- Advanced search

Deposit your research

- Open Access

- About UCL Discovery

- UCL Discovery Plus

- REF and open access

- UCL e-theses guidelines

- Notices and policies

UCL Discovery download statistics are currently being regenerated.

We estimate that this process will complete on or before Mon 06-Jul-2020. Until then, reported statistics will be incomplete.

Improving The Diagnosis And Risk Stratification Of Prostate Cancer

The current diagnostic and stratification pathway for prostate cancer has led to over-diagnosis and over- treatment. This thesis aims to improve the prostate cancer diagnosis pathway by developing a minimally invasive blood test to inform diagnosis alongside mpMRI and to understand the true Gleason 4 burden which will help better stratify disease and guide clinicians in treatment planning. To reduce the number of patients who have to undergo prostate biopsy after indeterminate or false positive prostate mpMRI, we aimed to develop a new panel of mRNA detectable in blood or urine that was able to improve the detection of clinical significant prostate cancer (Gleason 4+3 or ≥6mm) in combination with prostate mpMRI. mRNA expression of 28 potential genes was studied in four prostate cancer cell lines and, using publicly available datasets, a new seven gene biomarker panel was developed using machine learning techniques. The signature was then validated in blood and urine samples from the ProMPT, PROMIS and INNOVATE trials. To redefine the classification of Gleason 4 disease in prostate cancer patients, digital pathology was used to contour and accurately assess the burden and spread of Gleason 4 in a cohort of PROMIS patients compared to the gold standard manual pathology. There was a significant difference between observed and objective Gleason 4 burden that has implications in patient risk stratification and biomarker discovery. The work presented in this thesis makes a significant step toward improving the patient diagnostic and risk classification pathways by ensuring only the right patients are biopsied when necessary, improving the current pathological reference standard.

Archive Staff Only

- Freedom of Information

- Accessibility

- Advanced Search

Development and evaluation of prostate cancer risk prediction models for use in the community

- Mohammad Aladwani

- Division of Population Health, Health Services Research & Primary Care

Student thesis : Phd

File : application/pdf, -1 bytes

Type : Thesis

- Help & FAQ

Identifying potential new stem cell biomarkers for prostate cancer

- Dhafer Alghezi

- Department of Life Sciences

Student thesis : Doctoral Thesis › PhD

- prostate cancer, Biomarkers, Stem cells, IHC, Rnascope

File : application/pdf, 7.98 MB

Type : Thesis

Embargo End Date : 5 Jun 2020

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Immunohistochemistry for Prostate Biopsy—Impact on Histological Prostate Cancer Diagnoses and Clinical Decision Making

Philipp mandel.

1 Department of Urology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Goethe University Frankfurt, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (B.H.); [email protected] (M.N.W.); [email protected] (F.P.); moc.liamelgoog@rihatnizidem (T.I.); [email protected] (C.W.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (L.A.K.); [email protected] (F.K.-H.C.); [email protected] (A.B.)

Mike Wenzel

2 Cancer Prognostics and Health Outcomes Unit, Division of Urology, University of Montreal Health Center, Montreal, QC H2X3A4, Canada; [email protected] (C.W.); [email protected] (P.I.K.)

Benedikt Hoeh

Maria n. welte, felix preisser, clarissa wittler, clara humke, jens köllermann.

3 Dr. Senckenberg Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Frankfurt, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (P.W.)

4 Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies (FIAS), 60590 Frankfurt, Germany

5 Wildlab, University Hospital Frankfurt MVZ GmbH, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany

Christoph Würnschimmel

6 Martini-Klinik Prostate Cancer Center, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, 20251 Hamburg, Germany; ed.eku@iklit (D.T.); ed.eku@nefearg (M.G.)

Derya Tilki

7 Department of Urology, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, 20251 Hamburg, Germany

Markus Graefen

Luis a. kluth, pierre i. karakiewicz, felix k.-h. chun, andreas becker, associated data.

Data will be made available for bona fide research on request.

Background: To test the value of immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining in prostate biopsies for changes in biopsy results and its impact on treatment decision-making. Methods: Between January 2017–June 2020, all patients undergoing prostate biopsies were identified and evaluated regarding additional IHC staining for diagnostic purpose. Final pathologic results after radical prostatectomy (RP) were analyzed regarding the effect of IHC at biopsy. Results: Of 606 biopsies, 350 (58.7%) received additional IHC staining. Of those, prostate cancer (PCa) was found in 208 patients (59.4%); while in 142 patients (40.6%), PCa could be ruled out through IHC. IHC patients harbored significantly more often Gleason 6 in biopsy ( p < 0.01) and less suspicious baseline characteristics than patients without IHC. Of 185 patients with positive IHC and PCa detection, IHC led to a change in biopsy results in 81 (43.8%) patients. Of these patients with changes in biopsy results due to IHC, 42 (51.9%) underwent RP with 59.5% harboring ≥pT3 and/or Gleason 7–10. Conclusions: Patients with IHC stains had less suspicious characteristics than patients without IHC. Moreover, in patients with positive IHC and PCa detection, a change in biopsy results was observed in >40%. Patients with changes in biopsy results partly underwent RP, in which 60% harbored significant PCa.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer diagnosis after prostate biopsies, and the subsequent treatment decision making, affect millions of men worldwide yearly [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. The detailed pathological results of the prostate biopsy mainly influence treatment decision-making in addition to clinical stage and other parameters such as PSA [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Specifically, biopsy Gleason/ISUP grade in addition to numbers of positive cores and percentage of positive biopsy cores provide clinicians with detailed pathological biopsy information for treatment decision-making, to recommend, for example, active surveillance or definite treatments [ 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. However, results of prostate biopsies and final pathologies after treatment with racial prostatectomy can strongly differ and misclassify patients after biopsies, which instead harbored more aggressive disease [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. To predict the final pathology report and avoid underestimation of patients’ biopsy results, several nomograms or epidemiological studies have been published [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. The main goals of the pathological prostate biopsy results are to provide concordance with the final pathological results. Therefore, pathological guidelines recommend immunohistochemistry (IHC) stains to validate/reject prostate cancer diagnosis in suspicious atypical foci [ 14 ]. Moreover, IHC stains are recommended to provide additional information about positive cores and/or percentage of positive cores if this information would affect clinical treatment decision making; for example, inclusion for active surveillance [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Until now, evidence was lacking with regard to the clinical impact and changes in treatment decision-making after additional performance of IHC for prostate biopsies. Moreover, little is known about final pathologies in patients with additional IHC for prostate biopsies and subsequent changes in treatment due to IHC information [ 18 ].

We addressed this void and relied on our prospective institutional prostate biopsy and radical prostatectomy database. We aimed to investigate the effect of IHC in prostate biopsies with regard to clinical treatment decision making and changes in treatment due to positive IHC. We hypothesized that additional IHC performance in prostate biopsies may influence clinicians’ treatment decision making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. study population.

After approval of the local ethics committee, all patients who received prostate biopsies between January 2017 and June 2020 at the Department of Urology at Frankfurt University Hospital were in the prospective institutional prostate biopsy database and identified and evaluated retrospectively. Indications for performing a prostate biopsy were suspicious characteristics such as a digital rectal examination (DRE), suspicious PSA values (defined as suspicious absolute PSA, PSA velocity, PSA density, or PSA age cut-offs for each individual patient), or suspicion of prostate cancer on MRI, defined as PIRADS ≥ 3. This selection criteria yielded 606 prostate biopsy patients. All biopsies were performed by experienced urologists under a transrectal approach under antibiotic prophylaxis and periprostatic local anesthesia, as recommended and described [ 2 , 19 ]. For systematic biopsy, 12-core biopsies (length of 15–22 mm per core) were obtained with six biopsies per prostate lobe. Additional targeted biopsy was performed with a HiVison, Hitachi Medical Systems ultrasound machine, and at least two cores were taken from each mpMRI lesion ≥ PIRADS 3. Patients were firstly stratified according to the usage of IHC in pathological prostate biopsy results. IHC was performed in accordance with pathological guidelines, which recommend IHC stains to validate/reject prostate cancer diagnosis in suspicious atypical foci or to provide additional information about positive cores and/or core percentage of positive cores.

2.2. IHC Stains

After formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, three to four haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were routinely prepared from each prostate biopsy, as well as an additional unstained section for any additional immunohistochemical studies that may be required. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using the automated staining platform DAKO Omnis (Dako/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) on 1–2-µm-thick sections from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded prostate biopsies. The following antibodies were used: p63 (clone DAK-p63, DAKO/Agilent, mouse monoclonal, ready to use), cytokeratin 5/6 (clone D5/16 B4, DAKO/Agilent, mouse monoclonal, ready to use), and high molecular weight cytokeratins (clone 34ßE12, DAKO/Agilent, mouse monoclonal, ready to use) in combination (double staining) with an antibody to Alpha-methyl acyl coenzyme-A racemase (AMACR) (clone 13H4) DAKO/Agilent, rabbit monoclonal, ready to use. The antibodies were configured as FLEX Ready-to-Use (Agilent) and used with the EnVision FLEX visualization system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for use.

2.3. Changes in Biopsy Results and Changes in Clinical Decision Making

Patients with pathologically confirmed prostate cancer after prostate biopsies were subsequently stratified according to the performance of IHC ( Figure 1 ). Furthermore, we classified changes after IHC performance as relevant if a change from initial high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or atypical small acinar proliferation foci to prostate cancer diagnoses, or a change from unilateral to bilateral prostate cancer, occurred. Moreover, we relied on information from the institutional patient files and the prospective institutional radical prostatectomy database to identify subsequent treatment after additional IHC in prostate biopsies and to identify final pathological results if patients underwent radical prostatectomy. Clinically significant prostate cancer was defined as Gleason score ≥ 7 and/or ≥pT3 stage, as previously reported [ 20 , 21 ].

Flow chart depicting the performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses of 606 patients who underwent prostate biopsy at University Hospital Frankfurt between January 2017 and June 2020. Abbreviations: IHC—immunohistochemistry; AS—active surveillance; RT—radiation therapy; RP—radical prostatectomy; ADT—androgen deprivation therapy; WW—watchful waiting.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Means, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR) were reported for continuously coded variables. The Chi-square test was used for statistical significance in proportions’ differences. The t-test and Kruskal-Wallis test examined the statistical significance of means’ and distributions’ differences.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were made to validate the effect of additional IHC in prostate biopsies in real-world clinical application. All tests were two sided with a level of significance set at p < 0.05, and R software environment for statistical computing and graphics (version 3.4.3, Vienna, Austria) was used for all analyses.

3.1. Descriptive Baseline Characteristics: IHC vs. No IHC

Of 606 patients with prostate biopsy, 350 (58.7%) received additional IHC stains ( Table 1 , Figure 1 ). Patients with additional IHC stains at biopsy more frequently harbored non-suspicious DRE (51.1 vs. 42.6%, p < 0.01) and PIRADS3 lesions in MRI (28.9 vs. 23.0%, p = 0.03). No differences between both groups were observed according to median age at biopsy (66 vs. 67 years), median PSA (7.3 [IQR 5.2–11.9] vs. 8.1 [IQR 5.3–15.8] ng/mL), median number of cores taken at biopsy (13 vs. 13), or repeat biopsies (25.5 vs. 21.9%, all p > 0.05). No significant differences were observed in IHC performance in patients with a low PSA <4ng/mL (16.3 vs. 13.3%, p = 0.4). Overall, prostate cancer was found in 208 (59.4%) patients with IHC and in 163 (63.7%) patients without IHC ( p = 0.3).

Descriptive analyses of 606 patients who underwent prostate biopsy at University Hospital stratified according to the performance of immunohistochemistry (IHC). Abbreviations: PSA—prostate-specific antigen; DRE—digital rectal examination; GS—Gleason score.

According to suspicious prostate cancer characteristics, rates of positive IHC were significantly more often observed in patients with suspicious DRE (88.4 vs. 57.5%) and in patients with PSA ≥4 ng/mL (55.5 vs. 40.4%). Conversely, rates of IHC were more frequently negative in patients with PIRADS 3 lesion (23.1 vs. 9.2%, all p ≤ 0.03).

3.2. IHC in Patients with and without Prostate Cancer Detection

Of 208 patients with prostate cancer detection and IHC stains ( Figure 1 ), IHC was histologically positive in 185 (88.9%) patients ( Table S1 ). Moreover, rates of non-suspicious DRE, median number of positive cores, percentage of positive cores at biopsy, and the median of the maximum tumor infiltration per core between IHC vs. non IHC were 55.3 vs. 39.3%, 5 (IQR 2–7) vs. 6 (IQR 4–10), 40% (IQR 20–60) vs. 50% (IQR 30–80), and 50% (IQR 20–80) vs. 70% (50–90%, all p < 0.01), respectively. Moreover, patients with IHC more frequently harbored Gleason 6 (29.8 vs. 4.9%, p < 0.01) than patients without IHC. Additionally, rates of Gleason 7 and 8–10 in biopsy were 38.5 vs. 49.1% and 28.8 vs. 44.8% for IHC vs. no IHC, respectively.

Of 235 patients without prostate cancer detection in biopsy, 142 (60.4%) received additional IHC to rule out prostate cancer ( Figure 1 ). Descriptive characteristics are summarized in Tables S2 and S3 .

3.3. Changes in Prostate Biopsy Results due to IHC Stains

Of 185 patients with histologically positive IHC and prostate cancer detection ( Figure 1 ), IHC led to a change in prostate biopsy results in 81 (43.8%) vs. 104 (56.2%) patients without any changes in biopsy results ( Table 2 ). Patients with changes in biopsy results had significantly lower PSA (7.1 vs. 9.8 ng/mL), lower percentage of positive cores (20 vs. 50%), and lower maximum tumor infiltration per core (20 vs. 60%, all p < 0.01), relative to patients without changes due to positive IHC. Moreover, suspicious DRE and cT2, as well as cT3–4 stages were more frequently in the group without changes in biopsy results. Median number of IHC stains per biopsy did not differ between both groups (4 vs. 4; p = 0.06).

Descriptive analyses of 185 patients with positive prostate biopsy and histological positive immunohistochemistry (IHC) at University Hospital Frankfurt between 01/2017–06/2020, stratified according to changes in biopsy results due to positive IHC results or not. Abbreviations: PSA—prostate-specific antigen; DRE—digital rectal examination; GS: Gleason score.

Of 81 patients with changes in biopsy results due to positive IHC ( Table 3 , Figure 1 ), 55 (67.9%) changed from initial high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or atypical small acinar proliferation foci to prostate cancer diagnoses. Moreover, in 26 (32.1%) patients, the change in biopsy results due to positive IHC led to a bilateral prostate cancer diagnoses instead of a unilateral prostate cancer.

Descriptive analyses of 81 patients with positive prostate biopsy, histological positive immunohistochemistry (IHC), and changes in biopsy results due to positive IHC at University Hospital Frankfurt between 01/2017–06/2020. Abbreviations: PCa—prostate cancer; ASAP—atypical small acinar proliferation; RP—radical prostatectomy; RT—radiotherapy; AS—active surveillance; ADT—androgen deprivation therapy; WW—watchful waiting.

When patient characteristics in patients with changes in biopsy results from precancer lesions to prostate cancer were compared to patients with no IHC performance and negative biopsy, we observed that that patients with negative biopsy and no IHC were younger (63 vs. 69, p < 0.01) and underwent less frequently fusion biopsy (40.9 vs. 67.3%, p < 0.01).

3.4. Treatments of Patients with Changes in Prostate Biopsy due to Positive IHC

Of 81 patients with changes in biopsy results due to positive IHC ( Table 3 , Figure 1 ), 42 (51.9%) underwent subsequent radical prostatectomy, 27 (33.3%) underwent active surveillance, and seven (8.6%) radiation therapy as a curative treatment concept. Conversely, three (3.7%) patients underwent androgen deprivation therapy or watchful waiting as a palliative concept.

Of those patients who underwent subsequently radical prostatectomy, 15 (35.7%) harbored pT2 and Gleason 6 in the final pathology, while 25 (59.5%) patients harbored significant prostate cancer with ≥pT3 and/or Gleason 7–10. Of those 25 patients, 16 (64.0%) initially harbored a unilateral and a change to bilateral prostate cancer due to IHC. Moreover, nine (36.0%) of those patients harbored a high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or atypical small acinar proliferation foci initially and had a change to prostate cancer diagnoses due to IHC.

4. Discussion

We hypothesized that additional IHC in prostate biopsies may influence pathology results and, therefore, also clinicians’ and patients’ treatment decision making. We tested this hypothesis within our institutional biopsy and radical prostatectomy database and made several noteworthy observations.

First, in patients who received IHC at prostate biopsy and those who did not receive IHC, we made important observations regarding patient characteristics. In total, 59% of all prostate biopsies received additional IHC diagnostics for prostate biopsy. Moreover, IHC was mainly used in patients with lower PSA (albeit not statistically significance, probably mainly due to sample size limitations) and unsuspicious DRE, relative to patients without IHC in prostate biopsies. Moreover, in patients with IHC and prostate cancer diagnoses, positive cores per biopsy and tumor infiltration were lower than in patients without IHC and prostate cancer diagnosis in biopsy. These findings are particularly noteworthy, since IHC was mainly used in patients with the most unsuspicious clinical characteristics, and have to be interpreted in the light that the risk of more aggressive disease increases with specific prostate characteristics such as a high PSA level [ 22 , 23 ]. In consequence, patients with lower but still suspicious PSA and unsuspicious DRE are not only difficult to classify in clinical practice for urologists, but also for pathologists regarding a possible prostate cancer diagnosis. Taken together, it seems that IHC provides a safety tool for pathologists to reject or validate prostate cancer diagnoses and affects the majority of patients. This thesis is also emphasized by the fact that IHC was performed in a high proportion of patients (>47%) in order to rule out prostate cancer diagnoses (negative biopsy), which is also very important to reliably reject the cancer diagnosis.

Second, we also made important observations in the comparison between IHC and non-IHC patients with positive prostate biopsies. Here, similar observations as in the overall cohort of all prostate biopsies were made. Specifically, in the IHC group, the PSA was also lower (8.2 (IQR 5.9–12.9) vs. 9.2 (IQR 5.7–29.6)), albeit not reaching significance, probably due to limitations in sample size. Moreover, DRE was more frequently unsuspicious, and numbers of positive biopsy cores and tumor infiltration were lower in the IHC group. Additionally, patients with prostate cancer diagnosis and IHC harbored less aggressive disease than patients without IHC. Specifically, 30% of IHC patients with prostate cancer exhibited Gleason score 6/ISUP grade 1. Conversely, 5% of patients without IHC and prostate cancer exhibited Gleason score 6/ISUP grade 1. These sensitivity analyses in patients with prostate cancer diagnosis emphasize the additional value of IHC in prostate cancer patients with lower tumor burden and less suspicious clinical characteristics, such as lower PSA and lower rates of DRE. Moreover, these observations are in agreement with current literature and may emphasize the assumption that IHC may help to avoid repeat prostate biopsies since smaller prostate cancer foci can be found easier in the first course of biopsies, relative to patients who did not receive IHC in the biopsy and therefore may exhibited negative prostate biopsy results [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Additionally, it is important to emphasize that IHC was performed in >47% of patients to rule out prostate cancer.

Third, we also revealed important findings according to changes in prostate biopsies due to the additional IHC performance. Of all patients with positive IHC and prostate cancer, IHC performance resulted in 44% of cases in a biopsy change. In two thirds of these patients, application of IHC resulted in a change from a high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or atypical small acinar proliferation to prostate cancer diagnoses. In approximately one third, application of IHC changed a unilateral tumor to a bilateral tumor. These findings are particularly relevant, since in atypical small acinar proliferation foci, prostate cancer is found in over 30% in repeat biopsies [ 27 , 28 ]. This underlines the fact that IHC helps to avoid unnecessary repeat biopsy and avoids delayed prostate cancer diagnoses. Additionally, the findings of bilateral prostate cancer diagnosis are noteworthy, since the administration of focal therapies are mostly discussed in single lesion unilateral prostate cancers [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. On the other hand, the IHC results did not change the biopsy results in 56% of patients with positive IHC and prostate cancer. This observation questions the rationale that in selected patients, IHC might be avoided with regard to an economic perspective and cost effectiveness [ 32 ].

Fourth, we also made important observations according to the treatment of patients with changes in biopsy results due to positive IHC. Specifically, the majority of these patients subsequently underwent radical prostatectomy, while one third underwent active surveillance ( n = 27, Figure 1 ). In radical prostatectomy patients, a final pathology of pT2 Gleason 6 was found in 36% ( n = 15), and ≥pT3 and/or Gleason 7–10 in 60% ( n = 25). Significant prostate cancer was mainly found in the cohort of patients with initial unilateral prostate cancer which changed to a bilateral cancer due to IHC. These findings are also in an agreement with current literature. For example, Bokhorst et al. described recently in a reevaluation of prostate biopsies with additional performance of IHC, that IHC had a significant impact on treatment decision-making and changed initial treatment plans of patients from active surveillance to active treatments [ 18 ]. Those observations emphasize that IHC not only contributes to changes in biopsy results, but also in its clinical application for treatment decision making in daily urological practice. Moreover, an undeniable proportion of radical prostatectomy patients in our cohort with changes in biopsy results due to positive IHC harbored unfavorable tumor characteristics. In consequence, IHC may not only help pathologists to validate or reject prostate cancer diagnoses, IHC may also help to identify patients with risk of non-organ confined disease or unfavorable tumor grade characteristics and patients for active surveillance.

Our study has limitations and needs to be interpreted in its retrospective design. Moreover, sample size limitations might impair statistical significance in some of the analyses, especially in PSA analyses. However, the PSA distribution provided an undeniable trend towards higher PSA in non-IHC patients. Secondly, although prostate biopsies were analyzed by experienced uropathologists, interobserver variability cannot completely be ruled out, nor the decision of whether IHC was performed mainly based on the pathologists’ decision. However, all pathologies were confirmed by an independent second pathologist. Furthermore, due to its study design, our findings cannot give answers about the sensitivity or specificity of IHC in prostate biopsies. Prospective studies are needed to further validate or reject our findings. Finally, unfortunately, no long-term follow-up data or further treatments/pathologies are available for patients who underwent active surveillance after changes in biopsy results due to IHC performance.

Taken together, our findings address several clinically important questions. First, majority of patients receive IHC in prostate biopsies. Second, of all patients with IHC, IHC is positive in the majority of patients, but can also be used to rule out prostate cancer. Third, patients with IHC mostly harbor less suspicious clinical and prostate-specific characteristics than patients without IHC. Fourth, in patients with positive IHC, >40% benefit from a change of the biopsy results. Finally, patients with changes in biopsy results mostly underwent subsequent active treatment with radical prostatectomy and significant prostate cancer was found in 60% of patients.

5. Conclusions

Patients with IHC stains mostly harbored less suspicious clinical and prostate-specific characteristics than patients without IHC. Moreover, in patients with positive IHC and PCa detection, a change in biopsy results was observed in >40%. Finally, patients with changes in biopsy results partly underwent active treatment with RP, in which 60% harbored significant PCa.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol28030197/s1 , Table S1: Descriptive analyses of 371 patients with positive prostate biopsy at University Hospital Frankfurt between 01/2017–06/2020, Table S2: Descriptive analyses of 235 patients with negative prostate biopsy at University Hospital Frankfurt between 01/2017–06/2020, Table S3: Descriptive analyses of 290 patients with positive prostate biopsy at University Hospital Frankfurt between 01/2017–06/2020.

Author Contributions

P.M.: Manuscript writing/editing, data collection or management, data analysis; M.W.: Manuscript writing/editing, data collection or management, data analysis; B.H.: Data collection or management; M.N.W.: Data collection or management; F.P.: Data collection or management, data analysis; T.I.: Data analysis, data collection or management; C.W. (Clarissa Wittler): Protocol/project development, data collection or management; C.H.: Data collection or management; J.K.: Data collection or management, data analysis; P.W.: Manuscript writing/editing, data collection or management; C.W. (Christoph Würnschimmel): Protocol/project development; D.T.: Manuscript writing/editing; M.G.: Manuscript writing/editing; L.A.K.: Manuscript writing/editing, protocol/project development; P.I.K.: Manuscript writing/editing; F.K.-H.C.: Manuscript writing/editing; A.B.: Manuscript writing/editing, protocol/project development, data collection or management. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that this study had no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approved by the local ethics committee of the University Hospital Frankfurt, Germany (SUG-7-2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

Peter Wild has an advisory role and speaker‘s bureau (compensated, personally) for the following companies: AstraZeneca, Janssen, Roche, Astellas, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Novartis, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MSD, Qiagen, Molecular Health, and Sophia Genetics.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 07 November 2020

Assessment of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia

- Sakala Gift ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0438-6804 1 ,

- Kasongo Nancy 2 &

- Mwanakasale Victor 1

African Journal of Urology volume 26 , Article number: 70 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

9701 Accesses

6 Citations

Metrics details

Prostate cancer is a leading cause of cancer death in men. Evaluating knowledge, practice and attitudes towards the condition is important to identify key areas where interventions can be instituted.

This was a hospital-based descriptive cross-sectional study aimed at assessing knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia.

A total of 200 men took part in the study (response rate = 100%). Of the 200 respondents, 67 (33.5%) had heard about prostate cancer and 58 (29%) expressed knowledge of prostate cancer out of which 37 (63.8%) had low knowledge. Twenty-six participants (13%) were screened for prostate cancer in the last 2 years. 98.5% of the participants had a positive attitude towards prostate cancer screening. Binary logistic regression results showed that advanced age ( p = 0.017), having secondary or tertiary education ( p = 0.041), increased knowledge ( p = 0.023) and family history of cancer ( p = 0.003) increased prostate cancer screening practice. After multivariate analysis, participants with increased knowledge ( p = 0.001) and family history of cancer ( p = 0.002) were more likely to practice prostate cancer screening.

The study revealed low knowledge of prostate cancer, low prostate cancer screening practice and positive attitude of men towards prostate cancer screening. These findings indicate a need for increased public sensitization campaigns on prostate cancer and its screening tests to improve public understanding about the disease with the aim of early detection.

1 Background

Prostate cancer, or adenocarcinoma of the prostate as it is called in some settings, can be described as cancer of the prostate gland.

The prostate is a small fibromuscular accessory gland of male reproductive system weighing about 20 g. It is located posterior to the pubic symphysis, superior to the perineal membrane, inferior to the bladder and anterior to the rectum. It produces and secretes proteolytic enzymes into semen, to facilitate fertilization [ 1 , 2 ].

Prostate cancer is characterized by both physical and psychological symptoms [ 3 ]. Early-stage prostate cancer is usually asymptomatic [ 4 ]. More advanced disease has similar symptoms with benign prostate conditions such as weak or interrupted urine flow, hesitancy, frequency, nocturia, hematuria or dysuria. Late-stage prostate cancer commonly spreads to bones and cause pain in the hips, spine or ribs [ 4 ]. The 2 commonly used screening methods for prostate cancer are digital rectal examination (DRE) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test.

Prostate cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths among males globally [ 4 ]. The 2018 Global Cancer Project (GLOBOCAN) report estimated 1 276 106 new cases in 2018, representing 7.1% of all cancers worldwide [ 5 ]. The report further estimated the number of deaths due to prostate cancer at 358 989, representing 3.8% of all cancers globally. It was thus ranked the second most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in men. The American Cancer Society 2019 report showed that an estimated 174,650 new cases of prostate cancer would be diagnosed in the USA during 2019 [ 4 ]. The report further stated that an estimated 31,620 deaths from prostate cancer would occur in 2019. It further put the incidence of prostate cancer to about 60% higher in blacks than in whites suggesting a genetic predilection to the cancer.

Africa is no exception to this global trend of high incidence and mortality of prostate cancer with age-standardized incidence and mortality rates of 26.6 and 14.6 per 100 000 men, respectively [ 5 ]. This placed prostate cancer as the third most common cancer among both sexes and the fourth leading cause of all cancer deaths among both sexes in the region. Current statistics on Zambia indicate that Zambia has one of the world’s highest estimated mortality rates from prostate cancer [ 6 , 7 ]. The age standardized incidence and mortality rates from prostate cancer are at 45.6 and 28.4 per 100,000 men, respectively [ 5 ].

Although the causes of prostate cancer are not yet fully understood, it is thought that advanced age (above 50 years), positive family history of prostate cancer and an African-American ethnic background are risk factors [ 4 , 8 ].

In mitigating the effects of diseases like prostate cancer, evaluating knowledge, practice and attitudes towards the condition is important to identify key areas where interventions can be instituted. For instance, studies in other countries that accessed these factors were able to identify the role that health workers and political will could play in increasing knowledge and screening for prostate cancer [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Furthermore, low level of awareness about prostate cancer or the complete lack of it has been identified as the cause of late presentation and poor prognosis [ 11 , 12 ].

Despite Zambia having one of the world’s highest estimated mortality rates from prostate cancer [ 6 , 7 ] coupled with an increased suggested genetic predilection to the cancer [ 4 ], since the majority of the male population are black, no studies assessing knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening have been done. This study therefore sought to address the gap.

The aims of the study were to determine the knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening at Kitwe Teaching Hospital (KTH). In addition, the study also aimed to determine the association between demographics of participants and knowledge, knowledge of participants and attitude towards prostate cancer screening, knowledge of participants and prostate cancer screening practice as well as attitude of participants towards prostate cancer screening and prostate cancer screening practice.

2.2 Study site and design

The study was done at KTH in the Copperbelt province of Zambia. It is a tertiary referral hospital in the region whose catchment area includes Copperbelt, Luapula and North-western provinces. It has a bed capacity of 630 [ 13 ].

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at KTH. The study design was chosen because it is simple to use, cost-effective and time economic.

2.3 Study participants

The sample size was ascertained using the ‘Stalcalc’ function of Epi Info Version 7.1.5. In a month, nearly 419 male patients presented to the target areas for this study at KTH, namely Out-Patient Department (OPD), medical and surgical admission wards. Since data for this study were collected in 1 month, 419 was used as the total population size. A confidence level was 95% and a confidence limit was 5% (at 95% confidence level) and the expected frequency was 50%. Therefore, a sample size of 200 was calculated for this study. Study participants were randomly selected from target areas. All consenting male patients aged 40 years and above in the target areas for this study at KTH were enrolled until the targeted sample size was reached. Male patients aged less than 40 years and participants who did not give consent were excluded from the study.

2.4 Study duration

The study was done in a period of 6 months from April to September 2019.

2.5 Data collection and analysis

The study objectives were explained to participants, and written and informed consent was obtained. Participants were enrolled utilizing a well-structured questionnaire as shown in “Appendix”. The questionnaire collected demographic information including age, marital status, education and occupation. It also collected data on family history of cancer as well as knowledge, practice and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening. Translations to the questionnaire were done from English to a suitable local language according to the participant’s preference. The responses were recorded as given by the participants.

Data collected during the study were checked for completeness and double-entered into the Epi Info version 7 software. Frequency tables and graphs were generated for relevant variables. The data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. For comparing associations between variables, Pearson Chi-square test was performed. A p value of equal or less than 0.05 was considered significant. Binary logistic regression, as well as multivariate analysis, was done. Low knowledge was defined as scoring 1–3 correct responses in the knowledge section, moderate knowledge as scoring 4–6 correct responses and high knowledge as scoring 7–9. Positive attitude was defined as scoring 2 or more correct responses in the section assessing attitudes, while negative was defined as scoring less than 2 correct responses. Practice was assessed with a closed-ended question in the practice section.

A total of 200 participants were enrolled.

3.1 Background characteristics

As illustrated in Table 1 , more than half, 149 (74.5%), of the participants in the study were in the 40–60 years age range. All participants were Christians, 161 (80.5%) had no formal education or had primary education, and 198 (99%) were in informal employment or unemployed.

3.2 Knowledge of prostate cancer

Of the 200 participants enrolled, 67 (33.5%) had heard about prostate cancer, while 133 (66.5%) had never heard about it. Majority, 55.3%, of the participants who had had heard about prostate cancer pointed to a doctor or nurse as a source of information as shown in Table 2 .

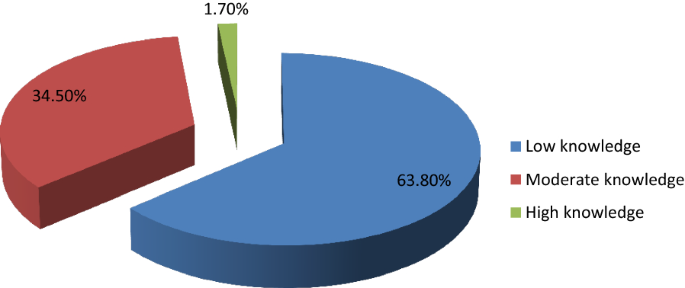

Of the 200 participants enrolled in the study, 58 (29%) expressed knowledge on prostate cancer. Among participants who had knowledge, majority of them, 37 (63.8%) had low knowledge as shown in Fig. 1 .

Levels of knowledge

Participants who had secondary school or tertiary education were more knowledgeable about prostate cancer than those who did not have ( p < 0.001). Participants who had heard about prostate cancer were more knowledgeable than those who had not ( p < 0.001). Participants who had heard about prostate cancer had high levels of knowledge compared to those who had not ( p = 0.009). Participants older than 60 years had more knowledge on prostate cancer compared with those below 60 years ( p = 0.026).

3.3 Practice of prostate cancer screening

Of the 200 participants, only 26 (13%) had been screened in the last 2 years. Among participants who had screened, 20 (76.9%) pointed out DRE as the method used, while 3 (11.5%) pointed out PSA, 2 (7.69%) reported both DRE and PSA, and 1 (3.85%) did not know which screening method was used. Among the 26 participants that had screened in the last 2 years, 18 (69.2%) had a positive prostate cancer outcome, while 8 (30.8%) had a negative prostate cancer outcome. 199 (99.5%) of the participants expressed intentions to screen in future.

Age above 60 years was associated with a positive prostate cancer outcome ( p = 0.002). The study also found that participants who were knowledgeable about prostate cancer were more likely to undergo prostate cancer screening ( p < 0.001) and that high level of knowledge was associated with prostate cancer screening practice ( p = 0.024). Increasing age of participants (over 60) was also associated with prostate cancer screening practice in the last 2 years ( p < 0.001).

3.4 Attitude towards prostate cancer screening

Among 200 participants enrolled in the study, 197 (98.5%) had a positive attitude towards prostate cancer screening, while 3 (1.5%) had a negative attitude. There were no statistically significant associations between age and attitude towards prostate cancer screening ( p = 0.099), knowledge and attitude towards prostate cancer screening ( p = 0.868) as well as between practice in the last 2 years and attitude towards prostate cancer screening ( p = 0.291).

3.5 Factors affecting prostate cancer screening practice

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors that affect prostate cancer screening. As shown in Table 3 , prostate cancer screening practice was associated with age ( p = 0.017), education ( p = 0.041), knowledge ( p = 0.023) and family history of cancer ( p = 0.003).

All factors that were significant in binary logistic analysis (with p < 0.05) were analysed using multivariate logistic regression. A backward step-by-step elimination method was employed to manually eliminate factors with insignificant p values. As illustrated in Table 4 , only two factors remained statistically significant, namely knowledge and family history of cancer. Participants who had knowledge about prostate cancer were nearly 11 times more likely to practice prostate cancer screening than those who did not have ( p = 0.001). Participants who had a family history of cancer were 26 times more likely to practice prostate cancer screening than those who had a negative family history of cancer ( p = 0.002).

4 Discussion

The study targeted male patients aged 40 years and above due to available literature which indicates that prostate cancer screening should start at 40 years [ 4 , 14 ]. Literature indicates that the average age of a man to be diagnosed with prostate cancer is about 66 years and above [ 4 , 15 ]. Since the majority of the participants in the study, 149 (74.5%), were in the 40–60 years age group, as also observed by Mofolo and colleagues in their study [ 16 ], there was an over representation of participants at the lowest risk of prostate cancer.

The study found low levels of awareness and knowledge. This is similar to findings of other studies done in other countries [ 10 , 17 ]. This implies that there is little sensitization being done to the public and expresses the need for more public sensitization campaigns utilizing both electronic and print media with the aim of early detection and treatment to improve the prognosis [ 7 , 8 , 11 ]. However, other studies found high levels of awareness [ 9 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Of the studies that found high levels of knowledge, one of them was done on a group of public servants who were educated, had good access to health information and this was not a reflection of the general population who are mostly uneducated [ 9 ]. The study also demonstrated that majority of the participants who were knowledgeable about prostate cancer had low level of knowledge which was consistent with findings by other studies [ 10 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. This indicates a need for comprehensive knowledge on prostate cancer to promote early detection.

Participants with higher level of education were more knowledgeable about prostate cancer than those who had lower level of education or no formal education at all consistent with findings by similar studies done in other countries [ 16 , 17 , 21 , 24 ]. However, some studies done in Nigeria and Kenya in 2018 did not find such an association [ 10 , 19 ]. In one of the studies that did not find an association between higher education and knowledge, the sample was drawn from a rural part of the country with more than 60% having no formal education or had primary education [ 19 ]. This could have resulted in the finding.

Participants older than 60 years had more knowledge on prostate cancer than those below 60 years as also demonstrated by Adibe et al. [ 24 ]. This highlights a possible bias that might be present in the provision of information on prostate cancer where individuals who are at an advanced age are educated about it because of their increased risk. It could also indicate the natural history of how older patients are more likely to have information about prostate cancer as they visit healthcare centres for urologic problems like benign prostate hyperplasia which are quiet frequent [ 4 , 15 ].

In addition to health workers contributing to the increase in knowledge of prostate cancer, utilizing media platforms that are widely accessible such as radio presents a great opportunity to achieve this. A 2018 study by Kinyao and Kishoyian which assessed attitudes, perceived risk and intention in a rural county found that over 60% of the participants learnt about prostate cancer from the radio [ 19 ]. This shows how much more applicable this media platform can be in developing regions like Africa.

The low level of prostate cancer screening practice demonstrated in the study is consistent with findings from similar studies [ 10 , 11 , 19 , 21 , 25 ] though majority of participants in this study were willing to be screened after discussing about the condition with them consistent with a study done in Kenya [ 21 ]. However, it is inconclusive whether increased knowledge would increase screening as other factors apart from knowledge on prostate cancer appear to influence this practice. A similar study by Kinyao and Kishoyian in 2018 found that many participants had strong fatalistic attitudes towards screening such as “if I am meant to get prostate cancer, I will get it” and these appeared to influence screening [ 19 ]. Thus in sharing information on prostate cancer, cultural beliefs and fatalistic attitudes must also be addressed.

DRE was the most commonly used method of prostate cancer screening contrary to findings by similar studies done in Nigeria that found PSA to be the most commonly used method [ 24 , 25 ]. This suggests a possible cost barrier to utilization of the PSA screening method in our sample.

The finding demonstrated in the study that participants were more likely to screen for prostate cancer if they were older than 60 years is consistent with findings of similar studies done in Uganda and Nigeria [ 11 , 25 ]. This implies that there is a risk of late presentation and consequently poor prognosis. As such, intensified public sensitization campaigns are needed to attain early detection and treatment as well as good prognosis. Participants who were more educated were more likely to undergo prostate cancer screening consistent with findings from a Nigerian study [ 25 ]. The statistically significant association between knowledge on prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening practice is consistent with other similar studies done [ 10 , 11 , 21 ]. This is another indication of the need to intensify prostate cancer sensitization campaigns.

The high positive attitude level demonstrated in the study was similar to findings from other studies done [ 9 , 23 , 24 ]. However, a Ugandan study found a negative attitude towards prostate cancer screening [ 11 ]. This could be because the study explored other factors under attitude that our study did not. The lack of any statistically significant association between age of participants and attitude towards prostate cancer screening concurs with findings from a study done in Uganda [ 11 ]. However, a 2017 study done in Nigeria found an association between age and attitude [ 24 ].

5 Limitations of Study

Generalizability of findings of this study must be done with caution since this was a hospital-based study. There is thus a need for more studies to be done in other institutions such as universities and colleges, urban and rural communities, district, general, central and other teaching hospitals to have comprehensive knowledge. In addition, certain aspects of knowledge were not assessed, for example, that prostate cancer can present without symptoms. As such, the study findings were limited to comparisons with studies that also did not assess the asymptomatic presentation of prostate cancer.

6 Conclusion

The study revealed low knowledge of prostate cancer, low prostate cancer screening practice and positive attitude of men towards prostate cancer screening. Practice of prostate cancer screening was associated with age, education level, knowledge and family history of cancer.

Being the first study to assess knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening in Zambia, it has bridged the knowledge gap and has also provided valuable information for healthcare intervention.

Availability of data and material

Data used in the study is available in additional file 1 captioned ‘Dataset for AFJU-D-19-00041R2 manuscript’ and authors agree to share it.

Abbreviations

- Digital rectal examination

- Prostate-specific antigen

Out-Patient Department

Tropical Diseases Research Centre

National Health Research Authority

Kitwe Teaching Hospital

Global Cancer Project

Blandy J, Kaisary A (2009) Lecture notes urology, 6th edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Google Scholar

Shenoy KR, Shenoy A (2019) Manipal manual of surgery, 4th edn. CBS Publishers Pvt Ltd., Shenoy Nagar

Desousa A, Sonavane S, Mehta J (2012) Psychological aspects of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Dis 15(2):120–127

Article CAS Google Scholar

American Cancer Society (2019) Cancer facts and figures, 2019. American Cancer Society, Atlanta

GloboCan (2018). http://globocan.iarc.fr

GloboCan (2012). http://globocan.iarc.fr

National Cancer Control Strategic Plan 2016–2021. Ministry of Health Zambia

So WK, Choi KC, Tang WP, Lee PC, Shiu AT, Ho SS et al (2014) Uptake of prostate cancer screening and associated factors among Chinese men aged 50 or more: a population-based survey. Cancer Biol Med 11(1):56–63

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Oranusi CK, Mbieri UT, Oranusi IO, Nwofor AME (2012) Prostate cancer awareness and screening among male public servants in Anambra State Nigeria. Afr J Urol 18(2):72–74

Article Google Scholar

Awosan KJ, Yunusa EU, Agwu NP, Taofiq S (2018) Knowledge of prostate cancer and screening practices among men in Sokoto, Nigeria. Asian J Med Sci 9(6):51–56

Nakandi H, Kirabo M, Semugabo C, Kittengo A, Kitayimbwa P, Kalungi S, Maena J (2013) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Ugandan men regarding prostate cancer. Afr J Urol 19(4):165–170

Ito K (2014) Prostate cancer in Asian men. Nat Rev Urol 11:197

Sichula M, Kabelenga E, Mwanakasale V (2018) Factors influencing malnutrition among under five children at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia. Int J Curr Innov in Adv Res 1(7):9–18

Canadian National Institute of Health (2013)

Cancer Diseases Hospital (2013) Annual report

Mofolo N, Betshu O, Kenna O, Koroma S, Lebeko T, Claassen FM, Joubert Gina (2015) Knowledge of prostate cancer among males attending a Urology clinic, a South African study. SpringerPlus 4:67

Kabore FA, Kambou T, Zango B, Ouédraogo A (2014) Knowledge and awareness of prostate cancer among the general public in Burkina Faso. J Cancer Educ 29:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0545-2

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Muhammad FHMS, Soon LK, Azlina Y (2016) Knowledge, awareness and perception towards prostate cancer among male public staffs in Kelantan. Int J of Public Health Clin Sci 3(6):105–115

Kinyao M, Kishoyina G (2018) Attitude, perceived risk and intention to screen for prostate cancer by adult men in Kasikeu sub location, Makueni County, Kenya. Ann Med Health Sci Res 8(3):125–132

Agbugui JO, Obarisiagbon EO, Nwajei CO, Osaigbovo EO, Okolo JC, Akinyele AO (2013) Awareness and knowledge of prostate cancer among men in Benin City, Nigeria. J Med Biomed Res 12(2):42–47

Wanyagah P (2013) Prostate cancer awareness, knowledge, perception on self-vulnerability and uptake of screening among men in Nairobi. Kenyatta University, Kenya

Arafa MA, Rabah DM, Wahdan IH (2012) Awareness of general public towards cancer prostate and screening practice in Arabic communities: a comparative multi-center study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13:4321–4326

Makado E, Makado RK, Rusere MT (2015) An assessment of knowledge of and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening among men aged 40 to 60 years at Chitungwiza Central Hospital in Zimbabwe. Int J Humanit Soc Stud 3(4):45–55

Adibe MO, Oyine DA, Abdulmuminu I, Chibueze A (2017) Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of prostate cancer among male staff of the University of Nigeria. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 18(7):1961–1966

Ebuechi OM, Otumu IU (2011) Prostate screening practices among male staff of the University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Urol 17(4):122–134

Download references

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I express my sincere, heartfelt and profound gratitude to the Almighty God for guiding, protecting and seeing me through the entire process of conducting this study. I am also grateful to my supervisor Prof. Victor Mwanasakale for his zeal and tireless efforts in seeing to it that this work becomes a reality. Let me also express my gratitude to Prof. Seter Siziya and the entire public health team for all the advice, encouragement. I would also like to thank the entire management at the Copperbelt University Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine for a friendly atmosphere. I would also like to thank my family back home for all the support and trust vested in me as well as my friends, roommates and class mates for the moral support.

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the Bachelors degree in medicine and surgery (MBChB).

This work was funded by the Government of the Republic of Zambia through the Ministry of Higher Education through its Higher Education Loans and Scholarships Board. As part of policy, the Ministry of Higher Education through its Higher Education Loans and Scholarships Board finances students in Higher Education institutions whose training demands the carrying out of research. Funding given covers for such expenses incurred during research such as printing and photocopying of data collection tools, transport charges for the researcher during the whole process and ethical clearance charges.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine, The Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 71191, Ndola, Zambia

Sakala Gift & Mwanakasale Victor

Pan - African Organization for Health, Education and Research (POHER), Lusaka, Zambia

Kasongo Nancy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SG is the corresponding author, and KN and MV are the contributing authors. SG constructed the manuscript, collected data, analysed and interpreted data and also edited the manuscript. KN constructed the manuscript, analysed and interpreted data and extensively edited the manuscript. MV constructed the manuscript, extensively edited the manuscript and supervised this thesis study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

The corresponding author (S.G) is currently pursuing his Bachelors degree in Medicine and Surgery (MBChB) at the Copperbelt University Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine in Zambia. K.N is a Pan African Organization for Health, Education and Research (POHER) scholar with a rich research background, who has presented at so many conferences. She was a recipient of the international research elective which took place at University of Missouri School of Medicine, USA, for 2–3 months. She holds a Bachelors Degree of Medicine and Surgery (MBChB) and graduated as the Best student. M.V was also the supervisor of this work. He holds BSc Human Biology, MBChB, MSc and a PhD in Parasitology and is an Associate Professor of Parasitology at the Copperbelt University Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine, Zambia.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sakala Gift .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

A request to conduct the study was sought from the Tropical Diseases Research Centre (TDRC) research ethics committee (IRB Registration Number: 00002911, FWA Number: 00003729) as well as the National Health Research Authority (NHRA). Management at Kitwe Teaching Hospital was assured that confidentiality would not be breached and that the data obtained in the study would not be used for any other purpose besides that specified in the study protocol. Informed and written consent was obtained from participants. During data collection, no identifying images or other personal or clinical details of participants were collected. They were treated with at-most respect and dignity and their rights to privacy and confidentiality were not violated at any point.

Consent for publication

In this study, no data that could compromise the anonymity of participants such as images or other personal or clinical details were collected. As such, it was not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:.

Dataset for AFJU-D-19-00041R2 manuscript.

Appendix: Questionnaire

Topic: assessment of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital.

NAME OF INTERVIEWER:…………………………………………………………

SERIAL NUMBER OF PARTICIPANT:…………………………………………….

DATE:…………………………………………………………………………………

1.1 Section A: demographic characteristics

Instruction: Please, tick as appropriate.

1. Age:…………years

2. Marital status: Single [] Married [] Divorced [] Separated []

3. Religion: Christian [] Muslim [] Traditional []

4. Educational level: Primary [] Secondary [] Tertiary [] No formal education []

5. Occupation: Trader [] Civil servant [] Taxi driver [] Businessman [] Electrician [] Mechanic [] Barber [] Other (please specify)

1.2 Section B: family history of cancer

6. Does anyone in your family have cancer? Yes [] No []

i) What type of cancer………………………………………………………

ii) What is their relation to you………………………………………………

7. Has anyone in your family died of Cancer Yes [] No []

i) What type of cancer……………………………………………………..

ii) What is their relation to you……………………………………………

1.3 Section C: knowledge

8. Have you heard of prostate cancer before: Yes [] No []

i) Where did you hear it from Friends [] Read about it [] TV [] Radio [] Doctor [] Nurse [] Relative []

ii) Which gender does prostate cancer affect Men only [] Women only [] Both men and women [] I do not know []

iii) Which of the following factors could make a person more likely to develop prostate cancer. Please tick as many as possible

a) Family history of the disease [] b) Drinking alcohol [] c) Age [] d)Exercise [] e) Diet [] f) Smoking []

9. Do you know symptoms of prostate cancer Yes [] No []

If Yes, what are they? Tick as many as possible. a) Excessive urination at night [] b)Headache [] c) blood in urine [] d) High temperature [] e) Bone pain [] f) Painful sex [] g) Loss of sex drive [] h) Infertility [] i) cough []

10. Is prostate cancer preventable Yes [] No [] I do not know []

a) How can it be prevented? Genital hygiene [] regular screening [] condom use [] use of right diet [] avoiding many sexual partners []

11. Is prostate cancer curable Yes [] No [] I don’t know []

1.4 Section D: practice

12. Have you been screened for prostate cancer within the last two years? Yes [] No []

a) Which method was used Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) [] Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) [] I do not know []

b) What was the outcome of the screening? Positive [] Negative []

13. Do you have any intention of getting screened in the nearest future? Yes [] No []

1.5 Section E: attitude towards prostate cancer screening

14. Prostate cancer screening is good Yes [] No []

15. Going for prostate cancer screening is a waste of time Yes [] No []

16. Prostate cancer screening has side effects that can cause harmful effects to the body Yes [] No []

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gift, S., Nancy, K. & Victor, M. Assessment of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia. Afr J Urol 26 , 70 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-020-00067-0

Download citation

Received : 01 November 2019

Accepted : 16 September 2020

Published : 07 November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-020-00067-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Prostate cancer screening

DSpace JSPUI

Dspace preserves and enables easy and open access to all types of digital content including text, images, moving images, mpegs and data sets.

- Newcastle University eTheses

- Newcastle University

- Research Institutes

- Northern Institute for Cancer Research

Items in DSpace are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

- Skip to main content

- Accessibility information

- Enlighten Enlighten

Enlighten Theses

- Latest Additions

- Browse by Year

- Browse by Subject

- Browse by College/School

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Funder

- Login (Library staff only)

In this section

Quantitative proteomics and metabolomics of castration resistant prostate cancer

Salji, Mark J. (2018) Quantitative proteomics and metabolomics of castration resistant prostate cancer. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow.

No abstract available.

Actions (login required)

Downloads per month over past year

View more statistics

The University of Glasgow is a registered Scottish charity: Registration Number SC004401

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Abstract. The current diagnostic and stratification pathway for prostate cancer has led to over-diagnosis and over- treatment. This thesis aims to improve the prostate cancer diagnosis pathway by developing a minimally invasive blood test to inform diagnosis alongside mpMRI and to understand the true Gleason 4 burden which will help better stratify disease and guide clinicians in treatment ...

isomiRs in prostate cancer Sharmila Rana November 2020 ... my PhD journey. I was fortunate to be part of two groups, the Keun and Bevan groups, and would like to thank all the ... I dedicate this thesis to you both. 6. Contents Declaration 2 Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 List of Figures 9

Author(s): Zhang, Zhaohuan | Advisor(s): Wu, Holden H. HHW | Abstract: Prostate Cancer (PCa) remains the second most common cause of cancer-related death in men in the U.S. Multi-parametric (mp) MRI is playing an increasingly important role for the localization, detection, and risk stratification of PCa. However, prostate mp-MRI still misses PCa in up to 45% of men and faces challenges in ...

Prostate cancer is the most common male cancer in the UK. Although incidence is increasing, prostate cancer mortality is decreasing, mainly owing to the over diagnosis of disease that would not have become clinically apparent during the patient's lifetime. The gold-standard for prostate cancer diagnosis is transrectal

Student thesis: Phd. Abstract Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men, and the incidence is increasing around the world. Unlike breast cancer in women, there are no effective early detection programs such as screening. This is partly due to lack of an adequate biomarker with ability to detect clinically significant prostate ...

Prostate cancer has emerged as the most frequently diagnosed cancer, except for non-melanoma skin cancer, among men in many Western countries in the last decade. ... Thesis (PhD) Qualification Level: Doctoral: Keywords: Cancer, Prostate, Socio-economic circumstances, Scotland, United Kingdom: Subjects: R Medicine > RC Internal medicine > RC0254 ...

Few biomarkers have been identified for prostate cancer diagnosis/prognosis and there are clinical difficulties in distinguishing between relapsing and non-relapsing tumours. Therefore, identifying new biomarkers for prostate cancer has become a priority. ... It is a difficult task to thank all the people who made this PhD thesis possible with ...

prostate cancer. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/81660/ ... in prostate cancer Dr Chara Ntala MBBS, MSc Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) July 2020 Beatson Institute for Cancer Research Institute of Cancer Sciences

diagnostic pathway of prostate cancer in a small multi-parametric magnetic resonance data regime by Alvaro Fernandez-Quilez Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) Faculty of Health and Medicine Department of Quality and Health Technology 2022

advanced prostate cancer response to therapy Perla Pucci A Thesis submission to the Open University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2019 . DECLARATION ... entire PhD journey. I would like to acknowledge CRUK, the British Columbia Cancer Agency and The ...

The purpose of this dissertation is to examine prostate cancer in Songkhla, Thailand, including a trend analysis of current and future incidence and mortality rates. of prostate cancer, and an analysis to examine differences in prostate tumor. characteristics and cancer survival by religious groups.

UBIRA ETheses - University of Birmingham eData Repository

Prostate Cancer (PCa) remains the second most common cause of cancer-related death in men in the U.S. Multi-parametric (mp) MRI is playing an increasingly important role for the localization, detection, and risk stratification of PCa. ... This thesis aimed to improve prostate MRI by addressing two challenges. First, the diffusion-weighted ...

Prostate cancer has been a disease of older men but age at diagnosis is falling in Sweden. ... The overall purpose of this thesis was to identify and describe fatigue and its influence on men's lives when undergoing examinations for suspected prostate cancer and diagnosed with prostate cancer. Further, the purpose was to understand if ...

ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Quantitative Prostate Diffusion MRI and Multi-Dimensional Diffusion-Relaxation Correlation MRI for Characterization of Prostate Cancer ... Doctor of Philosophy in Bioengineering University of California, Los Angeles, 2023 Professor Holden H. Wu, Chair Prostate Cancer (PCa) remains the second most common cause of ...

Student thesis: Doctoral Thesis › PhD. Abstract Few biomarkers have been identified for prostate cancer diagnosis/prognosis and there are clinical difficulties in distinguishing between relapsing and non-relapsing tumours. Therefore, identifying new biomarkers for prostate cancer has become a priority. Recently, potential stem cells found ...

Prostate cancer diagnosis after prostate biopsies, and the subsequent treatment decision making, affect millions of men worldwide yearly [1, 2, 3]. ... This thesis is also emphasized by the fact that IHC was performed in a high proportion of patients (>47%) in order to rule out prostate cancer diagnoses (negative biopsy), which is also very ...

curative options. Understanding and targeting metastatic prostate cancer remains one of the primary research goals in prostate cancer research. The Sleeping Beauty screen used a forward-mutagenesis transposon-based system to try to identify novel drivers of prostate cancer which cooperated with loss of Pten in vivo.

Julie Emerson Farmer: Systematized Adaptation of Interventions to Increase Prostate Cancer Risk Awareness Among Black Men in North Carolina Under the direction of Erin KentOf all cancer types, prostate cancer is the third most diagnosed cancer in North Carolina.[1] It disproportionately burdens African Americans.[2]

PhD Studentship in "Multi-scale mathematical models to predict prostate cancer progression and treatment response." (2024) PhD studentship in the Groups of "Mathematics Applied to Biology" and "Numerical Analysis and Scientific Computing" at the University of Sussex (UK), with the collaboration of the "Group of Numerical Methods ...

Prostate cancer is a leading cause of cancer death in men. Evaluating knowledge, practice and attitudes towards the condition is important to identify key areas where interventions can be instituted. This was a hospital-based descriptive cross-sectional study aimed at assessing knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above ...

Prostate cancer is usually androgen-dependent and consequently, initial therapy for many patients, particularly with advanced disease, is androgen withdrawal, via anti-androgen therapeutics. Most patients respond to anti-androgen therapy in the early stages of their disease but many will develop resistance, entering a "castrate-resistant ...

Thesis (PhD) Qualification Level: Doctoral: Subjects: Q Science > QH Natural history > QH345 Biochemistry R Medicine > RC Internal medicine: Colleges/Schools: College of Medical Veterinary and Life Sciences > Institute of Cancer Sciences: Supervisor's Name: Leung, Prof. Hing Y. and Zanivan, Dr. Sara R. Date of Award: 2018

Men with prostate cancer could significantly reduce the chances of the disease worsening by eating more fruits, vegetables, nuts and olive oil, according to new research by UC San Francisco. "Greater consumption of plant-based food after a prostate cancer diagnosis has also recently been ...