A Qualitative Exploration of Collegiate Student-Athletes’ Constructions of Health

- Bradley Crocker McGill University

- Lindsay R Duncan, Dr. McGill University

Collegiate student athletes are faced with unique challenges as they are often forced to negotiate between demanding social, athletic, and academic roles. These competing priorities can put student athletes at greater risk for experiencing physical and psychological health problems than their non-athlete peers. To better understand the underlying behaviours and lifestyle factors leading to these negative outcomes, we must consider how they think about health. The purpose of this study was to examine how student athletes conceptualize health in the Canadian context, and to examine how they formulate these understandings. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 actively-competing collegiate student athletes from nine varsity sports at two academic institutions, and data were analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Participants constructed health holistically, with particular emphasis on physical and mental domains over social well-being. The quality of one’s physical health was equated in many ways with athletic capacity, as was the quality of mental health to a lesser degree. Participants discussed a variety of sources from which they drew health ideas, but sport experiences were commonly cited as particularly significant and formative. Findings can inform future research into health conceptualizations of other university student populations, and may inform further inquiry into how health ideas manifest into behaviour. Recommendations are provided for collegiate sport administrators including placing heavier emphasis on mental health resources, and improving support while athletes are acclimating to the demanding lifestyle of varsity sport.

Copyright (c) 2020 Bradley Crocker, Lindsay R Duncan

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

Copyright is held by the authors.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Make a Submission

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Special Issues

Title IX and Its Future in Shaping Inclusive Excellence in College Sport

The Myles Brand Era at the NCAA: A Tribute and Scholarly Review

Most popular articles this month

Steele et al. A Systematic Literature Review on the Academic and Athletic Identities of Student-Athletes

Gould et al. Sources and Consequences of Athletic Burnout among College Athletes

Scott et al. In-Season vs. Out-of-Season Academic Performance of College Student-Athletes

Crocker et al. A Qualitative Exploration of Collegiate Student-Athletes’ Constructions of Health

Osborne The Myth of the Exploited Student-Athlete

This electronic publication is supported by the

University of Kansas Libraries

Engaging Undergraduate Student-Athletes in Research and Publication Opportunities

Authors: Erin B. Jensen 1 , Desislava Yordanova, Lauren Denhard, Kira Zazzi, Jose Mejia, Timothy Shar, Julia Iseman, Tucker Hoeniges, and Madison Mitchell

1 Department of English, Belmont Abbey College, Belmont, NC, USA

Corresponding Author: Erin B. Jensen, PhD 100 Belmont-Mount Holly Road Belmont, NC, 28210 [email protected]

Erin B. Jensen, PhD, is an Associate Professor of English at Belmont Abbey College in Belmont, NC.

Desislava Yordanova majored in biology and was on the Acro-tumbling team. She is in a Masters in Public Health program.

Lauren Denhard is majoring in criminal justice and minoring in writing. She is a member of the golf team.

Kira Zazzi is a marketing major and was on the cycling team.

Jose Meji is majoring in economics and finance and was on the golf team.

Timothy Shar is majoring in math and was on the soccer team.

Julia Iseman was a psychology major and a member of the triathlon team, cross-country team, and track and field team. She plans to pursue a Masters in Psychology

Tucker Hoeniges is majoring in business and is a member of the cycling team.

Madison Mitchell majored in marketing and was a member of the field hockey team.

Universities and colleges are increasing opportunities for undergraduate research and publication for students; less studied is how to engage and encourage student-athletes to participate in such activities. Student-athletes often do not engage in undergraduate research activities due to time constraints of practicing and competing on their respective athletic teams and their full-time enrollment in college classes. This case study focuses on the experiences of eight undergraduate student-athletes and their faculty mentor who decide to co-author an article (this specific one) about their experiences in pursuing undergraduate research and publication. Through the experience of writing this article, we argue that undergraduate student-athletes can succeed in undergraduate research and publication, but are more successful when working with a mentor. We provide suggestions for what worked best for us to be able to be involved in this project. We also discuss the benefits to our own academic achievements and our increased confidence in our writing and research skills.

Key Words : Student-athletes, mentoring, undergraduate research, publishing

INTRODUCTION

Increasingly, research and publications at the undergraduate level is being encouraged by colleges and universities [1-16]. Colleges and universities are adding undergraduate research conferences, undergraduate journal article publishing opportunities, opportunities for lab work, and many other options for undergraduate students to become more involved in research [1-6]. The benefits of such opportunities have been well documented and include having students develop better writing skills [2, 10, 13, 14], increase ability to think, learn, and work independently [2, 10,13], develop mentoring relationships with faculty [4, 6, 10, 17], experience the rewards of designing a project, making discoveries, and sharing findings [2, 14, 18, 20], and be better prepared for graduate school [13, 14, 17]. Most of this research focuses more generally on undergraduate students without specifically focusing on student-athletes.

The research is less clear about ways to specifically encourage student-athletes to be involved in such opportunities [6-7, 12,20]. Student-athletes are often considered to be too busy with their respective sports to be recruited into research or to be able to participate in research and publication opportunities [7, 20]. There is even less research on how to encourage freshman to become involved in undergraduate research and even less on encouraging freshman student-athletes [6, 18].

To address these gaps in the research, we have written about our experiences as freshman student-athletes involved in undergraduate research and publishing opportunities. Our collective “we” represents eight freshman student-athletes and our English professor and indicates our shared contributions to the article. There are a few exceptions to our collective use of “we,” but those specific quotes are connected to the individual who wrote the quote.

During the initial conversations about co-authoring an article together about our experiences with undergraduate research, Jensen was our professor. Throughout the process of writing and revising this article, she has been our mentor and our co-author. We recognize that readers of our article may assume that our comments about Jensen are influenced by her being our professor and that she has influential power over us in regards to her position as a professor. However, the student co-authors, would disagree with such statements and knew we could leave the project at any time and there would be no negative consequences. We all felt supported to write about our experiences and our thoughts without undue influence from Jensen.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

These questions served as our guiding questions during this case study.

- What are ways to facilitate student-athletes being engaged in research and publication opportunities?

- What are the challenges freshman student-athletes experience when getting involved in undergraduate research?

- What are the experiences of freshman student-athletes involved in writing an article for publication?

PARTICIPANTS

As we have already indicated, we collectively wrote this article. However, we wanted to provide more introduction to the nine authors and their information at the time of writing this article. Erin Jensen was the professor of the freshman writing courses that all of us students were enrolled in. She is a former student-athlete (swimming) and also helps to coach the college triathlon team. Desislava Yordanova, originally from Bulgaria, is a pre-med/biology major who is on the acro and tumbling team; she is the only student with prior experience in undergraduate research as she was involved in a year-long mentorship in high school where she where she worked in a lab and participated in writing a research paper based on the lab results. José Mejía (economics and finance) is from Guatemala and was on the golf team. Timothy Shar (math major) was on the soccer team and is a refugee from Burma. Kira Zazzi (marketing major) was on the cycling team and is a first-generation college student. Tucker Hoeniges (business major) is also on the cycling team and Lauren Denhard (criminal justice major) is on the golf team. Julia Iseman (psychology major) was on the cross-country, track and field, and triathlon teams and Madison Mitchell (marketing major) was on the field hockey team.

This case study utilizes participants narratives to co-write an article about the experiences of freshman student-athletes and their professor mentor involved in the publication process. Such a methodology suited this project as it provided a “complex, [and] detailed understanding” of the students’ experiences [5] (p. 40). In 1995, Stake [19] makes the argument that participants in qualitative research “should play a major role directing as well as acting in case study research” (p. 115). Other researchers emphasize that case study design focuses on “the complexity of social interactions expressed in daily life and by the meanings that the participants themselves attribute to these interactions” [15] (p. 2). A case study methodology allowed us to more fully explore the complexity of student-athlete participation from the participants themselves.

The project started in the freshman writing courses that Jensen taught. In her classes, she taught a unit on undergraduate research, undergraduate conferences, and undergraduate publication opportunities as she found that most students are unaware of such opportunities. Jensen has students read several articles about the benefits of getting involved in undergraduate research and participate in several in-class assignments about the benefits of undergraduate research, and then offers to mentor students through the process of submitting their freshman writing research essays to undergraduate journals.

We, the students, were interested in having her mentor us through our submitting our individual essays and she had agreed to help as much as she could. As she began to have these conversations with us, she began to realize that we all had very valid concerns about having the time to really be able to submit individual projects. We all talked to her about our concerns of being student-athletes and trying to balance being athletes, students, working, and having time to participate in such a project. When the eight of us decided to co-author with Jensen, we decided to just work on writing this article and not focus on our individual projects as none of us felt that we had the time to be involved in multiple projects. We also felt that we would gain more understanding about research and the publication process by working closely with Jensen than trying to pursue our own projects with only a week’s worth of knowledge.

We set up meetings to talk with each other about what we needed to do with to write this article. Due to our athletic and class schedule, it was impossible to find a time to all meet together, so we ended up with several separate meetings and Jensen made sure to be at all of the meetings to help provide continuity of information. As Jensen has found, part of being a mentor to student-athletes is the need to be flexible with meetings and realize that sometimes multiple meetings need to happen to best meet the needs of the student-athletes. In the initial meetings with all of us, Jensen reviewed what we all had said to her in our individual meetings with her. With our permission, she had taken notes, and she shared these answers with everyone about why we were interested in undergraduate publications, why what our concerns were, and why we wanted to co-author with her as our mentor. She created a handout that included these ideas, a tentative timeline, and next steps for the process. We appreciated seeing our responses to why we all were co-authoring an article with her and we all appreciated knowing what the steps to writing an article included as most of us had no experience in publication.

After the initial meetings, we all decided to write about our experiences in learning about undergraduate research and publishing opportunities. Jensen agreed to be the person that would collect and organize what we wrote. She also agreed to be in the mentor position and lead us through the process. We all agreed to write about these topics and to email them to her within a month. After two weeks, she sent everyone a follow-up email reminding us of the deadline and asking if anyone had any questions or wanted additional clarification about what they could write about. A few of us emailed in response to these follow-up emails and asked additional questions or asked for additional clarification about what they could write about. In addition to her follow-up email, she also talked to us in class (as we all had her for our freshman composition class) and she met with some of us for additional time during her office hours. Because of time constraints, most of us wrote our initial drafts on various busses as we were traveling to different competitions, we wrote during our required student-athlete study hour, or during random pieces of time, but all of us submitted our initial document before the month deadline as we all were committed to this project and wanted to get our responses to her as soon as we could. Jensen was impressed with our efforts and that she did not need to remind anyone about the deadline.

After students emailed her their individual responses, she read through what had been submitted and saw places that needed more explanation or specifics. She then emailed most of us and included specific requests for additional information that she would like to see added to our document. In her email, she acknowledged that we were probably feeling intimidated by the process. Most of us were intimidated by the project and the thought of other people reading what we had written and we appreciated that she acknowledged our feelings and reassured us that she was there to both mentor and to help with the writing of the article. We trusted Jensen and that she would guide us through the process which is why we had submitted our initial document, but we still were not sure what we should include and so some of us wrote about more general ideas about our experiences. We found that Jensen in her follow-up requests, asked us very specific questions that helped guide our responses and we all responded to her requests for more specific information.

After receiving the additional specific information, she read through all the submissions again and then worked on combining all eight of these documents into a rough draft. We all wrote about our experiences in different ways and each of the eight documents was very different in terms of style, structure, vocabulary, format, etc. She wanted to make sure that all of our voices and experiences were a main component of this article and while she needed to make changes to the documents, she did not want to lose what we were saying in our own words. Jensen was able to merge our experiences together, combine our thoughts, and create a rough draft that read like a cohesive article. We, the student co-authors, recognize how difficult that must have been and that Jensen as an experienced English professor and editor had the skills necessary to achieve this accomplishment.

After she combined our individual eight documents into a rough draft of the essay, she posted the essay in a shared Google doc that we all had access to. She emailed us and requested that we read through the rough draft and make track changes comments on the document. She requested we finish our comments within two weeks. Some of us started adding comments as soon as we saw her email and some of us waited until the deadline to add comments. Jensen sent us a reminder email after a week and then another reminder email on the day that the deadline had been set. We commented on the content and organization as well as marked any places where we thought there should be more detail added. In our freshman composition class, we had all been trained on how to conduct a peer-review as Jensen required all students to peer-review each other’s essays and so we all knew what we needed to do as we peer-reviewed this article. Already having peer-review skills was helpful as we were not intimidated by the process of making comments on this rough draft as we wanted to improve the document. The entire process was a collaborative effort between all nine of us.

During our commenting stage, Jensen emailed us and suggested we think about the main themes that we wanted to include in the Results section. On the rough draft version, we had the results section, but it was not as organized as it could be. As none of the student authors had experience in finding themes, we asked Jensen to take the lead and include the themes that she saw in the data. Jensen used our conversations with her and our initial documents to come up with several themes that she saw in the results. She is a qualitative researcher and she followed the researchers recommendation that the themes “capture something about the essential quality of what is represented” [23] (p. 58). As she read through the rough draft and her co-authors words, she coded for themes. As we all revised the rough draft, we were able to add more under each theme that had been identified.

After we all had the opportunity to make comments on the rough draft in Google Docs, we began the process of revising the article. Revision was a collaborative process where we all participated in various ways. Some of us chose to take a on a larger role in the process, focusing on how to negotiate issues of a co-authored article, including how to create a voice for such an article and how to fit together parts of the article that had been written by different co-authors. Other students focused more the areas where their experiences were highlighted and worked on clarifying their intentions. Jensen also participated in the revision process and making track changes comments that we responded to as well. We all worked on identifying revisions that needed to be made and then negotiating how to best make such changes. A more revised rough draft started to emerge from this revision process, and we started making more editing changes as opposed to content changes. All of us provided editing help as well. When we had mutually decided that the article was at a state that needed more refined editing, we agreed to have Jensen make those final round of edits as she was our professor and we trusted that she would be the best person to make such edits. After she made final edits to the Google doc, she emailed us and asked for all of us to read the article again and to indicate whether we agreed that it was ready for publication. When she received confirmation from all of us, she submitted the article to this journal.

Our voices as student-athlete co-authors are throughout this article, but especially in the results section as our initial drafts form the basis of this section. We include in the results section, our thoughts and experiences about the need for mentorship through undergraduate research and publication as we agree that having Jensen to mentor us is one of the reasons why this article even exists. For readability reasons, we decided to use quotes from our initial documents and have used our names to indicate the connection between the student co-author and their respective quote. The following section focuses on our argument about what is needed to engage student-athletes in research.

3.1. Student Perceptions of Role of Faculty Mentor

Critical to the success of this project was the faculty mentor who, as we and previous research have established, guided the co-authors through the process and became the coach for the team. Jensen recognizes the position of power that she is in as her students wrote about her role in the process at the same time that they had her as a professor.

The student-athletes identified the critical mentoring role that Jensen provided, with Mitchell expressing how important it was to be provided with a “valuable mentor and to have a relationship with a faculty member” to navigate this process. This corroborates the findings that “intentional mentoring [is an] important aspect of promoting participation in research for students” [8]. As multiple student-athletes indicated, Jensen was that mentor, and she was the person that found the call for papers, recruited us, organized our individual papers into a rough draft, edited our edits, and then submitted this final version. She, just like the coaches of our athletic teams, was essential to the success and management of the project. Iseman emphasized Jensen’s important role in describing why she participated in the project: “I am participating in this article because my professor, who initially informed me about undergraduate research in the first place, specifically asked me to. This made it much easier for me, as it provided me with a direct opportunity to get published, that I knew wasn’t going to take all of my time to write, as it was going to be a co-authored publication.” Hoeniges also emphasize the important of the faculty mentor: “Having a professor encourage publishing and help with the process is nice, after all, it’s a pretty big jump and some students just need a push.” Mejía added, “I viewed this as an opportunity to expand my limits and do something that would seem uncomfortable at first but would most certainly pay off in the future, and that is one of the main reasons people get involved in publication. Without thinking about it twice, when the opportunity of co-authoring a paper came up through my composition professor, I said yes.” Throughout the process, Jensen was there to respond to emails or email us with updates. She provided the “push” and the “mentorship” to continue through the process.

Jensen also created team unity among all the student-athletes, holding us together with her commitment to the project and her concern for all of us. As researchers argue, undergraduate research “has the ability to create strong academic (e.g., with faculty, fellow students, peer mentors, and campus resources) and social networks (e.g., peers of similar backgrounds in a small class size and co-curricular events together)” [18] (p. 13). Several of us were talking about this project during athlete study hall, and we were talking about why we agreed to be involved. The main reason we agreed was because of how much we like having Jensen as a professor and that she is already a mentor to us. Jensen is one of those professors that genuinely cares about her students and genuinely wants to help her students succeed both in her classes as well as in all their classes. During our discussion, we all said that we agreed to participate in this project because we knew that Jensen would continue to be an excellent mentor, that she would actually guide us through the process, and that she would continue to mentor us after this project was finished.

As student-athletes, we looked to Jensen to take care of any of our concerns. One of our biggest concerns was the issue of time because we were all busy with our respective training regimes, and Jensen was balancing a full teaching schedule with committee work and creating a new minor for the college. As researchers write, “Time is the most limiting factor for research productivity and teaching effectiveness” [10] (p. 2). Most of us described our situations in similar ways, and in our early work on this project, we wrote a lot about our different schedules and how little time any of us had to spend doing anything other than required schoolwork and athletics. We all could relate to Hoeniges’s comments about his normal daily schedule including only eight free hours a week as all of his other hours were full of training, competing, going to classes, homework, eating, and sleeping. As Hoeniges expressed, “To be brutally honest, in this free time, the last thing on my mind is that I need to be writing a paper for something that isn’t due for one of my classes.” However, he and the rest of us all worked on this project during that small amount of free time because the benefits of writing this article were enough to convince us all to participate, and we knew that Jensen was aware of the time limitations and did all she could to make the time commitment manageable. Jensen reassured us several times through email and conversations that because we were co-authoring, the amount of work would be spread among all of us. We appreciate that researchers have recognized that undergraduates have “less experience,” not “less talent” than graduate students and that their schedules make it difficult to find sufficient blocks of time needed to focus on developing scientific writing skills” [10] (p. 3). Jensen also recognized these realities, helping us gain the experience needed to engage in undergraduate research and publication and helping us find the time to do so.

Some of the co-authors had individual concerns related to the overall undergraduate research and publication process and Jensen was always willing to address and answer those concerns. Iseman described her concern about how to find a journal to target for possible publication and she felt overwhelmed by that task. “For me, the issue wasn’t doing the writing or finding time in my busy schedule. The issue was finding a journal in the first place that would publish me and that I wanted to write for.” She went on to argue that professors should become mentors and help student navigate this process. Jensen spent considerable time and effort helping student-athletes understand the process so they could move forward and target appropriate journals, providing students with the tools so that more undergraduate students, including student-athletes, could get published.

Other than Yordanova and Jensen, this is our first experience with writing an article for publication. Jensen helped us to have a good first research or publication experience, which is important to the entire process. Jensen often told us, “having a positive first publication experience made a difference” [11] in her own experience with publishing. As she explained, her first publication was a relatively smooth process, while her second publication was the exact opposite and required major revisions that took several years. She told us of the value of a positive first experience: “Knowing that I had already been published helped me keep revising my second article and helped keep me believing in myself enough to make it through the much longer process” [11]. She frequently told us that she wanted students to have a positive first publication experience so that they too could keep submitting their work and continue to have confidence in their writing. We have all benefitted from her continuing mentorship and have had a good experience in our first publication opportunity.

A faculty mentor is a needed part of undergraduate research and publication for student-athletes. This article exists because of the time and effort Jensen spent in valuing us, encouraging us to write, and then in mentoring us through the process of being published. When the final version was submitted to the journal, our mentorship experiences with Jensen has continued and will continue through the rest of our undergraduate years as she continues to encourage the mentoring relationship. One of the most positive pedagogical benefits to undergraduate research is establishing a mentorship situation between faculty and students [25]. Jensen appreciates this opportunity to be a mentor to her students and plans to continue such a mentorship beyond this project. She is currently helping several of us with our own individual essays that we are thinking of getting published. We value having a relationship with a professor that enjoys mentoring us through the challenges of being student-athletes.

3.2 Flexibility and Deadlines Needed for Student-Athlete Projects

In our experiences working on the writing of this article, we argue that student-athlete projects need flexibility to be part of any research-based project and need deadlines as well. All of us student-athletes were committed to being involved in this writing project, but we let Jensen know that our priorities were to our sports competitions and to our other classes. Jensen reassured all of us that she understood our priorities and could be as flexible as needed with the writing of the article. As Iseman wrote, “I am a freshman cross country and triathlon athlete and am involved in many other ways at my college, so my schedule is often school, sports, homework, with little time in between for much else…I don’t have much time to write.” We could all relate to Iseman and agreed that having flexibility was important. Jensen had multiple meetings with all of us, but we never had a single meeting that everyone had to be there as that would not have worked with any of our schedules. So, Jensen had the same introductory meeting multiple times to accommodate our schedules. This type of flexibility was necessary to the project as we could use the little free time we had to work on the project, but that we didn’t have to all come together to communicate.

Another flexibility piece of the project was using a shared Google doc to make all edits and changes. We could all access the Google doc at any time and make our comments when it worked best for us. As Shar wrote, “I liked to access the [Google] document whenever I could and make comments whenever it worked for me.” We would agree with him that one of the reasons this article was able to be written by nine different people with nine different schedules was because of the flexibility that using a shared document created.

Seemingly opposite from flexibility is the idea of the importance of deadlines to the project. We all discovered that having deadlines was helpful to have a goal to aim for. Jensen reassured us though that these deadlines could be as flexible as needed to accommodate our respective schedules. Interestingly, in our case, all of us were early in contributing our work for all deadlines that were set for the project. Even though we all met every deadline, we did appreciate having deadlines and goals for when our contributions were due. This is another example of how important it was to have a mentor as Jensen set the deadlines for us to meet. As student-athletes, we are goal-driven people and having set deadlines was helpful. As Shar wrote, “I liked having a deadline and knowing when I needed to finish my writing.”

When Jensen asked us to write about our experiences with learning about undergraduate research, all of us student-athletes had breaks in our respective schedules and so had some time to participate. After the first couple of weeks, several of our respective sports teams became involved in conference championship tournaments and we were spending a lot of time traveling to destinations. Traveling to conferences made it difficult to have much time to focus on any projects that were not directly connected to class work or sports practice. As Denhard wrote, “My goal is to publish during the short offseason my team has because it would allow me enough time to focus solely on the project, and not get distracted with other assignments.” We communicated with Jensen and let her know of our athletic competitions and our limited time to be involved. Jensen was able to navigate all of our schedules by being flexible with meetings and having the process of writing an article be mainly created through a shared Google doc.

As we reflect on the experience of writing this article and pursuing our own individual research projects, we found that we needed flexibility to be built into the project to accommodate our schedules. But, we also appreciated having deadlines as we were more successful for having a deadline as a goal to be working towards.

3.3. Pedagogical and Personal Benefits to Students

Participating in undergraduate research and publishing through the writing of this journal article has provided both pedagogical and personal benefits for all of us, both student-athletes and the faculty mentor. Research on undergraduate publishing has found that such opportunities can support students’ academic success, help students develop critical thinking and writing skills, and prepare students for graduate school and provide them with experience that graduate programs value [1-17]. As student-athletes involved in this project, we have identified numerous benefits of our participation, including a positive impact on our academic success and expanded plans for graduate school, an improvement in our writing skills and confidence in those skills, and increased desire to participate in writing- and research-related activities. We understand much more about academic research and publication, and many of us are pursuing additional writing opportunities.

3.3.1. Expanded Academic Success and Graduate School Preparation

Research on undergraduate publication has found that such an experience has a positive impact on students’ academic success, and we experienced similar results. As researchers argue, “involvement in undergraduate research and undergraduate research programs increases students’ academic achievement and retention rates” [21] (p. 2) and the argument that “early participation in collaborative research with faculty as a freshman or sophomore appears to be positively related to self-reported gains in independent analytical development” [16] (p. 383). Additional research found that undergraduate research helps students to “students to think broadly and synthetically, to apply concepts across different situations, and be open to new ways of thinking” [10]. A similar argument was made “Students who participate in undergraduate research early on report significant gains in the ability to (1) think analytically and logically; (2) put ideas together, and note similarities and differences between ideas; (3) learn on their own and to find information they need to complete a task” [16] (p. 385). As student-athletes, most of us agreed with the research as we found this experience to be helpful in how we thought about academics and about ourselves. As student-athletes we were still concerned about the time requirements needed for this publication opportunity and wondered if this project would negatively impact our grades. Several of us wrote about how we typically completed most of our homework on the bus as we traveled to competitive events, but when we agreed to participate in this project, had to spend some of that travel time completing work for this article, and we wondered if that would negatively impact our grades. We were surprised to realize that all of us not only passed our freshman composition courses, but also were all able to maintain good GPAs while being involved in this project.

Our academic success during our freshman year has long-term implications for many of us, and our participation in undergraduate research and publication also helped us in terms of our post-graduation and career plans. In our classes with Jensen, she had us think about what we would be doing after graduation and how we were preparing for that future. Several of us had considered furthering our education in graduate school, but thought that it was not a realistic goal because we feared we were not smart enough or academically advanced enough to be successful in graduate school. In our initial introduction to undergraduate publishing, we read an article about how helpful publication could be when applying for graduate school and for funding in graduate school. However, until we actually went through the research steps, we did not think we were capable of such project. Now, almost all of us are thinking about and planning on attending graduate school. We recognize that we have gained a lot of experience and knowledge about the research process, which helps to prepare us for graduate studies. As Yordanova explained, “Undergraduate publishing is an amazing opportunity that students should take advantage of as it can be the tipping point of getting into a dream school, job, or opportunity when being compared to other applicants; whether for graduate school, medical school, internships, or even highly experienced job opportunities.”

In our initial individual drafts for this article, many of us reflected on our graduate school plans, some not feeling confident about such plans and others seeing the role that this research and publication project could play in those plans. Some identified plans for graduate school, but felt unsure about the future and recognized that publication could help them achieve those plans. Hoeniges identified the value of having publications: “I actually need to be publishing high quality, in-depth research articles for the career pathway I am looking to pursue. Being an exercise science major entails lots of research papers, and in order to get accepted into a high-level graduate degree program, I need to be publishing as much as I can to show my interest in the field, considering I won’t have a four-year degree in exercise science, as our college does not offer the degree.” Denhard echoed these statements when she wrote about wanting to attend law school, “I have thought about getting individually published because I plan on attending law school after I graduate. I think that this will benefit me because I can write about a topic that I am passionate about from the criminal justice field. I think that publishing would allow me to improve my writing skills and research skills that I will need for law school.” Yordanova identified the critical role that undergraduate research could play in her career plans for a time after her collegiate sports career:

As a student-athlete, I know how difficult it is to manage my practice and class schedules; however, putting in the work to publish research that I am passionate about is equally, if not more, important than a competition. In the end, students do not graduate with a bachelor’s in a sport, and for example, gymnastics is not a lifelong career; therefore, one has to devote themselves to educational opportunities. Though sports help tremendously in college, when the real-world hits, after graduation, students need experience on their résumés, no matter how large or small it may be. Publishing any article is a huge accomplishment, showing how one manages their time and how passionate they are about excelling in their career.

Being involved in this undergraduate research project has helped us all realize we can be involved in academic research and maintain a good GPA and has given us the confidence to pursue graduate school.

3.3.2. Increased Confidence in Writing Skills

Another benefit of being part of a team and having a mentor through the research and publication process is our increased confidence in our writing abilities. Almost all of us initially wrote about not having much confidence in our writing abilities or in being able to write something that was “good enough” to be published. We included such statements as “I do not have confidence in my writing” or “why would someone want to read what I wrote” or “I am self-conscious of my writing.” Jensen was able to guide us through the process of research and publication and help us realize that we actually do have the writing skills to participate in writing an article that could be published. We all participated in the writing of this article and found the confidence necessary to participate. Shar explained how the whole process helped him gain confidence in his writing: “As English being my second language, I have always struggled with writing, especially with grammar. And when I have an idea of what to write about, I lack the confidence of, or am afraid of, what others might think of my writing capabilities. Being one of the co-authors of this undergraduate research has given me more confidence in my writing abilities.” Another student-athlete described how his whole attitude about writing had changed through taking a class from Jensen and then having the opportunity to participate in this project:

I feel everything that I have done in your class and for this journal article has made me a much more confident writer. I have a very hard time writing, and taking your classes has helped me be able to write papers in ways that I could never do before. Thanks for helping me become more confident within my writing.

Through researching and publishing our work, we have now gained additional knowledge about the research and publishing process and feel more connected to the academic world. We can now better understand and relate to professors when they speak about their research experiences. Iseman indicated that she felt motivated by gaining experience and understanding of the research process: “It’s a motivating factor to try and get published. It’s nice to see that as undergraduates, we are still able to participate in research and activities that I always assumed were reserved for professionals.” Denhard expressed it slightly differently, but with the same ideas by describing her undergraduate publishing as being “a tool that many people do not have on their résumé” and that such a tool would help in the future. We feel empowered to now be part of the professional field and to know that our opinions are vital to that field. Zazzi added to these thoughts as she wrote, “In a sense, it feels like a reward and recognition for all of the hard work that I put in on a daily basis as a student-athlete.” We agree that undergraduate publication does feel like a reward for our hard work and effort and provides us with opportunities to gain more confidence in our writing abilities.

3.3.3. Increased Writing-Focused Activity

In addition to helping us achieve academic success and increase confidence in our writing skills, this experience has also provided us with the understanding and motivation to pursue other research- and writing-focused opportunities. During our initial rough drafts, Mitchell had written about feeling self-conscious about her writing, but she just accepted the invitation to become the co-editor of the school newspaper. Iseman and Denhard also joined the newspaper and are staff writers. Others of us have decided to minor in Writing (Jensen is the creator of this minor and the advisor), and we will continue to take courses in writing and develop our writing skills.

Other student-athletes have found additional ways to expand their writing and research activities. Zazzi decided to combine her love of cycling and writing by applying for and successfully obtaining an internship with a female empowerment cycling blog called Shred Girls . As Zazzi wrote about the experience, she included that she appreciated having a mentor to “inspire and push” her. As part of her internship, she writes articles, conducts interviews, and has her own column. Jensen, laughingly, liked to tell us that one of the benefits of publication is then being able to cite yourself in an article. So, we decided to cite Zazzi in her article for Liv Cycling on the importance of writing every day. Zazzi described her nightly writing ritual: “Every night before I go to sleep, I write in my journal. I write about anything: my goals, how my day went, or thoughts that I can’t get off of my mind. I find that I sleep better, and overall feel happier, because of this” [25]. Writing is a great way to express ourselves and our feelings, and we are glad that Zazzi has found a medium that values both her writing ability and her athletic self. Yordanova also expressed the impact of this experience on her writing: “I have found a new love for writing. I have always loved writing essays, but now I love the idea of publishing and thinking more critically about my work. I have actually begun writing in a journal now, as there is so much information constantly running through my mind, and maybe one day I will get more of my personal work published.”

Based on our experience writing this article, several of us decided to submit our own individually written essays to a variety of undergraduate research journals. At the time of this submission, Yordanova has had one article accepted for publication and was waiting to hear about another article that she had submitted [23]. Denhard is currently waiting to hear about a research article she had written about golf, and Mitchell is also waiting to hear back on a literature analysis essay. Yordova, Denhard, and Iseman all participated in the first college specific undergraduate conference (also created by Jensen) and created posters about their topics. We are committed to the publication process and know firsthand the numerous benefits of participating in that process.

Undergraduate research and publishing have been shown to be beneficial to students and to lead to positive outcomes. Most of the current research on undergraduate research has not specifically focused on student-athletes and the unique challenges that they face in being involved in undergraduate research opportunities. As eight undergraduate student-athletes and one mentorship-focused college professor discovered, student athletes can be successful when engaging in undergraduate research and publishing. Such a project needs to have a mentor who has a good relationship with the students and can lead them through the process. Without the guidance, editing, and revising capabilities of that mentor, this article would not have been written. While all of the student-athlete co-authors contributed to the article, they needed the faculty mentor to keep them motivated and to bring their ideas and suggestions together into a cohesive article. It was the mentor who kept co-authors involved in every step of the process, but also the one who stayed up all night to finish the final edits on the article.

Despite some challenges around having all co-authors participate in the revision process or in contributing to the literature review, the overall benefits of the project certainly outweighed those issues. The co-authors expressed feeling more confidence in their writing abilities and their academic goals. They expressed appreciation for having an opportunity to learn about the research and publishing process and gaining information that would be useful for them in the future and for their post-graduation goals. Several co-authors decided to submit their own individual essays to a variety of undergraduate journals and are waiting to hear back. Other co-authors sought out writing opportunities through internships, writing for the newspaper, and deciding to pursue a minor in writing. Mejía summed up the experience from a student-athlete’s perspective:

Before I knew it, the paper was done and I was in the process of becoming a co-author of my first publication, a highlight of my freshman year in college. Some keywords to remember, the life of a student-athlete is no easy task but the desire to get better as a student-athlete in everything we do, every day; We are all here because we love to strive and want to see how much we can push our boundaries in everything from the sport we compete in to every hard subject we take, to every lift we attend, and even everything we put into our bodies. Publication, in that case, was no different; Even if the difficulty increases, student-athletes, if encouraged by teachers to pursue certain opportunities, will most likely take them because of the mentality, all in all, each one of us possesses. Therefore, publication as a student-athlete may not be an easy task, but under adequate conditions and proper guidance, the desire to say yes and hold an achievement beyond our required tasks is a no brainer.

Student-athletes can succeed in undergraduate research and publication with the support and guidance of a faculty mentor who is committed to the process and is willing to put in the time and effort to help us through the process. Such benefits are both short- and long-term, and they are significant, ranging from contributing to students’ academic success and focus on graduate school, to increasing confidence in their writing, expanding their awareness of the academic research process and motivating them to become part of this process. Student-athletes should not be excluded from the process because of their perceived busy schedules; instead, they should be mentored and guided through that process.

- Becker, M. (2020). Research for all: Creating opportunities for undergraduate research experiences across the curriculum.” APSA Preprints . doi: 10.33774/apsa-2020-30zr5.

- Bresee, A., & Kinkead, J. (2022). The trajectory of an undergraduate researcher. Pedagogy , 22 (1), 143-147.

- Burks, R. L. & Chumchal, M. M. (2009). To co-author or not to co-author: How to write, publish, and negotiate issues of authorship with undergraduate research student. Science Signaling 2 (94), DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.294tr3

- Burns, S. & Ware, M. E. (2008). Undergraduate student research journals: Opportunities for and benefits from publication . In R. L. Miller, E. Balcetis, S. T. Barney, B. C. Beins, S. R. Burns, R. Smith, & M. E. War (Eds.). Developing, promoting, & sustaining the undergraduate research experience in psychology (pp. 253-256).

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Devita, J.M. et al. (2020). Engaging in faculty mentored research with student-athletes: A successful case at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. PURM 9 (1) .

- Ferguson. T. et al. (2020). Student-Athletes Narratives about Engagement in Undergraduate Research . PURM 9 (1).

- Govindan, B., et al. (2020). Fear of the CURE: A beginner’s guide to overcoming barriers in creating a course-based undergraduate research experience. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 21 (2), 1-8.

- Haegar, H, et al. (2015). Participation in undergraduate research at minority-serving institutions. PURM 4 (1).

- Ishiyama, J. (2002). Does early participation in undergraduate research benefit social science and humanities majors? Journal of College Student Development, 36 (3), 380–386.

- Jensen, E. B. (2019). Selecting a journal . In J.R. Gallagher & D.N. DeVoss (Editors), Explanation Points: Publishing in Rhetoric and Composition. University of Colorado / Utah State University Press.

- Kim, J. H. (2015). Understanding narrative inquiry: The crafting and analysis of stories as research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Kinkead, J. (2021). The Empirical strikes back: A RAD research methods class for undergraduate English students. CEA Forum 49 (1).

- Little, C. (2020). Undergraduate research as a student engagement springboard: Exploring the longer-term reported benefits of participation in a research conference. Educational Research , 62 (2), 229-245.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2006). Designing qualitative research (4 th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Morales, D. X., et al. (2017). Faculty motivation to mentor students through undergraduate research programs: A study of enabling and constraining factors. Research in Higher Education, 58 (5), 520-544.

- Nolan, J. et al. (2020) Mentoring undergraduate research in statistics: Reaping the benefits and overcoming the barriers. Journal of Statistics Education, 28 (2), 140-153, DOI: 10.1080/10691898.2020.1756542

- Saucier, D.A. and Martens, A.L. (2015) Simplify-Guide-Progress-Collaborate: A model for class-based undergraduate research. PURM 4 (1).

- Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Stokowski, S. (2020). Faculty role models: The perceived mentorship of student-athletes. PURM 9 (1).

- Taylor, M. and Jensen, K.S.H. (2018). Engaging and supporting a university press scholarly community. Publications, 6(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6020013

- Vengadasalam , S. S. (2020). Publish or perish! Sharing best practices for a writing instructor led “Writing for Publication” Course. Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature, 1 (2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.46809/jcsll.v1i2.13

- Willig, C. (2008). Introducing qualitative research in psychology: Adventures in theory and method (2 nd ed.) . Berkshire, UK: Open University Press

- Yordanova, D. (2021). Response to “On Telling the Story” by Jorge Vinales . Queen City Writers Journal, 10 (1).

- Zazzi, K. (2020). Time to refocus. Liv Active . https://www.liv-cycling.com/us/liv-active .

Share this:

Share this article, choose your platform.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, stress in academic and athletic performance in collegiate athletes: a narrative review of sources and monitoring strategies.

- 1 School of Kinesiology, Applied Health and Recreation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, United States

- 2 Department of Kinesiology, California State University, Fullerton, CA, United States

- 3 Department of Kinesiology, Point Loma Nazarene University, San Diego, CA, United States

- 4 Department of Kinesiology and Sport Sciences, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States

College students are required to manage a variety of stressors related to academic, social, and financial commitments. In addition to the burdens facing most college students, collegiate athletes must devote a substantial amount of time to improving their sporting abilities. The strength and conditioning professional sees the athlete on nearly a daily basis and is able to recognize the changes in performance and behavior an athlete may exhibit as a result of these stressors. As such, the strength and conditioning professional may serve an integral role in the monitoring of these stressors and may be able to alter training programs to improve both performance and wellness. The purpose of this paper is to discuss stressors experienced by collegiate athletes, developing an early detection system through monitoring techniques that identify the detrimental effects of stress, and discuss appropriate stress management strategies for this population.

Introduction

The college years are a period of time when young adults experience a significant amount of change and a variety of novel challenges. Academic performance, social demands, adjusting to life away from home, and financial challenges are just a few of the burdens college students must confront ( Humphrey et al., 2000 ; Paule and Gilson, 2010 ; Aquilina, 2013 ). In addition to these stressors, collegiate athletes are required to spend a substantial amount of time participating in activities related to their sport, such as attending practices and training sessions, team meetings, travel, and competitions ( Humphrey et al., 2000 ; López de Subijana et al., 2015 ; Davis et al., 2019 ; Hyatt and Kavazis, 2019 ). These commitments, in addition to the normal stress associated with college life, may increase a collegiate-athlete's risk of experiencing both physical and mental issues ( Li et al., 2017 ; Moreland et al., 2018 ) that may affect their overall health and wellness. For these reasons, it is essential that coaches understand the types of stressors collegiate athletes face in order to help them manage the potentially deleterious effects stress may have on athletic and academic performance.

Strength and conditioning coaches are allied health care professionals whose primary job is to enhance fitness of individuals for the purpose of improving athletic performance ( Massey et al., 2002 , 2004 , 2009 ). As such, many universities and colleges hire strength and conditioning coaches as part of their athletic staff to help athletes maximize their physical potential ( Massey et al., 2002 , 2004 , 2009 ). Strength and conditioning coaches strive to increase athletic performance by the systematic application of physical stress to the body via resistance training, and other forms of exercise, to yield a positive adaptation response ( Massey et al., 2002 , 2004 , 2009 ). For this reason, they need to understand and to learn how to manage athletes' stress. Additionally, based on the cumulative nature of stress, it is important that both mental and emotional stressors are also considered in programming. It is imperative that strength and conditioning coaches are aware of the multitude of stressors collegiate athletes encounter, in order to incorporate illness and injury risk management education into their training programs ( Radcliffe et al., 2015 ; Ivarsson et al., 2017 ).

Based on the large number of contact hours strength and conditioning coaches spend with their athletes, they are in an optimal position to assist athletes with developing effective coping strategies to manage stress. By doing so, strength and conditioning coaches may be able to help reach the overarching goal of improving the health, wellness, fitness, and performance of the athletes they coach. The purpose of this review article is to provide the strength and conditioning professional with a foundational understanding of the types of stressors collegiate athletes may experience, and how these stressors may impact mental health and athletic performance. Suggestions for assisting athletes with developing effective coping strategies to reduce potential physiological and psychological impacts of stress will also be provided.

Stress and the Stress Response

In its most simplistic definition, stress can be described as a state of physical and psychological activation in response to external demands that exceed one's ability to cope and requires a person to adapt or change behavior. As such, both cognitive or environmental events that trigger stress are called stressors ( Statler and DuBois, 2016 ). Stressors can be acute or chronic based on the duration of activation. Acute stressors may be defined as a stressful situation that occurs suddenly and results in physiological arousal (e.g., increase in hormonal levels, blood flow, cardiac output, blood sugar levels, pupil and airway dilation, etc.) ( Selye, 1976 ). Once the situation is normalized, a cascade of hormonal reactions occurs to help the body return to a resting state (i.e., homeostasis). However, when acute stressors become chronic in nature, they may increase an individual's risk of developing anxiety, depression, or metabolic disorders ( Selye, 1976 ). Moreover, the literature has shown that cumulative stress is correlated with an increased susceptibility to illness and injury ( Szivak and Kraemer, 2015 ; Mann et al., 2016 ; Hamlin et al., 2019 ). The impact of stress is individualistic and subjective by nature ( Williams and Andersen, 1998 ; Ivarsson et al., 2017 ). Additionally, the manner in which athletes respond to a situational or environmental stressor is often determined by their individual perception of the event ( Gould and Udry, 1994 ; Williams and Andersen, 1998 ; Ivarsson et al., 2017 ). In this regard, the athlete's perception can either be positive (eustress) or negative (distress). Even though they both cause physiological arousal, eustress also generates positive mental energy whereas distress generates anxiety ( Statler and DuBois, 2016 ). Therefore, it is essential that an athlete has the tools and ability to cope with these stressors in order to have the capacity to manage both acute and chronic stress. As such, it is important to understand the types of stressors collegiate athletes are confronted with and how these stressors impact an athlete's performance, both athletically and academically.

Literature Search/Data Collection

The articles included in this review were identified via online databases PubMed, MEDLINE, and ISI Web of Knowledge from October 15th 2019 through January 15th 2020. The search strategy combined the keywords “academic stress,” “athletic stress,” “stress,” “stressor,” “college athletes,” “student athletes,” “collegiate athletes,” “injury,” “training,” “monitoring.” Duplicated articles were then removed. After reading the titles and abstracts, all articles that met the inclusion criteria were considered eligible for inclusion in the review. Subsequently, all eligible articles were read in their entirety and were either included or removed from the present review.

Inclusion Criteria

The studies included met all the following criteria: (i) published in English-language journals; (ii) targeted college athletes; (iii) publication was either an original research paper or a literature review; (iv) allowed the extraction of data for analysis.

Data Analysis

Relevant data regarding participant characteristics (i.e., gender, academic status, sports) and study characteristics were extracted. Articles were analyzed and divided into two separate sections based on their specific topics: Academic Stress and Athletic Stress. Then, strategies for monitoring and workload management are discussed in the final section.

Academic Stress

Fundamentally, collegiate athletes have two major roles they must balance as part of their commitment to a university: being a college student and an athlete. Academic performance is a significant source of stress for most college students ( Aquilina, 2013 ; López de Subijana et al., 2015 ; de Brandt et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2019 ). This stress may be further compounded among collegiate athletes based on their need to be successful in the classroom, while simultaneously excelling in their respective sport ( Aquilina, 2013 ; López de Subijana et al., 2015 ; Huml et al., 2016 ; Hamlin et al., 2019 ). Davis et al. (2019) conducted surveys on 173 elite junior alpine skiers and reported significant moderate to strong correlations between perceived stress and several variables including depressed mood ( r = 0.591), sleep disturbance ( r = 0.459), fatigue ( r = 0.457), performance demands ( r = 0.523), and goals and development ( r = 0.544). Academic requirements were the highest scoring source of stress of all variables and was most strongly correlated with perceived stress ( r = 0.467). Interestingly, it was not academic rigor that was viewed by the athletes as the largest source of direct stress; rather, the athletes surveyed reported time management as being their biggest challenge related to academic performance ( Davis et al., 2019 ). This further corroborates the findings of Hamlin et al. (2019) . The investigators reported that during periods of the academic year in which levels of perceived academic stress were at their highest, students had trouble managing sport practices and studying. These stressors were also associated with a decrease in energy levels and overall sleep quality. These factors may significantly increase the collegiate athlete's susceptibility to illness and injury ( Hamlin et al., 2019 ). For this reason, coaches should be aware of and sensitive to the stressors athletes experience as part of the cyclical nature of the academic year and attempt to help athletes find solutions to balancing athletic and academic demands.

According to Aquilina (2013) , collegiate athletes tend to be more committed to sports development and may view their academic career as a contingency plan to their athletic career, rather than a source of personal development. As a result, collegiate athletes often, but certainly not always, prioritize athletic participation over their academic responsibilities ( Miller and Kerr, 2002 ; Cosh and Tully, 2014 , 2015 ). Nonetheless, scholarships are usually predicated on both athletic and academic performance. For instance, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) requires collegiate athletes to achieve and maintain a certain grade point average (GPA). Furthermore, they are also often required to also uphold a certain GPA to maintain an athletic scholarship. The pressure to maintain both high levels of academic and athletic performance may increase the likelihood of triggering mental health issues (i.e., anxiety and depression) ( Li et al., 2017 ; Moreland et al., 2018 ).

Mental health issues are a significant concern among college students. There has been an increased emphasis placed on the mental health of collegiate athletes in recent years ( Petrie et al., 2014 ; Li et al., 2017 , 2019 ; Reardon et al., 2019 ). Based on the 2019 National College Health Assessment survey from the American College Health Association (ACHA) consisting of 67,972 participants, 27.8% of college students reported anxiety, and 20.2% reported experiencing depression which negatively affected their academic performance ( American College Health Association American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II, 2019 ). Approximately 65.7% (50.7% males and 71.8% females) reported feeling overwhelming anxiety in the past 12 months, and 45.1% (37.1% males and 47.6% females) reported feeling so depressed that it was difficult for them to function. However, only 24.3% (13% males and 28.4% females) reported being diagnosed and treated by a professional in the past 12 months. Collegiate athletes are not immune to these types of issues. According to information presented by the NCAA, many certified athletic trainers anecdotally state that anxiety is an issue affecting the collegiate-athlete population ( NCAA, 2014 ). However, despite the fact that collegiate athletes are exposed to numerous stressors, they are less likely to seek help at a university counseling center than non-athletes ( NCAA, 2014 ), which could be related to stigmas that surround mental health services ( NCAA, 2014 ; Kaier et al., 2015 ; Egan, 2019 ). This not only has significant implications related to their psychological well-being, but also their physiological health, and consequently their performance. For instance, in a study by Li et al. (2017) it was found that NCAA Division I athletes who reported preseason anxiety symptoms had a 2.3 times greater injury incidence rate compared to athletes who did not report. This same study discovered that male athletes who reported preseason anxiety and depression had a 2.1 times greater injury incidence, compared to male athletes who did not report symptoms of anxiety and depression. ( Lavallée and Flint, 1996 ) also reported a correlation between anxiety and both injury frequency and severity among college football players ( r = 0.43 and r = 0.44, respectively). In their study, athletes reporting high tension/anxiety had a higher rate of injury. It has been suggested that the occurrence of stress and anxiety may cause physiological responses, such as an increase in muscle tension, physical fatigue, and a decrease in neurocognitive and perception processes that can lead to physical injuries ( Ivarsson et al., 2017 ). For this reason, it is reasonable to consider that academic stressors may potentiate effects of stress and result in injury and illness in collegiate athletes.

Periods of more intense academic stress increase the susceptibility to illness or injury ( Mann et al., 2016 ; Hamlin et al., 2019 ; Li et al., 2019 ). For example, Hamlin et al. (2019) investigated levels of perceived stress, training loads, injury, and illness incidence in 182 collegiate athletes for the period of one academic year. The highest levels of stress and incidence of illness arise during the examination weeks occurring within the competitive season. In addition, the authors also reported the odds ratio, which is the occurrence of the outcome of interest (i.e., injury), based off the given exposure to the variables of interest (i.e., perceived mood, sleep duration, increased academic stress, and energy levels). Based on a logistic regression, they found that each of the four variables (i.e., mood, energy, sleep duration, and academic stress) was related to the collegiate athletes' likelihood to incur injuries. In summary, decreased levels of perceived mood (odds ratio of 0.89, 0.85–0.0.94 CI) and sleep duration (odds ratio of 0.94, 0.91–0.97 CI), and increased academic stress (odds ratio of 0.91, 0.88–0.94 CI) and energy levels (odds ratio of 1.07, 1.01–1.14 CI), were able to predict injury in these athletes. This corroborates Mann et al. (2016) who found NCAA Division I football athletes at a Bowl Championship Subdivision university were more likely to become ill or injured during an academically stressful period (i.e., midterm exams or other common test weeks) than during a non-testing week (odds ratio of 1.78 for high academic stress). The athletes were also less likely to get injured during training camp (odds ratio of 3.65 for training camp). Freshmen collegiate athletes may be especially more susceptible to mental health issues than older students. Their transition includes not only the academic environment with its requirements and expectations, but also the adaptation to working with a new coach and teammates. In this regard, Yang et al. (2007) found an increase in the likelihood of depression that freshmen athletes experienced, as these freshmen were 3.27 times more likely to experience depression than their older teammates. While some stressors are recurrent and inherent in academic life (e.g., attending classes, homework, etc.), others are more situational (e.g., exams, midterms, projects) and may be anticipated by the strength and conditioning coach.

Athletic Stress

The domain of athletics can expose collegiate athletes to additional stressors that are specific to their cohort (e.g., sport-specific, team vs. individual sport) ( Aquilina, 2013 ). Time spent training (e.g., physical conditioning and sports practice), competition schedules (e.g., travel time, missing class), dealing with injuries (e.g., physical therapy/rehabilitation, etc.), sport-specific social support (e.g., teammates, coaches) and playing status (e.g., starting, non-starter, being benched, etc.) are just a few of the additional challenges collegiate athletes must confront relative to their dual role of being a student and an athlete ( Maloney and McCormick, 1993 ; Scott et al., 2008 ; Etzel, 2009 ; Fogaca, 2019 ). Collegiate athletes who view the demands of stressors from academics and sports as a positive challenge (i.e., an individual's self-confidence or belief in oneself to accomplish the task outweighs any anxiety or emotional worry that is felt) may potentially increase learning capacity and competency ( NCAA, 2014 ). However, when these demands are perceived as exceeding the athlete's capacity, this stress can be detrimental to the student's mental and physical health as well as to sport performance ( Ivarsson et al., 2017 ; Li et al., 2017 ).

As previously stated, time management has been shown to be a challenge to collegiate athletes. The NCAA rules state that collegiate athletes may only engage in required athletic activities for 4 h per day and 20 h/week during in-season and 8 h/week during off-season throughout the academic year. Although these rules have been clearly outlined, the most recent NCAA GOALS (2016) study reported alarming numbers regarding time commitment to athletic-related activities. Data from over 21,000 collegiate athletes from 600 schools across Divisions I, II, and III were included in this study. Although a breakdown of time commitments was not provided, collegiate athletes reported dedicating up to 34 h per week to athletics (e.g., practices, weight training, meetings with coaches, tactical training, competitions, etc.), in addition to spending between 38.5 and 40 h per week working on academic-related tasks. This report also showed a notable trend related to athletes spending an increase of ~2 more athletics-related hours per week compared to the 2010 GOALS study, along with a decrease of 2 h of personal time (from 19.5 h per week in 2010 to 17.1 in 2015). Furthermore, ~66% of Division I and II and 50% of Division III athletes reported spending as much or more time in their practices during the off-season as during the competitive season ( DTHOMAS, 2013 ). These numbers show how important it is for collegiate athletes to develop time management skills to be successful in both academics and athletics. Overall, most collegiate athletes have expressed a need to find time to enjoy their college experience outside of athletic obligations ( Paule and Gilson, 2010 ). Despite that, because of the increasing demand for excellence in academics and athletics, collegiate athletes' free time with family and friends is often scarce ( Paule and Gilson, 2010 ). Consequently, trainers, coaches, and teammates will likely be the primary source of their weekly social interactivity.

Social interactions within their sport have also been found to relate to factors that may impact an athlete's perceived stress. Interactions with coaches and trainers can be effective or deleterious to an athlete. Effective coaching includes a coaching style that allows for a boost of the athlete's motivation, self-esteem, and efficacy in addition to mitigating the effects of anxiety. On the other hand, poor coaching (i.e., the opposite of effective coaching) can have detrimental psychological effects on an athlete ( Gearity and Murray, 2011 ). In a closer examination of the concept of poor coaching practices, Gearity and Murray (2011) interviewed athletes about their experiences of receiving poor coaching. Following analysis of the interviews, the authors identified the main themes of the “coach being uncaring and unfair,” “practicing poor teaching inhibiting athlete's mental skills,” and “athlete coping.” They stated that inhibition of an athlete's mental skills and coping are associated with the psychological well-being of an athlete. Also, poor coaching may result in mental skills inhibition, distraction, insecurity, and ultimately team division ( Gearity and Murray, 2011 ). This combination of factors may compound the negative impacts of stress in athletes and might be especially important for in injured athletes.

Injured athletes have previously been reported to have elevated stress as a result of heightened worry about returning to pre-competition status ( Crossman, 1997 ), isolation from teammates if the injury is over a long period of time ( Podlog and Eklund, 2007 ) and/or reduced mood or depressive symptoms ( Daly et al., 1995 ). In addition, athletes who experience prolonged negative thoughts may be more likely to have decreased rehabilitation attendance or adherence, worse functional outcomes from rehabilitation (e.g., on measures of proprioception, muscular endurance, and agility), and worse post-injury performance ( Brewer, 2012 ).

Monitoring Considerations

In addition to poor coaching, insufficient workload management can hinder an athlete's ability to recover and adapt to training, leading to fatigue accumulation ( Gabbett et al., 2017 ). Excessive fatigue can impair decision-making ability, coordination and neuromuscular control, and ultimately result in overtraining and injury ( Soligard et al., 2016 ). For instance, central fatigue was found to be a direct contributor to anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer players ( Mclean and Samorezov, 2009 ). Introducing monitoring tools may serve as a means to reduce the detrimental effects of stress in collegiate athletes. Recent research on relationships between athlete workloads, injury, and performance has highlighted the benefits of athlete monitoring ( Drew and Finch, 2016 ; Jaspers et al., 2017 ).

Athlete monitoring is often assessed with the measuring and management of workload associated with a combination of sport-related and non-sport-related stressors ( Soligard et al., 2016 ). An effective workload management program should aim to detect excessive fatigue, identify its causes, and constantly adapt rest, recovery, training, and competition loads respectively ( Soligard et al., 2016 ). The workload for each athlete is based off their current levels of physical and psychological fatigue, wellness, fitness, health, and recovery ( Soligard et al., 2016 ). Accumulation of situational or physical stressors will likely result in day-to-day fluctuations in the ability to move external loads and strength train effectively ( Fry and Kraemer, 1997 ). Periods of increased academic stress may cause increased levels of fatigue, which can be identified by using these monitoring tools, thereby assisting the coaches with modulating the workload during these specific periods. Coaches who plan to incorporate monitoring and management strategies must have a clear understanding of what they want to achieve from athlete monitoring ( Gabbett et al., 2017 ; Thornton et al., 2019 ).

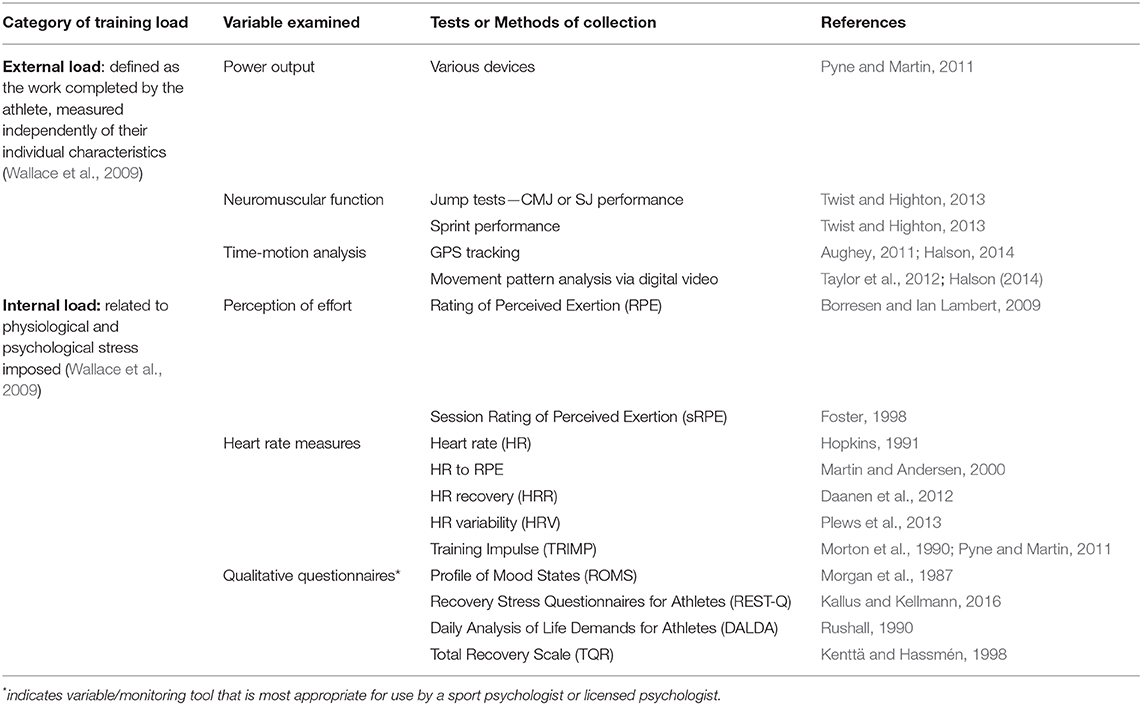

Monitoring External Loads

External load refers to the physical work (e.g., number of sprints, weight lifted, distance traveled, etc.) completed by the athlete during competition, training, and activities of daily living ( Soligard et al., 2016 ). This type of load is independent of the athlete's individual characteristics ( Wallace et al., 2009 ). Monitoring external loading can aid in the designing of training programs which mimic the external load demands of an athlete's sport, guide rehabilitation programs, and aid in the detection of spikes in external load that may increase the risk of injury ( Clubb and McGuigan, 2018 ).