How to create and manage online assignments for learners

Developing effective assignments for online learning does not have to be daunting. M aster the art of creating and managing online assignments for learners, whether you are with learners using 1:1 devices in a classroom, teaching hybrid or virtually.

One amazing benefit of today’s K-12 education community is the amount of resources, tips and tools available online from educators just like you. Tapping their experience, we’ll show how to create online assignments using digital tools that offer learners at least as much rigor as the ones you may have taught traditionally.

As importantly, you will get tips on successfully managing your students during the learning process. Finally, this blog will give you teaching resources, including alternatives to building online lessons from scratch.

How to plan successful online assignments for learners

An assignment lacking clear structure and substance can spell disaster. Not only will it be harder to manage, but learners may end up frustrated or fail to really learn the material. If not managed well, technology tools can turn into exciting and distracting shiny objects.

To avoid the “edutainment” trap, ensure that onscreen activities support defined learning objectives tied to your district’s standards. Beginning with a strategically planned lesson provides the foundation for whatever digital tools you choose to incorporate.

Know your learners and their current needs

The first step is to clarify what skills or knowledge your learners need to master before moving to the next level. Next, consider different types of assignments online for students to see how they could facilitate this learning.

One brilliant advantage of digital delivery is the ability to tailor assignments to specific learner needs and interests. While selecting which kind of assignment to create, consider what might work best for your learners. Consider specific learners who may need accommodations in content or delivery.

If you don’t already have data to understand the level of knowledge and prior experience learners have in the subject, consider using a Quizlet, survey or other fact-finding tool. Remember the backdrop of what is going on in the students’ surroundings and lives may have a bearing on their learning needs. Consider circumstances that may be affecting learners personally or in their community.

Assess your resources including digital tools

Tap your personal teaching experience before exploring digital resources. Consider how your own understanding and knowledge of the subject can best shine through digital tools.

Having strategies in place can help save time and reduce stress during the process of moving your expertise to an online format. Remember, the extra time put into initial start-up pays off in the long run because digital content can be reused over and over. Lessons in a digital format are shareable, adaptable and updateable.

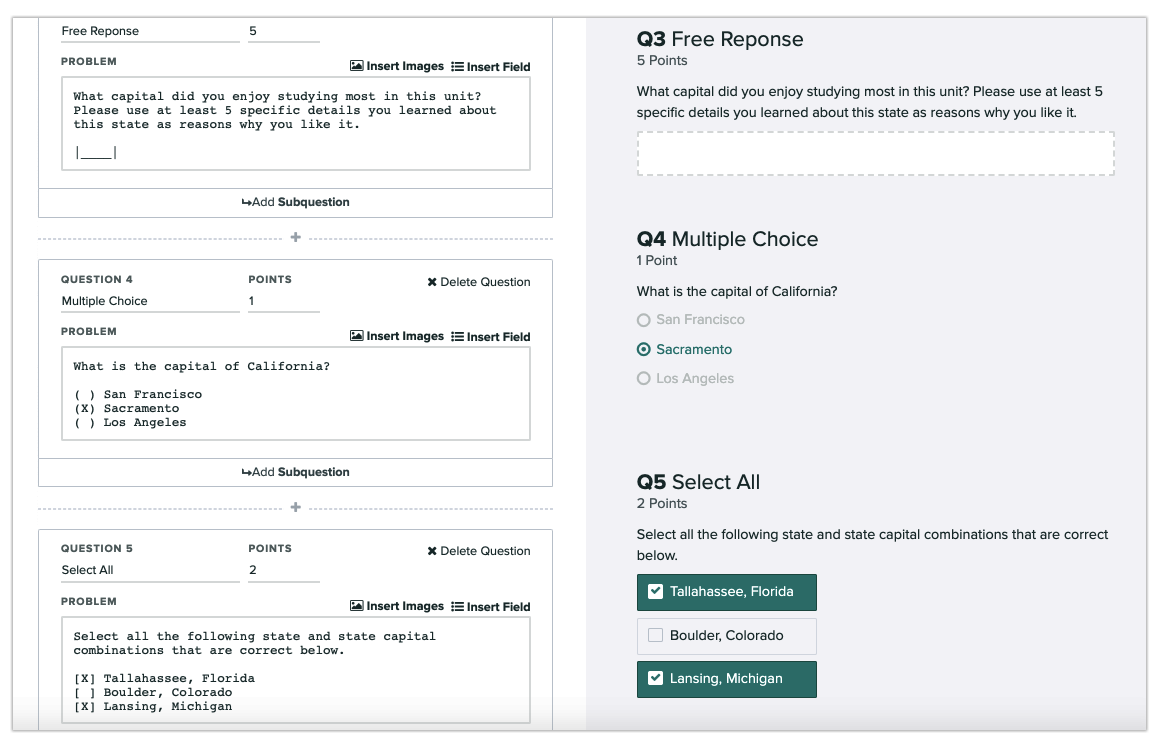

How to make online assignments for learners

Consider variety and higher-level learning as you build assignments that are both engaging and contribute to long-term student goals. Once your academic aims are clear, look for digital tools designed to adapt to your needs as an educator and enhance what you would do in a non-digital format.

Provide clear and concise instruction

Make sure the assignment includes a logical flow from beginning to end. Organize content with headings and bullet points as well as multimedia that breaks up text. Include measurable objectives so learners can clearly understand expectations for the assignment. In some cases, it may be necessary to provide easy-to-understand instruction for each task learners need to complete. Remember you may not be there to fill in the blanks if you leave out an important detail.

Getting started with a few basics can simplify the process of creating dynamic digital content . Recording short videos is an excellent way to simulate actually being there, especially when teaching concepts asynchronously. To record what is on your computer screen, try a screencast program, like Screencastify or Loom for Education . Here you can include your face and help learners better understand you by watching you speak.

Along with video and audio recordings, further support deeper understanding of the subject matter with multimedia elements. These can include graphics, animations, digital graphics, p odcasts, interactive quizzes and simulations like trivia games.

Support learners with orientation and an intuitive system

Even the best instruction and assignments won’t make the learning experience pleasant if students have to spend extra hours figuring out where to find assignments and instructions. Just because students are often tech-savvy does not mean all of them can immediately navigate your school’s LMS unsupported.

Your online assignment at the beginning of the school term could be a simple one that orients learners while providing the opportunity to get hands-on practice using the system. That helps them get used to the workflow and setup. Frustration is easy to mitigate by structuring assignments and using an intuitive learning platform. One example is Hāpara Workspace with an easy-to-view layout that organizes goals, resources, assessments and rubrics into columns.

Promote interaction and collaboration

At the heart of learning is interacting with peers and collaborating. Include activities and projects that support individuals as they practice engaging and working together with other learners. Some learners who feel more comfortable working alone may need extra encouragement and support. This is an opportunity to promote deeper learning and connection by introducing resources that are relevant to students.

Teachers can quickly share resources with groups, or better yet, give learners the opportunity to add their own resources in Hāpara Workspace. Upload everything from videos, links to apps, images and online articles to Google Docs, Slides, Forms and Drawings into Workspace. Group members can access all these resources for shared activities , assessments and collaborative projects.

Managing online assignments

Once you have a well-designed assignment with clear instructions tailored to the needs of different learners, it’s essential to give them guidance. The amount of management you need to provide can vary significantly.

Communicate effectively

Clearly communicate with students throughout the learning process all the way through to assessment. Regular communication helps students stay informed and engaged. You can manage learners as they build toward mastery in an online environment with Hāpara tools.

They provide superior student communication tools, including date reminders for learners and online progress tracking for teachers.

Hāpara Student Dashboard is an online assignment tracker that helps learners develop crucial executive functioning skills. It will help them gain practice organizing their own time, managing and prioritizing their assignments and assessments.

Educators can help learners build upon these skills by providing formative feedback that encourages students to take risks and learn from mistakes. Directly from Hāpara Teacher Dashboard , you can open a learner’s assignment or assessment and provide personalized support. This timely feedback helps learners move toward their academic goals more quickly and confidently.

Monitor learner progress

Monitor how learners are progressing through the assignment. This can inform you whether you need to check in with a learner. Teacher Dashboard shows each learner’s most recent files and when they last modified it. You can also send due date reminders to the class or individual learners through an instant message in Hāpara Highlights .

Provide personalized and differentiated support

With Teacher Dashboard, it’s easy to leave personalized feedback in learners’ recent files and share differentiated resources directly to their screens.

Pull from your own Google Drive or create a new Google Doc, Slide or Drawing on the spot to share with the class, a group or an individual learner.

When a learner can’t find a Google file, teachers can access a learner’s Google Drive with one click in Hāpara. S earch for missing files by title or content and filter to view deleted or unshared files.

Assess and give feedback

Evaluate learners’ understanding and progress with different types of assessment methods, including rubrics, quizzes, peer review and presentations.

Assessments should provide meaningful feedback for learners and educators alike. Use learner feedback to improve on each new assignment you develop. Data on engagement, task completion rates and learner satisfaction will help you make adjustments to improve a future assignment.

Additional resources for online assignment creation

Several alternatives to building your lessons from the ground up are available. These can save time and hassle. To begin with, Google Assignments is a free online assignment solution. To make this even easier, in Hāpara Highlights, as teachers monitor what learners are doing online and offering personalized support, they can quickly share Google Classroom Assignments, Questions and Materials.

Finding free assignments online is another option. With the Discover feature in Hāpara Workspace , you can access online assignments other educators have created from around the world. Search thousands of curriculum-aligned Workspaces by standard, subject, grade level or topic. Then copy and modify them to meet your learners’ needs.

Use AI to plan and teach

Teachers can also use AI to support learning content development and in class with students.

Among the many ways ChatGPT can be used by teachers is helping them create new material, and generate ideas and quizzes. They can quickly personalize the same content in several ways to reach different learners. For example, high school literacy specialist Amanda Kremnitzer told EdWeek that she used ChatGPT to create outlines for her multiple learners who require them as a supplementary aid.

Team up on content creation

Consider shouldering the effort and building content together as a team. Individual members of departments or subject-grade level teams can develop the type of content they are best at and share. Or they can collaborate as a group. As mentioned, you can use the Discover option in Hāpara Workspace to find assignments educators from around the world have created.

If you are looking for a way to create, curate and manage a collection of digital assignments that only your school or district can access, consider Hāpara’s Private Library . With just a click, you can easily distribute your online assignments to educators in your school or district.

Discover why vetting edtech tools for inclusivity matters, learn key questions and criteria, and unlock strategies to leverage edtech for inclusivity.

About the author, sheilamary koch, you might also enjoy, pin it on pinterest.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Creating and Adapting Assignments for Online Courses

Online teaching requires a deliberate shift in how we communicate, deliver information, and offer feedback to our students. How do you effectively design and modify your assignments to accommodate this shift? The ways you introduce students to new assignments, keep them on track, identify and remedy confusion, and provide feedback after an assignment is due must be altered to fit the online setting. Intentional planning can help you ensure assignments are optimally designed for an online course and expectations are clearly communicated to students.

When teaching online, it can be tempting to focus on the differences from in-person instruction in terms of adjustments, or what you need to make up for. However, there are many affordances of online assignments that can deepen learning and student engagement. Students gain new channels of interaction, flexibility in when and where they access assignments, more immediate feedback, and a student-centered experience (Gayten and McEwen, 2007; Ragupathi, 2020; Robles and Braathen, 2002). Meanwhile, ample research has uncovered that online assignments benefit instructors through automatic grading, better measurement of learning, greater student involvement, and the storing and reuse of assignments.

In Practice

While the purpose and planning of online assignments remain the same as their in-person counterparts, certain adjustments can make them more effective. The strategies outlined below will help you design online assignments that support student success while leveraging the benefits of the online environment.

Align assignments to learning outcomes.

All assignments work best when they align with your learning outcomes. Each online assignment should advance students' achievement of one or more of your specific outcomes. You may be familiar with Bloom's Taxonomy, a well-known framework that organizes and classifies learning objectives based on the actions students take to demonstrate their learning. Online assignments have the added advantage of flexing students' digital skills, and Bloom's has been revamped for the digital age to incorporate technology-based tasks into its categories. For example, students might search for definitions online as they learn and remember course materials, tweet their understanding of a concept, mind map an analysis, or create a podcast.

See a complete description of Bloom's Digital Taxonomy for further ideas.

Provide authentic assessments.

Authentic assessments call for relevant, purposeful actions that mimic the real-life tasks students may encounter in their lives and careers beyond the university. They represent a shift away from infrequent high-stakes assessments that tend to evaluate the acquisition of knowledge over application and understanding. Authentic assessments allow students to see the connection between what they're learning and how that learning is used and contextualized outside the virtual walls of the learning management system, thereby increasing their motivation and engagement.

There are many ways to incorporate authenticity into an assignment, but three main strategies are to use authentic audiences, content, and formats . A student might, for example, compose a business plan for an audience of potential investors, create a patient care plan that translates medical jargon into lay language, or propose a safe storage process for a museum collection.

Authentic assessments in online courses can easily incorporate the internet or digital tools as part of an authentic format. Blogs, podcasts, social media posts, and multimedia artifacts such as infographics and videos represent authentic formats that leverage the online context.

Learn more about authentic assessments in Designing Assessments of Student Learning .

Design for inclusivity and accessibility.

Adopting universal design principles at the outset of course creation will ensure your material is accessible to all students. As you plan your assignments, it's important to keep in mind barriers to access in terms of tools, technology, and cost. Consider which tools achieve your learning outcomes with the fewest barriers.

Offering a variety of assignment formats is one way to ensure students can demonstrate learning in a manner that works best for them. You can provide options within an individual assignment, such as allowing students to submit either written text or an audio recording or to choose from several technologies or platforms when completing a project.

Be mindful of how you frame and describe an assignment to ensure it doesn't disregard populations through exclusionary language or use culturally specific references that some students may not understand. Inclusive language for all genders and racial or ethnic backgrounds can foster a sense of belonging that fully invests students in the learning community.

Learn more about Universal Design of Learning and Shaping a Positive Learning Environment .

Design to promote academic integrity online.

Much like incorporating universal design principles at the outset of course creation, you can take a proactive approach to academic integrity online. Design assignments that limit the possibilities for students to use the work of others or receive prohibited outside assistance.

Provide authentic assessments that are more difficult to plagiarize because they incorporate recent events or unique contexts and formats.

Scaffold assignments so that students can work their way up to a final product by submitting smaller portions and receiving feedback along the way.

Lower the stakes by providing more frequent formative assessments in place of high-stakes, high-stress assessments.

In addition to proactively creating assignments that deter cheating, there are several university-supported tools at your disposal to help identify and prevent cheating.

Learn more about these tools in Strategies and Tools for Academic Integrity in Online Environments .

Communicate detailed instructions and clarify expectations.

When teaching in-person, you likely dedicate class time to introducing and explaining an assignment; students can ask questions or linger after class for further clarification. In an online class, especially in asynchronous online classes, you must anticipate where students' questions might arise and account for them in the assignment instructions.

The Carmen course template addresses some of students' common questions when completing an assignment. The template offers places to explain the assignment's purpose, list out steps students should take when completing it, provide helpful resources, and detail academic integrity considerations.

Providing a rubric will clarify for students how you will evaluate their work, as well as make your grading more efficient. Sharing examples of previous student work (both good and bad) can further help students see how everything should come together in their completed products.

Technology Tip

Enter all assignments and due dates in your Carmen course to increase transparency. When assignments are entered in Carmen, they also populate to Calendar, Syllabus, and Grades areas so students can easily track their upcoming work. Carmen also allows you to develop rubrics for every assignment in your course.

Promote interaction and collaboration.

Frequent student-student interaction in any course, but particularly in online courses, is integral to developing a healthy learning community that engages students with course material and contributes to academic achievement. Online education has the inherent benefit of offering multiple channels of interaction through which this can be accomplished.

Carmen Discussions are a versatile platform for students to converse about and analyze course materials, connect socially, review each other's work, and communicate asynchronously during group projects.

Peer review can be enabled in Carmen Assignments and Discussions . Rubrics can be attached to an assignment or a discussion that has peer review enabled, and students can use these rubrics as explicit criteria for their evaluation. Alternatively, peer review can occur within the comments of a discussion board if all students will benefit from seeing each other's responses.

Group projects can be carried out asynchronously through Carmen Discussions or Groups , or synchronously through Carmen's Chat function or CarmenZoom . Students (and instructors) may have apprehensions about group projects, but well-designed group work can help students learn from each other and draw on their peers’ strengths. Be explicit about your expectations for student interaction and offer ample support resources to ensure success on group assignments.

Learn more about Student Interaction Online .

Choose technology wisely.

The internet is a vast and wondrous place, full of technology and tools that do amazing things. These tools can give students greater flexibility in approaching an assignment or deepen their learning through interactive elements. That said, it's important to be selective when integrating external tools into your online course.

Look first to your learning outcomes and, if you are considering an external tool, determine whether the technology will help students achieve these learning outcomes. Unless one of your outcomes is for students to master new technology, the cognitive effort of using an unfamiliar tool may distract from your learning outcomes.

Carmen should ultimately be the foundation of your course where you centralize all materials and assignments. Thoughtfully selected external tools can be useful in certain circumstances.

Explore supported tools

There are many university-supported tools and resources already available to Ohio State users. Before looking to external tools, you should explore the available options to see if you can accomplish your instructional goals with supported systems, including the eLearning toolset , approved CarmenCanvas integrations , and the Microsoft365 suite .

If a tool is not university-supported, keep in mind the security and accessibility implications, the learning curve required to use the tool, and the need for additional support resources. If you choose to use a new tool, provide links to relevant help guides on the assignment page or post a video tutorial. Include explicit instructions on how students can get technical support should they encounter technical difficulties with the tool.

Adjustments to your assignment design can guide students toward academic success while leveraging the benefits of the online environment.

Effective assignments in online courses are:

Aligned to course learning outcomes

Authentic and reflect real-life tasks

Accessible and inclusive for all learners

Designed to encourage academic integrity

Transparent with clearly communicated expectations

Designed to promote student interaction and collaboration

Supported with intentional technology tools

- Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty (e-book)

- Making Your Course Accessible for All Learners (workshop reccording)

- Writing Multiple Choice Questions that Demand Critical Thinking (article)

Learning Opportunities

Conrad, D., & Openo, J. (2018). Assessment strategies for online learning: Engagement and authenticity . AU Press. Retrieved from https://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b8475002~S7

Gaytan, J., & McEwen, B. C. (2007). Effective online instructional and assessment strategies. American Journal of Distance Education , 21 (3), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640701341653

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ragupathi, K. (2020). Designing Effective Online Assessments Resource Guide . National University of Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.nus.edu.sg/cdtl/docs/default-source/professional-development-docs/resources/designing-online-assessments.pdf

Robles, M., & Braathen, S. (2002). Online assessment techniques. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal , 44 (1), 39–49. https://proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eft&AN=507795215&site=eds-live&scope=site

Swan, K., Shen, J., & Hiltz, S. R. (2006). Assessment and collaboration in online learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks , 10 (1), 45.

TILT Higher Ed. (n.d.). TILT Examples and Resources . Retrieved from https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources

Tallent-Runnels, M. K., Thomas, J. A., Lan, W. Y., Cooper, S., Ahern, T. C., Shaw, S. M., & Liu, X. (2006). Teaching Courses Online: A Review of the Research. Review of Educational Research , 76 (1), 93–135. https://www-jstor-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/stable/3700584

Walvoord, B. & Anderson, V.J. (2010). Effective Grading : A Tool for Learning and Assessment in College: Vol. 2nd ed . Jossey-Bass. https://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b8585181~S7

Related Teaching Topics

Designing assessments of student learning, strategies and tools for academic integrity in online environments, student interaction online, universal design for learning: planning with all students in mind, related toolsets, carmencanvas, search for resources.

What is Online Learning? Brief History, Benefits & Limitations

Table of Contents

In the rapidly evolving landscape of education, one term has become increasingly prominent: online learning . As technology continues to prevail in every aspect of our lives, the education industry has been quick to adapt, embracing digital platforms to deliver learning experiences beyond the limitations of traditional classrooms .

But, what exactly is online learning , and how does it reshape the way we acquire knowledge and skills?

In this article, we will answer that and explore online learning in depth looking into its origins, methodologies, benefits, and implications for the future of education .

By examining the benefits and challenges of online learning, we will acquire an understanding of its transformative power and its role in shaping the educational landscape of tomorrow.

Your professional looking Academy in a few clicks

Whether you’re a seasoned educator, a lifelong learner, or simply curious about the evolution of digital education , stay put as we learn more about how we can teach and learn in the digital age.

Definition of Online Learning

Online learning, also referred to as e-learning , digital learning or even sometimes virtual learning, encompasses a broad spectrum of educational activities facilitated through digital technologies.

Online learning is a form of education where instruction and learning take place over the internet and through digital learning tools or platforms like online learning platforms , and learning management systems (LMS) .

Instead of traditional face-to-face interactions in a physical classroom, online learning relies heavily on technology to deliver educational content, facilitate communication between instructors and learners, and assess learner progress.

History of Online Learning: The Roots & Evolution

The roots of online learning are deeply intertwined with the development of computing technology and the Internet. Its evolution can be traced back to the mid-20th century when pioneers began exploring the potential of technology to enhance educational experiences.

To better understand online learning and how it has emerged to become what it is today, let’s briefly travel back in time to go over its key milestones.

Early Experiments in Distance Education

In the 1950s and 1960s, early experiments with computer-based instruction laid the groundwork for what would later become online learning.

Programs such as PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations) introduced interactive learning experiences through computer terminals connected to centralized mainframe computers. These systems enabled students to access course materials , complete assignments, and communicate with instructors remotely.

A few years later, the concept of distance learning – which involves delivering instruction to students who are not physically present in a traditional classroom setting, further propelled this evolution.

Institutions such as the Open University in the United Kingdom and the University of Phoenix in the United States pioneered distance learning models , leveraging postal mail, radio broadcasts, and eventually, early forms of online communication to reach remote learners.

The Internet Revolution

The widespread adoption of the Internet in the 1990s marked a significant turning point in the development of online learning as well. The emergence of the World Wide Web democratized access to information and communication, paving the way for developing web-based learning platforms and creating online courses .

In 1983, the online educational network ‘ Electronic University Network ’ (EUN) became available for use on Commodore 64 and DOS computers, and the first course to be completely held online was launched one year later by the University of Toronto.

Other educational institutions, corporations, and individuals then began exploring the potential of the Internet to deliver educational content and facilitate interactive learning experiences.

Advancements in Learning Management Systems

The late 20th and early 21st centuries witnessed the rise of learning management systems , which provided centralized platforms for delivering, managing, and tracking online learning activities.

Platforms such as Moodle (Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment) which was the first open-source LMS, revolutionized the way educational content was delivered and facilitated collaboration between instructors and learners in virtual environments.

Learners were using a downloadable desktop application and from there they would choose which content they wanted to export on their computers.

The rise of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)

In the 2010s, the advent of Massive Open Online Courses ( MOOCs ) further transformed the landscape of online learning.

MOOC platforms started offering free or low-cost access to courses from leading universities and institutions around the world, reaching millions of learners globally. MOOCs popularized the concept of open and accessible online education , sparking discussions about the future of traditional higher education and lifelong learning.

Continued Innovation and Expansion

Online learning continues to evolve rapidly today, driven by advancements in technology, pedagogy, and learning science.

Since the millennium, the elearning industry has grown by 900% , and by the end of 2025 is expected to triple. The global elearning market will reach $336.98 in 2026 and by 2032, the total value projection is estimated to hit a trillion .

Already data shows that around 90% of organizations offer digital learning to train employees , confirming its crucial role in corporate training environments as well.

💁🏼 Find out How to Build a Great Online Corporate Training Program

There is no doubt that innovations such as adaptive learning, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence are reshaping the online learning environment, providing learners with more personalized, immersive, and engaging educational experiences with real impact on their personal and professional lives.

Types of Online Learning

From interactive multimedia-rich modules to live-streamed lectures, online learning today offers a diverse array of tools and resources tailored to meet the needs of learners across several disciplines and levels of expertise.

It encompasses various forms of educational content and activities delivered online, such as online courses , lectures, video tutorials, quizzes, presentations, online classes , live webinars , and more.

Online learning can be categorized into various types , including synchronous and asynchronous learning, as well as blended learning.

Synchronous Learning:

This involves real-time interaction between instructors and students, often through video conferencing tools (like Zoom or Skype), chat rooms, or virtual classrooms.

Synchronous learning mimics the structure of traditional classroom instruction, with scheduled lectures, discussions, and other activities.

Asynchronous Learning:

In asynchronous mode, learners access course materials and complete assignments at their own pace. While there may be deadlines for assignments and exams, online students have flexibility in terms of when and where they engage with the content.

Asynchronous learning typically involves pre recorded lectures, discussion forums, online quizzes, and other interactive elements.

Blended Learning:

Also known as hybrid learning, this approach combines online instruction with face-to-face interactions . Learners may attend some classes in person while completing others online.

Blended learning offers the benefits of both traditional and online education, providing flexibility while still allowing for direct engagement with instructors and peers.

Key Benefits of Online Learning

Online learning offers several advantages , including accessibility for learners with geographical or scheduling constraints and flexibility in pacing and scheduling.

It can support a variety of educational resources, accommodate diverse learning styles , and offer opportunities for personalized learning.

Here are some of the key benefits of online learning:

- It offers flexibility to learners to access course materials at their own pace.

- It provides accessibility to education for learners from various locations and those unable to attend the classroom physically.

- It is more cost-effective than traditional classroom instruction, as it reduces expenses associated with physical infrastructure, commuting, and materials.

- It allows for greater personalization tailoring learning experiences to individual learners’ preferences, abilities, and learning styles.

- It supports a variety of resources including text-based materials, videos, audio recordings, interactive modules, e-books, live-streamed lectures, and more.

- It has a global reach connecting learners with instructors and peers from around the world, fostering cross-cultural exchange, collaboration, and exposure to diverse perspectives and experiences.

Understanding these benefits and multiple facets of online learning is crucial, so let’s take a closer look at each.

Flexibility and accessibility for learners

Online learning offers unparalleled flexibility for learners, allowing them to access educational resources and participate in self-paced learning programs fitting their daily schedules.

Unlike traditional brick-and-mortar classrooms with fixed schedules, online learning caters to the diverse needs of students , whether they are full-time working professionals seeking to enhance their skills or individuals with busy lifestyles balancing multiple commitments.

Additionally, online learning breaks down geographical barriers , enabling individuals from remote or underserved areas to access high-quality education that may not have been feasible otherwise. By providing 24/7 access to the learning material, online platforms empower learners to take control of their education and pursue their academic or professional goals on their own terms.

Cost-effectiveness and scalability

One of the most significant advantages of online learning is its cost-effectiveness and scalability . By leveraging digital technologies and eliminating the need for physical infrastructure, such as classrooms and textbooks, online courses can be delivered at a fraction of the cost of traditional education.

This affordability makes education more accessible to a wider audience , including individuals with limited financial resources or those unable to afford traditional tuition fees.

Moreover, online learning platforms have the potential for rapid scalability, allowing institutions to accommodate a larger number of students without the constraints of physical space or instructor availability. This scalability is particularly advantageous for organizations looking to expand their educational offerings or reach new markets without significant investments in infrastructure.

Customization and adaptability to diverse learning styles

Online learning platforms offer a wealth of tools and resources to cater to diverse learning styles and preferences. From interactive multimedia content to adaptive learning algorithms, these platforms can personalize the learning experience to suit the individual needs and preferences of each student.

Learners can choose the format and pace of their studies, engage with interactive exercises, and simulations, complete coursework, and receive instant feedback to track their progress and identify areas for improvement. Additionally, online courses often incorporate various multimedia elements, such as videos, animations, and gamified activities, to enhance engagement and retention.

Some platforms with advanced features like LearnWorlds , even go the extra mile offering instructors the ability to communicate with their learners as well as learners communicating with their peers, via online discussion boards, in private or public groups, and as part of a wider online learning community .

Give LearnWorlds a spin and explore its awesome capabilities. Get your free trial today!

Global reach and democratization of education

Online learning transcends geographical boundaries, enabling access to education for individuals around the world . Regardless of location or time zone, learners can connect with instructors and peers, fostering a global learning community.

This global reach not only enriches the educational experience by facilitating cross-cultural exchange and collaboration but also promotes inclusivity and diversity within the learning environment.

Moreover, online courses often offer language localization options, making educational content accessible to non-native speakers and individuals with different language preferences.

By offering this level of access to education, online learning empowers individuals from all walks of life to pursue their academic and professional aspirations , regardless of socio-economic status or geographic location.

Challenges of Online Learning

Despite its advantages though, online learning also presents challenges such as the need for reliable internet access and proper computer equipment.

It also requires the self-discipline of learners to stay motivated and focused and comes with potential limitations that may hinder social interaction as well as hands-on learning experiences.

Some of the key challenges of online learning include:

- It often lacks face-to-face interaction found in traditional classrooms, which can lead to feelings of isolation and reduced opportunities for socialization.

- It can present technical difficulties such as internet connectivity issues, software glitches, or hardware malfunctions, disrupting the learning experience and causing frustration.

- It requires greater self-motivation to stay on track with coursework, manage time effectively, and resist distractions, which can be challenging.

- It offers limited hands-on learning for certain subjects or skills that are difficult to teach and learn effectively in an online format; those requiring hands-on practice, laboratory work, or physical manipulation of materials.

- It can be prone to distractions such as social media, email, or household chores, making it difficult for learners to maintain focus and concentration.

- It raises quality and credibility concerns related to educational content and credentials, requiring learners to carefully evaluate the reputation and accreditation of online programs.

Now, let’s examine these downsides in greater detail as well.

Social isolation and lack of face-to-face interaction

Without the physical presence of classmates and instructors, online learners may miss out on spontaneous discussions , group activities, and non-verbal cues that facilitate communication and relationship-building in traditional classrooms. This lack of social interaction can impact engagement and satisfaction with the learning experience.

Technical difficulties and hands-on learning

Online learners may encounter challenges accessing course materials, participating in virtual sessions, or submitting assignments due to technical glitches or outages. These disruptions can undermine the reliability and effectiveness of online learning platforms, requiring robust technical support and contingency plans to minimize their impact on the learning process.

When such problems occur, offering hands-on learning experiences becomes even more difficult. Laboratory experiments, fieldwork, or technical training may be impractical or insufficiently replicated in online environments, limiting opportunities for tactile exploration , observation, and skill development.

Combining online learning with on-site learning though, will allow learners to pursue disciplines that require practical application and experiential learning opportunities.

Self-motivation and potential distractions

Without the structure and supervision provided in traditional classrooms, online learners must possess strong self-discipline , time management skills, and intrinsic motivation to stay on track with coursework and meet deadlines.

The lack of external pressure and accountability can make it challenging for some learners to maintain focus and consistency in their studies. The convenience and accessibility of online learning can increase susceptibility to distractions, requiring learners to implement strategies for minimizing interruptions and creating conducive study environments.

💁🏼 Check out this guide on how to increase student engagement in online learning.

Quality assurance and accreditation concerns

With the wide variety of online courses and credentials available, learners must be extra careful when assessing the reputation, accreditation, and instructional quality of online programs .

Poorly designed or unaccredited courses may lack academic rigor, relevance, or recognition, undermining the value and credibility of the credentials obtained. This underscores the importance of conducting thorough research and due diligence when selecting online learning opportunities to ensure alignment with educational and career goals.

💁🏼 Here are 13 things to consider when determining the value of your online course .

Moving Forward: The Responsibility of Online Instructors & Course Creators

Our digitally-driven world makes everything possible today, and this is one of our biggest assets . Even the hardest challenges can be addressed and resolved effectively; all it takes is staying creative, flexible, and open to trying new things.

This goes out to not only online learners but especially to aspiring online instructors and course creators. Making digital learning a reality starts with a dream and a passion project. Once you have that everything else falls into place, having the right dose of determination and perseverance.

To make sure online learning environments are as inclusive and effective as should be, the next generation of educators needs to think about the instructional methods and strategies they are planning to use and select their equipment carefully.

Pedagogical considerations and instructional design challenges

Diving into the more theoretical and practical aspects of the work of educators , it’s important to go over some key pedagogical considerations and instructional design practices.

Below are some educational principles and strategies to take into account when creating online learning experiences:

Pedagogical Considerations

These are the principles and theories of teaching and learning that guide the design of online courses . Pedagogical considerations involve understanding how students learn best and selecting appropriate instructional methods and strategies to facilitate learning in an online environment.

This may include considerations such as active learning, learner-centered approaches, scaffolding of content, and the use of formative assessment to gauge student understanding.

💁🏼 Need help with course design? Accelerate Course Design with 18 Proven Course Templates

Instructional Design Challenges

These refer to the various hurdles and complexities that educators and instructional designers may face when creating effective online learning experiences.

Challenges may arise in areas such as content organization and sequencing , designing engaging and interactive activities, ensuring accessibility and inclusivity for all learners, managing learner engagement and motivation, and integrating technology tools effectively into the learning experience.

Instructional designers must address these challenges to create meaningful and impactful online courses.

Online course platforms, LMSs, and other tools

The technological means they will use to make this happen have to offer scalable capabilities , robust and advanced features, and provide the innovative solutions they need.

Must-have features in online learning platforms and LMSs include:

🧩 Assessments and feedback: Tools for providing timely and constructive feedback to learners, including automated quizzes, peer assessments, instructor feedback, and self-assessment activities, facilitate continuous improvement and reflection.

💬 Collaboration and social-building tools: Collaboration and communication among learners, instructors, and peers through virtual platforms, discussion forums, group projects, and collaborative tools, which can foster a sense of community and shared learning experiences.

📊 Detailed reporting & analytics: Track progress, monitor performance, and assess learning outcomes through data-rich analytics offered by an LMS, helping to facilitate informed decision-making and targeted interventions.

📝 SCORM-compliance: Ensures that your learning content aligns with the desirable e-learning market standards and is compatible with different LMSs. It allows for interoperability between various tools and platforms, ensuring seamless integration and consistent user experience across different systems.

📲 Mobile Learning: Use of mobile apps on devices such as smartphones and tablets to deliver educational content and facilitate learning activities. It enables learners to access educational resources anytime, anywhere, thus promoting flexibility and accessibility.

🎨 White-labeling: Removing the branding of the LMS provider to customize the appearance and branding of your e-learning website to align with your own brand identity. This can include customizing the platform’s logo, color scheme, and other visual elements.

🎮 Gamification: Involves integrating game design elements and mechanics into e-learning content to engage learners and motivate them to participate in learning activities via the use of points, badges, and leaderboards.

🎥 Live sessions: Real-time, synchronous learning experiences that offer instructor-led opportunities – instructors and learners interact with each other in virtual classrooms or webinars aiding collaboration, and engagement.

🛠️ Integrations: Ability to connect with other software systems and tools, such as CRM (Customer Relationship Management) systems, content repositories, video conferencing tools, and third-party applications, enabling seamless data exchange, and enhanced functionality.

💡 AI-powered functionality: Utilizes AI and machine learning algorithms to automate processes, personalize learning experiences, and provide intelligent insights. This enhances efficiency, effectiveness, and scalability in e-learning by leveraging advanced technologies to support learners and instructors throughout the learning journey.

Lead the Change as a Course Creator: Embrace Online Learning

In this article, we have explored the evolution of online learning, from its early days in computer-based instruction to its current status as a transformative force in education .

As we’ve seen, online learning holds immense potential for democratizing education by overcoming geographical barriers and providing access to unique learning experiences. For the modern digital creator, educator, and trainer, there are huge opportunities to teach online and monetize knowledge while empowering learners from all around the world.

By embracing innovative pedagogical approaches, and fostering interactive learning environments, you can easily create value-packed online courses that cater to the unique needs and preferences of your learners.

Start building your online academy by leveraging a robust learning platform like LearnWorlds . Try it out for free today!

Further reading you might find interesting:

- 183 Profitable Online Course Ideas With Examples

- How to Start a Profitable Online Course Business From Scratch

- Knowledge Economy: How to Sell Knowledge Online

- How to Create and Sell Profitable Online Courses: Step-by-Step Guide

- Sell Digital Downloads: The Complete Guide

- How Much Money Can You Make Selling Online Courses?

- How to Make Money on YouTube: 7 Ways to Monetize

Kyriaki Raouna

Kyriaki is a Content Creator for the LearnWorlds team writing about marketing and e-learning, helping course creators on their journey to create, market, and sell their online courses. Equipped with a degree in Career Guidance, she has a strong background in education management and career success. In her free time, she gets crafty and musical.

- Help Center

- Assignments

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Submit feedback

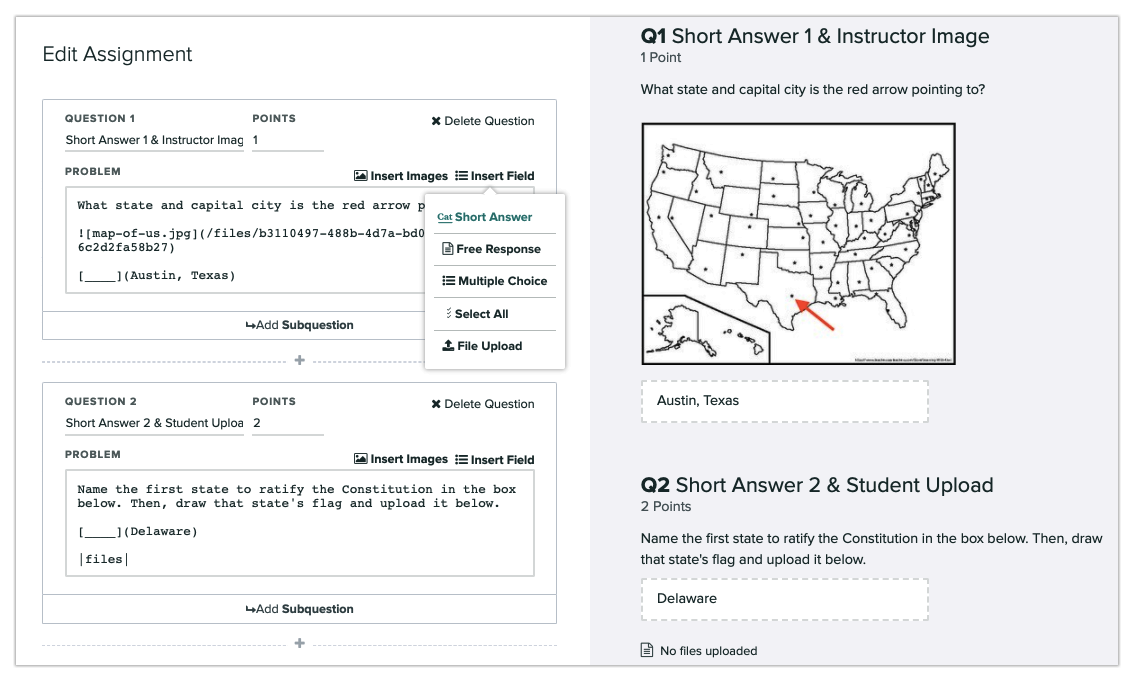

Create an assignment

Use Assignments to create, collect, and give feedback on assignments in a learning management system (LMS).

Before you begin

To use Assignments, you need an LMS and a Google Workspace for Education account. The account usually looks like [email protected] . If Assignments isn't installed in your LMS, ask your administrator to go to Get started with Assignments .

Create an assignment in Canvas

- Sign in to Canvas.

- Open the course.

- Enter a name and description for your assignment.

- When you set the points to zero, assignments are left ungraded in Google Assignments.

- Points that use a decimal value will be rounded down in Google Assignments.

- Due dates are imported automatically into Google Assignments if the Canvas assignment has a single due date for all students. Otherwise, the due date is left unset in Google Assignments.

- To save your assignment, click Save or Save & Publish .

- To confirm your changes and return to the rest of your assignment, click Edit .

- Tip : Your Canvas admin might have given Assignments a different name.

- If you’re signed in to your Google Workspace for Education account—Click Continue .

- If you’re not signed in—Sign in with your Google Workspace account.

- If this is your first time using Assignments in this course, you must link your LMS account to your Google Account. For instructions, go to Link your account to Assignments (below).

- Files students submit are shared with the instructor.

- Tip: Files students submit automatically upload to SpeedGrader™.

- Click Create .

Tip : Students can't see an assignment until you publish it.

Copy an assignment to another course in Canvas

- In the sidebar, click Assignments .

- Click Copy .

Use SpeedGrader with Google Drive files

If you create an assignment in Canvas, you can use SpeedGrader to grade students’ Drive files. However, you won’t be able to use the features included in Assignments. For details, go to Use SpeedGrader with Google Drive files in Canvas .

Create an assignment in Schoology

- Sign in to Schoology.

- In the sidebar, click Materials .

- Click Add Materials and select Google Assignments .

- If this is your first time using Assignments in this course, you must link your LMS account to your Google Account. For instructions, go to Link your account to Assignments (below).

- Enter a title for the assignment.

- (Optional) To edit the total points or add a due date or any other instructions, enter the details.

- Click Create .

- Open the assignment.

Create an assignment in another LMS

Setting up an assignment varies for each LMS. Contact your IT administrator. Or, for more information, go to the Assignments Help Community .

Link your account to Assignments

The first time you use Assignments in a course, you need to link your Google Workspace for Education account. When you do, Assignments creates a folder in Google Drive for student assignments and automatically sends grades to the LMS. Students can't submit classwork until you link your account. After you select Google Assignments as an external tool, choose an option based on whether you're:

Google, Google Workspace, and related marks and logos are trademarks of Google LLC. All other company and product names are trademarks of the companies with which they are associated.

Need more help?

Try these next steps:.

How Online Classes Work: 10 Frequently Asked Questions

Some online courses require students to attend and participate at set times through videoconferencing.

How Online Classes Work: FAQ

Getty Images

Online classes are typically a mix of video recordings or live lectures supplemented with readings and assessments that students can complete on their own time. But nothing is typical about education in 2020 as the coronavirus has forced a sudden migration to online learning with little time to prepare for it.

As the pandemic accelerated, colleges shifted into emergency mode, shutting down campuses in an effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19 – the disease caused by the novel coronavirus – and moving academic life online. Education experts anticipate more online classes this fall. For students – whether incoming freshmen, seasoned seniors or returning adult learners – here is an overview of what to know about and expect from online classes:

- How is an online classroom typically structured?

- Do students need to attend classes at specific times?

- Do online classes have in-person components?

- How do students interact in an online course?

- What is the typical workload for an online course?

- How many weeks do online classes run?

- What are typical assignments in online classes?

- How do students take proctored exams in online classes?

- What should students know before enrolling in an online course?

- Are there ways to accelerate online degree completion?

How Is an Online Classroom Typically Structured?

The structure of an online classroom varies, experts say. But generally, online students regularly log in to a learning management system, or LMS, a virtual portal where they can view the syllabus and grades; contact professors, classmates and support services; access course materials; and monitor their progress on lessons.

Experts say prospective students should check whether a school's LMS is accessible on mobile devices so they can complete coursework anytime, anywhere. They will also likely need a strong internet connection and any required software , such as a word processor.

One important distinction that experts note is that the forced shift to remote instruction that colleges saw this spring due to the coronavirus is not typical of online education . What students are experiencing in an online format as a result of the pandemic is "emergency remote teaching" says Lynette O'Keefe, director of research and innovation at the Online Learning Consortium.

"Emergency remote teaching forces faculty that have planned their semester in either a face-to-face or blended environment to be carried out fully online, and it forces students that were not necessarily expecting to complete their courses online to do so," O'Keefe says.

She expects courses in the fall to be designed for online offerings rather than hastily forced into the format.

Do Students Need to Attend Classes at Specific Times?

Online classes typically have an asynchronous, or self-paced, portion. Students complete coursework on their own time but still need to meet weekly deadlines, a format that offers flexibility for students .

Some online courses may also have a synchronous component, where students view live lectures online and sometimes participate in discussions through videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom. The latter model is the move many professors have made during the pandemic, experts say.

"It's effectively taking a physical classroom model and doing your best to deliver that over tools like Zoom," says Luyen Chou, chief learning officer at 2U, an online program management company.

Do Online Classes Have In-Person Components?

Some online classes may require students to attend a residency on the school's campus before or during the program. The lengths and details of these requirements vary.

Students may complete team-building activities, network and attend informational sessions. Especially in health fields like nursing , certain online programs may require working in a clinical setting.

How Do Students Interact in an Online Course?

If a course has a synchronous component or requires students to travel to campus, that's a good way to get to know classmates, experts say. Students may otherwise communicate through discussion forums, social media and – particularly for group work – videoconferencing, as well as phone and email.

Online learners interact with professors in similar ways, though they may need to be more proactive than on-campus students to develop a strong relationship . That may involve introducing themselves to their instructor before classes start and attending office hours if offered, Marian Stoltz-Loike, vice president for online education at Touro College in New York, wrote in a 2017 U.S. News blog post.

What Is the Typical Workload for an Online Course?

Just like in traditional classes, the workload varies – but don't expect your course to be easier just because it's online. Many online learners say they spend 15 to 20 hours a week on coursework. That workload, of course, may vary between full-time and part-time students. A lighter course load likely means less study.

At Arizona State University 's online arm – ASU Online – students typically spend six hours a week on coursework for each credit they enroll in, Joe Chapman, director of student services at the school, wrote in a 2015 U.S. News blog post .

How Many Weeks Do Online Classes Run?

While some online degree programs follow the traditional semester-based schedule, others divide the year into smaller terms , and graduation credit requirements may vary. ASU Online courses, for instance, are structured as seven-and-a-half week sessions rather than 14-week semesters.

Sometimes students can choose the number of courses they take at one time, while in other programs they must stick to a set curriculum road map as part of a cohort , experts say. Prospective students should determine whether the academic calendar is structured in a way that will enable them to balance work, school and family. They should also know that academic calendars vary by school.

While some schools have decided to tweak the format for fall 2020, most are sticking to the traditional academic calendar to avoid throwing even more changes at students amid the coronavirus pandemic, Chou says. "I think the majority of the folks that we have talked to have elected, at least for this fall, to preserve their semester structures, just in the interest of not changing everything at the same time."

What Are Typical Assignments in Online Classes?

Online course assignments depend largely on the discipline. But in general, students should expect assignments similar to those in on-ground programs, such as research papers and proctored exams in addition to online-specific assignments such as responding to professor-posed questions in a discussion board .

An online course may also require group projects where students communicate virtually, as well as remote presentations. These can be challenging for online learners, who often live across various time zones, Stoltz-Loike noted in a 2018 blog post .

How Do Students Take Proctored Exams in Online Classes?

Not all online classes have proctored exams . But if they do, online students may need to visit a local testing site with an on-site proctor. They may also take virtually monitored exams online, where a proctor watches via webcam or where computer software detects cheating by checking test-takers' screens.

With more classes likely online in fall 2020, experts expect an uptick in online exam proctoring.

What Should Students Know Before Enrolling in an Online Course?

Prospective students looking for how to start online college should visit the admissions page for the school. They should also understand the requirements for the degree program of interest to them, considering that there may be a higher threshold for certain majors compared with general admissions, experts recommend.

While the registration process for online and on-campus classes is often similar, prospective online students should review the course type and requirements before enrolling, experts say. They should also understand the requirements for dropping classes.

Are There Ways to Accelerate Online Degree Completion?

In some cases, it's possible to earn a degree faster.

For instance, in competency-based online learning , students move quickly through the material they already know and may spend more time on unfamiliar topics. In some programs, students may also earn credits for past work or military experience. Some universities even offer a subscription-based model, which allows students to sign up for various self-paced classes over several months.

Trying to fund your online education? Get tips and more in the U.S. News Paying for Online Education center.

Evaluate Online Program Student Services

Tags: online education , education , students , technology , colleges , Coronavirus

2024 Best Online Programs

Compare online degree programs using the new U.S. News rankings and data.

BEST ONLINE PROGRAMS FOR VETERANS

- Graduate Business

- Graduate Criminal Justice

- Graduate Education

- Graduate Engineering

- Graduate Info Tech

- Graduate Nursing

Online Education Advice

The Short List: Online Programs

Best Colleges

High Schools

Online Colleges

You May Also Like

20 lower-cost online private colleges.

Sarah Wood March 21, 2024

Basic Components of an Online Course

Cole Claybourn March 19, 2024

Attending an Online High School

Cole Claybourn Feb. 20, 2024

Online Programs With Diverse Faculty

Sarah Wood Feb. 16, 2024

Online Learning Trends to Know Now

Sarah Wood Feb. 8, 2024

Top Online MBAs With No GMAT, GRE

Cole Claybourn Feb. 8, 2024

Veterans Considering Online College

Anayat Durrani Feb. 8, 2024

Affordable Out-of-State Online Colleges

Sarah Wood Feb. 7, 2024

The Cost of an Online Bachelor's Degree

Emma Kerr and Cole Claybourn Feb. 7, 2024

How to Select an Online College

Cole Claybourn Feb. 7, 2024

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Instructional Technologies

- Teaching in All Modalities

Designing Assignments for Learning

The rapid shift to remote teaching and learning meant that many instructors reimagined their assessment practices. Whether adapting existing assignments or creatively designing new opportunities for their students to learn, instructors focused on helping students make meaning and demonstrate their learning outside of the traditional, face-to-face classroom setting. This resource distills the elements of assignment design that are important to carry forward as we continue to seek better ways of assessing learning and build on our innovative assignment designs.

On this page:

Rethinking traditional tests, quizzes, and exams.

- Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

- Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

Reflect On Your Assignment Design

Connect with the ctl.

- Resources and References

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Designing Assignments for Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/designing-assignments/

Traditional assessments tend to reveal whether students can recognize, recall, or replicate what was learned out of context, and tend to focus on students providing correct responses (Wiggins, 1990). In contrast, authentic assignments, which are course assessments, engage students in higher order thinking, as they grapple with real or simulated challenges that help them prepare for their professional lives, and draw on the course knowledge learned and the skills acquired to create justifiable answers, performances or products (Wiggins, 1990). An authentic assessment provides opportunities for students to practice, consult resources, learn from feedback, and refine their performances and products accordingly (Wiggins 1990, 1998, 2014).

Authentic assignments ask students to “do” the subject with an audience in mind and apply their learning in a new situation. Examples of authentic assignments include asking students to:

- Write for a real audience (e.g., a memo, a policy brief, letter to the editor, a grant proposal, reports, building a website) and/or publication;

- Solve problem sets that have real world application;

- Design projects that address a real world problem;

- Engage in a community-partnered research project;

- Create an exhibit, performance, or conference presentation ;

- Compile and reflect on their work through a portfolio/e-portfolio.

Noteworthy elements of authentic designs are that instructors scaffold the assignment, and play an active role in preparing students for the tasks assigned, while students are intentionally asked to reflect on the process and product of their work thus building their metacognitive skills (Herrington and Oliver, 2000; Ashford-Rowe, Herrington and Brown, 2013; Frey, Schmitt, and Allen, 2012).

It’s worth noting here that authentic assessments can initially be time consuming to design, implement, and grade. They are critiqued for being challenging to use across course contexts and for grading reliability issues (Maclellan, 2004). Despite these challenges, authentic assessments are recognized as beneficial to student learning (Svinicki, 2004) as they are learner-centered (Weimer, 2013), promote academic integrity (McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, 2021; Sotiriadou et al., 2019; Schroeder, 2021) and motivate students to learn (Ambrose et al., 2010). The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning is always available to consult with faculty who are considering authentic assessment designs and to discuss challenges and affordances.

Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

Columbia instructors have experimented with alternative ways of assessing student learning from oral exams to technology-enhanced assignments. Below are a few examples of authentic assignments in various teaching contexts across Columbia University.

- E-portfolios: Statia Cook shares her experiences with an ePorfolio assignment in her co-taught Frontiers of Science course (a submission to the Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning initiative); CUIMC use of ePortfolios ;

- Case studies: Columbia instructors have engaged their students in authentic ways through case studies drawing on the Case Consortium at Columbia University. Read and watch a faculty spotlight to learn how Professor Mary Ann Price uses the case method to place pre-med students in real-life scenarios;

- Simulations: students at CUIMC engage in simulations to develop their professional skills in The Mary & Michael Jaharis Simulation Center in the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Helene Fuld Health Trust Simulation Center in the Columbia School of Nursing;

- Experiential learning: instructors have drawn on New York City as a learning laboratory such as Barnard’s NYC as Lab webpage which highlights courses that engage students in NYC;

- Design projects that address real world problems: Yevgeniy Yesilevskiy on the Engineering design projects completed using lab kits during remote learning. Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy talk about his teaching and read the Columbia News article .

- Writing assignments: Lia Marshall and her teaching associate Aparna Balasundaram reflect on their “non-disposable or renewable assignments” to prepare social work students for their professional lives as they write for a real audience; and Hannah Weaver spoke about a sandbox assignment used in her Core Literature Humanities course at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium . Watch Dr. Weaver share her experiences.

Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

While designing an effective authentic assignment may seem like a daunting task, the following tips can be used as a starting point. See the Resources section for frameworks and tools that may be useful in this effort.

Align the assignment with your course learning objectives

Identify the kind of thinking that is important in your course, the knowledge students will apply, and the skills they will practice using through the assignment. What kind of thinking will students be asked to do for the assignment? What will students learn by completing this assignment? How will the assignment help students achieve the desired course learning outcomes? For more information on course learning objectives, see the CTL’s Course Design Essentials self-paced course and watch the video on Articulating Learning Objectives .

Identify an authentic meaning-making task

For meaning-making to occur, students need to understand the relevance of the assignment to the course and beyond (Ambrose et al., 2010). To Bean (2011) a “meaning-making” or “meaning-constructing” task has two dimensions: 1) it presents students with an authentic disciplinary problem or asks students to formulate their own problems, both of which engage them in active critical thinking, and 2) the problem is placed in “a context that gives students a role or purpose, a targeted audience, and a genre.” (Bean, 2011: 97-98).

An authentic task gives students a realistic challenge to grapple with, a role to take on that allows them to “rehearse for the complex ambiguities” of life, provides resources and supports to draw on, and requires students to justify their work and the process they used to inform their solution (Wiggins, 1990). Note that if students find an assignment interesting or relevant, they will see value in completing it.

Consider the kind of activities in the real world that use the knowledge and skills that are the focus of your course. How is this knowledge and these skills applied to answer real-world questions to solve real-world problems? (Herrington et al., 2010: 22). What do professionals or academics in your discipline do on a regular basis? What does it mean to think like a biologist, statistician, historian, social scientist? How might your assignment ask students to draw on current events, issues, or problems that relate to the course and are of interest to them? How might your assignment tap into student motivation and engage them in the kinds of thinking they can apply to better understand the world around them? (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Determine the evaluation criteria and create a rubric

To ensure equitable and consistent grading of assignments across students, make transparent the criteria you will use to evaluate student work. The criteria should focus on the knowledge and skills that are central to the assignment. Build on the criteria identified, create a rubric that makes explicit the expectations of deliverables and share this rubric with your students so they can use it as they work on the assignment. For more information on rubrics, see the CTL’s resource Incorporating Rubrics into Your Grading and Feedback Practices , and explore the Association of American Colleges & Universities VALUE Rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education).

Build in metacognition

Ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the assignment. Help students uncover personal relevance of the assignment, find intrinsic value in their work, and deepen their motivation by asking them to reflect on their process and their assignment deliverable. Sample prompts might include: what did you learn from this assignment? How might you draw on the knowledge and skills you used on this assignment in the future? See Ambrose et al., 2010 for more strategies that support motivation and the CTL’s resource on Metacognition ).

Provide students with opportunities to practice

Design your assignment to be a learning experience and prepare students for success on the assignment. If students can reasonably expect to be successful on an assignment when they put in the required effort ,with the support and guidance of the instructor, they are more likely to engage in the behaviors necessary for learning (Ambrose et al., 2010). Ensure student success by actively teaching the knowledge and skills of the course (e.g., how to problem solve, how to write for a particular audience), modeling the desired thinking, and creating learning activities that build up to a graded assignment. Provide opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills they will need for the assignment, whether through low-stakes in-class activities or homework activities that include opportunities to receive and incorporate formative feedback. For more information on providing feedback, see the CTL resource Feedback for Learning .

Communicate about the assignment

Share the purpose, task, audience, expectations, and criteria for the assignment. Students may have expectations about assessments and how they will be graded that is informed by their prior experiences completing high-stakes assessments, so be transparent. Tell your students why you are asking them to do this assignment, what skills they will be using, how it aligns with the course learning outcomes, and why it is relevant to their learning and their professional lives (i.e., how practitioners / professionals use the knowledge and skills in your course in real world contexts and for what purposes). Finally, verify that students understand what they need to do to complete the assignment. This can be done by asking students to respond to poll questions about different parts of the assignment, a “scavenger hunt” of the assignment instructions–giving students questions to answer about the assignment and having them work in small groups to answer the questions, or by having students share back what they think is expected of them.

Plan to iterate and to keep the focus on learning

Draw on multiple sources of data to help make decisions about what changes are needed to the assignment, the assignment instructions, and/or rubric to ensure that it contributes to student learning. Explore assignment performance data. As Deandra Little reminds us: “a really good assignment, which is a really good assessment, also teaches you something or tells the instructor something. As much as it tells you what students are learning, it’s also telling you what they aren’t learning.” ( Teaching in Higher Ed podcast episode 337 ). Assignment bottlenecks–where students get stuck or struggle–can be good indicators that students need further support or opportunities to practice prior to completing an assignment. This awareness can inform teaching decisions.

Triangulate the performance data by collecting student feedback, and noting your own reflections about what worked well and what did not. Revise the assignment instructions, rubric, and teaching practices accordingly. Consider how you might better align your assignment with your course objectives and/or provide more opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills that they will rely on for the assignment. Additionally, keep in mind societal, disciplinary, and technological changes as you tweak your assignments for future use.

Now is a great time to reflect on your practices and experiences with assignment design and think critically about your approach. Take a closer look at an existing assignment. Questions to consider include: What is this assignment meant to do? What purpose does it serve? Why do you ask students to do this assignment? How are they prepared to complete the assignment? Does the assignment assess the kind of learning that you really want? What would help students learn from this assignment?

Using the tips in the previous section: How can the assignment be tweaked to be more authentic and meaningful to students?

As you plan forward for post-pandemic teaching and reflect on your practices and reimagine your course design, you may find the following CTL resources helpful: Reflecting On Your Experiences with Remote Teaching , Transition to In-Person Teaching , and Course Design Support .

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) is here to help!

For assistance with assignment design, rubric design, or any other teaching and learning need, please request a consultation by emailing [email protected] .

Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework for assignments. The TILT Examples and Resources page ( https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources ) includes example assignments from across disciplines, as well as a transparent assignment template and a checklist for designing transparent assignments . Each emphasizes the importance of articulating to students the purpose of the assignment or activity, the what and how of the task, and specifying the criteria that will be used to assess students.