The Art Assignment

Make a book with meat (or other atypical materials).

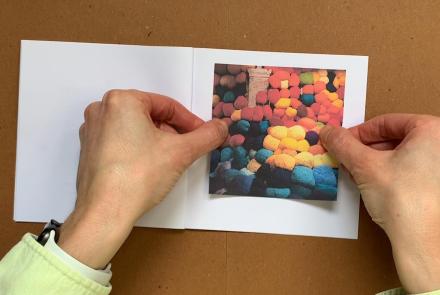

Artist and designer Ben Denzer shares an assignment to make an ATYPICAL BOOK. He’s made books from meat, toilet paper, ketchup packets, and lottery tickets, among much else. Your challenge: 1) Make a book that is atypical in terms of its form or material + 2) Share it on Instagram or Twitter with #youareanartist.

S6 E32 - 5m 28s

The Definition of Art

S6 E31 - 13m 4s

What is art? How do we define art? In this episode, we explore some of the many ways that artists and writers and thinkers have defined and understood this thing we call art.

Art That Was Never Finished

S6 E29 - 9m 32s

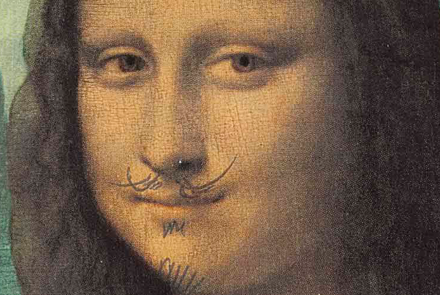

Artists have abandoned artworks for many reasons throughout history. Guest host John Green shares some of his favorite unfinished artworks and explains why they resonate with him so deeply. Featuring work by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Edgar Degas, Alice Neel, Kerry James Marshall, and very many presidential portraits.

Make a Cut-Out with Cécile McLorin Salvant

S6 E28 - 6m 50s

Cécile McLorin Salvant is a visual artist and Grammy Award-winning jazz singer, and she shares with us an art assignment on creating your own Theme and Variation Cut-Out.

Art Made in Adversity

S6 E27 - 6m 14s

Artist and educator Allison Smith shares her thoughts and library of books about art made in adverse circumstances. Featured are Vladimir Arkhipov's project Home-Made, archiving Russian artifacts made during Perestroika, and Trench Art, or art and objects made during armed conflict, highlighting works from Trench Art: An Illustrated History by Jane A Kimball.

Art That Brings Me Comfort

S6 E26 - 11m 38s

What art that brings you comfort right now? What art do you want to be thinking about? In this episode, we make a book of art by Alec Soth, Miyoko Ito, Giorgio Morandi, Vija Celmins, Sam Gilliam, Sheila Hicks, and Wayne Thiebaud.

Creativity is Overrated

S6 E25 - 9m 55s

You don't need to be creative or inspired to make art, but you may need the advice of artists, and perhaps a prompt!

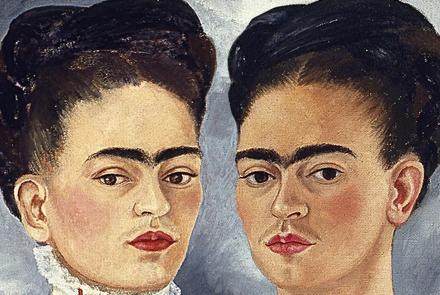

What This Painting Tells Us About Frida Kahlo

S6 E24 - 9m 26s

The artist Frida Kahlo is a larger-than-life icon, known for the masterful self-portraits she made during her turbulent life (1907 - 1954). We take a close look at her painting The Two Fridas (Las Dos Fridas), and consider what it tells us (and doesn't) about her as a person and her wider body of work.

What Makes a Masterpiece?

S6 E23 - 12m 35s

What do we mean when we call an artwork a MASTERPIECE? Who decides which art becomes one? And what artists make them?

The Case for Video Games

S6 E22 - 12m 45s

Video Games are fun, but are they art? Heck yes. We explore the history and present of video games and what sets them apart as a means of artistic expression.

Having a Coke with Frank O'Hara

S6 E17 - 15m 29s

Frank O'Hara is best known for his poetry, but in this Art Cooking we explore his life as a poet as well as an art curator at MoMA.

Art Therapize Yourself

S6 E21 - 12m 1s

What is Art Therapy? How can you use aspects of it in your next art encounter? We explore these questions at the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art with art therapist Lauren Daugherty.

WETA Passport

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.

- Get WETA Passport

Similar Shows

In Search of Resolution

GOSPEL Live! Presented by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Roadtrip Nation

Veterans Coming Home

Portrayal & Perception: African American Men & Boys

WETA Digital Extras

Honored to Serve

Armed in America: Faith & Guns

Smart Travels--Europe with Rudy Maxa

Get the latest from weta.

The Art Assignment

"The Art Assignment" is a weekly PBS Digital Studios production hosted by curator Sarah Green. We take you around the U.S. to meet working artists and solicit assignments from them that we can all complete.

Watch this show and many more anytime, anywhere on the free PBS App.

- The Art Assignment Season 6 f0

- The Art Assignment Season 5 f0

- The Art Assignment Season 4 f0

- The Art Assignment Season 3 f0

- The Art Assignment Season 2 f0

- The Art Assignment Season 1 f0

699,000 subscribers

About The Art Assignment

An educational video series that exposes you to alternative approaches to art making and the most innovative minds in art today..

The Art Assignment is an educational video series produced in partnership with PBS Digital Studios that focuses on the creative process and the act of making. The series is anchored by episodes that introduce you to emerging and established artists, each of whom devise and share an assignment that relates to their approach to art and serves as an open call for makers across the globe.

Not currently in production.

FEATURED VIDEOS

Behind the Banksy Stunt

What This Photo Doesn't Show

The Case for Abstraction | The Art Assignment | PBS Digital Studios

The Case for Impressionism

- MA Contemporary Art Theory

2023-24 The University of Edinburgh

Toggle navigation menu Menu

- / / / / What is the MA CAT?

- Semester 1 //// Themes in Contemporary Art

- Semester 1 //// Contemporary Art & Open Learning

- Semester 2 //// Curating

- Semester 2 / Contemporary Art + Anthropology

- Summer //// Contemporary Artistic Research Project

- Art & Open Learning Course

- Art + Anthropology Course

- Art in Partnership

- Artistic Research

- Collaborative Inquiry

- Curating Course

- Exhibitions

- Friday Talks

- Inhabiting Practice

- Learning Exchange

- Pickpocket Almanac

- Post-Studio

- Themes in Contemporary Art Course

- Uncategorised

- Contemporary Art & Open Learning //// Course Handbook //// Semester 1 //// ARTX10064 | 2023

Week 3 Class Assignment: Art Assignments & Learning Theories

Before we jump into learning theories, consider what you did when taking part in Build-a-Basho, Make Gold and Artists’ Toolkits at ESW.

All were open toolkits that took the form of an art assignment ; a set of simple instructions that you followed.

Collections of Art Assignments:

Draw it with your Eyes Closed

The art assignment is an approach that is widely practised in art education, specifically in its early foundational stages.

An art assignment is a teaching technique akin to an artists’ toolkit . While art assignment can be an artists’ toolkit , an art assignment tends not to include a comprehensive set of materials.

The art assignment largely leaves key questions of figuring out how and what to make to the participant. Moreover, where a toolkit suggests a “goal” – that is something that will be learned, or accomplished – an art assignment may not have a “goal” (either impliticitly or explicitly).

The book Draw it with your Eyes Closed (link) delves into the art of the art assignment, engaging artists to discuss art assignments that they were set and that they might set themselves.

Not all contributors are fans of the assignment format – but, on the whole, the art assignment is something they have all experienced as part of their art education.

You can read some of the assignments here:

https://drawitwithyoureyesclosed.com/ (link)

Here is a particularly meta art assignment from Draw it with your Eyes Closed to start with (you can follow this if you want, but reading it will suffice):

JACKIE BROOKNER–RULES ASSIGNMENT

Of course we know artists have a kind of congenital allergy to rules, especially somebody else’s rules. We like to make our own rules. Very freeing, right? Well, that’s not the whole story. Let’s take a look at the rules you are following, especially ones living below the threshold of consciousness. Make a list of these rules, right now. Which of them that you think are your rules, are really rules you’ve inherited, been taught, learned are the cool rules? Are they serving you, or trapping you?

As you work throughout this next week, try to hear the rules whispering to you. Keep a running list, and add to it every time you hear another one. Don’t read any further until you’ve done #1.

OK, you cheated, because it was my rule. Now, what kind of rules did you come up with? Are they the easy formal ones about choices of materials, how long or short the piece should be, or what to wear? Try again, and listen for the harder ones: the conceptual limits you put on your work, the kind of work you let yourself do, or not do. Are there whole parts of your being you put in a separate compartment and don’t even consider bringing into your work? Whole enthusiasms you haven’t let yourself imagine as part of your work? Embarrassments, naiveties, intelligences you leave out?

Now, this week do whatever you have to do to break your own rules. The hardest ones first.

https://drawitwithyoureyesclosed.com/post/67290458311/jackie-brooknerrules-assignment

The Art Assignment – Sarah Ulrist Green

If you haven’t had an art education, where else might you encounter art assignments?

Increasingly, art assignments can be found online:

For example, The Art Assignment is an OER website and PBS channel, hosted by curator Sarah Ulrist Green, that hosts assignments written and presented by different artists:

https://www.theartassignment.com/assignments-landing (link)

https://www.pbs.org/show/art-assignment/ (link)

https://www.youtube.com/user/theartassignment (link)

Sarah Green’s show is primarily a way of exploring art history as practicum : working directly with materials and making processes that artists have engaged with in different historical periods. This has long been an important project within art history as a discipline, especially within the curatorial sector which has a particular investment in haptic, or ‘hands-on’) research methods (because curators tend to work directly with objects).

Green’s Public Broadcasting Service approach is also her way of fulfilling the public mission of the museum as an educational institution.

Green also enlists contemporary artists to establish their own assignments. This helps her audience to engage with emerging art on material and haptic terms. Herein, Green is initiating an experiential learning process.

https://external-content.duckduckgo.com/iu/?u=https%3A%2F%2Fi.pinimg.com%2Foriginals%2Fb0%2Fd6%2F80%2Fb0d6806a446ab09ccf7392178df33738.jpg&f=1&nofb=1 (link)

The assignments in Green’s PBS show are often simple to follow and require little expertise, skill or specialist equipment. Each assignment engages the participant in the weltanschauung of the artist that has set the assignment. Taking part in each assignment can offer a microcosmic insight into the artists’ macro-view of art and their environment.

Learning to Love you More – Harrell Fletcher & Miranda July

The Art Assignment follows a model established by the artists Harrell Fletcher and Miranda July in the earlier days of the web:

http://learningtoloveyoumore.com/

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2p4q0u

The call-response format of Learning to Love you More (2002–2009) is, in essence, the challenge of the art assignment. The assignment establishes a set of simple parameters that set out a field within which to play. While designing the parameters in the form of the assignment is an art in itself, it’s the mere presence of the enabling constraints that matter.

Art Assign Bot – twitter @artassignbot

For example, the bot https://twitter.com/artassignbot randomly generates art assignments that have both commands and constraints. While some might prove impossible to follow, most of @artassignbot’s tweets can be completed (e.g. Build a flipbook about burglaries, due on Wed, Mar 14. )

The considered learning design we’d expect from Green’s The Learning Assignment or Learning to Love you More isn’t present since the bot is an algorithm rather than a more sophisticated AI. Nevertheless, if more than one participant were to follow the prompts of @artassignbot they could establish a paragogics by posting and comparing their responses.

Enabling Constraints

The emphasis on establishing enabling constraints dates back to the late 1950s when art education started to be influenced by systems theory. In England, the dominant art school models at the end of the 1950s were the ‘South Kensington System’ derived from the Royal College of Art, London and the ‘General Design’ method derived from the Bauhaus, Dessau. There are two particularly (infamous) art programmes in England during that period, both of which made extensive use of art assignments:

Here is Ascott discussing Groundcourse at Shift/Work, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

Groundcourse ( Roy Ascott, Ealing Art School / Ipswich Art School, 1961-Present)

As you will see from this video, the team-taught Groundcourse was largely based on second order Cybernetics .

https://external-content.duckduckgo.com/iu/?u=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.artrabbit.com%2Fevents%2Fthe-locked-room-four-years-that-shook-art-education-19691973-book-launch%2Fimages%2FDhNBizj1FSAZ%2F550x730%2Fcover.jpg&f=1&nofb=1 (link)

Sloan, Kate Art, Cybernetics, and Pedagogy in Post-War Britain: Roy Ascott’s Groundcours e

Emily Pethick, Degree Zero https://www.frieze.com/article/degree-zero

Sculpture Course ‘A’ (St. Martin’s School of Art, 1969)

Since it was devised by a team, the accounts of what Sculpture Course A did differ dramatically:

Please read:

Heston Westley’s “The Year of the Locked Room: St. Martin’s School of Art” in TATE Papers https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-9-spring-2007/year-locked-room (link)

Kardia, P., 2010. From floor to sky : the experience of the art school studio , London [England]: A & C Black.

The Locked Room, Four Years that Shook Art Education , 1969-1973

Post-studio (John Baldessari 1970, CalArts, California, USA)

In North America, we can see a similar turn to the assignment in seminal programmes which began at the turn of the 1970s:

https://eastofborneo.org/articles/a-situation-where-art-might-happen-john-baldessari-on-calarts/

You can read some of John Baldessari’s assignments here:

https://painterskeys.com/fourteen-assignments-john-baldessari/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gO49s8WlUis&feature=youtu.be

John Baldessari I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art Art assignment for NSCAD students, https://smarthistory.org/john-baldessari-i-will-not-make-any-more-boring-art/ 1971, 31:17 min, b&w, sound

Richard Hertz on the CalArts Mafia (graduates of Post Studio Program). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHL_dA_K9Ig (link)

Feminist Art Program (Rita Yokoi, Miriam Schapiro, et al 1970 Frenso State Universit; Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro 1971-1981 CalArts, California, USA)

Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro ‘Womanhouse’ Catalogue cover, 1972 CalArts, California, USA

Further reading:

Verena Kittel – Let the Subaltern Speak: The Archive of the Feminist Art Program describes how the FAP used used assignments “aimed at helping its students to develop self-assurance, gain strength, be ambitious, and pursue and achieve their own goals.”

Suzanne Lacy on the Feminist Art Program at Frenso State and CalArts

NSCAD (Garry Neill Kennedy, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada)

Page from Kennedy, G.N., 2012. The last art college : Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968-1978, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Post-studio at CalArts was closely intertwined with NSCAD: – Nova Scotia College of Art & Design

Leonard, C., Siegelaub, S. & Halifax Conference, 2019. The Halifax Conference : NSCAD, 6152 Coburg Road, Halifax, Canada, Oct. 5 & 6, 1970, Los Angeles: New Documents.

Kennedy, G.N., 2012. The last art college : Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968-1978, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

4-D Sculpture (Paul Thek, Cooper Union, NYC, 1978-1981)

Paul Thek with his installation The Tomb: Death of a Hippie (1967)

Paul Thek is another good example of an artist-educator who made extensive use of assignments:

Paul Thek’s Teaching Notes

📎 Chris Krauss on Thek’s Teaching Notes

https://cooper.edu/about/news/paul-thek-modern-institute

If you investigate art assignments a little more online, you will find many examples.

For now, we will turn to learning theory. we will return to this at the end of this learning module..

What are Learning Theories and how might you start to navigate them? (Three Learning Theories)

(Three) Learning Theories

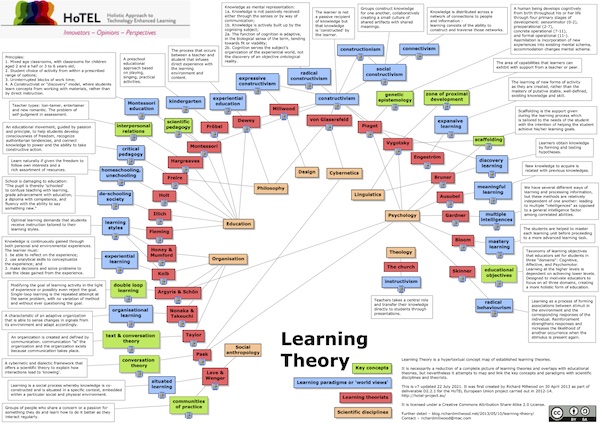

HoTEL Learning Theory Map by Richard Millwood http://blog.richardmillwood.net/2013/05/10/learning-theory

Please Download: https://blog.richardmillwood.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Learning-Theory.pdf

Interactive Version of Richard Millwood’s HoTEL Learning Theory Map http://cmapspublic3.ihmc.us/rid=1LNV3H2J9-HWSVMQ-13LH/Learning Theory.cmap

As you can see from the HoTEL Learning Theory Map , there are many learning theories that we could introduce here and study! (If you click on the interactive link above, you can find out more….) We just don’t have the time to take all of this in, so I will run through just three learning theories. I’ve chosen them because they are either practiced already in art educational (albeit opaquely) or because they have particular relevance to art education in the 21st century.

I will stick with the three key examples referenced above. Remember that these are just examples, there are many many more examples of assignment-based art education that we could draw on!

- https://www.mybrainisopen.net/learning-theories-and-learning-design/

- Donald Clark’s 100 learning theorists

- https://www.learning-theories.com/

We will try to learn a little about learning theory by applying it to the model of the art assignment as a typical example of a teaching method used in art education.

Learning theory example #1, social constructivism.

In learning theory, the focus on how knowledge is constructed through forms of social interaction is called social constructivism . This approach is very common in Artistic Learning. It is mainly attributed to the Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and further back to the ‘first wave’ behavioral constructivism of Jean Piaget (1896–1980).

In Mind in Society: The development of Higher Psychological Processes (1925-35) – Vygotsky rejected Piaget’s contention that learning can be separated from its social context. Vygotsky, rather, argued that learning was the active collaborative process wherein students engage with a community of learners.

Social Constructivism and Artistic Learning

Social Constructivism is omnipresent in Artistic Learning in ways that are often ‘unconscious’. For example, the commonly held assumption that art students should be gradually relieved of structure (in the form of mentoring or art assignments) and encouraged to pursue their own learning paths is one rooted in Vygotsky’s concept of ‘scaffolding’. The scaffolding support is gradually removed as learning is internalised, leaving students to stand on their own.

Social Constructivists see learning as experiential : students learn by doing. We bring prior experience to bear on new experiences and attempt to reconcile the two. In this, Social Constructivists draw a great deal of sustenance from the work of the American philosopher John Dewey (1859-1952), particularly his book Experience and Education (1938). Dewey’s experiential learning theories have had profound influence on art education in the USA, and his emphasis on school as an institution for social reform spearheads a great deal of North American Social Practice .

See: Helguera, Pablo (2012). Education for Socially Engaged Art . New York: Jorge Pinto Books

From a Social Constructivist perspective, art-learning projects such as Fletcher and July’s Learning to Love You More , The Art Assignment and @artassignbot would be seen as forms of scaffolding that encourage very particular forms of ‘subjectivisation’. Such projects scaffold the process of becoming-artist in particular ways that we can trace and subject to deconstructive scrutiny. Learning to Love You More is also overtly experiential ; we are frequently asked to draw upon our previous experience in order to complete its assignments.

Social Constructivists constantly seek to investigate and challenge how we construct (scaffold) learning through our social interactions and our social experiences. Thus, the ways we design learning by devising and supporting forms of social interaction are absolutely pivotal in how we develop personhood (the ‘self’). While this scaffolding can be carefully designed/structured, the studio itself is often presented as the crucible wherein social interaction imparts artistic knowledge. The studio (or at least so it is often claimed) is a panacea for experiential learning.

Note that the emphasis in this model of Artistic Learning is on the support given to individual learners and upon their development as individuals . You can see this rhetoric everywhere in art education, with its emphasis on finding your own disctinctive ‘vision’ and becoming creatively ‘whole’ and its relative lack of interest in collective practice or collective research. It is also a view echoed more widely in education now, which equally focuses on personal development and learner-centred approaches.

Learning Theory Example #2

Critical pedagogy.

In learning theory, critical pedagogy can be seen to shift the focus on how knowledge is constructed through forms of social interaction towards thinking about how knowledge is constructed by society as a whole . More broadly, within the social sciences, this is called social constructionism .

See: Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckman, The Social Construction of Reality, 1966

Where Construct ivists , such Piaget and Vygotsky, hold that individuals construct knowledge within their own minds (‘mental models’), social constructi onists see knowledge as constructed by groups, via social discourse.

In the late 1960s, Critical Pedagogues such as Paulo Freire and Henry Giroux sought to surface and deconstruct the buried politics of educational institutions (the ‘hidden curriculum’) in order that they might become proponents of radical social change.

Critical Pedagogy and Artistic Learning

Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Friere 1968)

The Social Constructionist perspective – that culture is made not given – is a dominant paradigm within contemporary art. Since culture is made, it can be unmade and reshaped in different forms. We can see this perspective activated in innumerable (postmodern) artworks that take, as their starting point, the view that culture is socially constructs rather than represents ‘reality’. This stands in stark contrast to the essentialising views that are still common vis a vis art education: e.g. that talent is ‘innate’, that great artists are born great artists, that art cannot be taught. While essentialising views still exist in art education, they are widely regarded as belonging with the domain of the ‘amateur’ artist.

Critical Pedagogy is a popular topic within the educational turn in art practice and curating. Friere’s ideas in particular have witnessed a renaissance in the 21st century. A Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Friere 1968) is less visible within institutional art education, much of which has not been reformed in any significant way since the late ’60s. Where it did surface, Critical Pedagogy has

involved faculty and students attempting to radically reform their institution.

For example, the student occupation of Hornsey

Students and staff of Hornsey College of Art (1969). The Hornsey Affair. Penguin Education. ISBN 9780140800968

Art School, North London in May-July 1968 was one occasion when Freirean Critical Pedagogy was applied as students took over the administration of their art school. While the occupation of Hornsey ended the educational experiment, its reverberations can still be felt. See: Tickner, L., 2008. Hornsey 1968 : the art school revolution, London: Frances Lincoln. This project http://radical-pedagogies.com/ led by Beatriz Colomina, maps out radical pedagogy in Architectural education in the latter half of the 20th century.

The Feminist Art Program , equally, actively deconstructed patriarchal art education and replaced it with a radically new feminist approach, encouraging critical thinking that brought about social change. An early assignment that foregrounded critical pedagogic dissent involved faculty and students of the Fresno Feminist Art Program renovating their own off-campus studio.

More broadly, on a practical level, there are many art programmes that actively engage with the theory that knowledge is socially constructed broadly within society as a whole. For example, some faculty and students on the Feminist Art Program focused on investigating gender as a social construction while other feminists opposed this proposition. The debate regarding social constructionism continues within, and between, feminism, queer and trans politics.

Learning Theory Example #3

Connectivism.

In learning theory, the focus on building P2P networks is called connectivism . This approach is attributed to George Siemens and Stephen Downes. In this video George Siemens explains what Connectivism is from his perspective:

If you want to dig a bit deeper still, reading Siemens’ Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age (2005)

For now, let’s highlight three of Siemen’s’ Principles of Connectivism from this paper:

Siemens_2005_Connectivism_A_learning_theory_for_the_digital_age.pdf (link)

- Learning and knowledge rests in diversity of opinions.

- Learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources.

- Learning may reside in non-human appliances.

- Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known

- Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning.

- Ability to see connections between fields, ideas, and concepts is a core skill.

- Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent of all connectivist learning activities.

- Decision-making is itself a learning process.

- Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality.

- While there is a right answer now, it may be wrong tomorrow due to alterations in the information climate affecting the decision.

‘Connections’ vs. ‘Content’

Siemens & Downes stress the importance of connections over the content that they connect. In this, they follow systems theory in focusing on ‘ties’ (connections) over ‘nodes’ (the elements that ties connect together.)

Is Connectivism only Digital Learning?

Connectivists focus on how learning is advanced through forging new connections between existing bodies of knowledge. These connections are always being made but are accelerated by the advent of online (digital) learning in the form of what Siemens calls MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses, coined by Dave Cormier, 2008). As such, Connectivism is often read as a theory of online learning, accessible only to learners who can easily access the web.

Connectivism and Artistic Learning

Here’s quick search you can conduct to see what’s available for art and designers:

https://www.my-mooc.com/en/categorie/visual-arts has just 43 MOOCs on art and design.

Are any of them able to support practice?

On a practical level, you may find that there are very few MOOCs that support art or design learning.

In contrast, there are many MOOCs on art and design histories.

This might tell us that, as yet, MOOCs are not where we will find connectivist ideas in art education. We need to look elsewhere, namely towards the educational turn in curating and artistic practice. For example, let’s return to example drawn from Greene’s The Art Assignment :

https://www.theartassignment.com/assignments//customize-it

Brian McCutcheon’s assignment is hosted by The Art Assignment , which acts as its Learning Management System (LMS). Note that submissions are to any social media platform we choose, so long as we adopt the hashtag of #theartassignment. The # thus becomes a ‘distributed’ LMS that fosters connections .

From a Connectivist perspective, art-learning projects such as Learning to Love You More , The Art Assignment and @artassignbot could be seen as Learning Management Systems (LMS) that share an ability to connect large numbers of participants (‘massive’) through establishing common learning endeavors.

For example, by encouraging Learning to Love You More participants to post their assignments, the projects’ Learning Management System (the website) was able to aggregate contributions and enable participants to compare and contrast their learning. The art assignments on the LMS aren’t what’s important, nor are the completed assignments submitted to it. What matters that the project encourages participants start to engage with each other.

“We say explicitly that the content is the “MacGuffin” – it is the thing that gets people together, gets them talking, gets them thinking in new ways.” (Downes 2012).

As Sarah Green might put it, the art assignment is the MacGuffin that ‘sparks creation’. While an outcomes-based learning approach might want to focus on how Learning to Love You More was the catalyst for numerous submissions/works of art, the Connectivist would say that what actually matters is that connecting with other learners via the project. @artassignbot generates connections capable of sparking off learning.

Learning without Teachers?

Downes is clear about the broader agenda for Connectivism and its role in the Open Educational movement:

“It’s about reducing and eventually eliminating the learned dependence on the expert and the elite – not as a celebration of anti-intellectualism, but as a result of widespread and equitable access to expertise.”

In terms of the three examples given here, what ‘expertise’ is being accessed when people participate in art assignments that do not have an obvious or intentional (human) author (e.g. @artassignbot).

Siemen’s Principles state that Learning may reside in non-human appliances. How is this so, how it possible to learn in without experts/teachers?

Connectivism’s teacherless education has some parallels with Friere’s teacher-student continuum – a flattening of the master>apprentice hierarchy prevalent within what Friere called the ‘banking view’ of education. Where Critical Pedagogy’s teacher-student continuum questions and challenges domination, Connectivism moves to eliminate teachers altogether so that everyone is a learner. Would this challenge domination, or would it lead to new forms of information domination? Might applying Critical Pedagogy to Connectivism reveal how it is ideological, dominated by a technocratic worldview?

Week 3 Class Assignment

Please turn-in the class assignment to learn by tuesday 10th october, 9:00am..

Instructions on how to complete this assignment are all in Learn.

Please check Learn for details and ensure that you turn-in your work there.

Open Learning Course Handbook

Art Assignments & Learning Theories Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Neil Mulholland 2023

Report this page

To report inappropriate content on this page, please use the form below. Upon receiving your report, we will be in touch as per the Take Down Policy of the service.

Please note that personal data collected through this form is used and stored for the purposes of processing this report and communication with you.

If you are unable to report a concern about content via this form please contact the Service Owner .

The Art Assignment

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

How Art and Science Intersect

On this rebroadcast of The Pulse - We often think of art and science as existing in different — even opposite — spheres. One revolves around creativity and imagination; the other around observable facts and data — and never the twain shall meet. But really, art and science aren't as far apart as we might think. For centuries, artists have drawn on the natural sciences, and the wonders of the natural world, as inspiration for some of our most celebrated works. On this episode, we explore the hidden architecture of science that often underlies music, literature, and more. We talk with a mathematician who makes the case that math is key to appreciating literature on a whole new level; a pianist who reveals how the natural world inspired some of classical music's most iconic composers; and an artist whose work on water blurs the lines between art, ecology, and activism.

The Ethics of Making (and Publishing) AI Art

This post is part of Lifehacker’s “Living With AI” series: We investigate the current state of AI, walk through how it can be useful (and how it can’t), and evaluate where this revolutionary tech is heading next. Read more here .

AI-generated art isn’t a concept: It’s here. Thanks to numerous tools with simple and approachable interfaces, anyone can hop on their computer can start generating whatever image ideas pop into their minds. However, as more people have started experimenting with these tools, serious ethical and legal issues have cropped up, and just about everyone online seems to have an opinion on this divisive technology.

As part of our series on living with AI, we put together this guide to demystify how AI art tools work, explain the controversies around them, and show how they impact everyone, from professional artists to curious casuals.

Where and how to make AI art

Before we get too far in the weeds on the tech and ethics of AI art, let’s quickly overview the tools themselves.

There are many AI art generators out there, but the major players would be Midjourney , Stable Diffusion, Bing’s AI image creator , DALLE-2 , Craiyon , and Dream . All of these tools are accessible via the web or desktop, and Dream also has a mobile app.

Midjourney is considered the most powerful , but it requires a subscription starting at $10 per month. Midjourney also requires a Discord account, since it operates entirely through a dedicate Discord chat server. That means you’re working alongside other users, and all your images are posted publicly on Midjourney’s web gallery, unless you pay $60 per month for the “stealth mode” feature.

DALLE-2 also generates high-quality images, but new users must pay at least $15 to sign up to use it. While your session and creations are private, it uses a confusing token system where each word in your prompt costs a certain amount of money, and you need to pay extra if you go beyond your token limit.

Bing’s AI generator and Stable Diffusion are entirely free and let you make as many images as you want, but image generation takes longer, especially if the servers are busy. Craiyon is also free, but subject to longer generation times, and image quality is lower. Lastly, Dream offers a decent middle ground between quality and price, letting you make one image at a time for free, or up to four with a paid account starting at $10 per month.

In terms of approachability, Bing’s AI generator is by far the best option if you’re just curious about these tools. It’s free, and you can access it from the Bing search homepage or in the Edge browser.

That said, despite the differences in quality and and interface, these tools all work the same way: You type a prompt into a text box describing the image you want to see, press enter, then wait a few moments for the AI to generate the picture based on your description.

The quality of the final product will depend on which tool you’re using and how detailed your prompt is. Some tools, like Midjourney and Stable Diffusion, have guides on coming up with better prompts , and even extra features that can help the AI get closer to your intended result . But even with these extra steps, the process only takes a few moments, and every tool is simple to start using.

How do these tools learn how to draw? And why are there too many fingers?

The images you get from these tools can be impressive, but it’s not because the software actually knows how to draw.

As I pointed out earlier this year, calling these products “AI” is a misnomer. Unlike the common conception of artificial intelligence as seen in science fiction media, these tools are not alive, sentient, or aware in any way, and they do not reason or learn. This is true of both text-based chatbots like ChatGPT and generative art tools like Midjourney. In the simplest terms, they work like your phone’s predictive text, pulling from a list of possible solutions to your prompt. When it comes to generative art tools specifically, the tool simply searches for images that match the keywords or descriptions in your prompt, then mashes the elements together.

This is entirely different from the actual process of drawing—in fact, the AI never “draws” anything at all, which is why these tools are notorious for “not knowing how to draw hands.”

As video game designer Doc Burford explains, “If I tell a machine ‘show me Nic Cage dressed as Superman,’ the machine may have images tagged with ‘Nic Cage,’ and it may have images tagged ‘Superman,’ but where the thinking mind of an actual intelligence will put those ideas together and fill in the blank spots with things it knows—like an artist who has also memorized human anatomy—the AI is still gonna give me an imperfect S-Shield on Superman’s chest, it’s gonna mess up the fingers.”

Ethical and legal concerns of AI art

These tools are easy to use and can oftentimes spit back compelling results—discounting the occasional extra digits and wonky faces—but there are major ethical concerns around making and distributing AI-generated art that go beyond quality and accuracy.

The main issue with generative AI art tools is they’re built on the backs of uncredited, unpaid artists whose art is used without consent. Every image you generate only exists because of the artists it’s copying from, even if those works aren’t copyrighted. Some AI evangelists like to claim these tools work “just like the human brain” and that “human artists are inspired by or reference other artists the same way,” but this is untrue for multiple reasons.

First, there is no being or mind in an AI, and therefore no memory, no intention, and no skill. Stable Diffusion isn’t “learning” how to draw or taking inspiration from another piece of art: It’s just an algorithm that searches and auto-fills data in the ways it’s programmed to. Humans, on the other hand, think, feel, and act with intention. Their works come from their memorized skill and lived experience. Even using another person’s art as a reference or inspiration is a deliberate choice informed by the artist’s goals.

To help explain the distinction, I reached out to Nicholas Kole, an illustrator and character designer who works with major film and video game studios like Disney, Activision, and Dreamworks. “The work I do, as a concept artist and illustrator, begins with digging deeply into the context of each project,” he says. “I ask pointed questions, tease out ideas about worldbuilding, story, gameplay [and] the process from start to finish is extremely specific, bespoke, and tailored to the precise needs of my colleagues and clients. Every single cufflink, belt buckle, prop, and motif—the art we make is the careful work of thoughtful design, done lovingly and with attention to detail.”

“The intrusion of an algorithm into that process, that doesn’t care for context, that doesn’t know whether people have 5 or 17 fingers, that mashes up visual guesswork based on stolen data, and functions essentially like a million monkeys at a million typewriters is anathema to me.”

Kole says AI art “flies in the face of everything I stand for creatively, and everything I’ve wanted to do with my life’s work. It’s an insult to the reason I make and engage with art—I want to see thoughtful human craft that is expressive, and express myself with thoughtful human craft.” A quick glance through portfolio sites like Art Station shows Kole is not alone in those sentiments, with many professional artists taking a hard stand against AI art.

This hardline stance isn’t just for ideological or aesthetic reasons, either. AI automatization poses a threat to job security for many industries—it’s why unionized actors, screenwriters, Google contractors, and even airline workers are currently on strike around America. The threat to working artists is just as real.

AI art also poses a risk to the companies that employ these artists. There have already been major legal battles over AI art infringing on copyrighted materials, with the current outcomes favoring the original artists. As such, many companies outright ban the use of AI art and reject any applications from artists with AI-generated works in their portfolios to avoid any copyright issues.

Are there ethical uses of AI art?

Despite the ethical and legal issues, some argue there is a place for these tools, and that they can even be helpful to professional artists. In an interview with Kotaku , visual artist RJ Palmers says artists could use AI to “come up with loose compositions, color patterns, lighting, etc,” for example, and that the tools “can all be very cool for getting inspiration.”

Similarly, author and animator Scott Sullivan argues in his blog that AI is helpful for ideation and iteration while brainstorming, and that “it’s all about the artist’s intention and how they use the tool.”

But while AI art is contentious among professional artists, casual users may wonder whether any of this matters for the layperson or hobbyist that just wants to play with them once in a while. And, sure, AI tools could be used as toys, but it’s important to note that’s not how the creators of these products treat them.

Almost all AI art generators are commercial products in some way. Some are paid products like Midjourney or DALLE-2, while free services like Bing’s AI image generator earn Microsoft money through ad revenue. Some are also used as “proof of concept” examples to entice commercial clients to pay for the more powerful version of the tool.

In all cases, the people that make these tools earn money off the work of the artists whose work is used to create the image you’re generated, even if it’s just for fun. As Kole explains, “The generative system can’t function without the stolen lifes’ work of countless passionate people just like me. They each brought their lived experiences, opinions, fixations, and points of view to their bodies of work, only now to have them smashed together inexpertly and touted as original art.” Even if you don’t share or sell images you make, many of these tools keep a public record of all generated content that other users can download and distribute.

Given all these concerns, it’s hard to recommend AI art creators, even if the intent to use them is innocent. Nevertheless, these tools are here, and unless some future regulations force them to change, we can’t stop folks from giving them a try. But, if you do, please keep in mind the legal and ethical issues associated with making and sharing AI art, think twice about sharing it, and never claim an AI-generated image as your own work.

Sign up for Lifehacker's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

Click here to read the full article.

- Entertainment

- Rex Reed Reviews

- Awards Shows

- Climate Change

- Restaurants

- Gift Guides

- Business of Art

- Nightlife & Dining

- About Observer

- Advertise With Us

Why Defining Exactly Who Is and Isn’t an Artist Matters

Official definitions of 'artist' (of which there are a confusing many) come into play when artists are counted in a census, have to pay income taxes or want to apply for grants and live-work spaces..

The question of how to define art has plagued creatives and philosophers for centuries. Aristotle defined art as a true idea given physical form. Leo Tolstoy called it “a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings, and indispensable for the life and progress toward well-being of individuals and of humanity,” and Oscar Wilde identified art as “the most intense mode of individualism the world has known.” It seems we can, individually, define art, but we can’t reach a consensus.

Sign Up For Our Daily Newsletter

Thank you for signing up!

By clicking submit, you agree to our <a rel="noreferrer" href="http://observermedia.com/terms">terms of service</a> and acknowledge we may use your information to send you emails, product samples, and promotions on this website and other properties. You can opt out anytime.

The same issue arises when the goal is to define ‘artist.’ Lots of people want to be viewed as artists, and label themselves such, from tattooists (body artists) to chefs (culinary artists) to, more recently, GPT prompters (A.I. artists). If nailing down the definition of artist is a semantics issue, it’s also one with real-world consequences. In 2023, a Colorado web designer successfully claimed before the U.S. Supreme Court that she was an artist—versus a mere service provider—which meant she was exempt from the state’s public accommodations law and could refuse to create wedding websites for same-sex couples.

SEE ALSO: The Costume Institute’s ‘Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion’ Is Full of Couture Corpses

In fact, there are numerous spheres in which defining what an artist is and isn’t is important. There are, for instance, grants and studio or residential spaces set aside exclusively for artists, and the organizations or government agencies overseeing their assignment need to be clear on who is and isn’t an artist. Then there are surveys conducted by economic, social and cultural researchers into artists’ employment, artists’ healthcare coverage and needs, the economic benefits of creative communities and other related inquiries for whom broader definitions of artist create a methodological problem. Without the licenses, permits, state testing or reported income requirements of other professionals, determining who is or isn’t an artist starts to feel like a value judgment.

That said, sometimes proving that someone is an artist is not just about cultural cachet or bragging rights—”official” definitions of artist (of which there are a confusing many) come into play when artists are counted in a census or have to pay their income taxes. In these cases, a self-proclaimed artist might have to meet several criteria dictated by the U.S. government to show that they’re also an artist by trade.

An artist’s job is art . The Bureau of the Census (whose data is used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Endowment for the Arts and other agencies) makes a broad national survey every ten years, inquiring about sources of paid employment during the census week. People with more than one source of income are counted occupationally in the job at which they worked the greatest number of hours during the census reference week. Because the focus is on paid employment, rather than the amount of time spent in the studio or the desire to sell art, many artists are likely to be overlooked—that is, not counted as artists. On an individual basis, this doesn’t matter as census information is anonymized, and no art dealers will throw artists out of their galleries because the Census Bureau didn’t classify them as artists. There is, however, a national policy downside: municipal, state and federal legislators are less likely to give money to the arts or to create laws that benefit artists if this group is significantly undercounted.

Artists devote time to their art . Although the National Endowment for the Arts makes use of Census Bureau data, the agency has conducted its own surveys of artists in the visual and performance spaces over the years. One of those surveys, “Visual Artists in Four Cities” (Houston, Minneapolis, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.), identified artists by their level of activity, i.e., how many hours per week they spend on art, counting those who had exhibited in some gallery or other art space in those cities over several years.

An artist turns a profit on their art . If the Census Bureau takes a broad, sweeping view of the definition of artist, the Internal Revenue Service takes a narrow one, examining individual taxpayers’ returns, and the federal agency has its own definition of artists as professionals. There are nine criteria that the IRS applies to separate professionals from hobbyists (an important distinction, as professionals may deduct their expenses, hobbyists may not).

- Is the activity carried on in a businesslike manner?

- Does the artist intend to make the artistic activity profitable?

- Does the individual depend in full or in part from income generated by the artistic work?

- Are business losses to be expected, or are they due to circumstances beyond the artist’s control?

- Are business plans changed to improve profitability?

- Does the artist have the knowledge to make the activity profitable?

- Has the artist been successful in previous professional activities?

- Does the activity generate a profit in some years and, if so, how much?

- Will the artist make a profit in the future?

The artist need not answer “yes” to every question to legitimately deduct business-related expenses – including art supplies and equipment, studio rental, travel (mileage, airfare, parking, tolls, meals and lodging), educational expenses (conferences, master classes, museum membership) and the cost of advertising and promotion (business cards, brochures, photography, postage and shipping), but the IRS demands proof that an artist has made a genuine effort to earn a profit in at least three years out of five.

Artistic credentials, which don’t usually matter to collectors, critics, dealers and curators, may also help an artist make a case that he or she is a professional for tax purposes. These include earning a bachelor’s or master’s degree in the fine arts, membership in an artists’ society, experience teaching art, inclusion in Who’s Who in American Art or a similar directory and an exhibition history.

An artist is someone who requires an artist’s studio . Several private and public agencies certify artists’ eligibility to rent or buy live-work loft space apartments that have both residential and studio components. Artist Certification committees are set up to evaluate applicants’ need for space and their qualifications as serious, but not necessarily professional, artists. According to the artist certification guidelines of the Boston Redevelopment Authority in Massachusetts, “Any artist who can demonstrate to a committee of peers that they have a recent body of work as an artist, and who requires loft-style space to support that work, is eligible.” The definition that these committees use is quite flexible, focusing on subjective factors (“…the nature of the commitment of the artist to his or her art form as his or her primary vocation rather than the amount of financial remuneration earned from his or her creative endeavor,” in the words of the Artist Certification Committee of New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs) rather than a set of hard numbers like exhibitions dates, sales, awards, memberships or commissions, which would disqualify most applicants. There is no written definition of artist at Artspace, the Minnesota-based developer of live-work spaces for artists around the country, and ad hoc certification committees at various sites look at applicants’ work (“they’re not making qualitative judgments, though,” Artspace spokeswoman Sarah Parker told Observer) to gauge the individual’s reputation within the artistic community.

An artist is an “independent contractor.” Artists are generally self-employed, working in their own studios, setting their own hours and creating objects that are of their own design and making, but sometimes they do work for others. For instance, they may serve as a studio assistant, helping another artist with practical matters, or they may be commissioned to produce an artwork, such as a monument, portrait or mural. In these circumstances, the definition of artist matters a lot, principally because of the issue of copyright. Someone who is an employee is paid a salary (and, perhaps, receives benefits, such as health insurance, sick and vacation pay), works certain set hours per week and is given explicit instructions on what tasks to fulfill and how to fulfill them at the employer’s work site, and the output that the individual produces on the job, which could be anything from paintings to sculpture, belongs to the employer. It is not uncommon, however, for artists who hire assistants to get around the need to pay taxes for these employees by calling them independent contractors, potentially giving those assistants a legal basis to be considered joint authors of the artists’ work if they were involved directly with the finished pieces. That joint authorship would be dependent upon the degree to which the assistant could prove that his or her original ideas and decision-making are part of the final work, according to Joshua Kaufman, a Washington, D.C. lawyer who often represents artists.

There have been some lawsuits brought by former assistants against the artists for whom they worked for joint copyright ownership of works, but they have all been settled out of court. However, in 1989, Kaufman successfully argued before the United States Supreme Court the right of sculptor James Earl Reid to claim copyright ownership of a work that a nonprofit group had commissioned him to create.

An artist is someone whom funding agencies call an artist . Public agencies and private organizations also provide money for individual artists, but nary one has published a formal definition of what an artist is. “We put this into the hands of our panel members,” Julie Gordon Dalgleish , former program director for artist fellowships at the Bush Foundation, told Observer. “We exclude certain things,” such as straight journalism, from the literature category and instructional videos from the category of film and video, but “we accepted an application from someone who braids hair. We would look at a tattoo artist if we felt there was a strong vision, creative energy and perseverance.” By we, of course, she meant the panels that review artists’ applications for fellowships to decide who receives money. Panel members regularly debate the question of whether or not a craft artist is an artist—a topic with a decades-long history. More recent concerns involve new media and digital art in two dimensions and three dimensions.

Ultimately, for most purposes, artists are people who call themselves artists. According to Marcel Duchamp , the artist defines art, and it seems increasingly true that nowadays artists also define who and what they are. Definitions by nature are confining and restrictive, while art and its makers seek to be expansive and inclusive. It may be simpler to state what makes an artist a professional than what defines an artist. ‘Artist’ has become a universal label denoting creativity and using it is often a way to shine a light on someone who does something particularly well. Socially, artists are often defined by the positive (freedom-loving, convention-defying) or negative (egotistical, bohemian) characteristics that other people attribute to them. Part of an artist’s job is to understand how artists are seen and what is expected of them, whether that’s by a certification committee that wants to see their body of work, a funding source that wants to understand the artist’s proposal, a dealer who wants to see what they’re capable of or the government, which more often than not, just wants to see the receipts.

- SEE ALSO : The World’s First Desktop Computer Heads to Auction

We noticed you're using an ad blocker.

We get it: you like to have control of your own internet experience. But advertising revenue helps support our journalism. To read our full stories, please turn off your ad blocker. We'd really appreciate it.

How Do I Whitelist Observer?

Below are steps you can take in order to whitelist Observer.com on your browser:

For Adblock:

Click the AdBlock button on your browser and select Don't run on pages on this domain .

For Adblock Plus on Google Chrome:

Click the AdBlock Plus button on your browser and select Enabled on this site.

For Adblock Plus on Firefox:

Click the AdBlock Plus button on your browser and select Disable on Observer.com.

Kernel Virtual Machine

KVM (for Kernel-based Virtual Machine) is a full virtualization solution for Linux on x86 hardware containing virtualization extensions (Intel VT or AMD-V). It consists of a loadable kernel module, kvm.ko, that provides the core virtualization infrastructure and a processor specific module, kvm-intel.ko or kvm-amd.ko.

Using KVM, one can run multiple virtual machines running unmodified Linux or Windows images. Each virtual machine has private virtualized hardware: a network card, disk, graphics adapter, etc.

KVM is open source software. The kernel component of KVM is included in mainline Linux, as of 2.6.20. The userspace component of KVM is included in mainline QEMU, as of 1.3.

Blogs from people active in KVM-related virtualization development are syndicated at http://planet.virt-tools.org/

- KVM Forum 2023

- KVM Forum 2022

- KVM Forum 2021

- KVM Forum 2020

- KVM Forum 2019

Random Articles

Featured article.

The KVM project celebrates 10 years!

See the announcement at this link , and this LWN.net article for some history of the project.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Assignments. SINCE 2013, The Art Assignment has been gathering assignments from a wide range of artists, Each commissioned to create a prompt based on their own way of working. you don't need to have special skills or training in order to do them, and The only materials you'll need are ones you probably already have or can source for free.

The Art Assignment is an educational video series that introduces you to innovative artists, presents you with assignments, and explores art history through the lens of the present. The series premiered in 2014 as a co-production of PBS Digital Studios and Complexly, with episodes featuring emerging and established artists who share assignments ...

Pre-order our book YOU ARE AN ARTIST (which includes new assignments!) here: http://bit.ly/2kplj2h So you look at a work of art and think to yourself, I coul...

The Art Assignment is a book! New assignments, along with a selection gathered during the course of making the series, is available for sale in the usual places books are sold. If your favorite local book shop or library doesn't have it in stock, ask for it! You Are an Artist includes over 50 assignments from some of the most innovative ...