How to Write a Survey Introduction [+Examples]

Published: August 25, 2021

Writing a survey introduction probably isn't something you think about very often. That is until you're looking at the first screen of your almost finalized survey thinking "I should put something here. But what?"

While a potentially overlooked piece of the survey creation process, a good survey introduction is critical to improving survey completion rates and ensuring that the responses you receive are accurate. Taking the time to think about what information to include in your introduction can have a big impact on the success of your survey.

![introduction in research survey → Free Download: 5 Customer Survey Templates [Access Now]](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/53/9d36416b-3b0d-470c-a707-269296bb8683.png)

What is a Survey Introduction?

A survey introduction is the block of text that precedes the questions of your survey. It might be included at the top of an email requesting feedback or be the first slide in a series of questions. The survey introduction serves to set the stage for what the survey is, why the recipient should take the time to complete it, and what you're going to do with the information you collect. It should be compelling, informative, and reassuring.

.webp)

5 Free Customer Satisfaction Survey Templates

Easily measure customer satisfaction and begin to improve your customer experience.

- Net Promoter Score

- Customer Effort Score

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

How to Write a Survey Introduction

Start by thinking about the purpose of this survey. Who will be taking the survey? What information do you need for the project to be successful? Distill this information down into a sentence or two for your audience. Some examples may include:

- We're looking for feedback on our new product line for men.

- Tell us about your recent customer service experience.

- We're revamping our spring menu! What do you want for dinner?

Secondly, follow up with any logistical information they need to know about the survey. How many questions is it? When does the survey end? Who should they contact if they have additional questions? This might sound something like:

- This 5 question survey will take around 10 minutes to complete.

- Click below to access the short, two-question survey. For further information or feedback, please contact our support team at [email protected].

- This survey will be open until April 24th, 2022. Please take 5 minutes to provide your feedback before that time.

Finally, reassure the survey participants that their data is safe, and offer any information about how the survey data will be used:

- Your answers are anonymous and will be used to improve our future customer service strategy.

- Responses will be anonymized and analyzed for our upcoming report on consumer perception of insurance companies in the US. Please leave your email address if you'd like to receive a copy of the finished report.

- We read every response to our customer happiness surveys, and follow-up to make sure you're left with a positive experience.

No matter what you include in your survey introduction, make sure to keep it concise and as short as possible. Too long, and you risk readers dropping off and not completing your survey. It's also important to keep your survey messaging on-brand. If you typically use a brand voice that's quite corporate, switching to a conversational tone in your survey introduction will feel out of place. It might even make some readers question if the survey is truly coming from your company - causing distrust in its authenticity.

Finally, thank your respondents for their time. Even if their responses are negative, the fact that they're engaging with your survey is a great indicator of their loyalty . Customers will not take the time to provide feedback to companies they don't care about. Here are some phrases you can use to show your appreciation:

- This feedback is very helpful for our team in developing new features. Thank you so much for taking the time to complete this survey.

- We read every comment you leave on these surveys, so thank you for your feedback!

- We truly appreciate your insight and your time.

Want to make sure you've got it all covered? Save this checklist of the most important aspects to include in the survey introduction:

- How long will it take? (Minutes or number of questions)

- Why are you doing this survey?

- Why should they fill it out? Is there a giveaway for respondents (such as a draw for a $50 Amazon card) or another incentive to complete it?

- What are you going to do with the results? Are they anonymous?

- When does the survey close? What is the overall timeline?

- Are there any definitions or things they need to know before filling out the survey?

- Where should they go if they have questions or more feedback?

- Thank your participants for their time and feedback.

- Any additional information they need to fill out the survey with good, accurate data

Good Survey Introduction Examples

These survey introductions hit all the right notes. Read on for inspiration and additional tricks on how to write your own!

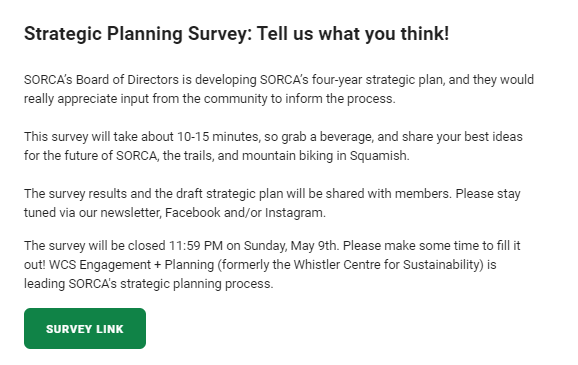

1. Squamish Off-Road Cycling Association (SORCA)

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

Nonresponse Bias: What to Avoid When Creating Surveys

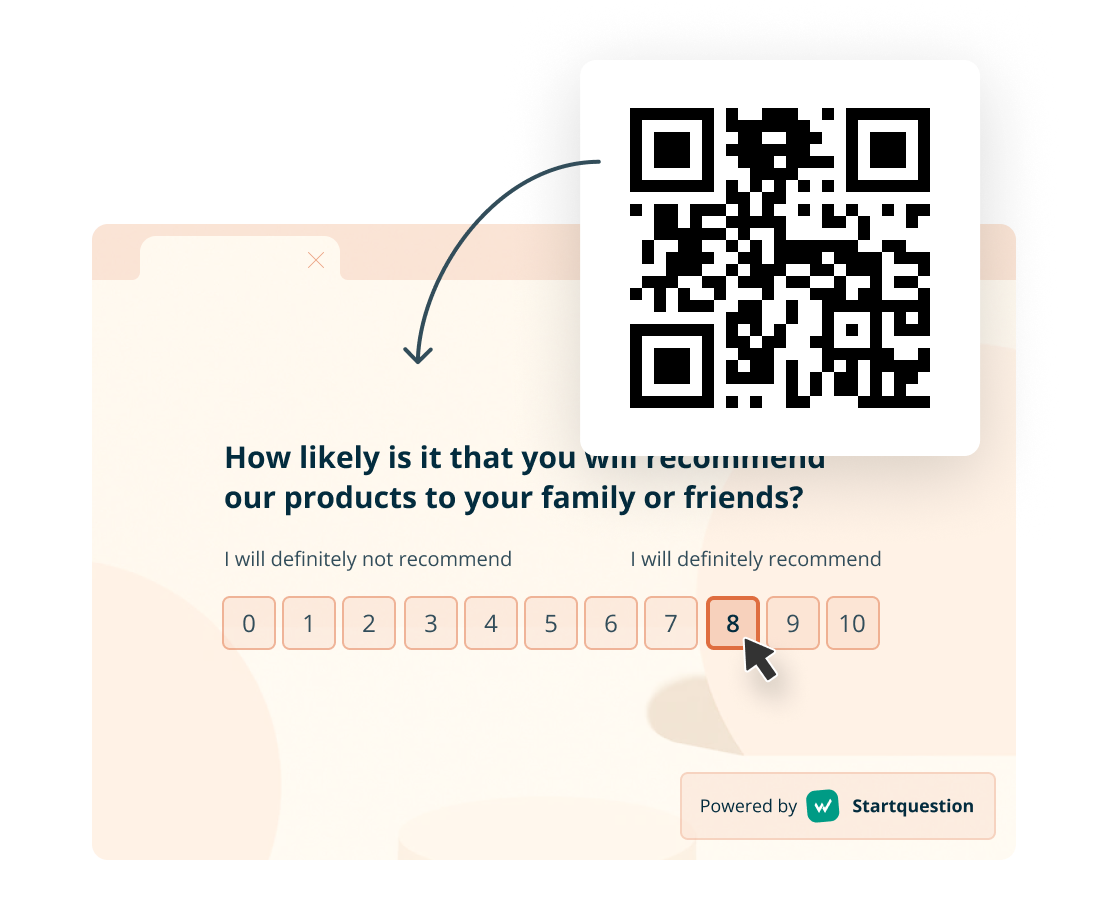

How to Make a Survey with a QR Code

50 Catchy Referral Slogans & How to Write Your Own

![introduction in research survey How Automated Phone Surveys Work [+Tips and Examples]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/phone-survey.webp)

How Automated Phone Surveys Work [+Tips and Examples]

Online Panels: What They Are & How to Use Them Effectively

The Complete Guide to Survey Logic (+Expert Tips)

Focus Group vs. Survey: Which One Should You Use?

![introduction in research survey Leading Questions: What They Are & Why They Matter [+ Examples]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/leading-questions-hero.webp)

Leading Questions: What They Are & Why They Matter [+ Examples]

What are Survey Sample Sizes & How to Find Your Sample Size

28 Questionnaire Examples, Questions, & Templates to Survey Your Clients

5 free templates for learning more about your customers and respondents.

Service Hub provides everything you need to delight and retain customers while supporting the success of your whole front office

- Survey & Questionnaire Introduction: Examples + [5 Types]

Whether online or offline, you need to politely approach survey respondents and get them excited to fill your questionnaire when carrying out a research survey. Therefore, before going into the questions you want to ask, you need to kickstart your data collection process with a compelling survey or questionnaire introduction.

Generally, only a few people would even listen to you if you shoved your survey in their faces without a simple introduction first. Survey introductions in online questionnaires help you prepare the minds of your respondents ahead of time and gather the best responses.

What is a Survey Introduction?

A survey introduction is a concise description with relevant information about a survey. It is the first part of the survey that prospective respondents interact with and it helps them decide whether to fill your questionnaire or not.

Think of survey introductions as abstracts that communicate the entire essence of the data collection process. Without a good abstract, your thesis gets delayed or unapproved.

Following through with this thought means that the more exciting your survey introduction is, the higher your chances of collecting the right number of quality survey responses.

Features of a Survey Introduction

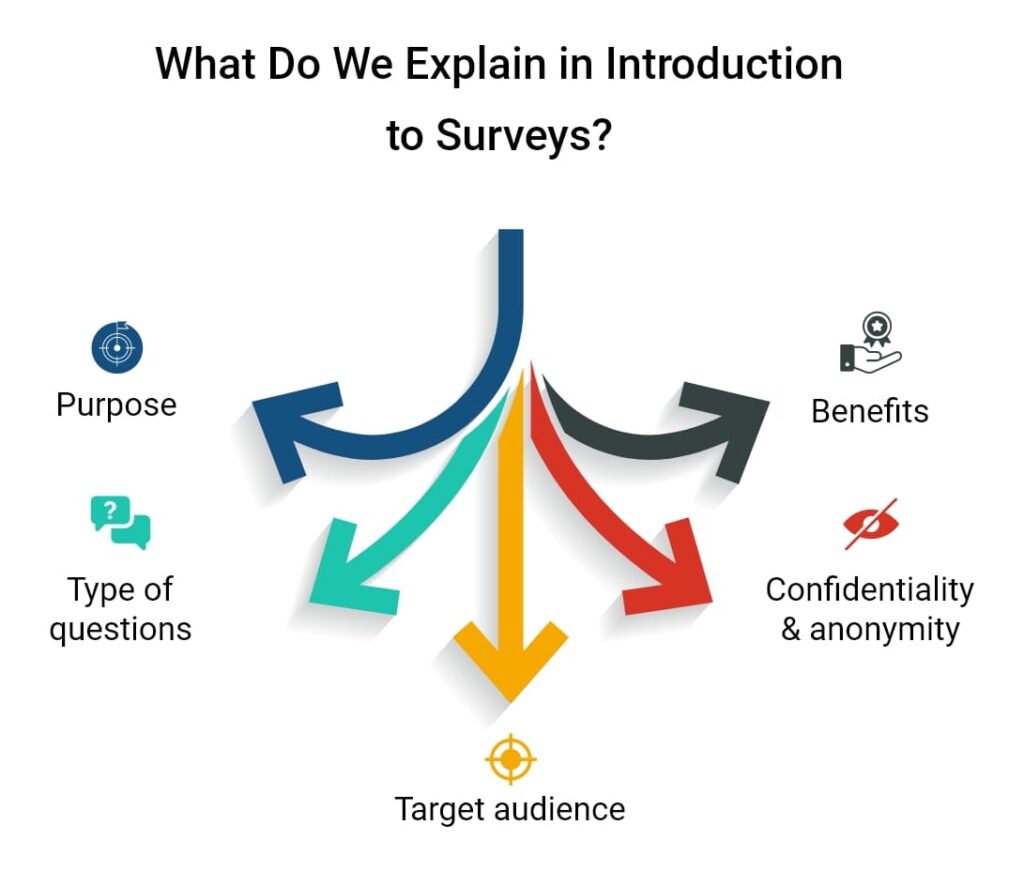

A good survey introduction must answer these 5 questions:

- Who is conducting the survey?

Here, you should include the name of the person or organization that is carrying out the research.

- What is the research about?

Survey respondents need to understand the aims and objectives of your research. This shows them why your survey is important and why they need to be part of it.

- How long will the survey take?

Prepare their minds ahead of time by adding an estimated survey-completion time. While shorter surveys are likely to have more respondents, don’t give a false estimation to bait people to fill your survey.

- Is my data safe?

Data privacy and protection is a huge concern for everyone. Since you plan to collect data from respondents, you need to tell them how you will use this information. You can include a link to your company’s privacy policy.

- How will I fill the survey?

Include instructions on how to fill the survey. Include information about relevant documents for the survey too.

Your survey should be written in simple language your audience understands. It should be friendly, human and show the respondents how much impact they’ll make by taking part in the survey. Always include a nice “thank you” note in your survey introduction.

Types of Survey Introduction

Market survey introduction.

If you’re conducting market research using a survey , then you need a market survey introduction. To get more information about your customers/ target market, you need to conduct a market research survey. A market survey introduction gives your target audience a clear picture of what you want to achieve and how their participation is an important part of it.

Market research serves multiple purposes—sometimes, it is all about getting real-time data to inform product launches. Other times, it is for business expansion or product improvement. With a market survey introduction, you can get your audience on the same page and let them know the exact information you need from them.

A market survey introduction should answer all the questions we looked at when we discussed the features of a survey introduction. After naming your organization, you should also introduce your product or product idea for brand awareness.

Because of the type of information, market surveys are longer than other types of surveys ; sometimes, they have multiple sections. So, in your market survey introduction, give respondents a heads-up and let them know completing your survey will take more time than the average. You can add a nice reward they can claim after filling the survey.

Example of Market Survey Introduction

At Formplus, we are working to improve online data collection for you. We’d really like to know what you feel about online data gathering tools . Take this 20-minute survey and win a free 1-month Formplus premium subscription. Your data will be collected anonymously and only used for this research. Thank You!

Student Survey Introduction

A student survey is a method of sampling students’ opinions about the school, teachers, and overall learning experiences. From measuring student satisfaction to evaluating courses, student surveys help you to make the right changes to your school.

A student survey introduction is the first step in getting the best responses from your students. Encourage students to provide objective feedback and let them know how the information will be used.

In the survey introduction, indicate that all responses will be recorded anonymously. Students need to be sure that they can provide honest feedback in the survey without getting harassed or victimized.

Example of Student Survey Introduction

Thank you for being one of our students at Salthill College. Please complete this short 3-minutes survey to let us know how satisfied you are with your overall student experience at our college. All responses are recorded anonymously so feel free to provide honest feedback. Your responses will help us improve our teaching and learning environment.

Research Questionnaire Introduction

You need a good research questionnaire introduction during the data-collection phase of your research. People are more likely to fill your questionnaire when they clearly understand what you want to achieve and why your research is important.

In the research questionnaire introduction, you can include facts, data, or statistics about the research problem. Then, show how the data collected via the questionnaire will contribute to solving the problem. The introduction should also address data privacy, data protection, and participant’s consent.

Even if you plan to share the questionnaire physically, a good research questionnaire introduction will help collect responses faster and save time.

Example of Research Questionnaire Introduction

Hello, I am a postgraduate researcher at the London School of Tropical Medicine. I am conducting a study on effective treatment options for communicable diseases in West Africa and I would like to know your experiences with the signs, symptoms, and treatment of communicable diseases. Please complete this 30-minute survey. Your responses are anonymous and you can skip any questions you are not comfortable with. Thank you for your participation.

Customer Satisfaction Survey Introduction

Your customer satisfaction survey introduction should communicate 2 things—appreciation and brevity. First, you should let your customers know how much you love their patronage. Next, tell them that the survey will take just a few minutes.

Throw in an honorary mention of your brand and then, go through some of the information you’ll need from them in the survey. To increase response rates, you can reward respondents with a gift, discount, or special offer.

Example of Customer Satisfaction Survey Introduction

Thank you for shopping at Wreaths and Flowers! We’ll like to ask you a few questions about your shopping experience. Your responses will help us make shopping more enjoyable for you. This will only take 1 minute and you get 30% off your next order when you complete the survey!

Importance of Survey Introduction

- It outlines the most important information about your survey

People need to know what they are getting into before filling your survey or questionnaire, and that’s exactly why you need a great survey introduction.

- It’s a great way to welcome respondents

You wouldn’t just walk up to someone to ask for something without a proper introduction so why would you want to do this with your survey or questionnaire ? A questionnaire welcome page sets the mood for requesting responses from your respondents.

- Quality survey introductions help you gain respondents’ trust

Many people are not excited about filling surveys and questionnaires, which is why they need a push. A survey or questionnaire introduction helps respondents to trust you and heightens their interest in filling your survey.

A survey introduction answers all the questions participants may have about the questionnaire. Think of it as some sort of FAQs that allows respondents to have a full grasp of your data collection process.

A questionnaire welcome page boosts survey participation and reduces survey dropout rates.

It helps survey participants to feel like an important part of the overall data gathering process. Survey introductions show participants that you value their opinions.

Survey introductions build the participants’ interest in your survey or questionnaire.

Why Use Formplus to Create Surveys?

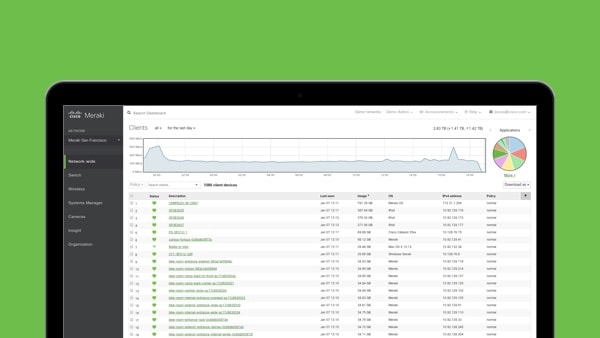

- Pre and Post Submission Page

Formplus allows you to add exciting survey introductions to your questionnaire. On the form’s intro page, you can provide a brief description of your survey, information on data privacy, and any other thing they need to know before filling the form.

You can also customize the form’s post-submission page and include a nice “thank you” note for respondents after they complete the survey or questionnaire. Learn more about our intro and post-submission pages here:

- Intuitive Easy to Use Survey Maker

The Formplus builder is easy to use and you can build surveys and questionnaires from scratch in no time without writing a single line of code. It has a drag-and-drop feature that allows you to add more than 30 different fields to your form seamlessly.

- Conditional Logic

Survey participants do not have to see or fill out all the fields in your form. With conditional logic, you can show or hide form fields and pages based on answers provided by respondents. This means survey respondents only have to fill the fields that are relevant to them.

Conditional logic helps you collect the right type of information from different survey participants. This way, you can avoid extra clutter and collect as much data as you want.

- Offline Surveys

Formplus supports offline data collection and this means you can collect data in areas with poor or no internet access. Survey participants can fill and submit your questionnaire when they are offline. The data they provide will be automatically synced with our servers or your preferred cloud storage when internet access is restored.

- Customized Surveys and Questionnaires

Formplus allows you to create beautiful and unique surveys with zero design experience. With the flexible design options, you can change the questionnaire’s background, colors, fonts, and create visually appealing designs. You can also add images and your organization’s logo.

- Share Forms Easily

With multiple form-sharing options, you can send out your survey and collect responses in many ways. Apart from adding your questionnaire to your website, you can also share it using the social media direct sharing buttons and via email invitations.

- Google Sheets Integration

With Google sheets integration, you can automatically update form responses in your spreadsheet and keep all form collaborators up to date. This makes it easy for you to import and export data, and collaborate with multiple people at the same time.

- Custom Subdomain

Sharing your questionnaire via a custom subdomain adds an air of professionalism to your overall data collection process. When creating your custom URL, you can include the name of your organization as a means of promoting your brand.

Custom subdomains are simple and easy to remember too. Hosting your survey on a custom subdomain also serves as an extra layer of security; especially when you share the link via email.

- Autoresponder Emails

After receiving a new response to your questionnaire, you can send out an automated automatic confirmation email to the survey participant in the form of autoresponder messages. In your autoresponder email, you should include a thank you message and any links to special offers and rewards.

- Mobile-Friendly Forms

Many people fill out surveys and questionnaires on their mobile devices and this is why all Formplus forms are mobile-friendly. Participants can complete the survey right on their mobile devices without having to bother about pinching out or zooming in on your form. Formplus forms can be viewed and filled out on any smartphone, tablet, or internet-enabled mobile device.

In this article, we’ve looked at different survey introductions for different types of questionnaires and surveys including customer satisfaction surveys and research questionnaires. Whether you are collecting data online or offline, the right survey introduction will boost participants’ interest in completing your survey.

With Formplus, you can add unique survey introductions to your form before sharing it with respondents. On the post-submission page, you can include a beautiful “thank you” note for respondents who complete your survey. Try out the pre and post-submission page option as well as other exciting features when you sign up for a free Formplus account.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- accuracy surveys

- age survey questions

- brand survey examples

- compatibility questionnaires

- survey methods

- survey question types

- survey questionnaire

- survey research

- survey types

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

33 Event Survey Questions + [Template Examples]

Read this article to learn how to create an event survey with Formplus

25 Training Survey Questions + Free Form Templates

Asking the right training survey questions before, during, and after a training session is an effective way to gather valuabl

Survey Methods: Definition, Types, and Examples

Data gathering is a flexible and exciting process; especially when you use surveys. There are different survey methods that a

Pilot Survey: Definition, Importance + [ Question Examples]

Before launching a new product or feature into the market, it is a good idea to find out what you

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

How to write a survey introduction that will inspire people to participate

- 11 min read

What is a survey introduction—and what is its purpose?

1. the importance of a compelling introduction, 2. understand the audience, 3. personalization, 4. clear and concise language, 5. survey timing, 6. incentives and rewards, 7. privacy and data security, 8. contact information, 9. testing and feedback, 10. adapting to different survey types, 11. visual appeal, 12. a/b testing, 13. follow-up surveys, 14. compliance with ethical guidelines, 15. analyzing introduction performance, 16. continuous improvement, survey introduction example: a template for any type of research, introduction to a customer satisfaction survey, introduction to a market survey, student survey introduction sample, introduction to an employee survey, introduction for a research paper survey, introduction to a survey report, additional tips for creating the best survey introduction.

Creating a good introduction for a survey is a crucial part of successful research. Its quality will greatly impact the process. It will improve the end result, including survey completion rates and response accuracy.

A questionnaire introduction provides the chance to introduce yourself and the topic being explored to respondents. It is also a chance to assure them that their personal information will be kept safe and explain how they will benefit from completing the survey.

This article explores how to write a survey introduction, discusses its importance, and provides valuable, ready-to-use questionnaire introduction examples.

A questionnaire introduction is a short body of text appearing on the user’s screen at the beginning of a survey. It is the first contact point between you and potential participants prior to respondents seeing any of the survey questions .

This block of text sets up the level of cooperation that will be forthcoming from the person reading it. You need to convince them to participate by providing valuable information about the survey.

This includes the research topic, the expected time it will take to complete the survey, how responses will be processed, and why it’s in someone’s interest to take the time to complete it. The survey introduction can be in the body of an email or on the first slide of the survey.

Based on the introduction, potential respondents will decide whether to participate in the survey. It is an overall description of the survey, the equivalent of the abstract in a dissertation or other research paper.

How to write survey introduction text well

After spending days or even months making the perfect survey , you probably know it like the palm of your hand. However, it’s important to take time to better understand a respondent’s initial reaction to it—they may not be familiar with the topic at all.

As with every stage of the survey-making process, respondents’ perspectives have to be kept in mind and efforts undertaken to make their experience easy and worthwhile.

Here are 16 simple steps on how to write a survey introduction text to make it engaging.

The introduction in survey questionnaires serves as the gateway to a successful survey. A compelling one not only grabs the attention of respondents but also sets the tone for the entire surveying process. A well-framed introduction ensures that respondents understand the purpose and relevance of the survey, making them more inclined to complete it. Essentially, a thoughtful introduction can heavily influence the overall response rate and the quality of data collected.

Every survey is designed for a specific demographic or audience. Understanding them, and what drives them, allows for a tailored introduction that resonates. For instance, a survey meant for teenagers requires a different tone and approach than one aimed at senior citizens. By empathizing with the audience’s perspective, one can craft an introduction that speaks directly to their interests and motivations.

In today’s digital age, consumers appreciate distinctive touches. Personalizing a survey introduction, whether through addressing the respondent by name or referring to past interactions, adds a layer of authenticity. It gives the respondent a feeling of being valued and recognized, which can translate into a higher likelihood of participation.

Clarity is paramount in any communication. A good introduction for a questionnaire is vital in ensuring that respondents immediately understand the survey’s purpose and what’s expected of them. Avoid industry jargon or overly complex sentences. Instead, opt for straightforward and concise language that communicates the essentials without overwhelming or confusing respondents.

Timing can be a determining factor in the success of a survey. For instance, sending a customer satisfaction survey immediately after a purchase or service experience ensures the interaction is fresh in the respondent’s mind, leading to more accurate and detailed feedback. On the other hand, ill-timed surveys may come across as irrelevant or intrusive.

Motivation is a powerful tool. Offering respondents a tangible incentive—whether it’s a discount, gift card, or entry into a prize draw—can significantly boost participation rates. However, it’s essential that these incentives are relevant and appealing to the target audience and then delivered as promised.

With increasing concerns about data privacy, assuring respondents that their information’s safety is non-negotiable is vital. An introduction should clearly outline the measures taken to protect personal information and how the data being collected in the survey will be used. Being transparent about compliance with regulations like GDPR will instill confidence and trust in respondents.

Including contact details in the survey introduction can be a game-changer. It not only offers a channel for respondents to voice concerns or seek clarifications but also communicates transparency and openness. This proactive approach can lead to increased trust and a willingness to participate.

Like any piece of content, an introduction for a questionnaire benefits from testing. Running it by a small group—preferably from the target demographic—and seeking feedback can highlight potential areas for improvement. This iterative process ensures the introduction is optimized for its main audience.

Different surveys serve different purposes and their introductions should reflect this variance. An employee feedback survey will require a different tone and set of assurances than a market research questionnaire. Tailoring the introduction to the survey’s unique context ensures that it will resonate with potential respondents.

The aesthetics of a survey introduction can influence a respondent’s decision to proceed. Utilizing a clean, intuitive design incorporating on-brand colors and images can create an inviting and professional first impression. It’s essential to ensure the design enhances the content—as opposed to distracting from it.

Refinement is the key to perfection. A/B testing, in which two different introductions are presented to separate groups of respondents, can provide insights into which one performs better. This data-driven approach ensures that the introduction is continually optimized based on real-world feedback.

Gathering feedback is an ongoing process. Follow-up surveys, sent after the initial one, can delve deeper into specific topics or measure changes in opinions over time. However, their introduction needs to acknowledge the prior interaction and explain the rationale for a subsequent survey.

Conducting surveys isn’t just about gathering data, it’s about doing so ethically and responsibly. Ethical considerations, including informed consent and participant rights, should be highlighted in the introduction. This ensures participants are aware of their privileges and fosters a culture of respect.

After deploying a survey, it’s crucial to evaluate the introduction’s efficacy. By examining metrics like response rate, drop-off rate, and feedback, insights can be gained regarding the introduction’s strengths and the areas needing improvement. This analysis forms the foundation for future refinements.

The art of crafting survey introductions is one of continuous learning. As markets evolve and respondents’ preferences change, so should the survey approach. By staying adaptive and open to feedback, researchers can ensure their introductions remain effective and engaging.

Based on the checklist above, here is a survey introduction email example that fulfills all the requirements that will act as the perfect first contact with potential respondents.

- Hey there, we would like to hear about your recent customer service experience!

- At [company name], your satisfaction is what we value most. By participating in our survey, you will help us improve our products and offer you even better service.

- This five-question survey takes only ten minutes to complete and is available until the 28th of November.

- It is anonymous. The data gathered will only be used internally to improve our future customer service strategies.

- Click below to access the survey. If you have any additional questions, feel free to contact us at support@company.com . We appreciate your feedback!

The wording of a questionnaire introduction and the information that is included can differ based on the field of research. Check out our survey introduction examples and choose an introduction sample best suited to your needs.

A customer satisfaction survey introduction is likewise an important part of customer experience research. The wording will have a huge impact on whether customers will take the time to answer—or just ignore it.

If surveying recent customer experience, send a survey shortly after customers purchased a product or had contact with the customer support team while the experience is still fresh in their mind.

Stay true to your company’s tone of voice and let respondents know that you appreciate their patronage. An incentive that encourages them to participate can also be offered. Here is a survey intro example:

Thank you for shopping at [company name]! We would like to ask you a few questions to learn about your shopping experience.

This survey will take only a couple of minutes and will be very valuable for improving the services we offer to you. The responses you give will stay anonymous.

Click below to participate, which will get you 30 percent off your next order!

Market research surveys are conducted to get more information about the situation in a specific economic sector and provide valuable real-time insights into the needs of a target audience and how the competition is doing.

Conducting product surveys can help improve existing products or make adjustments before releasing new products or services. Simply put, market research surveys help expand and grow a business.

When doing this kind of research, it is important to determine the target audience. If they are not yet customers, they may not be familiar with your brand, so make sure to introduce it properly and explain why they have been chosen for this research. Here is an example:

- Nice to meet you! We are [company name], and we are working on bringing affordable [your products] to the world.

- Our company aims to develop the best possible products for our customers, and we need your opinion to make this happen.

- Wondering why we chose you? We are looking for [describe your target audience], which makes you a perfect fit.

- We would appreciate it if you took the time to answer this five-minute survey. It is anonymous, and your data will be used only for this research.

- Click below to fill out our survey and get 10 percent off our newest collection!

Student surveys are an important part of education surveys . With them, feedback is garnered from students regarding teachers, courses, curriculum, extracurricular activities, and much more.

Measuring students’ satisfaction levels helps highlight the strengths and weaknesses of a school, which in turn helps improve decision-making. However, in order to get accurate responses, certain steps are required, including how the introduction is written.

When making surveys for students, ensure they are anonymous. Many students may be afraid of retaliation, which will make them reluctant to give honest opinions.

Emphasize their anonymity in the introduction. Explain why this research is being carried out and how the gathered data will be used. Here is an example of a student questionnaire survey introduction:

- Thank you for being one of our students at [name of your school]. Please take the time to answer this short five-minute survey and let us know how satisfied you are with your chosen courses from this semester.

- This survey is anonymous, so feel free to answer honestly. It will very much improve the accuracy of our data and help us improve the curriculum as best as possible.

Conducting human resource surveys can greatly improve a workplace, which will result in happier and more productive employees. Find out about the work-life balance of employees and the overall company culture, measure the motivation and engagement of employees, and learn how satisfied they are with their jobs.

When writing the survey introduction, focus on the same aspects as above. Emphasize that the survey is anonymous and communicate this openly to employees. This will encourage them to share their honest opinions and help gather valuable and accurate responses.

Some research papers require conducting surveys on a particular topic. Writing a research questionnaire introduction for a research paper is no different than writing one for the previously mentioned purposes.

Introduce yourself and the topic to respondents and explain the purpose of the research and the benefit to them for participating. Include other information about the survey that you think is needed, though make sure to not overdo it. Keep it short and simple for high survey completion rates.

Writing a survey report is one of the seven steps of conducting survey research . It is the last one after the data analysis and is crucial to presenting findings.

A survey report introduction is very important for the success of a report. Its purpose is to introduce readers or listeners to the topic and the ultimate findings of the research.

The same advice applies: keep it short, use simple language, and incorporate only the most important information.

And above all, put yourself in the shoes of the audience. Unlike you, they have not been spending months with the survey and supporting material.

Good survey introductions help increase response rates and gain respondents’ trust. They are a perfect way for respondents to get to know you better, as well as the research topic and the ways they can benefit from it.

Here are some additional tips to create the best survey introductions, regardless of the topic of your research:

- Make the survey anonymous and make sure respondents are aware of that.

- Add a logo to the survey to increase brand recognition.

- Don’t forget to keep the tone of voice on-brand.

- If brand identity allows it, use a familiar tone.

- Offer incentives for survey completion.

- Thank the respondents for completing the survey.

Of course, before writing a survey introduction, you need to create the survey. With our help, amazing questionnaires can be made in no time. Sign up to Survey Planet today, create a survey for free, and add a well-written introduction using our tips!

Photo by Bench Accounting on Unsplash

Cookie consent

We use our own and third-party cookies to show you more relevant content based on your browsing and navigation history. Please accept or manage your cookie settings below. Here's our cookie policy

- Form builder Signups and orders

- Survey maker Research and feedback

- Quiz maker Trivia and product match

- Find Customers Generate more leads

- Get Feedback Discover ways to improve

- Do research Uncover trends and ideas

- Marketers Forms for marketing teams

- Product Forms for product teams

- HR Forms for HR teams

- Customer success Forms for customer success teams

- Business Forms for general business

- Form templates

- Survey templates

- Quiz templates

- Poll templates

- Order forms

- Feedback forms

- Satisfaction surveys

- Application forms

- Feedback surveys

- Evaluation forms

- Request forms

- Signup forms

- Business surveys

- Marketing surveys

- Report forms

- Customer feedback form

- Registration form

- Branding questionnaire

- 360 feedback

- Lead generation

- Contact form

- Signup sheet

- Help center Find quick answers

- Contact us Speak to someone

- Our blog Get inspired

- Our community Share and learn

- Our guides Tips and how-to

- Updates News and announcements

- Brand Our guidelines

- Partners Browse or join

- Careers Join our team

How to write a compelling survey introduction—get your response rates to soar

You only get one chance to engage your potential respondents with an online survey—and it all hinges on the introduction. Read on to find out how to persuade people to click through to your first question.

What to include in your survey introduction

There are some important details you really have to include in an introduction.

Before you set your mind to details of your writing, make sure you have the basics set in stone. There are five points you need to include in your survey introduction:

Your organization

The goal of the survey

How much time this will take

Anonymity/privacy of personal information (link to your privacy statement)

Relevant instructions

Now let’s take a look at each of them in more detail.

You wouldn’t grab someone in the street and ask them to fill out a survey with no introduction—so don’t do it online with your survey software.

It’s important for the people answering your survey to know who you are before they start, or you’ll be left with a bunch of nonresponses.

Improving your brand recognition is always a good idea. Especially if you want people to do more surveys for you in the future.

But don’t go on and on about yourselves. The more you talk about your own company and how great it is, the more biased the survey will feel.

Simply let people know who the survey is coming from—with a quick explanation of who you are. If they want to know more, you can leave a link to your site—or add it on your Thank You Screen at the end.

Be honest about why you are sending this survey research.

If you’re being vague about your objectives or failing to mention them altogether—your readers will find it hard to trust you.

Try to be as transparent as possible. Not only will this improve your responses, but people deserve to know what they’re taking part of.

People are busy—and time is money. Give an estimated time for completion upfront e.g. “This will only take a few minutes of your time.”

Don’t leave your readers in the dark. If they don’t know if there are five or five hundred questions left, they’ll get bored and impatient halfway through and hit the dreaded X button—or write half-hashed, inaccurate responses. And nonresponses are good for no one.

Let the people taking your survey know how far they are from the finishing line before they even start giving answers.

This is a big deal. You have to be clear and honest about what privacy rights people have.

If the responses you get from a survey are going to be anonymous, then let people know. Emphasize it—’cause you’ll get more honest answers if people understand that their answers remain confidential once they finish.

If you can’t offer anonymity to respondents—then they have the right to know that too.

Be fair with the people taking your survey. No one wants to give personal answers to something—only to have their answers used against them in the future.

Want to keep it short and sweet? You can always include a link to the privacy statement of your company. Give a very quick outline of the policy in the introduction, and give people the chance to learn more if they want.

Be clear about what your readers actually have to do in the survey or questionnaire .

Let’s say that you ask:

On a scale of 1-10, was this the tastiest type of cake?

Is “1” the tastiest score, because it’s number one? Does “10” represent the best cake, because it has a 10/10 flavor?

Who knows? Well, you will—but your readers won’t.

Asking questions like this means you’ll get answers from people in both camps. This means the answers you get will be worthless and your data can’t be used by your research team.

Keep the instructions as clear as possible. Ask someone to take the survey first. If they are confused by the questions, then the people taking your survey definitely will be too

Survey introduction writing tips

So now the necessary parts are taken care of, you need to focus on standing out from the crowd.

A perfect survey introduction is more than just a jumble of details and instructions. It’s the first contact you have with the people you will be relying on—so it’s important to start things off on the right foot. Make sure you:

The robots haven’t taken over yet—you’re not interviewing androids. You’re asking real people questions, so speak to them like, well, a human.

Keep the jargon for the boardroom. Speaking in formal, academic or technical language will just confuse most people.

If you open up with “Our company is looking for 100 respondents to answer a market research study on…” , then the survey will seem like some long, dry, serious read.

Try to humanize your speech in your survey intro.

Turn that cold, corporate speech into “We have a few questions to ask about…” .

Simple. Friendly. Human.

Always say thank you—you’re getting something from your readers with this survey.

Besides, if the people taking your survey feel their answers are valued, they’re much more likely to give genuine and thought-out answers

Your readers will appreciate it. Plus you’d make your grandmother proud.

A good introduction is a quick summary of the content that’s about to come up.

It’s the same in any medium, really.

So the best time to write your introduction is at the end of the writing process.

Why? Well, if you’ve gone through the entire process of planning and creating a survey, you’ll have a deep understanding of the content, hopefully.

Writing an introduction early on means you’ll be constantly editing if you make changes to the rest of the study.

If you do it at the end, you’ll have all the other parts ready to go—so this is the simplest time to put everything in a nutshell.

What’s the point of this study? Why should the people answering your questions care about them at all? Why should they spend five minutes on this survey instead of on Buzzfeed?

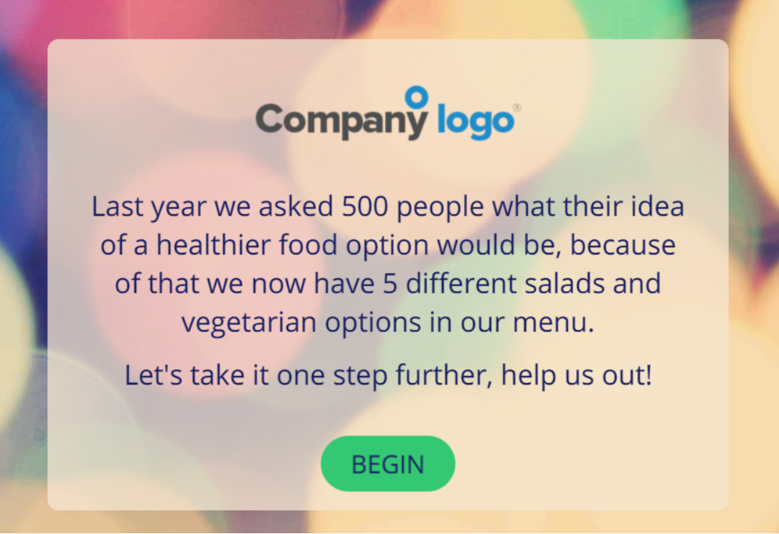

The best way to do this is to explain how these surveys had made a difference in the past.

Whether you’ve carried out research that led to policy change or simply asked employees about how they felt at work—then adapted the environment to suit them better, it’s certainly worth adding that info.

If you can show your survey isn’t meaningless research for some faceless organization, but rather information that can lead to positive change—then your readers have much more incentive to give thoughtful answers.

Encourage people to be happy to be part of the process.

Let’s take a look at a couple of good survey introduction examples from our fictional companies that follow this advice.

Customer surveys: feedback form introduction

Imagine that a customer has made a purchase from your shop, Absolutely Amazing Shoes , and you’d really like some customer feedback . Let’s look at how to introduce a survey you’d send to customers. First off, this person just bought something. So be gracious right off the bat. You’re happy they are a customer, right? Well, let them know.

The shop’s name is included, and stylised as their brand name. But the reader knows exactly who you are–so we can keep this to an absolute minimum here and still boost your brand recognition.

Readers know how quick this is going to be, and why they should give an answer.

Market research survey introduction

Undertaking market research is certainly different to customer feedback. But the same rules apply. Take a look at our example from Enough Plastic, a global anti-plastic NGO.

Let’s check this against our list from before.

Since this is possibly the first time the reader has heard of Enough Plastic, it’s important to add a short explanation. Readers get another way to learn more if they want, but you get the idea of this organization in a single sentence.

Letting your readers know this is a longer survey is important. For people who don’t want to take ten minutes on a survey, they see this right away and inaccurate answers don’t get included.

Readers are told about this study and are encouraged to give honest replies. Littering and wasteful behavior can be embarrassing to admit, so anonymity will be very important to anyone taking this survey.

The introduction ends with a sincere thank you and represents the global nature of not just the organization, but the planet as a whole.

How you ask is everything.

- Student Program

- Sign Up for Free

How to Create a Survey

How to write a survey introduction (plus examples)

The first thing participants should see when they open a survey is a survey introduction. It’s a crucial piece of the survey puzzle, providing information about the survey topic, who’s conducting the survey, the goal of the research, and any other pertinent details that may encourage people to participate.

In other words, a survey introduction is your opportunity to make a good first impression — and to make a strong case for why recipients should help you out.

The tone of your introduction can be warm, funny, formal — even somber — depending on the goal of your survey. Done right, a good introduction can warm participants up to your request and make them more willing to respond.

Just so you know

Learn how to make a survey with our complete guide or get started today with Jotform’s free online survey maker !

The importance of survey introductions

Most people don’t want to spend their time filling out a survey if they can help it. Even if you offer them an incentive, say, a gift card or other reward, people may not take the time to fill out your survey thoughtfully and accurately.

A good survey introduction can solve these issues by providing important context for the participant. Consider the introduction as not just an informative piece, but also a light sales pitch — you’re essentially trying to convince participants to dedicate their time and energy to completing your survey as accurately and honestly as possible.

When done right, a survey introduction can do a few important things:

- Boost response rates: A clearly stated, convincing objective is more likely to make participants believe that the survey is worth their time.

- Set clear expectations: Informing participants on what the topic is, how much time the survey will take, and how you’ll use their answers helps build trust and reduces survey abandonment.

- Increase engagement: A well-crafted introduction can make any topic — even a dry or technical one — more intriguing. It can also help make participants more invested in completing the survey.

- Improve response quality: An introduction that clearly explains why participants’ input matters sets the stage for more thoughtful responses to your questions.

Keep reading to learn how to craft a perfect survey welcome message.

The ideal survey introduction: Important details to include

The name of your company or organization.

If you met a stranger on the street, you wouldn’t ask them for a favor without properly introducing yourself, would you? The same principle applies to an online survey — people want to know the person or organization behind it. Your survey introduction should identify who you are and include your company’s logo and name for brand recognition.

If your survey is intended for an audience that’s familiar with your organization, your logo and name will help respondents feel more confident about filling it out. If your audience isn’t acquainted with your organization, then it’s even more important to identify yourself. If you fall into the latter group, give a brief description of your organization, explain what you do, and include a link to your website or another place where they can find more information.

The goal of the survey

Make your objectives clear. State the goal of your research and what it will help you achieve. The more your readers understand your goal for the survey, the more likely you’ll be to get responses. Being transparent about the purpose of your research will engender trust and make people more willing to complete your survey.

Privacy and confidential information

Privacy is a big deal — people want to know how you’ll process the information they provide and how you’ll handle their personal information. Let everyone know up front whether their responses will be anonymous or not.

If you’ll be collecting personal information, let your respondents know what you intend to do (or not do) with that information. For instance, if you need their email address to follow up with them, make sure they know they can opt out at a later date if they decide not to continue with the survey.

The time required to complete the survey

The length of your survey can be a deal-breaker — people are busy, and they want to know right away how much time your survey will take to complete. This is why you should ask only the most essential questions pertaining to your goal.

So give a realistic estimate of how long it might take to complete your survey. For a more accurate estimate, take the survey yourself (or ask someone to do it for you) so you can see how long it takes to reasonably answer the questions.

Other relevant information or instructions

Each survey is different, so use your best judgment about any information you should disclose. Your goal is to be as transparent as possible so your respondents don’t find any unpleasant surprises ahead. If you think something could pose a problem, then it’s probably a good idea to state it in your welcome message.

Examples of good survey introductions

Let’s look at a few real-life examples of surveys that have great introductions or welcome messages, and see what we can learn from them.

Example 1: Keep it short

This survey by Resco Products shows respect for the user’s time. It gives the exact number of questions in the survey and the approximate time needed to complete it. In Jotform Cards , you can display the question count as part of your survey introduction.

Example 2: Make the terms clear

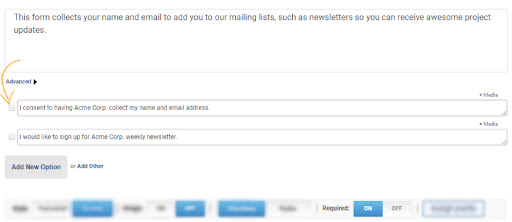

This survey about cycling habits lets participants know how the organization will use the data the survey collects. It also explicitly asks people to agree to the terms before giving them access to the survey.

Example 3: Say it with video

This survey uses an introductory video instead of a written introduction to get participants’ attention. Videos are far more engaging than text. In fact, one study showed that social video gets a lot more shares than text or images — a shocking 1,200 percent more for video than the other two combined.

If your introductory video hits the right note with your participants, you could see a lot more shares and responses.

Example 4: Provide necessary details

Survey introductions are best when they’re short and sweet, but there are occasions when you need to get into the details.

This COVID-19 rapid assessment survey explains the reasoning behind the survey in a comprehensive way, and here’s why: Not only does the survey ask for personal health information, but the organizers also want to follow up on the participants as appropriate. In this instance, participants need all the information they can get about the survey’s importance and how the organization will handle their personal data.

Example 5: Stay upbeat

This survey from the National Bicycle Organization projects an enthusiastic and positive tone. It also tries to promote a sense of “we’re all in this together” by using inspirational language: “Be part of the 1st 1,000 responders who will change history.” If your survey situation calls for it, include some inspirational words of your own to encourage people to respond.

Create the perfect survey introduction with Jotform

A well-crafted survey introduction will, in many cases, encourage users to fill out your survey. Using the Jotform Form Builder , you can customize a welcome screen that includes your survey introduction. Jotform’s flexible features allow you to customize your survey introduction and your survey to meet your needs.

Learn how to create a survey introduction in Jotform below using either the card or classic form types. Classic forms are the more traditional, scrollable versions of forms, while cards present questions or prompts one at a time.

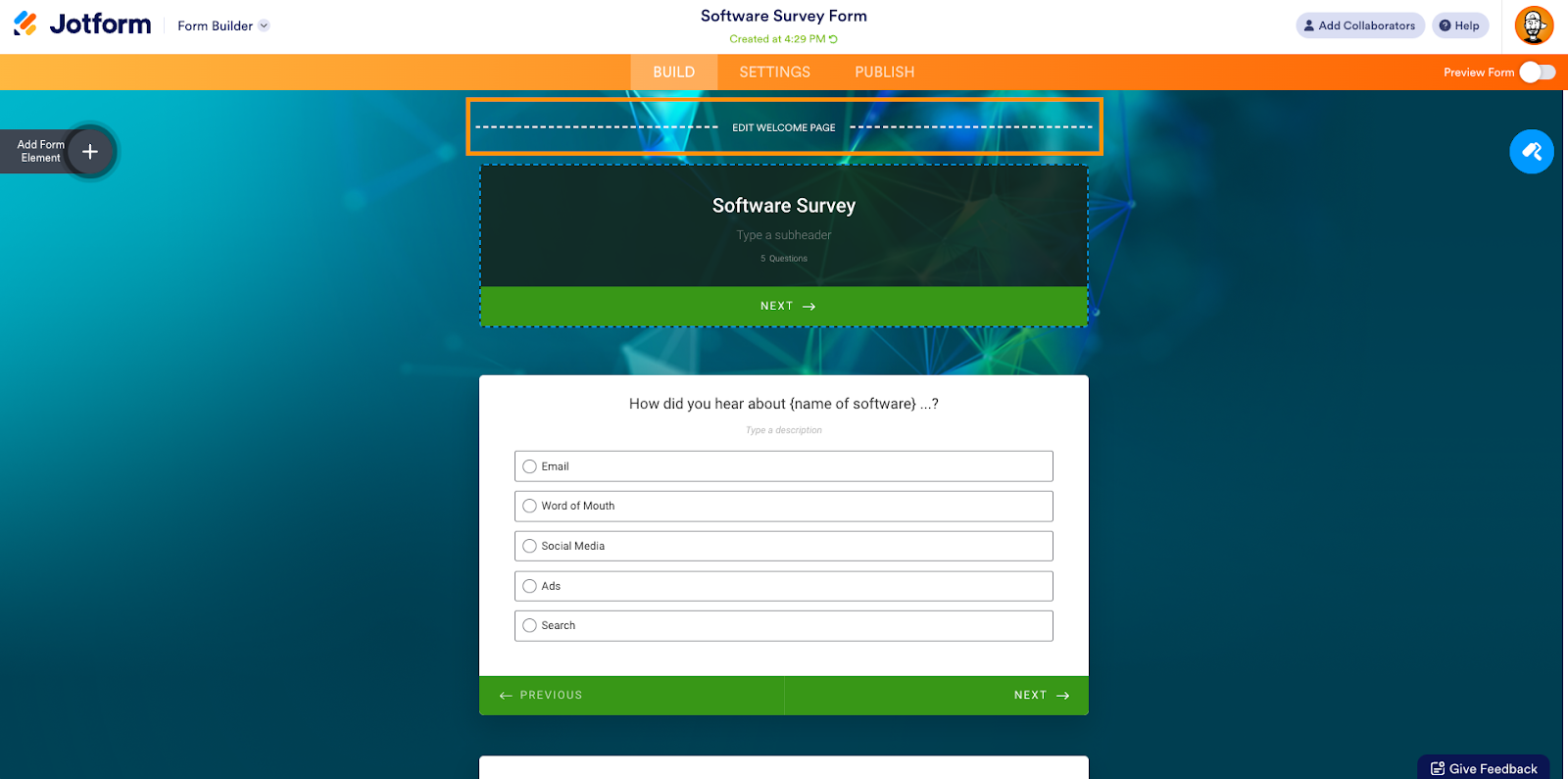

How to create a survey introduction for a Jotform Cards form

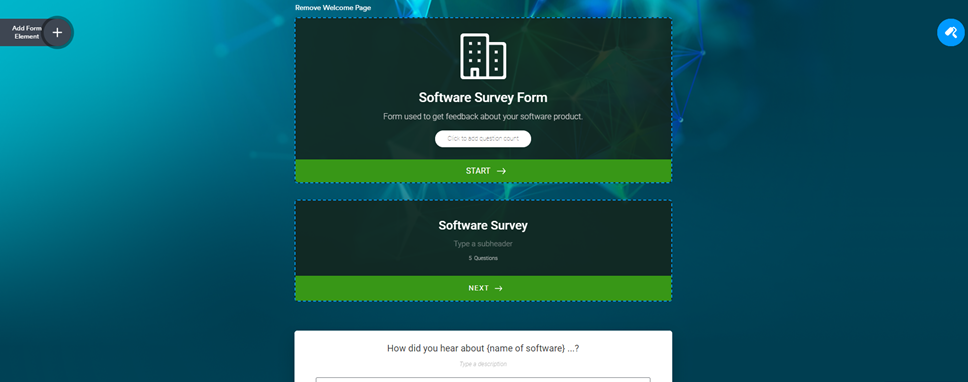

Survey introductions — called “welcome pages” in Jotform — are built into Jotform Cards, so all you need to do is customize them to suit your needs.

Follow these steps:

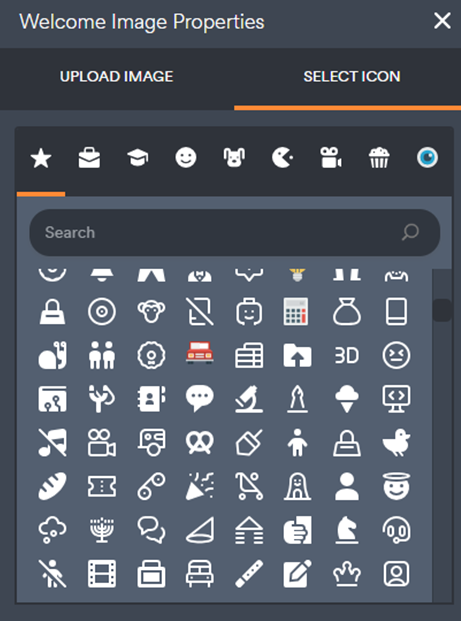

- Select a survey template. We’ll use this software survey form as an example.

- Click Edit Welcome Page.

- Upload a new image that corresponds with the survey. This may be your company’s logo or an image related to the survey topic. If you want to use an icon instead, Jotform offers a large library to choose from.

You can also simply remove the image altogether if you don’t want to include one.

- Change the headline and subheading to fit your needs.

- Show or hide the question count, then click another form element or click in any open space to save your changes.

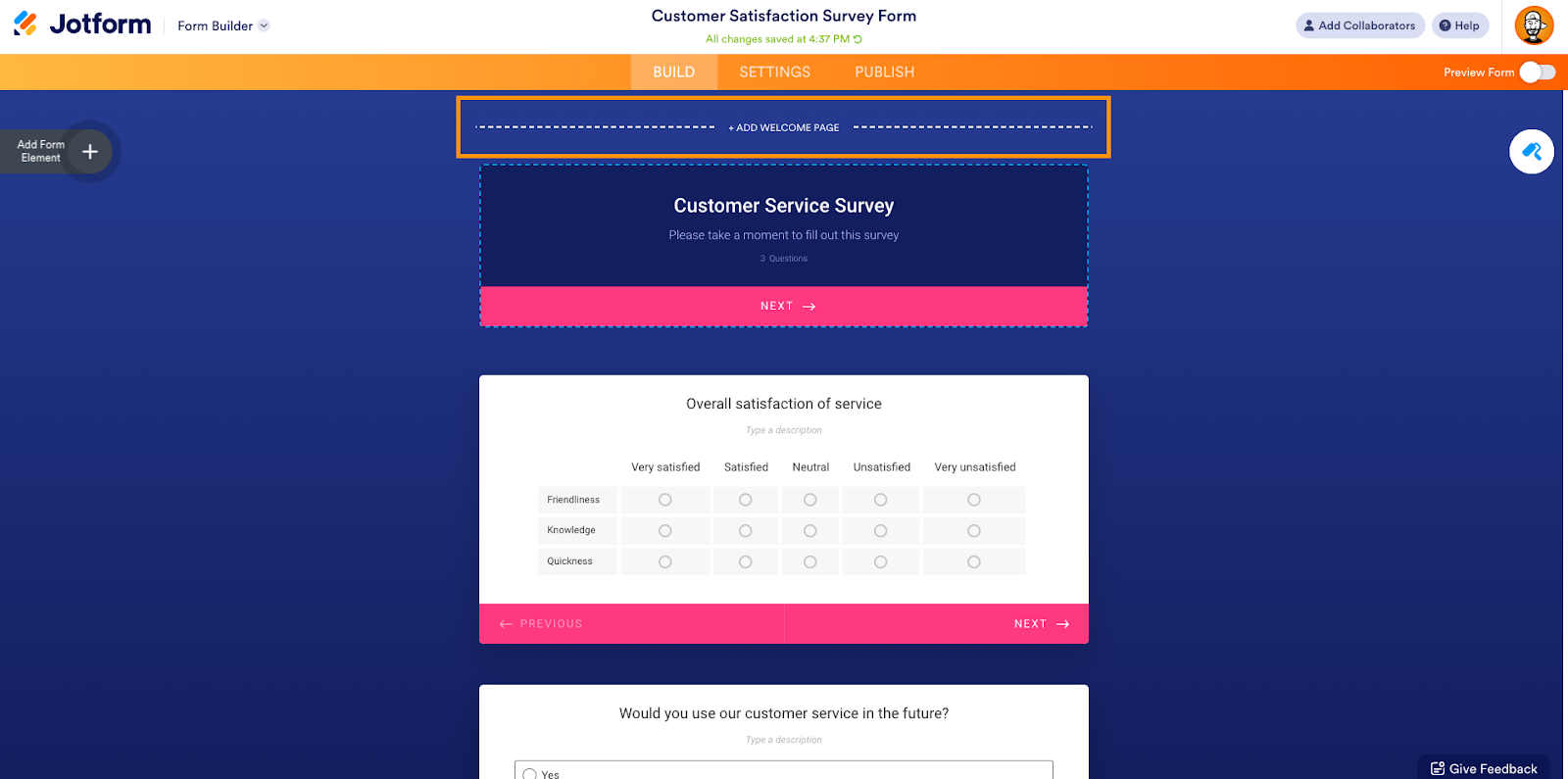

How to create a survey introduction for a classic Jotform form

Classic forms don’t have built-in welcome pages, so you’ll need to create one. No worries — it’s a super simple, quick process!

- Select a survey template. We’ll use this customer service survey as an example.

- At the top of the form, click + Add Welcome Page (or + Edit Welcome Page if the template already includes a welcome page).

- Build your welcome page into a proper survey introduction by adding form elements such as a survey title, logo or other image, and your introductory text. You can also select Click to add question count to display the number of questions in the survey.

See how easy it is to create your survey introduction? All it takes is a few steps — so you can start building forms with Jotform today!

Thank you for helping improve the Jotform Blog. 🎉

- Data Collection

- Data Management

- Form Templates

RECOMMENDED ARTICLES

SurveyMonkey vs SurveySparrow

Offline surveys: How to collect data anywhere

How to embed a survey in an email

Top 6 advantages of open-ended questions

SurveyMonkey vs Alchemer (Formerly SurveyGizmo)

22 excellent customer service survey questions

Social media survey questions: Examples and best practices

What is a good survey response rate?

CRM survey benefits, best practices, and example questions

5 types of questionnaires

20 religion survey questions to ask your church community

4 types of survey questions to engage your audience

Best training survey questions to evaluate effectiveness

How to collect secure survey data

30 insightful hotel survey questions

How to ask someone to take a survey via email

Webinar: How to use surveys and email marketing to gain key insights

Top diversity and inclusion questions to ask employees

How to avoid survey fatigue

How to write a survey reminder email

The best newsletter survey questions to ask

Survey questions 101: Examples and tips

8 of the best WordPress survey plug-ins

65+ e-commerce survey questions for valuable business insights

Basic product survey questions to ask customers

Top 9 Qualaroo alternatives in 2024

Types of survey bias and ways to avoid them

15 of the best Refiner.io alternatives in 2024

How is public opinion measured with surveys?

How to do a poll in Slack

Top 15 employee pulse survey tools

11 top survey incentive ideas

5 UX survey tools to help you create a winning user experience

29 best customer experience survey questions

How to make Google Forms anonymous

Closed-ended questions: Definition and examples

How to create an NPS® survey email that gets results

How to ask someone to fill out a survey

Top podcast survey questions to ask guests and listeners

20 business survey questions to ask your customers

How to create an anonymous survey for employees

How to add a “poor to excellent” scale to your surveys

How to write a survey report

The 6 best customer satisfaction survey tools

The 4 survey data collection software you should start using today

4 tips for creating effective quantitative surveys

How to conduct a pricing survey: Questions to ask

How many questions to include in an online survey

How to use open-ended survey questions

Real estate survey questions for buyers and sellers

Top 6 QuestionPro alternatives in 2024

How to get the most out of Peakon surveys

10 questions to ask in your membership survey

How to calculate the Net Promoter Score® (NPS®)

Qualtrics vs SurveyMonkey: Which should you choose?

How to create a survey in Microsoft Word

9 examples of ranking survey questions

Multiple-choice survey questions: Examples and tips

8 leading Survicate alternatives for customer feedback in 2024

10 AidaForm alternatives that make data collection a breeze in 2024

Survey report examples with informative visuals

Survey vs questionnaire: Which one should you use for your next project?

How to write a research question

How to conduct an online survey

How to improve survey accuracy

Survey data collection: 5 best practices

Ordinal Scale Questions: Definition and Examples

Cybersecurity questionnaires: How to assess online threats

SurveyLegend alternatives in 2024

20 essential human resources (HR) survey questions

20 psychology survey questions to ask your clients

How to measure customer experience: Key metrics and KPIs

How to close a survey on SurveyMonkey

16 best survey tools worth checking out

7 important user experience survey questions you should ask

How to embed a survey in a website

How to send a survey to your email list on AWeber

How to create an employee pulse survey

Top 14 demographic survey questions to ask

Announcing Jotform’s free Student Survey Program

How to create an inviting welcome screen for online forms

50 mental health survey questions to ask employees

What are ambiguous survey questions, and how do you avoid asking them?

4 survey design tips to get more accurate results

How to write good survey questions

The 5 most powerful Bucket.io alternatives for 2024

How to analyze survey data

Yes-or-no questions in online forms and surveys

80 survey question examples and when to use them

14 best SurveyMonkey alternatives in 2024

How to automate survey follow-up emails

How to turn survey results into a great presentation

Qualitative vs quantitative questions: What you need to know

10 of the best StrawPoll alternatives

Top 5 Qualtrics alternatives for 2024

5 tips for creating great qualitative surveys

5 ways to improve your online surveys

Survicate vs SurveyMonkey: Comparing online survey platforms

Pre-sales surveys: How to focus on your best leads

Send Comment :

1 Comments:

More than a year ago

Simple but great insite

Survey introduction examples that actually work

- Written June 22, 2017

- by Rens Deckers

Writing a solid survey introduction is not a waste of time.

You’ve created a survey and you need answers. Preferably without respondents going “NOPE” at seeing the word “survey” in their mailbox.

It’s your one window to get in, create a feeling of sympathy and make people feel like “Mmkay, I want to help these guys out with my answers”.

In fact, it’ll be the same trigger that pushes you to read this article or not. (No hard pushes though, just a gentle nudge. OK?) There are a few essentials that make up an irresistible survey introduction. We’ve collected all of them for you in a useful list and written up a good (copyable!) example of each approach. And one PERFECT template that combines them all.

4 Aspects of writing a solid survey introduction

1. provide all (relevant) necessary information.

Based on what you want to ask and who, choose from the items below. Don’t write an endless introduction for the sake of being correct.

Limit yourself to giving the essential information, and the trigger that your audience needs to take action. Let people know:

– What’s your purpose?

If I asked you a bunch of questions, you’d want to know why I’m asking and why I’m asking YOU specifically.

Being clear and transparent about your purpose will help people see you as “someone they can help”. Give them a chance to be a hero for one day. 😉

Simply state the reason for your survey and what you want to achieve with it, will persuade more people to complete it.

Use this template : We’d really like to find out how you feel about [research topic]

Saying what your purpose is, helps people value your research.

But actually showing what you do with your research , that’ll just draw them right in!

If you have previous results you can refer to and tie this to how people can help you now.

Don’t think, do it!

– Is it private?

Privacy is tricky as it is. With people becoming more and more aware of the importance of their personal information, it’s necessary that you are up front.

Always be clear about what you plan to do (or not do) with the collected information and you’ll ease respondents into answering more truthfully.

Use this template : No! We don’t want to spam you in any way. So don’t worry, you will remain completely anonymous.

If your respondents aren’t anonymous, be clear to state what will happen to their information and why:

Use this template: We appreciate you letting us know who you are. We don’t want to spam you in any way, the data we collect will be used only for this research.

Extra tip: There’s only so much room in an introduction screen. If you want to be thorough, you can always add a link to your privacy policy in one of the slides before you ask your respondent to submit their answers.

Just in case you do plan to reach out to them afterwards. Always give respondents the option to “opt out” :

Use this template: If you want to be informed about the results of this survey and receive other news from [company name], enter your email here.

– How long will it take?

This is THE most frequently asked question when people take a survey. Try to give your respondents a realistic estimate of the time it’ll take to answer your questionnaire.

Now let’s be honest!

We both know that your 10 open-ended questions will not get answered if you promised that the survey would only take a minute.

It’s up to you, not only to be honest about the duration, but also to make sure that you limit your survey to the essential questions and no more.

Respondents can and will abandon you for this.

When we send out surveys through email we will always write something along the lines of “This survey will only take 49 seconds of your time. Really! We timed it 😉 “.

(We actually do time it!)

Use this template: We realize how precious your time is. That’s why we made sure this survey will only take a quick [amount of time – preferably in seconds].

– What’s in it for me?

People want to win stuff. It’s simple.

Winning does not necessarily mean a big prize. People like to get knowledge in return, have a little fun with a game, get a coupon, …

Incentives are the perfect and easiest way to boost your participation rates. (Aside from the introduction examples, make sure the incentive is relevant and useful. Big and expensive does not equal relevance!)

Even people who are initially uninterested can be won over with a well-chosen incentive. Add more power and a little tease by adding a picture or video of the incentive.

Use this template: Think we were going to let you leave empty handed? 🙂 Take this survey and have a chance at WINNING our big prize [that you should specify here]!

– What audience am I in? Of course, your survey will have a certain target audience. So when approaching potential respondents about a survey, make sure to inform them about this chosen target audience.

Quickly let them know why you chose this segment and how your respondent fits in. It’ll increase their recognition of how they can help you personally.

Use this template: Wondering why we chose you? We’re looking for [that which specifies your target audience]. And that’s why you’re a perfect fit!

– Who am I answering these questions for?

Knowing from which company the survey originates is another way of convincing your target audience.

Give some basic information about yourself as participants will be more reluctant to share any data with an unknown company.

Use this template: Nice to meet you! We are [company name] and [a little bit more about your company, or jump straight to the purpose of your research]

2. A simple thank you

Power up your survey introduction with a thank you note.

Hey, it’s not only a sign of appreciation, it’s the least you can do!

Your participants are giving up their time for you to benefit from.

They are not gaining anything from doing this (except maybe your super relevant incentive). Try your best to make this experience as human and “spontaneous” as possible by adding a personal touch, especially by thanking your respondents.

(Thank you, by the way. You’re doing an awesome job reading all the way to the end… )

Use this template: We personally want to thank YOU for every second invested in our research. You rock!

If your company and research allows it, make this even more personal. Give your brand a face. Adding a real person’s name works just as well in surveys as it does in a newsletter, blog post or podcast.

Use this template: Thanks for helping us out. From all of us at [company name], [your name] [your title (optional)]

3. Less is more

Take everything you’ve learned in the previous steps… And now scratch that!

We recommend to always write your survey introduction text as short as possible.

???? … Sorry, I know!

People – especially those in a hurry – don’t want to waste their time reading page-long introductions before finally being able to start your survey. Use only the essentials from the above tips. Then go ahead and just make your point.

By writing up your survey introduction as short as possible, you force yourself to only focus on the most important message . And you don’t waste respondents’ time even before they’ve taken the survey. Getting them in is what’s most important.

Tip: If you want to analyze the way users read your surveys in order to predict their performance more accurately, maybe one of the AI consulting tools we looked at, Neurons, has what you need.

4. Inviting atmosphere is key

The first step for your introduction is making sure people will enter your survey and answer questions. Your second priority, is making sure they’re honest.

Here’s how to get that done:

Honesty: “You get what you give. What you put into things is what you get out of them.” – Jennifer Lopez.

Don’t expect your participants to blindly answer in a truthful way if they don’t know the full picture surrounding your study. Offer all corresponding information from the very beginning to avoid sloppy data which could lead to “brand dilution”.

Neutrality: Try to remain neutral throughout your entire survey, not just your introduction. You often see companies using one liners like “leading company in our niche” or “Bringing you the best service”. Don’t do this! As it will only create confusion and prejudice instead of confidence and reliable data.

Now let’s summarize, and get to the good stuff:

The perfect survey introduction example

Followed all of the steps above? Nice! You will have a survey introduction that is perfect and by the book!

Does it look like it got a bit too long? Too much info? Simply not as appealing as you thought it would be?

We wrote up a short, generic and to-the-point version for you to use. The perfect survey introduction example:

Use the ultimate template:

Hey, glad to see you around here! First of all, let me thank you for taking our [survey duration] survey. You are a great help! 🙂 We at [company name] are on a daring quest to collect the right data about [survey subject]. Our target audience involves everyone who [target audience]. This is why we chose you! And don’t worry, your data is just for [where you will use it] ]so [be clear about their privacy]. We promise! – Get started and take your chance to WIN [a grand prize]

It’s most important to make this introduction represent you as a brand, organization or person. It’s the first step of starting up a conversation.

And don’t be afraid to entertain: Don’t bore, get more. 😉

Extra tips & inspiring introduction examples

1. increase brand recognition.

Hey it’s you!

By adding your logo at the top of your intro screen , you’ll increase brand recognition without having to push it forward during the entire survey.

Make people feel like they’re talking to an old friend.

2. Use a conversational tone

Most people still associate surveys with these boring tasks that are basically – let’s face it – a waste of their time.

Spice up your language and bring some humanity into your questions .

Making your surveys more conversational will benefit your participation and completion rate tremendously!

EXTRA: If your brand and tone of voice allow it, throw in an interjection here and there. A “yee-hah” to show joy or an “ooh-la-la” to let respondents know they can win a prize?

Works like a charm.

Take a look at this list of interjections , for exclamations in every kind of situation.

3. Turn a frown upside down with emoticons

Go back 15 years in time and nobody would even THINK of using a smiley face. Well, that period is over and now it’s totally fine.

In fact, did you know that the use of emoticons in your communication increases the empathy towards your brand ? Perfect to express the mood of your survey, if your message is a playful one.

4. What’s in a name? Don’t use the word “survey”

Long, boring, difficult, too much work, … the word “survey” brings out some awful associations. We cannot blame our respondents. Instead, ask people to answer “a few questions” or to “spare a minute of their time”.

By avoiding the actual word you’ll see an increase in clicks and actual responses. This works in the introduction screen of your questionnaire, but in your email invites as well for example.

Keep in mind though that you should stick to just 4 questions if that’s what you said!

5. Show off the (incentive) goodies

A reward for answering a couple of questions lowers the threshold tremendously! Even more so if there’s a game or contest connected to the reward . The thrill of playing and possibly winning something is a perfect addition to your survey introduction.

6. In all seriousness

There’s a time and place for everything, so if your questionnaire is much too serious for smileys or “whoopees”, you can still write up a longer introduction that eases the respondent into the setup.

A competency assessment, like the above example, is something that requires more information. They managed to put quite a lot of it in the introduction, but decided to refer to an informative page via a hyperlink in case an employee would like to read up before getting started.

Create your own assessment for free!

About the author:.

Rens Deckers

10 responses.

Great tips to help get engagement and not sound like one more boring request for info

Thank you for taking the time to offer this guidance.

One of the great article! Precise and Clear Information, Kudos!!!

I should have read this in the past. I could have a great format. Thank you!

Thanks a lot. This will really help me.

Fruitful & eye opening. Thank you very much.

Thank you for your fantastic tips.

Great Tips. Took something away. Always good.

Quite helpful for a lively sourcing of needed information. Thank you lots.

Thanks for sharing!

Recommended reading

9 AI tools for different types of consulting

In this article we’ll walk you through 5 AI tools you can use in your consulting business.

Vlerick Business School digitalizes entrepreneurship development with Pointerpro [case study]

What do a top-tier international business school based in the capital of Europe and Pointerpro have in common? At the

How to drive your consultancy business with a readiness assessment (part 1/3 of blog series)

If you went to the doctor tomorrow because you don’t feel well… would you be satisfied with a diagnosis that

Want to know more?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get hand-picked articles directly to your inbox.

The Pointerpro newsletter brings you the latest market trends and will give you an overview of compelling testimonials from our community. Register now!

Popular Articles

Get to know us.

Contact us Careers (We’re hiring!) Affiliate marketing

Help Center

Certifications.

ISO 27001 Certified

Careers (We’re hiring!)

Let’s stay in touch, we’d like that

How to Write a Survey Introduction? Guide with Examples

Surveys can be instrumental in gathering insights, but their success often depends on the introduction. Crafting a well-written survey introduction can lead to higher response rates and ensure that the survey data collected is highly relevant. This guide will cover all the essential elements that a compelling survey introduction should have, provide examples for different types of surveys, and offer additional tips to help you optimize your response rates to gather honest feedback.

Survey Introduction “Must Have”

Conducting research or an online survey can be a daunting task. As well as… completing one.

When you think back to the last time you completed one, you may remember what motivated you to do it. Most likely, you found it worthwhile and understood its purpose.

A survey is usually introduced with a welcome message that explains why your feedback is essential and how it will be used. Introductions are like sales pitches; the survey author must persuade the respondent to believe them. By doing so, the study can gain valuable insights.

Let’s explore how to create an effective survey introduction and collect customer feedback .

Surveys for Master and Bachelor Degree Thesis

This template will help you get information on how parents can provide support for their children’s educational development.

How to Write a Survey Introduction

Here are five proven ways to write a good welcome message to survey participants.

Identify Yourself Clearly and Professionally

Transparency is critical in the world of surveys. The first element of a compelling introduction is identifying yourself or your organization. Ensure your introduction reflects a professional tone, aligning with your brand image. A professional introduction establishes credibility and assures respondents of the survey’s legitimacy.

Explain the Survey’s Purpose

When participants comprehend the reason behind their selection for a survey, it brings in a level of customization. Whether it’s because they are esteemed customers, respected employees, or belong to a specific group, clarifying the criteria for selection establishes a bond. This bond, in turn, nurtures a feeling of purpose and enhances the likelihood of sincere responses.

Provide an Estimate of Completion Time with Accuracy