Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.

You may, of course, modify the template that is presented here. Your instructor might favour a somewhat different approach to literary analysis. Its essence, though, will be your understanding and interpretation of the theme of the poem, story, or play and the skill with which the author shapes the elements of literature—plot, character, form, diction, setting, point of view—to support the theme.

Academic Writing Tips : How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper. Authored by: eHow. Located at: https://youtu.be/8adKfLwIrVk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

BC Open Textbooks: English Literature Victorians and Moderns: https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/back-matter/appendix-5-writing-an-analysis-of-a-poem-story-and-play/

Literary Analysis

The challenges of writing about english literature.

Writing begins with the act of reading . While this statement is true for most college papers, strong English papers tend to be the product of highly attentive reading (and rereading). When your instructors ask you to do a “close reading,” they are asking you to read not only for content, but also for structures and patterns. When you perform a close reading, then, you observe how form and content interact. In some cases, form reinforces content: for example, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, where the speaker invites God’s “force” “to break, blow, burn and make [him] new.” Here, the stressed monosyllables of the verbs “break,” “blow” and “burn” evoke aurally the force that the speaker invites from God. In other cases, form raises questions about content: for example, a repeated denial of guilt will likely raise questions about the speaker’s professed innocence. When you close read, take an inductive approach. Start by observing particular details in the text, such as a repeated image or word, an unexpected development, or even a contradiction. Often, a detail–such as a repeated image–can help you to identify a question about the text that warrants further examination. So annotate details that strike you as you read. Some of those details will eventually help you to work towards a thesis. And don’t worry if a detail seems trivial. If you can make a case about how an apparently trivial detail reveals something significant about the text, then your paper will have a thought-provoking thesis to argue.

Common Types of English Papers Many assignments will ask you to analyze a single text. Others, however, will ask you to read two or more texts in relation to each other, or to consider a text in light of claims made by other scholars and critics. For most assignments, close reading will be central to your paper. While some assignment guidelines will suggest topics and spell out expectations in detail, others will offer little more than a page limit. Approaching the writing process in the absence of assigned topics can be daunting, but remember that you have resources: in section, you will probably have encountered some examples of close reading; in lecture, you will have encountered some of the course’s central questions and claims. The paper is a chance for you to extend a claim offered in lecture, or to analyze a passage neglected in lecture. In either case, your analysis should do more than recapitulate claims aired in lecture and section. Because different instructors have different goals for an assignment, you should always ask your professor or TF if you have questions. These general guidelines should apply in most cases:

- A close reading of a single text: Depending on the length of the text, you will need to be more or less selective about what you choose to consider. In the case of a sonnet, you will probably have enough room to analyze the text more thoroughly than you would in the case of a novel, for example, though even here you will probably not analyze every single detail. By contrast, in the case of a novel, you might analyze a repeated scene, image, or object (for example, scenes of train travel, images of decay, or objects such as or typewriters). Alternately, you might analyze a perplexing scene (such as a novel’s ending, albeit probably in relation to an earlier moment in the novel). But even when analyzing shorter works, you will need to be selective. Although you might notice numerous interesting details as you read, not all of those details will help you to organize a focused argument about the text. For example, if you are focusing on depictions of sensory experience in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” you probably do not need to analyze the image of a homeless Ruth in stanza 7, unless this image helps you to develop your case about sensory experience in the poem.

- A theoretically-informed close reading. In some courses, you will be asked to analyze a poem, a play, or a novel by using a critical theory (psychoanalytic, postcolonial, gender, etc). For example, you might use Kristeva’s theory of abjection to analyze mother-daughter relations in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. Critical theories provide focus for your analysis; if “abjection” is the guiding concept for your paper, you should focus on the scenes in the novel that are most relevant to the concept.

- A historically-informed close reading. In courses with a historicist orientation, you might use less self-consciously literary documents, such as newspapers or devotional manuals, to develop your analysis of a literary work. For example, to analyze how Robinson Crusoe makes sense of his island experiences, you might use Puritan tracts that narrate events in terms of how God organizes them. The tracts could help you to show not only how Robinson Crusoe draws on Puritan narrative conventions, but also—more significantly—how the novel revises those conventions.

- A comparison of two texts When analyzing two texts, you might look for unexpected contrasts between apparently similar texts, or unexpected similarities between apparently dissimilar texts, or for how one text revises or transforms the other. Keep in mind that not all of the similarities, differences, and transformations you identify will be relevant to an argument about the relationship between the two texts. As you work towards a thesis, you will need to decide which of those similarities, differences, or transformations to focus on. Moreover, unless instructed otherwise, you do not need to allot equal space to each text (unless this 50/50 allocation serves your thesis well, of course). Often you will find that one text helps to develop your analysis of another text. For example, you might analyze the transformation of Ariel’s song from The Tempest in T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land. Insofar as this analysis is interested in the afterlife of Ariel’s song in a later poem, you would likely allot more space to analyzing allusions to Ariel’s song in The Waste Land (after initially establishing the song’s significance in Shakespeare’s play, of course).

- A response paper A response paper is a great opportunity to practice your close reading skills without having to develop an entire argument. In most cases, a solid approach is to select a rich passage that rewards analysis (for example, one that depicts an important scene or a recurring image) and close read it. While response papers are a flexible genre, they are not invitations for impressionistic accounts of whether you liked the work or a particular character. Instead, you might use your close reading to raise a question about the text—to open up further investigation, rather than to supply a solution.

- A research paper. In most cases, you will receive guidance from the professor on the scope of the research paper. It is likely that you will be expected to consult sources other than the assigned readings. Hollis is your best bet for book titles, and the MLA bibliography (available through e-resources) for articles. When reading articles, make sure that they have been peer reviewed; you might also ask your TF to recommend reputable journals in the field.

Harvard College Writing Program: https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/files/hwp/files/bg_writing_english.pdf

In the same way that we talk with our friends about the latest episode of Game of Thrones or newest Marvel movie, scholars communicate their ideas and interpretations of literature through written literary analysis essays. Literary analysis essays make us better readers of literature.

Only through careful reading and well-argued analysis can we reach new understandings and interpretations of texts that are sometimes hundreds of years old. Literary analysis brings new meaning and can shed new light on texts. Building from careful reading and selecting a topic that you are genuinely interested in, your argument supports how you read and understand a text. Using examples from the text you are discussing in the form of textual evidence further supports your reading. Well-researched literary analysis also includes information about what other scholars have written about a specific text or topic.

Literary analysis helps us to refine our ideas, question what we think we know, and often generates new knowledge about literature. Literary analysis essays allow you to discuss your own interpretation of a given text through careful examination of the choices the original author made in the text.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What Is Literary Theory and Why Do We Need It?

Alice Lopez

Too Long; Didn’t Read (TL; DR)

Literary theory is a set of tools we use to analyze and find deeper meaning in the texts we read. Each different theory sheds light on a specific aspect of literature and written stories, which in turn provides us with a focus for interpretation of them. You also might have heard of this kind of theory referred to as critical theory. According to Jonathan Culler, a Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Cornell University, what we refer to as theory “includes works of anthropology, art history, film studies, gender studies, linguistics, philosophy, political theory, psychoanalysis, science studies, social and intellectual history, and sociology” (3-4). These works have had an impact beyond the field of study they came from because their ideas are widely applicable, including to literature.

When we read literature, we tend to make sense of what we read through our own experiences. In the introduction to the book Literary Theory: An Introduction , Terry Eagleton explains that: “[…] we always interpret literary works to some extent in the light of our own concerns” (10). So in order to deepen our personal interpretation of a text and to explore different viewpoints on it, we rely on literary theory.

Literary theory is a critical approach that you can choose to focus your textual analysis. In this context, the word “critical” does not mean engaging in scathing commentary on a text. Rather, a critical approach is one where you evaluate what you read and think about it from different perspectives. The word theory, in this instance, is not as abstract as it may sound – a theory is just an idea that was explored in depth in order to explain and interpret complex social systems or phenomena. A theory is not something that is simple or obvious, as it must be researched and fleshed out, and it usually has not been created specifically for literature analysis. Instead, a theory is made of “[…] writings from outside the field of literary studies [that] have been taken up by people in literary studies because their analyses of language, or mind, or history, or culture, offer new and persuasive accounts of textual and cultural matters” (Culler 3-4). These writings from different fields help us use specialized knowledge. Depending on what you are most interested in exploring within a text, you will choose a theory that can provide the most insight into this specific area.

These different theories are sometimes described as critical lenses. I like to think of a critical lens as a set of colored glasses: when wearing them, some colors will be made less visible, while others will stand out and become easier to focus on. For example, imagine wearing glasses with pink lenses. Everything you see will have a pink tint to it, which will alter the way you see colors: some colors will be accentuated, while others (like blue light) will be less noticeable. Wearing the colored lenses might also change your depth perception, or how well you see the contours of your environment. In short, changing the color of the lens on your glasses will allow you to see a different view than you would with the naked eye. Theory does similar for a text, helping us see it with a different view than we could while reading it alone. Some of the most common and widely-used literary theories are psychoanalytic theory, feminist theory, structuralism/ post-structuralism, and Marxist theory.

In his introduction to literary theory, Jonathan Culler shares the following list of characteristics of theory:

- Theory is interdisciplinary – discourse with effects outside an original discipline

- Theory is analytical and speculative – an attempt to work out what is involved in what we call sex or language or writing or meaning or the subject

- Theory is a critique of common sense, of concepts taken as natural

- Theory is reflexive, or thinking about thinking; enquiry into the categories we use in making sense of things, in literature and in other discursive practices (14-15)

Note that using theory requires using ideas from different fields of study (interdisciplinarity) to explore ideas that we might take for granted: we must examine our views and thoughts about certain topics. It also asks that we read the text closely and engage in critical thinking to break down the story’s topics (analysis). Finally, working with theory means that we propose potential ideas to answer the questions we ask of the text (speculation).

Why would we need the help of theoretical texts to find new or deeper meaning in what we read? To put it simply, literary theory helps us understand what lies beneath the storyline and gives us the words to describe this. For example, by providing us with definitions, descriptions, and explanations of abstract ideas, literary theory becomes a means to explore the psychology of the narrative’s characters, delve into the historical and sociopolitical context of the story, or articulate the structure of the text, among other things. With literary theory, we can question the assumptions, values, and ideologies underlying the narrative.

Here is a quick example. Let’s pretend you are reading Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein for a class. You know that this book is one of the first examples of science fiction and in the genre of Gothic horror. Interestingly, at a time when most books were written by well-to-do men, this ever-so-famous classic was authored by a young woman between the ages of 18 and 19. As you read, you cannot help but think that the main protagonist, Victor, has a bit of a strange relationship with Elizabeth and with his mother. You can describe what takes place in the book and express your opinion, but you begin asking questions that go beyond the plot of the text itself. Are the characters acting within the boundaries of expected gender roles? Is Victor’s view of women common for the time? Are author Mary Shelley’s own attitudes about gender showing through her characters?

In order to take your analysis further, you pick a theory to work with. In this case, you decide to use feminist theory to think about gender roles in the book. If instead you had an interest in the economic power structure depicted in this book, then you could choose to analyze the text using Marxist theory. This critical lens focuses on the struggle between different social classes. In this case, Victor Frankenstein and his monster could be viewed as belonging to two different classes (bourgeois and proletariat, respectively). When viewed in this way, the struggle between these two characters and its resolution take on a different meaning (Moretti).

If you would like to see some examples of how to analyze a text with the writings of a theorist, I recommend Jonathan Culler’s “Chapter 1: What is Theory” in Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction .

Over time, philosophers and theorists from different fields of study have explored and offered many ideas to think about and make sense of our world. As literature became a field of study in “the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,” there was an “emergence of literary studies in universities in Germany, France, England, America, and elsewhere, and that institutional development made necessary the development of methods of teaching that were associated with methods for conducting literary research” (Ryan 3). For example, in the mid- to late-20th century, a movement called Postmodernism (led, among others, by philosophers like Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes) discussed how society defines some people as “other,” creating categories such as deviant . What these authors wrote can help us understand some of the social mechanisms in place to categorize us, to make us conform, and to control us. Another example of theory is postcolonialism, a school of thought that considers the impact of colonialism and offers ways to resist and unsettle colonial power structures. One last example of a framework you could work with is disability studies, a branch of study analyzing and questioning definitions of disability and the role of society in controlling and erasing the existence of disabled bodies and minds.

In a Lumen Learning article titled “Introduction to Critical Theory,” William Stewart provides a chronological list of critical theories. Here is an abbreviated version of this list:

- Aestheticism – often associated with Romanticism, a philosophy defining aesthetic value as the primary goal in understanding literature. (This includes both literary critics who have tried to understand and/or identify aesthetic values, as well as those like Oscar Wilde who have stressed art for art’s sake.)

- Cultural studies – emphasizes the role of literature in everyday life

- Deconstruction – a strategy of “close” reading that elicits the ways that key terms and concepts may be paradoxical or self-undermining, rendering their meaning undecidable

- Gender studies (see also: feminist literary criticism) – emphasizes themes of gender relations

- Formalism – a school of literary criticism and literary theory having mainly to do with structural purposes of a particular text

- Marxism (see also: Marxist literary criticism) – emphasizes themes of class conflict

- New Criticism – looks at literary works on the basis of what is written, and not at the goals of the author or biographical issues

- New Historicism – examines works through their historical context(s) and seeks to understand cultural and intellectual history through literature

- Postcolonialism – focuses on the influences of colonialism in literature, especially regarding the historical conflict resulting from the exploitation of developing countries and indigenous peoples by Western nations

- Postmodernism – criticism of the conditions present in the twentieth century, often with concern for those viewed as social deviants or the Other

- Psychoanalysis (see also: psychoanalytic literary criticism) – explores the role of consciousnesses and the unconscious in literature including that of the author, reader, and characters in the text

- Queer theory – examines, questions, and criticizes the role of gender identity and sexuality in literature

When it comes to applying these theories to literature, we start with the idea that a text is the product of its time: a reflection of society at the time and/or an expression of the author’s beliefs and views. Literature opens a window through which we can view a moment in time. We then explore some aspects of the text that we read through the lens of a theory.

You might be reading this article to prepare for a specific assignment. It is common for literature courses to ask students to analyze, interpret, and discuss the texts they read. You will generally begin to think about how you should analyze a text when you are engaging in close reading: you will notice recurring themes, salient ideas, etc. Depending on what interests you, you can then determine which theory (or theories) you would like to use.

While reading your text, you want to take notes about thoughts you have. You can take these notes in any way that works best for you: paper notepad, voice recordings, digital notepad, etc. Make sure to note page numbers, save important quotes, and document other relevant information so that you are able to reference your findings later. As you do so, you will notice patterns, or parts of the story will stand out to you. Reflect on why you are interested in specific aspects of the story, as this will guide you in choosing which theoretical framework to use. Your professor will likely have introduced you to a few literary theories. Ask yourself which one seems the most relevant to what you would like to analyze.

If you are writing an essay that uses literary theory, it could have the following structure:

- Briefly introduce the text you will be analyzing:

It is important to provide your audience with some information about when the text was written, to share a few details about the author, and to summarize the main plot points of the story.

- Share and explain the theory you will be using:

Once you have situated the text, you will write a couple of paragraphs where you name the theory you will be using, cite its main authors, and explain its most important or relevant ideas.

- Make a broader argument about the text:

This is where the analysis starts in earnest. You will draw out ideas from the theory you chose and analyze specific portions of your text with them. You will quote the text to show your audience specific examples of your argument. It is in this section that you will provide depth to your argument. Coming back to the earlier example of Frankenstein , you might have decided to look at the text through the lens of feminist theory. You describe the gender roles portrayed in the story and provide examples from the book showing that women tend to be confined to the home while men work outside. You explore whether this was traditionally the case at the time the book was written and argue that the gender roles in the story reflect that of the era. Continuing to rely on feminist theory, you could then explore whether the gender roles described in the book empower or subjugate the female characters, and you make sure to provide examples from the text to support your argument.

- Provide a conclusion:

Reiterate the main points you have made in the body of your paper. A conclusion is also a great opportunity to open your findings to broader interpretations.

By now, you should feel clearer on what constitutes literary theory and how it is used in analysis. You should also have a sense of the different theories available and their respective emphases. Literary analysis is a fantastic way to be curious about what lies beneath a narrative and to unsettle assumptions in the text. It offers frameworks to think critically about larger social questions, many of which still affect us today. Such analyses even provide us with opportunities to reflect on our own perceptions and biases. As literary theory enhances our critical skills and allows us to engage in deeper inquiries, we develop an important skillset that we can rely on in situations beyond the classroom.

Works Cited

Culler, Jonathan D. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford University Press, 1997.

Eagleton, Terry . Literary Theory: An Introduction, University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Moretti, Franco. Signs Taken For Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms. Verso, 1997.

Rivkin, Julie, and Michael Ryan, editor . Literary Theory: An Anthology. 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2017.

Ryan, Michael, editor. Literary Theory: A Practical Introduction. 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017.

Stewart, William. “Introduction to Critical Theory.” Lumen , https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-herkimer-english2/chapter/introduction-to-critical-theory/ . Accessed 31 March 2024.

About the author

name: Alice Lopez

institution: Salt Lake Community College

Alice Lopez is a professor in the D epartment of English, Linguistics & Writing Studies at SLCC. She r eceived her BA in Writing Studies and MA in Rhetoric & Composition from the University of Utah. She is currently a student in the Rhetoric & Composition PhD program at the U. She is interested in multimodal composition and disability studies. In her free time, Alice can be found taking photos, playing with fountain pens or typewriters, and taking care of her Sphynx cats .

Literary Studies @ SLCC Copyright © 2023 by Alice Lopez is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing A Literary Analysis Essay

- Library Resources

- Books & EBooks

- What is an Literary Analysis?

- Literary Devices & Terms

- Creating a Thesis Statement This link opens in a new window

- Using quotes or evidence in your essay

- APA Format This link opens in a new window

- MLA Format This link opens in a new window

- OER Resources

- Copyright, Plagiarism, and Fair Use

Video Links

Elements of a short story, Part 1

YouTube video

Elements of a short story, Part 2

online tools

Collaborative Mind Mapping – collaborative brainstorming site

Sample Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Paper Format and Structure

Analyzing Literature and writing a Literary Analysis

Literary Analysis are written in the third person point of view in present tense. Do not use the words I or you in the essay. Your instructor may have you choose from a list of literary works read in class or you can choose your own. Follow the required formatting and instructions of your instructor.

Writing & Analyzing process

First step: Choose a literary work or text. Read & Re-Read the text or short story. Determine the key point or purpose of the literature

Step two: Analyze key elements of the literary work. Determine how they fit in with the author's purpose.

Step three: Put all information together. Determine how all elements fit together towards the main theme of the literary work.

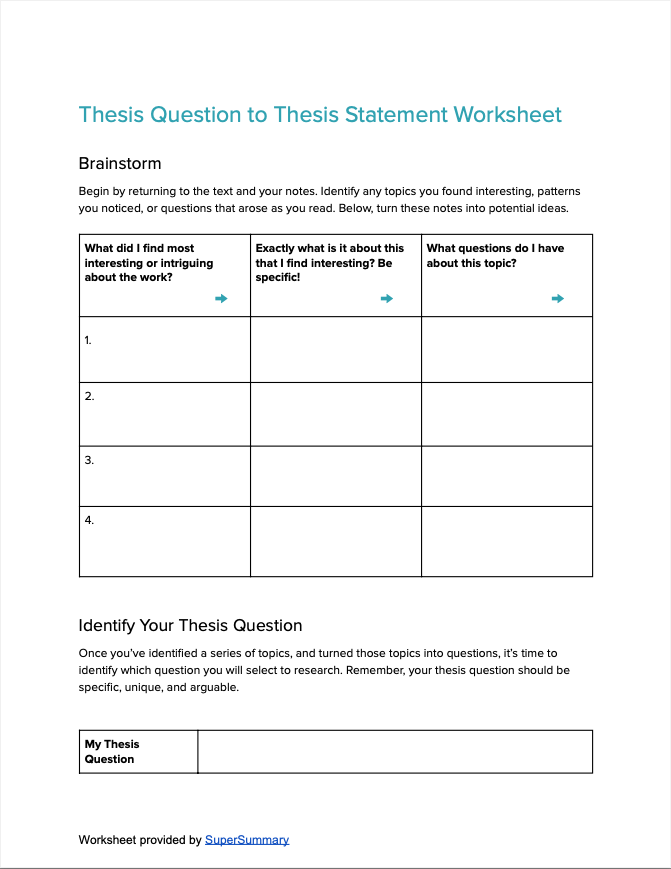

Step four: Brainstorm a list of potential topics. Create a thesis statement based on your analysis of the literary work.

Step five: search through the text or short story to find textual evidence to support your thesis. Gather information from different but relevant sources both from the text itself and other secondary sources to help to prove your point. All evidence found will be quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to help explain your argument to the reader.

Step six: Create and outline and begin the rough draft of your essay.

Step seven: revise and proofread. Write the final draft of essay

Step eight: include a reference or works cited page at the end of the essay and include in-text citations.

When analyzing a literary work pay close attention to the following:

Characters: A character is a person, animal, being, creature, or thing in a story.

- Protagonist : The main character of the story

- Antagonist : The villain of the story

- Love interest : the protagonist’s object of desire.

- Confidant : This type of character is the best friend or sidekick of the protagonist

- Foil – A foil is a character that has opposite character traits from another character and are meant to help highlight or bring out another’s positive or negative side.

- Flat – A flat character has one or two main traits, usually only all positive or negative.

- Dynamic character : A dynamic character is one who changes over the course of the story.

- Round character : These characters have many different traits, good and bad, making them more interesting.

- Static character : A static character does not noticeably change over the course of a story.

- Symbolic character : A symbolic character represents a concept or theme larger than themselves.

- Stock character : A stock character is an ordinary character with a fixed set of personality traits.

Setting: The setting is the period of time and geographic location in which a story takes place.

Plot: a literary term used to describe the events that make up a story

Theme: a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature.

Dialogue: any communication between two characters

Imagery: a literary device that refers to the use of figurative language to evoke a sensory experience or create a picture with words for a reader.

Figures of Speech: A word or phrase that is used in a non-literal way to create an effect.

Tone: A literary device that reflects the writer's attitude toward the subject matter or audience of a literary work.

rhyme or rhythm: Rhyme is a literary device, featured particularly in poetry, in which identical or similar concluding syllables in different words are repeated. Rhythm can be described as the beat and pace of a poem

Point of view: the narrative voice through which a story is told.

- Limited – the narrator sees only what’s in front of him/her, a spectator of events as they unfold and unable to read any other character’s mind.

- Omniscient – narrator sees all. He or she sees what each character is doing and can see into each character’s mind.

- Limited Omniscient – narrator can only see into one character’s mind. He/she might see other events happening, but only knows the reasons of one character’s actions in the story.

- First person: You see events based on the character telling the story

- Second person: The narrator is speaking to you as the audience

Symbolism: a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something else.

Irony: a literary device in which contradictory statements or situations reveal a reality that is different from what appears to be true.

Ask some of the following questions when analyzing literary work:

- Which literary devices were used by the author?

- How are the characters developed in the content?

- How does the setting fit in with the mood of the literary work?

- Does a change in the setting affect the mood, characters, or conflict?

- What point of view is the literary work written in and how does it effect the plot, characters, setting, and over all theme of the work?

- What is the over all tone of the literary work? How does the tone impact the author’s message?

- How are figures of speech such as similes, metaphors, and hyperboles used throughout the text?

- When was the text written? how does the text fit in with the time period?

Creating an Outline

A literary analysis essay outline is written in standard format: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. An outline will provide a definite structure for your essay.

I. Introduction: Title

A. a hook statement or sentence to draw in readers

B. Introduce your topic for the literary analysis.

- Include some background information that is relevant to the piece of literature you are aiming to analyze.

C. Thesis statement: what is your argument or claim for the literary work.

II. Body paragraph

A. first point for your analysis or evidence from thesis

B. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

III. second evidence from thesis

A. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

IV. third evidence from thesis

V. Conclusion

A. wrap up the essay

B. restate the argument and why its important

C. Don't add any new ideas or arguments

VI: Bibliography: Reference or works cited page

End each body paragraph in the essay with a transitional sentence.

Links & Resources

Literary Analysis Guide

Discusses how to analyze a passage of text to strengthen your discussion of the literature.

The Writing Center @ UNC-Chapel Hill

Excellent handouts and videos around key writing concepts. Entire section on Writing for Specific Fields, including Drama, Literature (Fiction), and more. Licensed under CC BY NC ND (Creative Commons - Attribution - NonCommercial - No Derivatives).

Creating Literary Analysis (Cordell and Pennington, 2012) – LibreTexts

Resources for Literary Analysis Writing

Some free resources on this site but some are subscription only

Students Teaching English Paper Strategies

The Internet Public Library: Literary Criticism

- << Previous: Literary Devices & Terms

- Next: Creating a Thesis Statement >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 1:22 PM

- URL: https://wiregrass.libguides.com/c.php?g=1191536

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

Step 6: Write an Outline

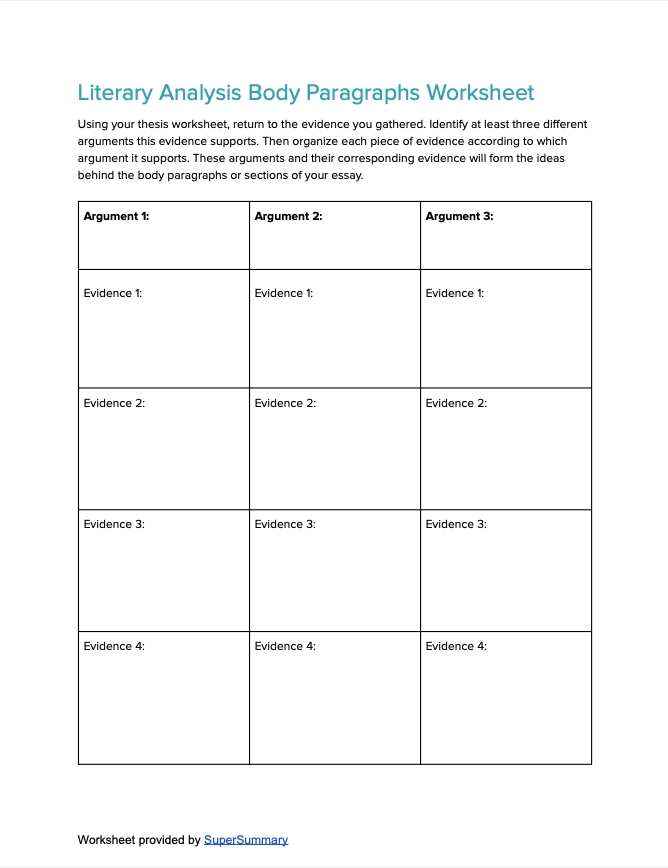

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

English and Comparative Literary Studies

Foundation module: critical theory - essay tips.

There are a number of ways to conceive of the Critical Theory essay. The simplest is to choose one of the set authors or topics and write on that with suggestions from the relevant tutor.

Slightly more ambitious is to compare and contrast theorists especially if there is a debate between them or one has criticised the other and there is an implicit or explicit dialogue between them. There may be topics where literary or other texts and readings of them have been deliberately built into the syllabus, e.g. readings by Baudelaire and Benjamin of Poe’s ‘The Man in the Crowd’ or Freud’s analyses of dreams and symptoms. Here you might give an account of the readings of these texts and how they are motivated by the theoretical premises and feed their own contributions to or disagreements with those readings into the discussion of the relevant theoretical frameworks. More ambitiously, and perhaps only to be attempted by the more theoretically confident students, is to select a literary or cultural text and generate a reading within a given theoretical framework or in relation to certain theoretical issues.

In both the last two options it must be stressed that this is a critical theory essay, not just an essay on a literary text, and the readings of the latter are there only to forward the discussion of the theoretical issues being addressed and should be organised to confirm, complicate or query the terms of the relevant theoretical issues and frameworks. We don’t want an essay that is mainly just a reading of poem x or novel y (you have other modules in which to do that).

The bottom line here is that students should be able to analyse the work of one of the theorists studied, to be able to explain their key terms, how they operate and the problems they are addressing. The more ambitious will want to play different theories off against each other and consider the limitations, blindspots or weak points of the theoretical frameworks being addressed. The starting point should be the texts read and discussed in the seminars, while the more confident will move a bit beyond them. However, the essay is only 6,000 words and that doesn’t leave much scope for too much ranging around. The essays should be focussed on particular theoretical essays and chapters and the structure of the argument as laid out there. You should think of yourself as giving an account of or arguing with particular theoretical texts and the arguments and terms deployed in them. Sweeping generalisations about Marxism or Psychoanalysis or Deconstruction should be avoided in favour of textually focussed argument.

Most importantly all students must have a discussion with the tutor responsible for each module and agree a topic and especially a title in advance so that we have a list of agreed titles (even if these may evolve in the writing process). This is an opportunity to get some guidance as to reading as well as to the formulation of the topic and title, and it should have happened by the end of the term in which the module is taken.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.5: Literary Theories

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 225951

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

WHAT ARE LITERARY THEORIES?

Literary theories are different perspectives, or angles, that we use to approach interpreting the literature we read. We can think of literary theories as “lenses” that allow us to “zoom in” on specific ideas, concerns, and issues, rather than on literary forms, conventions, and structures.

In short, literary theories are tools that help us make meaning of the literature we read. Understanding what these theories are and how they work provides us with tools that help us find meaning in what we have read.

WHY ARE THEY IMPORTANT?

Becoming familiar with literary theories allows us to formulate more focused, meaningful interpretations and ideas. Applying the basic, guiding principles of these theories helps us think critically about the literature and allows us to ask ourselves relevant, meaningful, and focused questions. Once we’ve asked these questions, we can then move on to answering them in a manner that allows us to “zoom in” on key issues and ideas.

Therefore, rather than looking at literature in a very general way, and rather than merely focusing on the technical aspects of a work, literary theories allow us to approach literature in a way that makes it easier for us to interpret and discover meaning than it would be without the guidance of the theories.

Although multiple literary theories exist, it is important for us to remember that interpretations of literature are the result of applying a combination of these theories.

HOW DO I USE THEM IN A PAPER?

Familiarize yourself with basic principles associated with the literary theories and how readers might apply them to the literature they read. Once you have carefully read the assigned poem, play, story, or novel, look over your notes and the annotations you have made in response to the work, and highlight the comments and ideas that stand out for you.

Once you’ve reviewed the ideas in your notes and annotations, go on to ask yourself the following questions:

- Which literary theories can I connect to the ideas and issues I’ve identified?

- How are my ideas reflected in the literary theories?

- Which of my ideas do I want to explore further in relation to those theories?

- How can I further apply the principles of the literary theory or theories to get more meaning from the text and delve deeper into the meaning/ideas I already have?

For more specific questions that might be useful in helping you apply literary theories, take a look at the “Questions to Consider” at the end of each literary theory description below.

THE LITERARY THEORIES: