Feminist Theory in Sociology

An Overview of Key Ideas and Issues

Illustration by Hugo Lin. ThoughtCo.

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Feminist theory is a major branch within sociology that shifts its assumptions, analytic lens, and topical focus away from the male viewpoint and experience toward that of women.

In doing so, feminist theory shines a light on social problems, trends, and issues that are otherwise overlooked or misidentified by the historically dominant male perspective within social theory .

Key Takeaways

Key areas of focus within feminist theory include:

- discrimination and exclusion on the basis of sex and gender

- objectification

- structural and economic inequality

- power and oppression

- gender roles and stereotypes

Many people incorrectly believe that feminist theory focuses exclusively on girls and women and that it has an inherent goal of promoting the superiority of women over men.

In reality, feminist theory has always been about viewing the social world in a way that illuminates the forces that create and support inequality, oppression, and injustice, and in doing so, promotes the pursuit of equality and justice.

That said, since the experiences and perspectives of women and girls were historically excluded for years from social theory and social science, much feminist theory has focused on their interactions and experiences within society to ensure that half the world's population is not left out of how we see and understand social forces, relations, and problems.

While most feminist theorists throughout history have been women, people of all genders can be found working in the discipline today. By shifting the focus of social theory away from the perspectives and experiences of men, feminist theorists have created social theories that are more inclusive and creative than those that assume the social actor to always be a man.

Part of what makes feminist theory creative and inclusive is that it often considers how systems of power and oppression interact , which is to say it does not just focus on gendered power and oppression, but on how this might intersect with systemic racism, a hierarchical class system, sexuality, nationality, and (dis)ability, among other things.

Gender Differences

Some feminist theory provides an analytic framework for understanding how women's location in and experience of social situations differ from men's.

For example, cultural feminists look at the different values associated with womanhood and femininity as a reason for why men and women experience the social world differently. Other feminist theorists believe that the different roles assigned to women and men within institutions better explain gender differences, including the sexual division of labor in the household .

Existential and phenomenological feminists focus on how women have been marginalized and defined as “other” in patriarchal societies . Some feminist theorists focus specifically on how masculinity is developed through socialization, and how its development interacts with the process of developing femininity in girls.

Gender Inequality

Feminist theories that focus on gender inequality recognize that women's location in and experience of social situations are not only different but also unequal to men's.

Liberal feminists argue that women have the same capacity as men for moral reasoning and agency, but that patriarchy , particularly the sexist division of labor, has historically denied women the opportunity to express and practice this reasoning.

These dynamics serve to shove women into the private sphere of the household and to exclude them from full participation in public life. Liberal feminists point out that gender inequality exists for women in a heterosexual marriage and that women do not benefit from being married.

Indeed, these feminist theorists claim, married women have higher levels of stress than unmarried women and married men. Therefore, the sexual division of labor in both the public and private spheres needs to be altered for women to achieve equality in marriage.

Gender Oppression

Theories of gender oppression go further than theories of gender difference and gender inequality by arguing that not only are women different from or unequal to men, but that they are actively oppressed, subordinated, and even abused by men .

Power is the key variable in the two main theories of gender oppression: psychoanalytic feminism and radical feminism .

Psychoanalytic feminists attempt to explain power relations between men and women by reformulating Sigmund Freud's theories of human emotions, childhood development, and the workings of the subconscious and unconscious. They believe that conscious calculation cannot fully explain the production and reproduction of patriarchy.

Radical feminists argue that being a woman is a positive thing in and of itself, but that this is not acknowledged in patriarchal societies where women are oppressed. They identify physical violence as being at the base of patriarchy, but they think that patriarchy can be defeated if women recognize their own value and strength, establish a sisterhood of trust with other women, confront oppression critically, and form female-based separatist networks in the private and public spheres.

Structural Oppression

Structural oppression theories posit that women's oppression and inequality are a result of capitalism , patriarchy, and racism .

Socialist feminists agree with Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels that the working class is exploited as a consequence of capitalism, but they seek to extend this exploitation not just to class but also to gender.

Intersectionality theorists seek to explain oppression and inequality across a variety of variables, including class, gender, race, ethnicity, and age. They offer the important insight that not all women experience oppression in the same way, and that the same forces that work to oppress women and girls also oppress people of color and other marginalized groups.

One way structural oppression of women, specifically the economic kind, manifests in society is in the gender wage gap , which shows that men routinely earn more for the same work than women.

An intersectional view of this situation shows that women of color, and men of color, too, are even further penalized relative to the earnings of white men.

In the late 20th century, this strain of feminist theory was extended to account for the globalization of capitalism and how its methods of production and of accumulating wealth center on the exploitation of women workers around the world.

Kachel, Sven, et al. "Traditional Masculinity and Femininity: Validation of a New Scale Assessing Gender Roles." Frontiers in Psychology , vol. 7, 5 July 2016, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00956

Zosuls, Kristina M., et al. "Gender Development Research in Sex Roles : Historical Trends and Future Directions." Sex Roles , vol. 64, no. 11-12, June 2011, pp. 826-842., doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9902-3

Norlock, Kathryn. "Feminist Ethics." Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . 27 May 2019.

Liu, Huijun, et al. "Gender in Marriage and Life Satisfaction Under Gender Imbalance in China: The Role of Intergenerational Support and SES." Social Indicators Research , vol. 114, no. 3, Dec. 2013, pp. 915-933., doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0180-z

"Gender and Stress." American Psychological Association .

Stamarski, Cailin S., and Leanne S. Son Hing. "Gender Inequalities in the Workplace: The Effects of Organizational Structures, Processes, Practices, and Decision Makers’ Sexism." Frontiers in Psychology , 16 Sep. 2015, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01400

Barone-Chapman, Maryann . " Gender Legacies of Jung and Freud as Epistemology in Emergent Feminist Research on Late Motherhood." Behavioral Sciences , vol. 4, no. 1, 8 Jan. 2014, pp. 14-30., doi:10.3390/bs4010014

Srivastava, Kalpana, et al. "Misogyny, Feminism, and Sexual Harassment." Industrial Psychiatry Journal , vol. 26, no. 2, July-Dec. 2017, pp. 111-113., doi:10.4103/ipj.ipj_32_18

Armstrong, Elisabeth. "Marxist and Socialist Feminism." Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications . Smith College, 2020.

Pittman, Chavella T. "Race and Gender Oppression in the Classroom: The Experiences of Women Faculty of Color with White Male Students." Teaching Sociology , vol. 38, no. 3, 20 July 2010, pp. 183-196., doi:10.1177/0092055X10370120

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. "The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations." Journal of Economic Literature , vol. 55, no. 3, 2017, pp. 789-865., doi:10.1257/jel.20160995

- Patriarchal Society According to Feminism

- Socialist Feminism vs. Other Types of Feminism

- The Sociology of Gender

- Definition of Intersectionality

- What Is Sexism? Defining a Key Feminist Term

- 6 Quotes from ‘Female Liberation as the Basis for Social Revolution’

- Cultural Feminism

- What Is Radical Feminism?

- The Core Ideas and Beliefs of Feminism

- Socialist Feminism Definition and Comparisons

- What Is Feminism Really All About?

- 10 Important Feminist Beliefs

- Top 20 Influential Modern Feminist Theorists

- Feminist Literary Criticism

- The Women's Liberation Movement

- Liberal Feminism

Feminist Theory in Sociology: Deinition, Types & Principles

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Feminist theory is a major branch of sociology. It is a set of structural conflict approaches which views society as a conflict between men and women. There is the belief that women are oppressed and/or disadvantaged by various social institutions.

Feminist theory aims to highlight the social problems and issues that are experienced by women. Some of the key areas of focus include discrimination on the basis of sex and gender, objectification, economic inequality, power, gender role, and stereotypes.

Feminists share a common goal in support of equality for men and women. Although all feminists strive for gender equality, there are various ways to approach this theory.

Some of the general features of feminism include:

An awareness that there are inequalities between men and women based on power and status.

These inequalities can create conflict between men and women.

Gender roles and inequalities are usually socially constructed.

An awareness of the importance of patriarchy: a system of social structures and practices in which men dominate, oppress, and exploit women.

Goals of Feminism

The perspectives and experiences of women and girls have historically been excluded from social theory and social science.

Thus, feminist theory aims to focus on the interactions and issues women face in society and culture, so half the population is not left out.

Feminism in general means the belief in the social, economic, and political equality of the sexes.

The different branches of feminism may disagree on several things and have varying values. Despite this, there are usually basic principles that all feminists support:

1. Increasing gender equality

Feminist theories recognize that women’s experiences are not only different from men’s but are unequal.

Feminists will oppose laws and cultural norms that mean women earn a lower income and have less educational and career opportunities than men.

2. Ending gender oppression

Gender oppression goes further than gender inequality. Oppression means that not only are women different from or unequal to men, but they are actively subordinated, exploited, and even abused by men.

2. Ending structural oppression

Feminist theories posit that gender inequality and oppression are the result of capitalism and patriarchy in which men dominate.

4. Expanding human choice

Feminists believe that both men and women should have the freedom to express themselves and develop their interests, even if this goes against cultural norms.

5. Ending sexual violence

Feminists recognize that many women suffer sexual violence and that actions should be taken to address this.

6. Promoting sexual freedom

Having sexual freedom means that women have control over their own sexuality and reproduction.

This can include ending the stigma of being promiscuous and ensuring that everyone has access to safe abortions.

The Waves of Feminism

The history of modern feminism can be divided into four parts which are termed ‘ waves .’ Each wave marks a specific cultural period in which specific feminist issues are brought to light.

First wave feminism

The first wave of feminism is believed to have started with the ‘Women’s Suffrage Movement’ in New York in 1848 under the leadership of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Those involved in this feminist movement were known as suffragettes. The main aim of this movement was to allow women to vote. During this time, members of the suffrage movement engaged in social campaigns that expressed dissatisfaction with women’s limited rights to work, education, property, and social agency, among others.

Emmeline Pankhurst was considered the leader of the suffragettes in Britain and was regarded as one of the most important figures in the movement. She founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a group known for employing militant tactics in their struggle for equality.

Despite the first wave of feminism being mostly active in the United States and Western Europe, it led to international law changes regarding the right for women to vote.

It is worth noting that even after this first wave, in some countries, mostly white women from privileged backgrounds were permitted to vote, with black and minority ethnic individuals being granted this right later on.

Second wave feminism

Second-wave feminism started somewhere in the 1960s after the chaos of the Second World War.

French feminist author Simone de Beauvoir published a book in 1949 entitled ‘The Second Sex’ which outlined the definitions of womanhood and how women have historically been treated as second to men.

She determined that ‘one is not born but becomes a woman’. This book is thought to have been foundational for setting the tone for the next wave of women’s rights activism.

Feminism during this period was focused on the social roles in women’s work and family environment. It broadened the debate to include a wider range of issues such as sexuality, family, reproductive rights, legal inequalities, and divorce law.

From this wave, the movement toward women’s rights included the signing of the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which stipulated that women could no longer be paid less than men for comparable work.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 included a section which prevents employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sex, race, religion, or national origin. Likewise, the famous Roe v. Wade decision protected a woman’s right to have an abortion from 1973.

Third wave feminism

The third wave of feminism is harder to pinpoint but it was thought to have taken off in the 1990s. Early activism in this wave involved fighting against workplace sexual harassment and working to increase the number of women in positions of power.

The work of Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1980s is thought to have been the root. She coined the term ‘intersectionality’ to describe the ways in which different forms of oppression intersect, such as how a black woman is oppressed in two ways: for being a woman and for being black.

Since there was not a clear goal with third-wave feminism as there was with previous waves, there is no single piece of legislation or major social change that belongs to the wave.

Fourth wave feminism

Many believe that there is now a fourth wave of feminism, which began around 2012.

It is likely that the wave sparked after allegations of sexual abuse and harassment, specifically of celebrities, which gave birth to campaigns such as Everyday Sexism Project by Laura Bates and the #MeToo movement.

With the rise of the internet and social platforms, feminist issues such as discrimination, harassment, body shaming, and misogyny can be widely discussed with the emergence of new feminists.

Fourth-wave feminism is digitally driven and has become more inclusive to include those of any sexual orientation, ethnicity, and trans individuals.

Types of Feminism

Liberal feminism.

Liberal feminism is rooted in classic liberal thought and these feminists believe that equality should be brought about through education and policy changes. They see gender inequalities as rooted in the attitudes of social and cultural institutions, so they aim to change the system from within.

Liberal feminists argue that women have the same capacity for moral reasoning and agency as men, but that the patriarchy has denied them the opportunity to practice this. Due to the patriarchy, these feminists believe that women have been pushed to remain in the privacy of their household and thus have been excluded from participating in public life.

Liberal feminists focus mainly on protecting equal opportunities for women through legislation. The Equal Rights Amendment

in 1972 was impactful for liberal feminists which enforced equality on account of sex.

Marxist feminism

Marxist feminism evolved from the ideas of Karl Marx, who claimed capitalism was to blame for promoting patriarchy, meaning that power is held in the hands of a small number of men.

Marxist feminists believe that capitalism is the cause of women’s oppression and that this oppression in turn, helps to reinforce capitalism. These feminists believe that women are exploited for their unpaid labor (maintaining the household and childcare) and that capitalism reinforces that women are a reserve for the work force and they must create the next generation of workers.

According to Marxist feminists, the system and traditional family can only be replaced by a socialist revolution that creates a government to meet the needs of the family.

Radical feminism

Radical feminists posit that power is key to gender oppression. They argue that being a woman is a positive thing but that this is not acknowledged in patriarchal societies.

The main belief of radical feminists is that equality can only be achieved through gender separation and political lesbianism. They think the patriarchy can be defeated if women recognize their own value and strength, establish trust with other women, and form female-based separatist networks in the private and public spheres.

Intersectional feminism

Intersectional feminism believes that other feminist theories create an incorrect acceptance of women’s oppression based on the experiences of mostly Western, middle-class, white women.

For instance, while they may acknowledge that the work of the suffragette movement was influential, the voting rights of the working-class or minority ethnic groups were forgotten at this time.

Intersectionality considers that gender, race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and others, are not separate, but are interwoven and can bring about different levels of oppression.

This type of feminism offers insight that not all women experience oppression in the same way. For instance, the wage gap shows that women of color and men of color are penalized relative to the earnings of white men.

Feminist theory is important since it helps to address and better understand unequal and oppressive gender relations. It promotes the goal of equality and justice while providing more opportunities for women.

True feminism benefits men too and is not only applicable to women. It allows men to be who they want to be, without being tied down to their own gender roles and stereotypes.

Through feminism, men are encouraged to be free to express themselves in a way which may be considered ‘typically feminine’ such as crying when they are upset.

In this way, men’s mental health can benefit from feminism since the shame associated with talking about their emotions can be lifted without feeling the expectation to ‘man up’ and keep their feeling buried.

With the development of intersectionality, feminism does not just focus on gendered power and oppression, but on how this might intersect with race, sexuality, social class, disability, religion, and others.

Without feminism, women would have significantly less rights. More women have the right to vote, work, have equal pay, access to health care, reproductive rights, and protection from violence. While every country has its own laws and legislature, there would have been less progress in changing these without the feminist movement.

Feminist theory is also self-critical in that it recognizes that it may not have been applicable to everyone in the past. It is understood that it was not inclusive and so evolved and may still go on to evolve over time. Feminism is not a static movement, but fluid in the way it can change and adjust to suit modern times.

Some critics suggest that a main weakness of feminist theory is that it is from a woman-centered viewpoint. While the theories also mention issues which are not strictly related to women, it is argued that men and women view the world differently.

Some may call feminist theory redundant in modern day since women have the opportunity to work now, so the nature of family life has inevitably changed in response.

However, a counterpoint to this is that many women in certain cultures are still not given the right to work. Likewise, having access to work does not eradicate the other feminist issues that are still prevalent.

Some feminists may go too far into a stage where they are man-hating which causes more harm than good. It can make men feel unwelcome to feminism if they are being blamed for patriarchal oppression and inequalities that they are not directly responsible for.

Other women may not want to identify as a feminist either if they have the impression that feminists are man-haters but they themselves like men.

There are criticisms even between feminists, with some having values that can lead to others having a negative view of feminists as a whole.

For instance, radical feminists often receive criticism for ignoring race, social class, sexual orientation, and the presence of more than two genders. Thus, there are aspects of feminism which are not inclusive.

What is the main goal of feminism?

The goal of feminism is to reach social, political, and economic equality of the sexes. Feminists aim to challenge the systemic inequalities women face on a daily basis, change laws and legislature which oppress women, put an end to sexism and exploitation of women, and raise awareness of women’s issues.

However, the different types of feminists may have distinct goals within their movement and between each other.

How was feminist theory founded?

Although many early writings could be characterized as feminism or embodying the experiences of women, the history of Western feminist theory usually begins with the works of Mary Wollstonecraft.

Wollstonecraft was one of the first feminist writers, responsible for her publications such as ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’, published in 1792.

How does feminist theory relate to education?

Feminist theory helps us understand gender differences in education, gender socialization, and how the education system may be easier for boys to navigate than girls.

Many feminists believe education is an agent of secondary socialization that helps enforce patriarchy.

Feminist theory aims to promote educational opportunities for girls. It assures that they should not limit their educational aspirations because they may go against what is traditionally expected of them.

What are feminist sociologists view on family roles and relationships?

Some feminists view the function of the nuclear family as a place where patriarchal values are learned by individuals, which in turn add to the patriarchal society.

Young girls may be socialized to believe that inequality and oppression are a normal part of being a woman. Boys are socialized to believe they are superior and have authority over women.

Feminists often believe that the nuclear family teaches children gender roles which translates to gender roles in wider society.

For instance, girls may learn to accept that being a housewife is the only possible or acceptable role for women. Some feminists also believe that the division of labor is unequal in nuclear families, with women and girls accepting subservient roles in the household.

How does feminist theory relate to crime?

Feminists recognize that there is a disproportionate amount of violence and crime against women and that the reason may be due to the inequalities and oppression that women face.

Suppose the patriarchy posits that men are more powerful. In that case, this can lead them to abuse this power over women, resulting in harassment, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and even murder of women.

Feminists point out that there is a lot of systemic sexism in the justice system which needs to be tackled. Female victims of sexual abuse from men may often feel as if they are the ones put on trial and even experience blame for what happened to them.

Thus, many women do not report their sexual abuse for fear of not being believed or taken seriously in a system that favors men.

Therefore, many feminists would aim to fix the system so that fewer men commit these crimes and that there is proper justice for women who experience violence from men.

How far would sociologists agree that feminism has changed marriage?

Feminists often believe that the meaning of marriage is deeply rooted in patriarchy and gender inequality. In modern times, it would, therefore, not make sense for a woman to get married unless she has a partner willing to overturn a lot of the traditional and sexist values of marriage.

Most feminists believe that women should have the choice over whether they want to get married or even be in a relationship. Marriage for feminists can be; however, they want it to be, including their vows and values that make them and their partners equal.

A study found that having a feminist partner was linked to healthier heterosexual relationships for women (Rudman & Phelan, 2007).

They also found that men with feminist partners reported more stable relationships and greater sexual satisfaction, suggesting that feminism may predict happier relationships.

There are differences between radical and liberal feminism regarding ideas about the private sphere. Liberal feminists are generally not against heterosexual marriage and having children, as long as this is what the woman wants.

If the woman is treated as an equal by their partner and chooses how to raise their family, this is a feminist choice.

Even in modern marriage, radical feminists argue that women married to men are under patriarchal rule and are still made to complete much of the unpaid labor in the household compared to their husbands.

What is meant by the term malestream?

Feminists use the term malestream to highlight the need for more inclusive research methodologies and theoretical perspectives that better represent and address the experiences and issues of women and other marginalized groups.

It’s a call to move beyond the male-centric biases in various academic disciplines, including sociology.

Armstrong, E. (2020). Marxist and Socialist Feminisms. Companion to Feminist Studies , 35-52.

Bates, L. (2016). Everyday sexism: The project that inspired a worldwide movement . Macmillan.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2006). Intersectionality, identity politics and violence against women of color. Kvinder, kön & forskning , (2-3).

Malinowska, A. (2020). Waves of Feminism. The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication, 1, 1-7.

Oxley, J. C. (2011). Liberal feminism. Just the Arguments, 100, 258262.

Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2007). The interpersonal power of feminism: Is feminism good for romantic relationships?. Sex Roles, 57 (11), 787-799.

Srivastava, K., Chaudhury, S., Bhat, P. S., & Sahu, S. (2017). Misogyny, feminism, and sexual harassment. Industrial psychiatry journal, 26( 2), 111.

Thompson, D. (2001). Radical feminism today . Sage.

Related Articles

Latour’s Actor Network Theory

Cultural Lag: 10 Examples & Easy Definition

Value Free in Sociology

Cultural Capital Theory Of Pierre Bourdieu

Pierre Bourdieu & Habitus (Sociology): Definition & Examples

Two-Step Flow Theory Of Media Communication

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Feminism: An Essay

Feminism: An Essay

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on April 27, 2016 • ( 6 )

Feminism as a movement gained potential in the twentieth century, marking the culmination of two centuries’ struggle for cultural roles and socio-political rights — a struggle which first found its expression in Mary Wollstonecraft ‘s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). The movement gained increasing prominence across three phases/waves — the first wave (political), the second wave (cultural) and the third wave (academic). Incidentally Toril Moi also classifies the feminist movement into three phases — the female (biological), the feminist (political) and the feminine (cultural).

The first wave of feminism, in the 19th and 20th centuries, began in the US and the UK as a struggle for equality and property rights for women, by suffrage groups and activist organisations. These feminists fought against chattel marriages and for polit ical and economic equality. An important text of the first wave is Virginia Woolf ‘s A Room of One’s Own (1929), which asserted the importance of woman’s independence, and through the character Judith (Shakespeare’s fictional sister), explicated how the patriarchal society prevented women from realising their creative potential. Woolf also inaugurated the debate of language being gendered — an issue which was later dealt by Dale Spender who wrote Man Made Language (1981), Helene Cixous , who introduced ecriture feminine (in The Laugh of the Medusa ) and Julia Kristeva , who distinguished between the symbolic and the semiotic language.

The second wave of feminism in the 1960s and ’70s, was characterized by a critique of patriarchy in constructing the cultural identity of woman. Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex (1949) famously stated, “One is not born, but rather becomes a woman” – a statement that highlights the fact that women have always been defined as the “Other”, the lacking, the negative, on whom Freud attributed “ penis-envy .” A prominent motto of this phase, “The Personal is the political” was the result of the awareness .of the false distinction between women’s domestic and men’s public spheres. Transcending their domestic and personal spaces, women began to venture into the hitherto male dominated terrains of career and public life. Marking its entry into the academic realm, the presence of feminism was reflected in journals, publishing houses and academic disciplines.

Mary Ellmann ‘s Thinking about Women (1968), Kate Millett ‘s Sexual Politics (1969), Betty Friedan ‘s The Feminine Mystique (1963) and so on mark the major works of the phase. Millett’s work specifically depicts how western social institutions work as covert ways of manipulating power, and how this permeates into literature, philosophy etc. She undertakes a thorough critical understanding of the portrayal of women in the works of male authors like DH Lawrence, Norman Mailer, Henry Miller and Jean Genet.

In the third wave (post 1980), Feminism has been actively involved in academics with its interdisciplinary associations with Marxism , Psychoanalysis and Poststructuralism , dealing with issues such as language, writing, sexuality, representation etc. It also has associations with alternate sexualities, postcolonialism ( Linda Hutcheon and Spivak ) and Ecological Studies ( Vandana Shiva )

Elaine Showalter , in her “ Towards a Feminist Poetics ” introduces the concept of gynocriticism , a criticism of gynotexts, by women who are not passive consumers but active producers of meaning. The gynocritics construct a female framework for the analysis of women’s literature, and focus on female subjectivity, language and literary career. Patricia Spacks ‘ The Female Imagination , Showalter’s A Literature of their Own , Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar ‘s The Mad Woman in the Attic are major gynocritical texts.

The present day feminism in its diverse and various forms, such as liberal feminism, cultural/ radical feminism, black feminism/womanism, materialist/neo-marxist feminism, continues its struggle for a better world for women. Beyond literature and literary theory, Feminism also found radical expression in arts, painting ( Kiki Smith , Barbara Kruger ), architecture( Sophia Hayden the architect of Woman’s Building ) and sculpture (Kate Mllett’s Naked Lady).

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: A Literature of their Own , A Room of One's Own , Barbara Kruger , Betty Friedan , Dale Spender , ecriture feminine , Elaine Showalter , Feminism , Gynocriticism , Helene Cixous , http://bookzz.org/s/?q=Kate+Millett&yearFrom=&yearTo=&language=&extension=&t=0 , Judith Shakespeare , Julia Kristeva , Kate Millett , Kiki Smith , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Man Made Language , Mary Ellmann , Mary Wollstonecraft , Patricia Spacks , Sandra Gilbert , Simone de Beauvoir , Sophia Hayden , Susan Gubar , The Female Imagination , The Feminine Mystique , The Laugh of the Medusa , The Mad Woman in the Attic , The Second Sex , Toril Moi , Towards a Feminist Poetics , Vandana Shiva , Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Related Articles

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s Contribution to Feminism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- The Influence of Poststructuralism on Feminism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Sigmund Freud and the Trauma Theory – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Gender and Transgender Criticism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Second Wave Feminism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Feminist Theory

Jo Ann Arinder

Feminist theory falls under the umbrella of critical theory, which in general have the purpose of destabilizing systems of power and oppression. Feminist theory will be discussed here as a theory with a lower case ‘t’, however this is not meant to imply that it is not a Theory or cannot be used as one, only to acknowledge that for some it may be a sub-genre of Critical Theory, while for others it stands alone. According to Egbert and Sanden (2020), some scholars see critical paradigms as extensions of the interpretivist, but there is also an emphasis on oppression and lived experience grounded in subjectivist epistemology.

The purpose of using a feminist lens is to enable the discovery of how people interact within systems and possibly offer solutions to confront and eradicate oppressive systems and structures. Feminist theory considers the lived experience of any person/people, not just women, with an emphasis on oppression. While there may not be a consensus on where feminist theory fits as a theory or paradigm, disruption of oppression is a core tenant of feminist work. As hooks (2000) states, “Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression. I liked this definition because it does not imply that men were the enemy” (p. viii).

Previous Studies

Marxism and socialism are key components in the heritage.of feminist theory. The origins of feminist theory can be found in the 18th century with growth in the 1970s’ and 1980s’ equality movements. According to Burton (2014), feminist theory has its roots in Marxism but specifically looks to Engles’ (1884) work as one possible starting point. Burton (2014) notes that, “Origin of the Family and commentaries on it were central texts to the feminist movement in its early years because of the felt need to understand the origins and subsequent development of the subordination of the female sex” (p. 2). Work in feminist theory, including research regarding gender equality, is ongoing.

Gender equality continues to be an issue today, and research into gender equality in education is still moving feminist theory forward. For example, Pincock’s (2017) study discusses the impact of repressive norms on the education of girls in Tanzania. The author states that, “…considerations of what empowerment looks like in relation to one’s sexuality are particularly important in relation to schooling for teenage girls as a route to expanding their agency” (p. 909). This consideration can be extended to any oppressed group within an educational setting and is not an area of inquiry relegated to the oppression of only female students. For example, non-binary students face oppression within educational systems and even male students can face barriers, and students are often still led towards what are considered “gender appropriate” studies. This creates a system of oppression that requires active work to disrupt.

Looking at representation in the literature used in education is another area of inquiry in feminist research. For example, Earles (2017) focused on physical educational settings to explore relationships “between gendered literary characters and stories and the normative and marginal responses produced by children” (p. 369). In this research, Earles found evidence to support that a contradiction between the literature and children’s lived experiences exists. The author suggests that educators can help to continue the reduction of oppressive gender norms through careful selection of literature and spaces to allow learners opportunities for appropriate discussions about these inconsistencies.

In another study, Mackie (1999) explored incorporating feminist theory into evaluation research. Mackie was evaluating curriculum created for English language learners that recognized the dual realities of some students, also known as the intersectionality of identity, and concluded that this recognition empowered students. Mackie noted that valuing experience and identity created a potential for change on an individual and community level and “Feminist and other types of critical teaching and research provide needed balance to TESL and applied linguistics” (p. 571).Further, Bierema and Cseh (2003) used a feminist research framework to examine previously ignored structural inequalities that affect the lives of women working in the field of human resources.

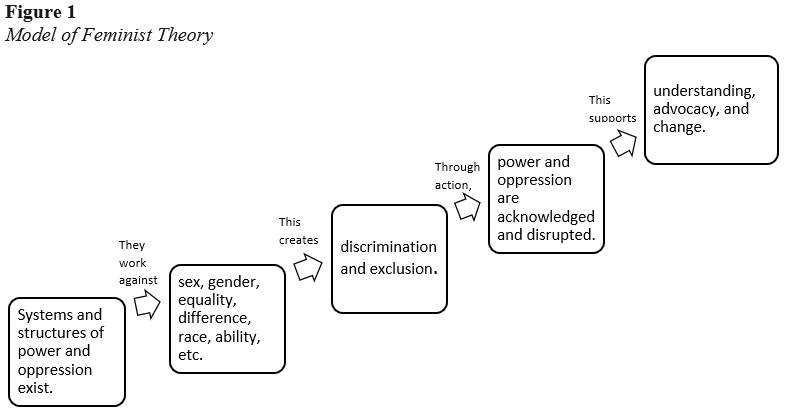

Model of Feminist Theory

Figure 1 presents a model of feminist theory that begins with the belief that systems exist that oppress and work against individuals. The model then shows that oppression is based on intersecting identities that can create discrimination and exclusion. The model indicates the idea that, through knowledge and action, oppressive systems can be disrupted to support change and understanding.

The core concepts in feminist theory are sex, gender, race, discrimination, equality, difference, and choice. There are systems and structures in place that work against individuals based on these qualities and against equality and equity. Research in critical paradigms requires the belief that, through the exploration of these existing conditions in the current social order, truths can be revealed. More important, however, this exploration can simultaneously build awareness of oppressive systems and create spaces for diverse voices to speak for themselves (Egbert & Sanden, 2019).

Constructs

Feminism is concerned with the constructs of intersectionality, dimensions of social life, social inequality, and social transformation. Through feminist research, lasting contributions have been made to understanding the complexities and changes in the gendered division of labor. Men and women should be politically, economically, and socially equal and this theory does not subscribe to differences or similarities between men, nor does it refer to excluding men or only furthering women’s causes. Feminist theory works to support change and understanding through acknowledging and disrupting power and oppression.

Proposition

Feminist theory proposes that when power and oppression are acknowledged and disrupted, understanding, advocacy, and change can occur.

Using the Model

There are many potential ways to utilize this model in research and practice. First, teachers and students can consider what systems of power exist in their classroom, school, or district. They can question how these systems are working to create discrimination and exclusion. By considering existing social structures, they can acknowledge barriers and issues inherit to the system. Once these issues are acknowledged, they can be disrupted so that change and understanding can begin. This may manifest, for example, as considering how past colonialism has oppressed learners of English as a second or foreign language.

The use of feminist theory in the classroom can ensure that the classroom is created, in advance, to consider barriers to learning faced by learners due to sex, gender, difference, race, or ability. This can help to reduce oppression created by systemic issues. In the case of the English language classroom, learners may be facing oppression based on their native language or country of origin. Facing these barriers in and out of the classroom can affect learners’ access to education. Considering these barriers in planning and including efforts to mitigate the issues and barriers faced by learners is a use of feminist theory.

Feminist research is interested in disrupting systems of oppression or barriers created from these systems with a goal of creating change. All research can include feminist theory when the research adds to efforts to work against and advocate to eliminate the power and oppression that exists within systems or structures that, in particular, oppress women. An examination of education in general could be useful since education is a field typically dominated by women; however, women are not often in leadership roles in the field. In the same way, using feminist theory for an examination into the lack of people of color and male teachers represented in education might also be useful. Action research is another area that can use feminist theory. Action research is often conducted in the pursuit of establishing changes that are discovered during a project. Feminism and action research are both concerned with creating change, which makes them a natural pairing.

Pre-existing beliefs about what feminism means can make including it in classroom practice or research challenging. Understanding that feminism is about reducing oppression for everyone and sharing that definition can reduce this challenge. hooks (2000) said that, “A male who has divested of male privilege, who has embraced feminist politics, is a worthy comrade in struggle, in no way a threat to feminism, whereas a female who remains wedded to sexist thinking and behavior infiltrating feminist movement is a dangerous threat”(p. 12). As Angela Davis noted during a speech at Western Washington University in 2017, “Everything is a feminist issue.” Feminist theory is about questioning existing structures and whether they are creating barriers for anyone. An interest in the reduction of barriers is feminist. Anyone can believe in the need to eliminate oppression and work as teachers or researchers to actively to disrupt systems of oppression.

Bierema, L. L., & Cseh, M. (2003). Evaluating AHRD research using a feminist research framework. Human Resource Development Quarterly , 14 (1), 5–26.

Burton, C. (2014). Subordination: Feminism and social theory . Routledge.

Earles, J. (2017). Reading gender: A feminist, queer approach to children’s literature and children’s discursive agency. Gender and Education, 29 (3), 369–388.

Egbert, J., & Sanden, S. (2019). Foundations of education research: Understanding theoretical components . Taylor & Francis.

Hooks, B. (2000). Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics . South End Press.

Mackie, A. (1999). Possibilities for feminism in ESL education and research. TESOL Quarterly, 33 (3), 566-573.

Pincock, K. (2018). School, sexuality and problematic girlhoods: Reframing ‘empowerment’ discourse. Third World Quarterly, 39 (5), 906-919.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Introduction to feminism, topics: what is feminism.

- Introduction

- What is Feminism?

- Historical Context

- Normative and Descriptive Components

- Feminism and the Diversity of Women

- Feminism as Anti-Sexism

- Topics in Feminism: Overview of the Sub-Entries

Bibliography

Works cited.

- General Bibliography [under construction]

- Topical Bibliographies [under construction]

Other Internet Resources

Related entries, i. introduction, ii. what is feminism, a. historical context, b. normative and descriptive components.

i) (Normative) Men and women are entitled to equal rights and respect. ii) (Descriptive) Women are currently disadvantaged with respect to rights and respect, compared with men.

Feminism is grounded on the belief that women are oppressed or disadvantaged by comparison with men, and that their oppression is in some way illegitimate or unjustified. Under the umbrella of this general characterization there are, however, many interpretations of women and their oppression, so that it is a mistake to think of feminism as a single philosophical doctrine, or as implying an agreed political program. (James 2000, 576)

C. Feminism and the Diversity of Women

Feminism, as liberation struggle, must exist apart from and as a part of the larger struggle to eradicate domination in all its forms. We must understand that patriarchal domination shares an ideological foundation with racism and other forms of group oppression, and that there is no hope that it can be eradicated while these systems remain intact. This knowledge should consistently inform the direction of feminist theory and practice. (hooks 1989, 22)

Unlike many feminist comrades, I believe women and men must share a common understanding--a basic knowledge of what feminism is--if it is ever to be a powerful mass-based political movement. In Feminist Theory: from margin to center, I suggest that defining feminism broadly as "a movement to end sexism and sexist oppression" would enable us to have a common political goal…Sharing a common goal does not imply that women and men will not have radically divergent perspectives on how that goal might be reached. (hooks 1989, 23)

…no woman is subject to any form of oppression simply because she is a woman; which forms of oppression she is subject to depend on what "kind" of woman she is. In a world in which a woman might be subject to racism, classism, homophobia, anti-Semitism, if she is not so subject it is because of her race, class, religion, sexual orientation. So it can never be the case that the treatment of a woman has only to do with her gender and nothing to do with her class or race. (Spelman 1988, 52-3)

D. Feminism as Anti-Sexism

i) (Descriptive claim) Women, and those who appear to be women, are subjected to wrongs and/or injustice at least in part because they are or appear to be women. ii) (Normative claim) The wrongs/injustices in question in (i) ought not to occur and should be stopped when and where they do.

III. Topics in Feminism: Overview of the Sub-Entries

- Alexander, M. Jacqui and Lisa Albrecht, eds. 1998. The Third Wave: Feminist Perspectives on Racism. New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.

- Anderson, Elizabeth. 1999a. “What is the Point of Equality?” Ethics 109(2): 287-337.

- ______. 1999b. "Reply” Brown Electronic Article Review Service, Jamie Dreier and David Estlund, editors, World Wide Web, (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Philosophy/bears/homepage.html), Posted 12/22/99.

- Anzaldúa, Gloria, ed. 1990. Making Face, Making Soul: Haciendo Caras. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

- Baier, Annette C. 1994. Moral Prejudices: Essays on Ethics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Barrett, Michèle. 1991. The Politics of Truth: From Marx to Foucault. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bartky, Sandra. 1990. “Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power.” In her Femininity and Domination. New York: Routledge, 63-82.

- Basu, Amrita. 1995. The Challenge of Local Feminisms: Women's Movements in Global Perspective. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Baumgardner, Jennifer and Amy Richards. 2000. Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. 1974 (1952). The Second Sex. Trans. and Ed. H. M. Parshley. New York: Vintage Books.

- Benhabib, Seyla. 1992. Situating the Self: Gender, Community, and Postmodernism in Contemporary Ethics. New York: Routledge.

- Calhoun, Cheshire. 2000. Feminism, the Family, and the Politics of the Closet: Lesbian and Gay Displacement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ______. 1989. “Responsibility and Reproach.” Ethics 99(2): 389-406.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 1990. Black Feminist Thought. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman.

- Cott, Nancy. 1987. The Grounding of Modern Feminism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.“ Stanford Law Review , 43(6): 1241-1299.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller and Kendall Thomas. 1995. “Introduction.” In Critical Race Theory, ed., Kimberle Crenshaw, et al. New York: The New Press, xiii-xxxii.Davis, Angela. 1983. Women, Race and Class. New York: Random House.

- Crow, Barbara. 2000. Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader. New York: New York University Press.

- Delmar, Rosalind. 2001. "What is Feminism?” In Theorizing Feminism, ed., Anne C. Hermann and Abigail J. Stewart. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 5-28.

- Duplessis, Rachel Blau, and Ann Snitow, eds. 1998. The Feminist Memoir Project: Voices from Women's Liberation. New York: Random House (Crown Publishing).

- Dutt, M. 1998. "Reclaiming a Human Rights Culture: Feminism of Difference and Alliance." In Talking Visions: Multicultural Feminism in a Transnational Age , ed., Ella Shohat. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 225-246.

- Echols, Alice. 1990. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-75. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Engels, Friedrich. 1972 (1845). The Origin of The Family, Private Property, and the State. New York: International Publishers.

- Findlen, Barbara. 2001. Listen Up: Voices from the Next Feminist Generation, 2nd edition. Seattle, WA: Seal Press.

- Fine, Michelle and Adrienne Asch, eds. 1988. Women with Disabilities: Essays in Psychology, Culture, and Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Fraser, Nancy and Linda Nicholson. 1990. "Social Criticism Without Philosophy: An Encounter Between Feminism and Postmodernism." In Feminism/Postmodernism, ed., Linda Nicholson. New York: Routledge.

- Friedan, Betty. 1963. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Norton.

- Frye, Marilyn. 1983. The Politics of Reality. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 1997. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Grewal, I. 1998. "On the New Global Feminism and the Family of Nations: Dilemmas of Transnational Feminist Practice." In Talking Visions: Multicultural Feminism in a Transnational Age, ed., Ella Shohat. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 501-530.

- Hampton, Jean. 1993. “Feminist Contractarianism,” in Louise M. Antony and Charlotte Witt, eds. A Mind of One’s Own: Feminist Essays on Reason and Objectivity, Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Haslanger, Sally. Forthcoming. “Oppressions: Racial and Other.” In Racism, Philosophy and Mind: Philosophical Explanations of Racism and Its Implications, ed., Michael Levine and Tamas Pataki. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Held, Virginia. 1993. Feminist Morality: Transforming Culture, Society, and Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Herrman, Anne C. and Abigail J. Stewart, eds. 1994. Theorizing Feminism: Parallel Trends in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Heywood, Leslie and Jennifer Drake, eds. 1997. Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism.

- Hillyer, Barbara. 1993. Feminism and Disability. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Hoagland, Sarah L. 1989. Lesbian Ethics: Toward New Values. Palo Alto, CA: Institute for Lesbian Studies.

- Hooks, bell. 1989. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. Boston: South End Press.

- ______. 1984. Feminist Theory from Margin to Center. Boston: South End Press.

- ______. 1981. Ain't I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Boston: South End Press.

- Hurtado, Aída. 1996. The Color of Privilege: Three Blasphemies on Race and Feminism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Jagger, Alison M. 1983. Feminist Politics and Human Nature. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- James, Susan. 2000. “Feminism in Philosophy of Mind: The Question of Personal Identity.” In The Cambridge Companion to Feminism in Philosophy, ed., Miranda Fricker and Jennifer Hornsby. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kiss, Elizabeth. 1995. "Feminism and Rights." Dissent 42(3): 342-347

- Kittay, Eva Feder. 1999. Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality and Dependency. New York: Routledge.

- Kymlicka, Will. 1989. Liberalism, Community and Culture. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mackenzie, Catriona and Natalie Stoljar, eds. 2000. Relational Autonomy: Feminist perspectives on Autonomy, Agency and the Social Self. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- MacKinnon, Catharine. 1989. Towards a Feminist Theory of the State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ______. 1987. Feminism Unmodified. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mohanty, Chandra, Ann Russo, and Lourdes Torres, eds. 1991. Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Molyneux, Maxine and Nikki Craske, eds. 2001. Gender and the Politics of Rights and Democracy in Latin America. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan.

- Moody-Adams, Michele. 1997. Fieldwork in Familiar Places: Morality, Culture and Philosophy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Moraga, Cherrie. 2000. "From a Long Line of Vendidas: Chicanas and Feminism." In her Loving in the War Years, 2nd edition. Boston: South End Press.

- Moraga, Cherrie and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds. 1981. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings of Radical Women of Color. Watertown, MA: Persephone Press.

- Narayan, Uma. 1997. Dislocating Cultures: Identities, Traditions, and Third World Feminism. New York: Routledge.

- Nussbaum, Martha. 1995. "Human Capabilities, Female Human Beings." In Women, Culture and Development : A Study of Human Capabilities, ed., Martha Nussbaum and Jonathan Glover. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 61-104.

- _______. 1999. Sex and Social Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- O’Brien, Mary. 1979. “Reproducing Marxist Man.” In The Sexism of Social and Political Theory: Women and Reproduction from Plato to Nietzsche, ed., Lorenne M. G. Clark and Lynda Lange. Toronto: Toronto University Press, 99-116. Reprinted in (Tuana and Tong 1995: 91-103).

- Ong, Aihwa. 1988. "Colonialism and Modernity: Feminist Re-presentation of Women in Non-Western Societies.” Inscriptions 3(4): 90. Also in (Herrman and Stewart 1994).

- Okin, Susan Moller. 1989. Justice, Gender, and the Family. New York: Basic Books.

- ______. 1979. Women in Western Political Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Pateman, Carole. 1988. The Sexual Contract. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Reagon, Bernice Johnson. 1983. "Coalition Politics: Turning the Century." In: Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, ed. Barbara Smith. New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 356-368.

- Robinson, Fiona. 1999. Globalizing Care: Ethics, Feminist Theory, and International Affairs. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Rubin, Gayle. 1975. “The Traffic in Women: Notes on the “Political Economy” of Sex.” In Towards an Anthropology of Women , ed., Rayna Rapp Reiter. New York: Monthly Review Press, 157-210.

- Ruddick, Sara. 1989. Maternal Thinking: Towards a Politics of Peace. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Schneir, Miriam, ed. 1994. Feminism in Our Time: The Essential Writings, World War II to the Present. New York: Vintage Books.

- ______. 1972. Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings. New York: Vintage Books.

- Scott, Joan W. 1988. “Deconstructing Equality-Versus-Difference: or The Uses of Poststructuralist Theory for Feminism.” Feminist Studies 14 (1): 33-50.

- Silvers, Anita, David Wasserman, Mary Mahowald. 1999. Disability, Difference, Discrimination: Perspectives on Justice in Bioethics and Public Policy . Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Simpson, J. A. and E. S. C. Weiner, ed., 1989. Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OED Online. Oxford University Press. “feminism, n1” (1851).

- Snitow, Ann. 1990. “A Gender Diary.” In Conflicts in Feminism, ed. M. Hirsch and E. Fox Keller. New York: Routledge, 9-43.

- Spelman, Elizabeth. 1988. The Inessential Woman. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Tanner, Leslie B. 1970 Voices From Women's Liberation. New York: New American Library (A Mentor Book).

- Taylor, Vesta and Leila J. Rupp. 1996. "Lesbian Existence and the Women's Movement: Researching the 'Lavender Herring'." In Feminism and Social Change , ed. Heidi Gottfried. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Tong, Rosemarie. 1993. Feminine and Feminist Ethics. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Tuana, Nancy and Rosemarie Tong, eds. 1995. Feminism and Philosophy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Walker, Alice. 1990. “Definition of Womanist,” In Making Face, Making Soul: Haciendo Caras , ed., Gloria Anzaldúa. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 370.

- Walker, Margaret Urban. 1998. Moral Understandings: A Feminist Study in Ethics. New York: Routledge.

- ______, ed. 1999. Mother Time: Women, Aging, and Ethics. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Walker, Rebecca, ed. 1995. To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism. New York: Random House (Anchor Books).

- Ware, Cellestine. 1970. Woman Power: The Movement for Women’s Liberation . New York: Tower Publications.

- Weisberg, D. Kelly, ed. 1993. Feminist Legal Theory: Foundations. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Wendell, Susan. 1996. The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability. New York and London: Routledge.

- Young, Iris. 1990a. "Humanism, Gynocentrism and Feminist Politics." In Throwing Like A Girl. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 73-91.

- Young, Iris. 1990b. “Socialist Feminism and the Limits of Dual Systems Theory.” In her Throwing Like a Girl and Other Essays in Feminist Philosophy and Social Theory . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- ______. 1990c. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Zophy, Angela Howard. 1990. "Feminism." In The Handbook of American Women's History , ed., Angela Howard Zophy and Frances M. Kavenik. New York: Routledge (Garland Reference Library of the Humanities).

General Bibliography

Topical bibliographies.

- Feminist Theory Website

- Race, Gender, and Affirmative Action Resource Page

- Documents from the Women's Liberation Movement (Duke Univ. Archives)

- Core Reading Lists in Women's Studies (Assn of College and Research Libraries, WS Section)

- Feminist and Women's Journals

- Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy

- Feminist Internet Search Utilities

- National Council for Research on Women (including links to centers for research on women and affiliate organizations, organized by research specialties)

- Feminism and Class

- Marxist, Socialist, and Materialist Feminisms

- M-Fem (information page, discussion group, links, etc.)

- WMST-L discussion of how to define “marxist feminism” Aug 1994)

- Marxist/Materialist Feminism (Feminist Theory Website)

- MatFem (Information page, discussion group)

- Feminist Economics

- Feminist Economics (Feminist Theory Website)

- International Association for Feminist Economics

- Feminist Political Economy and the Law (2001 Conference Proceedings, York Univ.)

- Journal for the International Association for Feminist Economics

- Feminism and Disability

- World Wide Web Review: Women and Disabilities Websites

- Disability and Feminism Resource Page

- Center for Research on Women with Disabilities (CROWD)

- Interdisciplinary Bibliography on Disability in the Humanities (Part of the American Studies Crossroads Project)

- Feminism and Human Rights, Global Feminism

- World Wide Web Review: Websites on Women and Human Rights

- International Gender Studies Resources (U.C. Berkeley)

- Global Feminisms Research Resources (Vassar Library)

- Global Feminism (Feminist Majority Foundation)

- NOW and Global Feminism

- United Nations Development Fund for Women

- Global Issues Resources

- Sisterhood is Global Institute (SIGI)

- Feminism and Race/Ethnicity

- General Resources

- WMST-L discussion on “Women of Color and the Women’s Movement” (5 Parts) Sept/Oct 2000)

- Women of Color Resources (Princeton U. Library)

- Core Readings in Women's Studies: Women of Color (Assn. of College and Research Libraries, WS Section)

- Women of Color Resource Sites

- African-American/Black Feminisms and Womanism

- African-American/Black/Womanist Feminism on the Web

- Black Feminist and Womanist Identity Bibliography (Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library)

- The Womanist Studies Consortium (Univ. of Georgia)

- Black Feminist/Womanist Works: A Beginning List (WMST-L)

- African-American Women Online Archival Collection (Duke U.)

- Asian-American and Asian Feminisms

- Asian American Feminism (Feminist Theory Website)

- Asian-American Women Bibliography (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe)

- American Women's History: A Research Guide (Asian-American Women)

- South Asian Women's Studies Bibliography (U.C. Berkeley)

- Journal of South Asia Women's Studies

- Chicana/Latina Feminisms

- Bibliography on Chicana Feminism (Cal State, Long Beach Library)

- Making Face, Making Soul: A Chicana Feminist Website

- Defining Chicana Feminisms, In Their Own Words

- CLNet's Chicana Studies Homepage (UCLA)

- Chicana Related Bibliographies (CLNet)

- American Indian, Native, Indigenous Feminisms

- Native American Feminism (Feminist Theory Website)

- Bibliography on American Indian Gender Roles and Relations

- Bibliography on American Indian Feminism

- Bibliography on American Indian Gay/Lesbian Topics

- Links on Aboriginal Women and Feminism

- Feminism, Sex, and Sexuality

- 1970's Lesbian Feminism (Ohio State Univ., Women's Studies)

- The Lesbian History Project

- History of Sexuality Resources (Duke Special Collections)

- Lesbian Studies Bibliography (Assn. of College and Research Libraries)

- Lesbian Feminism/Lesbian Philosophy

- Society for Lesbian and Gay Philosophy Internet Resources

- QueerTheory.com

- World Wide Web Review: Webs of Transgender

First published: Content last modified:

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Feminist Theory: A Summary for A-Level Sociology

This post summarises the differences between Liberal, Marxist, Radical and Difference (Postmodern) Feminists. It covers what they believe the causes of gender inequalities to be and what should be done to tackle these inequalities and male power in society.

Table of Contents

Last Updated on March 9, 2023 by Karl Thompson

This post summarises the key ideas of Radical, Liberal, Marxist and Difference Feminisms and includes criticisms of each perspective.

Introduction – Feminism: The Basics

- Inequality between men and women is universal and the most significant form of inequality.

- Gender norms are socially constructed not determined by biology and can thus be changed.

- Patriarchy is the main cause of gender inequality: women are subordinate because men have more power.

- Feminism is a political movement; it exists to rectify sexual inequalities, although strategies for social change vary enormously.

- There are four types of Feminism – Radical, Marxist, Liberal, and Difference.

Radical Feminism

- Society is patriarchal – it is dominated and ruled by men – men are the ruling class, and women the subject class.

- Blames the exploitation of women on men. It is primarily men who have benefitted from the subordination of women. Women are ‘an oppressed group.

- Rape, violence and pornography are methods through which men have secured and maintained their power over women. Andrea Dworkin (1981)

- Radical feminists have often been actively involved in setting up and running refuges for women who are the victims of male violence.

- Rosemarie Tong (1998) distinguishes between two groups of radical feminist:

- Radical-libertarian feminists believe that it is both possible and desirable for gender differences to be eradicated, or at least greatly reduced, and aim for a state of androgyny in which men and women are not significantly different.

- Radical-cultural feminists believe in the superiority of the feminine. According to Tong radical cultural feminists celebrate characteristics associated with femininity such as emotion, and are hostile to those characteristics associated with masculinity such as hierarchy.

- Some alternatives suggested by Radical Feminists include separatism – women only communes, and Matrifocal households . Some also practise political Lesbianism and political celibacy as they view heterosexual relationships as “sleeping with the enemy.”

Criticisms of Radical Feminism

- The concept of patriarchy has been criticised for ignoring variations in the experience of oppression.

- It focuses too much on the negative experiences of women, failing to recognise that some women can have happy marriages for example.

- It tends to portray women as universally good and men as universally bad, It has been accused of man hating, not trusting all men.

Marxist Feminism

- Capitalism rather than patriarchy is the principal source of women’s oppression , and capitalists are the main beneficiaries.

- The disadvantaged position of women is because of the emergence of private property and the fact that women do not own the means of production.

- Under Capitalism the nuclear family becomes even more oppressive to women and women’s subordination plays a number of important functions for capitalism:

- (1) Women reproduce the labour force for free (socialisation is done for free)

- (2) Women absorb anger – women keep the husbands going.

- (3) Because the husband has to support his wife and children, he is more dependent on his job and less likely to demand wage increases.

- The traditional nuclear family also performs the function of ‘ideological conditioning’ – it teaches the ideas that the Capitalist class require for their future workers to be passive.

- Marxist Feminists are more sensitive to differences between women who belong to the ruling class and proletarian families. They believe there is considerable scope for co-operation between working class women and men to work together for social change.

- The primary goal is the eradication of capitalism. In a communist society gender inequalities should disappear.

Criticisms of Marxist Feminism

- Radical Feminists – ignores other sources of inequality such as sexual violence.

- Patriarchal systems existed before capitalism, in tribal societies for example.

- The experience of women has not been particularly happy under communism.

Liberal Feminism

- Nobody benefits from existing inequalities: both men and women are harmed

- The explanation for gender inequality lies not so much in structures and institutions of society but in its culture and values.

- Socialisation into gender roles has the consequence of producing rigid, inflexible expectations of men and women.

- Discrimination prevents women from having equal opportunities.

- Liberal Feminists do not seek revolutionary changes: they want changes to take place within the existing structure.

- The creation of equal opportunities through policy is the main aim of liberal feminists – e.g. the Sex Discrimination Act and the Equal Pay Act.

- Liberal feminists try to eradicate sexism from the children’s books and the media.

- Liberal Feminist ideas have probably had the most impact on women’s lives – e.g. mainstreaming has taken place.

Criticisms of Liberal Feminism

- Based upon male assumptions and norms such as individualism and competition, and encourages women to be more like men and therefor denies the value of qualities traditionally associated with women such as empathy.

- Liberalism is accused of emphasising public life at the expense of private life.

- Radical and Marxist Feminists – it fails to take account of deeper structural inequalities.

- Difference Feminists argue it is an ethnocentric perspective – based mostly on the experiences of middle class, educated women.

Difference Feminism/ Postmodern Feminism

- Do not see women as a single homogenous group.

- There are differences in the experiences of working class and middle class women, women from different backgrounds and women of different sexualities.

- Criticise preceding feminist theory for claiming a ‘false universality’ (white, western heterosexual, middle class)

- Criticise preceding Feminists theory of being essentialist.

- Critique preceding Feminist theory as being part of the masculinist Enlightenment Project .

- Postmodern Feminism is concerned with language (discourses) and the relationship between power and knowledge rather than ‘politics and opportunities’.

- Helene Cixoux is an example of a postmodern/ destabilising theorist.

Criticisms of Difference Feminism

- Walby argues that women are still oppressed by objective social structures, namely Patriarchy.

- Dividing women into sub-groups weakens the movement for change.

Frequently Asked Questions about Feminism

Feminism is a diverse body of social theory which seeks to better understand the nature, extent and causes of gender inequalities. Some Feminists are also political activists who actively campaign for greater gender equality.

The main types of Feminism are Liberal, Marxist, Radical and Difference or Postmodern Feminisms. (Although many Feminists themselves may not recognise these ‘types’ because they oversimplify Feminist theory.

The goals of Feminists vary from person to person but a general shared aim is to reduce the amount of sexism and gender oppression in societies.

Yes. The majority of countries on earth still have fewer women in politics, women are still paid less than men on average, and are more likely to be subject to domestic abuse than men. And if we look at sexuality inequalities there is still overt oppression of gay and trans people in many countries.

Related Posts/ Find out More…

Feminism runs across the whole A-level Sociology course, and is especially relevant to the sociology of the family .

Other related posts include…

- An Introduction to Sex, Gender and Gender Identity (from my ‘introblock’).

- Feminist Perspectives on the Family – includes links to more in-depth posts.

- Radical Feminist Perspectives on Religion – includes links to more in-depth posts.

- Global Gender Inequalities – an overview of statistics

- How Equal are Men and Women in the UK …?

Sources Used to Write this Post

- Haralambos and Holborn (2013) – Sociology Themes and Perspectives, Eighth Edition, Collins. ISBN-10: 0007597479

- Chapman et al (2016) – A Level Sociology Student Book Two [Fourth Edition] Collins. ISBN-10: 0007597495

- Robb Webb et al (2016) AQA A Level Sociology Book 2, Napier Press. ISBN-10: 0954007921

A-Level Sociology Knowledge Disclaimer : This post has been written specifically for students revising for their A-level Sociology exams. The knowledge has been adapted from various A-level Sociology text books. These text books may mis-label or misunderstand aspects of Feminist theory and probably oversimplify them.

The knowledge above (labels used/ interpretations) is what students are assessed on in A-level Sociology, I make no claim that these representations are the same as the interpretations the theorists represented in said text books (and thus above) may make of their own theories. It may well be the case that for degree level students and beyond the theorists and theories above may be ‘correctly’ represented differently in those ”higher levels’ of academic realities”.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

3 thoughts on “Feminist Theory: A Summary for A-Level Sociology”

Explained in a lucid way😍😍

Great post. Simplifies the whole issue a lot. Thanks.

very educative

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

What is feminism?: An introduction to feminist theory

Related Papers

Canadian Woman Studies Journal: Feminist Gift Economy, A Materialist Alternative to Patriarchy and Capitalism

Review of the book Feminism: A brief introduction to the ideas, debates, and politics of the movement, by D. Cameron

Hela Mornagui

Krithika Bp

, eds., What is Feminism? (New York 1986). THIS WORK CONSISTS OF A SERIES of essays, mostly retrospective, by intellectuals and academics, all veterans of the British, American, and Canadian women's movements. The overall idea is to take stock of the prospects and problems raised by the women's movement during the past two decades. It should be stated at the outset that even to raise the question "what is feminism?" is important. "Second wave feminism," like the New Left, Black Power, and Socialist movements to which—at least in the United States — it largely succeeded has developed its own shibboleths and unquestioned assumptions that make criticism from within difficult. The editors' introduction to this volume alludes without being wholly explicit to what appear to have been special problems in its compilation. They speak, for example, of the "enormous difficulty" involved in such questions as defining feminism, of the "many ... people from a wide range of social and ethnic backgrounds [who] were invited to participate and accepted but got into difficulties," at the fact that "the book developed] into something other than what we first intended" and of their determination not to "lose sight of the celebration behind the worries" but instead to make "creative use of anxiety." As in most collections, it is hard to find a unifying theme in the essays. Only a few directly address the question that gives the anthology its title — and it is mostly these that I will discuss. Before beginning, however, I wish to note that most of the essays frequently touch upon two related, but distinguishable, themes concerning feminism. The first is the fact of enormous diversity among women which raises the question of what kind of feminist perspective and practice can unify them. The second relates to the reality of internal divisions and contradictions among feminists. The most frequently cited of these divisions is between a point of view that stresses the similarities between men and women, and one that stresses the differences between the sexes. Furthermore, in several of the essays the fact of diversity and or conflicts among women is related — though rarely clearly and directly — to another question: the relationship of the women's movement to its Eli Zaretsky, "What is Feminism?," Labourite Travail, 22 (Fall 1988), 259-266.

Alison Stone

Pre-print, pre-copy edited version of the first three chapters.

Mike Grimshaw

Contemporary Sociology

Dee Ansbergs

This paper is a reflection on my experiences as I learned the history and theories of feminism which created new opportunities for me to make meaning from my lived experiences.