- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Raymond Carver “On Writing”: Words of Advice for Poets, Short Story Writers, even Novelists

Before diving into my 2023 project of reading a short story a day from the Library of America’s Carver: Collected Stories , I read his brief essay “On Writing” and jotted some bon mots (French for ‘words that seem more important than others’). Of course, no one gives a damn about a writer’s opinions on writing until said writer has “made it.” I’ll give Ray that. Loved his collected poems, so why wouldn’t I respond in kind to what he is most famous for?

Without further ado, here are some Carver-isms for those plying the trade:

“This is one of the things that distinguishes one writer from another. Not talent. There’s plenty of that around. But a writer who has some special way of looking at things and who gives artistic expression to that way of looking: that writer may be around for a time.”

“Isak Dinesen said that she wrote a little every day, without hope and without despair. Someday I’ll put that on a three-by-five card and tape it to the wall beside my desk. I have some three-by-five cards on the wall now. ‘Fundamental accuracy of statement is the ONE sole morality of writing.’ Ezra Pound. It is not everything by ANY means, but if a writer has ‘fundamental accuracy of statement’ going for him, he’s at least on the right track.

“I have a three-by-five up there with this fragment of a sentence from a story by Chekhov: ‘…and suddenly everything became clear to him.’ I find these words filled with wonder and possibility. I love their simple clarity, and the hint of revelation that’s implied. There is mystery, too. What has been unclear before? Why is it just now becoming clear? What’s happened? Most of all—what now? There are consequences as a result of such sudden awakenings. I feel a sharp sense of relief—and anticipation.

“I overheard the writer Geoffrey Wolff say ‘No cheap tricks’ to a group of writing students. That should be on a three-by-five card. I’d amend it a little to ‘No tricks.’ Period. I hate tricks. At the first sign of a trick or a gimmick in a piece of fiction, a cheap trick or even an elaborate trick, I tend to look for cover. Tricks are ultimately boring, and I get bored easily, which may go along with my not having much of an attention span.”

“Too often ‘experimentation’ is a license to be careless, silly, or imitative in the writing. Even worse, a license to try to brutalize or alienate the reader. Too often such writing gives us no news of the world, or else describes a desert landscape and that’s all—a few dunes and lizards here and there, but no people; a place uninhabited by anything recognizably human, a place of interest only to a few scientific specialists.

“It should be noted that real experiment in fiction is original, hard-earned and cause for rejoicing. But someone else’s way of looking at things—Barthelme’s, for instance—should not be chased after by other writers. It won’t work. There is only one Barthelme, and for another writer to try to appropriate Barthelme’s peculiar sensibility or mise en scene under the rubric of innovation is for the writer to mess around with chaos and disaster and, worse, self-deception.”

“It’s possible, in a poem or a short story, to write about commonplace things and objects using commonplace but precise language, and to endow those things—a chair, a window curtain, a fork, a stone, a woman’s earring—with immense, even startling power. It is possible to write a line of seemingly innocuous dialogue and have it send a chill along the reader’s spine—the source of artistic delight, as Nabokov would have it. That’s the kind of writing that most interests me. I hate sloppy or haphazard writing whether it flies under the banner of experimentation or else is just clumsily rendered realism. In Isaac Babel’s wonderful short story, ‘Guy de Maupassant,’ the narrator has this to say about the writing of fiction: ‘No iron can pierce the heart with such force as a period put just at the right place.’ This too ought to go on a three-by-five.”

“If the words are heavy with the writer’s own unbridled emotions, or if they are imprecise and inaccurate for some reason—if the words are in any way blurred—the reader’s eyes will slide right over them and nothing will be achieved. The reader’s own artistic sense will simply not be engaged. Henry James called this sort of hapless writing ‘weak specification.’”

“But if the writing can’t be made as good as it is within us to make it, then why do it? In the end, the satisfaction of having done our best, and the proof of that labor, is the one thing we can take into the grave.”

“I like it when there is some feeling of threat or sense of menace in short stories. I think a little menace is fine to have in a story. For one thing, it’s good for the circulation. There has to be tension, a sense that something is imminent, that certain things are in relentless motion, or else, most often, there simply won’t be a story. What creates tension in a piece of fiction is partly the way the concrete words are linked together to make up the visible action of the story. But it’s also the things that are left out, that are implied, the landscape just under the smooth (but sometimes broken and unsettled) surface of things.

“V.S. Pritchett’s definition of a short story is ‘something glimpsed from the corner of the eye, in passing.’ First the glimpse. Then the glimpse given life, turned into something that illuminates the moment and may, if we’re lucky—that word again—have even further consequences and meaning. The short story writer’s task is to invest the glimpse with all that is in his power. He’ll bring his intelligence and literary skill to bear (his talent), his sense of proportion and sense of the fitness of things: of how things out there really are and how he sees those things—like no one else sees them. And this is done through the use of clear and specific language, language used so as to bring to life the details that will light up the story for the reader. For the details to be concrete and convey meaning, the language must be accurate and precisely given. The words can be so precise they may even sound flat, but they can still carry; if used right, they can hit all the notes.”

A final interesting aside about this essay: Carver quotes Flannery O’Connor on how “she put together a short story whose ending she could not even guess at until she was there.” You often hear this about novelists who hate outlining in advance. They just write and let their characters provide directions as the novel progresses (a strategy called “pantsing” by practitioners of the trade).

Carver found O’Connor’s words liberating. He had considered it his own dark secret—how he’d start stories with a particular line he loved but without any real sense of where the story should go. That’s right. He often had no idea how the line would inform a story and a character’s truth about life. That nugget should reassure some writers out there. The ones who need a license to just go. Just write. Just see where it all leads because usually it leads SOMEwhere.

What, after all, is revision for? Once you get to the story’s Promised Land (read: the ending), you can go at it again, revising, ultimately editing for the precision of those periods and commas. You know. The stuff of Babel. The stuff you’d be proud to put your name to because any story or poem or novel worth writing is worth writing the right way.

You may also like

The Number One Trait of a True Poet?

What is the number one trait of a true poet? Good question, and one which opens with talking points about the abstract […]

J. Crew Poetry Clues

My daughter, once a huge fan of J. Crew clothing, introduced me to the wonderfully-entertaining (if you like words) J. Crew catalogue. […]

10 Good Writing Habits from Lydia Davis

Lydia Davis has a new book out called Essays One, and in those pages is an essay called “Thirty Recommendations for Good […]

The Messy Politics of Line Breaks

You can always tell a poetry expert (notice I didn’t say “snob”). They’re the ones who can go on and on about […]

Alcohol, Emotion, and Tension in Raymond Carver’s Fiction

Sara kornfeld simpson.

Read the instructor’s introduction Read the writer’s comments and bio Download this essay

In “The Art of Evasion,” Leon Edel complains that Ernest Hemingway’s fiction evades emotion by featuring superficial characters who drink: “In Hemingway’s novels people order drinks—they are always ordering drinks—then they drink, then they order some more . . . it is a world of superficial action and almost wholly without reflection” (Edel 170). If Edel fails to recognize the deep emotional tension in Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants,” where one of the characters reflects critically, “that’s all we do isn’t it—look at things and try new drinks” (211), then one can only imagine the qualms he would have with Raymond Carver’s stories. As Charles May notes in “‘Do You See What I’m Saying?’: The Inadequacy of Explanation and the Uses of Story in the Short Fiction of Raymond Carver,” literary “critics often complain that there is no depth in Carver, that his stories are all surface detail” (49). A self-avowed “fan of Ernest Hemingway’s short stories” (“Fires” 19), Carver also saturates his stories with alcohol; his characters often consume inordinate amounts of alcohol and generally struggle with emotional expression. Do Carver’s inebriated and/or alcoholic characters drink to evade emotional connections? Is his fictional world superficial and devoid of tension?

Carver’s critical essays suggest a radically alternative approach to these issues. In “On Writing,” Carver insists that in a short story, “what creates tension . . . is partly the way the concrete words are linked together to make up the visible action of the story. But it’s also the things that are left out, that are implied, the landscape just under the smooth (but sometimes broken and unsettled) surface of things” (17). This suggests that critics who respond solely to the characters’ consumption of alcohol to blunt or evade emotion on the “surface of things” miss much of the emotional tension created or revealed by alcohol underneath the “visible action” of the story. In the same essay, Carver notes, “I like it when there is some feeling of threat or sense of menace in short stories . . . There has to be tension, a sense that something is imminent” (17). This essay will explore the many levels on which alcohol functions to enhance emotional expression and to create tension, a “sense of menace,” in four of Carver’s short stories. Analyzing the relationship between alcohol, emotion, and tension provides a key to the central conflict in these stories, for alcohol consumption is usually parallel and proportional to the rising action, leading to the stories’ most emotionally profound climaxes. Alcohol often acts as a social lubricant, creating emotional bonds among strangers or acquaintances, releasing the characters’ inhibitions and allowing them to reveal their deep fears and tensions in the stories they tell in their drunken state. Paradoxically, however, the characters’ loss of control while under the influence of alcohol can also menace or destroy emotional bonds, relationships, and even bodies and lives. The mysterious, inescapable, paradoxical power of alcohol pervades Raymond Carver’s fiction, shaping and complicating his characters’ identities, relationships, and lives.

In “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” alcohol serves as a social lubricant that diminishes inhibitions, which allows hidden tensions and emotions to emerge. On the surface, this is a story of two couples drinking gin and talking about love by telling stories. As Charles May explains, through their stories the characters “encounter those most basic mysteries of human experience that cannot be explained by rational means” (40), including the intricate connection between love and violence. Mel’s wife, Terri, reveals that “the man she lived with before she lived with Mel loved her so much he tried to kill her” (138). This inner story drives tension within the larger story by uncovering a hidden strain between Terri and Mel. Terri begs, “He did love me though Mel. Grant me that . . . he was willing to die for it” (140). After undergoing such trauma, she must cling to this view in order to cope. But Mel refuses her this, saying “I sure as hell wouldn’t call it love” (142); he too claims ownership of the story because Terri’s first husband had threatened his life several times. As Mel imbibes, he becomes less playful, less eager to reconcile their difference, and the tension mounts. Once intoxicated, Mel’s “concrete words” reflect a complete lack of inhibition, as he tells Terri to “just shut up for once in your life” (146). The tension between them is unmasked as alcohol mediates between their outer and inner lives, revealing the opposing emotions warring “just under the smooth (but sometimes broken and unsettled) surface” of their complex relationship (“On Writing” 17).

As he drinks, Mel becomes more and more loquacious, gradually revealing his deep fears about the impermanence of love—and the permanence of death. At the beginning of the story, when he is sober, Mel insists that “real love is nothing less than spiritual love” (137), but later he asks, “What do any of us really know about love? . . . It seems to me we’re just beginners at love” (144). He now defines love as “physical” and “sentimental,” and no longer uses the word “spiritual;” he begins favoring cupiditas over caritas . Ultimately, the purpose of Mel’s monologue is to come to terms with the fleeting nature of love and life. Freed of all of his inhibitions by alcohol, Mel reveals his true, bleak, frightening perception of love: “if something happened to one of us tomorrow, I think the other one, the other person, would grieve for a while, you know, but then the surviving party would go out and love again, have someone else soon enough. All this, all of this love we’re talking about, it would just be a memory” (145). This concept of ephemeral love differs markedly from the permanence, profoundness, and eternal devotion associated with spiritual love, and is drawn forth from Mel as a result of his drunkenness. Although Mel insists that he is sober, that “I don’t have to be drunk to say what I think. I mean, we’re all just talking, right?” (145), he actually does need alcohol to say what he really thinks. As a result of his drunkenness, we are exposed to a tension within him as he struggles with his idealized and realistic concepts of love, as well as with the terror of impermanence and death.

Mel acknowledges his own confusion about love as he introduces the other story-within-the-story, but has great difficulty conveying the emotional meaning of this story because alcohol progressively blurs his speech and thought processes. Mel, a cardiologist, recounts an old couple’s struggle to survive after a drunk driver runs into their camper. He cannot finish his story because alcohol has robbed him of coherence. His language, the “concrete word,” becomes crude and vulgar as he tries to prove his point about true love: “Even after he found out that his wife was going to pull through, he was still very depressed . . . I’m telling you, the man’s heart was breaking because he couldn’t turn his goddamn head and see his goddamn wife . . . he couldn’t look at the fucking woman” (151). Alcohol has interfered with his thought process so significantly that he cannot articulate the emotional significance of his story; he can only ask, “Do you see what I’m saying?” (151). He cannot explain that this is an example of the more permanent love he yearns for but fears he may never experience. The couple’s deep spiritual love eludes his interpretive powers, and he destroys its purity with his profane language. This may appear to be emotional superficiality, but it is not; Mel is grappling with very deep emotions, both released and muddled by alcohol. The story ends abruptly, almost theatrically, when the gin runs out. Carver provides no resolution to the tension revealed under the influence of alcohol; he leaves the characters in the dark, listening only to their hearts beat.

“Chef’s House” also explores issues of impermanence, but tension arises from alcohol very differently in this story. In “Chef’s House,” not a single drop of alcohol is consumed, yet it is the ever-present menace just under the surface of the characters’ lives. Nowhere is Carver’s desire to create “a sense that something is imminent” (“On Writing,” 17) more powerfully realized. Edna decides to give up everything to move back in with her ex-husband Wes, a recovering alcoholic. They move into a house owned by Chef, Wes’s sponsor, and start spending a blissful summer there together. Edna yearns for permanence, symbolized by her wedding ring: “I found myself wishing the summer wouldn’t end. I knew better, but after a month of being with Wes in Chef’s house, I put my wedding ring back on” (28). Their bliss, threatened by the menace of Wes’s thin grasp on sobriety, is disrupted when Chef informs Wes that they must move out of the house so that his daughter can move in. Carver brings the menace to life; the day Chef comes, “clouds hung over the water” (29). Under this cloud, Wes succumbs to his perceived destiny as an alcoholic: “I’m sorry, I can’t talk like somebody I’m not. I’m not somebody else” (32). When Wes decides to resume drinking, he chooses to end his relationship with Edna and to forget the emotional connection they shared. They must clean out Chef’s house, and then “that will be the end of it” (33). Wes’s sense of inevitability underscores Carver’s conviction that “Menace is there, and it’s a palpable thing” in most people’s lives (“Interview with Raymond Carver” 67). Wes and Edna both feel powerless against the irresistible draw, the mysterious menace, of alcohol.

Alcohol also menaces the characters’ relationships and identities in “Where I’m Calling From.” Set in a drying-out facility, the story is driven forward by the characters’ fear of the lure of alcohol, of a relapse, of the impermanence of sobriety (ominously, the narrator is on his second stay). The menace looms larger when the narrator witnesses a fellow addict’s seizure, as his body adjusts to withdrawal from alcohol. This awakens the narrator’s deep fears of losing control of his body and his life: “But what happened to Tiny is something I won’t ever forget. Old Tiny flat on the floor, kicking his heels. So every time this little flitter starts up anywhere, I draw some breath and wait to find myself on my back, looking up, somebody’s fingers in my mouth” (129). To distract himself from his body’s cravings and his battle for self-control, the narrator drinks coffee and listens to a newcomer’s story: “J.P quits talking. He just clams up. What’s going on? I’m listening. It’s helping me relax, for one thing. It’s taking me away from my own situation” (134). Ironically, in this story, alcohol acts as a social lubricant, but not as a result of intoxication; talking and being social are the only things protecting these men from their need for alcohol. The men stay in control by telling each other about times when they had no control. J.P. remembers he had everything he wanted in life, “but for some reason—who knows why we do what we do?’—his drinking picks up . . . then a time comes, he doesn’t know why, when he makes the switch from beer to gin-and-tonic . . . Things got out of hand. But he kept on drinking. He couldn’t stop” (133-4). Alcohol, which gave him the confidence to ask for his first kiss, destroyed J.P.’s marriage to the love of his life, his happy home and children, and the job of his dreams. Most threatening of all, neither man can understand why he threw it all away. They tell their stories to stave off this tension, to try to attain control over the impermanence of sobriety and the menace that has shaped and ruined their lives.

“Cathedral” presents alcohol not as a destructive force, but as a constructive one, a means to build emotional connections between strangers, a way of liberating the mind and expanding consciousness. Alcohol functions in a positive capacity in this story, releasing tension, liberating the narrator, allowing him to see and connect in a way he is only open to do because he is stoned. The story opens with tension at its peak, with the narrator in his most jealous and closed-minded state. A friend of his wife, a man she has a close emotional connection with, a blind man, is coming to visit. The wife used to read to the blind man, and after she left, she kept in close contact, constantly sending and receiving tapes on which they would tell each other every detail about their lives. The narrator is bothered by their closeness, that “they’d become good friends, my wife and the blind man,” (210), irritated when his wife dismisses his jealousy with the retort, “you don’t have any friends” (212). He is most affected by the fact that “on the last day in office, the blind man asked if he could touch her face. She agreed to this. She told me he touched his fingers to every part of her face, her nose—even her neck! She never forgot it. She tried to write a poem about it [as she did] after something really important happened to her” (210). Her ineradicable memory of this intimate touch awakens her husband’s jealousy and fears of betrayal and abandonment, which intensifies his disgust with blindness: “And his being blind bothered me. My idea of blindness came from the movies. In the movies, the blind moved slowly and never laughed . . . A blind man in my house was not something I looked forward to” (209). The superficiality of his vision is underscored by his lengthy description of the physical appearance of the blind man, which is salient in Carver’s writing because characters are typically minimally described.

As the story progresses, drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana release this tightly strung man’s inhibitions, facilitate male bonding, and finally expand and deepen his narrow, superficial vision. From the start, alcohol is introduced in a positive light, called a “pastime,” and received good-naturedly, even jokingly, by the blind man. Although the narrator begins drinking to drown out his jealousy of the emotional connection between his wife and the blind man, the end result of his intoxication, social lubrication, allows the man to reach an epiphany. Because his wife is smaller, she promptly falls asleep under the influence of the alcohol and drugs they all consume together, and neither man wakes her. When she no longer speaks, the source of tension between the two men is relieved and they are able to begin bonding. As the narrator drinks, he begins to appreciate the company of the blind man, and gradually realizes the emotional emptiness of his own life: “every night I smoked dope and stayed up as long as I could before I fell asleep. My wife and I hardly ever went to bed at the same time” (222). Drinking and bonding with the blind man allow the narrator to confront his own loneliness and emotional evasions, and his mind and life start to open to new possibilities.

Gradually, guided by the blind man’s more expansive vision, the narrator begins thinking beyond the confines of his own narrow reality. As they “watch” a television program about cathedrals together, he suddenly remarks to the blind man, “something has occurred to me. Do you have any idea what a cathedral is?” (223). Although he describes the physical appearance of cathedrals, the narrator cannot capture their spiritual essence and begins to realize the limits of his perfectly healthy vision. Under the liberating influence of alcohol and drugs, he responds positively to the blind man’s suggestion that they draw a cathedral together, and allows himself to experience a physical and emotional connection that would have disgusted his sober self: “His fingers rode my fingers as my hand went over the paper. It was like nothing else in my life up to now” (228). This intimacy of hand touching hand, one man’s fingers riding another’s, recalls and transforms his vision of the blind man’s hand touching his wife’s face. Facing his deepest fear of real intimacy, the narrator inhabits and experiences the other man’s blindness; he closes his eyes, and then does not want to open them again, because he “didn’t feel like [he] was inside anything” (228). He feels completely free, no longer possessed by his jealousy, tension, or fear. The alcohol endows him with a liberating vulnerability he would never have been brave enough to reach were he not intoxicated. Although this story, too, ends with darkness, it is created by the narrator closing his eyes in an act of communion; the darkness signifies not unresolved tension or emotional evasion, but connection and revelation. The narrator has achieved a profound transformation of vision while under the influence of alcohol.

Alcohol possesses a paradoxical power in Raymond Carver’s short stories. The characters use alcohol to blunt their fear of death and the impermanence of life and love. But their consumption of alcohol in many cases brings them closer to death, and can just as quickly ruin love as stimulate it. Alcohol allows them to loosen up, to say and do things they would otherwise never be able to do, to tell their stories, but the intoxication robs them of their coherence. If they are able to finish their stories, it is possible that they won’t remember the profound nature of their intoxicated experiences in a few short hours. Although alcohol acts as a social lubricant that allows the characters to connect with one another through stories, it also creates and surfaces tensions between loved ones and friends, and can even end up breaking connections. Alcohol gives and takes, pushes and pulls, and places the stories in what Carver in his essay “On Writing” calls “relentless motion” (17), driving tension forward as a sometimes intimate, sometimes menacing cosmic force that is nearly impossible for many of the characters to resist, control, or comprehend.

Works Cited

Carver, Raymond. Cathedral . New York: Vintage Contemporaries, 1983. Print.

— “Fires.” Fires: Essays, Poems, Stories . Santa Barbara: Capra, 1983. 19–30. Print.

— “On Writing.” Fires: Essays, Poems, Stories . Santa Barbara: Capra, 1983. 13–18. Print.

— “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” What We Talk About When We Talk About Love: Stories . New York: Vintage Books, 1989. 137–54. Print.

Edel, Leon, and Robert P. Weeks, Ed. “The Art of Evasion.” Hemingway: A Collection of Critical Essays . Eaglewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1963. 169–171. Print.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway: The Finca Edition . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1987. Print.

May, Charles E. “‘Do You See What I’m Saying?’: The Inadequacy of Explanation and the Uses of Story in the Short Fiction of Raymond Carver.” The Yearbook of English Studies (2001): 39–49. Print.

McCaffery, Larry, Sinda Gregory, and Raymond Carver. “An Interview with Raymond Carver.” Mississippi Review (1985): 62–82. Print.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Short Story › Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories

Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on April 16, 2020 • ( 0 )

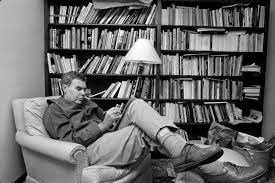

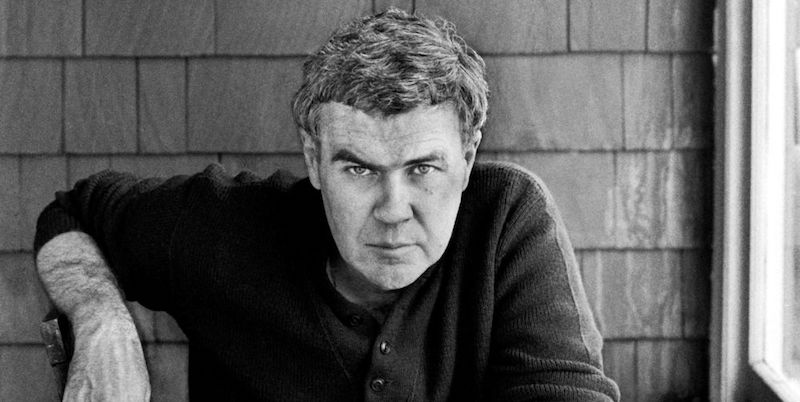

Nearly everything written about Raymond Carver (May 25, 1938 – August 2, 1988) begins with two observations: He is a minimalist, and he writes about working-class people. Even when the critic is sympathetic, this dual categorization tends to stigmatize Carver as a minor artist writing little stories about little people. Although it is true that most of Carver’s characters belong to the working class, their problems are universal. Carver writes about divorce, infidelity, spiritual alienation, alcoholism, bankruptcy, rootlessness, and existential dread; none of these afflictions is peculiar to the working class, and in fact, all were once more common to members of the higher social classes.

Carver was a minimalist by preference and by necessity. His lifelong experience had been with working-class people. It would have been inappropriate to write about simple people in an ornate style, and, furthermore, his limited education would have made it impossible for him to do so effectively. The spare, objective style that he admired in some of Hemingway’s short stories, such as “The Killers” and “Hills Like White Elephants,” was perfectly suited to Carver’s needs.

The advantage and appeal of minimalism in literature is that it draws readers into the story by forcing them to conceptualize missing details. One drawback is that it allows insecure writers to imply that they know more than they know and mean more than they are actually saying. This was true of the early stories that Carver collected in Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? A good example of Carver’s strengths and weaknesses is a short story in that volume titled “Fat.”

As the title suggests, “Fat” is about a fat man. It is little more than a character sketch; nothing happens in the story. Throughout his career, Carver based stories and poems on people or incidents that he observed or scraps of conversation that he overheard; these things seemed to serve as living metaphors or symbols with broader implications. Carver frames his story by setting it in a restaurant and by describing the fat man from the point of view of a waitress. She says that she has never seen such a fat person in her life and is somewhat awestruck by his appearance, by his gracious manners, and by the amount of food that he can consume at one sitting. After she goes home at night, she is still thinking about him. She says that she herself feels “terrifically fat”; she feels depressed, and finally ends by saying, “My life is going to change. I feel it.”

The reader can feel it too but might be hard pressed to say what “it” is. The story leaves a strong impression but an ambiguous one. No two readers would agree on what the story means, if anything. It demonstrates Carver’s talent for characterization through dialogue and action, which was his greatest asset. Both the waitress and her fat customer come alive as people, partially through the deliberate contrast between them. His treatment of the humble, kindly waitress demonstrates his sensitivity to the feelings of women. His former wife, Maryann Carver, said of him, “Ray loved and understood women, and women loved him.”

“Fat” also shows Carver’s unique sense of humor, which was another trait that set him apart from other writers. Carver was so constituted that he could not help seeing the humorous side of the tragic or the grotesque. His early, experimental short stories most closely resemble the early short stories of William Saroyan reprinted in The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze, and Other Stories (1934) and subsequent collections of his stories that appeared in the 1930’s. Saroyan is perhaps best remembered for his novel The Human Comedy (1943), and it might be said that the human comedy was Carver’s theme and thesis throughout his career. Like the early stories of Saroyan, Carver’s stories are the tentative vignettes of a novice who knows very well that he wants to be a writer but still does not know exactly what he wants to say.

Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? includes the tragicomic “Neighbors,” the first of Carver’s stories to appear in a slick magazine with a large circulation. Gordon Lish, editor of the men’s magazine Esquire , recognized Carver’s talent early but did not immediately accept any of his submissions. Lish’s welcome encouragement, painful rejections, and eventual acceptance represented major influences in Carver’s career. “Neighbors” deals with ordinary people but has a surrealistic humor, which was to become a Carver trademark.

Bill and Arlene Miller, a couple in their thirties, have agreed to feed their neighbors’ cat and water the plants while they are away. The Stones’ apartment holds a mysterious fascination, and they both find excuses to enter it more often than necessary. Bill helps himself to the Chivas Regal, eats food out of their refrigerator, and goes through their closets and dresser drawers. He tries on some of Jim Stone’s clothes and lies on their bed masturbating. Then he goes so far as to try on Harriet Stone’s brassiere and panties and then a skirt and blouse. Bill’s wife also disappears into the neighbors’ apartment on her own mysterious errands. They fantasize that they have assumed the identities of their neighbors, whom they regard as happier people leading fuller lives. The shared guilty adventure arouses both Bill and Arlene sexually, and they have better lovemaking than they have experienced in a long while. Then disaster strikes: Arlene discovers that she has inadvertently locked the Stones’ key inside the apartment. The cat may starve; the plants may wither; the Stones may find evidence that they have been rummaging through their possessions. The story ends with the frightened Millers clinging to each other outside their lost garden of Eden.

This early story displays some of Carver’s strengths: his sense of humor, his powers of description, and his ability to characterize people through what they do and say. It also has the two main qualities that editors look for: timeliness and universality. It is therefore easy to understand why Lish bought this piece after rejecting so many others. “Neighbors” portrays the alienated condition of many contemporary Americans of all social classes.

Neighbors, however, has certain characteristics that have allowed hostile critics to damn Carver’s stories as “vignettes,” “anecdotes,” “sketches,” and “slices-of-life.” For one thing, readers realize that the terror they briefly share with the Millers is unnecessary: They can go to the building manager for a passkey or call a locksmith. It is hard to understand how two people who are so bold about violating their neighbors’ apartment should suddenly feel so helpless in the face of an everyday mishap. The point of the story is blunted by the unsatisfactory ending.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

The publication of the collection titled What We Talk About When We Talk About Love made Carver famous. These short, rather ambiguous stories also got him permanently saddled with the term “minimalist.” Carver never accepted that label and claimed that he did not even understand what it meant. He had a healthy mistrust of critics who attempted to categorize writers with such epithets: It was as if he sensed their antagonism and felt that they themselves were trying to “minimize” him as an author. A friend of Carver said that he thought a minimalist was a “taker-out” rather than a “putter-in.” In that sense, Carver was a minimalist. It was his practice to go over and over his stories trying to delete all superfluous words and even superfluous punctuation marks. He said that he knew he was finished with a story when he found himself putting back punctuation marks that he had previously deleted. It would be more accurate to call Carver a perfectionist than a minimalist.

Why Don’t You Dance?

One of the best short stories reprinted in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is “Why Don’t You Dance?” It is one of the most representative, the most “Carveresque” of all Carver’s short stories. A man who is never given a name has placed all of his furniture and personal possessions outside on the front lawn and has whimsically arranged them as if they were still indoors. He has run an extension cord from the house and hooked up lamps, a television, and a record player. He is sitting outside drinking whiskey, totally indifferent to the amazement and curiosity of his neighbors. One feels as if the worst is over for him: He is the survivor of some great catastrophe, like a marooned sailor who has managed to salvage some flotsam and jetsam.

A young couple, referred to throughout the story as “the boy” and “the girl,” drive by and assume that the man is holding a yard sale. They stop and inquire about prices. The man offers them drinks. The boy and girl get into a party spirit. They put old records on the turntable and start dancing in the driveway. The man is eager to get rid of his possessions and accepts whatever they are willing to offer. He even makes them presents of things that they do not really want.Weeks later, the girl is still talking about the man, but she cannot find the words to express what she really feels about the incident. Perhaps she and her young friends will understand the incident much better after they have worked and worried and bickered and moved from one place to another for ten or twenty years.

Why Don’t You Dance? is a humorous treatment of a serious subject, in characteristic Carver fashion. The man’s tragedy is never spelled out, but the reader can piece the story together quite easily from the clues. Evidently there has been a divorce or separation. Evidently there were financial problems, which are so often associated with divorce, and the man has been evicted. Judging from the fact that he is doing so much drinking, alcoholism is either the cause or the effect of his other problems. The man has given up all hope and now sees hope only in other people, represented by this young couple just starting out in life and trying to collect a few pieces of furniture for their rented apartment.

Divorce, infidelity, domestic strife, financial worry, bankruptcy, alcoholism, rootlessness, consumerism as a substitute for intimacy, and disillusionment with the American Dream are common themes throughout Carver’s stories. The symbol of a man sitting outside on his front lawn drinking whiskey, with all of his worldly possessions placed around him but soon to be scattered to the four winds, is a striking symbol of modern human beings. It is easy to acquire possessions but nearly impossible to keep a real home.

Carver did not actually witness such an event but had a similar episode described to him by a friend and eventually used it in this story. A glance at the titles of some of Carver’s stories shows his penchant for finding in his mundane environment external symbols of subjective states: “Fat,” “Gazebo,” “Vitamins,” “Feathers,” “Cathedral,” “Boxes,” “Menudo.” The same tendency is even more striking in the titles of his poems, for example, “The Car,” “Jean’s TV,” “NyQuil,” “My Dad’s Wallet,” “The Phone Booth,” “Heels.”

In his famous essay The Philosophy of Composition , Edgar Allan Poe wrote that he wanted an image that would be “emblematical of Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance,” so he created his famous raven perched on the bust of Pallas Athena and croaking the refrain “nevermore.” To highlight the difference in Carver’s method, Carver might have seen a real raven perched on a real statue, and it would have suggested mournful and never-ending remembrance. This kind of “reverse symbolism” seems characteristic of modern American minimalists in general, and Carver’s influence on their movement is paramount.

Poe states that he originally thought of using a parrot in his famous poem but rejected that notion because it did not seem sufficiently poetic and might have produced a comical effect; if Carver had been faced with such a choice, he probably would have chosen the parrot. What distinguishes Carver from most minimalists is a sense of humor that is impervious to catastrophe: Like the man on the front lawn, Carver had been so far down that everyplace else looked better. He would have concurred heartily with William Shakespeare’s often-quoted lines in As You Like It (pr. c. 1599-1600):

Sweet are the uses of adversity, Which, like a toad, ugly and venomous, Wears yet a precious jewel in his head

On a different level, “Why Don’t You Dance?” reflects Carver’s maturation as a person and an author. The responsibilities of parenthood as well as the experience of teaching young students were bringing home to him the fact that his personal problems could hold instructional utility for others. As a teacher of creative writing, placed more and more in the limelight, interacting with writers, editors, professors, and interviewers, he was being forced to formulate his own artistic credo. The older man in the story sees himself in his young yard-sale customers and wants to help them along in life; this is evidently a reflection of the author’s own attitude. Consequently, the story itself is not merely an autobiographical protest or lament like some of Carver’s earlier works but is designed to deliver a message—perhaps a warning—for the profit of others. The melancholy wisdom of Carver’s protagonist reflects Carver’s own mellowing as he began to appreciate the universally tragic nature of human existence.

Where I’m Calling From

“Where I’m Calling From” is a great American short story. It originally appeared in the prestigious The New Yorker , was reprinted in the collection titled Cathedral, and appears once again as the title story in the best and most comprehensive collection of Carver’s stories, Where I’m Calling From . The story is narrated by an alcoholic staying at a “drying-out facility,” an unpretentious boardinghouse where plain meals are served family style and there is nothing to do but read, watch television, or talk. The bucolic atmosphere is strongly reminiscent of the training- camp scenes in one of Hemingway’s most brilliant short stories, “Fifty Grand.”

The narrator in Carver’s story tells about his drinking problems and interweaves his own biography with that of a friend he has made at the drying-out facility, a man he refers to as J. P. The only thing unusual about their stories is that J. P. is a chimney sweep and is married to a chimney sweep. Both J. P. and the narrator ruined their marriages through their compulsive drinking and are now terrified that they will be unable to control their craving once they get out of the facility. They have made vows of abstinence often enough before and have not kept them. They have dried out before and gone right back to the bottle.

Carver manages to convey all the feelings of guilt, remorse, terror, and helplessness experienced by people who are in the ultimate stages of alcoholism. It is noteworthy that, whereas his alcoholic protagonists of earlier stories were often isolated individuals, the protagonist-narrator of “Where I’m Calling From” not only is actively seeking help but also is surrounded by others with the same problem. This feature indicates that Carver had come to realize that the way to give his stories the point or meaning that they had previously often lacked was to suggest the existence of largescale social problems of which his characters are victims. He had made what author Joan Didion called “the quantum leap” of realizing that his personal problems were actually social problems. The curse of alcoholism affects all social classes; even people who never touch a drop of alcohol can have their lives ruined by it.

“The Bridle” first appeared in The New Yorker and was reprinted in Cathedral. It is an example of Carver’s mature period, a highly artistic story fraught with social significance. The story is told from the point of view of one of Carver’s faux-naïf narrators. Readers immediately feel that they know this good-natured soul, a woman named Marge who manages an apartment building in Arizona and “does hair” as a sideline. She tells about one of the many families who stayed a short while and then moved on as tumbleweeds being blown across the desert. Although Carver typically writes about Northern California and the Pacific Northwest, this part of Arizona is also “Carver Country,” a world of freeways, fast-food restaurants, Laundromats, mindless television entertainment, and transient living accommodations, a homogenized world of strangers with minimum-wage jobs and tabloid mentalities.

Mr. Holits pays the rent in cash every month, suggesting that he recently went bankrupt and has neither a bank account nor credit cards. Carver, like minimalists in general, loves such subtle clues. Mrs. Holits confides to Marge that they had owned a farm in Minnesota. Her husband, who “knows everything there is about horses,” still keeps one of his bridles, evidently symbolizing his hope that he may escape from “Carver Country.” Mrs. Holits proves more adaptable: She gets a job as a waitress, a favorite occupation among Carver characters. Her husband, however, cannot adjust to the service industry jobs, which are all that are available to a man his age with his limited experience. He handles the money, the two boys are his sons by a former marriage, and he has been accustomed to making the decisions, yet he finds that his wife is taking over the family leadership in this brave new postindustrial world.

Like many other Carver male characters, Holits becomes a heavy drinker. He eventually injures himself while trying to show off his strength at the swimming pool. One day the Holitses, with their young sons, pack and drive off down the long, straight highway without a word of explanation. When Marge trudges upstairs to clean the empty apartment, she finds that Holits has left his bridle behind.

The naïve narrator does not understand the significance of the bridle, but the reader feels its poignancy as a symbol. The bridle is one of those useless objects that everyone carts around and is reluctant to part with because it represents a memory, a hope, or a dream. It is an especially appropriate symbol because it is so utterly out of place in one of those two-story, frame-stucco, look-alike apartment buildings that disfigure the landscape and are the dominant features of “Carver Country.” Gigantic economic forces beyond the comprehension of the narrator have driven this farm family from their home and turned them into the modern equivalent of the Joad family in John Steinbeck’s classic novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939).

There is, however, a big difference between Carver and Steinbeck. Steinbeck believed in and prescribed the panacea of socialism; Carver has no prescriptions to offer. He seems to have no faith either in politicians or in preachers. His characters are more likely to go to church to play bingo than to say prayers or sing hymns. Like many of his contemporary minimalists, he seems to have gone beyond alienation, beyond existentialism, beyond despair. God is dead; so what else is new?

Carver’s working-class characters are far more complicated than Steinbeck’s Joad family. Americans have become more sophisticated as a result of the influence of radio, motion pictures, television, the Internet, more abundant educational opportunities, improved automobiles and highways, cheap air transportation, alcohol and drugs, more leisure time, and the fact that their work is less enervating because of the proliferation of labor-saving machinery. Many Americans have also lost their religious faith, their work ethic, their class consciousness, their family loyalty, their integrity, and their dreams. Steinbeck saw it happening and showed how the Joad family was splitting apart after being uprooted from the soil; Carver’s people are the Joad family a half-century down the road. Oddly enough, Carver’s mature stories do not seem nihilistic or despairing because they contain the redeeming qualities of humor, compassion, and honesty.

Where I’m Calling From is the most useful volume of Carver’s short stories because it contains some of the best stories that had been printed in earlier books plus a generous selection of his later and best efforts. One of the new stories reprinted in Where I’m Calling From is “Boxes,” which first appeared in The New Yorker. When Carver’s stories began to be regularly accepted by The New Yorker, it was an indication that he had found the style of self-expression that he had been searching for since the beginning of his career. It was also a sign that his themes were evoking sympathetic chords in the hearts and minds of The New Yorkers’ middle and upper-class readership, the people at whom that magazine’s sophisticated advertisements for diamonds, furs, highrise condominiums, and luxury vacation cruises are aimed.

Boxes is written in Carver’s characteristic tragicomic tone. It is a story in which the faux-naïf narrator, a favorite with Carver, complains about the eccentric behavior of his widowed mother who, for one specious reason or another, is always changing her place of residence. She moves so frequently that she usually seems to have the bulk of her worldly possessions packed in boxes scattered about on the floor. One of her complaints is about the attitude of her landlord, whom she calls “King Larry.” Larry Hadlock is a widower and a relatively affluent property owner. It is evident through Carver’s unerring dialogue that what she is really bitter about is Larry’s indifference to her own fading charms. In the end, she returns to California but telephones to complain about the traffic, the faulty air-conditioning unit in her apartment, and the indifference of management. Her son vaguely understands that what his mother really wants, though she may not realize it herself, is love and a real home and that she can never have these things again in her lifetime no matter where she moves.

What makes the story significant is its universality: It reflects the macrocosm in a microcosm. In “Boxes,” the problem touched on is not only the rootlessness and anonymity of modern life but also the plight of millions of aging people, who are considered by some to be useless in their old age and a burden to their children. It was typical of Carver to find a metaphor for this important social phenomenon in a bunch of cardboard boxes.

Carver uses working-class people as his models, but he is not writing solely about the working class. It is simply the fact that all Americans can see themselves in his little, inarticulate, bewildered characters that makes Carver an important writer in the dominant tradition of American realism, a worthy successor to Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Sherwood Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Willa Cather, John Steinbeck, and William Faulkner, all of whom wrote about humble people. Someday it may be generally appreciated that, despite the odds against him and despite the antipathy of certain mandarins, Raymond Carver managed to become the most important American fiction writer in the second half of the twentieth century.

Other major works Anthology: American Short Story Masterpieces, 1987 (with Tom Jenks). Miscellaneous: Fires: Essays, Poems, Stories, 1983; No Heroics, Please: Uncollected Writings, 1991 (revised and expanded as Call If You Need Me: The Uncollected Fiction and Other Prose, 2001). Poetry: Near Klamath, 1968; Winter Insomnia, 1970; At Night the Salmon Move, 1976; Two Poems, 1982; If It Please You, 1984; This Water, 1985; Where Water Comes Together with Other Water, 1985; Ultramarine, 1986; A New Path to the Waterfall, 1989; All of Us: The Collected Poems, 1996. Screenplay: Dostoevsky, 1985.

Bibliography Bugeja, Michael. “Tarnish and Silver: An Analysis of Carver’s Cathedral.” South Dakota Review 24, no. 3 (1986): 73-87. Campbell, Ewing. Raymond Carver: A Study of the Short Fiction. New York: Twayne, 1992. Carver, Raymond. “A Storyteller’s Shoptalk.” The New York Times Book Review, February 15, 1981, 9. Gentry, Marshall Bruce, and William L. Stull, eds. Conversations with Raymond Carver. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1990. Halpert, Sam. Raymond Carver: An Oral Biography. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1995. ____________, ed. When We Talk About Raymond Carver. Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith, 1991. Kesset, Kirk. The Stories of Raymond Carver. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1995. May, Charles E., ed. Masterplots II: Short Story Series, Revised Edition. 8 vols. Pasadena, Calif.: Salem Press, 2004. Nesset, Kirk. The Stories of Raymond Carver: A Critical Study. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1995. Powell, Jon. “The Stories of Raymond Carver: The Menace of Perpetual Uncertainty.” Studies in Short Fiction 31 (Fall, 1994): 647-656. Runyon, Randolph Paul. Reading Raymond Carver. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1992. Scofield, Martin. “Story and History in Raymond Carver.” Critique 40 (Spring, 1999): 266-280.

Share this:

Categories: Short Story

Tags: American Literature , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Boxes , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Fat , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Neighbors , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s The Bridle , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From , Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Why Don’t You Dance? , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s Boxes , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s Fat , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s Neighbors , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s The Bridle , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From , Criticism of Raymond Carver’s Why Don’t You Dance? , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Notes of Raymond Carver’s Boxes , Notes of Raymond Carver’s Fat , Notes of Raymond Carver’s Neighbors , Notes of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories , Notes of Raymond Carver’s The Bridle , Notes of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love , Notes of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From , Notes of Raymond Carver’s Why Don’t You Dance? , Raymond Carver , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s Boxes , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s Fat , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s Neighbors , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s The Bridle , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From , Study Guides of Raymond Carver’s Why Don’t You Dance? , Summary of Raymond Carver’s Boxes , Summary of Raymond Carver’s Fat , Summary of Raymond Carver’s Neighbors , Summary of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories , Summary of Raymond Carver’s The Bridle , Summary of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love , Summary of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From , Summary of Raymond Carver’s Why Don’t You Dance? , Themes of Raymond Carver’s Boxes , Themes of Raymond Carver’s Fat , Themes of Raymond Carver’s Neighbors , Themes of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories , Themes of Raymond Carver’s The Bridle , Themes of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love , Themes of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From , Themes of Raymond Carver’s Why Don’t You Dance? , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s Boxes , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s Fat , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s Neighbors , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s Short Stories , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s The Bridle , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From , Thesis of Raymond Carver’s Why Don’t You Dance?

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Advertisement

Supported by

Raymond Carver’s Life and Stories

- Share full article

By Stephen King

- Nov. 19, 2009

Raymond Carver, surely the most influential writer of American short stories in the second half of the 20th century, makes an early appearance in Carol Sklenicka’s exhaustive and sometimes exhausting biography as a 3- or 4-year-old on a leash. “Well, of course I had to keep him on a leash,” his mother, Ella Carver, said much later — and seemingly without irony.

Mrs. Carver might have had the right idea. Like the perplexed lower-middle-class juicers who populate his stories, Carver never seemed to know where he was or why he was there. I was constantly reminded of a passage in Peter Straub’s “Ghost Story”: “The man just drove, distracted by this endless soap opera of America’s bottom dogs.”

Born in Oregon in 1938, Carver soon moved with his family to Yakima, Wash. In 1956, the Carvers relocated to Chester, Calif. A year later, Carver and a couple of friends were carousing in Mexico. After that the moves accelerated: Paradise, Calif.; Chico, Calif.; Iowa City, Sacramento, Palo Alto, Tel Aviv, San Jose, Santa Cruz, Cupertino, Humboldt County . . . and that takes us up only to 1977, the year Carver took his last drink.

Through most of those early years of restless travel, he dragged his two children and his long-suffering wife, Maryann, the mostly unsung heroine of Sklenicka’s tale, behind him like tin cans tied to the bumper of a jalopy that no car dealer in his right mind would take in trade. It’s no wonder that his friends nicknamed him Running Dog. Or that when his mother took him into downtown Yakima, she kept him on a leash.

As brilliant and talented as he was, Ray Carver was also the destructive, everything-in-the-pot kind of drinker who hits bottom, then starts burrowing deeper. Longtime A.A.’s know that drunks like Carver are master practitioners of the geographical cure, refusing to recognize that if you put an out-of-control boozer on a plane in California, an out-of-control boozer is going to get off in Chicago. Or Iowa. Or Mexico.

And until mid-1977, Raymond Carver was out of control. While teaching at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he and John Cheever became drinking buddies. “He and I did nothing but drink,” Carver said of the fall semester of 1973. “I don’t think either of us ever took the covers off our typewriters.” Because Cheever had no car, Carver provided transportation on their twice-weekly booze runs. They liked to arrive at the liquor store just as the clerk was unlocking for the day. Cheever noted in his journal that Carver was “a very kind man.” He was also an irresponsible boozehound who habitually ran out on the check in restaurants, even though he must have known it was the waitress who had to pay the bill for such dine-and-dash customers. His wife, after all, often waited tables to support him.

It was Maryann Burk Carver who won the bread in those early years while Ray drank, fished, went to school and began writing the stories that a generation of critics and teachers would miscategorize as “minimalism” or “dirty realism.” Writing talent often runs on its own clean circuit (as the Library of America’s “Raymond Carver: Collected Stories” attests), but writers whose works shine with insight and mystery are often prosaic monsters at home.

Maryann Burk met the love of her life — or her nemesis; Carver appears to have been both — in 1955, while working the counter of a Spudnut Shop in Union Gap, Wash. She was 14. When she and Carver married in 1957, she was two months shy of her 17th birthday and pregnant. Before turning 18, she discovered she was pregnant again. For the next quarter-century she supported Ray as a cocktail waitress, a restaurant hostess, an encyclopedia saleswoman and a teacher. Early in the marriage she packed fruit for two weeks in order to buy him his first typewriter.

She was beautiful; he was hulking, possessive and sometimes violent. In Carver’s view, his own infidelities did not excuse hers. After Maryann indulged in “a tipsy flirtation” at a dinner party in 1975 — by which time Carver’s alcoholism had reached the full-blown stage — he hit her upside the head with a wine bottle, severing an artery near her ear and almost killing her. “He needed ‘an illusion of freedom,’ ” Sklenicka writes, “but could not bear the thought of her with another man.” It is one of the few points in her admirable biography where Sklenicka shows real sympathy for the woman who supported Carver and seems to have never stopped loving him.

Although Sklenicka exhibits something like awe for Carver the writer, and clearly understands the warping influence alcohol had on his life, she is almost nonjudgmental when it comes to Carver the nasty drunk and ungrateful (not to mention sometimes dangerous) husband. She quotes the novelist Diane Smith (“Letters From Yellowstone”) as saying, “That was a bad generation of men,” and pretty much leaves it at that. When she quotes Maryann calling herself a “literary Cinderella, living in exile for the good of Carver’s career,” the first Mrs. Carver comes across as just another whining ex-wife rather than as the stalwart she undoubtedly was. Ray and Maryann were married for 25 years, and it was during those years that Carver wrote the bulk of his work. His time with the poet Tess Gallagher, the only other significant woman in his life, was less than half that.

Nevertheless, it was Gallagher who reaped the personal benefits of Carver’s sobriety (he took his last drink a year before they fell in love) and the financial ones as well. During the divorce proceedings, Maryann’s lawyer said — this both haunts me and to some degree taints my enjoyment of Carver’s stories — that without a decent court settlement, Maryann Burk Carver’s post-divorce life would be “like a bag of doorknobs that wouldn’t open any doors.”

Maryann’s response was, “Ray says he’ll send money every month, and I believe him.” Carver carried through on that promise, although not without a good deal of grousing. But when he died in 1988, the woman who had provided his financial foundation discovered that she had been cut out of sharing the continuing financial rewards of Carver’s popular short-story collections. Carver’s savings alone totaled almost $215,000 at the time of his death; Maryann got about $10,000. Carver’s mother got even less: at age 78, she was living in public housing in Sacramento and eking out a living as a “grandmother aide” in an elementary school. Sklenicka doesn’t call this shabby treatment, but I am happy to do it for her.

It’s as a chronicle of Carver’s growth as a writer that Sklenicka’s book is invaluable, particularly after his career path crossed that of the editor Gordon Lish, the self-styled “Captain Fiction.” Any readers who doubt Lish’s baleful influence on the stories in “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” are apt to think differently after reading Sklenicka’s eye-opening account of this difficult and ultimately poisonous relationship. Those still not convinced can read the corresponding stories in “Beginners,” now available in the sublimely portable and long-overdue “Raymond Carver: Collected Stories.”

In 1972, Lish changed the title of Carver’s second Esquire story — which he edited heavily — from “Are These Actual Miles?” (interesting and mysterious) to “What Is It?” (boring). When Carver, wild to be published in a major slick, decided to accept the changes, Maryann accused him “of being a whore, of selling out to the establishment.” John Gardner had once told Carver that line-editing was not negotiable. Carver may have accepted that — most writers willing to submit to the editing process do — but Lish’s changes were wide and deep. Carver argued that “a major magazine publication was worth the compromise.” Lish, who tried unsuccessfully to edit Leonard Gardner (who would go on to write “Fat City”) with a similarly heavy hand, got his way with Carver. It was a harbinger.

Was Gordon Lish a good editor? Undoubtedly. Curtis Johnson, a textbook editor who introduced Lish to Carver, claims that Lish had “infallible taste in fiction.” But, as Maryann feared, he was — in Ray Carver’s case, at least — much better at discovery than development. And with Carver, he got what he wanted. Perhaps he sensed an essential weakness at Carver’s core (“people-pleasing” is what recovering alcoholics call it). Perhaps it was the strangely elitist view he seems to have held of Carver’s writing, branding the characters “grossly inept” and speaking of “their blatant illiteracies, of which Carver himself was unaware.” This did not stop him from taking credit for Carver’s success; Lish is said to have bragged that Carver was “his creature,” and what appears on the back jacket of “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?”(1976), Carver’s first book of stories, is not Raymond Carver’s photograph but Gordon Lish’s name.

Sklenicka’s account of the changes in Carver’s third book of stories, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” (1981), is meticulous and heartbreaking. There were, she says, three versions: A, B and C. Version A was the manuscript Carver submitted. It was titled “So Much Water So Close to Home.” B was the manuscript Lish initially sent back. He changed the name of the story “Beginners” to “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” and that became the new title of the book. Although Carver was disturbed by this, he nonetheless signed a binding (and unagented) contract in 1980. Soon after, Version C — the version most readers know — arrived on Carver’s desk. The differences between B and C “astounded” him. “He had urged Lish to take a pencil to the stories,” Sklenicka writes. “He had not expected . . . a meat cleaver.” Unsure of himself, Carver was only three years into sobriety after two decades of heavy drinking; his correspondence with Lish over the wholesale changes to his work alternated between groveling (“you are a wonder, a genius”) and outright begging for a return to Version B. It did no good. According to Tess Gallagher, Lish refused by telephone to restore the earlier version, and if Carver understood nothing else, he understood that Lish held the “power of publication access.”

This Hobson’s choice is the beating heart of “Raymond Carver: A Writer’s Life.” Any writer might wonder what he’d do in such a case. Certainly I did; in 1973, when my first novel was accepted for publication, I was in similar straits: young, endlessly drunk, trying to support a wife and two children, writing at night, hoping for a break. The break came, but until reading Sklenicka’s book, I thought it was the $2,500 advance Doubleday paid for “Carrie.” Now I realize it may have been not winding up with Gordon Lish as my editor.

One needs only to scan the stories in “Beginners” and the ones in “What We Talk About” to see the most obvious change: the prose in “Beginners” consists of dense blocks of narration broken up by bursts of dialogue; in “What We Talk About,” there is so much white space that some of the stories (“After the Denim,” for instance) look almost like chapters in a James Patterson novel. In many cases, the man who didn’t allow editors to change his own work gutted Carver’s, and on this subject Sklenicka voices an indignation she is either unwilling or unable to muster on Maryann’s behalf, calling Lish’s editing of Carver “a usurpation.” He imposed his own style on Carver’s stories, and the so-called minimalism with which Carver is credited was actually Lish’s deal. “Gordon . . . came to think that he knew everything,” Curtis Johnson says. “It became pernicious.”

Sklenicka analyzes many of the changes, but the wise reader will turn to the “Collected Stories” and see them for him- or herself. Two of the most dismaying examples are “If It Please You” (“After the Denim” in “What We Talk About”) and “A Small, Good Thing” (“The Bath” in “What We Talk About”).

In “If It Please You,” James and Edith Packer, a getting-on-in-years couple, arrive at the local bingo hall to discover their regular places have been taken by a young hippie couple. Worse, James observes the young man cheating (although he doesn’t win; his girlfriend does). During the course of the evening, Edith whispers to her husband that she’s “spotting.” Later, back at home, she tells him the bleeding is serious, and she’ll have to go to the doctor the following day. In bed, James struggles to pray (a survival skill both James and his creator acquired in daily A.A. meetings), first hesitantly, then “beginning to mutter words aloud and to pray in earnest. . . . He prayed for Edith, that she would be all right.” The prayers don’t bring relief until he adds the hippie couple to his meditations, casting aside his former bitter feelings. The story ends on a note of hard-won hope: “ ‘If it please you,’ he said in the new prayers for all of them, the living and the dead.” In the Lish-edited version, there are no prayers and hence no epiphany — only a worried and resentful husband who wants to tell the irritating hippies what happens “after the denim,” after the games. It’s a total rewrite, and it’s a cheat.

The contrast between “The Bath” (Lish-edited) and “A Small, Good Thing” (Ray Carver unplugged) is even less palatable. On her son’s birthday, Scotty’s mother orders a birthday cake that will never be eaten. The boy is struck by a car on his way home from school and winds up in a coma. In both stories, the baker makes dunning calls to the mother and her husband while their son lies near death in the hospital. Lish’s baker is a sinister figure, symbolic of death’s inevitability. We last hear from him on the phone, still wanting to be paid. In Carver’s version, the couple — who are actually characters instead of shadows — go to see the baker, who apologizes for his unintended cruelty when he understands the situation. He gives the bereaved parents coffee and hot rolls. The three of them take this communion together and talk until morning. “Eating is a small, good thing in a time like this,” the baker says. This version has a satisfying symmetry that the stripped-down Lish version lacks, but it has something more important: it has heart .

“Lish was able . . . to make a snowman out of a snowdrift” is what Sklenicka says about his version of Carver’s stories, but that’s not much of a metaphor. She does better when talking about Lish’s changes to a passage in “They’re Not Your Husband” (in “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?”), pointing out that the Lish version is “meaner, coarser and somewhat diminishing to both characters.” Carver himself says it best. When the narrator of “The Fling” finally faces up to the fact that he has no love or comfort to give his father, he says of himself, “I was all smooth surface with nothing inside except emptiness.” Ultimately, that’s what is wrong with the Ray Carver stories as Lish presented them to the world, and what makes both the Sklenicka biography and the “Collected Stories” such a welcome and necessary corrective.

RAYMOND CARVER

A writer’s life.

By Carol Sklenicka

Illustrated. 578 pp. Scribner. $35

Collected Stories

Edited by William L. Stull and Maureen P. Carroll

1,019 pp. The Library of America. $40

A cover illustration on Nov. 22 carried an incomplete credit. While Ruth Gwily was indeed the illustrator, her portrait of Raymond Carver was based on a photograph by Bob Adelman/Corbis.

How we handle corrections

Stephen King’s latest novel is “Under the Dome.”

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

New Orleans is a thriving hub for festivals, music and Creole cuisine. The novelist Maurice Carlos Ruffin shared books that capture the city’s many cultural influences .

Joseph O’Neill’s fiction incorporates his real-world interests in ways that can surprise even him. His latest novel, “Godwin,” is about an adrift hero searching for a soccer superstar .

Keila Shaheen’s self-published best seller book, “The Shadow Work Journal,” shows how radically book sales and marketing have been changed by TikTok .

John S. Jacobs was a fugitive, an abolitionist — and the brother of the canonical author Harriet Jacobs. Now, his own fierce autobiography has re-emerged .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

News, Notes, Talk

Raymond Carver became a short story writer for a surprisingly practical reason.

When we talk about Raymond Carver, we talk about the short story. Despite having published eight poetry collections before his death (33 years ago to the day), he’s known for works like “Cathedral” and “Why Don’t You Dance.” But, as it turns out, Carver wrote short stories out of practicality, not pure love of the form. In his 1983 Art of Fiction interview in The Paris Review , Carver revealed that his short stories came about through limited time and limited patience:

INTERVIEWER In an article you did for The New York Times Book Review you mentioned a story “too tedious to talk about here”—about why you choose to write short stories over novels. Do you want to go into that story now?

CARVER The story that was “too tedious to talk about” has to do with a number of things that aren’t very pleasant to talk about. I did finally talk about some of these things in the essay “Fires,” which was published in Antaeus . In it I said that finally, a writer is judged by what he writes, and that’s the way it should be. The circumstances surrounding the writing are something else, something extraliterary. Nobody ever asked me to be a writer. But it was tough to stay alive and pay bills and put food on the table and at the same time to think of myself as a writer and to learn to write. After years of working crap jobs and raising kids and trying to write, I realized I needed to write things I could finish and be done with in a hurry. There was no way I could undertake a novel, a two- or three-year stretch of work on a single project. I needed to write something I could get some kind of a payoff from immediately, not next year, or three years from now. Hence, poems and stories.

I was beginning to see that my life was not—let’s say it was not what I wanted it to be. There was always a wagonload of frustration to deal with—wanting to write and not being able to find the time or the place for it. I used to go out and sit in the car and try to write something on a pad on my knee. This was when the kids were in their adolescence. I was in my late twenties or early thirties. We were still in a state of penury, we had one bankruptcy behind us, and years of hard work with nothing to show for it except an old car, a rented house, and new creditors on our backs. It was depressing, and I felt spiritually obliterated. Alcohol became a problem. I more or less gave up, threw in the towel, and took to full-time drinking as a serious pursuit. That’s part of what I was talking about when I was talking about things “too tedious to talk about.”

The rest of the interview is equally illuminating; in it, Carver discusses his path to sobriety, his daily writing habits, and his extensive approach to revision.

But this particular section is a useful reminder that there’s a host of factors that shape a finished piece of writing besides sheer inspiration. Life’s limitations on writers’ creative practices are depressing—or, as Carver puts it, “tedious”—but, in this specific case, short story readers everywhere have benefited.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

to the Lithub Daily

June 6, 2024.

- Cora Currier revisits Elsa Morante’s fiction

- Keanu Reeves and China Miéville’s unlikely comic book collaboration

- Palestinian students and academics in Israel are facing unprecedented penalties for speaking out

Lit hub Radio

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Raymond Carver

Raymond Clevie Carver, Jr. (May 25, 1938– August 2, 1988) was an American short-story writer and poet. Carver contributed to the revitalization of the American short story in literature during the 1980s.

Carver was born in Clatskanie, Oregon, a mill town on the Columbia River, and grew up in Yakima, Washington, the son of Ella Beatrice (née Casey) and Clevie Raymond Carver. His father, a sawmill worker from Arkansas, was a fisherman and heavy drinker. Carver’s mother worked on and off as a waitress and a retail clerk. His one brother, James Franklin Carver, was born in 1943.

Carver was educated at local schools in Yakima, Washington. In his spare time, he read mostly novels by Mickey Spillane or publications such as Sports Afield and Outdoor Life, and hunted and fished with friends and family. After graduating from Yakima High School in 1956, Carver worked with his father at a sawmill in California. In June 1957, at age 19, he married 16-year-old Maryann Burk, who had just graduated from a private Episcopal school for girls. Their daughter, Christine La Rae, was born in December 1957. Their second child, a boy named Vance Lindsay, was born a year later. He supported his family by working as a delivery man, janitor, library assistant, and sawmill laborer. During their marriage, Maryann also supported the family by working as an administrative assistant and a high school English teacher, salesperson, and waitress.

Writing career