Pioneering Social Reformer Jacob Riis Revealed “How The Other Half Lives” in America

How innovations in photography helped this 19th century journalist improve life for many of his fellow immigrants

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

Jimmy Stamp

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/6a/656af4d0-d828-456a-9863-e94f8f9241b8/be031677.jpg)

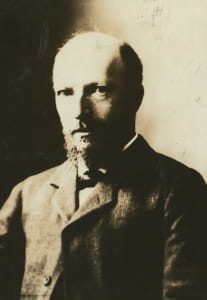

In 1870, when Jacob August Riis immigrated to America from Denmark on the steamship Iowa , he rode in steerage with nothing but the clothes on his back, 40 borrowed dollars in his pocket, and a locket containing a single hair from the girl he loved. It must have been hard for the 21-year-old Riis to imagine that in just a few short years, he would be pallin’ around with a future president, become a pioneer in photojournalism, and help reform housing policy in New York City.

Jacob Riis, who died 100 years ago this month, struggled through his first few years in the United States. Unable to find a steady job, he worked as a farmhand, ironworker, brick-layer, carpenter, and salesman, and experienced the worst aspects of American urbanism--crime, sickness, squalor--in the low-rent tenements and lodging houses that would eventually inspire the young Danish immigrant to dedicate himself to improving living conditions for the city’s lower-class.

Through a little bit of luck and a lot of hard work, he got a job as a journalist and a platform for exposing the plight of the lower class community. Eventually, Riis became a police reporter for The New York Tribune, covering some of the city's most crime-ridden districts, a job that would would lead to fame and a friendship with police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who called Riis "the best American I ever knew." Riis knew what it was to suffer, to starve, and to be homeless, and, though his prose was sometimes sensationalist and even occasionally prejudiced, he had what Roosevelt called "the great gift of making others see what he saw and feel what he felt."

But Riis wanted to literally show the the world what he saw. So, to help his readers truly understand the dehumanizing dangers of the immigrant neighborhoods he knew all too well, Riis taught himself photography and began taking a camera with him on his nightly rounds. The recent invention of flash photography made it possible to document the dark, over-crowded tenements, grim saloons and dangerous slums. Riis’s pioneering use of flash photography brought to light even the darkest parts of the city. Used in articles, books, and lectures, his striking compositions became powerful tools for social reform.

Riis’s 1890 treatise of social criticism How the Other Half Lives was written in the belief “that every man’s experience ought to be worth something to the community from which he drew it, no matter what that experience may be, so long as it was gleaned along the line of some decent, honest work.” Full of unapologetically harsh accounts of life in the worst slums of New York, fascinating and terrible statistics on tenement living, and reproductions of his revelatory photographs, How the Other Half Lives was a shock to many New Yorkers - and an immediate success. Not only did it sell well, but it inspired Roosevelt to close the worst of the lodging houses and spurred city officials to reform and enforce the city’s housing policies. To once again quote the future President of the United States: “The countless evils which lurk in the dark corners of our civic institutions, which stalk abroad in the slums, and have their permanent abode in the crowded tenement houses, have met in Mr. Riis the most formidable opponent every encountered by them in New York City.”

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

Jimmy Stamp | | READ MORE

Jimmy Stamp is a writer/researcher and recovering architect who writes for Smithsonian.com as a contributing writer for design.

Helpful Links

- Email Signup

- MY.NOMA ACCOUNT

New Orleans Museum of Art

Object lesson: photographs by jacob august riis.

Jacob August Riis, (American, born Denmark, 1849–1914), Untitled , c. 1898, print 1941, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Milton Esterow, 99.362

When the reporter and newspaper editor Jacob Riis purchased a camera in 1888, his chief concern was to obtain pictures that would reveal a world that much of New York City tried hard to ignore: the tenement houses, streets, and back alleys that were populated by the poor and largely immigrant communities flocking to the city. Riis knew that such a revelation could only be fully achieved through the synthesis of word and image, which makes the analysis of a picture like this one—which was not published in his How the Other Half Lives (1890)—an incomplete exercise. Nevertheless, Riis’s careful choice of subject and camera placement as well as his ability to connect directly with the people he photographed often resulted, as it does here, in an image that is richly suggestive, if not precisely narrative. The two young boys occupy the back of a cart that seems to have been recently relieved of its contents, perhaps hay or feed for workhorses in the city. Maybe the cart is their charge, and they were responsible for emptying it, or perhaps they climbed into the cart to momentarily escape the cold and wind. Dirt on their cheeks, boot soles worn down to the nails, and bundled in worker’s coats and caps, they appear aged well beyond their years—men in boys’ bodies. The broken plank in the cart bed reveals the cobblestone street below. The street and the children’s faces are equidistant from the camera lens and are equally defined in the photograph, creating a visual relationship between the street and those exhausted from living on it.

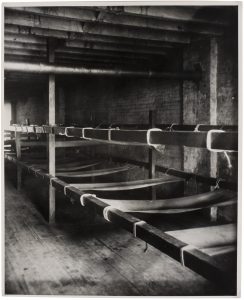

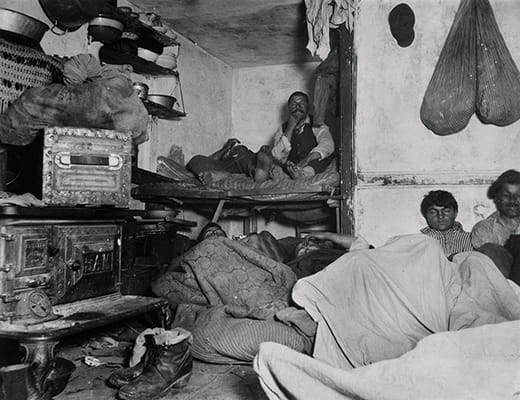

Jacob August Riis (American, born Denmark, 1849–1914), Bunks in a Seven-Cent Lodging House, Pell Street , c. 1888, Gelatin silver print, printed 1941, Image: 9 11/16 x 7 13/16 in. (24.6 x 19.8 cm); sheet: 9 7/8 x 8 1/16 in. (25.1 x 20.5 cm), Gift of Milton Esterow, 99.377

A photograph may say much about its subject but little about the labor required to create that final image. For Jacob Riis, the labor was intense—and sometimes even perilous. In the service of bringing visible, public form to the conditions of the poor, Riis sought out the most meager accommodations in dangerous neighborhoods and recorded them in harsh, contrasting light with early magnesium flashes. The technology for flash photography was then so crude that photographers occasionally scorched their hands or set their subjects on fire. Even if these problems were successfully avoided, the vast amounts of smoke produced by the pistol-fired magnesium cartridge often forced the photographer out of any enclosed area or, at the very least, obscured the subject so much that making a second negative was impossible. As a result, many of Riis’s existing prints, such as this one, are made from the sole surviving negatives made in each location.

This picture was reproduced as a line drawing in Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1890). The accompanying text describes the differences between the prices of various lodging house accommodations. The seven-cent bunk was the least expensive licensed sleeping arrangement, although Riis cites unlicensed spaces that were even cheaper (three cents to squat in a hallway, for example). The canvas bunks pictured here were installed in a Pell Street lodging house known as Happy Jack’s Canvas Palace. Without any figure to indicate the scale of these bunks, only the width of the floorboards provides a key to the length of the cloth strips that were suspended from wooden frames that bow even without anyone to support. By focusing solely on the bunks and excluding the opposite wall, Riis depicts this claustrophobic chamber as an almost exitless space. Only the faint trace of light at the very back of the room offers any promise of something beyond the bleak present.

— Russell Lord , Freeman Family Curator of Photographs

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.

▶ DONATE NOW

Let's stay connected.

Jacob A. Riis

Revealing new york's other half, october 14, 2015 - march 20, 2016.

- Visit MCNY on Instagram

- Visit MCNY on TikTok

- Visit MCNY on Facebook

- Visit MCNY on Threads

- Visit MCNY on Youtube

- Sign up for our mailing list

Back to Past Exhibitions

Jacob Riis (1849-1914) was a pioneering newspaper reporter and social reformer in New York at the turn of the 20th century. His then-novel idea of using photographs of the city’s slums to illustrate the plight of impoverished residents established Riis as forerunner of modern photojournalism. Jacob A. Riis: Revealing New York’s Other Half features photographs by Riis and his contemporaries, as well as his handwritten journals and personal correspondence.

This is the first major retrospective of Riis’s photographic work in the U.S. since the City Museum’s seminal 1947 exhibition, The Battle with the Slum , and for the first time unites his photographs and his archive, which belongs to the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library.

The exhibition is curated by Bonnie Yochelson, former Curator of Prints and Photographs at the City Museum, and is co-presented by the Library of Congress. It will travel to Washington, D.C., and to Denmark following its presentation at the City Museum.

Yale University Press, the City Museum, and the Library of Congress also co-published a book on the occasion of the exhibition.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via email

- "Jacob Riis Photographs Still Revealing New York’s Other Half" The New York Times

- "Revealing Riis’s Other Half of New York" New York Times LENS

- "The heartbreaking pictures of New York's slums that prompted social reform and earned immigrant photographer praise as the city's 'most useful citizen'" Daily Mail

- "New Exhibit Reveals an Unexpected Side of Jacob A. Riis" American Photo

- "Century-Old Jacob Riis Photographs of New York's 'Other Half' On View" Curbed

- "NYC Museum Retrospective of Photojournalist Jacob Riis" ABC News

- "Museum of the City of New York Spotlights Jacob A. Riis and the ‘Other Half’" Women's Wear Daily

Read the press release.

VIEW PHOTOS

Our Jacob A. Riis Collection encompasses more than 1,000 photos and serves as the sole archive of Riis's images. Browse the Collections Portal.

Stay Connected. Get our Newsletter.

Get the latest on events, upcoming exhibitions, and more.

Want free or discounted tickets, special event invites, and more?

Visit us at the museum today.

How the Other Half Lives

Jacob Riis' lens on New York's immigrant slums

Jacob August Riis, “Knee-pants” at forty five cents a dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop , c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York , Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

The slums of New York

Jacob Riis documented the slums of New York, what he deemed the world of the “other half,” teeming with immigrants, disease, and abuse. A police reporter and social reformer, Riis became intimately familiar with the perils of tenement living and sought to draw attention to the horrendous conditions. Between 1888 and 1892, he photographed the streets, people, and tenement apartments he encountered, using the vivid black and white slides to accompany his lectures and influential text, How the Other Half Lives , published in 1890 by Scribner’s. His powerful images brought public attention to urban conditions, helping to propel a national debate over what American working and living conditions should be.

Jacob August Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York , Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890

A Danish immigrant, Riis arrived in America in 1870 at the age of 21, heartbroken from the rejection of his marriage proposal to Elisabeth Gjørtz. Riis initially struggled to get by, working as a carpenter and at various odd jobs before gaining a footing in journalism. In 1877 he became a police reporter for The New York Tribune , assigned to the beat of New York City’s Lower East Side. Riis believed his personal struggle as an immigrant who “reached New York with just one cent in my pocket”¹ shaped his involvement in reform efforts to alleviate the suffering he witnessed.

As a police reporter, Riis had unique access to the city’s slums. In the evenings, he would accompany law enforcement and members of the health department on raids of the tenements, witnessing the atrocities people suffered firsthand. Riis tried to convey the horrors to readers, but struggled to articulate the enormity of the problems through his writings. Impressed by the newly invented flash photography technique he read about, Riis began to experiment with the medium in 1888, believing that pictures would have the power to expose the tenement-house problem in a way that his textual reporting could not do alone. Indeed, the images he captured would shock the conscience of Americans.

Jacob August Riis, The Mulberry Bend , c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York , Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

Midnight rounds

At first Riis engaged the services of a photographer who would accompany him as he made his midnight rounds with the police, but ultimately dissatisfied with this arrangement, Riis purchased a box camera and learned to use it. The flash technique used a combination of explosives to achieve the light necessary to take pictures in the dark. The process was new and messy and Riis made adjustments as he went. First, he or his assistants would position the camera on a tripod and then they would ignite the mixture of magnesium flash-powder above the camera lens, causing an explosive noise, great smoke, and a blinding flash of light. Initially, Riis used a revolver to shoot cartridges containing the explosive magnesium flash-powder, but he soon discovered that showing up waving pistols set the wrong tone and substituted a frying pan for the gun, flashing the light on that instead. The process certainly terrified those in the vicinity and also proved dangerous. Riis reported setting two fires in places he visited and nearly blinding himself on one occasion.

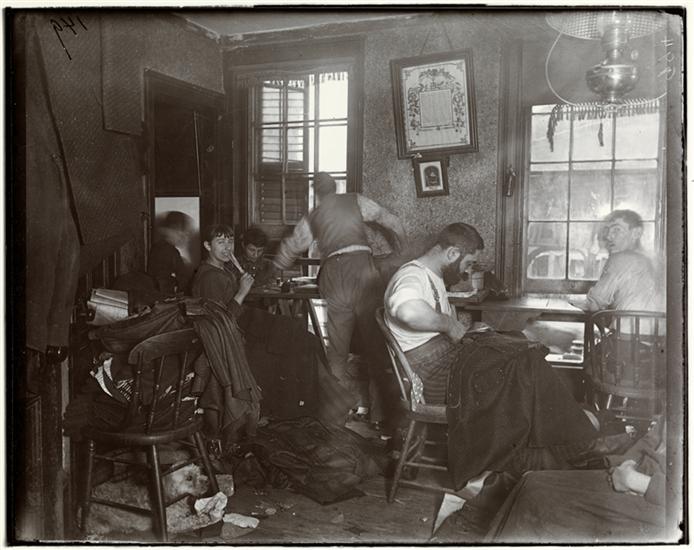

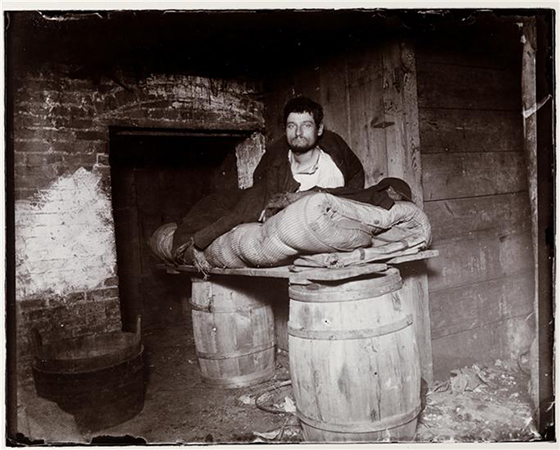

Jacob August Riis, “A man atop a make-shift bed that consists of a plank across two barrels,” c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York , Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

Home and work

While it is unclear if Riis’ pictures were totally candid or posed, his agenda of using the stark images to persuade the middle and upper classes that reform was needed is well documented. A major theme of Riis’ images was the terrible conditions immigrants lived in. In the 1890s, tenement apartments served as both homes and as garment factories. “Knee-Pants at Forty-Five Cents a Dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop” depicts the intersection of home and work life that was typical. Note the number of people crowded together making knickers and consider their ages, gender, and role. Each worker would be paid by the piece produced and each had his/her own particular role to fill in the shop which was also a family’s home.

Detail, Jacob August Riis, “Knee-pants” at forty five cents a dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop , c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York , Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

While Riis did not record the names of the people he photographed, he organized his book into ethnic sections, categorizing the images according to the racial and ethnic stereotypes of his age. In this regard, Riis has been criticized for both his bias and reducing those photographed to nameless victims. “Knee-Pants,” appears in the chapter Jewtown and one can assume that the individuals are part of the large wave of Eastern European Jewish migration that flooded New York at the turn of the twentieth century.

Detail of the “Table of Contents,” Jacob August Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York , Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1914

They are likely conversing in Yiddish and share some type of familial or neighborly connection. Some of the workers depicted might have lived in a neighboring New York City apartment or next door back in the old country. Home life, family relations and business relations, are intertwined. Just as it is impossible to know the names of the people captured in Riis’ image, and what Riis actually thought of them, one also cannot know their own impressions of the workplace, or their hopes and day-to-day challenges.

Jacob August Riis, “12 year old boy at work pulling threads. Had sworn certificate he was 16—owned under cross-examination to being 12. His teeth corresponded with that age,” c. 1890, 7 x 6″, from How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York , Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1890 (The Museum of the City of New York)

The work performed in tenements like these throughout the Lower East Side made New York City the largest producer of clothing in the United States. Under the contracting system, the tenement shop would be responsible for assembling the garments, which made up the bulk of the work. By 1910, New York produced 70% of women’s clothing and 40% of men’s ready-made clothing. That meant that the knee-pants and garments made by the workers captured in this Ludlow Street sweatshop were shipped across the nation. Riis’ photographs helped make the sweatshop a subject of a national debate and the center of a struggle between workers, owners, consumers, politicians, and social reformers.

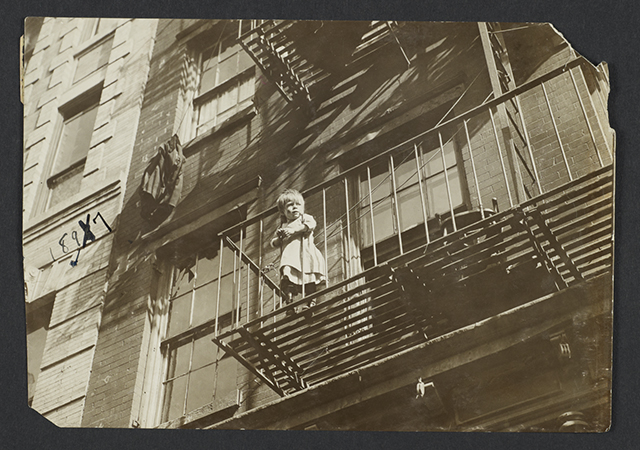

The Progressive Era

Riis’ photographs are part of a larger reform effort undertaken during the Progressive Era, that sought to address the problems of rapid industrialization and urbanization. Progressives worked under the premise that if one studies and documents a problem and proposes and tests solutions, difficulties can ultimately be solved, improving the welfare of society as a whole. Progressives like Riis, Lewis Hine, and Jessie Tarbox Beals pioneered the tradition of documentary photography, using the tool to record and publicize working and housing conditions and a renewed call for reform. These efforts ultimately led to government regulation and the passage of the 1901 Tenement House Law, which mandated new construction and sanitation regulations that improved the access to air, light, and water in all tenement buildings.

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Child on Fire Escape, c. 1918, for the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor ( Columbia University Libraries )

In the introduction to the How the Other Half Lives , Riis challenged his readers to confront societal ills, asking “What are you going to do about it? is the question of to-day.” It was a question of the past, but one that endures.

1. Jacob Riis, The Making of An American , 2: 18

Jacob A. Riis Photographic collection, The Museum of the City of New York

Lower East Side Tenement Museum virtual tour of the Levine family’s home and sweatshop in 1897 at 97 Orchard Street, New York City

Ginia Bellafante, Discussion on How the Other Half Lives , The New York Times

Texts by Jacob Riis online bartleby.com

“Jacob Riis and the Other Half” website by Lisa Xie

Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom, Rediscovering Jacob Riis: Exposure Journalism and Photography in Turn-of-the-Century New York ( Chicago University Press, 2014).

Find this essay in...

Seeing america.

- Theme: Work, Exchange, and Technology

- Period: 1877 - 1898

- Topic: City and country

Art histories

- Jacob Riis, "Knee-Pants" at Forty-Five Cents a Dozen—A Ludlow Street Sweater’s Shop , from How the Other Half Lives

Explore the diverse history of the United States through its art. Seeing America is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Alice L. Walton Foundation.

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Support ICP

- Become a Member

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Early documentary photography.

The Terminal

Alfred Stieglitz

From the El

Paul Strand

The Steerage

A Holiday Visit

Arnold Genthe

Blind Woman, New York

Doylestown House—The Stove

Charles Sheeler

Abstraction, Twin Lakes, Connecticut

11:00 A.M. Monday, May 9th, 1910. Newsies at Skeeter's Branch, Jefferson near Franklin. They were all smoking. Location: St. Louis, Missouri.

[Wire Wheel]

[Nude with a Mask]

E. J. Bellocq

[Geometric Backyards, New York]

Harold Greengard, Twin Lakes, Connecticut

Rebecca, New York

Vaux #2, After Attack

Edward J. Steichen

The Human U.S. Shield

Mole and Thomas

Department of Photographs , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

By the beginning of the twentieth century, photography was well on its way to becoming the visual language it is today, the pervasive agent of democratic communication. Photographers used its growing influence to expose society’s evils, which the prosperous, self-indulgent Belle Époque chose to ignore: the degrading conditions of workers in big-city slums, the barbarism of child labor, the terrorism of lynching, the devastation of war.

Despite Alfred Stieglitz’s early interest in candid or snapshot-style street photography seen in The Terminal of 1893 ( 58.577.11 ) and The Steerage of 1907 ( 33.43.419 ), he attempted to turn the page on the natural development of the documentary tradition in photography with his successful 1910 retrospective of Pictorialism at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. If the age of electricity, the automobile, and the telephone would, by caveat, be ignored by the Pictorialists, modern realities in the 1890s to 1910s would nonetheless appear in images produced by tens of thousands of artists and amateurs who found the world intoxicatingly attractive, if at times disorderly and brutal. Alongside selected examples of the work of Stieglitz and members of his circle (Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler , and Edward J. Steichen ), the photographs of Jacob Riis, Arnold Genthe, Lewis Hine, and E. J. Bellocq, among others, provide a sampling of early documentary practice in America.

Jacob Riis (1849–1914) was a police reporter for the New York Tribune newspaper. In the early 1880s, he supplemented his investigative reporting of the city’s notorious Lower East Side slums with his own photographs and soon became known as one of the city’s most important social reformers. An immigrant from Denmark to the United States in 1870, Riis, who originally trained to be a carpenter, published his first and most important book, How the Other Half Lives , in 1890. The catalyst for citywide reform of building codes and slumlord-tenant relations, the book continues to serve as a model for all photographers and urban historians dedicated to social change within the city.

Born in Berlin, Arnold Genthe (1869–1942) received a doctorate in philosophy in 1894 and moved to California the following year to tutor the son of a wealthy German baron and San Francisco heiress. He died a naturalized citizen in New York City in 1942 after fifty years of camera work, primarily in portraiture, published in nine photography books. His first publication, Pictures of Old Chinatown (1908), reveals the artist’s decade-long obsession with the exotic flavor of San Francisco’s eight square blocks that comprise its Chinatown. With no prior experience in photography, Genthe would acquire one of the newly invented small handheld cameras and proceed to photograph the foreign inhabitants ( 53.680.6 ), their brocades and embroideries, their bronzes and porcelains, as well as the district’s dark alleys and opium dens. In so doing, he mastered the nascent art of what much later came to be known as “street photography.”

In 1908, Lewis Hine (1874–1940) left his teaching position at the progressive Ethical Culture School in New York City to become a staff photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, an organization dedicated to improving the working and living conditions of children. Over the next thirteen years, Hine made thousands of negatives—often undercover—of children working across the country in mills, sweatshops, factories, and various street trades, such as newspaper delivery ( 1970.727.1 ). Through a steady accumulation of specific, idiosyncratic facts, the photographer hoped to reveal the larger, hidden patterns of child exploitation upon which the American city was rapidly expanding. More important, his reports and slide lectures were not meant solely as tools for labor reform but as ways of triggering a more profound, empathetic response in the viewer, one that would cause him to reconsider his relationship to society.

Ernest J. Bellocq (1873–1949) was born into an aristocratic Creole family in New Orleans. A prominent member of the New Orleans Camera Club, he worked as a professional photographer specializing in shipbuilding. Bellocq’s international renown, however, was established by a series of intimate, mildly erotic portraits of prostitutes working around 1912 in Storyville, the city’s infamous tenderloin district ( 2005.100.130 ). When discovered by the photographer Lee Friedlander in the 1960s and published in 1970, Bellocq was immediately recognized as a master of the modern, psychological portrait—an instant ancestor for a whole generation of contemporary artists including Diane Arbus.

In 1915, Stieglitz’s flagging interest in American Pictorialist photography was revived by the work of three young photographers: Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), Morton Schamberg (1881–1918), and Paul Strand (1890–1976). Sheeler and Schamberg were both academically trained painters from Philadelphia who had studied modern art in Europe and New York. Although each believed painting was their true vocation, they took up photography to earn a living; Sheeler specialized in architecture, Schamberg in portraiture.

When Charles Sheeler took up the camera sometime in 1910–11, he was already a modestly accomplished painter. He began to photograph domestic architecture in the Philadelphia area, and within three years had a successful sideline documenting fine private and public American collections of Chinese bronzes, Mesoamerican pots, and modern painting and sculpture by Cézanne , Picasso , and Duchamp . The rigorous demands of detailed record photography soon influenced his painting as the direct, generally frontal assessment of both an object’s form and structure retrained and refined his eye. By 1917, Sheeler had begun to turn his camera from commercial work to subjects of personal significance, such as the eighteenth-century farmhouse in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, that he and Schamberg used as a studio. Sheeler saw in its spare construction a formal purity as clear as the practical intention of the carpenter. In a black stove ( 33.43.259 ), he found a material abstraction undivorced from actuality and unembellished by decoration. For him, the farmhouse was a structure of elementary geometries, a series of Cubist compositions unadorned by painterly camouflage.

Paul Strand first visited Stieglitz’s Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession in 1907 as a student in a class taught by Lewis Hine. Hine’s photography was absolutely straightforward documentary, but at that time Stieglitz was promoting the gauzy Pictorialism of his Secessionist fellows. Strand dutifully followed suit, but eventually Stieglitz encouraged his young protégé to abandon the soft-focus technique and to explore movement in the city and the geometric shapes of urban structures. Stieglitz gave Strand a show in March 1916 and published a selection of his pictures in Camera Work , the journal which had appeared regularly since 1914. Following his exhibition, Strand’s advances accelerated and his pictures became startlingly bold ( 33.43.334 ; 49.55.318 ).

The outbreak of World War I essentially ended the Pictorialist movement as a viable aesthetic program. The inherent violence of the war soon engendered a new commitment by the world’s photographers to document every aspect of the fighting, from life in the trenches to views of fighter planes cruising the skies. Nothing was left hidden from the camera’s burrowing eye. The American commercial photographic firm of Mole & Thomas made many composite scenes of soldiers ( 1987.1100.478 )—studies of seeming unity, strength, and organized patriotism far from the frontlines. Edward Steichen, flying high above the soldiers in a reconnaissance plane, generated its antipode: a view of brutal destruction and death on a field in France ( 1987.1100.109 ).

Department of Photographs. “Early Documentary Photography.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/edph/hd_edph.htm (October 2004)

Additional Essays by Department of Photographs

- Department of Photographs. “ Photography and the Civil War, 1861–65 .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004) .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Early Photographers of the American West: 1860s–70s .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Eugène Atget (1857–1927) .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Photography and Surrealism .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Thomas Eakins (1844–1916): Photography, 1880s–90s .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Walker Evans (1903–1975) .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Photography at the Bauhaus .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ The Daguerreian Era and Early American Photography on Paper, 1839–60 .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ New Vision Photography .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Paul Strand (1890–1976) .” (October 2004)

- Department of Photographs. “ Photojournalism and the Picture Press in Germany .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and American Photography

- Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography

- The New Documentary Tradition in Photography

- Paul Strand (1890–1976)

- Pictorialism in America

- Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography

- Early Photographers of the American West: 1860s–70s

- Édouard Baldus (1813–1889)

- Edward J. Steichen (1879–1973): The Photo-Secession Years

- Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884)

- Harry Burton (1879–1940): The Pharaoh’s Photographer

- Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004)

- The Industrialization of French Photography after 1860

- International Pictorialism

- Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

- New Vision Photography

- Photographers in Egypt

- Photography and Surrealism

- Photography and the Civil War, 1861–65

- Photography in Postwar America, 1945-60

- Photojournalism and the Picture Press in Germany

- The Structure of Photographic Metaphors

- Walker Evans (1903–1975)

- William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) and the Invention of Photography

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present

- 19th Century A.D.

- 20th Century A.D.

- Abstract Art

- American Art

- Architecture

- Conceptual Art

- Gelatin Silver Print

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- New Orleans

- North America

- Palladianism

- Parchment / Vellum

- Photography

- Photogravure

- Photojournalism

- Pictorialism

- Platinum Print

- Scandinavia

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Arbus, Diane

- Bellocq, E.J.

- Bravo, Manuel Alvarez

- Cézanne, Paul

- Duchamp, Marcel

- Ellis, William

- Evans, Walker

- Genthe, Arnold

- Hine, Lewis W.

- Laurent, Juan

- Mole, Arthur

- Picasso, Pablo

- Salzmann, Auguste

- Sheeler, Charles

- Steichen, Edward J.

- Stieglitz, Alfred

- Strand, Paul

- Thomas, John D.

Online Features

- Connections: “Smoke” by Ian Alteveer

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Photos Reveal Shocking Conditions of Tenement Slums in Late 1800s

By: Madison Horne

Updated: August 24, 2023 | Original: October 26, 2018

New immigrants to New York City in the late 1800s faced grim, cramped living conditions in tenement housing that once dominated the Lower East Side. During the 19th century, immigration steadily increased, causing New York City's population to double every decade from 1800 to 1880. To accommodate the city's rapid growth, every inch of the city's poor areas was used to provide quick and cheap housing options.

Houses that were once for single families were divided to pack in as many people as possible. Walls were erected to create extra rooms, floors were added, and housing spread into backyard areas. To keep up with the population increase, construction was done hastily and corners were cut. Tenement buildings were constructed with cheap materials, had little or no indoor plumbing and lacked proper ventilation. These cramped and often unsafe quarters left many vulnerable to rapidly spreading illnesses and disasters like fires.

By 1900, more than 80,000 tenements had been built and housed 2.3 million people, two-thirds of the total city population.

Jacob Riis , who immigrated to the United States in 1870, worked as a police reporter who focused largely on uncovering the conditions of these tenement slums. However, his leadership and legacy in social reform truly began when he started to use photography to reveal the dire conditions in the most densely populated city in America . His work appeared in books, newspapers and magazines and shed light on the atrocities of the city, leaving little to be ignored.

In 1890, Riis compiled his work into his own book titled, How the Other Half Lives. As he wrote , "every man’s experience ought to be worth something to the community from which he drew it, no matter what that experience may be.” The eye-opening images in the book caught the attention of then-Police Commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt . Riis' work would inspire Roosevelt and others to work to improve living conditions of poor immigrant neighborhoods.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

How the Other Half Lives

47 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Introduction

Chapters 1-2

Chapters 5-6

Chapters 11-13

Chapters 15-16

Chapters 17-19

Chapters 20-21

Chapters 22-25

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1890) is a photojournalistic account of New York City’s working class of the late 19th century and the tenements that housed them. Riis exposes the appalling and often inhumane conditions in and around the tenements. He attributes New York City’s squalor and degradation to sheer greed on the part of landlords who prioritize maximum profits over basic decency. More importantly, he documents these conditions with more than 40 visual supplements, nearly all of them photographs. These images contributed to the book’s success and helped pioneer a style of “muckraking” journalism in pursuit of social reform. Riis concludes that the landlords themselves could solve the tenement problem by adopting Christian principles in their treatment of tenants and settling for a reasonable return of 5-6% on their investment in tenement property.

Content Warning: The text uses antiquated language regarding race and other terms relating to women, people without houses, suicide, and sex work that are considered insensitive to modern audiences.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,650+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Riis opens with a brief introduction that highlights the book’s major themes. First, the appalling conditions facing those who are impoverished are The Consequences of Greed . Landlords have the ability to provide decent housing but instead have chosen to cram as many rent-paying families into as few spaces as possible. Second, Riis views the Tenements as Locus and Source of New York City’s Social Ills : alcoholism, disease, pauperism , and crime. Riis always distinguishes between what he defines as the “honest” impoverished and the criminals or unemployed people who think the world owes them a living, but he also believes that the lives of the former would improve, and the numbers of the latter would shrink if New Yorkers were to solve the housing problem. Finally, Riis argues for both The Urgency and Possibility of Reform . The tenements breed conditions so awful that it would hardly be surprising if they also bred angry hordes of social revolutionaries. Riis suggests, however, that the landlords still have the power to solve the problem by adopting a mixture of capitalist and Christian principles.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Early chapters describe the history of the tenements, recent reform efforts, and the ethnic mixture of current tenement communities. The tenement problem developed over a period of decades in response to massive surges in immigration. Rather than viewing these immigrants as human beings who required decent housing, most of New York’s landlords viewed them as an investment opportunity. In the second half of the 19th century, particularly after the Civil War, New Yorkers began to notice the tenement problem, and a few reform-minded individuals tried to address it. By then, however, the scope of the problem defied piecemeal remedies, legislative or otherwise. Riis, therefore, appeals to the landlords’ humanity as the best hope for improving the lives of their tenants.

To heighten New Yorkers’ sense of alarm over conditions in the tenements, Riis emphasizes the tenement communities’ ethnic or “racial” composition. In the very foreignness of the tenants themselves, native-born New Yorkers are meant to see possible danger to the social order. Riis seldom fails to express sympathy for the honest impoverished no matter their ethnic origins, but he is also a man of the late-19th century who shares that era’s assumptions about group identities, often categorized under the broad heading of “race.” Modern readers, therefore, should view Riis’s language regarding Chinese and Jewish immigrants in particular not as unique to Riis but as an artifact representing the time in which he lived.

Riis’s photojournalistic approach begins in Chapter 4 and continues through Chapter 22. Seventeen of these 19 chapters feature at least one and as many as four images, nearly all of them photographs. Riis takes the reader on a literary and visual tour of the tenements. He begins in downtown New York City, below 14th Street, on the southern part of Manhattan Island. Most of the city’s tenements, including nearly all of the worst ones, are located here, and the majority of these are found on the East Side. Some of these chapters focus on individual communities as defined by ethnicity or “race.” Examples of these—as well as the type of language Riis employs—include “The Italian in New York,” “Chinatown,” “Jewtown,” “The Sweaters of Jewtown,” “The Bohemians—Tenement-House Cigarmaking,” and “The Color Line in New York.” Other chapters highlight the tenements’ location, such as “The Down Town Back Alley” and “The Bend”—the latter a reference to the notorious Mulberry Street “Bend,’’ where conditions are so deplorable that the tenements are slated for demolition and set to be replaced by a public park. Riis also devotes three consecutive chapters to the youngest groups the tenements affect: “The Problem of the Children,” “Waifs of the City’s Slums,” and “The Street Arab .” “A Raid on the Stale-Beer Dives” and “The Cheap Lodging Houses” present a view at least partially drawn from the law-enforcement perspective . “The Reign of Rum,” “The Harvest of Tares,” “Pauperism in the Tenements,” and “The Working Girls of New York” cover alcoholism, crime, “beggary," and the plight of working women, respectively. The last of these often cannot support themselves without resorting to sex work. “The Common Herd” presents an overview of conditions in the tenements, and “The Wrecks and the Waste” describes those confined in prisons or psychiatric hospitals.

The book’s final three chapters return to the major themes. Riis warns that violence and justice are the only alternatives to serious, Christian-minded, business-driven reform. If landlords are determined to cling to their maximum-return-on-rent approach to housing the impoverished, then violence will be the result. Riis does not propose massive public expenditure, and he believes that misplaced charity has contributed to the problem. He suggests instead that landlords can adopt Christian principles and still make a reasonable profit of between 5 and 6% on investment. He even cites examples of landlords who have put these principles into practice with resounding success. Riis opens his final chapter with eight “bald facts” about the tenement problem, all of which reduce to the observation that New York’s wage-earners must have decent housing (282). If they do not get it, then not even the American system of government will save well-to-do New Yorkers from the wrath of those whom they have so long neglected.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

View Collection

Books on U.S. History

Journalism Reads

National Suicide Prevention Month

Poverty & Homelessness

Danish-American Photographer

Summary of Jacob Riis

Riis was one of America's first photojournalists. As a newspaper reporter, photographer, and social reformer, he rattled the conscience of Americans with his descriptions - pictorial and written - of New York's slum conditions. As an early pioneer of flashlamp photography, he was able to capture the squalid lives of immigrant families living on the very edges of society. His lectures and, subsequent books, including the famous How the Other Half Lives (1890), was so influential that they brought about new legislation to improve tenement housing conditions and general standards of sanitation across America. Riis's work is hailed now as the precursor to so-called "muckraking journalism" that became a fixture in American newspaper publications after 1900. His most glowing endorsement came from (the future US President) Theodore Roosevelt who referred to him as "the best American I ever knew [sic]" with "the great gift of making others see what he saw and feel what he felt".

Accomplishments

- With books such as, How the Other Half Lives (1890) and The Children of the Slums (1892), Riis created great public interest, and garnered widespread acclaim, that fueled several urban social reform programs. As a result, history sees him as both a forerunner for American Documentary Photography and Social Documentary Photography. When coupled with his statewide tours, where his lectures were accompanied by lanternslide displays of his photographs, Riis created a visual and written record that created a popular audience for the art form that was to become known as Photojournalism .

- After reading about the invention of magnesium flash powder, Riis was amongst the first to recognize the possibility of night photography. He began visiting the slums at night, where, accompanied by two assistants and a policeman, he sometimes startled the residents with the abrupt flash of his camera. Some have criticized Riis's methods as intrusive but his drive to capture the most honest, "unsuspecting", moments with his camera was driven by a mission to bring about reform in tenement housing and thus, for him, justifying his methods.

- Although Riis was a pioneer of (the ostensibly neutral) Documentary Photography , he allowed for an element of symbolism to enter his work through the motif of the seemingly mundane object of the clothesline. Initially viewed by him as a nuisance (that distracted from the picture he was trying to capture) he came to recognize it as symbolic of people who were struggling to live honest lives. Riis wrote: "The true line to be drawn between pauperism and honest poverty is the clothes−line. With it begins the effort to be clean that is the first and the best evidence of a desire to be honest".

- As Riis matured as a photographer, he learned to build a rapport with his subjects. This led to a series of portrait photographs, usually of slum children forced into manual labor. His images, of which he wrote, "the young are naturally neither vicious nor hardened, simply weak and undeveloped, except by the bad influences of the street, makes this duty all the more urgent as well as hopeful", were included in the book, The Children of the Poor (1892). The book proved so influential it moved the church and, even individual families, to take abandoned children into their direct care.

- In his latter images, Riis turned his attentions away from the human figure onto rows of tenement housing. For Riis, these houses, many constructed by unscrupulous builders, contributed to the early death of their occupants. Through his 1892 book, The Battle with the Slum , Riis highlighted the issue of poor sewage and water sanitation, that contributed to diseases such as typhoid. His maxim was: "It is squalid houses that makes squalid people".

The Life of Jacob Riis

Acknowledging the power of the photograph to swing public opinion, Riis wrote: "My writings did not make much of an impression - these things rarely do, put into mere words - but my negatives, still dripping from the dark-room, came to reinforce them".

Important Art by Jacob Riis

Bandits' Roost, 59 1/2 Mulberry Street

Eighteen of Riis's photographs first appeared in a photo essay called "How the Other Half Lives" in Scribner Magazine 's 1889 Christmas edition, one of which was Bandits' Roost . The iconic image shows a gang of Italian toughs, all sporting bowler caps, in a notoriously dangerous alley called The Bend, a neighborhood between Mulberry, Baxter, Bayard, and Park Streets in New York City. Riis said of The Bend, "Abuse is the normal condition...murder its everyday crop". Two men on the right seem to guard the entrance, as the shillala (club) that one man holds heightens the sense of menace. Behind them, another man casually perches on a staircase railing (perhaps he is in command of the gang) while three other figures cluster on the staircase on the other side, all of them turned toward Riis's camera. Meanwhile, a woman and a child lean out of windows in the building on the right, while in background, clothing hangs on lines strung along the alley. A sense of crowded poverty and desperate circumstances becomes the backdrop for Riis's emphasis on the criminal element (as echoed in his title). The lines of the buildings seem to almost converge in the background, a dead end that dissolves in light. The image displayed what living conditions were like in city tenement slums. In Riis's mind, however, photographs were secondary to his written texts and his spoken lectures on the topic of social welfare. Nevertheless, this image exemplified the way in which sites like Mulberry Bend were effectively training grounds for criminal behavior. He wrote: "Like the Chinese, the Italian is a born gambler. His soul is in the game from the moment the cards are on the table, and very frequently his knife is in it too before the game is ended. No Sunday has passed in New York since 'the Bend' became a suburb of Naples without one or more of these murderous affrays coming to the notice of the police". Through his images and words, Riis helped prompt the city to demolish Mulberry Bend and replace it with a park. (This iconic image was recreated almost identically in a scene from Martin Scorsese's film, Gangs of New York (2002), in which gang leader Amsterdam sells a corpse to medical students.)

Gelatin silver print - Museum of the City of New York

Lodgers in Bayard Street Tenement, 5 Cents a Spot

This photograph shows a tiny, overcrowded, dilapidated, dirty tenement lodging room packed with people and their belongings. Like many of his early photographs, it was taken when Riis accompanied the police on their nightly rounds and raids, where Riis was serving, in his own words, as "a kind of war correspondent". Using flash-bulb photography, Riis woke the drowsy residents suddenly with the bright light and gunshot-like boom of the flash powder. The sanitary police then moved in and raided the illegal lodging house (as city laws of the time required that the minimum cost for a bed, or "spot" be seven cents, but this abode was charging just five cents for floor spots). As Riis put it, "In a room not thirteen feet either way slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks set in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor. A kerosene lamp burned dimly in the fearful atmosphere, probably to guide other and later arrivals to their beds, for it was only just past midnight. A baby's fretful wail came from an adjoining hall-room, where, in the semi-darkness, three recumbent figures could be made out. The apartment was one of three in two adjoining buildings we had found, within half an hour, similarly crowded". Contemporary criticism has tended to denounce Riis's methods for "victimizing" his subjects, entering lodgings without permission, and startling them with his flash photography. However, his primary intent was to capture honest, candid moments and to advocate for reform in tenement housing. For Riis, the ends justified the means. As he stated, "the half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath". Startling images like this spurred city officials - including then-police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt - to pass laws that made squalid tenement housing safer and more sanitary.

Baxter St. Court

This photograph shows a small courtyard in a densely populated tenement housing project. Buckets, and a small wooden wagon cart lay on the ground, and two women and seven children sat at the edges of the courtyard looking at Riis's camera. The dingy, cramped scene underscores one of Riis' main messages: places like this are unsuitable for children to grow up in, without even a patch of grass to play upon. He once wrote: "that dismal alley with its bare brick walls, between which no sun ever rose or set, was the world of those children. It filled their young lives. Probably not one of them had been out of sight of it". He added that "Has a yard of turf been laid and a vine been coaxed to grow within their reach, they are banished and barred out from it as from a heaven that is not for such as they. I came upon a couple of youngsters in a Mulberry Street yard a while ago that were chalking on the fence their first lesson in 'writin'. And this is what they wrote: 'Keeb of te Grass.' They had it by heart, for there was not, I verily believe, a green sod within a quarter of a mile". His efforts culminated in the city creating more parks near slums. The clothesline in this and other images by Riis are of great symbolic importance. As he himself had lived in immigrant slums, tenement housing, and even the streets, upon his arrival in New York, Riis was intimate with the nuances of the living conditions for the poor and needy. When he later found himself in a better financial position and set out on his mission to document tenement housing and slums in New York through photography, he recalled an early encounter when he was attempting to photograph a tenement house and was initially annoyed at the way the clotheslines obstructed the view in the image. Soon, however, he recognized them as "evidence that someone was trying to keep clean" and wrote that "The true line to be drawn between pauperism and honest poverty is the clothes−line. With it begins the effort to be clean that is the first and the best evidence of a desire to be honest".

Gelatin silver print - International Center of Photography

The Potter's Field - The Common Trench

This image shows six workers in the process of burying dead tenement residents and homeless individuals in a trench in Potter's Field, a mass grave for the poor and the immigrants who had been forgotten by society. As he wrote, "even there they do not escape their fate. In the common trench of the Poor Burying Ground they lie packed three stories deep, shoulder to shoulder, crowded in death as they were in life, to 'save space;' for even on that desert island the ground is not for the exclusive possession of those who cannot afford to pay for it". In his writing and lectures, Riis not only appealed directly to his audience's sense of human dignity, but also introduced facts, figures, and images that were undeniably deplorable, such as the fact that the infant mortality rate in tenements was one in ten, and the fact that a full one-tenth of New York City's population would be buried (and forgotten) in the mass unmarked graves of Potter's Field. In 2018, anthropologists began unearthing the remains at Potter's Field. Manhattan council member Mark Levine stated that "Every one of those bones belongs to a human being, to a New Yorker. People who in many cases were marginalized and forgotten in life. They've been again marginalized and forgotten in their final resting place, and this disinterment is the ultimate indignity". Generations later, many still hope to find the remains of their lost grandparents and great-grandparents at the site. One of those descendants was Carol DiMedio who set out to trace the final resting place of her Italian immigrant grandfather. She learned from her mother, Annette Gallo, that when she was a ten-year-old girl, she received a letter from her brother (Carol's uncle) who, like her, had been placed in an orphanage (their mother having died giving birth) in which he wrote only "Last Wednesday morning something bad happened to papa". Carol and her mother made it their life-long quest to learn of their grandfather's fate. Yet, upon learning that he had been buried in "The Common Trench", Carol couldn't bear to bring her mother the awful truth: "I lied to her when I told her I found out where he was buried. I told her he is buried in the most beautiful place with trees and green grass surrounded by blue water with seagulls flying above. She cried when I told her. She needed that peace".

Chinatown Opium Joint

For this photograph, Riis entered a Chinatown opium den and captured two Asian individuals, one standing, only half visible, looking at the camera on the right-hand side, and the other laying down on a bed, looking off to the right, presumably in an opium-induced stupor. Images like this contributed to his philanthropic project but, coupled with his writings, it also points to racial prejudices and stereotypes that by modern standards appear very much outdated. Riis's most influential book, How the Other Half Lives , was in fact separated into chapters that focused on specified ethnic groups such as "The Italian in New York", "Chinatown", "Jewtown", and "The Bohemians". As curator Bonnie Yochelson notes, "That was a pre-established literary genre, which he was borrowing. It had a lot of entertainment value. 'Come see the colorful Italians and the mystifying Chinese'". For Riis, "the Jew" had a "low intellectual status" when compared to "the Italian" who "makes less trouble", the "contentious Irishman" or, the "order−loving German". Of the Chinese (for him a catch-all term at the time for anyone of "Oriental" or East Asian appearance) he wrote that "I state it in advance as my opinion, based on the steady observation of years, that all attempts to make an effective Christian of John Chinaman will remain abortive in this generation; of the next I have, if anything, less hope. Ages of senseless idolatry, a mere grub−worship, have left him without the essential qualities for appreciating the gentle teachings of a faith whose motive and unselfish spirit are alike beyond his grasp". The historian Daniel Czitrom stated that "One of the things that makes Riis so fascinating are these contradictions in his work. I see Riis more as a transitional figure. He's somebody that did bring with him those stereotypes and sort of racialized thinking of the day, but he's also somebody that began insisting on the importance of environment. Or, as he put it at one point, it's the squalid houses that make for squalid people". Czitrom concluded that, "I've always been struck by the tension between the empathy and sympathy that's powerfully depicted in many of those images, and the kind of stereotypes, racial language, that he uses in the text. There's a tension between the text and the photographs. Today, no one really reads Riis anymore, and yet the photographs remain incredibly moving".

Silver gelatin print - Museum of the City of New York

"I Scrubs" - Little Katie from the West 52nd Street Industrial School

After publishing How the Other Half Lives , Riis changed his approach, spending more time building a rapport with his subjects and learning of their life stories. He began taking portrait photographs, often of children who lived and worked in New York's slums. Pictured here is eight-year-old Katie, who took on the motherly duties of caring for her four siblings who worked in a hammock factory (their mother had passed away and their father had taken off with another woman). Katie also attended one of the twenty-one industrial schools established by the Children's Aid Society between 1854 and 1874. The Society was established in order to offer academic and technical training, medical care, and recreational programming to children who, due to their level of poverty, could not attend regular state schools. The image and an accompanying text were included in Riis 1892 book The Children of the Poor . Riis wrote about his encounter with Katie, "This picture shows what a sober, patient, sturdy little thing she was, with that dull life wearing on her day by day [...] She got right up when asked and stood for her picture without a question and without a smile. 'What kind of work do you do?' I asked, thinking to interest her while I made ready. 'I scrubs,' she replied, promptly, and her look guaranteed that what she scrubbed came out clean". The Children of the Poor was produced by Riis with the aim of highlighting the plight of poor and immigrant children, and recommendations on how their situation could be ameliorated. With the support of the Health Department, Riis filled the book with statistical information on public health, child labor, infant mortality rates, access to education, and crime. At the same time, the photographs and stories were more finely detailed and the book moved many to action, including churches and families who fostered children that had been abandoned at foundling hospitals. Wrote Riis: "Nothing is now better understood than that the rescue of the children is the key to the problem of city poverty, as presented for our solution today; that character may be formed where to reform it would be a hopeless task. The concurrent testimony of all who have to undertake it at a later stage: that the young are naturally neither vicious nor hardened, simply weak and undeveloped, except by the bad influences of the street, makes this duty all the more urgent as well as hopeful".

Dens of Death

There is no human presence in this image. The housing looks utterly unfit for human inhabitance (or even to pass through). We see a series of shanty homes running along Baxter Street, all of which look like they could collapse in on themselves at any moment. This photograph appeared in Riis's 1892 book The Battle with the Slum , which he proposed as a sequel to How the Other Half Lives (1890). The former expanded upon the same topics as the latter but with most of Riis's photographs focused solely on the dilapidated buildings themselves. Riis wrote of these inadequate excuses for housing: "They had been built only a little while when complaint came to the Board of Health of smells in the houses. A sanitary inspector was sent to find the cause. He followed the smell down in the cellar and, digging there, discovered that the waste pipe was a blind. It had simply been run three feet into the ground and was not connected with the sewer. The houses were built to sell. That they killed the tenants was no concern of builder's. His name, by the way, was Buddensiek. A dozen years after, when it happened that a row of tenements he was building fell down ahead of time, before they were finished and sold, and killed the workmen, he was arrested and sent to Sing Sing [prison] for ten years, for manslaughter". Riis also drew attention the wave of typhoid that was caused by contaminated water and which swept through these residences at an alarming rate. It was no doubt a subject close to Riis's heart since he had lost several siblings to poor sanitation in his own childhood in Ribe, Denmark.

materials - Museum of the City of New York

Biography of Jacob Riis

Childhood and education.

Born in the small and poor town of Ribe on Denmark's south-west Jutland, Jacob A. Riis was the third of fourteen children born to schoolmaster and journalist Niels Edward Riis and homemaker Carolina Riis (née Bendsine Lundholm). Several of Jacob's siblings died in early childhood from disease due to unclean drinking water and tuberculosis (in fact Jacob was one of only four Riis siblings to pass the age of twenty), yet despite these tragedies, Jacob recalled a happy childhood. Niels Riis encouraged his son to learn English by reading Charles Dickens and James Fenimore Cooper. Niels had hoped that Jacob might become a writer, but the boy aspired to be a carpenter and on leaving school took up an apprentice with a local carpentry company.

Still aged just sixteen, Riis fell in love with Elisabeth Gjørtz, the twelve-year-old daughter of the owner of the carpentry company. Elizabeth's father showed his disapproval by sending Riis to Copenhagen where he completed his apprenticeship. In 1868, Riis returned to Ribe but found a shortage of work and thus decided (like roughly one third of Denmark's population in the mid-nineteenth century) to emigrate to the United States. Upon his arrival in New York, on June 5, 1870, the twenty-one-year-old Riis's worldly possessions amounted to $40 (gifted by friends), letters of introduction to the Danish Consul, and a locket containing a strand of Gjørtz's hair (which had been given to him by the girl's mother).

On his first day in New York, an anxious Riis spent half of his money on a revolver for the purposes of self-defense. By day five, he was penniless and took on work as a carpenter at Brady's Bend Iron Works on the Allegheny River. He was employed there for only a few days before switching to work as a miner (as it paid more). However, Riis found the conditions in the mine so miserable he soon returned to Brady's.

On July 19, 1870, Riis learned that France had declared war on Germany and decided he wanted to return to Europe and join the French army. However, the French Consulate informed him that they had no plans to send a volunteer army from the US. Despondent. A downhearted Riis pawned his revolver and walked until he collapsed from exhaustion at Fordham College, where a Catholic priest took him in and gave him a bed and a meal. He then carried on his trek to Mount Vernon where he worked odd jobs on farms. He read in the New York Sun that soldiers were in fact being recruited for the war, and returned to New York City to enlist, but his application was refused.

Riis spent several months living destitute, scavenging food, and sleeping out-of-doors or in the rancid-smelling police lodging-house where his cherished locket was stolen from him while he slept. His only companion for a time was a stray dog. For a six-week period he worked at a brickyard in New Jersey, before returning to New York to try, again unsuccessfully, to enlist. Completely disillusioned with New York, he made his way to Philadelphia by working odd jobs to purchase passage on ferries, and sometimes even stowing away on freight trains.

Once he arrived in Philadelphia, Riis reached out to the Danish consul Ferdinand Myhlertz and his wife, who took Riis in and cared for him for two weeks. Riis then found work as a carpenter (among other jobs) in Scandinavian communities in Southern Pennsylvania. Having achieved a modest level of financial stability, he found enough time to try his hand at writing. He tried, unsuccessfully, to get a job at a newspaper in Buffalo, and was also rejected by several magazines. In the following months, he moved between New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh, often being exploited and cheated by employers and associates. While bedridden with a fever in Pittsburgh, he received the heartbreaking news from home that his beloved Elisabeth was engaged to a cavalry officer.

Early Career

Back in New York once more, Riis successfully applied for the post of city editor for a Long Island newspaper. However, he soon discovered that the editor-in-chief was a dishonest and difficult man and left the position after only two weeks. His luck changed, however, when he gained employment as a trainee at the New York News Association. He wrote passionately about the immigrant communities he had lived amongst, and did his job so well, Riis was soon promoted to the role of editor of a political periodical.

That publication went bankrupt around the same time that Riis received word from home that his older brothers, his aunt, and Elisabeth Gjørtz's fiancé, had all died. He wrote to Elisabeth asking for her hand in marriage, and then, using his $75 of savings and promissory notes, purchased the defunct newspaper. He quickly found success - using the publication to defame his former employers, most of whom now held political positions - and was able to pay off his debts.

Riis received a response from Elisabeth who asked him to come to Denmark so they could discuss his proposal; "We will strive together for all that is noble and good", she wrote. Around the same time, the politicians whose reputations had suffered through Riis's pen, purchased his company at five times the price he had paid for it. He arrived in Denmark, finally in a position of financial security, and married his beloved Elisabeth. The couple moved back to New York a few months after the wedding, and Riis began working as editor of The Brooklyn News .

Riis first used the "magic lantern" projector (that projected images onto sheets or screens) to advertise his newspaper. Riis took his "magic lantern" advertisements around the states of New York and Pennsylvania but returned to New York City following an altercation with a group of policemen, and a group of railroad workers on strike. Riis's neighbor, who was city editor of the New York Tribune , then recommended him for a position there. In 1873 he took up the position of police reporter, stationed in a press office across from the police headquarters on Mulberry Street - a criminal slum area known locally as "Death's Thoroughfare".

Mature Period

Inspired by the progressive social reform movements that had initially emerged in the mid-1800s (including Felix Adler's Society for Ethical Culture), Riis strengthened his resolve to use his position to not only report on crime and its links to poverty, but also to try to affect social change. He decided the best way to achieve this was through a combination of the written word and images. Having no talent for drawing, he taught himself the new art of photography. At the time, photographic processes made it difficult to capture images under poor lighting conditions. But in 1887, Riis learned about a new method of "flash" photography, developed in Germany by Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke. They had used a mixture of magnesium, potassium chlorate, and antimony sulfide, to create a flash of light at the moment of exposure.

Riis soon introduced this method to fellow photographers Dr. John Nagle (who was also chief of the Bureau of Vital Statistics in the City Health Department), Henry Piffard, and Richard Hoe Lawrence. The four men essentially pioneered the use of flash photography in the US by documenting the "dark" conditions in New York's slums. They first published their findings anonymously in the New York Sun on February 12, 1888 in an article accompanied by twelve sketches based on the men's photographs.

Riis and his friends gradually modified the flash system, but it was an exhausting process, and Riis soon found himself working alone. In January 1888 he purchased a 4x5 box camera, plate holders, a tripod, and other equipment for developing and printing his images. He spent the next three years photographing New York's tenements and slums at night, capturing the hardships faced by criminals, immigrants, and the poor and destitute. He began to amass an archive of his own works, along with photographs by other "muckraking" photographers (that is, photographers who sought to expose unjust conditions with the goal of bringing about social reform).

Riis submitted his photographs, accompanied by essays, to various magazines, but was met with constant rejection. When Harper's New Monthly Magazine said they liked his photos but not his writing, Riis decided instead to get his message across through public speaking and projecting images through his "magic lantern". Churches appeared to be the ideal venue, but many declined to host him for fear of offending their congregations' sensibilities. Eventually, Riis received sponsorship from Adolph Schauffler of the City Mission Society, Health Department clerk W. L. Craig, and clergyman and writer Josiah Strong, to speak at the Broadway Tabernacle Church. The lectures - illustrated by Riis's images - were a great success and encouraged others to take up his cause. These included the social reformer, Charles Henry Parkhurst, editor at Scribner's Magazine . Scribner's published an eighteen-page article, featuring nineteen illustrations based on Riis's photographs, in its 1889 Christmas edition.

In his writings and lectures, Riis not only outlined in detail the history of the troubling social situation - the development of the tenement housing system in order to "house" the massive influx of foreign immigrants at the time, the negative effects this approach had, and the efforts of the Sanitation Department to investigate and address these issues - but also presented hard facts and figures. Riis also penned distressing stories of individuals and families who struggled to survive within this system, such as the "case of a hard−working family of man and wife, young people from the old country, who took poison together in a Crosby Street tenement because they were tired".

Late Period

In 1890, Riis published his most popular and influential book, How the Other Half Lives , which expanded upon the article published in Scribner's Magazine , and which opened by informing the reader that the story presented therein "is dark enough, drawn from the plain public records, to send a chill to any heart". The book included the illustrations he had used in the article, as well as seventeen photographic reproductions using the halftone reprographic method, making it one of the first books ever to do so. The book was generally well-received and complimented similarly themed works including the Salvation Army treatise, In Darkest England, and the Way Out (1890) by William Booth, and Ward McAllister's book of New York memoirs, Society as I Have Found It (1890).

He also became actively involved at this time in an organization that would become known in the future as the Riis Settlement House. As Denmark's Riis Museum describes: "Strongly influenced by the work of the settlement house pioneers in New York, Riis collaborated with the King's Daughters, an organization of Episcopalian church women, to establish the King's Daughters Settlement House in 1890. Originally housed on 48 Henry Street in the Lower East Side, the settlement house offered sewing classes, mothers clubs, health care, summer camp and a penny provident bank".

Meanwhile, How the Other Half Lives helped to prompt changes in New York legislation that led to improved conditions for immigrants and the poor. As curator and art historian Lisa Hostetler notes, not only was Riis "a pioneer in the use of photography as an agent of social reform, he was also among the first to use flash powder to photograph interior views [...] At a time when the poor were usually portrayed in sentimental genre scenes, Riis often shocked his audience by revealing the horrifying details of real life in poverty-stricken environments. His sympathetic portrayal of his subjects emphasized their humanity and bravery amid deplorable conditions and encouraged a more sensitive attitude towards the poor in this country".

How the Other Half Lives also served as a model for the next generation of muckraking journalists in the early 1900s. Writer and Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who would become US President a decade later, read Riis's book and wrote to him saying: "I have come to help". The two became friends, and Riis led Roosevelt around the streets of New York to show him first-hand the abysmal living conditions he was trying to reform. Roosevelt duly closed the most deprived of the city's police lodging facilities. They also found that during nighttime, nine out of ten patrolmen were not present for their work, leading to reform in policework itself. Roosevelt later referred to (the Dane) Riis as "the best American I ever knew [and] the most useful citizen of New York".

Next, Riis turned his attention toward the condition of New York's drinking water, publishing "Some Things We Drink" (along with six photographs) in the New York Evening Sun on August 21, 1891. He explained "I took my camera and went up in the watershed photographing my evidence wherever I found it. Populous towns sewered directly into our drinking water. I went to the doctors and asked how many days a vigorous cholera bacillus may live and multiply in running water. About seven, said they. My case was made". This, and further articles he wrote on the topic, prompted the city to purchase the area around the New Croton Reservoir and to take steps to avoid a devastating cholera outbreak. His work also prompted the passing of the Small Park Act in 1887, a law that permitted the city to purchase small parks in crowded neighborhoods.

In the late 1890s, Riis used his writing and photographs to call attention to, and enact change regarding, unsafe tenements, classism, and a range of other social and public health and safety causes. His children (daughter Clara, and sons John, Edward, and Roger) all followed their father's lead, working as activists in the name of their father's causes. Riis was now famous enough to publish an autobiography, The Making of an American , in 1901. Also in that year, as the Riis Museum describes, "the King's Daughters Settlement House was renamed the Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement House (Riis Settlement) in honor of its founder and broadened the scope of activities to include athletics, citizenship classes, and drama".

Sadly in 1905, Riis's wife passed away. The New York Public Library (which houses the Riis archive) records that "Letters Riis received in 1905 relate for the most part to the illness and subsequent death of his first wife, Elisabeth Nielson. Elisabeth had become well known to the American public after the publication of The Making of an American in which she played an important role. The letters and notes of sympathy include many from people who did not know Riis personally, as well as those from prominent persons, including several cablegrams from Theodore Roosevelt".

Riis remarried Mary Phillips two years later. The couple moved to a farm in Barre, Massachusetts shortly after their wedding, and remained there until Riis passed on May 26, 1914. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Riverside Cemetery in Barre. Mary carried on her late husband's mission, becoming, amongst other things, a board member of the Jacob A. Riis Settlement House.

After his death, Riis's photographs were essentially "lost" since he had not considered them to be of much merit in their own right. He did not considered himself a photographer but saw his photographs rather as visual aids that supplemented his articles and public lectures. Only decades later were over 700 negatives and slides found by his son in the attic of Riis's old home in Richmond Hill. He donated these to the photographer Alexander Alland who brought them to the attention of the Museum of the City of New York under whose curatorship their significance to social history was fully realized.