Business development

- Billing management software

- Court management software

- Legal calendaring solutions

Practice management & growth

- Project & knowledge management

- Workflow automation software

Corporate & business organization

- Business practice & procedure

Legal forms

- Legal form-building software

Legal data & document management

- Data management

- Data-driven insights

- Document management

- Document storage & retrieval

Drafting software, service & guidance

- Contract services

- Drafting software

- Electronic evidence

Financial management

- Outside counsel spend

Law firm marketing

- Attracting & retaining clients

- Custom legal marketing services

Legal research & guidance

- Anywhere access to reference books

- Due diligence

- Legal research technology

Trial readiness, process & case guidance

- Case management software

- Matter management

Recommended Products

Conduct legal research efficiently and confidently using trusted content, proprietary editorial enhancements, and advanced technology.

Accelerate how you find answers with powerful generative AI capabilities and the expertise of 650+ attorney editors. With Practical Law, access thousands of expertly maintained how-to guides, templates, checklists, and more across all major practice areas.

A business management tool for legal professionals that automates workflow. Simplify project management, increase profits, and improve client satisfaction.

- All products

Tax & Accounting

Audit & accounting.

- Accounting & financial management

- Audit workflow

- Engagement compilation & review

- Guidance & standards

- Internal audit & controls

- Quality control

Data & document management

- Certificate management

- Data management & mining

- Document storage & organization

Estate planning

- Estate planning & taxation

- Wealth management

Financial planning & analysis

- Financial reporting

Payroll, compensation, pension & benefits

- Payroll & workforce management services

- Healthcare plans

- Billing management

- Client management

- Cost management

- Practice management

- Workflow management

Professional development & education

- Product training & education

- Professional development

Tax planning & preparation

- Financial close

- Income tax compliance

- Tax automation

- Tax compliance

- Tax planning

- Tax preparation

- Sales & use tax

- Transfer pricing

- Fixed asset depreciation

Tax research & guidance

- Federal tax

- State & local tax

- International tax

- Tax laws & regulations

- Partnership taxation

- Research powered by AI

- Specialized industry taxation

- Credits & incentives

- Uncertain tax positions

A powerful tax and accounting research tool. Get more accurate and efficient results with the power of AI, cognitive computing, and machine learning.

Provides a full line of federal, state, and local programs. Save time with tax planning, preparation, and compliance.

Automate work paper preparation and eliminate data entry

Trade & Supply

Customs & duties management.

- Customs law compliance & administration

Global trade compliance & management

- Global export compliance & management

- Global trade analysis

- Denied party screening

Product & service classification

- Harmonized Tariff System classification

Supply chain & procurement technology

- Foreign-trade zone (FTZ) management

- Supply chain compliance

Software that keeps supply chain data in one central location. Optimize operations, connect with external partners, create reports and keep inventory accurate.

Automate sales and use tax, GST, and VAT compliance. Consolidate multiple country-specific spreadsheets into a single, customizable solution and improve tax filing and return accuracy.

Risk & Fraud

Risk & compliance management.

- Regulatory compliance management

Fraud prevention, detection & investigations

- Fraud prevention technology

Risk management & investigations

- Investigation technology

- Document retrieval & due diligence services

Search volumes of data with intuitive navigation and simple filtering parameters. Prevent, detect, and investigate crime.

Identify patterns of potentially fraudulent behavior with actionable analytics and protect resources and program integrity.

Analyze data to detect, prevent, and mitigate fraud. Focus investigation resources on the highest risks and protect programs by reducing improper payments.

News & Media

Who we serve.

- Broadcasters

- Governments

- Marketers & Advertisers

- Professionals

- Sports Media

- Corporate Communications

- Health & Pharma

- Machine Learning & AI

Content Types

- All Content Types

- Human Interest

- Business & Finance

- Entertainment & Lifestyle

- Reuters Community

- Reuters Plus - Content Studio

- Advertising Solutions

- Sponsorship

- Verification Services

- Action Images

- Reuters Connect

- World News Express

- Reuters Pictures Platform

- API & Feeds

- Reuters.com Platform

Media Solutions

- User Generated Content

- Reuters Ready

- Ready-to-Publish

- Case studies

- Reuters Partners

- Standards & values

- Leadership team

- Reuters Best

- Webinars & online events

Around the globe, with unmatched speed and scale, Reuters Connect gives you the power to serve your audiences in a whole new way.

Reuters Plus, the commercial content studio at the heart of Reuters, builds campaign content that helps you to connect with your audiences in meaningful and hyper-targeted ways.

Reuters.com provides readers with a rich, immersive multimedia experience when accessing the latest fast-moving global news and in-depth reporting.

- Reuters Media Center

- Jurisdiction

- Practice area

- View all legal

- Organization

- View all tax

Featured Products

- Blacks Law Dictionary

- Thomson Reuters ProView

- Recently updated products

- New products

Shop our latest titles

ProView Quickfinder favorite libraries

- Visit legal store

- Visit tax store

APIs by industry

- Risk & Fraud APIs

- Tax & Accounting APIs

- Trade & Supply APIs

Use case library

- Legal API use cases

- Risk & Fraud API use cases

- Tax & Accounting API use cases

- Trade & Supply API use cases

Related sites

United states support.

- Account help & support

- Communities

- Product help & support

- Product training

International support

- Legal UK, Ireland & Europe support

New releases

- Westlaw Precision

- 1040 Quickfinder Handbook

Join a TR community

- ONESOURCE community login

- Checkpoint community login

- CS community login

- TR Community

Free trials & demos

- Westlaw Edge

- Practical Law

- Checkpoint Edge

- Onvio Firm Management

- Proview eReader

How to do legal research in 3 steps

Knowing where to start a difficult legal research project can be a challenge. But if you already understand the basics of legal research, the process can be significantly easier — not to mention quicker.

Solid research skills are crucial to crafting a winning argument. So, whether you are a law school student or a seasoned attorney with years of experience, knowing how to perform legal research is important — including where to start and the steps to follow.

What is legal research, and where do I start?

Black's Law Dictionary defines legal research as “[t]he finding and assembling of authorities that bear on a question of law." But what does that actually mean? It means that legal research is the process you use to identify and find the laws — including statutes, regulations, and court opinions — that apply to the facts of your case.

In most instances, the purpose of legal research is to find support for a specific legal issue or decision. For example, attorneys must conduct legal research if they need court opinions — that is, case law — to back up a legal argument they are making in a motion or brief filed with the court.

Alternatively, lawyers may need legal research to provide clients with accurate legal guidance . In the case of law students, they often use legal research to complete memos and briefs for class. But these are just a few situations in which legal research is necessary.

Why is legal research hard?

Each step — from defining research questions to synthesizing findings — demands critical thinking and rigorous analysis.

1. Identifying the legal issue is not so straightforward. Legal research involves interpreting many legal precedents and theories to justify your questions. Finding the right issue takes time and patience.

2. There's too much to research. Attorneys now face a great deal of case law and statutory material. The sheer volume forces the researcher to be efficient by following a methodology based on a solid foundation of legal knowledge and principles.

3. The law is a fluid doctrine. It changes with time, and staying updated with the latest legal codes, precedents, and statutes means the most resourceful lawyer needs to assess the relevance and importance of new decisions.

Legal research can pose quite a challenge, but professionals can improve it at every stage of the process .

Step 1: Key questions to ask yourself when starting legal research

Before you begin looking for laws and court opinions, you first need to define the scope of your legal research project. There are several key questions you can use to help do this.

What are the facts?

Always gather the essential facts so you know the “who, what, why, when, where, and how” of your case. Take the time to write everything down, especially since you will likely need to include a statement of facts in an eventual filing or brief anyway. Even if you don't think a fact may be relevant now, write it down because it may be relevant later. These facts will also be helpful when identifying your legal issue.

What is the actual legal issue?

You will never know what to research if you don't know what your legal issue is. Does your client need help collecting money from an insurance company following a car accident involving a negligent driver? How about a criminal case involving excluding evidence found during an alleged illegal stop?

No matter the legal research project, you must identify the relevant legal problem and the outcome or relief sought. This information will guide your research so you can stay focused and on topic.

What is the relevant jurisdiction?

Don't cast your net too wide regarding legal research; you should focus on the relevant jurisdiction. For example, does your case deal with federal or state law? If it is state law, which state? You may find a case in California state court that is precisely on point, but it won't be beneficial if your legal project involves New York law.

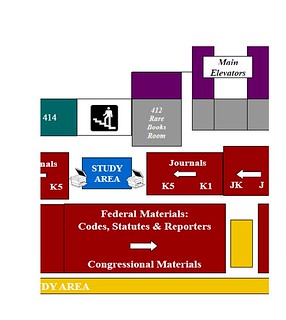

Where to start legal research: The library, online, or even AI?

In years past, future attorneys were trained in law school to perform research in the library. But now, you can find almost everything from the library — and more — online. While you can certainly still use the library if you want, you will probably be costing yourself valuable time if you do.

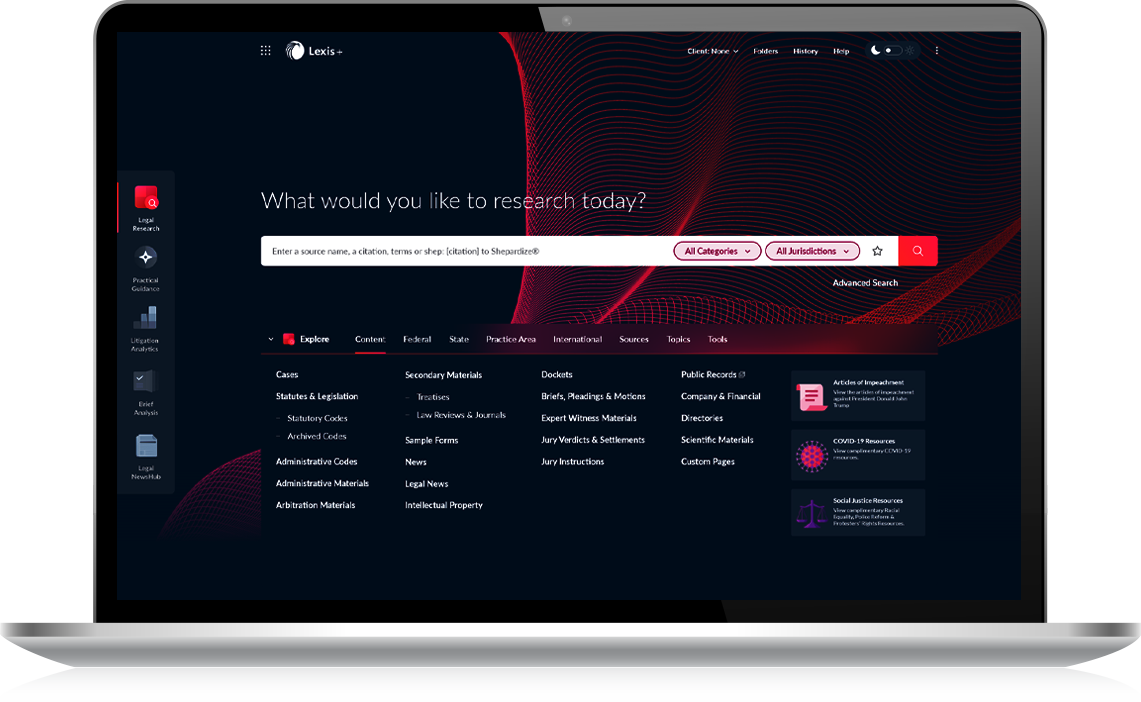

When it comes to online research, some people start with free legal research options , including search engines like Google or Bing. But to ensure your legal research is comprehensive, you will want to use an online research service designed specifically for the law, such as Westlaw . Not only do online solutions like Westlaw have all the legal sources you need, but they also include artificial intelligence research features that help make quick work of your research

Step 2: How to find relevant case law and other primary sources of law

Now that you have gathered the facts and know your legal issue, the next step is knowing what to look for. After all, you will need the law to support your legal argument, whether providing guidance to a client or writing an internal memo, brief, or some other legal document.

But what type of law do you need? The answer: primary sources of law. Some of the more important types of primary law include:

- Case law, which are court opinions or decisions issued by federal or state courts

- Statutes, including legislation passed by both the U.S. Congress and state lawmakers

- Regulations, including those issued by either federal or state agencies

- Constitutions, both federal and state

Searching for primary sources of law

So, if it's primary law you want, it makes sense to begin searching there first, right? Not so fast. While you will need primary sources of law to support your case, in many instances, it is much easier — and a more efficient use of your time — to begin your search with secondary sources such as practice guides, treatises, and legal articles.

Why? Because secondary sources provide a thorough overview of legal topics, meaning you don't have to start your research from scratch. After secondary sources, you can move on to primary sources of law.

For example, while no two legal research projects are the same, the order in which you will want to search different types of sources may look something like this:

- Secondary sources . If you are researching a new legal principle or an unfamiliar area of the law, the best place to start is secondary sources, including law journals, practice guides , legal encyclopedias, and treatises. They are a good jumping-off point for legal research since they've already done the work for you. As an added bonus, they can save you additional time since they often identify and cite important statutes and seminal cases.

- Case law . If you have already found some case law in secondary sources, great, you have something to work with. But if not, don't fret. You can still search for relevant case law in a variety of ways, including running a search in a case law research tool.

Once you find a helpful case, you can use it to find others. For example, in Westlaw, most cases contain headnotes that summarize each of the case's important legal issues. These headnotes are also assigned a Key Number based on the topic associated with that legal issue. So, once you find a good case, you can use the headnotes and Key Numbers within it to quickly find more relevant case law.

- Statutes and regulations . In many instances, secondary sources and case law list the statutes and regulations relevant to your legal issue. But if you haven't found anything yet, you can still search for statutes and regs online like you do with cases.

Once you know which statute or reg is pertinent to your case, pull up the annotated version on Westlaw. Why the annotated version? Because the annotations will include vital information, such as a list of important cases that cite your statute or reg. Sometimes, these cases are even organized by topic — just one more way to find the case law you need to support your legal argument.

Keep in mind, though, that legal research isn't always a linear process. You may start out going from source to source as outlined above and then find yourself needing to go back to secondary sources once you have a better grasp of the legal issue. In other instances, you may even find the answer you are looking for in a source not listed above, like a sample brief filed with the court by another attorney. Ultimately, you need to go where the information takes you.

Step 3: Make sure you are using ‘good’ law

One of the most important steps with every legal research project is to verify that you are using “good" law — meaning a court hasn't invalidated it or struck it down in some way. After all, it probably won't look good to a judge if you cite a case that has been overruled or use a statute deemed unconstitutional. It doesn't necessarily mean you can never cite these sources; you just need to take a closer look before you do.

The simplest way to find out if something is still good law is to use a legal tool known as a citator, which will show you subsequent cases that have cited your source as well as any negative history, including if it has been overruled, reversed, questioned, or merely differentiated.

For instance, if a case, statute, or regulation has any negative history — and therefore may no longer be good law — KeyCite, the citator on Westlaw, will warn you. Specifically, KeyCite will show a flag or icon at the top of the document, along with a little blurb about the negative history. This alert system allows you to quickly know if there may be anything you need to worry about.

Some examples of these flags and icons include:

- A red flag on a case warns you it is no longer good for at least one point of law, meaning it may have been overruled or reversed on appeal.

- A yellow flag on a case warns that it has some negative history but is not expressly overruled or reversed, meaning another court may have criticized it or pointed out the holding was limited to a specific fact pattern.

- A blue-striped flag on a case warns you that it has been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court or the U.S. Court of Appeals.

- The KeyCite Overruling Risk icon on a case warns you that the case may be implicitly undermined because it relies on another case that has been overruled.

Another bonus of using a citator like KeyCite is that it also provides a list of other cases that merely cite your source — it can lead to additional sources you previously didn't know about.

Perseverance is vital when it comes to legal research

Given that legal research is a complex process, it will likely come as no surprise that this guide cannot provide everything you need to know.

There is a reason why there are entire law school courses and countless books focused solely on legal research methodology. In fact, many attorneys will spend their entire careers honing their research skills — and even then, they may not have perfected the process.

So, if you are just beginning, don't get discouraged if you find legal research difficult — almost everyone does at first. With enough time, patience, and dedication, you can master the art of legal research.

Thomson Reuters originally published this article on November 10, 2020.

Related insights

Westlaw tip of the week: Checking cases with KeyCite

Why legislative history matters when crafting a winning argument

Case law research tools: The most useful free and paid offerings

Request a trial and experience the fastest way to find what you need

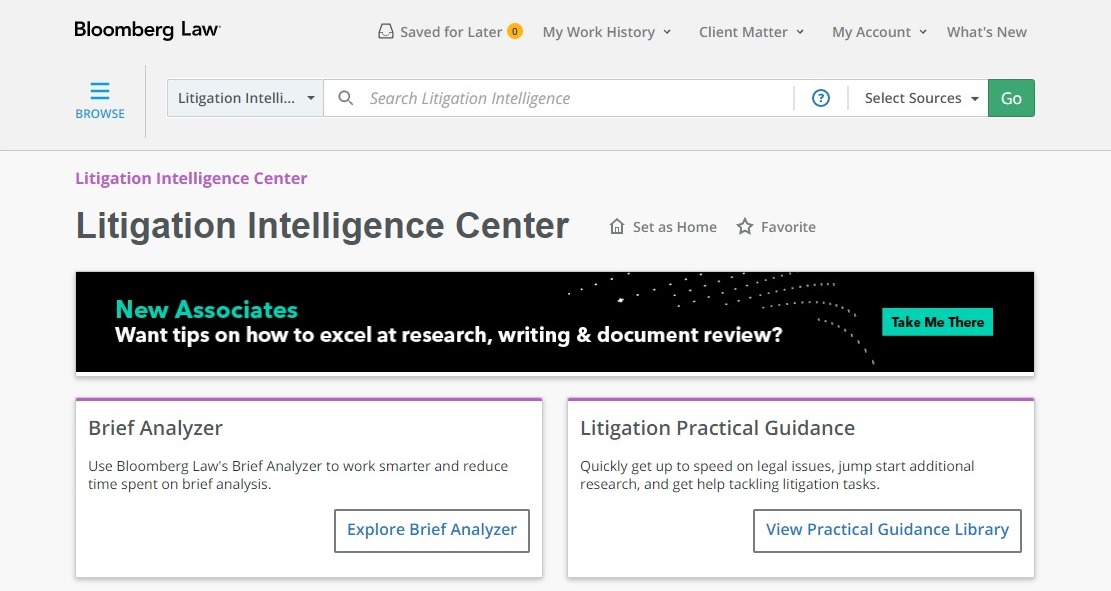

- Platform Overview All-in-one legal research and workflow software

- Legal Research Unmetered access to primary and secondary sources

- Workflow Tools AI-powered tools for smarter workflows

- News & Analysis Paywall-free premium Bloomberg news and coverage

- Practical Guidance Ready-to-use guidance for any legal task

- Contract Solutions New: Streamlined contract workflow platform

- Introducing Contract Solutions Experience contract simplicity

- Watch product demo

- Law Firms Find everything you need to serve your clients

- In-House Counsel Expand expertise, reduce cost, and save time

- Government Get unlimited access to state and federal coverage

- Law Schools Succeed in school and prepare for practice

- Customer Cost Savings and Benefits See why GCs and CLOs choose Bloomberg Law

- Getting Started Experience one platform, one price, and continuous innovation

- Our Initiatives Empower the next generation of lawyers

- Careers Explore alternative law careers and join our team

- Press Releases See our latest news and product updates

- DEI Framework Raising the bar for law firms

- Request Pricing

- Legal Solutions

How to Conduct Legal Research

September 21, 2021

Conducting legal research can challenge even the most skilled law practitioners.

As laws evolve across jurisdictions, it can be a difficult to keep pace with every legal development. Equally daunting is the ability to track and glean insights into stakeholder strategies and legal responses. Without quick and easy access to the right tools, the legal research upon which case strategy hinges may face cost, personnel, and litigation outcome challenges.

Bloomberg Law’s artificial intelligence-driven tools drastically reduce the time to perform legal research. Whether you seek quick answers to legal research definitions, or general guidance on the legal research process, Bloomberg Law’s Core Litigation Skills Toolkit has you covered.

What is legal research?

Legal research is the process of uncovering and understanding all of the legal precedents, laws, regulations, and other legal authorities that apply in a case and inform an attorney’s course of action.

Legal research often involves case law research, which is the practice of identifying and interpreting the most relevant cases concerning the topic at issue. Legal research can also involve a deep dive into a judge’s past rulings or opposing counsel’s record of success.

Research is not a process that has a finite start and end, but remains ongoing throughout every phase of a legal matter. It is a cornerstone of a litigator’s skills.

[Learn how our integrated, time-saving litigation research tools allow litigators to streamline their work and get answers quickly.]

Where do I begin my legal research?

Beginning your legal research will look different for each assignment. At the outset, ensure that you understand your goal by asking questions and taking careful notes. Ask about background case information, logistical issues such as filing deadlines, the client/matter number, and billing instructions.

It’s also important to consider how your legal research will be used. Is the research to be used for a pending motion? If you are helping with a motion for summary judgment, for example, your goal is to find cases that are in the same procedural posture as yours and come out favorably for your side (i.e., if your client is the one filing the motion, try to find cases where a motion for summary judgment was granted, not denied). Keep in mind the burden of proof for different kinds of motions.

Finally, but no less important, assess the key facts of the case. Who are the relevant parties? Where is the jurisdiction? Who is the judge? Note all case details that come to mind.

What if I’m new to the practice area or specific legal issue?

While conducting legal research, it is easy to go down rabbit holes. Resist the urge to start by reviewing individual cases, which may prove irrelevant. Start instead with secondary sources, which often provide a prevailing statement of the law for a specific topic. These sources will save time and orient you to the area of the law and key issues.

Litigation Practical Guidance provides the essentials including step-by-step guidance, expert legal analysis, and a preview of next steps. Source citations are included in all Practical Guidance, and you can filter Points of Law, Smart Code®, and court opinions searches to get the jurisdiction-specific cases or statutes you need.

Searching across Points of Law will help to get your bearings on an issue before diving into reading the cases in full. Points of Law uses machine learning to identify key legal principles expressed in court opinions, which are easily searchable by keyword and jurisdiction. This tool helps you quickly find other cases that have expressed the same Point of Law, and directs you to related Points of Law that might be relevant to your research. It is automatically updated with the most recent opinions, saving you time and helping you quickly drill down to the relevant cases.

How do I respond to the opposing side’s brief?

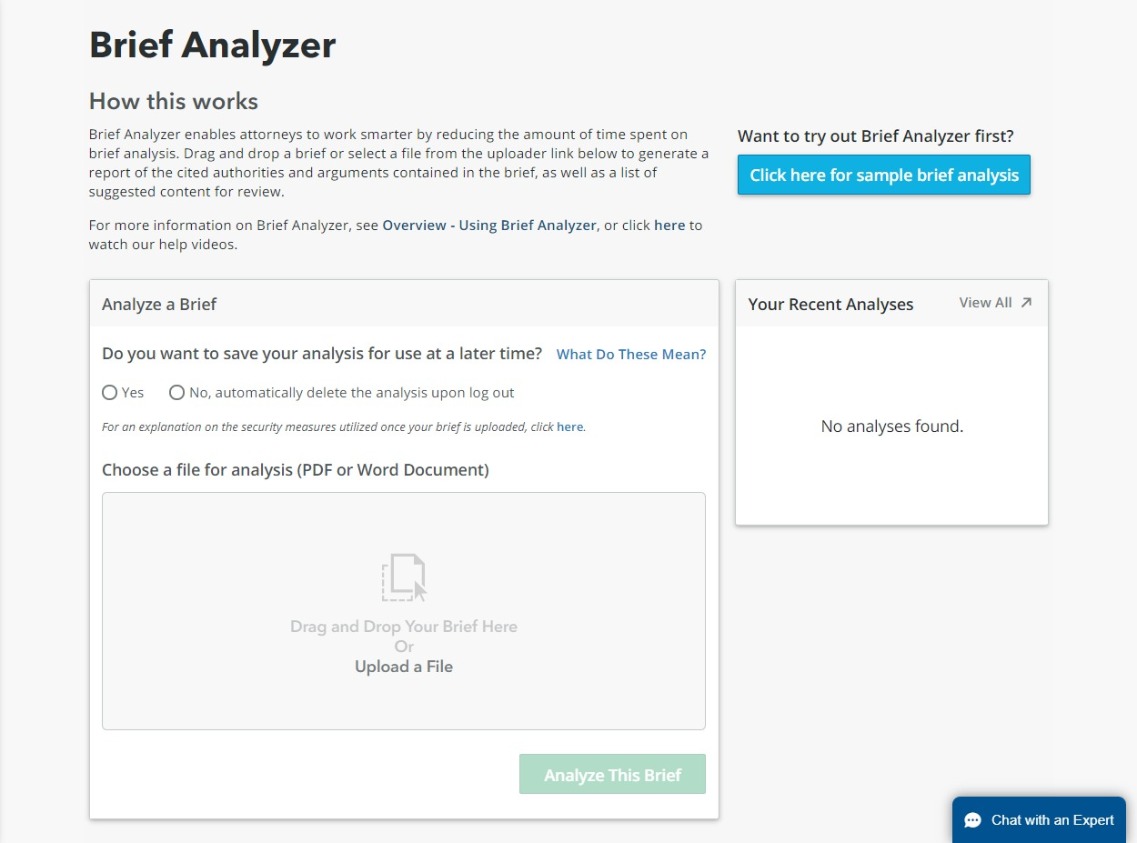

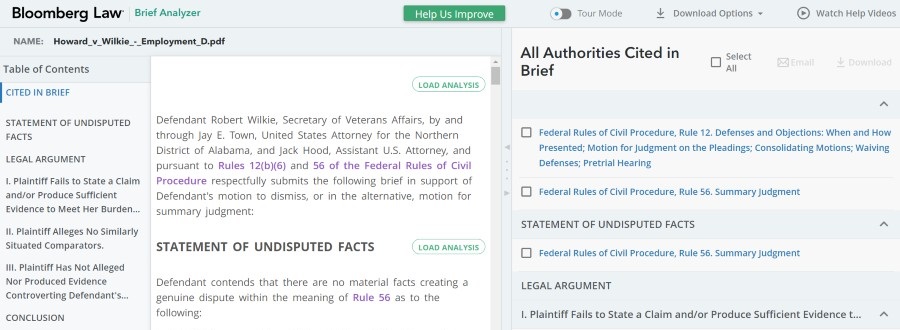

Whether a brief is yours or that of the opposing party, Bloomberg Law’s Brief Analyzer is an essential component in the legal research process. It reduces the time spent analyzing a brief, identifying relevant authorities, and preparing a solid response.

To start, navigate to Brief Analyzer available from the Bloomberg Law homepage, within the Litigation Intelligence Center , or from Docket Key search results for briefs.

Simply upload the opposing side’s brief into the tool, and Brief Analyzer will generate a report of the cited authorities and arguments contained in the brief.

You can easily view a comparison with the brief and analysis side by side. It will also point you directly to relevant cases, Points of Law, and Practical Guidance to jump start your research.

[ How to Write a Legal Brief – Learn how to shorten the legal research cycle and give your legal brief a competitive advantage.]

How to optimize your search.

Crafting searches is a critical skill when it comes to legal research. Although many legal research platforms, including Bloomberg Law, offer natural language searching, terms and connectors (also called Boolean) searching is still a vital legal research skill and should be used when searching across court opinions, dockets, Points of Law, and other primary and secondary sources.

When you conduct a natural language search, the search engine applies algorithms to rank your results. Why a certain case is ranked as it is may not be obvious. This makes it harder to interpret whether the search is giving you everything you need. It is also harder to efficiently and effectively manipulate your search terms to zero in on the results you want. Using Boolean searching gives you better control over your search and greater confidence in your results.

The good news? Bloomberg Law does not charge by the search for court opinion searches. If your initial search was much too broad or much too narrow, you do not have to worry about immediately running a new and improved search.

Follow these tips when beginning a search to ensure that you do not miss relevant materials:

- Make sure you do not have typos in your search string.

- Search the appropriate source or section of the research platform. It is possible to search only within a practice area, jurisdiction, secondary resource, or other grouping of materials.

- Make sure you know which terms and connectors are utilized by the platform you are working on and what they mean – there is no uniform standard set of terms of connectors utilized by all platforms.

- Include in your search all possible terms the court might use, or alternate ways the court may address an issue. It is best to group the alternatives together within a parenthetical, connected by OR between each term.

- Consider including single and multiple character wildcards when relevant. Using a single character wildcard (an asterisk) and/or a multiple character wildcard (an exclamation point) helps you capture all word variations – even those you might not have envisioned.

- Try using a tool that helps you find additional relevant case law. When you find relevant authority, use BCITE on Bloomberg Law to find all other cases and/or sources that cite back to that case. When in BCITE, click on the Citing Documents tab, and search by keyword to narrow the results. Alternatively, you can use the court’s language or ruling to search Points of Law and find other cases that addressed the same issue or reached the same ruling.

[Bloomberg Law subscribers can access a complete checklist of search term best practices . Not a subscriber? Request a Demo .]

How can legal research help with drafting or strategy?

Before drafting a motion or brief, search for examples of what firm lawyers filed with the court in similar cases. You can likely find recent examples in your firm’s internal document system or search Bloomberg Law’s dockets. If possible, look for things filed before the same judge so you can get a quick check on rules/procedures to be followed (and by the same partner when possible so you can get an idea of their style preferences).

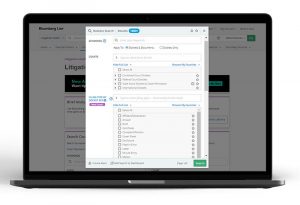

Careful docket search provides a wealth of information about relevant cases, jurisdictions, judges, and opposing counsel. On Bloomberg Law, type “Dockets Search” in the Go bar or find the dockets search box in the Litigation Intelligence Center .

If you do not know the specific docket number and/or court, use the docket search functionality Docket Key . Select from any of 20 categories, including motions, briefs, and orders, across all 94 federal district courts, to pinpoint the exact filing of choice.

Dockets can also help you access lots of information to guide your case strategy. For example, if you are considering filing a particular type of motion, such as a sanctions motion, you can use dockets to help determine how frequently your judge grants sanctions motions. You can also use dockets to see how similar cases before your judge proceeded through discovery.

If you are researching expert witnesses, you can use dockets to help determine if the expert has been recently excluded from a case, or whether their opinion has been limited. If so, this will help you determine whether the expert is a good fit for your case.

Dockets are a powerful research tool that allow you to search across filings to support your argument. Stay apprised of docket updates with the “Create Alert” option on Bloomberg Law.

Dive deeper into competitive research.

For even more competitive research insights, dive into Bloomberg Law’s Litigation Analytics – this is available in the Litigation tab on the homepage. Data here helps attorneys develop litigation strategy, predict possible outcomes, and better advise clients.

To start, under Litigation Analytics , leverage the Attorney tab to view case history and preview legal strategies the opposition may practice against you. Also, within Litigation Analytics, use the Court tab to get aggregate motion and appeal outcome rates across all federal courts, with the option to run comparisons across jurisdictions, and filter by company, law firm, and attorney.

Use the Judge tab to glean insights from cited opinions, and past and current decisions by motion and appeal outcomes. Also view litigation analytics in the right rail of court opinions.

Docket search can also offer intel on your opponent. Has your opponent filed similar lawsuits or made similar arguments before? How did those cases pan out? You can learn a lot about an opponent from past appearances in court.

How do I validate case law citations?

Checking the status of case law is essential in legal research. Rely on Bloomberg Law’s proprietary citator, BCITE. This time-saving tool lets you know if a case is still good law.

Under each court opinion, simply look to the right rail. There, you will see a thumbnail icon for “BCITE Analysis.” Click on the icon, and you will be provided quick links to direct history (opinions that affect or are affected by the outcome of the case at issue); case analysis (citing cases, with filter and search options), table of authorities, and citing documents.

How should I use technology to improve my legal research?

A significant benefit of digital research platforms and analytics is increased efficiency. Modern legal research technology helps attorneys sift through thousands of cases quickly and comprehensively. These products can also help aggregate or summarize data in a way that is more useful and make associations instantaneously.

For example, before litigation analytics were common, a partner may have asked a junior associate to find all summary judgment motions ruled on by a specific judge to determine how often that judge grants or denies them. The attorney could have done so by manually searching over PACER and/or by searching through court opinions, but that would take a long time. Now, Litigation Analytics can aggregate that data and provide an answer in seconds. Understanding that such products exist can be a game changer. Automating parts of the research process frees up time and effort for other activities that benefit the client and makes legal research and writing more efficient.

[Read our article: Six ways legal technology aids your litigation workflow .]

Tools like Points of Law , dockets and Brief Analyzer can also increase efficiency, especially when narrowing your research to confirm that you found everything on point. In the past, attorneys had to spend many hours (and lots of money) running multiple court opinion searches to ensure they did not miss a case on point. Now, there are tools that can dramatically speed up that process. For example, running a search over Points of Law can immediately direct you to other cases that discuss that same legal principle.

However, it’s important to remember that digital research and analytical tools should be seen as enhancing the legal research experience, not displacing the review, analysis, and judgment of an attorney. An attorney uses his or her knowledge of their client, the facts, the precedent, expert opinions, and his or her own experiences to predict the likely result in a given matter. Digital research products enhance this process by providing more data on a wider array of variables so that an attorney can take even more information into consideration.

[Get all your questions answered, request a Bloomberg Law demo , and more.]

Recommended for you

See bloomberg law in action.

From live events to in-depth reports, discover singular thought leadership from Bloomberg Law. Our network of expert analysts is always on the case – so you can make yours. Request a demo to see it for yourself.

Legal Research Strategy

Preliminary analysis, organization, secondary sources, primary sources, updating research, identifying an end point, getting help, about this guide.

This guide will walk a beginning researcher though the legal research process step-by-step. These materials are created with the 1L Legal Research & Writing course in mind. However, these resources will also assist upper-level students engaged in any legal research project.

How to Strategize

Legal research must be comprehensive and precise. One contrary source that you miss may invalidate other sources you plan to rely on. Sticking to a strategy will save you time, ensure completeness, and improve your work product.

Follow These Steps

Running Time: 3 minutes, 13 seconds.

Make sure that you don't miss any steps by using our:

- Legal Research Strategy Checklist

If you get stuck at any time during the process, check this out:

- Ten Tips for Moving Beyond the Brick Wall in the Legal Research Process, by Marsha L. Baum

Understanding the Legal Questions

A legal question often originates as a problem or story about a series of events. In law school, these stories are called fact patterns. In practice, facts may arise from a manager or an interview with a potential client. Start by doing the following:

- Read anything you have been given

- Analyze the facts and frame the legal issues

- Assess what you know and need to learn

- Note the jurisdiction and any primary law you have been given

- Generate potential search terms

Jurisdiction

Legal rules will vary depending on where geographically your legal question will be answered. You must determine the jurisdiction in which your claim will be heard. These resources can help you learn more about jurisdiction and how it is determined:

- Legal Treatises on Jurisdiction

- LII Wex Entry on Jurisdiction

This map indicates which states are in each federal appellate circuit:

Getting Started

Once you have begun your research, you will need to keep track of your work. Logging your research will help you to avoid missing sources and explain your research strategy. You will likely be asked to explain your research process when in practice. Researchers can keep paper logs, folders on Westlaw or Lexis, or online citation management platforms.

Organizational Methods

Tracking with paper or excel.

Many researchers create their own tracking charts. Be sure to include:

- Search Date

- Topics/Keywords/Search Strategy

- Citation to Relevant Source Found

- Save Locations

- Follow Up Needed

Consider using the following research log as a starting place:

- Sample Research Log

Tracking with Folders

Westlaw and Lexis offer options to create folders, then save and organize your materials there.

- Lexis Advance Folders

- Westlaw Edge Folders

Tracking with Citation Management Software

For long term projects, platforms such as Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley, or Refworks might be useful. These are good tools to keep your research well organized. Note, however, that none of these platforms substitute for doing your own proper Bluebook citations. Learn more about citation management software on our other research guides:

- Guide to Zotero for Harvard Law Students by Harvard Law School Library Research Services Last Updated Sep 12, 2023 300 views this year

Types of Sources

There are three different types of sources: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary. When doing legal research you will be using mostly primary and secondary sources. We will explore these different types of sources in the sections below.

Secondary sources often explain legal principles more thoroughly than a single case or statute. Starting with them can help you save time.

Secondary sources are particularly useful for:

- Learning the basics of a particular area of law

- Understanding key terms of art in an area

- Identifying essential cases and statutes

Consider the following when deciding which type of secondary source is right for you:

- Scope/Breadth

- Depth of Treatment

- Currentness/Reliability

For a deep dive into secondary sources visit:

- Secondary Sources: ALRs, Encyclopedias, Law Reviews, Restatements, & Treatises by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 4863 views this year

Legal Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

Legal dictionaries.

Legal dictionaries are similar to other dictionaries that you have likely used before.

- Black's Law Dictionary

- Ballentine's Law Dictionary

Legal Encyclopedias

Legal encyclopedias contain brief, broad summaries of legal topics, providing introductions and explaining terms of art. They also provide citations to primary law and relevant major law review articles.

Here are the two major national encyclopedias:

- American Jurisprudence (AmJur) This resource is also available in Westlaw & Lexis .

- Corpus Juris Secundum (CJS)

Treatises are books on legal topics. These books are a good place to begin your research. They provide explanation, analysis, and citations to the most relevant primary sources. Treatises range from single subject overviews to deep treatments of broad subject areas.

It is important to check the date when the treatise was published. Many are either not updated, or are updated through the release of newer editions.

To find a relevant treatise explore:

- Legal Treatises by Subject by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 3878 views this year

American Law Reports (ALR)

American Law Reports (ALR) contains in-depth articles on narrow topics of the law. ALR articles, are often called annotations. They provide background, analysis, and citations to relevant cases, statutes, articles, and other annotations. ALR annotations are invaluable tools to quickly find primary law on narrow legal questions.

This resource is available in both Westlaw and Lexis:

- American Law Reports on Westlaw (includes index)

- American Law Reports on Lexis

Law Reviews & Journals

Law reviews are scholarly publications, usually edited by law students in conjunction with faculty members. They contain both lengthy articles and shorter essays by professors and lawyers. They also contain comments, notes, or developments in the law written by law students. Articles often focus on new or emerging areas of law and may offer critical commentary. Some law reviews are dedicated to a particular topic while others are general. Occasionally, law reviews will include issues devoted to proceedings of panels and symposia.

Law review and journal articles are extremely narrow and deep with extensive references.

To find law review articles visit:

- Law Journal Library on HeinOnline

- Law Reviews & Journals on LexisNexis

- Law Reviews & Journals on Westlaw

Restatements

Restatements are highly regarded distillations of common law, prepared by the American Law Institute (ALI). ALI is a prestigious organization comprised of judges, professors, and lawyers. They distill the "black letter law" from cases to indicate trends in common law. Resulting in a “restatement” of existing common law into a series of principles or rules. Occasionally, they make recommendations on what a rule of law should be.

Restatements are not primary law. However, they are considered persuasive authority by many courts.

Restatements are organized into chapters, titles, and sections. Sections contain the following:

- a concisely stated rule of law,

- comments to clarify the rule,

- hypothetical examples,

- explanation of purpose, and

- exceptions to the rule

To access restatements visit:

- American Law Institute Library on HeinOnline

- Restatements & Principles of the Law on LexisNexis

- Restatements & Principles of Law on Westlaw

Primary Authority

Primary authority is "authority that issues directly from a law-making body." Authority , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). Sources of primary authority include:

- Constitutions

- Statutes

Regulations

Access to primary legal sources is available through:

- Bloomberg Law

- Free & Low Cost Alternatives

Statutes (also called legislation) are "laws enacted by legislative bodies", such as Congress and state legislatures. Statute , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

We typically start primary law research here. If there is a controlling statute, cases you look for later will interpret that law. There are two types of statutes, annotated and unannotated.

Annotated codes are a great place to start your research. They combine statutory language with citations to cases, regulations, secondary sources, and other relevant statutes. This can quickly connect you to the most relevant cases related to a particular law. Unannotated Codes provide only the text of the statute without editorial additions. Unannotated codes, however, are more often considered official and used for citation purposes.

For a deep dive on federal and state statutes, visit:

- Statutes: US and State Codes by Mindy Kent Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 3245 views this year

- 50 State Surveys

Want to learn more about the history or legislative intent of a law? Learn how to get started here:

- Legislative History Get an introduction to legislative histories in less than 5 minutes.

- Federal Legislative History Research Guide

Regulations are rules made by executive departments and agencies. Not every legal question will require you to search regulations. However, many areas of law are affected by regulations. So make sure not to skip this step if they are relevant to your question.

To learn more about working with regulations, visit:

- Administrative Law Research by AJ Blechner Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 601 views this year

Case Basics

In many areas, finding relevant caselaw will comprise a significant part of your research. This Is particularly true in legal areas that rely heavily on common law principles.

Running Time: 3 minutes, 10 seconds.

Unpublished Cases

Up to 86% of federal case opinions are unpublished. You must determine whether your jurisdiction will consider these unpublished cases as persuasive authority. The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure have an overarching rule, Rule 32.1 Each circuit also has local rules regarding citations to unpublished opinions. You must understand both the Federal Rule and the rule in your jurisdiction.

- Federal and Local Rules of Appellate Procedure 32.1 (Dec. 2021).

- Type of Opinion or Order Filed in Cases Terminated on the Merits, by Circuit (Sept. 2021).

Each state also has its own local rules which can often be accessed through:

- State Bar Associations

- State Courts Websites

First Circuit

- First Circuit Court Rule 32.1.0

Second Circuit

- Second Circuit Court Rule 32.1.1

Third Circuit

- Third Circuit Court Rule 5.7

Fourth Circuit

- Fourth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Fifth Circuit

- Fifth Circuit Court Rule 47.5

Sixth Circuit

- Sixth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Seventh Circuit

- Seventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eighth Circuit

- Eighth Circuit Court Rule 32.1A

Ninth Circuit

- Ninth Circuit Court Rule 36-3

Tenth Circuit

- Tenth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eleventh Circuit

- Eleventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

D.C. Circuit

- D.C. Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Federal Circuit

- Federal Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Finding Cases

Headnotes show the key legal points in a case. Legal databases use these headnotes to guide researchers to other cases on the same topic. They also use them to organize concepts explored in cases by subject. Publishers, like Westlaw and Lexis, create headnotes, so they are not consistent across databases.

Headnotes are organized by subject into an outline that allows you to search by subject. This outline is known as a "digest of cases." By browsing or searching the digest you can retrieve all headnotes covering a particular topic. This can help you identify particularly important cases on the relevant subject.

Running Time: 4 minutes, 43 seconds.

Each major legal database has its own digest:

- Topic Navigator (Lexis)

- Key Digest System (Westlaw)

Start by identifying a relevant topic in a digest. Then you can limit those results to your jurisdiction for more relevant results. Sometimes, you can keyword search within only the results on your topic in your jurisdiction. This is a particularly powerful research method.

One Good Case Method

After following the steps above, you will have identified some relevant cases on your topic. You can use good cases you find to locate other cases addressing the same topic. These other cases often apply similar rules to a range of diverse fact patterns.

- in Lexis click "More Like This Headnote"

- in Westlaw click "Cases that Cite This Headnote"

to focus on the terms of art or key words in a particular headnote. You can use this feature to find more cases with similar language and concepts.

Ways to Use Citators

A citator is "a catalogued list of cases, statutes, and other legal sources showing the subsequent history and current precedential value of those sources. Citators allow researchers to verify the authority of a precedent and to find additional sources relating to a given subject." Citator , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

Each major legal database has its own citator. The two most popular are Keycite on Westlaw and Shepard's on Lexis.

- Keycite Information Page

- Shepard's Information Page

Making Sure Your Case is Still Good Law

This video answers common questions about citators:

For step-by-step instructions on how to use Keycite and Shepard's see the following:

- Shepard's Video Tutorial

- Shepard's Handout

- Shepard's Editorial Phrase Dictionary

- KeyCite Video Tutorial

- KeyCite Handout

- KeyCite Editorial Phrase Dictionary

Using Citators For

Citators serve three purposes: (1) case validation, (2) better understanding, and (3) additional research.

Case Validation

Is my case or statute good law?

- Parallel citations

- Prior and subsequent history

- Negative treatment suggesting you should no longer cite to holding.

Better Understanding

Has the law in this area changed?

- Later cases on the same point of law

- Positive treatment, explaining or expanding the law.

- Negative Treatment, narrowing or distinguishing the law.

Track Research

Who is citing and writing about my case or statute?

- Secondary sources that discuss your case or statute.

- Cases in other jurisdictions that discuss your case or statute.

Knowing When to Start Writing

For more guidance on when to stop your research see:

- Terminating Research, by Christina L. Kunz

Automated Services

Automated services can check your work and ensure that you are not missing important resources. You can learn more about several automated brief check services. However, these services are not a replacement for conducting your own diligent research .

- Automated Brief Check Instructional Video

Contact Us!

Ask Us! Submit a question or search our knowledge base.

Chat with us! Chat with a librarian (HLS only)

Email: [email protected]

Contact Historical & Special Collections at [email protected]

Meet with Us Schedule an online consult with a Librarian

Hours Library Hours

Classes View Training Calendar or Request an Insta-Class

Text Ask a Librarian, 617-702-2728

Call Reference & Research Services, 617-495-4516

This guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License .

You may reproduce any part of it for noncommercial purposes as long as credit is included and it is shared in the same manner.

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2023 2:56 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/law/researchstrategy

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Legal Research Fundamentals

- Research Strategy Tips

- Secondary Sources

The Different Types of Case Law Research

Popular case law databases, using secondary sources, any good case, from an annotated statute, ai and smart searching.

- Statutory Research

- Legislative History

- Administrative

- People, Firms, Witnesses, and other Analytics

- Transactional

- Non-Legal Resources

- Business Resources

- Foreign and International Law Resources This link opens in a new window

Generally, there are two types of case law research:

- Determining the case law that is binding or persuasive regarding a particular issue. Gathering and analyzing the relevant case law.

- Searching for a specific case that applies the law to a set of facts in a particular way.

These are two slightly different tasks. However, you can use many of the same case law search techniques for both of these types of questions.

This guide outlines several different ways to locate case law. It is up to you to determine which methods are most suitable for your problem.

When selecting a case law database, don't forget to choose the jurisdiction, time period, and level of court that is most appropriate for your purposes.

Note: Listed above are the databases that law students are most likely to use. It's possible that, once you leave law school, you will not have access to the same databases. Resources such as Fastcase or Casetext may be your go-to. For any database, take the time to familiarize yourself with the basic and advanced search functions.

Check out the Secondary Sources tab for information about how to locate a useful secondary source.

Remember: secondary sources take the primary source law and analyze it so that you don't have to. Take advantage of the work the author has already done!

What do we mean by 'any good case'?

A case that addresses the issue you care about. We can use the citing relationships and annotations found in case law databases to connect cases together based on their subject matter. You may find such a case from a secondary source, case law database search, or from a colleague.

How can we use one good case?

1. Court opinions typically cited to other cases to support their legal conclusions. Often these cited cases include important and authoritative decisions on the issue, because such decisions are precedential.

2. Commercial legal research databases, including Lexis, Westlaw, and Bloomberg, supplement cases with headnotes . Headnotes allow you to quickly locate subsequent cases that cite the case you are looking at with respect to the specific language/discussion you care about.

3. Links to topics or Key Numbers. Clicking through to these allows you to locate other cases with headnotes that fall under that topic. Once you select a suitable Key Number, you can also narrow down with keywords. A case may include multiple headnotes that address the same general issue.

4. Subsequent citing cases. By reading cases that have cited to the case you've started with, you can confirm that it remains "good law" and that its legal conclusions remain sound. You can also filter the citing references by jurisdiction, treatment, depth of treatment, date, and keyword, allowing you to focus your attention on the most relevant sub-set of cases.

5. Secondary sources! Useful secondary sources are listed in the Citing References. This can be a quick way to locate a good secondary source.

NOTE: Good cases may come in many forms. For example, a recent lower court decision might lead you to the key case law in that jurisdiction, while a higher court decision from a few years back might be more widely-cited and lead you to a wider range of subsequent interpretive authority (and any key secondary sources).

What is an annotated statute?

An annotated statute is simply a statute enhanced with editorial content. In Lexis and Westlaw, this editorial content provides the following:

Historical Notes about amendments to the statute. These are provided below the statutory text (Lexis) or under the History tab (Westlaw).

Case Notes provided either at the bottom of the page (Lexis) or under the Notes of Decisions tab (Westlaw). These are cases identified by the publisher as especially important or useful for illustrating the case law interpreting the statute. They are organized by issue and include short summaries pertaining to the holding and relevance are provided for each case.

Other Citing References allow you to locate all other material within Lexis and Westlaw that cite to the statute. This includes secondary sources (always useful) and all case law that cites to that specific section. You can narrow down by keywords, jurisdiction, publication status, etc. In Lexis, click the Shepard's link. In Westlaw, click the Citing References tab.

Lexis, Westlaw, and Bloomberg are all actively developing tools to lead you to cases more quickly. These include:

Westlaw's recommendations and WestSearch Plus. These will show up in the "Suggestions" option that appears when you start typing into the search bar.

Lexis Ravel View. When you search the case database in Lexis and click on the Ravel icon, you will see an interactive visualization of the citing relationships between the first 75 cases that appear in your results list, ranked by relevance.

Bloomberg's "Points of Law" feature in the Litigation Intelligence Center also allows users to visualize the citing relationships among cases meeting their search criteria.

- << Previous: Secondary Sources

- Next: Statutory Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 2:06 PM

- URL: https://law.upenn.libguides.com/researchfundamentals

11 Finding and Using Case Law

Learning goals.

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Identify and use many search techniques to find relevant case law.

- Identify and use free, non-subscription platforms to find relevant case law.

- Conduct case law research more confidently and efficiently.

Where Do You Find Cases?

Most people conduct case law research online. Several websites provide free access to case law: Google Scholar , state and federal court websites, Library of Congress (only United States Reports), the Government Printing Office website (federal court opinions), Findlaw , Justia , and Caselaw Access Project . Fastcase is available through some state law libraries (i.e. the State of Oregon Law Library website ) and with state Bar Association membership. Keep in mind that freely available websites and platforms will have few or no tools to help with searching, and some provide cases only from certain jurisdictions or for certain date ranges.

Commercial platforms such as Casetext, Westlaw, Lexis, and Bloomberg will provide more editorial enhancements to increase your efficiency and effectiveness in finding results.

A note about print sources

Some academic and public law libraries still have case reporters in print. Case reporters are multi-volume sets that publish case law for different jurisdictions. Each state has reporters for their courts. Regional reporters publish cases for states in a certain geographic region. For example, the Pacific Reporter series publishes state cases from Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Federal cases are published in West’s Federal Supplement (U.S. District Court), West’s Federal Reporter (Federal Court of Appeals), West’s Supreme Court Reporter (U.S. Supreme Court decisions), Lexis’s United States Supreme Court Reports, Lawyers’ ed. (U.S. Supreme Court decisions), and United States Reports (official version of U.S. Supreme Court decisions). The citations you see for cases refer to the volume number, the reporter name, the page number, the court and date of the decision.

How Do You Find Cases?

Finding case law is an important part of your research process for most legal issues. You probably practiced case law research frequently in first year legal research and writing courses. However, most students feel that they need additional practice because they want more confidence in their results and more efficiency in their searches. This chapter will focus on practicing different methods of finding cases:

- Using secondary sources.

- Using statutory annotations.

- Using one good case.

- Using an index (West’s Topic and Key Number system, Lexis’s Case Notes system).

- Using natural language and terms and connectors (Boolean) searching.

Using Secondary Sources

Chapter 9 discusses different types of secondary sources and how to use them to learn background information about your legal issue and find primary sources of law. To reiterate, when you are starting your research and reading secondary sources, you might come across citations to cases important to that legal topic or issue. You might have noted some cases at that point; but if not, you can circle back to secondary sources to find citations to cases that seem important now that you know a bit more about your issue.

Use Statutory Annotations

If you found an important statute in your research, you probably looked at the annotations to the statute to start finding cases. (See Chapter 10 ).

Use One Good Case

If you found a citation to a relevant case in a secondary source or a statute, you can use that case to find other cases. There are several ways to use a good case to find more cases:

- Look at the cases cited in the good case.

- On Westlaw or Lexis, use the headnote tools in the good case to find other cases.

- On Westlaw or Lexis, use the citators (Key Cite and Shepards) in the good case to find other cases.

- On Google Scholar, use the Cited By and How Cited links to find other cases.

Practice Activity

For the trademark issue, use google scholar to find any relevant cases. Compare your results to the cases you find on a subscription platform such as Westlaw or Lexis.

Use an Index

Westlaw and Lexis have indexing systems that allow you to use legal topics and sub-topics to find cases. On Westlaw, the Topic and Key Number system indexes all U.S. case law; on Lexis, the Topics system provides that service.

You can use the index in a few ways:

- In a case headnote, look at the corresponding index terms or Key Numbers and click on the links to find other cases categorized under that index term or number.

- On Westlaw, find Key Numbers under the Content Types tab and either browse or term search in that list of Key Numbers.

- On Lexis, find the Topics tab and search or browse.

- Use the Key Number or Topic as a search term when you are doing Boolean searching (see below discussion of Boolean searching).

Use Natural Language and Boolean Searching

Most students are adept at using natural language to search for cases. An example of a natural language search is what constitutes trademark infringement on a beer label? Search algorithms have improved, so most platforms you use for searching will produce relevant results. However, most law librarians and legal research and writing professors will advise you to use multiple methods and tools to ensure that your results are both thorough and accurate. In this section, you will learn more about using terms and connectors (also called Boolean language) to search effectively for cases. Boolean searching may seem time-consuming and awkward at first, but with practice, it will become easier.

Boolean Searching

When you encounter a website or research platform, look for a “search help” link, which will inform you of search language and other search tips for that platform. Although the connectors will vary in meaning based on the website or platform you are using, the following are some common terms and connectors:

The connectors are processed in a specific order in your searches. After the connector OR, proximity connectors are processed from narrowest “” to broadest, AND. Sometimes, you need to use parentheses to change the order. For example, frisk! OR search! /3 seiz! should be expressed like this to run properly: frisk! OR (search! /3 seiz!).

Suggested Activity:

In this activity, you will practice creating a Boolean (terms and connectors search) on the issue of trademark infringement in the context of beer labels and names. Try this search on several platforms, compare results, then revise your searches to try different combinations of terms.

Student added discussion and reflection questions

- Which case searching method do you feel most comfortable with?

- Have you used one type of searching method more than other in your research?

- What type of searching method is the most frustrating for you? Why?

Contribute a discussion or reflection question to this section.

Advanced Legal Research: Process and Practice Copyright © by Megan Austin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Library electronic resources outage May 29th and 30th

Between 9:00 PM EST on Saturday, May 29th and 9:00 PM EST on Sunday, May 30th users will not be able to access resources through the Law Library’s Catalog, the Law Library’s Database List, the Law Library’s Frequently Used Databases List, or the Law Library’s Research Guides. Users can still access databases that require an individual user account (ex. Westlaw, LexisNexis, and Bloomberg Law), or databases listed on the Main Library’s A-Z Database List.

- Georgetown Law Library

- Research Process

Case Law Research Guide

Introduction.

- Print Case Reporters

- Online Resources for Cases

- Finding Cases: Digests, Headnotes, and Key Numbers

- Finding Cases: Terms & Connectors Searching

Key to Icons

- Georgetown only

- On Bloomberg

- More Info (hover)

- Preeminent Treatise

Every law student and practicing attorney must be able to find, read, analyze, and interpret case law. Under the common law principles of stare decisis, a court must follow the decisions in previous cases on the same legal topic. Therefore, finding cases is essential to finding out what the law is on a particular issue.

This guide will show you how to read a case citation and will set out the sources, both print and online, for finding cases. This guide also covers how to use digests, headnotes, and key numbers to find case law, as well as how to find cases through terms and connectors searching.

To find cases using secondary sources, such as legal encyclopedias or legal treatises, see our Secondary Sources Research Guide . For additional strategies to find cases, like using statutory annotations or citators, see our Case Law Research Tutorial . Our tutorial also covers how to update cases using citators (Lexis’ Shepard’s tool and Westlaw’s KeyCite).

Basic Case Citation

A case citation is a reference to where a case (also called a decision or an opinion ) is printed in a book. The citation can also be used to retrieve cases from Westlaw and Lexis . A case citation consists of a volume number, an abbreviation of the title of the book or other item, and a page number.

The precise format of a case citation depends on a number of factors, including the jurisdiction, court, and type of case. You should review the rest of this section on citing cases (and the relevant rules in The Bluebook ) before trying to format a case citation for the first time. See our Bluebook Guide for more information.

The basic format of a case citation is as follows:

Parallel Citations

When the same case is printed in different books, citations to more than one book may be given. These additional citations are known as parallel citations .

Example: 265 U.S. 274, 68 L. Ed. 1016, 44 S. Ct. 565.

This means that the case you would find at page 565 of volume 44 of the Supreme Court Reporter (published by West) will be the same case you find on page 1016 of volume 68 of Lawyers' Edition (published by Lexis), and both will be the same as the opinion you find in the official government version, United States Reports . Although the text of the opinion will be identical, the added editorial material will differ with each publisher.

Williams Library Reference

Reference Desk : Atrium, 2nd (Main) Floor (202) 662-9140 Request a Research Consultation

Case law research tutorial.

Update History

Revised 4/22 (CMC) Updated 10/22 (MK) Links 07/2023 (VL)

- Next: Print Case Reporters >>

- © Georgetown University Law Library. These guides may be used for educational purposes, as long as proper credit is given. These guides may not be sold. Any comments, suggestions, or requests to republish or adapt a guide should be submitted using the Research Guides Comments form . Proper credit includes the statement: Written by, or adapted from, Georgetown Law Library (current as of .....).

- Last Updated: May 24, 2024 9:20 AM

- URL: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/cases

How Do I: Do Legal Research?: Case Law

- Legal Citations

- Citation of court opinions

- Citation of statutes

- Citation of regulations

- Articles and books

- Legal Forms

- Legal Advice

Federal Courts

- Nexis Uni™ This link opens in a new window Lets you search for a federal case by legal citation, on a specific topic, by a particular judge, or during a certain period of time. more... less... Nexis Uni™ has an intuitive interface that offers quick discovery across all content types, personalization features such as Alerts and saved searches and a collaborative workspace with shared folders and annotated documents.

- Google Scholar Search published opinions of U.S. federal district, appellate, tax and bankruptcy court cases since 1923; and U.S. Supreme Court cases since 1791.

- US Supreme Court official site Text of U.S. Reports from 1991 (502 U.S. __) to the present, including opinions, orders, and other materials; opinions from 2009 to the present; briefs; and transcripts/audio of arguments.

- US Circuit Courts of Appeal Links to official websites for Circuit Courts.

- US District Courts Links to opinions from some, but not all, District Courts (West Virginia is not included right now), some back to April 2004.

- Legal Information Institute (LII) - Cornell University Provides no-cost access to U.S. Supreme Court opinions.

- Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) An electronic public access service that allows users to obtain case and docket information online from federal appellate, district, and bankruptcy courts, and the PACER Case Locator.

State Courts

- Nexis Uni™ This link opens in a new window Lets you search for a state case by legal citation, on a specific topic, by a particular judge, or during a certain period of time. more... less... Nexis Uni™ has an intuitive interface that offers quick discovery across all content types, personalization features such as Alerts and saved searches and a collaborative workspace with shared folders and annotated documents.

- Google Scholar Search published opinions of U.S state appellate and supreme court cases since 1950.

- National Center for State Courts - Sate Court Web Sites Judicial branch links for each state, focusing on the administrative office of the courts, the court of last resort, any intermediate appellate courts, and each trial court level.

- West Virginia Judiciary - official site Opinions from the Supreme Court of Appeals, and information on the state judicial system.

What is "case law"?

Case law--also called 'opinions' or 'decisions'--comes from the written resolution of the issues in dispute, and is written by a judge or judges. It is not a jury verdict. (Juries decide facts; judges decide law.) Cases come from courts: trial courts, intermediate appellate courts, and appellate court of last resort, often called the “Supreme Court.” There are also specialized federal courts (Bankruptcy, Tax, Military Appeals, etc.) On the state level reported, or published, opinions generally come from the appellate courts, not the trial courts. On the federal level, some trial court (District Court) cases are reported. But, in a jury trial, there is nothing to “report” except a verdict.

Just to complicate things, for various reasons not all opinions from federal district and appeals courts are "published" in the official reporters. They may still be available in LexisNexis, WestLaw, or West's Federal Appendix , but are not generally considered to have precedential value.

Courts in the United States adhere to stare decisis , which means that courts respect and usually follow the precedent of previous decisions. However, a court does not have to follow a decision that is not binding precedent. Generally courts will follow the decisions of higher courts in their jurisdiction. Therefore the effect of a court's decision on other courts will depend both on the level of the court and its jurisdiction. A decision by the United States Supreme Court is binding precedent in all courts.

For example, a decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit would not be binding on the United States Supreme Court or courts from another circuit. However, it would be binding in all lower courts of the 4th Circuit (Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia).

- << Previous: Legal Citations

- Next: Citation of court opinions >>

- Last Updated: Jun 6, 2024 1:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.marshall.edu/basic_legal_research

👇 Recommended LLS Courses to Excel in this Opportunity

Home » Blogs, News, Advice » Legal Education » Legal Research Techniques for Finding Relevant Case Law

Legal Research Techniques for Finding Relevant Case Law

- Aug 8, 2023

- No Comments

Legal research is a systematic finding or ascertainment of law on an identified topic or in a given area. Additionally, it is a legal inquiry into the existing scholarship to advance the science of law.

Case law research and analysis is a prerequisite in the process of legal research. The method of acquiring this skill starts as soon as one embarks upon the journey of learning, studying, exploring and most importantly applying the law in a practical scenario.

Reading a case law, comprehending the rationale behind the decision and relating it to the present case to build a compelling and coherent argument is a skill every lawyer not only aspires to acquire. In order to become proficient and accomplished in their chosen profession, every lawyer must be skilled in finding relevant case laws through different means. One can learn several legal research techniques to find relevant case laws in legal databases.

Read on to find out several tools and techniques of Legal Research.

What are the different types of Legal Research?

Different types of research are crucial in case law research as they provide varied perspectives and information. Legal research helps identify relevant statutes, regulations, and precedents.

By utilizing these different research methods, researchers can obtain a comprehensive understanding of the legal landscape and make well-informed arguments or decisions in case law research. There are several legal research methodologies available for researchers to pursue their research.

1. Descriptive & Analytical Research

Descriptive research methodology focuses more on the “what” of the subject than the “why” of the research question. It is a description-based methodology that studies the characteristics of the population or phenomenon. The analytical research, however, uses the facts and information available to make a critical evaluation.

2. Qualitative & Quantitative Research

Qualitative legal research is a subjective method that relies on the researcher’s analysis of the controlled observations. In Quantitative Legal Research, one collects data from existing and potential data using sampling techniques like online surveys, polls, & questionnaires. The researcher can represent the outcomes of the quantitative study numerically.

3. Doctrinal & Empirical Research

In doctrinal legal research, the researcher analyses the existing statutory data to find the relevant answer to “What is the Law?” However, in empirical research, the researcher creates new data using several data collection methods and uses statistical tools to analyze it.

What is the Case Law Technique in Legal Research?

Case laws are the primary sources, i.e., the most original source, used in all legal research methodologies.

The case law technique in legal research methodology studies judicial opinions or decisions, and it is the technique of finding relevant legal precedents and principles. This is more challenging than it sounds because finding applicable case laws from legal databases is confusing and time-consuming, if the researcher is not well-versed with the tools.

Like legislation, case law can also be challenged and consequently change over time, as per the changing needs of the society. An earlier decision does not guarantee that it will always remain the law of the land.

Therefore, a lawyer must be skilled at finding, reading, and ascertaining the relevance, applicability and legal standing of any case law at a given point of time. . Thus, the importance of case law technique in legal research is quite significant as there can be no legal research without delving deep into judicial decisions.

How to Do Legal Research for Case Laws?

Before the time of the web, legal databases were in the form of multi-volume bulky books and digests. Researchers had to locate the cases manually with the help of case citations which was extremely time consuming. Though these periodicals are still available, online legal databases have overpowered them owing to their easy accessibility and time-saving tendency.

The Offline Tools for Legal Research

The researcher can locate case laws using the citations in printed law reporters. For example, the citation of a case is AIR 2017 SC 57, here the name of the Law Reporter in which the case law is published is AIR (All India Reporter), the year of the judgment is 2017, SC (Supreme Court) is the name of the Court, and the page number of the printed reporter on which the judgment can be found is 57.

The format of citation differs for every law reporter. Thus, the first step for locating the proper case law using citation is to decode the name of the law reporter.

The law reporters also categorize all the case laws. Thus, if the researcher does not know the case citation, they can find the case law as per its category.

The Online Tools for Legal Research

Using online tools for finding case laws is relatively easy. Even if the researcher does not know the name, citation, or year of the judgment, they can still find the same or similar judgments, thanks to these online tools’ intelligent features.

The only drawback is the majority of these tools require a heavy subscription fee which is not ideal for everyone.

What are the Methods of Locating Relevant Case Laws?

A researcher can locate relevant case laws if they know either of the following:

The identity of the case in law reporters, usually denoted in a combination of words & numbers.

For example: (1973) 4 SCC 225; AIR 1973 SC 1461

Case number

The official number the Court gives to a particular case.

For example: W.P.(C) 135 OF 1970

Name of the Parties

Either party’s name can be used for finding the case law.

For example: Petitioner’s name- Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalvaru

Respondent’s name- State of Kerala

Jurisdiction