Research Process: 8 Steps in Research Process

The research process starts with identifying a research problem and conducting a literature review to understand the context. The researcher sets research questions, objectives, and hypotheses based on the research problem.

A research study design is formed to select a sample size and collect data after processing and analyzing the collected data and the research findings presented in a research report.

What is the Research Process?

There are a variety of approaches to research in any field of investigation, irrespective of whether it is applied research or basic research. Each research study will be unique in some ways because of the particular time, setting, environment, and place it is being undertaken.

Nevertheless, all research endeavors share a common goal of furthering our understanding of the problem, and thus, all traverse through certain primary stages, forming a process called the research process.

Understanding the research process is necessary to effectively carry out research and sequence the stages inherent in the process.

How Research Process Work?

Eight steps research process is, in essence, part and parcel of a research proposal. It is an outline of the commitment that you intend to follow in executing a research study.

A close examination of the above stages reveals that each of these stages, by and large, is dependent upon the others.

One cannot analyze data (step 7) unless he has collected data (step 6). One cannot write a report (step 8) unless he has collected and analyzed data (step 7).

Research then is a system of interdependent related stages. Violation of this sequence can cause irreparable harm to the study.

It is also true that several alternatives are available to the researcher during each stage stated above. A research process can be compared with a route map.

The map analogy is useful for the researcher because several alternatives exist at each stage of the research process.

Choosing the best alternative in terms of time constraints, money, and human resources in our research decision is our primary goal.

Before explaining the stages of the research process, we explain the term ‘iterative’ appearing within the oval-shaped diagram at the center of the schematic diagram.

The key to a successful research project ultimately lies in iteration: the process of returning again and again to the identification of the research problems, methodology, data collection, etc., which leads to new ideas, revisions, and improvements.

By discussing the research project with advisers and peers, one will often find that new research questions need to be added, variables to be omitted, added or redefined, and other changes to be made. As a proposed study is examined and reexamined from different perspectives, it may begin to transform and take a different shape.

This is expected and is an essential component of a good research study.

Besides, examining study methods and data collected from different viewpoints is important to ensure a comprehensive approach to the research question.

In conclusion, there is seldom any single strategy or formula for developing a successful research study, but it is essential to realize that the research process is cyclical and iterative.

What is the primary purpose of the research process?

The research process aims to identify a research problem, understand its context through a literature review, set research questions and objectives, design a research study, select a sample, collect data, analyze the data, and present the findings in a research report.

Why is the research design important in the research process?

The research design is the blueprint for fulfilling objectives and answering research questions. It specifies the methods and procedures for collecting, processing, and analyzing data, ensuring the study is structured and systematic.

8 Steps of Research Process

Identifying the research problem.

The first and foremost task in the entire process of scientific research is to identify a research problem .

A well-identified problem will lead the researcher to accomplish all-important phases of the research process, from setting objectives to selecting the research methodology .

But the core question is: whether all problems require research.

We have countless problems around us, but all we encounter do not qualify as research problems; thus, these do not need to be researched.

Keeping this point in mind, we must draw a line between research and non-research problems.

Intuitively, researchable problems are those that have a possibility of thorough verification investigation, which can be effected through the analysis and collection of data. In contrast, the non-research problems do not need to go through these processes.

Researchers need to identify both;

Non-Research Problems

Statement of the problem, justifying the problem, analyzing the problem.

A non-research problem does not require any research to arrive at a solution. Intuitively, a non-researchable problem consists of vague details and cannot be resolved through research.

It is a managerial or built-in problem that may be solved at the administrative or management level. The answer to any question raised in a non-research setting is almost always obvious.

The cholera outbreak, for example, following a severe flood, is a common phenomenon in many communities. The reason for this is known. It is thus not a research problem.

Similarly, the reasons for the sudden rise in prices of many essential commodities following the announcement of the budget by the Finance Minister need no investigation. Hence it is not a problem that needs research.

How is a research problem different from a non-research problem?

A research problem is a perceived difficulty that requires thorough verification and investigation through data analysis and collection. In contrast, a non-research problem does not require research for a solution, as the answer is often obvious or already known.

Non-Research Problems Examples

A recent survey in town- A found that 1000 women were continuous users of contraceptive pills.

But last month’s service statistics indicate that none of these women were using contraceptive pills (Fisher et al. 1991:4).

The discrepancy is that ‘all 1000 women should have been using a pill, but none is doing so. The question is: why the discrepancy exists?

Well, the fact is, a monsoon flood has prevented all new supplies of pills from reaching town- A, and all old supplies have been exhausted. Thus, although the problem situation exists, the reason for the problem is already known.

Therefore, assuming all the facts are correct, there is no reason to research the factors associated with pill discontinuation among women. This is, thus, a non-research problem.

A pilot survey by University students revealed that in Rural Town-A, the goiter prevalence among school children is as high as 80%, while in the neighboring Rural Town-A, it is only 30%. Why is a discrepancy?

Upon inquiry, it was seen that some three years back, UNICEF launched a lipiodol injection program in the neighboring Rural Town-A.

This attempt acted as a preventive measure against the goiter. The reason for the discrepancy is known; hence, we do not consider the problem a research problem.

A hospital treated a large number of cholera cases with penicillin, but the treatment with penicillin was not found to be effective. Do we need research to know the reason?

Here again, there is one single reason that Vibrio cholera is not sensitive to penicillin; therefore, this is not the drug of choice for this disease.

In this case, too, as the reasons are known, it is unwise to undertake any study to find out why penicillin does not improve the condition of cholera patients. This is also a non-research problem.

In the tea marketing system, buying and selling tea starts with bidders. Blenders purchase open tea from the bidders. Over the years, marketing cost has been the highest for bidders and the lowest for blenders. What makes this difference?

The bidders pay exorbitantly higher transport costs, which constitute about 30% of their total cost.

Blenders have significantly fewer marketing functions involving transportation, so their marketing cost remains minimal.

Hence no research is needed to identify the factors that make this difference.

Here are some of the problems we frequently encounter, which may well be considered non-research problems:

- Rises in the price of warm clothes during winter;

- Preferring admission to public universities over private universities;

- Crisis of accommodations in sea resorts during summer

- Traffic jams in the city street after office hours;

- High sales in department stores after an offer of a discount.

Research Problem

In contrast to a non-research problem, a research problem is of primary concern to a researcher.

A research problem is a perceived difficulty, a feeling of discomfort, or a discrepancy between a common belief and reality.

As noted by Fisher et al. (1993), a problem will qualify as a potential research problem when the following three conditions exist:

- There should be a perceived discrepancy between “what it is” and “what it should have been.” This implies that there should be a difference between “what exists” and the “ideal or planned situation”;

- A question about “why” the discrepancy exists. This implies that the reason(s) for this discrepancy is unclear to the researcher (so that it makes sense to develop a research question); and

- There should be at least two possible answers or solutions to the questions or problems.

The third point is important. If there is only one possible and plausible answer to the question about the discrepancy, then a research situation does not exist.

It is a non-research problem that can be tackled at the managerial or administrative level.

Research Problem Examples

Research problem – example #1.

While visiting a rural area, the UNICEF team observed that some villages have female school attendance rates as high as 75%, while some have as low as 10%, although all villages should have a nearly equal attendance rate. What factors are associated with this discrepancy?

We may enumerate several reasons for this:

- Villages differ in their socio-economic background.

- In some villages, the Muslim population constitutes a large proportion of the total population. Religion might play a vital role.

- Schools are far away from some villages. The distance thus may make this difference.

Because there is more than one answer to the problem, it is considered a research problem, and a study can be undertaken to find a solution.

Research Problem – Example #2

The Government has been making all-out efforts to ensure a regular flow of credit in rural areas at a concession rate through liberal lending policy and establishing many bank branches in rural areas.

Knowledgeable sources indicate that expected development in rural areas has not yet been achieved, mainly because of improper credit utilization.

More than one reason is suspected for such misuse or misdirection.

These include, among others:

- Diversion of credit money to some unproductive sectors

- Transfer of credit money to other people like money lenders, who exploit the rural people with this money

- Lack of knowledge of proper utilization of the credit.

Here too, reasons for misuse of loans are more than one. We thus consider this problem as a researchable problem.

Research Problem – Example #3

Let’s look at a new headline: Stock Exchange observes the steepest ever fall in stock prices: several injured as retail investors clash with police, vehicles ransacked .

Investors’ demonstration, protest and clash with police pause a problem. Still, it is certainly not a research problem since there is only one known reason for the problem: Stock Exchange experiences the steepest fall in stock prices. But what causes this unprecedented fall in the share market?

Experts felt that no single reason could be attributed to the problem. It is a mix of several factors and is a research problem. The following were assumed to be some of the possible reasons:

- The merchant banking system;

- Liquidity shortage because of the hike in the rate of cash reserve requirement (CRR);

- IMF’s warnings and prescriptions on the commercial banks’ exposure to the stock market;

- Increase in supply of new shares;

- Manipulation of share prices;

- Lack of knowledge of the investors on the company’s fundamentals.

The choice of a research problem is not as easy as it appears. The researchers generally guide it;

- own intellectual orientation,

- level of training,

- experience,

- knowledge on the subject matter, and

- intellectual curiosity.

Theoretical and practical considerations also play a vital role in choosing a research problem. Societal needs also guide in choosing a research problem.

Once we have chosen a research problem, a few more related steps must be followed before a decision is taken to undertake a research study.

These include, among others, the following:

- Statement of the problem.

- Justifying the problem.

- Analyzing the problem.

A detailed exposition of these issues is undertaken in chapter ten while discussing the proposal development.

A clear and well-defined problem statement is considered the foundation for developing the research proposal.

It enables the researcher to systematically point out why the proposed research on the problem should be undertaken and what he hopes to achieve with the study’s findings.

A well-defined statement of the problem will lead the researcher to formulate the research objectives, understand the background of the study, and choose a proper research methodology.

Once the problem situation has been identified and clearly stated, it is important to justify the importance of the problem.

In justifying the problems, we ask such questions as why the problem of the study is important, how large and widespread the problem is, and whether others can be convinced about the importance of the problem and the like.

Answers to the above questions should be reviewed and presented in one or two paragraphs that justify the importance of the problem.

As a first step in analyzing the problem, critical attention should be given to accommodate the viewpoints of the managers, users, and researchers to the problem through threadbare discussions.

The next step is identifying the factors that may have contributed to the perceived problems.

Issues of Research Problem Identification

There are several ways to identify, define, and analyze a problem, obtain insights, and get a clearer idea about these issues. Exploratory research is one of the ways of accomplishing this.

The purpose of the exploratory research process is to progressively narrow the scope of the topic and transform the undefined problems into defined ones, incorporating specific research objectives.

The exploratory study entails a few basic strategies for gaining insights into the problem. It is accomplished through such efforts as:

Pilot Survey

A pilot survey collects proxy data from the ultimate subjects of the study to serve as a guide for the large study. A pilot study generates primary data, usually for qualitative analysis.

This characteristic distinguishes a pilot survey from secondary data analysis, which gathers background information.

Case Studies

Case studies are quite helpful in diagnosing a problem and paving the way to defining the problem. It investigates one or a few situations identical to the researcher’s problem.

Focus Group Interviews

Focus group interviews, an unstructured free-flowing interview with a small group of people, may also be conducted to understand and define a research problem .

Experience Survey

Experience survey is another strategy to deal with the problem of identifying and defining the research problem.

It is an exploratory research endeavor in which individuals knowledgeable and experienced in a particular research problem are intimately consulted to understand the problem.

These persons are sometimes known as key informants, and an interview with them is popularly known as the Key Informant Interview (KII).

Reviewing of Literature

A review of relevant literature is an integral part of the research process. It enables the researcher to formulate his problem in terms of the specific aspects of the general area of his interest that has not been researched so far.

Such a review provides exposure to a larger body of knowledge and equips him with enhanced knowledge to efficiently follow the research process.

Through a proper review of the literature, the researcher may develop the coherence between the results of his study and those of the others.

A review of previous documents on similar or related phenomena is essential even for beginning researchers.

Ignoring the existing literature may lead to wasted effort on the part of the researchers.

Why spend time merely repeating what other investigators have already done?

Suppose the researcher is aware of earlier studies of his topic or related topics . In that case, he will be in a much better position to assess his work’s significance and convince others that it is important.

A confident and expert researcher is more crucial in questioning the others’ methodology, the choice of the data, and the quality of the inferences drawn from the study results.

In sum, we enumerate the following arguments in favor of reviewing the literature:

- It avoids duplication of the work that has been done in the recent past.

- It helps the researcher discover what others have learned and reported on the problem.

- It enables the researcher to become familiar with the methodology followed by others.

- It allows the researcher to understand what concepts and theories are relevant to his area of investigation.

- It helps the researcher to understand if there are any significant controversies, contradictions, and inconsistencies in the findings.

- It allows the researcher to understand if there are any unanswered research questions.

- It might help the researcher to develop an analytical framework.

- It will help the researcher consider including variables in his research that he might not have thought about.

Why is reviewing literature crucial in the research process?

Reviewing literature helps avoid duplicating previous work, discovers what others have learned about the problem, familiarizes the researcher with relevant concepts and theories, and ensures a comprehensive approach to the research question.

What is the significance of reviewing literature in the research process?

Reviewing relevant literature helps formulate the problem, understand the background of the study, choose a proper research methodology, and develop coherence between the study’s results and previous findings.

Setting Research Questions, Objectives, and Hypotheses

After discovering and defining the research problem, researchers should make a formal statement of the problem leading to research objectives .

An objective will precisely say what should be researched, delineate the type of information that should be collected, and provide a framework for the scope of the study. A well-formulated, testable research hypothesis is the best expression of a research objective.

A hypothesis is an unproven statement or proposition that can be refuted or supported by empirical data. Hypothetical statements assert a possible answer to a research question.

Step #4: Choosing the Study Design

The research design is the blueprint or framework for fulfilling objectives and answering research questions .

It is a master plan specifying the methods and procedures for collecting, processing, and analyzing the collected data. There are four basic research designs that a researcher can use to conduct their study;

- experiment,

- secondary data study, and

- observational study.

The type of research design to be chosen from among the above four methods depends primarily on four factors:

- The type of problem

- The objectives of the study,

- The existing state of knowledge about the problem that is being studied, and

- The resources are available for the study.

Deciding on the Sample Design

Sampling is an important and separate step in the research process. The basic idea of sampling is that it involves any procedure that uses a relatively small number of items or portions (called a sample) of a universe (called population) to conclude the whole population.

It contrasts with the process of complete enumeration, in which every member of the population is included.

Such a complete enumeration is referred to as a census.

A population is the total collection of elements we wish to make some inference or generalization.

A sample is a part of the population, carefully selected to represent that population. If certain statistical procedures are followed in selecting the sample, it should have the same characteristics as the population. These procedures are embedded in the sample design.

Sample design refers to the methods followed in selecting a sample from the population and the estimating technique vis-a-vis the formula for computing the sample statistics.

The fundamental question is, then, how to select a sample.

To answer this question, we must have acquaintance with the sampling methods.

These methods are basically of two types;

- probability sampling , and

- non-probability sampling .

Probability sampling ensures every unit has a known nonzero probability of selection within the target population.

If there is no feasible alternative, a non-probability sampling method may be employed.

The basis of such selection is entirely dependent on the researcher’s discretion. This approach is called judgment sampling, convenience sampling, accidental sampling, and purposive sampling.

The most widely used probability sampling methods are simple random sampling , stratified random sampling , cluster sampling , and systematic sampling . They have been classified by their representation basis and unit selection techniques.

Two other variations of the sampling methods that are in great use are multistage sampling and probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling .

Multistage sampling is most commonly used in drawing samples from very large and diverse populations.

The PPS sampling is a variation of multistage sampling in which the probability of selecting a cluster is proportional to its size, and an equal number of elements are sampled within each cluster.

Collecting Data From The Research Sample

Data gathering may range from simple observation to a large-scale survey in any defined population. There are many ways to collect data. The approach selected depends on the objectives of the study, the research design, and the availability of time, money, and personnel.

With the variation in the type of data (qualitative or quantitative) to be collected, the method of data collection also varies .

The most common means for collecting quantitative data is the structured interview .

Studies that obtain data by interviewing respondents are called surveys. Data can also be collected by using self-administered questionnaires . Telephone interviewing is another way in which data may be collected .

Other means of data collection include secondary sources, such as the census, vital registration records, official documents, previous surveys, etc.

Qualitative data are collected mainly through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions , Key Informant Interview ( KII), and observational studies.

Process and Analyze the Collected Research Data

Data processing generally begins with the editing and coding of data . Data are edited to ensure consistency across respondents and to locate omissions if any.

In survey data, editing reduces errors in the recording, improves legibility, and clarifies unclear and inappropriate responses. In addition to editing, the data also need coding.

Because it is impractical to place raw data into a report, alphanumeric codes are used to reduce the responses to a more manageable form for storage and future processing.

This coding process facilitates the processing of the data. The personal computer offers an excellent opportunity for data editing and coding processes.

Data analysis usually involves reducing accumulated data to a manageable size, developing summaries, searching for patterns, and applying statistical techniques for understanding and interpreting the findings in light of the research questions.

Further, based on his analysis, the researcher determines if his findings are consistent with the formulated hypotheses and theories.

The techniques used in analyzing data may range from simple graphical techniques to very complex multivariate analyses depending on the study’s objectives, the research design employed, and the nature of the data collected.

As in the case of data collection methods, an analytical technique appropriate in one situation may not be suitable for another.

Writing Research Report – Developing Research Proposal, Writing Report, Disseminating and Utilizing Results

The entire task of a research study is accumulated in a document called a proposal or research proposal.

A research proposal is a work plan, prospectus, outline, offer, and a statement of intent or commitment from an individual researcher or an organization to produce a product or render a service to a potential client or sponsor .

The proposal will be prepared to keep the sequence presented in the research process. The proposal tells us what, how, where, and to whom it will be done.

It must also show the benefit of doing it. It always includes an explanation of the purpose of the study (the research objectives) or a definition of the problem.

It systematically outlines the particular research methodology and details the procedures utilized at each stage of the research process.

The end goal of a scientific study is to interpret the results and draw conclusions.

To this end, it is necessary to prepare a report and transmit the findings and recommendations to administrators, policymakers, and program managers to make a decision.

There are various research reports: term papers, dissertations, journal articles , papers for presentation at professional conferences and seminars, books, thesis, and so on. The results of a research investigation prepared in any form are of little utility if they are not communicated to others.

The primary purpose of a dissemination strategy is to identify the most effective media channels to reach different audience groups with study findings most relevant to their needs.

The dissemination may be made through a conference, a seminar, a report, or an oral or poster presentation.

The style and organization of the report will differ according to the target audience, the occasion, and the purpose of the research. Reports should be developed from the client’s perspective.

A report is an excellent means that helps to establish the researcher’s credibility. At a bare minimum, a research report should contain sections on:

- An executive summary;

- Background of the problem;

- Literature review;

- Methodology;

- Discussion;

- Conclusions and

- Recommendations.

The study results can also be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals published by academic institutions and reputed publishers both at home and abroad. The report should be properly evaluated .

These journals have their format and editorial policies. The contributors can submit their manuscripts adhering to the policies and format for possible publication of their papers.

There are now ample opportunities for researchers to publish their work online.

The researchers have conducted many interesting studies without affecting actual settings. Ideally, the concluding step of a scientific study is to plan for its utilization in the real world.

Although researchers are often not in a position to implement a plan for utilizing research findings, they can contribute by including in their research reports a few recommendations regarding how the study results could be utilized for policy formulation and program intervention.

Why is the dissemination of research findings important?

Dissemination of research findings is crucial because the results of a research investigation have little utility if not communicated to others. Dissemination ensures that the findings reach relevant stakeholders, policymakers, and program managers to inform decisions.

How should a research report be structured?

A research report should contain sections on an executive summary, background of the problem, literature review, methodology, findings, discussion, conclusions, and recommendations.

Why is it essential to consider the target audience when preparing a research report?

The style and organization of a research report should differ based on the target audience, occasion, and research purpose. Tailoring the report to the audience ensures that the findings are communicated effectively and are relevant to their needs.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research Process Steps: What they are + How To Follow

There are various approaches to conducting basic and applied research. This article explains the research process steps you should know. Whether you are doing basic research or applied research, there are many ways of doing it. In some ways, each research study is unique since it is conducted at a different time and place.

Conducting research might be difficult, but there are clear processes to follow. The research process starts with a broad idea for a topic. This article will assist you through the research process steps, helping you focus and develop your topic.

Research Process Steps

The research process consists of a series of systematic procedures that a researcher must go through in order to generate knowledge that will be considered valuable by the project and focus on the relevant topic.

To conduct effective research, you must understand the research process steps and follow them. Here are a few steps in the research process to make it easier for you:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

Finding an issue or formulating a research question is the first step. A well-defined research problem will guide the researcher through all stages of the research process, from setting objectives to choosing a technique. There are a number of approaches to get insight into a topic and gain a better understanding of it. Such as:

- A preliminary survey

- Case studies

- Interviews with a small group of people

- Observational survey

Step 2: Evaluate the Literature

A thorough examination of the relevant studies is essential to the research process . It enables the researcher to identify the precise aspects of the problem. Once a problem has been found, the investigator or researcher needs to find out more about it.

This stage gives problem-zone background. It teaches the investigator about previous research, how they were conducted, and its conclusions. The researcher can build consistency between his work and others through a literature review. Such a review exposes the researcher to a more significant body of knowledge and helps him follow the research process efficiently.

Step 3: Create Hypotheses

Formulating an original hypothesis is the next logical step after narrowing down the research topic and defining it. A belief solves logical relationships between variables. In order to establish a hypothesis, a researcher must have a certain amount of expertise in the field.

It is important for researchers to keep in mind while formulating a hypothesis that it must be based on the research topic. Researchers are able to concentrate their efforts and stay committed to their objectives when they develop theories to guide their work.

Step 4: The Research Design

Research design is the plan for achieving objectives and answering research questions. It outlines how to get the relevant information. Its goal is to design research to test hypotheses, address the research questions, and provide decision-making insights.

The research design aims to minimize the time, money, and effort required to acquire meaningful evidence. This plan fits into four categories:

- Exploration and Surveys

- Data Analysis

- Observation

Step 5: Describe Population

Research projects usually look at a specific group of people, facilities, or how technology is used in the business. In research, the term population refers to this study group. The research topic and purpose help determine the study group.

Suppose a researcher wishes to investigate a certain group of people in the community. In that case, the research could target a specific age group, males or females, a geographic location, or an ethnic group. A final step in a study’s design is to specify its sample or population so that the results may be generalized.

Step 6: Data Collection

Data collection is important in obtaining the knowledge or information required to answer the research issue. Every research collected data, either from the literature or the people being studied. Data must be collected from the two categories of researchers. These sources may provide primary data.

- Questionnaire

Secondary data categories are:

- Literature survey

- Official, unofficial reports

- An approach based on library resources

Step 7: Data Analysis

During research design, the researcher plans data analysis. After collecting data, the researcher analyzes it. The data is examined based on the approach in this step. The research findings are reviewed and reported.

Data analysis involves a number of closely related stages, such as setting up categories, applying these categories to raw data through coding and tabulation, and then drawing statistical conclusions. The researcher can examine the acquired data using a variety of statistical methods.

Step 8: The Report-writing

After completing these steps, the researcher must prepare a report detailing his findings. The report must be carefully composed with the following in mind:

- The Layout: On the first page, the title, date, acknowledgments, and preface should be on the report. A table of contents should be followed by a list of tables, graphs, and charts if any.

- Introduction: It should state the research’s purpose and methods. This section should include the study’s scope and limits.

- Summary of Findings: A non-technical summary of findings and recommendations will follow the introduction. The findings should be summarized if they’re lengthy.

- Principal Report: The main body of the report should make sense and be broken up into sections that are easy to understand.

- Conclusion: The researcher should restate his findings at the end of the main text. It’s the final result.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

The research process involves several steps that make it easy to complete the research successfully. The steps in the research process described above depend on each other, and the order must be kept. So, if we want to do a research project, we should follow the research process steps.

QuestionPro’s enterprise-grade research platform can collect survey and qualitative observation data. The tool’s nature allows for data processing and essential decisions. The platform lets you store and process data. Start immediately!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Customer Communication Tool: Types, Methods, Uses, & Tools

Apr 23, 2024

Top 12 Sentiment Analysis Tools for Understanding Emotions

QuestionPro BI: From Research Data to Actionable Dashboards

Apr 22, 2024

21 Best Customer Experience Management Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 The research process

In Chapter 1, we saw that scientific research is the process of acquiring scientific knowledge using the scientific method. But how is such research conducted? This chapter delves into the process of scientific research, and the assumptions and outcomes of the research process.

Paradigms of social research

Our design and conduct of research is shaped by our mental models, or frames of reference that we use to organise our reasoning and observations. These mental models or frames (belief systems) are called paradigms . The word ‘paradigm’ was popularised by Thomas Kuhn (1962) [1] in his book The structure of scientific r evolutions , where he examined the history of the natural sciences to identify patterns of activities that shape the progress of science. Similar ideas are applicable to social sciences as well, where a social reality can be viewed by different people in different ways, which may constrain their thinking and reasoning about the observed phenomenon. For instance, conservatives and liberals tend to have very different perceptions of the role of government in people’s lives, and hence, have different opinions on how to solve social problems. Conservatives may believe that lowering taxes is the best way to stimulate a stagnant economy because it increases people’s disposable income and spending, which in turn expands business output and employment. In contrast, liberals may believe that governments should invest more directly in job creation programs such as public works and infrastructure projects, which will increase employment and people’s ability to consume and drive the economy. Likewise, Western societies place greater emphasis on individual rights, such as one’s right to privacy, right of free speech, and right to bear arms. In contrast, Asian societies tend to balance the rights of individuals against the rights of families, organisations, and the government, and therefore tend to be more communal and less individualistic in their policies. Such differences in perspective often lead Westerners to criticise Asian governments for being autocratic, while Asians criticise Western societies for being greedy, having high crime rates, and creating a ‘cult of the individual’. Our personal paradigms are like ‘coloured glasses’ that govern how we view the world and how we structure our thoughts about what we see in the world.

Paradigms are often hard to recognise, because they are implicit, assumed, and taken for granted. However, recognising these paradigms is key to making sense of and reconciling differences in people’s perceptions of the same social phenomenon. For instance, why do liberals believe that the best way to improve secondary education is to hire more teachers, while conservatives believe that privatising education (using such means as school vouchers) is more effective in achieving the same goal? Conservatives place more faith in competitive markets (i.e., in free competition between schools competing for education dollars), while liberals believe more in labour (i.e., in having more teachers and schools). Likewise, in social science research, to understand why a certain technology was successfully implemented in one organisation, but failed miserably in another, a researcher looking at the world through a ‘rational lens’ will look for rational explanations of the problem, such as inadequate technology or poor fit between technology and the task context where it is being utilised. Another researcher looking at the same problem through a ‘social lens’ may seek out social deficiencies such as inadequate user training or lack of management support. Those seeing it through a ‘political lens’ will look for instances of organisational politics that may subvert the technology implementation process. Hence, subconscious paradigms often constrain the concepts that researchers attempt to measure, their observations, and their subsequent interpretations of a phenomenon. However, given the complex nature of social phenomena, it is possible that all of the above paradigms are partially correct, and that a fuller understanding of the problem may require an understanding and application of multiple paradigms.

Two popular paradigms today among social science researchers are positivism and post-positivism. Positivism , based on the works of French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857), was the dominant scientific paradigm until the mid-twentieth century. It holds that science or knowledge creation should be restricted to what can be observed and measured. Positivism tends to rely exclusively on theories that can be directly tested. Though positivism was originally an attempt to separate scientific inquiry from religion (where the precepts could not be objectively observed), positivism led to empiricism or a blind faith in observed data and a rejection of any attempt to extend or reason beyond observable facts. Since human thoughts and emotions could not be directly measured, they were not considered to be legitimate topics for scientific research. Frustrations with the strictly empirical nature of positivist philosophy led to the development of post-positivism (or postmodernism) during the mid-late twentieth century. Post-positivism argues that one can make reasonable inferences about a phenomenon by combining empirical observations with logical reasoning. Post-positivists view science as not certain but probabilistic (i.e., based on many contingencies), and often seek to explore these contingencies to understand social reality better. The post-positivist camp has further fragmented into subjectivists , who view the world as a subjective construction of our subjective minds rather than as an objective reality, and critical realists , who believe that there is an external reality that is independent of a person’s thinking but we can never know such reality with any degree of certainty.

Burrell and Morgan (1979), [2] in their seminal book Sociological p aradigms and organizational a nalysis , suggested that the way social science researchers view and study social phenomena is shaped by two fundamental sets of philosophical assumptions: ontology and epistemology. Ontology refers to our assumptions about how we see the world (e.g., does the world consist mostly of social order or constant change?). Epistemology refers to our assumptions about the best way to study the world (e.g., should we use an objective or subjective approach to study social reality?). Using these two sets of assumptions, we can categorise social science research as belonging to one of four categories (see Figure 3.1).

If researchers view the world as consisting mostly of social order (ontology) and hence seek to study patterns of ordered events or behaviours, and believe that the best way to study such a world is using an objective approach (epistemology) that is independent of the person conducting the observation or interpretation, such as by using standardised data collection tools like surveys, then they are adopting a paradigm of functionalism . However, if they believe that the best way to study social order is though the subjective interpretation of participants, such as by interviewing different participants and reconciling differences among their responses using their own subjective perspectives, then they are employing an interpretivism paradigm. If researchers believe that the world consists of radical change and seek to understand or enact change using an objectivist approach, then they are employing a radical structuralism paradigm. If they wish to understand social change using the subjective perspectives of the participants involved, then they are following a radical humanism paradigm.

To date, the majority of social science research has emulated the natural sciences, and followed the functionalist paradigm. Functionalists believe that social order or patterns can be understood in terms of their functional components, and therefore attempt to break down a problem into small components and studying one or more components in detail using objectivist techniques such as surveys and experimental research. However, with the emergence of post-positivist thinking, a small but growing number of social science researchers are attempting to understand social order using subjectivist techniques such as interviews and ethnographic studies. Radical humanism and radical structuralism continues to represent a negligible proportion of social science research, because scientists are primarily concerned with understanding generalisable patterns of behaviour, events, or phenomena, rather than idiosyncratic or changing events. Nevertheless, if you wish to study social change, such as why democratic movements are increasingly emerging in Middle Eastern countries, or why this movement was successful in Tunisia, took a longer path to success in Libya, and is still not successful in Syria, then perhaps radical humanism is the right approach for such a study. Social and organisational phenomena generally consist of elements of both order and change. For instance, organisational success depends on formalised business processes, work procedures, and job responsibilities, while being simultaneously constrained by a constantly changing mix of competitors, competing products, suppliers, and customer base in the business environment. Hence, a holistic and more complete understanding of social phenomena such as why some organisations are more successful than others, requires an appreciation and application of a multi-paradigmatic approach to research.

Overview of the research process

So how do our mental paradigms shape social science research? At its core, all scientific research is an iterative process of observation, rationalisation, and validation. In the observation phase, we observe a natural or social phenomenon, event, or behaviour that interests us. In the rationalisation phase, we try to make sense of the observed phenomenon, event, or behaviour by logically connecting the different pieces of the puzzle that we observe, which in some cases, may lead to the construction of a theory. Finally, in the validation phase, we test our theories using a scientific method through a process of data collection and analysis, and in doing so, possibly modify or extend our initial theory. However, research designs vary based on whether the researcher starts at observation and attempts to rationalise the observations (inductive research), or whether the researcher starts at an ex ante rationalisation or a theory and attempts to validate the theory (deductive research). Hence, the observation-rationalisation-validation cycle is very similar to the induction-deduction cycle of research discussed in Chapter 1.

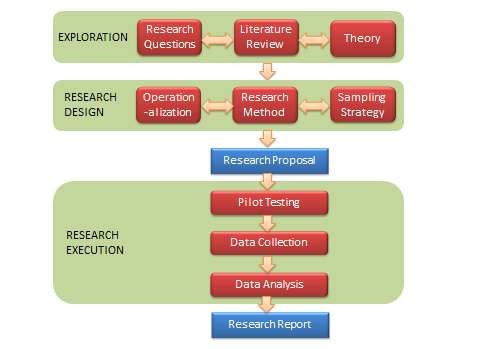

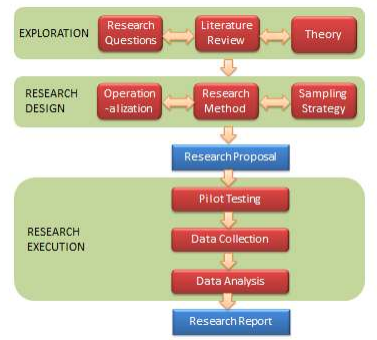

Most traditional research tends to be deductive and functionalistic in nature. Figure 3.2 provides a schematic view of such a research project. This figure depicts a series of activities to be performed in functionalist research, categorised into three phases: exploration, research design, and research execution. Note that this generalised design is not a roadmap or flowchart for all research. It applies only to functionalistic research, and it can and should be modified to fit the needs of a specific project.

The first phase of research is exploration . This phase includes exploring and selecting research questions for further investigation, examining the published literature in the area of inquiry to understand the current state of knowledge in that area, and identifying theories that may help answer the research questions of interest.

The first step in the exploration phase is identifying one or more research questions dealing with a specific behaviour, event, or phenomena of interest. Research questions are specific questions about a behaviour, event, or phenomena of interest that you wish to seek answers for in your research. Examples include determining which factors motivate consumers to purchase goods and services online without knowing the vendors of these goods or services, how can we make high school students more creative, and why some people commit terrorist acts. Research questions can delve into issues of what, why, how, when, and so forth. More interesting research questions are those that appeal to a broader population (e.g., ‘how can firms innovate?’ is a more interesting research question than ‘how can Chinese firms innovate in the service-sector?’), address real and complex problems (in contrast to hypothetical or ‘toy’ problems), and where the answers are not obvious. Narrowly focused research questions (often with a binary yes/no answer) tend to be less useful and less interesting and less suited to capturing the subtle nuances of social phenomena. Uninteresting research questions generally lead to uninteresting and unpublishable research findings.

The next step is to conduct a literature review of the domain of interest. The purpose of a literature review is three-fold: one, to survey the current state of knowledge in the area of inquiry, two, to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and three, to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area. Literature review is commonly done today using computerised keyword searches in online databases. Keywords can be combined using Boolean operators such as ‘and’ and ‘or’ to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a shortlist of relevant articles is generated from the keyword search, the researcher must then manually browse through each article, or at least its abstract, to determine the suitability of that article for a detailed review. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology. Reviewed articles may be summarised in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organising frameworks such as a concept matrix. A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature (which would obviate the need to study them again), whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of the findings of the literature review. The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions.

Since functionalist (deductive) research involves theory-testing, the third step is to identify one or more theories can help address the desired research questions. While the literature review may uncover a wide range of concepts or constructs potentially related to the phenomenon of interest, a theory will help identify which of these constructs is logically relevant to the target phenomenon and how. Forgoing theories may result in measuring a wide range of less relevant, marginally relevant, or irrelevant constructs, while also minimising the chances of obtaining results that are meaningful and not by pure chance. In functionalist research, theories can be used as the logical basis for postulating hypotheses for empirical testing. Obviously, not all theories are well-suited for studying all social phenomena. Theories must be carefully selected based on their fit with the target problem and the extent to which their assumptions are consistent with that of the target problem. We will examine theories and the process of theorising in detail in the next chapter.

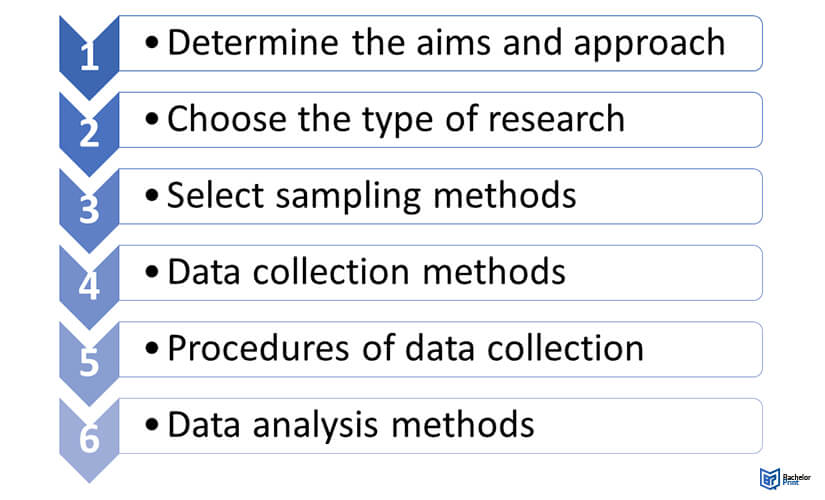

The next phase in the research process is research design . This process is concerned with creating a blueprint of the actions to take in order to satisfactorily answer the research questions identified in the exploration phase. This includes selecting a research method, operationalising constructs of interest, and devising an appropriate sampling strategy.

Operationalisation is the process of designing precise measures for abstract theoretical constructs. This is a major problem in social science research, given that many of the constructs, such as prejudice, alienation, and liberalism are hard to define, let alone measure accurately. Operationalisation starts with specifying an ‘operational definition’ (or ‘conceptualization’) of the constructs of interest. Next, the researcher can search the literature to see if there are existing pre-validated measures matching their operational definition that can be used directly or modified to measure their constructs of interest. If such measures are not available or if existing measures are poor or reflect a different conceptualisation than that intended by the researcher, new instruments may have to be designed for measuring those constructs. This means specifying exactly how exactly the desired construct will be measured (e.g., how many items, what items, and so forth). This can easily be a long and laborious process, with multiple rounds of pre-tests and modifications before the newly designed instrument can be accepted as ‘scientifically valid’. We will discuss operationalisation of constructs in a future chapter on measurement.

Simultaneously with operationalisation, the researcher must also decide what research method they wish to employ for collecting data to address their research questions of interest. Such methods may include quantitative methods such as experiments or survey research or qualitative methods such as case research or action research, or possibly a combination of both. If an experiment is desired, then what is the experimental design? If this is a survey, do you plan a mail survey, telephone survey, web survey, or a combination? For complex, uncertain, and multifaceted social phenomena, multi-method approaches may be more suitable, which may help leverage the unique strengths of each research method and generate insights that may not be obtained using a single method.

Researchers must also carefully choose the target population from which they wish to collect data, and a sampling strategy to select a sample from that population. For instance, should they survey individuals or firms or workgroups within firms? What types of individuals or firms do they wish to target? Sampling strategy is closely related to the unit of analysis in a research problem. While selecting a sample, reasonable care should be taken to avoid a biased sample (e.g., sample based on convenience) that may generate biased observations. Sampling is covered in depth in a later chapter.

At this stage, it is often a good idea to write a research proposal detailing all of the decisions made in the preceding stages of the research process and the rationale behind each decision. This multi-part proposal should address what research questions you wish to study and why, the prior state of knowledge in this area, theories you wish to employ along with hypotheses to be tested, how you intend to measure constructs, what research method is to be employed and why, and desired sampling strategy. Funding agencies typically require such a proposal in order to select the best proposals for funding. Even if funding is not sought for a research project, a proposal may serve as a useful vehicle for seeking feedback from other researchers and identifying potential problems with the research project (e.g., whether some important constructs were missing from the study) before starting data collection. This initial feedback is invaluable because it is often too late to correct critical problems after data is collected in a research study.

Having decided who to study (subjects), what to measure (concepts), and how to collect data (research method), the researcher is now ready to proceed to the research execution phase. This includes pilot testing the measurement instruments, data collection, and data analysis.

Pilot testing is an often overlooked but extremely important part of the research process. It helps detect potential problems in your research design and/or instrumentation (e.g., whether the questions asked are intelligible to the targeted sample), and to ensure that the measurement instruments used in the study are reliable and valid measures of the constructs of interest. The pilot sample is usually a small subset of the target population. After successful pilot testing, the researcher may then proceed with data collection using the sampled population. The data collected may be quantitative or qualitative, depending on the research method employed.

Following data collection, the data is analysed and interpreted for the purpose of drawing conclusions regarding the research questions of interest. Depending on the type of data collected (quantitative or qualitative), data analysis may be quantitative (e.g., employ statistical techniques such as regression or structural equation modelling) or qualitative (e.g., coding or content analysis).

The final phase of research involves preparing the final research report documenting the entire research process and its findings in the form of a research paper, dissertation, or monograph. This report should outline in detail all the choices made during the research process (e.g., theory used, constructs selected, measures used, research methods, sampling, etc.) and why, as well as the outcomes of each phase of the research process. The research process must be described in sufficient detail so as to allow other researchers to replicate your study, test the findings, or assess whether the inferences derived are scientifically acceptable. Of course, having a ready research proposal will greatly simplify and quicken the process of writing the finished report. Note that research is of no value unless the research process and outcomes are documented for future generations—such documentation is essential for the incremental progress of science.

Common mistakes in research

The research process is fraught with problems and pitfalls, and novice researchers often find, after investing substantial amounts of time and effort into a research project, that their research questions were not sufficiently answered, or that the findings were not interesting enough, or that the research was not of ‘acceptable’ scientific quality. Such problems typically result in research papers being rejected by journals. Some of the more frequent mistakes are described below.

Insufficiently motivated research questions. Often times, we choose our ‘pet’ problems that are interesting to us but not to the scientific community at large, i.e., it does not generate new knowledge or insight about the phenomenon being investigated. Because the research process involves a significant investment of time and effort on the researcher’s part, the researcher must be certain—and be able to convince others—that the research questions they seek to answer deal with real—and not hypothetical—problems that affect a substantial portion of a population and have not been adequately addressed in prior research.

Pursuing research fads. Another common mistake is pursuing ‘popular’ topics with limited shelf life. A typical example is studying technologies or practices that are popular today. Because research takes several years to complete and publish, it is possible that popular interest in these fads may die down by the time the research is completed and submitted for publication. A better strategy may be to study ‘timeless’ topics that have always persisted through the years.

Unresearchable problems. Some research problems may not be answered adequately based on observed evidence alone, or using currently accepted methods and procedures. Such problems are best avoided. However, some unresearchable, ambiguously defined problems may be modified or fine tuned into well-defined and useful researchable problems.

Favoured research methods. Many researchers have a tendency to recast a research problem so that it is amenable to their favourite research method (e.g., survey research). This is an unfortunate trend. Research methods should be chosen to best fit a research problem, and not the other way around.

Blind data mining. Some researchers have the tendency to collect data first (using instruments that are already available), and then figure out what to do with it. Note that data collection is only one step in a long and elaborate process of planning, designing, and executing research. In fact, a series of other activities are needed in a research process prior to data collection. If researchers jump into data collection without such elaborate planning, the data collected will likely be irrelevant, imperfect, or useless, and their data collection efforts may be entirely wasted. An abundance of data cannot make up for deficits in research planning and design, and particularly, for the lack of interesting research questions.

- Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Burrell, G. & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis: elements of the sociology of corporate life . London: Heinemann Educational. ↵

Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices (Revised edition) Copyright © 2019 by Anol Bhattacherjee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Table of Contents

Research Process

Definition:

Research Process is a systematic and structured approach that involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or information to answer a specific research question or solve a particular problem.

Research Process Steps

Research Process Steps are as follows:

Identify the Research Question or Problem

This is the first step in the research process. It involves identifying a problem or question that needs to be addressed. The research question should be specific, relevant, and focused on a particular area of interest.

Conduct a Literature Review

Once the research question has been identified, the next step is to conduct a literature review. This involves reviewing existing research and literature on the topic to identify any gaps in knowledge or areas where further research is needed. A literature review helps to provide a theoretical framework for the research and also ensures that the research is not duplicating previous work.

Formulate a Hypothesis or Research Objectives

Based on the research question and literature review, the researcher can formulate a hypothesis or research objectives. A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested to determine its validity, while research objectives are specific goals that the researcher aims to achieve through the research.

Design a Research Plan and Methodology

This step involves designing a research plan and methodology that will enable the researcher to collect and analyze data to test the hypothesis or achieve the research objectives. The research plan should include details on the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used.

Collect and Analyze Data

This step involves collecting and analyzing data according to the research plan and methodology. Data can be collected through various methods, including surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The data analysis process involves cleaning and organizing the data, applying statistical and analytical techniques to the data, and interpreting the results.

Interpret the Findings and Draw Conclusions

After analyzing the data, the researcher must interpret the findings and draw conclusions. This involves assessing the validity and reliability of the results and determining whether the hypothesis was supported or not. The researcher must also consider any limitations of the research and discuss the implications of the findings.

Communicate the Results

Finally, the researcher must communicate the results of the research through a research report, presentation, or publication. The research report should provide a detailed account of the research process, including the research question, literature review, research methodology, data analysis, findings, and conclusions. The report should also include recommendations for further research in the area.

Review and Revise

The research process is an iterative one, and it is important to review and revise the research plan and methodology as necessary. Researchers should assess the quality of their data and methods, reflect on their findings, and consider areas for improvement.

Ethical Considerations

Throughout the research process, ethical considerations must be taken into account. This includes ensuring that the research design protects the welfare of research participants, obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality and privacy, and avoiding any potential harm to participants or their communities.

Dissemination and Application

The final step in the research process is to disseminate the findings and apply the research to real-world settings. Researchers can share their findings through academic publications, presentations at conferences, or media coverage. The research can be used to inform policy decisions, develop interventions, or improve practice in the relevant field.

Research Process Example

Following is a Research Process Example:

Research Question : What are the effects of a plant-based diet on athletic performance in high school athletes?

Step 1: Background Research Conduct a literature review to gain a better understanding of the existing research on the topic. Read academic articles and research studies related to plant-based diets, athletic performance, and high school athletes.

Step 2: Develop a Hypothesis Based on the literature review, develop a hypothesis that a plant-based diet positively affects athletic performance in high school athletes.

Step 3: Design the Study Design a study to test the hypothesis. Decide on the study population, sample size, and research methods. For this study, you could use a survey to collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance from a sample of high school athletes who follow a plant-based diet and a sample of high school athletes who do not follow a plant-based diet.

Step 4: Collect Data Distribute the survey to the selected sample and collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance.

Step 5: Analyze Data Use statistical analysis to compare the data from the two samples and determine if there is a significant difference in athletic performance between those who follow a plant-based diet and those who do not.

Step 6 : Interpret Results Interpret the results of the analysis in the context of the research question and hypothesis. Discuss any limitations or potential biases in the study design.

Step 7: Draw Conclusions Based on the results, draw conclusions about whether a plant-based diet has a significant effect on athletic performance in high school athletes. If the hypothesis is supported by the data, discuss potential implications and future research directions.

Step 8: Communicate Findings Communicate the findings of the study in a clear and concise manner. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that the findings are understood and valued.

Applications of Research Process

The research process has numerous applications across a wide range of fields and industries. Some examples of applications of the research process include:

- Scientific research: The research process is widely used in scientific research to investigate phenomena in the natural world and develop new theories or technologies. This includes fields such as biology, chemistry, physics, and environmental science.

- Social sciences : The research process is commonly used in social sciences to study human behavior, social structures, and institutions. This includes fields such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, and economics.

- Education: The research process is used in education to study learning processes, curriculum design, and teaching methodologies. This includes research on student achievement, teacher effectiveness, and educational policy.

- Healthcare: The research process is used in healthcare to investigate medical conditions, develop new treatments, and evaluate healthcare interventions. This includes fields such as medicine, nursing, and public health.

- Business and industry : The research process is used in business and industry to study consumer behavior, market trends, and develop new products or services. This includes market research, product development, and customer satisfaction research.

- Government and policy : The research process is used in government and policy to evaluate the effectiveness of policies and programs, and to inform policy decisions. This includes research on social welfare, crime prevention, and environmental policy.

Purpose of Research Process

The purpose of the research process is to systematically and scientifically investigate a problem or question in order to generate new knowledge or solve a problem. The research process enables researchers to:

- Identify gaps in existing knowledge: By conducting a thorough literature review, researchers can identify gaps in existing knowledge and develop research questions that address these gaps.

- Collect and analyze data : The research process provides a structured approach to collecting and analyzing data. Researchers can use a variety of research methods, including surveys, experiments, and interviews, to collect data that is valid and reliable.

- Test hypotheses : The research process allows researchers to test hypotheses and make evidence-based conclusions. Through the systematic analysis of data, researchers can draw conclusions about the relationships between variables and develop new theories or models.

- Solve problems: The research process can be used to solve practical problems and improve real-world outcomes. For example, researchers can develop interventions to address health or social problems, evaluate the effectiveness of policies or programs, and improve organizational processes.

- Generate new knowledge : The research process is a key way to generate new knowledge and advance understanding in a given field. By conducting rigorous and well-designed research, researchers can make significant contributions to their field and help to shape future research.

Tips for Research Process

Here are some tips for the research process:

- Start with a clear research question : A well-defined research question is the foundation of a successful research project. It should be specific, relevant, and achievable within the given time frame and resources.

- Conduct a thorough literature review: A comprehensive literature review will help you to identify gaps in existing knowledge, build on previous research, and avoid duplication. It will also provide a theoretical framework for your research.

- Choose appropriate research methods: Select research methods that are appropriate for your research question, objectives, and sample size. Ensure that your methods are valid, reliable, and ethical.

- Be organized and systematic: Keep detailed notes throughout the research process, including your research plan, methodology, data collection, and analysis. This will help you to stay organized and ensure that you don’t miss any important details.

- Analyze data rigorously: Use appropriate statistical and analytical techniques to analyze your data. Ensure that your analysis is valid, reliable, and transparent.

- I nterpret results carefully : Interpret your results in the context of your research question and objectives. Consider any limitations or potential biases in your research design, and be cautious in drawing conclusions.

- Communicate effectively: Communicate your research findings clearly and effectively to your target audience. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that your findings are understood and valued.

- Collaborate and seek feedback : Collaborate with other researchers, experts, or stakeholders in your field. Seek feedback on your research design, methods, and findings to ensure that they are relevant, meaningful, and impactful.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Overview of research process.

The Research Process

Anything you write involves organization and a logical flow of ideas, so understanding the logic of the research process before beginning to write is essential. Simply put, you need to put your writing in the larger context—see the forest before you even attempt to see the trees.

In this brief introductory module, we’ll review the major steps in the research process, conceptualized here as a series of steps within a circle, with each step dependent on the previous one. The circle best depicts the recursive nature of the process; that is, once the process has been completed, the researcher may begin again by refining or expanding on the initial approach, or even pioneering a completely new approach to solving the problem.

Identify a Research Problem

You identify a research problem by first selecting a general topic that’s interesting to you and to the interests and specialties of your research advisor. Once identified, you’ll need to narrow it. For example, if teenage pregnancy is your general topic area, your specific topic could be a comparison of how teenage pregnancy affects young fathers and mothers differently.

Review the Literature

Find out what’s being asked or what’s already been done in the area by doing some exploratory reading. Discuss the topic with your advisor to gain additional insights, explore novel approaches, and begin to develop your research question, purpose statement, and hypothesis(es), if applicable.

Determine Research Question

A good research question is a question worth asking; one that poses a problem worth solving. A good question should:

- Be clear . It must be understandable to you and to others.

- Be researchable . It should be capable of developing into a manageable research design, so data may be collected in relation to it. Extremely abstract terms are unlikely to be suitable.

- Connect with established theory and research . There should be a literature on which you can draw to illuminate how your research question(s) should be approached.

- Be neither too broad nor too narrow. See Appendix A for a brief explanation of the narrowing process and how your research question, purpose statement, and hypothesis(es) are interconnected.

Appendix A Research Questions, Purpose Statement, Hypothesis(es)

Develop Research Methods

Once you’ve finalized your research question, purpose statement, and hypothesis(es), you’ll need to write your research proposal—a detailed management plan for your research project. The proposal is as essential to successful research as an architect’s plans are to the construction of a building.

See Appendix B to view the basic components of a research proposal.

Appendix B Components of a Research Proposal

Collect & Analyze Data

In Practical Research–Planning and Design (2005, 8th Edition), Leedy and Ormrod provide excellent advice for what the researcher does at this stage in the research process. The researcher now

- collects data that potentially relate to the problem,

- arranges the data into a logical organizational structure,

- analyzes and interprets the data to determine their meaning,

- determines if the data resolve the research problem or not, and

- determines if the data support the hypothesis or not.