- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Mexican-American War

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 10, 2022 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848 marked the first U.S. armed conflict chiefly fought on foreign soil. It pitted a politically divided and militarily unprepared Mexico against the expansionist-minded administration of U.S. President James K. Polk, who believed the United States had a “Manifest Destiny” to spread across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. A border skirmish along the Rio Grande that started off the fighting was followed by a series of U.S. victories. When the dust cleared, Mexico had lost about one-third of its territory, including nearly all of present-day California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico.

Causes of the Mexican-American War

Texas gained its independence from Mexico in 1836. Initially, the United States declined to incorporate it into the union, largely because northern political interests were against the addition of a new state that supported slavery . The Mexican government was also encouraging border raids and warning that any attempt at annexation would lead to war.

Did you know? Gold was discovered in California just days before Mexico ceded the land to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Nonetheless, annexation procedures were quickly initiated after the 1844 election of Polk, a firm believer in the doctrine of Manifest Destiny , who campaigned that Texas should be “re-annexed” and that the Oregon Territory should be “re-occupied.” Polk also had his eyes on California , New Mexico and the rest of what is today the American Southwest.

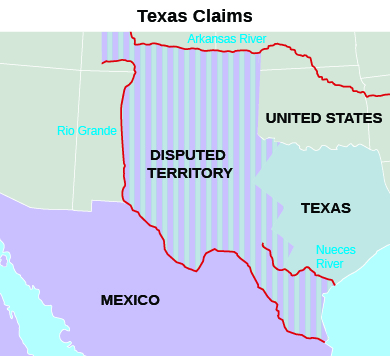

When his offer to purchase those lands was rejected, he instigated a fight by moving troops into a disputed zone between the Rio Grande and Nueces River that both countries had previously recognized as part of the Mexican state of Coahuila .

The Mexican-American War Begins

On April 25, 1846, Mexican cavalry attacked a group of U.S. soldiers in the disputed zone under the command of General Zachary Taylor , killing about a dozen. They then laid siege to Fort Texas along the Rio Grande. Taylor called in reinforcements, and—with the help of superior rifles and artillery—was able to defeat the Mexicans at the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma .

Following those battles, Polk told the U.S. Congress that the “cup of forbearance has been exhausted, even before Mexico passed the boundary of the United States, invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon American soil.” Two days later, on May 13, Congress declared war, despite opposition from some northern lawmakers. No official declaration of war ever came from Mexico.

U.S. Army Advances Into Mexico

At that time, only about 75,000 Mexican citizens lived north of the Rio Grande. As a result, U.S. forces led by Col. Stephen Watts Kearny and Commodore Robert Field Stockton were able to conquer those lands with minimal resistance. Taylor likewise had little trouble advancing, and he captured the city of Monterrey in September.

With the losses adding up, Mexico turned to old standby General Antonio López de Santa Anna , the charismatic strongman who had been living in exile in Cuba. Santa Anna convinced Polk that, if allowed to return to Mexico, he would end the war on terms favorable to the United States.

But when Santa Anna arrived, he immediately double-crossed Polk by taking control of the Mexican army and leading it into battle. At the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, Santa Anna suffered heavy casualties and was forced to withdraw. Despite the loss, he assumed the Mexican presidency the following month.

Meanwhile, U.S. troops led by Gen. Winfield Scott landed in Veracruz and took over the city. They then began marching toward Mexico City, essentially following the same route that Hernán Cortés followed when he invaded the Aztec empire .

The Mexicans resisted at the Battle of Cerro Gordo and elsewhere, but were bested each time. In September 1847, Scott successfully laid siege to Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle . During that clash, a group of military school cadets–the so-called ni ños héroes –purportedly committed suicide rather than surrender.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Guerrilla attacks against U.S. supply lines continued, but for all intents and purposes the war had ended. Santa Anna resigned, and the United States waited for a new government capable of negotiations to form.

Finally, on Feb. 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, establishing the Rio Grande (and not the Nueces River) as the U.S.-Mexican border. Under the treaty, Mexico also recognized the U.S. annexation of Texas, and agreed to sell California and the rest of its territory north of the Rio Grande for $15 million plus the assumption of certain damage claims.

The net gain in U.S. territory after the Mexican-American War was roughly 525,000 square miles, an enormous tract of land—nearly as much as the Louisiana Purchase’s 827,000 square miles—that would forever change the geography, culture and economy of the United States.

Though the war with Mexico was over, the battle over the newly acquired territories—and whether or not slavery would be allowed in those territories—was just beginning. Many of the U.S. officers and soldiers in the Mexican-American War would in just a few years find themselves once again taking up arms, but this time against their own countrymen in the Civil War .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

The Mexican American War. PBS: American Experience . The Mexican-American war in a nutshell. Constitution Daily . The Mexican-American War. Northern Illinois University Digital Library ..

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- The Mexican-American War

A forgotten war with unforgettable consequences

Opinion on the war with Mexico was divided and Woodville therefore depicted a range of responses among the figures reading the latest news in a Western outpost. Detail, Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico , 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art). Watch the video .

Essay by Dr. Kimberly Kutz Elliott

A tourist visiting the National Mall in Washington, D.C. today is likely to see monuments commemorating American involvement in several foreign wars, including the striking Vietnam Memorial , with its reflective surface naming the war dead, or the squadron of stainless steel soldiers honoring veterans of the Korean War. That same tourist might be surprised to learn that the United States had fought another foreign war whose toll on the American population was greater than either of those conflicts: the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). [1]

Maya Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 1982, granite, National Mall, Washington, D.C. (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There is no memorial to the Mexican-American War in Washington, D.C., and only about 30 monuments across the whole of the United States pay tribute to a war in which more than 15,000 American soldiers lost their lives. By comparison, there are at least 13,000 historical markers commemorating the U.S. Civil War. [2] In fact, the Mexican-American War has been overlooked in both U.S. and Mexican popular culture. The war is rarely depicted in film, and no images of the War of Northern Invasion (as the war is named in Mexico) were made by Mexican artists. A war of conquest conducted by a land-hungry U.S. government against ill-supplied Mexican soldiers did not generate much pride for either nation.

Timeline of significant events

Nevertheless, the Mexican-American War had far-reaching consequences for both the United States, Mexico, and the Indigenous peoples whose land both nations claimed. First among these was the cession of about one third of Mexico’s territory to the United States, a landmass of over 338,000,000 acres. Redrawing the border added to American economic prosperity at Mexico’s expense. The war also contributed to the outbreak of later civil wars in both countries: the Civil War in the United States (1861–1865) and the War of Reform in Mexico (1857–1860) .

Lastly, the war’s outcome left many residents of the ceded territory worse off than they had been under Mexican rule, which had guaranteed people of African and Indigenous descent some rights and protections. Not only did the U.S. government permit slavery (which had been outlawed in Mexico for years) but the annexation of these lands sent large numbers of white American settlers west, where they displaced and often killed Indigenous people.

Comparing Mexican and American societies before the war

Both the United States and Mexico were young republics that had recently gained independence after centuries of European colonization. The process had been considerably easier for the United States, which had had French aid in defeating Great Britain, as well as bountiful natural resources to fuel its economy. In the early nineteenth century, the people of the United States were awash in patriotism, Protestant religious fervor, and enthusiasm for rapid expansion. Jacksonian Democracy , ushered in by the presidency of Andrew Jackson, extolled the virtues of the “common man,” extending the franchise to all white men regardless of their social standing.

George Caleb Bingham portrayed the Missouri election in which he was running as a candidate for state legislature (he depicts himself at center, seated on the wooden steps). Bingham seems both to celebrate and critique the enthusiastic exercise of mid-nineteenth century U.S. democracy, depicting the white male voters with equal dignity, although he shows some men who are clearly inebriated. George Caleb Bingham, The County Election , 1852, oil on canvas, 38 x 52 in. (96.5 x 132.1 cm) ( Saint Louis Art Museum ).

But citizenship in the United States became more entwined with constructions around racial difference at the same time it became less tied to class. The “white man’s republic” championed by Jacksonian Democrats categorically excluded women and people of color from the body politic. This was particularly evident in Jackson’s policy of “Indian Removal” : where once white Americans had committed to christianize and assimilate Indigenous people for their own good, many now declared Indigenous people savages who must either be expelled to distant western lands or face extinction.

By contrast, Mexico had won independence after 300 years of Spanish colonization without outside help, but the conflict had left the nation in a difficult economic state, with its mining, industrial, and agricultural capacity significantly reduced. The Mexican government was unstable, with 50 different governments in the 30 years after independence, most installed by military coup. Conservatives wanted to maintain a version of the colonial system that privileged social elites, the army, and the Catholic Church, while Liberals wanted to implement republican reforms.

Although Mexican society did make sharp distinctions of race and class in the years leading up to the war, nonwhites had more political power and social mobility than in the United States. Centuries of racial and cultural mixing between the descendants of Spanish settlers, enslaved Africans, Indigenous inhabitants, and Asian immigrants of the region had created a diverse populace. After independence from Spain, the Mexican government removed racial identifiers from official documents to promote equality in the new republic, and in 1829 abolished slavery altogether.

Cotton, Texas, and Manifest Destiny

Many Americans believed that the key to their prosperity was relentless expansion. The U.S. government had purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803, and newspaper editors spread the idea that it was the “ Manifest Destiny ” of the United States to possess North America from the Atlantic to Pacific Ocean. The ideology of Manifest Destiny justified U.S. imperialism by claiming that the nation had a divine mission to spread democracy and Protestant Christianity across the continent.

Expansion was particularly crucial for the cotton planters who dominated the southern United States. Cultivating cotton quickly depleted soil, and plantation owners were eager to obtain more fertile land. They relied on the forced labor of enslaved people of African descent, and sought to expand slavery along with the borders of the American south. Many cotton planters crossed the border into the Mexican territory of Coahuila y Tejas, where they were initially welcomed as a stabilizing force that would help to repel raids from the powerful Comanche ( Nʉmʉnʉʉ ) nation. But the Mexican government soon grew frustrated with the American settlers, who disregarded the ban on slavery and showed no intention of assimilating into Mexican society.

The war begins

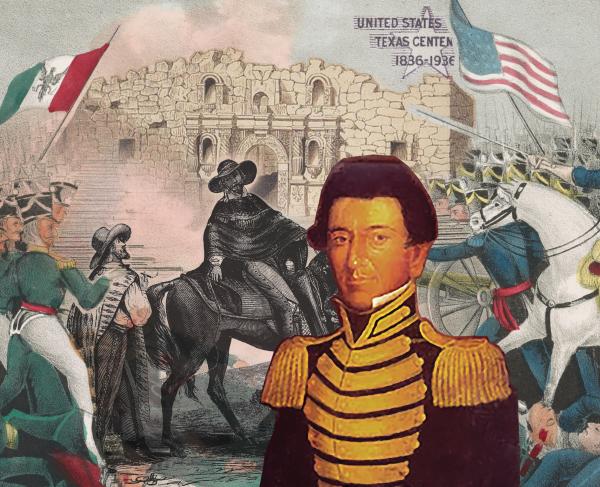

In 1836, American and Mexican residents who wanted to introduce enslaved laborers to the area to farm cotton took advantage of the Mexican government’s tenuous hold on the country’s periphery by declaring Texas an independent republic. The Texians triumphed, despite their storied defeat at The Alamo , a Spanish mission ( San Antonio de Valero ) that had been converted into a fortress. But the Mexican government did not accept the treaty granting Texas independence since it had been signed under duress. For nearly ten years, the Mexican government considered Texas a rebel territory, while the United States recognized it as a sovereign nation.

In fact, Texians wanted to join the United States and applied for annexation shortly after the rebellion. But the U.S. Congress, unwilling to upset the delicate balance between states that permitted slavery (“slave states”) and states that did not (“free states”), declined to consider the matter. All of that changed when James K. Polk was elected president in 1844. Polk was a Democrat, closely tied to Andrew Jackson, and he favored territorial expansion. Consequently, the United States annexed Texas in 1845 (leading Mexico to sever diplomatic relations), and Polk negotiated with Britain for a portion of the Oregon Territory in 1846.

Polk also sent an envoy to Mexico to offer to purchase California, then coveted for its Pacific ports and fertile farmland, but the Mexican government refused. Finally, in April 1846, Polk sent U.S. soldiers under the command of General Zachary Taylor to disputed territory south of the Nueces River, hoping to provoke conflict.

Text of Polk’s war proclamation in the New-York Daily Tribune ( Library of Congress ).

The progress of the war

Polk’s gamble paid off; after a U.S. patrol marched into the disputed territory, a Mexican cavalry unit attacked, killing 11 American soldiers. When news reached Washington, D.C. two weeks later, Polk wen t to Congress to ask for a declaration of war, claiming that Mexico had shed “American blood on the American soil.” Many U.S. lawmakers, especially those of the opposition Whig party, were suspicious of Polk’s claims—Abraham Lincoln, then a young Congressman, would later ask the president for evidence of the exact “spot” where the hostilities had begun—but conscious that fighting was already underway, the Whigs ultimately voted to support the war.

Detail of map below, showing land and naval campaigns during the Mexican-American War, including Monterrey and Buena Vista.

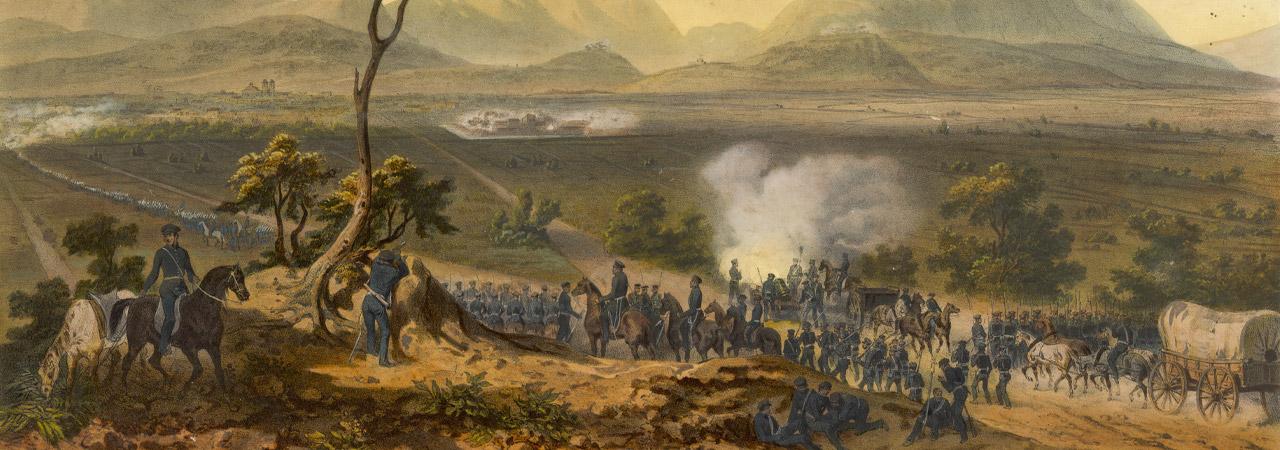

General Taylor commanded just one of many American military forces in what would become a two-year-long, multi-front war. In northern Mexico, Taylor fought inland to Monterrey and secured the region for the United States in the Battle of Buena Vista.

Farther north (see map below), the U.S. army captured Santa Fe, in what is now New Mexico, without firing a shot (although Mexican and Indigenous Puebloan residents later rebelled against U.S. occupation in the Taos Revolt). Naval campaigns targeted the west coast of Mexico from Mazatlán to Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco), and wrested control of the ports and pueblos of California along with several ground units.

Map of land and naval campaigns during the Mexican-American War. The inset depicts General Winfield Scott’s route from Veracruz to Mexico City (map: Kaidor , CC-BY-SA 3.0).

The most devastating campaign, however, was in southeastern Mexico (see inset in map above). In 1847, U.S. General Winfield Scott conveyed a force of more than 13,000 men by sea to Veracruz. He deliberately followed the same path of conquest to Mexico City that Hern án Corté s had taken more than 300 years earlier to the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan (which became Mexico City). In September 1847, the U.S. army invaded the nation’s capital, Mexico City. Despite months of guerrilla warfare , Mexicans could not expel the occupying army.

In February 1848, the two nations negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo to end the war. The treaty’s terms gave the United States most of what is now the southwestern United States, including the modern-day states of Texas, California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and portions of Colorado and Wyoming, in exchange for $15 million and the forgiveness of Mexican debts to American citizens. Mexicans who chose to remain in the territory would receive American citizenship.

“A wicked war”

“I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico.” —Ulysses S. Grant, 1879

Ulysses S. Grant, who would go on to command the victorious forces in the Civil War nearly twenty years later, not to mention serve as president of the United States, was a 24-year-old lieutenant during the Mexican-American War. Grant believed that in the Mexican-American War, a stronger nation had unjustly made war on a weaker one. [3] Indeed, the United States government had expected a quick win against an inferior opponent, and the extent of Mexican resistance came as a surprise. Racial and religious prejudice influenced American attitudes toward Mexicans. Officers wrote about the depredations committed by volunteers, who frequently stole from and sometimes killed Mexican civilians.

Most American soldiers and volunteers were Protestants, rife with anti-Catholic prejudice, and they disdained Mexican religiosity as superstition and ignorance. In some cases, American soldiers deliberately defiled churches or religious objects. Their behavior so disgusted German and Irish Catholic volunteers that several hundred switched sides and fought for the Mexicans as the St. Patrick’s Battalion, or San Patricios .

The San Patricios were U.S. soldiers who switched sides to fight with the Mexican army. Many were captured and executed in the battles leading up to the occupation of Mexico City. Samuel Chamberlain, who was a private in the U.S. army during the 1847 mass execution, illustrated the event in his memoirs twenty years later. Chamberlain likely made sketches on site (suggested by the recognizable volcanoes in the Valley of Mexico and Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City at right) and worked them into finished watercolors at a later time. The hanging scene’s distance from the viewer, and the lack of visible emotion with which Chamberlain portrays it, suggests that he saw the San Patricios as traitors. Samuel Chamberlain, Hanging of the San Patricios following the Battle of Chapultepec , c. 1867, watercolor ( Smithsonian Magazine ).

Unknown photographer, General Wool and staff in the Calle Real, Saltillo, Mexico , c. 1847 ( Amon Carter Museum of American Art )

New technologies of communication and representation brought news of the war home to civilians faster and more vividly than ever before. The first photographs of war anywhere in the world emerged from this conflict: a series of 50 daguerreotypes, now housed at the Amon Carter Museum, which were created in 1847 by an unknown photographer in Saltillo, Mexico. Daguerreotypists followed the U.S. troops, taking portraits of officers, landmarks, and grave sites as souvenirs. [4] The Mexican-American War was also the first war in which U.S. journalists accompanied the army as foreign correspondents, and the updates they sent home to newspapers by telegraph generated great interest and patriotism among the public.

Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico , 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

But the war and its expansionist aims did not enjoy universal support in the United States. Just three months into the conflict anti-slavery politicians introduced a bill into Congress, the Wilmot Proviso , that would outlaw slavery in any territory that might be gained from Mexico.

In addition, the first anti-war movement in the United States arose in response to the conflict; many northeastern intellectuals protested what they saw as an unprincipled land-grab aimed at increasing the power of slaveholders. Henry David Thoreau, a leading Transcendentalist writer, was jailed for refusing to pay taxes to support the war. His essay on the duty of citizens to refuse to cooperate with immoral government actions, “Civil Disobedience,” inspired the nonviolent resistance tactics of later civil rights leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Consequences of the Mexican-American War

The war’s human cost is difficult to quantify. Historians estimate that 25,000 Mexican soldiers died, as well as 15,000 American soldiers. The vast majority of American men died from disease, not battlefield injuries, as the volunteer soldiers failed to implement necessary measures for sanitation. As many had feared, the addition of land suitable for cotton farming meant the extension of slavery, along with the human misery of the enslaved men and women who cleared and farmed the land. White settlers who moved to the west did not respect the rights of the Indigenous people or Mexican-Americans (those who had received U.S. citizenship at the war’s end) living there, often forcibly removing them from their land.

The political and social consequences of the war are easier to see. For Mexico, the defeat demonstrated the weakness of the country. Debates over the proper role of the army and the Catholic Church in politics led to the Reform War, and later the installation of a French emperor in Mexico. For the United States, the acquisition of western lands proved both a blessing and a curse. Their rich resources, including the gold discovered in California just weeks before the end of the war, contributed to growing American economic power. But the addition of new territory upset the fragile balance of power that had kept free and slave states bound together in an uneasy union. In 1861, the tensions over the expansion of slavery into the west led to the U.S. Civil War.

- War dead as a percentage of total U.S. population. .057% of the U.S. population died as a result of the Mexican-American War.

- See the Historical Marker Database for estimates.

- For Grant’s quote concerning the “wicked war,” see John Russell Young, Around the World with General Grant (New York: American News, 1879), 2:447–48.

- James Oles, Art and Architecture in Mexico (Thames and Hudson, 2013), 155.

Additional resources:

View the text of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo at the Library of Congress

See more Mexican-American War daguerreotypes from Google Arts & Culture

Political cartoons and prints relating to the Mexican-American War at the Library of Congress

Samuel Chamberlain’s Mexican-American War watercolors at the San Jacinto Museum

Find this essay in...

Seeing america.

- Theme: America in the World

- Period: 1848–1877

- Topic: The Frontier, Manifest Destiny, and The American West

Art histories

Explore the diverse history of the United States through its art. Seeing America is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Alice L. Walton Foundation.

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

The Impact of the Mexican American War on American Society and Politics

On February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed which officially ended the Mexican-American War. However, as the guns fell silent, and the men returned home, a new war was brewing, one that continues to shape the course of this country to this day.

While Ulysses S. Grant might have argued that the Civil War was God’s punishment for the Mexican-American War, a “wicked war" that was rooted in imperialism and the expansion of slavery, many Americans supported the Mexican-American War as they viewed it as the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny: the promise that the United States would extend from “sea to shining sea.” While Manifest Destiny remains a core of U.S. national identity, in the 1840s it encouraged a slew of ideological debates over this potential new territory, specifically if the territory should be free or enslaved. The Louisiana Purchase caused a major crisis over the organization of new states which Congress ultimately resolved with the Missouri Compromise, the compromise to end all compromises. It is important to note that the debates in 1820 were largely split among party lines, i.e. Democrats vs. Whigs . However, the Mexican American War reopened past wounds and sent the United States into another legislative crisis.

Even before the war was won and territory had been ceded, Congress was already discussing how to organize any potential new territory gained as reparations from Mexico. One of the most important of proposals was the Wilmot Proviso which Representative David Wilmot of Pennsylvania proposed in 1846, two years before the war ended. Under this proviso, any territory gained by war with Mexico should be free and thus reserved exclusively for whites. Wilmot was a free-soiler, which meant that he did not want to abolish slavery in the places it currently existed but rather prevent its expansion to new territories. However, Wilmot was also a Northern Democrat, and most Democrats supported slavery and protected it, even if they themselves did not own slaves. Many Northern Whigs believed in something called the Slave Power Conspiracy, a conspiracy theory in which slaveowners (the Slave Power) dominated the country’s political system even though they were a minority group, which was accomplished through a coalition with “dough-faced Democrats,” Northern Democrats who supported and protected slavery. While the Wilmot Proviso failed in the Senate, it passed in the House of Representatives because of a coalition between Northern Democrats and Northern Whigs and illustrates the first shift from party alliances to sectional alliances. Indignation over the Wilmot Proviso united southerners against northern threats to their most valuable institution, slavery. After this vote, the antebellum political landscape was forever changed.

The failure of the Wilmot Proviso only put off the issue of slavery for so long. With the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded over 525,000 square miles of territory to the United States in exchange for $15 million and the assumption of Mexican debts to American citizens, which reopened the slavery issue. In order to promote party loyalty without aggravating sectional tensions, the Whigs did not include specific resolutions on slavery in their official platform for the Election of 1848. The Democrats ran on popular sovereignty , which is the idea that the status of a territory will be determined by the people residing in that territory. Popular sovereignty is neither explicitly pro-slavery or anti-slavery; however, it does nullify the Missouri Compromise . Neither party adopted a firm stance on slavery in the 1848 election; however, the free-soilers made the election about slavery. Consequently, the Whigs and the Democrats developed campaign materials to be sectionally distributed which highlighted their candidate's support and opposition for slavery respectively. The separate campaign materials in this election reveal the growing sectional divide in antebellum America.

Despite the growing sectionalism, Zachary Taylor, a hero of the Mexican-American War and a slaveholding Whig was elected president in 1848 and served for two years before dying in office of natural causes. The Mexican-American War projected Taylor into a position of celebrity and enabled his election in 1848. After his election, Taylor promised not to intercede with Congress’s decision for the organization of the Mexican Cession. Many southerners felt betrayed by Taylor, a slaveowner from Louisiana, as they equated his position with those of a free-soiler. In this time of heightened sectional tensions, southerners believed that if one did not actively protect slavery and its expansion, one supported abolition.

As a direct result of the Mexican Cession, the California Gold Rush began in 1849 which caused a massive frenzy to organize and admit California into the Union. The Missouri Compromise stated that any territory north of the 36°30’ parallel would be free; however, the line would divide California into two sections. California was never a US territory and approved a free constitution, elected a Governor and legislature and applied for statehood by November 1849. Since California did not wish to be divided into two separate states, a new compromise was formed, aptly named the Compromise of 1850. Under the Compromise of 1850 , California was admitted as a free state without deciding the fate of the remainder of the Mexican Cession. Additionally, under this compromise, there was the federal assumption of Texas debt, the abolishment of the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and a stronger fugitive slave law. While controversial, the Compromise of 1850 alleviated the growing tensions over slavery and delayed a full-blown crisis over the issue.

However, in 1854 tensions over slavery once again skyrocketed over the organization of Kansas and Nebraska. While Kansas and Nebraska were not part of the Mexican Cession, their debates over their organization are linked to the Mexican-American War. As stated above, the Mexican-American War re-opened the discussions over how to organize territory, and one of the proposed solutions was popular sovereignty. While the Compromise of 1850 elected not to include popular sovereignty, it reemerged in 1854 with the Kansas-Nebraska Act , where Kansas and Nebraska would be organized using popular sovereignty. The Kansas-Nebraska Act caused Bleeding Kansas , where pro-slavery and anti-slavery Americans flocked to Kansas in an attempt to establish either a slave or free government in that state, which eventually erupted into violence where neighbor killed a neighbor in the name of slavery and abolition. Bleeding Kansas is also the first instance where John Brown , famous for his 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry, used violence to enact his radical abolition vision. Moreover, the Kansas-Nebraska Act propelled future President Abraham Lincoln into the national spotlight. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois’s pet project and popular sovereignty is often associated with Douglas. Lincoln and Douglas engaged in a series of debates in 1858, which mainly focused on popular sovereignty and slavery’s expansion. While Lincoln lost the senatorial election in 1858 to Douglas, he became well known because of the debates, which positioned himself to be the Republican candidate for the Presidential Election of 1860. Additionally, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was the final nail in the coffin for the Whig Party and paved the way for the establishment of the Republican Party, the first prominent anti-slavery party which was rooted in sectionalism.

Ralph Waldo Emerson prophetically wrote, “Mexico will poison us.” The Mexican-American War and the massive territory gained reopened debates over slavery which diminished party alliances and increased sectional alliances. These debates over slavery eventually led to the demise of the Second Party System and paved the way for the rise of Republicanism. Sectional tensions had never been stronger and there were open discussions of disunion which increased as the 1850s progressed. All these tensions and issues would come to head with the Election of 1860 and eventually with the Civil War, where brother fought against brother. To say "Mexico poisoned" the United States is an understatement, the bloodshed during the Civil War rivaled any other American conflict and today we are still in the process of healing wounds that occurred over 150 years ago.

Further Reading:

- So Far From God: the U.S. War with Mexico 1846-1848 : By John S. D. Eisenhower

- A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico : By Amy S. Greenberg

- The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Expansion and the Coming of the Civil War : By Michael F. Holt

- The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War 1848-1861 : By David M. Potter

Hispanic-Americans in the Civil War

Federico Fernández Cavada: Union Ties and Cuban Roots

Tejano Heroes of the Texas Revolution

You may also like.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

A Nation on the Move: Westward Expansion, 1800–1860

The Mexican-American War, 1846–1848

OpenStaxCollege

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the causes of the Mexican-American War

- Describe the outcomes of the war in 1848, especially the Mexican Cession

- Describe the effect of the California Gold Rush on westward expansion

Tensions between the United States and Mexico rapidly deteriorated in the 1840s as American expansionists eagerly eyed Mexican land to the west, including the lush northern Mexican province of California. Indeed, in 1842, a U.S. naval fleet, incorrectly believing war had broken out, seized Monterey, California, a part of Mexico. Monterey was returned the next day, but the episode only added to the uneasiness with which Mexico viewed its northern neighbor. The forces of expansion, however, could not be contained, and American voters elected James Polk in 1844 because he promised to deliver more lands. President Polk fulfilled his promise by gaining Oregon and, most spectacularly, provoking a war with Mexico that ultimately fulfilled the wildest fantasies of expansionists. By 1848, the United States encompassed much of North America, a republic that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

JAMES K. POLK AND THE TRIUMPH OF EXPANSION

A fervent belief in expansion gripped the United States in the 1840s. In 1845, a New York newspaper editor, John O’Sullivan, introduced the concept of “manifest destiny” to describe the very popular idea of the special role of the United States in overspreading the continent—the divine right and duty of white Americans to seize and settle the American West, thus spreading Protestant, democratic values. In this climate of opinion, voters in 1844 elected James K. Polk, a slaveholder from Tennessee, because he vowed to annex Texas as a new slave state and take Oregon.

Annexing Oregon was an important objective for U.S. foreign policy because it appeared to be an area rich in commercial possibilities. Northerners favored U.S. control of Oregon because ports in the Pacific Northwest would be gateways for trade with Asia. Southerners hoped that, in exchange for their support of expansion into the northwest, northerners would not oppose plans for expansion into the southwest.

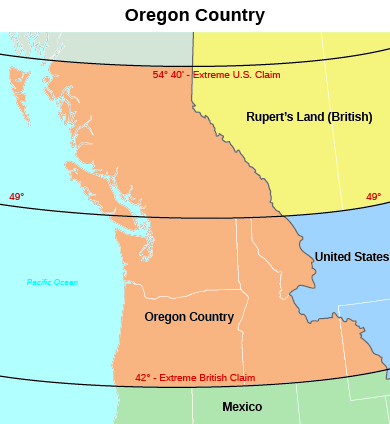

President Polk—whose campaign slogan in 1844 had been “Fifty-four forty or fight!”—asserted the United States’ right to gain full control of what was known as Oregon Country, from its southern border at 42° latitude (the current boundary with California) to its northern border at 54° 40′ latitude. According to an 1818 agreement, Great Britain and the United States held joint ownership of this territory, but the 1827 Treaty of Joint Occupation opened the land to settlement by both countries. Realizing that the British were not willing to cede all claims to the territory, Polk proposed the land be divided at 49° latitude (the current border between Washington and Canada). The British, however, denied U.S. claims to land north of the Columbia River (Oregon’s current northern border) ( [link] ). Indeed, the British foreign secretary refused even to relay Polk’s proposal to London. However, reports of the difficulty Great Britain would face defending Oregon in the event of a U.S. attack, combined with concerns over affairs at home and elsewhere in its empire, quickly changed the minds of the British, and in June 1846, Queen Victoria’s government agreed to a division at the forty-ninth parallel.

In contrast to the diplomatic solution with Great Britain over Oregon, when it came to Mexico, Polk and the American people proved willing to use force to wrest more land for the United States. In keeping with voters’ expectations, President Polk set his sights on the Mexican state of California. After the mistaken capture of Monterey, negotiations about purchasing the port of San Francisco from Mexico broke off until September 1845. Then, following a revolt in California that left it divided in two, Polk attempted to purchase Upper California and New Mexico as well. These efforts went nowhere. The Mexican government, angered by U.S. actions, refused to recognize the independence of Texas.

Finally, after nearly a decade of public clamoring for the annexation of Texas, in December 1845 Polk officially agreed to the annexation of the former Mexican state, making the Lone Star Republic an additional slave state. Incensed that the United States had annexed Texas, however, the Mexican government refused to discuss the matter of selling land to the United States. Indeed, Mexico refused even to acknowledge Polk’s emissary, John Slidell, who had been sent to Mexico City to negotiate. Not to be deterred, Polk encouraged Thomas O. Larkin, the U.S. consul in Monterey, to assist any American settlers and any Californios , the Mexican residents of the state, who wished to proclaim their independence from Mexico. By the end of 1845, having broken diplomatic ties with the United States over Texas and having grown alarmed by American actions in California, the Mexican government warily anticipated the next move. It did not have long to wait.

WAR WITH MEXICO, 1846–1848

Expansionistic fervor propelled the United States to war against Mexico in 1846. The United States had long argued that the Rio Grande was the border between Mexico and the United States, and at the end of the Texas war for independence Santa Anna had been pressured to agree. Mexico, however, refused to be bound by Santa Anna’s promises and insisted the border lay farther north, at the Nueces River ( [link] ). To set it at the Rio Grande would, in effect, allow the United States to control land it had never occupied. In Mexico’s eyes, therefore, President Polk violated its sovereign territory when he ordered U.S. troops into the disputed lands in 1846. From the Mexican perspective, it appeared the United States had invaded their nation.

In January 1846, the U.S. force that was ordered to the banks of the Rio Grande to build a fort on the “American” side encountered a Mexican cavalry unit on patrol. Shots rang out, and sixteen U.S. soldiers were killed or wounded. Angrily declaring that Mexico “has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil,” President Polk demanded the United States declare war on Mexico. On May 12, Congress obliged.

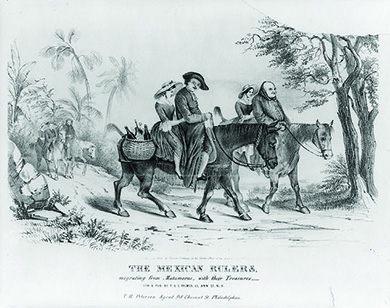

The small but vocal antislavery faction decried the decision to go to war, arguing that Polk had deliberately provoked hostilities so the United States could annex more slave territory. Illinois representative Abraham Lincoln and other members of Congress issued the “Spot Resolutions” in which they demanded to know the precise spot on U.S. soil where American blood had been spilled. Many Whigs also denounced the war. Democrats, however, supported Polk’s decision, and volunteers for the army came forward in droves from every part of the country except New England, the seat of abolitionist activity. Enthusiasm for the war was aided by the widely held belief that Mexico was a weak, impoverished country and that the Mexican people, perceived as ignorant, lazy, and controlled by a corrupt Roman Catholic clergy, would be easy to defeat. ( [link] ).

U.S. military strategy had three main objectives: 1) Take control of northern Mexico, including New Mexico; 2) seize California; and 3) capture Mexico City. General Zachary Taylor and his Army of the Center were assigned to accomplish the first goal, and with superior weapons they soon captured the Mexican city of Monterrey. Taylor quickly became a hero in the eyes of the American people, and Polk appointed him commander of all U.S. forces.

General Stephen Watts Kearny, commander of the Army of the West, accepted the surrender of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and moved on to take control of California, leaving Colonel Sterling Price in command. Despite Kearny’s assurances that New Mexicans need not fear for their lives or their property, and in fact the region’s residents rose in revolt in January 1847 in an effort to drive the Americans away. Although Price managed to put an end to the rebellion, tensions remained high.

Kearny, meanwhile, arrived in California to find it already in American hands through the joint efforts of California settlers, U.S. naval commander John D. Sloat, and John C. Fremont, a former army captain and son-in-law of Missouri senator Thomas Benton. Sloat, at anchor off the coast of Mazatlan, learned that war had begun and quickly set sail for California. He seized the town of Monterey in July 1846, less than a month after a group of American settlers led by William B. Ide had taken control of Sonoma and declared California a republic. A week after the fall of Monterey, the navy took San Francisco with no resistance. Although some Californios staged a short-lived rebellion in September 1846, many others submitted to the U.S. takeover. Thus Kearny had little to do other than take command of California as its governor.

Leading the Army of the South was General Winfield Scott. Both Taylor and Scott were potential competitors for the presidency, and believing—correctly—that whoever seized Mexico City would become a hero, Polk assigned Scott the campaign to avoid elevating the more popular Taylor, who was affectionately known as “Old Rough and Ready.”

Scott captured Veracruz in March 1847, and moving in a northwesterly direction from there (much as Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés had done in 1519), he slowly closed in on the capital. Every step of the way was a hard-fought victory, however, and Mexican soldiers and civilians both fought bravely to save their land from the American invaders. Mexico City’s defenders, including young military cadets, fought to the end. According to legend, cadet Juan Escutia’s last act was to save the Mexican flag, and he leapt from the city’s walls with it wrapped around his body. On September 14, 1847, Scott entered Mexico City’s central plaza; the city had fallen ( [link] ). While Polk and other expansionists called for “all Mexico,” the Mexican government and the United States negotiated for peace in 1848, resulting in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in February 1848, was a triumph for American expansionism under which Mexico ceded nearly half its land to the United States. The Mexican Cession , as the conquest of land west of the Rio Grande was called, included the current states of California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and portions of Colorado and Wyoming. Mexico also recognized the Rio Grande as the border with the United States. Mexican citizens in the ceded territory were promised U.S. citizenship in the future when the territories they were living in became states. In exchange, the United States agreed to assume $3.35 million worth of Mexican debts owed to U.S. citizens, paid Mexico $15 million for the loss of its land, and promised to guard the residents of the Mexican Cession from Indian raids.

As extensive as the Mexican Cession was, some argued the United States should not be satisfied until it had taken all of Mexico. Many who were opposed to this idea were southerners who, while desiring the annexation of more slave territory, did not want to make Mexico’s large mestizo (people of mixed Indian and European ancestry) population part of the United States. Others did not want to absorb a large group of Roman Catholics. These expansionists could not accept the idea of new U.S. territory filled with mixed-race, Catholic populations.

Explore the U.S.-Mexican War at PBS to read about life in the Mexican and U.S. armies during the war and to learn more about the various battles.

CALIFORNIA AND THE GOLD RUSH

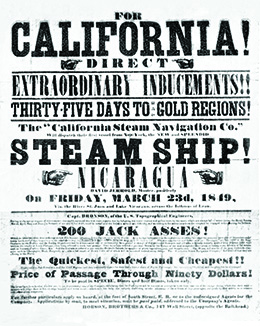

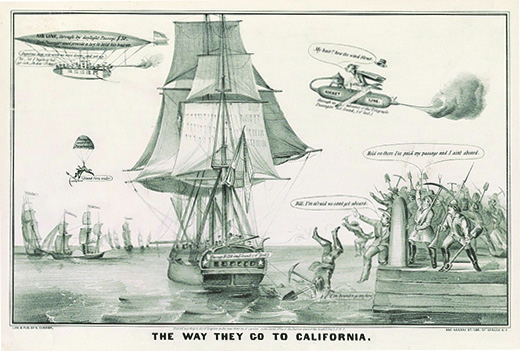

The United States had no way of knowing that part of the land about to be ceded by Mexico had just become far more valuable than anyone could have imagined. On January 24, 1848, James Marshall discovered gold in the millrace of the sawmill he had built with his partner John Sutter on the south fork of California’s American River . Word quickly spread, and within a few weeks all of Sutter’s employees had left to search for gold. When the news reached San Francisco, most of its inhabitants abandoned the town and headed for the American River. By the end of the year, thousands of California’s residents had gone north to the gold fields with visions of wealth dancing in their heads, and in 1849 thousands of people from around the world followed them ( [link] ). The Gold Rush had begun.

The fantasy of instant wealth induced a mass exodus to California. Settlers in Oregon and Utah rushed to the American River. Easterners sailed around the southern tip of South America or to Panama’s Atlantic coast, where they crossed the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific and booked ship’s passage for San Francisco. As California-bound vessels stopped in South American ports to take on food and fresh water, hundreds of Peruvians and Chileans streamed aboard. Easterners who could not afford to sail to California crossed the continent on foot, on horseback, or in wagons. Others journeyed from as far away as Hawaii and Europe. Chinese people came as well, adding to the polyglot population in the California boomtowns ( [link] ).

Once in California, gathered in camps with names like Drunkard’s Bar, Angel’s Camp, Gouge Eye, and Whiskeytown, the “ forty-niners ” did not find wealth so easy to come by as they had first imagined. Although some were able to find gold by panning for it or shoveling soil from river bottoms into sieve-like contraptions called rockers, most did not. The placer gold, the gold that had been washed down the mountains into streams and rivers, was quickly exhausted, and what remained was deep below ground. Independent miners were supplanted by companies that could afford not only to purchase hydraulic mining technology but also to hire laborers to work the hills. The frustration of many a miner was expressed in the words of Sullivan Osborne. In 1857, Osborne wrote that he had arrived in California “full of high hopes and bright anticipations of the future” only to find his dreams “have long since perished.” Although $550 million worth of gold was found in California between 1849 and 1850, very little of it went to individuals.

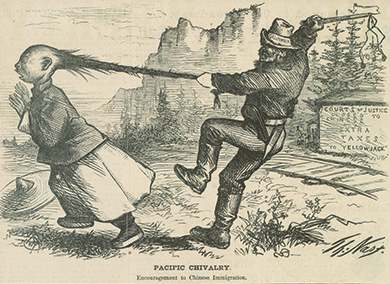

Observers in the gold fields also reported abuse of Indians by miners. Some miners forced Indians to work their claims for them; others drove Indians off their lands, stole from them, and even murdered them. Foreigners were generally disliked, especially those from South America. The most despised, however, were the thousands of Chinese migrants. Eager to earn money to send to their families in Hong Kong and southern China, they quickly earned a reputation as frugal men and hard workers who routinely took over diggings others had abandoned as worthless and worked them until every scrap of gold had been found. Many American miners, often spendthrifts, resented their presence and discriminated against them, believing the Chinese, who represented about 8 percent of the nearly 300,000 who arrived, were depriving them of the opportunity to make a living.

Visit The Chinese in California to learn more about the experience of Chinese migrants who came to California in the Gold Rush era.

In 1850, California imposed a tax on foreign miners, and in 1858 it prohibited all immigration from China. Those Chinese who remained in the face of the growing hostility were often beaten and killed, and some Westerners made a sport of cutting off Chinese men’s queues, the long braids of hair worn down their backs ( [link] ). In 1882, Congress took up the power to restrict immigration by banning the further immigration of Chinese.

As people flocked to California in 1849, the population of the new territory swelled from a few thousand to about 100,000. The new arrivals quickly organized themselves into communities, and the trappings of “civilized” life—stores, saloons, libraries, stage lines, and fraternal lodges—began to appear. Newspapers were established, and musicians, singers, and acting companies arrived to entertain the gold seekers. The epitome of these Gold Rush boomtowns was San Francisco, which counted only a few hundred residents in 1846 but by 1850 had reached a population of thirty-four thousand ( [link] ). So quickly did the territory grow that by 1850 California was ready to enter the Union as a state. When it sought admission, however, the issue of slavery expansion and sectional tensions emerged once again.

Section Summary

President James K. Polk’s administration was a period of intensive expansion for the United States. After overseeing the final details regarding the annexation of Texas from Mexico, Polk negotiated a peaceful settlement with Great Britain regarding ownership of the Oregon Country, which brought the United States what are now the states of Washington and Oregon. The acquisition of additional lands from Mexico, a country many in the United States perceived as weak and inferior, was not so bloodless. The Mexican Cession added nearly half of Mexico’s territory to the United States, including New Mexico and California, and established the U.S.-Mexico border at the Rio Grande. The California Gold Rush rapidly expanded the population of the new territory, but also prompted concerns over immigration, especially from China.

Review Questions

Which of the following was not a reason the United States was reluctant to annex Texas?

According to treaties signed in 1818 and 1827, with which country did the United States jointly occupy Oregon?

During the war between the United States and Mexico, revolts against U.S. control broke out in ________.

Why did whites in California dislike the Chinese so much?

The Chinese were seemingly more disciplined than the majority of the white miners, gaining a reputation for being extremely hard-working and frugal. White miners resented the mining successes that the Chinese earned. They believed the Chinese were unfairly depriving them of the means to earn a living.

The Mexican-American War, 1846–1848 Copyright © 2014 by OpenStaxCollege is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Stanford University

SPICE is a program of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Mexican Perspectives on the Mexican–U.S. War, 1846–1848

This fall, Stanford’s Center for Latin American Studies and SPICE released a new video lecture by Professor Will Fowler , a renowned expert on Mexican history who teaches at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. In the lecture, Fowler presents Mexican perspectives on the Mexican–U.S. War of 1846–1848 and the resulting Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which most Mexicans regard as the most tragic chapter in their history. Professor Fowler also reflects on the consequences of the war for Mexico and how the country remembers the war.

In Mexico, this war is usually referred to as “ la intervención estadounidense en México ” or “ la guerra mexicano-estadounidense ,” which translates into English as the “U.S. Intervention in Mexico” or “the Mexican–U.S. War.”

The video is an excerpt from a longer lecture that Professor Fowler gave on the Mexican–U.S. War of 1846–1848 for the Center for Latin American Studies on July 27, 2021. A free classroom-friendly discussion guide for this video was developed by SPICE Curriculum Consultant Greg Francis and is available for download here . The objectives of the video lecture and curriculum guide are for students to:

- gain an understanding of Mexico’s experience of the Mexican–U.S. War and the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo;

- examine what led to Mexico’s defeat in the war;

- discuss the consequences and legacy of the war from a Mexican perspective; and

- learn the importance of thinking critically about perspectives in their textbooks and classes.

Among the topics of Fowler’s lecture is the legend of the six boy heroes, or the Niños Héroes , that has become the main symbol and memory of the war in Mexico. The two most well-known depictions of the event are a mural on the ceiling of Chapultepec Castle and the Altar a la Patria (Altar to the Homeland) monument, more commonly called the Monumento a los Niños Héroes , both in Mexico City. The guide presents an activity that engages students in an examination of the Niños Héroes .

In addition, the guide engages students in a review of how their history textbooks treat the U.S.–Mexico War. After reading the textbook excerpt, students respond to these questions.

- According to the textbook passage, how did U.S. leaders and the general public react to the U.S. victory in the war?

- What was most surprising or novel to you about the textbook passage?

- Which actors does the U.S. textbook emphasize? How do these differ from the actors that Professor Fowler emphasized?

- Which perspectives does the textbook cover that Professor Fowler did not, and vice versa?

The video lecture and guide were made possible through the support of U.S. Department of Education National Resource Center funding under the auspices of Title VI, Section 602(a) of the Higher Education Act of 1965.

Video Lecture: Mexican Perspectives on the Mexican–U.S. War, 1846–1848

Joe garcia kapp: chicano/latino football trailblazer, teaching diverse perspectives on the vietnam war, visualizing the essential: mexicans in the u.s. agricultural workforce.

Military Records

Mexican War

Pre-World War I U.S. Army Pension and Bounty Land Applications

Search Records Online

Service records.

Scan your Mexican War records in our DC Scanning Room!

Index To Compiled Service Records Of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During The Mexican War (Microfilm Roll #M616, Record Group 94)

- FamilySearch.org (free)

Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War for the states of Arkansas, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and in Mormon Battalion (Microfilm Rolls #M1028, M278, M351, M638, M863, M1970, Record Group 94)

- National Archives Catalog (NAID: 654520) (free)

- Ancestry.com (free from NARA computers) | Ancestry.com ($ - by subscription)

- FamilySearch (free)

- Fold3: Service Records for Arkansas , Mississippi , Pennsylvania , Tennessee , Texas , and Mormon Battalion

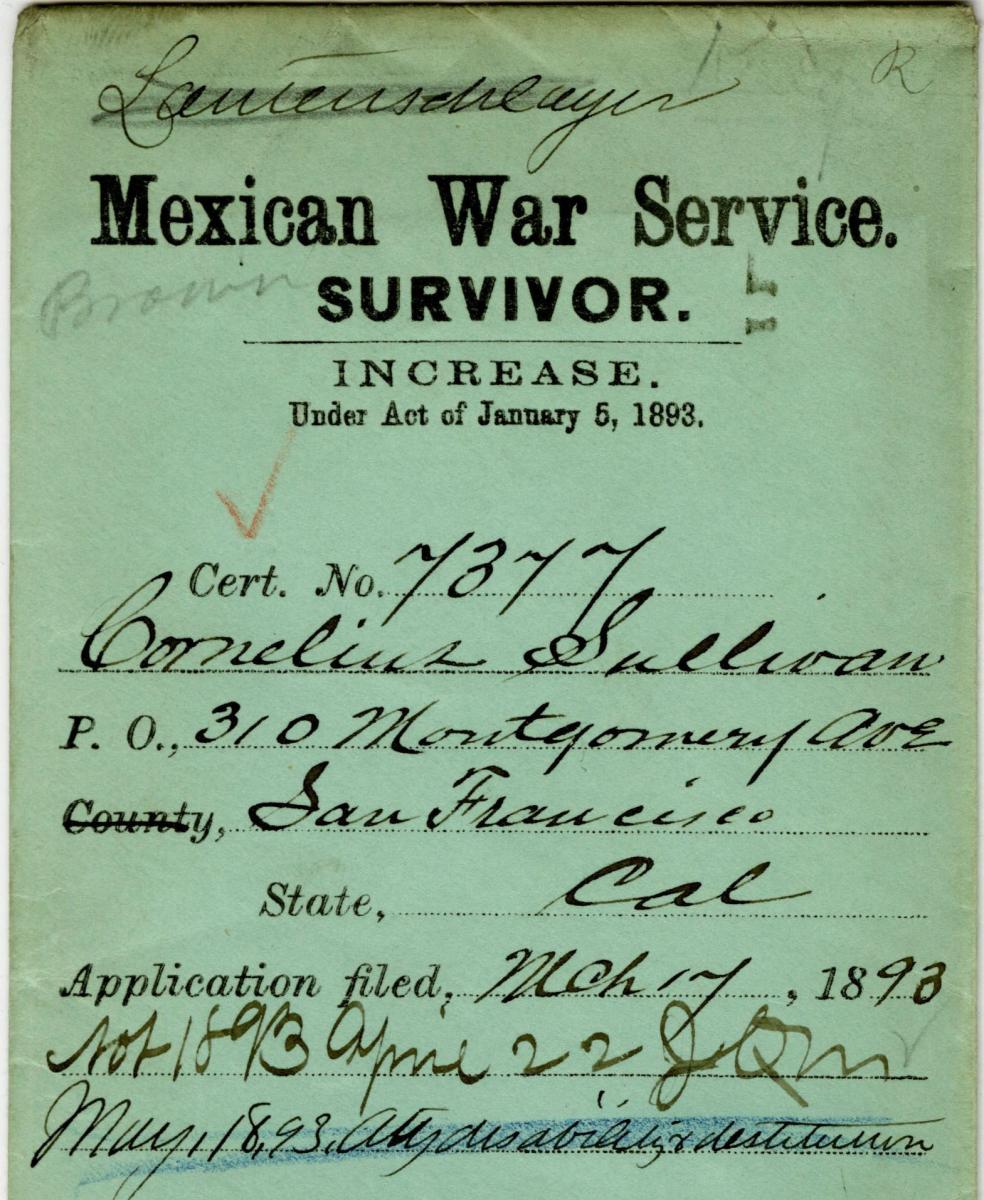

Pension Records

Index to Mexican War Pension Files, 1887-1926 (Microfilm Roll #T317, Record Group 15)

- FamilySearch.org (free)

Selected Pension Application Files Relating to the Mormon Battalion, Mexican War, 1846-1848 (Microfilm Roll #T1196, Record Group 15)

- National Archives Catalog (NAID: 1104361) (free)

Case Files of Mexican War Pension Applications, ca. 1887 - ca. 1926 (Microfilm Roll #T317, Record Group 15)

- National Archives Catalog (NAID: 1104361) (free)

Index to Pension Application Files of Remarried Widows Based on Service in the War of 1812, Indian Wars, Mexican War, and Regular Army before 1861 , (Microfilm Roll #M1784, Record Group 15)

- FamilySearch.org (free)

Killed and Wounded

Returns of Killed and Wounded in Battles or Engagements with Indians, British Troops, and Mexican Troops, compiled 1850 - 1851, documenting the period 1790 - 1848 (Microfilm Roll #M1832, Record Group 94)

Other Resources

" Monuments, Manifest Destiny, and Mexico " Michael Dear's article which tells the story of the survey of the U.S.-Mexico border following the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. From NARA's publication Prologue .

Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo Digitized version of the original document that ended the Mexican-American War.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo A Teaching with Documents lesson plan about the treaty that ended the Mexican-American War.

A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexican War A web site created by a collaboration between the Center for Greater Southwestern Studies and the Library at the University of Texas at Arlington for both scholars and teachers.

A Guide to the Mexican War This guide provides links to digital materials related to the Mexican War that are available on the Library of Congress web site.

The Mexican-American War "This web site presents a historical overview of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), as well as primary documents and images related to the conflict."

Mexican War The Texas State Historical Association offers this chapter from The Handbook of Texas .

Mexican War Dead or Veterans From the American Battle Monuments Commission, this site remembers soldiers from the Mexican War who are buried in the Mexico City National Cemetery.

Robert E. Lee Mexican War Maps An online exhibit of 30 original military maps owned by Robert E. Lee from the holdings of the Virginia Military Institute.

U.S.-Mexican War (1846-1848) This PBS site chronicles the events of the border disputes through multiple points of view to provide an enlightened perspective on the subject. Includes histories, articles, essays, a timeline, and a moderated discussion area for visitors.

U.S.-Mexican War A site rich in the history of the war, by the Descendants of Mexican War Veterans. Read battle plans and orders, peruse letters, and see images of the war and veterans.

U.S.-Mexican War: The Zachary Taylor Encampment in Corpus Christi Created by volunteers at the Corpus Christi Public Libraries, this informational site offers images, letters, newspaper accounts, and more, of the Mexican War in the Corpus Christi, Texas, area.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Art of the Americas to World War I

Course: art of the americas to world war i > unit 7, the mexican-american war: 19th-century american art in context.

- The Missouri Compromise and the dangerous precedent of appeasement

- Nativism and the Know-Nothing Party

- The World’s Columbian Exposition: Introduction

- The World’s Columbian Exposition: The White City and fairgrounds

- The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Midway

- Nast and Reconstruction, understanding a political cartoon final

- John Brown’s “tragic prelude” to the U.S. Civil War

A forgotten war with unforgettable consequences

Comparing mexican and american societies before the war, cotton, texas, and manifest destiny, the war begins, the progress of the war, “a wicked war”.

“I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico.” —Ulysses S. Grant, 1879

Consequences of the Mexican-American War

- War dead as a percentage of total U.S. population. .057% of the U.S. population died as a result of the Mexican-American War.

- See the Historical Marker Database for estimates.

- For Grant’s quote concerning the “wicked war,” see John Russell Young, Around the World with General Grant (New York: American News, 1879), 2:447–48.

- James Oles, Art and Architecture in Mexico (Thames and Hudson, 2013), 155.

Additional resources:

Want to join the conversation.

Mexican-American War

By William V. Bartleson

Despite taking place in the American Southwest and Central America, the Mexican-American War (1845-48) had significant ties to the Philadelphia area. As one of the most populous urban centers in the country, the Delaware Valley became a hotbed of activity for one of the most controversial wars in American history.

War between the United States and Mexico followed the admission of Texas as the twenty-eighth state of the United States in December 1845. This exacerbated preexisting tension with the Mexican government, which never recognized Texas independence, American annexation of Texas, nor the proposed border of the new state at the Rio Grande River. After an armed clash between U.S. forces led by General Zachary Taylor (1784-1850) and Mexican troops in the disputed area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, Congress declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846, and authorized President James K. Polk (1795-1849) to call up fifty thousand volunteers to join the existing U.S. Army.

In Philadelphia and elsewhere, the controversy surrounding the coming and course of the Mexican-American War illustrated the widening divide in American society over the issues of territorial conquest and the expansion of slavery. Initially, support for the war was strong in the mid-Atlantic states, and Philadelphia’s historic ties to the American Revolution made it a centerpiece for pro-war patriotism by politicians and cultural figures who viewed Manifest Destiny as the legacy of American independence. The Philadelphia North American, a “penny press” newspaper owned by George R. Graham (1813-1894), reported news from Mexico and supported “Mr. Polk’s War” in editorials. However, Philadelphia’s active abolitionist community opposed the war as a vehicle for expanding slavery into new territory. In June 1846, The National Anti – Slavery Standard, published in Philadelphia, strongly opposed the war based on its abolitionist views against expansion of slavery into the West.

The war was equally controversial in New Jersey and Delaware. In New Jersey, a strong Whig Party presence in state politics made unified action difficult. In October 1847, a convention of New Jersey Whigs condemned the Polk administration’s drive for territorial annexation. Niles’ National Register reported that their resolutions “strongly denounced the present national administration for violations of the liberties of the people and interests of the Union, especially in having made war without consulting the people or their representatives, and that too, for party purposes.” This sentiment was common across New Jersey. When New Jersey Governor Charles C. Stratton (1796-1859) responded to President Polk’s call to organize volunteers for service, the turnout was so meager that only a New Jersey Battalion of Volunteers could be formed, not a regiment. In Delaware, opposition to the war ran so strong that only a dozen residents volunteered to serve.

During the opening stages of mobilization, Philadelphia joined other cities in holding a pro-war rally, but this fervor was not universal. In response to impassioned opposition speeches delivered by Whig politician Henry Clay (1777-1852) in the autumn of 1847, anti-war rallies took place in Philadelphia and Trenton, New Jersey.

The “Killers” in the Ranks

Following the declaration of war, Pennsylvania Governor Francis R. Shunk (1788-1848) called for forming six regiments to serve in the U.S. Army. In contrast to the tepid response in New Jersey and Delaware, patriotic enthusiasm quickly satisfied the quotas, and several full companies had to be turned away. Recruits from the Keystone State were organized into the First and Second Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiments. Of the ten companies constituting the First Regiment, six hailed from Philadelphia, including the City Guards of Philadelphia, The Philadelphia Light Guards, and the Cadwalader Grays. The Second Regiment became home to Company F, known as the Philadelphia Rangers.

Along with the patriotism that motivated Philadelphia men to serve, the disorder and violence that had been hallmarks of Philadelphia during the 1830s and 1840s also traveled west with the volunteers who mustered in Harrisburg and then proceeded to Pittsburgh en route to Mexico. In Pittsburgh, soldiers from Company D (The City Guard) invaded a local theater in an incident that ended in a violent clash with police. This riotous behavior continued later New Orleans, where a soldier claiming membership in the notorious Philadelphia “Killers” gang attacked citizens and destroyed property across the city. Later, a faction of the Killers intimidated Company D’s commanding officer, Captain Joseph Hill, who temporarily fled the regiment in April 1847. Another veteran of Philadelphia street violence led the Pennsylvania volunteer regiments after their transport down the Mississippi River and across the Gulf to Lobos, Mexico, where they landed in February 1846. Major General Robert Patterson, a former Pennsylvania militia commander, had led troops against rioters during the destruction of the Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia in 1838. In Mexico, he commanded the Second Division of a brigade led by Brigadier General Gideon J. Pillow (1806-1878), which took in the Pennsylvania volunteers.

The Pennsylvania Volunteers in Mexico

The fighting men from Philadelphia saw their first significant combat at the Siege of Veracruz in March 1847. In the thunderous twenty-day siege, the Pennsylvania regiments lost the service of fifteen soldiers to enemy cannon fire, including three who were killed. After the fall of Veracruz, the regiments moved into the Mexican interior and saw action again in April at the Battle of Cerro Gordo as part of an assault on Mexican artillery at Jarero, south of the Mexican encampment near Vasquez. Despite the ferocity of the engagement, the regiments suffered few casualties. For the next two months, they continued inland toward Mexico City, fighting guerillas, the elements, and disease.

In September 1847, the Pennsylvania Regiments were split by General Winfield Scott (1786-1866) to prepare for the assault on Mexico City. While three of the Philadelphia companies were reassigned to garrison duty at Puebla, the Reading Artillery of Company A and the Philadelphia Rangers of the Second Regiment proceeded with the main army toward Mexico City. Both companies saw heavy fighting at close range with the Mexican defenders. In two days of combat, the Second Regiment suffered its worst losses of the conflict with eight men killed and eighty-nine wounded.

Mexican troops flushed out of Mexico City and led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna (1794-1876) next attacked Puebla, where the Philadelphia remnant of the First Regiment had been stationed. A nearly month-long siege ensued began in September 14, 1847. Forces under Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Black (1816-1862), a Pittsburgh native and future Pennsylvania congressional representative, faced repeated assaults and dwindling supplies until Santa Anna withdrew his troops on October 12. The Siege of Puebla was not only the Pennsylvanians’ finest performance, it was also the most costly. The First Regiment suffered fifty-five casualties with twenty-one men killed in action. In December 1847, the survivors marched to Mexico City, where they reunited with the Second Regiment to much fanfare and celebration.

Philadelphia-area soldiers also served in areas of the war other than Mexico. A veteran of the War of 1812, Rear Admiral William Mervine (1791-1868), commanded the USS Savannah in the Pacific, and his Marine detachment captured the city of Monterey in July 1846. Samuel Francis Du Pont (1803-65) of the famed DuPont family of Delaware commanded the blockade of California and achieved the rank of rear admiral. Future U.S. senator from New Jersey Commodore Robert Stockton (1795-1866) was instrumental in the capture of Monterey and Pueblo de Los Ángeles in California. Between July 1846 and January 1847, Stockton served as military governor of California.

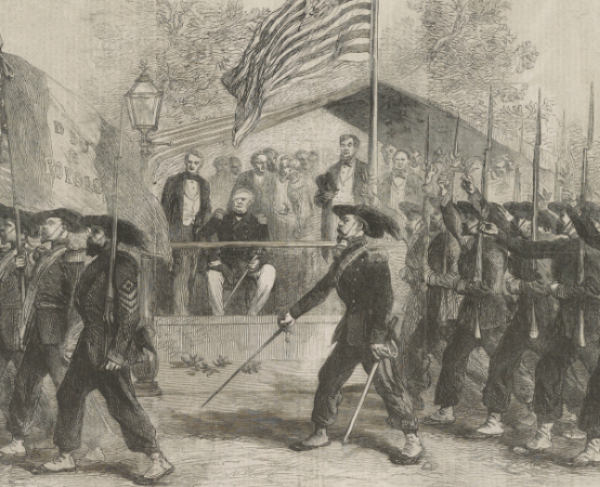

In Mexico, Philadelphia native and Brigadier General Persifor Frazer Smith (1798–1858) served as military governor during the occupation of Mexico City, when duty for the Pennsylvania volunteer regiments consisted of a mixture of drill, boredom, and sporadic chaos as Mexican guerilla units harassed U.S. forces. When U.S. troops withdrew on March 6, 1848, the regiments’ long journey home took them from Mexico back to New Orleans, then up the Mississippi River and Ohio Rivers to Pittsburgh, where they arrived on July 11, 1848. The Pittsburgh units mustered out of service quickly, but the Philadelphia companies resolved to end their service at home. Between July 27 and August 5, parades, speeches, banquets, and community events across the Delaware Valley marked their return. Of the 2,415 men who served in the Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiments, 477 died in Mexico or in transport. Fifty-two were killed in combat. New Jersey’s volunteers saw little combat in Mexico and returned to the Garden State in July 1848. Delaware’s volunteers, who took part in the Battle of Huanmantla in October 1847, returned in August 1848, having suffered a single casualty.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War on February 2, 1848, and expanded the territory of the United States by 525,000 square miles. However, the costly victory, earned after two years of ferocious combat, exacerbated the simmering tensions throughout the country. Volunteers from Philadelphia and the surrounding region participated in the military actions while local citizens debated the war’s political and moral ramifications, making Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley a microcosm of the conflict.

William V. Bartleson is an independent scholar of military history who has worked with the New Jersey National Guard Militia Museum and the Center for Veterans Oral history. He is a member of Phi Alpha Theta . ( Author information current at time of publication .)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Army of Occupation Camp

Library of Congress

Philadelphia native and Brigadier General Persifor Frazer Smith (1798–1858) served as military governor during the occupation of Mexico City until the withdrawal of U.S. troops on March 6, 1848. Duty for the Pennsylvania volunteer regiments consisted of a mixture of drill, boredom, and sporadic chaos as Mexican guerilla units harassed U.S. forces. Soldiers from Philadelphia’s Company C produced a bi-weekly publication, the Flag of Freedom, to inform garrison troops of local sites, current events, and the progress of the war. The newspaper remained the only soldier-published work by U.S. soldiers during the war.

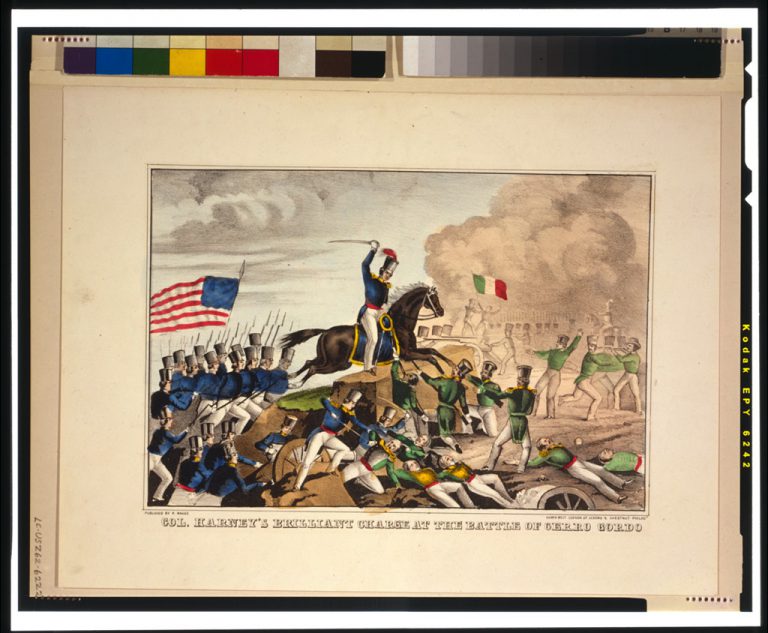

General Winfield Scott at the Battle of Buena Vista

During several engagement of the Mexican-American War, the Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiments served directly under General Winfield Scott, depicted on horseback in this lithograph titled "A Little More Grape Capt. Bragg," by Nathanial Currier. After the Siege at Puebla in 1847, General Scott presented the 1st and 2nd Regiments with their own regimental colors to show his appreciation for their efforts and sacrifice.

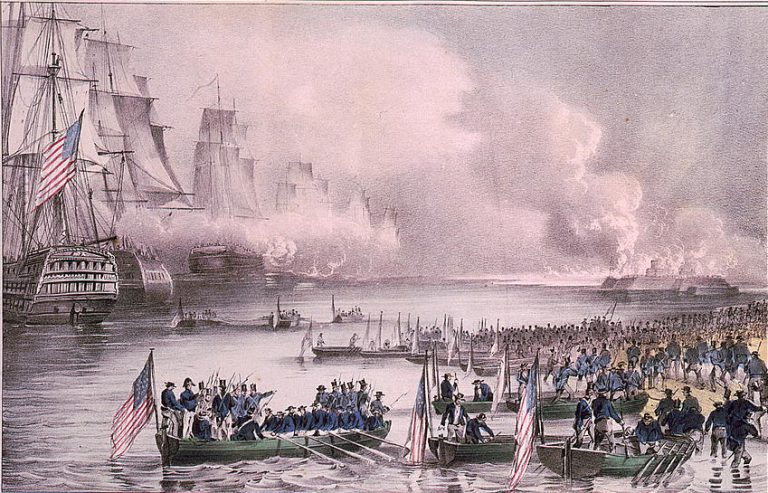

Beachhead at Veracruz

The First and Second Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiments, the New Jersey Battalion of Volunteers, and the Delaware Squad of volunteers all passed through the beachhead at the port of Veracruz, depicted here.

Despite the opposition to the war, New Jersey eventually furnished troops for the war. In May 1846, New Jersey Governor Charles C. Stratton (1796-1859), responded to President Polk’s call for state regiments by asking New Jersey citizens to “organize uniform companies and other citizens of the state to enroll themselves.” The turnout of those willing to serve was so lacking only a “New Jersey Battalion of Volunteers” could be formed, not a regiment. Consisting of four companies and led by Captain M. Knowlton, left for Vera Cruz, Mexico on September 29, 1847. Much like their Philadelphia counterparts, troops from New Jersey displayed riotous behavior during the journey. The New Jersey volunteers saw little combat in Mexico and returned to the Garden State in July 1848.

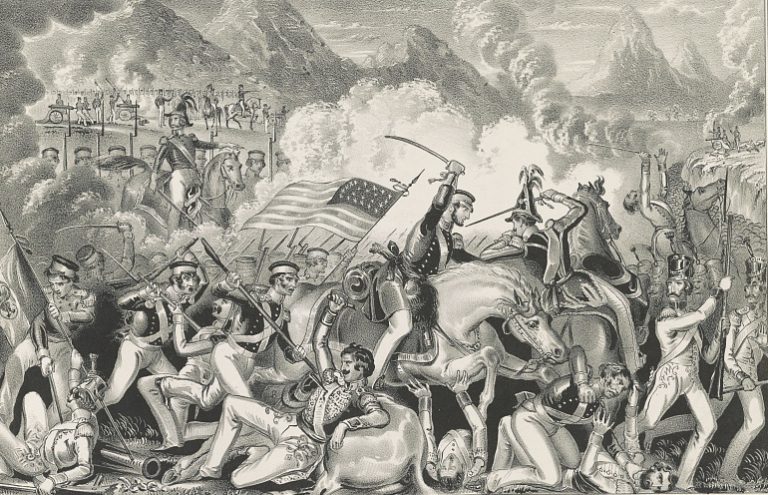

Battle of Buena Vista

In Delaware, opposition to the war made the raising of a state regiment for U.S. Army service impossible. However, a dozen residents answered President Polk’s call for troops and formed the Delaware Squad. The Delaware Squad was attached to the 5th Indiana Regiment of Indiana Volunteers under the command of future senator and American Civil War general James Lane (1814-1866) and took part in the Battle of Buena Vista (pictured) in February 1847 and the Battle of Huanmata in October 1847. The Delaware Squad returned to the United States in August 1848, having suffered a single casualty.

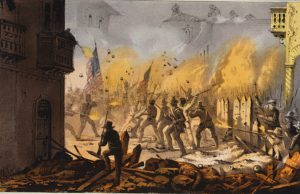

Battle of Cerra Gordo

After their first significant combat at the Siege of Veracruz, where they lost 15 soldiers to enemy cannon fire, the Pennsylvania regiments saw action again at the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 17, 1847. Despite the ferocity of the engagement, depicted here in a lithograph published in Philadelphia, the regiments suffered few casualties. For the next two months, they continued inland toward Mexico City, fighting guerillas, the elements, and disease typical of camp life.

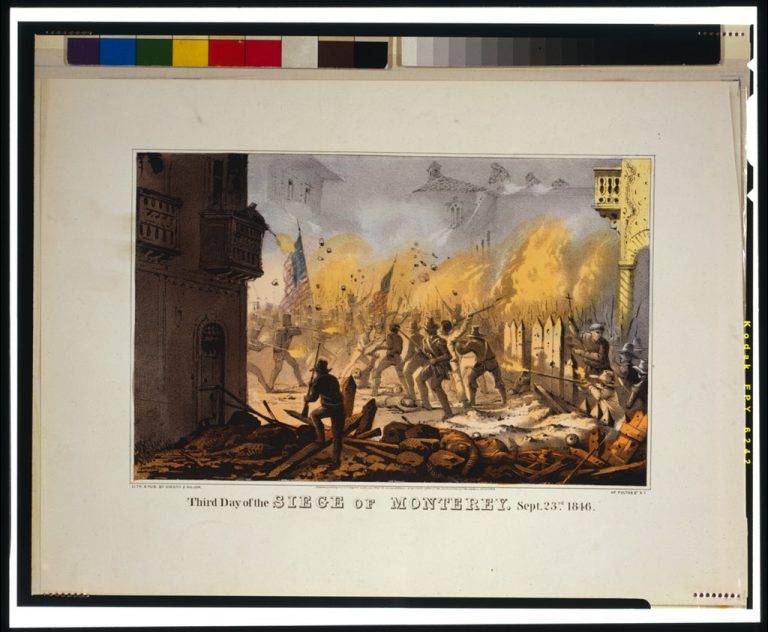

Siege of Monterey

Several Delaware Valley residents took part in the September 1846 siege and occupation of Monterey, depicted in this lithograph. Philadelphia native Rear Admiral William Mervine (1791-1868) commanded the USS Savannah in the Pacific, and his Marine detachment captured the city of Monterey in July 1846. Samuel Francis Du Pont (1803-65) of Delaware commanded the blockade of California. Future U.S. senator from New Jersey Commodore Richard Stockton (1795-1866) was instrumental in the capture of Monterey and Pueblo de Los Ángeles in California. Between July 1846 and January 1847, Stockton served as military governor of California.

Mexican War Monument

At Philadelphia National Cemetery in Northwest Philadelphia, the Mexican War Monument marks the burial site for 38 who died in the conflict. Their remains were moved to the national cemetery in 1927, after the closing of their original burial place, Glenwood Cemetery at Twenty-Seventh Street and Ridge Avenue in North Philadelphia.

Philadelphia National Cemetery, at Haines Street and Limekiln Pike north of Germantown, was among 14 national cemeteries established in 1862, during the Civil War. In its first year, it served as a burial place for soldiers who died in Philadelphia hospitals. In addition to the Mexican War Monument, the cemetery has a Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument, commemorating soldiers and sailors whose remains were reinterred after the Civil War, and a Revolutionary War Memorial.

Related Topics

- Greater Philadelphia

- Philadelphia and the World

- Philadelphia and the Nation

Time Periods

- Nineteenth Century to 1854

- Northeast Philadelphia

- Mexicans and Mexico

- National Guard

- Philadelphia Navy Yard

- Slavery and the Slave Trade

- Spanish-American Revolutions

- Irish (The) and Ireland

Related Reading

Hackenburg, Randy W. Pennsylvania in the War With Mexico . Shippensburg, Pa.: White Mane Publishing Co., 1992.

Schroeder, John H. Mr. Polk’s War: American Opposition and Dissent, 1846-1848 . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973.

Millett, Allan Reed and Peter Maslowski. For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America . Rev. and expanded. New York and Toronto: Free Press, 1994.

Smith, Justin Harvey. The War With Mexico . Gloucester, Mass.: P. Smith, 1963.

Tucker, Spencer, et al. The Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War: A Political, Social, and Military History . Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2013.

Related Collections

- Militia Resource Guide 1815-1870 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission 300 N. Street, Harrisburg, Pa.

- Mexican War (1846-1848) Document Collection Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission 300 N. Street, Harrisburg, Pa

Related Places

- Independence Square (site of pro-war and anti-war rallies and victory celebration)

- Mexican War Monument, Philadelphia National Cemetery (near Section P)

- State of Pennsylvania Mexican War Monument

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Play written for Philly butcher shop a lesson in Mexican-American history (WHYY, February 24, 2016)

- Geary Family Papers (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Digital Library)

- A Forgotten American Hero: Captain John B. Page (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Mexican-American War in a nutshell (National Constitution Center)

- Santa Anna's Proclamation, published in Philadelphia, 1847 (Library of Congress)

- The Storming of Chapulapec, Song of War, published in Philadelphia (Library of Congress)

- A Guide to the Mexican War (Library of Congress)

- The U.S.-Mexican War (PBS)

- Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (National Park Service)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Mexican-American War Begins. On April 25, 1846, Mexican cavalry attacked a group of U.S. soldiers in the disputed zone under the command of General Zachary Taylor, killing about a dozen. They ...