- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 07 August 2009

Primary abdominal ectopic pregnancy: a case report

- Recep Yildizhan 1 ,

- Ali Kolusari 1 ,

- Fulya Adali 2 ,

- Ertan Adali 1 ,

- Mertihan Kurdoglu 1 ,

- Cagdas Ozgokce 1 &

- Numan Cim 1

Cases Journal volume 2 , Article number: 8485 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

17 Citations

Metrics details

Introduction

We present a case of a 13-week abdominal pregnancy evaluated with ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old woman, (gravida 2, para 1) suffering from lower abdominal pain and slight vaginal bleeding was transferred to our hospital. A transabdominal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging were performed. The diagnosis of primary abdominal pregnancy was confirmed according to Studdiford's criteria. A laparatomy was carried out. The placenta was attached to the mesentery of sigmoid colon and to the left abdominal sidewall. The placenta was dissected away completely and safely. No postoperative complications were observed.

Ultrasound examination is the usual diagnostic procedure of choice. In addition magnetic resonance imaging can be useful to show the localization of the placenta preoperatively.

Abdominal pregnancy, with a diagnosis of one per 10000 births, is an extremely rare and serious form of extrauterine gestation [ 1 ]. Abdominal pregnancies account for almost 1% of ectopic pregnancies [ 2 ]. It has reported incidence of one in 2200 to one in 10,200 of all pregnancies [ 3 ]. The gestational sac is implanted outside the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. The maternal mortality rate can be as high as 20% [ 3 ]. This is primarily because of the risk of massive hemorrhage from partial or total placental separation. The placenta can be attached to the uterine wall, bowel, mesentery, liver, spleen, bladder and ligaments. It can be detach at any time during pregnancy leading to torrential blood loss [ 4 ]. Accurate localization of the placenta pre-operatively could minimize blood loss during surgery by avoiding incision into the placenta [ 5 ]. It is thought that abdominal pregnancy is more common in developing countries, probably because of the high frequency of pelvic inflammatory disease in these areas [ 6 ]. Abdominal pregnancy is classified as primary or secondary. The diagnosis of primary abdominal pregnancy was confirmed according to Studdiford's criteria [ 7 ]. In these criteria, the diagnosis of primary abdominal pregnancy is based on the following anatomic conditions: 1) normal tubes and ovaries, 2) absence of an uteroplacental fistula, and 3) attachment exclusively to a peritoneal surface early enough in gestation to eliminate the likelihood of secondary implantation. The placenta sits on the intra-abdominal organs generally the bowel or mesentery, or the peritoneum, and has sufficient blood supply. Sonography is considered the front-line diagnostic imaging method, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) serving as an adjunct in cases when sonography is equivocal and in cases when the delineation of anatomic relationships may alter the surgical approach [ 8 ]. We report the management of a primary abdominal pregnancy at 13 weeks.

The patient was a 34-year-old Turkish woman, gravida 2 para 1 with a normal vaginal delivery 15 years previously. Although she had not used any contraceptive method afterwards, she had not become pregnant. She was transferred to our hospital from her local clinic at the gestation stage of 13 weeks because of pain in the lower abdomen and slight vaginal bleeding. She did not know when her last menstrual period had been, due to irregular periods. At admission, she presented with a history of abdominal distention together with steadily increasing abdominal and back pain, weakness, lack of appetite, and restlessness with minimal vaginal bleeding. She denied a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted disease, surgical operations, or allergies. Blood pressure and pulse rate were normal. Laboratory parameters were normal, with a hemoglobin concentration of 10.0 g/dl and hematocrit of 29.1%. Transvaginal ultrasonographic scanning revealed an empty uterus with an endometrium 15 mm thick. A transabdominal ultrasound (Figure 1 ) examination demonstrated an amount of free peritoneal fluid and the nonviable fetus at 13 weeks without a sac; the placenta measured 58 × 65 × 67 mm. Abdominal-Pelvic MRI (Philips Intera 1.5T, Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) in coronal, axial, and sagittal planes was performed especially for localization of the placenta before she underwent surgery. A non-contrast SPAIR sagittal T2-weighted MRI strongly suggested placental invasion of the sigmoid colon (Figure 2 ).

Pelvic ultrasound scanning . Diffuse free intraperitoneal fluid was seen around the fetus and small bowel loops.

T2W SPAIR sagittal MRI of lower abdomen demonstrating the placental invasion . Placenta (a) , invasion area (b) , sigmoid colon (c) , uterine cavity (d) .

Under general anesthesia, a median laparotomy was performed and a moderate amount of intra-abdominal serohemorrhagic fluid was evident. The placenta was attached tightly to the mesentery of sigmoid colon and was loosely adhered to the left abdominal sidewall (Figure 3 ). The fetus was localized at the right of the abdomen and was related to the placenta by a chord. The placenta was dissected away completely and safely from the mesentery of sigmoid colon and the left abdominal sidewall. Left salpingectomy for unilateral hydrosalpinx was conducted. Both ovaries were conserved. After closure of the abdominal wall, dilatation and curettage were also performed but no trophoblastic tissue was found in the uterine cavity. As a management protocol in our department, we perform uterine curettage in all patients with ectopic pregnancy gently at the end of the operation, not only for the differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, but also to help in reducing present or possible postoperative vaginal bleeding.

Fetus, placenta and bowels .

The patient was awakened, extubated, and sent to the room. The patient was discharged on post-operative day five with the standard of care at our hospital.

In the present case, we were able to demonstrate primary abdominal pregnancy according to Studdiford's criteria with the use of transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound examination and MRI. In our case, both fallopian tubes and ovaries were intact. With regard to the second criterion, we did not observe any uteroplacental fistulae in our case. Since abdominal pregnancy at less than 20 weeks of gestation is considered early [ 9 ], our case can be regarded as early, and so we dismissed the possibility of secondary implantation.

The recent use of progesterone-only pills and intrauterine devices with a history of surgery, pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted disease, and allergy increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Our patient had not been using any contraception, and did not report a history of the other risk factors.

The clinical presentation of an abdominal pregnancy can differ from that of a tubal pregnancy. Although there may be great variability in symptoms, severe lower abdominal pain is one of the most consistent findings [ 10 ]. In a study of 12 patients reported by Hallatt and Grove [ 11 ], vaginal bleeding occurred in six patients.

Ultrasound examination is the usual diagnostic procedure of choice, but the findings are sometimes questionable. They are dependent on the examiner's experience and the quality of the ultrasound. Transvaginal ultrasound is superior to transabdominal ultrasound in the evaluation of ectopic pregnancy since it allows a better view of the adnexa and uterine cavity. MRI provided additional information for patients who needed precise diagnosing. After the diagnosis of abdominal pregnancy became definitive, it was essential to determine the localization of the placenta. Meanwhile, MRI may help in surgical planning by evaluating the extent of mesenteric and uterine involvement [ 12 ]. Non-contrast MRI using T 2 -weighted imaging is a sensitive, specific, and accurate method for evaluating ectopic pregnancy [ 13 ], and we used it in our case.

Removal of the placental tissue is less difficult in early pregnancy as it is likely to be smaller and less vascular. Laparoscopic removal of more advanced abdominal ectopic pregnancies, where the placenta is larger and more invasive, is different [ 14 ]. Laparoscopic treatment must be considered for early abdominal pregnancy [ 15 ].

Complete removal of the placenta should be done only when the blood supply can be identified and careful ligation performed [ 11 ]. If the placenta is not removed completely, it has been estimated that the remnant can remain functional for approximately 50 days after the operation, and total regression of placental function is usually complete within 4 months [ 16 ].

In conclusion, ultrasound scanning plus MRI can be useful to demonstrate the anatomic relationship between the placenta and invasion area in order to be prepared preoperatively for the possible massive blood loss.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Spectral Presaturation Attenuated by Inversion Recovery.

Yildizhan R, Kurdoglu M, Kolusari A, Erten R: Primary omental pregnancy. Saudi Med J. 2008, 29: 606-609.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ludwig M, Kaisi M, Bauer O, Diedrich K: The forgotten child-a case of heterotopic, intra-abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy carried to term. Hum Reprod. 1999, 14: 1372-1374. 10.1093/humrep/14.5.1372.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Alto WA: Abdominal pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 1990, 41: 209-214.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ang LP, Tan AC, Yeo SH: Abdominal pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Singapore Med J. 2000, 41: 454-457.

Martin JN, Sessums JK, Martin RW, Pryor JA, Morrison JC: Abdominal pregnancy: current concepts of management. Obstet Gynecol. 1988, 71: 549-557.

Maas DA, Slabber CF: Diagnosis and treatment of advanced extra-uterine pregnancy. S Afr Med J. 1975, 49: 2007-2010.

Studdiford WE: Primary peritoneal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1942, 44: 487-491.

Google Scholar

Wagner A, Burchardt A: MR imaging in advanced abdominal pregnancy. Acta Radiol. 1995, 36: 193-195. 10.3109/02841859509173377.

Gaither K: Abdominal pregnancy-an obstetrical enigma. South Med J. 2007, 100: 347-348.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Onan MA, Turp AB, Saltik A, Akyurek N, Taskiran C, Himmetoglu O: Primary omental pregnancy: case report. Hum Reprod. 2005, 20: 807-809. 10.1093/humrep/deh683.

Hallatt JG, Grove JA: Abdominal pregnancy: a study of twenty-one consecutive cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985, 152: 444-449.

Malian V, Lee JH: MR imaging and MR angiography of an abdominal pregnancy with placental infarction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001, 177: 1305-1306.

Yoshigi J, Yashiro N, Kinoshito T, O'uchi T, Kitagaki H: Diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy with MRI: efficacy of T2-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2006, 5: 25-32. 10.2463/mrms.5.25.

Kwok A, Chia KKM, Ford R, Lam A: Laparoscopic management of a case of abdominal ectopic pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002, 42: 300-302. 10.1111/j.0004-8666.2002.300_1.x.

Pisarska MD, Casson PR, Moise KJ, Di Maio DJ, Buster JE, Carson SA: Heterotopic abdominal pregnancy treated at laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1998, 70: 159-160. 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00104-6.

France JT, Jackson P: Maternal plasma and urinary hormone levels during and after a successful abdominal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980, 87: 356-362.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Yuzuncu Yil University, Van, Turkey

Recep Yildizhan, Ali Kolusari, Ertan Adali, Mertihan Kurdoglu, Cagdas Ozgokce & Numan Cim

Department of Radiology, Women and Child Hospital, Van, Turkey

Fulya Adali

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Recep Yildizhan .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors were involved in patient's care. RY, AK and FA analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the clinical and radiological findings of the patient and prepared the manuscript. EA, MK and CO edit and coordinated the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Yildizhan, R., Kolusari, A., Adali, F. et al. Primary abdominal ectopic pregnancy: a case report. Cases Journal 2 , 8485 (2009). https://doi.org/10.4076/1757-1626-2-8485

Download citation

Received : 12 January 2009

Accepted : 19 June 2009

Published : 07 August 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.4076/1757-1626-2-8485

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sigmoid Colon

- Ectopic Pregnancy

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- Lower Abdominal Pain

- Transabdominal Ultrasound

Cases Journal

ISSN: 1757-1626

A Live 13 Weeks Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report

Affiliations.

- 1 Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, SAU.

- 2 Obstetrics and Gynecology, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, SAU.

- PMID: 33209549

- PMCID: PMC7667717

- DOI: 10.7759/cureus.10993

Ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy that occurs outside the uterus, most commonly in the fallopian tube. It is usually suspected if a pregnant woman experiences any of these symptoms during the first trimester: vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and amenorrhea. An elevated BhCG level above the discriminatory zone (2000 mIU/ml) with an empty uterus on a transvaginal ultrasound is essential for confirming ectopic pregnancy diagnosis. Such pregnancy can be managed medically with methotrexate or surgically via laparoscopy or laparotomy depending on the hemodynamic stability of the patient and the size of the ectopic mass. In this case study, we report on a 38-year-old woman, G3P2+0 who presented to King Abdulaziz University Hospital's emergency department with a history of amenorrhea for three months. She was unsure of her last menstrual period and her main complaint was generalized abdominal pain. Upon examination, she was clinically unstable and her abdomen was tender on palpation and diffusely distended. Her BhCG level measured 113000 IU/ml and a bedside pelvic ultrasound showed an empty uterine cavity, as well as a live 13 weeks fetus (measured by CRL). The fetus was seen floating in the abdominal cavity and surrounded by a moderate amount of free fluid, suggestive of ruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy. The patient's final diagnosis was live ruptured 13 weeks tubal ectopic pregnancy which was managed successfully through an emergency laparotomy with a salpingectomy.

Keywords: ectopic pregnancy; ruptured ectopic pregnancy; tubal pregnancy.

Copyright © 2020, Gari et al.

Publication types

- Case Reports

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Global health

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 16, Issue 9

- Abdominal ectopic pregnancy

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5499-415X Louise Dunphy ,

- Stephanie Boyle ,

- Nadia Cassim and

- Ajay Swaminathan

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology , Leighton Hospital , Crewe , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Louise Dunphy; Louise.Dunphy{at}doctors.org.uk

An ectopic pregnancy (EP) accounts for 1–2% of all pregnancies, of which 90% implant in the fallopian tube. An abdominal ectopic pregnancy (AEP) is defined as an ectopic pregnancy occurring when the gestational sac is implanted in the peritoneal cavity outside the uterine cavity or the fallopian tube. Implantation sites may include the omentum, peritoneum of the pelvic and abdominal cavity, the uterine surface and abdominal organs such as the spleen, intestine, liver and blood vessels. Primary abdominal pregnancy results from fertilisation of the ovum in the abdominal cavity and secondary occurs from an aborted or ruptured tubal pregnancy. It represents a very rare form of an EP, occurring in <1% of cases. At early gestations, it can be challenging to render the diagnosis, and it can be misdiagnosed as a tubal ectopic pregnancy. An AEP diagnosed >20 weeks’ gestation, caused by the implantation of an abnormal placenta, is an important cause of maternal–fetal mortality due to the high risk of a major obstetric haemorrhage and coagulopathy following partial or total placental separation. Management options include surgical therapy (laparoscopy±laparotomy), medical therapy with intramuscular or intralesional methotrexate and/or intracardiac potassium chloride or a combination of medical and surgical management. The authors present the case of a multiparous woman in her early 30s presenting with heavy vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain at 8 weeks’ gestation. Her beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (bHCG) was 5760 IU/L (range: 0–5), consistent with a viable pregnancy. Her transvaginal ultrasound scan suggested an ectopic pregnancy. Laparoscopy confirmed an AEP involving the pelvic lateral sidewall. Her postoperative 48-hour bHCG was 374 IU/L. Due to the rarity of this presentation, a high index of clinical suspicion correlated with the woman’s symptoms; bHCG and ultrasound scan is required to establish the diagnosis to prevent morbidity and mortality.

- Obstetrics and gynaecology

- Emergency medicine

https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2022-252960

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Abdominal pregnancies have been defined as serosal pregnancies occurring within the peritoneal cavity but excluding those pregnancies that are tubal, ovarian, intraligamentous or the result of a secondary implantation of primary tubal implantation. 1 The majority of abdominal ectopic pregnancies (AEPs) implant in the pelvis. An AEP is the rarest and the most serious type of extrauterine pregnancy. The pouch of Douglas (POD) is the most common location of an AEP followed by the mesosalpinx and omentum. In contrast to tubal ectopic pregnancies (EPs), AEPs may go undetected until an advanced gestational age. The absence of consistent clinical features makes the diagnosis difficult to establish. In 1944, Studdiford 1 defined the criteria used to diagnose a primary abdominal pregnancy. There are multiple risk factors that predispose patients to an EP, including a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, smoking, fallopian tube surgery, previous EP, endometriosis and assisted reproduction techniques. However, only 50% of women with an AEP have any associated risk factors. 2 An AEP can reach full-term gestation, with a viable fetus and subsequent perinatal survival, however, these are rare cases. 3 Surgery is the preferred procedure for an AEP, and the best option is to remove the entire sac including the fetus, membranes and the placenta.

Case presentation

A multiparous woman in her early 30s presented to the Emergency Gynaecology Clinic at 8 weeks’ gestation based on her last menstrual period with heavy vaginal bleeding and severe abdominal pain. She reported a 2-week history of mild vaginal bleeding and a 48-hour history of heavy bleeding with clots. It was a spontaneous conception. She had stopping taking her contraceptive pill 3 months previously. She described early pregnancy symptoms such as nausea and vomiting. Her medical history included asthma and ulcerative colitis. Her obstetrics history included two normal vaginal deliveries at term and a miscarriage at 6 weeks’ gestation. Her gynaecological history included a diagnosis of endometriosis. Her medications included salbutamol inhaler 100 mcg four times per day and sertraline 50 mg at night. She had a regular 28-day menstrual cycle. Her cervical smear was up to date. She did not have a Mirena intrauterine device in situ. Her observations were stable (Sp0 2 98% on air, respiratory rate of 14, BP 118/75 mm Hg, heart rate 79 beats per minute and temperature of 36.2°C). Physical examination confirmed generalised abdominal tenderness with guarding in the right iliac fossa. Speculum and bimanual palpation confirmed heavy vaginal bleeding. The cervical os was closed. Adnexal fullness was palpable on the right.

Investigations

Her haemoglobin on admission was 144 g/L (range: 115–165 g/L). Her beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (bHCG) was 5760 IU/L (range: 0–5), consistent with a viable pregnancy. A transvaginal ultrasound scan (TV USS) showed an endometrial thickness of 5.6 mm. Both ovaries appeared normal. Towards the midline of the pelvis, a mass was seen measuring 42×38 mm. The mass contained a cyst that appeared to contain an echogenic focus within, measuring 16 mm in diameter ( figure 1 ). The ultrasound findings raised the suspicion of a fetal pole. No fetal cardiac pulsations were seen. The mass appeared to be separate from the ovaries. The appearance raised the suspicion of an EP. There was no obvious free fluid seen in the pelvis. Her repeat bHCG at 48 hours was 4427 IU/L and her repeat TV USS showed a crown-rump length of 16.5 mm (suggesting a gestation of 8+1 weeks) ( figure 2 ). There was no free fluid. Both ovaries were normal. An EP was observed on the right side, measuring 38×27 mm. Her 96-hour bHCG was 3481 IU/L ( table 1 ).

- View inline

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Transvaginal ultrasound scan showing a lesion measuring 42×38 mm towards the midline of the pelvis. The lesion contained a cyst that appeared to contain an echogenic focus within, measuring 16 mm in diameter.

Repeat transvaginal ultrasound scan showing a crown-rump length (CRL) of 16.5 mm, suggesting a gestation of 8+1 weeks.

Differential diagnosis

The clinical symptoms correlated with her sonographic findings and her bHCG suggested an EP. Due to her abdominal pain and raised bHCG she was consented for a diagnostic laparoscopy.

A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. An indwelling urinary catheter was inserted. The cervix appeared normal. An infra-umbilical incision was performed and the Veress needle inserted. Intraperitoneal entry was confirmed with Palmers, hanging drop and pressure tests. The uterus appeared of normal size and was mobile. The fallopian tubes were normal. A mass extending from the POD and right pelvic sidewall in close proximity to the ovary was observed. It measured 4×3 cm in diameter ( figures 3 and 4 ). The upper abdomen and the liver appeared normal. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis was observed. The ectopic pregnancy was separated from the POD and the pelvic lateral sidewall. The ureter was noted. Bipolar diathermy achieved haemostasis. A pelvic drain was inserted. The estimated blood loss was 1.5 L.

A mass extending from the pouch of Douglas and right pelvic sidewall in close proximity to the ovary was observed. It measured 4×3 cm in diameter.

A mass was observed extending from the right pelvic sidewall.

Outcome and follow-up

She remained haemodynamically stable. Her haemoglobin 24 hours postoperatively was 134 g/L. Her drain was removed as it contained <50 mL of serosanguineous fluid. Her bHCG 48 hours later was 374 IU/L. Serial monitoring of her bHCG was scheduled until it was negative. Follow-up was scheduled in the Gynaecology Clinic and histology confirmed an EP.

An AEP was first reported in 1708 as an autopsy finding. 4 Due to its rarity, only case reports or small case series exist in the literature. It has an estimated incidence of 1:10 000–25 000 live births. 1 An abdominal pregnancy is the only type of EP that can advance beyond 20 weeks of gestational age. In 1942, Studdiford 1 established three criteria for the diagnosis of a primary abdominal pregnancy ( Box 1 ). Watrowski et al recently expanded the classic Studdiford criteria, following a case of an omental pregnancy invading the peritoneum of the POD. 5 6 Since 1952, <50 cases of hepatic pregnancy have been described in the literature, with the most frequent site of implantation being the inferior surface of the right lobe. 7 An AEP can be classified as early or late. An early AEP is one that presents at or before 20 weeks’ gestation and a late AEP presents after 20 weeks’ gestation. An AEP can also be further classified as primary or secondary. Primary abdominal pregnancy occurs when the fertilised ovum implants directly into the peritoneal cavity; it is the less common type. In 1968, Friedrich and Rankin 8 proposed that to be a true primary AEP, the pregnancy should be <12 weeks’ gestation and the trophoblastic attachments should be related solely to the peritoneal surface. Secondary abdominal pregnancy occurs when the fertilised ovum first implants in the fallopian tube or uterus and then due to fimbrial abortion or rupture of the fallopian tube or uterus, the fetus subsequently develops in the mother’s abdominal cavity. Classification of an AEP although academically interesting is of limited clinical value. Risk factors include fallopian tube injury, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, multiparity and assisted reproductive techniques. Thirty-seven per cent of cases have a history of a tubal EP and 61% have a fallopian tube factor. 3 It has even been reported after bilateral salpingectomy in a patient who underwent in vitro fertilisation (IVF). 9 Studies have also suggested that the use of cocaine may be a risk factor for an AEP. 10

The Studdiford criteria for the diagnosis of a primary peritoneal pregnancy (L Dunphy)

The presence of normal tubes and ovaries.

No evidence of a uteroperitoneal fistula.

A pregnancy exclusively related to the peritoneal surface.

No evidence of secondary implantation following initial primary tubal nidation.

Several theories on the pathophysiology of an AEP have been postulated but the aetiology remains to be fully elucidated. Berghella and Wolf 11 refuted the diagnosis of primary implantation. Paternoster and Santarossa 12 suggested that delayed ovulation occurring close to menses may reverse the fertilised ovum in its tubal course by retrograde menstrual flow. Cavanagh 13 postulated that fertilisation may occur in the posterior cul-de-sac where sperm is known to accumulate and that an ovum could lay there due to dependent flow of peritoneal fluid. Dmowski et al 9 and Iwama et al 14 hypothesised that a retroperitoneal AEP may occur due to migration of the embryo along lymphatic channels. Reports have also described an AEP after a hysterectomy. It has been suggested that IVF may predispose to an AEP via uterine perforation at the time of embryo transfer, migration of an oocyte into the abdominal cavity with subsequent abdominal fertilisation by spermatozoa or migration through a micro-fistulous tract through the uterine isthmus.

Early diagnosis is difficult to establish as women may present with a plethora of symptoms or be asymptomatic. There are no pathognomonic symptoms of an AEP that distinguish it from a tubal pregnancy. It may present as diffuse pain accompanied by signs of incipient pregnancy. At an advanced gestation, the woman may present with non-specific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding or decreased, absent and painful fetal movements. 15 Nausea, vomiting and an intense persistent desire to defecate may be prominent symptoms, when the pregnancy implants on bowel. A history of irregular bleeding is less frequently reported than in tubal EPs. Fetal movements may also be reported high in the upper abdomen or there may be absent fetal movements. The fetus may be easily palpable and the presentation may be transverse. Speculum and bimanual examination may show a closed and effaced cervix. Oxytocin may also fail to stimulate the gestational mass. The patient may also present with haemodynamic compromise and shock due to rupture of the AEP.

A suboptimal rise in serum bHCG is a useful marker, but it is not sufficient to establish the diagnosis. However, laboratory investigations may reveal excessively elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels. TV USS is the main imaging modality. However, it only has a sensitivity of 50%. Sonographic features include an empty uterus. The classic ultrasound finding is the absence of myometrial tissue between the maternal bladder and the pregnancy. 16 Other sonographic features suggestive of the diagnosis may include poor definition of the placenta, oligohydramnios and an unusual fetal lie ( box 2 ). However, it can be challenging to differentiate it from a tubal EP at an early gestation, especially when it implants in the vicinity of the adnexa. CT and MRI can also be used for further evaluation. MRI is the gold standard for evaluating placental implantation and preoperative planning. However, it is not uncommon to diagnose an AEP for the first time at laparotomy or laparoscopy performed for a tubal EP. Chen’s review of 17 cases showed that the rate of preoperative diagnosis remained low with only 29.41% of cases diagnosed preoperatively. 17 The accuracy of diagnosis increased with an increase in gestational age and the appearance of the fetal heartbeat. The differential diagnosis includes an EP at other locations, an intrauterine pregnancy in a rudimentary horn, placental abruption or uterine rupture. A retroflexed uterus and the presence of a uterine leiomyoma (fibroid) can also make the diagnosis difficult to render. A false-negative diagnosis as an intrauterine pregnancy can occur. A false-positive diagnosis with cervical, intramural, isolated uterine horn and a bicornuate pregnancy can also occur.

. Sonographic features of an abdominal pregnancy

An absence of myometrial tissue between the maternal bladder and the pregnancy, abdominal wall and pregnancy.

An empty uterus.

Poor definition of the placenta.

Oligohydramnios.

Unusual fetal lie.

There is no established guidance available for the diagnosis and management of an AEP. An AEP can reach full-term gestation, with a viable fetus and subsequent perinatal survival; however, these are exceptional cases. 18 Between the years 2008 and 2013, 38 cases of advanced abdominal pregnancy resulting in a live birth were reported. 19 Twenty-one per cent of neonates had a birth defect such as limb defects, craniofacial and joint abnormalities, for example, talipes equinovarus, as well as central nervous system malformations. 20 Due to abnormal placental implantation, cases of advanced AEP carry multiple risks such as haemorrhage, infection, disseminated intravascular coagulation, fistula formation and pre-eclampsia. 21 Expectant management to gain fetal maturity has been attempted and has been successful in a few cases. 3 The conservative approach by Marcellin et al 22 carried a pregnancy until 32 weeks uneventfully. Similarly, Beddock et al 23 described a viable fetus at 37 weeks’ gestation without maternal or fetal complications. There are no strong clinical predictors for successful medical therapy and the decision for medical therapy must be individualised based on the distinctive characteristics of each case. Medical management includes methotrexate (local or systemic), local instillation of potassium chloride, hyperosmolar glucose, prostaglandins, danazol, etoposide and mifepristone. 24 Medical management is commonly used where potentially life-threatening bleeding is anticipated, such as an AEP involving the liver or the spleen. Primary methotrexate therapy has a high failure rate due to the advanced gestational age at which an AEP is diagnosed. Postoperatively, histology showing evidence of trophoblast proliferation with neovascularisation involving the organ or structure the pregnancy was attached to confirms the diagnosis of an EAP. 23

Angiographic arterial embolisation can be used as first-line treatment of an AEP with the aim of avoiding surgery or by reducing the vascularity of the placenta making surgery safer. 25 Selective embolisation of vessels supplying the placenta should be considered to control the haemorrhage postoperatively from the retained placenta. Historically, an AEP was managed surgically. However, in 1993, Balmaceda et al 26 reported laparoscopic management of an AEP at 7 weeks’ gestation. Abossolo et al 27 also described successful management of a first trimester AEP with significant intraoperative haemorrhage laparoscopically. 27 Laparoscopy can be performed at early gestations as removal of the small and less vascular placental tissue is easier. At late gestations, surgery is the main treatment. The entire sac including the fetus, membranes and the placenta should be removed. 28 However, termination of pregnancy should also be offered due to the adverse maternal and fetal sequelae. The fetus can be delivered easily; the key issue is how to manage the placenta. Bleeding from the placental site can be a life-threatening complication during laparotomy as an AEP lacks the haemostatic mechanisms exerted by myometrial contractions, therefore, it fails to constrict the placental vasculature. Indeed, a complicated AEP with the placenta feeding off the sacral plexus has also been described. 29 There are two options. The placenta can be removed after ligating the placental blood supply. A good separation technique and adequate vascular management should be performed. The second option is to leave the placenta in situ after ligating the umbilical cord. 30 However, this option is associated with sepsis, abscess formation, delayed haemorrhage due to retained placental remnants, adhesions, coagulopathy, ongoing pre-eclampsia and failure of lactogenesis. When the placenta remains in situ, two methods of follow-up are available. The first is the use of methotrexate to accelerate tissue absorption. The role of methotrexate to hasten placental resorption is discouraged by most authors due to the risk of infection. The second method is expectant management, which consists of monitoring the bHCG levels and performing an ultrasound scan. Chen et al 17 waited for self-absorption in cases where the placenta was left in situ and followed up the patients for a maximum period of 26 months. It has been suggested that there is a similarity with the intrauterine placenta accreta spectrum cases and an AEP, especially in the management of the placenta. 17 In Honduras in 1956, a case of an AEP with a dead fetus that developed into a lithopedion, derived from the Greek words lithos (stone) and paedion (child), a term used to describe an AEP in which the fetus dies but cannot be reabsorbed by the mother’s body was described. 31 Ultrasonographic-guided fetocide of a 14.5 weeks’ gestation to prevent further development and initiate the process of natural resorption has been reported. 32

Abdominal pregnancy has a maternal mortality rate between 0.5% and 18%, which is >7 times higher compared with that of other EPs. 33 34 This is due to the risk of massive haemorrhage from a partially or totally separated placenta at any stage of pregnancy. Its perinatal mortality rate is between 40% and 95%. 35 A high index of clinical suspicion and a multi-disciplinary approach is required to prevent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

Learning points

Abdominal ectopic pregnancies (AEPs) present with a plethora of non-specific symptoms and may go undetected until an advanced gestational age when the patient presents with a history of recurrent abdominal pain, the presence of fetal movements high in the upper abdomen or absence of fetal movements. Clinical manifestations may also include soreness during fetal movements, easily palpable parts of the fetal body and a transverse presentation.

There are no specific criteria to diagnose an AEP and it may be missed on ultrasound. However, a classic sign on ultrasound scan is the absence of echo signs of myometrium between the mother’s bladder and the fetus. Additional signs may include poor visualisation of the placenta, oligohydramnios and a transverse presentation. MRI is the gold standard for evaluating placental attachment and vascular connections.

The mainstay of treatment of advanced AEP is surgery, but the optimal approach has not been determined. Management of the placenta remains controversial. Maternal morbidity and mortality is high as AEPs typically implant on highly vascularised surfaces. Separation of the placenta can occur at any gestation and may lead to life-threatening maternal haemorrhage. Maternal and fetal outcomes are determined by haemodynamic status and gestational age at presentation.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

- Studdiford WE

- Kopelman ZA ,

- Keyser EA ,

- Watrowski R ,

- Cao Y , et al

- Friedrich EG ,

- Dmowski WP ,

- Ding J , et al

- Smith DM , et al

- Berghella V ,

- Paternoster DM ,

- Santarossa C

- Tsutsumi S ,

- Igarashi H , et al

- Mansuria S ,

- Guido RS , et al

- Li C , et al

- Mascarenhas L ,

- Aragon-Charry J ,

- Santos-Bolívar J ,

- Torres-Cepeda D , et al

- Masukume G ,

- Sengurayi E ,

- Muchara A , et al

- Marcellin L ,

- Lamau M-C , et al

- Beddock R ,

- Naepels P ,

- Gondry C , et al

- Raughley MJ ,

- Frishman GN

- Balmaceda JP ,

- Bernardini L ,

- Asch RH , et al

- Abossolo T ,

- Sommer JC ,

- Dancoisne P , et al

- Chueh H-Y , et al

- Feldman J ,

- Madan M , et al

Contributors The following authors were responsible for drafting of the text, sourcing and editing of clinical images, investigation results, drawing original diagrams and algorithms, and critical revision for important intellectual content: LD: wrote the case report; SB: literature review; NC: literature review; AS: literature review. LD, SB, NC and AS gave final approval of the manuscript.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 12 February 2021

Determinants of ectopic pregnancy among pregnant women attending referral hospitals in southwestern part of Oromia regional state, Southwest Ethiopia: a multi-center case control study

- Urge Gerema ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5286-5100 1 ,

- Tilahun Alemayehu 1 ,

- Getachew Chane 1 ,

- Diliab Desta 1 &

- Amenu Diriba 2

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 21 , Article number: 130 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

8930 Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

Ectopic pregnancy is an abnormal condition in which implantation of the blastocyst occurs outside the endometrium of the uterus. It is gynecological important, particularly in the developing world, because of associated with enormous rate of high morbidity, during the first trimester of pregnancy. A better understanding of its risk factors can help to prevent its prevalence. However, the determinants of ectopic pregnancy are not well understood and few researches conducted in our country were based on secondary data covering small scale area. This study aimed to identify determinants of ectopic pregnancy among pregnant women attending referral hospitals in Southwestern part of Oromia regional state, Southwest Ethiopia.

Hospital-based case control study was employed from June 1 to September 30, 2019. The study was conducted in five referral hospitals in Southwestern part of Oromia regional state. Final sample size includes 59 cases and 118 controls. Data were entered by using Epidata version 3.1 and analyzed using SPSS version 23. Descriptive statistics were used to explore the data. All explanatory variables with p -value of < 0.25 in bi-variable analysis, then entered into multivariable logistic regression. Associated factors were identified at 95% confidence interval ( p < 0.05).

Out of 177 (59 cases and 118 controls) participants, 174 (58 cases and 116 controls) were participating in the study. Prior two or more induced abortions [AOR = 3.95:95% CI: 1.22–13.05], previous history of caesarean section [AOR = 3.4:95% CI: 1.11–10.94], marital status (being single) [AOR = 4.04:95%CI: 1.23–13.21], reporting prior recurrent sexual transmitted infection [AOR = 2.25:95%CI: 1.00–5.51], prior history of tubal surgery [AOR = 3.32:95%CI: 1.09–10.13], were more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy with their respective AOR with 95%CI.

It was found that having a history of more than two induced abortions during previous pregnancies, marital status (single), recurrent sexual transmitted infection, prior history of tubal surgery and experiencing prior caesarean section were found to be determinants of ectopic pregnancy. Hospitals should give emphasis on prevention and early detection of risks of ectopic pregnancy and create awareness in order to reduce the burden of ectopic pregnancy.

Peer Review reports

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is an abnormal condition in which implantation of the blastocyst occurs outside the endometrium of the uterus. These abnormal sites of implantation in decreasing order of frequency include uterine tube (tubal pregnancy), abdominal cavity or on the mesentery (abdominal pregnancy), and in the ovaries (ovarian pregnancy) [ 1 , 2 ]. Blastocysts that do not implant in the uterine wall are generally unable to develop normally because; the space is incapable for developing blastocyst. Ectopic pregnancy can cause ruptures of fallopian tube, cervix and abdomen on which they are implanted. Rupture of ectopic pregnancy result in severe bleeding, many organ damage, and maternal mortality [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. It is obstetrical and gynecological important, especially in the developing world, because of the high maternal morbidity and mortality associated with it and the enormous threat to life particularly in the first trimester pregnancy [ 2 ]. It occurs in approximately 1–2% of pregnancies [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. It is one of the top leading causes of maternal mortality in the first trimester and accounts for 10–15% of all maternal deaths [ 7 ]. Ectopic pregnancy is the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide [ 8 ].

In western world, the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is approximately 2% in the general population, but as high as 20% in patients who have undergo tubal surgery, previous ectopic pregnancy [ 8 ]. The prevalence of ectopic pregnancy has an increasing trend during the last three decades throughout the world especially in developing countries where early diagnosis is low [ 3 ].

The causes of ectopic pregnancy are not well understood. However, multiple risk factors have been associated with ectopic pregnancy, although some patients may not have any risk factor to developed ectopic pregnancy. The main function of the oviduct is to provide the optimal environment for the transport and maturation of ovum and sperm for the establishment of pregnancy. Most data suggest that ectopic pregnancy causes from both abnormal zygote transport and change in the tubal environment, which enables abnormal implantation to occur [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

In spite of different research done on the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy, however, the determinants of ectopic pregnancy are not well understood and few researches published in our country were based on secondary data covering small scale area and the study area has different characteristics cultural, religious, socio-demographic characteristics, sexual behavior, beliefs, contraception usage and practice from other area. The study was aimed to identify risk factors of ectopic pregnancy among pregnant women attending referral hospitals in Southwestern part of Oromia Regional state, Southwest Ethiopia.

This study result would worth to detect the potential risk factors of ectopic pregnancy in the study setup which would have further advantages to minimize morbidity and mortality of patients due to ectopic pregnancy. With regard to the preventable factors associated with ectopic pregnancy in the current population, this study is an important piece of work that could serve as an important source of information to design prevention strategies or to conduct further investigations.

Study setting, design and population

A multi-centered hospital-based case control study was conducted among pregnant women attending referral hospitals in Southwestern parts of Oromia regional state, Southwest Ethiopia from June 1 to September 30, 2019. All hospitals are teaching and referral hospital that gave general and specialized clinical services including ANC, family planning, delivery service & treatment obstetric complications are some of the services provided in gynecologic and obstetric ward. These services have been delivered by senior midwives, gynecologists/obstetricians. All pregnant women attending gynecology and obstetrics department of JMC (Jimma Medical Center), WURH (Wollega University Referral Hospital), NRH (Nekemte Referral Hospital), AURH (Ambo Referral Hospital) and MKRH (Mettu Karl Referral Hospital) during the four-month study period were source population.

Study population: For cases all pregnant women who had been confirmed by ultrasound and HCG to have EP in the inpatient department of gynecology and obstetrics of each hospital were recruited. For controls: Controls were sampled pregnant women confirmed by ultrasound and HCG to have intra uterine pregnancy at the prenatal clinic in department of gynecology and obstetrics of each hospital.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for cases.

admitted women who had been confirmed by ultrasound and HCG to have EP in the inpatient department of gynecology and obstetrics of each hospital. For controls: Controls were sampled pregnant women confirmed by ultrasound and HCG to have intra uterine pregnancy at the prenatal clinic in department of gynecology and obstetrics of each hospital.

Exclusion criteria for both cases and controls

Women with serious medical conditions and couldn’t give consent were excluded from the study.

Case definition

Case pregnant women diagnosed by hCG and ultrasound to have ectopic pregnancy confirmed by Obstetrician/gynecologist [ 12 ].

Pregnant women diagnosed by hCG and ultrasound to have intrauterine pregnancy confirmed by Obstetrician/gynecologist [ 12 ].

Sample size and sampling procedure

The required sample size was determined by using Epi-info version 7 statistical software for unmatched case-control study design. Results from similar studies were used to approximate the sample size in different potential risk factors of ectopic pregnancy. In a study report from India prior tubal surgery was a significant risk factor for ectopic pregnancy [ 13 ]. A case control study in western Ethiopia at Nekemte hospital marital status was a significant risk factor for ectopic pregnancy [ 14 ]. Similarly, case control study done in Turkey Ankara previous history of ectopic pregnancy was a significant risk factor for ectopic pregnancy [ 15 ]. Using these reports as starting point, similar assumptions P1: proportion among cases and p 2: proportion of among controls AOR: Adjusted odds ratio at 95% ( Zα/2 = 1.96) level of confidence, Power of study = 80% Ratio of cases to controls = 1:2 (Table 1 ).

From the above three significant risk factors of ectopic pregnancy, previous history of ectopic pregnancy gives the large sample size which gives total of 177 study participants (59 cases and 118 controls). In the selected five referral hospitals the number of pregnant. Women registered during the 2018 G. C HMIS report over 4 months at JMC, WURH, NRH, AURH and MKRH were 1707, 1085, 679, 1489 and 1219 respectively.

The calculated sample size was proportionally allocated based on the estimated number of pregnant women in selected referral hospitals. Therefore (16 cases and 32 controls) from JMC, (10 cases and 20 controls) from WURH, (7 cases and 14 controls) from NRH, (14 cases and 28 controls) from AURH and (12 cases and 28 controls) from MKRH. Then, the study participant was selected using consecutive sampling technique.

Data collection tools and procedures

The data were collected by face to face interview using semi structured questionnaire addressing socio-demographic and obstetric, gynecologic, behavioral, surgical history and contraceptive characteristics of study participants which was developed after reviewing different literatures. Fifteen trained data collectors and five supervisors were involved in the process.

Data quality control

The urine sample collection was done through standardized, and sterile technique by professional laboratory technologists, ultrasound was calibrated before the procedure. The diagnosis of pregnancy was confirmed by Trans abdominal ultrasonography combined to the hCG.

Data quality was ensured during data collection, coding, entry and analysis. During data collection adequate training and follow up was provided to data collectors and supervisors. Incomplete checklists were returned back to the data collector for completion. Codes were given to the questionnaires and during the data collection so that any identified errors was traced back using the codes.

Data processing and analysis

Collected data were rechecked for completeness, consistency and coded before data entry. Data were entered using Epi data version 3.1 and data from five hospitals were merged together, and then exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23 for analysis. Descriptive analysis was conducted to explore the data and present some variables. Bi-variable binary logistic regression analysis was executed to select candidate variable for multivariable binary logistic regression to identify the predictors. Variables with p -value of less than 0.25 were selected for multivariable logistic regression. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to describe the association between ectopic pregnancy and potential risk factors. Variables with a p -value < 0.05 in multi-variable analysis was considered as a significant risk factor for ectopic pregnancy.

Socio-demographic characteristics

In this prospective case control study conducted over four-months from June 1 to September 30, 2019 at five government referral hospitals found in Southwestern part Oromia, Ethiopia. A total of 174 pregnant women; 58 Cases (EP) and 116 Controls (IUP) were participated. The mean age was 26 (± 5.54), 26 (± 4.87 years for cases and controls respectively.

Almost two-third (63.8%) of cases and 79 (68.1%) of controls were aged between 21 and 30 years. Eighteen (31%) cases and 39(33%) of controls were orthodox in religion and 37(63.8%) of cases and 79 (68.1%) of controls were Oromo by their ethnicity and 37 (63.8%) cases and 95(81.9%) of controls were married. About 18 (31%) cases and 46 (39.7%) controls were house wives in occupation (Table 2 ).

Behavioral characteristics

Only one case (1.7%) and two controls (1.7%) had occasional history of cigarette smoking and only 18(31.1%) cases and 34(29.3%) controls history of occasionally alcohol consumption before current pregnancy (Table 3 ).

Obstetrics and surgical history of participants

As indicated in the Table 4 , three of the cases (5.1%) and another three women in the control group (2.6%) had prior history of ectopic pregnancy. Seven women in each of the study groups (12.0% of the cases and 6.0% of the controls) had more than two prior history of spontaneous abortion. Similarly, 8 (13.8%) cases and 6 (5.1%) controls reported two or more prior history of induced abortions. This study shows that 10(17.2%) of cases and 6(5.1%) controls had caesarean section before current pregnancy. Eleven (18.1%) of cases and 6(5.2%) controls had at least one tubal pregnancy before current pregnancy for any reason (Table 4 ).

Gynecologic and contraceptive history of participants

About 36.2% (21/58) of the cases and 16 (13.7%) controls had prior history of a recurrent.

STD/STI. Majority 42 (72.4%) of the cases and 92 (79.3%) controls had prior history of oral contraceptive use. Only 6 (10.3%) cases and 15(12.9%) controls had history of IUCD use.

Twenty (34.4%) cases and 18 (10.8%) controls reported practice of emergency contraceptives pills use before the current conception (Table 5 ).

Factors associated with ectopic pregnancy

Findings from bi-variable logistic regression analysis showed that marital status, prior history of induced abortions, prior history of spontaneous abortions, prior history of tubal surgery, prior history of caesarean section, prior history of tubal ligation and history of recurrent STD/STI had associated with ectopic pregnancy with p-value of < 0.25, However, in.

multivariable regression analysis, history of two or more induced abortions [AOR = 3.42:95%CI: 1.06–11.05], prior history of caesarean section [AOR = 3.48:95% CI: 1.14–10.13], prior history of tubal surgery [AOR = 3.32:95%CI: 1.09–10.13], marital status (being single) [AOR = 3.23:95%CI:1.02–10.22], prior recurrent STD/STI [AOR = 3.08:95%CI: 1.38–6.88} remained statistically significant risk factor for ectopic pregnancy (Table 6 ).

This was a multi-centered hospital based case control study which, was aimed to identify determinants of ectopic pregnancy among pregnant women attending referral hospitals in Southwestern parts of Oromia regional state, Southwest Ethiopia. Being single were independent predictors of ectopic pregnancy. A similar association was reported in studies done in west Ethiopia Nekemte and Uganda [ 14 , 16 ]. The association between being single and ectopic pregnancy infection could be explained by the fact that single women engaged in multiple sexual partners following successive infection, ascending infection result in adhesions, impede the morula retention of movement causing implantation in the tube and other site.

Having more than two times history of induced abortion found was statistically significant relation with ectopic pregnancy. This finding was supported by a study done in; India, Tigray, Ethiopia and Nigeria [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. The association might be explained by most abortions are illegal different countries and usually performed in poor aseptic conditions. Thus, increasing post-abortion sepsis risk and subsequent PID.

Women who had a prior history of recurrent STI were significantly associated with ectopic pregnancy. This finding was similar to studies done in Ethiopia, Ghana [ 20 ]. The association between STD/STI and ectopic pregnancy might be successive infection, ascending infection result in salphingitis leads to tubal dysfunction, decrease cilia density; ciliary beat this result in retention of morula in the fallopian tube and implantation of blastocyst in the fallopian tube and other site.

Women having at least one caesarean section for previous pregnancy were independently associated with ectopic pregnancy. This study supported by a study done in Turkey [ 15 ]. The underlying mechanism of association between previous caesarean section and occurrence of ectopic pregnancy is might be due to increased pelvic infection and adhesion after caesarean section which disturbs the micro environment of the tube and implantation of blastocyst in the tube.

In the present study, women who had a prior history of tubal surgery were statistically significant with ectopic pregnancy. This study is supported by study done in Egypt and Uganda [ 16 ]. The association might be explained by the scar on the Fallopian tube may interfere with the ovum transport and implantation of blastocyst in the Fallopian tube.

I did not find any association between appendectomy, prior use of IUCD, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking and previous history of ectopic pregnancy, previous tubal surgery with present study, probably the number of the studied participants was too small.

Limitations and strengths of the study

Due to a small number of cases obtained from each hospital, this study did not compare among the five hospitals with regard to risk factors of EP and study assesses history of exposure retrospectively, it may be prone to recall and selection bias by nature during the data collection time. The study has some strengths this study used the primary data from the participants. Further, the study was multi-centered hospital based case control.

Conclusions

It was found that having a history of more than two induced abortions during previous pregnancy, marital status (single), experiencing at least one caesarean section for previous pregnancies, prior history of STD/STI and using emergency contraceptive pills during the cycle of conception were found important determinants of ectopic pregnancy in the study population. Women with history of previous induced abortion and previous caesarean section STD/STI should be followed up carefully, even in the absence of symptoms should always be counseled about the possibility of ectopic pregnancy and the associated risks.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Adjusted odd ratio

Ambo University Referral Hospital

Crude odd ratio

- Ectopic pregnancy

chorionic gonadotropin

Health Management Information system

Intra uterine pregnancy

Jimma Medical Center

Mettu Karl Referral Hospital

Nekemte Referral Hospital

Sexual transmitted diseases

Sexual transmitted infection

Bhuria V, Nanda S, Chauhan M, Malhotra V. A retrospective analysis of ectopic pregnancy at a tertiary care Centre: one year study. Int J Reproduct Contracept Obstetr Gynecol. 2016;5:2224–7.

Gaym A. Maternal mortality studies in Ethiopia--magnitude, causes and trends. Ethiop Med J. 2009;47(2):95–108.

PubMed Google Scholar

Yeasmin MS, Uddin MJ, Hasan E. A clinical study of ectopic pregnancies in a tertiary care hospital of Chittagong, Bangladesh. Chattagram Maa-O-Shishu Hosp Med Coll J. 2014;13(3):1–4.

Article Google Scholar

Gharoro EP, Igbafe AA. Ectopic pregnancy revisited in Benin City, Nigeria: analysis of 152 cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(12):1139–43.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Basnet R, Pradhan N, Bharati L, Bhattarai N, Bb B, Sharma B. To determine the risk factors associated with ectopic pregnancy. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;8(2):93–7.

Google Scholar

Porricelli JD, Boyd JH. Analytical Techniques for Predicting Grounded Ship Response. Engineering computer opt economics inc Annapolis md; 1983.

Dabota BY. Management and outcome of ectopic pregnancy in developing countries. Ectopic Pregnancy. 2011;109:10–8.

Panchal D, Vaishnav G, Solanki K. Study of management in patient with ectopic pregnancy. Infection. 2011;33:55.

Shaw JL, Dey SK, Critchley HO, Horne AW. Current knowledge of the etiology of human tubal ectopic pregnancy. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):432–44.

Jacob L, Kalder M, Kostev K. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in Germany: a retrospective study of 100,197 patients. GMS German Med Sci. 2017;15:33–4.

John CO, Alegbleye JO. Ectopic pregnancy experience in a tertiary health facility in South-South Nigeria. Nigerian Health J. 2016;16(1):2–5.

Schoenwolf, G.C., Bleyl, S.B., Brauer, P.R., Francis-West, P.H. & Philippa H. (2015). Larsen's human embryology (5th ed.). New York; Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Bhandari G, Yadav KK, Shah R. Ectopic pregnancy and its risk factors: a case control study in Nepalese women. J BP Koirala Inst Health Sci. 2018;1(2):30–4.

Kebede Y, Dessie G. Determinants of ectopic pregnancy among pregnant women who were managed in Nekemte referral hospital, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. J Preg Child Health. 2018;5(370):2.

Karaer A, Avsar FA, Batioglu S. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a case-control study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46(6):521–7.

Dp M, Lugobe H, Ssemujju A. Factors associated with ectopic pregnancy at Mbarara University teaching Hospital in South Western Uganda. Reprod Med. 2018;2(4):2–7.

Kassebaum NJ, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Dandona L, Gething PW, Hay SI, Kinfu Y, Larson HJ, Liang X, Lim SS, Lopez AD. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–812.

Abebe D, Tukue D, Aregay A, Gebremariam L. Magnitude and associated factors with ectopic pregnancy treated in Adigrt hospital, Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2017;7(1):30–39.

Lawani OL, Anozie OB, Ezeonu PO. Ectopic pregnancy: a life-threatening gynecological emergency. Int J Women's Health. 2013;5:515.

Chow JM, Yonekura ML, Richwald GA, Greenland S, Sweet RL, Schachter J. The association between chlamydia trachomatis and ectopic pregnancy: a matched-pair, case-control study. JAMA. 1990;263(23):3164–7.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jimma University for allowing me to conduct this study. Also we would like to thanks the study participants, data collectors and supervisors.

There is no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Biomedical sciences (Anatomy course unit), Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Urge Gerema, Tilahun Alemayehu, Getachew Chane & Diliab Desta

Department of gynecology and obstetrics, Wellega University, Wellega, Ethiopia

Amenu Diriba

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

UG involved in conceiving the idea, study design, data analysis and interpretation, writing the manuscript and managing the overall progress of the study. TA, G CH, DD and AD involved in study design, data analysis and in revising the manuscript. The final manuscript was read and approved by all the authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Urge Gerema .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval or clearance letter RPSCMF/0132/19 was obtained from institutional review board (IRB) of Institute of Health, Jimma University. Permission letter was written to respective hospitals administration office, and the study was commencing after receiving formal permission from them. The Institutional review board approved the verbal consent. Due to low literacy level informed verbal consent was obtained from each respondent after they had been taken through the respondent information sheet. Data collectors maintained confidentiality through excluding names or any other personal identifiers from data collection sheets and reports.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gerema, U., Alemayehu, T., Chane, G. et al. Determinants of ectopic pregnancy among pregnant women attending referral hospitals in southwestern part of Oromia regional state, Southwest Ethiopia: a multi-center case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21 , 130 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03618-7

Download citation

Received : 03 January 2020

Accepted : 03 February 2021

Published : 12 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03618-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Intrauterine pregnancy

- Determinants

- Southwest Ethiopia

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

ISSN: 1471-2393

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

ERIN HENDRIKS, MD, RACHEL ROSENBERG, MD, AND LINDA PRINE, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(10):599-606

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized ovum implants outside of the uterine cavity. In the United States, the estimated prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is 1% to 2%, and ruptured ectopic pregnancy accounts for 2.7% of pregnancy-related deaths. Risk factors include a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, cigarette smoking, fallopian tube surgery, previous ectopic pregnancy, and infertility. Ectopic pregnancy should be considered in any patient presenting early in pregnancy with vaginal bleeding or lower abdominal pain in whom intrauterine pregnancy has not yet been established. The definitive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy can be made with ultrasound visualization of a yolk sac and/or embryo in the adnexa. However, most ectopic pregnancies do not reach this stage. More often, patient symptoms combined with serial ultrasonography and trends in beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels are used to make the diagnosis. Pregnancy of unknown location refers to a transient state in which a pregnancy test is positive but ultrasonography shows neither intrauterine nor ectopic pregnancy. Serial beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels, serial ultrasonography, and, at times, uterine aspiration can be used to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. Treatment of diagnosed ectopic pregnancy includes medical management with intramuscular methotrexate, surgical management via salpingostomy or salpingectomy, and, in rare cases, expectant management. A patient with diagnosed ectopic pregnancy should be immediately transferred for surgery if she has peritoneal signs or hemodynamic instability, if the initial beta human chorionic gonadotropin level is high, if fetal cardiac activity is detected outside of the uterus on ultrasonography, or if there is a contraindication to medical management.

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized ovum implants outside of the uterine cavity. The prevalence of ectopic pregnancy in the United States is estimated to be 1% to 2%, but this may be an underestimate because this condition is often treated in the office setting where it is not tracked. 1 , 2 The mortality rate for ruptured ectopic pregnancy has steadily declined over the past three decades, and from 2011 to 2013 accounted for 2.7% of pregnancy-related deaths. 1 , 3 Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy are listed in Table 1 4 , 5 ; however, one-half of women with diagnosed ectopic pregnancy have no identified risk factors. 4 – 6 The overall rate of pregnancy (including ectopic) is less than 1% when a patient has an intrauterine device (IUD). However, in the rare case that a woman does become pregnant while she has an IUD, the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is as high as 53%. 7 , 8 There is no difference in ectopic pregnancy rates between copper or progestin-releasing IUDs. 9

Making the Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms.

Ectopic pregnancy should be considered in any pregnant patient with vaginal bleeding or lower abdominal pain when intrauterine pregnancy has not yet been established ( Table 2 ) . 10 Vaginal bleeding in women with ectopic pregnancy is due to the sloughing of decidual endometrium and can range from spotting to menstruation-equivalent levels. 10 This endometrial decidual reaction occurs even with ectopic implantation, and the passage of a decidual cast may mimic the passage of pregnancy tissue. Thus, a history of bleeding and passage of tissue cannot be relied on to differentiate ectopic pregnancy from early intrauterine pregnancy failure.

The nature, location, and severity of pain in ectopic pregnancy vary. It often begins as a colicky abdominal or pelvic pain that is localized to one side as the pregnancy distends the fallopian tube. The pain may become more generalized once the tube ruptures and hemoperitoneum develops. Other potential symptoms include presyncope, syncope, vomiting, diarrhea, shoulder pain, lower urinary tract symptoms, rectal pressure, or pain with defecation. 11

The physical examination can reveal signs of hemodynamic instability (e.g., hypotension, tachycardia) in women with ruptured ectopic pregnancy and hemoperitoneum. 12 Patients with unruptured ectopic pregnancy often have cervical motion or adnexal tenderness. 13 Sometimes the ectopic pregnancy itself can be palpated as a painful mass lateral to the uterus. There is no evidence that palpation during the pelvic examination leads to an increased risk of rupture. 10

BETA HUMAN CHORIONIC GONADOTROPIN

Beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) can be detected in pregnancy as early as eight days after ovulation. 14 The rate of increase in β-hCG levels, typically measured every 48 hours, can aid in distinguishing normal from abnormal early pregnancy. In a viable intrauterine pregnancy with an initial β-hCG level less than 1,500 mIU per mL (1,500 IU per L), there is a 99% chance that the β-hCG level will increase by at least 49% over 48 hours. 15 As the initial β-hCG level increases, the rate of increase over 48 hours slows, with an increase of at least 40% expected for an initial β-hCG level of 1,500 to 3,000 mIU per mL (1,500 to 3,000 IU per L) and 33% for an initial β-hCG level greater than 3,000 mIU per mL. 15 A slower-than-expected rate of increase or a decrease in β-hCG levels suggests early pregnancy loss or ectopic pregnancy. The rate of increase slows as pregnancy progresses and typically plateaus around 100,000 mIU per mL (100,000 IU per L) at 10 weeks' gestation. 16 A decrease in β-hCG of at least 21% over 48 hours suggests a likely failed intrauterine pregnancy, whereas a smaller decrease should raise concern for ectopic pregnancy. 17

The discriminatory level is the β-hCG level above which an intrauterine pregnancy is expected to be seen on transvaginal ultrasonography; it varies with the type of ultrasound machine used, the sonographer, and the number of gestations. A combination of β-hCG level greater than the discriminatory level and ultrasonography that does not show an intrauterine pregnancy should raise concern for early pregnancy loss or an ectopic pregnancy. 5 The discriminatory zone was previously defined as a β-hCG level of 1,000 to 2,000 mIU per mL (1,000 to 2,000 IU per L); however, this cutoff can miss some intrauterine pregnancies that do not become apparent until a slightly higher β-hCG level is achieved. Therefore, in a desired pregnancy, it is recommended that a discriminatory level as high as 3,500 mIU per mL (3,500 IU per L) be used to avoid misdiagnosis and interruption of a viable pregnancy, although most pregnancies will be visualized by the time the β-hCG level reaches 1,500 mIU per mL. 18 , 19

TRANSVAGINAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Intrauterine pregnancy visualized on transvaginal ultrasonography essentially rules out ectopic pregnancy except in the exceedingly rare case of heterotopic pregnancy. 5 The definitive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy can be made with ultrasonography when a yolk sac and/or embryo is seen in the adnexa; however, ultrasonography alone is rarely used to diagnose ectopic pregnancy because most do not progress to this stage. 5 More often, the patient history is combined with serial quantitative β-hCG levels, sequential ultrasonography, and, at times, uterine aspiration to arrive at a final diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.

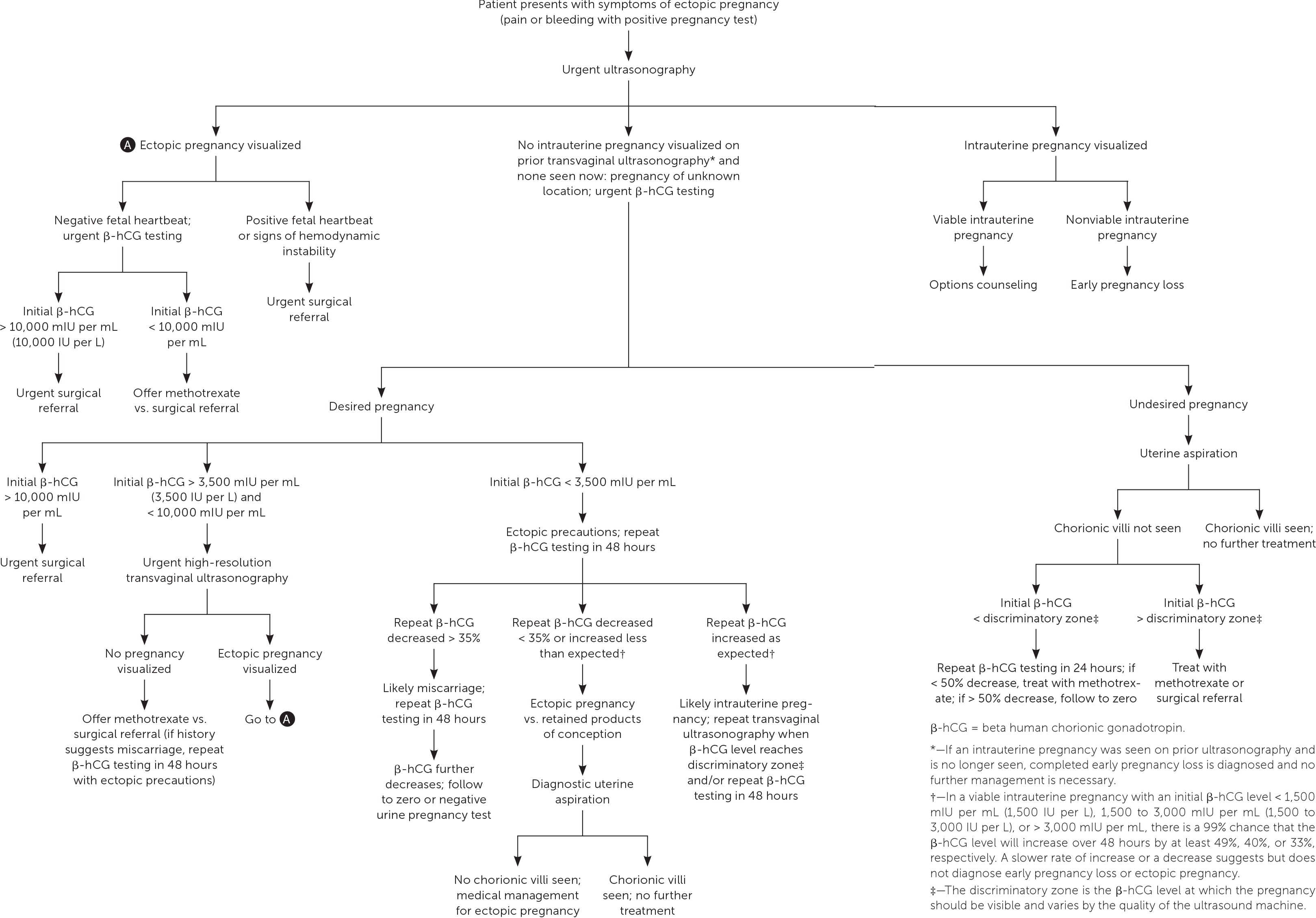

PREGNANCY OF UNKNOWN LOCATION

Ultrasonography showing neither intrauterine nor ectopic pregnancy in a patient with a positive pregnancy test is referred to as a pregnancy of unknown location. In a desired pregnancy, β-hCG levels and serial ultrasonography combined with patient reports of pain or bleeding guide management. 20 In an undesired pregnancy or when the possibility of a viable intrauterine pregnancy has been excluded, manual vacuum aspiration of the uterus can evaluate for chorionic villi that differentiate intrauterine pregnancy loss from ectopic pregnancy. If chorionic villi are seen, further workup is unnecessary, and exposure to methotrexate can be avoided ( Figure 1 ) . 5 , 15 – 17 , 21 If chorionic villi are not seen after uterine aspiration, it is imperative to initiate treatment for ectopic pregnancy or repeat β-hCG measurement in 24 hours to ensure at least a 50% decrease. Ectopic precautions and serial β-hCG levels should be continued until the level is undetectable.

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

It is appropriate for family physicians to treat hemodynamically stable patients in conjunction with their primary obstetrician. Patients with suspected or confirmed ectopic pregnancy who exhibit signs and symptoms of ruptured ectopic pregnancy should be emergently transferred for surgical intervention. If ectopic pregnancy has been diagnosed, the patient is deemed clinically stable, and the affected fallopian tube has not ruptured, treatment options include medical management with intramuscular methotrexate or surgical management with salpingostomy (removal of the ectopic pregnancy while leaving the fallopian tube in place) or salpingectomy (removal of part or all of the affected fallopian tube). The decision to manage the ectopic pregnancy medically or surgically should be informed by individual patient factors and preferences, clinical findings, ultrasound findings, and β-hCG levels. 12 Expectant management is rare but can be considered with close follow-up for patients with suspected ectopic pregnancy who are asymptomatic and have β-hCG levels that are very low and continue to decrease. 5

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Intramuscular methotrexate is the only medication appropriate for the management of ectopic pregnancy. A folate antagonist, it interrupts the rapidly dividing cells of the ectopic pregnancy, which are then resorbed by the body. 22 Its success rate decreases with higher initial β-hCG levels ( Table 3 ) . 23 Contraindications to methotrexate include renal insufficiency; moderate to severe anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia; liver disease or alcoholism; active peptic ulcer disease; and breastfeeding. 5 Therefore, a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel should be obtained before it is administered.

Several methotrexate regimens have been studied, including a single-dose protocol, a two-dose protocol, and a multi-dose protocol ( Table 4 ) . 5 The single-dose protocol carries the lowest risk of adverse effects, whereas the two-dose protocol is more effective than the single-dose protocol in patients with higher initial β-hCG levels. 24 There is no consistent evidence or consensus regarding the cutoff above which a two-dose protocol should be used, so clinicians should choose a regimen based on the initial β-hCG level and ultrasound findings, as well as patient preference regarding effectiveness vs. the risk of adverse effects. In general, the single-dose protocol should be used in patients with β-hCG levels less than 3,600 mIU per mL (3,600 IU per L), and the two-dose protocol should be considered for patients with higher initial β-hCG levels, especially those with levels greater than 5,000 mIU per mL. Multidose protocols carry a higher risk of adverse effects and are not preferred. 25