Management of Stress and Anxiety Among PhD Students During Thesis Writing: A Qualitative Study

Affiliation.

- 1 Author Affiliations: Department of Medical Education, Medical Education Research Center, University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan (Drs Bazrafkan, Yousefi, and Yamani); and Applied Linguistics, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Dr Shokrpour), Shiraz, Iran.

- PMID: 27455365

- DOI: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000120

Today, postgraduate students experience a variety of stresses and anxiety in different situations of academic cycle. Stress and anxiety have been defined as a syndrome shown by emotional exhaustion and reduced personal goal achievement. This article addresses the causes and different strategies of coping with this phenomena by PhD students at Iranian Universities of Medical Sciences. The study was conducted by a qualitative method using conventional content analysis approach. Through purposive sampling, 16 postgraduate medical sciences PhD students were selected on the basis of theoretical sampling. Data were gathered through semistructured interviews and field observations. Six hundred fifty-four initial codes were summarized and classified into 4 main categories and 11 subcategories on the thematic coding stage dependent on conceptual similarities and differences. The obtained codes were categorized under 4 themes including "thesis as a major source of stress," "supervisor relationship," "socioeconomic problem," and "coping with stress and anxiety." It was concluded that PhD students experience stress and anxiety from a variety of sources and apply different methods of coping in effective and ineffective ways. Purposeful supervision and guidance can reduce the cause of stress and anxiety; in addition, coping strategy must be in a thoughtful approach, as recommended in this study.

- Academic Dissertations as Topic*

- Adaptation, Psychological

- Anxiety / psychology*

- Education, Graduate

- Interviews as Topic

- Qualitative Research

- Stress, Psychological / psychology*

- Students, Medical / psychology*

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health

PhDs are renowned for being stressful and when you add a global pandemic into the mix it’s no surprise that many students are struggling with their mental health. Unfortunately this can often lead to PhD fatigue which may eventually lead to burnout.

In this post we’ll explore what academic burnout is and how it comes about, then discuss some tips I picked up for managing mental health during my own PhD.

Please note that I am by no means an expert in this area. I’ve worked in seven different labs before, during and after my PhD so I have a fair idea of research stress but even so, I don’t have all the answers.

If you’re feeling burnt out or depressed and finding the pressure too much, please reach out to friends and family or give the Samaritans a call to talk things through.

Note – This post, and its follow on about maintaining PhD motivation were inspired by a reader who asked for recommendations on dealing with PhD fatigue. I love hearing from all of you, so if you have any ideas for topics which you, or others, could find useful please do let me know either in the comments section below or by getting in contact . Or just pop me a message to say hi. 🙂

This post is part of my PhD mindset series, you can check out the full series below:

- PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health (this part!)

- PhD Motivation: How to Stay Driven From Cover Letter to Completion

- How to Stop Procrastinating and Start Studying

What is PhD Burnout?

Whenever I’ve gone anywhere near social media relating to PhDs I see overwhelmed PhD students who are some combination of overwhelmed, de-energised or depressed.

Specifically I often see Americans talking about the importance of talking through their PhD difficulties with a therapist, which I find a little alarming. It’s great to seek help but even better to avoid the need in the first place.

Sadly, none of this is unusual. As this survey shows, depression is common for PhD students and of note: at higher levels than for working professionals.

All of these feelings can be connected to academic burnout.

The World Health Organisation classifies burnout as a syndrome with symptoms of:

– Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; – Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; – Reduced professional efficacy. Symptoms of burnout as classified by the WHO. Source .

This often leads to students falling completely out of love with the topic they decided to spend years of their life researching!

The pandemic has added extra pressures and constraints which can make it even more difficult to have a well balanced and positive PhD experience. Therefore it is more important than ever to take care of yourself, so that not only can you continue to make progress in your project but also ensure you stay healthy.

What are the Stages of Burnout?

Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North developed a 12 stage model of burnout. The following graphic by The Present Psychologist does a great job at conveying each of these.

I don’t know about you, but I can personally identify with several of the stages and it’s scary to see how they can potentially lead down a path to complete mental and physical burnout. I also think it’s interesting that neglecting needs (stage 3) happens so early on. If you check in with yourself regularly you can hopefully halt your burnout journey at that point.

PhDs can be tough but burnout isn’t an inevitability. Here are a few suggestions for how you can look after your mental health and avoid academic burnout.

Overcoming PhD Burnout

Manage your energy levels, maintaining energy levels day to day.

- Eat well and eat regularly. Try to avoid nutritionless high sugar foods which can play havoc with your energy levels. Instead aim for low GI food . Maybe I’m just getting old but I really do recommend eating some fruit and veg. My favourite book of 2021, How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reduce Disease , is well worth a read. Not a fan of veggies? Either disguise them or at least eat some fruit such as apples and bananas. Sliced apple with some peanut butter is a delicious and nutritious low GI snack. Check out my series of posts on cooking nutritious meals on a budget.

- Get enough sleep. It doesn’t take PhD-level research to realise that you need to rest properly if you want to avoid becoming exhausted! How much sleep someone needs to feel well-rested varies person to person, so I won’t prescribe that you get a specific amount, but 6-9 hours is the range typically recommended. Personally, I take getting enough sleep very seriously and try to get a minimum of 8 hours.

A side note on caffeine consumption: Do PhD students need caffeine to survive?

In a word, no!

Although a culture of caffeine consumption goes hand in hand with intense work, PhD students certainly don’t need caffeine to survive. How do I know? I didn’t have any at all during my own PhD. In fact, I wrote a whole post about it .

By all means consume as much caffeine as you want, just know that it doesn’t have to be a prerequisite for successfully completing a PhD.

Maintaining energy throughout your whole PhD

- Pace yourself. As I mention later in the post I strongly recommend treating your PhD like a normal full-time job. This means only working 40 hours per week, Monday to Friday. Doing so could help realign your stress, anxiety and depression levels with comparatively less-depressed professional workers . There will of course be times when this isn’t possible and you’ll need to work longer hours to make a certain deadline. But working long hours should not be the norm. It’s good to try and balance the workload as best you can across the whole of your PhD. For instance, I often encourage people to start writing papers earlier than they think as these can later become chapters in your thesis. It’s things like this that can help you avoid excess stress in your final year.

- Take time off to recharge. All work and no play makes for an exhausted PhD student! Make the most of opportunities to get involved with extracurricular activities (often at a discount!). I wrote a whole post about making the most of opportunities during your PhD . PhD students should have time for a social life, again I’ve written about that . Also give yourself permission to take time-off day to day for self care, whether that’s to go for a walk in nature, meet friends or binge-watch a show on Netflix. Even within a single working day I often find I’m far more efficient when I break up my work into chunks and allow myself to take time off in-between. This is also a good way to avoid procrastination!

Reduce Stress and Anxiety

During your PhD there will inevitably be times of stress. Your experiments may not be going as planned, deadlines may be coming up fast or you may find yourself pushed too far outside of your comfort zone. But if you manage your response well you’ll hopefully be able to avoid PhD burnout. I’ll say it again: stress does not need to lead to burnout!

Everyone is unique in terms of what works for them so I’d recommend writing down a list of what you find helpful when you feel stressed, anxious or sad and then you can refer to it when you next experience that feeling.

I’ve created a mental health reminders print-out to refer to when times get tough. It’s available now in the resources library (subscribe for free to get the password!).

Below are a few general suggestions to avoid PhD burnout which work for me and you may find helpful.

- Exercise. When you’re feeling down it can be tough to motivate yourself to go and exercise but I always feel much better for it afterwards. When we exercise it helps our body to adapt at dealing with stress, so getting into a good habit can work wonders for both your mental and physical health. Why not see if your uni has any unusual sports or activities you could try? I tried scuba diving and surfing while at Imperial! But remember, exercise doesn’t need to be difficult. It could just involve going for a walk around the block at lunch or taking the stairs rather than the lift.

- Cook / Bake. I appreciate that for many people cooking can be anything but relaxing, so if you don’t enjoy the pressure of cooking an actual meal perhaps give baking a go. Personally I really enjoy putting a podcast on and making food. Pinterest and Youtube can be great visual places to find new recipes.

- Let your mind relax. Switching off is a skill and I’ve found meditation a great way to help clear my mind. It’s amazing how noticeably different I can feel afterwards, having not previously been aware of how many thoughts were buzzing around! Yoga can also be another good way to relax and be present in the moment. My partner and I have been working our way through 30 Days of Yoga with Adriene on Youtube and I’d recommend it as a good way to ease yourself in. As well as being great for your mind, yoga also ticks the box for exercise!

- Read a book. I’ve previously written about the benefits of reading fiction * and I still believe it’s one of the best ways to relax. Reading allows you to immerse yourself in a different world and it’s a great way to entertain yourself during a commute.

* Wondering how I got something published in Science ? Read my guide here .

Talk It Through

- Meet with your supervisor. Don’t suffer in silence, if you’re finding yourself struggling or burned out raise this with your supervisor and they should be able to work with you to find ways to reduce the pressure. This may involve you taking some time off, delegating some of your workload, suggesting an alternative course of action or signposting you to services your university offers.

Also remember that facing PhD-related challenges can be common. I wrote a whole post about mine in case you want to cheer yourself up! We can’t control everything we encounter, but we can control our response.

A free self-care checklist is also now available in the resources library , providing ideas to stay healthy and avoid PhD burnout.

Top Tips for Avoiding PhD Burnout

On top of everything we’ve covered in the sections above, here are a few overarching tips which I think could help you to avoid PhD burnout:

- Work sensible hours . You shouldn’t feel under pressure from your supervisor or anyone else to be pulling crazy hours on a regular basis. Even if you adore your project it isn’t healthy to be forfeiting other aspects of your life such as food, sleep and friends. As a starting point I suggest treating your PhD as a 9-5 job. About a year into my PhD I shared how many hours I was working .

- Reduce your use of social media. If you feel like social media could be having a negative impact on your mental health, why not try having a break from it?

- Do things outside of your PhD . Bonus points if this includes spending time outdoors, getting exercise or spending time with friends. Basically, make sure the PhD isn’t the only thing occupying both your mental and physical ife.

- Regularly check in on how you’re feeling. If you wait until you’re truly burnt out before seeking help, it is likely to take you a long time to recover and you may even feel that dropping out is your only option. While that can be a completely valid choice I would strongly suggest to check in with yourself on a regular basis and speak to someone early on (be that your supervisor, or a friend or family member) if you find yourself struggling.

I really hope that this post has been useful for you. Nothing is more important than your mental health and PhD burnout can really disrupt that. If you’ve got any comments or suggestions which you think other PhD scholars could find useful please feel free to share them in the comments section below.

You can subscribe for more content here:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

Minor Corrections: How To Make Them and Succeed With Your PhD Thesis

2nd June 2024 2nd June 2024

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 27th April 2024

Thesis Title: Examples and Suggestions from a PhD Grad

23rd February 2024 23rd February 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

- Help & FAQ

Stress and stress management interventions in higher education students: Promises, Challenges, Innovations

- Clinical Psychology

- APH - Mental Health

Research output : PhD Thesis › PhD-Thesis - Research and graduation internal

- stress management

- university students

- higher education

- meta-analysis

- internet-based interventions

Access to Document

- 10.5463/thesis.316 Licence: CC BY-ND

- Stress and stress management interventions in higher education students - cover Final published version, 54.2 KB

- Stress and stress management interventions in higher education students - toc Final published version, 43.2 KB

- Stress and stress management interventions in higher education students - title_page Final published version, 114 KB

- Stress and stress management interventions in higher education students - thesis_redacted Final published version, 3.2 MB

Persistent URL (handle)

- Copy link address

Embargoed Document

Stress and stress management interventions in higher education students

Final published version, 6.05 MB

Embargo ends: 3/04/25

Fingerprint

- Meta-Analysis Psychology 100%

- Higher Education Psychology 100%

- Stress Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology 100%

- Stress Management Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology 100%

- Health Psychology 75%

- Systematic Review Psychology 75%

- Anxiety Psychology 50%

- Depression Psychology 50%

T1 - Stress and stress management interventions in higher education students

T2 - Promises, Challenges, Innovations

AU - Amanvermez, Yaǧmur

PY - 2023/10/11

Y1 - 2023/10/11

N2 - Stress is becoming a growing concern among young adults. Students in higher education are particularly at risk as they encounter several stressors such as academic pressure, financial adversity, and study/life imbalance. When the demands exceed one`s coping capacity, it can negatively influence mental and physical health. Therefore, this thesis is conducted to investigate stress and stress management interventions in higher education students. Chapter 1 provides a general overview of the concepts of this thesis namely stress, sources of stress in university students, stress management interventions, and Interned-based interventions. Chapter 2 investigates the sources of stress (i.e., financial, health, love life, relationship with family, relationship with people at work/ school, the health of loved ones, other problems of loved ones, and life in general) among students from two universities in the Netherlands, and examines the associations between student status (i.e., international vs. domestic students) and sources of stress. The results of this chapter showed that international students were more likely to experience financial stress and stress related to the health of their loved ones. Chapter 3 presents the findings of the systematic review and meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) investigating the effects of stress management interventions involving a care provider for college students. Results yielded that stress management interventions had moderate effects on stress, depression, and anxiety. Chapter 4 reports the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of self-guided stress management interventions for university students. The overall effects were low-to-moderate. Chapter 5 represents the findings of the systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga, meditation, and mindfulness interventions in university students for stress, depression, and anxiety. Meta-analysis findings yielded moderate effects. Chapter 6 introduces a guided Internet-based stress management intervention (Rel@x) developed for university students with elevated levels of stress and describes the protocol study investigating the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention. Chapter 7 presents the quantitative and qualitative findings of this trial. As a result, students evaluated the intervention as feasible and acceptable. However, high attrition rates and findings from the semi-structured interviews pointed out that intervention should be refined before conducting a large-scale RCT. Lastly, Chapter 8 provides the overarching findings of this thesis alongside clinical and research implications.

AB - Stress is becoming a growing concern among young adults. Students in higher education are particularly at risk as they encounter several stressors such as academic pressure, financial adversity, and study/life imbalance. When the demands exceed one`s coping capacity, it can negatively influence mental and physical health. Therefore, this thesis is conducted to investigate stress and stress management interventions in higher education students. Chapter 1 provides a general overview of the concepts of this thesis namely stress, sources of stress in university students, stress management interventions, and Interned-based interventions. Chapter 2 investigates the sources of stress (i.e., financial, health, love life, relationship with family, relationship with people at work/ school, the health of loved ones, other problems of loved ones, and life in general) among students from two universities in the Netherlands, and examines the associations between student status (i.e., international vs. domestic students) and sources of stress. The results of this chapter showed that international students were more likely to experience financial stress and stress related to the health of their loved ones. Chapter 3 presents the findings of the systematic review and meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) investigating the effects of stress management interventions involving a care provider for college students. Results yielded that stress management interventions had moderate effects on stress, depression, and anxiety. Chapter 4 reports the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of self-guided stress management interventions for university students. The overall effects were low-to-moderate. Chapter 5 represents the findings of the systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga, meditation, and mindfulness interventions in university students for stress, depression, and anxiety. Meta-analysis findings yielded moderate effects. Chapter 6 introduces a guided Internet-based stress management intervention (Rel@x) developed for university students with elevated levels of stress and describes the protocol study investigating the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention. Chapter 7 presents the quantitative and qualitative findings of this trial. As a result, students evaluated the intervention as feasible and acceptable. However, high attrition rates and findings from the semi-structured interviews pointed out that intervention should be refined before conducting a large-scale RCT. Lastly, Chapter 8 provides the overarching findings of this thesis alongside clinical and research implications.

KW - stress, stressmanagement, universiteitsstudenten, hoger onderwijs, internet interventies

KW - stress

KW - stress management

KW - university students

KW - higher education

KW - meta-analysis

KW - internet-based interventions

U2 - 10.5463/thesis.316

DO - 10.5463/thesis.316

M3 - PhD-Thesis - Research and graduation internal

SN - 9789464731651

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 13 November 2019

The mental health of PhD researchers demands urgent attention

You have full access to this article via your institution.

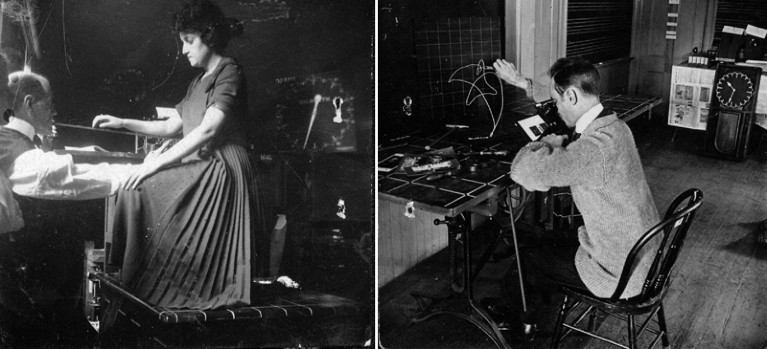

Performance management — captured here in photographs from Frank Gilbreth — has long contributed to ill health in researchers. Credit: Kheel Centre

Two years ago, a student responding to Nature ’s biennial PhD survey called on universities to provide a quiet room for “crying time” when the pressures caused by graduate study become overwhelming. At that time , 29% of 5,700 respondents listed their mental health as an area of concern — and just under half of those had sought help for anxiety or depression caused by their PhD study.

Things seem to be getting worse.

Respondents to our latest survey of 6,300 graduate students from around the world, published this week, revealed that 71% are generally satisfied with their experience of research, but that some 36% had sought help for anxiety or depression related to their PhD.

These findings echo those of a survey of 50,000 graduate students in the United Kingdom also published this week. Respondents to this survey, carried out by Advance HE, a higher-education management training organization based in York, UK, were similarly positive about their research experiences, but 86% report marked levels of anxiety — a much higher percentage than in the general population. Similar data helped to prompt the first international conference dedicated to the mental health and well-being of early-career researchers in May. Tellingly, the event sold out .

How can graduate students be both broadly satisfied, but also — and increasingly — unwell? One clue can be found elsewhere in our survey. One-fifth of respondents reported being bullied; and one-fifth also reported experiencing harassment or discrimination.

Could universities be taking more effective action? Undoubtedly. Are they? Not enough. Of the respondents who reported concerns, one-quarter said that their institution had provided support, but one-third said that they had had to seek help elsewhere.

There’s another, and probably overarching, reason for otherwise satisfied students to be stressed to the point of ill health. Increasingly, in many countries, career success is gauge by a spectrum of measurements that include publications, citations, funding, contributions to conferences and, now, whether a person’s research has a positive impact on people, the economy or the environment. Early-career jobs tend to be precarious. To progress, a researcher needs to be hitting the right notes in regard to the measures listed above in addition to learning the nuts and bolts of their research topics — concerns articulated in a series of columns and blog posts from the research community published last month.

Most students embark on a PhD as the foundation of an academic career. They choose such careers partly because of the freedom and autonomy to discover and invent. But problems can arise when autonomy in such matters is reduced or removed — which is what happens when targets for funding, impact and publications become part of universities’ formal monitoring and evaluation systems. Moreover, when a student’s supervisor is also the judge of their success or failure, it’s no surprise that many students feel unable to open up to them about vulnerabilities or mental-health concerns.

The solution to this emerging crisis does not lie solely in institutions doing more to provide on-campus mental-health support and more training for supervisors — essential though such actions are. It also lies in recognizing that mental ill-health is, at least in part, a consequence of an excessive focus on measuring performance — something that funders, academic institutions, journals and publishers must all take responsibility for.

Much has been written about how to overhaul the system and find a better way to define success in research, including promoting the many non-academic careers that are open to researchers. But on the ground, the truth is that the system is making young people ill and they need our help. The research community needs to be protecting and empowering the next generation of researchers. Without systemic change to research cultures, we will otherwise drive them away.

Nature 575 , 257-258 (2019)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03489-1

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Research management

‘I saw that discrimination wasn’t hearsay or rumours — it really did exist’

Career Q&A 05 JUN 24

Need a policy for using ChatGPT in the classroom? Try asking students

Career Column 05 JUN 24

Why China has been a growing study destination for African students

Nature Index 05 JUN 24

Racing across the Atlantic: how we pulled together for ocean science

Career Feature 03 JUN 24

How I run a virtual lab group that’s collaborative, inclusive and productive

Career Column 31 MAY 24

How I overcame my stage fright in the lab

Career Column 30 MAY 24

China’s big-science bet

China’s research clout leads to growth in homegrown science publishing

Is AI misinformation influencing elections in India?

Comment 05 JUN 24

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Warmly Welcomes Talents Abroad

Qiushi Chair Professor; Qiushi Distinguished Scholar; ZJU 100 Young Researcher; Distinguished researcher

No. 3, Qingchun East Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang (CN)

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital Affiliated with Zhejiang University School of Medicine

Proteomics expert (postdoc or staff scientist)

We are looking for a (senior) postdoc or postdoc-level staff scientist from all areas of proteomics to become part of our Proteomics Center.

Frankfurt am Main, Hessen (DE)

Goethe University (GU) Frankfurt am Main - Institute of Molecular Systems Medicine

Tenured Position in Huzhou University School of Medicine (Professor/Associate Professor/Lecturer)

※Tenured Professor/Associate Professor/Lecturer Position in Huzhou University School of Medicine

Huzhou, Zhejiang (CN)

Huzhou University

Electron Microscopy (EM) Specialist

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: July 5th, 2024 About the Institute Human Technopole (HT) is an interdisciplinary life science research institute, created...

Human Technopole

Post-Doctoral Fellow in Chemistry and Chemical Biology

We are seeking a highly motivated, interdisciplinary scientist to investigate the host-gut microbiota interactions that are associated with driving...

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Harvard University - Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Understanding stress management intervention success: A case study-based analysis of what works and why

--> Boulos, Marina Wasfy Aziz (2019) Understanding stress management intervention success: A case study-based analysis of what works and why. PhD thesis, University of Leeds.

This thesis investigates the process behind stress management interventions (SMIs). This includes the design, implementation and evaluation of interventions (both formative and summative), along with exploring the roles of involved stakeholders. Although there exists a plethora of studies around work-related stress across several disciplines, they are predominantly focused on the effects of stress on individuals, organisations and society, highlighting the various costs which are associated with it. However, studies on SMIs are less common, particularly ones with detailed accounts of the SMI process. As a result, this hinders our understanding of which SMIs work for whom in what context (Biron, 2012), making it difficult for forthcoming studies to benefit from the results. A multiple case study research, of a higher education institute (Russell University) and an Arm’s Length (ALMO) housing association (Bravo City Homes), was conducted to address what the literature has neglected. Specifically, it examined the various steps of the SMI process, highlighting the key roles of the involved stakeholders, while contrasting the effects that context had across two different sectors. This was done through forty semi-structured interviews with relevant stakeholders from both organisations to gain retrospective insight into the SMI processes, understand their role and what they perceived it to be, and to evaluate what helped and hindered the success of SMIs. It was found that giving each step of the research process sufficient attention from each of the relevant stakeholders was key. The lack of communication around who the relevant stakeholders were significantly hindered the interventions. Managers, in particular, were found to be crucial to SMI success by supporting the interventions and enhancing communication. Other stakeholders whose roles were found to be vital were Human Resources and trade unions, which have also been neglected in the literature.

--> Final eThesis - complete (pdf) -->

Filename: Boulos_M_LUBS_PhD_2019.pdf

Embargo Date:

You do not need to contact us to get a copy of this thesis. Please use the 'Download' link(s) above to get a copy. You can contact us about this thesis . If you need to make a general enquiry, please see the Contact us page.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

“How is your thesis going?”–Ph.D. students’ perspectives on mental health and stress in academia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, sustainAbility Ph.D. Initiative at the Eberhard Karls Universität, Tübingen, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Julian Friedrich,

- Anna Bareis,

- Moritz Bross,

- Zoé Bürger,

- Álvaro Cortés Rodríguez,

- Nina Effenberger,

- Markus Kleinhansl,

- Fabienne Kremer,

- Cornelius Schröder

- Published: July 3, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288103

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Mental health issues among Ph.D. students are prevalent and on the rise, with multiple studies showing that Ph.D. students are more likely to experience symptoms of mental health-related issues than the general population. However, the data is still sparse. This study aims to investigate the mental health of 589 Ph.D. students at a public university in Germany using a mixed quantitative and qualitative approach. We administered a web-based self-report questionnaire to gather data on the mental health status, investigated mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety, and potential areas for improvement of the mental health and well-being of Ph.D. students. Our results revealed that one-third of the participants were above the cut-off for depression and that factors such as perceived stress and self-doubt were prominent predictors of the mental health status of Ph.D. students. Additionally, we found job insecurity and low job satisfaction to be predictors of stress and anxiety. Many participants in our study reported working more than full-time while being employed part-time. Importantly, deficient supervision was found to have a negative effect on Ph.D. students’ mental health. The study’s results are in line with those of earlier investigations of mental health in academia, which likewise reveal significant levels of depression and anxiety among Ph.D. students. Overall, the findings provide a greater knowledge of the underlying reasons and potential interventions required for advancing the mental health problems experienced by Ph.D. students. The results of this research can guide the development of effective strategies to support the mental health of Ph.D. students.

Citation: Friedrich J, Bareis A, Bross M, Bürger Z, Cortés Rodríguez Á, Effenberger N, et al. (2023) “How is your thesis going?”–Ph.D. students’ perspectives on mental health and stress in academia. PLoS ONE 18(7): e0288103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288103

Editor: Khader Ahmad Almhdawi, Jordan University of Science and Technology Faculty of Applied Medical Science, JORDAN

Received: March 23, 2023; Accepted: June 20, 2023; Published: July 3, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Friedrich et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The anonymized data set is available at https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.12914 . All code for the analysis can be found at https://github.com/coschroeder/mental_health_analysis .

Funding: We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publishing Fund of University of Tübingen. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Work situations can be demanding and have a profound influence on employees’ mental health and well-being across different sectors and disciplines [ 1 ]. Multiple studies show that the mental health status of people working in academia and especially that of Ph.D. students seems to be particularly detrimental when compared to the public [e.g., 2 , 3 ]. Disorders such as anxiety and depression are on the rise in the general population [ 4 , 5 ]. Multiple studies show that this is even more severe in academia [ 6 – 10 ] and in particular Ph.D. students are affected by mental health problems [ 11 , 12 ]. Worldwide surveys grant support for Ph.D. students’ suboptimal and alarming mental health situations [ 13 , 14 ].

A comprehensive study with more than 2000 participants (90% Ph.D. students, 10% Master students) from over 200 institutions across different countries showed that graduate students were more than six times more likely to experience symptoms of depression and anxiety than the general public [ 2 ]. Furthermore, a global-scale meta-analysis [ 3 ] and several other studies concerned with the mental health of Ph.D. students in different countries, e.g., the United States [ 7 , 9 ], the United Kingdom [ 6 ], France [ 15 ], Poland [ 8 ], Belgium [ 16 ] or Germany [ 11 , 12 ] voice concerns about the mental health situation of Ph.D. students. Recent research conducted in Belgium has consistently found a higher prevalence of mental health problems among Ph.D. students compared to different groups of other highly educated individuals [ 16 ]. In the same study, 50% of the Ph.D. students reported that they suffer from some form of mental health problem, and every third is at risk of a common psychiatric disorder [ 16 ]. A similar picture is forming in Germany. For example, the prevalence of at least moderate depression among doctoral researchers at the Max Planck Society, one of the biggest academic societies in Germany, was between 9.6% and 11.6% higher than in the age-related general population [ 11 ].

Increasing numbers of anxiety and depression among Ph.D. students

Recent studies describe not only a high prevalence but also a rising tendency of mental health issues among Ph.D. students. In a study from 2017, 12% of the respondents reported seeking help for depression or anxiety related to their Ph.D. [ 13 ], while in 2019, the result was even more drastic, as 36% of the respondents reported that having searched for help for those same reasons [ 14 ]. Several studies among doctoral researchers within the Max Planck Society show similar results. For instance, a survey in 2019 showed that the average of the Ph.D. students were at risk for an anxiety disorder and another sample from 2020 provided even more robust support for this claim [ 11 , 12 ]. Furthermore, the mean depression score increased from 2019 to 2020 in both samples [ 11 ].

Risk factors and resources

Given these alarming statistics, several studies addressed risks and resources for increased mental health issues. Other studies have revealed that gender, perceived work-life balance, and mentorship quality are correlated with mental health issues [ 2 , 17 ]. Specifically, female gender [ 17 ] and transgender/gender-nonconforming Ph.D. students are, on average, more likely to suffer from mental health issues [ 2 ]. In contrast, a positive and supportive mentoring relationship or a supervisor’s leadership style, and a good work-life balance are positively associated with better mental health [ 2 , 16 ]. While some authors [ 18 ] reported a negative correlation between the Ph.D. stage and mental health, with students at later stages disclosing greater levels of distress, others [ 16 ] did not find significant differences in this regard. Moreover, another report identified that Ph.D. students’ satisfaction levels strongly correlate with their relationship with their supervisors, number of publications, hours worked, and received guidance from advisors [ 19 ]. Furthermore, several studies showed a positive correlation between job satisfaction [ 20 , 21 ] as well as a negative correlation between job insecurity [ 22 ] and mental health or perceived stress, also in Ph.D. students.

Aim and research questions

Taken together, the alarming findings on the psychological status of Ph.D. students around the globe cannot be denied. However, data on the situation of Ph.D. students in Germany are scarce [ 11 , 12 , 23 ]; thus, comparisons of different universities within a country can hardly be made. However, addressing those differences is particularly relevant since the working conditions, concerning contract types, financial situations or supervision vary strongly among different countries, geographical regions and universities or institutions [ 24 ]. Furthermore, little is known about the reasons for this precarious situation and where exactly the need for action lies [ 25 ]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to conduct a survey among Ph.D. students at a university in the southwest of Germany to assess Ph.D. students’ mental health status. Additionally, the present study also reveals information on the extent of the need for additional support services and pinpoints the specific areas where these services ought to be emphasized. In order to help identify relevant indicators, this investigation provides empirically sound findings on the mental health situation of Ph.D. students in Germany.

Materials and methods

Sample and procedure.

Overall, 589 participants (60.3% female, 0.8% of diverse gender, M Age = 28.8, SD Age = 3.48, range 17–48 years) out of a total of enrolled 2552 Ph.D. students (response rate: 23.1%; actual numbers of Ph.D. students at the University of Tübingen higher as some Ph.D. students are not enrolled) took part in an online survey from October to December 2021. Instructions, items, and scales were all presented in English. Participants could answer the open questions in German or English and were comprised of Ph.D. students across various stages of their Ph.D. at the University of Tübingen without further exclusion criteria. The online questionnaire was sent to Ph.D. students’ email addresses via mailing distribution lists in cooperation with the central institution for strategic researcher development (Graduate Academy) of the University of Tübingen and with Ph.D. representatives of different faculties. Ethics approval was obtained by the “Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Economics and Social Science of the University of Tübingen” and written informed consent was given by the participants.

The distribution of faculty affiliation of the participants was heterogeneous with shares of 61.8% Science, 12.4% Humanities, 11.7% Economics and Social Sciences. These numbers reflect the different sizes of faculties and are roughly aligned with the relative numbers of students (41.7% Science, 24.8% Medicine, 16.2% Humanities, 7.5% Economics and Social Sciences), with a clear underrepresentation of the Medical Faculty. Faculties with less than 20 participants or participants with multiple answers were grouped into one category for further analysis (Others 14.1%, see S1 Table ). 67.9% of the participants were German and in total, 82.9% came from European countries. During data collection, the participants were at different stages of their Ph.D. ranging from 0 to over 130 months with a mean time of two and a half years (30.0 months) of Ph.D. progress.

First, demographic data and background information on the current Ph.D. situation were collected. In a second part, to get a differentiated view, we included different measures to operationalize the mental health status of Ph.D. students. The quantitative questionnaire assessed 1) general health, generalized anxiety disorder, as well as internally reviewed self-generated questions, 2) life and job satisfaction, and quantitative job insecurity, and 3) stressors (institutional and systemic), causes of stress and potential solutions. This study also collected information regarding the degree of participants’ familiarity with the mental health resources available at the university, e.g., points of contacts for counseling, in order to evaluate whether Ph.D. students make use of these services. Moreover, participants were asked to name additional services that they may consider necessary.

General health and stressors.

General health was assessed by two items of the Perceived Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) [ 26 ]. Participants were asked to indicate how frequently they had experienced depressed moods and anhedonia over the past four weeks on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day). Additionally, they were presented with seven items of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) [ 27 ] capturing the severity of various anxiety signs like nervousness, restlessness, and easy irritation on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day). Both scales were used in this combination in a previous study in German higher education [ 28 ]. Furthermore, we included two binary questions on whether the participants are currently in psychotherapy and if they have ever been diagnosed with a mental disorder.

The condensed version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [ 29 ] was used to get the degree of stressful situations in life in the last twelve months or since the start of the Ph.D. [ 30 ]. The response scale ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), the following being a sample item: “… how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?” To check the internal consistency of the four items, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha which was .79.

Job satisfaction and life satisfaction.

Three items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) were used to measure job satisfaction [ 31 ], where a higher mean score indicated higher job satisfaction. A sample item is: “I am satisfied with my job.” Cronbach’s alpha was .86. Additionally, we added one item concerning general life satisfaction [adapted from 32 ] with the same response categories to get a more holistic insight.

Job insecurity.

To assess the fear of losing the job itself, quantitative job insecurity was measured with three items (e.g., “I am worried about having to leave my job before I would like to.”) [ 33 ] on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We calculated a mean score with higher scores indicating higher job insecurity. Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Institutional and systemic stressors.

For institutional stressors, we focused mainly on the role of supervision and included eight questions, four were framed using positive wording and four with negative wording, each with a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all of the time). We summarized these questions in two constructs (positive support/negative support) which had Cronbach’s alphas of .85 and .76, respectively. As for systemic stressors, we included two questions on long-term contracts and on future perspectives, again using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

To cover the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the implemented regulations, we included two questions to evaluate whether the pandemic affected the students’ general situation. On the one hand, participants were asked to pick the statement that best describes the effects of the pandemic in general (“yes, it improved my general situation”, “yes, it worsened my general situation”, “yes, but it neither worsened nor improved my general situation”, “no”), and on the other hand, they were asked to evaluate whether the particular answers provided in this survey had been affected by the pandemic from 1 (very likely) to 5 (very unlikely).

Rating procedure and open answers

Causes of stress and potential solutions..

We included three open-ended questions in the questionnaire to get a deeper understanding of the perceived causes of stress, potential ways to improve mental health, and ways to improve the overall situation of Ph.D. students. The questions were: (1) “What is/are the cause(s) of your stress?” (2) “What would need to change to improve your mental health status?” (3) “What could be done to improve your situation?” Participants could mention as many points as they wanted (without any word limit). To analyze these questions, we built categories by following the model of inductive category development [ 34 ]. Two raters screened the first and last 20 responses in the data set and created categories for reoccurring topics (for a list containing all categories see S5 – S7 Tables). In the next steps, two new raters rated all open answers with the developed categories and added additional categories if needed. Applicable categories were rated with 1 (“category was mentioned”) or 0 (“category was not mentioned”). For example, the following response to question (1) “[My] supervisor is on maternity leave with open end, i.e. I have no one to talk to about my topic and have almost nothing so far […] I feel like I’m not good enough at this, not sure I will be able to succeed–everyone else has other projects and publications except me–no topic-related network” was rated with 1 in the following four categories: supervision (quality & quantity), social integration & interactions (private & professional), self-perception (internal factors), and perceived lack of relevant competences & experience–(sense) of progress and success. The full list of categories and inter-rater reliability as measured by Krippendorf’s Alpha is reported in Table 3 [ 35 ].

Descriptive statistics of work environment and workload

The largest part of the participants (65.5%) was temporarily employed, 12.1% got a scholarship, 7.6% were permanently employed, and 6.5% were not employed at all. The mean for total contract length was 34.3 months, with a range between two and 72 months. About 10.5% of the participants had a contract for only 12 months or shorter. A similar large variation was found in the percentage of employment with a mean of 63%, ranging from 10% to 100% of employment. For workload, we found a mean of 36.0 hours of Ph.D.-related work per week with a standard deviation of 15.6 hours. After taking a closer look at high workloads, we found that 31.3% of the participants work 45 hours or more (21.5% work 50 hours and more) per week. On top of their Ph.D. work, many Ph.D. students work in other jobs, which combined with the hours spent for Ph.D.-related work, summed up to the mean of 44.1 overall working hours per week. A detailed description can be found in S1 Table .

Faculty-wise comparison

In an explorative manner, we compared the mean differences of the most important variables between different faculties. Most of the analyzed variables did not show significant differences. Still, we want to stress that the highly imbalanced sample sizes (see S3 Table ) could lead to false negative outcomes due to the small numbers of participants in some groups. However, we found that the mean job insecurity was significantly different between faculties ( p < .001, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test) with comparable low job insecurity in the faculties of law ( M = 2.10, SD = 1.22) and theology ( M = 2.38, SD = 1.19) and high insecurity in the faculty of humanities ( M = 3.32, SD = 0.91).

In total, 41.9% of the participants stated that their general situation worsened due to the pandemic, while 28.5% stated that the pandemic affected but it neither worsened nor improved their general situation. 33.5% of the participants stated that their responses in this study were “very likely” or “likely” to be affected by the pandemic, with a mean of 2.97 ( SD = 1.26).

General health and stressors

The mean of the sum score for PHQ-2 in our study was 2.32 which is below the cut-off of three for major depression [ 26 ]. Yet, 33.1% of the participants were above the cut-off. For the GAD-7, the sum score for the study’s sample was 8.49. Cut points of 5 might be interpreted as mild, cut points of 10 as moderate and 15 as severe levels of anxiety [ 27 ], which implies a mild risk level for generalized anxiety with the suggestion of a follow-up examination in this sample. When asking for mental disorders, we found that 19.9% of the participants ( n = 99) have already been diagnosed with a mental disorder and 15.5% ( n = 77) are currently in psychotherapy. The sum score for the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) of 7.79 (with Min = 0, Max = 15) was above the total sum score compared to a representative British sample (6.11) [ 36 ] and a representative German community sample (4.79 for PSS-4) [ 37 ]. Job satisfaction of our participants with a total sum score of 10.06 was lower compared to a sum score of 12.79 in a German sample of workers in small- and medium sized enterprises [ 38 ]. The mean score for job satisfaction was 3.35, also lower than in a sample of Ph.D. students in Belgium (3.9) [ 39 ]. Job insecurity was with a total sum score of 8.76 higher compared to the German small- and medium sized enterprises sample (5.67) [ 38 ]. Consistently, more than 80% of the Ph.D. students in our study were worried about the lack of permanent or long-term contracts in academia ( M = 4.25, SD = 1.09; 5 indicating a strong agreement). Nevertheless, around half of the participants (54.5%) believed that having a Ph.D. would help them find a good job ( M = 3.49, SD = 0.97). We found a mean score of 3.48 ( SD = 0.98) for the positive support questions which is above average over response levels. Around 57.1% of the Ph.D. students felt supported by their supervisor “most” or “all of the time”. Around 55.7% felt comfortable when contacting the supervisor for support. The negative support construct was with a mean score of 2.18 below average: 46.7% of the participants had never felt looked down, and 62.6% had never felt mistreated by their supervisor. Nevertheless, 28.6% of the Ph.D. students answered feelings of degradation and 19.1% felt mistreated more than “some of the time”. When it comes to the frequency of the meetings with the supervisor, the mean reported a value of 2.4 laying somewhere between having meetings once a month (2) and at least every three months (3). However, 18.2% reported meeting their supervisor only once every six months or less. For sample items and detailed values see S2 Table .

When we analyzed the relationship between the studied outcomes, we found that all major constructs correlated significantly (see Table 1 ). High correlations occurred between the items of the related PHQ-2 and GAD-7 as well as their connections to the PSS. Understandably, the two institutional support dimensions were highly correlated ( r = -.69).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288103.t001

Regression for perceived stress, depression, and anxiety

To predict potential driving factors for the two more direct mental health measurements, namely depression and anxiety, and for perceived stress, we employed linear regression models with these three constructs as response variables controlling for age and gender. We included relevant risk factors and stressors such as job insecurity, perceived stress, negative support and resources such as job and life satisfaction, and positive support to get a comprehensible overview over predictors. All analyses were carried out in R statistics version 4.1.3.

For depression, significant predictors were job satisfaction (β = -0.1, SE = 0.04, p < .05), life satisfaction (β = -0.3, SE = 0.04, p < .001), perceived stress (β = 0.4, SE = 0.05, p < .001) and negative institutional support (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p < .05, see Table 2 ). The model explained 46.7% of the variance, F (8, 482) = 54.5, p < .01.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288103.t002

For anxiety, all studied variables except job satisfaction and positive support were significant predictors with a variance explanation of 36.0%, F (8, 392) = 29.5, p < .01 (see Table 2 ). Noticeable was the strong influence of perceived stress on anxiety. Specifically, we observed that with an increase of one unit in perceived stress, the level of GAD-7 increased by 2.02 units and was in line with the high correlation ( r = .52, p < .01, Table 2 ).

For perceived stress, we found that job insecurity (β = 0.15, SE = 0.02, p < .01), life satisfaction (β = -0.32, SE = 0.03, p < .01) as well as negative institutional support (β = 0.13, SE = 0.04, p < .01) were significant predictors with a model variance explanation of 42.7%, F (4, 486) = 53.5, p < .01. The detailed results for this regression analysis can be found in S4 Table .

Qualitative answers

In the following, we report the main categories with short sample quotes as well as the mean frequency of the two raters (see Table 3 ; details in S5 – S7 Tables). The inter-rater reliability as indicated by Krippendorff’s alpha for the top five categories of all questions was above α ≥ .67, except for the category Manageable Workload for question MH06_1 (see Table 3 ) with α = .62; CI [0.50; 0.74]. A threshold of .67 is commonly considered as the lower conceivable limit that still allows tentative conclusions [ 40 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288103.t003

Causes of stress.

The question “What is/are the cause(s) of your stress?” was answered by n = 446 participants. To cover the breadth of the responses, we built 18 categories. The most frequently mentioned categories were Workload & Time Pressure (mean rating frequency = 211), Self-Perception ( M = 132.5), Job-Insecurity ( M = 93), Social Integration & Interactions ( M = 91), and Supervision Quality & Quantity ( M = 88.5). The category Workload & Time Pressure includes all responses referring to the amount of work and/or deadlines. The category Self-Perception includes responses that indicate a perceived lack of competences or other personal doubts, concerns, and worries (e.g., “Since I started my Ph.D. I have almost constantly felt stupid”, “feeling like not belonging in academia, lack of self-confidence, feeling of making too little progress”). The category Job Insecurity reflects responses regarding contract length and general uncertainty about future employment (e.g., “scholarship is to be ended”, “Not knowing how things will work out after the PhD”, “Hopelessness of scientific career because there are too few full-time positions”). The category Social Integration & Interactions covers responses regarding the integration and sense of belonging in the work environment (e.g., “not valued by colleagues”, “being socially isolated at work”) as well as social issues in the private life (e.g., “Mostly my personal life, or often the lack thereof”, “problems with parents”). The category Supervision Quality & Quantity was used to capture all supervision-related responses including comments about the lack of support, feedback, frequency of meetings, or supervisors’ interest in the topics (e.g., “no clear communication with supervisor”, “lack of support from supervisor, even gossiping about me behind my back”).

Potential ways to improve the mental health status.

When asked “What would need to change to improve your mental health status?”, the Ph.D. students’ responses ( n = 307) included various topics, some addressing compensation and income-related aspects, others highlighting supportive supervision. Overall, the responses lead to twelve different categories. Most answers referred to Supportive Supervision ( M = 98.5), followed by Job Security/Contract ( M = 59). Sample quotes with respect to supervision are e.g., “more feedback from supervisor or even more interest in my topic” or “more regular support by supervisor”. The category Job Security/Contract contains comments with respect to contract length and aspects for future employment (e.g., “no more worries about not being able to get my contract renewed”). The category Manageable Workload ( M = 56.5) includes all responses around work-life balance (e.g., “having also activities beside work”, “clear work hours”). The fourth category was Compensation & Financial Security ( M = 35) and included all income- and compensation-related aspects of the job (e.g., “Be paid 100% would be a start”, “Get paid for all the time at work”). The category Less Additional Tasks ( M = 27.5) was used to specifically cover responses mentioning the number of additional tasks within the job (“Less work in teaching/work unrelated to PhD”).

Ways to improve the personal situation.

In addition to the previous question, which focused on general ways to improve the mental health status, we asked the Ph.D. students the following question: “What could be done to improve your situation?” Based on the themes and topics mentioned in the responses ( n = 281) we built eleven categories. The categories mentioned the most were Job-Security & Compensation ( M = 85.5), followed by Supportive Supervision ( M = 68), Services and Support System ( M = 39.5), Decrease Pressure to Perform ( M = 39.5), and Manageable Workload ( M = 36). The category Job-Security & Compensation includes responses like “chances of getting a long-term job in academia, not just the three-year programs” or “Fair payment (half of students get 50% others 65% even at the same institute)”. For the category Supportive Supervision “Regular meetings with people who are supportive & have an expertise in my research topic” can serve as a sample quote. The category Services and Support System was built to cover the responses named a solution outside the working group and team, such as “it would be helpful to see a university-based psychologist outside of the regular working hours” or “more courses (or better communications about them) about stress management”. The next category was labeled Decrease Pressure to Perform and included all responses that highlighted a high level of perceived pressure, such as “the performance pressure (every talk at a seminar is a job talk) is a big problem” or “Instead of pressuring academics to publish as much as possible, there should be more focus on the quality instead of the quantity of their articles/publication”. The last category, Manageable Workload , contained answers with respect to the amount of work (e.g., “Normal working hours, having really free-time without having the feeling that I should be working, it should be normal to take all vacation days”).

Summary of the qualitative answers.

With respect to the open answers, it can be summarized that the factors named as causes for stress and the possible solutions cover a wide range of topics. However, there are reoccurring topics across all three questions, such as supervision, workload, and job security. The role of supervision is a reemerging motif in the qualitative content analysis. While the quality and quantity of supervision were seen as a cause of stress, supportive supervision has a positive impact on the mental health status as well as the whole situation of the Ph.D. students. Furthermore, job insecurity was mentioned as an important stressor, while stable contracts and appropriate compensation for the work and fewer extra tasks were also added for improvement. Workload and time pressure were the most often stated causes of stress, followed by self-doubts and worries about not having enough competencies for the job. A manageable workload, fewer additional tasks, and a lower pressure to perform were indicated by the participants as valuable improvements.

Summary of the main findings

The conducted survey investigates the mental health of Ph.D. students at a university in the southwest of Germany and gives insights into what causes stress and mental health disorders and where there is a need for further support services. Our qualitative and quantitative analyses revealed interesting and consistent results on the alarming situation of the mental health of Ph.D. students.

First, our quantitative results revealed that one-third of the participants were above the cut-off for depression which is an indicator of a high risk of depression that should be checked by a health professional. On average, the surveyed Ph.D. students were at a mild risk level for an anxiety disorder. While our study design does not allow us to diagnose mental illnesses, it identifies problems that need to be pursued further. It reveals some unhealthy working conditions and increased risks for mental illnesses. Our qualitative and quantitative results showed consistently that many of the most prominent issues for our study’s participants are personal factors such as perceived stress, life satisfaction and self-doubt, but modulated by structural deficits such as financial and job security as well as workload and time pressure. The quantitative analyses revealed that life satisfaction, perceived stress and negative support are the main predictors for anxiety disorders as well as depression. Additionally, low job satisfaction was a significant predictor of depression and job insecurity for anxiety. Furthermore, we identified job insecurity, life satisfaction as well as negative institutional support as predictors for perceived stress.

Second and besides mental health problems, our quantitative analyses showed how supervision and the work environment played a role in the mental health and general well-being of Ph.D. students. Deficient supervision could affect Ph.D. students’ perceived job insecurity and job dissatisfaction. Although good supervision was not a predictor for satisfaction, being comfortable with contacting the supervisor could lower the perceived stress. This shows the importance of the supervisor-student relationship and highlights the importance of the social work environment, which was also mentioned by study participants in the open-end questions. While the categories in the qualitative analyses mainly served to find recurring themes, they can also be used to distinguish between different levels. Some participants reflected causes of stress on a personal level (e.g., self-perception). In contrast, others set the focus on the supervisor level or working group level, or even on the more structural abstract level of the academic system.

Third, our study does not only investigate the mental health situation of Ph.D. students, but we also analyze how the situation and mental health status could be improved. Many suggestions were straightforward given the results of the causes of stress, i.e., bad supervision should be improved, and a secure income should be guaranteed. However, we were also able to show that Ph.D. students wish to make use of services and support systems that could be provided by the university. Furthermore, less pressure to perform and a manageable workload with fewer additional tasks besides the Ph.D. project might decrease the stress level and improve mental health status.

Overall, detrimental mental health is a known problem in academia, and we show another example of its extent as well as opportunities for improvement at a German university.

Comparison to other studies

Data on Ph.D. students’ situation in Germany are scarce, and we, therefore, perform a broader comparison with Ph.D. students around the world. However, the results of this comparison should be taken with caution as our questionnaire and time of survey conduction are unique. We focus mainly on PHQ-2 [ 26 ] and GAD-7 [ 27 ], for which other studies in Germany during the pandemic showed that–compared to pre-COVID-19 reference values–these measurements were significantly increased [ 41 ]. Two studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic include the same scales [ 41 , 42 ] and reveal similar results for the general population in Germany, while in our later study from October to December 2021, the risk for anxiety and depression is slightly higher. In our study, one-third of the participants (33.1%) was above the cut-off for major depression, compared to the studies in a 1.5-year earlier timeframe, where 14.1% (March to May 2020; n = 15704, 70.7% female gender; 42.6% university education) [ 42 ] and 21.4% (March to July 2020; n = 16918; 69.7% female gender; 42.4% university education [ 41 ] of the participants with diverse occupations were above the cut-off. Furthermore, in our study, 39.2% of the participants were at the mild risk level for anxiety compared to 27.4% of the participants in an earlier study [ 41 ]. This shows the increase in depression and anxiety during the pandemic and even higher numbers in our study compared with the German general population. Nevertheless, compared to a survey at public research universities in the United States from May to July 2020, the number of doctoral students screened for major depressive disorder symptoms with the same measurements PHQ-2 was higher with 36% [ 43 ], indicating high numbers of mental issues in academia in several countries.

While using the same scales and items for job satisfaction and job insecurity, our study showed worse sum scores compared to a sample of employers and employees in small- and medium sized enterprises in Germany (December 2020 to May 2021; n = 828; 53.7% female gender, M = 41.5 years; 38.8% higher education entrance qualification) [ 38 ]. It seems that Ph.D. students have higher job insecurity and job dissatisfaction compared to workers in diverse branches and occupations. This may result from different contract types, as workers, especially in industrial sectors, have long-term contracts. The recurrent factor of time pressure and workload, also mentioned in the open-end questions, is backed up by the raw numbers of the contract types and working hours, which may also lead to job dissatisfaction. Although the mean contract type in our study is 63%, the mean number of hours dedicated to Ph.D. work ( M = 36.0, SD = 15.6 hours) is almost in the range of a full-time position. What is more, the participants reported a total weekly workload ( M = 44.1, SD = 11.4 hours) that exceeds a typical full-time position in Germany [ 44 ]. The discrepancy between Ph.D. work and corresponding contract types results in a mean of 12.1 hours of overwork per week (based on a 38.5-hour full-time contract, which is the standard contract for Ph.D. students in Germany). This is in line with previous studies where the authors found a mean of 12.6 hours of overwork per week for Ph.D. students in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics disciplines in Germany [ 45 ]. However, the authors did not include any further work obligations and corrected for contract types with low percentages, and thus the results are difficult to compare directly. Furthermore, we used gender as a control variable, which turned out to be statistically significant for anxiety and stress. This is in line with related work where the female gender was reported to be higher correlated with mental disorders [ 2 , 17 , 46 , 47 ].

Strengths and limitations

Generalization..

While we aimed for our study to reflect the current situation for Ph.D. students as best as possible, there are points that are limiting the generalization of the results or are beyond the scope of this survey. First, we collected the data between October and December 2021, a time at which the ordinance on protection against risks of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus (“Coronavirus-Schutzverordnung”) [ 48 ] was still in place in Germany and influenced private and working life. About one-third (33.5%) of our study population stated that it is very likely or likely that the pandemic affected their answers. Nonetheless, a pandemic is a situation that can reoccur and is only one more reason to proactively set up a resilient Ph.D. graduation system. Another research group [ 49 ] investigated how mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic and concluded that the pandemic could even be seen as a chance to improve mental health services [ 49 ]. Nevertheless, we would like to point out that generalizing from a mental health study conducted during a pandemic may be difficult.

Overall, around 23% of all Ph.D. students at the University of Tübingen [ 50 ] participated in our study, which is slightly below the response rate in other similar studies [e.g., 16 ]. Considering that university students are very frequently invited to various questionnaires and studies, and given that our survey lasted approximately 20 minutes, it can be argued that the participants were motivated to invest time into their responses. However, our study population remains small compared to the total number of Ph.D. students in Germany. Moreover, we want to emphasize the likely sample bias in our data. We recruited participants mainly via mailing lists and our project therefore probably has especially appealed to people who are already interested in health or aware of mental health issues. However, given our relatively large coverage of almost a quarter of all Ph.D. students at the University of Tübingen, even a selective sample can give us insights into overall tendencies. The transferability of our results to other German universities or even universities in other countries is also not guaranteed as the academic systems can largely differ. Additionally, the results of this study are influenced by the overall living conditions the Ph.D. students experience. As Tübingen is a small town in the southwest of Germany, a comparison to larger cities or other countries might not be viable as the conditions probably differ largely.

Finally, even within one university, the generalization of our results is further limited by the uneven distribution of the participants across faculties. Most participants (61.8%) were from the Science Faculty, which is also the largest department (in terms of the highest total number of students) at the University of Tübingen. This skewness limits the faculty-wise comparisons, and we would expect to find interesting insights into the different graduate programs by conducting detailed comparisons. These differences could not only arise from different academic traditions but also from the highly varying expectations on the scope of a Ph.D. thesis. It follows that more detailed and systematic monitoring and data collection in national and international surveys are needed.

Methodology.

In a cross-sectional study, we investigate the current situation of Ph.D. students. While this is a valid and important instrument to access the current state, it cannot give us information about the dynamic changes in the transition phase between undergraduate studies and the Ph.D. as well as across the Ph.D. [ 51 ]. To track these changes or make comparisons over time, a longitudinal study design or propensity score matching procedures [ 52 ] could give further insights. It is therefore desirable to establish regular surveys and monitoring systems either on a university level or in a national survey to provide information on the impact of undertaken actions and implemented changes. We used a mixed quantitative and qualitative research approach. While this provides information on distinct levels, there are some pitfalls. For example, the open answer categories were defined post-hoc. While this gives the possibility for the participants to express their thoughts freely, it makes a systematic analysis more difficult, and the analysis might be biased by the evaluators. Overall, it is important to summarize and statistically analyze our study results on an overall level, but it must not be forgotten that every person and Ph.D. project is individual.

Implications for research and practice

The overall scarce data, paired with worrisome flashlights on the mental health situation of Ph.D. students in different countries, highlights the need for more systematic monitoring of mental health in academia. For this purpose, standardized as well as domain-specific scales for Ph.D. students need to be established and longitudinal data needs to be collected. This would enable researchers to measure the effect of larger environmental changes (such as the COVID-19 pandemic or economic developments) and to measure the impact of interventions targeted to improve the situation. At the same time, we propose including qualitative measurements to assess unknown variables and the unique situation each Ph.D. student faces. These could also inform the development of additional quantitative measurable constructs to reflect the dynamic situation in academia. Such monitoring systems can either be implemented at the university level to give detailed insights into the situation at a specific university or on a national level to get an overall impression of Ph.D. students’ health issues. Optimally, a survey should be promoted from an independent self-governing institution dedicated to advancing science and research. While the demands for a better mental health situation for Ph.D. students are obvious, systematical and political changes need to be addressed in the research community and in academia.

Our mixed methods research approach allows us not only to find out more about the issues of Ph.D. students but also to draw conclusions about what is needed to improve their situation. However, finding solutions to a recognized problem is not a straightforward task, and complex problems often require a step-by-step solution. Therefore, we assume that more practical implications, which could be indicated by an established monitoring system, will be necessary once the first steps have been taken.

In general, we can group interventions into at least four levels that can influence each other: the Ph.D. students themselves, the supervisors, the universities or research institutions, and the greater political context and academic culture. Building on the responses about potential improvements and additional services, we identified the following practical implications: