Please enter at least 3 characters

World War II Propaganda Posters

Created by everyone from Norman Rockwell to the Stetson Hat Company, World War II propaganda posters played a crucial role in motivating Americans.

This article appears in: October 2002

By Eric H. Roth

Military posters played a crucial role in motivating Americans to do their best and make sacrifices—of all kinds—during World War II. The War Department, Red Cross, General Electric, Stetson Hat Company, and dozens of other organizations created thousands of patriotic posters to mobilize public support. Poignant, colorful images on paper were created and distributed to

build support for avenging Pearl Harbor, protecting American families, selling war bonds, conserving fuel, increasing factory production, promoting democratic ideals, growing vegetables, expanding the workforce, and keeping secrets.

The propaganda war, before television and the Internet, looked—and maybe worked—best on posters. Wartime posters, often printed in runs of 10,000, were designed to be used once, understood in 20 seconds, displayed for a few months, and thrown away. The few remaining posters, often created by skilled artists and illustrators, have become historical artifacts. Museums, scholars, collectors, veterans—and, increasingly, baby boomers—are celebrating these wartime images for their sociological, aesthetic, and historical value. World War II posters have become hot commodities and very collectible items.

“The Posters That Won the War,” a cyber exhibition at www. posterny. com by the Chisholm-Larsson Gallery, tells the story and highlights 50 original WWII posters: “The production, recruiting, and War Bond posters of WWII were ‘America’s weapons on the wall.’ Millions of posters of hundreds of unique designs cascaded off the presses and onto the American landscape, raising hopes in the dark days after Pearl Harbor and convincing folks on the homefront that their efforts were the key to victory. Today, the relatively few posters that remain are a colorful, nostalgic, and highly collectible snapshot of America at war.”

Robert Chisholm, the owner of Chisholm-Larsson Gallery in New York City, counts 627 different original WWII posters in his collection of 24,000-plus posters. “Whatever your budget, you can find a WWII poster,” says Chisholm. “Ninety percent are $400 or less.”

The gold standard for collectors’ WWII vintage posters, however, remains the Meehan Military Posters catalog. “The only organization in the world,” according to the company’s literature, “devoted to providing original, vintage posters of the two World Wars and Spanish Civil War to collectors, museums, decorators, and investors.” Meehan Military Posters divides WWII posters into nine distinct categories: pilots/planes, recruitment, conservation, espionage, nurses, foreign aid, war production, morale, and foreign on its searchable Web site.

Each color catalog, published twice a year, contains thumbnail-sized reproductions of hundreds of original military posters from “nearly all combatants in both World Wars.” A concise description gives the background of each poster, noting the artist, year of publication, size, condition, and price. The catalog costs $15, but many collectors and dealers consider it an essential investment. “His prices are very good, very fair,” observes a West Coast competitor, Burt Blum, owner of the Trading Post in Santa Monica and a lifelong dealer in vintage magazines and posters.

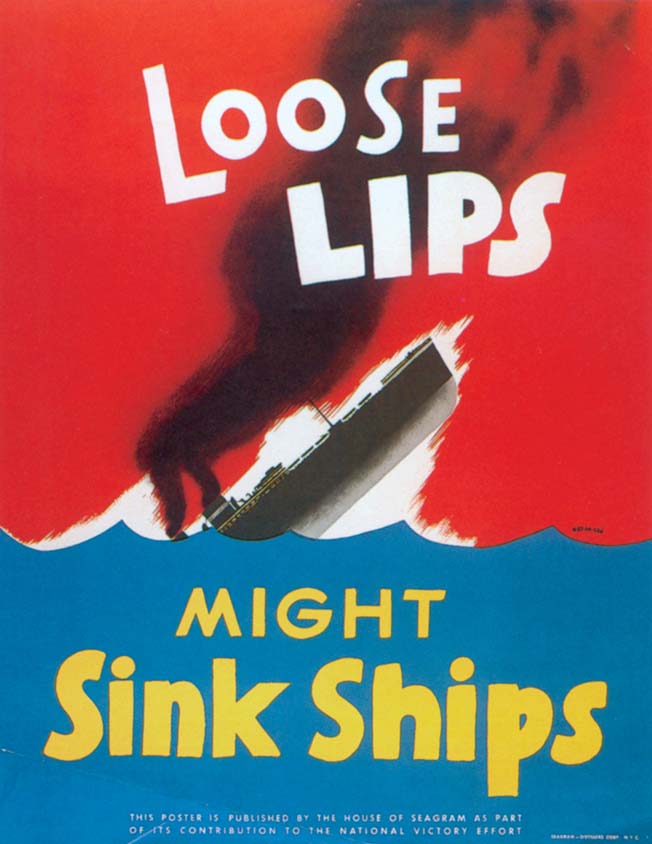

Fair should not be confused with cheap. “Today an expensive WWII poster can command as much as $4,000 or $5,000,” declares Meehan. “A German poster designed and drawn by the great German poster artist Ludwig Hohlwein could easily be in that range.” Meehan Catalog #36 features many rare, expensive, and fascinating posters. A pair designed by Melbourne Brindle graces the front and back covers. The first haunting image shows a sinking ship, printed by Stetson Hat Company. It warns: “Loose Talk Can Cost Lives! … Keep it under your STETSON.” The second dramatic poster of a sunken Merchant Marine ship beneath a German U-Boat, with the words “Careless talk did this … Keep it under Your Stetson,” sells for $2,750.

The pricey Stetson poster illuminates a common theme of many World War II posters: the dangers of espionage and careless talk. “Silence—means security. Be careful what you say or write,” by illustrator Jes Wilhelm Schlaikjer in 1945 shows a night-patrol infantryman walking somewhere in the Pacific. Meehan sells it for $325. Other military posters, more available and by less well-known artists, such as the 1943 “This Man May Die If You Talk Too Much,” featuring a handsome sailor looking through a porthole, and the 1944 “We Caught Hell!—someone must have talked” sell for $145 in the poster catalog. These poignant posters place clear responsibility for the safety of sailors and soldiers on the silence of civilians and fellow servicemen.

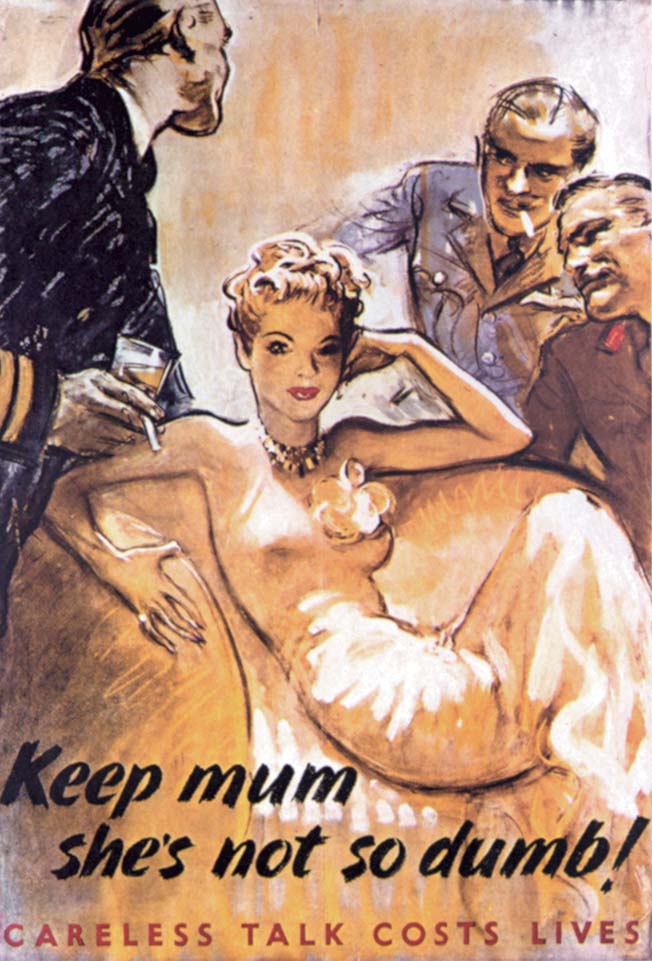

Almost the entire “Loose lips sink ships” poster series has become quite collectible. An excellent example, according to veteran poster dealer Gail Chisholm (Robert’s sister, neighbor, and friendly rival poster gallery owner), shows a hissing snake surrounded by the words “Less Dangerous Than Careless Talk”—she sells it for $330. The easy-to-use Chisholm Gallery Web site includes a wide selection of World War II posters. “There are also a lot of great and amusing posters against careless talk,” such as “Keep Mum, She’s Not So Dumb,” observes Robert Chisholm.

“Powers of Persuasion: Poster Art of World War II,” a popular exhibit at the National Archives Building in Washington DC from May 1994 to February 1995, emphasized the two psychological approaches used to motivate Americans: pride and fear. “Words are ammunition,” said a Government Information Manual issued by the Office of War Information in the exhibit. “Each word an American utters either helps or hurts the war effort. He must stop rumors. He must challenge the cynic and the appeaser. He must not speak recklessly. He must remember that the enemy is listening.” An online exhibit culled from the museum show features 33 posters, one sound file, and some background historical information.

Across the country at an outdoor flea market in Santa Monica, dealer Garrison Dover has found WWII military posters to be a hot topic. “When I get WWII posters, they tend to move fast,” said Dover, the owner of Pacific Posters International. “Sometimes a guy will ask if we have any WWII posters. You show him two or three, and he buys them all. Somebody who collects WWII posters will buy anything in stock … under the right circumstances.”

Price might be one of those circumstances. “Wartime posters go for $20 to $2,000,” continues Dover, with most posters going for around $200. “Anything selling for more than $2,000 is a one of a kind.” The significant price tag for those two Stetson Hat posters also reflects a general principle in collecting—the more unusual the item, the higher the price. “Most posters were government issues, but there are some from General Electric, General Motors, and other companies,” notes Robert Chisholm. “They are more collectible because they had a smaller circulation.”

“We are currently advertising posters printed in a series for the Kroger Baking Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, which they placed in their grocery store windows during the war,” says Meehan. “They are now selling for several thousand dollars each. Privately printed posters like these had very small print runs compared to government posters.” Yet some dealers consider it a mistake to confuse the initial print run with the number of surviving copies.

“People always want to know how many posters were printed, and you don’t know,” confesses Gail Chisholm. “The number printed has nothing to do with the number surviving. It wasn’t a successful (advertising) campaign if it wasn’t on the street.” Location can also be a factor in the perception of rarity and poster prices. Dover sells original vintage posters at antique malls, flea markets, and vintage poster shows, and only opens his Santa Barbara gallery for private appointments. His web site also leads to some sales.

Sometimes rarity and historical importance are not the most critical factors. Occasionally even relatively rare posters can be bought for under $250—especially if the image is something that few people would want to look at in their home. A somber 1942 poster of a dead sailor in the surf above the words “A Careless Word … A Needless Loss” is listed for $235 in the Meehan Military Posters Catalog #36.

A few posters have become celebrated American icons. James Montgomery Flagg’s 1941 version of Uncle Sam pointing, with the caption “I Want You for the U.S. Army,” consistently sells for well over $1,000. The Meehan Catalog lists the price as $1,500. This classic WWII poster, based on the infamous World War I poster, deliberately evokes the patriotic imagery from the “war to end all wars.”

Most WWII posters, however, look quite different from WWI propaganda posters. “WWI posters were primarily designed by illustrators who volunteered their efforts,” says Sarah Stocking, president of the Independent Vintage Poster Dealers Association and owner of Sarah Stocking Fine Vintage Posters. “They mostly appeal to patriotism.” Stocking specializes in commercial European posters from the 1920s and 1930s.

Gail Chisholm makes a related point. “World War I posters are from a more innocent and naive society,” she says. “Obviously, it’s called the Great War. It was enough to have a pretty woman with a furling flag to convince young men to enlist and risk their lives.”

“Perhaps more importantly,” concludes Stocking, “WWI posters are not brutal.” Stocking carries posters on WWI, WWII, the Spanish Civil War, and propaganda. She “prefers” WWI posters because there is less text.

By contrast, American posters from WWII were often realistic, intense, and evocative of both positive and negative emotions.

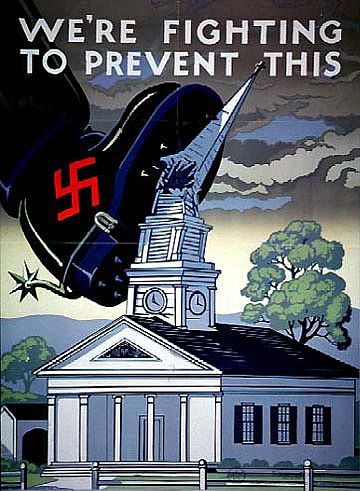

“WWII posters were often made about fear and the enemy,” says Stocking. “The world had really changed in 20 years, and had gotten smaller because the government was worried about spying.” Radio broadcasts, airplanes, and increased tourism brought Europe “closer” to the United States. “World War II posters are much more aggressive,” concurs Gail Chisholm. The widely distributed poster showing a bomb, labeled “War Production,” targeted at the Rising Sun and Nazi swastika is an example. “Some also have ugly caricatures of Japanese and Germans—but especially Japanese.” Institutional collectors tend to be the major purchasers of the more controversial and/or foreign posters. American propaganda posters, however, appear politically correct in comparison to the vicious images in Axis propaganda posters. “I have a phenomenal Italian one—even away from the perspective of the war,” says Gail Chisholm. “It has an ugly, leering, black American soldier pulling down a Venus De Milo sculpture.” The harsh image, designed to inflame Italian fears about an American invasion, emphasizes racial hatreds. “Some patrons have gotten very upset by the image,” she says. She considers the disturbing image “a peek into history.” The controversial Italian poster, designed by Gino Boccasile in 1944, brings up another aspect of collecting historical posters. “Taking things out of context changes your perception,” observes Gail Chisholm. “You can have different interpretations. At the time, everybody understood a poster’s context, but now it is less clear.”

A few American posters, among the most sought after by institutional collectors, attempted to build relations between racial groups. A widely distributed poster, “United We Win,” shows steelworkers, a black man and a white man, working together under a giant American flag. “Those posters tend to be quite valuable,” says Gail Chisholm.

Patriotic imagery pervades many WWII posters and draws upon the nation’s rich heritage of patriotic symbols. “Americans Will Always Fight for Freedom,” by George Perlin, shows “America’s well-equipped infantry troops of 1943 passing in review in front of the ragged Continental troops of Valley Forge who also fought for freedom during the bleak and desperate winter of 1777-1778 some 166 years earlier,” explains Meehan. Price? $385. “Perhaps what made the American posters of World War II unique was that they equated patriotism with democracy,” wrote scholar G.H. Gregory, editor and compiler of the book, Posters of World War II. “They rallied the nation’s pride by recalling the marvel of the country’s institutions and its great tradition of freedom and democracy—its flag, its enduring documents, its national monuments, its political heroes, its historic heritage of fighting for liberty.”

The condition of vintage posters, like most collectibles, also affects value. Almost all WWII posters were sent by mail. Says Gail Chisholm, “WWII posters have folds. It goes with the territory. Small irregularities are expected. A missing corner doesn’t really matter, but a hand missing is more problematic.”

What else adds value to a particular WWII image? Beyond rarity, condition, and subject matter, vintage poster experts emphasize the importance of the artist and artwork. The illustrator’s name and reputation certainly affect the price. Artists Norman Rockwell, Ben Shahn, Jes Wilhelm Schlaikjer, James Montgomery Flagg, Arthur Szyk, and N.C. Wyeth all contributed their skills, creativity, and intelligence to the war effort. Their wartime propaganda efforts are now collectible items. Some popular artists’ works continue to dominate sales. Rockwell remains the most famous American artist to create wartime posters. The great Saturday Evening Post illustrator’s “Four Freedoms” paintings, inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address, were made into immensely popular posters during the war to sell war bonds and inspire patriotism. The most valuable poster, Rockwell’s 1943 “Freedom from Want,” showing three generations of a family eating a Thanksgiving meal, sells for $400 to $750. The other posters in the freedom series, “Freedom of Speech,” “Freedom of Worship,” and “Freedom from Fear” are slightly less expensive.

Schlaikjer, a Danish-born illustrator, developed a reputation for effective, inspiring posters. He created powerful recruitment posters for the U.S. War Department that feature heroic, handsome figures in dramatic poses in combat situations. A refugee from Denmark in 1940, Schlaikjer became America’s “official war artist” from 1942 to 1944. His 1942 recruitment posters for the Military Police, the Signal Corps, the Army Air Corps, Women’s Air Corps, and the Corps of Engineers sell for between $500 and $1,250.

Arthur Szyk, a Polish-born immigrant, also has loyal collectors. Szyk drew patriotic posters for U.S. Treasury war bonds, designed wartime postage stamps, and had his posters displayed by the USO at five hundred U.S. Army recreation centers. Szyk’s provocative caricatures, mocking cartoons, and biting satirical illustrations filled the magazine covers of Collier’s, Esquire, and Time. The U.S. Holocaust Museum is hosting an exhibit called “ The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk “, until October 14, 2002.

Despite the near-universal recognition of his Uncle Sam “I Want You” poster, Flagg never really achieved the celebrity status that would guarantee top dollars. For example, Flagg created a few other World War II images, including a hatless, grim-faced Uncle Sam providing consumer advice: “You Can Lick Runaway Prices” by buying war bonds and paying taxes willingly. This Flagg poster sells for under $200.

The iconic Rosie the Riveter posters, which are practically impossible to buy these days, represent another common theme in WWII: the patriotic duties of women. These posters, sometimes exhorting women to join the workplace, have dramatically increased in value over the past 20 years. These “women do your part” posters have sociological significance that resonates with many contemporary consumers.

The U.S. Army Nurse Corps recruitment posters are equally distinctive, with photographs of wounded soldiers and concise testimonials. The kicker reads in large block letters: MORE NURSES ARE NEEDED—U.S. ARMY NURSE CORPS. “Sometimes people come in and say ‘I want such and such poster. My mom was the model,’” says Gail Chisholm. “‘Or my mom was a WAC.’ That’s always exciting.”

Many WWII posters told civilian Americans to sacrifice in everyday activities—save tin cans, recycle paper, eat leftovers, grow vegetables, drive less to save gasoline and rubber, and even conserve waste fats. “Food conservation posters are also popular,” says Stocking. “The themes are also timeless. ‘Grow Your Vegetables’ can go in anyone’s kitchen.” Conservation posters often made a direct link to the military effort. “Can All You Can—It’s a Real War Job” placed a jar against colorful vegetables. Another poster featured a smiling woman carrying a load of food, proclaiming, “Of Course I Can! I’m as patriotic as can be—and rationing won’t worry me.” “Do with less—so they’ll have enough!” urged another poster featuring a smiling soldier in a helmet sipping coffee.

War bond posters remain probably the most affordable, diverse, and prevalent type on the market today. “It’s much easier to find a war bond poster,” says Robert Chisholm. “Giving money is easier than actually signing up and joining the military,” Stocking adds.

“Recruiting posters printed in America are rarer than war bond ones.” Some collectors, often veterans, focus on one service. Haddon H. Sundblom’s pithy recruitment poster, “Ready—Join U.S. Marines,” showcases a marine officer with movie-star good looks. “Marines have been so gung-ho and enthusiastic,” says Robert Chisholm. “Once a Marine, always a Marine.”

“Marine recruiting posters are certainly the most heavily collected American recruiting posters of all,” says Meehan. “The Marines are an elite, all-volunteer force whose members are typically proud of their service and enjoy reminding themselves and others of it.”

All the dealers emphasize the importance of taking proper care of posters. Some tips include: never do anything to paper that can’t be undone (no permanent adhesion, no Scotch tape, no masking tape, no dry mounting); use archival linen backing with water soluble glue; use acid-free paper; keep them out of the sunlight; and “treat them as an investment.” The relative fragility of paper, ironically, makes posters increasingly collectible. “People are becoming more aware of posters’ rarity and value,” says Robert Chisholm. “But don’t buy a poster as an investment. Buy it for visual, historical, or aesthetic reasons—and usually it will increase in value.” His sibling, Gail, agrees. “Buy because you love it and it appeals to you. It’s a nice bonus if the poster goes up in value.”

“Prices have gone way up,” says Dover. “It used to be that nobody much appreciated WWII posters. Ten, 15, 20 years ago, most people just weren’t interested” unless it was of a national icon (Rosie the Riveter) or by a national icon (Rockwell). These days Dover credits the longing for national unity for the posters’ appreciation. “Do you remember that feeling after 9/11?” he asks. “We all felt we were Americans and in it together. The posters of WWII are a reflection of when America pulled together like never before.”

Eric Roth has written about media, history, and public education for several publications. He currently teaches English at Santa Monica College and UCLA Extension.

Back to the issue this appears in

Join The Conversation

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share This Article

- via= " class="share-btn twitter">

Related Articles

World’s First Smart Weapon: the ‘Bat’

Airborne! Learning to Fly and Land—Hard

Bravery in Embattled Bastogne

John Parks: The Face of Battle

From around the network.

Military Games

Wars and Battles

The American “Few”

WWII Vehicles: The British Universal (or “Bren Gun”) Carrier

Saipan: A Crucial Foothold in the Marianas

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

These World War II Propaganda Posters Rallied the Home Front

By: Madison Horne

Updated: August 10, 2023 | Original: October 12, 2018

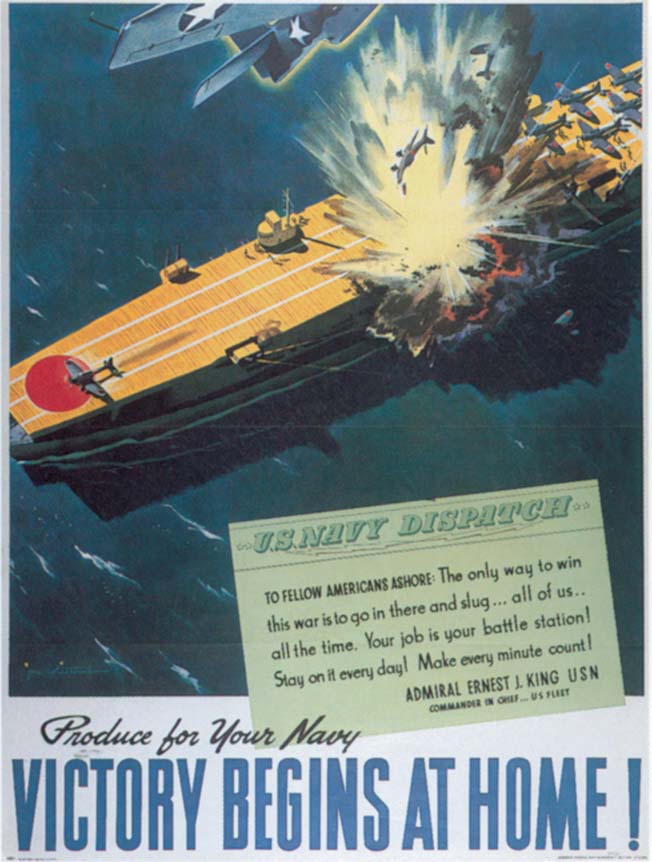

When Britain and France went to war with Germany in 1939, Americans were divided over whether to join the war effort. It wouldn't be until the surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 that the United States would be thrust into World War II . Once U.S. troops were sent to the front lines, hundreds of artists were put to work to create posters that would rally support on the home front .

Citizens were invited to purchase war bonds and take on factory jobs to support production needs for the military. As men were sent to battlefields, women were asked to branch out and take on jobs as riveters, welders and electricians.

To preserve resources for the war effort, posters championed carpooling to save on gas, warned against wasting food and urged people to collect scrap metal to recycle into military materials. In the spring of 1942, rationing programs were implemented that set limits on everyday purchases.

While many posters touted positive patriotic messages, some tapped fear to rally support for the Allied side and caution against leaking information to spies. "Loose lips sink ships" became a famous saying. Meanwhile, graphic images depicted a blood-thirsty Adolph Hitler and racist imagery of Japanese people with sinister, exaggerated features.

Today, the posters a offer a glimpse into the nation's climate during World War II and how propaganda was used to link the home front to the front lines.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Educator Resources

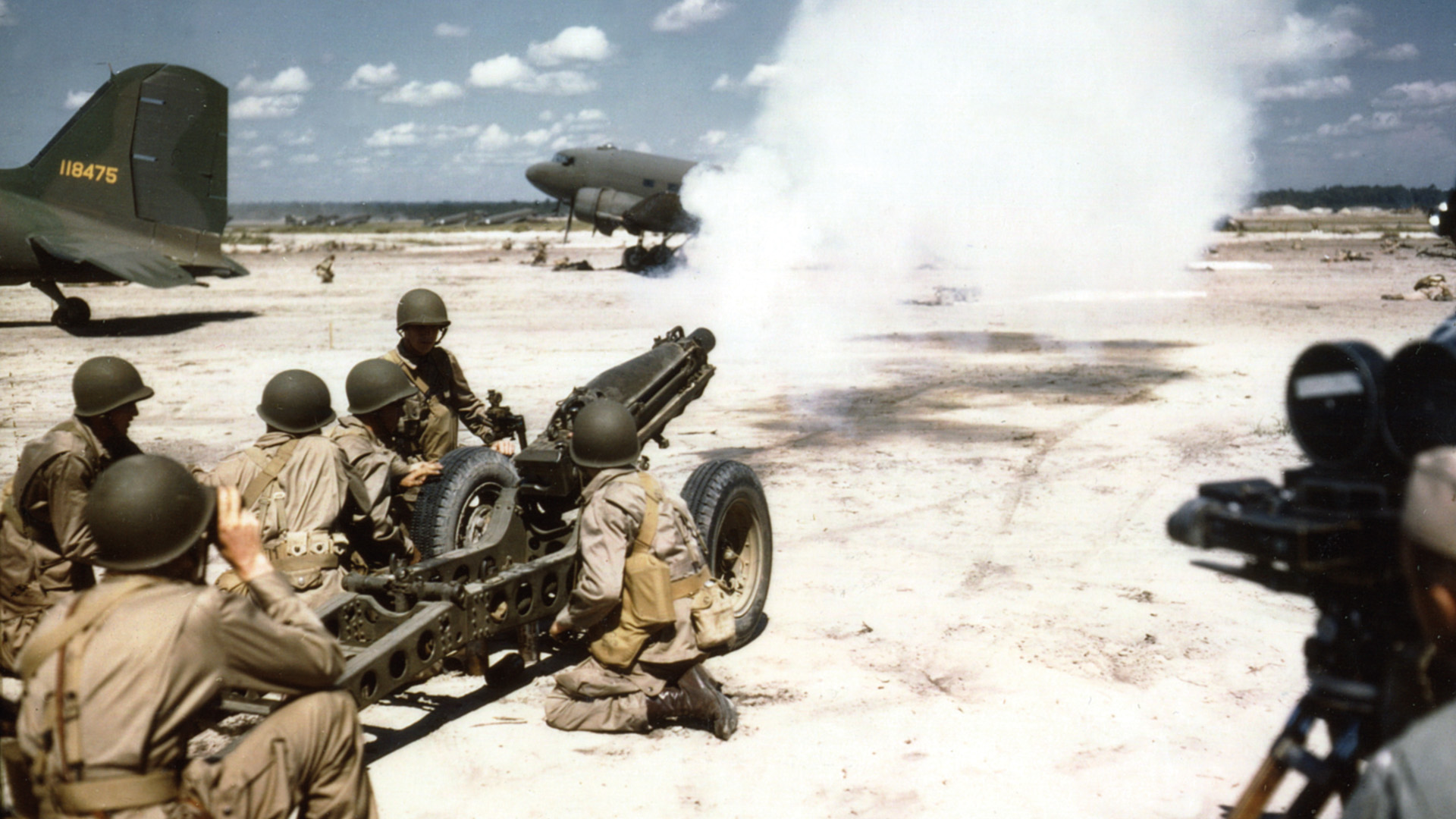

Powers of Persuasion - Poster Art of World War II

Guns, tanks, and bombs were the principal weapons of World War II, but there were other, more subtle, forms of warfare as well. Words, posters, and films waged a constant battle for the hearts and minds of the American citizenry just as surely as military weapons engaged the enemy. Persuading the American public became a wartime industry, almost as important as the manufacturing of bullets and planes. The Government launched an aggressive propaganda campaign to galvanize public support, and some of the nation's foremost intellectuals, artists, and film makers became warriors on that front.

Time required:

One to two class periods

To analyze poster art of World War II.

The Documents

Posters from the Powers of Persuasion exhibit in the Online Exhibit Hall

Log In | Register

- Plan A Visit

- The Arsenal of Democracy

- Live Shows at BB's Stage Door Canteen

- Dining — The American Sector and Soda Shop

- Museum Campus

- Beyond All Boundaries

- Give to the Museum

- Capital Expansion

- Become A Member

- Name A Theater Seat

- Planned Giving

- Donate A Vehicle

- Donate An Artifact

- Corporate Sponsorships

- Donor Privacy Policy

- Honor Roll of Charter Members

- Brick Program

- Personal Tribute Pages

- Tribute Gifts

- $10 for Them

- Research A Veteran

- WWII Veteran Statistics

- Teachers & Students

- Public Programming

- Educational Travel

- Knit Your Bit

- Educational WWII Wargaming

- International Conference on WWII

- Speakers Bureau

- Family Activities

- Museum Blog

- Digital Collections

- WWII Yearbooks

- The Science & Technology of WWII

- The Classroom Victory Garden Project

- Kids Corner

- Past Speakers Archive

- Campaigns of Courage

- Liberation Pavilion

- Capital Campaign Donors

PROPAGANDA POSTERS AT A GLANCE:

- For Students

- World War II History

- Research Starters

- Oral History Guidelines

- Get Involved

- Student Contests

- Education Blog

- National History Day

Image Gallery

Uncle sam wants you the propaganda posters of wwii.

When you think of the weapons of WWII, what comes to mind? Planes, tanks, money? Bullets, machine-guns, and grenade launchers? Yes, all of these were important tools in the effort to win the war. But so was information. In this case, government issued information. Over the course of the war the U.S. government waged a constant battle for the hearts and minds of the public. Persuading Americans to support the war effort became a wartime industry, just as important as producing bullets and planes. The U.S. government produced posters, pamphlets, newsreels, radio shows, and movies-all designed to create a public that was 100% behind the war effort.

In 1942 the Office of War Information (OWI) was created to both craft and disseminate the government’s message. This propaganda campaign included specific goals and strategies. Artists, filmmakers, and intellectuals were recruited to take the government’s agenda (objectives) and turn it into a propaganda campaign. This included posters found across American-from railway stations to post offices, from schools to apartment buildings.

During WWII the objectives of the U.S. government for the propaganda campaign were recruitment, financing the war effort, unifying the public behind the war effort and eliminating dissent of all kinds, resource conservation, and factory production of war materials. The most common themes found in the posters were the consequences of careless talk, conservation, civil defense, war bonds, victory gardens, “women power”, and anti-German and Japanese scenarios. It was imperative to have the American people behind the war effort. Victory over the Axis was not a given, and certainly would not be without the whole-hearted support of all men, women, and children.

To meet the government’s objectives the OWI (Office of War Information) used common propaganda tools (posters, radio, movies, etc.) and specific types of propaganda. The most common types used were fear, the bandwagon, name-calling, euphemism, glittering generalities, transfer, and the testimonial.

The posters pulled at emotions-both positive and negative. They used words as ammunition. “When you ride alone, you ride with Hitler.” “Loose lips might sink ships.” Messages made the war personal-you can make a difference, the soldiers are counting on you. Some posters also tapped into people’s patriotic spirit-do this and be a good American. They were bright and happy, colorful and positive. Other posters showed the dark side of war. They were filled with shocking images of what had happened to other countries and what could still happen in America if everyone did not do their part.

“The principal battleground of the war is not the South Pacific. It is not the Middle East. It is not England, or Norway, or the Russian Steppes. It is American opinion.”

--Archibald MacLeish, Director of the Office of Facts and Figures, forerunner of the Office of War Administration

“The function of the war poster is to make coherent and acceptable a basically incoherent and irrational ordeal of killing, suffering, and destruction that violate every accepted principle of morality and decent living.”

--O.W. Riegal, propaganda analyst for the Office of War Information

Download a printable version of this At A Glance

Back to WWII at a Glance

TAKE ACTION:

Education projects:.

- ABOUT THE MUSEUM

- SPECIAL EVENTS

- PRIVACY POLICY

The National WWII Museum tells the story of the American Experience in the war that changed the world - why it was fought, how it was won, and what it means today - so that all generations will understand the price of freedom and be inspired by what they learn.

Sign up for updates about exhibits, public programming and other news from The National WWII Museum here.

945 Magazine Street New Orleans, LA 70130, Entrance on Andrew Higgins Drive PHONE: (504) 528-1944 - FAX: (504) 527-6088 - EMAIL: [email protected] | Directions

Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? Analyzing World War II Posters

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

In this lesson plan, students analyze World War II posters, chosen from online collections, to explore how argument, persuasion and propaganda differ. The lesson begins with a full-class exploration of the famous "I WANT YOU FOR U.S. ARMY" poster, wherein students explore the similarities and differences between argument, persuasion, and propaganda and apply one of the genres to the poster. Students then work independently to complete an online analysis of another poster and submit either an analysis worksheet or use their worksheet responses to write a more formal essay.

Featured Resources

- Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? : This handout clarifies the goals, techniques, and methods used in the genres of argument, persuasion, and propaganda.

- Analyzing a World War II Poster : This interactive assists students in careful analysis of a World War II poster of their own selection for its use of argument, persuasion, or propaganda.

From Theory to Practice

Visual texts are the focus of this lesson, which combines more traditional document analysis questions with an exploration of World War II posters. The 1975 "Resolution on Promoting Media Literacy" states that explorations of such multimodal messages "enable students to deal constructively with complex new modes of delivering information, new multisensory tactics for persuasion, and new technology-based art forms." The 2003 "Resolution on Composing with Nonprint Media" reminds us that "Today our students are living in a world that is increasingly non-printcentric. New media such as the Internet, MP3 files, and video are transforming the communication experiences of young people outside of school. Young people are composing in nonprint media that can include any combination of visual art, motion (video and film), graphics, text, and sound-all of which are frequently written and read in nonlinear fashion." To support the literacy skills that students must sharpen to navigate these many media, activities such as the poster analysis in this lesson plan provide bridging opportunities between traditional understandings of genre and visual representations. Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

- Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda?

- Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda

- Poster Analysis Rubric

Preparation

- Make appropriate copies of Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? , Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda , and Poster Analysis Rubric .

- Explore the background information on the Uncle Sam recruiting poster , so that you are prepared to share relevant historical details about the poster with students.

- If desired, explore the online poster collections and choose a specific poster or posters for students to analyze. If you choose to limit the options, post the choices on the board or on white paper for students to refer to in Session Two .

- Decide what final product students will submit for this lesson. Students can submit their analysis printout from the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive, or they can write essays that explain their analysis. If students write essays, the printouts from the interactive serve as prewriting and preparation for the longer, more formal piece.

- Test the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive and the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive on your computers to familiarize yourself with the tools and ensure that you have the Flash plug-in installed. You can download the plug-in from the technical support page.

Student Objectives

Students will

- discuss the differences between argument, persuasion, and propaganda.

- analyze visual texts individually, in small groups, and as a whole class.

- (optionally) write an analytical essay.

Session One

- Display the Uncle Sam recruiting poster using an overhead projector.

- Ask students to share what they know about the poster, noting their responses on the board or on chart paper.

- If students have not volunteered the information, provide some basic background information .

- Working in small groups, have students use the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive to analyze the Uncle Sam poster.

- Emphasize that students should use complete, clear sentences in their responses. The printout that the interactive creates will not include the questions, so students responses must provide the context. Be sure to connect the requirement for complete sentences to the reason for the requirement (so that students will understand the information on the printout without having to return to the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive.

- As students work, encourage them to look for concrete details in the poster that support their statements.

- Circulate among students as they work, providing support and feedback.

- Once students have completed the questions included in the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive, display the poster again and ask students to share their observations and analyses.

- Emphasize and support responses that will tie to the next session, where students will complete an independent analysis.

- Pass out and go over copies of the Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda Chart .

- Ask students to apply genre descriptions to the Uncle Sam poster, using the basic details they gathered in their analysis to identify the poster's genre.

Session Two

- Review the Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? chart.

- Elicit examples of argument, persuasion, and propaganda from the students, asking them to provide supporting details that confirm the genres of the examples. Provide time for students to explore some of the Websites in the Resources section to explore the three concepts.

- When you feel that the students are comfortable with the similarities and differences of the three genres, explain to the class that they are going to be choosing and analyzing World War II posters for a more detailed analysis.

- Pass out the Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda , and go over the questions in the analysis sheet. Draw connections between the questions and what the related answers will reveal about a document's genre.

- Demonstrate the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive.

- Point out the connections between the questions in the interactive and the questions listed on the Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda .

- If students need additional practice with analysis, choose a poster and use the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive to work through all the analysis questions as a whole class.

- Explain the final format that students will use for their analysis—you can have students submit their analysis printout from the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive, or they can submit polished essays that explain their analysis.

- Pass out copies of the Poster Analysis Rubric , and explain the expectations for the project.

- Posters on the American Home Front (1941-45), from the Smithsonian Institute

- Powers of Persuasion, from the National Archives

- World War II Poster Collection, from Northwestern University

- World War II Posters, from University of North Texas Libraries

Session Three

- Review the poster analysis project and the handouts from previous session.

- Answer any questions about the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive then give students the entire class session to work through their analysis.

- Remind students to refer to the Poster Analysis Rubric to check their work before saving or printing their work.

- If you are having students submit their printouts for the final project, collect their work at the end of the session. Otherwise, if you have asked students to write the essay, ask them to use their printout to write the essay for homework. Collect the essays and printouts at the beginning of the next session (or when desired).

- If desired, students might share the posters they have chosen and their conclusions with the whole class or in small groups.

The Propaganda Techniques in Literature and Online Political Ads lesson plan offers additional information about propaganda as well as some good Websites on propaganda.

Student Assessment / Reflections

Use the Poster Analysis Rubric to evaluate and give feedback on students’ work. If students have written a more formal paper, you might provide additional guidelines for standard written essays, as typically used in your class.

- Calendar Activities

- Professional Library

- Strategy Guides

- Lesson Plans

This resolution discusses that understanding the new media and using them constructively and creatively actually requires developing a new form of literacy and new critical abilities "in reading, listening, viewing, and thinking."

This strategy guide clarifies the difference between persuasion and argumentation, stressing the connection between close reading of text to gather evidence and formation of a strong argumentative claim about text.

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

- University Archives

- Special Collections

- Records Management

- Policies and Forms

- Sound Recordings

- Theses and Dissertations

- Selections From Our Digitized Collections

- Videos from the Archives

- Special Collections Exhibits

- University Archives Exhibits

- Research Guides

- Current Exhibits

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Past Exhibits

- Camelot Comes to Brandeis

- Special Collections Spotlight

- Library Home

- Degree Programs

- Majors and Minors

- Graduate Programs

- The Brandeis Core

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Brandeis Online

- Brandeis International Business School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Heller School for Social Policy and Management

- Rabb School of Continuing Studies

- Precollege Programs

- Faculty and Researcher Directory

- Brandeis Library

- Academic Calendar

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Summer School

- Financial Aid

- Research that Matters

- Resources for Researchers

- Brandeis Researchers in the News

- Provost Research Grants

- Recent Awards

- Faculty Research

- Student Research

- Centers and Institutes

- Office of the Vice Provost for Research

- Office of the Provost

- Housing/Community Living

- Campus Calendar

- Student Engagement

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Dean of Students Office

- Orientation

- Hiatt Career Center

- Spiritual Life

- Graduate Student Affairs

- Directory of Campus Contacts

- Division of Creative Arts

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts

- Theater Arts Productions

- Brandeis Concert Series

- Public Sculpture at Brandeis

- Women's Studies Research Center

- Creative Arts Award

- Our Jewish Roots

- The Framework for the Future

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Distinguished Faculty

- Nobel Prize 2017

- Notable Alumni

- Administration

- Working at Brandeis

- Commencement

- Offices Directory

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections

World war i and world war ii propaganda posters collection.

Description by Aaron Wirth, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in the Comparative History Program

Photos by Maggie McNeely

“Food will win the war! You came here to find freedom. Now we must help to defend her. We must supply the Allies with wheat. Let nothing go to waste. United States Food Administration.”

In the United States, certain illustrators were so popular that they played a dominant role in the production of war posters even though they had not previously been identified with poster art. For example, artist James Montgomery Flagg created a self-portrait for his depiction of Uncle Sam, one of the most widely reproduced images in history (over five million copies are said to have been printed). Cheerful glamour was contributed by Howard Chandler Christy, whose “Christy Girl” enticed men to fight or to buy liberty bonds (“I Want You for the Navy”). In addition, the poster collection at Brandeis includes such other famous artists as Adolph Treidler, Edwin Howland Blashfield, Harrison Fisher, Casper Emerson Jr., Henry Patrick Raleigh and Haskell Coffin, among others.

September 22, 2008

- About Our Collections

- Online Exhibits

- Events and In-Person Exhibits

- From the Brandeis Archives

- Browse Exhibits

World War II Propaganda Posters

“world war ii industrial incentive posters traditionally have been interpreted as visualizations of wartime cooperation between labor and business. but when placed in their historical context, these posters reveal tensions between workers and management that were, like the posters themselves, ever present”.

– Bird, William L and Harry R. Rubenstein, Design for Victory: World War II Posters on the American Home Front

Together We Can Do It “Keep Em’ Firing,” General Motors Corporation. Oldsmobile Division, 1942

Wartime posters utilized graphics arts and advertising to persuade Americans that the home front and the factories were also an important aspect of the war effort. There was a great deal of thought and design put into the war posters. In January 1942, the War Advertising Council was created and consisted of staff from national advertisers and Madison Avenue advertising agencies. The U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) was created in June 1942. They reviewed, approved and distributed war posters. They strived to plaster posters everywhere, urging volunteers to treat posters “as real war ammunition” and “never let a poster lie idle.” The U.S. Office for Emergency Management’s War Production Board (WPB) created imagery for factories encouraging production. The WPB contracted designers and commercial illustrators to create posters. They urged factory managers to order plenty of posters and cautioned them that “posters put up in a ration of less than one for each 100 workmen on the shift are usually too thinly spread to be wholly effective.” The OWI developed six propaganda themes for the posters. One was “The Need to Work” which depicted the importance of Americans working in order to win the war. The posters left out the realities of the tensions between management and labor. From 1933-1938 there had been more than 10,000 labor strikes. Workers and management had a history of antagonism towards each other, but the wartime emergency demanded cooperation between the two. Industrial-incentive posters were plastered all over the factory floor. The essence of work shifted from working for big business to doing your patriotic duty for your country. Management hoped these posters would create a sense of unity and urgency. However, cooperation was temporary and fleeting. When the war ended, the tensions and struggles between labor and management resumed.

Skip to Main Content

- My Assessments

- My Curriculum Maps

- Communities

- Workshop Evaluation

Share Suggestion

Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? Analyzing World War II Posters

Web-based Content

Grade levels, course, subject.

- Printer Friendly Version

Compare patterns of continuity and change over time, applying context of events.

Compare the interpretation of historical events and sources , considering the use of fact versus opinion , multiple perspectives, and cause and effect relationships.

Evaluate patterns of continuity and rates of change over time, applying context of events.

Evaluate the interpretation of historical events and sources , considering the use of fact versus opinion , multiple perspectives, and cause and effect relationships.

Compare the impact of historical documents, artifacts , and places which are critical to the U.S.

Evaluate the impact of historical documents, artifacts , and places in U.S. history which are critical to world history.

Evaluate how conflict and cooperation among groups and organizations in the U.S. have influenced the growth and development of the world.

- Ethnicity and race

- Working conditions

- Immigration

- Military conflict

- Economic stability

Contrast the importance of historical documents, artifacts , and sites which are critical to world history.

Know that works in the arts can be described by using the arts elements, principles and concepts (e.g., use of color, shape and pattern in Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie ; use of dynamics, tempo, texture in Ravel’s Bolero ).

Explain and apply the critical examination processes of works in the arts and humanities.

- Compare and contrast

- Form and test hypotheses

- Evaluate/form judgments

Determine and apply criteria to a person’s work and works of others in the arts (e.g., use visual scanning techniques to critique the student’s own use of sculptural space in comparison to Julio Gonzales’ use of space in Woman Combing Her Hair ).

Examine and evaluate various types of critical analysis of works in the arts and humanities.

- Contextual criticism

- Formal criticism

- Intuitive criticism

Describe and analyze the effects that works in the arts have on groups, individuals and the culture (e.g., Orson Welles’ 1938 radio broadcast, War of the Worlds ).

Identify and/or explain stated or implied main ideas and relevant supporting details from a text.

Note: Items may target specific paragraphs.

Explain, interpret, compare, describe, analyze, and/or evaluate plot in a variety of nonfiction:

Note: Plot may also be called action.

- elements of the plot (e.g. exposition, conflict, rising action, climax, falling action, and/or resolution)

- the relationship between elements of the plot and other components of the text

- how the author structures plot to advance the action

Explain, interpret, compare, describe, analyze, and/or evaluate theme in a variety of nonfiction:

- the relationship between the theme and other components of the text

- comparing and contrasting how major themes are developed across genres

- the reflection of traditional and contemporary issues, themes, motifs, universal characters, and genres

- the way in which a work of literature is related to the themes and issues of its historical period

Explain, interpret, compare, describe, analyze, and/or evaluate voice, tone, style, and mood in a variety of nonfiction:

- the relationship between the tone, style, and/or mood and other components of the text

- how voice and choice of speaker (narrator) affect the mood, tone, and/or meaning of the text

- how diction, syntax, figurative language, sentence variety, etc., determine the author’s style

- Big Ideas Comprehension requires and enhances critical thinking and is constructed through the intentional interaction between reader and text Information to gain or expand knowledge can be acquired through a variety of sources. Artists use tools and resources as well as their own experiences and skills to create art. Historical context is needed to comprehend time and space. Historical interpretation involves an analysis of cause and result. Humans have expressed experiences and ideas through the arts throughout time and across cultures. People have expressed experiences and ideas through the arts throughout time and across cultures. People use both aesthetic and critical processes to assess quality, interpret meaning and determine value. Perspective helps to define the attributes of historical comprehension. The arts provide a medium to understand and exchange ideas. The history of the United States continues to influence its citizens, and has impacted the rest of the world. The skills, techniques, elements and principles of the arts can be learned, studied, refined and practiced. There are formal and informal processes used to assess the quality of works in the arts. World history continues to influence Pennsylvanians, citizens of the United States, and individuals throughout the world today.

- Concepts Essential content of text, including literary elements and devices, inform meaning Essential content, literary elements and devices inform meaning Informational sources have unique purposes. Textual structure, features and organization inform meaning Validity of information must be established. A play’s theme may not always be explicit or easy to put into words, but all plays imply certain philosophical attitudes and convey certain values or beliefs about living. Actors and directors depend on research skills to gain insights into a play’s themes and characters. Artistic teams analyze prior critical response in order to inform their own artistic vision. Artists and students of art frequently engage together in formal critiques of artwork as part of the process of developing their practice. Artists assess the quality of their work using evaluation criteria that is specific to the media, material, or technique. Artists choose tools and techniques that convey emotion and evoke emotional response. Artists create works of art in response to significant events. Artists create works of art that invite multiple interpretations. Artists often address social issues or concerns in their artwork. Artists use various techniques to create strong reactions to their work. Beliefs about the value of particular plays and theatre practices have changed over time and across cultures. Choreographers and dancers can use works in dance to communicate ideas that challenge cultural norms. Comprehension of the experiences of individuals, society, and how past human experience has adapted builds aptitude to apply to civic participation. Conflict and cooperation among social groups, organizations, and nation-states are critical to comprehending society in the United States. Domestic instability, ethnic and racial relations, labor relation, immigration, and wars and revolutions are examples of social disagreement and collaboration. Conflict and cooperation among social groups, organizations, and nation-states are critical to comprehending the American society. Eastern theatre traditions value forms, symbols and practices differently than Western theatre. Groups that have influenced world history had different beliefs, customs, ceremonies, traditions, and social practices. Historical causation involves motives, reasons, and consequences that result in events and actions. Historical causation involves motives, reasons, and consequences that result in events and actions. Some consequences may be impacted by forces of the irrational or the accidental. Historical literacy requires a focus on time and space, and an understanding of the historical context of events and actions. Historical literacy requires a focus on time and space, and an understanding of the historical context, as well as an awareness of point of view. Historical skills (organizing information chronologically, explaining historical issues, locating sources and investigate materials, synthesizing and evaluating evidence, and developing arguments and interpretations based on evidence) are used by an analytical thinker to create a historical construction. Human organizations work to socialize members and, even though there is a constancy of purpose, changes occur over time. Learning about the past and its different contexts shaped by social, cultural, and political influences prepares one for participation as active, critical citizens in a democratic society. Modern technological advances have increased communication between cultures, allowing elements of dance from different cultures to be used by people all over the world. Modern technologies have expanded the tools that dancers and choreographers use to create, perform, archive and respond to dance. Musicians use both aesthetic and critical processes to assess their own work and compare it to the works of others. People engage in dance throughout their lives. People have applied different criteria for assessing quality and value of works of art depending on the place, time, culture, and social context in which the works are viewed. People make judgments about the quality of artwork. People make judgments about the quality of works in dance based on certain criteria. People talk about theiropinions of dance. People use analytic processes to understand and evaluate works of art. People use criteria to decide the quality of a work of art. People use criteria to describe the quality of musical works and/or performances. People use criteria to determine the quality of works of art. People use resources available in their communities to experience and/or engage in theatre throughout their lives. People use resources available in their communities to make music throughout their lives. People who watch theatre later talk about what they have seen. People who watch theatrical performances talk about how they were created. Social entities clash over disagreement and assist each other when advantageous. Textual evidence, material artifacts, the built environment, and historic sites are central to understanding United States history. Textual evidence, material artifacts, the built environment, and historic sites are central to understanding world history. The study of aesthetics includes the examination of the nature and value of art. Theatre artists attend live performances of others work in order to inform their own practice and perspectives. Theatre artists create habits of self reflection and evaluation to inform their work. Theatre artists participate in philosophical discussions to help inform their practice. Theatre artists use both aesthetic and critical processes to assess their own work and compare it to the works of others. There are similarities between works in different arts disciplines from different time periods and different cultures. There are specific models of criticism that people use to determine the quality of musical works. There is a language of criticism people use when discussing the quality of a work of art. There is a language of criticism that people use to determine the quality of musical works. Viewers of art often respond to a work intuitively, using subjective insight. When assessing quality, interpreting meaning, and determining value, one might consider the artist’s intent and/or the viewer’s interpretation. Works in theatre can affect group thought and/or customs and traditions. Artists often create work based on a philosophical position. Technology has the potential to change the way we perceive the value of art.

- Competencies Analyze and evaluate information from sources for relevance to the research question, topic or thesis. Analyze the use of facts and opinions across texts Critically evaluate primary and secondary sources for validity, perspective, bias, and relationship to topic. Evaluate information from a variety of reference sources for its relevance to the research question, topic or thesis. Evaluate organizational features of text (e.g. sequence, question/answer, comparison/contrast, cause/effect, problem/solution) as related to content to clarify and enhance meaning Evaluate the effects of inclusion and exclusion of information in persuasive text Evaluate the presentation of essential and nonessential information in texts, identifying the author’s implicit or explicit bias and assumptions Evaluate the relevance and reliability of information, citing supportive evidence and acknowledging counter points of view in texts Evaluate the relevance and reliability of information, citing supportive evidence in texts Evaluate the use of graphics in text as they clarify and enhance meaning Identify and evaluate essential content between and among various text types Summarize, draw conclusions, and make generalizations from a variety of mediums Synthesize information gathered from a variety of sources. Use and cite evidence from texts to make assertions, inferences, generalizations, and to draw conclusions Analyze a primary source for accuracy and bias and connect it to a time and place in United States history. Analyze a primary source for accuracy and bias, then connect it to a time and place in world history. Analyze and create dance that attempts to question cultural norms. Analyze and interpret a philosophical position and explain how it is manifested in a particular artist’s work. Analyze and interpret the work of a contemporary artist who addresses social issues or concerns. Analyze filmed examples of Eastern theatre traditions, e.g. kabuki or Chinese Opera, to explore cultural philosophical beliefs about beauty. Analyze the interaction of cultural, economic, geographic, political, and social relations for a specific time and place. Analyze the techniques used by a controversial artist and explain how the techniques affect audience response. Analyze their own performances and compositions and make judgments about their own works as compared with those of other performers and composers. Articulate opinions about what makes art “good”. Articulate the context of a historical event or action. Attend a live performance and identify ways in which the actors used the elements of theatre to tell the story. Construct a critical analysis that compares an interpretation of two works art: one that relies heavily on the artist’s intent for interpretation, and one that relies solely an individual interpretation. Construct an intuitive critical response to a work of art based on subjective insight. Contrast how a historically important issue in the United States was resolved and compare what techniques and decisions may be applied today. Create a multimedia presentation designed to guide the viewer through analysis of a work using formal, contextual and intuitive criticism. Create a work of art in response to a historical event that has personal significance. Create, rehearse, reflect and revise to prepare and film a performance, then respond to that performance using intuitive and formal criticism. Define criteria that describe the quality of a performance. Describe the nature and value of a particular work of art using terms from aesthetics. Describe the role of inventions in the history of art, e.g. how the invention of the camera influenced the valuation and perception of paintings. Document viewers’ interpretations of their artwork. Evaluate cause-and-result relationships bearing in mind multiple causations. Evaluate the quality of a finished print using criteria appropriate for a specific type of printmaking (engraving, intaglio, linocut, etc.). Explain how artists choose tools and techniques to convey emotion and evoke emotional response. Explain similarities between works in dance, music, theatre and visual arts in various cultural and historical contexts. Explore modern performances of plays considered controversial or unacceptable in their time, e.g. The Doll’s House, and compare and contrast first-person accounts of critical response and audience reaction with responses today. Identify basic criteria that people use to assess the quality of works in dance. Identify characteristics of different types of artistic criticism: contextual, formal and intuitive. Identify opportunities to continue to be involved in dance after graduation. Identify post-graduation opportunities to be part of the musical community as audience members, amateur musicians or professional musicians. Identify post-graduation opportunities to be part of the theatre community as audience members, advocates, and amateur or professional theatre artists. Identify reason(s) for calling a work of art “good.” Identify the criteria by which a work of art would have been evaluated in its original historical, cultural or social context and compare it to criteria used to assess quality and value today. Identify the criteria that describe the quality of musical works and/or performances. Identify, describe and analyze plays or theatre works through history which have changed cultural attitudes, e.g. Teatro Campesino or Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast. In production teams, create a unified production concept using critical response to explore meaning and theme. Participate in a formal critique with peers to assess the developing qualities in their own artwork. Read a non-traditional or abstract play from a theatre movement such as the Theatre of the Absurd (Beckett, Genet, etc.) and describe the philosophical attitudes the play implies. Read critical analysis and identify and attend a variety of regional theatre offerings. Read, analyze and respond to philosophical thought concerning the role of theatre in contemporary society. Research plays and scenes in context and analyze the plays’ historical and cultural connections to determine the author’s intent. Summarize how conflict and compromise in United States history impact contemporary society. Synthesize elements of different cultural dance forms to create new, original works in dance. Talk about their opinions of various dances using appropriate vocabulary. Use a basic vocabulary of artistic criticism to discuss the quality of musical works. Use a basic vocabulary of artistic criticism when viewing and discussing many different types of art. Use contemporary web technologies to archive and analyze their own and others’ performances, then use formal models of criticism to make judgments and compare and contrast their work with the work of others. Use modern technology tools to create, perform, archive and respond to dance. Use theatre vocabulary to label elements of a performance: costumes, props, stage, etc.

Description

In this lesson plan, students analyze World War II posters, chosen from online collections, to explore how argument, persuasion and propaganda differ. The lesson begins with a full-class exploration of the famous "I WANT YOU FOR U.S. ARMY" poster, wherein students explore the similarities and differences between argument, persuasion, and propaganda and apply one of the genres to the poster. Students then work independently to complete an online analysis of another poster and submit either an analysis worksheet or use their worksheet responses to write a more formal essay.

Web-based Resource

Access this resource at:

Content Provider

ReadWriteThink

Here at ReadWriteThink , our mission is to provide educators, parents, and afterschool professionals with access to the highest quality practices in reading and language arts instruction by offering the very best in free materials.

Date Published

- University Archives

- Special Collections

- Records Management

- Policies and Forms

- Sound Recordings

- Theses and Dissertations

- Selections From Our Digitized Collections

- Videos from the Archives

- Special Collections Exhibits

- University Archives Exhibits

- Research Guides

- Current Exhibits

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Past Exhibits

- Camelot Comes to Brandeis

- Special Collections Spotlight

- Library Home

- Degree Programs

- Majors and Minors

- Graduate Programs

- The Brandeis Core

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Brandeis Online

- Brandeis International Business School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Heller School for Social Policy and Management

- Rabb School of Continuing Studies

- Precollege Programs

- Faculty and Researcher Directory

- Brandeis Library

- Academic Calendar

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Summer School

- Financial Aid

- Research that Matters

- Resources for Researchers

- Brandeis Researchers in the News

- Provost Research Grants

- Recent Awards

- Faculty Research

- Student Research

- Centers and Institutes

- Office of the Vice Provost for Research

- Office of the Provost

- Housing/Community Living

- Campus Calendar

- Student Engagement

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Dean of Students Office

- Orientation

- Hiatt Career Center

- Spiritual Life

- Graduate Student Affairs

- Directory of Campus Contacts

- Division of Creative Arts

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts

- Theater Arts Productions

- Brandeis Concert Series

- Public Sculpture at Brandeis

- Women's Studies Research Center

- Creative Arts Award

- Our Jewish Roots

- The Framework for the Future

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Distinguished Faculty

- Nobel Prize 2017

- Notable Alumni

- Administration

- Working at Brandeis

- Commencement

- Offices Directory

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections

World war i and world war ii propaganda posters.

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections, Library and Technology Services Brandeis University

The Brandeis University World War I and World War II Propaganda Posters collection includes nearly 100 different images (a majority from the WWI era) addressing a variety of American war aims. The posters were inspired by Western European examples, and their development and production in the United States harnessed the prodigious skills of artists and industrial designers. Posters often promoted support for programs, including The United War Work Campaign, the Red Cross and most notably, the Liberty and Victory loan programs. The first and second Liberty loan campaigns of 1917, the third and fourth of 1918, and the Victory loan push of early 1919 created a vast amount of poster art on both the local and national levels.

Many designs were created, the majority of which were printed in large quantities. A number of artists were recruited to design propaganda posters during the two wars; many were already widely known through their work in books, magazines and advertising. The Brandeis collection includes such famous artists as Howard Chandler Christy, Haskell Coffin, Casper Emerson, Jr., Harrison Fisher, James Montgomery Flagg, Henry Patrick Raleigh and Adolph Treidler, to name a few; Edward Penfield is not included.

View the full finding aid to the WWI and WWII Propaganda Posters collection.

- About Our Collections

- Events and In-Person Exhibits

- Collection Essays

Special Collections Spotlight Essay

Essay on Colonel Edward H. McCrahon Family Collection of World War I Posters

World War I and World War II Propaganda Posters Exhibit

- Exhibit Home

- World War I 191?

- World War I 1917

- World War I 1918

- World War II

World War II-Era Posters and Propaganda

The more than 500 United States and international WWII-era posters and related material held in Milner Library's Government Documents World War Poster Collection illustrate how government agencies, organizations and companies across the globe used visual media to influence public opinion on the home and war fronts. Designed by important artists of the period, the posters convey a broad range of messages using a variety of artistic styles. These iconic visual artifacts share the common goal of communicating with, and influencing, a mass audience in public spaces.

As a federal depository library, Milner Library received many of the U.S. posters from the federal government’s Government Printing Office. Other items were donated, including the French broadside bulletins by Illinois State (Normal) University alumnus, Ernest R. Pirka (1940–42), who was stationed in France during the war.

Please note the collection includes items for their historical perspective and significance. Milner Library in no way condones the use of language or images that is offensive to persons of any race, religion, disability status, ethnicity, national origin, gender or sexual orientation.

This digital collection was previously titled Propaganda on All Fronts: United States and International World War II-Era Posters .

Related Collection

World War I Posters

How to Access

View the Collection

Collection Contact

Angela Bonnell Head, Government Documents [email protected]

Collection Highlights

Careless Talk

Artists contrasted zipped or button-lipped cartoon characters and wartime scenes of devastation and personal injury to send the message loose lips on the home front could unintentionally reveal information to spies and saboteurs.

Conservation of natural resources

Conservation and sacrifices on the home front played an important role in protecting those serving overseas and in winning the war. Growing and preserving food was inspired by catchy “Can All You Can” designs or via easy step-by-step instructions on canning.

Defense and war bonds

Resonating with vibrant patriotic symbols such as the Statue of Liberty and the American flag, “War Bond” drive posters from the U.S. Treasury Department were instrumental in soliciting donations to finance the war and provided another mechanism those on the home front could contribute to war efforts.

German propaganda: the 1936 Berlin Olympics

The German-created Nazi propaganda piece, American Illustrated News, targeted international spectators and press attending the XIth Olympiad in Berlin. Herbert Dassel, C. H. Kleukens and Paul Stadlinger shared graphic design credits and Karl Bergmann served as its editor. Printed on fragile newsprint, this now rare item was donated by an Illinois State University emeritus faculty member, Harlan W. Peithman.

Productivity

From rivet guns to machine guns, posters explicitly made the connection from the factory to the frontlines.

Women serving in the war effort

Women are depicted in a wide variety of war roles including “Jenny on the Job,” a model production worker drawn by artist Kula Robbins in a series of posters issued by the U.S. Public Health Services.

Additional Links

- Directions and Parking

- Accessibility Services

- Library Spaces

- Staff Directory

University Resources

World War II Propaganda Posters in America Term Paper

Introduction.

Propaganda was used during the war to sway American opinion against the Germans and the Japanese as much as it was devoted to bolster American nationalistic sentiment. Propaganda is essentially the use of messages to manipulate the beliefs and opinions of the audience. A number of studies have been conducted looking into the ‘evil’ and ‘shameful’ use of propaganda evidenced by Hitler in order to gain and maintain support for his Nazi movement, but other countries engaged in these same techniques during the war. In the following three posters, created and used in America, it can be seen that imagery, text and use of color was specifically designed to manipulate public feeling and opinion.

The anti-German poster features the image of a giant Nazi boot in the process of stepping on a white church with steeple. The boot is identifiable by the dangerous red swastika blazoned to the ankle. It’s made immediately dangerous and cruel by the sharp barbs on the spur and it seems impending by its giant size and its ability to already be stepping on the church. The imagery of the boot stepping on the American church is not just a threat to the religious ideals of the country but a threat to freedom itself as the church often doubled as the government meeting hall.

This danger to the American way of life is reinforced with the slogan on the poster which announces “We’re fighting to prevent this”, suggesting that without full-hearted resistance, this type of scene is inevitable. The colors used are either grey or greyed out, suggesting a world in which all variety and color has been leached out of existence. The poster is intended to convey a sense of immediate Nazi threat, oppression and hopelessness should one not obey the title and resist.

The anti-Japanese poster is even more explicit in its message. The imagery includes the hopeless march of a long line of ragged prisoners as backdrop to the image of a ragged and starved-looking white man with his hands apparently tied behind his back reacting to the blow he’s just received from the butt of a rifle held by a sneering Japanese soldier in hard-hat and uniform. A newspaper clipping seems burned onto the surface highlighting the headline. The headline contributes to the text of the poster.

It reads, “5200 Yank Prisoners Killed by Jap Torture in Phillipines: Cruel ‘March of Death’ Described.” The larger text of the poster at the top reads, “What are you going to do about it?”, insisting upon personal involvement while the text at the bottom encourages long-term support by insisting that the country “Stay on the job until every murdering jap is wiped out!” These messages are delivered in highly alarming oranges, reds and blacks that heighten the emotional response through its very warm palette.

The pro-American poster is also guilty of using propaganda techniques in its presentation through its imagery, text and colors. The imagery makes blatant appeals to the national symbol of strength in the form of the bald eagle as it poises to strike. The impression of movement is reinforced by the slightly diagonal stripes seen behind the eagle. The top stripes are predominantly blue while the bottom stripes are red, introducing the red, white and blue of the American flag. The text of the poster announces “America Calling” prompting an almost automatic response to answer. This text is followed by the catchy slogan, “Take your place in Civilian Defense”, with its repeating /s/ sounds that initiate an urge toward movement and involvement.

It’s easy enough to point fingers and claim propaganda, but much of the literature we see today could fall within the definition of this technique. Nothing more than an appeal to sway opinion through hard-hitting imagery and emotional appeals, America was equally as guilty of using propaganda on its citizens in seeking support for the war effort and in encouraging nationalistic bias.

Anti-German poster. Web.

Anti-Japanese poster. Web.

Pro-American poster. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, November 3). World War II Propaganda Posters in America. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-ii-propaganda-posters-in-america/

"World War II Propaganda Posters in America." IvyPanda , 3 Nov. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-ii-propaganda-posters-in-america/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'World War II Propaganda Posters in America'. 3 November.

IvyPanda . 2021. "World War II Propaganda Posters in America." November 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-ii-propaganda-posters-in-america/.

1. IvyPanda . "World War II Propaganda Posters in America." November 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-ii-propaganda-posters-in-america/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "World War II Propaganda Posters in America." November 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-ii-propaganda-posters-in-america/.

- History of Graphic Design: Nationalistic Posters

- Headlines twice the size of the events