- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

JRE Library

Books mentioned on the Joe Rogan Experience Podcast

We may earn an affiliate commission if you make a purchase after clicking on links from our site. Learn more

Benefits of Reading: Why You Should Read More

A large percentage of the population is missing out on the significant benefits of reading. According to Statistic Brain , about a third of U.S. high school graduates will never read another book after graduating and 42 percent of college students will never read another book after obtaining their degree.

Reading can improve your life in several ways leading to better well-being and mental health, personal growth, and a boost in confidence. These benefits will carry over to your school work, career and social life.

If you haven’t read a book in years or think reading is for nerds, perhaps you should reconsider. The following are just a few of the benefits associated with reading and the reasons why you should read more.

Reading expands your vocabulary

The more you read, the more words you’ll be exposed to. Consistent exposure to new words, learning their meanings and seeing the context in which they’re used will increase your mental dictionary. You will have more words available to use and more ways to use them in conversation and in writing. This will improve your ability to communicate effectively, allowing you to better articulate your thoughts and more accurately express how you feel. Most writers would attest that reading makes them better at writing.

Reading stimulates your brain

Your brain needs to be kept active and engaged in order to stay healthy. Reading is great exercise for the mind. From a neurobiological standpoint, reading is more demanding on the brain than processing speech and images. Mental stimulation from reading will improve your memory and learning capacity, keep your mind sharp by slowing cognitive decline as you age, and strengthen your brain against disease like Alzheimer’s or dementia.

Reading improves your memory

Reading creates new memories. With each of these new memories, your brain forms new connections between neurons called synapses and strengthens existing ones. As you read you are memorizing and recalling words, ideas, names, relationships, and plots. You’re essentially training your brain to retain new information.

Reading makes you smarter

Reading makes you smarter, it’s that simple. In the paper What Reading Does for the Mind by Anne E. Cunningham and Keith E. Stanovich, reading was found to compensate for average cognitive ability by building vocabulary and expanding general knowledge. Development of intelligence is not dependent on cognitive ability alone, it’s only one variable.

Reading increases knowledge

Reading is one of the primary ways to acquire knowledge. The knowledge you gain is cumulative and grows exponentially. When you have a strong knowledge base, it’s easier to learn new things and solve new problems. Reading a wide range of books will help expand your general knowledge. Specific knowledge can be acquired by taking a deep-dive on a subject or topic. Filling your mind with new facts, new information, and new ideas will make you a better conversationalist as you’ll always have something interesting to talk about.

Reading strengthens focus and concentration

In order to comprehend and absorb what you’re reading, you need to focus 100% of your attention on the words on the page. When you’re fully immersed in a book, you’ll be able to tune out external distractions and concentrate on the material in front of you. A consistent reading habit will strengthen your attention span which will carry over to other aspects of your life.

Reading enhances analytical thinking skills

You can develop your analytical thinking skills over time by consistently reading more books. Reading stimulates your brain, allowing you to think in new ways. Being actively engaged in what you’re reading allows you to ask questions, view different perspectives, identify patterns and make connections. Compared to other forms of communication, reading allows you more time to think by pausing to comprehend, reflect and make note of new thoughts and ideas.

Reading relieves stress

A 2009 study has shown that reading is more effective at reducing stress than listening to music, going for a walk, having a cup of coffee or tea, or playing video games. Reading for only six minutes is enough to slow your heart rate, ease tension in your muscles and lower stress hormones like cortisol. “Losing yourself in a book is the ultimate relaxation” according to Dr. David Lewis, who conducted the study.

Reading improves your imagination

Reading a good novel can transport you to another place, another time or another world. You can escape reality and temporarily forget about what’s bothering you. Exercising your imagination will improve your ability to visualize these new worlds, characters and perspectives. Opening your mind to new ideas and new possibilities makes you more creative and more empathetic.

Reading helps you sleep better

The addition of reading to your bedtime ritual will reduce stress and train your brain to associate reading with sleep. This will make it easier to fall asleep and allow you to enter into a deeper sleep. TV, smartphone and tablet screens emit blue light which disrupts your internal clock and negatively impacts the quantity and quality of your sleep. Avoid reading on a screen at least an hour before bed and read a physical book instead.

You might also like: How To Read More Books

- Episode List

- Upcoming Guests

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. Learn More

We are also a participant in the Onnit Affiliate Program. We will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking a link to Onnit.com. Get 10% Off Supplements at Onnit with Code: GETONNIT

6 Scientific Benefits of Reading More

By abigail fagan | may 21, 2024.

Reading transports us to worlds we would never see, introduces us to people we would never meet, and instills emotions we might never otherwise feel. It also provides an array of health benefits. Here are six scientific reasons you should be picking up more books .

Reading reduces stress.

Reading (especially reading books) may add years to your life., reading improves your language skills and knowledge of the world., reading enhances empathy., reading boosts creativity and flexibility., reading can help you transform as a person..

In 2009, scientists at the University of Sussex in the UK assessed how different activities lowered stress by measuring heart rate and muscle tension. Reading a book or newspaper for just six minutes lowered people’s stress levels by 68 percent—a stronger effect than going for a walk (42 percent), drinking a cup of tea or coffee (54 percent), or listening to music (61 percent). According to the authors, the ability to be fully immersed and distracted is what makes reading the perfect way to relieve stress.

A daily dose of reading may lengthen your lifespan. A team at Yale University followed more than 3600 adults over the age of 50 for 12 years. They discovered that people who reported reading books for 30 minutes a day lived nearly two years longer than those who read magazines or newspapers. Participants who read more than 3.5 hours per week were 23 percent less likely to die, and participants who read less than 3.5 hours per week were 17 percent less likely to die. “The benefits of reading books include a longer life in which to read them,” the authors wrote.

In the 1990s, reading pioneer Keith Stanovich and his colleagues conducted dozens of reading studies to assess the relationship between cognitive skills, vocabulary, factual knowledge, and exposure to certain fiction and nonfiction authors. They used the Author Recognition Test (ART), which is a strong predictor of reading skill. Stanovich tells Mental Floss that the average result of these studies was that avid readers, as measured by the ART, had around a 50 percent larger vocabulary and 50 percent more fact-based knowledge.

Reading both predicts and contributes to those skills, according to Donald Bolger , a human development professor at the University of Maryland who researches how the brain learns to read. “It’s like a snowball effect,” he tells Mental Floss. “The better you are at reading, the more words you learn. The more words you learn, the better you are at reading and comprehending—especially things that would have been outside your domain of expertise.”

For a 2013 Harvard study, a group of volunteers either read literary fiction (such as “ Corrie ” by Alice Munro), popular fiction (such as “ Space Jockey ” by Robert Heinlein), nonfiction (such as “How the Potato Changed the World” by Charles Mann), or nothing. Across five experiments, those who read literary fiction performed better on tasks like predicting how characters would act and identifying the emotion encoded in facial expressions. These speak to the ability to understand others’ mental states, which scientists call Theory of Mind.

“If we engage with characters who are nuanced, unpredictable, and difficult to understand, then I think we’re more likely to approach people in the real world with an interest and humility necessary for dealing with complex individuals,” study lead author David Kidd , a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, tells Mental Floss.

“In our real lives, we often feel like we have to make a decision, and therefore we close our mind to information that could eventually help us,” says Maja Djikic , a psychologist at the University of Toronto. “When we read fiction, we practice keeping our minds open because we can afford uncertainty.”

Djikic came to that conclusion after she conducted a study in which 100 people were assigned to read a fictional story or a nonfiction essay. The participants then completed questionnaires intended to assess their level of cognitive closure, which is the need to reach a conclusion quickly and avoid ambiguity in the decision-making process. The fiction readers emerged as more flexible and creative than the essay readers—and the effect was strongest for people who read on a regular basis.

It’s not often that we can identify moments when our personality changes and evolves, but reading fiction may help us do just that. The same University of Toronto research team asked 166 people to fill out questionnaires regarding their emotions and key personality traits, based on the widely used Big Five Inventory, which measures extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability/neuroticism, and openness. Then half of the group read Anton Chekhov’s short story “The Lady with the Toy Dog,” about a man who travels to a resort and has an affair with a married woman. The other half of the group read a similar nonfiction version presented as a report from divorce court. Afterwards, everyone answered the same personality questions they’d answered previously—and many of the fiction readers’ responses had significantly changed. They saw themselves differently after reading about others’ fictional experience. The nonfiction readers didn’t undergo this shift in self-reflection.

“As you identify with another person, a protagonist in the story, you enter into a piece of life that you wouldn’t otherwise have known. You have emotions or circumstances that you wouldn’t have otherwise understood,” Keith Oatley , a University of Toronto psychologist and one of the study’s authors, tells Mental Floss. Imagining new experiences creates a space in which readers can grow and change.

Discover More Articles About Books and Reading:

A version of this story ran in 2018; it has been updated for 2024.

Reading is Good Habit for Students and Children

500+ words essay on reading is good habit.

Reading is a very good habit that one needs to develop in life. Good books can inform you, enlighten you and lead you in the right direction. There is no better companion than a good book. Reading is important because it is good for your overall well-being. Once you start reading, you experience a whole new world. When you start loving the habit of reading you eventually get addicted to it. Reading develops language skills and vocabulary. Reading books is also a way to relax and reduce stress. It is important to read a good book at least for a few minutes each day to stretch the brain muscles for healthy functioning.

Benefits of Reading

Books really are your best friends as you can rely on them when you are bored, upset, depressed, lonely or annoyed. They will accompany you anytime you want them and enhance your mood. They share with you information and knowledge any time you need. Good books always guide you to the correct path in life. Following are the benefits of reading –

Self Improvement: Reading helps you develop positive thinking. Reading is important because it develops your mind and gives you excessive knowledge and lessons of life. It helps you understand the world around you better. It keeps your mind active and enhances your creative ability.

Communication Skills: Reading improves your vocabulary and develops your communication skills. It helps you learn how to use your language creatively. Not only does it improve your communication but it also makes you a better writer. Good communication is important in every aspect of life.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Increases Knowledge: Books enable you to have a glimpse into cultures, traditions, arts, history, geography, health, psychology and several other subjects and aspects of life. You get an amazing amount of knowledge and information from books.

Reduces Stress: Reading a good book takes you in a new world and helps you relieve your day to day stress. It has several positive effects on your mind, body, and soul. It stimulates your brain muscles and keeps your brain healthy and strong.

Great Pleasure: When I read a book, I read it for pleasure. I just indulge myself in reading and experience a whole new world. Once I start reading a book I get so captivated I never want to leave it until I finish. It always gives a lot of pleasure to read a good book and cherish it for a lifetime.

Boosts your Imagination and Creativity: Reading takes you to the world of imagination and enhances your creativity. Reading helps you explore life from different perspectives. While you read books you are building new and creative thoughts, images and opinions in your mind. It makes you think creatively, fantasize and use your imagination.

Develops your Analytical Skills: By active reading, you explore several aspects of life. It involves questioning what you read. It helps you develop your thoughts and express your opinions. New ideas and thoughts pop up in your mind by active reading. It stimulates and develops your brain and gives you a new perspective.

Reduces Boredom: Journeys for long hours or a long vacation from work can be pretty boring in spite of all the social sites. Books come in handy and release you from boredom.

Read Different Stages of Reading here.

The habit of reading is one of the best qualities that a person can possess. Books are known to be your best friend for a reason. So it is very important to develop a good reading habit. We must all read on a daily basis for at least 30 minutes to enjoy the sweet fruits of reading. It is a great pleasure to sit in a quiet place and enjoy reading. Reading a good book is the most enjoyable experience one can have.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Would you like to explore a topic?

- LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL

Or read some of our popular articles?

Free downloadable english gcse past papers with mark scheme.

- 19 May 2022

The Best Free Homeschooling Resources UK Parents Need to Start Using Today

- Joseph McCrossan

- 18 February 2022

How Will GCSE Grade Boundaries Affect My Child’s Results?

- Akshat Biyani

- 13 December 2021

Benefits of Reading: Positive Impacts for All Ages Everyday

- May 26, 2023

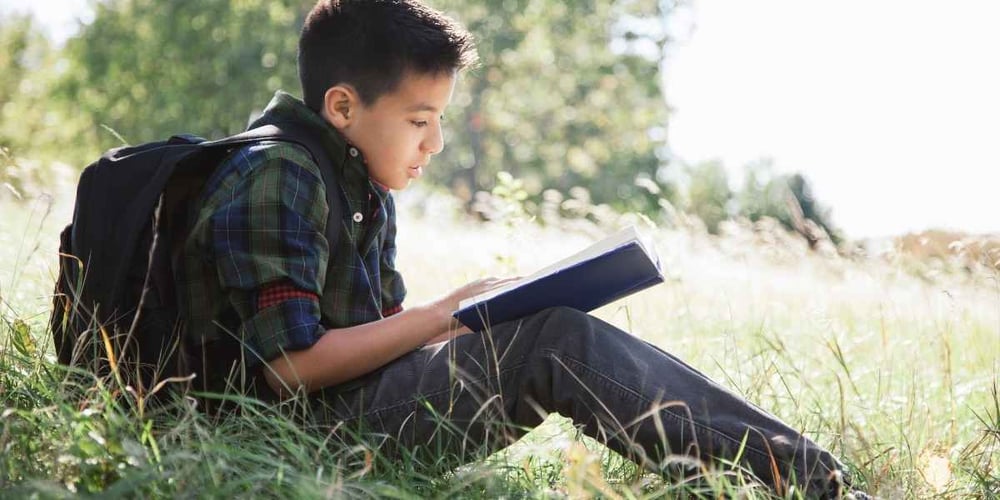

From apps to social media to Netflix to video games, there are so many ways to fill your free time that it can be hard to decide what to do. It’s also easy to overlook one of the most fulfilling and beneficial pastimes ever created. Let’s look at the main benefits of reading and how you can highlight them to your child.

What are the main benefits of reading books?

Benefits of reading before bed.

- Benefits of reading to children

Benefits of reading out loud

Why is reading important.

- Does listening to audiobooks have the same benefits?

What are the benefits of reading fiction?

What are the benefits of reading poetry, it’s a gym for your brain.

The act of reading is a remarkable mental feat and reading comprehension uses a lot of your brain power. When you’re thumbing through a novel you’re building a whole world of people, places and events in your mind and remembering it all as you follow the story. This gives your imagination and memory a thorough workout and strengthens networks in various other parts of your brain too. 💪

If you’re reading a non-fiction book you’re also getting an in-depth experience of a subject full of facts and details that you need to hold in your mind to follow the arguments of the writer.

It’s well known that your memory improves with use as new memories are created and connected to older ones, making them stronger and easier to recall. Scientists have even found that the other parts of the brain activated by reading can continue to improve days after you’ve stopped reading, meaning even just a little bit of reading can go a long way.

It improves your focus

From Insta stories to tweets to TikTok videos, information is being packaged into ever smaller chunks and researchers believe our attention spans are getting shorter. However, being able to concentrate on one thing for long periods and ignore distractions is essential for school and for work. Reading is an excellent way to improve your concentration skills and the more you read, the better you’ll be able to focus. 🔍

It expands your vocabulary

Reading expands your vocabulary more than any other activity. A rich vocabulary allows you to understand the world in a more sophisticated way. Reading is also great for your grammar skills and lets you communicate your thoughts and ideas more accurately in all areas of your life.

It’s an education

Reading is the key to knowledge. Reading non-fiction books means you can learn about any subject you choose in as much detail as you want. Fiction allows you to learn about how other people all over the world live their lives and to put yourself in their shoes. This is a great way to improve your empathy and learn to approach other people with an open mind.

It helps your problem-solving skills

Reading fiction is also fantastic preparation to learn how to solve various types of problems you may not yet have encountered in your own life. You get the chance to follow the characters through all kinds of situations and find out how they deal with challenges big and small.

Maybe they make the right choices or maybe they don’t, either way, the writer has put a lot of thought and consideration into their story and you can always learn something from a character’s experiences. 🧩

It’s good therapy

Reading about difficult situations characters or real people experience can be hugely beneficial as well. It can be useful to read both fiction and non-fiction books about something you’re going through. Books can act as a type of therapy and help you to feel less alone in your situation.

This bibliotherapy has proven effective in helping people deal with issues such as depression or other mood disorders. The NHS even prescribes books to help people through its Reading Well programme!

Books offer the best value-for-money entertainment anywhere! There’s no expensive equipment to buy, no tickets to pay for and no monthly subscription fee. All you need is a library card for your local branch and you’re good to go!

Your nearest library probably has tens of thousands of different books available, so you’re sure to find a title to hook you. If they don’t have something in particular you're looking for, you can even ask the librarian to order it from another library.

Some libraries even offer ebooks on loan which you can add to your ereader or tablet 🏛️

It’ll inspire your child

If your children regularly see you reading you’ll be setting a good example. Children tend to copy what they see their parents do and they’ll soon be joining you storybook in hand for some quiet time you can enjoy together.

It’s great for stress

It’s not most people’s first idea of a relaxation technique, but reading does an awesome job of helping you manage stress. According to research, reading can lead to a lower heart rate and blood pressure and a calmer mind and just six minutes of reading can bring your stress levels down by more than 66%.

It helps you live longer!

If you still need another reason to commit yourself to read more, how about this: reading can actually help you live longer! Researchers discovered that those who read for half an hour a day had a 23% chance of living longer than people who didn’t read very much. In fact, readers lived around two years longer than non-readers! 🌳

So, if we’ve convinced you that you and your family need more reading in your lives, when is the best time to do it? Well, reading at bedtime allows you to kill two birds with one stone.

It helps you get a good night’s sleep

Despite its importance, many of us don’t follow good sleep hygiene and spend the hours before bedtime staring at screens big and small, leading to difficulty falling asleep and affecting the quality of our slumber. The NHS found that one in three of us experience poor sleep.

Choose to read an actual book before bedtime instead of checking your social media or watching Netflix and you can look forward to a better night’s rest. Reading fiction is a good way of relaxing the body and calming your mind and preparing for bed and has been shown to be as relaxing as meditation. 💤

It calms your child

If you treat your child to story time and read to them just before they go to bed you’ll discover that it’s perfect for calming them down and getting them in the right mood for sleep. As a bonus, they’ll get used to sitting still and concentrating on one thing for a long time.

Benefits of reading to children

Children can eventually enjoy all the benefits of reading mentioned above but whether they are too small to read much themselves or they just enjoy listening to you tell them a story, they can get some extra value out of the experience if you read to them regularly yourself.

It gives them a love of learning

If you start by reading to your child you can get them hooked on books and start a habit that will last them throughout their lives and repay your investment over and over again. Children who learn to read for pleasure will go on to enjoy greater academic success throughout their education according to research. 👩🏽🎓

It gives them a head-start

Even if your little one is a toddler who isn’t ready to start reading storybooks by themselves, you can give their literacy skills an early boost and teach them to read by reading to them yourself. They might not understand everything but they’ll pick up enough to get the idea. Let them see the words on the page as you read and encourage them to turn the page when you get to the last word.

By reading to them you’ll be helping them follow the natural rhythms of language, practise their listening skills and expose them to vocabulary they might not get to hear in their day-to-day lives.

It brings you together

Time spent reading to your child is a wonderful chance to create some beautiful, cosy, loving memories together and strengthen your bond. It will become something like a regular adventure you and your child can look forward to doing together and will remember all your lives. 👩👦

It also gives you lots to talk about later and you can have enjoyable discussions about the characters, plots, dilemmas and mysteries you discover during your reading time.

Even when your child starts to read for themselves, you don’t need to stop your shared storytime. You can swap it up, with them taking on the role of the reader as you listen or you can take turns reading to each other.

You’ve probably been taught that the best method of reading is in silence. However, research has found that quiet reading isn’t actually always the better option and that there are in fact some benefits of reading out loud. 📢

It helps you understand

It turns out that speaking as you read can help you understand texts better. You probably read aloud more than you realise. If you’ve ever received a slightly convoluted message or email or you’ve tried to read confusing legal jargon, you’ve probably found yourself repeating the words out loud to more clearly understand what was meant. ✅

It helps you remember

Or perhaps you’ve tried to memorise a phone number or the lines of a speech and you automatically started to say the information aloud to help you remember.

Psychologists call this the “production effect” and have discovered that these tactics do actually help people remember things more easily, especially children. 📚

Research from Australia showed that children who were told to read out loud recognized 17% more words compared to children who were asked to read silently. In another study, adults were able to identify 20% more words they had read aloud.

The theory is that because reading aloud is an active process it makes words more distinctive, and so easier to remember. 🧠

Why read?

Reading is the most effective way to get information about almost everything and is the key ingredient in learning for school, work and pleasure. On top of this, reading boosts imagination, communication, memory, concentration, and empathy. It also lowers stress levels and leads to a longer life.

Does listening to audiobooks have the same benefits as reading books?

It can be hard to concentrate for a long time and the experience of reading. With a real book you can quickly scan your eyes back over the page to reread what you’ve missed, this isn’t so easy with an audiobook. A psychology study showed that students who read material did 28% better on a test than those who heard the same material as a podcast.

Reading fiction is a useful way to develop your empathy, social skills and emotional intelligence. Fictional stories allow you to put yourself in other people's shoes and see things from various perspectives. In fact, brain scans show that many of the parts of the brain you use to interact with other people are also activated when you’re reading fiction.

Poetry is the home of the most creative, imaginative and beautiful examples of language and allows you to connect those powerful lines to real emotions all of us feel. Poetry is also efficient and a good poet can reveal deep ideas with a simple phrase. Reading poetry can also inspire your creativity and write some expressive verse of your own!

Reading is something most of us have been doing all our lives and as a result, we can easily take it for granted, but it’s a great all-around experience for your mind and spirit. So, it's really worth digging out your library card and finding books you and your child can read together.

If your child is having problems with reading, here at GoStudent we have education experts on standby to give you and them a helping hand in improving their literacy skills or any other learning challenges they need support with. Schedule a free trial lesson with GoStudent today!

Popular posts

- By Guy Doza

- By Joseph McCrossan

- In LEARNING TRENDS

- By Akshat Biyani

4 Surprising Disadvantages of Homeschooling

- By Andrea Butler

What are the Hardest GCSEs? Should You Avoid or Embrace Them?

- By Clarissa Joshua

1:1 tutoring to unlock the full potential of your child

More great reads:.

15 of the Best Children's Books That Every Young Person Should Read

- By Sharlene Matharu

- March 2, 2023

- 10 min read

Ultimate School Library Tips and Hacks

- By Natalie Lever

- March 1, 2023

How to Write the Perfect Essay: A Step-By-Step Guide for Students

- By Connie Kulis-Page

- June 2, 2022

Book a free trial session

Sign up for your free tutoring lesson..

- Utility Menu

- ARC Scheduler

- Student Employment

Some sample reading goals:

To find a paper topic or write a paper;

To have a comment for discussion;

To supplement ideas from lecture;

To understand a particular concept;

To memorize material for an exam;

To research for an assignment;

To enjoy the process (i.e., reading for pleasure!).

Seeing Textbook Reading in a New Light Students often come into college with negative associations surrounding textbook reading. It can be dry, dense, and draining; and in high school, sometimes we're left to our textbooks as a last resort for learning material.

A supportive resource : In college, textbooks can be a fantastic supportive resource. Some of your faculty may have authored their own for the specific course you're in!

Textbooks can provide:

A fresh voice through which to absorb material. Especially when it comes to challenging concepts, this can be a great asset in your quest for that "a-ha" moment.

The chance to “preview” lecture material, priming your mind for the big ideas you'll be exposed to in class.

The chance to review material, making sense of the finer points after class.

A resource that is accessible any time, whether it's while you are studying for an exam, writing a paper, or completing a homework assignment.

Textbook reading is similar to and different from other kinds of reading . Some things to keep in mind as you experiment with its use:

Is it best to read the textbook before class or after?

Active reading is everything, apply the sq3r method., don’t forget to recite and review..

If you find yourself struggling through the readings for a course, you can ask the course instructor for guidance. Some ways to ask for help are: "How would you recommend I go about approaching the reading for this course?" or "Is there a way for me to check whether I am getting what I should be out of the readings?"

Marking Text

Marking text – making marginal notes – helps with reading comprehension by keeping you focused and facilitating connections across readings. It also helps you find important information when reviewing for an exam or preparing to write an essay. The next time you’re reading, write notes in the margins as you go or, if you prefer, make notes on a separate sheet of paper.

Your marginal notes will vary depending on the type of reading. Some possible areas of focus:

What themes do you see in the reading that relate to class discussions?

What themes do you see in the reading that you have seen in other readings?

What questions does the reading raise in your mind?

What does the reading make you want to research more?

Where do you see contradictions within the reading or in relation to other readings for the course?

Can you connect themes or events to your own experiences?

Your notes don’t have to be long. You can just write two or three words to jog your memory. For example, if you notice that a book has a theme relating to friendship, you can just write, “pp. 52-53 Theme: Friendship.” If you need to remind yourself of the details later in the semester, you can re-read that part of the text more closely.

Accordion style

If you are looking for help with developing best practices and using strategies for some of the tips discussed above, come to an ARC workshop on reading!

Register for ARC Workshops

- Assessing Your Understanding

- Building Your Academic Support System

- Common Class Norms

- Effective Learning Practices

- First-Year Students

- How to Prepare for Class

- Interacting with Instructors

- Know and Honor Your Priorities

- Memory and Attention

- Minimizing Zoom Fatigue

- Note-taking

- Office Hours

- Perfectionism

- Scheduling Time

- Senior Theses

- Study Groups

- Tackling STEM Courses

- Test Anxiety

- Our Mission

The Benefits of Reading for Pleasure

Reading for fun has numerous lifelong benefits, and we have ideas for how you can promote this habit among your students.

Why don’t students read? Most teachers have the goal of promoting students’ lifelong love of reading. But why? And what can teachers and parents and librarians do to promote pleasure reading?

In our book Reading Unbound , Michael Smith and I argue that promoting pleasure reading is a civil rights issue. Data from major longitudinal studies show that pleasure reading in youth is the most explanatory factor of both cognitive progress and social mobility over time (e.g., Sullivan & Brown, 2013 [PDF]; Guthrie, et al, 2001 ; and Kirsch, et al, 2002 [PDF]). Pleasure reading is a more powerful predictor than even parental socioeconomic status and educational attainment.

So if we want our students to actualize their full potential as human beings and their capacity to participate in a democracy, and if we want to overcome social inequalities, we must actively promote pleasure reading in our schools, classrooms, and homes.

The Pleasures of Reading

Pleasure reading can be defined as reading that is freely chosen or that readers freely and enthusiastically continue after it is assigned. Our students (like all other human beings!) do what they find pleasurable. You get good at what you practice, and then outgrow yourself by deliberately developing new related interests and capacities.

In our study, we found that reading pleasure has many forms, and that each form provides distinct benefits:

- Play pleasure/immersive pleasure is when a reader is lost in a book. This is prerequisite to experiencing all the other pleasures; it develops the capacity to engage and immerse oneself, visualize meanings, relate to characters, and participate in making meaning.

- Intellectual pleasure is when a reader engages in figuring out what things mean and how texts have been constructed to convey meanings and effects. Benefits include developing deep understanding, proactivity, resilience, and grit.

- Social pleasure is when the reader relates to authors, characters, other readers, and oneself by exploring and staking one’s identity. This pleasure develops the capacity to experience the world from other perspectives; to learn from and appreciate others distant from us in time, space, and experience; and to relate to, reciprocate with, attend to, and help others different from ourselves.

- Work pleasure is when the reader develops a tool for getting something functional done—this cultivates the transfer of these strategies and insights to life.

- Inner work pleasure is when the reader imaginatively rehearses for her life and considers what kind of person she wants to be and how she can connect to something greater or strive to become something more. When our study participants engaged in this pleasure, they expressed and developed a growth mindset and a sense of personal and social possibility.

Taken together, these pleasures explain why pleasure reading promotes cognitive progress and social possibility, and even a kind of wisdom and wholeness, and, in a larger sense, the democratic project.

Promoting the Pleasures of Reading

We need to help less engaged readers experience these same pleasures. That is our study’s major takeaway: We must make all five pleasures central to our teaching. We need to name them, actively model them, and then assist students to experience them.

To promote play pleasure, use drama techniques like revolving role play, in-role writing, and hot seating of characters in order to reward all students for entering and living through story worlds and becoming or relating to characters in the way that highly engaged readers do.

To promote intellectual pleasure, frame units as inquiry, with essential questions. Read a book for the first time along with your students—figure it out along with them, modeling your fits and starts and problems through think-alouds and discussion. Or pair an assigned reading with self-selected reading from a list, or a free reading choice that pertains to the topic. Use student-generated questions for discussion and sharing. Use discussion structures like Socratic seminar that make it clear there is no teacherly agenda to fulfill as far as topics or insights to achieve.

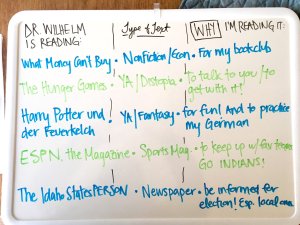

To promote social pleasure, be a fellow reader with students. Put a sign on your door: “Dr. Wilhelm is reading _____.” Read one of their favorite books. Foster peer discussion of reading and response in pairs, triads, small groups, literature circles, book clubs, etc. Do group projects with reading that are then shared and even archived. Have a free reading program and promote books through book talks, online reviews, etc.

To foster work pleasure, use inquiry contexts and work toward culminating projects, including service and social action projects.

To foster inner work pleasure, engage students in imaginative rehearsals for living, inquiry geared toward current and future action, or inquiry for service. Have students think as authors making choices and plan scenarios for characters in dilemmas or those trying to help the characters. Write to the future or to a future self.

Make no mistake, the next-generation standards worldwide require profound cognitive achievements. Meeting such standards and the demands of navigating modern life will require student effort and the honing of strategies over time. Promoting the power of pleasure reading is a proven path there.

Reading as a source of knowledge

- Open access

- Published: 13 December 2018

- Volume 198 , pages 723–742, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- René van Woudenberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1169-6539 1

11k Accesses

3 Citations

29 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper argues that reading is a source of knowledge. Epistemologists have virtually ignored reading as a source of knowledge. This paper argues, first, that reading is not to be equated with attending to testimony, and second that it cannot be reduced to perception. Next an analysis of reading is offered and the source of knowledge that reading is further delineated. Finally it is argued that the source that reading is, can be both transmissive and generative, is non-basic, once was a non-essential but has become essential for many people, and can be unique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knowing as Simply Being Correct

Cook Wilson on knowledge and forms of thinking

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

I shall be arguing that reading is a source of knowing or warranted belief. Footnote 1 Perception, memory, consciousness and reason have standardly been called sources of knowledge (e.g. Chisholm 1977 : p. 122; Audi 1998 : part I). As of lately testimony has been explicitly added to this illustrious list (Coady 1992 : p. 6; Plantinga 1993 : p. 77; Audi 1998 : ch. 5; Lackey 2008 ; McMyler 2011 : pp. 4–5; Faulkner 2011 ; Gelfert 2014 ). Footnote 2 One wonders, however, why certain items that intuitively seem to qualify as a “source of knowledge”, such as reading, Footnote 3 occur on no epistemologist’s list of sources. Footnote 4

One wonders, for it has been suggested that a source of knowledge is that “from” which knowledge or warranted belief “comes”. (Moser et al. 1998 : p. 101; Audi 2002 : p. 82) It has also been suggested that a source of knowledge is “roughly, something in the life of a knower … that yields belief constituting knowledge” (Audi 2002 : p. 72). Given these suggestions, reading would seem to qualify as a source, as much knowledge that we have does “come from” reading. In this paper I discuss two possible explanations why epistemologists in the broadly analytic tradition have never considered reading as a source of knowledge, and argue that both are unsatisfactory. The first explanation is that reading is just one form of attending to testimony and hence requires no special attention (Sect. 1 ), the second that reading is a special case of perception and hence requires no special attention (Sect. 2 ). In Sect. 3 I offer an analysis of reading, while Sect. 4 gives a richer delineation of the source of knowledge that is associated with reading. Section 5 applies a number of epistemological distinctions that can be found in the literature to this source, so as to further delineate its nature. The final section summarizes the main conclusions.

2 Reading isn’t necessarily attending to testimony

The first possible explanation that I want to consider as to why reading isn’t considered as a separate source of knowledge is that reading is just an instantiation of the more general phenomenon of acquiring knowledge through testimony. The idea is that acquiring knowledge through testimony comes in a variety of forms of which reading is one, listening another, and that whatever epistemically relevant can be said about acquiring knowledge through testimony, carries over to reading. Hence, so the explanation goes, there is no need for epistemologists to pay special attention to reading.

In order to be able to evaluate this explanation, we need to be clear about what testimony is. Various accounts of testimony have been offered. I will discuss three such accounts and argue that on each of them knowledge acquired through reading is not identical with knowledge acquired through testimony. C.A.J. Coady has offered the following account of ‘natural’ testimony (as opposed to ‘formal’ testimony of the sort that is offered in court rooms):

A speaker S testifies by making some statement p, iff (1) S’s stating that p is evidence that p and is offered as evidence that p (2) S has the relevant competence, authority, or credentials to state truly that p (3) S’s statement that p is relevant to some disputed or unresolved question (which may or may not be whether p?) and is directed to those who are in need of evidence on the matter. (Coady 1992 : p. 42)

There are two points I should like to make about Coady’s account. First, given this account of testimony there are many cases of acquiring knowledge or warranted belief through reading that just aren’t cases of acquiring knowledge or warranted belief through testimony . Suppose you open a copy of Graham Greene’s A Gun for Hire , read the opening sentence “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven”, and thereby acquire the knowledge that Greene’s novel opens with that sentence, then you aren’t acquiring this knowledge on the basis of Coadyan testimony, for condition (1) isn’t satisfied: Greene doesn’t offer his statement as evidence that murder didn’t mean much to Raven; nor is condition (3) satisfied: Greene’s opening sentence isn’t relevant to some disputed or unresolved question, and it isn’t directed to people who are in need of evidence on the matter of Raven. And this isn’t an isolated case. All of the following are things one may come to know, in the contexts sketched between square brackets, through reading, without that knowledge qualifying as being acquired on the basis of Coadyan testimony (for ease of future reference I include the example just given):

That the first line Graham Greene’s novel reads “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven” [you have opened the book that you know is written by Graham Greene, and have read the opening sentence]

That the text contains a lot of metaphorical expressions [you have read the text and noticed this fact]

That the poem is a sonnet [you are familiar with the formal characteristics of a sonnet]

That the book is humorous [the writer doesn’t say or imply so much, but upon reading you find yourself laughing]

That the article contains an invalid argument [you followed the argument on offer, and notice that the conclusions doesn’t follow from the argument]

That the review is based on a misunderstanding of the book [you know the book very well]

That the book is a warning call not to harbor grudges in one’s heart [this point is not explicitly stated, but from the development of the book’s main character you conclude so much]

That the author of the novel assumes that p [not that he says this explicitly, but it is the inevitable though unobvious conclusion you must draw, given the points that the author does explicitly make]

That the author is intimately familiar with the Scottish Enlightenment [you are an historian that specializes in that period, and even though the book is not a history book, it contains so many adequate allusions to the Scottish Enlightenment, that the conclusion forces itself upon you]

That what the Dutch did in the Caribbean was wrong [the reader is offered a ‘clean’ neutral statement of facts and figures without the author making any moral or evaluative statement whatsoever]

That the square root of 2 is not a rational number [you have followed and comprehended the proof that was offered, and judged it, rightly, to be sound]

The point of this list is not that these things can not be known through Coadyan testimony. For surely there are contexts, others than the ones indicated between the square brackets, in which one can and does come to know the things described on the list on the basis of Coadyan testimony. Knowledge of all the propositions listed can be acquired when Coady’s three conditions are satisfied. Rather, the point of the list is that one can come to know these things through reading in a way that does not qualify as believing on the basis of Coadyan testimony, viz. in the contexts that are sketched between the square brackets. For in none of these cases are Coady’s three conditions jointly satisfied. Condition (1) is not satisfied in any of the cases on the list, as the propositions specified aren’t offered as evidence. Neither is condition (2) satisfied: the sketches of the contexts provide no indication about the authors’ competence, credentials, and authority. Nor is condition (3) satisfied, as the propositions aren’t relevant to some disputed or unresolved question, nor are they directed to people who are in need of evidence on the matters at hand. But even though Coady’s conditions aren’t jointly satisfied, and so knowing the specified propositions in the contexts as sketched can not be considered as knowledge based on Coadyan testimony, knowing the specified propositions (in the contexts specified) does qualify as knowledge acquired through reading. From which it follows that reading isn’t coextensive with attending to Coadyan testimony.

My second point about Coady’s account is that, as Jennifer Lackey has argued, it doesn’t capture what we ordinarily take testimony to be, as there are clear cases of testimony that don’t satisfy (1), (2) and/or (3). Statements in posthumously published private journals and diaries that were never intended by their writers to be read by others, fail Coadyan condition (1): they aren’t offered as evidence, nor need they be relevant to some disputed question. But now suppose, to adapt an example from Lackey ( 2008 : p. 18), you read Sylvia Plath’s posthumously published diary in which she says that she was regularly deeply depressed. Then you likely come to know that she was regularly deeply depressed. When asked what the epistemic source of your knowledge is, the intuitively correct answer is that it is testimony. For you don’t know this through sense perception (you haven’t seen her depressed), nor through memory (you don’t remember it), or reason (you don’t derive this as a conclusion from a number of facts that you are aware of) or introspection or any combination of these sources. You acquired this knowledge from an expression of Plath’s own thoughts—her thoughts are, for you, testimony. This example also shows that Coady’s condition (3) isn’t necessary for someone’s testifying: after reading her diary, you will know through Plath’s own testimony that she was regularly depressed, but you had no evidential needs.

As Lackey ( 2008 : p. 17) has also argued, Coady’s condition (2) isn’t necessary for what we ordinarily take testimony to be either. This condition entails that one doesn’t testify, unless one has the competence, authority or credentials to state truly that p. Now someone who lacks these properties may not be a very reliable testifier. But she is still capable of testifying. Her testimony may not be an epistemically good source of belief. But she can testify nonetheless. People who give false testimonies about, for example, others testify nonetheless; they testify falsely. And false testimony is testimony as much as a bad squash player is still a squash player.

All of this is obviously relevant for my argument that reading is a source of knowledge that is not coextensive with attending to testimony. For if Coady’s account of testimony is wrongheaded, my list of things that we may come to know through reading even though that doesn’t qualify as attending to Coadyan testimony won’t bear much weight. Let us therefore turn to another account and see whether on that account acquiring knowledge of the things that are on the list (in the contexts as sketched between square brackets), does qualify as the acquisition of knowledge through testimony. On this account, testimony is “people’s telling us things” (Audi 1998 : p. 131), or “tellings generally” with “no restrictions either on subject matter or on the speakers epistemic relation to it” (Fricker 1995 : pp. 396–7). Related is the view that testimony requires “only that it be a statement of someone’s thoughts or beliefs, which they might direct to the world at large and to no one in particular” (Sosa 1991 : p. 219). The essence of this broad view, as Lackey ( 2008 : p. 20) states, can be put as follows:

S testifies that p, iff S’s statement that p is an expression of S’s thought that p.

It is clear that this account is not vulnerable to the objections just raised against Coady’s account. On this account Sylvia Plath’s statements in her private diary qualify as testimony, as do expressions of thoughts that are false. That is to say: on this account one can testify that p, even if one doesn’t offer one’s thought as evidence, even if one doesn’t have the relevant competence, authority or credentials to state truly that p (i.e. even if the testimony is false), and even if one doesn’t express one’s thought that p to people who are in need of evidence regarding p.

Regarding the broad view of testimony, I also make two remarks. First, on this account too, we can acquire knowledge of the propositions on the list, in the contexts as sketched, while it doesn’t qualify as knowledge acquired by broad testimony. Take (b) for example, that the text contains a lot of metaphors : someone can know this through reading, even if this proposition is not an expression of the author’s thought. The same holds for (c), that the poem is a sonnet : this can be known through reading, even when this proposition is no part of the thought that the poet wanted to express. The same holds for most, or even all, of the other items on the list. Let me just cover case (a) that may seem an exception.

It may seem an exception, because the fact that Greene’s A Gun for Hire opens with “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven” might be considered to express a thought that Green had about one of his fictional characters, and so as testimony. However, we must tread carefully here. For the knowledge that the reader acquires upon reading the opening page of the novel is that the first line of the book reads “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven”. This proposition, however, is not a thought that is expressed in the opening page of Greene’s fine novel. Hence that proposition is not broadly testified by Greene, which means, in turn, that the reader’s knowing that proposition on the basis of reading, is not an instance of knowing that proposition on the basis of broad testimony.

I am not going down my list any further here, as the point I want to make should be clear by now: there are cases of acquiring knowledge through reading that don’t qualify as instances of acquiring knowledge on the basis of broad testimony. The point is well made even if some of the items on the list were to qualify as instances of acquiring knowledge through broad testimony.

My second remark, however, is that this account is too broad. There are expressions of thought that, intuitively, do not qualify as testimony. What prevents these expressions of thought from qualifying as testimony is that they are non-informational. Here is an example. It is a beautiful day, you are hiking in the mountains with a friend, and you say “Oh, what a beautiful day it is!” This is an expression of your thought, but it isn’t testimony, for, as Lackey says, this expression of your thought “is neither offered nor taken as conveying information”. (Lackey 2008 : p. 21) Of course, in special circumstances, the very same expression of your thought can qualify as testimony, for in stance when the person your are with is blind and takes the expression of your thought as conveying the information that it is a beautiful day. What this suggests, Lackey says, is that when an expression functions merely as a conversational filler, as it does in the initial example, it doesn’t qualify as testimony.

In addition to mere conversation fillers there are other kinds of expressions of thought that do not qualify as testimony. Adapting a point from Lackey, think of exhortations. You say to your son who is training for half the marathon “You can do it!” By saying this, you express a thought of yours, but it isn’t testimony, as you don’t offer what you say as conveying the information that your son can do it, nor does your son take what you say as conveying the information that he can do it.

Let me finally consider Lackey’s so-called disjunctive account of testimony that takes its cue from the distinction between testimony as an intentional act on the part of a speaker or writer and testimony as a source of belief or knowledge for the hearer or reader (Lackey 2008 : p. 27) and which forms the basis for her distinction between speaker testimony (s-testimony) and hearer testimony (h-testimony). Before presenting the full account, some terminology need be introduced. First, the notion of an “act of communication”:

A is an act of communication iff by performing A, a speaker or writer intends to express communicable content. (It does not require that the speaker or writer also intends to communicate that content to others.)

When Plath wrote in her diary for only private purposes, she was engaging in acts of communication, as she had the intention to express communicable content, even if she had no intention to communicate that content to others. It is possible, then, to engage in acts of communication without intending to communicate to others, i.e. it is possible to express communicable content, without intending to communicate that content to others. Of course, the two intentions may go together, but the point is that they needn’t.

Second, the notion of “conveying information”. Acts of communication, for instance Plath’s writing in her diary, “convey information”. What does it mean for an act of communication A to convey the information that p? Rather than defining this notion, Lackey provides paradigmatic cases. An act of communication A conveys the information that p, she says, when, for example, (1) A is the utterance of a declarative sentence that expresses proposition p, or (2) when < p > is an obvious (uncancelled) pragmatic implication of A. (Lackey 2008 : p. 31)

With the notions of “acts of communication” and “conveying information” thus clarified, Lackey defines speaker testimony and hearer testimony as follows:

Speaker Testimony S s-testifies that p by performing A iff, in performing A, S reasonably intends to convey the information that p (in part) in virtue of A’s communicable content. (Lackey 2008 : p. 30)

Hearer Testimony S h-testifies that p by performing A iff H, S’s hearer, reasonably takes A as conveying the information that p (in part) in virtue of A’s communicable content. (Lackey 2008 : p. 32)

The account of s-testimony requires that a speaker intends to convey information to her hearer and in that sense requires that a speaker’s A be offered as conveying information. The clause “in part in virtue of A’s communicable content” is included in order to exclude cases like the following: you sing in a soprano voice “I have a soprano voice” and you intend to convey the information that you have a soprano voice in virtue of the perceptual content of your sung assertion, not in virtue of the communicable content of your sung assertion; you intend to convey the information that you have a soprano voice by your singing in soprano voice , and not by the content of the words that you sing . In this case you are not s-testifying that you have a soprano voice. But you would be s-testifying that you have a soprano voice when you would just say “I have a soprano voice” or say “I have one of the women’s voices, but not the alto”. Had you said the latter, you would still have conveyed the information that you have a soprano voice—for there is a reasonably obvious connection between “I have a soprano voice” and “I have one of the woman’s voices, but not the alto”.

Whereas s-testimony requires some intention on the part of the speaker to convey information, no such intention is required for h-testimony. H-testimony captures the sense in which testimony can serve as a source of belief or knowledge for others, regardless of the testifier’s intention to be such an epistemic source. Crucial for h-testimony is that the hearer or reader takes the speaker’s or writer’s A to convey information.

It follows from these accounts that a speaker or writer can s-testify without h-testifying, vice versa. But they can also go together. Lackey’s official statement of the Disjunctive Account of Testimony is as follows:

S testifies that p by making an act of communication A iff (in part) in virtue of A’s communicable content (1) S reasonably intends to convey the information that p and/or (2) A is reasonably taken as conveying the information that p. (Lackey 2008 : pp. 35–36)

Let me now return to the question for which the presentation of Lackey’s account was propaedeutic: is all knowledge we can acquire through reading, knowledge based on Lackyan testimony? Let me go down the list. Regarding (a): as indicated, the knowledge a reader of the first line of A Gun for Hire acquires through reading is that the first line of that book reads “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven”. This knowledge is not based on Greene’s s-testimony, as Greene did not intend to convey the information that the first line of A Gun for Hire reads “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven” . This is not to deny that it is possible to think up a scenario in which someone’s knowing this is based on Greene’s s-testimony. Suppose Jane is Greene’s neighbor, and she has asked him what the title of his new book will be and what its opening sentence will be. Greene’s answer is that the title is A Gun for Hire , and its opening line “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven”. Jane’s knowledge that the first line of A Gun for Hire reads “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven” in this case is based on Greene’s s-testimony. But in the case as originally described, the reader acquires the indicated knowledge not through s-testimony. Nor does she acquire it through h-testimony, for it is not the case that a reader, upon reading “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven” takes this to convey the information that the first line of A Gun for Hire reads “Murder didn’t mean much to Raven” . So, the knowledge acquired in the context as described in case (a) is knowledge through reading, but it is not knowledge through Lackeyan testimony.

That a specific text contains a lot of metaphorical expressions , or that it is a sonnet , or that it is humorous , as in cases (b), (c), and (d) is, in the contexts as sketched, knowledge acquired through reading. But it surely isn’t acquired through the author’s s-testimony: the author’s acts of communication aren’t intended to convey the information that the text contains a lot of metaphorical expressions , or that it is sonnet , etc. Nor is it acquired through the author’s h-testimony: the reader doesn’t take the author’s acts of communication to convey the information that the text contains a lot of metaphorical expressions , etc. This means that the knowledge acquired in these cases is not based on Lackey testimony.

Likewise, that the article contains an invalid argument , or that the review is based on a misunderstanding , or that the book is a warning call not to harbor grudges in one’s heart , or that the author assumes that p, as in (e), (f), (g) and (h), in the contexts as sketched, is known through reading. But that knowledge isn’t based on either s-testimony, nor on h-testimony. To write this out for (f): the reviewer certainly doesn’t intend to convey the information that his review is based on a misunderstanding, so the review doesn’t qualify as s-testimony; nor can a reader reasonably take the review’s communicable content to express the information that the review is based on a misunderstanding , so the review doesn’t qualify as h-testimony either. Which means that the knowledge acquired just isn’t based on Lackey testimony.

Likewise, that the author is intimately familiar with the Scottish Enlightenment , or that what the Dutch did in de Caribbean was wrong , or that the square root of 2 is not a rational number , as in (i), (j), and (k), is, in the contexts as sketched, knowledge acquired through reading. But it isn’t knowledge based on Lackeyan testimony. To write this out for (k): when you come to know that the square root of 2 is not a rational number, because you have read, followed and comprehended the proof, then your knowledge isn’t based on s- or h-testimony, as you now “see”, intellectually, for yourself that this is true.

The conclusion of this section should be clear by now. The lack of attention that reading has received among analytic epistemologists, cannot be explained by reference to the alleged fact that knowledge acquired through reading just is a token of the type knowledge acquired through testimony. What a reader may come to know through reading isn’t, or isn’t necessarily, coming to know through testimony . I showed that this is true given three different accounts of testimony: Coady’s, Audi’s (and others) and Lackey’s. The list that I offered lists things that someone may come to know through reading, while the knowledge thus acquired does not qualify as testimonial knowledge. I have indicated that we may come to know any of the things on this list also through testimony, as someone may testify any of these things to us. But the point I have been eager to establish is that when we read texts, we can, in the appropriate circumstances, also just through reading come to know things. If I am correct in arguing that acquiring knowledge through reading isn’t coextensive with acquiring knowledge through testimony, then there is a prima facie case that reading merits special epistemological attention.

3 Reading isn’t just seeing words

The second possible explanation of the inattention that epistemologists have paid to reading is that reading just is an instance of perception, and therefore merits no special attention. “Reading” is just the name for the perception of a particular kind of objects, viz. words Footnote 5 and sentences. The fact that we have no special name for seeing horses, or paintings, but that we do have a special name for seeing words and sentences, this explanation says, should not seduce us into thinking that reading is in any principled way different from seeing horses and paintings.

This explanation is uncompelling. Reading is not just seeing a particular kind of objects, viz. words and sentences, whereas seeing a horse just is seeing a certain kind of animal, and seeing Van Gogh’s Sunflowers just is seeing a particular painting. One is just seeing something when one is having certain visual experiences of shapes, colors, and their relative positions in one’s visual field. One may just see a horse, without knowing or believing that it is a horse one is seeing, without even knowing or believing that it is an animal one is seeing, without even knowing or believing anything at all about what one is seeing. What I have referred to as just seeing , is what Fred Dretske initially called “object-perception” (as contrasted with fact-perception: seeing that the animal is a horse), and later on “simple seeing”. Footnote 6 According to Dretske simple seeing X is marked by the fact that it is compatible with having no beliefs about X. Footnote 7

It seems clear that reading isn’t just seeing words and sentences, it isn’t just looking at what are in fact words and sentences. For suppose you don’t know Greek, but have opened a Greek edition of Homer’s Odyssey ; then you are seeing words and sentences, but you aren’t reading. Footnote 8 Moreover, if reading would be just seeing words and sentences, it would have to be compatible with forming no beliefs about what one is reading. But that seems wrong. One isn’t reading unless one is forming such beliefs as that

this sentence is a statement, that sentence is a question the word W that is used here, means that the sentence S that is written here, means this the point that the author is navigating towards seems to be p given what is said about her, the main character could be a hero, but also a villain what the author says here, is rather implausible

If reading requires such beliefs to be occurrent, the requirement seems overly intellectually demanding. For when we read we don’t normally form explicit beliefs about words or sentences, what they mean, or what their illocutionary force is, etc. Normally we find ourselves understanding what a sentence says or means, without forming such explicit beliefs. That is to say, normally we form such beliefs dispositionally . It is only on special occasions, such as when we read difficult passages, that we form such beliefs occurrently. But if we take the notion of “belief” to cover both occurrent and dispositional belief, then we must say that reading involves believing.

So, reading isn’t just seeing . Still, there is a relation, or even multiple relations, between reading and seeing. What relation(s)? Here we do well to keep in mind that, as Nikolas Gisborne has said, “see” is a massively polysemous verb. (Gisborne 2010 : p. 118) Three senses are especially relevant for present purposes. First, there is a sense that we have already encountered when discussing the notion of “object perception”, which Gisborne calls the prototypical sense of”see”. In this sense to “see” is to perceive visually . In such sentences as “I can see the King and the Queen from here”, and “I saw the horse in the field”, “see” is used in the prototypical sense. Second, “see” has a sense in which it is a knowledge ascription. And here two different classes of cases must be distinguished. First, there is the purely propositional sense of “see” that we find, for example, in such sentences as “I can see that the argument is valid”, and “The King saw that the Queen was right”. Here “see” has no visual meaning whatsoever. Second, there is the so-called perceptual propositional sense of “see that” that we find, for example, in such sentences as “Jane saw through the window that the child had crossed safely”, and “Harold sees that it is raining”. In these sentences “see” has both a prototypical sense and an epistemic sense. As Craig French has observed, “see” in propositional contexts where it has a prototypical sense, is evidential , by which he means that in such contexts “see” indicates that the source of the information in the that-clause is visual . (French 2012 : p. 122)

Returning to the relation between reading and seeing, we have already observed that reading involves “seeing” words and sentences in the prototypical sense, but that it is not identical with it. If one is reading, one may be “seeing” something in another sense as well. Suppose you read in the newspaper that the Queen is in Dublin, then you may say “I see in the newspaper that the Queen is in Dublin”. In this sentence “see” has not merely a prototypical sense (it is not just seeing words and sentences) but also an epistemic sense. Here “reading” involves “seeing” in the perceptual propositional sense. For “see” is used here in a propositional context and has a prototypical sense. Should we go further and say that reading is identical to “seeing” in the perceptual propositional sense? Footnote 9

Let us consider this matter starting from a slightly different question. Suppose we ask ourselves whether we can know what a word or sentence means through seeing . I want to approach this question via a detour through Thomas Reid’s distinction between original and acquired perception:

Our perceptions are of two kinds: some are natural and original, others acquired and the fruit of experience. When I perceive that this is the taste of cyder, that of brandy; that this is the smell of an apple, that of an orange … these perceptions are not original, they are acquired. But the perception which I have by touch, of the hardness and softness of bodies, of their extension, figure and motion, is not acquired, it is original. (Reid 1764 : p. 171)

The idea behind the distinction is that certain things can be perceived without any learning process, for example the hardness or softness of an object, while other perceptions do require learning, such as perceiving that this is the taste of brandy. The distinction also applies to seeing. Says Reid: “By sight we perceive originally the visible figure and color of bodies only, and their visible place”. Footnote 10 So original seeing includes seeing 2-dimensional shapes and patches of colors. Seeing a sphere, Reid held, is an instance of acquired perception, as it requires a learning process in which certain visual appearances become associated with certain tactile sensations. Other examples of acquired seeing are seeing that that is a horse, or seeing that it is one’s neighbor’s horse.

Reid’s distinction can be applied to reading. Reading involves seeing little curved and straight lines on a page, which instances original perception. Original visual perceptions can be described in sentences in which “see” has the prototypical sense. For example, in the sentences “Agnes saw black little curves on a white sheet of paper”, and “Agnes saw words on a page” “saw” has the prototypical sense. (I note that in these sentences “saw” denote simple seeing .)

But seeing that those little lines are Dutch words and sentences qualifies as acquired perception. For to see so much, one has to go through a learning process. Once one has the acquired perception that the little lines are the Dutch words “de”, “klomp”, “is” and “gebroken” respectively, one may furthermore see that these words, in this order, jointly constitute a grammatical Dutch sentence, which is yet another instance of acquired perception. These acquired perceptions can be described by sentences in which “see” has the perceptual propositional sense, as, for example, in the sentences “Agnes saw that the little lines formed a Dutch word”, and “Agnes saw that the words compose a Dutch sentence”. (I note that “saw” in these sentences is fact - perception .)

Upon seeing that the sequence of Dutch words “de”, “klomp”, “is” and “gebroken” form a grammatical sentence, one may “see” that that sentence expresses the proposition that the wooden shoe is broken . This is, again, an acquired perception. But this kind of acquired perception can not be described by sentences in which “see” has the perceptual propositional sense. It can only be described by sentences in which “see” has the purely epistemic sense. Take for example the sentence “Agnes saw that the string of Dutch words expresses the proposition that the wooden shoe is broken.” Here “saw” has no visual sense at all. (I note that here too “saw” denotes fact-perception.)

So, reading involves “seeing” in different senses:

just seeing little lines, just seeing words and sentences (original seeing; “see” has the prototypical sense)

seeing that the little lines are words and sentences (acquired seeing; “see” has the perceptual propositional sense)

seeing that the sentences express a particular proposition (acquired seeing; “see” has the purely epistemic sense)

Some more illustrations of “see” in the purely epistemic sense, used in the context of reading, might be helpful. When someone says, upon reading a particular text, that she now “sees” that the word ‘scientism’ is not used by its author in a pejorative way, then “see” is used in the purely epistemic, non visual, sense. When we read, and on that basis acquire a sense of what the words and sentences mean and “see” what the writer intended to say, then “see” is again used in a purely epistemic sense. Finally, when we don’t know what “to procrastinate” means, consult a dictionary and there “see” that it means “to put things of”, “see” is again used in the purely epistemic sense.

All of this goes to show that reading isn’t just seeing , which is the main point of this section. But what I said also goes to show that reading is not merely “seeing” in the perceptual propositional sense, but that it also involves “seeing” in the purely epistemic sense.

4 What is reading? An analysis

In this section I offer an analysis of reading, by formulating necessary and sufficient conditions for “person S is reading”. The previous section already made a start on this, by noting that someone may be just seeing words and sentences, and yet not be reading, because she doesn’t know that what she is seeing are words. This strongly suggests that (object-)seeing words and sentences is insufficient for reading, even if it is necessary for it.

One may also (fact-)see words and sentences, for instance see that what one is looking at are words, or see that they are Italian or Dutch words, but still not be reading. For example, you may know enough to be able to see that the words you are looking at are Italian or Dutch words, but since you don’t know what the words mean and have no grasp of the syntax of these languages, you still aren’t reading. One isn’t reading in these cases, because one doesn’t know the language, or doesn’t know it well enough. This strongly suggests, first, that fact-seeing words and sentences is insufficient for reading, even if it is necessary for it; and second that knowing the language to which the words belong is also necessary for reading.

Now one may (object-)see the words, fact-see that they are Italian or Dutch words, and even know these languages (so know what their words mean, know their syntaxes) and still not be reading. The graphic designer who is working on the lay-out of the pages of a book that is to be published, (object-)sees words, sees that they are English words, and, even knows the language, and yet may not be reading, for example because she is not focused on the content of the words, isn’t trying to get a sense of what the words jointly mean. This strongly suggests that focusing on the content, trying to get a sense of what the words jointly mean, is also necessary for reading. Footnote 11

This condition rules out the following interactions with words as instances of reading: someone is reading aloud words that belong to a language that he knows, but he does it, so to speak, “mechanically”; he reads up the words alright, but he is not attending to their content , not to what they mean . That person is parroting, i.e. “articulating sounds that have meaning”, but isn’t reading. So-called “reading-machines”, pieces of assistive technology that scan words and sentences and use a speech synthesizer to read them out loud, are also parroting; they aren’t reading.

The expression “what words jointly mean”, is complex Footnote 12 but I intend it to cover the meaning sentences Footnote 13 as well as the meaning of paragraphs or even larger textual unit. Footnote 14 The meaning of these items can be understood, or apprehended, with greater or lesser accuracy, in greater or lesser depth. But some apprehension of the joint meaning of words is required if there is to be reading. That is why stones and cats are incapable of reading—they don’t understand, or apprehend, the joint meaning of words. This is not to deny that certain animals can be trained to respond to words and sentences in ways that mimic the responses of humans who do apprehend their meaning. Upon being confronted with a blackboard on which the words “Now stamp with your right leg five times!” are written, both a horse and a person may respond by stamping five times with their right leg. But only be the person, not the horse, has read the words, as only the person, not the horse, has understood the joint meaning of the words. The horse is at best trained to behaviorally respond in a certain way to what are in fact words composing a sentence, but doesn’t understand the words, because he doesn’t see that they are words, and doesn’t know the language to which they belong.