Search form

The rise of k-pop, and what it reveals about society and culture.

Initially a musical subculture popular in South Korea during the 1990s, Korean Pop, or K-pop, has transformed into a global cultural phenomenon.

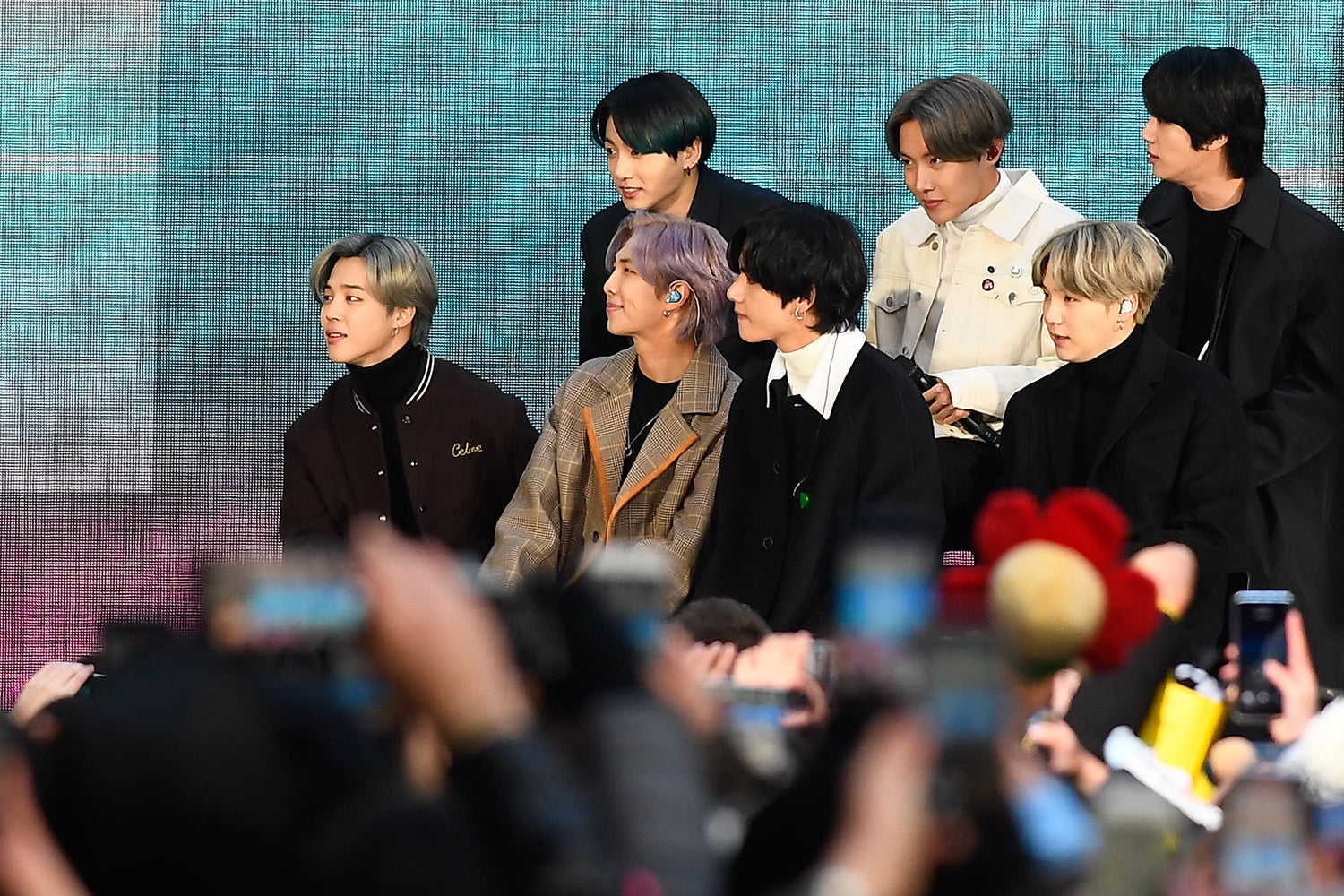

Characterized by catchy hooks, polished choreography, grandiose live performances, and impeccably produced music videos, K-pop — including music by groups like BTS and BLACKPINK — now frequently tops the Billboard charts, attracts a fiercely dedicated online following, and generates billions of dollars.

Yale sociologist Grace Kao, who became fascinated with the music after watching a 2019 performance by BTS on Saturday Night Live, now studies the subgenres of K-pop and its cultural, sociological, and political effects.

Kao, the IBM Professor of Sociology and professor of ethnicity, race, and migration in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and director of the Center on Empirical Research in Stratification and Inequality (CERSI), recently spoke with Yale News about the kinds of research her interest in K-pop has prompted, why the genre’s rise has been important to so many Asian Americans, and why she urges today’s students to become familiar with various musical genres.

The interview has been edited and condensed.

You have said that watching BTS on Saturday Night Live changed your view of K-pop. How did that performance transform your interest in K-pop from a personal one into an academic one?

Grace Kao: I saw that performance, and it stayed in the back of my mind. Then, when we were on lockdown because of COVID, being stuck at home set the stage for having time to watch more K-pop videos. At first, I was just watching them for fun. I knew K-pop was something important, but I didn’t know anything about it. I thought “I should educate myself on this.” My current research collaborator, Wonseok Lee [an ethnomusicologist and a musician at Washington University], and a Yale graduate student, Meera Choi, who’s Korean, offered guidance.

I’ve always been interested in race and ethnicity and Asian Americans. I knew in my gut that K-pop was important, but it was hard to figure out exactly how I could work on it, since I’m a quantitative sociologist. What's fun about being a researcher and being in academia is that we can learn new things and push ourselves. I think that’s the best part of this job.

Grace Kao recommends this playlist to get started.

When I started working on it, I tried to learn without having a clear research question. Then, along with my collaborator, Lee, we started thinking about papers that we could work on together. I was also able to take first-semester Korean, so now I can read Korean, and Choi and I can begin working on different research papers.

What kinds of research are you doing?

Kao: One paper is about the link between ’80s synth-pop and very current K-pop. Others have argued that K-pop borrows heavily from American Black music — R&B, hip hop, and so forth. And it’s true, but we’re arguing that K-pop has links to all these different genres because the production is much faster. We also finished another paper looking at the links between New Wave synth-pop to Japanese city pop [which was also popular in the 1980s] and a Korean version of city pop. And we’re probably going to start a reggae paper next.

In another project, with two data scientists we’re looking at Twitter data related to a 2021 BTS tweet that happened about a week after a gunman in Atlanta murdered eight women, including six of Asian descent. The tweet, which was about #StopAsianHate, or #StopAAPIHate, was the most retweeted tweet of the year. Everyone in that world knows that K-pop is extremely influential, but there are moments now where it seems like it’s ripe for political action because fans are already really organized. We’re looking at how the conversation about the shootings before and after they tweeted changed. The analysis involves millions of tweets, so it's very data intensive work.

Last March you gave a talk on campus in which you talked about the role of K-pop in “transformative possibilities for Asian Americans.” What is an example of those possibilities?

Kao: Partly it’s just visibility. The SNL performance by BTS was really important for people. Especially people my age, we had never seen a bunch of East Asian people on the stage singing in a non-English, non-Western language. I knew that was an important moment regardless of whether or not you like the music or the performance.

I think during COVID, BTS made Asian faces more visible. They were on the cover of Time magazine, every major publication. They were everywhere. But it also brought up questions of xenophobia. People were making fun of them because of how they looked. At the time there was also the extra baggage that comes with being Asian. But any time BTS were attacked, because their fandom is so big and so passionate, their fans would jump on anyone who did anything to them. Then journalists would cover it, and suddenly there were all these stories about how you shouldn’t be racist against Asians.

Many of us who study Asian Americans have observed over time that it often seems acceptable for people to make fun of Asian things. Just by virtue of the fact that it’s [BTS], that their fans are protecting them, and that that gets elevated to the news is a big deal. President Biden invited them to the White House. These are all things I would have had trouble imagining even just five years ago.

You teach a first-year seminar, “Race and Place in British New Wave, K-pop, and Beyond,” which focuses on the emphasis on aesthetics in both genres’ popularity. What understanding do you hope students walk away with?

Kao: I want students to take pop culture very seriously. Sometimes pop music seems not serious, but so many people consume it that it can have pervasive and serious consequences on how people see folks of different race, ethnic, gender, and national identities.

Another thing I wanted students to learn about is genres of music. Students today like music, but they consume it very differently than people did when in college. We listened to the radio or watched MTV, so we were fed something from a DJ or from actual people who were programming the content. You’d end up listening to a lot of music that you didn’t like, but you’d also have a better sense of genres than students now. Today students consume music through Spotify or YouTube and so forth, which use algorithms to give you songs that are similar to the songs you liked, but not necessarily from the same genre. Students can have diverse and wide-ranging experiences with music, but I found that they have trouble identifying that any particular song is part of a genre. So I feel like it’s important for them to listen to a lot of music.

I want them to consume it because sometimes we think we can comment on things that we don’t know anything about. We don’t actually consume it. I think it’s important for students to walk away knowing something about these genres and to be able to identify them: this is a reggae song, this is a ska song, this is synth-pop, et cetera.

What K-pop groups are you currently into?

Kao: Besides BTS, I enjoy listening to groups such as SEVENTEEN, ENHYPEN, NewJeans, Super Junior, and new group TRENDZ.

Arts & Humanities

International

Social Sciences

Media Contact

Bess Connolly : [email protected] ,

Meet Yale College graduates of the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy

For one mother and son, parallel paths led to Yale School of Nursing

Fighting for women’s inclusion in public policy

Four graduating SOM students receive Dean’s Mission & Impact Award

- Show More Articles

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

The Rise and Rise of K-Pop: A Pocket History

Department of Music, SOAS University of London

- Published: 14 July 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

K-pop, Korean popular music, is a central component in Korea’s cultural exports. It helps brand Korea, and through sponsorships and tie-ups, generates attention for Korea that goes well beyond the music and media industries. This essay traces the history of Korean popular music, from its emergence in the early decades of the twentieth century, through the influence of America on South Korea’s cultural development and the assimilation of genres such as rap, reggae, punk, and hip hop, to the international success of Psy’s ‘Gangnam Style’ and the idol group BTS. It explores the rise of entertainment companies, how they overcame the digital challenge, and how their use of restrictive contracts created today’s cultural economy. It introduces issues of gender and sexuality, and outlines how music videos and social media have been used to leverage fandom.

Introduction

In December 2018, the Korea Foundation reported there were 89.19 million fans of Korean popular culture, who together populated 1,843 clubs in 113 countries outside Korea. 1 The total had increased 22 percent since 2017, mostly because of the success of a single K-pop idol group, BTS. There was, though, much more behind the story, not least Psy’s ‘Gangnam Style,’ YouTube views of which by April 2020 had surpassed 3.6 billion. The rise of K-pop is a recent phenomenon: the first edition of World Music: The Rough Guide commented that although Korea had gone through a period of staggering economic development, in pop music there was “nothing to match the remarkable contemporary sounds of Indonesia, Okinawa or Japan” ( Kawakami and Fisher 1994 , 470). A year later, John Lent’s Asian Popular Culture (1995) omitted Korea entirely, and even in 2004, Chun, Rossiter, and Shoesmith’s Refashioning Pop Music in Asia included Korea solely in a discussion of a solitary Korean singer working in Japan. This essay attempts to offer an overview of K-pop’s remarkable recent history, although I admit at the outset that doing so is, because of K-pop’s amazing vitality, increasingly difficult to achieve. 2

Local and Regional: The Beginnings of Korean Pop

The story begins with the rise of the recording industry in the early twentieth century. Korea was a Japanese colony from 1910 to 1945, so early labels and studios were based across the East Sea in Japan, and Korea served, as Yamauchi puts it, as the “arena where the Japanese recording industry embarked on an imperialist undertaking” (2012, 146–147). By the late 1920s, six recording companies headquartered in Japan had Korean subsidiaries—Columbia, Victor, Polydor, Teichiku (allied to Okeh in Korea), Taihei (allied to T’aep’yŏng), and Chieron. Korean fixers negotiated relationships with Japanese companies, although, not least because Korean singers traveled to Japan to record, their activities and impact are debated (see, e.g., Pak 1992 ; Chang 2006 , 38–129; Yamauchi 2009 ; Choi 2015 ). By the 1930s, some Korean musicians and composers, such as Ri Myŏnsang (1909–1989)—who later became North Korea’s most celebrated composer—settled in Japan, where they worked for studios. Whether Korean popular songs were distinctive from Japanese equivalents has long been argued. The Japanese term ryūkōka (popular/trendy + song) was first used in Japan in 1914 in regard to ‘Katyusha’s Song,’ and one of the earliest equivalent Korean yuhaengga , 3 recorded in 1925, was ‘ Saŭi ch’anmi ’ (Adoration of Death), based on Ivanovich’s ‘Waves of the Danube’ and remembered primarily for the tragic suicide of its singer as she returned from Japan to Korea by boat after recording it. Ryūkōka were particularly associated with the Japanese composer Koga Masao (1904–1978), and Korean commentators argue he was influenced by Korean music because he grew up in the Korean port of Inch’ŏn to Seoul’s west. Japanese commentators would disagree, but it is hard to deny that Japanese evolutions, through to the still current enka (see Yano 2002 , 28–44), match, at least in terms of modes and the persistent foxtrot rhythm, today’s Korean t’ŭrŏt’ŭ . 4

A second popular song style emerged in the 1930s, shin minyo (new folksongs), which, although sharing a Japanese term for songs associated with companies and institutions, referred in Korea to composed songs given in a high tessitura that typically used traditionesque compound meters. These were often backed by the popular dance band, at times adding a few Korean instruments. The term shin minyo first appeared in a March 14, 1931, announcement in the Korea Daily News ( Chosŏn ilbo ) of two new songs by Hong Nanp’a (Hong Yonghu; 1897 or 1898–1941)—‘ Panga tchinnŭn saekshi norae ’ (Song of the Milling Girl) and ‘ Noksŭn karakchi ’ (Rusty Ring). The last song identified as a shin minyo was recorded in 1943 ( Yi 1997 , 372–388; Chang 2006 , 244–274).

At the end of World War II, Korea was divided in two. After 1200 years as a unified state, this had nothing to do with Koreans, but was designed to ensure the Allies maintained a foothold on the Asian mainland after Japan capitulated—the dividing line between the two parts was drawn up by desk officers in Washington. Many musicians settled in, what in 1948 became, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea), where ideology required all music to be popular. There, although it was claimed that all Japanese influence was abandoned as national identity was built, the yuhaengga style continued as yesul kayo (art songs). 5 Because censors checked lyrics, ensuring they unambiguously carried ideologically sound messages, songs dominated music production. Song arrangements became the basis of all instrumental and orchestral compositions, and with ‘ P’i pada ’ (Sea of Blood), premiered in 1971 as the first hyŏngmyŏng kagŭk (revolutionary opera), song operas 6 were normalized, abandoning recitatives and arias in favor of couplets ( chŏlga ) and off-stage choruses ( pangch’ang ) ( Howard 2020 , 101–175 and 222–230). Pop music arrived in 1983, in the form of an authorized band, Wangjaesan Light Music Band (Wangjaesan kyŏng ŭmaktan, the “light music” tag marking a continuation of yuhaengga ). The band took its name from a 1933 meeting of guerrillas presided over by Kim Il Sung. Pochonbo Electronic Ensemble (Poch’ŏnbo chŏngja aktan) launched two years later, named after the site of a 1937 battle led by Kim Il Sung. These have now given way to an updated pop style epitomized by Moranbong, an all-girl group which debuted on June 6, 2012 ( Howard 2020 , 242–267).

In contrast, the southern part of the peninsula was initially placed under American trusteeship. The remainder of this essay considers only South Korea, which became the Republic of Korea with the election of Syngman Rhee as president in 1948. The Korean War of 1950–1953 ensured that American popular forms, broadcast by the American Forces Network (AFN; in Korea, AFKN), would frame much domestic popular music ( Maliangkay 2006 ). Local musicians were hired to cover American chart songs wherever American GIs were stationed ( Shin et al. 1998a , 18–35), and to serve hotels and entertainment venues which catered for foreigners ( Maliangkay 2020 ). This helped create a new type of group, notable early examples of which were the Chŏgori [Jacket] Sisters, Arirang Brothers, and the Kim Sisters. These developed rich repertoires that mixed “Oriental” songs, American pop, and folksongs; the Kim Sisters became stars in the United States, appearing on the Dinah Shore, Dean Martin, and Hollywood Shows, and more. Hollywood films were screened in Korea, leading to a mid-1950s mambo craze and then introducing rock ’n’ roll and twist, although social conservatism coupled with strict censorship to ensure domestic airwaves avoided any American excesses.

Yuhaengga ’s supposed Japanese “color” led to a selective ban that began with Lee Mija’s ‘ Tongbaek Agassi ’ (White Flower Lady) in 1964 ( Pak 2006 ; Chang 2017 ), although the old genre remained standard fare in nightclubs and for partying ( Son 2006 ). Commercial radio stations launched in the 1960s (MBC in 1961, DBS in 1963, and TBS in 1964), and these encouraged domestic production. Ballads, replete with long intros and central instrumental interludes that facilitated announcer voice-overs, soon filled the airwaves. These showcased solo singers more than groups—because each broadcasting company employed its own in-house backing band, dance group, and arrangers. Local rock, often referred to as “group sound,” is often reported to have begun in 1964 with Shin Joong Hyun’s band, Add4 (see, e.g., Pil Ho Kim 2017 , 71; Dohee Kwon 2017 , 126), although others soon joined, such as Kim Hongt’ak’s Key Boys. 7 By the early 1970s, the authoritarian regime under general-turned-president Park Chung Hee had turned against such decadent music, restricting its broadcasts and moving it largely underground. Shin’s music was officially banned in 1975, shortly before Shin was arrested, ostensibly for smoking marijuana. 8 Ballads proved simpler to monitor and approve, and popular song contests organized by broadcasters in the 1970s and 1980s continued to introduce a steady stream of singers to the nation, among them the celebrated and enduring Cho Yong Pil and Lee Sun Hee. At the same time, the mid-1960s had seen the emergence of an underground “folk song” movement using acoustic guitars ( t’ong kit’a ), influenced by American protest songs and which, as part of a student song movement, was associated with demonstrations that demanded democracy ( Shin et al. 1998b , 18–51; Hwang 2006 , 37–39). 9

Learning from the Global: Assimilations and Appropriations

Popular music’s public conformism outlasted Park, who was assassinated in 1979. It basically continued until March 1992, when Seo Taiji burst onto Korean screens, introducing rap (Howard 2006a , b , 87–90; Maliangkay 2014 ). Four tracks from Seo’s first album entered the charts in rapid succession: ‘ Nan arayo ’ (I Know), ‘ Ijaenŭn ’ (Now), ‘ Hwansangsok ŭi kŭdae ’ (You in Your Dreams), and ‘ Ibami kip’ŏgajiman ’ (This Night, Is Deep, But). Intriguingly, Seo was not the first Korean to record rap. Studios had mixed rap tracks prior to 1992, but strict licensing requirements prevented any label releasing such supposedly degenerate music. Korea, however, after thirty years of military rule, had begun to embrace democracy, and in December1992 it was to elect its first non-military president, Kim Young Sam. State control was loosening. Korean Americans, knowledgeable about American pop genres, were returning to the homeland, keen to make a mark. A “new generation” ( shinsedae ) was maturing who had grown up without experience of colonialism, war, and poverty. Seo’s band, Seo Taiji and Boys, offered a new image of idols operating outside state or broadcaster control. It used conventional sampling techniques and synthesized accompaniments, but appropriated American genres. Soon, Seo turned to heavy metal and the Beastie Boys in a critique of school cramming, ‘ Kyoshil idea ’ (Classroom Ideology, 1994), and to gangsta rap in a commentary on drop-outs, ‘Come Back Home’ (1995; see Jung 2006 ). When Seo’s band disbanded, in January 1996, a survey for the journal Chugan Chosŏn ( Weekly Korea ) reported it was the favorite of five times as many Koreans as any other band. 10 Seo remained the top Korean icon in 1996’s end-of-year surveys. He blew experimentation open. Rock, R&B, and heavy metal had not been totally unknown, but, banned from the media, they were largely confined to underground clubs frequented by students in Seoul’s Shinch’on district (bordered by four universities: Yonsei, Ewha, Sogang, Hongik). Increasing affluence allowed new start-up labels to proliferate, pushing assimilations of American R&B and disco alongside ballads (Howard 2006a , b , 90–92; Fuhr 2016 , 52–55). After rap, reggae arrived with Kim Gun Mo’s ‘ P’inggye ’ (Excuse, 1993), a mix of rap and reggae came with Roo’ra’s Roots of Reggae (1994), and jungle was intimated in Pak Migyŏng’s ‘ Ibŭŭi kyŏnggo ’ (Eve’s Warning, 1995). Kim Gun Mo turned more explicitly to hip-hop; 11 punk took over Shinch’on’s clubs ( Epstein 2000 ). 12

After years of strict control by state bodies, lyrics remained non-controversial. Seo’s rap-based ‘I Know,’ for example, talked about leaving a lover, and realizing that a break-up in the relationship was inevitable. The singer regrets that he had never told her he loved her, and remembers her smile—all that he has left of her. ‘Excuse,’ similarly, matches reggae to sentiments about breaking up. The protagonist finds a letter with a single word, “Goodbye,” hidden inside a bouquet of flowers. His lover has left, without saying anything more, as if she wants to teach him about how love leads to sadness but does not want to consider his feelings.

While the explosion of popular culture can be considered to mirror the neoliberal commercialization of cultural production under Reagan and the first President Bush in the United States, 13 the buzz word in South Korea during the 1990s was “ segyehwa ”—globalization—suggesting that other factors were at play. South Korea was fast emerging as a major world economy, and its people wanted to be global citizens. Hence, the Seoul Olympics in 1988 had been run with the slogan “Seoul to the world, the world to Seoul.” Segyehwa in respect to Korean popular culture was facilitated by the expansion of satellite and cable broadcasting across Asia. Star TV was set up by Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka Shing in 1990, and MTV entered the Asian market in 1991. Star would later set up Channel V as a music-driven rival to MTV that targeted regional markets, including Korea, promoting local groups rather than Euro-American pop. Meanwhile, in Korea, Mnet started its cable operations in 1993. Every Korean home suddenly had unprecedented access to global trends.

With satellite and cable broadcasting, image, showcased by an Appadurian mediascape (after Appadurai 1996 ), became central. The focus shifted from aural to visual. ‘Excuse’ was marketed with one of the first-ever Korean music videos: filmed in Jamaica, it brought to prominence a dance duo, CLON (“there is no ‘e’ in ‘cloning,’” they explained to me in 1999), who had established themselves through Michael Jackson dance covers. Many music videos mirrored the then-popular OST albums of TV drama and film music, casting actors in scripted mini-dramas. Videos exploited the growing tolerance for graphic depictions of violence and sex, yet typically retained conservative lyrics. The 1998 video for H.O.T’s ( H igh Five o f T eenagers) ‘ Pit ’ (Hope) from their third album, for example, matched lyrics about love to scenes of road rage and the crushing to death of a teenage biker. Again, ‘Mother,’ the January 1999 debut of g.o.d ( G roove O ver d ose) coupled scenes of aggression and bullying among high school kids to lyrics that described growing up under the wings of a struggling single parent. 14 Imaging also encouraged dance to be highlighted, not least to serve live TV shows. Pop music had become the showcase for Korean Cool—the complex that soon become known as the Korean Wave ( Hallyu ) comprising music, drama and film, fashion, make-up, cuisine, and cosmetic surgery.

Won Rae, half of CLON, was somewhat musically challenged, so when the duo won a competition in 1996 that came with a contract to record three albums, they needed to supplement their dancing. The solution was to work with accomplished singers, hence, an established rock star, Kim Tae Young, joined for their 1999 album, Funky Together . CLON was one of the first groups to find success beyond Korea when their 1997 album was released in Taiwan through Rock Records ( Sung 2006 , 170–172). H.O.T., meanwhile, toured China—the term “Korean Wave” translates, via the Korean term Hallyu , the Chinese term hanliu , which was coined for these foreign forays. Note that until the turn of the millennium, Korean pop, with the exception of yuhaengga , was simply termed Han’guk kayo (Korean songs) or in’gi kayo (popular songs)—differentiating Korean productions from imported Euro-American p’apsong (pop songs) ( Shin 2013 , 29–39). As a term, then, K-pop emerged to mark the commodification of music within the Korean Wave. Its commodification, though, invites critiques akin to those of Adorno and the mid-twentieth-century Frankfurt School of popular culture, or critiques familiar from scholarship on neoliberalism. Hence, in summer 1999, when I interviewed Won Young Min, editor of the then-popular Korean magazine Global Music Video , he complained:

The main interest is in dance. There is no variety, and except for the drum machines that everybody uses, the techno of Europe is missing. Songs are mostly about love, and the lyricists don’t seem to care about topical issues (cited from Howard 2006a , b , 95).

The Local Solution: The Rise of Entertainment Companies

Commodification, in a neoliberal sense, was enabled through the rise of entertainment companies. SM Entertainment was the first to be set up, established by Lee Soo Man (a Seoul National University graduate, former participant in the underground song movement, and a radio and television host). 15 H.O.T. was SM’s first signing. Launched in September 1996, H.O.T. reputedly sold over ten million copies of its ten albums (five studio, four live, and one soundtrack album) before it disbanded in May 2001. To set up H.O.T., Lee first surveyed teenage girls, then advertised for dancers who fitted what girls told him they wanted. Applicants attended public auditions in both Seoul and Los Angeles in 2004, where looks as well as singing and dancing skills—and the decibels created by screaming audiences of teenage girls—were assessed. The five idols selected were then given systematic training before launching their debut album, We Hate All Kinds of Violence .

Where stars and bands had previously been found—auditioned or scouted in song competitions and festivals, either individually or as pre-existing groups—entertainment companies held competitions to identify recruits and then intensively trained, packaged, and launched idols and idol groups onto the market. The arrival of SM and it two major rivals, YG Entertainment and JYP Entertainment, 16 proved timely. H.O.T. debuted as mp3 players arrived and Koreans began to adapt to the digital era. Korea was by 1997 the thirteenth largest market for recorded music in the world, with domestic sales exceeding 54 million CDs and 155 million cassettes—and, for historical cost-per-unit reasons, these were sales of albums rather than singles. 17 But in 2000, although the Korean market was by then second largest in Asia, behind Japan, it only turned over an annual US$300 million. More than 20 percent of its value was lost year-on-year in each of the next four years. Entertainment companies had to leverage new revenue streams, and had to do so fast. They worked on product placement and sponsorship. They placed idols in film, TV drama, and comedy show cameos. They created ever-more flashy stage shows. They monetized fandom through merchandising. Over time, album sales became less important as they substituted business-to-business (B2B) for business-to-consumer (B2C) models ( Oh and Pak 2012 ). They built fan support through fanclubs, fanzines, and “fan passports,” and in recent years they have set up shrines to K-pop—as tourist destinations, complete with hologram idols, who passively greet fans ( Jung 2011 , 95–98; Kim 2018 , 125–126, 132–142).

The Asian financial crisis hit Korea in autumn 1997. 18 This reduced the attraction of Korea to international music conglomerates, leaving domestic entertainment companies to develop local strategies to weather the storm. Although the companies may “appear as small venture companies in the face of the global music industry” (Cha Ujin, interviewed in Kim 2018 , 34), they proved remarkably adept at manipulating the emerging Korean Wave. By 2013, the market capitalization of SM Entertainment had reached KRW780 billion (approx. US$697 million), YG KRW515 billion (US$460 million), and JYP KRW120 billion (US$107 million) ( Economist , October 26, 2013). 19 By September 2017, SM boasted 11.6 million YouTube channel subscribers, YG 3 million, and JYP 4.9 million. Individual idols and bands had more: BigBang, in the YG stable, had 7.9 million subscribers, while SM’s Super Junior had 5.8 million; on China’s Weibo, they had 9.2 million and 16 million followers, respectively ( Kim 2018 , 34–35). Such numbers, of course, pale in comparison with BTS, who at the time of writing (July 2020) boast 28.8 million YouTube subscribers. Today, many entertainment companies are active, including SM, YG, and JYP, but also Big Hit, Cube, FAVE, FNC, Star Empire, and Stone. 20

The financial crisis shredded the jobs-for-life culture that had long been associated with Korea’s manufacturing conglomerates and service industries. Those coming to the job market during and after the crisis are collectively known as the “880,000 wŏn ” generation—able to earn only US$800 a month, too little to support a family. Korea has few natural resources and a high population density, so must rely on its human resources. As a result, life in modern Korea centers around what a person can achieve. 21 So, as the job market contracted, young people competed to distinguish themselves, and in attempting to do so, K-pop’s idol culture proved attractive. To a generation pessimistic about ever earning a reasonable income, its high risk of failure was outweighed by the possibility of massive success ( Kang 2015 , 51–65). Hence the oft-cited remark attributed to BTS’s lead rapper, RM, who although he performed well at school decided to forego academic study, where he might become only the “5,000th-best mathematician in the country,” to be the “No. 1 rapper.”

Entertainment companies require those they recruit to sign contracts. These function as the political economy of Korea’s culture industry, generating value only when consumers and sponsors pay to see and hear a fully trained idol or idol group. Thus, contracts are designed to enable companies to recoup the costs of an extended training period before idols debut. 22 They must cover the costs of launching a debut album, subsequent ongoing costs, and, for a successful idol or group, every “comeback” album (that is, a second or later album). H.O.T. broke apart in 2001 because two members decided they were not paid enough and left— Time reported they were earning just US$10,000 for every million albums sold. 23 A number of court cases have determined that contracts are restrictive and do not comply with Korean (or international human rights) legislation. Reports link the suicides of a number of idols to the pressure cooker of training and life as an idol when bound to contracts. But, wannabe stars are apt to sign without understanding the terms: contracts typically ban trainees from drinking, smoking, using mobile phones, or having relationships; most require trainees to live together in a dormitory, and many include a condition giving the company the right to require trainees to undergo cosmetic surgery.

The company decides on the image of an idol or group. Trainees take on character roles and audition, almost as if they are actors, as the decision-making process plays out. The company matches trainees together, inserting or removing individuals from a prospective group. It is common for groups to have more members than appear at the debut, and the line-up may change during the public life of a group. The vast majority of trainees never make it to a debut. The company pressurizes trainees to conform; uniformity is required in dancing and singing, and group members will often be chosen who are of uniform height or body shape. Requiring cosmetic surgery to mold “golden ratio” faces is common; although initially associated with girl idols, boy idols are increasingly required to go under the scalpel. 24 Because the company decides on the market to target, special training in elocution and decorum or foreign languages may be required. Typically, an idol group will be assigned a leader, who relays instructions to the group and enforces compliance. The leader will often become the group’s spokesperson. Matching normative Korean social hierarchy, a group collectively looks up to its oldest member ( hyŏng ) and takes care of its youngest member ( mangnae ). In vlogs, music videos, and media appearances, roles can, however, border on caricature, so when the male idol group g.o.d. starred in a reality show for MBC TV in 2001, each took on a specific role, one as mother and one as father to a third, as a baby boy.

Training, launching, and oiling the promotion machine to keep a band going is, essentially, akin to industrial mass production. It builds in reproducibility and replaceability, involving the atomization of consumers as well as idols ( Strinati 2004 , 11) through the “McDonaldization” of labor ( Ritzer 2013 ). The process is set out and itemized in a manual distributed to SM Entertainment employees, detailing producer, composer, and choreographer roles, precise colors of make-up for each market segment, what chord progressions to use where, appropriate hand gestures and postures/positions, as well as camera angles for photoshoots, and details of when to use camera pans and montages in music videos ( Kang 2015 , 62).

Reaching Outward across the Globe

H.O.T, CLON, and g.o.d. were part of the first phase in Korean Wave’s internationalization—Korean Wave 1—reaching Japan, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, then Southeast Asia, and further afield alongside films such as Shiri (1999), Yŏpkijŏgin kŭnyŏ (My Sassy Girl, 2001), and Chobok manura (My Wife Is a Gangster, 2001), and TV dramas, including Kyŏul yŏn’ga (Winter Sonata, 2002), and the historical Taejanggŭm (Jewel in the Palace, 2003–2004). Winter Sonata first stormed Japan, where it was broadcast by NHK, and was then exported to much of the world, while Jewel in the Palace was broadcast from Australia to Zimbabwe. The financial crisis aided Korean Wave’s internationalization, since, as the Korean currency devalued, Korea’s soft culture became cheap compared to American or Japanese equivalents. The formula for dramas and films mixed the familiar with an appeal to East Asian values—moral and ethical codes inherited from Confucianism, without the excesses of Hollywood—and an idealized vision of what modern life should be. It packaged realism and irony. Success came because many Koreans had high levels of training and expertise, on one side the result of the export orientation pursued by the authoritarian regime prior to the 1990s, and on the other the legacy of student campaigns for democracy ( Howard 2013 ). Translated to K-pop, the formula called for a “de-Koreanized” ( Shin 2009 , 513–515) and culturally odorless “paradigm of transcultural hybridity” ( Jung 2011 , 3). 25 It mixed slick dance routines, rap with lyrical ballads, hooks, and sonic cues (including English riffs: consider Girls’ Generation’s 26 ‘Gee’ or Psy’s ‘Gangnam Style’), all delivered with the perfection expected of idol groups. 27

K-pop circulated during Korean Wave 1 in physical formats, but also through satellite and cable TV. Consumers were “sound trackers,” who practiced fandom by purchasing albums and idol-related merchandise. To counter the digital challenge, physical albums were packaged with glossy booklets, photocards, T-shirts, and more; some were cased or issued with multiple covers to encourage fans to buy additional copies. A second phase, Korean Wave 2, began after the launch of YouTube in 2005, as entertainment companies shifted their attention more explicitly to global markets. The three major companies switched to English on their social media platforms, and they targeted idols to specific markets. SM had already promoted BoA in Japan, her breakthrough there coming with the 2002 studio album Listen to My Heart , which had debuted at No. 1 on the Oricon Chart, and included songs by Japanese as well as Korean lyricists and composers. Again, one of the five members of H.O.T. had auditioned in America, and Korean Americans (along with Korean Canadians) were common in idol groups. Korean Wave 2 also recruited from the markets to be targeted, particularly from China and Taiwan (e.g., members of Super Junior (2005–), Victoria and Amber in f(x) (2009–), Fei and Jia in MissA (2010–2017), and Lay, Kris, Luhan, and Tao in Exo (2012–)); Japan (e.g., Momo, Sana, and Mina in Twice (2015–)); and Thailand (e.g., Nichkhun in 2PM (2008–2016) and Lisa in Blackpink (2016–)). 28

By utilizing social networks to allow individualized, private mimicry ( Jung and Hirata 2012 ), Korean Wave 2 expanded communities of active fans as companies encouraged participation. Fans became “dance trackers”: perfect synchronicity of idol dance in music videos remained a given, but choreography was made replicable so fans could create cover dances (Käng 2012 , 2014 ). 29 To facilitate this, the situated locations of videos common in Korean Wave 1 were replaced by blank stages (framed as dressing rooms, rehearsal spaces, empty streets, and so on) that gave little sense of anything immutably Korean. Official videos filled these stages with perfectly manicured and pedicured idol groups, but websites for fans supplemented these with mirror videos giving single-camera views of a performance. 30 Using these, fans practiced the moves, becoming, to use Henry Jenkins’ (2006) term, “prosumers.” Liew Kai Khiun explores the shift from “sound trackers” to “dance trackers,” listing a set of paired attributes (Korean Wave 1/Korean Wave 2): adult/adolescent, text/body, TV/YouTube, cognitive/physical, narrative/choreographed, soundtrack/dance track, resolution/synchronization, moment/movement, tears/sweat, experience/performance ( Khiun 2013 , 168).

Fandom continues to be leveraged. Fans support their idols by buying goods and products that offer rewards, gaining access to special events. They are encouraged to buy multiple copies of an album to push it up the charts, and to pay fees when their idols appear on TV shows by phoning in with multiple votes ( Kim 2018 , 8). They mediatize their participation at events by uploading clips they have captured on their smartphones to social media (2018, 11). Suk-Young Kim explores the 2013 production of the video for G-Dragon’s ‘ Niga muŏnde ’ (Who You): a thousand fans, who had bought the right merchandise, were invited to a warehouse where they surrounded a Perspex box. Inside sat a white Lamborghini and, of course, G-Dragon. As he performed the song, approaching and motioning to his swooning fans, the fans filmed him on their smartphones, jostling for the best view. At the end of the song, he drove the Lamborghini away, leaving the screaming fans. The fans distributed their clips online, but they were also filmed as part of the official music video, creating a “pixel textuality” in which they bought the commodity as they became commodified as props within it ( Kim 2018 , 123–130). 31

Fandom is attractive to researchers because it is observable, measuring “a particular type of media end-user,” who “extends their engagement beyond mere consumption, seeking out community” ( Keith 2019 , 134, after Jenkins 1992 ). It has become popular to measure K-pop’s success through its fandom, and this is precisely what the Korea Foundation report cited at the beginning of this essay measures. Indeed, fandom is the focus of a recent volume on Korean Wave ( Park, Otmazgin, and Howard 2019 ). But Korea’s entertainment companies have long targeted much larger groups of what Keith terms “passive fans” (2019, 147). Passive fans are identified in an emerging, softer take on fandom (for which see Duffett 2013 ): they service both the B2B model (justifying commercial sponsorship) and government investment and promotion (using K-pop to brand Korea). Fans may consume K-pop privately, particularly where this avoids negative stereotyping ( Williams 2016 ), but passive fans may also be socially engaged, because among friends they share their K-pop interest. But, with their interest piqued by K-pop, they go on to buy other Korean products—cars, smartphones, TVs, and washing machines. Among today’s global youth, passive fans of K-pop number many times more than the easily observable “prosumers.” 32

Local Turns Global: Gender, Cuteness, and Sexualization

Broadly speaking, Korean Wave 1 inherited gender norms from East Asia’s past, in which a woman was the “girl next door,” cute ( aegyo ), but sexually veiled. In the 1980s and 1990s, the singer Lee Sun Hee epitomized this image. She wore her hair short and wore spectacles portraying the image of a dedicated student—as if she had just come out of a university library. Cuteness was explored by girl groups, such as FinK.L, launched in 1998, who in videos danced gently, always dressed in virginal white or pastel long, flowing costumes. As Korean Wave 2 arrived, cuteness was replaced by bubble-gum dollification. This was displayed in the 2007 debuts of Wonder Girls and Girls’ Generation ( Jung 2013 , Epstein and Turnbull 2014 ). To attract the male gaze, however, overt sexualization soon became normalized ( Kim 2011 ). Consider, in this regard, Cube Entertainment’s 4Minute, who launched in 2009, and the solo idol G.Na, promoted as 168cm tall, 48kg in weight, and with natural D-cup breasts—who complained she could not buy bras in Korea. 33 G.Na had been expected to debut in 2007 with the group Five Girls, but her entertainment company ran into financial trouble, so her eventual EP debut, Draw G’s First Breath , was not released until 2010.

To some, girl idol videos verge on the pornographic ( Kim 2019 , 74 and 83), but sexual objectification functions within the internationalization aspect of Korean Wave 2, responding to the Western stereotype of Asia, in which Asian female sexuality is celebrated while the Asian male is perceived as weak and non-threatening. 34 Spoon-fed to American consumers by the media ( Wu 2002 ; Prasso 2005 ), this was long ago the portrayal of Gustave Flaubert and Richard Burton, and of Paul Gauguin’s canvasses; “the Orient” was, because of its imagined female sexualization, associated with “the freedom of licentious sex” ( Said 1978 , 190). Brown Eyed Girls, who debuted in 2006 with the R&B ‘ Tagawasŏ ’ (Come Closer), went some way to juxtapose the overtly sexual with women’s equality, although the pretense of the latter was lost by the time of ‘Abracadabra’ (2009) and in Ga-In’s reprise of her contribution to this as a foil to male entitlement in Psy’s ‘Gentleman’ (2013). Her controversial “F**K U” (2014) claimed to display a strong woman, but Ga-In’s slinky negligee and close-up pouting suggested otherwise; the contradictions remain in 2015’s ‘Paradise Lost,’ despite the claim to combine art, sensuality, and sexiness.

Companies, though, actively targeted market segments, and, notwithstanding the lesbian intimations at the end of ‘Abacadabra,’ a metrosexual, LGBTQi-friendly image arrived with the American Taiwanese Amber Liu ( Laforgia and Howard 2017 ). She debuted with the girl idol group f(x) in 2009, her androgyny emphasized by loose tank tops and cargo pants contrasting the body-accentuating short, tight skirts, and heels of her fellow group members. In ‘ Chŏt sarangni ’ (Rum Pum Pum Pum, 2013), she wore tartan basketball shorts and tops, while her four fellow idols were in shirts over miniscule shorts. Again, at the opening of ‘4 Walls’ (2015), her t-shirt contrasts another member in a negligee, and as the song gets underway, her shirt and pants contrast Krystal and Luna in tight tops revealing their belly buttons and Victoria in a short shift dress. Amber kept fans guessing: was she lesbian, bisexual, or just a tomboy? Or, since she was under contract, was she merely acting out a role created for her by her company? 35

The rules for men were different; how could they be otherwise in the wake of Hong Kong’s martial arts films? Within Korean Wave 1, CLON and the 1997-debuting Korean American Yoo Seungjun portrayed strong masculinity, at gigs stripping off tops to allow teenage fans to ogle their muscles and tattoos (strict control meant they had to remain fully dressed for media appearances). In contrast, ballad-inheriting male idols championed a softer masculinity, which was shared with the stars of films and dramas, most famously Bae Yong Joon (Yonsama to his Japanese fans) in Winter Sonata ; this recalled the Confucian scholar-gentleman ( sonbi ) of previous centuries. The two sides fused in the pan-Asian Rain’s (Jung Ji-hoon’s) “man’s body with a boy’s face,” or “angelic face and a killer body” ( Kim 2013 , 20, citing Shin 2009 ; see also Jung 2011 , 73–118). Rain’s music videos, however, abandoned subtlety—consider, with no pun intended, ‘I’m Coming,’ ‘Rainism,’ and ‘It’s Raining.’ 36 Rain was one of the first idols to look to America, when he performed at Madison Square Gardens, and “world tours” confirmed his large Southeast Asian fan following. His pan-Asian identity led to acting, first in the Korean TV drama Full House (2004), and then in the Hollywood films Speed Racer (2008) and Ninja Assassin (2009). Korean Wave 2 brought a newer metrosexual male, which, on one side, softened masculinity—through cosmetic surgery—with groups such as Cube’s Beast (in 2017 repackaged as Highlight), who debuted in 2009 with the mini-album Beast Is the B2ST . 37 On the other side, strong masculinity left Asian males entwining with white, provocative Euro-American muses in Gary’s (Lee Ssang’s) ‘ Chogŭm itta sawŏhae ’ (Shower Later, 2013) and in the venerable Yoon Do-hyun band update of ‘Cigarette Girl’ (2014). Again, were boy idols merely acting out roles created by their companies as they targeted market segments?

Gone Global: ‘Gangnam Style’

An excerpt of the official video for ‘Gangnam Style’ was uploaded to YouTube on July 11, 2012. The full video was released four days later. ‘Gangnam Style’ was the opening track on Psy’s (Park Jae-sang’s) sixth album. It was his eighteenth single. It resurrected the outdated Western stereotypes of Asian gender identity, and the video backdrops suggested Korean Wave 1 territory. But it quickly came to signify Korean Wave 2’s “dance trackers,” as flash mobs of up to twenty thousand people broke out in Pasadena, New York’s Times Square, and Sydney, Australia. Flash mobs soon multiplied to, among other places, Seoul, Sulawesi, Milan, Paris, and Rome.

Not everybody was enthusiastic. “Can anyone kill Gangnam Style?,” asked The Guardian online blog on November 14, 2012. “It is the cringe-proof meme, the zombie meme, the meme that knows no shame. Quite possibly, it will be danced by grannies at weddings in 2030—the twenty-first-century equivalent of the conga line; the new Macarena.” 38 Why, Time magazine asked on October 1, 2012, had the song not died after Google’s fifty-seven-year-old Eric Schmidt danced to it? Many others re-hashed the “horse riding” dance, but nobody could damp enthusiasm. Some even suffered as a consequence, and Time returned to ‘Gangnam Style’ on April 3, 2014, reporting how a policeman in Falmouth, Cornwall, had been sacked for dancing to the song in an effort to raise money for a dying child. Back in 2012, as summer moved to autumn, comments on The Guardian ’s blog suggested deepening despair, as ‘Gangnam Style’ became evermore impossible to escape: “Shut up, South Korea!,” “I hate the song!,” ‘Gangnam Style’ challenged many K-pop fans, who resisted its simple dance moves that subsumed aesthetics beneath banal imaging. They were unhappy that it reverted back to stereotyping, featuring a “podgy comic singer and long-legged beauties,” (as Korea Times put it on December 5, 2012) and that it made fun of the daily grind that was life in Korea, generating a “sudden attractiveness or sarcastic humor of an actor’s culture” ( Nye and Kim 2013 , 33).

It generated parodies. One of the first was contributed by the duo behind the EatYourKimchi YouTube channel, Simon and Martina Stawski. Keeping some of the imaging behind a new soundtrack, their parody was uploaded to YouTube on July 23, 2012. 39 Barely six weeks later, on September 3, the duo announced on Al-Jazeera TV that ‘Gangnam Style’ should not be considered K-pop, and that, while Psy deserved popularity abroad, ‘Gangnam Style’ was in no way representative of Korean Wave. 40 But even in Korea, ‘Gangnam Style’ proved immensely popular, holding the top spot on many domestic charts from its launch in July 2012 until Psy stopped official promotion in February 2013. Abroad, the fuse for its success was lit by celebrities. Former Take That member Robbie Williams mentioned it on his blog on July 28, 2012, and the next day it was tweeted by rapper T-Pain. On July 30, Scooter Braun picked up and tagged the video, tweeting, rhetorically: “HOW DID I NOT SIGN THIS GUY!?!??!” Soon, his Raymond Braun Media Group concluded a contract with Psy, placing the Korean alongside others he managed, such as Justin Bieber and M.C. Hammer. On August 1, the Daily Beast tagged ‘Gangnam Style,’ as its video passed ten million YouTube views. A month later, and after singer Katy Perry had shared the video with her followers, it had notched up one hundred million views. By the end of September, it was at the second spot on the Billboard charts after an estimated thirty-four million Americans had listened to it. At the time, Bieber’s “Baby” held the record for the most YouTube views, but ‘Gangnam Style’ breezed past it. Views surpassed a billion, then two billion, then three billion—YouTube, reportedly, had to recalibrate its systems multiple times. Psy performed on the Ellen DeGeneres Show . He taught Britney Spears the dance moves. He was a guest alongside Taylor Swift on ABC’s New Year’s Eve Show . The Tonight Show with Jay Leno presented a number of parodies at the expense of America’s politicians. ‘Gangnam Style’ featured on ABC’s Dancing with the Stars , and infamously but somewhat later on BBC TV’s Strictly Come Dancing , when a judge remarked about the former Labour politician Ed Balls’s interpretation: “I don’t think there’s any words in the dictionary to describe that.”

‘Gangnam Style’ quickly become an icon of popular culture. In October 2012, South Park ’s Halloween party, “A Nightmare on FaceTime,” replaced Frankenstein with GangnamStein. In 2013, it featured in films such as This Is the End , and the documentary Linsanity , and a character from the song’s video danced in My Little Pony: Equestria Girls . In 2014, a cartoon version of Psy appeared in the credits for (and in adverts for) The Nut Job . 41 The song was eminently mashable—in previous decades, one might have expected covers or remixes, but ‘Gangnam Style’ was “born to spawn” (as Arwa Mahdawi put it in The Guardian on September 24, 2012). On YouTube, it generated several hundred thousand parodies, which typically took the song and made it something else by and for American farmers, Eton schoolboys, firemen, civil servants, computer nerds, politician avatars, Siberian Yeti imitators. Anybody who wanted to, including plenty of classes of Korean Studies’ students, got involved. In the age of social media, parodies of ‘Gangnam Style’ functioned as alternatives to Twitter’s 280-characters, or selfies, and were made and uploaded to YouTube “country-by-country, occupation-by-occupation and school-by-school” ( Ono and Kwon 2013 , 209). Psy (and Braun) allowed those who made parodies to project themselves online, taking click fees but not invoking intellectual property rights. ‘Gangnam Style’ became, to quote Tim Byron in The Vine , 42 “a piece of shared currency which can be taken as a known in a world which is increasingly nicheified.” As Psy lamented on BBC1 Radio on October 5, 2012, “The problem is that my music video is more popular than I am.”

An exception to the self-culture parody was ‘London Style,’ co-produced by Kim Mose and Cho Hanbit with Korean, Japanese, and British students, and uploaded to YouTube on September 16, 2012. This mirrored Psy’s imaging and lip-synched his lyrics, but portrayed daily life in London rather than modern life in Seoul, from coffee shops to the subway, and from Big Ben to Harry Potter’s Platform 9¾ at Kings Cross Station. A follow-up video, in which Cho starred as an improvising pianist, ‘Gangnam Style Piano Tribute,’ started with the free-to-use piano at St. Pancras Station, and took respect for the original song even further. 43

‘Gangnam Style,’ though, is itself a parody. It lambasts modern life in Seoul, particularly the affluent apartment district of Gangnam, but is partly filmed in down-at-heels locations outside Seoul. Its protagonist is a failure. He sunbathes in a tiny park as children go to school around him. He frantically cycles a pedalo beside an artificial beach on the polluted river. He gets cast aside by the wealthy owner of a red Mercedes sports car, in a basement car park full of grey and black Hyundais. And he forlornly hopes he might get lucky with the beautiful girls (particularly Hyuna, who pole dances on the subway). The song’s memes simply cast these images aside as they couple the relatively simple dance moves to framed images of, well, farming, firefighting, school, and so on. Devoid of the original song’s own parody, the memes enabled it to return to Korea de-Koreanized and culturally odorless. In this paradigmatic form, it took center stage in the February 2013 inauguration of the incoming president of South Korea, Park Geun-hye, the daughter of the general-turned-president Park Chung Hee. She was indelibly linked to her father’s autocratic regime, hence the song’s most prominent lyric, “Hey, sexy lady!” (delivered, of course, in English) was the diametrical opposite of Park’s image. So was the first verse, where Psy describes a classy girl enjoying coffee during the day whose heart becomes hot in the evenings.

Ironically, when in December 2016 public demonstrations broke out in Seoul, night after night, as citizens challenged Park’s supposed corruption, leading, eventually, to her impeachment, citizens took to the streets to the sound K-pop. As their anthem they choose g.o.d’s ‘One Candle,’ from 2000, originally released during Korean Wave 1. This describes how a single candle throws out only a little light, but the light grows when a second candle is lit. More and more candles are lit, dispelling the darkness, and showing up the reality of what is going on.

Creating Local and Global Idols: Marking Success and Failure