Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

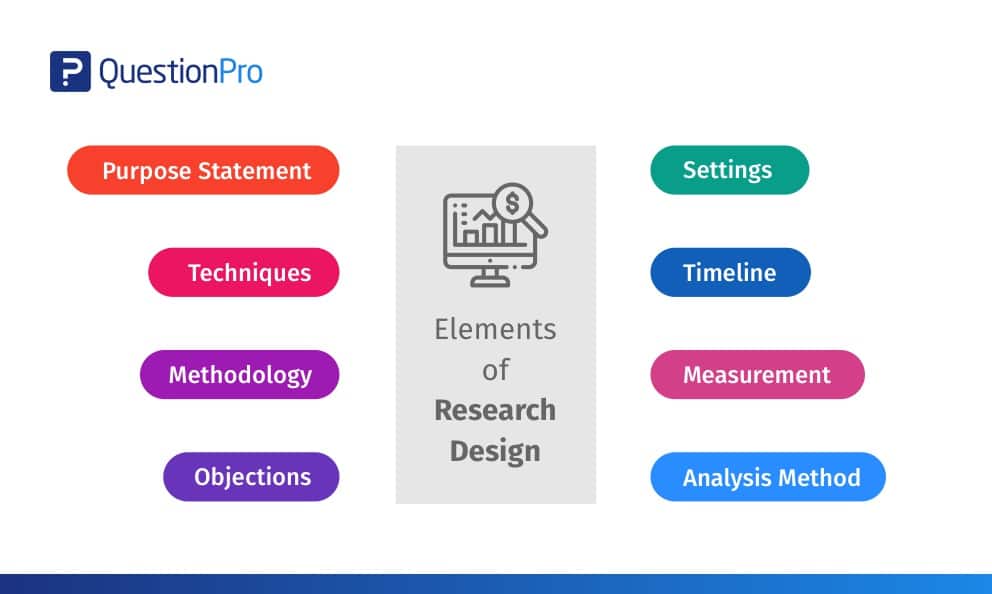

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

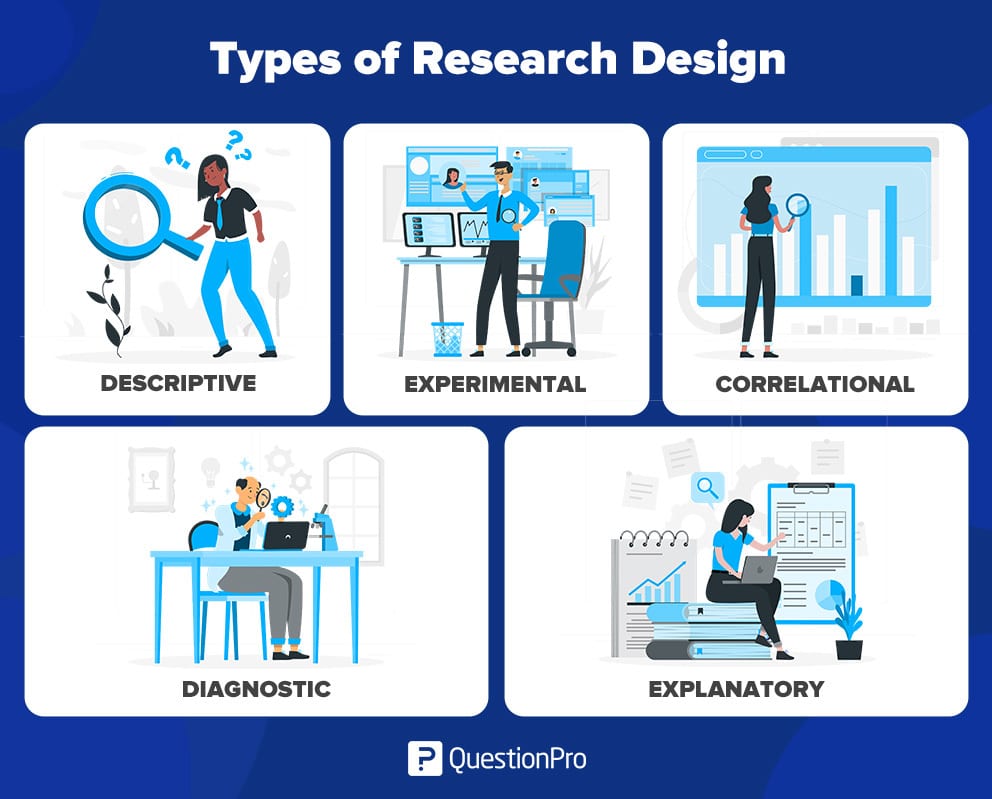

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Types of Research Designs

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Introduction

Before beginning your paper, you need to decide how you plan to design the study .

The research design refers to the overall strategy and analytical approach that you have chosen in order to integrate, in a coherent and logical way, the different components of the study, thus ensuring that the research problem will be thoroughly investigated. It constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measurement, and interpretation of information and data. Note that the research problem determines the type of design you choose, not the other way around!

De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

General Structure and Writing Style

The function of a research design is to ensure that the evidence obtained enables you to effectively address the research problem logically and as unambiguously as possible . In social sciences research, obtaining information relevant to the research problem generally entails specifying the type of evidence needed to test the underlying assumptions of a theory, to evaluate a program, or to accurately describe and assess meaning related to an observable phenomenon.

With this in mind, a common mistake made by researchers is that they begin their investigations before they have thought critically about what information is required to address the research problem. Without attending to these design issues beforehand, the overall research problem will not be adequately addressed and any conclusions drawn will run the risk of being weak and unconvincing. As a consequence, the overall validity of the study will be undermined.

The length and complexity of describing the research design in your paper can vary considerably, but any well-developed description will achieve the following :

- Identify the research problem clearly and justify its selection, particularly in relation to any valid alternative designs that could have been used,

- Review and synthesize previously published literature associated with the research problem,

- Clearly and explicitly specify hypotheses [i.e., research questions] central to the problem,

- Effectively describe the information and/or data which will be necessary for an adequate testing of the hypotheses and explain how such information and/or data will be obtained, and

- Describe the methods of analysis to be applied to the data in determining whether or not the hypotheses are true or false.

The research design is usually incorporated into the introduction of your paper . You can obtain an overall sense of what to do by reviewing studies that have utilized the same research design [e.g., using a case study approach]. This can help you develop an outline to follow for your own paper.

NOTE : Use the SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases and the SAGE Research Methods Videos databases to search for scholarly resources on how to apply specific research designs and methods . The Research Methods Online database contains links to more than 175,000 pages of SAGE publisher's book, journal, and reference content on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methodologies. Also included is a collection of case studies of social research projects that can be used to help you better understand abstract or complex methodological concepts. The Research Methods Videos database contains hours of tutorials, interviews, video case studies, and mini-documentaries covering the entire research process.

Creswell, John W. and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018; De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Leedy, Paul D. and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design . Tenth edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2013; Vogt, W. Paul, Dianna C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele. When to Use What Research Design . New York: Guilford, 2012.

Action Research Design

Definition and Purpose

The essentials of action research design follow a characteristic cycle whereby initially an exploratory stance is adopted, where an understanding of a problem is developed and plans are made for some form of interventionary strategy. Then the intervention is carried out [the "action" in action research] during which time, pertinent observations are collected in various forms. The new interventional strategies are carried out, and this cyclic process repeats, continuing until a sufficient understanding of [or a valid implementation solution for] the problem is achieved. The protocol is iterative or cyclical in nature and is intended to foster deeper understanding of a given situation, starting with conceptualizing and particularizing the problem and moving through several interventions and evaluations.

What do these studies tell you ?

- This is a collaborative and adaptive research design that lends itself to use in work or community situations.

- Design focuses on pragmatic and solution-driven research outcomes rather than testing theories.

- When practitioners use action research, it has the potential to increase the amount they learn consciously from their experience; the action research cycle can be regarded as a learning cycle.

- Action research studies often have direct and obvious relevance to improving practice and advocating for change.

- There are no hidden controls or preemption of direction by the researcher.

What these studies don't tell you ?

- It is harder to do than conducting conventional research because the researcher takes on responsibilities of advocating for change as well as for researching the topic.

- Action research is much harder to write up because it is less likely that you can use a standard format to report your findings effectively [i.e., data is often in the form of stories or observation].

- Personal over-involvement of the researcher may bias research results.

- The cyclic nature of action research to achieve its twin outcomes of action [e.g. change] and research [e.g. understanding] is time-consuming and complex to conduct.

- Advocating for change usually requires buy-in from study participants.

Coghlan, David and Mary Brydon-Miller. The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014; Efron, Sara Efrat and Ruth Ravid. Action Research in Education: A Practical Guide . New York: Guilford, 2013; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 18, Action Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Kemmis, Stephen and Robin McTaggart. “Participatory Action Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2000), pp. 567-605; McNiff, Jean. Writing and Doing Action Research . London: Sage, 2014; Reason, Peter and Hilary Bradbury. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001.

Case Study Design

A case study is an in-depth study of a particular research problem rather than a sweeping statistical survey or comprehensive comparative inquiry. It is often used to narrow down a very broad field of research into one or a few easily researchable examples. The case study research design is also useful for testing whether a specific theory and model actually applies to phenomena in the real world. It is a useful design when not much is known about an issue or phenomenon.

- Approach excels at bringing us to an understanding of a complex issue through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships.

- A researcher using a case study design can apply a variety of methodologies and rely on a variety of sources to investigate a research problem.

- Design can extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research.

- Social scientists, in particular, make wide use of this research design to examine contemporary real-life situations and provide the basis for the application of concepts and theories and the extension of methodologies.

- The design can provide detailed descriptions of specific and rare cases.

- A single or small number of cases offers little basis for establishing reliability or to generalize the findings to a wider population of people, places, or things.

- Intense exposure to the study of a case may bias a researcher's interpretation of the findings.

- Design does not facilitate assessment of cause and effect relationships.

- Vital information may be missing, making the case hard to interpret.

- The case may not be representative or typical of the larger problem being investigated.

- If the criteria for selecting a case is because it represents a very unusual or unique phenomenon or problem for study, then your interpretation of the findings can only apply to that particular case.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 4, Flexible Methods: Case Study Design. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Greenhalgh, Trisha, editor. Case Study Evaluation: Past, Present and Future Challenges . Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2015; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1995; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Theory . Applied Social Research Methods Series, no. 5. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003.

Causal Design

Causality studies may be thought of as understanding a phenomenon in terms of conditional statements in the form, “If X, then Y.” This type of research is used to measure what impact a specific change will have on existing norms and assumptions. Most social scientists seek causal explanations that reflect tests of hypotheses. Causal effect (nomothetic perspective) occurs when variation in one phenomenon, an independent variable, leads to or results, on average, in variation in another phenomenon, the dependent variable.

Conditions necessary for determining causality:

- Empirical association -- a valid conclusion is based on finding an association between the independent variable and the dependent variable.

- Appropriate time order -- to conclude that causation was involved, one must see that cases were exposed to variation in the independent variable before variation in the dependent variable.

- Nonspuriousness -- a relationship between two variables that is not due to variation in a third variable.

- Causality research designs assist researchers in understanding why the world works the way it does through the process of proving a causal link between variables and by the process of eliminating other possibilities.

- Replication is possible.

- There is greater confidence the study has internal validity due to the systematic subject selection and equity of groups being compared.

- Not all relationships are causal! The possibility always exists that, by sheer coincidence, two unrelated events appear to be related [e.g., Punxatawney Phil could accurately predict the duration of Winter for five consecutive years but, the fact remains, he's just a big, furry rodent].

- Conclusions about causal relationships are difficult to determine due to a variety of extraneous and confounding variables that exist in a social environment. This means causality can only be inferred, never proven.

- If two variables are correlated, the cause must come before the effect. However, even though two variables might be causally related, it can sometimes be difficult to determine which variable comes first and, therefore, to establish which variable is the actual cause and which is the actual effect.

Beach, Derek and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. Causal Case Study Methods: Foundations and Guidelines for Comparing, Matching, and Tracing . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016; Bachman, Ronet. The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice . Chapter 5, Causation and Research Designs. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 2007; Brewer, Ernest W. and Jennifer Kubn. “Causal-Comparative Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 125-132; Causal Research Design: Experimentation. Anonymous SlideShare Presentation; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 11, Nonexperimental Research: Correlational Designs. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

Cohort Design

Often used in the medical sciences, but also found in the applied social sciences, a cohort study generally refers to a study conducted over a period of time involving members of a population which the subject or representative member comes from, and who are united by some commonality or similarity. Using a quantitative framework, a cohort study makes note of statistical occurrence within a specialized subgroup, united by same or similar characteristics that are relevant to the research problem being investigated, rather than studying statistical occurrence within the general population. Using a qualitative framework, cohort studies generally gather data using methods of observation. Cohorts can be either "open" or "closed."

- Open Cohort Studies [dynamic populations, such as the population of Los Angeles] involve a population that is defined just by the state of being a part of the study in question (and being monitored for the outcome). Date of entry and exit from the study is individually defined, therefore, the size of the study population is not constant. In open cohort studies, researchers can only calculate rate based data, such as, incidence rates and variants thereof.

- Closed Cohort Studies [static populations, such as patients entered into a clinical trial] involve participants who enter into the study at one defining point in time and where it is presumed that no new participants can enter the cohort. Given this, the number of study participants remains constant (or can only decrease).

- The use of cohorts is often mandatory because a randomized control study may be unethical. For example, you cannot deliberately expose people to asbestos, you can only study its effects on those who have already been exposed. Research that measures risk factors often relies upon cohort designs.

- Because cohort studies measure potential causes before the outcome has occurred, they can demonstrate that these “causes” preceded the outcome, thereby avoiding the debate as to which is the cause and which is the effect.

- Cohort analysis is highly flexible and can provide insight into effects over time and related to a variety of different types of changes [e.g., social, cultural, political, economic, etc.].

- Either original data or secondary data can be used in this design.

- In cases where a comparative analysis of two cohorts is made [e.g., studying the effects of one group exposed to asbestos and one that has not], a researcher cannot control for all other factors that might differ between the two groups. These factors are known as confounding variables.

- Cohort studies can end up taking a long time to complete if the researcher must wait for the conditions of interest to develop within the group. This also increases the chance that key variables change during the course of the study, potentially impacting the validity of the findings.

- Due to the lack of randominization in the cohort design, its external validity is lower than that of study designs where the researcher randomly assigns participants.

Healy P, Devane D. “Methodological Considerations in Cohort Study Designs.” Nurse Researcher 18 (2011): 32-36; Glenn, Norval D, editor. Cohort Analysis . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Levin, Kate Ann. Study Design IV: Cohort Studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry 7 (2003): 51–52; Payne, Geoff. “Cohort Study.” In The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods . Victor Jupp, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), pp. 31-33; Study Design 101. Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. George Washington University, November 2011; Cohort Study. Wikipedia.

Cross-Sectional Design

Cross-sectional research designs have three distinctive features: no time dimension; a reliance on existing differences rather than change following intervention; and, groups are selected based on existing differences rather than random allocation. The cross-sectional design can only measure differences between or from among a variety of people, subjects, or phenomena rather than a process of change. As such, researchers using this design can only employ a relatively passive approach to making causal inferences based on findings.

- Cross-sectional studies provide a clear 'snapshot' of the outcome and the characteristics associated with it, at a specific point in time.

- Unlike an experimental design, where there is an active intervention by the researcher to produce and measure change or to create differences, cross-sectional designs focus on studying and drawing inferences from existing differences between people, subjects, or phenomena.

- Entails collecting data at and concerning one point in time. While longitudinal studies involve taking multiple measures over an extended period of time, cross-sectional research is focused on finding relationships between variables at one moment in time.

- Groups identified for study are purposely selected based upon existing differences in the sample rather than seeking random sampling.

- Cross-section studies are capable of using data from a large number of subjects and, unlike observational studies, is not geographically bound.

- Can estimate prevalence of an outcome of interest because the sample is usually taken from the whole population.

- Because cross-sectional designs generally use survey techniques to gather data, they are relatively inexpensive and take up little time to conduct.

- Finding people, subjects, or phenomena to study that are very similar except in one specific variable can be difficult.

- Results are static and time bound and, therefore, give no indication of a sequence of events or reveal historical or temporal contexts.

- Studies cannot be utilized to establish cause and effect relationships.

- This design only provides a snapshot of analysis so there is always the possibility that a study could have differing results if another time-frame had been chosen.

- There is no follow up to the findings.

Bethlehem, Jelke. "7: Cross-sectional Research." In Research Methodology in the Social, Behavioural and Life Sciences . Herman J Adèr and Gideon J Mellenbergh, editors. (London, England: Sage, 1999), pp. 110-43; Bourque, Linda B. “Cross-Sectional Design.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman, and Tim Futing Liao. (Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004), pp. 230-231; Hall, John. “Cross-Sectional Survey Design.” In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 173-174; Helen Barratt, Maria Kirwan. Cross-Sectional Studies: Design Application, Strengths and Weaknesses of Cross-Sectional Studies. Healthknowledge, 2009. Cross-Sectional Study. Wikipedia.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research designs help provide answers to the questions of who, what, when, where, and how associated with a particular research problem; a descriptive study cannot conclusively ascertain answers to why. Descriptive research is used to obtain information concerning the current status of the phenomena and to describe "what exists" with respect to variables or conditions in a situation.

- The subject is being observed in a completely natural and unchanged natural environment. True experiments, whilst giving analyzable data, often adversely influence the normal behavior of the subject [a.k.a., the Heisenberg effect whereby measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems].

- Descriptive research is often used as a pre-cursor to more quantitative research designs with the general overview giving some valuable pointers as to what variables are worth testing quantitatively.

- If the limitations are understood, they can be a useful tool in developing a more focused study.

- Descriptive studies can yield rich data that lead to important recommendations in practice.

- Appoach collects a large amount of data for detailed analysis.

- The results from a descriptive research cannot be used to discover a definitive answer or to disprove a hypothesis.

- Because descriptive designs often utilize observational methods [as opposed to quantitative methods], the results cannot be replicated.

- The descriptive function of research is heavily dependent on instrumentation for measurement and observation.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 5, Flexible Methods: Descriptive Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Given, Lisa M. "Descriptive Research." In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics . Neil J. Salkind and Kristin Rasmussen, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007), pp. 251-254; McNabb, Connie. Descriptive Research Methodologies. Powerpoint Presentation; Shuttleworth, Martyn. Descriptive Research Design, September 26, 2008; Erickson, G. Scott. "Descriptive Research Design." In New Methods of Market Research and Analysis . (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017), pp. 51-77; Sahin, Sagufta, and Jayanta Mete. "A Brief Study on Descriptive Research: Its Nature and Application in Social Science." International Journal of Research and Analysis in Humanities 1 (2021): 11; K. Swatzell and P. Jennings. “Descriptive Research: The Nuts and Bolts.” Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants 20 (2007), pp. 55-56; Kane, E. Doing Your Own Research: Basic Descriptive Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities . London: Marion Boyars, 1985.

Experimental Design

A blueprint of the procedure that enables the researcher to maintain control over all factors that may affect the result of an experiment. In doing this, the researcher attempts to determine or predict what may occur. Experimental research is often used where there is time priority in a causal relationship (cause precedes effect), there is consistency in a causal relationship (a cause will always lead to the same effect), and the magnitude of the correlation is great. The classic experimental design specifies an experimental group and a control group. The independent variable is administered to the experimental group and not to the control group, and both groups are measured on the same dependent variable. Subsequent experimental designs have used more groups and more measurements over longer periods. True experiments must have control, randomization, and manipulation.

- Experimental research allows the researcher to control the situation. In so doing, it allows researchers to answer the question, “What causes something to occur?”

- Permits the researcher to identify cause and effect relationships between variables and to distinguish placebo effects from treatment effects.

- Experimental research designs support the ability to limit alternative explanations and to infer direct causal relationships in the study.

- Approach provides the highest level of evidence for single studies.

- The design is artificial, and results may not generalize well to the real world.

- The artificial settings of experiments may alter the behaviors or responses of participants.

- Experimental designs can be costly if special equipment or facilities are needed.

- Some research problems cannot be studied using an experiment because of ethical or technical reasons.

- Difficult to apply ethnographic and other qualitative methods to experimentally designed studies.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 7, Flexible Methods: Experimental Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Chapter 2: Research Design, Experimental Designs. School of Psychology, University of New England, 2000; Chow, Siu L. "Experimental Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 448-453; "Experimental Design." In Social Research Methods . Nicholas Walliman, editor. (London, England: Sage, 2006), pp, 101-110; Experimental Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Kirk, Roger E. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Trochim, William M.K. Experimental Design. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Rasool, Shafqat. Experimental Research. Slideshare presentation.

Exploratory Design

An exploratory design is conducted about a research problem when there are few or no earlier studies to refer to or rely upon to predict an outcome . The focus is on gaining insights and familiarity for later investigation or undertaken when research problems are in a preliminary stage of investigation. Exploratory designs are often used to establish an understanding of how best to proceed in studying an issue or what methodology would effectively apply to gathering information about the issue.

The goals of exploratory research are intended to produce the following possible insights:

- Familiarity with basic details, settings, and concerns.

- Well grounded picture of the situation being developed.

- Generation of new ideas and assumptions.

- Development of tentative theories or hypotheses.

- Determination about whether a study is feasible in the future.

- Issues get refined for more systematic investigation and formulation of new research questions.

- Direction for future research and techniques get developed.

- Design is a useful approach for gaining background information on a particular topic.

- Exploratory research is flexible and can address research questions of all types (what, why, how).

- Provides an opportunity to define new terms and clarify existing concepts.

- Exploratory research is often used to generate formal hypotheses and develop more precise research problems.

- In the policy arena or applied to practice, exploratory studies help establish research priorities and where resources should be allocated.

- Exploratory research generally utilizes small sample sizes and, thus, findings are typically not generalizable to the population at large.

- The exploratory nature of the research inhibits an ability to make definitive conclusions about the findings. They provide insight but not definitive conclusions.

- The research process underpinning exploratory studies is flexible but often unstructured, leading to only tentative results that have limited value to decision-makers.

- Design lacks rigorous standards applied to methods of data gathering and analysis because one of the areas for exploration could be to determine what method or methodologies could best fit the research problem.

Cuthill, Michael. “Exploratory Research: Citizen Participation, Local Government, and Sustainable Development in Australia.” Sustainable Development 10 (2002): 79-89; Streb, Christoph K. "Exploratory Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos and Eiden Wiebe, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 372-374; Taylor, P. J., G. Catalano, and D.R.F. Walker. “Exploratory Analysis of the World City Network.” Urban Studies 39 (December 2002): 2377-2394; Exploratory Research. Wikipedia.

Field Research Design

Sometimes referred to as ethnography or participant observation, designs around field research encompass a variety of interpretative procedures [e.g., observation and interviews] rooted in qualitative approaches to studying people individually or in groups while inhabiting their natural environment as opposed to using survey instruments or other forms of impersonal methods of data gathering. Information acquired from observational research takes the form of “ field notes ” that involves documenting what the researcher actually sees and hears while in the field. Findings do not consist of conclusive statements derived from numbers and statistics because field research involves analysis of words and observations of behavior. Conclusions, therefore, are developed from an interpretation of findings that reveal overriding themes, concepts, and ideas. More information can be found HERE .

- Field research is often necessary to fill gaps in understanding the research problem applied to local conditions or to specific groups of people that cannot be ascertained from existing data.

- The research helps contextualize already known information about a research problem, thereby facilitating ways to assess the origins, scope, and scale of a problem and to gage the causes, consequences, and means to resolve an issue based on deliberate interaction with people in their natural inhabited spaces.

- Enables the researcher to corroborate or confirm data by gathering additional information that supports or refutes findings reported in prior studies of the topic.

- Because the researcher in embedded in the field, they are better able to make observations or ask questions that reflect the specific cultural context of the setting being investigated.

- Observing the local reality offers the opportunity to gain new perspectives or obtain unique data that challenges existing theoretical propositions or long-standing assumptions found in the literature.

What these studies don't tell you

- A field research study requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved with preparing for the gathering of information, including for example, examining background information about the study site, obtaining permission to access the study site, and building trust and rapport with subjects.

- Requires a commitment to staying engaged in the field to ensure that you can adequately document events and behaviors as they unfold.

- The unpredictable nature of fieldwork means that researchers can never fully control the process of data gathering. They must maintain a flexible approach to studying the setting because events and circumstances can change quickly or unexpectedly.

- Findings can be difficult to interpret and verify without access to documents and other source materials that help to enhance the credibility of information obtained from the field [i.e., the act of triangulating the data].

- Linking the research problem to the selection of study participants inhabiting their natural environment is critical. However, this specificity limits the ability to generalize findings to different situations or in other contexts or to infer courses of action applied to other settings or groups of people.

- The reporting of findings must take into account how the researcher themselves may have inadvertently affected respondents and their behaviors.

Historical Design

The purpose of a historical research design is to collect, verify, and synthesize evidence from the past to establish facts that defend or refute a hypothesis. It uses secondary sources and a variety of primary documentary evidence, such as, diaries, official records, reports, archives, and non-textual information [maps, pictures, audio and visual recordings]. The limitation is that the sources must be both authentic and valid.

- The historical research design is unobtrusive; the act of research does not affect the results of the study.

- The historical approach is well suited for trend analysis.

- Historical records can add important contextual background required to more fully understand and interpret a research problem.

- There is often no possibility of researcher-subject interaction that could affect the findings.

- Historical sources can be used over and over to study different research problems or to replicate a previous study.

- The ability to fulfill the aims of your research are directly related to the amount and quality of documentation available to understand the research problem.

- Since historical research relies on data from the past, there is no way to manipulate it to control for contemporary contexts.

- Interpreting historical sources can be very time consuming.

- The sources of historical materials must be archived consistently to ensure access. This may especially challenging for digital or online-only sources.

- Original authors bring their own perspectives and biases to the interpretation of past events and these biases are more difficult to ascertain in historical resources.

- Due to the lack of control over external variables, historical research is very weak with regard to the demands of internal validity.

- It is rare that the entirety of historical documentation needed to fully address a research problem is available for interpretation, therefore, gaps need to be acknowledged.

Howell, Martha C. and Walter Prevenier. From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001; Lundy, Karen Saucier. "Historical Research." In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods . Lisa M. Given, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 396-400; Marius, Richard. and Melvin E. Page. A Short Guide to Writing about History . 9th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2015; Savitt, Ronald. “Historical Research in Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 44 (Autumn, 1980): 52-58; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 16, Historical Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007.

Longitudinal Design

A longitudinal study follows the same sample over time and makes repeated observations. For example, with longitudinal surveys, the same group of people is interviewed at regular intervals, enabling researchers to track changes over time and to relate them to variables that might explain why the changes occur. Longitudinal research designs describe patterns of change and help establish the direction and magnitude of causal relationships. Measurements are taken on each variable over two or more distinct time periods. This allows the researcher to measure change in variables over time. It is a type of observational study sometimes referred to as a panel study.

- Longitudinal data facilitate the analysis of the duration of a particular phenomenon.

- Enables survey researchers to get close to the kinds of causal explanations usually attainable only with experiments.

- The design permits the measurement of differences or change in a variable from one period to another [i.e., the description of patterns of change over time].

- Longitudinal studies facilitate the prediction of future outcomes based upon earlier factors.

- The data collection method may change over time.

- Maintaining the integrity of the original sample can be difficult over an extended period of time.

- It can be difficult to show more than one variable at a time.

- This design often needs qualitative research data to explain fluctuations in the results.

- A longitudinal research design assumes present trends will continue unchanged.

- It can take a long period of time to gather results.

- There is a need to have a large sample size and accurate sampling to reach representativness.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 6, Flexible Methods: Relational and Longitudinal Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Forgues, Bernard, and Isabelle Vandangeon-Derumez. "Longitudinal Analyses." In Doing Management Research . Raymond-Alain Thiétart and Samantha Wauchope, editors. (London, England: Sage, 2001), pp. 332-351; Kalaian, Sema A. and Rafa M. Kasim. "Longitudinal Studies." In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 440-441; Menard, Scott, editor. Longitudinal Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002; Ployhart, Robert E. and Robert J. Vandenberg. "Longitudinal Research: The Theory, Design, and Analysis of Change.” Journal of Management 36 (January 2010): 94-120; Longitudinal Study. Wikipedia.

Meta-Analysis Design

Meta-analysis is an analytical methodology designed to systematically evaluate and summarize the results from a number of individual studies, thereby, increasing the overall sample size and the ability of the researcher to study effects of interest. The purpose is to not simply summarize existing knowledge, but to develop a new understanding of a research problem using synoptic reasoning. The main objectives of meta-analysis include analyzing differences in the results among studies and increasing the precision by which effects are estimated. A well-designed meta-analysis depends upon strict adherence to the criteria used for selecting studies and the availability of information in each study to properly analyze their findings. Lack of information can severely limit the type of analyzes and conclusions that can be reached. In addition, the more dissimilarity there is in the results among individual studies [heterogeneity], the more difficult it is to justify interpretations that govern a valid synopsis of results. A meta-analysis needs to fulfill the following requirements to ensure the validity of your findings:

- Clearly defined description of objectives, including precise definitions of the variables and outcomes that are being evaluated;

- A well-reasoned and well-documented justification for identification and selection of the studies;

- Assessment and explicit acknowledgment of any researcher bias in the identification and selection of those studies;

- Description and evaluation of the degree of heterogeneity among the sample size of studies reviewed; and,

- Justification of the techniques used to evaluate the studies.

- Can be an effective strategy for determining gaps in the literature.

- Provides a means of reviewing research published about a particular topic over an extended period of time and from a variety of sources.

- Is useful in clarifying what policy or programmatic actions can be justified on the basis of analyzing research results from multiple studies.

- Provides a method for overcoming small sample sizes in individual studies that previously may have had little relationship to each other.

- Can be used to generate new hypotheses or highlight research problems for future studies.

- Small violations in defining the criteria used for content analysis can lead to difficult to interpret and/or meaningless findings.

- A large sample size can yield reliable, but not necessarily valid, results.

- A lack of uniformity regarding, for example, the type of literature reviewed, how methods are applied, and how findings are measured within the sample of studies you are analyzing, can make the process of synthesis difficult to perform.

- Depending on the sample size, the process of reviewing and synthesizing multiple studies can be very time consuming.

Beck, Lewis W. "The Synoptic Method." The Journal of Philosophy 36 (1939): 337-345; Cooper, Harris, Larry V. Hedges, and Jeffrey C. Valentine, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis . 2nd edition. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009; Guzzo, Richard A., Susan E. Jackson and Raymond A. Katzell. “Meta-Analysis Analysis.” In Research in Organizational Behavior , Volume 9. (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1987), pp 407-442; Lipsey, Mark W. and David B. Wilson. Practical Meta-Analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001; Study Design 101. Meta-Analysis. The Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, George Washington University; Timulak, Ladislav. “Qualitative Meta-Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis . Uwe Flick, editor. (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2013), pp. 481-495; Walker, Esteban, Adrian V. Hernandez, and Micheal W. Kattan. "Meta-Analysis: It's Strengths and Limitations." Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 75 (June 2008): 431-439.

Mixed-Method Design

- Narrative and non-textual information can add meaning to numeric data, while numeric data can add precision to narrative and non-textual information.

- Can utilize existing data while at the same time generating and testing a grounded theory approach to describe and explain the phenomenon under study.

- A broader, more complex research problem can be investigated because the researcher is not constrained by using only one method.

- The strengths of one method can be used to overcome the inherent weaknesses of another method.

- Can provide stronger, more robust evidence to support a conclusion or set of recommendations.

- May generate new knowledge new insights or uncover hidden insights, patterns, or relationships that a single methodological approach might not reveal.

- Produces more complete knowledge and understanding of the research problem that can be used to increase the generalizability of findings applied to theory or practice.

- A researcher must be proficient in understanding how to apply multiple methods to investigating a research problem as well as be proficient in optimizing how to design a study that coherently melds them together.

- Can increase the likelihood of conflicting results or ambiguous findings that inhibit drawing a valid conclusion or setting forth a recommended course of action [e.g., sample interview responses do not support existing statistical data].

- Because the research design can be very complex, reporting the findings requires a well-organized narrative, clear writing style, and precise word choice.

- Design invites collaboration among experts. However, merging different investigative approaches and writing styles requires more attention to the overall research process than studies conducted using only one methodological paradigm.

- Concurrent merging of quantitative and qualitative research requires greater attention to having adequate sample sizes, using comparable samples, and applying a consistent unit of analysis. For sequential designs where one phase of qualitative research builds on the quantitative phase or vice versa, decisions about what results from the first phase to use in the next phase, the choice of samples and estimating reasonable sample sizes for both phases, and the interpretation of results from both phases can be difficult.

- Due to multiple forms of data being collected and analyzed, this design requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved in data gathering and interpretation.

Burch, Patricia and Carolyn J. Heinrich. Mixed Methods for Policy Research and Program Evaluation . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2016; Creswell, John w. et al. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences . Bethesda, MD: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health, 2010Creswell, John W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014; Domínguez, Silvia, editor. Mixed Methods Social Networks Research . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Hesse-Biber, Sharlene Nagy. Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice . New York: Guilford Press, 2010; Niglas, Katrin. “How the Novice Researcher Can Make Sense of Mixed Methods Designs.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 3 (2009): 34-46; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Nancy L. Leech. “Linking Research Questions to Mixed Methods Data Analysis Procedures.” The Qualitative Report 11 (September 2006): 474-498; Tashakorri, Abbas and John W. Creswell. “The New Era of Mixed Methods.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (January 2007): 3-7; Zhanga, Wanqing. “Mixed Methods Application in Health Intervention Research: A Multiple Case Study.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 8 (2014): 24-35 .

Observational Design

This type of research design draws a conclusion by comparing subjects against a control group, in cases where the researcher has no control over the experiment. There are two general types of observational designs. In direct observations, people know that you are watching them. Unobtrusive measures involve any method for studying behavior where individuals do not know they are being observed. An observational study allows a useful insight into a phenomenon and avoids the ethical and practical difficulties of setting up a large and cumbersome research project.

- Observational studies are usually flexible and do not necessarily need to be structured around a hypothesis about what you expect to observe [data is emergent rather than pre-existing].

- The researcher is able to collect in-depth information about a particular behavior.

- Can reveal interrelationships among multifaceted dimensions of group interactions.

- You can generalize your results to real life situations.

- Observational research is useful for discovering what variables may be important before applying other methods like experiments.

- Observation research designs account for the complexity of group behaviors.

- Reliability of data is low because seeing behaviors occur over and over again may be a time consuming task and are difficult to replicate.

- In observational research, findings may only reflect a unique sample population and, thus, cannot be generalized to other groups.

- There can be problems with bias as the researcher may only "see what they want to see."

- There is no possibility to determine "cause and effect" relationships since nothing is manipulated.

- Sources or subjects may not all be equally credible.

- Any group that is knowingly studied is altered to some degree by the presence of the researcher, therefore, potentially skewing any data collected.

Atkinson, Paul and Martyn Hammersley. “Ethnography and Participant Observation.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 248-261; Observational Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Patton Michael Quinn. Qualitiative Research and Evaluation Methods . Chapter 6, Fieldwork Strategies and Observational Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002; Payne, Geoff and Judy Payne. "Observation." In Key Concepts in Social Research . The SAGE Key Concepts series. (London, England: Sage, 2004), pp. 158-162; Rosenbaum, Paul R. Design of Observational Studies . New York: Springer, 2010;Williams, J. Patrick. "Nonparticipant Observation." In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods . Lisa M. Given, editor.(Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 562-563.

Philosophical Design

Understood more as an broad approach to examining a research problem than a methodological design, philosophical analysis and argumentation is intended to challenge deeply embedded, often intractable, assumptions underpinning an area of study. This approach uses the tools of argumentation derived from philosophical traditions, concepts, models, and theories to critically explore and challenge, for example, the relevance of logic and evidence in academic debates, to analyze arguments about fundamental issues, or to discuss the root of existing discourse about a research problem. These overarching tools of analysis can be framed in three ways:

- Ontology -- the study that describes the nature of reality; for example, what is real and what is not, what is fundamental and what is derivative?

- Epistemology -- the study that explores the nature of knowledge; for example, by what means does knowledge and understanding depend upon and how can we be certain of what we know?

- Axiology -- the study of values; for example, what values does an individual or group hold and why? How are values related to interest, desire, will, experience, and means-to-end? And, what is the difference between a matter of fact and a matter of value?

- Can provide a basis for applying ethical decision-making to practice.

- Functions as a means of gaining greater self-understanding and self-knowledge about the purposes of research.

- Brings clarity to general guiding practices and principles of an individual or group.

- Philosophy informs methodology.

- Refine concepts and theories that are invoked in relatively unreflective modes of thought and discourse.

- Beyond methodology, philosophy also informs critical thinking about epistemology and the structure of reality (metaphysics).

- Offers clarity and definition to the practical and theoretical uses of terms, concepts, and ideas.

- Limited application to specific research problems [answering the "So What?" question in social science research].

- Analysis can be abstract, argumentative, and limited in its practical application to real-life issues.

- While a philosophical analysis may render problematic that which was once simple or taken-for-granted, the writing can be dense and subject to unnecessary jargon, overstatement, and/or excessive quotation and documentation.

- There are limitations in the use of metaphor as a vehicle of philosophical analysis.

- There can be analytical difficulties in moving from philosophy to advocacy and between abstract thought and application to the phenomenal world.

Burton, Dawn. "Part I, Philosophy of the Social Sciences." In Research Training for Social Scientists . (London, England: Sage, 2000), pp. 1-5; Chapter 4, Research Methodology and Design. Unisa Institutional Repository (UnisaIR), University of South Africa; Jarvie, Ian C., and Jesús Zamora-Bonilla, editors. The SAGE Handbook of the Philosophy of Social Sciences . London: Sage, 2011; Labaree, Robert V. and Ross Scimeca. “The Philosophical Problem of Truth in Librarianship.” The Library Quarterly 78 (January 2008): 43-70; Maykut, Pamela S. Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide . Washington, DC: Falmer Press, 1994; McLaughlin, Hugh. "The Philosophy of Social Research." In Understanding Social Work Research . 2nd edition. (London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2012), pp. 24-47; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University, 2013.

Sequential Design

- The researcher has a limitless option when it comes to sample size and the sampling schedule.

- Due to the repetitive nature of this research design, minor changes and adjustments can be done during the initial parts of the study to correct and hone the research method.

- This is a useful design for exploratory studies.

- There is very little effort on the part of the researcher when performing this technique. It is generally not expensive, time consuming, or workforce intensive.

- Because the study is conducted serially, the results of one sample are known before the next sample is taken and analyzed. This provides opportunities for continuous improvement of sampling and methods of analysis.

- The sampling method is not representative of the entire population. The only possibility of approaching representativeness is when the researcher chooses to use a very large sample size significant enough to represent a significant portion of the entire population. In this case, moving on to study a second or more specific sample can be difficult.

- The design cannot be used to create conclusions and interpretations that pertain to an entire population because the sampling technique is not randomized. Generalizability from findings is, therefore, limited.

- Difficult to account for and interpret variation from one sample to another over time, particularly when using qualitative methods of data collection.

Betensky, Rebecca. Harvard University, Course Lecture Note slides; Bovaird, James A. and Kevin A. Kupzyk. "Sequential Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 1347-1352; Cresswell, John W. Et al. “Advanced Mixed-Methods Research Designs.” In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research . Abbas Tashakkori and Charles Teddle, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003), pp. 209-240; Henry, Gary T. "Sequential Sampling." In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman and Tim Futing Liao, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004), pp. 1027-1028; Nataliya V. Ivankova. “Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice.” Field Methods 18 (February 2006): 3-20; Bovaird, James A. and Kevin A. Kupzyk. “Sequential Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010; Sequential Analysis. Wikipedia.

Systematic Review

- A systematic review synthesizes the findings of multiple studies related to each other by incorporating strategies of analysis and interpretation intended to reduce biases and random errors.

- The application of critical exploration, evaluation, and synthesis methods separates insignificant, unsound, or redundant research from the most salient and relevant studies worthy of reflection.

- They can be use to identify, justify, and refine hypotheses, recognize and avoid hidden problems in prior studies, and explain data inconsistencies and conflicts in data.

- Systematic reviews can be used to help policy makers formulate evidence-based guidelines and regulations.

- The use of strict, explicit, and pre-determined methods of synthesis, when applied appropriately, provide reliable estimates about the effects of interventions, evaluations, and effects related to the overarching research problem investigated by each study under review.

- Systematic reviews illuminate where knowledge or thorough understanding of a research problem is lacking and, therefore, can then be used to guide future research.

- The accepted inclusion of unpublished studies [i.e., grey literature] ensures the broadest possible way to analyze and interpret research on a topic.

- Results of the synthesis can be generalized and the findings extrapolated into the general population with more validity than most other types of studies .

- Systematic reviews do not create new knowledge per se; they are a method for synthesizing existing studies about a research problem in order to gain new insights and determine gaps in the literature.

- The way researchers have carried out their investigations [e.g., the period of time covered, number of participants, sources of data analyzed, etc.] can make it difficult to effectively synthesize studies.

- The inclusion of unpublished studies can introduce bias into the review because they may not have undergone a rigorous peer-review process prior to publication. Examples may include conference presentations or proceedings, publications from government agencies, white papers, working papers, and internal documents from organizations, and doctoral dissertations and Master's theses.