Peru and India. During the second quarter of 2020, Peru saw an annual growth of -30.2 percent and India -23.9 percent. From the global Q2 data that have emerged thus far, Peru and India are among the four slowest growing economies in the world. Along with U.K and Tunisia these are the only nations that lost more than 20 percent of their GDP. 1

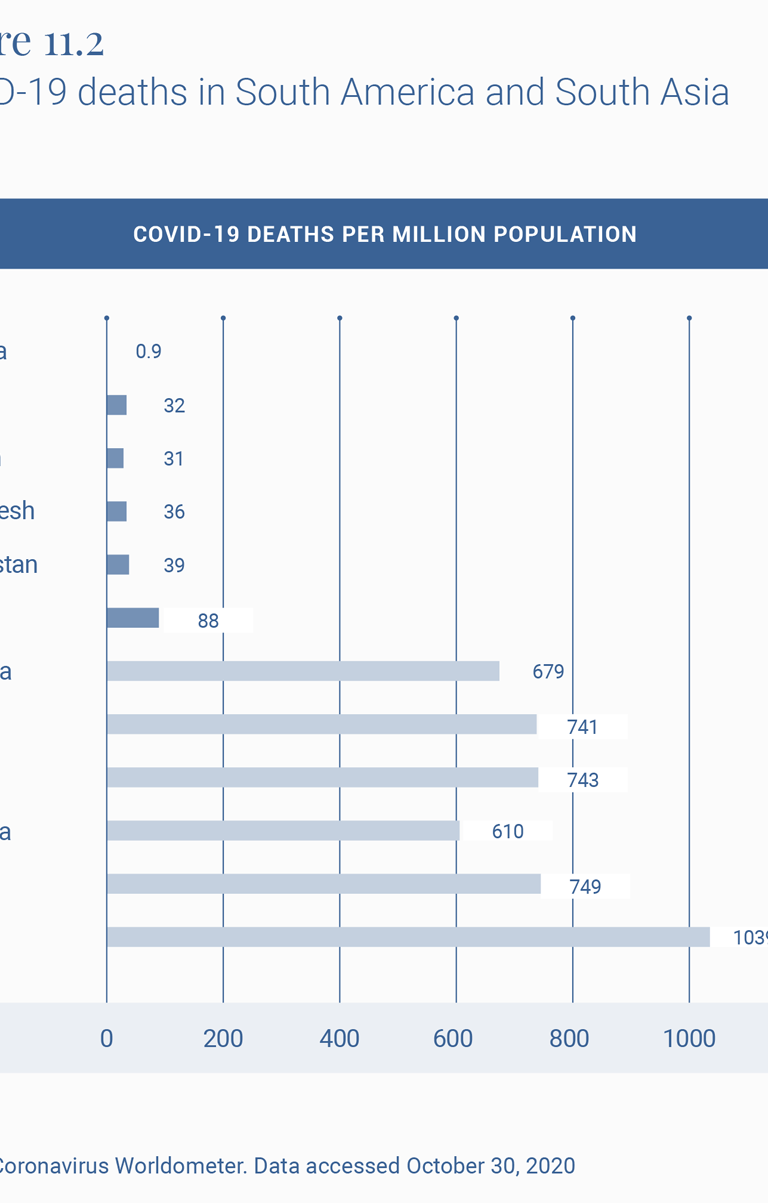

COVID-19-related mortality statistics, and, in particular, the Crude Mortality Rate (CMR), however imperfect, are the most telling indicator of the comparative scale of the pandemic in different countries. At first glance, from the end of October 2020, Peru, with 1039 COVID-19 deaths per million population looks bad by any standard and much worse than India with 88. Peru’s CMR is currently among the highest reported globally.

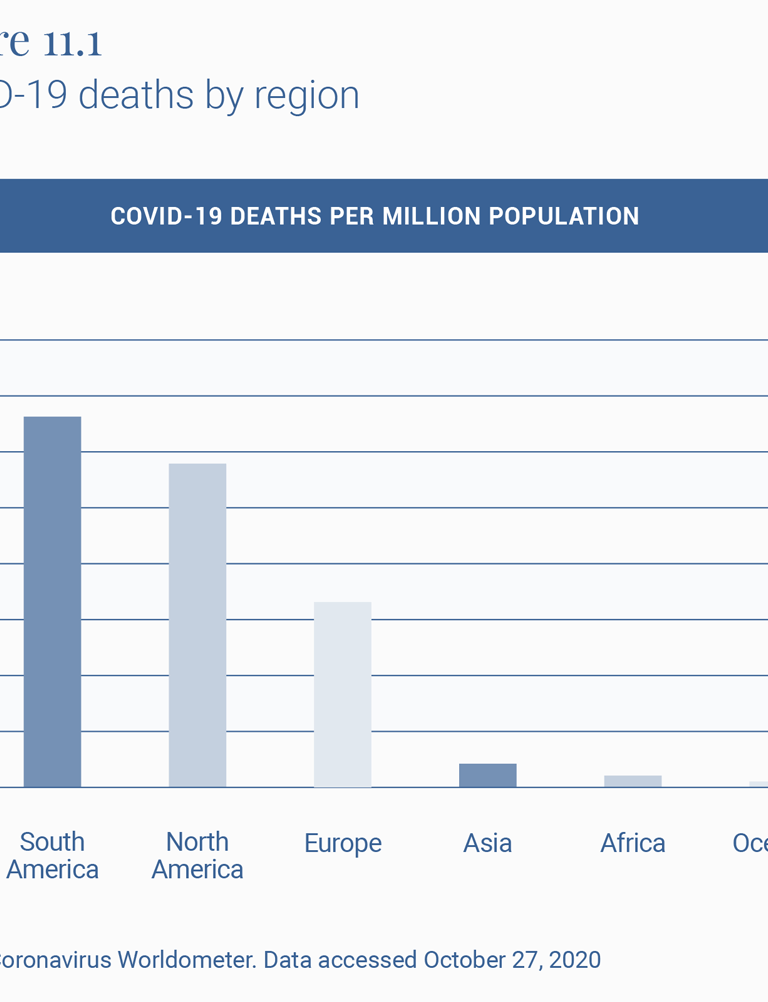

However, both Peru and India need to be placed in regional perspective. For reasons that are likely to do with the history of past diseases, there are striking regional differences in the lethality of the virus (Figure 11.1). South America is worse hit than any other world region, and Asia and Africa seem to have got it relatively lightly, in contrast to Europe and America. The stark regional difference cries out for more epidemiological analysis. But even as we await that, these are differences that cannot be ignored.

To understand the effect of policy interventions, it is therefore important to look at how these countries fare within their own regions, which have had similar histories of illnesses and viruses (Figure 11.2). Both Peru and India do much worse than the neighbors with whom they largely share their social, economic, ecological and demographic features. Peru’s COVID-19 mortality rate per million population, or CMR, of 1039 is ahead of the second highest, Brazil at 749, and almost twice that of Argentina at 679.

Similarly, India at 88 compares well with Europe and the U.S., as does virtually all of Asia and Africa, but is doing much worse than its neighbors, with the second worst country in the region, Afghanistan, experiencing less than half the death rate of India.

The official Indian statement that up to 78,000 deaths 2 were averted by the lockdown has been criticized 3 for its assumptions. A more reasonable exercise is to estimate the excess deaths experienced by a country that breaks away from the pattern of its regional neighbors. So, for example, if India had experienced Afghanistan’s COVID-19 mortality rate, it would by now have had 54,112 deaths. And if it had the rate reported by Bangladesh, it would have had 49,950 deaths from COVID-19 today. In other words, more than half its current toll of some 122,099 COVID-19 deaths would have been avoided if it had experienced the same virus hit as its neighbors.

What might explain this outlier experience of COVID-19 CMRs and economic downslide in India and Peru? If the regional background conditions are broadly similar, one is left to ask if it is in fact the policy response that differed markedly and might account for these relatively poor outcomes.

Peru and India have performed poorly in terms of GDP growth rate in Q2 2020 among the countries displayed in Table 2, and given that both these countries are often treated as case studies of strong governance, this draws attention to the fact that there may be a dissonance between strong governance and good governance.

The turnaround for India has been especially surprising, given that until a few years ago it was among the three fastest growing economies in the world. The slowdown began in 2016, though the sharp downturn, sharper than virtually all other countries, occurred after the lockdown.

On the COVID-19 policy front, both India and Peru have become known for what the Oxford University’s COVID Policy Tracker 4 calls the “stringency” of the government’s response to the epidemic. At 8 pm on March 24, 2020, the Indian government announced, with four hours’ notice, a complete nationwide shutdown. Virtually all movement outside the perimeter of one’s home was officially sought to be brought to a standstill. Naturally, as described in several papers, such as that of Ray and Subramanian, 5 this meant that most economic life also came to a sudden standstill, which in turn meant that hundreds of millions of workers in the informal, as well as more marginally formal sectors, lost their livelihoods.

In addition, tens of millions of these workers, being migrant workers in places far-flung from their original homes, also lost their temporary homes and their savings with these lost livelihoods, so that the only safe space that beckoned them was their place of origin in small towns and villages often hundreds of miles away from their places of work.

After a few weeks of precarious living in their migrant destinations, they set off, on foot since trains and buses had been stopped, for these towns and villages, creating a “lockdown and scatter” that spread the virus from the city to the town and the town to the village. Indeed, “lockdown” is a bit of a misnomer for what happened in India, since over 20 million people did exactly the opposite of what one does in a lockdown. Thus India had a strange combination of lockdown some and scatter the rest, like in no other country. They spilled out and scattered in ways they would otherwise not do. It is not surprising that the infection, which was marginally present in rural areas (23 percent in April), now makes up some 54 percent of all cases in India. 6

In Peru too, the lockdown was sudden, nationwide, long drawn out and stringent. 7 Jobs were lost, financial aid was difficult to disburse, migrant workers were forced to return home, and the virus has now spread to all parts of the country with death rates from it surpassing almost every other part of the world.

As an aside, to think about ways of implementing lockdowns that are less stringent and geographically as well as functionally less total, an example from yet another continent is instructive. Ethiopia, with a COVID-19 death rate of 13 per million population seems to have bettered the already relatively low African rate of 31 in Table 1. 8

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability.

The way forward

We next move from the immediate crisis to the medium term. Where is the world headed and how should we deal with the new world? Arguably, that two sectors that will emerge larger and stronger in the post-pandemic world are: digital technology and outsourcing, and healthcare and pharmaceuticals.

The last 9 months of the pandemic have been a huge training ground for people in the use of digital technology—Zoom, WebEx, digital finance, and many others. This learning-by-doing exercise is likely to give a big boost to outsourcing, which has the potential to help countries like India, the Philippines, and South Africa.

Globalization may see a short-run retreat but, we believe, it will come back with a vengeance. Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market. This realization will make most countries reverse their knee-jerk anti-globalization; and the ones that do not will cease to be important global players. Either way, globalization will be back on track and with a much greater amount of outsourcing.

To return, more critically this time, to our earlier aside on Ethiopia, its historical and contemporary record on tampering with internet connectivity 9 in an attempt to muzzle inter-ethnic tensions and political dissent will not serve it well in such a post-pandemic scenario. This is a useful reminder for all emerging market economies.

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability. This could divert some demand from luxury goods to better health, and what is best described as “creative consumption”: art, music, and culture. 10 The former will mean much larger healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors.

But to take advantage of these new opportunities, nations will need to navigate the current predicament so that they have a viable economy once the pandemic passes. Thus it is important to be able to control the pandemic while keeping the economy open. There is some emerging literature 11 on this, but much more is needed. This is a governance challenge of a kind rarely faced, because the pandemic has disrupted normal markets and there is need, at least in the short run, for governments to step in to fill the caveat.

Emerging economies will have to devise novel governance strategies for doing this double duty of tamping down on new infections without strident controls on economic behavior and without blindly imitating Europe and America.

Here is an example. One interesting opportunity amidst this chaos is to tap into the “resource” of those who have already had COVID-19 and are immune, even if only in the short-term—we still have no definitive evidence on the length of acquired immunity. These people can be offered a high salary to work in sectors that require physical interaction with others. This will help keep supply chains unbroken. Normally, the market would have on its own caused such a salary increase but in this case, the main benefit of marshaling this labor force is on the aggregate economy and GDP and therefore is a classic case of positive externality, which the free market does not adequately reward. It is more a challenge of governance. As with most economic policy, this will need careful research and design before being implemented. We have to be aware that a policy like this will come with its risk of bribery and corruption. There is also the moral hazard challenge of poor people choosing to get COVID-19 in order to qualify for these special jobs. Safeguards will be needed against these risks. But we believe that any government that succeeds in implementing an intelligently-designed intervention to draw on this huge, under-utilized resource can have a big, positive impact on the economy 12 .

This is just one idea. We must innovate in different ways to survive the crisis and then have the ability to navigate the new world that will emerge, hopefully in the not too distant future.

Related Content

Emiliana Vegas, Rebecca Winthrop

Homi Kharas, John W. McArthur

Anthony F. Pipa, Max Bouchet

Note: We are grateful for financial support from Cornell University’s Hatfield Fund for the research associated with this paper. We also wish to express our gratitude to Homi Kharas for many suggestions and David Batcheck for generous editorial help.

- “GDP Annual Growth Rate – Forecast 2020-2022,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/forecast/gdp-annual-growth-rate.

- “Government Cites Various Statistical Models, Says Averted Between 1.4 Million-2.9 Million Cases Due To Lockdown,” Business World, May 23, 2020, www.businessworld.in/article/Government-Cites-Various-Statistical-Models-Says-Averted-Between-1-4-million-2-9-million-Cases-Due-To-Lockdown/23-05-2020-193002/.

- Suvrat Raju, “Did the Indian lockdown avert deaths?” medRxiv , July 5, 2020, https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr183813#A1.

- “COVID Policy Tracker,” Oxford University, https://github.com/OxCGRT/covid-policy-tracker t.

- Debraj Ray and S. Subramanian, “India’s Lockdown: An Interim Report,” NBER Working Paper, May 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27282.

- Gopika Gopakumar and Shayan Ghosh, “Rural recovery could slow down as cases rise, says Ghosh,” Mint, August 19, 2020, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/rural-recovery-could-slow-down-as-cases-rise-says-ghosh-11597801644015.html.

- Pierina Pighi Bel and Jake Horton, “Coronavirus: What’s happening in Peru?,” BBC, July 9, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-53150808.

- “No lockdown, few ventilators, but Ethiopia is beating Covid-19,” Financial Times, May 27, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/7c6327ca-a00b-11ea-b65d-489c67b0d85d.

- Cara Anna, “Ethiopia enters 3rd week of internet shutdown after unrest,” Washington Post, July 14, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/ethiopia-enters-3rd-week-of-internet-shutdown-after-unrest/2020/07/14/4699c400-c5d6-11ea-a825-8722004e4150_story.html.

- Patrick Kabanda, The Creative Wealth of Nations: Can the Arts Advance Development? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Guanlin Li et al, “Disease-dependent interaction policies to support health and economic outcomes during the COVID-19 epidemic,” medRxiv, August 2020, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.24.20180752v3.

- For helpful discussion concerning this idea, we are grateful to Turab Hussain, Daksh Walia and Mehr-un-Nisa, during a seminar of South Asian Economics Students’ Meet (SAESM).

Global Economy and Development

The Brookings Institution, Washington DC

3:00 pm - 4:00 pm EDT

Robin Brooks

May 23, 2024

Gayle E. Smith

May 21, 2024

- Open access

- Published: 04 February 2022

Analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons towards a more effective response to public health emergencies

- Yibeltal Assefa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2393-1492 1 ,

- Charles F. Gilks 1 ,

- Simon Reid 1 ,

- Remco van de Pas 2 ,

- Dereje Gedle Gete 1 &

- Wim Van Damme 2

Globalization and Health volume 18 , Article number: 10 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

36 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

The pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a timely reminder of the nature and impact of Public Health Emergencies of International Concern. As of 12 January 2022, there were over 314 million cases and over 5.5 million deaths notified since the start of the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic takes variable shapes and forms, in terms of cases and deaths, in different regions and countries of the world. The objective of this study is to analyse the variable expression of COVID-19 pandemic so that lessons can be learned towards an effective public health emergency response.

We conducted a mixed-methods study to understand the heterogeneity of cases and deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Correlation analysis and scatter plot were employed for the quantitative data. We used Spearman’s correlation analysis to determine relationship strength between cases and deaths and socio-economic and health systems. We organized qualitative information from the literature and conducted a thematic analysis to recognize patterns of cases and deaths and explain the findings from the quantitative data.

We have found that regions and countries with high human development index have higher cases and deaths per million population due to COVID-19. This is due to international connectedness and mobility of their population related to trade and tourism, and their vulnerability related to older populations and higher rates of non-communicable diseases. We have also identified that the burden of the pandemic is also variable among high- and middle-income countries due to differences in the governance of the pandemic, fragmentation of health systems, and socio-economic inequities.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that every country remains vulnerable to public health emergencies. The aspiration towards a healthier and safer society requires that countries develop and implement a coherent and context-specific national strategy, improve governance of public health emergencies, build the capacity of their (public) health systems, minimize fragmentation, and tackle upstream structural issues, including socio-economic inequities. This is possible through a primary health care approach, which ensures provision of universal and equitable promotive, preventive and curative services, through whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches.

The pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a timely reminder of the nature and impact of emerging infectious diseases that become Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [ 1 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic takes variable shapes and forms in how it affects communities in different regions and countries [ 2 , 3 ]. As of 12 January, 2022, there were over 314 million cases and over 5.5 million deaths notified around the globe since the start of the pandemic. The number of cases per million population ranged from 7410 in Africa to 131,730 in Europe while the number of deaths per million population ranged from 110 in Oceania to 2740 in South America. Case-fatality rates (CFRs) ranged from 0.3% in Oceania to 2.9% in South America [ 4 , 5 ]. Regions and countries with high human development index (HDI), which is a composite index of life expectancy, education, and per capita income indicators [ 6 ], are affected by COVID-19 more than regions with low HDI. North America and Europe together account for 55 and 51% of cases and deaths, respectively. Regions with high HDI are affected by COVID-19 despite their high universal health coverage index (UHCI) and Global Health Security index (GHSI) [ 7 ].

This seems to be a paradox (against the established knowledge that countries with weak (public) health systems capacity will have worse health outcomes) in that the countries with higher UHCI and GHSI have experienced higher burdens of COVID-19 [ 7 ]. The paradox can partially be explained by variations in testing algorithms, capacity for testing, and reporting across different countries. Countries with high HDI have health systems with a high testing capacity; the average testing rate per million population is less than 32, 000 in Africa and 160,000 in Asia while it is more than 800, 000 in HICs (Europe and North America). This enables HICs to identify more confirmed cases that will ostensibly increase the number of reported cases [ 3 ]. Nevertheless, these are insufficient to explain the stark differences between countries with high HDI and those with low HDI. Many countries with high HDI have a high testing rate and a higher proportion of symptomatic and severe cases, which are also associated with higher deaths and CFRs [ 7 ]. On the other hand, there are countries with high HDI that sustain a lower level of the epidemic than others with a similar high HDI. It is, therefore, vital to analyse the heterogeneity of the COVID-19 pandemic and explain why some countries with high HDI, UHCI and GHSI have the highest burden of COVID-19 while others are able to suppress their epidemics and mitigate its impacts.

The objective of this study was to analyse the COVID-19 pandemic and understand its variable expression with the intention to learn lessons for an effective and sustainable response to public health emergencies. We hypothesised that high levels of HDI, UHCI and GHSI are essential but not sufficient to prevent and control COVID-19.

We conducted an explanatory mixed-methods study to understand and explain the heterogeneity of the pandemic around the world. The study integrated quantitative and qualitative secondary data. The following steps were included in the research process: (i) collecting and analysing quantitative epidemiological data, (ii) conducting literature review of qualitative secondary data and (iii) evaluating countries’ pandemic responses to explain the variability in the COVID-19 epidemiological outcomes. The study then illuminated specific factors that were vital towards an effective and sustainable epidemic response.

We used the publicly available secondary data sources from Johns Hopkins University ( https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases ) for COVID-19 and UNDP 2020 HDI report ( http://hdr.undp.org/en/2019-report ) for HDI, demographic and epidemiologic variables. These are open data sources which are regularly updated and utilized by researchers, policy makers and funders. We performed a correlation analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic. We determined the association between COVID-19 cases, severity, deaths and CFRs at the 0.01 and 0.05 levels (2-tailed). We used Spearman’s correlation analysis, as there is no normal distribution of the variables [ 8 ].

The UHCI is calculated as the geometric mean of the coverage of essential services based on 17 tracer indicators from: (1) reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health; (2) infectious diseases; (3) non-communicable diseases; and, (4) service capacity and access and health security [ 9 ]. The GHSI is a composite measure to assess a country’s capability to prevent, detect, and respond to epidemics and pandemics [ 10 ].

We then conducted a document review to explain the epidemic patterns in different countries. Secondary data was obtained from peer-reviewed journals, reputable online news outlets, government reports and publications by public health-related associations, such as the WHO. To explain the variability of COVID-19 across countries, a list of 14 indicators was established to systematically assess country’s preparedness, actual pandemic response, and overall socioeconomic and demographic profile in the context of COVID-19. The indicators used in this study include: 1) Universal Health Coverage Index, 2) public health capacity, 3) Global Health Security Index, 4) International Health Regulation, 5) leadership, governance and coordination of response, 6) community mobilization and engagement, 7) communication, 8) testing, quarantines and social distancing, 9) medical services at primary health care facilities and hospitals, 10) multisectoral actions, 11) social protection services, 12) absolute and relative poverty status, 13) demography, and 14) burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. These indicators are based on our previous studies and recommendation from the World Health Organization [ 3 , 4 ]. We conducted thematic analysis and synthesis to identify the factors that may explain the heterogeneity of the pandemic.

Heterogeneity of COVID-19 cases and deaths around the world: what can explain it?

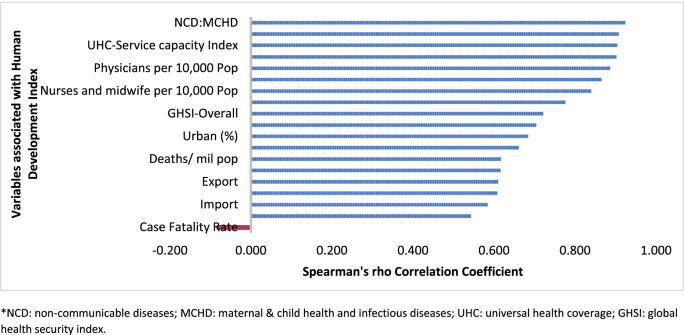

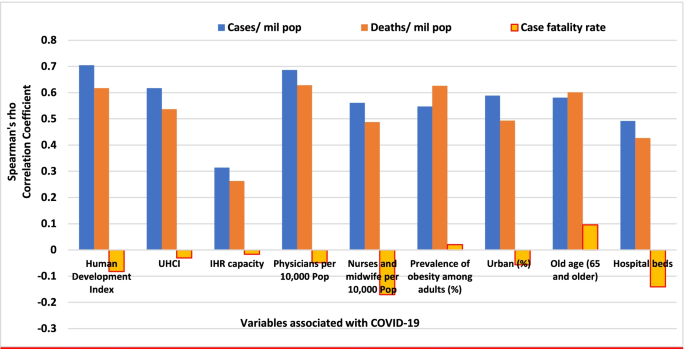

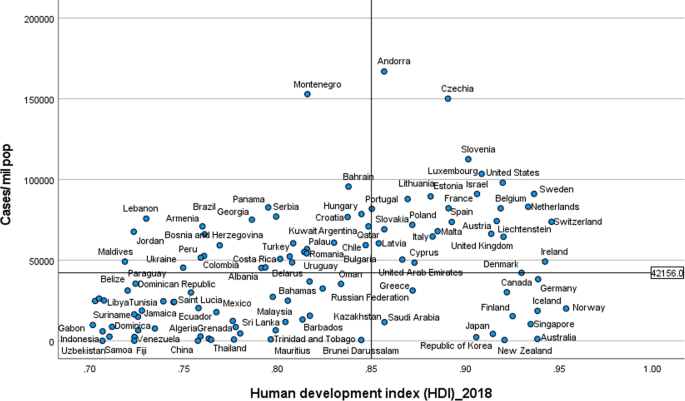

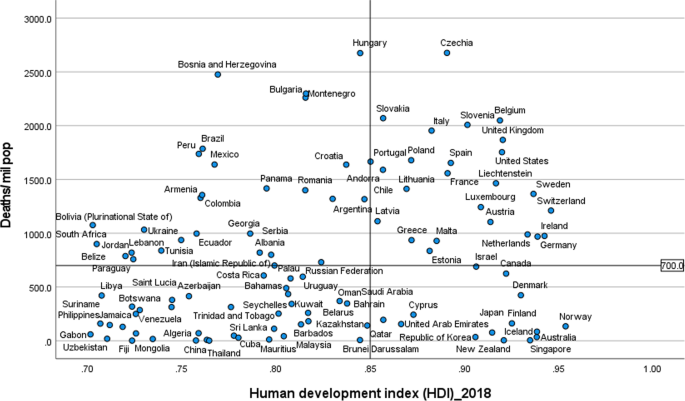

Table 1 indicates that the pandemic of COVID-19 is heterogeneous around regions of the world. Figure 1 also shows that there is a strong and significant correlation between HDI and globalisation (with an increase in trade and tourism as proxy indicators) and a corresponding strong and significant correlation with COVID-19 burden.

Human development index and its correlates associated with COVID-19 in 189 countries*

Globalisation and pandemics interact in various ways, including through international trade and mobility, which can lead to multiple waves of infections [ 11 ]. In at least the first waves of the pandemic, countries with high import and export of consumer goods, food products and tourism have high number of cases, severe cases, deaths and CFRs. Countries with high HDI are at a higher risk of importing (and exporting) COVID-19 due to high mobility linked to trade and tourism, which are drivers of the economy. These may have led to multiple introductions of COVID-19 into these countries before border closures.

The COVID-19 pandemic was first identified in China, which is central to the global network of trade, from where it spread to all parts of the world, especially those countries with strong links with China [ 12 ]. The epidemic then spread to Europe. There is very strong regional dimension to manufacturing and trading, which could be facilitate the spread of the virus. China is the heart of ‘Factory Asia’; Italy is in the heart of ‘Factory Europe’; the United States is the heart of ‘Factory North America’; and Brazil is the heart of ‘Factory Latin America’ [ 13 ]. These are the countries most affected by COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic [ 2 , 3 , 14 ].

It is also important to note that two-third of the countries currently reporting more than a million cases are middle-income countries (MICs), which are not only major emerging market economies but also regional political powers, including the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa) [ 3 , 15 ]. These countries participate in the global economy, with business travellers and tourists. They also have good domestic transportation networks that facilitate the internal spread of the virus. The strategies that helped these countries to become emerging markets also put them at greater risk for importing and spreading COVID-19 due to their connectivity to the rest of the world.

In addition, countries with high HDI may be more significantly impacted by COVID-19 due to the higher proportion of the elderly and higher rates of non-communicable diseases. Figure 1 shows that there is a strong and significant correlation between HDI and demographic transition (high proportion of old-age population) and epidemiologic transition (high proportion of the population with non-communicable diseases). Countries with a higher proportion of people older than 65 years and NCDs (compared to communicable diseases) have higher burden of COVID-19 [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Evidence has consistently shown a higher risk of severe COVID-19 in older individuals and those with underlying health conditions [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. CFR is age-dependent; it is highest in persons aged ≥85 years (10 to 27%), followed by those among persons aged 65–84 years (3 to 11%), and those among persons aged 55-64 years (1 to 3%) [ 26 ].

On the other hand, regions and countries with low HDI have, to date, experienced less severe epidemics. For instance, as of January 12, 2022, the African region has recorded about 10.3 million cases and 233,000 deaths– far lower than other regions of the world (Table 1 ) [ 27 ]. These might be due to lower testing rates in Africa, where only 6.5% of the population has been tested for the virus [ 14 , 28 ], and a greater proportion of infections may remain asymptomatic [ 29 ]. Indeed, the results from sero-surveys in Africa show that more than 80% of people infected with the virus were asymptomatic compared to an estimated 40-50% asymptomatic infections in HICs [ 30 , 31 ]. Moreover, there is a weak vital registration system in the region indicating that reports might be underestimating and underreporting the disease burden [ 32 ]. However, does this fully explain the differences observed between Africa and Europe or the Americas?

Other possible factors that may explain the lower rates of cases and deaths in Africa include: (1) Africa is less internationally connected than other regions; (2) the imposition of early strict lockdowns in many African countries, at a time when case numbers were relatively small, limited the number of imported cases further [ 2 , 33 , 34 ]; (3) relatively poor road network has also limited the transmission of the virus to and in rural areas [ 35 ]; (4) a significant proportion of the population resides in rural areas while those in urban areas spend a lot of their time mostly outdoors; (5) only about 3% of Africans are over the age of 65 (so only a small proportion are at risk of severe COVID-19) [ 36 ]; (6) lower prevalence of NCDs, as disease burden in Africa comes from infectious causes, including coronaviruses, which may also have cross-immunity that may reduce the risk of developing symptomatic cases [ 37 ]; and (7) relative high temperature (a major source of vitamin D which influences COVID-19 infection and mortality) in the region may limit the spread of the virus [ 38 , 39 ]. We argue that a combination of all these factors might explain the lower COVID-19 burden in Africa.

The early and timely efforts by African leaders should not be underestimated. The African Union, African CDC, and WHO convened an emergency meeting of all African ministers of health to establish an African taskforce to develop and implement a coordinated continent-wide strategy focusing on: laboratory; surveillance; infection prevention and control; clinical treatment of people with severe COVID-19; risk communication; and supply chain management [ 40 ]. In April 2021, African Union and Africa CDC launched the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM), framework to expanding Africa’s vaccine manufacturing capacity for health security [ 41 ].

Heterogeneity of the pandemic among countries with high HDI: what can explain it?

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the variability of cases and deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic across high-income countries (HICs). Contrary to the overall positive correlation between high HDI and cases, deaths and fatality rates due to COVID-19, there are outlier HICs, which have been able to control the epidemic. Several HICs, such as New Zealand, Australia, South Korea, Japan, Denmark, Iceland, and Norway, managed to contain their epidemics (Figs. 2 and 3 ) [ 15 , 42 , 43 ]. It is important to note that most of these countries (especially the island states) have far less cross-border mobility than other HICs.

Scatter plot of COVID-19 cases per million population in countries with high human development index (> 0.70)

Scatter plot of COVID-19 deaths per million population in countries with high human development index (> 0.70)

HICs that have been successful at controlling their epidemics have similar characteristics, which are related to governance of the response [ 44 ], synergy between UHC and GHS, and existing relative socio-economic equity in the country. Governance and leadership is a crucial factor to explain the heterogeneity of the epidemic among countries with high HDI [ 45 ]. There has been substantial variation in the nature and timing of the public health responses implemented [ 46 ]. Adaptable and agile governments seem better able to respond to their epidemics [ 47 , 48 ]. Countries that have fared the best are the ones with good governance and public support [ 49 ]. Countries with an absence of coherent leadership and social trust have worse outcomes than countries with collective action, whether in a democracy or autocracy, and rapid mobilisation of resources [ 50 ]. The erosion of trust in the United States government has hurt the country’s ability to respond to the COVID-19 crisis [ 51 , 52 ]. The editors of the New England Journal of Medicine argued that the COVID-19 crisis has produced a test of leadership; but, the leaders in the United States had failed that test [ 47 ].

COVID-19 has exposed the fragility of health systems, not only in the public health and primary care, but also in acute and long-term care systems [ 49 ]. Fragmentation of health systems, defined here to mean inadequate synergy and/ or integration between GHS and UHC, is typical of countries most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though GHS and UHC agendas are convergent and interdependent, they tend to have different policies and practices [ 53 ]. The United States has the highest index for GHS preparedness; however, it has reported the world’s highest number of COVID-19 cases and deaths due to its greatly fragmented health system [ 54 , 55 ]. Countries with health systems and policies that are able to integrate International Health Regulations (IHR) core capacities with primary health care (PHC) services have been effective at mitigating the effects of COVID-19 [ 50 , 53 ]. Australia has been able to control its COVID-19 epidemic through a comprehensive primary care response, including protection of vulnerable people, provision of treatment and support services to affected people, continuity of regular healthcare services, protection and support of PHC workers and primary care services, and provision of mental health services to the community and the primary healthcare workforce [ 56 ]. Strict implementation of public health and social intervention together with UHC systems have ensured swift control of the epidemics in Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand [ 57 ].

The heterogeneity of cases and deaths, due to COVID-19, is also explained by differences in levels of socio-economic inequalities, which increase susceptibility to acquiring the infection and disease progression as well as worsening of health outcomes [ 58 ]. COVID-19 has been a stress test for public services and social protection systems. There is a higher burden of COVID-19 in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals due to socio-economic inequities in HICs [ 59 , 60 ]. Poor people are more likely to live in overcrowded accommodation, are more likely to have unstable work conditions and incomes, have comorbidities associated with poverty and precarious living conditions, and reduced access to health care [ 59 ].

The epidemiology of COVID-19 is also variable across MICs, with HDI between 0.70 and 0.85, around the world. Overall, the epidemic in MICs is exacerbated by the rapid demographic and epidemiologic transitions as well as high prevalence of obesity. While India and Brazil witnessed rapidly increasing rates of cases and deaths, China, Thailand, Vietnam have experienced a relatively lower disease burden [ 15 ]. This heterogeneity may be attributed to a number of factors, including governance, communication and service delivery. Thailand, China and Vietnam have implemented a national harmonized strategic response with decentralized implementation through provincial and district authorities [ 61 ]. Thailand increased its testing capacity from two to over 200 certified facilities that could process between 10,000 to 100,000 tests per day; moreover, over a million village health volunteers in Thailand supported primary health services [ 62 , 63 ]. China’s swift and decisive actions enabled the country to contain its epidemic though there was an initial delay in detecting the disease. China has been able to contain its epidemic through community-based measures, very high public cooperation and social mobilization, strategic lockdown and isolation, multi-sector action [ 64 ]. Overall, multi-level governance (effective and decisive leadership and accountability) of the response, together with coordination of public health and socio-economic services, and high levels of citizen adherence to personal protection, have enabled these countries to successfully contain their epidemics [ 61 , 65 , 66 ].

On the other hand, the Brazilian leadership was denounced for its failure to establish a national surveillance network early in the pandemic. In March 2020, the health minister was reported to have stated that mass testing was a waste of public funding, and to have advised against it [ 67 ]. This was considered as a sign of a collapse of public health leadership, characterized by ignorance, neoliberal authoritarianism [ 68 ]. There were also gaps in the public health capacity in different municipalities, which varied greatly, with a considerable number of Brazilian regions receiving less funding from the federal government due to political tension [ 69 ]. The epidemic has a disproportionate adverse burden on states and municipalities with high socio-economic vulnerability, exacerbated by the deep social and economic inequalities in Brazil [ 70 ].

India is another middle-income country with a high burden of COVID-19. It was one of the countries to institute strict measures in the early phase of the pandemic [ 71 , 72 ]. However, the government eased restrictions after the claim that India had beaten the pandemic, which lead to a rapid increase in disease incidence. Indeed, on 12 January 2022, India reported 36 million cumulative cases and almost 485,000 total deaths [ 15 ]. The second wave of the epidemic in India exposed weaknesses in governance and inadequacies in the country’s health and other social systems [ 73 ]. The nature of the Indian federation, which is highly centripetal, has prevented state and local governments from tailoring a policy response to suit local needs. A centralized one-size-fits-all strategy has been imposed despite high variations in resources, health systems capacity, and COVID-19 epidemics across states [ 74 ]. There were also loose social distancing and mask wearing, mass political rallies and religious events [ 75 ]. Rapid community transmission driven by high population density and multigenerational households has been a feature of the current wave in India [ 76 ]. In addition, several new variants of the virus, including the UK (B.1.1.7), the South Africa (20H/501Y or B.1.351), and Brazil (P.1), alongside a newly identified Indian variant (B.1.617), are circulating in India and have been implicated as factors in the second wave of the pandemic [ 75 , 76 ].

Heterogeneity of case-fatality rates around the world: what can explain it?

The pandemic is characterized by variable CFRs across regions and countries that are negatively associated with HDI (Fig. 1 ). The results presented in Fig. 4 show that the proportion of elderly population and rate of obesity are important factors which are positively associated with CFR. On the other hand, UHC, IHR capacity and other indicators of health systems capacity (health workforce density and hospital beds) are negatively associated with the CFR (Figs. 1 and 4 ).

Correlates of COVID-19 cases, deaths and case-fatality rates in 189 countries

The evidence from several research indicates that heterogeneity can be explained by several factors, including differences in age-pyramid, socio-economic status, access to health services, or rates of undiagnosed infections. Differences in age-pyramid may explain some of the observed variation in epidemic severity and CFR between countries [ 77 ]. CFRs across countries look similar when taking age into account [ 78 ]. The elderly and other vulnerable populations in Africa and Asia are at a similar risk as populations in Europe and Americas [ 79 ]. Data from European countries suggest that as high as 57% of all deaths have happened in care homes and many deaths in the US have also occurred in nursing homes. On the other hand, in countries such as Mexico and India, individuals < 65 years contributed the majority of deaths [ 80 ].

Nevertheless, CFR also depends on the quality of hospital care, which can be used to judge the health system capacity, including the availability of healthcare workers, resources, and facilities, which affects outcomes [ 81 ]. The CFR can increase if there is a surge of infected patients, which adds to the strain on the health system [ 82 ]. COVID-19 fatality rates are affected by numerous health systems factors, including bed capacity, existence and capacity of intensive care unit (ICU), and critical care resources (such as oxygen and dexamethasone) in a hospital. Regions and countries with high HDI have a greater number of acute care facilities, ICU, and hospital bed capacities compared to lower HDI regions and countries [ 83 ]. Differences in health systems capacity could explain why North America and Europe, which have experienced much greater number of cases and deaths per million population, reported lower CFRs than the Southern American and the African regions, partly also due to limited testing capacity in these regions (Table 1 ) [ 84 , 85 , 86 ]. The higher CFR in Southern America can be explained by the relatively lower health systems surge capacity that could not adequately respond to the huge demand for health services [ 69 , 86 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted existing health systems’ weaknesses, which are not able to effectively prepare for and respond to PHEs [ 87 ]. The high CFRs in the region are also exacerbated by the high social inequalities [ 69 ].

On the other hand, countries in Asia recorded lower CFRs (~ 1.4%) despite sharing many common risk factors (including overcrowding and poverty, weak health system capacity etc) with Africa. The Asian region shares many similar protective factors to the African region. They have been able to minimize their CFR by suppressing the transmission of the virus and flattening the epidemic curve of COVID-19 cases and deaths. Nevertheless, the epidemic in India is likely to be different because it has exceeded the health system capacity to respond and provide basic medical care and medical supplies such as oxygen [ 88 ]. Overall, many Asian countries were able to withstand the transmission of the virus and its effect due to swift action by governments in the early days of the pandemic despite the frequency of travel between China and neighbouring countries such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore [ 89 ]. This has helped them to contain the pandemic to ensure case numbers remain within their health systems capacity. These countries have benefited from their experience in the past in the prevention and control of epidemics [ 90 ].

There are a number of issues with the use of the CFR to compare the management of the pandemic between countries and regions [ 91 ], as it does not depict the true picture of the mortality burden of the pandemic. A major challenge with accurate calculation of the CFR is the denominator on number of identified cases, as asymptomatic infections and patients with mild symptoms are frequently left untested, and therefore omitted from CFR calculations. Testing might not be widely available, and proactive contact tracing and containment might not be employed, resulting in a smaller denominator, and skewing to a higher CFR [ 82 ]. It is, therefore, far more relevant to estimate infection fatality rate (IFR), the proportion of all infected individuals who have died due to the infection [ 91 ], which is central to understanding the public health impact of the pandemic and the required policies for its prevention and control [ 92 ].

Estimates of prevalence based on sero-surveys, which includes asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic infections, can be used to estimate IFR [ 93 ]. In a systematic review of 17 studies, seroprevalence rates ranged from 0.22% in Brazil to 53% in Argentina [ 94 ]. The review also identified that the seroprevalence estimate was higher than the cumulative reported case incidence, by a factor between 1.5 times in Germany to 717 times in Iran, in all but two studies (0.56 times in Brazil and 0.88 times in Denmark) [ 94 , 95 ]. The difference between seroprevalence and cumulative reported cases might be due to asymptomatic cases, atypical or pauci-symptomatic cases, or the lack of access to and uptake of testing [ 94 ]. There is only a modest gap between the estimated number of infections from seroprevalence surveys and the cumulative reported cases in regions with relatively thorough symptom-based testing. Much of the gap between reported cases and seroprevalence is likely to be due to undiagnosed symptomatic or asymptomatic infections [ 94 ].

Collateral effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

It is important to note that the pandemic has significant collateral effects on the provision of essential health services, in addition to the direct health effects [ 96 ]. Disruptions in the provision of essential health services, due to COVID-19, were reported by nearly all countries, though it is more so in lower-income than higher-income countries [ 97 , 98 ]. The biggest impact reported is on provision of day-to-day primary care to prevent and manage some of the most common health problems [ 99 ].

The causes of disruptions in service delivery were a mix of demand and supply factors [ 100 ]. Countries reported that just over one-third of services were disrupted due to health workforce-related reasons (the most common causes of service disruptions), supply chains, community mistrust and fears of becoming infected, and financial challenge s[ 101 ]. Cognizant of the disruptive effects of the pandemic, countries have reorganized their health system.

Countries with better response to COVID-19 have mobilized, trained and reallocated their health workforce in addition to hiring new staff, using volunteers and medical trainees and mobilizing retirees [ 102 ]. Several strategies have also been implemented to mitigate disruptions in service delivery and utilization, including: triaging to identify the most urgent patient needs, and postponing elective medical procedures; switching to alternative models of care, such as providing more home-based care and telemedicine [ 101 ].

This study identifies that the COVID-19 pandemic, in terms f cases and deaths, is heterogeneous around the world. This variability is explained by differences in vulnerability, preparedness, and response. It confirms that a high level of HDI, UHCI and GHSI are essential but not sufficient to control epidemics [ 103 ]. An effective response to public health emergencies requires a joint and reinforcing implementation of UHC, health emergency and disease control priorities [ 104 , 105 ], as well as good governance and social protection systems [ 106 ]. Important lessons have been learned to cope better with the COVID-19 pandemic and future emerging or re-emerging pandemics. Countries should strengthen health systems, minimize fragmentation of public health, primary care and secondary care, and improve coordination with other sectors. The pandemic has exposed the health effects of longstanding social inequities, which should be addressed through policies and actions to tackle vulnerability in living and working conditions [ 106 ].

The shift in the pandemic epicentre from high-income to MICs was observed in the second global wave of the pandemic. This is due to in part to the large-scale provision of vaccines in HICs [ 15 ] as well as the limitations in the response in LMICs, including inadequate testing, quarantine and isolation, contact tracing, and social distancing. The second wave of the pandemic in low- and middle-income countries spread more rapidly than the first wave and affected younger and healthier populations due to factors, including poor government decision making, citizen behaviour, and the emergence of highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants [ 107 ]. It has become catastrophic in some MICs to prematurely relax key public health measures, such as mask wearing, physical distancing, and hand hygiene [ 108 ].

There is consensus that global vaccination is essential to ending the pandemic. Universal and equitable vaccine delivery, implemented with high volume, speed and quality, is vital for an effective and sustainable response to the current pandemic and future public health emergencies. There is, however, ongoing concern regarding access to COVID-19 vaccines in low-income countries [ 109 ]. Moreover, there is shortage of essential supplies, including oxygen, which has had a major impact on the prevention and control of the pandemic. It is, therefore, vital to transform (through good governance and financing mechanisms) the ACT-A platform to deliver vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and other essential supplies [ 109 , 110 ]. The global health community has the responsibility to address these inequalities so that we can collectively end the pandemic [ 107 ].

The Omicron variant has a huge role in the current wave around the world despite high vaccine coverage [ 111 ]. Omicron appears to spread rapidly around the world ever since it was identified in November 2021 [ 112 ]. It becomes obvious that vaccination alone is inadequate for controlling the infection. This has changed our understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic endgame. The emergence of new variants of concern and their spread around the world has highlighted the importance of combination prevention, including high vaccination coverage in combination with other public health prevention measures [ 112 ].

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic and the response to it emphasise valuable lessons towards an effective and sustainable response to public health emergencies. We argue that the PHC approach captures the different preparedness and response strategies required towards ensuring health security and UHC [ 113 ]. The PHC approach enables countries to progressively realize universal access to good-quality health services (including essential public health functions) and equity, empower people and communities, strengthen multi-sectoral policy and action for health, and enhance good governance [ 114 ]. These are essential in the prevention and control of public health emergencies, to suppress transmission, and reduce morbidity and mortality [ 115 ]. Access to high-quality primary care is at the foundation of any strong health system [ 116 ], which will, in turn, have effect on containing the epidemic, and reducing mortality and CFR [ 117 ]. Australia is a good example in this regard because it has implemented a comprehensive PHC approach in combination with border restrictions to ensure health system capacity is not exceeded [ 56 ]. The PHC approach will enable countries to develop and implement a context-specific health strategy, enhance governance, strengthen their (public) health systems, minimize segmentation and fragmentation, and tackle upstream structural issues, including discrimination and socio-economic inequities [ 118 ]. This is the type of public health approach (comprehensive, equity-focused and participatory) that will be effective and sustainable to tackle public health emergencies in the twenty-first century [ 119 , 120 ]. In addition, it is vital to transform the global and regional health systems, with a strong IHR and an empowered WHO at the apex [ 121 ]. We contend that this is the way towards a healthier and safer country, region and world.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that the world remains vulnerable to public health emergencies with significant health and other socio-economic impacts. The pandemic takes variable shapes and forms across regions and countries around the world. The pandemic has impacted countries with inadequate governance of the epidemic, fragmentation of their health systems and higher socio-economic inequities more than others. We argue that adequate response to public health emergencies requires that countries develop and implement a context-specific national strategy, enhance governance of public health emergency, build the capacity of their health systems, minimize fragmentation, and tackle socio-economic inequities. This is possible through a PHC approach that provides universal access to good-quality health services through empowered communities and multi-sectoral policy and action for health development. The pandemic has affected every corner of the world; it has demonstrated that “no country is safe unless other countries are safe”. This should be a call for a strong global health system based on the values of justice and capabilities for health.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in a public, open access repository: Johns Hopkins University: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases , and UNDP: http://hdr.undp.org/en/2019-report ; WHO: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update%2D%2D-22-december-2020

Abbreviations

Coronavirus Disease 2019

Case-fatality rates

Human development index

Universal health coverage index

Global Health Security index

High-income countries

Middle-income countries

El Zowalaty ME, Järhult JD. From SARS to COVID-19: A previously unknown SARS-CoV-2 virus of pandemic potential infecting humans–Call for a One Health approach. One Health. 2020;9:100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100124 .

Van Damme W, Dahake R, Delamou A, Ingelbeen B, Wouters E, Vanham G, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: diverse contexts; different epidemics—how and why? BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(7):e003098.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization (WHO): Coronavirus disease ( COVID-19): situation report, 150. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200618-covid-19-sitrep-150.pdf .

Weekly epidemiological update - 22 December 2020 [ https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update%2D%2D-22-december-2020 ].

Worldometer: COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ .

Anand S, Sen A. Human Development Index: Methodology and Measurement. 1994. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-methodology-and-measurement .

De Larochelambert Q, Marc A, Antero J, Le Bourg E, Toussaint J-F. Covid-19 mortality: a matter of vulnerability among nations facing limited margins of adaptation. Public Health. 2020;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.604339 .

de Winter JC, Gosling SD, Potter J. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: a tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychol Methods. 2016;21(3):273.

World Health Organization. Universal health coverage [ http://www.who.int/universal_health_coverage/en/ ].

Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Global Health Security Index [ https://www.ghsindex.org/ ].

Pol Antràs SJR. Esteban Rossi-Hansberg: how do globalisation and pandemics interact? Surprising insights from a new model. In: #LSEThinks | CEP | global development vol. 2020. London: London School of Economics; 2020.

Google Scholar

Cai P. Understanding China’s belt and road initiative; 2017.

Baldwin R, Tomiura E. Thinking ahead about the trade impact of COVID-19. Economics in the Time of COVID-19. 2020;59. https://repository.graduateinstitute.ch/record/298220?ln=en .

Organization WH: Coronavirus disease ( COVID-19): situation report, 182. 2020.

Johns Hopkins University: COVID-19 Map - Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. In. Edited by Security JHUCfH; 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html .

Wang T, Du Z, Zhu F, Cao Z, An Y, Gao Y, et al. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):e52.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061–9.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13.

Hussain A, Bhowmik B, Do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108142 . Epub 2020 Apr 9.

Covid C, COVID C, COVID C, Chow N, Fleming-Dutra K, Gierke R, Hall A, et al. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019—United States, February 12–march 28, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):382.

Group C-S. Characteristics of COVID-19 patients dying in Italy: report based on available data on March 20th, 2020. Rome: Instituto Superiore Di Sanita; 2020. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Report-COVID-2019_20_marzo_eng.pdf .

Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. Jama. 2020;323(16):1612–4.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the new York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775 .

Covid C, Team R. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–march 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343–6.

Article Google Scholar

Mbow M, Lell B, Jochems SP, Cisse B, Mboup S, Dewals BG, et al. COVID-19 in Africa: dampening the storm? Science. 2020;369(6504):624–6.

Kavanagh MM, Erondu NA, Tomori O, Dzau VJ, Okiro EA, Maleche A, et al. Access to lifesaving medical resources for African countries: COVID-19 testing and response, ethics, and politics. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1735–8.

Nordling L. Africa's pandemic puzzle: why so few cases and deaths? In: American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2020.

Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):362–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-3012 . Epub 2020 Jun 3.

Nikolai LA, Meyer CG, Kremsner PG, Velavan TP. Asymptomatic SARS coronavirus 2 infection: invisible yet invincible. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:112–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.076 . Epub 2020 Sep 3.

Rao C, Bradshaw D, Mathers CD. Improving death registration and statistics in developing countries: lessons from sub-Saharan Africa. Southern Afr J Demography. 2004:81–99.

Mehtar S, Preiser W, Lakhe NA, Bousso A, TamFum J-JM, Kallay O, et al. Limiting the spread of COVID-19 in Africa: one size mitigation strategies do not fit all countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(7):e881–3. Published online 2020 Apr 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30212-6 .

Nachega J, Seydi M, Zumla A. The late arrival of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Africa: mitigating pan-continental spread. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):875–8.

Gwilliam K, Foster V, Archondo-Callao R, Briceno-Garmendia C, Nogales A, Sethi K. Africa infrastructure country diagnostic: roads in sub-Saharan Africa: The World Bank; 2008.

Guengant J-P. Africa’s population: history, current status, and projections. In: Africa's Population: In Search of a Demographic Dividend: Springer; 2017. p. 11–31.

Collaborators GOD, Bernabe E, Marcenes W, Hernandez C, Bailey J, Abreu L, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J Dent Res. 2020;99(4):362–73.

Cambaza EM, Viegas GC, Cambaza C. Manuel a: potential impact of temperature and atmospheric pressure on the number of cases of COVID-19 in Mozambique, southern Africa. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2020;12(3):246–60.

Lawal Y. Africa’s low COVID-19 mortality rate: a paradox? Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:118–22.

Nkengasong JN, Mankoula W. Looming threat of COVID-19 infection in Africa: act collectively, and fast. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):841–2.

African Union and Africa CDC. African union and Africa CDC launches partnerships for African vaccine manufacturing (PAVM), framework to achieve it and signs 2 MoUs: African Union and Africa CDC; 2021.

Forbes. What Do Countries With The Best Coronavirus Responses Have In Common? Women Leaders [ https://www.forbes.com/sites/avivahwittenbergcox/2020/04/13/what-do-countries-with-the-best-coronavirus-reponses-have-in-common-women-leaders/#603bd9433dec ].

University of Notre Dame. What can we learn from Austria’s response to COVID-19? [ https://keough.nd.edu/what-can-we-learn-from-austrias-response-to-covid-19/ ].

Stoller JK. Reflections on leadership in the time of COVID-19. BMJ Leader. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2020-000244 .

Houston Public Media. What 6 Of The 7 Countries With The Most COVID-19 Cases Have In Common [ https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/07/31/896879448/the-nations-with-the-most-to-lose-from-covid-19 ].

Hale T, Petherick A, Phillips T, Webster S. Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik school of government working paper. 2020;31. https://en.unesco.org/inclusivepolicylab/sites/default/files/learning/document/2020/4/BSG-WP-2020-031-v3.0.pdf .

The Editors. Dying in a leadership vacuum. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1479–80.

The Cable News Network. US and UK are bottom of the pile in rankings of governments' handling of coronavirus pandemic [ https://edition.cnn.com/2020/08/27/world/global-coronavirus-attitudes-pew-intl/index.html ].

Huston P, Campbell J, Russell G, Goodyear-Smith F, Phillips RL, van Weel C, et al. COVID-19 and primary care in six countries. BJGP Open. 2020;4(4):bjgpopen20X101128. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101128 .

Goodyear-Smith F, Kinder K, Eden AR, Strydom S, Bazemore A, Phillips R, et al. Primary care perspectives on pandemic politics. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(8-9):1304–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1876751 . Epub 2021 Jan 24.

Rutledge PE. Trump, COVID-19, and the war on expertise. Am Rev Public Adm. 2020;50(6-7):505–11.

Ugarte DA, Cumberland WG, Flores L, Young SD. Public attitudes about COVID-19 in response to president trump's social media posts. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210101.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, Gitahi G, Yates R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet. 2021;397(10268):61–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5 . Epub 2020 Dec 1.

Tromberg BJ, Schwetz TA, Pérez-Stable EJ, Hodes RJ, Woychik RP, Bright RA, et al. Rapid scaling up of Covid-19 diagnostic testing in the United States—the NIH RADx initiative. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1071–7.

Marwaha J, Halamka J, Brat G. Lifesaving ventilators will sit unused without a national data-sharing effort; 2020.

Kidd MR. Five principles for pandemic preparedness: lessons from the Australian COVID-19 primary care response. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(696):316–7. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X710765 . Print 2020 Jul.

Hsu LY, Tan M-H. What Singapore can teach the US about responding to COVID-19. STAT News. 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/03/23/singapore-teach-united-states-about-covid-19-response/ .

Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet (London, England). 2020;396(10255):874.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Raisi-Estabragh Z, McCracken C, Bethell MS, Cooper J, Cooper C, Caulfield MJ, et al. Greater risk of severe COVID-19 in black, Asian and minority ethnic populations is not explained by cardiometabolic, socioeconomic or behavioural factors, or by 25 (OH)-vitamin D status: study of 1326 cases from the UK biobank. J Public Health. 2020;42(3):451–60.

Hamidianjahromi A. Why African Americans are a potential target for COVID-19 infection in the United States. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e19934.

Tangcharoensathien V, Bassett MT, Meng Q, Mills A. Are overwhelmed health systems an inevitable consequence of covid-19? Experiences from China, Thailand, and New York State. BMJ. 2021;372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n83 .

Organization WH: COVID-19 health system response monitor, Thailand. 2020.

Narkvichien M. Thailand’s 1 million village health volunteers-“unsung heroes”-are helping guard communities nationwide from COVID-19. Nonthaburi: World Health Organization; 2020.

Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J. Can China's COVID-19 strategy work elsewhere? In: American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2020.

Al Saidi AMO, Nur FA, Al-Mandhari AS, El Rabbat M, Hafeez A, Abubakar A. Decisive leadership is a necessity in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):295–8.

Forman R, Atun R, McKee M, Mossialos E. 12 lessons learned from the management of the coronavirus pandemic. Health Policy. 2020;124(6):577–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.05.008 .

Barberia LG, Gómez EJ. Political and institutional perils of Brazil's COVID-19 crisis. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):367–8.

Ortega F, Orsini M. Governing COVID-19 without government in Brazil: ignorance, neoliberal authoritarianism, and the collapse of public health leadership. Global Public Health. 2020;15(9):1257–77.

Ezequiel GE, Jafet A, Hugo A, Pedro D, Ana Maria M, Carola OV, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action for health systems in Latin America to strengthen quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021;33(1):mzaa062.

Rocha R, Atun R, Massuda A, Rache B, Spinola P, Nunes L, et al. Effect of socioeconomic inequalities and vulnerabilities on health-system preparedness and response to COVID-19 in Brazil: a comprehensive analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e782–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00081-4 . Epub 2021 Apr 12.

Lancet T. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10233):1315.

Siddiqui AF, Wiederkehr M, Rozanova L, Flahault A. Situation of India in the COVID-19 pandemic: India’s initial pandemic experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8994.

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Taneja P, Bali AS. India’s domestic and foreign policy responses to COVID-19. Round Table. 2021;110(1):46–61.

Choutagunta A, Manish G, Rajagopalan S. Battling COVID-19 with dysfunctional federalism: lessons from India. South Econ J. 2021;87(4):1267–99.

Mallapaty S. India's massive COVID surge puzzles scientists. Nature. 2021;592(7856):667–8.

Thiagarajan K. Why is India having a covid-19 surge? In: British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2021.

Fisman DN, Greer AL, Tuite AR. Age is just a number: a critically important number for COVID-19 case fatality. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):762–3.

Sudharsanan N, Didzun O, Bärnighausen T, Geldsetzer P. The contribution of the age distribution of cases to COVID-19 case fatality across countries: a 9-country demographic study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):714–20. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-2973 . Epub 2020 Jul 22.

Think Global Health. The Myth of South Asian Exceptionalism. In: He Myth of South Asian Exceptionalism: South Asia's young population conceals the effects that COVID-19 has on its older and more vulnerable people. vol. 2020; 2020.

Ioannidis JP, Axfors C, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Population-level COVID-19 mortality risk for non-elderly individuals overall and for non-elderly individuals without underlying diseases in pandemic epicenters. Environ Res. 2020;188:109890.

Kim D-H, Choe YJ, Jeong J-Y. Understanding and interpretation of case fatality rate of coronavirus disease 2019. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(12):e137. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e137 .

Rajgor DD, Lee MH, Archuleta S, Bagdasarian N, Quek SC. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):776–7.

Sorci G, Faivre B, Morand S. Explaining among-country variation in COVID-19 case fatality rate. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–11.

Sen-Crowe B, Sutherland M, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. A closer look into global hospital beds capacity and resource shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Res. 2021;260:56–63.

Li M, Zhang Z, Cao W, Liu Y, Du B, Chen C, et al. Identifying novel factors associated with COVID-19 transmission and fatality using the machine learning approach. Sci Total Environ. 2021;764:142810.