- Campus News

- Campus Events

- Devotionals and Forums

- Readers’ Forum

- Education Week

- Breaking News

- Police Beat

- Video of the Day

- Current Issue

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- The Daily Universe Magazine, December 2022

- The Daily Universe, November 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, October 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, September 2022 (Black 14)

- The Daily Universe Magazine, March 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, February 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, January 2022

- December 2021

- The Daily Universe Magazine, November 2021

- The Daily Universe, October 2021

- The Daily Universe Magazine, September 2021

- Pathway to Education: Breaking Ground in Ghana

- Hope for Lahaina: Witnesses of the Maui Wildfires

- Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial

- The Black 14: Healing Hearts and Feeding Souls

- Camino de Santiago

- A Poor Wayfaring Man

- Palmyra: 200 years after Moroni’s visits

- The Next Normal

- Called to Serve In A Pandemic

- The World Meets Our Campus

- Defining Moments of BYU Sports

- If Any of You Lack Wisdom

The ‘scope’ of the argument: Why the Second Amendment matters

The U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of the right to bear arms has been a primary conversation topic among Americans in 2020. As uncertainty and fear have plagued the world over the last eight months, there has been a surge in gun sales nationwide — many of them to first-time owners.

Austin and Danielle, one young couple in Utah, had always talked about owning a firearm. Austin grew up in a city where gun ownership was less common, but Danielle grew up in a small town where gun ownership was normal. They both said the events of 2020 lead them to buy a firearm.

“We always talked about having a gun,” Austin said. “I thought they were probably important to have for self-defense. Once COVID-19 hit , it made getting one feel like an important purchase to make.”

The couple bought their gun in early April. While they believe in gun ownership, they wanted to keep their last name anonymous to avoid the negative stigma some associate with gun owners.

“I feel like a lot of people have a mental image of gun owners as uneducated or having low IQs,” Danielle said. “I do feel like most gun owners are responsible and only want them for recreation and self-defense purposes, but some people think they are hillbillies.”

The two cited the case of the Orem wildfires in mid-October, which were caused by target practice at a local gun range. They also mentioned a few other reasons they didn’t want to be labeled as “gun owners.”

“We wanted to remain anonymous because we didn’t want to be targeted for our political beliefs or because we choose to own a gun,” Austin said. “Remaining anonymous is a safe choice. That’s the reason I bought a gun — it’s something to protect my family and keep us safe.”

While some Americans have sought to restrict gun ownership, for many others it is a cherished right they work to protect. According to The New York Times , demand for guns has surged since the start of the pandemic in March and hasn’t let up all year. The National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) recorded an estimated 28 million background checks were requested from January to the end of September.

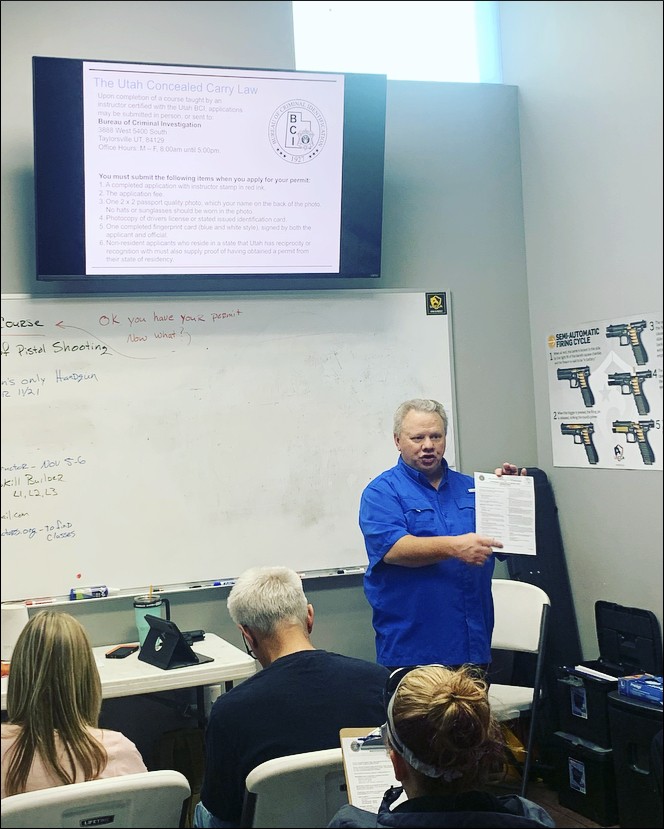

Jeffrey Denning, a Salt Lake City Police detective, teaches firearm safety classes to private parties. He has seen a dramatic increase in people wanting to exercise their Second Amendment rights.

“One gun store owner I talked to said the day after the Utah earthquake on March 13th, he received the most sales he had ever gotten,” Denning said. “After that, sales started going through the roof. The numbers are off the charts.”

According to the data reported by the NICS, the first spike (3.7 million background checks) in firearm demand happened in March likely because of the pandemic. The second spike (3.9 million background checks) was larger and occurred in June — right after acts of civil unrest began in major American cities.

“ People should be able to protect themselves individually and collectively,” Denning said. “We should be able to preserve our freedoms — this lets us have agency and a land of liberty.”

Denning said that while firearms are certainly good for personal protection, the reason the Second Amendment is considered a right is more complex than that.

“The Second Amendment was included in the Constitution so the government could not take over,” Denning said. “It’s to serve against government encroachments. The amendments were developed because of what the founding fathers saw in other parts of the world.”

Most historians agree that this was the premise of the Second Amendment. But some people have grown increasingly wary of the potential dangers of an armed population. Because of this fear, there has been heated debate in recent years over whether to update or reform the Second Amendment.

Lucy Williams, an assistant professor of political philosophy, said the conflict was most pronounced in the 2008 Supreme Court case D.C. v. Heller.

“For some time, there was a debate about whether the prefatory clause ‘A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State’ was intended to limit the right to bear arms or if it merely explained why the right is important,” Williams said. “The debate is now largely settled.”

Williams said reformers proposed that the Constitution only protects a right to bear arms in relation to military service. People who took the other position argued the right was not connected to military service. The Supreme Court sided with the latter position.

After this Supreme Court decision, it seems that the debate has shifted. Instead of asking whether individuals should be allowed to have firearms, the debate is focused on whether the government has the ability to regulate and restrict specific weapons from entering the public sphere.

This threat of potential regulation has made some Americans nervous, and conservative politicians say the Second Amendment is under attack, or will be eliminated because of their political opponents. Williams said this is not likely.

“Although the scope of (the Second Amendment) may change, it’s hard to imagine that the right could ever be eliminated entirely,” Williams said.

Though reform may happen in the future, more people are making use of their Second Amendment right. Background checks, first-time gun purchases and training classes are increasing in demand. It remains to be seen whether gun sales will trend downward anytime soon.

“If you haven’t had a gun in 70 years, and are only interested in one because you’re scared, there is no reason to buy one now,” Denning said. “You are going to be fine.”

Despite this, Denning said individuals who have considered buying a gun and want to educate themselves should do so.

“It’s ignorant and foolish not to have a plan for preparation and protection,” Denning said. “You can think all day long that something won’t happen ‘here’ or ‘to you’ but if it does, you’re not going to be prepared.”

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Struggles and successes: first-generation college students at byu, cougar pride center’s annual march ‘pride in progress’ promotes unity, acceptance, byu football and the nfl draft: which former cougars are joining the league.

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, interpretation & debate, the second amendment, matters of debate, common interpretation, the reasonable right to bear arms, not a second class right: the second amendment today.

by Nelson Lund

University Professor at George Mason University University Antonin Scalia School of Law

by Adam Winkler

Professor of Law at University of California Los Angeles Law School

Modern debates about the Second Amendment have focused on whether it protects a private right of individuals to keep and bear arms, or a right that can be exercised only through militia organizations like the National Guard. This question, however, was not even raised until long after the Bill of Rights was adopted.

Many in the Founding generation believed that governments are prone to use soldiers to oppress the people. English history suggested that this risk could be controlled by permitting the government to raise armies (consisting of full-time paid troops) only when needed to fight foreign adversaries. For other purposes, such as responding to sudden invasions or other emergencies, the government could rely on a militia that consisted of ordinary civilians who supplied their own weapons and received some part-time, unpaid military training.

The onset of war does not always allow time to raise and train an army, and the Revolutionary War showed that militia forces could not be relied on for national defense. The Constitutional Convention therefore decided that the federal government should have almost unfettered authority to establish peacetime standing armies and to regulate the militia.

This massive shift of power from the states to the federal government generated one of the chief objections to the proposed Constitution. Anti-Federalists argued that the proposed Constitution would take from the states their principal means of defense against federal usurpation. The Federalists responded that fears of federal oppression were overblown, in part because the American people were armed and would be almost impossible to subdue through military force.

Implicit in the debate between Federalists and Anti-Federalists were two shared assumptions. First, that the proposed new Constitution gave the federal government almost total legal authority over the army and militia. Second, that the federal government should not have any authority at all to disarm the citizenry. They disagreed only about whether an armed populace could adequately deter federal oppression.

The Second Amendment conceded nothing to the Anti-Federalists’ desire to sharply curtail the military power of the federal government, which would have required substantial changes in the original Constitution. Yet the Amendment was easily accepted because of widespread agreement that the federal government should not have the power to infringe the right of the people to keep and bear arms, any more than it should have the power to abridge the freedom of speech or prohibit the free exercise of religion.

Much has changed since 1791. The traditional militia fell into desuetude, and state-based militia organizations were eventually incorporated into the federal military structure. The nation’s military establishment has become enormously more powerful than eighteenth century armies. We still hear political rhetoric about federal tyranny, but most Americans do not fear the nation’s armed forces and virtually no one thinks that an armed populace could defeat those forces in battle. Furthermore, eighteenth century civilians routinely kept at home the very same weapons they would need if called to serve in the militia, while modern soldiers are equipped with weapons that differ significantly from those generally thought appropriate for civilian uses. Civilians no longer expect to use their household weapons for militia duty, although they still keep and bear arms to defend against common criminals (as well as for hunting and other forms of recreation).

The law has also changed. While states in the Founding era regulated guns—blacks were often prohibited from possessing firearms and militia weapons were frequently registered on government rolls—gun laws today are more extensive and controversial. Another important legal development was the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Second Amendment originally applied only to the federal government, leaving the states to regulate weapons as they saw fit. Although there is substantial evidence that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to protect the right of individuals to keep and bear arms from infringement by the states, the Supreme Court rejected this interpretation in United States v. Cruikshank (1876).

Until recently, the judiciary treated the Second Amendment almost as a dead letter. In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), however, the Supreme Court invalidated a federal law that forbade nearly all civilians from possessing handguns in the nation’s capital. A 5–4 majority ruled that the language and history of the Second Amendment showed that it protects a private right of individuals to have arms for their own defense, not a right of the states to maintain a militia.

The dissenters disagreed. They concluded that the Second Amendment protects a nominally individual right, though one that protects only “the right of the people of each of the several States to maintain a well-regulated militia.” They also argued that even if the Second Amendment did protect an individual right to have arms for self-defense, it should be interpreted to allow the government to ban handguns in high-crime urban areas.

Two years later, in McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010), the Court struck down a similar handgun ban at the state level, again by a 5–4 vote. Four Justices relied on judicial precedents under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. Justice Thomas rejected those precedents in favor of reliance on the Privileges or Immunities Clause, but all five members of the majority concluded that the Fourteenth Amendment protects against state infringement of the same individual right that is protected from federal infringement by the Second Amendment.

Notwithstanding the lengthy opinions in Heller and McDonald , they technically ruled only that government may not ban the possession of handguns by civilians in their homes. Heller tentatively suggested a list of “presumptively lawful” regulations, including bans on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, bans on carrying firearms in “sensitive places” such as schools and government buildings, laws restricting the commercial sale of arms, bans on the concealed carry of firearms, and bans on weapons “not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes.” Many issues remain open, and the lower courts have disagreed with one another about some of them, including important questions involving restrictions on carrying weapons in public.

Gun control is as much a part of the Second Amendment as the right to keep and bear arms. The text of the amendment, which refers to a “well regulated Militia,” suggests as much. As the Supreme Court correctly noted in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the militia of the founding era was the body of ordinary citizens capable of taking up arms to defend the nation. While the Founders sought to protect the citizenry from being disarmed entirely, they did not wish to prevent government from adopting reasonable regulations of guns and gun owners.

Although Americans today often think that gun control is a modern invention, the Founding era had laws regulating the armed citizenry. There were laws designed to ensure an effective militia, such as laws requiring armed citizens to appear at mandatory musters where their guns would be inspected. Governments also compiled registries of civilian-owned guns appropriate for militia service, sometimes conducting door-to-door surveys. The Founders had broad bans on gun possession by people deemed untrustworthy, including slaves and loyalists. The Founders even had laws requiring people to have guns appropriate for militia service.

The wide range of Founding-era laws suggests that the Founders understood gun rights quite differently from many people today. The right to keep and bear arms was not a libertarian license for anyone to have any kind of ordinary firearm, anywhere they wanted. Nor did the Second Amendment protect a right to revolt against a tyrannical government. The Second Amendment was about ensuring public safety, and nothing in its language was thought to prevent what would be seen today as quite burdensome forms of regulation.

The Founding-era laws indicate why the First Amendment is not a good analogy to the Second. While there have always been laws restricting perjury and fraud by the spoken word, such speech was not thought to be part of the freedom of speech. The Second Amendment, by contrast, unambiguously recognizes that the armed citizenry must be regulated—and regulated “well.” This language most closely aligns with the Fourth Amendment, which protects a right to privacy but also recognizes the authority of the government to conduct reasonable searches and seizures.

The principle that reasonable regulations are consistent with the Second Amendment has been affirmed throughout American history. Ever since the first cases challenging gun controls for violating the Second Amendment or similar provisions in state constitutions, courts have repeatedly held that “reasonable” gun laws—those that don’t completely deny access to guns by law-abiding people—are constitutionally permissible. For 150 years, this was the settled law of the land—until Heller .

Heller , however, rejected the principle of reasonableness only in name, not in practice. The decision insisted that many types of gun control laws are presumptively lawful, including bans on possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, bans on concealed carry, bans on dangerous and unusual weapons, restrictions on guns in sensitive places like schools and government buildings, and commercial sale restrictions. Nearly all gun control laws today fit within these exceptions. Importantly, these exceptions for modern-day gun laws unheard of in the Founding era also show that lawmakers are not limited to the types of gun control in place at the time of the Second Amendment’s ratification.

In the years since Heller , the federal courts have upheld the overwhelming majority of gun control laws challenged under the Second Amendment. Bans on assault weapons have been consistently upheld, as have restrictions on gun magazines that hold more than a minimum number of rounds of ammunition. Bans on guns in national parks, post offices, bars, and college campuses also survived. These decisions make clear that lawmakers have wide leeway to restrict guns to promote public safety so long as the basic right of law-abiding people to have a gun for self-defense is preserved.

Perhaps the biggest open question after Heller is whether the Second Amendment protects a right to carry guns in public. While every state allows public carry, some states restrict that right to people who can show a special reason to have a gun on the street. To the extent these laws give local law enforcement unfettered discretion over who can carry, they are problematic. At the same time, however, many constitutional rights are far more limited in public than in the home. Parades can be required to have a permit, the police have broader powers to search pedestrians and motorists than private homes, and sexual intimacy in public places can be completely prohibited.

The Supreme Court may yet decide that more stringent limits on gun control are required under the Second Amendment. Such a decision, however, would be contrary to the text, history, and tradition of the right to keep and bear arms.

The right to keep and bear arms is a lot like the right to freedom of speech. In each case, the Constitution expressly protects a liberty that needs to be insulated from the ordinary political process. Neither right, however, is absolute. The First Amendment, for example, has never protected perjury, fraud, or countless other crimes that are committed through the use of speech. Similarly, no reasonable person could believe that violent criminals should have unrestricted access to guns, or that any individual should possess a nuclear weapon.

Inevitably, courts must draw lines, allowing government to carry out its duty to preserve an orderly society, without unduly infringing the legitimate interests of individuals in expressing their thoughts and protecting themselves from criminal violence. This is not a precise science or one that will ever be free from controversy.

One judicial approach, however, should be unequivocally rejected. During the nineteenth century, courts routinely refused to invalidate restrictions on free speech that struck the judges as reasonable. This meant that speech got virtually no judicial protection. Government suppression of speech can usually be thought to serve some reasonable purpose, such as reducing social discord or promoting healthy morals. Similarly, most gun control laws can be viewed as efforts to save lives and prevent crime, which are perfectly reasonable goals. If that’s enough to justify infringements on individual liberty, neither constitutional guarantee means much of anything.

During the twentieth century, the Supreme Court finally started taking the First Amendment seriously. Today, individual freedom is generally protected unless the government can make a strong case that it has a real need to suppress speech or expressive conduct, and that its regulations are tailored to that need. The legal doctrines have become quite complex, and there is room for disagreement about many of the Court’s specific decisions. Taken as a whole, however, this body of case law shows what the Court can do when it appreciates the value of an individual right enshrined in the Constitution.

The Second Amendment also raises issues about which reasonable people can disagree. But if the Supreme Court takes this provision of the Constitution as seriously as it now takes the First Amendment, which it should do, there will be some easy issues as well.

• District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) is one example. The “right of the people” protected by the Second Amendment is an individual right, just like the “right[s] of the people” protected by the First and Fourth Amendments. The Constitution does not say that the Second Amendment protects a right of the states or a right of the militia, and nobody offered such an interpretation during the Founding era. Abundant historical evidence indicates that the Second Amendment was meant to leave citizens with the ability to defend themselves against unlawful violence. Such threats might come from usurpers of governmental power, but they might also come from criminals whom the government is unwilling or unable to control.

• McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010) was also an easy case under the Court’s precedents. Most other provisions of the Bill of Rights had already been applied to the states because they are “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition.” The right to keep and bear arms clearly meets this test.

• The text of the Constitution expressly guarantees the right to bear arms, not just the right to keep them. The courts should invalidate regulations that prevent law-abiding citizens from carrying weapons in public, where the vast majority of violent crimes occur. First Amendment rights are not confined to the home, and neither are those protected by the Second Amendment.

• Nor should the government be allowed to create burdensome bureaucratic obstacles designed to frustrate the exercise of Second Amendment rights. The courts are vigilant in preventing government from evading the First Amendment through regulations that indirectly abridge free speech rights by making them difficult to exercise. Courts should exercise the same vigilance in protecting Second Amendment rights.

• Some other regulations that may appear innocuous should be struck down because they are little more than political stunts. Popular bans on so-called “assault rifles,” for example, define this class of guns in terms of cosmetic features, leaving functionally identical semi-automatic rifles to circulate freely. This is unconstitutional for the same reason that it would violate the First Amendment to ban words that have a French etymology, or to require that French fries be called “freedom fries.”

In most American states, including many with large urban population centers, responsible adults have easy access to ordinary firearms, and they are permitted to carry them in public. Experience has shown that these policies do not lead to increased levels of violence. Criminals pay no more attention to gun control regulations than they do to laws against murder, rape, and robbery. Armed citizens, however, prevent countless crimes and have saved many lives. What’s more, the most vulnerable people—including women, the elderly, and those who live in high crime neighborhoods—are among the greatest beneficiaries of the Second Amendment. If the courts require the remaining jurisdictions to stop infringing on the constitutional right to keep and bear arms, their citizens will be more free and probably safer as well.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Second Amendment

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 27, 2023 | Original: December 4, 2017

The Second Amendment, often referred to as the right to bear arms, is one of 10 amendments that form the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791 by the U.S. Congress. Differing interpretations of the amendment have fueled a long-running debate over gun control legislation and the rights of individual citizens to buy, own and carry firearms.

Right to Bear Arms

The text of the Second Amendment reads in full: “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The framers of the Bill of Rights adapted the wording of the amendment from nearly identical clauses in some of the original 13 state constitutions.

During the Revolutionary War era, “militia” referred to groups of men who banded together to protect their communities, towns, colonies and eventually states, once the United States declared its independence from Great Britain in 1776.

Many people in America at the time believed governments used soldiers to oppress the people, and thought the federal government should only be allowed to raise armies (with full-time, paid soldiers) when facing foreign adversaries. For all other purposes, they believed, it should turn to part-time militias, or ordinary civilians using their own weapons.

State Militias

But as militias had proved insufficient against the British, the Constitutional Convention gave the new federal government the power to establish a standing army, even in peacetime.

However, opponents of a strong central government (known as Anti-Federalists) argued that this federal army deprived states of their ability to defend themselves against oppression. They feared that Congress might abuse its constitutional power of “organizing, arming and disciplining the Militia” by failing to keep militiamen equipped with adequate arms.

So, shortly after the U.S. Constitution was officially ratified, James Madison proposed the Second Amendment as a way to empower these state militias. While the Second Amendment did not answer the broader Anti-Federalist concern that the federal government had too much power, it did establish the principle (held by both Federalists and their opponents) that the government did not have the authority to disarm citizens.

Well-Regulated Militia

Practically since its ratification, Americans have debated the meaning of the Second Amendment, with vehement arguments being made on both sides.

The crux of the debate is whether the amendment protects the right of private individuals to keep and bear arms, or whether it instead protects a collective right that should be exercised only through formal militia units.

Those who argue it is a collective right point to the “well-regulated Militia” clause in the Second Amendment. They argue that the right to bear arms should be given only to organized groups, like the National Guard, a reserve military force that replaced the state militias after the Civil War .

On the other side are those who argue that the Second Amendment gives all citizens, not just militias, the right to own guns in order to protect themselves. The National Rifle Association (NRA) , founded in 1871, and its supporters have been the most visible proponents of this argument, and have pursued a vigorous campaign against gun control measures at the local, state and federal levels.

Those who support stricter gun control legislation have argued that limits are necessary on gun ownership, including who can own them, where they can be carried and what type of guns should be available for purchase.

Congress passed one of the most high-profile federal gun control efforts, the so-called Brady Bill , in the 1990s, largely thanks to the efforts of former White House Press Secretary James S. Brady, who had been shot in the head during an assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

District of Columbia v. Heller

Since the passage of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which mandated background checks for gun purchases from licensed dealers, the debate on gun control has changed dramatically.

This is partially due to the actions of the Supreme Court , which departed from its past stance on the Second Amendment with its verdicts in two major cases, District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) and McDonald v. Chicago (2010).

For a long time, the federal judiciary held the opinion that the Second Amendment remained among the few provisions of the Bill of Rights that did not fall under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment , which would thereby apply its limitations to state governments. For example, in the 1886 case Presser v. Illinois , the Court held that the Second Amendment applied only to the federal government, and did not prohibit state governments from regulating an individual’s ownership or use of guns.

But in its 5-4 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller , which invalidated a federal law barring nearly all civilians from possessing guns in the District of Columbia, the Supreme Court extended Second Amendment protection to individuals in federal (non-state) enclaves.

Writing the majority decision in that case, Justice Antonin Scalia lent the Court’s weight to the idea that the Second Amendment protects the right of individual private gun ownership for self-defense purposes.

McDonald v. Chicago

Two years later, in McDonald v. Chicago , the Supreme Court struck down (also in a 5-4 decision) a similar citywide handgun ban, ruling that the Second Amendment applies to the states as well as to the federal government.

In the majority ruling in that case, Justice Samuel Alito wrote: “Self-defense is a basic right, recognized by many legal systems from ancient times to the present day, and in Heller , we held that individual self-defense is ‘the central component’ of the Second Amendment right.”

Gun Control Debate

The Supreme Court’s narrow rulings in the Heller and McDonald cases left open many key issues in the gun control debate.

In the Heller decision, the Court suggested a list of “presumptively lawful” regulations, including bans on possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill; bans on carrying arms in schools and government buildings; restrictions on gun sales; bans on the concealed carrying of weapons; and generally bans on weapons “not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes.”

Mass Shootings

Since that verdict, as lower courts battle back and forth on cases involving such restrictions, the public debate over Second Amendment rights and gun control remains very much open, even as mass shootings became an increasingly frequent occurrence in American life.

To take just three examples, the Columbine Shooting , where two teens killed 13 people at Columbine High School, prompted a national gun control debate. The Sandy Hook shooting of 20 children and six staff members at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut in 2012 led President Barack Obama and many others to call for tighter background checks and a renewed ban on assault weapons.

And in 2017, the mass shooting at country music concert in Las Vegas in which 60 people died (to date the largest mass shooting in U.S. history, overtaking the 2016 attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida ) inspired calls to restrict sales of “bump stocks,” attachments that enable semiautomatic weapons to fire faster.

On the other side of the ongoing debate of gun control measures are the NRA and other gun rights supporters, powerful and vocal groups that views such restrictions as an unacceptable violation of their Second Amendment rights.

Bill of Rights, The Oxford Guide to the United States Government . Jack Rakove, ed. The Annotated U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence. Amendment II, National Constitution Center . The Second Amendment and the Right to Bear Arms, LiveScience . Second Amendment, Legal Information Institute .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- White House

Read Barack Obama’s Speech on New Gun Control Measures

P resident Barack Obama unveiled a new set of executive actions aimed at limiting gun violence in a press conference Tuesday from the White House. The efforts largely center on more stringent background checks.

Here’s a full transcript of his remarks.

THE PRESIDENT: Mark, I want to thank you for your introduction. I still remember the first time we met, the time we spent together, and the conversation we had about Daniel. And that changed me that day. And my hope, earnestly, has been that it would change the country. Five years ago this week, a sitting member of Congress and 18 others were shot at, at a supermarket in Tucson, Arizona. It wasn’t the first time I had to talk to the nation in response to a mass shooting, nor would it be the last. Fort Hood. Binghamton. Aurora. Oak Creek. Newtown. The Navy Yard. Santa Barbara. Charleston. San Bernardino. Too many. AUDIENCE MEMBER: Too many. AUDIENCE MEMBER: Too many. AUDIENCE MEMBER: Too many. THE PRESIDENT: Thanks to a great medical team and the love of her husband, Mark, my dear friend and colleague, Gabby Giffords, survived. She’s here with us today, with her wonderful mom. (Applause.) Thanks to a great medical team, her wonderful husband, Mark — who, by the way, the last time I met with Mark — this is just a small aside — you may know Mark’s twin brother is in outer space. (Laughter.) He came to the office, and I said, how often are you talking to him? And he says, well, I usually talk to him every day, but the call was coming in right before the meeting so I think I may have not answered his call — (laughter) — which made me feel kind of bad. (Laughter.) That’s a long-distance call. (Laughter.) So I told him if his brother, Scott, is calling today, that he should take it. (Laughter.) Turn the ringer on. (Laughter.) I was there with Gabby when she was still in the hospital, and we didn’t think necessarily at that point that she was going to survive. And that visit right before a memorial — about an hour later Gabby first opened her eyes. And I remember talking to mom about that. But I know the pain that she and her family have endured these past five years, and the rehabilitation and the work and the effort to recover from shattering injuries. And then I think of all the Americans who aren’t as fortunate. Every single year, more than 30,000 Americans have their lives cut short by guns — 30,000. Suicides. Domestic violence. Gang shootouts. Accidents. Hundreds of thousands of Americans have lost brothers and sisters, or buried their own children. Many have had to learn to live with a disability, or learned to live without the love of their life. A number of those people are here today. They can tell you some stories. In this room right here, there are a lot of stories. There’s a lot of heartache. There’s a lot of resilience, there’s a lot of strength, but there’s also a lot of pain. And this is just a small sample. The United States of America is not the only country on Earth with violent or dangerous people. We are not inherently more prone to violence. But we are the only advanced country on Earth that sees this kind of mass violence erupt with this kind of frequency. It doesn’t happen in other advanced countries. It’s not even close. And as I’ve said before, somehow we’ve become numb to it and we start thinking that this is normal. And instead of thinking about how to solve the problem, this has become one of our most polarized, partisan debates — despite the fact that there’s a general consensus in America about what needs to be done. That’s part of the reason why, on Thursday, I’m going to hold a town hall meeting in Virginia on gun violence. Because my goal here is to bring good people on both sides of this issue together for an open discussion. I’m not on the ballot again. I’m not looking to score some points. I think we can disagree without impugning other people’s motives or without being disagreeable. We don’t need to be talking past one another. But we do have to feel a sense of urgency about it. In Dr. King’s words, we need to feel the “fierce urgency of now.” Because people are dying. And the constant excuses for inaction no longer do, no longer suffice. That’s why we’re here today. Not to debate the last mass shooting, but to do something to try to prevent the next one. (Applause.) To prove that the vast majority of Americans, even if our voices aren’t always the loudest or most extreme, care enough about a little boy like Daniel to come together and take common-sense steps to save lives and protect more of our children. Now, I want to be absolutely clear at the start — and I’ve said this over and over again, this also becomes routine, there is a ritual about this whole thing that I have to do — I believe in the Second Amendment. It’s there written on the paper. It guarantees a right to bear arms. No matter how many times people try to twist my words around — I taught constitutional law, I know a little about this — (applause) — I get it. But I also believe that we can find ways to reduce gun violence consistent with the Second Amendment. I mean, think about it. We all believe in the First Amendment, the guarantee of free speech, but we accept that you can’t yell “fire” in a theater. We understand there are some constraints on our freedom in order to protect innocent people. We cherish our right to privacy, but we accept that you have to go through metal detectors before being allowed to board a plane. It’s not because people like doing that, but we understand that that’s part of the price of living in a civilized society. And what’s often ignored in this debate is that a majority of gun owners actually agree. A majority of gun owners agree that we can respect the Second Amendment while keeping an irresponsible, law-breaking feud from inflicting harm on a massive scale. Today, background checks are required at gun stores. If a father wants to teach his daughter how to hunt, he can walk into a gun store, get a background check, purchase his weapon safely and responsibly. This is not seen as an infringement on the Second Amendment. Contrary to the claims of what some gun rights proponents have suggested, this hasn’t been the first step in some slippery slope to mass confiscation. Contrary to claims of some presidential candidates, apparently, before this meeting, this is not a plot to take away everybody’s guns. You pass a background check; you purchase a firearm. The problem is some gun sellers have been operating under a different set of rules. A violent felon can buy the exact same weapon over the Internet with no background check, no questions asked. A recent study found that about one in 30 people looking to buy guns on one website had criminal records — one out of 30 had a criminal record. We’re talking about individuals convicted of serious crimes — aggravated assault, domestic violence, robbery, illegal gun possession. People with lengthy criminal histories buying deadly weapons all too easily. And this was just one website within the span of a few months. So we’ve created a system in which dangerous people are allowed to play by a different set of rules than a responsible gun owner who buys his or her gun the right way and subjects themselves to a background check. That doesn’t make sense. Everybody should have to abide by the same rules. Most Americans and gun owners agree. And that’s what we tried to change three years ago, after 26 Americans -– including 20 children -– were murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary. Two United States Senators -– Joe Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, and Pat Toomey, a Republican from Pennsylvania, both gun owners, both strong defenders of our Second Amendment rights, both with “A” grades from the NRA –- that’s hard to get — worked together in good faith, consulting with folks like our Vice President, who has been a champion on this for a long time, to write a common-sense compromise bill that would have required virtually everyone who buys a gun to get a background check. That was it. Pretty common-sense stuff. Ninety percent of Americans supported that idea. Ninety percent of Democrats in the Senate voted for that idea. But it failed because 90 percent of Republicans in the Senate voted against that idea. How did this become such a partisan issue? Republican President George W. Bush once said, “I believe in background checks at gun shows or anywhere to make sure that guns don’t get into the hands of people that shouldn’t have them.” Senator John McCain introduced a bipartisan measure to address the gun show loophole, saying, “We need this amendment because criminals and terrorists have exploited and are exploiting this very obvious loophole in our gun safety laws.” Even the NRA used to support expanded background checks. And by the way, most of its members still do. Most Republican voters still do. How did we get here? How did we get to the place where people think requiring a comprehensive background check means taking away people’s guns? Each time this comes up, we are fed the excuse that common-sense reforms like background checks might not have stopped the last massacre, or the one before that, or the one before that, so why bother trying. I reject that thinking. (Applause.) We know we can’t stop every act of violence, every act of evil in the world. But maybe we could try to stop one act of evil, one act of violence. Some of you may recall, at the same time that Sandy Hook happened, a disturbed person in China took a knife and tried to kill — with a knife — a bunch of children in China. But most of them survived because he didn’t have access to a powerful weapon. We maybe can’t save everybody, but we could save some. Just as we don’t prevent all traffic accidents but we take steps to try to reduce traffic accidents. As Ronald Reagan once said, if mandatory background checks could save more lives, “it would be well worth making it the law of the land.” The bill before Congress three years ago met that test. Unfortunately, too many senators failed theirs. (Applause.) In fact, we know that background checks make a difference. After Connecticut passed a law requiring background checks and gun safety courses, gun deaths decreased by 40 percent — 40 percent. (Applause.) Meanwhile, since Missouri repealed a law requiring comprehensive background checks and purchase permits, gun deaths have increased to almost 50 percent higher than the national average. One study found, unsurprisingly, that criminals in Missouri now have easier access to guns. And the evidence tells us that in states that require background checks, law-abiding Americans don’t find it any harder to purchase guns whatsoever. Their guns have not been confiscated. Their rights have not been infringed. And that’s just the information we have access to. With more research, we could further improve gun safety. Just as with more research, we’ve reduced traffic fatalities enormously over the last 30 years. We do research when cars, food, medicine, even toys harm people so that we make them safer. And you know what — research, science — those are good things. They work. (Laughter and applause.) They do. But think about this. When it comes to an inherently deadly weapon — nobody argues that guns are potentially deadly — weapons that kill tens of thousands of Americans every year, Congress actually voted to make it harder for public health experts to conduct research into gun violence; made it harder to collect data and facts and develop strategies to reduce gun violence. Even after San Bernardino, they’ve refused to make it harder for terror suspects who can’t get on a plane to buy semi-automatic weapons. That’s not right. That can’t be right. So the gun lobby may be holding Congress hostage right now, but they cannot hold America hostage. (Applause.) We do not have to accept this carnage as the price of freedom. (Applause.) Now, I want to be clear. Congress still needs to act. The folks in this room will not rest until Congress does. (Applause.) Because once Congress gets on board with common-sense gun safety measures we can reduce gun violence a whole lot more. But we also can’t wait. Until we have a Congress that’s in line with the majority of Americans, there are actions within my legal authority that we can take to help reduce gun violence and save more lives -– actions that protect our rights and our kids. After Sandy Hook, Joe and I worked together with our teams and we put forward a whole series of executive actions to try to tighten up the existing rules and systems that we had in place. But today, we want to take it a step further. So let me outline what we’re going to be doing. Number one, anybody in the business of selling firearms must get a license and conduct background checks, or be subject to criminal prosecutions. (Applause.) It doesn’t matter whether you’re doing it over the Internet or at a gun show. It’s not where you do it, but what you do. We’re also expanding background checks to cover violent criminals who try to buy some of the most dangerous firearms by hiding behind trusts and corporations and various cutouts. We’re also taking steps to make the background check system more efficient. Under the guidance of Jim Comey and the FBI, our Deputy Director Tom Brandon at ATF, we’re going to hire more folks to process applications faster, and we’re going to bring an outdated background check system into the 21st century. (Applause.) And these steps will actually lead to a smoother process for law-abiding gun owners, a smoother process for responsible gun dealers, a stronger process for protecting the people from — the public from dangerous people. So that’s number one. Number two, we’re going to do everything we can to ensure the smart and effective enforcement of gun safety laws that are already on the books, which means we’re going to add 200 more ATF agents and investigators. We’re going to require firearms dealers to report more lost or stolen guns on a timely basis. We’re working with advocates to protect victims of domestic abuse from gun violence, where too often — (applause) — where too often, people are not getting the protection that they need. Number three, we’re going to do more to help those suffering from mental illness get the help that they need. (Applause.) High-profile mass shootings tend to shine a light on those few mentally unstable people who inflict harm on others. But the truth is, is that nearly two in three gun deaths are from suicides. So a lot of our work is to prevent people from hurting themselves. That’s why we made sure that the Affordable Care Act — also known as Obamacare — (laughter and applause) — that law made sure that treatment for mental health was covered the same as treatment for any other illness. And that’s why we’re going to invest $500 million to expand access to treatment across the country. (Applause.) It’s also why we’re going to ensure that federal mental health records are submitted to the background check system, and remove barriers that prevent states from reporting relevant information. If we can continue to de-stigmatize mental health issues, get folks proper care, and fill gaps in the background check system, then we can spare more families the pain of losing a loved one to suicide. And for those in Congress who so often rush to blame mental illness for mass shootings as a way of avoiding action on guns, here’s your chance to support these efforts. Put your money where your mouth is. (Applause.) Number four, we’re going to boost gun safety technology. Today, many gun injuries and deaths are the result of legal guns that were stolen or misused or discharged accidentally. In 2013 alone, more than 500 people lost their lives to gun accidents –- and that includes 30 children younger than five years old. In the greatest, most technologically advanced nation on Earth, there is no reason for this. We need to develop new technologies that make guns safer. If we can set it up so you can’t unlock your phone unless you’ve got the right fingerprint, why can’t we do the same thing for our guns? (Applause.) If there’s an app that can help us find a missing tablet — which happens to me often the older I get — (laughter) — if we can do it for your iPad, there’s no reason we can’t do it with a stolen gun. If a child can’t open a bottle of aspirin, we should make sure that they can’t pull a trigger on a gun. (Applause.) Right? So we’re going to advance research. We’re going to work with the private sector to update firearms technology. And some gun retailers are already stepping up by refusing to finalize a purchase without a complete background check, or by refraining from selling semi-automatic weapons or high-capacity magazines. And I hope that more retailers and more manufacturers join them — because they should care as much as anybody about a product that now kills almost as many Americans as car accidents. I make this point because none of us can do this alone. I think Mark made that point earlier. All of us should be able to work together to find a balance that declares the rest of our rights are also important — Second Amendment rights are important, but there are other rights that we care about as well. And we have to be able to balance them. Because our right to worship freely and safely –- that right was denied to Christians in Charleston, South Carolina. (Applause.) And that was denied Jews in Kansas City. And that was denied Muslims in Chapel Hill, and Sikhs in Oak Creek. (Applause.) They had rights, too. (Applause.) Our right to peaceful assembly -– that right was robbed from moviegoers in Aurora and Lafayette. Our unalienable right to life, and liberty, and the pursuit of happiness -– those rights were stripped from college students in Blacksburg and Santa Barbara, and from high schoolers at Columbine, and from first-graders in Newtown. First-graders. And from every family who never imagined that their loved one would be taken from our lives by a bullet from a gun. Every time I think about those kids it gets me mad. And by the way, it happens on the streets of Chicago every day. (Applause.) So all of us need to demand a Congress brave enough to stand up to the gun lobby’s lies. All of us need to stand up and protect its citizens. All of us need to demand governors and legislatures and businesses do their part to make our communities safer. We need the wide majority of responsible gun owners who grieve with us every time this happens and feel like your views are not being properly represented to join with us to demand something better. (Applause.) And we need voters who want safer gun laws, and who are disappointed in leaders who stand in their way, to remember come election time. (Applause.) I mean, some of this is just simple math. Yes, the gun lobby is loud and it is organized in defense of making it effortless for guns to be available for anybody, any time. Well, you know what, the rest of us, we all have to be just as passionate. We have to be just as organized in defense of our kids. This is not that complicated. The reason Congress blocks laws is because they want to win elections. And if you make it hard for them to win an election if they block those laws, they’ll change course, I promise you. (Applause.) And, yes, it will be hard, and it won’t happen overnight. It won’t happen during this Congress. It won’t happen during my presidency. But a lot of things don’t happen overnight. A woman’s right to vote didn’t happen overnight. The liberation of African Americans didn’t happen overnight. LGBT rights — that was decades’ worth of work. So just because it’s hard, that’s no excuse not to try. And if you have any doubt as to why you should feel that “fierce urgency of now,” think about what happened three weeks ago. Zaevion Dobson was a sophomore at Fulton High School in Knoxville, Tennessee. He played football; beloved by his classmates and his teachers. His own mayor called him one of their city’s success stories. The week before Christmas, he headed to a friend’s house to play video games. He wasn’t in the wrong place at the wrong time. He hadn’t made a bad decision. He was exactly where any other kid would be. Your kid. My kids. And then gunmen started firing. And Zaevion — who was in high school, hadn’t even gotten started in life — dove on top of three girls to shield them from the bullets. And he was shot in the head. And the girls were spared. He gave his life to save theirs –- an act of heroism a lot bigger than anything we should ever expect from a 15-year-old. “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends.” We are not asked to do what Zaevion Dobson did. We’re not asked to have shoulders that big; a heart that strong; reactions that quick. I’m not asking people to have that same level of courage, or sacrifice, or love. But if we love our kids and care about their prospects, and if we love this country and care about its future, then we can find the courage to vote. We can find the courage to get mobilized and organized. We can find the courage to cut through all the noise and do what a sensible country would do. That’s what we’re doing today. And tomorrow, we should do more. And we should do more the day after that. And if we do, we’ll leave behind a nation that’s stronger than the one we inherited and worthy of the sacrifice of a young man like Zaevion. (Applause.) Thank you very much, everybody. God bless you. Thank you. God bless America. (Applause.)

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Discussing Controversial Topics: The Second Amendment

In July of 2012, a g

Bill of Rights Institute Resources

- The United States Constitution

- The United States Bill of Rights

- District of Columbia v. Heller (2008)

- McDonald v. Chicago (2010)

News Resources

- Temple massacre has some Sikhs mulling gun ownership , FOX News

- Candidates show little appetite for new gun control laws , CNN

- Gunman Dies After Killing at Empire State Building , New York Times

Ac tivity/How to Use

- What right does the Second Amendment protect?

- No right in the Bill of Rights is considered absolute. What limits on firearms has the Supreme Court ruled are constitutional? What limits on firearms do you believe are constitutional?

- One group should prepare to argue that high profile shootings are reasons to increase gun control.

- The other should prepare to argue that high profile shootings are reasons to loosen restrictions on firearms.

- Speak courteously: No raised voices or insults.

- Listen courteously: No interruptions.

- Argue authoritatively: Use primary sources to support reasoning.

- Distribute “Questions to Consider” to help students prepare their data and arguments. The teacher may add additional questions during the debate to help clarify or extend arguments.

- Students will have to think about why they are for or against increasing or decreasing gun control.

- Students should use primary sources and facts to support their argument.

- Students should think about why the opposing group believes what they believe and be able to respond to that argument.

- Alternate which team answers the questions first.

- Allow students from the opposing group to ask clarifying questions if necessary.

- Give each group a time limit on each question to keep the debate moving.

Questions to Consider

What right does the Second Amendment to the Constitution protect? Do you think this protection is necessary? Why or why not? Why did the Founders include the Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights? Do you think that their reasons are still valid today? Why or why not? What has the Supreme Court ruled about the meaning of the Second Amendment? Do you agree with their reasoning and conclusions? What types of restrictions have local and state governments put on weapons? What laws have local and state governments proposed? Do you support or oppose these restrictions? Explain. What laws would you propose regarding gun control? How do you think the public would react to your ideas? Why do you think gun control is controversial? During the Empire State Building shooting, it is believed that police officers fired shots at the accused shooter and accidentally wounded nine bystanders. A grand jury is now reviewing evidence in this case to determine whether the officers should stand charges. How does this knowledge impact your understanding of the Second Amendment? How does it impact your opinion on gun control regulations?

- After the debate, students should think about what they learned from reading the articles and debating on the the topic. They should write a brief essay explaining what they learned and if their opinion changed after thinking about the issue.

- Students should research laws regarding guns in your state or community and then write a brief essay explaining one of the laws. Examples may include limits on sale or ownership of certain weapons, concealed carry requirements, limits on gun purchases, or others. Their essay should include reasons the law was proposed or passed, what the final vote on the law was, and how the community reacted to the law.

Related Content

The Constitution

The Constitution was written in the summer of 1787 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by delegates from 12 states, in order to replace the Articles of Confederation with a new form of government. It created a federal system with a national government composed of 3 separated powers, and included both reserved and concurrent powers of states.

Bill of Rights: The 1st Ten Amendments

The first 10 amendments to the Constitution make up the Bill of Rights. James Madison wrote the amendments, which list specific prohibitions on governmental power, in response to calls from several states for greater constitutional protection for individual liberties.

McDonald v. Chicago | Homework Help from the Bill of Rights Institute

Does the Second Amendment prevent a city from effectively outlawing handgun ownership? In 2008, Otis McDonald attempted to purchase a handgun for self-defense purposes in a Chicago suburb. However, the city of Chicago had banned handgun ownership in 1982 when it passed a law that prevented issuing handgun registrations. McDonald argued this law violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges and Immunities Clause as well as the Due Process Clause. In a 5-4 decision, the Court ruled that McDonald’s Second Amendment right to bear arms was protected at the state and local level by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.5: Constructing a Persuasive Speech

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 17814

- Kris Barton & Barbara G. Tucker

- Florida State University & University of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

In a sense, constructing your persuasive speech is the culmination of the skills you have learned already. In another sense, you are challenged to think somewhat differently. While the steps of analyzing your audience, formulating your purpose and central idea, applying evidence, considering ethics, framing the ideas in appropriate language, and then practicing delivery will of course apply, you will need to consider some expanded options about each of these steps.

Formulating a Proposition

As mentioned before, when thinking about a central idea statement in a persuasive speech, we use the terms “proposition” or claim. Persuasive

speeches have one of four types of propositions or claims, which determine your overall approach. Before you move on, you need to determine what type of proposition you should have (based on the audience, context, issues involved in the topic, and assignment for the class).

Proposition of Fact

Speeches with this type of proposition attempt to establish the truth of a statement. The core of the propositoin (or claim) is not whether something is morally right and wrong or what should be done about the topic, only that a statement is supported by evidence or not. These propositions are not facts such as “the chemical symbol for water is H20” or “Barack Obama won the presidency in 2008 with 53% of the vote.” Propositions or claims of fact are statements over which persons disagree and there is evidence on both sides, although probably more on one than the other. Some examples of propositions of fact are:

Converting to solar energy can save homeowners money.

John F. Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald working alone.

Experiments using animals are essential to the development of many life-saving medical procedures.

Climate change has been caused by human activity.

Granting tuition tax credits to the parents of children who attend private schools will perpetuate educational inequality.

Watching violence on television causes violent behavior in children.

William Shakespeare did not write most of the plays attributed to him.

John Doe committed the crime of which he is accused.

Notice that in none of these are any values—good or bad—mentioned. Perpetuating segregation is not portrayed as good or bad, only as an effect of a policy. Of course, most people view educational inequality negatively, just as they view life-saving medical procedures positively. But the point of these propositions is to prove with evidence the truth of a statement, not its inherent value or what the audience should do about it. In fact, in some propositions of fact no action response would even be possible, such as the proposition listed above that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassination of President Kennedy.

Propositions of Definition

This is probably not one that you will use in your class, but it bears mentioning here because it is used in legal and scholarly arguments. Propositions of definitions argue that a word, phrase, or concept has a particular meaning. Remembering back to Chapter 7 on supporting materials, we saw that there are various ways to define words, such as by negation, operationalizing, and classification and division. It may be important for you to define your terms, especially if you have a value proposition. Lawyers, legislators, and scholars often write briefs, present speeches, or compose articles to define terms that are vital to defendants, citizens, or disciplines. We saw a proposition of definition defended in the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision to redefine marriage laws as applying to same-sex couples, based on arguments presented in court. Other examples might be:

The Second Amendment to the Constitution does not include possession of automatic weapons for private use.

Alcoholism should be considered a disease because…

The action committed by Mary Smith did not meet the standard for first-degree murder.

Thomas Jefferson’s definition of inalienable rights did not include a right to privacy.

In each of these examples, the proposition is that the definition of these things (the Second Amendment, alcoholism, crime, and inalienable rights) needs to be changed or viewed differently, but the audience is not asked to change an attitude or action.

Propositions of Value

It is likely that you or some of your classmates will give speeches with propositions of value. When the proposition has a word such as “good,” “bad,” “best,” “worst,” “just,” “unjust,” “ethical,” “unethical,” “moral,” “immoral,” “beneficial,” “harmful,” “advantageous,” or “disadvantageous,” it is a proposition of value. Some examples include:

Hybrid cars are the best form of automobile transportation available today.

Homeschooling is more beneficial for children than traditional schooling.

The War in Iraq was not justified.

Capital punishment is morally wrong.

Mascots that involve Native American names, characters, and symbols are demeaning.

A vegan diet is the healthiest one for adults.

Propositions of value require a first step: defining the “value” word. If a war is unjustified, what makes a war “just” or “justified” in the first place? That is a fairly philosophical question. What makes a form of transportation “best” or “better” than another? Isn’t that a matter of personal approach? For different people, “best” might mean “safest,” “least expensive,” “most environmentally responsible,” “stylish,” “powerful,” or “prestigious.” Obviously, in the case of the first proposition above, it means “environmentally responsible.” It would be the first job of the speaker, after introducing the speech and stating the proposition, to explain what “best form of automobile transportation” means. Then the proposition would be defended with separate arguments.

Propositions of Policy

These propositions are easy to identify because they almost always have the word “should” in them. These propositions call for a change in policy or practice (including those in a government, community, or school), or they can call for the audience to adopt a certain behavior. Speeches with propositions of policy can be those that call for passive acceptance and agreement from the audience and those that try to instigate the audience to action, to actually do something immediately or in the long-term.

Our state should require mandatory recertification of lawyers every ten years.

The federal government should act to ensure clean water standards for all citizens.

The federal government should not allow the use of technology to choose the sex of an unborn child.

The state of Georgia should require drivers over the age of 75 to take a vision test and present a certificate of good health from a doctor before renewing their licenses.

Wyeth Daniels should be the next governor of the state.

Young people should monitor their blood pressure regularly to avoid health problems later in life.

As mentioned before, the proposition determines the approach to the speech, especially the organization. Also as mentioned earlier in this chapter, the exact phrasing of the proposition should be carefully done to be reasonable, positive, and appropriate for the context and audience. In the next section we will examine organizational factors for speeches with propositions of fact, value, and policy.

Organization Based on Type of Proposition

Organization for a proposition of fact.

If your proposition is one of fact, you will do best to use a topical organization. Essentially that means that you will have two to four discrete, separate arguments in support of the proposition. For example:

Proposition: Converting to solar energy can save homeowners money.

I. Solar energy can be economical to install.

A. The government awards grants.

B. The government gives tax credits.

II. Solar energy reduces power bills.

III. Solar energy requires less money for maintenance.

IV. Solar energy works when the power grid goes down.

Here is a first draft of another outline for a proposition of fact:

Proposition: Experiments using animals are essential to the development of many life-saving medical procedures.

I. Research of the past shows many successes from animal experimentation.

II. Research on humans is limited for ethical and legal reasons.

III. Computer models for research have limitations.

However, these outlines are just preliminary drafts because preparing a speech of fact requires a great deal of research and understanding of the issues. A speech with a proposition of fact will almost always need an argument or section related to the “reservations,” refuting the arguments that the audience may be preparing in their minds, their mental dialogue. So the second example needs revision, such as:

I. The first argument in favor of animal experimentation is the record of successful discoveries from animal research.

II. A second reason to support animal experimentation is that research on humans is limited for ethical and legal reasons.

III. Animal experimentation is needed because computer models for research have limitations.

IV. Many people today have concerns about animal experimentation.

A. Some believe that all experimentation is equal.

1. There is experimentation for legitimate medical research.

2. There is experimentation for cosmetics or shampoos.

B. Others argue that the animals are mistreated.

1. There are protocols for the treatment of animals in experimentation.

2. Legitimate medical experimentation follows the protocols.

C. Some believe the persuasion of certain advocacy groups like PETA.

1. Many of the groups that protest animal experimentation have extreme views.

2. Some give untrue representations.

To complete this outline, along with introduction and conclusion, there would need to be quotations, statistics, and facts with sources provided to support both the pro-arguments in Main Points I-III and the refutation to the misconceptions about animal experimentation in Subpoints A-C under Point IV.

Organization for a proposition of value

A persuasive speech that incorporates a proposition of value will have a slightly different structure. As mentioned earlier, a proposition of value must first define the “value” word for clarity and provide a basis for the other arguments of the speech. The second or middle section would present the defense or “pro” arguments for the proposition based on the definition. The third section would include refutation of the counter arguments or “reservations.” The following outline draft shows a student trying to structure a speech with a value proposition. Keep in mind it is abbreviated for illustrative purposes, and thus incomplete as an example of what you would submit to your instructor, who will expect more detailed outlines for your speeches.

Proposition: Hybrid cars are the best form of automotive transportation available today.

I. Automotive transportation that is best meets three standards. (Definition)

A. It is reliable and durable.

B. It is fuel efficient and thus cost efficient.

C. It is therefore environmentally responsible.

II. Studies show that hybrid cars are durable and reliable. (Pro-Argument 1)

A. Hybrid cars have 99 problems per 100 cars versus 133 problem per 100 conventional cars, according to TrueDelta, a car analysis website much like Consumer Reports.

B. J.D. Powers reports hybrids also experience 11 fewer engine and transmission issues than gas-powered vehicles, per 100 vehicles.

III. Hybrid cars are fuel-efficient. (Pro-Argument 2)

A. The Toyota Prius gets 48 mpg on the highway and 51 mpg in the city.

B. The Ford Fusion hybrid gets 47 mpg in the city and in the country.

IV. Hybrid cars are environmentally responsible. (Pro-Argument 3)

A. They only emit 51.6 gallons of carbon dioxide every 100 miles.

B. Conventional cars emit 74.9 gallons of carbon dioxide every 100 miles.

C. The hybrid produces 69% of the harmful gas exhaust that a conventional car does.

V. Of course, hybrid cars are relatively new to the market and some have questions about them. (Reservations)

A. Don’t the batteries wear out and aren’t they expensive to replace?

1. Evidence to address this misconception.

2. Evidence to address this misconception.

B. Aren’t hybrid cars only good for certain types of driving and drivers?

C. Aren’t electric cars better?

Organization for a propositions of policy

The most common type of outline organizations for speeches with propositions of policy is problem-solution or problem-cause-solution. Typically we do not feel any motivation to change unless we are convinced that some harm, problem, need, or deficiency exists, and even more, that it affects us personally. As the saying goes, “If it ain’t broke, why fix it?”As mentioned before, some policy speeches look for passive agreement or acceptance of the proposition. Some instructors call this type of policy speech a “think” speech since the persuasion is just about changing the way your audience thinks about a policy.

On the other hand, other policy speeches seek to move the audience to do something to change a situation or to get involved in a cause, and these are sometimes called a “do” speech since the audience is asked to do something. This second type of policy speech (the “do” speech) is sometimes called a “speech to actuate.” Although a simple problem-solution organization with only two main points is permissible for a speech of actuation, you will probably do well to utilize the more detailed format called Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

This format, designed by Alan Monroe (1951), who wrote a popular speaking textbook for many years, is based on John Dewey’s reflective thinking process. It seeks to go in-depth with the many questions an audience would have in the process of listening to a persuasive speech. Monroe’s Motivated Sequence involves five steps, which should not be confused with the main points of the outline. Some steps in Monroe’s Motivated Sequence may take two points.

- Attention . This is the introduction, where the speaker brings attention to the importance of the topic as well as his or her own credibility and connection to the topic. This step will include the thesis and preview.

- Need . Here the problem is defined and defended. This step may be divided into two main points, such as the problem and the causes of it, since logically a solution should address the underlying causes as well as the external effects of a problem. It is important to make the audience see the severity of the problem, and how it affects them, their family, or their community. The harm or need can be physical, financial, psychological, legal, emotional, educational, social, or a combination. It will have to be supported by evidence.

- Satisfaction . A need calls for satisfaction in the same way a problem requires a solution. This step could also, in some cases, take up two main points. Not only does the speaker present the solution and describe it, but they must also defend that it works and will address the causes of the problem as well as the symptoms.

- Visualization . This step looks to the future either positively or negatively. If positive, the benefits from enacting or choosing the solution are shown. If negative, the disadvantages of not doing anything to solve the problem are shown. There may be times when it is acceptable to skip this step, especially if time is limited. The purpose of visualization is to motivate the audience by revealing future benefits or through fear appeals by showing future harms.

- Action . This can be the conclusion, although if the speaker really wants to spend time on moving the audience to action, the action step should be a full main point and the conclusion saved for summary and a dramatic ending. In the action step, the goal is to give specific steps for the audience to take as soon as possible to move toward solving the problem. Whereas the satisfaction step explains the solution overall, the action step gives concrete ways to begin making the solution happen.