- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

The four-day school week: Research shows benefits and consequences

To save money and help recruit teachers, many U.S. schools are taking Mondays or Fridays off. We look at research on how the four-day school week affects student test scores, attendance and behavior.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource September 6, 2023

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/education/four-day-school-week-research/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

We updated this piece on the four-day school week, originally published in June 2018, to include new figures, research and other information on Sept. 6, 2023.

Just over 2,100 schools in 26 states have switched to a four-day school week, often in hopes of recruiting teachers, saving money and boosting student attendance, according to the most recent estimate from the Four-Day School Week policy research team at Oregon State University.

Small, rural schools facing teacher shortages have led the trend, choosing to take Mondays or Fridays off and giving teachers and students a three-day weekend every week. To make up for the lost day of instruction, school officials tack time onto the remaining four days.

In places where schools have made the change, school district leaders have marveled at the resulting spikes in applications from teachers and other job seekers.

“The number of teacher applications that we’ve received have gone up more than 4-fold,” Dale Herl , superintendent of the Independence, Missouri school district, told CBS News last month .

Independence, which serves about 14,000 students outside Kansas City, introduced the new schedule when classes there resumed last month. In all, 30% of Missouri school districts now have a four-day school week, The Kansas City Star reported recently .

Schools nationwide faced teacher shortages long before the COVID-19 pandemic. But vacancies grew as the virus, which has killed 1.1 million Americans to date , spread.

In the spring before the pandemic, a total of 662 public school districts used the schedule – up more than 600% since 1999, Paul Thompson and Emily Morton , leading researchers in this field, write in a 2021 essay for the Brookings Institution. That number climbed to 876 during the 2022-23 academic year, Thompson and Morton told The Journalist’s Resource in email messages.

Brent Maddin , executive director of the Next Education Workforce project at Arizona State University, told The New York Times the pandemic has made many teachers feel more undervalued.

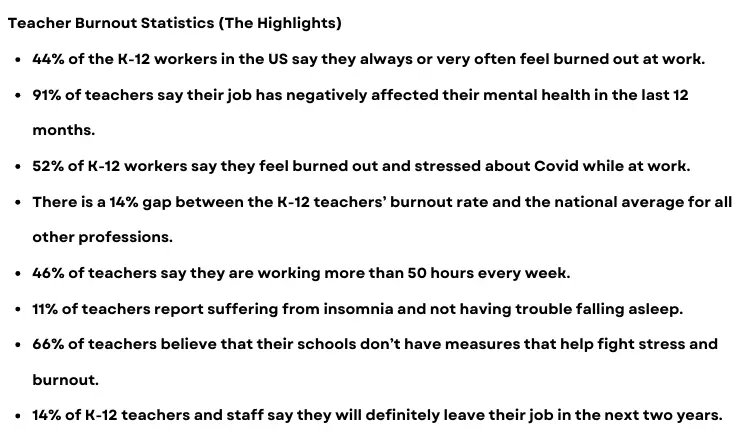

“If we’re serious about recruiting people into the profession, and retaining people in the profession, in addition to things like compensation we need to be focused on the working conditions,” he told the Times.

Scholars are still trying to understand the impact of cutting the school week by one day. Most studies focus on a single state or group of states, so their findings cannot be generalized to all schools on a four-day schedule. The research to date indicates:

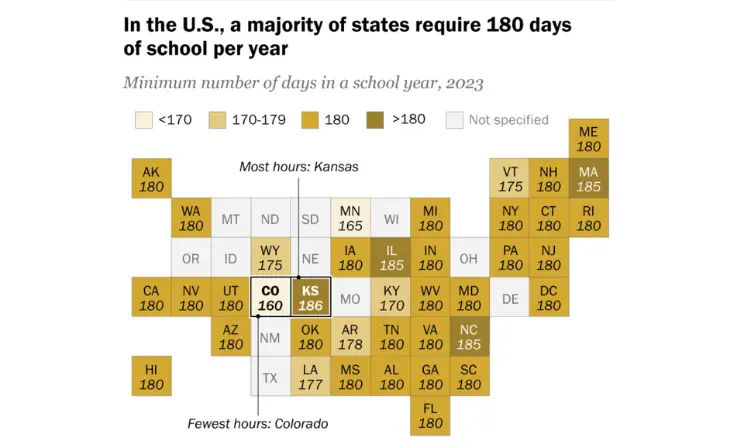

- The amount of time students spend in class varies from state to state.

- Some schools offer less instructional time during a four-day school week than they did during a five-day week.

- There’s limited cost savings, considering employee salaries and benefits make up the bulk of school expenses. In a 2021 analysis , Thompson estimates schools save 1% to 2% by shortening the school week by a day.

- The impact of the condensed schedule differs depending on a range of factors, including the number of hours schools operate and how they structure their daily schedules. Recent research generally finds small drops in student achievement.

- Staff morale improved under a four-day school week.

- High school bullying and fighting declined.

“For journalists looking for a definitive answer to [the question] ‘Are four-day school weeks a good or bad thing?’, I would caution that it is still too early to tell,” Thompson, an associate professor of economics who is part of Oregon State’s Four-Day School Week policy research team, wrote to The Journalist’s Resource.

Both he and Morton urged journalists to explain that the amount of time schools dedicate to student learning makes a big difference.

“I think too often the importance of instructional time for the impacts of the policy is missed,” Morton, a researcher at the American Institutes of Research, wrote to JR. “It’s pretty critical to the story that districts with longer days (who are possibly delivering equal or more instructional time to their students than they were on a five-day week) are not seeing the same negative impacts that districts with shorter days are seeing.”

Keep reading to learn more about the research. We’ll update this collection periodically.

——————–

Impacts of the Four-Day School Week on Early Elementary Achievement Paul N. Thompson; et al. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 2nd Quarter 2023.

Summary: This study is the first to examine the four-day school week’s impact on elementary schools’ youngest students. Researchers looked at how children in Oregon who went to school four days a week in kindergarten later performed in math and English Language Arts when they reached the third grade. What they found: Overall, there were “minimal and non-significant differences” in the test scores of third-graders who attended kindergarten on a four-day schedule between 2014 and 2016 and third-graders who went to kindergarten on a five-day schedule during the same period.

When the researchers studied individual groups of students, though, they noticed small differences. For example, when they looked only at children who had scored highest on their pre-kindergarten assessments of letter sounds, letter names and early math skills, they learned that kids who went to kindergarten four days a week scored a little lower on third-grade tests than those who had gone to kindergarten five days a week.

The researchers write that they find no statistically significant evidence of detrimental four-day school week achievement impacts, and even some positive impacts” for minority students, lower-income students, special education students, students enrolled in English as a Second Language programs and students who scored in the lower half on pre-kindergarten assessments.

There are multiple reasons why lower-achieving students might be less affected by school schedules than high achievers, the researchers point out. For example, higher-achieving students “may miss out on specialized instruction — such as gifted and enrichment activities — that they would have had time to receive under a five-day school schedule,” they write.

Effects of 4-Day School Weeks on Older Adolescents: Examining Impacts of the Schedule on Academic Achievement, Attendance, and Behavior in High School Emily Morton. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, June 2022.

Summary: Oklahoma high schools saw less fighting and bullying among students after switching from a five-day-a-week schedule to a four-day schedule, this study finds. Fighting declined by 0.79 incidents per 100 students and bullying dropped by 0.65 incidents per 100 students.

The other types of student discipline problems examined, including weapons possession, vandalism and truancy, did not change, according to the analysis, based on a variety of student and school data collected through 2019 from the Oklahoma State Department of Education and National Center for Education Statistics.

“Results indicate that 4-day school weeks decrease per-pupil bullying incidents by approximately 39% and per-pupil fighting incidents by approximately 31%,” writes the author, Emily Morton , a research scientist at NWEA, a nonprofit research organization formerly known as the Northwest Evaluation Association.

Morton did not investigate what caused the reduction in bullying and fighting. She did find that moving to a four-day schedule had “no detectable effect” on high school attendance or student scores on the ACT college-entrance exam.

Only a Matter of Time? The Role of Time in School on Four-Day School Week Achievement Impacts Paul N. Thompson and Jason Ward. Economics of Education Review, February 2022.

Summary: Student test scores in math and language arts dipped at some schools that adopted a four-day schedule but did not change at others, according to this analysis of school schedule switches in 12 states.

Researchers discovered “small reductions” in test scores for students in grades 3 through 8 at schools offering what the researchers call “low time in school.” These schools operate an average of 29.95 hours during the four-day week. The decline in test scores is described in terms of standard deviation , not units of measurement such as points or percentages.

At schools offering “middle time in school” — an average of 31.03 hours over four days — test scores among kids in grades 3 through 8 did not change, write the researchers, Paul N. Thompson , an associate professor of economics at Oregon State University, and Jason Ward , an associate economist at the RAND Corp., a nonprofit research organization.

Scores also did not change at schools providing “high time in school,” or 32.14 hours over a four-day school week, on average.

When describing this paper’s findings, it’s inaccurate to say researchers found that test scores dropped as a result of schools adopting a four-day schedule. It is correct to say test scores dropped, on average, across the schools the researchers studied. But it’s worth noting the relationship between test scores and the four-day school week differs according to the average number of hours those schools operate each week.

For this analysis, researchers examined school districts in states that allowed four-day school weeks during the 2008-2009 academic year through the 2017-2018 academic years. They chose to focus on the 12 states where four-day school weeks were most common. The data they used came from the Stanford Educational Data Archive and “a proprietary, longitudinal, national database” that tracked the use of four-day school weeks from 2009 to 2018.

The researchers write that their findings “suggest that four-day school weeks that operate with adequate levels of time in school have no clear negative effect on achievement and, instead, that it is operating four-day school weeks in a low-time-in-school environment that should be cautioned against.”

Three Midwest Rural School Districts’ First Year Transition to the Four Day School Week Jon Turner, Kim Finch and Ximena Uribe-Zarain. The Rural Educator, 2019.

Abstract: “The four-day school week is a concept that has been utilized in rural schools for decades to respond to budgetary shortfalls. There has been little peer-reviewed research on the four-day school week that has focused on the perception of parents who live in school districts that have recently switched to the four-day model. This study collects data from 584 parents in three rural Missouri school districts that have transitioned to the four-day school week within the last year. Quantitative statistical analysis identifies significant differences in the perceptions of parents classified by the age of children, special education identification, and free and reduced lunch status. Strong parental support for the four-day school week was identified in all demographic areas investigated; however, families with only elementary aged children and families with students receiving special education services were less supportive than other groups.”

Juvenile Crime and the Four-Day School Week Stefanie Fischer and Daniel Argyle. Economics of Education Review, 2018.

Abstract: “We leverage the adoption of a four-day school week across schools within the jurisdiction of rural law enforcement agencies in Colorado to examine the causal link between school attendance and youth crime. Those affected by the policy attend school for the same number of hours each week as students on a typical five-day week; however, treated students do not attend school on Friday. This policy allows us to learn about two aspects of the school-crime relationship that have previously been unstudied: one, the effects of a frequent and permanent schedule change on short-term crime, and two, the impact that school attendance has on youth crime in rural areas. Our difference-in-difference estimates show that following policy adoption, agencies containing students on a four-day week experience about a 20 percent increase in juvenile criminal offenses, where the strongest effect is observed for property crime.”

Staff Perspectives of the Four-Day School Week: A New Analysis of Compressed School Schedules Jon Turner , Kim Finch and Ximena Uribe – Zarian . Journal of Education and Training Studies, 2018.

Abstract: “The four-day school week is a concept that has been utilized in rural schools for decades to respond to budgetary shortfalls. There has been little peer-reviewed research on the four-day school week that has focused on the perception of staff that work in school districts that have recently switched to the four-day model. This study collects data from 136 faculty and staff members in three rural Missouri school districts that have transitioned to the four-day school week within the last year. Quantitative statistical analysis identifies strong support of the four-day school week model from both certified educational staff and classified support staff perspectives. All staff responded that the calendar change had improved staff morale, and certified staff responded that the four-day week had a positive impact on what is taught in classrooms and had increased academic quality. Qualitative analysis identifies staff suggestions for schools implementing the four-day school week including the importance of community outreach prior to implementation. No significant differences were identified between certified and classified staff perspectives. Strong staff support for the four-day school week was identified in all demographic areas investigated. Findings support conclusions made in research in business and government sectors that identify strong employee support of a compressed workweek across all work categories.”

The Economics of a Four-Day School Week: Community and Business Leaders’ Perspectives Jon Turner , Kim Finch and Ximena Uribe – Zarian . Journal of Education and Training Studies, 2018.

Abstract: “The four-day school week is a concept that has been utilized in rural schools in the United States for decades and the number of schools moving to the four-day school week is growing. In many rural communities, the school district is the largest regional employer which provides a region with permanent, high paying jobs that support the local economy. This study collects data from 71 community and business leaders in three rural school districts that have transitioned to the four-day school week within the last year. Quantitative statistical analysis is used to investigate the perceptions of community and business leaders related to the economic impact upon their businesses and the community and the impact the four-day school week has had upon perception of quality of the school district. Significant differences were identified between community/business leaders that currently have no children in school as compared to community/business leaders with children currently enrolled in four-day school week schools. Overall, community/business leaders were evenly divided concerning the economic impact on their businesses and the community. Community/business leaders’ perceptions of the impact the four-day school week was also evenly divided concerning the impact on the quality of the school district. Slightly more negative opinions were identified related to the economic impact on the profitability of their personal businesses which may impact considerations by school leaders. Overall, community/business leaders were evenly divided when asked if they would prefer their school district return to the traditional five-day week school calendar.”

Impact of a 4-Day School Week on Student Academic Performance, Food Insecurity, and Youth Crime Report from the Oklahoma State Department of Health’s Office of Partner Engagement, 2017.

Summary: “A Health Impact Assessment (HIA) utilizes a variety of data sources and analytic methods to evaluate the consequences of proposed or implemented policy on health. A rapid (HIA) was chosen to research the impact of the four-day school week on youth. The shift to a four-day school week was a strategy employed by many school districts in Oklahoma to address an $878 million budget shortfall, subsequent budget cuts, and teacher shortages. The HIA aimed to assess the impact of the four-day school week on student academic performance, food insecurity, and juvenile crime … An extensive review of literature and stakeholder engagement on these topic areas was mostly inconclusive or did not reveal any clear-cut evidence to identify effects of the four-day school week on student outcomes — academic performance, food insecurity or juvenile crime. Moreover, there are many published articles about the pros and cons of the four-day school week, but a lack of comprehensive research is available on the practice.”

Does Shortening the School Week Impact Student Performance? Evidence from the Four-Day School Week D. Mark Anderson and Mary Beth Walker. Education Finance and Policy, 2015.

Abstract: “School districts use a variety of policies to close budget gaps and stave off teacher layoffs and furloughs. More schools are implementing four-day school weeks to reduce overhead and transportation costs. The four-day week requires substantial schedule changes as schools must increase the length of their school day to meet minimum instructional hour requirements. Although some schools have indicated this policy eases financial pressures, it is unknown whether there is an impact on student outcomes. We use school-level data from Colorado to investigate the relationship between the four-day week and academic performance among elementary school students. Our results generally indicate a positive relationship between the four-day week and performance in reading and mathematics. These findings suggest there is little evidence that moving to a four-day week compromises student academic achievement. This research has policy relevance to the current U.S. education system, where many school districts must cut costs.”

Other resources

- The Education Commission of the States offers a 50-state comparison of public school students’ instructional time requirements. For example, students in Colorado are required to be in school for a minimum of 160 days each academic year while in Vermont, the minimum is 175 days and in North Carolina, it’s 185.

- The State of the American Teacher project offers insights into how teachers feel about their jobs and the education field as a whole. In early 2022, RAND Corp. surveyed a nationally representative sample of teachers, asking questions on topics such as job-related stress, school safety, COVID-19 mitigation policies and career plans. Survey results show that 56% of teachers who answered a question about their attitude toward their job “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed with the statement, “The stress and disappointments involved in teaching aren’t really worth it.” Meanwhile, 78% “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed with the statement, “I don’t seem to have as much enthusiasm now as I did when I began teaching.”

- Opinions about the four-day school week vary among school board members, district-level administrators, school principals and teachers. These organizations can provide insights: the Schools Superintendents Association , National School Boards Association , National Association of Elementary School Principals and National Association of Secondary School Principals .

Looking for more research on public schools? Check out our other collections of research on student lunches , school uniforms, teacher salaries and teacher misconduct .

About The Author

Denise-Marie Ordway

A Four-Day School Week?

- Posted June 28, 2018

- By Denise-Marie Ordway

To save money and help with teacher recruitment, numerous school districts in the United States have decided to give students and employees Fridays off. An estimated 560 districts in 25 states have allowed at least some of their schools to adopt a four-day week, with most moving to a Monday-to-Thursday schedule, according to the National Conference of State Legislators . Generally, schools make up for the lost day by adding extra time to the remaining four days.

Four states — Colorado, Montana, Oklahoma and Oregon — are leading the trend, which is especially popular in rural areas. More than 60 school systems in Montana alone were using a compressed schedule in 2016-17, state records show. Meanwhile, four-day scheduling has spread so quickly across New Mexico that lawmakers have placed a moratorium on the practice until state leaders can study its impact on student performance and working-class families.

"If local leaders are lucky, graduates of these schools won’t be any less well educated than their siblings who went to school all week. But, in an environment where young rural adults already suffer from isolation and low economic opportunity, the shorter school week could exacerbate their problems." – Paul T. Hill

Critics point out that the change can be tough on lower-income parents, who may have trouble paying for childcare on the day their kids no longer have class. Also, low-income students rely on public schools for almost half their meals — breakfasts and lunches during the week. Paul T. Hill , a research professor at the University of Washington Bothell who founded the Center on Reinventing Public Education, has argued that while some adults like the new schedule, it could end up hurting rural students.

“The idea has proved contagious because adults like it: Teachers have more free time, and stay-at-home parents like the convenience of taking kids to doctors and doing errands on Friday,” Hill co-wrote in a piece published on the Brown Center Chalkboard blog in 2017. “If local leaders are lucky, graduates of these schools won’t be any less well educated than their siblings who went to school all week. But, in an environment where young rural adults already suffer from isolation and low economic opportunity, the shorter school week could exacerbate their problems.”

It appears that while a truncated schedule does cut costs, the savings is small. A 2011 report from the Education Commission of the States examined six school districts and found that switching to a four-day schedule helped them shave their budgets by 0.4 percent to 2.5 percent. “In the Duval [County, Florida] school district, moving to a four-day week produced only a 0.7 percent savings, yet that resulted in a budget reduction of $7 million. That $7 million could be used to retain up to 70 teaching positions,” the report states.

See below for recent journal articles and government reports, as well as links to other resources, including a 50-state comparison of local laws outlining student instructional time requirements.

Excerpted from an article by Journalist's Resource , a project at the Harvard Kennedy School 's Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy . Read the original piece .

Additional Resources

- Juvenile Crime and the Four-Day School Week

- Staff Perspectives of the Four-Day School Week: A New Analysis of Compressed School Schedules

- The Economics of a Four-Day School Week: Community and Business Leaders’ Perspectives

- Impact of a 4-Day School Week on Student Academic Performance, Food Insecurity, and Youth Crime

- Does Shortening the School Week Impact Student Performance? Evidence from the Four-Day School Week

- A 50-state comparison of students’ instructional time requirement, from the Education Commission of the States

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Fighting for Change: Estefania Rodriguez, L&T'16

Notes from ferguson, part of the conversation: rachel hanebutt, mbe'16.

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

PROOF POINTS: Seven new studies on the impact of a four-day school week

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

- Weekly Update

- Future of Learning

- Higher Education

- Early Childhood

- Proof Points

Is a four-day school week a bad idea?

The answer matters because hundreds of thousands of students at more than 1,600 schools across 24 states were heading to school only four times a week by the spring of 2019, according to one estimate . The number of four-day schools had exploded by more than 600 percent from 20 years earlier in 1999, when only about 250 schools had four-day weeks. That tally could be even larger today because more schools switched to a four-day schedule during the pandemic.

Although the switch was initially seen as a cost-saving measure, educators have quickly learned that longer weekends are immensely popular with families, especially in rural communities where the truncated school week is most common.

“We know that kids love it and so do parents and teachers,” said Emily Morton, a researcher at NWEA, a nonprofit assessment company, who has studied four-day school weeks around the country. “There are crazy high approval ratings for this policy.” Eighty-five percent of parents and, perhaps unsurprisingly, 95 percent of kids said they would choose to stay on a four-day school week, according to a RAND survey published in 2021 .

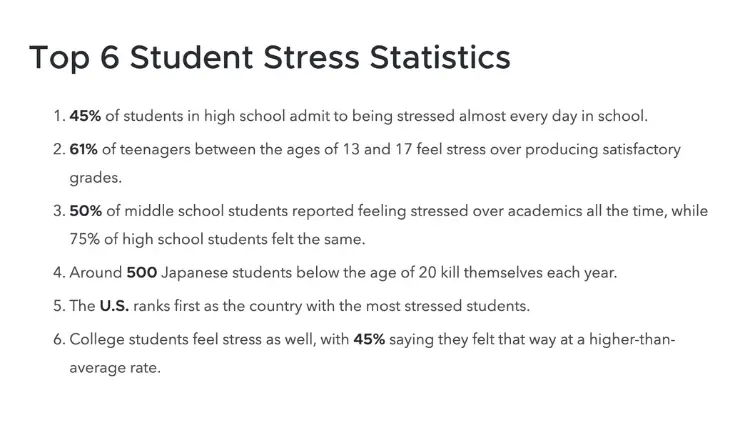

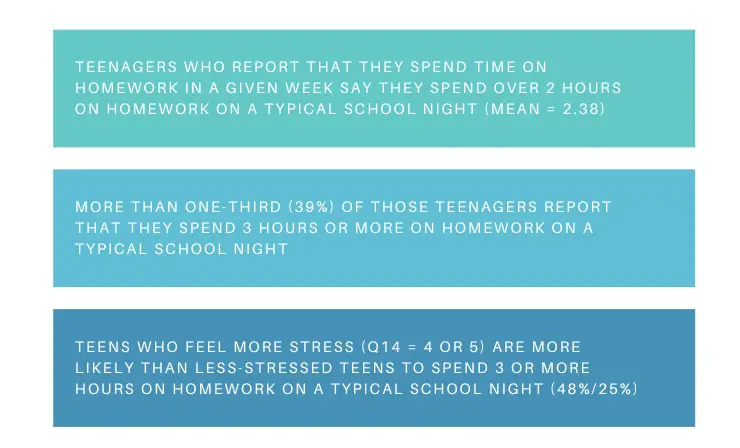

But over the course of a typical 36-week school year, a four-day week means 36 fewer days of school. Many policymakers lament the downsizing of education, worried that students may learn less. Legislators in New Mexico are debating whether to crackdown on the schedule switch. Oklahoma passed a law to restrain the move to four-day weeks but delayed putting it into effect. Today, when many education advocates want to expand learning time to help kids recover academically from the pandemic, the four-day week would seem to be a move in the wrong direction.

The research evidence isn’t clear. The first empirical study, published in 2015, found that Colorado students in four-day schools did a lot better . The number of fifth grade students who were proficient in math rose by more than 7 percentage points. The number of fourth grade students who were proficient in reading rose by nearly 4 percentage points. Those results seemed to defy logic.

But now seven newer studies generally find negative results – some tiny and some more substantial. One 2021 study in Oregon , for example, calculated that the four-day week shaved off one-sixth of the usual gains that a fifth grader makes in math, equal to about five to six weeks of school. Over many years, those losses can add up for students.

The most recent of the seven studies, a preliminary paper posted on the website of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University in August 2022, is a large multi-state analysis and it found four-day weeks harmed some students more than others.

Researchers at NWEA, led by Morton, and at Oregon State University began by analyzing the test scores of 12,000 students at 35 schools that had adopted four-day weeks in six states: Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming. Like the more recent crop of studies, they found that four-day weeks weren’t great for academic achievement on average . The test scores of four-day students in grades three through eight grew slightly less during the school year compared to hundreds of thousands of students in those six states who continued to go to school five days a week. (City students were excluded from the analysis because no city schools had adopted four-day weeks. Only rural, small town and suburban students were included.)

The switch seemed to hurt reading achievement more than math achievement. That was surprising. Reading is easier to do at home while math is a subject that students primarily learn and practice in school. During pandemic school closures and remote learning, for example, math achievement generally suffered more than reading.

The researchers focused on rural students. Rural schools accounted for seven out of 10 schools on the four-day schedule in this study. The types of students in rural communities were also different. They tended to be poorer than in small towns and suburbs and the rural students’ test scores were lower. In the six midwestern and western states in this study, the share of Native American and Hispanic students was higher in rural areas than in small towns and suburbs.

When researchers compared rural students who attended four-day schools with rural students who attended traditional five-day schools, ignoring small town and suburban students altogether, the results suddenly changed. Rural four-day students generally learned as much as rural five-day day students. Statistically, both groups’ test scores rose by about the same amount every year.

By contrast, small town and suburban students who switched to four-day weeks were far worse off than other students in the state. Though it’s less common for small town and suburban schools to switch to four-days – they constitute only 30 percent of the four-day schools – their students really seemed to be harmed. For example, a quarter of the usual achievement gains that fifth graders typically make in a year disappeared.

The distinctions that the U.S. Census Bureau makes between a rural area and a small town are quite technical. I think of a small town as far from a metropolitan area, but with a bit of commerce and more people than a rural area would have.

This quantitative study of test scores does not explain why students at rural schools are faring better with only four days than students in small towns. NWEA’s Morton, the lead author, has long been studying four-day school weeks and conducted an earlier 2022 study in rural Oklahoma , where she found no academic penalty for the shorter week.

One possible explanation, Morton says, is sports. Many rural athletes and young student fans leave school early on Fridays or skip school altogether because of the great distances to travel to away games. In effect, many five-day students are only getting four-days of instruction in rural America.

“One district we talked to, half the kids would be out on Friday for football,” said Morton. “They would not really have math on Friday, because how can you teach with only half the classroom? So it’s affecting everyone.”

Absences for football games, considered to be part of school, are often “excused.” Official records don’t reveal that attendance rates are any better at four-day schools because many of the Friday classes that five-day students skip aren’t documented in the attendance data.

Another possible explanation is teaching. The four-day work week is an attractive work perk in rural America that may lure better teachers.

“It is harder for rural districts to get teachers that are highly qualified or honestly, sometimes to get teachers period, into their buildings and to retain them than it is for town or suburban districts,” said Morton. “All of this is anecdotal, but they’re saying in interviews that teachers are happier. They like spending more time with their own children. It gives them time to do things that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to do.”

By this theory, four-day schools may make it easier to hire better teachers, who could accomplish in four days what a less skilled teacher accomplishes in five days.

Four-day weeks are not necessarily better, but five-day weeks have their own drawbacks in rural America: hidden absences, skipped lessons and lower quality teachers.

So what to make of it all? Morton says there are reasons to think that four-day weeks are working better in rural America than elsewhere, but she wouldn’t wholeheartedly recommend it. Hispanic students, who accounted for one out of every six rural students in this study, suffered much more from four-day weeks than white students did. (Native American students, who made up one of every 10 rural students, did relatively better with the four-day week.)

Morton is also worried that rural students may be ultimately harmed academically from the shorter week. In her calculations, she detected hints that even four-day students in rural schools might be learning slightly less than five-day students, but the difference was not statistically significant. A downside to a four-day education could be detected in a larger study with more students.

“We don’t want to say ‘it doesn’t hurt kids’ when it might actually be hurting kids a little bit,” said Morton. “Another thing that could be happening is it could hurt kids more over time. It could be that we haven’t observed it for long enough.”

For schools that are considering a four-day week, the schedule matters. Some schools have been better at preserving instructional time, reallocating the hours across four longer days, Morton told me. Others have struggled to protect every minute of math and reading instruction. Longer hours can also tax young children’s attention spans. It’s a tradeoff.

Historically, schools have shortened school weeks for cost savings. That’s been especially needed in rural communities, which were not only hit with declining tax revenues after the 2008 recession, but continued to suffer education budget cuts because of depopulation and declining student enrollment.

However, the biggest surprise to me in this review of the research is how tiny the cost savings are: 1 to 2 percent . It does save some money not to run the heat or buses one day a week, but the largest expenses, teacher salaries, stay the same.

The four-day week may ultimately be a popular policy, but not one that’s particularly great for public coffers or learning.

This story about a four-day school week was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter .

Related articles

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Jill Barshay SENIOR REPORTER

(212)... More by Jill Barshay

Letters to the Editor

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.

HI Ms. Barshay, Do you have any information on what a 4-day school week would do for poor and/or homeless students? Or how underperforming school districts can make real impacts to these students’ learning in a 4-day school week as they lose a day of consistent instruction? Whether rural or urban?

Hi! My group is debating whether 4-day or 5-day weeks are better do you know if 5-day is better, or 4-day.

Hi, my group is also debating on this topic. Im in the 10th grade and go to sycamore high school in BlueAsh, Ohio on Cornell road. I wanted to know how does this effect the to not have a day of school but longer days? Would this harm the sleep schedule or Increase their intelligent and chances for higher test scores?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Submit a letter

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Planet Money

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

The rise of the four-day school week

Sarah Gonzalez

Mary Childs

Molly Messick

Sam Yellowhorse Kesler

Right now, a lot of school districts across the country are making a pretty giant change to the way public education usually works. Facing teacher shortages and struggling to fill vacant spots, they are finding a new recruitment tool: the four-day school week.

Those districts are saying to teachers, "You can have three-day weekends all the time, and we won't cut your pay." As of this fall, around 900 school districts – that's about 7% of all districts in the U.S. – now have school weeks that are just four days long.

And this isn't the first time a bunch of schools have scaled back to four days, so there is a lot of data to lean on to figure out how well it works.

In this episode, teachers love the four-day school week, and it turns out even parents love it, too. But is it good for students?

This episode was produced by Sam Yellowhorse Kesler with help from Willa Rubin. It was edited by Molly Messick and engineered by Maggie Luthar. Fact-checking by Sierra Juarez. Alex Goldmark is our executive producer.

Baby's first market failure

Help support Planet Money and get bonus episodes by subscribing to Planet Money+ in Apple Podcasts or at plus.npr.org/planetmoney .

Always free at these links: Apple Podcasts , Spotify , Google Podcasts , NPR One or anywhere you get podcasts.

Find more Planet Money: Facebook / Instagram / TikTok / Our weekly Newsletter .

Music: Universal Production Music - "Wrong Conclusion," "Bossa Nova Dream," and "Please Hold"

4-day school weeks: Educational innovation or detriment?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, evidence suggests instructional time makes the difference, paul thompson and paul thompson associate professor, school of public policy - oregon state university @paul_n_thompson emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea @emily_r_morton.

July 12, 2021

Four-day school week schedules are becoming an increasingly common experience for America’s rural youth. These schedules typically involve increasing the length of the school day four days per week and “dropping” the fifth day. In the spring before the COVID-19 pandemic, 662 districts were using the schedule across 24 states, an increase of over 600% since 1999.

During the pandemic, many additional schools in both rural and non-rural areas adopted alternative school schedules, such as the four-day school week. These schedules generally altered the amounts and proportions of synchronous (in-seat) and asynchronous (at-home) learning students received. School administrators have described the pandemic as a “ catalyst ” for necessary innovations to school schedules and in-seat learning time.

Most of these changes were unprecedented, and their effects on students’ learning and well-being beyond the pandemic remain largely unknown. However, emergent research on the four-day school week may allow us to better assess its effectiveness as a school model in post-pandemic educational policy.

Recent survey findings show that four-day school weeks have been adopted as a way to alleviate budgetary issues, attract teachers, and reduce student absences—issues that the pandemic exacerbated for many districts. Although conditions may be ripe for more schools to turn to such a model in the wake of the pandemic, the research suggests that most of these aims fail to be realized.

Here, we describe the key takeaways from this emerging body of evidence.

Shorter weeks may attract teachers, but don’t expect major cost savings or attendance gains

National and state-specific research finds minimal impacts of the four-day school week on overall cost savings, but it suggests that four-day school weeks may allow school districts greater resource flexibility in the wake of budget shortfalls. The four-day school week may also be used as a form of non-monetary compensation to facilitate instructional cost reductions, as research finds that teachers generally prefer it .

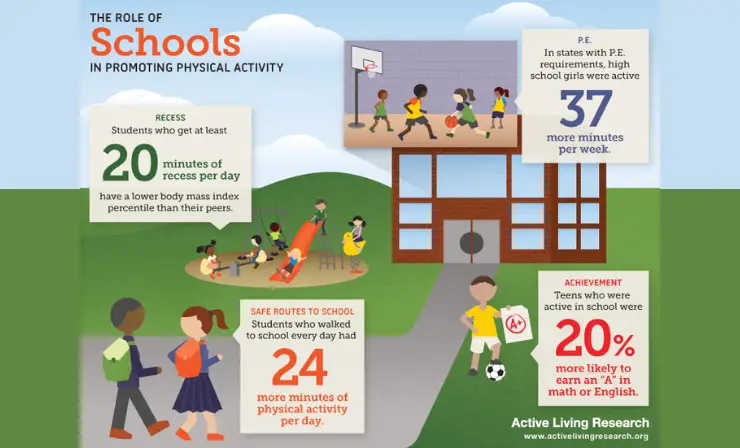

In terms of student attendance, the research to date finds minimal impacts on measures of recorded daily attendance . However, some educators reason that that the four-day week could improve attendance in more nuanced ways undetected by traditional measures of attendance. Most notably, the schedule could decrease the class time that rural students miss for lengthy travel to appointments or extracurricular activities by shifting many of these activities to the off-day.

Maintaining instructional time key for mitigating academic harm

A key concern surrounding the four-day school week is the impact on students’ academic progress. While the evidence regarding overall student achievement impacts is mixed, recent evidence has found primarily negative achievement impacts of four-day school weeks in Oklahoma and Oregon . This has led to a prevailing perception that four-day school weeks are bad for student achievement, a sentiment that was articulated in a recent Education Next piece on the Oregon study . However, the Oregon four-day school week experience is hardly the norm. A more nuanced take of the evidence would suggest that the effects on achievement may depend on whether instructional time stays mostly intact.

In the Oregon study , for example, the stark reductions in math and reading achievement were associated with reductions of three to four hours in weekly time in school. Recent national evidence also suggests that the schools where four-day weeks led to reductions in learning time see the most negative outcomes on student academic progress, with little to no impact on achievement among schools that maintain adequate learning time. Thus, structuring the four-day school week to maintain adequate learning time seems to be the key to avoiding student learning loss and presents a path forward for schools considering this schedule.

Across the country, students on four-day weeks spend about 85 fewer hours per year at school. Some of that time is likely to be lost instructional time, but a portion of it is also non-instructional time, like lunch, recess, and hallway passing time. It’s theoretically possible for a district to maintain its instructional time if it sufficiently extends its school days and reduces the proportion of time spent on non-instructional activities. But in practice, the schedule changes we observe show most schools are reducing instructional time to facilitate the switch.

Few schools with four-day weeks have historically provided any in-school or asynchronous learning opportunities on the off-day. Approximately 50% of schools report being completely closed and only 30% offered any sort of remedial or enrichment activities with any frequency (e.g., regularly or as-needed).

More to worry about than just achievement losses

Lost exposure to the school environment doesn’t only mean missing in-person academic instruction, but also reduced access to school-meal programs, physical activity opportunities, and structured social interactions with peers, teachers, and administrators. A recent study from Colorado finds mixed evidence on health outcomes in schools using a four-day week, but much more research is needed to understand various potential impacts of the schedule on student health.

Worries about child care and unsupervised children on the off-day also abound in discussions of four-day school week implementation. Evidence from Colorado suggests that adolescent students may engage in more criminal activity as a result of the off-day, while a multi-state study found that maternal employment and labor market earnings were reduced as a result of the four-day school week. Despite this evidence, much more research is needed to understand the impact of the four-day school week on family dynamics, relationships, and time use.

The future of four-day school weeks

In the wake of the forced educational innovation during the pandemic, many schools will reconsider their schedules, their policies on in-seat learning time, and synchronous versus asynchronous learning. These decisions could have long-term implications for students’ achievement and well-being.

For districts that have adopted or are interested in adopting four-day weeks, offering asynchronous learning on the off-day could be a creative way for districts to maintain instructional time. Asynchronous learning has been a staple of many pandemic-related educational provision options and, while likely inferior to in-person instruction (as the pandemic learning-loss research suggests), it could be seen as a beneficial supplement to regular in-person school instruction in a post-pandemic educational climate. Incorporating at-home, off-day learning could allow school districts to experience the potential benefits of the four-day school week model while helping to mitigate the achievement losses if in-person time in school is to be reduced.

Increased internet infrastructure, especially in rural and remote areas, has facilitated online synchronous and asynchronous instruction during the pandemic. And while there is worry that some of the new infrastructure investment may be temporary , continued long-term investments in connecting remote communities–as suggested in the recent Biden administration’s “ American Jobs Plan ”–may make at-home learning more feasible in the areas where four-day school weeks have generally been adopted.

If four-day school weeks continue to be implemented nationwide, issues related to shifting the burdens of food provision and child care on the off-day onto families are likely to remain substantial in many areas. However, continuing to expand “grab-and-go meal” programs that have been a staple of school-meal provision during the pandemic could be a promising strategy for providing school meals on the off-day for students on four-day weeks in the future. (The USDA recently extended these programs through the 2022 academic year .) The American Jobs Plan also outlines expansions to child-care infrastructure, potentially paving the way for more off-day child-care options for parents in these four-day school week communities.

For better or for worse, four-day school weeks–once dubbed a “ troubling contagion ”–appear to be a fixture of the post-pandemic educational landscape. The evidence to date suggests that how schools structure the four-day schedule is a key determinant in this model’s impact on learning outcomes. Minimizing the loss of instructional time appears to be the best chance at avoiding negative results, though more research is needed to understand the full scope of impacts on students, families, and communities. It also remains to be seen whether other educational innovations in the wake of the pandemic–including remote learning opportunities, greater access to meal programs, and off-day child care–will further the effectiveness of the four-day school week in a post-pandemic world.

Related Content

Paul T. Hill, Georgia Heyward

March 3, 2017

Alice Opalka, Alexis Gable, Tara Nicola, Jennifer Ash

August 10, 2020

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Douglas N. Harris

June 6, 2024

Carly D. Robinson, Katharine Meyer, Susanna Loeb

June 4, 2024

Monica Bhatt, Jonathan Guryan, Jens Ludwig

June 3, 2024

Home » Tips for Teachers » 6 Reasons Why School Days Should Be Shorter: Unpacking the Benefits and Challenges of Reduced Classroom Hours

6 Reasons Why School Days Should Be Shorter: Unpacking the Benefits and Challenges of Reduced Classroom Hours

The contemporary educational landscape is marked by a critical debate: should school days be shorter? The article “6 Reasons Why School Days Should Be Shorter” ventures into this discussion, dissecting various dimensions of the length of school days and their impact on the educational ecosystem. This exploration is not just limited to the United States; it extends to a global perspective, offering a comparative analysis of school day lengths and their varying implications across different cultures and education systems.

The article methodically unpacks the intricacies of school day regulations within the U.S., illustrating the diversity and complexity of policies that govern educational time. It also delves into the advantages of shorter school days, considering how they could reshape learning experiences, boost academic performance, and enhance student well-being. These potential benefits are juxtaposed with the challenges and concerns that accompany the prospect of reducing school hours.

Shorter school days. Elementary should be 5 hours, 6-7 for middle, 8 for high school, rather than teaching 7 year olds that they’re misbehaving if they get too antsy while sitting in a chair for 8 hours — astarion’s spoon ⏳ (@PurpleInsomnia_) November 17, 2023

From the logistical hurdles for schools and families to the implications for instructional quality, the article comprehensively examines the multifaceted impact of this significant shift in educational practice. By offering a balanced perspective, it aims to contribute thoughtfully to the ongoing dialogue on optimizing school day length for the betterment of students, educators, and the broader educational community.

What you’ll find on this page:

- Understanding the Diversity in School Day Regulations Across the U.S. →

- Comparative Analysis of School Day Lengths: A Global Perspective →

- Key Benefits of Shorter School Days →

- Evaluating the Challenges of Shorter School Days and Addressing Concerns →

- A Look at Successful Shorter School Day Models Around the World →

Understanding the Diversity in School Day Regulations Across the U.S.

The length of the school day in the United States is subject to state regulations, with the average K-12 public school session spanning approximately 180 days annually. This figure emerges from an analysis by the Pew Research Center , which examined data from the Education Commission of the States . However, the uniformity ends there, as the definition of a ‘school day’ and the total educational time varies significantly across different states.

In the United States, the regulation of the school day length is characterized by significant diversity, with states adopting various criteria such as minimum days, hours, or minutes per school year. This variety reflects the unique educational needs and preferences of different regions:

- State Regulations on School Days: 39 states have laws or policies setting minimum school times. Notably, Oklahoma offers flexibility with options like 180 standard school days or 1,080 hours over 165 days.

- Variation by Grade Level: Among these states, 26 have varying annual time minimums based on grade level. For example, South Dakota requires 875 hours for fourth graders and 962.5 hours for eighth graders.

- Average Instructional Hours: There’s a significant range in instructional hours across states. On average, fourth graders receive about 997.8 hours annually, while 11th graders experience a wider range from 720 hours in Arizona to 1,260 hours in Texas, averaging 1,034.8 hours.

- Daily Time Requirements: Additionally, 29 states and the District of Columbia have specific daily hours or minutes requirements, often differing by grade. Pennsylvania’s daily minimum varies from 2.5 hours for kindergarten to 5.5 hours for high school students.

- Extremes in Daily Hours: The school day length for eighth graders can range from as little as 3 hours in Maryland and Missouri to as much as 6.5 hours in Tennessee. New Hampshire and Oregon even have maximum daily limits.

- Texas’s Unique Approach: Texas specifies a total of 75,600 minutes (1,260 hours) per school year, including breaks, allowing districts to decide how to allocate these minutes. Previously, Texas had a 7-hour school day, which equated to a 180-day school year.

This diverse array of regulations across the U.S. showcases the adaptability in meeting educational needs, balancing instructional requirements with practical considerations in various school environments. Each state’s approach is tailored to the specific needs and preferences of its districts, illustrating the varied landscape of educational time management in the country.

Comparative Analysis of School Day Lengths: A Global Perspective

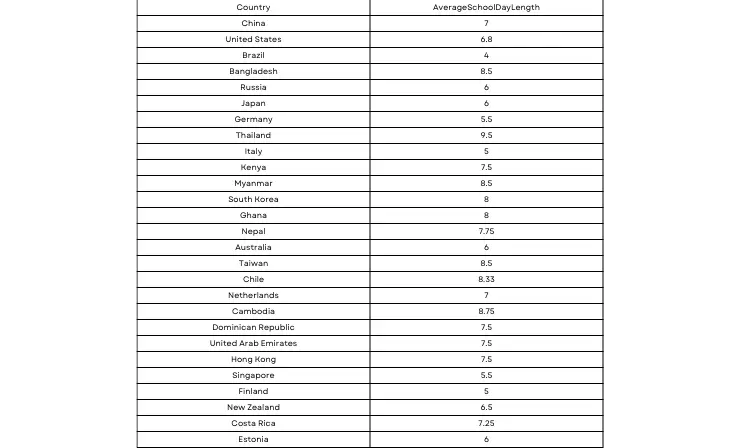

The length of the school day in the United States, averaging around 7 hours and 30 minutes, reveals interesting contrasts when compared to school days in other countries. This comparison highlights the diverse educational practices and philosophies globally.

- In Asia , Taiwan and China exhibit significantly longer school days than the U.S., with Taiwan leading at 10 hours and China close behind at around 9 hours and 30 minutes. These extended hours reflect the intense academic focus prevalent in many Asian educational systems.

- European countries like France and Chile (although not in Europe but demonstrating a similar approach) have school days lasting about 8 hours, which is slightly longer than the U.S. This duration tends to balance academic instruction with other activities.

- The United Kingdom , with a 7-hour school day, is quite comparable to the U.S. However, Commonwealth countries such as Canada and Australia have slightly shorter school days, around 6 hours and 30 minutes and 6 hours and 15 minutes, respectively.

- Further contrast is seen in countries like Russia, Spain, Mexico , and Italy , where the school day spans approximately 6 hours, offering a more balanced approach between academic pursuits and other aspects of student life. Finland and Brazil , known for their progressive educational policies, have even shorter school days, averaging around 5 hours, focusing on efficiency and student well-being.

- Germany represents the shortest average school day at 4 hours and 30 minutes, indicating a different educational philosophy that may emphasize the quality of instruction over the number of hours spent in school.

These comparisons show that the U.S. falls in the middle range of school day lengths. Unlike the longer days seen in Asian countries, which focus heavily on academics, and shorter than those in countries like Germany, which prioritize concentrated and efficient learning, the U.S. school day reflects a balance of instructional time and other educational activities. This diversity in school day lengths across countries underscores varying educational approaches and priorities, shaped by cultural, social, and pedagogical factors unique to each nation.

Key Benefits of Shorter School Days

The concept of shorter school days is increasingly being recognized as beneficial for students, leading to happier, healthier, and more successful outcomes. This approach challenges the traditional belief that longer school hours are synonymous with better academic achievement. Let’s delve into the advantages of shorter school days and how they could be implemented.

Curious about how shorter school days might impact students? Recent studies suggest they could be beneficial. Explore the nuances of who these changes affect and what the ideal length for a school day might be by watching this informative video. It delves into the latest research and expert opinions, offering a comprehensive look at this important educational topic.

1. Boost in Academic Performance

Discover an intriguing approach to school timing that might just make mornings easier for parents of teenagers. Some English schools are experimenting with starting classes later in the day, allowing teens extra sleep in the morning. Graham Satchell visits one such school to explore this innovative trial. Watch his report to see the impact of this change and whether it could become a more widespread practice.

Surprisingly, shorter school days have been linked to improved academic performance. Research by the National Bureau of Economic Research reveals that students in schools with shorter days often score higher on standardized tests. This improvement is attributed to enhanced focus and more effective information retention, as shorter days reduce cognitive overload.

Research conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research has shown that shorter school days can lead to improved academic performance. The study found that students attending schools with shorter days often scored higher on standardized tests than those in schools with longer days.

This improvement in academic performance is thought to result from students being able to focus better and retain information more effectively, as shorter school days help reduce cognitive overload. This research supports the idea that reducing the length of the school day could be beneficial for students academically.

Why it’s important: Enhanced academic performance is crucial for students’ educational and career prospects. Shorter school days can lead to better focus and more effective information retention, reducing cognitive overload. Improved academic outcomes are essential for students’ self-esteem, future learning opportunities, and overall success in life.

2. Improved Mental Health and Well-being

Explore the inspiring journey of Hailey Hardcastle, a University of Oregon freshman and student mental health advocate, in this video. Learn about her influential work on passing House Bill 2191, allowing mental health days for students, and her efforts in promoting student advocacy and innovative solutions to teenage mental challenges.

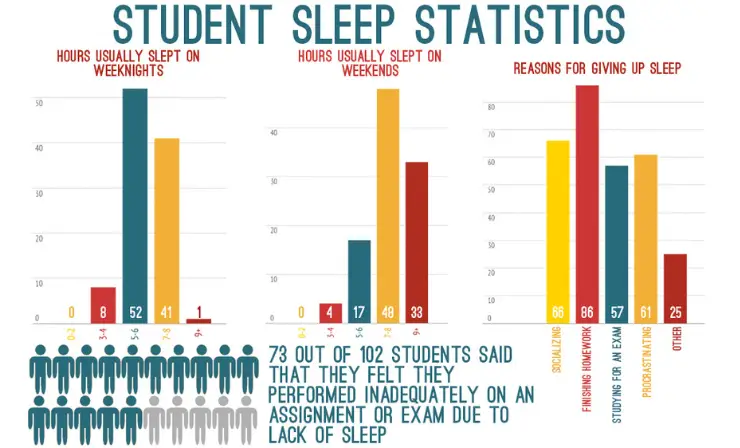

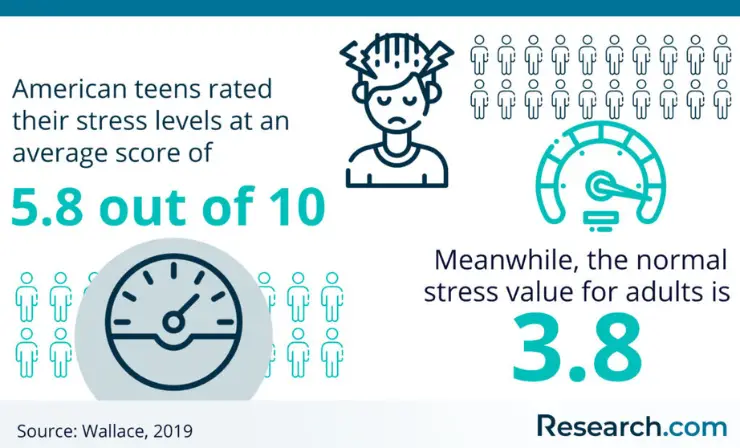

Extended school hours can adversely affect students’ mental health, leading to fatigue, stress, and burnout. Shortening the school day can offer students much-needed downtime, fostering better mental health and increased motivation. This break from academic pressures is crucial for emotional and psychological well-being.

Research supports the idea that shorter school days can positively impact students’ mental health and well-being. For instance, a study by the RAND Corporation, as discussed in an article from The Daily Iowan, found that a four-day school week improved students’ sleep, resulting in them feeling less tired. This change also offered students a day of rest, contributing to better mental health outcomes.

The study highlighted that students with a four-day school week experienced benefits in both their learning experience and mental health, suggesting that reduced school hours can enhance overall student well-being. This research aligns with the notion that shorter school days can provide crucial downtime for students, reducing stress and improving their mental health.

Why it’s important: Students’ mental health and well-being are vital for their overall development. Long school days can lead to fatigue, stress, and burnout, negatively impacting mental health. Shorter school days provide necessary downtime for relaxation and recharging, leading to improved mental health and increased motivation. This is crucial for students’ emotional resilience and ability to cope with academic pressures.

Dive into the compelling “ 8 Reasons Why Students Should Have Mental Health Days: A Research-Based Analysis ” to understand the importance of mental health in academic settings. This article offers a thorough, evidence-based exploration of why mental health days are crucial for student well-being and academic success, making a strong case for their inclusion in educational policies.

3. Enrichment Through Extracurricular Activities

With more free time, students can engage in extracurricular activities that foster skills beyond the academic realm. Participation in sports, arts, and clubs contributes to holistic development, offering experiences that are invaluable for personal growth. Moreover, additional family time strengthens familial bonds and provides emotional support.

Discover the significance of extracurricular activities in this engaging video. It delves into why these activities are essential for personal and educational development, especially for young students. It is a great resource for parents, educators, and students alike to understand the value of these pursuits beyond the classroom.

Research has consistently shown that participation in extracurricular activities offers significant benefits for students, enhancing their social, emotional, and academic development. According to a publication by the Center for Responsive Schools, extracurricular activities instill values such as teamwork, responsibility, and a sense of community.

They are also proven to boost school attendance, academic success, and aspirations for continuing education beyond high school. Additionally, these activities lead to healthier lifestyle choices, such as avoiding drug use and maintaining a healthy body weight, thereby contributing to students’ overall emotional well-being and interpersonal skills (Center for Responsive Schools, 2020).

Watch Cori as she explains the crucial role of extracurricular activities in the college preparation process. This video offers valuable insights into how these activities enhance college applications and contribute to student development. A must-see for students planning their academic future.

Another study , as summarized on the European Commission website and conducted by RAND, emphasizes the role of extracurricular activities in fostering social inclusion, particularly for children from disadvantaged and vulnerable backgrounds. These activities, ranging from sports clubs to music and educational groups, enable children to become active citizens in their community and develop soft skills such as self-esteem and resilience.

The study highlights that although current research on the specific benefits of extracurricular activities is fragmented, there is a recognized potential for these activities to support social inclusion and offer diverse benefits to children participating in them (RAND Corporation, 2021).

Why it’s important: Extracurricular activities play a significant role in holistic development. They foster skills beyond academics, such as teamwork, creativity, and leadership. More free time allows students to engage in these activities, contributing to their personal growth and development of valuable life skills. Participation in sports, arts, and clubs enriches students’ educational experiences and prepares them for diverse life situations.

4. Reduction in Stress and Burnout

The stress and exhaustion associated with long school days can lead to student burnout, affecting both motivation and academic performance. Shorter school days can alleviate this stress, promoting a healthier balance between academic responsibilities and personal life. This balance is key to maintaining enthusiasm for learning and overall student well-being.

Check out this insightful video where Carley shares her experience with school-related stress, offering a unique perspective that compares her situation to someone who longs for educational opportunities. This video sheds light on the real issue of stress levels among students and prompts viewers to think differently about the pressures of academic life.

Research on the impact of shorter school days on student stress and burnout suggests that reducing the length of the school week can have positive effects on students’ well-being. A study conducted on the four-day school week in Colorado found a generally positive relationship between the four-day school week and academic achievement, which indirectly points to reduced stress and burnout.

The study indicated that the schedule change could lead to better attendance and potentially more focused instruction time, contributing to improved performance and reduced stress for students (Education Finance and Policy, MIT Press).

Uncover surprising insights in ‘7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives ‘. This article provides a thought-provoking analysis of homework’s impact on students, offering evidence-based arguments and exploring alternative educational strategies for effective learning.

Why it’s important: Reducing stress and burnout is essential for maintaining students’ enthusiasm for learning and overall well-being. The pressure and exhaustion from long school days can lead to decreased motivation and academic performance. Shorter school days can help establish a healthier work-life balance for students, enhancing their productivity and engagement in both academic and personal endeavors.

5. Enhanced Teacher Well-being and Performance

Shorter school days not only benefit students but also provide vital rest and rejuvenation for teachers. In contrast to the brief periods in college or university, school teaching can be more demanding. Allowing teachers adequate rest time, even within a shorter school timeframe, keeps them energized and prepared for effective teaching.

A well-rested teacher can plan engaging and fun activities, enhancing student engagement and learning experiences. This approach aligns with broader educational research that underscores the importance of teacher well-being as a critical factor in delivering quality education and fostering a positive learning environment.

I recommend watching this insightful video that delves into the reasons behind teachers’ fatigue and the benefits of shorter school days. It highlights how demanding the current educational system can be for educators, leading to a state of exhaustion. Interestingly, the video also presents the idea that shorter school days could be a game-changer, offering teachers more time to unwind and reducing their workload. This approach could significantly improve the well-being and effectiveness of educators.

Research by RAND Corporation has explored the effects of shorter school weeks, particularly the four-day school week, on both students and teachers. It was found that teachers reported feeling less burned out and missed fewer instructional days due to illness or exhaustion with the shorter week. This schedule change also allowed them more time to prepare for the upcoming week and to engage in personal activities.

Why it’s important: Addressing teacher burnout and stress is crucial for maintaining a high-quality education system. The RAND Corporation’s study on the four-day school week highlights that reduced working hours can significantly improve teachers’ well-being and job satisfaction. This is important because teachers’ mental health directly affects their ability to engage with students, plan effective lessons, and create a positive learning environment. By improving teacher well-being, schools can enhance the overall educational experience for students.

6. Effective Homework Management in Shorter School Days

Long school days combined with a plethora of extracurricular activities can lead to students tackling their homework late into the night. Adopting shorter school days, however, could provide a solution. This change allows students to partake in additional activities while ensuring they have enough time for homework, thereby balancing their academic and personal lives.

This informative video examines the impact of excessive homework on teen stress levels, highlighting how shorter school days not only reduce stress but also provide more time for homework completion. It’s a concise yet insightful exploration of the balance between academic demands and student well-being.

Research on the implications of shorter school days points to positive outcomes in homework management. For example, a study on the four-day school week in Colorado found a positive association with academic performance, indirectly suggesting a reduction in homework-related stress. The study indicated that a condensed school week could result in better attendance and more efficient classroom time, leading to improved performance and less pressure for students to complete homework late at night (Education Finance and Policy, MIT Press).

Why it’s important: Ensuring students have adequate time for homework without the burden of overly long school days is essential for their well-being and academic success. Shorter school days can help establish a healthier balance, enhancing students’ ability to manage their academic responsibilities effectively and maintain their enthusiasm for learning.

In practice, implementing shorter school days would require a reevaluation of current educational models, focusing on quality over quantity in terms of instructional time. This approach encourages efficiency in teaching methods and prioritizes student health and personal development as integral components of educational success. The move towards shorter school days represents a progressive step in adapting education systems to better meet the needs of today’s students.

Evaluating the Challenges of Shorter School Days and Addressing Concerns

Addressing the concerns around the concept of shorter school days, there are several reasons why school days should not be shorter that are often brought up.

1. Impact on Working Parents

Shorter school days can disrupt the schedules of working parents, who often rely on traditional school hours for consistent childcare. This shift could necessitate alternative childcare arrangements, leading to increased stress and financial strain due to the costs of additional childcare or after-school programs.

In the United States, the shift to four-day school weeks in some districts has significantly affected working parents. Parents, especially mothers, have faced challenges in adjusting their work schedules and finding affordable childcare for the additional day off. This change has sometimes resulted in decreased labor income for mothers due to the need to provide childcare or arrange for additional care.

Counterargument: Flexibility and Quality Time for Families In response to this challenge, shorter school days can actually offer more flexible and quality time with children. Communities can adapt by providing enriched after-school programs, potentially reducing the financial burden on individual families. These programs can offer valuable learning experiences outside the traditional classroom setting, being a collaborative effort between schools, local businesses, and community organizations.

2. Costs and Logistics for Schools

Implementing shorter school days may lead to increased financial demands on schools, such as the need for extra staff for supervision or changes in transportation schedules. These logistical adjustments could result in significant additional expenses for schools.

Schools transitioning to shorter school days often incur additional expenses related to staffing and transportation. For example, schools may need to hire more staff to supervise students during after-school programs or adjust their transportation schedules to accommodate the new school hours, leading to increased operational costs.

Counterargument: Long-term Financial Benefits for Schools Despite the initial costs, shorter school days can lead to decreased operational costs, such as utilities and maintenance expenses, thereby offering long-term financial benefits. Additionally, a more focused and efficient school day can lead to better allocation of resources towards enhancing educational quality.

3. Possible Reduction in Instructional Time

There is a concern that shorter school days might lead to a decrease in the amount of instructional time available, potentially affecting the quality of education and the ability to meet curriculum standards.

Concerns about a reduction in instructional time with shorter school days are evident in various education systems. For instance, some schools have had to restructure their curriculums and teaching methods to ensure that essential learning outcomes are still achieved within the shortened school day. This challenge requires innovative approaches to maintain the quality of education.

Counterargument: Enhanced Learning Quality Contrary to this concern, a reduction in instructional time does not necessarily equate to a decrease in learning quality. Shorter school days can lead to more focused and engaged learning sessions, where quality of instruction is more impactful than quantity. Innovative teaching methods and technologies can ensure curriculum standards are met efficiently within a shorter timeframe, potentially improving learning outcomes and student well-being.

In conclusion, while transitioning to shorter school days presents certain challenges, these can be effectively addressed through community collaboration, innovative educational strategies, and a focus on the quality rather than the quantity of schooling. This approach can lead to a more balanced, effective, and enriching education system.

A Look at Successful Shorter School Day Models Around the World

As the debate around the length of the school day continues, it’s essential to look at successful models worldwide to understand the potential benefits of shorter school days. This part of the article “4 Reasons Why School Days Should Be Shorter” examines various international models where shorter school days have been implemented effectively.

The Finnish Model

Finland’s education system stands out for its shorter school days and a strong emphasis on quality education. Finnish students start school at age seven and have school days lasting only about 4-5 hours. Despite this, they rank highly in international assessments like PISA (Program for International Student Assessment). This success is attributed to a curriculum that focuses on student well-being, less homework, and minimal standardized testing, fostering an environment conducive to learning and creativity.

Renowned for its focus on student well-being and less formal structure, Finnish teachers often emphasize the importance of play and individualized attention. They have the autonomy to adjust their teaching methods to suit the needs of each student, which is a key factor in the high performance of Finnish students in international assessments.

Explore how Finland has managed to consistently outperform in education on a global scale. This video delves into the success of Finnish schools, offering insights that could inspire improvements in educational systems worldwide.

The French Model

In France, the school day typically lasts for 6 hours with a substantial two-hour lunch break. French schools also adopt a four-day school week, which has shown success in reducing student stress and improving academic performance. This model balances academic work with ample time for relaxation, socializing, and physical activity.

French educators often highlight the benefits of this model in promoting a balanced approach to education, where students have ample time for socializing, physical activities, and relaxation, contributing to their overall well-being and academic performance.

Discover how France is revolutionizing its educational system in this fascinating video titled “French Education: Reinventing the Idea of School.” Delve into the innovative changes and approaches being adopted in French schools that are transforming the traditional concepts of learning and teaching.

The UAE Model

The United Arab Emirates has been considering shorter school weeks, partly inspired by Finland’s approach. The goal is to focus on quality education without unnecessarily extending school hours. This approach aims to prevent student anxiety and overload, acknowledging the importance of a balanced education that includes time for relaxation and extracurricular activities.

Educators in the UAE focus on the quality of education and the holistic development of students, aiming to reduce stress and anxiety while providing a well-rounded educational experience.

Watch this engaging video to understand how the UAE is placing a strong emphasis on educational reform. It highlights the nation’s commitment to improving its education sector, a vital component of its broader development goals. This video offers insights into the strategic efforts and initiatives underway in the UAE to enhance its educational landscape.

The Japanese Model

The Japanese school model is unique, particularly in its approach to the length of the school day. Typically, a school day in Japan runs from 8:30 am to around 3:00 pm, but this can vary. Some schools have shorter days, especially for younger students. The school day generally includes various classes, lunchtime, and cleaning time, where students participate in cleaning their school environment. This model emphasizes not only academic learning but also life skills and community involvement.