Breast cancer nursing interventions and clinical effectiveness: a systematic review

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Cancer Services, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Metro South Health, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia [email protected].

- 2 School of Nursing and Cancer and Palliative Care Outcomes Centre, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

- 3 School of Medicine, Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

- 4 McGrath Foundation, North Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

- PMID: 32499405

- DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002120

Objectives: To examine the effects of nurse-led interventions on the health-related quality of life, symptom burden and self-management/behavioural outcomes in women with breast cancer.

Methods: Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline and Embase databases were searched (January 1999 to May 2019) to identify randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled before-and-after studies of interventions delivered by nurses with oncology experience for women with breast cancer. Risk of bias was evaluated using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials . Intervention effects were synthesised by cancer trajectory using The Omaha System Intervention Classification Scheme .

Results: Thirty-one RCTs (4651 participants) were included. All studies were at risk of bias mainly due to inherent limitations such as lack of blinding and self-report data. Most studies (71%; n=22) reported at least one superior intervention effect. There were no differences in all outcomes between those who receive nurse-led surveillance care versus those who received physical led or usual discharge care. Compared with control interventions, there were superior teaching, guidance and counselling (63%) and case management (100%) intervention effects on symptom burden during treatment and survivorship. Effects of these interventions on health-related quality of life and symptom self-management/behavioural outcomes were inconsistent.

Discussion: There is consistent evidence from RCTs that nurse-led surveillance interventions are as safe and effective as physician-led care and strong evidence that nurse-led teaching, guidance and counselling and case management interventions are effective for symptom management. Future studies should ensure the incorporation of health-related quality of life and self-management/behavioural outcomes and consider well-designed attentional placebo controls to blind participants for self-report outcomes.

Protocol registration: The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42020134914).

Keywords: breast; quality of life; survivorship; symptoms and symptom management.

© Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Breast Neoplasms / nursing*

- Disease Management

- Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing / methods*

- Palliative Care / methods*

- Practice Patterns, Nurses' / statistics & numerical data*

- Quality of Life*

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

- Treatment Outcome

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Instructions for Authors

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 10, Issue 3

- Breast cancer nursing interventions and clinical effectiveness: a systematic review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0248-7046 Raymond Javan Chan 1 , 2 ,

- Laisa Teleni 2 ,

- Suzanne McDonald 2 ,

- Jaimon Kelly 3 ,

- Jane Mahony 4 ,

- Kerryn Ernst 4 ,

- Kerry Patford 4 ,

- James Townsend 4 ,

- Manisha Singh 4 and

- Patsy Yates 2

- 1 Division of Cancer Services , Princess Alexandra Hospital, Metro South Health , Woolloongabba , Queensland , Australia

- 2 School of Nursing and Cancer and Palliative Care Outcomes Centre , Queensland University of Technology , Brisbane , Queensland , Australia

- 3 School of Medicine , Griffith University , Brisbane , Queensland , Australia

- 4 McGrath Foundation , North Sydney , New South Wales , Australia

- Correspondence to Professor Raymond Javan Chan, Division of cancer Services, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Woolloongabba, QLD 4029, Australia; Raymond.Chan{at}qut.edu.au

Objectives To examine the effects of nurse-led interventions on the health-related quality of life, symptom burden and self-management/behavioural outcomes in women with breast cancer.

Methods Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline and Embase databases were searched (January 1999 to May 2019) to identify randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled before-and-after studies of interventions delivered by nurses with oncology experience for women with breast cancer. Risk of bias was evaluated using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials . Intervention effects were synthesised by cancer trajectory using The Omaha System Intervention Classification Scheme .

Results Thirty-one RCTs (4651 participants) were included. All studies were at risk of bias mainly due to inherent limitations such as lack of blinding and self-report data. Most studies (71%; n=22) reported at least one superior intervention effect. There were no differences in all outcomes between those who receive nurse-led surveillance care versus those who received physical led or usual discharge care. Compared with control interventions, there were superior teaching, guidance and counselling (63%) and case management (100%) intervention effects on symptom burden during treatment and survivorship. Effects of these interventions on health-related quality of life and symptom self-management/behavioural outcomes were inconsistent.

Discussion There is consistent evidence from RCTs that nurse-led surveillance interventions are as safe and effective as physician-led care and strong evidence that nurse-led teaching, guidance and counselling and case management interventions are effective for symptom management. Future studies should ensure the incorporation of health-related quality of life and self-management/behavioural outcomes and consider well-designed attentional placebo controls to blind participants for self-report outcomes.

Protocol registration The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42020134914).

- quality of life

- survivorship

- symptoms and symptom management

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002120

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Breast care nurses (BCNs) are a specialist workforce to support people with breast cancer through their disease experience, predominantly in well-resourced healthcare systems. 1 BCNs were initially introduced into the health systems in the UK, Australia, USA and parts of Europe over the last three decades to facilitate continuity of care and psychosocial support. 2 3 Yates et al defined the BCN as ‘a registered nurse who applies advanced knowledge of the health needs, preferences and circumstances of women with breast cancer to optimise the individual’s health and well-being at various phases across the continuum of care, including diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, follow-up and palliative care’. 4

As early as the introduction of BCNs, there was a recognition that the model of care for BCNs should be informed by the best available evidence. 2 5 At the early stage of implementation, there were a few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) 6–10 providing direct evidence to inform the model of care. 5 In addition to the evidence from these RCTs, the model was also informed by evidence-based recommendations, relevant management guidelines and training curricula available at the time. 2 3

Over the past 20 years, there have been significant changes in the landscape of breast cancer treatment. People with a breast cancer diagnosis are now living longer, especially among those with early stage disease. In developed countries, the overall 5-year relative survival rate is approximately 90% in the USA, UK and Australia. 11 A 2008 Cochrane review of five randomised studies examined the effects of supportive care provided by specialist BCNs, three of which tested psychosocial interventions during diagnosis and early treatment and one study each that tested supportive care during radiotherapy and post-treatment follow-up interventions. 1 The review concluded that there was limited evidence to inform BCNs’ model of care. 1 Over the past 10 years, the literature has grown enormously. A recent scoping review conducted by Charalambous et al 12 identified 214 RCT, quasi-RCT and controlled before-and-after (CBA) studies assessing the impacts of nurse-led interventions offered to patients with any cancer diagnosis. 12 However, this review did not use systematic review methods and was not breast cancer specific. Therefore, the findings were not directly relevant for understanding the BCN’s role in supporting patients with breast cancer. A systematic review of the current literature examining the effects of nurse-led interventions for people with breast cancer is warranted, to inform the evolution of the BCN model within Australia and internationally.

This was a systematic review of RCTs and high-quality CBA studies (study designs as defined by the Cochrane Effective Practice Organisation of Care) 13 that examined the effects of interventions provided by specialist cancer nurses to patients with breast cancer. This review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement 14 (protocol registration: The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42020134914).

Search strategy

A complete list of searches is listed in online supplementary A . The search terms were devised by the study authors. Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL, Medline and Embase databases were searched up to May 2019. The search strategy was adapted for use with each bibliographic database and included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, where available, and keywords relating to the population (breast care/cancer nurses) and any structured interventions (eg, nurse-led services, psychoeducational programmes, cognitive–behavioural therapies and symptom management programmes). The search was limited to English articles published in the past 20 years (1999–2019) to account for significant changes in treatment and patient experiences that have occurred over the past 20 years due to the advances in treatment options and increased expectation of the specialist cancer nurse role. Reference lists of relevant articles were hand searched, and authors of any included articles were searched for additional articles.

Supplemental material

Selection criteria.

Studies were included where: (1) interventionists were nurses with experience in oncology; (2) the effects of interventions delivered by these nurses could be isolated and evaluated against a comparison group (ie, usual care or other control); (3) the population was patients with breast cancer (and their family members) or the healthcare system. Studies of patients with mixed cancer diagnoses were only included if ≥80% of the study sample comprised patients with breast cancer or where the results for patients with breast cancer were reported separately. Studies that focused on family members and excluded patients, or studies where the effects of the nurse interventionist could not be separated from other interventionists, were excluded. Outcomes of interest were guided by a systematic review examining the effects of nurse-led services in chronic disease management. 15 These included any valid measures of patient-reported outcomes (ie, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), symptom burden, self-management and behaviour), survival and measures of patient and/or family member satisfaction or perception of the quality of care, service delivery and healthcare professional satisfaction.

Data collection

Records identified by the search strategy were imported into Endnote and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of records were independently screened for relevance by two reviewers (SM and LT). Full reports of all potentially relevant trials were then retrieved independently assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria by two reviewers (LT and SM). Disagreements were resolved in consultation between the two reviewers, or with a third reviewer (RC) where consensus could not be reached. Reference lists of articles were screened for additional potentially relevant references.

A standardised data extraction template was piloted for use with three studies and refined before extracting data from the remaining included studies. Data extracted included study design, aim of the study, setting or nature of healthcare service, location, characteristics of the nurse interventionists, key components of the intervention (dose, administration and content), length of the study, outcome measures, data collection methods, reported results (specific to the primary and secondary outcomes), reported conclusions, strengths and limitations. Data were extracted by one reviewer (LT) and cross checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (SM).

Data synthesis

Outcomes were not pooled as the outcomes were not considered comparable across trials. Given the clinical heterogeneity across the studies with a number of different study populations (pre, during and post various treatment types, and survivorship), a narrative approach to synthesis was used. Mean difference for continuous data or ORs for categorical data and 95% CIs were calculated between intervention and control groups at the study endpoint where authors reported significant findings ( online supplementary table 2 ). All studies were categorised by stage of cancer trajectory in which the intervention was delivered (ie, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, end of life) and intervention and problem classification schemes using the Omaha System 16 with additional descriptors provided by Charalambous et al 12 to guide decisions. The Omaha System 16 provides a taxonomy for classifying interventions and categorising problems addressed by these interventions. In addition to the guidance provided by the scheme, we categorised interventions into the four categories ( treatments and procedures, case management, surveillance, and teaching, guidance and counselling ). The Omaha System 16 categorises problems into four domains: environmental (ie, material resource, physical surroundings), psychosocial (ie, behaviour, emotion, communication and relationships), physiological (ie, functions and processes that maintain life) and health-related behaviours (ie, patterns of activity that maintain wellness, recovery or decrease risk of disease).

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2, Version 15 March 2019), 17 which evaluates risk of bias arising from the following five domains: (1) randomisation process; (2) deviations from the intended interventions; (3) missing outcome data; (4) measurement of the outcome and (5) selection of the reported result. Each domain was assigned a risk of bias (low risk, some concerns or high risk) based on the domain algorithm and an overall judgement (low risk, some concerns or high risk) was made using the described criteria. Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study (SM and JK). Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (LT).

Overview of included studies

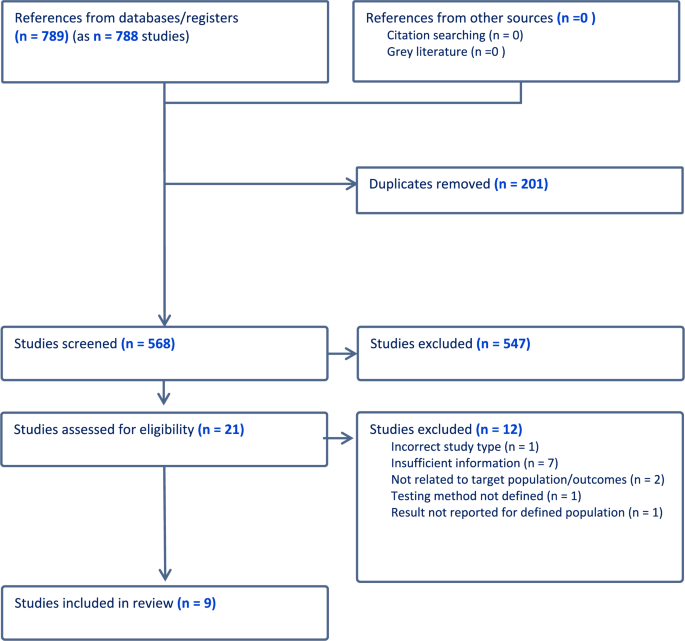

A total of 39 articles reporting 31 RCTs (4651 participants, range 18–408) and no CBA studies were included in this review ( figure 1 ) from the initial search, with no new articles identified from the snowball search. Characteristics of included studies and interventions are summarised in online supplementary table 1 and the results of included studies are summarised in online supplementary table 2 . Studies were predominantly conducted in the USA (n=10), UK (n=4), Australia (n=3) and Sweden (n=3). The aims of studies were to establish the effectiveness, 18–44 pilot test the feasibility or acceptability, 45–49 and/or to conduct an economic evaluation 50–53 of the intervention(s).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram showing the selection of studies. BC, breast cancer; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Interventionist experience, qualifications and training

All included studies indicated that the nurse interventionist(s) had experience in cancer care with 10 studies reporting specific experience in breast cancer care ( online supplementary table 1 ). Five studies reported the actual or minimum required years of experience in cancer care and/or breast cancer care (range 3–20 years). 34 38 43 44 46 Nurse interventionist qualifications were described in four studies, two included masters-prepared nurses, 36 46 one described the interventionist requirements as high diploma degree in nursing or higher degree 44 and one interventionist was the primary author whose qualifications were listed as RN and PhD. 41 Sixteen studies described interventionist training. 19 23–25 27–31 33 34 36 40 43 47 Training content included administering and adhering to the intervention and/or research protocols, human research ethics and evidence-based practice updates. Trainer expertise was described in two studies 23 25 (ie, specialist nurses, oncologists clinical psychologist) and five studies described training duration (range 8 hours to 12 months). 19 25 33 34 43

The risk of bias in each study is outlined in table 1 . All studies were judged to be at high overall risk of bias for at least one outcome. Across all studies, the lowest risk of bias was in the randomisation process. The domains with the highest risk of bias across all studies were measurement of the outcome, missing outcome data and deviations from interventions. The largest contributors to risk of bias was lack of information about missing data and its potential impact on the true value of the outcome and the impact of the lack of blinding on self-report outcomes.

- View inline

Risk-of-bias judgements of included studies

Intervention effects

A heat map of intervention effects by Omaha intervention category and cancer trajectory is summarised in table 2 . Twenty-two studies (71%) reported at least one superior nurse-led intervention effect ( table 2 ). Of the studies that reported superior nurse-led intervention effects on HRQoL (32%) and that measured secondary outcomes, all had at least 1 and 83% had at least 2 superior effects on secondary outcomes ( online supplementary tables 3–9 ). Eighteen RCTs were conducted during treatment, 12 during survivorship and 1 conducted from diagnosis to survivorship. Problem domains were psychosocial (n=10), health-related behaviours (n=8) or a combination of both (n=12) with one study also including physiological . Most of the study interventions were categorised as teaching, guidance and counselling (n=19; 2569 participants). All teaching, guidance and counselling interventions were structured and delivered by at least one (range: 1–7) oncology nurse. These interventions were mostly delivered individually with the exception of two group education interventions (254 total participants). 31 39 Five study interventions were categorised as case management (606 participants) and compared with usual care. Three interventions were unstructured, requiring patient-initiated contact 20 40 48 and two were structured 44 46 interventions delivered face-to-face, by telephone and/or online by an experienced oncology nurse. In addition to case management, two interventions included counselling and education. Seven study interventions were categorised as surveillance (1476 participants). These interventions replaced usual follow-up care with nurse-led follow-up care with the exception of Wells et al 50 who replaced usual hospital postoperative discharge with nurse-led early discharge. Surveillance interventions were predominantly delivered by telephone (n=6) and unstructured (n=4) requiring patient-initiated contact with a BCN or other experienced oncology nurse. There were no treatment and procedure interventions.

The distribution of intervention effects by Omaha system intervention category on all health-related outcomes across the cancer trajectory

During treatment

The most tested interventions during treatment were teaching, guidance and counselling (n=15; 1987 participants). Of these, three tested interventions in addition to usual care and compared with a usual care 18 42 or other non-descript control 38 and 12 lacked sufficient information to judge whether usual care was part of the intervention arm(s). Of these 12 RCTs, 6 were compared with usual care, 19 23 25 27 39 47 5 compared with attentional controls or other interventions 24 28–30 43 and 1 did not describe the control condition. 21 No intervention was inferior to control for any outcome and 67% (n=10) were superior in at least one outcome. Superior intervention effects were most common for symptom resolution or overall burden (n=8, 67%). Superior effects were also reported in 60% (n=4) of the studies that measured self-management/behavioural outcomes and 33% (n=4) of the studies that measured HRQoL. One RCT that compared cognitive–behavioural therapy delivered by a nurse versus cognitive–behavioural therapy delivered by a psychologist versus usual care reported greater patient satisfaction in the intervention groups, with greater perceived benefits from the nurse-led intervention. 26 Moreover, this study reported that usual care incurred higher hospitalisation and total healthcare costs. 54

Case management intervention studies evaluated in 2 studies of 300 participants collectively were compared with usual care. In one study, the intervention was delivered in addition to usual care 44 while the other study was unclear. 40 Both studies reported superior effects on symptom burden outcomes, equivocal effects on self-management/behavioural outcomes and one study reported equivocal effects on HRQoL. One RCT evaluated health service/resource use and costs throughout four or six cycles of chemotherapy. 44 53 In those undergoing four cycles of chemotherapy, intervention participants incurred a higher per patient cost with an equivocal quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) compared with usual care. In comparison, those undergoing six cycles, intervention participants incurred lower per patient costs and fewer emergency department visits, but fewer QALYs compared with usual care.

One surveillance intervention study (108 participants) 50 compared early nurse-led postoperative discharge with usual hospital discharge. Wells et al 50 reported equivocal effects of the early nurse-led discharge for HRQoL, symptom burden and self-management/behavioural outcomes. However, nurse-led postoperative early discharge saved 2.26 bed days per patient and was associated with a reduction in cancellations of 2.9 per month and subsequent cost savings. Moreover, Wells et al 50 reported that significantly more interventions participants would opt for the same care again.

During survivorship

The most tested interventions during survivorship were surveillance (n=6, 1368 participants), all of which compared nurse-led follow-up care (including annual mammography) with usual physician-led follow-up care. Four surveillance interventions relied on patient-initiated contacts and were delivered via telephone 22 34 49 or combined telephone/face to face 51 and two mimicked usual physician follow-up care as per study site. Irrespective of the mode or structure of follow-up care, nurse-led intervention effects were equivocal to physician-led care for HRQoL (n=4), symptom burden (n=6), self-management/behavioural outcomes (n=1) and 5-year time to all-cause death (n=1; table 1 ). Moreover, of the three studies that measured patient satisfaction with care, only Beaver et al 33 found significantly greater patient satisfaction in the nurse-led intervention arm compared with usual care. In terms of health service/resource use and costs, Koinberg et al 51 reported that fewer visits to the physician resulted in lower per patient cost. Similarly, Kimman et al 36 compared nurse led with usual follow-up care with and without a group education programme and reported that nurse-led follow-up care combined with the exercise education was the most cost effective in terms of QALYs.

There were four teaching, guidance and counselling interventions (582 participants). Although most studies reported significant improvements in symptom burden (three of four studies) and self-management/behaviour (two of three studies), only two of four studies reported improvements in HRQoL, one of which was not sustained at final follow-up of 16 weeks ( table 1 ). Three studies aimed to improve symptoms using counselling and exercise, 31 cognitive–behavioural therapy 41 or psychoeducation 45 and one tested the effect of a nurse-developed survivorship care plan in conjunction with general practitioner (GP)-led care. 37 Only one study 37 measured patient satisfaction with care, reporting that satisfaction with coordination and continuity of care was equivocal between those under GP-led follow-up care with and without a nurse-developed supportive care plan.

There were two case management interventions (95 participants). Mertz et al 48 replaced usual rehabilitation care with nurse-led follow-up and counselling and reported significant improvements in symptom burden (ie, distress, anxiety, depression) and satisfaction with treatment and rehabilitation, but no difference in HRQoL. Kim et al 46 conducted a telephone-based diet and exercise interventions matched to the patient’s stage of change. Compared with usual care, there were significantly greater improvements in symptom burden, stages of change and emotional functioning. However, the intervention had equivocal effects on all other HRQoL measures, anxiety and physical activity compared with usual care.

Diagnosis to survivorship

One study was conducted from diagnosis through to survivorship, testing a 2-year nurse-led case management intervention (211 participants) compared with usual care. 20 The nurse-led case management had superior effects on disease-specific HRQoL, but only for unmarried women at 1 month; otherwise, the effects were equivocal to usual care over 12 months for the unmarried subgroup and entire participant. Improvements in mood disturbance were greater in the intervention arm at 1 and 3 months, but this difference was only sustained to 6 months in women with no family history of breast cancer. There was no difference in costs between nurse-led intervention and usual care, and most (75%) of the intervention nurse-related costs and time was attributable to the first 6 months of the intervention. Patient satisfaction was not investigated in this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest systematic review examining high-level evidence of the effectiveness of interventions delivered by nurses with experience in oncology for patients across the postdiagnosis breast cancer trajectory, including 31 original research studies of 4651 participants. While several reviews of nurse-led interventions in cancer exist in the literature, 1 55–58 this review focusses on interventions delivered to patients with breast cancer by nurses with oncology experience or expertise for relevant outcomes guided by taxonomy developed by Chan et al . 15 Using the Omaha intervention categorisation system, 16 we identified three intervention categories implemented during breast cancer treatment and survivorship or over the entire breast cancer trajectory. Compared to the 2008 Cochrane review, 1 our review not only provides inclusion of new studies published over the past 12 years, it also has a wider inclusion of studies that are delivered by any nurses with oncology experience, as opposed to only those with a specialist title of BCNs.

The most tested intervention was teaching, guidance and counselling in this review. This finding is consistent with Charalambous et al 12 scoping review that reported teaching, guidance and counselling interventions are most tested in both breast cancer and during treatment in any cancer. However, Charalambous’s review had a wide focus including all cancer types and did not specifically report effectiveness outcomes for these interventions for patients with breast cancer. 12 The current review suggests that during treatment, most teaching, guidance and counselling intervention studies reported at least one superior outcome (67%) including HRQoL (n=4), symptom burden (n=8), self-management/behavioural outcomes (n=4), patient satisfaction (n=4) and health service/resource use and costs outcomes (n=1).

Similar to teaching, guidance and counselling interventions, there is consistent evidence from RCTs that case management is effective for managing symptom burden in patients with breast cancer whether during treatment, 40 44 survivorship 46 48 or across the entire cancer trajectory. 20 The effectiveness of case management interventions on HRQoL and self-management/behaviour is less clear with superior intervention effects reported in 50% (n=2) and 25% (n=1), respectively. One study measured and reported greater patient satisfaction with treatment and rehabilitation in the nurse-led intervention group compared with usual care and two studies reported no overall difference in health service/resource use or costs outcomes. Thus far, evidence of effectiveness from the wider care coordination literature is conflicting. In a systematic review including 59 studies of patients with mixed-cancer types, it was reported that care coordination had no effect on HRQoL and symptom burden, but that patients with coordinated care felt more satisfied. 59 A more recent systematic review of observational studies and RCTs (n=52) in patients with cancer reported that coordination improved 81% of outcomes in patients and resulted in significantly higher odds of appropriate healthcare utilisation. 60

Surveillance interventions were the second most tested intervention in breast cancer and the most tested during survivorship and exclusively involved nurse-led follow-up care or early postoperative discharge instead of usual follow-up care or hospital discharge, respectively. The included RCTs consistently reported that nurse-led surveillance interventions in the survivorship phase were comparable to physician-led clinics for HRQoL, 22 34 36 49 50 symptom burden, 22 32–34 36 49 50 survival 32 and self-management/behavioural outcomes. 36 50 These studies also indicated that nurse-led follow-up care had greater health service/resource use and cost benefits 32 36 50 and patient satisfaction with care. 33 50 It is important to ensure that any nurse-led or shared-care model capitalises on the full potential of a nurse interventionist by preparing nurses to incorporate concurrent teaching, guidance and counselling and surveillance interventions. However, future studies should consider the additional preparation of nurses when evaluating cost effectiveness.

We did not identify any study with an overall inferior intervention effect for any outcome; however, one study did have conflicting health utility/costs outcomes. Lai et al 53 reported lower per person costs, but significantly fewer QALY health gains in the nurse-led case management intervention group that included counselling for self-care strategies and psychosocial support compared with usual care in a subgroup of patients receiving six cycles of chemotherapy, but not four cycles. However, this was a feasibility study and the authors recognise the limitations of a relatively small sample size (n=124) and the potential underestimation of QALY benefit from using a transformed quality of life score.

Similar to a previous review that had a broader focus of nurse-led services in all chronic conditions, 15 we identified insufficient reporting of interventionist qualifications and their levels of experience in oncology. Of the 31 included studies, only three studies listed the educational requirements for the interventionist. Further, although study-specific training was described by 16 studies, the depth of information about the content, duration and trainer expertise was highly variable and generally poorly reported. As such, we are unable to make recommendations about the skilling or requirements of nurses for implementing these interventions. Future studies should include such information as it is important for implementation of evidence into practice.

All studies were assessed as being at high risk of bias for at least one outcome. The Cochrane Revised Risk of Bias tool deems an overall high risk of bias for any study outcome with a high risk in at least one domain or some concerns in multiple domains in a way that substantially lowers confidence in the result. 17 The main attributor to overall high risk judgements was the lack blinding. Previous Cochrane reviews of psychosocial interventions in breast cancer highlighted blinding as a limitation of these complex interventions, but recommend that as a minimum the blinding of outcome assessors should be considered to improve the rigour of these studies. 61 62 However, blinding of outcome assessors for participant-reported outcomes (eg, HRQoL) where the participant is the assessor is not feasible in an unblinded complex intervention. In the current review, the lack of blinding, contributed to the missing outcome data domain where missing data in the outcome likely depended on its true value (particularly for self-reported outcomes), placing studies at risk of social desirability bias. Several studies attempted an attentional control which is highly recommended for these types of RCTs 63 ; however, reporting of blinding in these studies was often absent. In addition, it was often unclear as to whether participants were blinded or whether the control activities, such as providing information and resources on breast cancer and providing support, were associated with the study outcomes. One exception was Matthews et al 41 who implemented a previously tested attentional placebo control. Future studies should consider adopting attentional placebo control or a well-designed attentional control and provide information on blinding.

The majority of RCTs with a large sample size reported a positive effect of nurse-led teaching guidance and counselling interventions on symptom burden during treatment and survivorship. The benefits of these nurse-led interventions are less clear for HRQoL and self-management/behavioural outcomes and there is insufficient evidence of effects on survival outcomes, health service/resource use and cost, and perceived intervention benefits and patient satisfaction. Findings from this review suggest that teaching, guidance and counselling interventions are effective for alleviating symptom burden, but more research is needed to evaluate the effects on HRQoL, self-management/behaviour, survival, health service/resource use and cost, perceived intervention benefits and patient satisfaction.

During treatment, there is consistent evidence from two studies with large sample sizes that nurse-led case management interventions delivered online or via telephone have superior effects on symptom burden and equivocal effects on self-management/behavioural outcomes compared with usual care. 40 44 There is, however, insufficient evidence of effect on HRQoL. During survivorship, the evidence for effectiveness of nurse-led case management is less clear. Two small pilot studies report superior intervention effects on symptom burden compared with usual care or control; however, there was no information provided on the control condition in one study. Moreover, the effects on HRQoL self-management/behavioural outcomes are conflicting and no study reported survival, satisfaction or health service/resource use and costs. This suggests that case management interventions are effective for alleviating symptom burden during treatment, but its effects during survivorship are less clear. Therefore, there is a need for well-powered, well-controlled trials evaluating all outcomes, particularly during survivorship.

There is consistent evidence from randomised trials that nurse-led surveillance interventions, whether with structured or patient-initiated contact, are equivocal to usual care for HRQoL, symptom burden and self-management/behavioural outcomes during survivorship and treatment. There is insufficient evidence of effect on survival outcomes, health service/resource use and cost, and perceived intervention benefits and patient satisfaction. This suggests that nurse-led follow-up care is as safe and effective as physician-led follow-up care, but future research should evaluate the effects of these interventions on survival and impacts of the interventions on health service or resource use and costs.

This was a comprehensive systematic review following a predefined, registered review protocol. We included high-level evidence from RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness of nursing interventions. We implemented a taxonomy of outcomes recommended by a systematic review of nurse-led interventions 15 and synthesised the interventions using well-established categorisation systems (The Omaha System) for interventions and problem domains. 16

There were some limitations to this review. We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature and while all efforts were made to identify relevant studies, it is possible that some were excluded due to the lack of adequate information about the interventionist. All included studies were at high risk of bias for at least one outcome. The heterogeneous nature of the included studies did not allow statistical pooling of data. Collating studies using the Omaha System categories may have oversimplified the intervention effects, particularly the case management and teaching, guidance and counselling interventions which were often complex. However, we included detailed information about the designs and interventions of each included study in our report. We only included publications in English and most included study interventions were conducted in the USA, thereby limiting the generalisability of our findings.

There is consistent evidence from randomised trials that nurse-led surveillance interventions are as safe and effective as physician-led care and the majority of RCTs indicate that nurse-led teaching, guidance and counselling and case management interventions are effective for alleviating symptom burden. Overall, there are a lack of studies evaluating intervention effects on survival outcomes, patient satisfaction and perceived intervention benefits and health service/resource use and costs. Future studies should evaluate the HRQoL and self-management/behavioural outcomes and consider using a well-designed attentional placebo control to blind participants for self-report outcomes. Such studies should consider the Medical Research Council (MRC) complex intervention framework to gain better insights into which mechanisms are effective, thus providing deeper insights into these interventions which would then facilitate replication.

- Cruickshank S ,

- Kennedy C ,

- Lockhart K , et al

- Liebert B ,

- White K , et al

- Claassen S , et al

- Moore A , et al

- National Breast Cancer Centre

- Maguire P ,

- Tait A , et al

- McArdle JM ,

- George WD ,

- McArdle CS , et al

- Baum M , et al

- Wilkinson S ,

- International Agency for Research on Cancer

- Charalambous A ,

- Campbell P , et al

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC)

- Shamseer L ,

- Clarke M , et al

- Bradford N , et al

- Sterne JAC ,

- Savović J ,

- Page MJ , et al

- Wengström Y ,

- Häggmark C ,

- Strander H , et al

- Nissen MJ ,

- Swenson KK , et al

- Nezu AM , et al

- Sandgren AK ,

- Hargraves M , et al

- Schofield P ,

- Weih L , et al

- Sjödén P-O ,

- Bergh J , et al

- Dorros SM , et al

- Meneses KD ,

- Loerzel VW , et al

- Sikorskii A ,

- Tamkus D , et al

- Fillion L ,

- Leblond F , et al

- Koinberg I-L ,

- Fridlund B ,

- Engholm G-B , et al

- Tysver-Robinson D ,

- Campbell M , et al

- Sheppard C ,

- Higgins B ,

- Wise M , et al

- Kimman ML ,

- Bloebaum MM ,

- Dirksen CD , et al

- Dirksen CD ,

- Voogd AC , et al

- Grunfeld E ,

- Julian JA ,

- Pond G , et al

- Debess J , et al

- Schjolberg TK ,

- Henriksen N , et al

- Børøsund E ,

- Cvancarova M ,

- Moore SM , et al

- Matthews EE ,

- Berger AM ,

- Schmiege SJ , et al

- Han K , et al

- Ching SSY ,

- Wong FKY , et al

- Heidrich SM ,

- Egan JJ , et al

- Lee HS , et al

- Freysteinson WM ,

- Deutsch AS ,

- Davin K , et al

- Dunn-Henriksen AK ,

- Kroman N , et al

- Kirshbaum MN ,

- Stephenson J , et al

- Donnan P , et al

- Koinberg I ,

- Engholm G-B ,

- Genell A , et al

- Brandberg Y ,

- Feldman I , et al

- Browall M ,

- Forsberg C ,

- Wengström Y

- Tan J-Y , et al

- de Graaf E ,

- Teunissen SCCM

- Langbecker DH ,

- Haggstrom D ,

- Han PKJ , et al

- Jassim GA ,

- Whitford DL ,

- Hickey A , et al

- Mustafa M ,

- Carson-Stevens A ,

- Gillespie D , et al

- Aycock DM ,

- Helvig A , et al

Contributors All authors planned the research. RC, JM, KE, KP, JT, MS and PY conceptualised the review and research questions. RC, LT and SM designed the protocol and conducted the research. SM conducted searches. SM, JK and LT screened and evaluated studies. LT extracted study data. All authors contributed to reporting the research. RC and LT synthesised study results and took lead on writing the manuscript and all authors discussed the results and provided critical feedback on the manuscript. RC is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding The McGrath Foundation provided funding for this project.

Competing interests This research was a collaboration between McGrath Foundation and Queensland University of Technology. RC received grant funding from McGrath Foundation to conduct this research. JM, KE, KP, MS and JT are employees of the McGrath Foundation but were not involved in the systematic review beyond scoping the research questions, interpreting the data synthesis and reviewing the manuscript.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE Advertiser retains sole responsibility for the content of this article

The new normal for breast cancer research

Produced by

One lost year of breast cancer research funding can amount to ten years of lost research advances. Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

Published November 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted just about every aspect of breast cancer care. Patients and doctors have been forced to adapt to the new normal, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF) is no different. Dorraya El-Ashry, the Chief Scientific Officer of BCRF, explains how the foundation has navigated the crisis and is committed to data sharing.

How has the pandemic aff ected the BCRF research community?

Breast cancer research faces a steep cut in funding. BCRF’s researchers depend on our support to make discoveries, mount clinical trials, and keep labs in full operation. If we fall short, the impact on breast cancer research will be profound.

When social distancing measures were at their height, many labs closed and clinical trials were placed on hold. The biggest danger is not what happened over the last few months — many researchers adapted and found new ways to continue. The real danger is if research funding is diminished, it will put a stop to the progress we’ve made in the last decades, essentially an increase in preventable deaths.

With science, you can’t just turn the tap off and then turn it back on. There’s loss of lab personnel, loss of research models, labs that may need to close and data that is lost because the experiments couldn’t be finished. The consequence of decreased funding is much more long term — one year of lost funding could result in 10 years of lost advances.

Dorraya El-Ashry, Chief Scientific Officer of the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Credit: Breast Cancer Research Foundation

After 30 years spent as a breast cancer research scientist, I had a lot of ideas for how to help steer this global, scientific endeavor to eradicate breast cancer. One area I had high hopes for was to increase investments in breast cancer disparities research. Prior to the pandemic, we were working towards that goal to secure expanded funding for this specific area of research. Now the field faces a future of diminished funding, and yet, it’s clear that this area of research is needed now more than ever as disparities in health outcomes has become a central issue in the social justice movement. My hope is that, as we come out of COVID-19 downturn, this becomes an area we can pursue with deeper investments.

What are some of your other research priorities?

There are two ends of the spectrum that we need to target: Finding curative treatments for patients living with breast cancer, and preventing breast cancer from happening in the first place. Certainly novel therapeutics and precision medicine are some of the most urgent areas—we need treatments that can prolong lives and effect cures for women with metastatic breast cancer today. And we have to be thinking about the ultimate end goal, which is to prevent breast cancer. In order to best target these two goals, we need to support an entire spectrum of research—from basic science studying the roots of the disease to clinical trials moving treatments from the lab to patients.

In 2019, BCRF partnered with Springer Nature to help make research datasets publicly accessible for papers published by npj Breast Cancer . Why undertake this pilot programme?

A key tenet of BCRF’s mission is to connect investigators around the world, and this partnership with Springer Nature is a critical tool in making that happen. We all know that submitting research results in scientific journals and presenting them at major conferences is what allows investigators to review and comment on the work of others, but what’s missing are the raw data. So, we wanted to facilitate data-sharing among researchers who publish in npj Breast Cancer by helping to make all their datasets available in an accessible way. This will help researchers validate published results and allow scientists to ask new questions, generate hypotheses, and query their data from and with these datasets.

How is BCRF diff erent from other funders of breast cancer science?

BCRF was founded by Evelyn Lauder and Larry Norton with a vision to provide the best minds in breast cancer research with the security and freedom to pursue novel ideas. Rather than funding research projects with proven outcomes, we invite investigators with demonstrated track records in the field to submit proposals —proposals that are innovative and hold the potential to advance the field in some way, but don’t require an established result at the outset. We are in the 27th year of funding breast cancer research in this way — now supporting the scientists that have been involved in every major breast cancer research breakthrough to date.

How can you tell?

In this past year, we initiated a process of impact reviews, starting with a group of 40 investigators who have had BCRF awards for many years. And by any number of measures — publication rates, citation rates, other grant funding generated from BCRF-supported work— the impact of their work has been extremely significant. The most significant measure: the impact on patient lives over the last three decades. Breast cancer mortality rates have declined by 40 percent in that time in the U.S. Early-stage breast cancers have a five-year survival rate of over 90 percent. Nonetheless we remain committed to the women and men that continue to be diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. And with estimates of a rise in advanced breast cancer cases as a result of delays in diagnosis and treatment during the pandemic, the research we fund today has the potential to save even more lives tomorrow.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

Enhancing pathological complete response prediction in breast cancer: the role of dynamic characterization of DCE-MRI and its association with tumor heterogeneity

- Xinyu Zhang 1 ,

- Xinzhi Teng 1 ,

- Jiang Zhang 1 ,

- Qingpei Lai 1 &

- Jing Cai 1 , 2

Breast Cancer Research volume 26 , Article number: 77 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

330 Accesses

Metrics details

Early prediction of pathological complete response (pCR) is important for deciding appropriate treatment strategies for patients. In this study, we aimed to quantify the dynamic characteristics of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images (DCE-MRI) and investigate its value to improve pCR prediction as well as its association with tumor heterogeneity in breast cancer patients.

The DCE-MRI, clinicopathologic record, and full transcriptomic data of 785 breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy were retrospectively included from a public dataset. Dynamic features of DCE-MRI were computed from extracted phase-varying radiomic feature series using 22 CAnonical Time-sereis CHaracteristics. Dynamic model and radiomic model were developed by logistic regression using dynamic features and traditional radiomic features respectively. Various combined models with clinical factors were also developed to find the optimal combination and the significance of each components was evaluated. All the models were evaluated in independent test set in terms of area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). To explore the potential underlying biological mechanisms, radiogenomic analysis was implemented on patient subgroups stratified by dynamic model to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and enriched pathways.

A 10-feature dynamic model and a 4-feature radiomic model were developed (AUC = 0.688, 95%CI: 0.635–0.741 and AUC = 0.650, 95%CI: 0.595–0.705) and tested (AUC = 0.686, 95%CI: 0.594–0.778 and AUC = 0.626, 95%CI: 0.529–0.722), with the dynamic model showing slightly higher AUC (train p = 0.181, test p = 0.222). The combined model of clinical, radiomic, and dynamic achieved the highest AUC in pCR prediction (train: 0.769, 95%CI: 0.722–0.816 and test: 0.762, 95%CI: 0.679–0.845). Compared with clinical-radiomic combined model (train AUC = 0.716, 95%CI: 0.665–0.767 and test AUC = 0.695, 95%CI: 0.656–0.714), adding the dynamic component brought significant improvement in model performance (train p < 0.001 and test p = 0.005). Radiogenomic analysis identified 297 DEGs, including CXCL9, CCL18, and HLA-DPB1 which are known to be associated with breast cancer prognosis or angiogenesis. Gene set enrichment analysis further revealed enrichment of gene ontology terms and pathways related to immune system.

Dynamic characteristics of DCE-MRI were quantified and used to develop dynamic model for improving pCR prediction in breast cancer patients. The dynamic model was associated with tumor heterogeniety in prognostic-related gene expression and immune-related pathways.

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignant in women. In 2020, there were around 2.3 million women newly diagnosed with and over 600,000 women died of breast cancer worldwide [ 1 ]. Recently, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) has become increasingly used in breast cancer systemic treatment. NAC was initially used in inoperable breast cancer to enable surgical resection, and expanded to other types of breast cancer for increasing the chance of breast conservation owing to its remarkable efficacy [ 2 ]. Current NAC treatment schemes are determined by hormone receptor (HR) status and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status as recommended by American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [ 3 ]. Pathological complete response (pCR), defined as no residual disease in breast and axillary region after NAC, is a validated prognostic factor to assess treatment response and associated with long-term outcome [ 4 ]. However, only 10-50% patients achieved pCR, varying according to their receptor subtypes [ 5 ]. Moreover, the assessment of pCR status is performed at surgery after completion of NAC, prior to which non-responders have suffered from the toxicity and side effects caused by NAC. Therefore, it is essential to identify patients who are likely to achieve pCR before NAC to avoid unnecessary complications and maximize potential benefits.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) is the clinical routine for breast cancer assessment. It has high sensitivity in diagnosis and treatment monitoring [ 6 , 7 ]. Through acquisition of sequential images before, during, and after the administration of contrast agent, DCE-MRI provides valuable information about tissue perfusion and contrast agent enhancement dynamics associated with tumor angiogenesis [ 8 ]. Radiomics extracts high-dimentional image features that are imperceptible to human eyes to non-invasively quantify tumor characteristics [ 9 ]. Radiomic analysis of breast DCE-MRI has been used for pCR prediction in many previous studies, most of which only used radiomic features from one or several phases while ignoring the dynamic information [ 10 , 11 ]. Recently, attempts have been made to leverage the dynamic information embedded in DCE-MRI for pCR prediction by combining radiomic features extracted from different DCE-MRI phases. For instance, Peng et al. calculated delta-features between two different phases for pCR prediction [ 12 ]; Li et al. employed simple statistical patterns of radiomic features extracted from different phases for pCR prediction and achieved better performance compared to single-phase features, demonstrating the value of multi-phase information [ 13 ]. In BMMR2 challenge, radiomic features from kinetic maps, such as peak enhancement maps and signal enhancement ratio maps, were used to predict pCR [ 14 ]. However, the entire time series of radiomic features has not been fully explored and may contain additional information for tumor characterization. On the other hand, feature-based representation of time series data like 22 CAnonical Time-series CHaracteristics (Catch22) can capture the dynamic properties of time series data and was used in various tasks [ 15 , 16 ]. Accordingly, there developed an assumption that the dynamics of radiomic feature series extracted by Catch22 can characterize the dynamic information in DCE-MRI and improve pCR prediction of breast cancer patients.

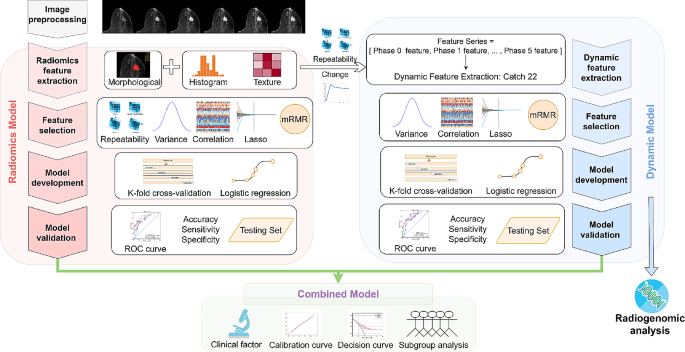

In this study, we aimed to systematically extract dynamic properties of radiomic feature series from DCE-MRI to improve treatment response prediction of breast cancer patients. To achieve this, a large number of dynamic features were extracted by Catch22 from DCE-MRI feature series, and a dynamic model was then built for pCR prediction. Various combinations of dynamic models and existing radiomic and clinical models were developed to find the optimal one as the final model. In addition, radiogenomic analysis of binarized dynamic model predictions was conducted to explore its association with tumor heterogeneity and biological process. Figure 1 shows the overall workflow of this study.

Workflow of the study. Firstly, the collected DCE-MR images were preprocessed by normalization and discretization. Radiomic features were extracted from multiple phases of DCE-MRI, while dynamic features were extracted from radiomic feature series. Feature selection, model development, and model validation were then conducted separately for radiomic model and dynamic model. Subsequently, combined models were developed by integrating radiomic, dynamic, and clinical information and their performance were evaluated. In addition, radiogenomic analysis was performed on dynamic model to investigate potential biological mechanisms

Materials and methods

Patient data.

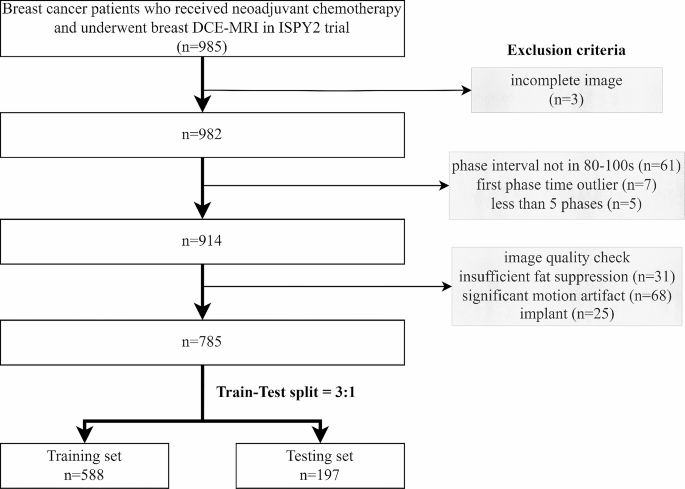

A total of 985 stage II/III locally advanced breast cancer patients enrolled in the multi-center I-SPY2 trial (clinical trial number: NCT01042379) during 2010 to 2016 were collected from the publicly available dataset on The Cancer Image Archive [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Institutional review board approval was waived due to the use of public data. The detailed descriptions of I-SPY2 trial have been reported by previous paper [ 20 ]. All the patients underwent MR examination and percutaneous biopsy before receiving NAC. After the completion of NAC, patients underwent surgical resection to assess residual disease. The exclusion criteria included: (1) incomplete image or clinicopathologic data; (2) deviations from the prescribed scanning protocol; (3) insufficient image quality.

Clinicopathologic data

Clinicopathologic data including HR, HER2, MammaPrint status (MP), pCR, and other patient characteristics was provided by the dataset. HR and HER2 were deternmined by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining or fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) of tissues obtained during pre-treatment biopsy. HR was determined as positive when ≥ 5% tumor staining for ER and/or PgR was seen. HER2 was determined as positive by IHC 3 + or FISH overexpression [ 21 ]. The surrogate of treatment response pCR was defined as no residual disease in breast and axillary lymph nodes after NAC and obtained by post-treatment surgery [ 22 ].

Imaging data and tumor segmentation

The scanning process of DCE-MRI can be found on TCIA website [ 17 , 18 ]. DCE-MRI scanning protocol details are provided in Supplementary Material Table S1 . The pre-contrast phase and five post-contrast phases were used for radiomic feature extraction and subsequent analysis.

The region of interest was segmented by functional tumor volume (FTV) included in the dataset. The calculation of FTV involved background filtering, estimating signal enhancement ratio, and applying a peak enhancement threshold in a manual-defined 3D bounding box [ 23 ].

Image preprocessing and feature extraction

Image normalization was performed across different DCE-MRI phases of the same patient to preserve the dynamic information. All the images were isotropically resampled to 1*1*1mm 3 , and discretized by a fixed bin width of 5. More details of image preprocessing can be found in Supplementary Material Figure S1 . Radiomic features were extracted from each phase of DCE-MRI using PyRadiomics package version 3.0.1 following the standardization and definitions in the image biomarker standadization initiative [ 24 , 25 ]. The extracted features included morphological features ( n = 14), first-order features ( n = 17), and texture features ( n = 79). The repeatability of radiomic features was evaluated by perturbation which involved random translation, rotation, and contour randomization of original masks [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Features with high-repeatabliity (intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC ≥ 0.9 [ 29 ]) were retained for better model repeatability. The fluctuation of radiomic features was measured by performing a single-sample t test on the variations between features from different phases. Radiomic feature series were constructed by concatenating the high-repeatable and phase-varying first-order and texture features. Dynamic features were extracted from radiomic feature series using the 22 CAnonical Time-series Characteristics (catch22) feature set, specifically designed for capturing the dynamic properties of time series data, such as distributions and outliers, linear and non-linear autocorrelation, and so on [ 30 ].

Model development and evaluation

The development of radiomic model and dynamic model followed the same process including feature selection and model building. The features with low variances were removed first to retain those providing more information. Then, features with significant correlations with pCR were identified by MannWhitney U test, where a p value smaller than 0.05 was defined as significant. LASSO was subsequently used to select the independently discriminative features. Finally, features were ranked by minimum redundancy and maximum relevance (mRMR) algorithm considering the relevance to pCR and redundancy at the same time [ 31 ]. Clinical factors that are commonly used in clinical decision making and have significant associations with pCR were identified and used in developing clinical model. Combined models were constructed using logistic regression with clinical factors, prediction score of the dynamic model, and prediction score of radiomic model as variables. Different combination strategies were adopted, including combining two of the three variables respectively, as well as the combination of all three together. The independence of the components in the combined models were examined by their coefficients and p values. All the models were developed using Logistic Regression with 10-fold cross-validation in training set and tested in independent testing set.

The pCR prediction performance of the candidate models was assessed by various metrics, including area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. AUCs were calculated by continuous prediction (the probability) and the other metrics were calculated by binary prediction (pCR or non-pCR) dichotomized by Youden index. An AUC typically ranges from 0 to 1 while AUC equal to one means a perfect descrimination ability. The optimal model was determined by the highest internal validation AUC in the training set. Heatmap was employed to visualize the relationships between different models and their association with clinical factors. SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), a method to interpret and explain the output of machine learning models, was employed to evaluate the importance of each component in the model with the highest AUC [ 32 ]. In our case, where the model output is the probability of achieving pCR, the SHAP values for each parameter ranges from − 1 to 1 and a larger absolute value means a higher importance for model output. Calibration curves and Brier scores were used to further evaluate the alignment between model-predicted probabilities and actual probabilities. Brier score measures the accuracy of probabilistic predictions and takes the value from 0 to 1, for which 0 means a perfect prediction. Decision curve analysis was performed to evaluate the clinical benefit obtained by the optimal model [ 33 ]. Besides, to further demonstrate the generalizability of the optimal model, its association with pCR in various pre-defined molecular subtypes, namely HR + HER2-, HR + HER2+, HR-HER2-, and HR-HER2+, and patients receiving different treatments were evaluated.

Radiogenomic analysis

To examine whether the dynamic model can reflect tumor heterogeneity and its association with gene expression, we collected paired total mRNA expression data from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [ 34 ]. Patients were divided into DYN + and DYN- groups according to the binary prediction of dynamic model. Student t test was performed to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two groups. An absolute log-2 fold change larger than 0.25 and a p value smaller than 0.05 were used as cutoff. Enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways were identified by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of DEGs [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. A p value smaller than 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) smaller than 0.25 were considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis and software

For statistical analysis, Chi-Square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables and MannWhitney U test was used for continuous variables. A two-tailed p-value smaller than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The 95% CIs for AUCs were calculated according to DeLong’s methods [ 40 ]. DeLong test was used to compare the AUCs of two independent models and likelihood ratio test was used to compare the model fit of nested models to demonstrate the improvements conferred by the additional factors in complex models. The statistical analysis was carried out on R4.2.2 [ 41 ] and Python3.7 [ 42 ]. Logistic regression was carried out by package scikit-learn 1.0.2 [ 43 ]. Radiogenomic analysis was conducted using packages scanpy 1.9.3 [ 44 ] and gseapy 1.1.0 [ 45 ].

Patient characteristics

A total of 785 patients with complete imaging data and clinicopathological record constituted the entire patient cohort in this study and were divided into training set and testing set with a ratio of 3:1 (Fig. 2 ). As shown in Table 1 , there is no significant difference in all of the patient characteristics between training set and testing set. The characteristics of pCR and non-pCR patients were tabulated in Supplementary Material Table S2 . Significant association with pCR was observed in treatment, HR, HER2, and MP, while the other characteristics were independent of pCR.

Patient cohort and train-test split

Feature repeatability and feature change

The summarized results of feature repeatability and feature variation are shown in Supplementary Material Figure S2 and Figure S3 . After removing the duplicate shape features and features with low repeatability, there were 480 radiomic features retained for each patient. For dynamic feature extraction, features repeatable in all the DCE-MRI phases and changing across different phases were retained. A total of 1232 dynamic features were extracted from 56 selected radiomic feature series for each patient and used in further analysis. An example of the dynamic feature is shown in Supplementary Material Table S3 .

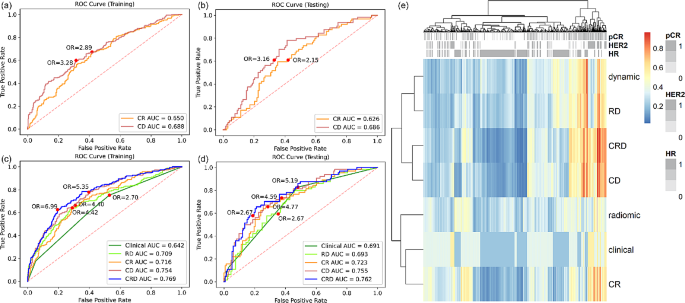

Different models in pCR prediction

A 10-feature dynamic model and a 4-feature radiomic model were developed separately (Supplementary Material Table S4 ). Dynamic model achieved higher AUC than radiomic model in both training set (0.688 vs. 0.650) and testing set (0.686 vs. 0.626) (Fig. 3 (a)(b)), but the difference was not statistically significant (p value = 0.181 and 0.222). Dynamic model also had better performance in terms of accuracy and specificity, while the sensitivity was the same as radiomic model (Table 2 ). The significance of each feature in dynamic model and radiomic model was evaluated by the odds ratio and tabulated in Supplementary Material Table S5 and S6 .

Among the clinicopathological variables provided in the dataset, treatment, HR, HER2, and MP were significantly associated with pCR (Supplementary Material Table S2 ). Since we intended to study biomarkers and MP requires expensive genomic test, only HR and HER2 were retained for further analysis. Table 3 summarized the metrics for pCR prediction performance of clinical model and combined models. Clinical-radiomic-dynamic (CRD) model achieved the highest training and testing AUC (Fig. 3 (c)(d)), accuracy, and specificity, while clinical model had the highest sensitivity among all the models. The clinical factors, the dynamic model, and the radiomic model demonstrated independent value in CRD model as indicated by their coefficients and p values (Supplementary Material Table S7 ). Compared with clinical-radiomic (CR) model, CRD model shown significant improvement in both training and testing performance, indicating the additive value of dynamic model. Figure 3 (e) shows the heatmap of the predicted probability by different models. Models containing dynamic features were clustered as similar models, showing the distinctive characteristic of dynamic features. The dynamic model was not associated with HR and HER2, demonstrating the independent value of dynamic model.

Reciever operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of dynamic model and radiomic model in ( a ) training set and ( b ) testing set. ROC analysis of clinical model, radiomic-dynamic (RD) model, clinical-radiomic (CR) model, clinical-dynamic (CD) model, and clinical-radiomic-dynamic (CRD) model in ( c ) training set and ( d ) testing set. ( e ) Heatmap of predicted probability by different models

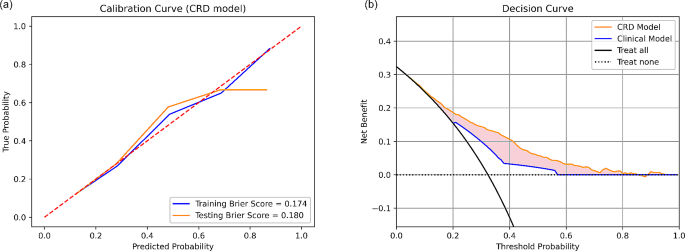

Evaluation of the optimal model

Overall, CRD model has the best performance in pCR prediction. The calibration curves of CRD model had Brier score of 0.174 and 0.180 in training and testing set respectively (Fig. 4 (a)), indicating well-alignment between predicted probablities and actual probabilities. The decision curve analysis of CRD model demonstrated its clinical usefulness by higher net benefit gain compared to clinical model and the other combined models (Fig. 4 (b)).

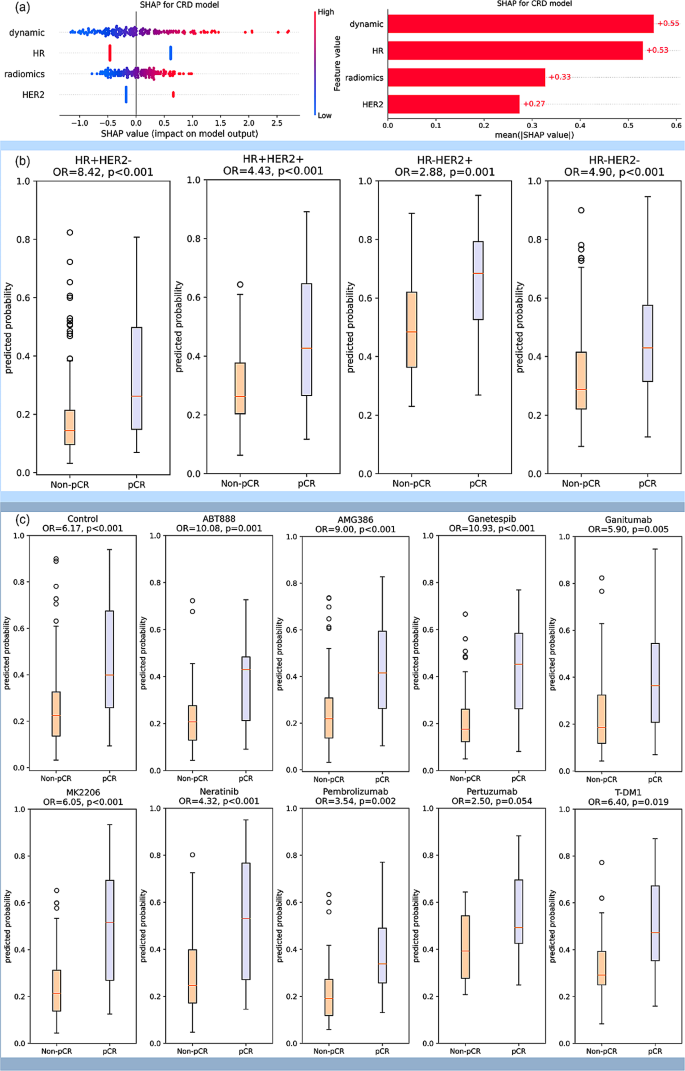

Calibration curve and decision curve analysis

The SHAP value analysis of CRD model shown high importance of dynamic model, which was comparable to HR. The importance of radiomic model and HER2 was a little bit lower, but still had significant effect on the model output (Fig. 5 (a)). The CRD model was also used in stratifying pCR and non-pCR patients under different pre-defined molecular subtypes. It shown a significant stratification ability in all the four molecular subtypes with odds ratio (OR) of 2.88–8.42. (Fig. 5 (b)). In the analysis of patients receiving different drugs, except for the marginally significant performance in Pertuzumab arm, CRD model shown significant association with pCR with OR of 2.88–10.93 in the other treatment arms (Fig. 5 (c)).

( a ) SHAP analysis for interpretable component importance of CRD model. The beaswarm plot shows how each variable influence model output on single data where one dot represents one patient (left). The mean absolute SHAP value reflects the global effect of each variable on model output (right). ( b ) Box plots showing the predictive ability of CRD model in patient subgroups of various molecular subtypes. The molecular subtypes were defined by the status of HR and HER2, namely HR + HER2-, HR + HER2+, HR-HER2+, and HR-HER2-. The box plots indicate that the CRD model yields significantly distinct prediction probabilities for patients with pCR and non-pCR in all the four molecular subtypes. ( c ) Box plots showing the predictive ability of CRD model in patients receiving various treatments. Patients received standard care (control) or standard care plus one trial agent (ABT888, AMG386, Ganetespib, Ganitumab, MK2206, Neratinib, Pembrolizumab, Pertuzumab, T-DM1) in the trial. The box plots suggest that CRD model demonstrates the capability to differentiate pCR and non-pCR patients across various treatment drugs in this trial, with the exception of a marginal significance observed in Pertuzumab. All the p values were obtained by student t test. OR: odds ratio

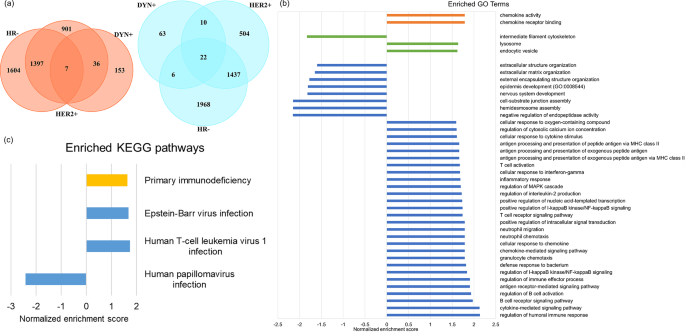

DEGs and enriched pathways

In DEG analysis, a total of 196 up-regulated genes and 101 down-regulated genes in DYN + group were identified. As compared with HR- group and HER2 + group, which also associate with better pCR outcome in ISPY2 trial, there are 7 common up-regulated genes and 22 common down-regulated genes (Fig. 6 (a)). In GSEA by GO terms, there are 36 biological processes, 3 cellular components, 2 molecular functions enriched in DYN+ (Fig. 6 (b)), many of which are associated with immune system. There are 4 enriched pathways in GSEA by KEGG, in which 3 pathways are related to viral disease and 1 pathway is related to immune disease (Fig. 6 (c)).

( a ) Up-regulated (left) and down-regulated (right) DEGs in DYN+, HR-, and HER2 + group. ( b ) Enriched GO terms in DYN + group. ( c ) Enriched KEGG pathways in DYN + group

While the dynamic information in DCE-MRI has shown potential in various clinical applications, the exploration of DCE-MRI-derived radiomic feature series has remained limited. This study systematically extracted dynamic features from DCE-MRI-derived radiomic feature series using feature-based time series analysis method and built dynamic model for pCR prediction. Adding dynamic model to exisitng clinical and radiomic model can improve pCR prediction. Radiogenomic analysis revealed correlations of dynamic model with some breast cancer prognosis-related genes and pathways, providing the potential biological explanations for the additive value.

The change in DCE-MR image appearances caused by the flow of contrast agent may contain valuable information for pCR prediction. Previous studies have employed delta features and statistical distributions to characterize the relevant dynamic information [ 12 , 13 ]. However, the former method may provide limited information by utilizing only two of multiple DCE-MR phases, while the latter method disregards the temporal information that is crucial for reflecting the directional flow of contrast agent. A recently published paper implemented several classical time series analysis algorithms in DCE-MRI-derived radiomic feature series and achieved an accuracy of 0.852 in breast cancer diagnosis, demonstrating the significance of serial information as well as the feasibility and efficacy of time series analysis [ 46 ]. In our study, we used radiomic features to comprehensively describe DCE-MR image appearance and adopted Catch22 to systematically analyze the dynamics of radiomic feature series. The Catch22 feature set takes into account both the temporal order and relative magnitude of series values. It has been successfully implemented in many time series analysis applications, such as breath signal and heart rate. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to apply a systematic feature-based time series analysis method to DCE-MRI for pCR prediction. Our results demonstrated the utility of the extracted dynamic features by showing a modestly higher AUC of dynamic model in comparison to the conventional radiomic model. Furthermore, the dynamic features provided additive value to the existing methods, as evidenced by a significantly improved model performance compared with both clinical model and CR model. Overall, we have demonstrated the feasibility and efficacy of extracting dynamic information through feature-based time series analysis and the potential of dynamic features in facilitating pCR prediction. Besides, our method offers the advantage of interpretability as Catch22 provides clear definition for each dynamic feature. And it is adaptable to different time series length which is frequently encountered in real-world clinical practice due to the variations of machines and scan settings. Our method demonstrates the potential to be implemented in real clinical practice, although further validation is required to confirm its performance in diverse settings.

Both single-modal and multi-modal models were developed in this study. While the imaging-based model and clinical model appeared to have similar performance, the combined models shown better performance than individual models. The CRD model achieved the highest AUC, which is significantly better than RD model and clinical model alone, indicating that imaging features and clinical factors may provide distinct and complementary information for pCR prediction. Subgroup analysis of the CRD model was conducted to further explore the effectiveness of CRD model under various conditions. Breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease characterized by various HR and HER2 status, resulting in four molecular subtypes. Our results on molecular subtype analysis resulted in varying effect size by OR ranging from 2.88 to 8.42, where a larger OR indicates a stronger predictive ability. While CRD model is significantly associated with pCR in all the molecular subtypes, our results suggested that CRD model has stronger predictive ability for patients of HR + HER2-. The CRD model was also evaluated by its effect for patients receiving different drugs, resulting in the largest OR in Ganetespib and marginally significant OR in Pertuzumab. This indicates the various predictive value of CRD model for various treatment drugs and assists the clinicians to decide applicable scenarios. In general, CRD model shown generalizability acorss various molecular subtypes and various treatment drugs. However, due to the nature of trial data, the patient numbers are small in each subgroups and further validation on larger cohort is required to confirm the results.