Gender attitudes in India: What’s changed and what hasn’t

Writer and professor nivedita menon and founder-director, coro, sujata khandekar, discuss the challenges of shifting gender norms and attitudes in india, and the work that still needs to be done..

And while the last few decades have seen landmark judgements in India that push for greater gender equality, the big question still is: Have gender attitudes really changed in our country?

On our podcast On the Contrary by IDR , we spoke with Sujata Khandekar and Nivedita Menon about how attitudes towards traditional gender roles have shifted in India, the kind of resistance these shifts can bring, and what should be done to further change these changes. Sujata is the founding director of CORO India , one of the country’s foremost organisations in grassroots leadership and activism. Nivedita is a writer and a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, and one of the founders of kafila.online , a collective blog on contemporary politics.

Below is an edited transcript that provides an overview of the guests’ perspectives on the show.

Gender attitudes are changing but not across all domains, and not for all women

Sujata: The process of social change is [such that] sometimes you see the visible outcome, sometimes you don’t. Changes are not happening uniformly to all women and in all domains. This society accepts [the] notion of equality in some domains, while it outrightly rejects it in others.

For example, domestic violence was seen as [the] fate of womanhood. It was so natural that violence was not even seen as violence, it was seen as [a] norm. But [today there is] a significant shift in how women perceive [the] violence happening to them. They understand and realise that it is violence. Our Domestic Violence Act has also given them [a] tool to challenge that violence.

[Another change we see is in] women’s roles and family. No more [are they] confined to [the] private domain within [the] four walls of households. Women are coming out for work [and] for education…

Nivedita: There’s been a shift when it comes to sexuality, queer identities, gender-nonconforming love, gender-nonconforming identities, and so on. There is greater visibility of these issues, and of people who subscribe to these spaces. There is a shift in the way sexual violence is perceived. If you think of the # MeToo [movement], and [how] women speak up about the ways in which they face sexual harassment, there has been a definite shift.

To reiterate what Sujata said, there has been [a] shift but this is not some kind of revolution across the board. There hasn’t been some kind of massive social transformation. There is still violence against poor people; transphobia; violence against trans people, women, Dalits. And even among those whose attitudes have shifted on questions of sexual violence, sexuality, women and professions, there would still be very strong class and caste prejudice and [an] inability to recognise their own caste and class privilege.

There have been a number of important judgements and laws. For example, the judgement that recognised trans people as a third gender, and the reading down of Section 377 . The Domestic Violence Act, which Sujata mentioned, has transformed the nature of the ways in which women feel they should have to be in a marriage…

Such changes threaten social order and are often punished

Nivedita: There is a certain social order based on caste hierarchy, community identities, extreme class inequality, compulsory institution of heterosexual marriage, and the family that emerges or is sanctified by the heterosexual patriarchal marriage. It is this family that will give you your caste identity, your religious community identity; it will tell you where you are in the social system, and give you your privileges, and discrimination. Family is at the base of every single inequality in the modern society in which we live. Now, this family depends on very strict ideas of what is a man and what is a woman. This has biological and cultural connotations.

You would kill your own child, rather than live with your child married to a person of another caste.

In Europe, bodies with both kinds of sexual organs were called hermaphrodites. Now we would say intersex. Those bodies were acceptable and seen as normal and natural until the 17th–18th century—that is when the policing of these bodies starts. In our societies, it starts with the coming in of colonial modernity, but now it’s been naturalised—the idea that all of us are born exclusively male or female, and the idea of endogamy, the idea that marriage should always be only within permitted limits. You can see the kind of anxiety about inter-caste and inter-religious community marriage. The violence…that you would kill your own child, rather than live with your child married to a person of another caste. Also, you will notice the idea that women are being married by men of other religious communities and castes, and that is seen as more dangerous for the family than if the men marry out and bring women from other communities and castes, because that is what the role of the woman is assumed to be—she maintains the identity of the family.

The purity of her uterus is absolutely crucial to this process, because in order to ensure that no man can have sex with her, and possibly impregnate her, except a man of her caste, who has been found for her as her husband, it results in the extreme policing of women. Under these circumstances, there is anxiety about people not conforming to their gender roles, claiming to be other than the gender they were assigned at birth, or not accepting the gender they were assigned at birth, inter-caste marriages, inter-community marriages. There is anxiety because it is about maintaining a certain social order, which retains and fixes caste and class hierarchies, controls women’s sexuality, and ensures property passes from father to his son. All of this requires very strict boundaries for people.

Sujata: All values that we [women] imbibe [since childhood] are inequality, subservience, humiliation, injustice, [and] insults. These values [and] constraints are part of our upbringing, and thus become part of our personality and behaviour. They also lead to some stereotypical expectations the society has for you—how you should behave, what you should and should not say, and so on. So when you try to cross those boundaries, there is bound to be a backlash. And what we have seen always is, society does policing. If you cross [boundaries], they have punishments. So what happens normally, if we see punishment, it creates fear, probably that is also the cost that we pay for this change initially because you have consistent fear of losing your family honour, your near ones, your relatives; your children’s pain; desertion. You’re also punished, physically beaten, raped, thrown out of [the] house when you try to transgress this boundary. Men leaving [their] wives or deserting them is very common, and that is in a way acceptable to society. But if women ask for divorce, or a woman says, I want to stay on my own, then that [is] challenging the stereotypical expectation and the social norm.

One of our friends had a very violent marriage, and decided to stay on her own with her four-year-old son. She was telling us horrifying stories, like how she gets knocks at 2–3 am both from men and women. She says, I know they want to keep vigilance. She has a neighbour, a man who has no wife and has two children. But nobody asked him whether he needs any help, that too at 2–3 am. These are the tools to pressurise and terrorise you…

We talk of the investment that we are doing in changing things, changing gender attitudes, but there is so much investment done in not changing those attitudes, in terms of social norms, practices. That backlash and the mental and physical stress that a woman undergoes is the cost that she pays for challenging the gender norm. The same friend that I was talking about, last year she was a CII Women Exemplar awardee . So if you get the support to cross the boundary of backlash, then [that] trajectory probably has no limit.

Dialogue is crucial if we want to shift gender attitudes

Sujata: Dialogue is a very powerful tool to initiate change and critical thinking for both men and women. [However], the dialogue should be based on equality and parity, communication, mutual empowerment. We [at CORO] are extensively working with men while dealing with violence against women, because we have to bring them as partners on the table—they are part of [the] problem, but also part of the solution.

The first level of dialogue has to be among ourselves on questions of caste and class privilege.

So I would just give you an example. In our work in Muslim-populated communities, we have lots of vibrant women leaders, who were talking about triple talaq . So this maulavi issued a circular in the community, that don’t entertain these women, don’t bring them into your homes, because they are anti-men and anti-religion. That was [the] kind of resistance or opposition that he had, and he didn’t pay any heed in the first communication. But a team of seven–eight leaders, who themselves are divorced, continued the discussion. And I’m so happy to tell you that he is our ardent supporter currently. He’s our fellow, working on constitutional values, where he has come up with a curriculum which sees the similarities and convergences between Quran [and the] Constitution, and he teaches young kids. When I asked him what was the tipping point, he said, your approach—when your team was consistently pressing their point ahead, they made space for me to speak. They tried to understand where I’m also coming from, and then I thought you are not as bad as I was thinking. From there, the dialogue started…

And the laws, they reflect what is going on in the society. But only laws also don’t help, because it is again in the hands of [the] implementer. It is something that needs a mindset shift, and seeing equality as a value in our life. That comes only through dialogue, and not by thrashing each other or taking completely this or that position.

Nivedita: When it comes to dialogue, we have to recognise that even inside the spaces that are supposedly ours, there are a range of differences of opinion:

- The first level of dialogue is with people who share a vision with us. But within that space, there are inequalities of privilege, caste, and class, of who has legitimacy to speak, there are hierarchies of age. So, the first level of dialogue has to be among ourselves on questions of caste and class privilege. And that can be quite bitter and divisive. We have to figure out ways in which that doesn’t happen.

- The second level of dialogue is with people who could be our allies, like the maulavi in Sujata’s case. We could and should reach out to people who may simply be sections that may not have thought through certain things. This again starts from the home—people who may listen, your father, mother, brother, uncles, neighbours, who simply have not thought of an alternative. And they don’t respond violently when you suggest something, but they actually start thinking.

- Now, a third outer circle is of those whose purpose is to maintain a certain social order, a very highly organised right which has control over institutions and structural spaces. Here, when you’re talking about a highly organised project, to transform the country in a particular direction, there you reach the limits of dialogue and conversation, because the response is actual physical violence, or the use of state institutions to silence you. It is the use of coercive institutions like the police, it’s the use of instruments like the law. A private citizen can file a case for sedition against anybody, if they feel that their nationalist sentiments have been hurt. Then, there are very well-organised IT campaigns trolling people. And women particularly face very violent trolling and rape and death threats. When you reach that domain, we don’t have an alternative. But we don’t have any other weapon than our insistence on non-violent protest and non-violent dialogue, which we will keep up and the idea is to isolate that outer circle. The idea is that that middle circle should expand more.

However, structural changes are equally important to disrupt gender norms

Sujata: Structural requirements are providing facilities which are enabling for women—which eases out the burden that is stereotypically hers or her job, and eliminating the restricting factor. We talked about the backlash [you get] when you try and change anything stereotypical. So having very strong support systems in the nearest environment [is important].

There is structural change that is needed in education, because it teaches so much inequality.

There is structural change that is needed in education, because it teaches so much inequality. Right from childhood, most often, we are very reactive to incidents of inequality, violence, and all our actions and reactions are more incidents-based. Work has to be done on mental structures and mental models, because they are so deeply embedded. To get out of this is a challenge for everybody, whether it’s a man, woman, trans, anybody, because that constructs identity.

Nivedita: One structural change is a recognition of the sexual division of labour, and how it produces burdens and hurdles for all women—the normalising of the idea that women are responsible for reproduction, and men are responsible for production in the public domain.

But, of course, most women are also involved in production, but almost no man is involved in reproduction. This is the sexual division of labour. What this does is, at very high levels, for instance, if you’re a CEO, then you have the idea of the glass ceiling, because you voluntarily stepped back from many kinds of work that you could do because of your responsibilities towards your children and the home. As you come lower down in the class hierarchy, there aren’t so many women in public politics, because their responsibilities are so great. [For instance,] the reservation for women in Panchayati Raj institutions—many studies have shown that women are usually very young or much older. In their childbearing and home-running age, they do not enter politics. Women voluntarily clip their wings. If you ask class 12 students about their aims and ambitions—the way boys will speak and the way the girls will speak will be very different. Because girls are already aware of their limitations by the time they’re 17 or 18. Even if girls want a job, they know the kind that will enable them to still be a good wife and mother. Now, when we recognise this, and work towards a campaign of social and state, and employer responsibility for childcare, then that’s it. Just one small thing, that childcare responsibilities cannot continue to be privatised into a nuclear or even joint family households where only the women are doing this work.

So if every employer, from the contractor on the building site to this multinational company, all the way wherever people are employed…there should be childcare facility. Not [just] for women, there should be childcare facilities for all employees… If you think of one small [structural] change, this is a doable thing, it is practical, [and] it can be effective.

You can listen to the full episode here .

- Read about how Indians view gender roles in family and society.

- Read about gender stereotyping in the Indian judiciary system.

- Learn why gender equity requires working with men in power.

Every year the World Economic Forum publishes a Global Gender Gap Report, which looks at gender equality around the world. In 2022, India ranked 135 among 146 nations, which was […]

India Development Review (IDR) is India’s first independent online media platform for leaders in the development community. Our mission is to advance knowledge on social impact in India. We publish ideas, opinion, analysis, and lessons from real-world practice.

If you like what you're reading and find value in our articles, please support IDR by making a donation.

Gender issues in India: an amalgamation of research

Subscribe to global connection, shamika ravi and shamika ravi former brookings expert, economic advisory council member to the prime minister and secretary - government of india nirupama jayaraman nj nirupama jayaraman.

March 10, 2017

Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived . After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress , an independent public policy institution based in India.

The views are of the author(s).

Forty-two years have passed since the United Nations first decided to commemorate March 8 th as International Women’s Day, marking a historical transition in the feminist movement. Gender remains a critically important and largely ignored lens to view development issues across the world. On this past occasion of International Women’s Day 2017, here is an amalgamation of gendered learning outcomes across various crucial themes for public policy in India, emerging from Brookings India’s past research on political economy, financial inclusion and health.

Political Economy

In 2016, India ranked 130 out of 146 in the Gender Inequality Index released by the UNDP. It is evident that a stronger turn in political discourse is required, taking into consideration both public and private spaces. The normalization of intra-household violence is a huge detriment to the welfare of women. Crimes against women have doubled in the period between 1991 and 2011. NFHS data reports that 37 per cent of married women in India have experienced physical or sexual violence by a spouse while 40 per cent have experienced physical, sexual or emotional violence by a spouse. While current policy discourse recommends employment as a form of empowerment for women, data presents a disturbing correlation between female participation in labour force and their exposure to domestic violence. The NFHS-3 reports that women employed at any time in the past 12 months have a much higher prevalence of violence (39-40 per cent) than women who were not employed (29 per cent). The researchers advocate a multi-faceted approach to women’s empowerment beyond mere labour force participation, taking into consideration extra-household bargaining power.

Read more at: “ Beginning a new conversation on Women ”.

Gender inequality extends across various facets of society. Political participation is often perceived as a key factor to rectify this situation. However, gender bias extends to electoral politics and representative governance as well. The relative difference between male and female voters is the key to understanding gender inequality in politics. While the female voter turnout has been steadily increasing, the number of female candidates fielded by parties has not increased. More women contest as independents, which does not provide the cover for extraneous costs otherwise available when they are part of a political party.

However, women also act as agents of political change for other women. In the Bihar elections in 2005, when re-elections were held, the percentage of female voters had increased from 42.5 to 44.5 per cent while those of male voters declined from 50 to 47 per cent in the interim period of eight months. As a direct result, 37 per cent of the constituencies saw anti-incumbency voting. The average growth rate of women voters was nearly three times in those constituencies where there was a difference in the winning party. District-wise disaggregation of voter registration also supports this hypothesis in the case of Bihar indicating the percolation of the winds of change. This illustration proves that women are no longer under the complete control of the men in their family in terms of electoral participation. The situation is only bound to improve from here. With the introduction of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs), vulnerable sections like women now have more freedom of choice in their vote. Further, poll related incidents of violence against women have significantly decreased since the phased introduction of EVMs across multi-level elections in India.

Read more at:

- Interview on Gender Inequality in Politics

- Women voters can tip the scales in Bihar

- Using technology to Strengthen Democracy

Related Content

Shamika Ravi

March 8, 2019

Mudit Kapoor, Deepak Agrawal, Shamika Ravi, Ambuj Roy, S V Subramanian, Randeep Guleria

August 8, 2019

Geetika Dang

September 4, 2019

Extending the conversation to political representation is the next phase in the conversation. Women make up merely 22 per cent of lower houses in parliaments around the world and in India, this number is less than half at 10.8 per cent in the outgoing Lok Sabha. A steady increase in female voter participation has been observed across India, wherein the sex ratio of voters (number of female voters vis-à-vis male) has increased from 715 in the 1960s to 883 in the 2000s. Our studies have shown that women are more likely to contest elections in states with a skewed gender ratio. In the case of more developed states, they seek representation through voting leading to an increase in voter participation.

The situation can be rectified by providing focused reservation for those constituencies with a skewed sex ratio. Reducing the entry costs (largely non-pecuniary in nature – cultural barriers, lack of exposure) for women in order to create a pipeline of female leaders is another solution. These missing women, either as voters or leaders point to the gross negligence of women at all ages.

Read more at: Missing Women in Indian Democracy

Financial Inclusion

In the developing world, women have traditionally been the focus of efforts of financial inclusion. They have proved to be better borrowers (40 per cent of Grameen Bank’s clients were women in 1983. By 2000, the number had risen to 90 per cent) – largely attributed to the fact that they are less mobile as compared to men and more susceptible to peer pressure. However, institutions in microfinance are exposed to the trade-off between market growth and social development since having more female clients lead to the inevitable drip-down of social incentives. As an attempt to overcome this hurdle, a larger role can be played by donors with a gender driven agenda, for the financial inclusion sector will drive the idea further.

Gendered contextualisation of products is highly necessary for microfinance institutions (MFIs) – men and women do not ascribe to choices in a similar fashion. Trends emerging from prior research indicates that when health insurance coverage was held under the MFI sector, by both men and women, women benefited from the coverage only so far as they were the holders and not using spousal status (if their husbands were insured). Thus healthcare seeking behaviour becomes an important factor to be considered in insurance coverage under the MFIs.

The JAM trinity – Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhar, Mobile – can be used to improve financial inclusion from a gender perspective as well. The metrics to consider would be the number of Jan Dhan accounts held by women, percentage of women holding Aadhar cards and access to mobile connectivity for women.

Read more at: A trade-off between Growth and Social Objectives Exists for Microfinance Institutions

In terms of healthcare focusing on women, the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) and National Health Mission are vital to the policy landscape. The JSY has improved maternal healthcare in India through the emphasis on institutional deliveries. Increase of 22 per cent in deliveries in government hospitals, was mirrored by an 8 per cent decline in childbirth at private hospitals and a 16 per cent decline in childbirth at home. The National Health Mission’s ASHA led to greater awareness and education of pregnant women as well as an increase in institutional maternal and neonatal healthcare. Improved infrastructure for maternal and neo-natal has been observed in community hospitals, in addition to the introduction of ambulance services.

A gendered increase in seek care is observed with a large 13 per cent increase in the number of women who report being sick in the last 15 days, driving the overall reportage. Further, an eight per cent decline in rural women seeking private healthcare, has been reported, while a 58 per cent increase in women seeking hospitalization has been reported. Further disaggregated, the data shows a 75.7 per cent increase for rural women seeking healthcare. The overall increase in usage of public hospitals is almost entirely driven by rural women who saw an increase of 24.6 per cent in utilisation of public hospitals over the 10 years (2004-2014). Our results show that the JSY had a significant, positive impact on overall hospitalisation of women in India. It increased the probability of a woman being hospitalised by approximately 1.3 per cent.

Read more at: Health and Morbidity in India

The healthcare sector in India has largely focused on maternal healthcare for women. The importance of research on mental health has been ignored in policy discourse. The significant relationship that mental health bears on violence has also been explored in further research. Every fifth suicide in India is that of a housewife (18 per cent overall) – the reportage of suicide deaths has been most consistent among housewives as a category, than other categories. India is the country with the largest rate of female deaths due to ‘intentional violence’.

Our work on childhood violence shows that girls are twice more likely to face sexual violence than boys before the age of 18. Larger the population of educated females in the country, lesser is the incidence of childhood violence at home – including lesser violent discipline, physical punishment as well as psychological aggression. Additionally, the lifetime experience of sexual violence by girls is strongly correlated with the adolescent fertility rate in a country. Further, a strong relationship is observed between female experience of sexual violence and female labour force participation within a country. The results show that the higher the labour force participation by women in a country, the higher is the incidence of sexual violence against them. This could be indicative of adverse working conditions within labour markets, and the difficulty of access to labour markets by young women in a country.

- Over the Past two decades, every fifth suicide in India is by a housewife

- What Explains Childhood Violence

Related Books

Robert E. Litan, Paul R. Masson, Michael Pomerleano

September 1, 2001

Jack E. Triplett

July 1, 1999

Richard D. Kahlenberg

September 1, 2000

Global Economy and Development

Rahul Tongia, Anurag Sehgal, Puneet Kamboj

Online Only

3:00 am - 4:40 am IST

Saneet Chakradeo

August 18, 2020

About Asian Indian Women: Stereotypes, Fabrications, and Lived Realities

- First Online: 13 July 2017

Cite this chapter

- Hemalatha Ganapathy-Coleman 5

1056 Accesses

2 Citations

Many scholars have emphasized the multiplicity of Indian women, but the need to continue to do so becomes clear when we look at the standard ways in which they are characterized. All too often, Indian women are caricatured as the innocent victims of a uniform “Indian tradition.” Furthermore, although the status of women in India is poor, as seen from several indicators, it is equally true that the status of women is inferior worldwide. Yet, caught up in their certainty that “other” women are abused and miserable, European bourgeois ideas of patriarchy, individualism, womanhood, and feminism are imposed on Indian women, ostensibly to explain their plight. Then, the multicultural narrative of female freedom is inevitably offered as a strategy to liberate them. This chapter offers a multidisciplinary summary of work on Indian women, and traces the sources of widely circulated and pervasive ideas and ideals of Indian womanhood. Against this backdrop, this chapter argues that only by listening to the multivocal and contextualized narratives and visions of personhood of Indian women themselves do we stand a chance of breaking out of the cognitive stranglehold of Western ideas of modernity and articulating indigenous frameworks of Indian womanhood.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and Overview: Indian Indentured Women as Human Agency

Fitting in: The Joys and Challenges of Being an Indian Woman in America

Tagore’s Women Heralding The “New Indian Woman”: A Critique of the Women’s Question in the Nationalist Discourse

Working with children or in the field of child development poses challenges similar to those encountered in working with women. See Balagopalan ( 2011 ) for the growing hegemony of the Convention on the Rights of the Child over defining children and childhood in the international policy discourse.

Taylor makes this claim more broadly about our moral reactions. I use it specifically to refer to the reaction of feminists to Indian women’s alternate rationality.

As Tuhiwai Smith ( 1999 ) and others inform us, the idea of progress as tied to literacy and education can be traced to Western conception of modernity.

In 2004, Karnataka became the first state to pass a minimum wage law, and in 2006, organized by the Stree Jagruti Samiti (Society for Awakened Women), 100,000 women domestic workers struck work, on a national level, for a prolonged period, demanding better conditions.

For a provocative and polemical critique of the sari as a garment, see Poonia ( 2012 ). Worth reading also are the responses that discuss the article and offer sharp rejoinders at http://www.manushi.in/articles.php?articleId=1588&ptype

particularly Vanita’s ( 2012 ) response.

In 1975, the Department of Women and Child Development started crèches and day care centers for children of low-income working and ailing mothers. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) also runs crèches. The quality of care in these crèches leaves much to be desired.

Bhadramahila in Bengal.

These human capabilities, outlined by Nussbaum ( 1995 ), include: being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; good health; being able to avoid pain and have experiences that give pleasure; being able to imagine, think, and reason; being able to have attachments to both other people and other objects; being able to plan one’s own life; living for and with others; living in harmony with nature; enjoying life through laughter, play, and recreation; being able to make choices; and being able to live in one’s own context.

Kishwar’s ( 1990 ) essay “Why I do not call myself a feminist” offers a clear and insightful commentary on the pitfalls of adopting the ideology and concepts of Western feminism willy-nilly in India.

It is also well worth arguing that women’s status in Indian society will not change unless we bring men into the dialogue. This points to the need for socialization of boys into sensitive men (Bhangaokar, personal communication, February 16, 2014).

Abu-Lughod, L. (2013). Do Muslim women need saving? . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Amin, S. (1994). Introduction to William Crooke. In A glossary of North Indian peasant life. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Apffel-Marglin, F., & Marglin, S. A. (Eds.). (1990). Dominating knowledge: Development, culture and resistance . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Balagopalan, S. (2011). Introduction: Children’s lives and the Indian context. Childhood, 18 (3), 291–297.

Article Google Scholar

Berry, K. (2007). Lakshmi and the scientific housewife: A transnational account of Indian women’s development and the production of an Indian modernity. In R. B. S. Verma, H. S. Verma, & N. Hasnain (Eds.), The Indian state and women’s problematic: Running with the hare and hunting with the hounds (pp. 125–162). New Delhi, India: Serials Publications.

Bharat, S. (2003). Women, work and family in urban India: Towards new families? In R. C. Mishra, John W. Berry, & R. C. Tripathi (Eds.), Psychology in human and social development: Lessons from diverse cultures. A festschrift for Durganand Sinha (pp. 155–169). New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Bromet, E., Andrade, L. H., Hwang, I., Sampson, N. A., Alonso, J., de Girolamo, G., de Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., … Kessler, R. C. (2011). Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Medicine, 9 (90). http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/90 .

Chakraborty, K., & Basu, D. (2010). Management of anorexia and bulimia nervosa: An evidence-based review. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52 (2), 174–186.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Channa, S. M. (2007). The “ideal Indian woman”: Social imagination and lived realities. In K. K. Misra & J. H. Lowry (Eds.), Recent studies on Indian women (pp. 37–52). Jaipur & New Delhi, India: Rawat Publications.

Channa, S. M. (2013). Gender in South Asia: Social imagination and constructed realities . New Delhi, India: Cambridge University Press.

Chatterjee, P. (1989). The nationalist resolution of the women’s question. In K. Sangari & S. Vaid (Eds.), Recasting women: Essays in colonial history (pp. 233–253). New Delhi, India: Kali for Women & Book Review Literary Trust.

Das, V. (1988). Femininity and the orientation to the body. In K. Chanana (Ed.), Women: Explorations in gender identity (pp. 193–207). New Delhi, India: Orient Longman.

Datta, S. (2000). Globalisation and representations of women in Indian cinema. Social Scientist, 28 (3/4), 71–82.

Dernè, S. (2000). Male Hindi filmgoers’ gaze: An ethnographic interpretation. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 34 (2), 243–269.

Dhruvarajan, V., & Vickers, V. D. J. (Eds.). (2002). Gender, race and nation: A global perspective . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Flueckiger, J. B. (2006). In Amma’s healing room: Gender and vernacular Islam in South India . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Ghosh, P., Arah, O. A., Talukar, A., Sur, D., Babu, G. R., Sengupta, P., et al. (2011). Factors associated with HIV infection among Indian women. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 22 (3), 140–145.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Government of India. (2011). Provisional population totals: India: Census 2011 . http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/indiaatglance.html

Government of India. (2005). Protection of women from domestic Violence Act . New Delhi, India: Government of India.

Karlekar, M. (2003). Domestic violence. In V. Das (Ed.), The Oxford India companion to sociology and social anthropology (Vol. 2, pp. 1127–1157). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Kishwar, M. (1990). Why I do not call myself a feminist. Manushi, 61, 2–8.

Kishwar, M. (1999). Off the beaten track: Rethinking gender justice for Indian women . New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Kumar, U. (2001). Indian women and work: A paradigm for research. In A. K. Dalal & G. Misra (Eds.), New directions in Indian psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 366–385). New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Kurtz, S. N. (1992). All the mothers are one: Hindu India and the cultural reshaping of psychoanalysis . New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Lamb, S. (1997). The making and unmaking of persons: Notes on aging and gender in North India. Ethos, 25 (3), 279–302.

Lamb, S. (2000). White saris and sweet mangoes: Aging, gender and body in North India . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory . Oxford, UK & New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mammen, P., Russell, S., & Russell, P. S. (2007). Prevalence of eating disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity among children and adolescents. Indian Pediatrics, 44, 357–359.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mayo, K. (1927). Mother India . New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Menon, N., & Johnson, M. P. (2007). Patriarchy and paternalism in intimate partner violence. In K. K. Misra & J. H. Lowry (Eds.), Recent studies on Indian women (pp. 171–195). Jaipur & New Delhi, India: Rawat Publications.

Menon, U. (2002). Neither victim nor rebel: Feminism and the morality of gender and family life in a Hindu temple town. In R. Shweder, M. Minnow, & H. R. Markus (Eds.), Engaging cultural differences: The multicultural challenge in liberal democracies (pp. 288–308). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Menon, U. (2013). Women, wellbeing, and the ethics of domesticity in an Odia Hindu temple town . New York, NY: Springer.

Menon, U., & Shweder, R. A. (1998). The return of the “white man’s burden”: The moral discourse of anthropology and the domestic life of Hindu women. In R. A. Shweder (Ed.), Welcome to middle age (and other cultural fictions) . Chicago, IL & London: University of Chicago Press.

Minturn, L. (1993). Sita’s daughters: Coming out of purdah: The Rajput women of Khalapur revisited . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mohanty, S. (2007). Advice to housewives: ‘Conduct book’ tradition in Orissa. In K. K. Misra & J. H. Lowry (Eds.), Recent studies on Indian women (pp. 53–62). Jaipur & New Delhi, India: Rawat Publications.

Nelasco, S. (2010). Status of women in India . New Delhi, India: Deep & Deep Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Nussbaum, M. (1995). Human capabilities, female human beings. In M. Nussbaum & J. Glover (Eds.), Women, culture and development: A study of human capabilities (pp. 61–104). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Obeyesekere, G. (1985). Depression, Buddhism, and the work of culture in Sri Lanka. In A. Kleinman & B. Good (Eds.), Culture and depression (pp. 134–152). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Parameswaran, R., & Cardoza, K. (2009). Melanin on the margins: Advertising and the cultural politics of fair/light/white beauty in India. Journalism and Communication Monographs, 11 (3), 213–274.

Patel, T. (Ed.). (2007). Sex selective abortion in India: Gender, society and new reproductive technologies . New Delhi, India: Sage Publications Ltd.

Poonia, M.S. (2012). Political economy of the sari. Manushi. http://www.manushi.in/articles.php?articleId=1585&ptype=

Raheja, G. G. (1994). Women’s speech genres, kinship and contradiction. In N. Kumar (Ed.), Women as subjects: South Asian Histories (pp. 49–80). Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Raheja, G. G., & Gold, A. G. (1994). Listen to the heron’s words: Reimagining gender and kinship in North India . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Raheja, G. G. (2010). ‘A splendid thing for the empire’: Some reflections on ethnography and entextualization in colonial India. In K. A. Leonard, G. Reddy, & A. G. Gold (Eds.), Histories of intimacy and situated ethnography (pp. 253–298.). New Delhi, India: Manohar.

Ramabai, P. (1887). The high-caste Hindu woman . New York, NY: Fleming H. Revell.

Raman, S. A. (2009). Women in India: A social and cultural history (Vols. 1 and 2). Santa Barbara, CA, Denver, CO, & Oxford, UK: Praeger.

Ray, S. (2000). Engendering India: Woman and nation in colonial and postcolonial narratives. Durham, NC, & London: Duke University Press.

Sangari, K., & Vaid, S. (Eds.). (1989). Recasting women: Essays in colonial history . New Delhi, India: Kali for Women.

Sarkar, S. (1985). The women’s question in nineteenth century Bengal. In K. Sangari & S. Vaid (Eds.), Women and culture (pp. 157–172). Bombay, India: SNDT University.

Sen, A. (1989). Development as capability expansion. Journal of Development Planning, 19, 41–58.

Sen, A. (1995). Gender inequality and theories of justice. In M. C. Nussbaum & J. Glover (Eds.), Women, culture and development: A study of human capabilities (pp. 259–273). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom . New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf Inc.

Seymour, S. C. (1999). Women, family, and child care in India: A world in transition . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Shweder, R. A. (1985). Menstrual pollution, soul loss, and the comparative study of emotions. In A. Kleinman & B. Good (Eds.), Culture and depression (pp. 182–215). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Shweder, R. A. (2012). Relativism and universalism. In D. Fassin (Ed.), A companion to moral anthropology (pp. 85–102). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Sinha, M. (2006). Specters of Mother India: The global restructuring of an empire. Durham, NC, & London: Duke University Press.

Solomon, S., Buck, J., Chaguturu, S. K., Ganesh, A. K., & Kumarasamy, N. (2003). Stopping HIV before it begins: Issues faced by women in India. Nature Immunology, 4, 719–721.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). Urbana, Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Spivak, G. (1990). Questions of multiculturalism. In S. Harasayam (Ed.), The post colonial critic: Interviews, strategies, dialogues (pp. 59–60). New York, NY: Routledge.

Srinivasan, B. (2007). Negotiating complexities: A collection of feminist essays. New Delhi, India & Chicago, IL: Promilla & Co., Publishers & Bibliophile South Asia.

Srinivasan, T. N., Suresh, T. R., & Jayaram, V. (1998). Emergence of eating disorders in India: Study of eating distress syndrome and development of a screening questionnaire. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 44 (3), 189–198.

Tagore, S. (2013). Representation of women in Indian cinema and beyond. In 19th Justice Sunanda Bhandare Memorial Lecture. New Delhi, India: India International Centre (IIC).

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of the modern identity . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, P. (1964). Indian women through the ages: A history of the position of women and the institutions of marriage and family in India from remote antiquity to the present day . Bombay, India: Asia Publishing House.

Trawick, M. (1992). Notes on love in a Tamil family . Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Trawick, M. (2003). The person beyond the family. In V. Das (Ed.), The Oxford Indian companion to sociology and social anthropology (Vol. 2, pp. 1158–1178). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples . London, New York: Zed Books Ltd.

Vanita, R. (2012). The sari: A garment for all seasons. Manushi. Retrieved from http://www.manushi.in/articles.php?articleId=1595&ptype

Vatuk, S. (2008). Islamic feminism in India: Indian Muslim women activists and the reform of Muslim personal law. Modern Asian Studies. Special Issue, Islam in South Asia, 42 (2, 3), 489–518.

Vatuk, S. (2002). Older women, past and present, in an Indian Muslim family. In S. Patel, J. Bagchi, & K. Raj (Eds.), Thinking social science in India: Essays in honour of Alice Thorner (pp. 247–263). New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Vatuk, S. (2001). ‘Where will she go? What will she do?’ Paternalism toward women in the administration of Muslim personal law in contemporary India. In G. J. Larson (Ed.), Religion and personal law in secular India: A call to judgment (pp. 226–238). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Vatuk, S. (1987). Power, authority and autonomy across the life course. In P. Hocking (Ed.), Essays in honor of David G. Mandelbaum (pp. 23–44). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Verma, H. S. (2007). India’s country reports on CEDAW: Separating facts from fiction in the “history” of women’s empowerment written by the Indian politico-administrative class. In H. S. Verma, N. Hasnain, & R. B. S. Verma (Eds.), The Indian state and women’s problematic: Running with the hare and hunting with the hounds (pp. 273–333). New Delhi, India: Serials Publications.

World Bank. (2012). HIV/AIDS in India . Retrieved January 10, 2014, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/07/10/hiv-aids-india

World Health Organization. (2016). Violence against women. Intimate partner and sexual violence against women . Retrieved May 1, 2016, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/

Suggested Readings and Resources for Further Study

Government of India. (2005). Protection of women from Domestic Violence Act . New Delhi, India: Government of India.

Download references

Acknowledgements

My gratitude to Usha Menon for generously pointing me to some of the literature around the topic. Sincere thanks are also due to Rachana Bhangaokar for her valuable critical comments on a draft of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto, Erindale Hall, 3359 Mississauga Road, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada

Hemalatha Ganapathy-Coleman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hemalatha Ganapathy-Coleman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Independent Scholar, Oak Park, California, USA

Carrie M. Brown

Department of Psychology, St. Francis College, Brooklyn, New York, USA

Uwe P. Gielen

Department of Psychology, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA

Judith L. Gibbons

Department of Clinical Psychology, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA

Judy Kuriansky

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Ganapathy-Coleman, H. (2017). About Asian Indian Women: Stereotypes, Fabrications, and Lived Realities. In: Brown, C., Gielen, U., Gibbons, J., Kuriansky, J. (eds) Women's Evolving Lives. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58008-1_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58008-1_3

Published : 13 July 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-58007-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-58008-1

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- +44 0330 027 0207

- +1 (818) 532-6908

- [email protected]

- e-Learning Courses Online

- You are here:

What are Common Stereotypes About India?

A vast and vibrant country, India and Indian culture attract many stereotypes.

Although there might be a little truth in some, very few of these stereotypes are rooted in reality.

Stereotypes also tend to say something about the person, or people, holding them.

It's crucial for all us of to analyze and address the stereotypes we have of others.

By removing these misconceptions and twisted truths, it will help you to fully appreciate the richness of a culture and society; in this instance, India.

Here, we're going to look at 10 of the most common stereotypes we hear about India through our cross-cultural training programmes.

DON'T MISS THE FREE SAMPLE OF OUR ELEARNING COURSE ON INDIAN CULTURE AT THE END!

10 Stereotypes About India We Frequently Hear in Training!

1. indian people cannot speak good english.

Indian people tend to have great English. Why? Because English is the second official language of India and is widely spoken across the country.

The majority of schools across India teach students English right from the start of their formative years which means that it is possible to navigate the country using English alone and with no knowledge of any Indian language.

However, it is important to acknowledge that literacy levels in India are very low which means that higher standards of English tend to be concentrated within those who are educated and working professionals. At the same time, with the influx of Western influences – mainly through the media – into the Indian subcontinent, English references are spreading throughout the different Indian classes.

2. “Thank you kindly, please come again!”

In continuation with the point above comes the issue of the Indian accent, which has been particularised, stereotyped and exaggerated by comedians and the media.

It must be acknowledged that English is not the first language of the majority of Indian people , and that while travellers will often come across the distinct ‘Indian action’ at play, all Indians do not have the same, generalized accent.

In fact, there are distinct shifts in accents and ways of speaking across the many Indian regions. The comical generalization of the Indian accent is a sore point for many who are continuing to learn and improve their language. Be assured, imitations of Apu from the Simpsons will not be appreciated when interacting with Indian nationals.

Education is a big deal in India with many parents putting emphasis on gaining qualifications in order to secure proper careers.

Photo taken in Bengaluru, India by Nikhita S on Unsplash

3. Indians are uneducated

While literacy levels in India, and especially those of women, are not very high, it is important to remember that in a country with a population as high as India’s, it is inaccurate to make generalized assumptions about the entire nation.

The idea that Indians are uneducated is very inaccurate, and education is in fact held in high regard. There are hundreds of thousands of schools across the country, with officially recognized education systems varying from region to region.

Doctors and engineers top the list of professions in India, and MAs, MBAs and PhDs are common qualifications. The university system in India is extremely competitive, with the entry qualifications for some starting at 100%.

4. Indians are poor

There is a commonly held perception that all Indians are poor which is furthered by media portrayals of the country, as seen through the movie Slumdog Millionaire.

While it is true that a major proportion of the Indian populace lives under the poverty line and that there are many beggars within the nation and highly visible slums and shantytowns, this is not the case for the entire nation.

India holds a significant portion of the world’s richest people and there are a large number of Indian nationals who are billionaires – both within the country and abroad.

5. The ‘real India’ is dirty and chaotic

Many travellers come to India for the ‘real Indian experience’, which they associate with dirt, chaos, spontaneity, and confusion.

They live frugally: they eat cheap food, live in cheap hostels, don themselves in traditional Indian clothing and use public transport in an attempt to live the way ‘real Indians’ do.

By doing so, they overlook the huge presence of internationally renowned luxury hotels, shopping malls and designer stores, nightclubs, bars, and restaurants, which are becoming increasingly synonymous with the ‘new’ Indian society. This notion connects to the point preceding this one.

The many dichotomies in India – between the rich and the poor, the West and the East, the traditional and the modern – are highlighted through the dualities of Indian society, and this must be accepted and appreciated.

Believe it or not, pizza is extremely popular in India.

Photo by Shourav Sheikh on Unsplash

6. Indians only eat curry

Indian food abroad has become synonymous with curry, and this is very inaccurate as Indian food is multi-faceted, diverse, and expanses much more than a generic curry.

Indeed, curry is eaten by many in the country – but this statement itself is very vague and incorrect because there are numerous types of curries, in terms of the ingredients they use and the flavours they contain.

Finding ‘international’ cuisines from Chinese to Thai to Mexican, French and American in India is very easy in metropolitan cities, albeit difficult in smaller towns. It already hosts international chains like McDonald's, KFC, Subway, Costa Coffee, and Starbucks, and more are likely to appear in India in the years to come.

7. Indians all speak Hindu

Hindu is the religion , and Hindi is the language.

Due to the sheer diversity and size of India, there are many languages that are spoken and practised in the Indian Union.

Many schools in India – especially those in the South and the East – give precedence to their own languages, thereby not teaching Hindi. Hindi in its most preserved form is spoken largely in North India and is likely to be a second or third language for people in other regions.

If you want to hear some of the linguistic variety, plus how people use 'Hinglish', in India, then watch some TV!

Click here to check out the 3 best Indian shows on Netflix!

8. Indian women are subordinate to men

This stereotype is not completely untrue. In Indian society, gender is extremely hierarchical and favours men over women.

This is not unusual for a developing country and must be looked at in that context. Indian society is largely patriarchal and women are expected to be subordinate to their male counterparts. This is reflected in the skewed sex ratio and literacy rates of the country, which seriously disadvantage the female population.

Traditionally, women were expected to be the carers of their family, mothers and wives, before any other occupation. However, in recent times, this idea is starting to slowly crack, though largely in the upper and middle classes. More women are attending university and going on to hold jobs post-graduation. An increasing number of influential businesspeople in corporations and otherwise are also women.

As a result, more and more women prefer to achieve a certain degree of financial independence before marrying, settling down, and having children. Notably, India has also had a female president – the same came cannot be said of many other countries in the West.

For many Hindus, the cow is a sacred animal. Its horns symbolize the gods, its legs, the ancient Hindu scriptures or the "Vedas" and its udder, the four objectives of life (wealth, desire, righteousness and salvation).

Photo by Monthaye on Unsplash

9. Cows roam the streets of India

The notion of holy cows in India is one that is laden with a lot of curiosity and this stereotype is in fact very accurate!

When in India, you will see a large number of cows – both in farms and fields and on roads and beaches. One reason for the stray cows on the streets is due to the fact that they often wander away from their herds when their owners are transporting them from one locality to another, thus rendering them homeless and on the streets.

These cows are not dangerous, but it is not advisable to approach them or touch them because – despite living in the constant presence of humans and human activity – they may attack you and be infected with disease.

10. Indians worship millions of Gods

Ancient Hindu scriptures have revealed that the religion encompasses the worship of 330 million Gods!

Whilst this is true, it is important to remember that Hinduism is not a polytheistic religion – that is, it speaks of one God.

The millions of Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu religion are in fact perceived to be representatives and avatars of the one supreme God – Brahman. So, the answer to the question of the true number of Hindu Gods and Goddesses is fluid and depends on who is asked.

Take a Course About Indian Culture

If you would like to find out more about India and Indian culture, then enrol on our India Cultural Awareness Training e-Learning course which has been developed by Indian culture and business professionals and is jam-packed with essential tips, guidance, case studies and quizzes.

CLICK HERE TO SEE A SAMPLE OF THE COURSE

You may also be interested in the following:

- What do Google Searches Tell us about Indian Culture?

- Inside Indian Culture - Tips when doing Business in India

- Why India is becoming a Top Expat Destination

- What is the Negotiation Style in India?

Main Photo by Fares Nimri on Unsplash

Related Posts

Indian culture and business etiquette, 10 taboos to avoid when doing business in india, culture shock in brazil: a foreigner’s guide to doing business.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://www.commisceo-global.com/

34 New House, 67-68 Hatton Garden, London EC1N 8JY, UK. 1950 W. Corporate Way PMB 25615, Anaheim, CA 92801, USA. +44 0330 027 0207 or +1 (818) 532-6908

34 New House, 67-68 Hatton Garden, London EC1N 8JY, UK. 1950 W. Corporate Way PMB 25615, Anaheim, CA 92801, USA. +44 0330 027 0207 +1 (818) 532-6908

Search for something

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society

- 1. Views on women’s place in society

Table of Contents

- 2. Son preference and abortion

- 3. Gender roles in the family

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

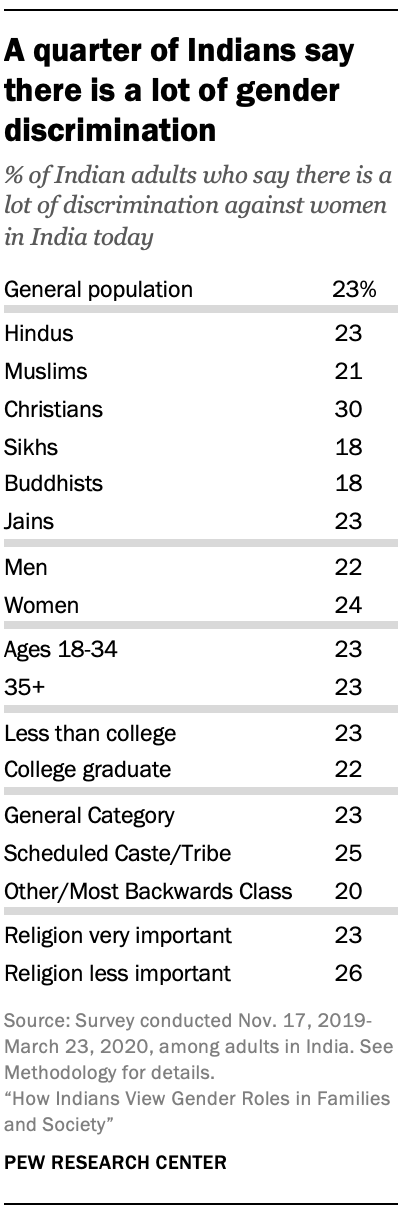

About a quarter of Indians (23%) say there is “a lot of discrimination” against women in their country. And 16% of Indian women reported that they personally had faced discrimination because of their gender in the 12 months before the 2019-2020 survey.

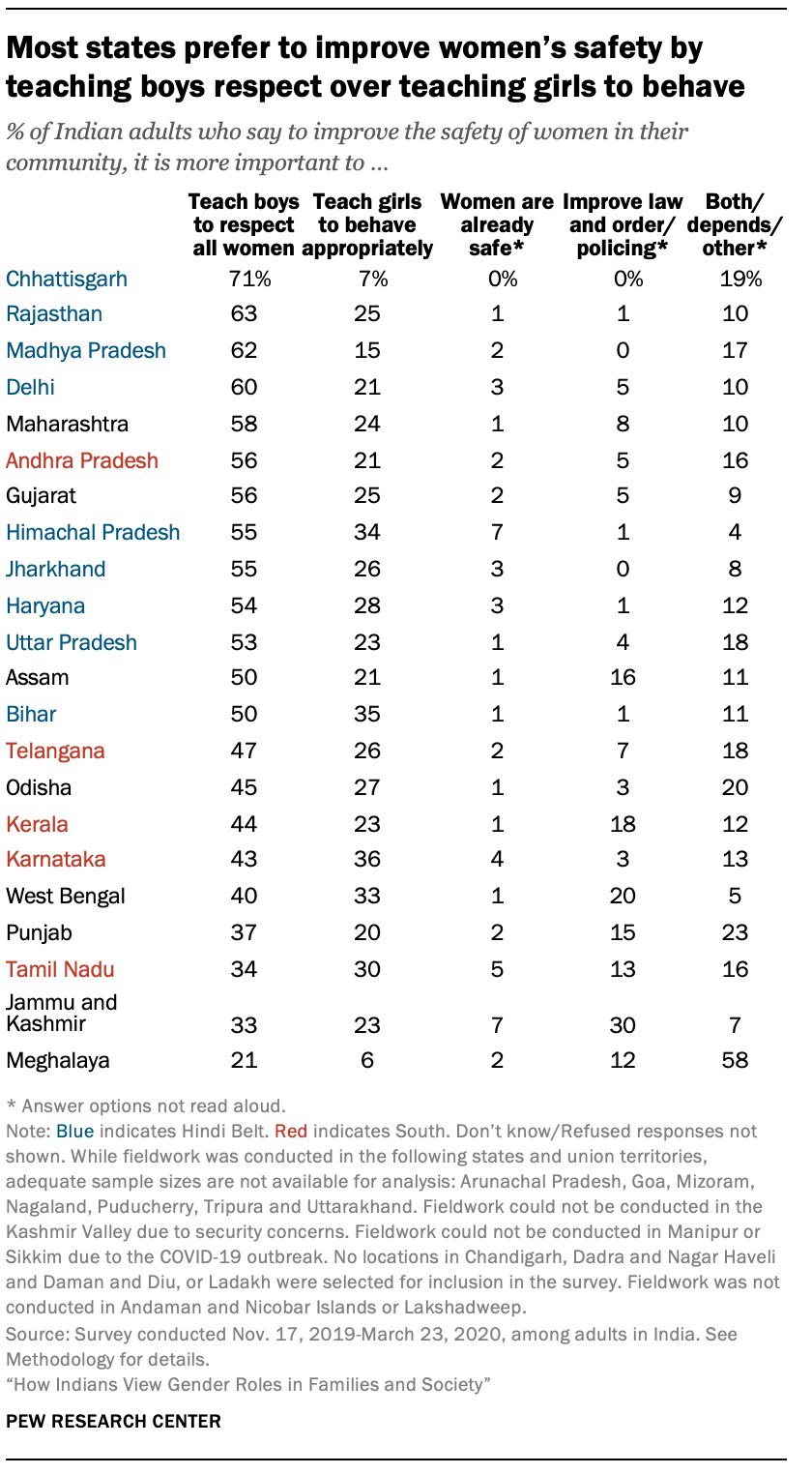

In addition, three-quarters of adults see violence against women as a very big problem in Indian society. To improve women’s safety, about half of Indian adults (51%) say it is more important to teach boys to “respect all women” than to teach girls to “behave appropriately.” But roughly a quarter of Indians (26%) take the opposite position, effectively placing the onus for violence against women on women themselves.

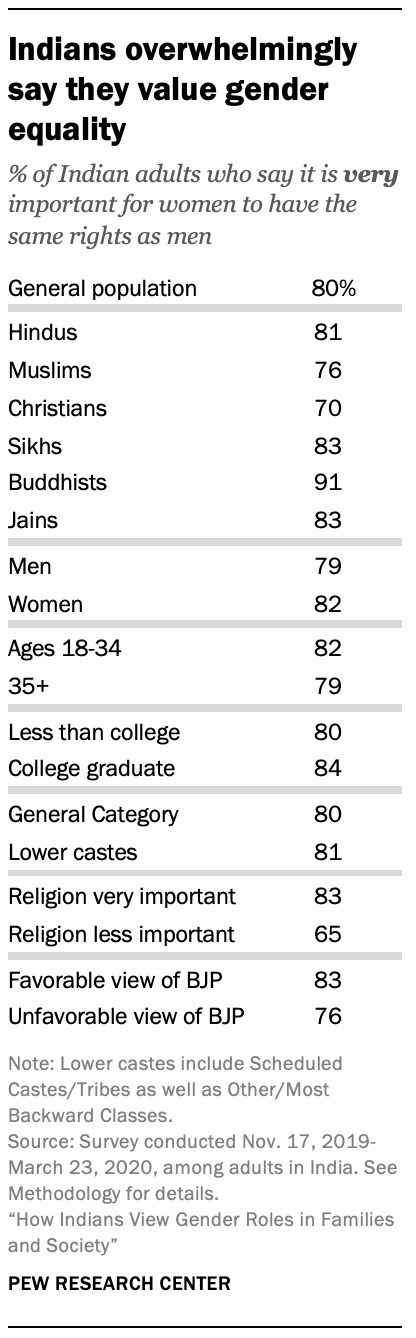

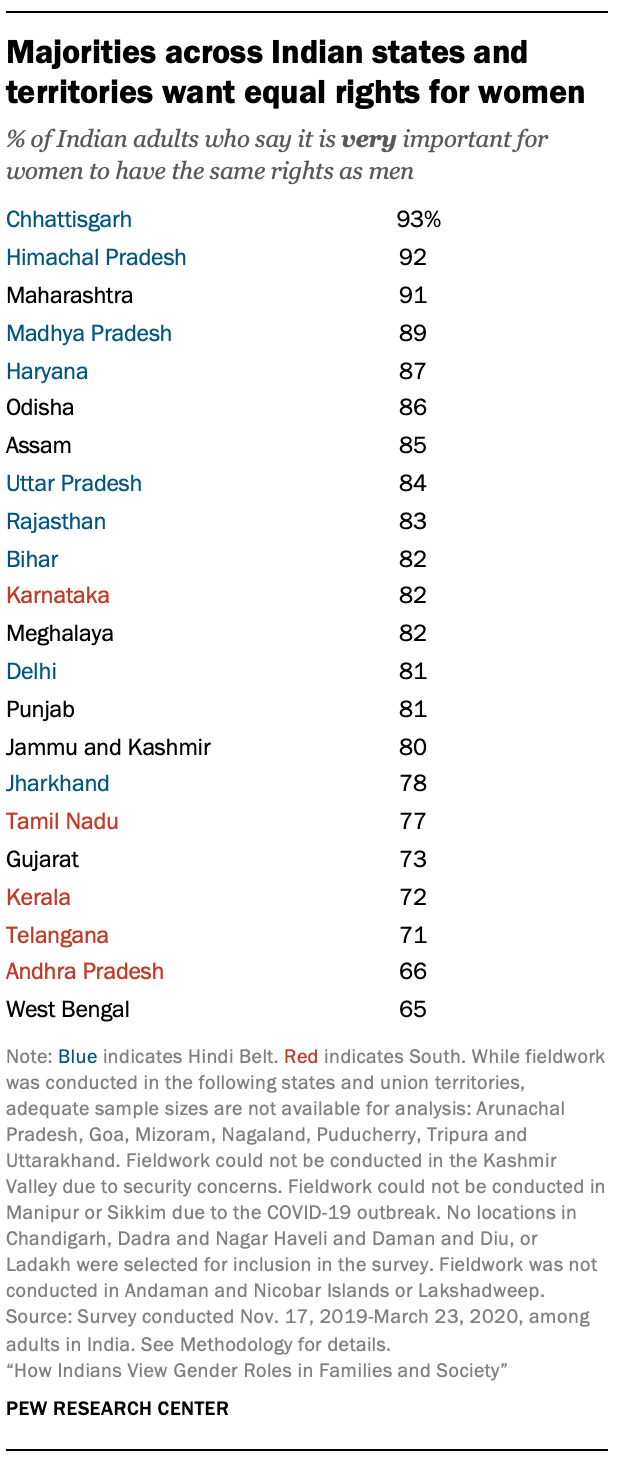

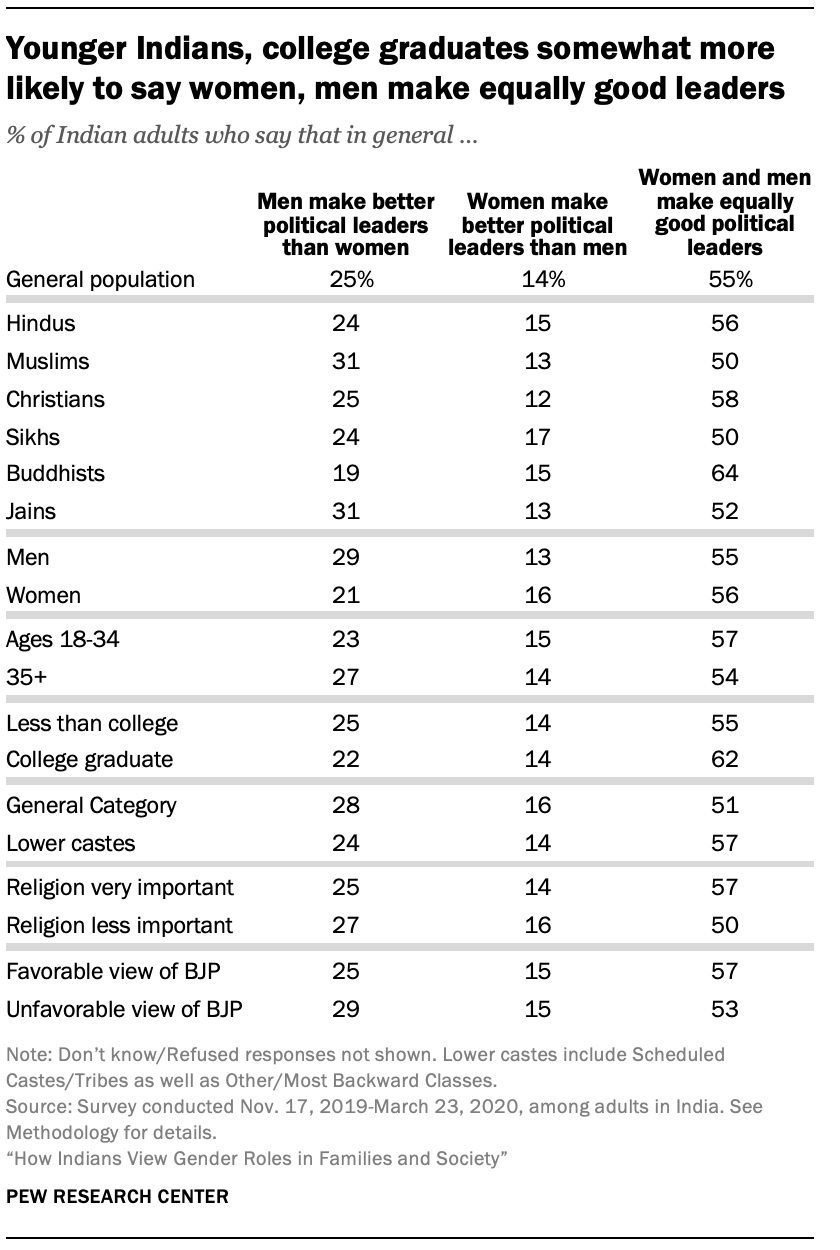

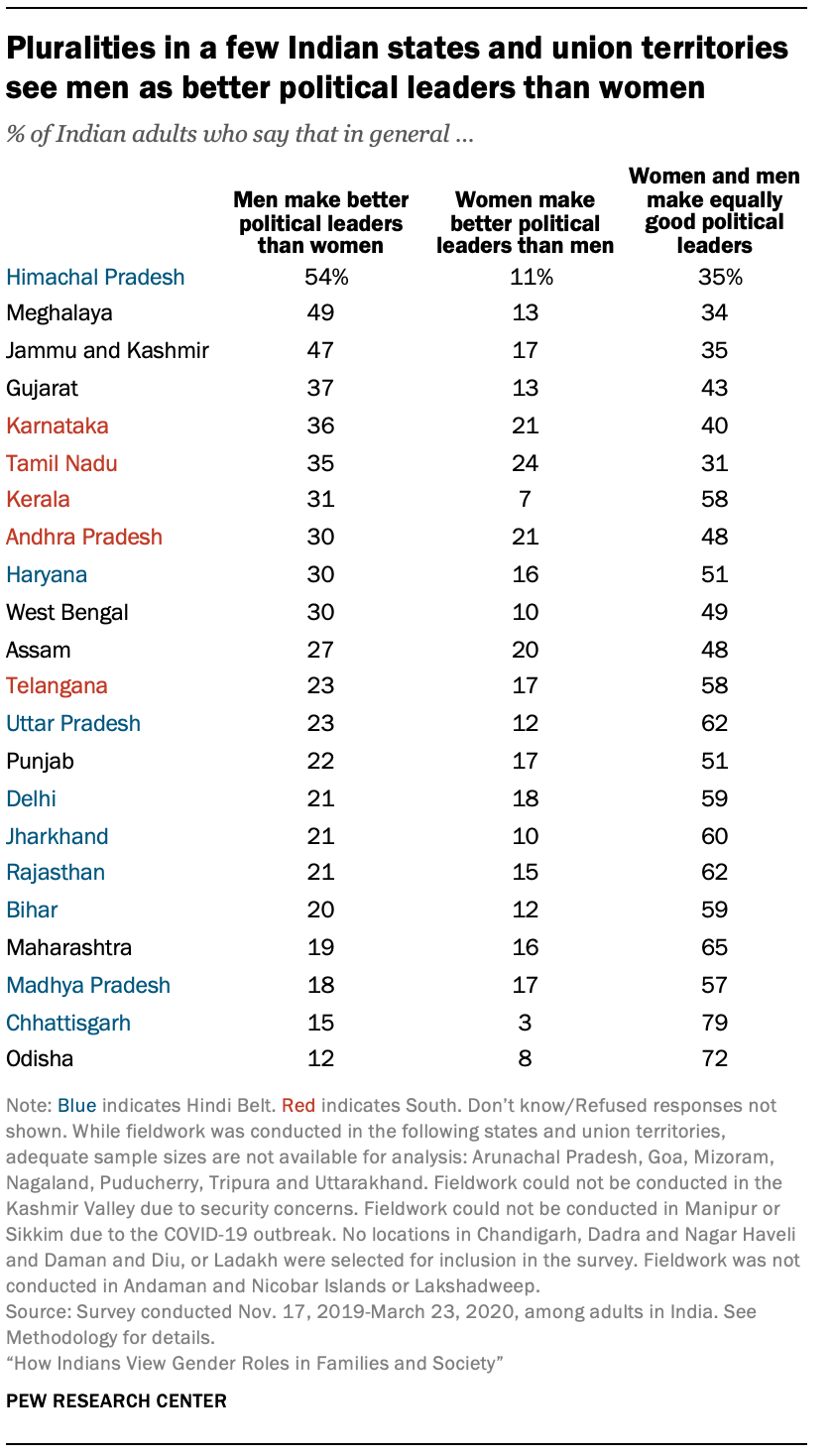

On the whole, however, Indians seem to share an egalitarian vision of women’s place in society. Eight-in-ten people surveyed – including 81% of Hindus and 76% of Muslims – say it is very important for women to have the same rights as men. Indians also broadly accept women as political leaders, with a majority saying that women and men make equally good political leaders (55%) or that women generally make better leaders than men do (14%).

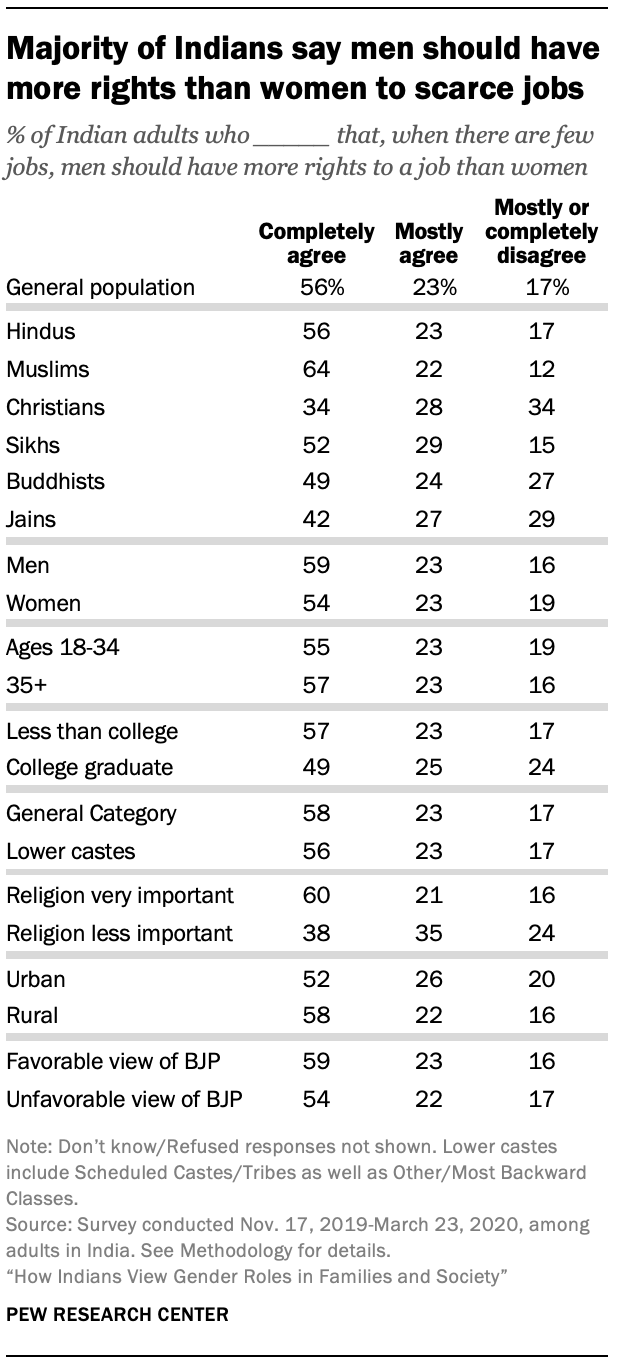

Yet these views exist alongside a preference for traditional economic roles. Indians generally agree that when there are few jobs available, men should have more rights to a job than women (80%), including 56% who completely agree with this statement. Majorities of both men and women share this view, though men are somewhat more inclined to take this position.

Most Indian women do not perceive widespread discrimination against women in India

Roughly a quarter of Indians (23%) say there is “a lot of discrimination” against women in India today. (Respondents were given two options; they could either say there is a lot of discrimination against women, or there is not a lot of discrimination.) Christians are the religious community most likely to perceive widespread discrimination against women in India (30%).

Indian women are only slightly more likely than Indian men to say there is a lot of discrimination against women in the country (24% vs. 22%, respectively). In general, views on gender discrimination do not differ much – if at all – between respondents of different ages or education levels.

While most Indians do not perceive a lot of gender discrimination in their country, Indians are modestly more likely to say there is a lot of discrimination against women than to say the same about discrimination against religious groups or lower castes .

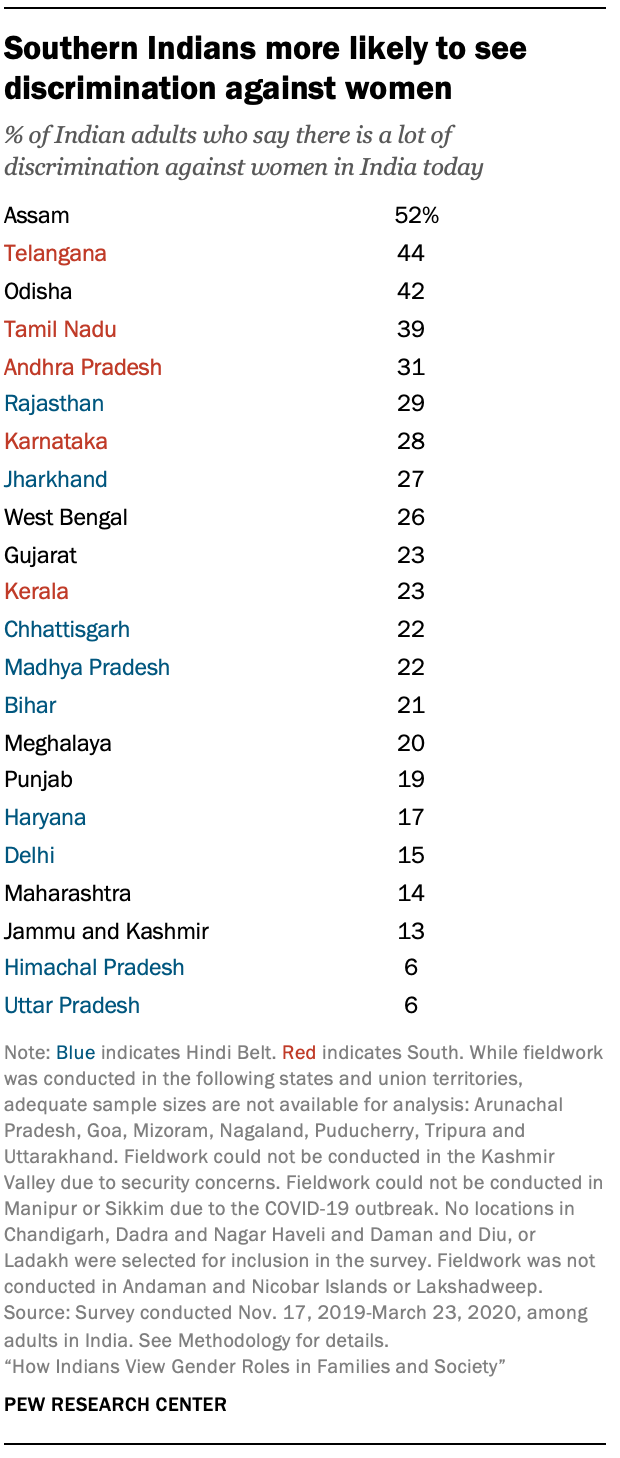

Indians in different regions have very different perceptions of how much discrimination women face. In general, respondents in the South are more likely than those in the Hindi Belt to feel there is a lot of discrimination against women in India today. For example, in the Southern states of Telangana and Tamil Nadu, more than a third of adults say there is a lot of discrimination against women (44% and 39%, respectively). By contrast, in the Hindi Belt states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, only 6% of respondents say this is the case. As Pew Research Center previously has reported, South Indians also are more likely than Indians in the Hindi Belt to perceive a lot of discrimination against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The Northeastern state of Assam stands out, with 52% of respondents reporting widespread gender discrimination. This mirrors the broader pattern of respondents in the Northeast being among the most likely to say there is a lot of discrimination in India against people from various religious groups and from lower castes . But in general, the majority of Indians in most states and union territories say there is not a lot of discrimination against women.

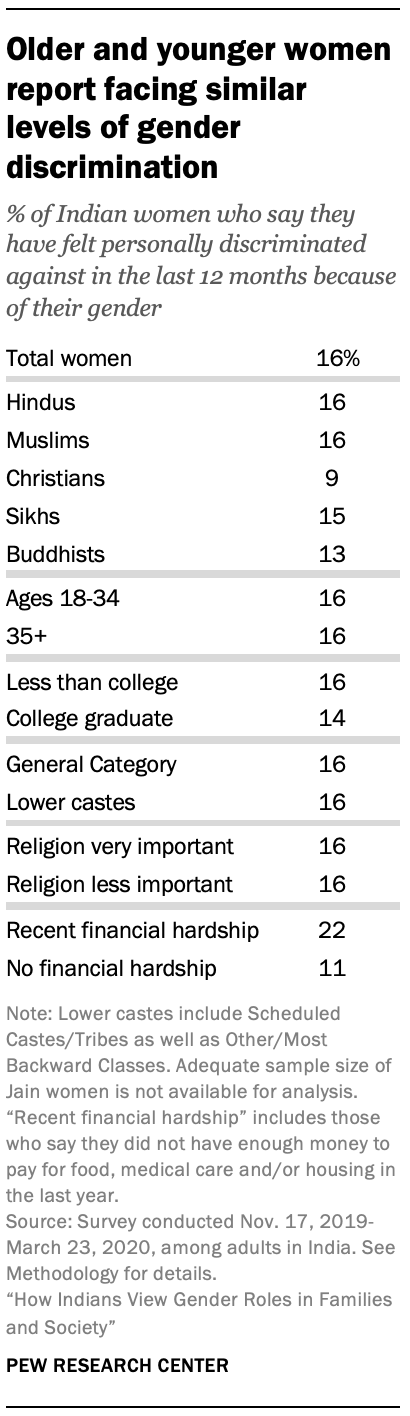

Most Indian women say they have not recently experienced gender discrimination

Fewer than one-in-five Indian women (16%) said they had personally felt discriminated against in the 12 months before the 2019-2020 survey because of their gender. And women were only slightly more likely than men to say they had experienced gender discrimination in the past year (16% vs. 14%, respectively).

Christians – despite being the most likely religious group to say there is a lot of discrimination against women in India – had the lowest rate of women personally reporting discrimination because of their gender (9%).

Across India, women in different age groups and with different levels of education reported experiences with gender discrimination at roughly similar rates. However, women who had faced recent financial difficulties (those who said they had not been able to afford food, housing or medical care for themselves or their families in the last year) were twice as likely as those who had not recently faced such financial difficulties to report that they personally had experienced gender discrimination in the past year (22% vs. 11%).

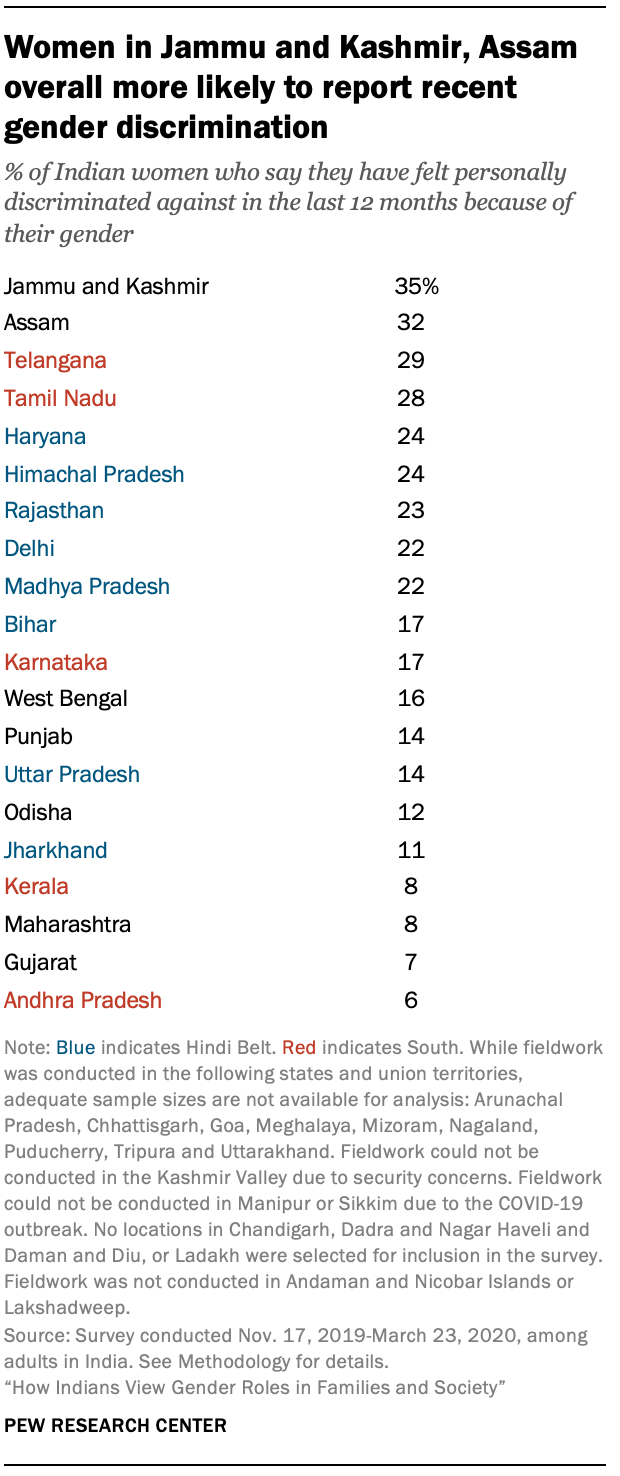

Survey respondents’ personal experiences with gender discrimination also varied across the country. On the upper bound, women in Jammu and Kashmir and in Assam reported the highest levels of personal gender discrimination in the past year (35% and 32%, respectively), while women from Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh were among the least likely to say they personally had faced discrimination because of their gender (7% and 6%, respectively).

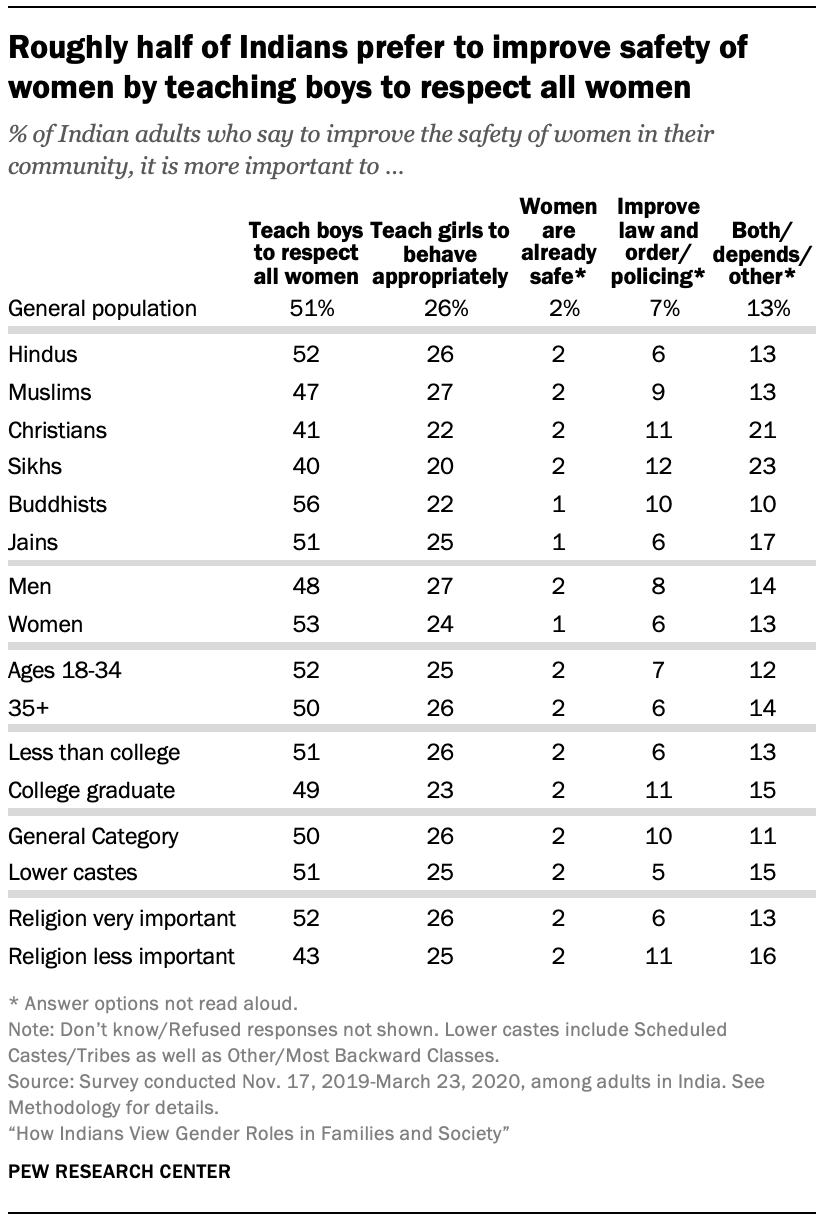

Indians favor teaching boys respect as a way to improve women’s safety

Amidst India’s ongoing problem with violence against women , the survey asked respondents whether, to improve the safety of women in their community, it is more important to teach boys to respect all women or to teach girls to behave appropriately.

About half of Indians (51%) say it is more important to teach boys to respect all women, while roughly a quarter (26%) say it is more important to teach girls to behave appropriately. Others offer a variety of additional responses, such as that teaching both things is important or that it depends on the situation (13%); that improving law and order or policing is the most important way to protect women’s safety (7%); or that women are already safe (2%). A very small share (2%) did not offer a response to the question.

Women are somewhat more likely than men to say that teaching boys to respect all women is the most important way to improve women’s safety (53% vs. 48%).

Within all of India’s major religious communities, the most common response is “to teach boys to respect all women.” However, while Christians and Sikhs are somewhat less likely than other groups to say this, they are more likely than people in other religious groups to say that both kinds of teaching are important or that the right approach depends on the situation.

While opinion does not vary substantially among Indians of different ages or educational backgrounds, a sizeable gap does emerge around religious commitment. Indians who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than others to say that teaching boys to respect all women is crucial to improving the safety of women (52% vs. 43%).

Opinions on the best way to improve women’s safety vary considerably across India. For instance, 63% of Rajasthan residents say it is more important to teach boys to respect all women, compared with 40% of people in West Bengal.

In the South, people in neighboring states have differing views. Only about a third of Tamil Nadu residents would prioritize teaching boys to respect all women (34%), compared with over half of Andhra Pradesh locals (56%).

Most Indians say it is very important that women have same rights as men

Most Indian adults (80%) say that, in general, it is very important for women to have the same rights as men, with solid majorities of all major religious groups sharing this view. Buddhists are especially likely to say gender equality is very important (91%), while Muslims and Christians are somewhat less likely than members of India’s other major religious communities to express this sentiment (76% and 70%, respectively).

Nationally, women, younger Indians (ages 18 to 34), and college graduates are slightly more likely than others to say it is very important for women to have the same rights as men.

Overall, Indians with high levels of religious commitment – i.e., those who say religion is very important in their lives – are more likely than other Indians to believe that gender equality is very important (83% vs. 65%). And those with a favorable view of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are modestly more likely than others to endorse equal rights for women (83% vs. 76%).

Broadly, Indians in the South are somewhat less likely than those elsewhere to say it is very important for women to have the same rights as men. For example, while 80% of Indian adults overall think gender equality is very important, smaller shares in Kerala (72%), Telangana (71%) and Andhra Pradesh (66%) take this position. Still, large majorities across Indian states and union territories share this sentiment.

Most Indians believe women to be equally good political leaders as men

India has a long history of women holding political power, from the 1966 election of Indira Gandhi, one of the world’s first woman prime ministers , to other well-known figures, such as Jayalalitha , Mamata Banerjee and Sushma Swaraj .

The survey results reflect this comfort with women in politics. Overall, a small majority of respondents express the opinion that, in general, women and men make equally good political leaders (55%). Some Indians (14%) even say women tend to make better political leaders than men. Only a quarter of Indians say that men generally make better political leaders than women.

Modest differences by gender exist. Men are more likely than women to believe men are superior politicians (29% vs. 21%, respectively), while women are slightly more likely to favor the abilities of women leaders (16% vs. 13%).

Younger Indian adults (ages 18 to 34) and college graduates are somewhat more likely than their elders and those with less formal education to say women and men make equally good political leaders.

Views on gender and political leadership differ substantially across Indian states. In a handful of states, about a third or more of the population says that men generally make better political leaders than women, including a slim majority in Himachal Pradesh (54%).

By contrast, only about one-in-eight adults in the East Indian state of Odisha (12%) say men make better political leaders. In Odisha and several other states, solid majorities say women and men make equally good political leaders.

In a few states – including the three Southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu – roughly one-in-five or more people surveyed say women generally make better political leaders than men.

Most men and women think men should be given hiring preference when there are few jobs

While a majority of Indians express openness to women political leaders and endorse equal rights for women, the vast majority of the population (80%) agrees with the idea that “when there are few jobs, men should have more rights to a job than women,” including 56% who completely agree with that statement. Most Indian women as well as men express total agreement with this statement, though men are somewhat more likely to do so (59% of men vs. 54% of women).

Although the survey was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic , this question may have become even more relevant because women in India have disproportionately suffered from long-term job losses amidst the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Opinion varies by religious group. Nearly two-thirds of Muslims (64%) completely agree that men should get preference for jobs over women, compared with roughly a third of Christians (34%) who take the same view.

Highly religious Indians are especially likely to fully agree that limited jobs should go to men: Six-in-ten Indians who consider religion very important in their lives say this, compared with about four-in-ten Indians for whom religion is less important (38%).

College graduates are somewhat less inclined than others to completely agree that men should have more rights to a job when employment opportunities are scarce (49% vs. 57%).

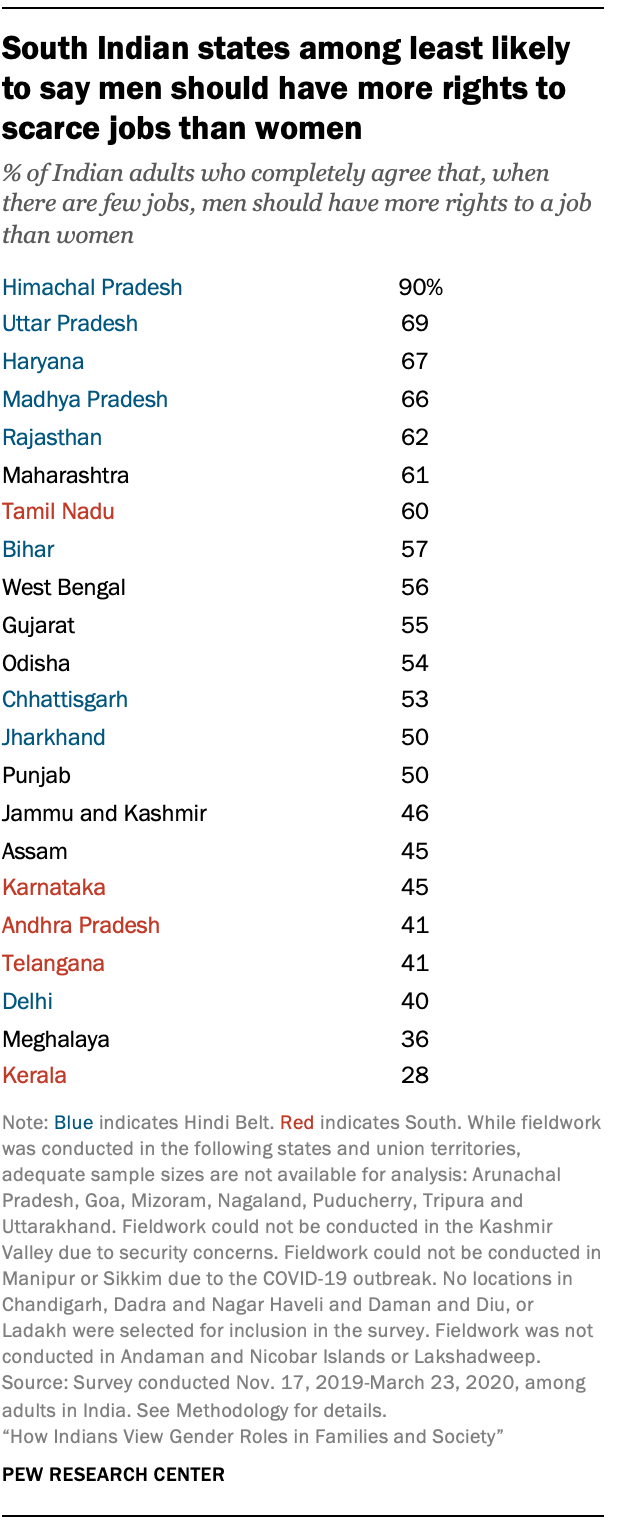

People in some Southern states are among the least likely to completely agree that men should have more rights to limited jobs than women. Fewer than half of respondents in Karnataka (45%), Andhra Pradesh (41%), Telangana (41%) and Kerala (28%) hold this view.

At the same time, a majority of residents in the Southern state of Tamil Nadu (60%) fully agree that when there are few jobs, men should be given preference in hiring. This view also is prevalent in most Hindi Belt states, such as Uttar Pradesh (69%), Haryana (67%) and Madhya Pradesh (66%). And in Himachal Pradesh, nine-in-ten respondents express total agreement with this notion.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Christianity

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Gender & Religion

- Household Structure & Family Roles

- Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

- Religion & Social Values

How people in South and Southeast Asia view religious diversity and pluralism

Religion among asian americans, in their own words: cultural connections to religion among asian americans, in singapore, religious diversity and tolerance go hand in hand, 6 facts about buddhism in china, most popular, report materials.

- Questionnaire

- Tamil Summary of Findings

- Marathi Summary of Findings

- Hindi Summary of Findings

- Bengali Summary of Findings

- Questionnaire: Show Cards

- India Survey Dataset

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Colour me right: It’s time to end colourism in India

Indian society still believes skin colour determines a person’s worth.

My name means “wish”, but over the years I have been called many other names that mean “black”.

This is because I’m a dark-skinned woman from India .

Keep reading

Tunis police raid sees refugees abandoned near the border with algeria, biden labels japan and india ‘xenophobic’ along with china and russia, after deadly attack, russia’s central asian workers report rising racism, ‘feel less and less like playing’: vinicius jr in tears over racist abuse.

My father is dark-skinned, while my mother has fair skin. I took after my father. My skin tone is neither “wheatish” nor “dusky”, as some beauty companies prefer to label darker complexions – it is simply dark brown.

From a very young age, I felt I did not fit in. I was made to believe I was not good enough because of the colour of my skin. People constantly compared my complexion to others. It was impossible to escape their comments and judgements.

Even members of my own family made jokes about the way I look. A popular one was that “the electricity went out in the hospital when my mother was about to deliver me, and that’s how I got my dark colour”.

At school, one of my teachers once asked me, with a smirk, “Are you from Africa?”.

As I grew older, I was pressured to change the way I look, to become lighter-skinned. Desperate measures were taken. From homemade – turmeric, curd, gram – to store-bought, many cosmetic products were applied on my skin to make me fairer.

As soon as I entered my late teens, there were talks within the family about finding me a suitable groom. Once, an elderly relative approached my parents with a proposal from a young man.

My father declined and I heard the relative tell him: “How can you decline? What does your daughter possess that makes you think she could get a better proposal? Have you not seen her? She is dark! “

I never responded to people’s cruel comments or jokes. I never shared my insecurities or feelings of resentment with anyone. I just became numb and shut down. Soon I was not comfortable being in photographs or attending social functions. I wanted to be invisible.

Over the years, I buried the pain deep inside of me. So deep that when I look back today, I find it difficult to recall most of these episodes.

Instead of dealing with my feelings, I chose to live my harsh reality in silence.

My reality was simple: In India, I as a person had less value because of the colour of my skin.

A deep-rooted obsession

India’s obsession with fair skin is well known and deep-rooted. Colour prejudice is widespread and practised openly across the country.

Indian society believes skin colour determines a person’s worth. In our culture, all virtues are associated with “fair” while anything dark has negative connotations. TV programmes, movies, billboards, advertisements, they all reinforce the idea that “fair is beautiful”.

The Advertising Standards Council of India attempted to address skin-based discrimination in 2014 by banning ads that depict people with darker skin as inferior.

This was a step in the right direction, but it failed to change much.

Four years later, India’s media and advertisement industries are still promoting the idea that women with dark complexions should aspire to be fairer.

And most dark-skinned women are still desperately trying to look fair. Some use makeup that is meant for lighter skinned women, choosing to look “whitewashed” rather than embracing their natural skin tone. Others use bleaching products.

I know people who are at least a good 10 shades lighter than me who feel their skin colour is not good enough.

In India, everyone wants to be fairer.

I want change for my daughter

Today, I am a mother blessed with a son and a daughter. My husband and my son are lighter skinned, while my daughter has a darker complexion, like mine.

When she was born, we vowed to never let her feel less valuable because of the colour of her skin. From a very early age, we told her that she is beautiful, that her skin colour is beautiful, and tried to teach her a person’s worth is not determined by the way he or she looks.

However, when she was just three years old, a boy at her preschool wanted to play with her and she was reluctant. When we asked her why, to our astonishment, she said: “because he is brown”.

We were shocked, not understanding what caused her to think like that. We tried to explain to her that she is also brown.

After that incident, it became apparent to us that we cannot protect her from the outside world forever. As soon as she steps outside our house, she is exposed to a culture that values brown-skinned people less.

For example, when her school put on a performance, fair skinned kids were placed at the front regardless of their heights, and darker skinned children were all made to stand at the back, including my daughter. It broke my heart.

After watching that event, I realised that, until society’s perceptions change, my daughter will continue to think her worth is determined by the colour of her skin, just as I did when I was younger. So I decided to do something to facilitate change.

#ColourMeRight