- Evaluation Research Design: Examples, Methods & Types

As you engage in tasks, you will need to take intermittent breaks to determine how much progress has been made and if any changes need to be effected along the way. This is very similar to what organizations do when they carry out evaluation research.

The evaluation research methodology has become one of the most important approaches for organizations as they strive to create products, services, and processes that speak to the needs of target users. In this article, we will show you how your organization can conduct successful evaluation research using Formplus .

What is Evaluation Research?

Also known as program evaluation, evaluation research is a common research design that entails carrying out a structured assessment of the value of resources committed to a project or specific goal. It often adopts social research methods to gather and analyze useful information about organizational processes and products.

As a type of applied research , evaluation research typically associated with real-life scenarios within organizational contexts. This means that the researcher will need to leverage common workplace skills including interpersonal skills and team play to arrive at objective research findings that will be useful to stakeholders.

Characteristics of Evaluation Research

- Research Environment: Evaluation research is conducted in the real world; that is, within the context of an organization.

- Research Focus: Evaluation research is primarily concerned with measuring the outcomes of a process rather than the process itself.

- Research Outcome: Evaluation research is employed for strategic decision making in organizations.

- Research Goal: The goal of program evaluation is to determine whether a process has yielded the desired result(s).

- This type of research protects the interests of stakeholders in the organization.

- It often represents a middle-ground between pure and applied research.

- Evaluation research is both detailed and continuous. It pays attention to performative processes rather than descriptions.

- Research Process: This research design utilizes qualitative and quantitative research methods to gather relevant data about a product or action-based strategy. These methods include observation, tests, and surveys.

Types of Evaluation Research

The Encyclopedia of Evaluation (Mathison, 2004) treats forty-two different evaluation approaches and models ranging from “appreciative inquiry” to “connoisseurship” to “transformative evaluation”. Common types of evaluation research include the following:

- Formative Evaluation

Formative evaluation or baseline survey is a type of evaluation research that involves assessing the needs of the users or target market before embarking on a project. Formative evaluation is the starting point of evaluation research because it sets the tone of the organization’s project and provides useful insights for other types of evaluation.

- Mid-term Evaluation

Mid-term evaluation entails assessing how far a project has come and determining if it is in line with the set goals and objectives. Mid-term reviews allow the organization to determine if a change or modification of the implementation strategy is necessary, and it also serves for tracking the project.

- Summative Evaluation

This type of evaluation is also known as end-term evaluation of project-completion evaluation and it is conducted immediately after the completion of a project. Here, the researcher examines the value and outputs of the program within the context of the projected results.

Summative evaluation allows the organization to measure the degree of success of a project. Such results can be shared with stakeholders, target markets, and prospective investors.

- Outcome Evaluation

Outcome evaluation is primarily target-audience oriented because it measures the effects of the project, program, or product on the users. This type of evaluation views the outcomes of the project through the lens of the target audience and it often measures changes such as knowledge-improvement, skill acquisition, and increased job efficiency.

- Appreciative Enquiry

Appreciative inquiry is a type of evaluation research that pays attention to result-producing approaches. It is predicated on the belief that an organization will grow in whatever direction its stakeholders pay primary attention to such that if all the attention is focused on problems, identifying them would be easy.

In carrying out appreciative inquiry, the research identifies the factors directly responsible for the positive results realized in the course of a project, analyses the reasons for these results, and intensifies the utilization of these factors.

Evaluation Research Methodology

There are four major evaluation research methods, namely; output measurement, input measurement, impact assessment and service quality

- Output/Performance Measurement

Output measurement is a method employed in evaluative research that shows the results of an activity undertaking by an organization. In other words, performance measurement pays attention to the results achieved by the resources invested in a specific activity or organizational process.

More than investing resources in a project, organizations must be able to track the extent to which these resources have yielded results, and this is where performance measurement comes in. Output measurement allows organizations to pay attention to the effectiveness and impact of a process rather than just the process itself.

Other key indicators of performance measurement include user-satisfaction, organizational capacity, market penetration, and facility utilization. In carrying out performance measurement, organizations must identify the parameters that are relevant to the process in question, their industry, and the target markets.

5 Performance Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the cost-effectiveness of this project?

- What is the overall reach of this project?

- How would you rate the market penetration of this project?

- How accessible is the project?

- Is this project time-efficient?

- Input Measurement

In evaluation research, input measurement entails assessing the number of resources committed to a project or goal in any organization. This is one of the most common indicators in evaluation research because it allows organizations to track their investments.

The most common indicator of inputs measurement is the budget which allows organizations to evaluate and limit expenditure for a project. It is also important to measure non-monetary investments like human capital; that is the number of persons needed for successful project execution and production capital.

5 Input Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the budget for this project?

- What is the timeline of this process?

- How many employees have been assigned to this project?

- Do we need to purchase new machinery for this project?

- How many third-parties are collaborators in this project?

- Impact/Outcomes Assessment

In impact assessment, the evaluation researcher focuses on how the product or project affects target markets, both directly and indirectly. Outcomes assessment is somewhat challenging because many times, it is difficult to measure the real-time value and benefits of a project for the users.

In assessing the impact of a process, the evaluation researcher must pay attention to the improvement recorded by the users as a result of the process or project in question. Hence, it makes sense to focus on cognitive and affective changes, expectation-satisfaction, and similar accomplishments of the users.

5 Impact Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- How has this project affected you?

- Has this process affected you positively or negatively?

- What role did this project play in improving your earning power?

- On a scale of 1-10, how excited are you about this project?

- How has this project improved your mental health?

- Service Quality

Service quality is the evaluation research method that accounts for any differences between the expectations of the target markets and their impression of the undertaken project. Hence, it pays attention to the overall service quality assessment carried out by the users.

It is not uncommon for organizations to build the expectations of target markets as they embark on specific projects. Service quality evaluation allows these organizations to track the extent to which the actual product or service delivery fulfils the expectations.

5 Service Quality Evaluation Questions

- On a scale of 1-10, how satisfied are you with the product?

- How helpful was our customer service representative?

- How satisfied are you with the quality of service?

- How long did it take to resolve the issue at hand?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your network?

Uses of Evaluation Research

- Evaluation research is used by organizations to measure the effectiveness of activities and identify areas needing improvement. Findings from evaluation research are key to project and product advancements and are very influential in helping organizations realize their goals efficiently.

- The findings arrived at from evaluation research serve as evidence of the impact of the project embarked on by an organization. This information can be presented to stakeholders, customers, and can also help your organization secure investments for future projects.

- Evaluation research helps organizations to justify their use of limited resources and choose the best alternatives.

- It is also useful in pragmatic goal setting and realization.

- Evaluation research provides detailed insights into projects embarked on by an organization. Essentially, it allows all stakeholders to understand multiple dimensions of a process, and to determine strengths and weaknesses.

- Evaluation research also plays a major role in helping organizations to improve their overall practice and service delivery. This research design allows organizations to weigh existing processes through feedback provided by stakeholders, and this informs better decision making.

- Evaluation research is also instrumental to sustainable capacity building. It helps you to analyze demand patterns and determine whether your organization requires more funds, upskilling or improved operations.

Data Collection Techniques Used in Evaluation Research

In gathering useful data for evaluation research, the researcher often combines quantitative and qualitative research methods . Qualitative research methods allow the researcher to gather information relating to intangible values such as market satisfaction and perception.

On the other hand, quantitative methods are used by the evaluation researcher to assess numerical patterns, that is, quantifiable data. These methods help you measure impact and results; although they may not serve for understanding the context of the process.

Quantitative Methods for Evaluation Research

A survey is a quantitative method that allows you to gather information about a project from a specific group of people. Surveys are largely context-based and limited to target groups who are asked a set of structured questions in line with the predetermined context.

Surveys usually consist of close-ended questions that allow the evaluative researcher to gain insight into several variables including market coverage and customer preferences. Surveys can be carried out physically using paper forms or online through data-gathering platforms like Formplus .

- Questionnaires

A questionnaire is a common quantitative research instrument deployed in evaluation research. Typically, it is an aggregation of different types of questions or prompts which help the researcher to obtain valuable information from respondents.

A poll is a common method of opinion-sampling that allows you to weigh the perception of the public about issues that affect them. The best way to achieve accuracy in polling is by conducting them online using platforms like Formplus.

Polls are often structured as Likert questions and the options provided always account for neutrality or indecision. Conducting a poll allows the evaluation researcher to understand the extent to which the product or service satisfies the needs of the users.

Qualitative Methods for Evaluation Research

- One-on-One Interview

An interview is a structured conversation involving two participants; usually the researcher and the user or a member of the target market. One-on-One interviews can be conducted physically, via the telephone and through video conferencing apps like Zoom and Google Meet.

- Focus Groups

A focus group is a research method that involves interacting with a limited number of persons within your target market, who can provide insights on market perceptions and new products.

- Qualitative Observation

Qualitative observation is a research method that allows the evaluation researcher to gather useful information from the target audience through a variety of subjective approaches. This method is more extensive than quantitative observation because it deals with a smaller sample size, and it also utilizes inductive analysis.

- Case Studies

A case study is a research method that helps the researcher to gain a better understanding of a subject or process. Case studies involve in-depth research into a given subject, to understand its functionalities and successes.

How to Formplus Online Form Builder for Evaluation Survey

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create your evaluation survey by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on “Create Form ” to begin.

- Edit Form Title

Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Evaluation Research Survey”.

Click on the edit button to edit the form.

Add Fields: Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for surveys in the Formplus builder.

Edit fields

Click on “Save”

Preview form.

- Form Customization

With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options

Formplus offers multiple form sharing options which enables you to easily share your evaluation survey with survey respondents. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages.

You can send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Conducting evaluation research allows organizations to determine the effectiveness of their activities at different phases. This type of research can be carried out using qualitative and quantitative data collection methods including focus groups, observation, telephone and one-on-one interviews, and surveys.

Online surveys created and administered via data collection platforms like Formplus make it easier for you to gather and process information during evaluation research. With Formplus multiple form sharing options, it is even easier for you to gather useful data from target markets.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- characteristics of evaluation research

- evaluation research methods

- types of evaluation research

- what is evaluation research

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

What is Pure or Basic Research? + [Examples & Method]

Simple guide on pure or basic research, its methods, characteristics, advantages, and examples in science, medicine, education and psychology

Formal Assessment: Definition, Types Examples & Benefits

In this article, we will discuss different types and examples of formal evaluation, and show you how to use Formplus for online assessments.

Recall Bias: Definition, Types, Examples & Mitigation

This article will discuss the impact of recall bias in studies and the best ways to avoid them during research.

Assessment vs Evaluation: 11 Key Differences

This article will discuss what constitutes evaluations and assessments along with the key differences between these two research methods.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

RCE 672: Research and Program Evaluation: APA Sample Paper

- Tips for GALILEO

- Evaluate Sources

- How to Paraphrase

- APA Citations

- APA References

- Book with Editor(s)

- Book with No Author

- Book with Organization as Author

- Chapters and Parts of Books

- Company Reports

- Journal Article

- Magazine Article

- Patents & Laws

- Unpublished Manuscripts/Informal Publications (i.e. course packets and dissertations)

- APA Sample Paper

- Paper Formatting (APA)

- Zotero Citation Tool

Contact Info

229-227-6959

Make an appointment with a Librarian

Make an appointment with a Tutor

Follow us on:

APA Sample Paper from the Purdue OWL

- The Purdue OWL has an APA Sample Paper available on its website.

- << Previous: Websites

- Next: Paper Formatting (APA) >>

- Last Updated: Jul 10, 2023 12:59 PM

- URL: https://libguides.thomasu.edu/RCE672

- Privacy Policy

Home » Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Table of Contents

Evaluating Research

Definition:

Evaluating Research refers to the process of assessing the quality, credibility, and relevance of a research study or project. This involves examining the methods, data, and results of the research in order to determine its validity, reliability, and usefulness. Evaluating research can be done by both experts and non-experts in the field, and involves critical thinking, analysis, and interpretation of the research findings.

Research Evaluating Process

The process of evaluating research typically involves the following steps:

Identify the Research Question

The first step in evaluating research is to identify the research question or problem that the study is addressing. This will help you to determine whether the study is relevant to your needs.

Assess the Study Design

The study design refers to the methodology used to conduct the research. You should assess whether the study design is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce reliable and valid results.

Evaluate the Sample

The sample refers to the group of participants or subjects who are included in the study. You should evaluate whether the sample size is adequate and whether the participants are representative of the population under study.

Review the Data Collection Methods

You should review the data collection methods used in the study to ensure that they are valid and reliable. This includes assessing the measures used to collect data and the procedures used to collect data.

Examine the Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis refers to the methods used to analyze the data. You should examine whether the statistical analysis is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce valid and reliable results.

Assess the Conclusions

You should evaluate whether the data support the conclusions drawn from the study and whether they are relevant to the research question.

Consider the Limitations

Finally, you should consider the limitations of the study, including any potential biases or confounding factors that may have influenced the results.

Evaluating Research Methods

Evaluating Research Methods are as follows:

- Peer review: Peer review is a process where experts in the field review a study before it is published. This helps ensure that the study is accurate, valid, and relevant to the field.

- Critical appraisal : Critical appraisal involves systematically evaluating a study based on specific criteria. This helps assess the quality of the study and the reliability of the findings.

- Replication : Replication involves repeating a study to test the validity and reliability of the findings. This can help identify any errors or biases in the original study.

- Meta-analysis : Meta-analysis is a statistical method that combines the results of multiple studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic. This can help identify patterns or inconsistencies across studies.

- Consultation with experts : Consulting with experts in the field can provide valuable insights into the quality and relevance of a study. Experts can also help identify potential limitations or biases in the study.

- Review of funding sources: Examining the funding sources of a study can help identify any potential conflicts of interest or biases that may have influenced the study design or interpretation of results.

Example of Evaluating Research

Example of Evaluating Research sample for students:

Title of the Study: The Effects of Social Media Use on Mental Health among College Students

Sample Size: 500 college students

Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling

- Sample Size: The sample size of 500 college students is a moderate sample size, which could be considered representative of the college student population. However, it would be more representative if the sample size was larger, or if a random sampling technique was used.

- Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling technique, which means that the sample may not be representative of the population. This technique may introduce bias into the study since the participants are self-selected and may not be representative of the entire college student population. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other populations.

- Participant Characteristics: The study does not provide any information about the demographic characteristics of the participants, such as age, gender, race, or socioeconomic status. This information is important because social media use and mental health may vary among different demographic groups.

- Data Collection Method: The study used a self-administered survey to collect data. Self-administered surveys may be subject to response bias and may not accurately reflect participants’ actual behaviors and experiences.

- Data Analysis: The study used descriptive statistics and regression analysis to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics provide a summary of the data, while regression analysis is used to examine the relationship between two or more variables. However, the study did not provide information about the statistical significance of the results or the effect sizes.

Overall, while the study provides some insights into the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students, the use of a convenience sampling technique and the lack of information about participant characteristics limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the use of self-administered surveys may introduce bias into the study, and the lack of information about the statistical significance of the results limits the interpretation of the findings.

Note*: Above mentioned example is just a sample for students. Do not copy and paste directly into your assignment. Kindly do your own research for academic purposes.

Applications of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the applications of evaluating research:

- Identifying reliable sources : By evaluating research, researchers, students, and other professionals can identify the most reliable sources of information to use in their work. They can determine the quality of research studies, including the methodology, sample size, data analysis, and conclusions.

- Validating findings: Evaluating research can help to validate findings from previous studies. By examining the methodology and results of a study, researchers can determine if the findings are reliable and if they can be used to inform future research.

- Identifying knowledge gaps: Evaluating research can also help to identify gaps in current knowledge. By examining the existing literature on a topic, researchers can determine areas where more research is needed, and they can design studies to address these gaps.

- Improving research quality : Evaluating research can help to improve the quality of future research. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies, researchers can design better studies and avoid common pitfalls.

- Informing policy and decision-making : Evaluating research is crucial in informing policy and decision-making in many fields. By examining the evidence base for a particular issue, policymakers can make informed decisions that are supported by the best available evidence.

- Enhancing education : Evaluating research is essential in enhancing education. Educators can use research findings to improve teaching methods, curriculum development, and student outcomes.

Purpose of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the key purposes of evaluating research:

- Determine the reliability and validity of research findings : By evaluating research, researchers can determine the quality of the study design, data collection, and analysis. They can determine whether the findings are reliable, valid, and generalizable to other populations.

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies: Evaluating research helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies, including potential biases, confounding factors, and limitations. This information can help researchers to design better studies in the future.

- Inform evidence-based decision-making: Evaluating research is crucial in informing evidence-based decision-making in many fields, including healthcare, education, and public policy. Policymakers, educators, and clinicians rely on research evidence to make informed decisions.

- Identify research gaps : By evaluating research, researchers can identify gaps in the existing literature and design studies to address these gaps. This process can help to advance knowledge and improve the quality of research in a particular field.

- Ensure research ethics and integrity : Evaluating research helps to ensure that research studies are conducted ethically and with integrity. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines to protect the welfare and rights of study participants and to maintain the trust of the public.

Characteristics Evaluating Research

Characteristics Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Research question/hypothesis: A good research question or hypothesis should be clear, concise, and well-defined. It should address a significant problem or issue in the field and be grounded in relevant theory or prior research.

- Study design: The research design should be appropriate for answering the research question and be clearly described in the study. The study design should also minimize bias and confounding variables.

- Sampling : The sample should be representative of the population of interest and the sampling method should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Data collection : The data collection methods should be reliable and valid, and the data should be accurately recorded and analyzed.

- Results : The results should be presented clearly and accurately, and the statistical analysis should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Interpretation of results : The interpretation of the results should be based on the data and not influenced by personal biases or preconceptions.

- Generalizability: The study findings should be generalizable to the population of interest and relevant to other settings or contexts.

- Contribution to the field : The study should make a significant contribution to the field and advance our understanding of the research question or issue.

Advantages of Evaluating Research

Evaluating research has several advantages, including:

- Ensuring accuracy and validity : By evaluating research, we can ensure that the research is accurate, valid, and reliable. This ensures that the findings are trustworthy and can be used to inform decision-making.

- Identifying gaps in knowledge : Evaluating research can help identify gaps in knowledge and areas where further research is needed. This can guide future research and help build a stronger evidence base.

- Promoting critical thinking: Evaluating research requires critical thinking skills, which can be applied in other areas of life. By evaluating research, individuals can develop their critical thinking skills and become more discerning consumers of information.

- Improving the quality of research : Evaluating research can help improve the quality of research by identifying areas where improvements can be made. This can lead to more rigorous research methods and better-quality research.

- Informing decision-making: By evaluating research, we can make informed decisions based on the evidence. This is particularly important in fields such as medicine and public health, where decisions can have significant consequences.

- Advancing the field : Evaluating research can help advance the field by identifying new research questions and areas of inquiry. This can lead to the development of new theories and the refinement of existing ones.

Limitations of Evaluating Research

Limitations of Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Evaluating research can be time-consuming, particularly if the study is complex or requires specialized knowledge. This can be a barrier for individuals who are not experts in the field or who have limited time.

- Subjectivity : Evaluating research can be subjective, as different individuals may have different interpretations of the same study. This can lead to inconsistencies in the evaluation process and make it difficult to compare studies.

- Limited generalizability: The findings of a study may not be generalizable to other populations or contexts. This limits the usefulness of the study and may make it difficult to apply the findings to other settings.

- Publication bias: Research that does not find significant results may be less likely to be published, which can create a bias in the published literature. This can limit the amount of information available for evaluation.

- Lack of transparency: Some studies may not provide enough detail about their methods or results, making it difficult to evaluate their quality or validity.

- Funding bias : Research funded by particular organizations or industries may be biased towards the interests of the funder. This can influence the study design, methods, and interpretation of results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

- How to Write Evaluation Reports: Purpose, Structure, Content, Challenges, Tips, and Examples

- Learning Center

This article explores how to write effective evaluation reports, covering their purpose, structure, content, and common challenges. It provides tips for presenting evaluation findings effectively and using evaluation reports to improve programs and policies. Examples of well-written evaluation reports and templates are also included.

Table of Contents

What is an Evaluation Report?

What is the purpose of an evaluation report, importance of evaluation reports in program management, structure of evaluation report, best practices for writing an evaluation report, common challenges in writing an evaluation report, tips for presenting evaluation findings effectively, using evaluation reports to improve programs and policies, example of evaluation report templates, conclusion: making evaluation reports work for you.

An evaluatio n report is a document that presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations of an evaluation, which is a systematic and objective assessment of the performance, impact, and effectiveness of a program, project, policy, or intervention. The report typically includes a description of the evaluation’s purpose, scope, methodology, and data sources, as well as an analysis of the evaluation findings and conclusions, and specific recommendations for program or project improvement.

Evaluation reports can help to build capacity for monitoring and evaluation within organizations and communities, by promoting a culture of learning and continuous improvement. By providing a structured approach to evaluation and reporting, evaluation reports can help to ensure that evaluations are conducted consistently and rigorously, and that the results are communicated effectively to stakeholders.

Evaluation reports may be read by a wide variety of audiences, including persons working in government agencies, staff members working for donors and partners, students and community organisations, and development professionals working on projects or programmes that are comparable to the ones evaluated.

Related: Difference Between Evaluation Report and M&E Reports .

The purpose of an evaluation report is to provide stakeholders with a comprehensive and objective assessment of a program or project’s performance, achievements, and challenges. The report serves as a tool for decision-making, as it provides evidence-based information on the program or project’s strengths and weaknesses, and recommendations for improvement.

The main objectives of an evaluation report are:

- Accountability: To assess whether the program or project has met its objectives and delivered the intended results, and to hold stakeholders accountable for their actions and decisions.

- Learning : To identify the key lessons learned from the program or project, including best practices, challenges, and opportunities for improvement, and to apply these lessons to future programs or projects.

- Improvement : To provide recommendations for program or project improvement based on the evaluation findings and conclusions, and to support evidence-based decision-making.

- Communication : To communicate the evaluation findings and conclusions to stakeholders , including program staff, funders, policymakers, and the general public, and to promote transparency and stakeholder engagement.

An evaluation report should be clear, concise, and well-organized, and should provide stakeholders with a balanced and objective assessment of the program or project’s performance. The report should also be timely, with recommendations that are actionable and relevant to the current context. Overall, the purpose of an evaluation report is to promote accountability, learning, and improvement in program and project design and implementation.

Evaluation reports play a critical role in program management by providing valuable information about program effectiveness and efficiency. They offer insights into the extent to which programs have achieved their objectives, as well as identifying areas for improvement.

Evaluation reports help program managers and stakeholders to make informed decisions about program design, implementation, and funding. They provide evidence-based information that can be used to improve program outcomes and address challenges.

Moreover, evaluation reports are essential in demonstrating program accountability and transparency to funders, policymakers, and other stakeholders. They serve as a record of program activities and outcomes, allowing stakeholders to assess the program’s impact and sustainability.

In short, evaluation reports are a vital tool for program managers and evaluators. They provide a comprehensive picture of program performance, including strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. By utilizing evaluation reports, program managers can make informed decisions to improve program outcomes and ensure that their programs are effective, efficient, and sustainable over time.

The structure of an evaluation report can vary depending on the requirements and preferences of the stakeholders, but typically it includes the following sections:

- Executive Summary : A brief summary of the evaluation findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

- Introduction: An overview of the evaluation context, scope, purpose, and methodology.

- Background: A summary of the programme or initiative that is being assessed, including its goals, activities, and intended audience(s).

- Evaluation Questions : A list of the evaluation questions that guided the data collection and analysis.

- Methodology: A description of the data collection methods used in the evaluation, including the sampling strategy, data sources, and data analysis techniques.

- Findings: A presentation of the evaluation findings, organized according to the evaluation questions.

- Conclusions : A summary of the main evaluation findings and conclusions, including an assessment of the program or project’s effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability.

- Recommendations : A list of specific recommendations for program or project improvements based on the evaluation findings and conclusions.

- Lessons Learned : A discussion of the key lessons learned from the evaluation that could be applied to similar programs or projects in the future.

- Limitations : A discussion of the limitations of the evaluation, including any challenges or constraints encountered during the data collection and analysis.

- References: A list of references cited in the evaluation report.

- Appendices : Additional information, such as detailed data tables, graphs, or maps, that support the evaluation findings and conclusions.

The structure of the evaluation report should be clear, logical, and easy to follow, with headings and subheadings used to organize the content and facilitate navigation.

In addition, the presentation of data may be made more engaging and understandable by the use of visual aids such as graphs and charts.

Writing an effective evaluation report requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are some best practices to consider when writing an evaluation report:

Begin by establishing the report’s purpose, objectives, and target audience. A clear understanding of these elements will help guide the report’s structure and content.

Use clear and concise language throughout the report. Avoid jargon and technical terms that may be difficult for readers to understand.

Use evidence-based findings to support your conclusions and recommendations. Ensure that the findings are clearly presented using data tables, graphs, and charts.

Provide context for the evaluation by including a brief summary of the program being evaluated, its objectives, and intended impact. This will help readers understand the report’s purpose and the findings.

Include limitations and caveats in the report to provide a balanced assessment of the program’s effectiveness. Acknowledge any data limitations or other factors that may have influenced the evaluation’s results.

Organize the report in a logical manner, using headings and subheadings to break up the content. This will make the report easier to read and understand.

Ensure that the report is well-structured and easy to navigate. Use a clear and consistent formatting style throughout the report.

Finally, use the report to make actionable recommendations that will help improve program effectiveness and efficiency. Be specific about the steps that should be taken and the resources required to implement the recommendations.

By following these best practices, you can write an evaluation report that is clear, concise, and actionable, helping program managers and stakeholders to make informed decisions that improve program outcomes.

Catch HR’s eye instantly?

- Resume Review

- Resume Writing

- Resume Optimization

Premier global development resume service since 2012

Stand Out with a Pro Resume

Writing an evaluation report can be a challenging task, even for experienced evaluators. Here are some common challenges that evaluators may encounter when writing an evaluation report:

- Data limitations: One of the biggest challenges in writing an evaluation report is dealing with data limitations. Evaluators may find that the data they collected is incomplete, inaccurate, or difficult to interpret, making it challenging to draw meaningful conclusions.

- Stakeholder disagreements: Another common challenge is stakeholder disagreements over the evaluation’s findings and recommendations. Stakeholders may have different opinions about the program’s effectiveness or the best course of action to improve program outcomes.

- Technical writing skills: Evaluators may struggle with technical writing skills, which are essential for presenting complex evaluation findings in a clear and concise manner. Writing skills are particularly important when presenting statistical data or other technical information.

- Time constraints: Evaluators may face time constraints when writing evaluation reports, particularly if the report is needed quickly or the evaluation involved a large amount of data collection and analysis.

- Communication barriers: Evaluators may encounter communication barriers when working with stakeholders who speak different languages or have different cultural backgrounds. Effective communication is essential for ensuring that the evaluation’s findings are understood and acted upon.

By being aware of these common challenges, evaluators can take steps to address them and produce evaluation reports that are clear, accurate, and actionable. This may involve developing data collection and analysis plans that account for potential data limitations, engaging stakeholders early in the evaluation process to build consensus, and investing time in developing technical writing skills.

Presenting evaluation findings effectively is essential for ensuring that program managers and stakeholders understand the evaluation’s purpose, objectives, and conclusions. Here are some tips for presenting evaluation findings effectively:

- Know your audience: Before presenting evaluation findings, ensure that you have a clear understanding of your audience’s background, interests, and expertise. This will help you tailor your presentation to their needs and interests.

- Use visuals: Visual aids such as graphs, charts, and tables can help convey evaluation findings more effectively than written reports. Use visuals to highlight key data points and trends.

- Be concise: Keep your presentation concise and to the point. Focus on the key findings and conclusions, and avoid getting bogged down in technical details.

- Tell a story: Use the evaluation findings to tell a story about the program’s impact and effectiveness. This can help engage stakeholders and make the findings more memorable.

- Provide context: Provide context for the evaluation findings by explaining the program’s objectives and intended impact. This will help stakeholders understand the significance of the findings.

- Use plain language: Use plain language that is easily understandable by your target audience. Avoid jargon and technical terms that may confuse or alienate stakeholders.

- Engage stakeholders: Engage stakeholders in the presentation by asking for their input and feedback. This can help build consensus and ensure that the evaluation findings are acted upon.

By following these tips, you can present evaluation findings in a way that engages stakeholders, highlights key findings, and ensures that the evaluation’s conclusions are acted upon to improve program outcomes.

Evaluation reports are crucial tools for program managers and policymakers to assess program effectiveness and make informed decisions about program design, implementation, and funding. By analyzing data collected during the evaluation process, evaluation reports provide evidence-based information that can be used to improve program outcomes and impact.

One of the primary ways that evaluation reports can be used to improve programs and policies is by identifying program strengths and weaknesses. By assessing program effectiveness and efficiency, evaluation reports can help identify areas where programs are succeeding and areas where improvements are needed. This information can inform program redesign and improvement efforts, leading to better program outcomes and impact.

Evaluation reports can also be used to make data-driven decisions about program design, implementation, and funding. By providing decision-makers with data-driven information, evaluation reports can help ensure that programs are designed and implemented in a way that maximizes their impact and effectiveness. This information can also be used to allocate resources more effectively, directing funding towards programs that are most effective and efficient.

Another way that evaluation reports can be used to improve programs and policies is by disseminating best practices in program design and implementation. By sharing information about what works and what doesn’t work, evaluation reports can help program managers and policymakers make informed decisions about program design and implementation, leading to better outcomes and impact.

Finally, evaluation reports can inform policy development and improvement efforts by providing evidence about the effectiveness and impact of existing policies. This information can be used to make data-driven decisions about policy development and improvement efforts, ensuring that policies are designed and implemented in a way that maximizes their impact and effectiveness.

In summary, evaluation reports are critical tools for improving programs and policies. By providing evidence-based information about program effectiveness and efficiency, evaluation reports can help program managers and policymakers make informed decisions, allocate resources more effectively, disseminate best practices, and inform policy development and improvement efforts.

There are many different templates available for creating evaluation reports. Here are some examples of template evaluation reports that can be used as a starting point for creating your own report:

- The National Science Foundation Evaluation Report Template – This template provides a structure for evaluating research projects funded by the National Science Foundation. It includes sections on project background, research questions, evaluation methodology, data analysis, and conclusions and recommendations.

- The CDC Program Evaluation Template – This template, created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, provides a framework for evaluating public health programs. It includes sections on program description, evaluation questions, data sources, data analysis, and conclusions and recommendations.

- The World Bank Evaluation Report Template – This template, created by the World Bank, provides a structure for evaluating development projects. It includes sections on project background, evaluation methodology, data analysis, findings and conclusions, and recommendations.

- The European Commission Evaluation Report Template – This template provides a structure for evaluating European Union projects and programs. It includes sections on project description, evaluation objectives, evaluation methodology, findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

- The UNICEF Evaluation Report Template – This template provides a framework for evaluating UNICEF programs and projects. It includes sections on program description, evaluation questions, evaluation methodology, findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

These templates provide a structure for creating evaluation reports that are well-organized and easy to read. They can be customized to meet the specific needs of your program or project and help ensure that your evaluation report is comprehensive and includes all of the necessary components.

- World Health Organisations Reports

- Checkl ist for Assessing USAID Evaluation Reports

In conclusion, evaluation reports are essential tools for program managers and policymakers to assess program effectiveness and make informed decisions about program design, implementation, and funding. By analyzing data collected during the evaluation process, evaluation reports provide evidence-based information that can be used to improve program outcomes and impact.

To make evaluation reports work for you, it is important to plan ahead and establish clear objectives and target audiences. This will help guide the report’s structure and content and ensure that the report is tailored to the needs of its intended audience.

When writing an evaluation report, it is important to use clear and concise language, provide evidence-based findings, and offer actionable recommendations that can be used to improve program outcomes. Including context for the evaluation findings and acknowledging limitations and caveats will provide a balanced assessment of the program’s effectiveness and help build trust with stakeholders.

Presenting evaluation findings effectively requires knowing your audience, using visuals, being concise, telling a story, providing context, using plain language, and engaging stakeholders. By following these tips, you can present evaluation findings in a way that engages stakeholders, highlights key findings, and ensures that the evaluation’s conclusions are acted upon to improve program outcomes.

Finally, using evaluation reports to improve programs and policies requires identifying program strengths and weaknesses, making data-driven decisions, disseminating best practices, allocating resources effectively, and informing policy development and improvement efforts. By using evaluation reports in these ways, program managers and policymakers can ensure that their programs are effective, efficient, and sustainable over time.

Well understanding, the description of the general evaluation of report are clear with good arrangement and it help students to learn and make practices

Patrick Kapuot

Thankyou for very much for such detail information. Very comprehensively said.

hailemichael

very good explanation, thanks

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

How strong is my Resume?

Only 2% of resumes land interviews.

Land a better, higher-paying career

Jobs for You

Water, sanitation and hygiene advisor (wash) – usaid/drc.

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

Health Supply Chain Specialist – USAID/DRC

Chief of party – bosnia and herzegovina.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

Project Manager I

- United States

Business Development Associate

Director of finance and administration, request for information – collecting information on potential partners for local works evaluation.

- Washington, USA

Principal Field Monitors

Technical expert (health, wash, nutrition, education, child protection, hiv/aids, supplies), survey expert, data analyst, team leader, usaid-bha performance evaluation consultant.

- International Rescue Committee

Manager II, Institutional Support Program Implementation

Senior human resources associate, services you might be interested in, useful guides ....

How to Create a Strong Resume

Monitoring And Evaluation Specialist Resume

Resume Length for the International Development Sector

Types of Evaluation

Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL)

LAND A JOB REFERRAL IN 2 WEEKS (NO ONLINE APPS!)

Sign Up & To Get My Free Referral Toolkit Now:

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Evaluation Research: Definition, Methods and Examples

Content Index

- What is evaluation research

- Why do evaluation research

Quantitative methods

Qualitative methods.

- Process evaluation research question examples

- Outcome evaluation research question examples

What is evaluation research?

Evaluation research, also known as program evaluation, refers to research purpose instead of a specific method. Evaluation research is the systematic assessment of the worth or merit of time, money, effort and resources spent in order to achieve a goal.

Evaluation research is closely related to but slightly different from more conventional social research . It uses many of the same methods used in traditional social research, but because it takes place within an organizational context, it requires team skills, interpersonal skills, management skills, political smartness, and other research skills that social research does not need much. Evaluation research also requires one to keep in mind the interests of the stakeholders.

Evaluation research is a type of applied research, and so it is intended to have some real-world effect. Many methods like surveys and experiments can be used to do evaluation research. The process of evaluation research consisting of data analysis and reporting is a rigorous, systematic process that involves collecting data about organizations, processes, projects, services, and/or resources. Evaluation research enhances knowledge and decision-making, and leads to practical applications.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Why do evaluation research?

The common goal of most evaluations is to extract meaningful information from the audience and provide valuable insights to evaluators such as sponsors, donors, client-groups, administrators, staff, and other relevant constituencies. Most often, feedback is perceived value as useful if it helps in decision-making. However, evaluation research does not always create an impact that can be applied anywhere else, sometimes they fail to influence short-term decisions. It is also equally true that initially, it might seem to not have any influence, but can have a delayed impact when the situation is more favorable. In spite of this, there is a general agreement that the major goal of evaluation research should be to improve decision-making through the systematic utilization of measurable feedback.

Below are some of the benefits of evaluation research

- Gain insights about a project or program and its operations

Evaluation Research lets you understand what works and what doesn’t, where we were, where we are and where we are headed towards. You can find out the areas of improvement and identify strengths. So, it will help you to figure out what do you need to focus more on and if there are any threats to your business. You can also find out if there are currently hidden sectors in the market that are yet untapped.

- Improve practice

It is essential to gauge your past performance and understand what went wrong in order to deliver better services to your customers. Unless it is a two-way communication, there is no way to improve on what you have to offer. Evaluation research gives an opportunity to your employees and customers to express how they feel and if there’s anything they would like to change. It also lets you modify or adopt a practice such that it increases the chances of success.

- Assess the effects

After evaluating the efforts, you can see how well you are meeting objectives and targets. Evaluations let you measure if the intended benefits are really reaching the targeted audience and if yes, then how effectively.

- Build capacity

Evaluations help you to analyze the demand pattern and predict if you will need more funds, upgrade skills and improve the efficiency of operations. It lets you find the gaps in the production to delivery chain and possible ways to fill them.

Methods of evaluation research

All market research methods involve collecting and analyzing the data, making decisions about the validity of the information and deriving relevant inferences from it. Evaluation research comprises of planning, conducting and analyzing the results which include the use of data collection techniques and applying statistical methods.

Some of the evaluation methods which are quite popular are input measurement, output or performance measurement, impact or outcomes assessment, quality assessment, process evaluation, benchmarking, standards, cost analysis, organizational effectiveness, program evaluation methods, and LIS-centered methods. There are also a few types of evaluations that do not always result in a meaningful assessment such as descriptive studies, formative evaluations, and implementation analysis. Evaluation research is more about information-processing and feedback functions of evaluation.

These methods can be broadly classified as quantitative and qualitative methods.

The outcome of the quantitative research methods is an answer to the questions below and is used to measure anything tangible.

- Who was involved?

- What were the outcomes?

- What was the price?

The best way to collect quantitative data is through surveys , questionnaires , and polls . You can also create pre-tests and post-tests, review existing documents and databases or gather clinical data.

Surveys are used to gather opinions, feedback or ideas of your employees or customers and consist of various question types . They can be conducted by a person face-to-face or by telephone, by mail, or online. Online surveys do not require the intervention of any human and are far more efficient and practical. You can see the survey results on dashboard of research tools and dig deeper using filter criteria based on various factors such as age, gender, location, etc. You can also keep survey logic such as branching, quotas, chain survey, looping, etc in the survey questions and reduce the time to both create and respond to the donor survey . You can also generate a number of reports that involve statistical formulae and present data that can be readily absorbed in the meetings. To learn more about how research tool works and whether it is suitable for you, sign up for a free account now.

Create a free account!

Quantitative data measure the depth and breadth of an initiative, for instance, the number of people who participated in the non-profit event, the number of people who enrolled for a new course at the university. Quantitative data collected before and after a program can show its results and impact.

The accuracy of quantitative data to be used for evaluation research depends on how well the sample represents the population, the ease of analysis, and their consistency. Quantitative methods can fail if the questions are not framed correctly and not distributed to the right audience. Also, quantitative data do not provide an understanding of the context and may not be apt for complex issues.

Learn more: Quantitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Qualitative research methods are used where quantitative methods cannot solve the research problem , i.e. they are used to measure intangible values. They answer questions such as

- What is the value added?

- How satisfied are you with our service?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your friends?

- What will improve your experience?

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

Qualitative data is collected through observation, interviews, case studies, and focus groups. The steps for creating a qualitative study involve examining, comparing and contrasting, and understanding patterns. Analysts conclude after identification of themes, clustering similar data, and finally reducing to points that make sense.

Observations may help explain behaviors as well as the social context that is generally not discovered by quantitative methods. Observations of behavior and body language can be done by watching a participant, recording audio or video. Structured interviews can be conducted with people alone or in a group under controlled conditions, or they may be asked open-ended qualitative research questions . Qualitative research methods are also used to understand a person’s perceptions and motivations.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

The strength of this method is that group discussion can provide ideas and stimulate memories with topics cascading as discussion occurs. The accuracy of qualitative data depends on how well contextual data explains complex issues and complements quantitative data. It helps get the answer of “why” and “how”, after getting an answer to “what”. The limitations of qualitative data for evaluation research are that they are subjective, time-consuming, costly and difficult to analyze and interpret.

Learn more: Qualitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Survey software can be used for both the evaluation research methods. You can use above sample questions for evaluation research and send a survey in minutes using research software. Using a tool for research simplifies the process right from creating a survey, importing contacts, distributing the survey and generating reports that aid in research.

Examples of evaluation research

Evaluation research questions lay the foundation of a successful evaluation. They define the topics that will be evaluated. Keeping evaluation questions ready not only saves time and money, but also makes it easier to decide what data to collect, how to analyze it, and how to report it.

Evaluation research questions must be developed and agreed on in the planning stage, however, ready-made research templates can also be used.

Process evaluation research question examples:

- How often do you use our product in a day?

- Were approvals taken from all stakeholders?

- Can you report the issue from the system?

- Can you submit the feedback from the system?

- Was each task done as per the standard operating procedure?

- What were the barriers to the implementation of each task?

- Were any improvement areas discovered?

Outcome evaluation research question examples:

- How satisfied are you with our product?

- Did the program produce intended outcomes?

- What were the unintended outcomes?

- Has the program increased the knowledge of participants?

- Were the participants of the program employable before the course started?

- Do participants of the program have the skills to find a job after the course ended?

- Is the knowledge of participants better compared to those who did not participate in the program?

MORE LIKE THIS

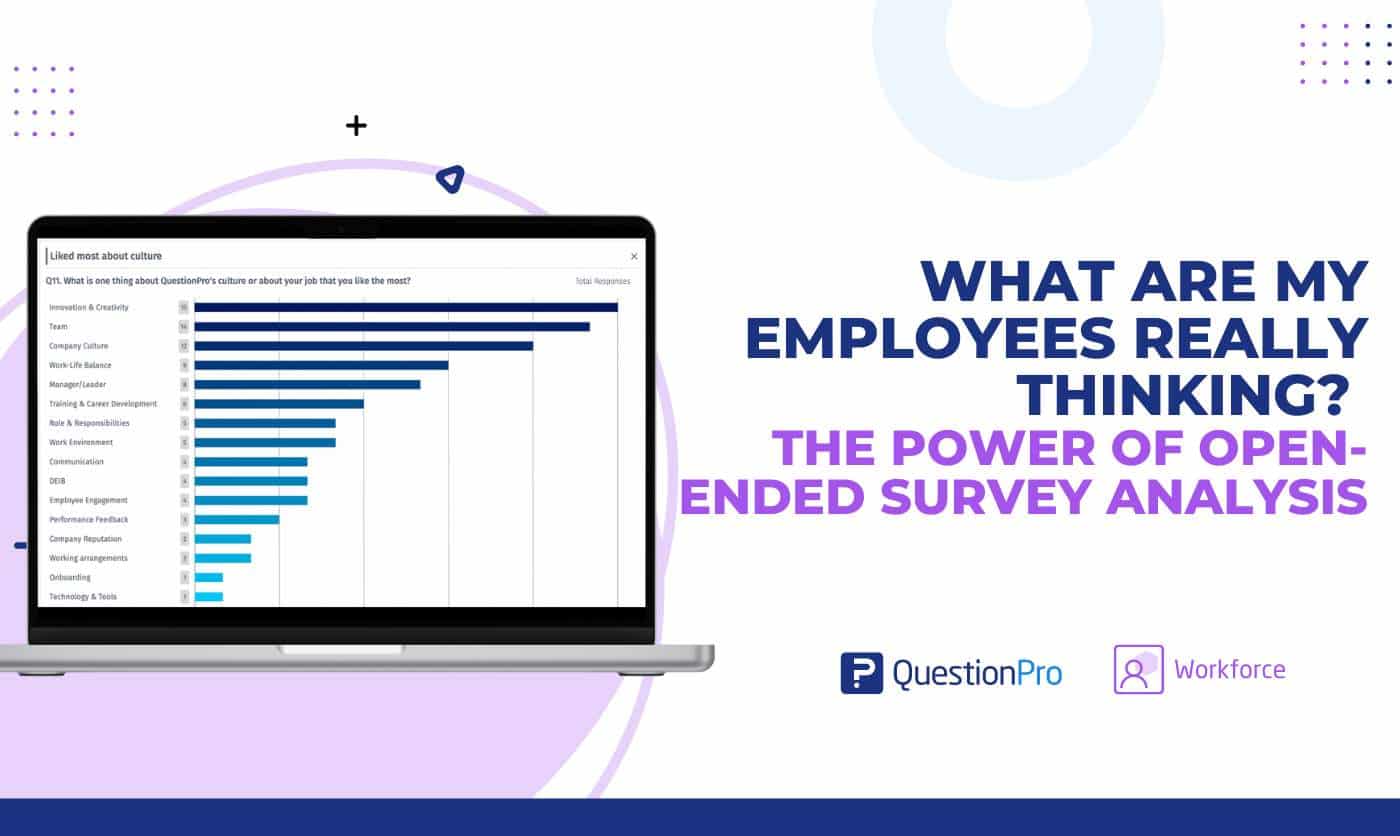

What Are My Employees Really Thinking? The Power of Open-ended Survey Analysis

May 24, 2024

I Am Disconnected – Tuesday CX Thoughts

May 21, 2024

20 Best Customer Success Tools of 2024

May 20, 2024

AI-Based Services Buying Guide for Market Research (based on ESOMAR’s 20 Questions)

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Panel on the Evaluation of AIDS Interventions; Coyle SL, Boruch RF, Turner CF, editors. Evaluating AIDS Prevention Programs: Expanded Edition. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1991.

Evaluating AIDS Prevention Programs: Expanded Edition.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

1 Design and Implementation of Evaluation Research

Evaluation has its roots in the social, behavioral, and statistical sciences, and it relies on their principles and methodologies of research, including experimental design, measurement, statistical tests, and direct observation. What distinguishes evaluation research from other social science is that its subjects are ongoing social action programs that are intended to produce individual or collective change. This setting usually engenders a great need for cooperation between those who conduct the program and those who evaluate it. This need for cooperation can be particularly acute in the case of AIDS prevention programs because those programs have been developed rapidly to meet the urgent demands of a changing and deadly epidemic.

Although the characteristics of AIDS intervention programs place some unique demands on evaluation, the techniques for conducting good program evaluation do not need to be invented. Two decades of evaluation research have provided a basic conceptual framework for undertaking such efforts (see, e.g., Campbell and Stanley [1966] and Cook and Campbell [1979] for discussions of outcome evaluation; see Weiss [1972] and Rossi and Freeman [1982] for process and outcome evaluations); in addition, similar programs, such as the antismoking campaigns, have been subject to evaluation, and they offer examples of the problems that have been encountered.

In this chapter the panel provides an overview of the terminology, types, designs, and management of research evaluation. The following chapter provides an overview of program objectives and the selection and measurement of appropriate outcome variables for judging the effectiveness of AIDS intervention programs. These issues are discussed in detail in the subsequent, program-specific Chapters 3 - 5 .

- Types of Evaluation

The term evaluation implies a variety of different things to different people. The recent report of the Committee on AIDS Research and the Behavioral, Social, and Statistical Sciences defines the area through a series of questions (Turner, Miller, and Moses, 1989:317-318):

Evaluation is a systematic process that produces a trustworthy account of what was attempted and why; through the examination of results—the outcomes of intervention programs—it answers the questions, "What was done?" "To whom, and how?" and "What outcomes were observed?'' Well-designed evaluation permits us to draw inferences from the data and addresses the difficult question: ''What do the outcomes mean?"

These questions differ in the degree of difficulty of answering them. An evaluation that tries to determine the outcomes of an intervention and what those outcomes mean is a more complicated endeavor than an evaluation that assesses the process by which the intervention was delivered. Both kinds of evaluation are necessary because they are intimately connected: to establish a project's success, an evaluator must first ask whether the project was implemented as planned and then whether its objective was achieved. Questions about a project's implementation usually fall under the rubric of process evaluation . If the investigation involves rapid feedback to the project staff or sponsors, particularly at the earliest stages of program implementation, the work is called formative evaluation . Questions about effects or effectiveness are often variously called summative evaluation, impact assessment, or outcome evaluation, the term the panel uses.

Formative evaluation is a special type of early evaluation that occurs during and after a program has been designed but before it is broadly implemented. Formative evaluation is used to understand the need for the intervention and to make tentative decisions about how to implement or improve it. During formative evaluation, information is collected and then fed back to program designers and administrators to enhance program development and maximize the success of the intervention. For example, formative evaluation may be carried out through a pilot project before a program is implemented at several sites. A pilot study of a community-based organization (CBO), for example, might be used to gather data on problems involving access to and recruitment of targeted populations and the utilization and implementation of services; the findings of such a study would then be used to modify (if needed) the planned program.

Another example of formative evaluation is the use of a "story board" design of a TV message that has yet to be produced. A story board is a series of text and sketches of camera shots that are to be produced in a commercial. To evaluate the effectiveness of the message and forecast some of the consequences of actually broadcasting it to the general public, an advertising agency convenes small groups of people to react to and comment on the proposed design.

Once an intervention has been implemented, the next stage of evaluation is process evaluation, which addresses two broad questions: "What was done?" and "To whom, and how?" Ordinarily, process evaluation is carried out at some point in the life of a project to determine how and how well the delivery goals of the program are being met. When intervention programs continue over a long period of time (as is the case for some of the major AIDS prevention programs), measurements at several times are warranted to ensure that the components of the intervention continue to be delivered by the right people, to the right people, in the right manner, and at the right time. Process evaluation can also play a role in improving interventions by providing the information necessary to change delivery strategies or program objectives in a changing epidemic.

Research designs for process evaluation include direct observation of projects, surveys of service providers and clients, and the monitoring of administrative records. The panel notes that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is already collecting some administrative records on its counseling and testing program and community-based projects. The panel believes that this type of evaluation should be a continuing and expanded component of intervention projects to guarantee the maintenance of the projects' integrity and responsiveness to their constituencies.

The purpose of outcome evaluation is to identify consequences and to establish that consequences are, indeed, attributable to a project. This type of evaluation answers the questions, "What outcomes were observed?" and, perhaps more importantly, "What do the outcomes mean?" Like process evaluation, outcome evaluation can also be conducted at intervals during an ongoing program, and the panel believes that such periodic evaluation should be done to monitor goal achievement.

The panel believes that these stages of evaluation (i.e., formative, process, and outcome) are essential to learning how AIDS prevention programs contribute to containing the epidemic. After a body of findings has been accumulated from such evaluations, it may be fruitful to launch another stage of evaluation: cost-effectiveness analysis (see Weinstein et al., 1989). Like outcome evaluation, cost-effectiveness analysis also measures program effectiveness, but it extends the analysis by adding a measure of program cost. The panel believes that consideration of cost-effective analysis should be postponed until more experience is gained with formative, process, and outcome evaluation of the CDC AIDS prevention programs.

- Evaluation Research Design

Process and outcome evaluations require different types of research designs, as discussed below. Formative evaluations, which are intended to both assess implementation and forecast effects, use a mix of these designs.

Process Evaluation Designs

To conduct process evaluations on how well services are delivered, data need to be gathered on the content of interventions and on their delivery systems. Suggested methodologies include direct observation, surveys, and record keeping.

Direct observation designs include case studies, in which participant-observers unobtrusively and systematically record encounters within a program setting, and nonparticipant observation, in which long, open-ended (or "focused") interviews are conducted with program participants. 1 For example, "professional customers" at counseling and testing sites can act as project clients to monitor activities unobtrusively; 2 alternatively, nonparticipant observers can interview both staff and clients. Surveys —either censuses (of the whole population of interest) or samples—elicit information through interviews or questionnaires completed by project participants or potential users of a project. For example, surveys within community-based projects can collect basic statistical information on project objectives, what services are provided, to whom, when, how often, for how long, and in what context.

Record keeping consists of administrative or other reporting systems that monitor use of services. Standardized reporting ensures consistency in the scope and depth of data collected. To use the media campaign as an example, the panel suggests using standardized data on the use of the AIDS hotline to monitor public attentiveness to the advertisements broadcast by the media campaign.

These designs are simple to understand, but they require expertise to implement. For example, observational studies must be conducted by people who are well trained in how to carry out on-site tasks sensitively and to record their findings uniformly. Observers can either complete narrative accounts of what occurred in a service setting or they can complete some sort of data inventory to ensure that multiple aspects of service delivery are covered. These types of studies are time consuming and benefit from corroboration among several observers. The use of surveys in research is well-understood, although they, too, require expertise to be well implemented. As the program chapters reflect, survey data collection must be carefully designed to reduce problems of validity and reliability and, if samples are used, to design an appropriate sampling scheme. Record keeping or service inventories are probably the easiest research designs to implement, although preparing standardized internal forms requires attention to detail about salient aspects of service delivery.

Outcome Evaluation Designs

Research designs for outcome evaluations are meant to assess principal and relative effects. Ideally, to assess the effect of an intervention on program participants, one would like to know what would have happened to the same participants in the absence of the program. Because it is not possible to make this comparison directly, inference strategies that rely on proxies have to be used. Scientists use three general approaches to construct proxies for use in the comparisons required to evaluate the effects of interventions: (1) nonexperimental methods, (2) quasi-experiments, and (3) randomized experiments. The first two are discussed below, and randomized experiments are discussed in the subsequent section.

Nonexperimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs 3

The most common form of nonexperimental design is a before-and-after study. In this design, pre-intervention measurements are compared with equivalent measurements made after the intervention to detect change in the outcome variables that the intervention was designed to influence.

Although the panel finds that before-and-after studies frequently provide helpful insights, the panel believes that these studies do not provide sufficiently reliable information to be the cornerstone for evaluation research on the effectiveness of AIDS prevention programs. The panel's conclusion follows from the fact that the postintervention changes cannot usually be attributed unambiguously to the intervention. 4 Plausible competing explanations for differences between pre-and postintervention measurements will often be numerous, including not only the possible effects of other AIDS intervention programs, news stories, and local events, but also the effects that may result from the maturation of the participants and the educational or sensitizing effects of repeated measurements, among others.