Are You Down With or Done With Homework?

- Posted January 17, 2012

- By Lory Hough

The debate over how much schoolwork students should be doing at home has flared again, with one side saying it's too much, the other side saying in our competitive world, it's just not enough.

It was a move that doesn't happen very often in American public schools: The principal got rid of homework.

This past September, Stephanie Brant, principal of Gaithersburg Elementary School in Gaithersburg, Md., decided that instead of teachers sending kids home with math worksheets and spelling flash cards, students would instead go home and read. Every day for 30 minutes, more if they had time or the inclination, with parents or on their own.

"I knew this would be a big shift for my community," she says. But she also strongly believed it was a necessary one. Twenty-first-century learners, especially those in elementary school, need to think critically and understand their own learning — not spend night after night doing rote homework drills.

Brant's move may not be common, but she isn't alone in her questioning. The value of doing schoolwork at home has gone in and out of fashion in the United States among educators, policymakers, the media, and, more recently, parents. As far back as the late 1800s, with the rise of the Progressive Era, doctors such as Joseph Mayer Rice began pushing for a limit on what he called "mechanical homework," saying it caused childhood nervous conditions and eyestrain. Around that time, the then-influential Ladies Home Journal began publishing a series of anti-homework articles, stating that five hours of brain work a day was "the most we should ask of our children," and that homework was an intrusion on family life. In response, states like California passed laws abolishing homework for students under a certain age.

But, as is often the case with education, the tide eventually turned. After the Russians launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, a space race emerged, and, writes Brian Gill in the journal Theory Into Practice, "The homework problem was reconceived as part of a national crisis; the U.S. was losing the Cold War because Russian children were smarter." Many earlier laws limiting homework were abolished, and the longterm trend toward less homework came to an end.

The debate re-emerged a decade later when parents of the late '60s and '70s argued that children should be free to play and explore — similar anti-homework wellness arguments echoed nearly a century earlier. By the early-1980s, however, the pendulum swung again with the publication of A Nation at Risk , which blamed poor education for a "rising tide of mediocrity." Students needed to work harder, the report said, and one way to do this was more homework.

For the most part, this pro-homework sentiment is still going strong today, in part because of mandatory testing and continued economic concerns about the nation's competitiveness. Many believe that today's students are falling behind their peers in places like Korea and Finland and are paying more attention to Angry Birds than to ancient Babylonia.

But there are also a growing number of Stephanie Brants out there, educators and parents who believe that students are stressed and missing out on valuable family time. Students, they say, particularly younger students who have seen a rise in the amount of take-home work and already put in a six- to nine-hour "work" day, need less, not more homework.

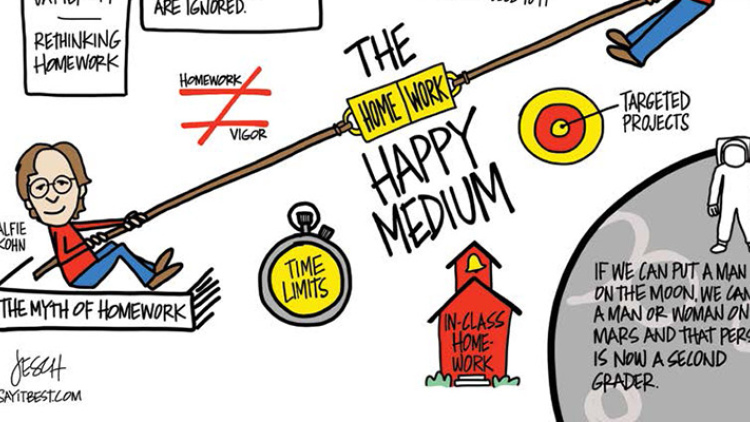

Who is right? Are students not working hard enough or is homework not working for them? Here's where the story gets a little tricky: It depends on whom you ask and what research you're looking at. As Cathy Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework , points out, "Homework has generated enough research so that a study can be found to support almost any position, as long as conflicting studies are ignored." Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth and a strong believer in eliminating all homework, writes that, "The fact that there isn't anything close to unanimity among experts belies the widespread assumption that homework helps." At best, he says, homework shows only an association, not a causal relationship, with academic achievement. In other words, it's hard to tease out how homework is really affecting test scores and grades. Did one teacher give better homework than another? Was one teacher more effective in the classroom? Do certain students test better or just try harder?

"It is difficult to separate where the effect of classroom teaching ends," Vatterott writes, "and the effect of homework begins."

Putting research aside, however, much of the current debate over homework is focused less on how homework affects academic achievement and more on time. Parents in particular have been saying that the amount of time children spend in school, especially with afterschool programs, combined with the amount of homework given — as early as kindergarten — is leaving students with little time to run around, eat dinner with their families, or even get enough sleep.

Certainly, for some parents, homework is a way to stay connected to their children's learning. But for others, homework creates a tug-of-war between parents and children, says Liz Goodenough, M.A.T.'71, creator of a documentary called Where Do the Children Play?

"Ideally homework should be about taking something home, spending a few curious and interesting moments in which children might engage with parents, and then getting that project back to school — an organizational triumph," she says. "A nag-free activity could engage family time: Ask a parent about his or her own childhood. Interview siblings."

Instead, as the authors of The Case Against Homework write, "Homework overload is turning many of us into the types of parents we never wanted to be: nags, bribers, and taskmasters."

Leslie Butchko saw it happen a few years ago when her son started sixth grade in the Santa Monica-Malibu (Calif.) United School District. She remembers him getting two to four hours of homework a night, plus weekend and vacation projects. He was overwhelmed and struggled to finish assignments, especially on nights when he also had an extracurricular activity.

"Ultimately, we felt compelled to have Bobby quit karate — he's a black belt — to allow more time for homework," she says. And then, with all of their attention focused on Bobby's homework, she and her husband started sending their youngest to his room so that Bobby could focus. "One day, my younger son gave us 15-minute coupons as a present for us to use to send him to play in the back room. … It was then that we realized there had to be something wrong with the amount of homework we were facing."

Butchko joined forces with another mother who was having similar struggles and ultimately helped get the homework policy in her district changed, limiting homework on weekends and holidays, setting time guidelines for daily homework, and broadening the definition of homework to include projects and studying for tests. As she told the school board at one meeting when the policy was first being discussed, "In closing, I just want to say that I had more free time at Harvard Law School than my son has in middle school, and that is not in the best interests of our children."

One barrier that Butchko had to overcome initially was convincing many teachers and parents that more homework doesn't necessarily equal rigor.

"Most of the parents that were against the homework policy felt that students need a large quantity of homework to prepare them for the rigorous AP classes in high school and to get them into Harvard," she says.

Stephanie Conklin, Ed.M.'06, sees this at Another Course to College, the Boston pilot school where she teaches math. "When a student is not completing [his or her] homework, parents usually are frustrated by this and agree with me that homework is an important part of their child's learning," she says.

As Timothy Jarman, Ed.M.'10, a ninth-grade English teacher at Eugene Ashley High School in Wilmington, N.C., says, "Parents think it is strange when their children are not assigned a substantial amount of homework."

That's because, writes Vatterott, in her chapter, "The Cult(ure) of Homework," the concept of homework "has become so engrained in U.S. culture that the word homework is part of the common vernacular."

These days, nightly homework is a given in American schools, writes Kohn.

"Homework isn't limited to those occasions when it seems appropriate and important. Most teachers and administrators aren't saying, 'It may be useful to do this particular project at home,'" he writes. "Rather, the point of departure seems to be, 'We've decided ahead of time that children will have to do something every night (or several times a week). … This commitment to the idea of homework in the abstract is accepted by the overwhelming majority of schools — public and private, elementary and secondary."

Brant had to confront this when she cut homework at Gaithersburg Elementary.

"A lot of my parents have this idea that homework is part of life. This is what I had to do when I was young," she says, and so, too, will our kids. "So I had to shift their thinking." She did this slowly, first by asking her teachers last year to really think about what they were sending home. And this year, in addition to forming a parent advisory group around the issue, she also holds events to answer questions.

Still, not everyone is convinced that homework as a given is a bad thing. "Any pursuit of excellence, be it in sports, the arts, or academics, requires hard work. That our culture finds it okay for kids to spend hours a day in a sport but not equal time on academics is part of the problem," wrote one pro-homework parent on the blog for the documentary Race to Nowhere , which looks at the stress American students are under. "Homework has always been an issue for parents and children. It is now and it was 20 years ago. I think when people decide to have children that it is their responsibility to educate them," wrote another.

And part of educating them, some believe, is helping them develop skills they will eventually need in adulthood. "Homework can help students develop study skills that will be of value even after they leave school," reads a publication on the U.S. Department of Education website called Homework Tips for Parents. "It can teach them that learning takes place anywhere, not just in the classroom. … It can foster positive character traits such as independence and responsibility. Homework can teach children how to manage time."

Annie Brown, Ed.M.'01, feels this is particularly critical at less affluent schools like the ones she has worked at in Boston, Cambridge, Mass., and Los Angeles as a literacy coach.

"It feels important that my students do homework because they will ultimately be competing for college placement and jobs with students who have done homework and have developed a work ethic," she says. "Also it will get them ready for independently taking responsibility for their learning, which will need to happen for them to go to college."

The problem with this thinking, writes Vatterott, is that homework becomes a way to practice being a worker.

"Which begs the question," she writes. "Is our job as educators to produce learners or workers?"

Slate magazine editor Emily Bazelon, in a piece about homework, says this makes no sense for younger kids.

"Why should we think that practicing homework in first grade will make you better at doing it in middle school?" she writes. "Doesn't the opposite seem equally plausible: that it's counterproductive to ask children to sit down and work at night before they're developmentally ready because you'll just make them tired and cross?"

Kohn writes in the American School Board Journal that this "premature exposure" to practices like homework (and sit-and-listen lessons and tests) "are clearly a bad match for younger children and of questionable value at any age." He calls it BGUTI: Better Get Used to It. "The logic here is that we have to prepare you for the bad things that are going to be done to you later … by doing them to you now."

According to a recent University of Michigan study, daily homework for six- to eight-year-olds increased on average from about 8 minutes in 1981 to 22 minutes in 2003. A review of research by Duke University Professor Harris Cooper found that for elementary school students, "the average correlation between time spent on homework and achievement … hovered around zero."

So should homework be eliminated? Of course not, say many Ed School graduates who are teaching. Not only would students not have time for essays and long projects, but also teachers would not be able to get all students to grade level or to cover critical material, says Brett Pangburn, Ed.M.'06, a sixth-grade English teacher at Excel Academy Charter School in Boston. Still, he says, homework has to be relevant.

"Kids need to practice the skills being taught in class, especially where, like the kids I teach at Excel, they are behind and need to catch up," he says. "Our results at Excel have demonstrated that kids can catch up and view themselves as in control of their academic futures, but this requires hard work, and homework is a part of it."

Ed School Professor Howard Gardner basically agrees.

"America and Americans lurch between too little homework in many of our schools to an excess of homework in our most competitive environments — Li'l Abner vs. Tiger Mother," he says. "Neither approach makes sense. Homework should build on what happens in class, consolidating skills and helping students to answer new questions."

So how can schools come to a happy medium, a way that allows teachers to cover everything they need while not overwhelming students? Conklin says she often gives online math assignments that act as labs and students have two or three days to complete them, including some in-class time. Students at Pangburn's school have a 50-minute silent period during regular school hours where homework can be started, and where teachers pull individual or small groups of students aside for tutoring, often on that night's homework. Afterschool homework clubs can help.

Some schools and districts have adapted time limits rather than nix homework completely, with the 10-minute per grade rule being the standard — 10 minutes a night for first-graders, 30 minutes for third-graders, and so on. (This remedy, however, is often met with mixed results since not all students work at the same pace.) Other schools offer an extended day that allows teachers to cover more material in school, in turn requiring fewer take-home assignments. And for others, like Stephanie Brant's elementary school in Maryland, more reading with a few targeted project assignments has been the answer.

"The routine of reading is so much more important than the routine of homework," she says. "Let's have kids reflect. You can still have the routine and you can still have your workspace, but now it's for reading. I often say to parents, if we can put a man on the moon, we can put a man or woman on Mars and that person is now a second-grader. We don't know what skills that person will need. At the end of the day, we have to feel confident that we're giving them something they can use on Mars."

Read a January 2014 update.

Homework Policy Still Going Strong

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Commencement Marshal Sarah Fiarman: The Principal of the Matter

Making Math “Almost Fun”

Alum develops curriculum to entice reluctant math learners

Reshaping Teacher Licensure: Lessons from the Pandemic

Olivia Chi, Ed.M.'17, Ph.D.'20, discusses the ongoing efforts to ensure the quality and stability of the teaching workforce

Does homework really work?

by: Leslie Crawford | Updated: December 12, 2023

Print article

You know the drill. It’s 10:15 p.m., and the cardboard-and-toothpick Golden Gate Bridge is collapsing. The pages of polynomials have been abandoned. The paper on the Battle of Waterloo seems to have frozen in time with Napoleon lingering eternally over his breakfast at Le Caillou. Then come the tears and tantrums — while we parents wonder, Does the gain merit all this pain? Is this just too much homework?

However the drama unfolds night after night, year after year, most parents hold on to the hope that homework (after soccer games, dinner, flute practice, and, oh yes, that childhood pastime of yore known as playing) advances their children academically.

But what does homework really do for kids? Is the forest’s worth of book reports and math and spelling sheets the average American student completes in their 12 years of primary schooling making a difference? Or is it just busywork?

Homework haterz

Whether or not homework helps, or even hurts, depends on who you ask. If you ask my 12-year-old son, Sam, he’ll say, “Homework doesn’t help anything. It makes kids stressed-out and tired and makes them hate school more.”

Nothing more than common kid bellyaching?

Maybe, but in the fractious field of homework studies, it’s worth noting that Sam’s sentiments nicely synopsize one side of the ivory tower debate. Books like The End of Homework , The Homework Myth , and The Case Against Homework the film Race to Nowhere , and the anguished parent essay “ My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me ” make the case that homework, by taking away precious family time and putting kids under unneeded pressure, is an ineffective way to help children become better learners and thinkers.

One Canadian couple took their homework apostasy all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. After arguing that there was no evidence that it improved academic performance, they won a ruling that exempted their two children from all homework.

So what’s the real relationship between homework and academic achievement?

How much is too much?

To answer this question, researchers have been doing their homework on homework, conducting and examining hundreds of studies. Chris Drew Ph.D., founder and editor at The Helpful Professor recently compiled multiple statistics revealing the folly of today’s after-school busy work. Does any of the data he listed below ring true for you?

• 45 percent of parents think homework is too easy for their child, primarily because it is geared to the lowest standard under the Common Core State Standards .

• 74 percent of students say homework is a source of stress , defined as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss, and stomach problems.

• Students in high-performing high schools spend an average of 3.1 hours a night on homework , even though 1 to 2 hours is the optimal duration, according to a peer-reviewed study .

Not included in the list above is the fact many kids have to abandon activities they love — like sports and clubs — because homework deprives them of the needed time to enjoy themselves with other pursuits.

Conversely, The Helpful Professor does list a few pros of homework, noting it teaches discipline and time management, and helps parents know what’s being taught in the class.

The oft-bandied rule on homework quantity — 10 minutes a night per grade (starting from between 10 to 20 minutes in first grade) — is listed on the National Education Association’s website and the National Parent Teacher Association’s website , but few schools follow this rule.

Do you think your child is doing excessive homework? Harris Cooper Ph.D., author of a meta-study on homework , recommends talking with the teacher. “Often there is a miscommunication about the goals of homework assignments,” he says. “What appears to be problematic for kids, why they are doing an assignment, can be cleared up with a conversation.” Also, Cooper suggests taking a careful look at how your child is doing the assignments. It may seem like they’re taking two hours, but maybe your child is wandering off frequently to get a snack or getting distracted.

Less is often more

If your child is dutifully doing their work but still burning the midnight oil, it’s worth intervening to make sure your child gets enough sleep. A 2012 study of 535 high school students found that proper sleep may be far more essential to brain and body development.

For elementary school-age children, Cooper’s research at Duke University shows there is no measurable academic advantage to homework. For middle-schoolers, Cooper found there is a direct correlation between homework and achievement if assignments last between one to two hours per night. After two hours, however, achievement doesn’t improve. For high schoolers, Cooper’s research suggests that two hours per night is optimal. If teens have more than two hours of homework a night, their academic success flatlines. But less is not better. The average high school student doing homework outperformed 69 percent of the students in a class with no homework.

Many schools are starting to act on this research. A Florida superintendent abolished homework in her 42,000 student district, replacing it with 20 minutes of nightly reading. She attributed her decision to “ solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students .”

More family time

A 2020 survey by Crayola Experience reports 82 percent of children complain they don’t have enough quality time with their parents. Homework deserves much of the blame. “Kids should have a chance to just be kids and do things they enjoy, particularly after spending six hours a day in school,” says Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth . “It’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.”

By far, the best replacement for homework — for both parents and children — is bonding, relaxing time together.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How families of color can fight for fair discipline in school

Dealing with teacher bias

The most important school data families of color need to consider

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

Does Homework Work?

There's absolutely no proof that homework helps elementary school pupils learn more or have greater academic success. In fact...when children are asked to do too much nightly work, just the opposite has been found. And study after study shows that homework is not much more beneficial in middle school either. Even in high school, where there can be benefits, they start to decline as soon as kids are overloaded.

Most kids hate homework. They dread it, groan about it, put off doing it as long as possible. It may be the single most reliable extinguisher of the flame of curiosity.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Develop a Strong Work Ethic

- Tutti Taygerly

Hiring managers want to see your motivation, can-do attitude, and dedication.

In our early career years, it can be challenging to figure out what behaviors are and are not acceptable in different professional environments. Employers are now expecting more of entry-level workers and they want to see that you have good work ethic. So what is work ethic?

- Work ethic refers to a set of moral principles, values, and attitudes around how to act at work. It often surrounds what behaviors are commonly acceptable and appropriate (or not).

- Qualities like reliability, productivity, ownership and team support all demonstrate professional integrity, or a strong commitment to ethical behavior at work. In contrast, low-quality work, tardiness, or lack of attention to details demonstrates bad work ethic.

- If you’re new to the workplace, a good way to start is by observing. Pay attention to how your coworkers behave in meetings to gain a better understanding of their “etiquette,” as well as the communication styles of different people and teams. Another essential part of building good work ethic is adopting a “do it like you own it” attitude. You can do this by being proactive in small, but powerful, ways.

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

Have you ever wondered about how to behave appropriately at work? Throughout your career, and especially in the early years, it’s challenging to figure out what behaviors and attitudes are and are not acceptable in different professional environments. The more you traverse companies and industries, the clearer your understanding will become. When you’re just starting out, though, it can be hard to pin down these behaviors.

- Tutti Taygerly is an executive coach and speaker with 20+ years of product design experience in Silicon Valley. Her book Make Space to Lead: Break Patterns to Find Flow and Focus on What Matters Most (Taygerly Labs, 2021) shows high achievers how to reframe their relationship to work.

Partner Center

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

Is Homework Necessary? Education Inequity and Its Impact on Students

The Problem with Homework: It Highlights Inequalities

How much homework is too much homework, when does homework actually help, negative effects of homework for students, how teachers can help.

Schools are getting rid of homework from Essex, Mass., to Los Angeles, Calif. Although the no-homework trend may sound alarming, especially to parents dreaming of their child’s acceptance to Harvard, Stanford or Yale, there is mounting evidence that eliminating homework in grade school may actually have great benefits , especially with regard to educational equity.

In fact, while the push to eliminate homework may come as a surprise to many adults, the debate is not new . Parents and educators have been talking about this subject for the last century, so that the educational pendulum continues to swing back and forth between the need for homework and the need to eliminate homework.

One of the most pressing talking points around homework is how it disproportionately affects students from less affluent families. The American Psychological Association (APA) explained:

“Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs.”

[RELATED] How to Advance Your Career: A Guide for Educators >>

While students growing up in more affluent areas are likely playing sports, participating in other recreational activities after school, or receiving additional tutoring, children in disadvantaged areas are more likely headed to work after school, taking care of siblings while their parents work or dealing with an unstable home life. Adding homework into the mix is one more thing to deal with — and if the student is struggling, the task of completing homework can be too much to consider at the end of an already long school day.

While all students may groan at the mention of homework, it may be more than just a nuisance for poor and disadvantaged children, instead becoming another burden to carry and contend with.

Beyond the logistical issues, homework can negatively impact physical health and stress — and once again this may be a more significant problem among economically disadvantaged youth who typically already have a higher stress level than peers from more financially stable families .

Yet, today, it is not just the disadvantaged who suffer from the stressors that homework inflicts. A 2014 CNN article, “Is Homework Making Your Child Sick?” , covered the issue of extreme pressure placed on children of the affluent. The article looked at the results of a study surveying more than 4,300 students from 10 high-performing public and private high schools in upper-middle-class California communities.

“Their findings were troubling: Research showed that excessive homework is associated with high stress levels, physical health problems and lack of balance in children’s lives; 56% of the students in the study cited homework as a primary stressor in their lives,” according to the CNN story. “That children growing up in poverty are at-risk for a number of ailments is both intuitive and well-supported by research. More difficult to believe is the growing consensus that children on the other end of the spectrum, children raised in affluence, may also be at risk.”

When it comes to health and stress it is clear that excessive homework, for children at both ends of the spectrum, can be damaging. Which begs the question, how much homework is too much?

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association recommend that students spend 10 minutes per grade level per night on homework . That means that first graders should spend 10 minutes on homework, second graders 20 minutes and so on. But a study published by The American Journal of Family Therapy found that students are getting much more than that.

While 10 minutes per day doesn’t sound like much, that quickly adds up to an hour per night by sixth grade. The National Center for Education Statistics found that high school students get an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, a figure that is much too high according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). It is also to be noted that this figure does not take into consideration the needs of underprivileged student populations.

In a study conducted by the OECD it was found that “after around four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested in homework has a negligible impact on performance .” That means that by asking our children to put in an hour or more per day of dedicated homework time, we are not only not helping them, but — according to the aforementioned studies — we are hurting them, both physically and emotionally.

What’s more is that homework is, as the name implies, to be completed at home, after a full day of learning that is typically six to seven hours long with breaks and lunch included. However, a study by the APA on how people develop expertise found that elite musicians, scientists and athletes do their most productive work for about only four hours per day. Similarly, companies like Tower Paddle Boards are experimenting with a five-hour workday, under the assumption that people are not able to be truly productive for much longer than that. CEO Stephan Aarstol told CNBC that he believes most Americans only get about two to three hours of work done in an eight-hour day.

In the scope of world history, homework is a fairly new construct in the U.S. Students of all ages have been receiving work to complete at home for centuries, but it was educational reformer Horace Mann who first brought the concept to America from Prussia.

Since then, homework’s popularity has ebbed and flowed in the court of public opinion. In the 1930s, it was considered child labor (as, ironically, it compromised children’s ability to do chores at home). Then, in the 1950s, implementing mandatory homework was hailed as a way to ensure America’s youth were always one step ahead of Soviet children during the Cold War. Homework was formally mandated as a tool for boosting educational quality in 1986 by the U.S. Department of Education, and has remained in common practice ever since.

School work assigned and completed outside of school hours is not without its benefits. Numerous studies have shown that regular homework has a hand in improving student performance and connecting students to their learning. When reviewing these studies, take them with a grain of salt; there are strong arguments for both sides, and only you will know which solution is best for your students or school.

Homework improves student achievement.

- Source: The High School Journal, “ When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math ,” 2012.

- Source: IZA.org, “ Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement? ,” 2014. **Note: Study sample comprised only high school boys.

Homework helps reinforce classroom learning.

- Source: “ Debunk This: People Remember 10 Percent of What They Read ,” 2015.

Homework helps students develop good study habits and life skills.

- Sources: The Repository @ St. Cloud State, “ Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement ,” 2017; Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

- Source: Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

Homework allows parents to be involved with their children’s learning.

- Parents can see what their children are learning and working on in school every day.

- Parents can participate in their children’s learning by guiding them through homework assignments and reinforcing positive study and research habits.

- Homework observation and participation can help parents understand their children’s academic strengths and weaknesses, and even identify possible learning difficulties.

- Source: Phys.org, “ Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework ,” 2018.

While some amount of homework may help students connect to their learning and enhance their in-class performance, too much homework can have damaging effects.

Students with too much homework have elevated stress levels.

- Source: USA Today, “ Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In ,” 2021.

- Source: Stanford University, “ Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework ,” 2014.

Students with too much homework may be tempted to cheat.

- Source: The Chronicle of Higher Education, “ High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame ,” 2010.

- Source: The American Journal of Family Therapy, “ Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background ,” 2015.

Homework highlights digital inequity.

- Sources: NEAToday.org, “ The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’ ,” 2016; CNET.com, “ The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind ,” 2021.

- Source: Investopedia, “ Digital Divide ,” 2022; International Journal of Education and Social Science, “ Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework ,” 2015.

- Source: World Economic Forum, “ COVID-19 exposed the digital divide. Here’s how we can close it ,” 2021.

Homework does not help younger students.

- Source: Review of Educational Research, “ Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003 ,” 2006.

To help students find the right balance and succeed, teachers and educators must start the homework conversation, both internally at their school and with parents. But in order to successfully advocate on behalf of students, teachers must be well educated on the subject, fully understanding the research and the outcomes that can be achieved by eliminating or reducing the homework burden. There is a plethora of research and writing on the subject for those interested in self-study.

For teachers looking for a more in-depth approach or for educators with a keen interest in educational equity, formal education may be the best route. If this latter option sounds appealing, there are now many reputable schools offering online master of education degree programs to help educators balance the demands of work and family life while furthering their education in the quest to help others.

YOU’RE INVITED! Watch Free Webinar on USD’s Online MEd Program >>

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Top 11 Reasons to get Your Master of Education Degree

Free 22-page Book

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Advertisement

Homework and Children in Grades 3–6: Purpose, Policy and Non-Academic Impact

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 January 2021

- Volume 50 , pages 631–651, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Melissa Holland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8349-7168 1 ,

- McKenzie Courtney 2 ,

- James Vergara 3 ,

- Danielle McIntyre 4 ,

- Samantha Nix 5 ,

- Allison Marion 6 &

- Gagan Shergill 1

8 Citations

127 Altmetric

16 Mentions

Explore all metrics

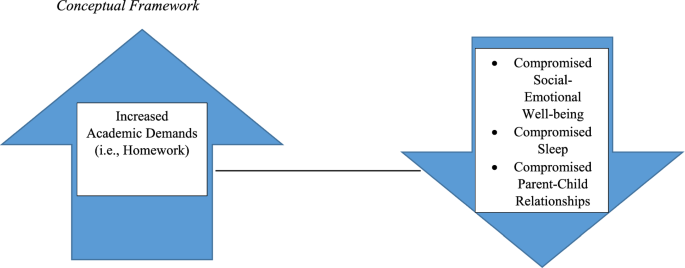

Increasing academic demands, including larger amounts of assigned homework, is correlated with various challenges for children. While homework stress in middle and high school has been studied, research evidence is scant concerning the effects of homework on elementary-aged children.

The objective of this study was to understand rater perception of the purpose of homework, the existence of homework policy, and the relationship, if any, between homework and the emotional health, sleep habits, and parent–child relationships for children in grades 3–6.

Survey research was conducted in the schools examining student ( n = 397), parent ( n = 442), and teacher ( n = 28) perception of homework, including purpose, existing policy, and the childrens’ social and emotional well-being.

Preliminary findings from teacher, parent, and student surveys suggest the presence of modest impact of homework in the area of emotional health (namely, student report of boredom and frustration ), parent–child relationships (with over 25% of the parent and child samples reporting homework always or often interferes with family time and creates a power struggle ), and sleep (36.8% of the children surveyed reported they sometimes get less sleep) in grades 3–6. Additionally, findings suggest misperceptions surrounding the existence of homework policies among parents and teachers, the reasons teachers cite assigning homework, and a disconnect between child-reported and teacher reported emotional impact of homework.

Conclusions

Preliminary findings suggest homework modestly impacts child well-being in various domains in grades 3–6, including sleep, emotional health, and parent/child relationships. School districts, educators, and parents must continue to advocate for evidence-based homework policies that support children’s overall well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Understanding the Quality of Effective Homework

Relationships between perceived parental involvement in homework, student homework behaviors, and academic achievement: differences among elementary, junior high, and high school students.

Collaboration between School and Home to Improve Subjective Well-being: A New Chinese Children’s Subjective Well-being Scale

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children’s social-emotional health is moving to the forefront of attention in schools, as depression, anxiety, and suicide rates are on the rise (Bitsko et al. 2018 ; Child Mind Institute 2016 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Perou et al. 2013 ). This comes at a time when there are also intense academic demands, including an increased focus on academic achievement via grades, standardized test scores, and larger amounts of assigned homework (Pope 2010 ). This interplay between the rise in anxiety and depression and scholastic demands has been postulated upon frequently in the literature, and though some research has looked at homework stress as it relates to middle and high school students (Cech 2008 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Kackar et al. 2011 ; Katz et al. 2012 ), research evidence is scant as to the effects of academic stress on the social and emotional health of elementary children.

Literature Review

The following review of the literature highlights areas that are most pertinent to the child, including homework as it relates to achievement, the achievement gap, mental health, sleep, and parent–child relationships. Areas of educational policy, teacher training, homework policy, and parent-teacher communication around homework are also explored.

Homework and Achievement

With the authorization of No Child Left Behind and the Common Core State Standards, teachers have felt added pressures to keep up with the tougher standards movement (Tokarski 2011 ). Additionally, teachers report homework is necessary in order to complete state-mandated material (Holte 2015 ). Misconceptions on the effectiveness of homework and student achievement have led many teachers to increase the amount of homework assigned. However, there has been little evidence to support this trend. In fact, there is a significant body of research demonstrating the lack of correlation between homework and student success, particularly at the elementary level. In a meta-analysis examining homework, grades, and standardized test scores, Cooper et al. ( 2006 ) found little correlation between the amount of homework assigned and achievement in elementary school, and only a moderate correlation in middle school. In third grade and below, there was a negative correlation found between the variables ( r = − 0.04). Other studies, too, have evidenced no relationship, and even a negative relationship in some grades, between the amount of time spent on homework and academic achievement (Horsley and Walker 2013 ; Trautwein and Köller 2003 ). High levels of homework in competitive high schools were found to hinder learning, full academic engagement, and well-being (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Ironically, research suggests that reducing academic pressures can actually increase children’s academic success and cognitive abilities (American Psychological Association [APA] 2014 ).

International comparison studies of achievement show that national achievement is higher in countries that assign less homework (Baines and Slutsky 2009 ; Güven and Akçay 2019 ). In fact, in a recent international study conducted by Güven and Akçay ( 2019 ), there was no relationship found between math homework frequency and student achievement for fourth grade students in the majority of the countries studied, including the United States. Similarly, additional homework in science, English, and history was found to have little to no impact on respective test scores in later grades (Eren and Henderson 2011 ). In the 2015 “Programme of International Student Assessment” results, Korea and Finland are ranked among the top countries in reading, mathematics, and writing, yet these countries are among those that assign the least amount of homework (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] 2016 ).

Homework and Mental Wellness

Academic stress has been found to play a role in the mental well-being of children. In a study conducted by Conner et al. ( 2009 ), students reported feeling overwhelmed and burdened by their exceeding homework loads, even when they viewed homework as meaningful. Academic stress, specifically the amount of homework assigned, has been identified as a common risk factor for children’s increased anxiety levels (APA 2009 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Leung et al. 2010 ), in addition to somatic complaints and sleep disturbance (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Stress also negatively impacts cognition, including memory, executive functioning, motor skills, and immune response (Westheimer et al. 2011 ). Consequently, excessive stress impacts one’s ability to think critically, recall information, and make decisions (Carrion and Wong 2012 ).

Homework and Sleep

Sleep, including quantity and quality, is one life domain commonly impacted by homework and stress. Zhou et al. ( 2015 ) analyzed the prevalence of unhealthy sleep behaviors in school-aged children, with findings suggesting that staying up late to study was one of the leading risk factors most associated with severe tiredness and depression. According to the National Sleep Foundation ( 2017 ), the recommended amount of sleep for elementary school-aged children is 9 – 11 h per night; however, approximately 70% of youth do not get these recommended hours. According to the MetLife American Teacher Survey ( 2008 ), elementary-aged children also acknowledge lack of sleep. Perfect et al. ( 2014 ) found that sleep problems predict lower grades and negative student attitudes toward teachers and school. Eide and Showalter ( 2012 ) conducted a national study that examined the relationship between optimum amounts of sleep and student performance on standardized tests, with results indicating significant correlations ( r = 0.285–0.593) between sleep and student performance. Therefore, sleep is not only impacted by academic stress and homework, but lack of sleep can also impact academic functioning.

Homework and the Achievement Gap

Homework creates increasing achievement variability among privileged learners and those who are not. For example, learners with more resources, increased parental education, and family support are likely to have higher achievement on homework (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ; Moore et al. 2018 ; Ndebele 2015 ; OECD 2016 ). Learners coming from a lower socioeconomic status may not have access to quiet, well-lit environments, computers, and books necessary to complete their homework (Cooper 2001 ; Kralovec and Buell 2000 ). Additionally, many homework assignments require materials that may be limited for some families, including supplies for projects, technology, and transportation. Based on the research to date, the phrase “the homework gap” has been coined to describe those learners who lack the resources necessary to complete assigned homework (Moore et al. 2018 ).

Parent–Teacher Communication Around Homework

Communication between caregivers and teachers is essential. Unfortunately, research suggests parents and teachers often have limited communication regarding homework assignments. Markow et al. ( 2007 ) found most parents (73%) report communicating with their child’s teacher regarding homework assignments less than once a month. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) indicated children in primary grades spend substantially more time on homework than predicted by educators. For example, they found first grade students had three times more homework than the National Education Association’s recommendation of up to 20 min of homework per night for first graders. While the same homework assignment may take some learners 30 min to complete, it may take others up to 2 or 3 h. However, until parents and teachers have better communication around homework, including time completion and learning styles for individual learners, these misperceptions and disparities will likely persist.

Parent–Child Relationships and Homework

Trautwein et al. ( 2009 ) defined homework as a “double-edged sword” when it comes to the parent–child relationship. While some parental support can be construed as beneficial, parental support can also be experienced as intrusive or detrimental. When examining parental homework styles, a controlling approach was negatively associated with student effort and emotions toward homework (Trautwein et al. 2009 ). Research suggests that homework is a primary source of stress, power struggle, and disagreement among families (Cameron and Bartel 2009 ), with many families struggling with nightly homework battles, including serious arguments between parents and their children over homework (Bennett and Kalish 2006 ). Often, parents are not only held accountable for monitoring homework completion, they may also be accountable for teaching, re-teaching, and providing materials. This is particularly challenging due to the economic and educational diversity of families. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) found that as parents’ personal perceptions of their abilities to assist their children with homework declined, family-related stressors increased.

Teacher Training

As homework plays a significant role in today’s public education system, an assumption would be made that teachers are trained to design homework tasks to promote learning. However, only 12% of teacher training programs prepare teachers for using homework as an assessment tool (Greenberg and Walsh 2012 ), and only one out of 300 teachers reported ever taking a course regarding homework during their training (Bennett and Kalish 2006 ). The lack of training with regard to homework is evidenced by the differences in teachers’ perspectives. According to the MetLife American Teacher Survey ( 2008 ), less experienced teachers (i.e., those with 5 years or less years of experience) are less likely to to believe homework is important and that homework supports student learning compared to more experienced teachers (i.e., those with 21 plus years of experience). There is no universal system or rule regarding homework; consequently, homework practices reflect individual teacher beliefs and school philosophies.

Educational and Homework Policy

Policy implementation occurs on a daily basis in public schools and classrooms. While some policies are made at the federal level, states, counties, school districts, and even individual school sites often manage education policy (Mullis et al. 2012 ). Thus, educators are left with the responsibility to implement multi-level policies, such as curriculum selection, curriculum standards, and disability policy (Rigby et al. 2016 ). Despite educational reforms occurring on an almost daily basis, little has been initiated with regard to homework policies and practices.

To date, few schools provide specific guidelines regarding homework practices. District policies that do exist are not typically driven by research, using vague terminology regarding the quantity and quality of assignments. Greater variations among homework practices exist when comparing schools in the private sector. For example, Montessori education practices the philosophy of no examinations and no homework for students aged 3–18 (O’Donnell 2013 ). Abeles and Rubenstein ( 2015 ) note that many public school districts advocate for the premise of 10 min of homework per night per grade level. However, there is no research supporting this premise and the guideline fails to recognize that time spent on homework varies based on the individual student. Sartain et al. ( 2015 ) analyzed and evaluated homework policies of multiple school districts, finding the policies examined were outdated, vague, and not student-focused.

The reasons cited for homework assignment, as identified by teachers, are varied, such as enhancing academic achievement through practice or teaching self-discipline. However, not all types of practice are equally effective, particularly if the student is practicing the skill incorrectly (Dean et al. 2012 ; Trautwein et al. 2009 ). The practice of reading is one of the only assignments consistently supported by research to be associated with increased academic achievement (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ). Current literature supports 15–20 min of daily allocated time for reading practice (Reutzel and Juth 2017 ). Additionally, research supports project-based learning to deepen learners’ practice and understanding of academic material (Williams 2018 ).

Research also shows that homework only teaches responsibility and self-discipline when parents have that goal in mind and systematically structure and supervise homework (Kralovec and Buell 2000 ). Non-academic activities, such as participating in chores (University of Minnesota 2002 ) and sports (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ) were found to be greater predictors of later success and effective problem-solving.

Consistent with the pre-existing research literature, the following hypotheses are offered:

Homework will have some negative correlation with children’s social-emotional well-being.

The purposes cited for the assignment of homework will be varied between parents and teachers.

Schools will lack well-formulated and understood homework policies.

Homework will have some negative correlation with children’s sleep and parent–child relationships.

This quantitative study explored, via perception-based survey research, the social and emotional health of elementary children in grades 3 – 6 and the scholastic pressures they face, namely homework. The researchers implemented newly developed questionnaires addressing student, teacher, and parent perspectives on homework and on children’s social-emotional well-being. Researchers also examined perspectives on the purpose of homework, the existence of school homework policies, and the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and family relationships. Given the dearth of prior research in this area, a major goal of this study was to explore associations between academic demands and child well-being with sufficient breadth to allow for identification of potential associations that may be examined more thoroughly by future research. These preliminary associations and item-response tendencies can serve as foundation for future studies with causal, experimental, or more psychometrically focused designs. A conceptual framework for this study is offered in Fig. 1 .

Conceptual framework

Research Questions

What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s social-emotional well-being across teachers, parents, and the children themselves?

What are the primary purposes of homework according to parents and teachers?

How many schools have homework policies, and of those, how many parents and teachers know what the policy is?

What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and parent–child relationships?

The present quantitative descriptive study is based on researcher developed instruments designed to explore the perceptions of children, teachers and parents on homework and its impact on social-emotional well-being. The use of previously untested instruments and a convenience sample preclude any causal interpretations being drawn from our results. This study is primarily an initial foray into the sparsely researched area of the relationship of homework and social-emotional health, examining an elementary school sample and incorporating multiple perspectives of the parents, teachers, and the children themselves.

Participants

The participants in this study were children in six Northern California schools in grades third through sixth ( n = 397), their parents ( n = 442), and their teachers ( n = 28). The mean grade among children was 4.56 (minimum third grade/maximum sixth grade) with a mean age of 9.97 (minimum 8 years old/maximum 12 years old). Approximately 54% of the children were male and 45% were female, with White being the most common ethnicity (61%), followed by Hispanic (30%), and Pacific Islander (12%). Subjects were able to mark more than one ethnicity. Detailed participant demographics are available upon request.

Instruments

The instruments used in this research include newly developed student, parent, and teacher surveys. The research team formulated a number of survey items that, based on existing research and their own professional experience in the schools, have high face validity in measuring workload, policies, and attitudes surrounding homework. Further psychometric development of these surveys and ascertation of construct and content validity is warranted, with the first step being their use in this initial perception-based study. Each of the surveys, developed specifically for this study, are discussed below.

Student Survey

The Student Survey is a 15-item questionnaire wherein the child was asked closed- and open-ended questions regarding their perspectives on homework, including how homework makes them feel.

Parent Survey

The Parent Survey is a 23-item questionnaire wherein the children’s parents were asked to respond to items regarding their perspectives on their child’s homework, as well as their child’s social-emotional health. Additionally, parents were asked whether their child’s school has a homework policy and, if so, if they know what that policy specifies.

Teacher Survey

The Teacher Survey is a 22-item questionnaire wherein the children’s teacher was asked to respond to items regarding their perspectives of the primary purposes of homework, as well as the impact of homework on children’s social-emotional health. Additionally, teachers were asked whether their school has a homework policy and, if so, what that policy specifies.

Data was collected by the researchers after following Institutional Review Board procedures from the sponsoring university. School district approval was obtained by the lead researcher. Upon district approval, individual school approval was requested by the researchers by contacting site principals, after which, teachers of grades 3 – 6 at those schools were asked to voluntarily participate. Each participating teacher was provided a packet including the following: a manila envelope, Teacher Instructions, Administration Guide, Teacher Survey, Parent Packet, and Student Survey. Surveys and classrooms were de-identified via number assignment. Teachers then distributed the Parent Packet to each child’s guardian, which included the Parent Consent and Parent Survey, corresponding with the child’s assigned number. A coded envelope was also enclosed for parents/guardians to return their completed consent form and survey, if they agreed to participate. The Parent Consent form detailed the purpose of the research, the benefits and risks of participating in the research, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of completing the survey. Parents who completed the consent form and survey sent the completed materials in the enclosed envelope, sealed, to their child’s teacher. After obtaining returned envelopes, with parent consent, teachers were instructed to administer the corresponding numbered survey to the children during a class period. Teachers were also asked to complete their Teacher Survey. All completed materials were to be placed in envelopes provided to each teacher and returned to the researchers once data was collected.

Analysis of Data

This descriptive and quantitative research design utilized the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) to analyze data. The researchers developed coding keys for the parent, teacher, and student surveys to facilitate data entry into SPSS. Items were also coded based on the type of data, such as nominal or ordinal, and qualitative responses were coded and translated where applicable and transcribed onto a response sheet. Some variables were transformed for more accurate comparison across raters. Parent, teacher, and student ratings were analyzed, and frequency counts and percentages were generated for each item. Items were then compared across and within rater groups to explore the research questions. The data analysis of this study is primarily descriptive and exploratory, not seeking to imply causal relationships between variables. Survey item response results associated with each research questionnaire are summarized in their respective sections below.

The first research question investigated in this study was: “What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s social-emotional well-being across teachers, parents, and children?” For this question the examiners looked at children’s responses to how homework makes them feel from a list of feelings. As demonstrated in Table 1 , approximately 44% of children feel “Bored” and about 25% feel “Annoyed” and “Frustrated” toward homework. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 1 . Similar to the student survey, parents also responded to a question regarding their child’s emotional experience surrounding homework. Based on parent reports, approximately 40% of parents perceive their child as “Frustrated” and about 37% acknowledge their child feeling “Stress/Anxiety.” Conversely, about 37% also report their child feels “Competence.” These results are reported in Table 1 .

Additionally, parents and teachers both responded to the question, “How does homework affect your student’s social and emotional health?” One notable finding from parent and teacher reports is that nearly half of both parents and teachers reported homework has “No Effect” on children’s social and emotional health. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 2 .

The second research question investigated in this study was: “What are parent and teacher perspectives on the primary purposes of homework?” For this question the examiners looked at three specific questions across parent and teacher surveys. Parents responded to the questions, “Does homework relate to your child’s learning?” and “How often is homework busy work?” While the majority of parents reported homework “Always” (45%) or “Often” (39%) relates to their child’s learning, parents also feel homework is “Often” (29%) busy work. The corresponding frequencies and percentages are summarized in Table 3 . Additionally, teachers were asked, “What are the primary reasons you assign homework?” The primary purposes of homework according to the teachers in this sample are “Skill Practice” (82%), “Develop Work Ethic” (61%), and “Teach Independence and Responsibility” (50%). The frequencies and percentages of teacher responses are displayed in Table 4 . Notably, on this survey item, teachers were instructed to choose one response (item), but the majority of teachers chose multiple items. This suggests teachers perceive themselves as assigning homework for a variety of reasons.

The third research question investigated was, “How many schools have homework policies, and of those, how many parents and teachers know what the policy is?” For this question the examiners analyzed parent and teacher responses to the question, “Does your school have a homework policy?” Frequencies and percentages are displayed in Table 5 . Notably, only two out of the six schools included in this study had homework policies. Results indicate that both parents and teachers are uncertain regarding whether or not their school had a homework policy.

The fourth research question investigated was, “What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and parent–child relationships?” Children were asked if they get less sleep because of homework and parents were asked if their child gets less sleep because of homework. Finally, teachers were asked about the impact of sleep on academic performance. Frequencies and percentages of student, parent, and teacher data is reported in Table 6 . Results indicate disagreement among parents and children on the impact of homework on sleep. While the majority of parents do not feel their child gets less sleep because of homework (77%), approximately 37% of children report sometimes getting less sleep because of homework. On the other hand, teachers acknowledge the importance of sleep in relation to academic performance, as nearly 93% of teachers report sleep always or often impacts academic performance.

To investigate the perceived impact of homework on the parent–child relationship, parents were asked “How does homework impact your child’s relationships?” Almost 30% of parents report homework “Brings us Together”; however, 24% report homework “Creates a Power Struggle” and nearly 18% report homework “Interferes with Family Time.” Additionally, parents and children were both asked to report if homework gets in the way of family time. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 7 . Data was further analyzed to explore potentially significant differences between parents and children on this perception as described below.

In order to prepare for analysis of significant differences between parent and child perceptions regarding homework and family time, a Levene’s test for equality of variances was conducted. Results of the Levene’s test showed that equal variances could not be assumed, and results should be interpreted with caution. Despite this, a difference in mean responses on a Likert-type scale (where higher scores equal greater perceived interference with family time) indicate a disparity in parent ( M = 2.95, SD = 0.88) and child ( M = 2.77, SD = 0.99) perceptions, t (785) = 2.65, p = 0.008. Results suggest that children were more likely to feel that homework interferes with family time than their parents. However, follow up testing where equal variances can be assumed is warranted upon further data collection.

The purpose of this research was to explore perceptions of homework by parents, children, and teachers of grades 3–6, including how homework relates to child well-being, awareness of school homework policies and the perceived purpose of homework. A discussion of the results as it relates to each research question is explored.

Perceived Impact of Homework on Children’s Social-Emotional Well-Being Across Teachers, Parents, and Students

According to self-report survey data, children in grades 3–6 reported that completing homework at home generates various feelings. The majority of responses indicated that children felt uncomfortable emotions such as bored, annoyed, and frustrated; however, a subset of children also reported feeling smart when completing homework. While parent and teacher responses suggest parents and teachers do not feel homework affects children’s social-emotional health, children reported that homework does affect how they feel. Specifically, many children in this study reported experiencing feelings of boredom and frustration when thinking about completing homework at home. If the purpose of homework is to enhance children’s engagement in their learning outside of school, educators must re-evaluate homework assignments to align with best practices, as indicated by the researchers Dean et al. ( 2012 ), Vatterott ( 2018 ), and Sartain et al. ( 2015 ). Specifically, educators should consider effects of the amount and type of homework assigned, balancing the goal of increased practice and learning with potential effects on children’s social-emotional health. Future research could incorporate a control group and/or test scores or other measures of academic achievement to isolate and better understand the relationships between homework, health, and scholastic achievement.

According to parent survey data, the perceived effects of homework on their child’s social and emotional well-being appear strikingly different compared to student perceptions. Nearly half of the parents who participated in the survey reported that homework does not impact their child’s social-emotional health. Additionally, more parents indicated that homework had a positive effect on child well-being compared to a negative one. However, parents also acknowledge that homework generates negative emotions such as frustration, stress and anxiety in their children.

Teacher data indicates that, overall, teachers do not appear to see a negative impact on their students’ social-emotional health from homework. Similar to parent responses, nearly half of teachers report that homework has no impact on children’s social-emotional health, and almost one third of teachers reported a positive effect. These results are consistent with related research which indicates that teachers often believe that homework has positive impacts on student development, such as developing good study habits and a sense of responsibility (Bembenutty 2011 ). It should also be noted, not a single teacher reported the belief that homework negatively impacts children’s’ social and emotional well-being, which indicates clear discrepancies between teachers’ perceptions and children’s feelings. Further research is warranted to explore and clarify these discrepancies.

Primary Purposes of Homework According to Teachers and Parents

Results from this study suggest that the majority of parents believe that homework relates and contributes to their child’s learning. This finding supports prior research which indicates that parents often believe that homework has long-term positive effects and builds academic competencies in students (Cooper et al. 2006 ). Notably, however, nearly one third of parents also indicate that homework is often given as busy work by teachers. Teachers reported that they assigned homework to develop students’ academic skills, work ethic, and teach students responsibility and promote independence. While teachers appear to have good intentions regarding the purpose of homework, research suggests that homework is not an effective nor recommended practice to achieve these goals. Household chores, cooking, volunteer experiences, and sports may create more conducive learning opportunities wherein children acquire work ethic, responsibility, independence, and problem-solving skills (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ; University of Minnesota 2002 ). Educators should leverage the use of homework in tandem with other student life experiences to best foster both academic achievement and positive youth development more broadly.

Homework Policies

As evident from parent responses, the majority of parents are unaware if their child’s school has a homework policy and many teachers are also uncertain as to whether their school provides restrictions or guidelines for homework (e.g., amount, type, and purpose). Upon contacting school principals, it was determined that only two of the six schools have a school-wide homework policy. Current data indicates the professionals responsible for assigning homework appear to be unclear about whether their school has policies for homework. Additionally, there appears to be a disconnect between parents and teachers regarding whether homework policies do exist among the sampled schools. The research in the current study is consistent with previous research indicating that policies, if they do exist, are often vague and not communicated clearly to parents (Sartain et al. 2015 ). This study suggests that homework policies in these districts require improved communication between administrators, teachers, and parents.

Perceived Impact of Homework on Children’s Sleep and Parent–Child Relationships

Regarding the importance of sleep on academic performance, nearly all of the teachers included in this study acknowledged the impact that sleep has on academic performance. There was disagreement among children and parents on the actual impact that homework has on children’s sleep. Over one third of children report that homework occasionally detracts from their sleep; however, many parents may be unaware of this impact as more than three quarters of parents surveyed reported that homework does not impact their child’s sleep. Thus, while sleep is recognized as highly important for academic achievement, homework may be adversely interfering with students’ full academic potential by compromising their sleep.

In regard to homework’s impact on the parent child-relationship, parents in this survey largely indicated that homework does not interfere in their parent–child relationship. However, among the parents who do notice an impact, the majority report that homework can create a power struggle and diminish their overall family time. These results are consistent with Cameron and Bartell’s ( 2009 ) research which found that parents often believe that excessive amounts of homework often cause unnecessary family stress. Likewise, nearly one third of children in this study reported that homework has an impact on their family time.

This study provides the foundation for additional research regarding the impact of academic demands, specifically homework, on children’s social-emotional well-being, including sleep, according to children, parents, and teachers. Additionally, the research provides some information on reasons teachers assign homework and a documentation of the lack of school homework policies, as well as the misguided knowledge among parents and teachers about such policies.

The preexisting literature and meta-analyses indicate homework has little to no positive effect on elementary-aged learners’ academic achievement (Cooper et al. 2006 ; Trautwein and Köller 2003 ; Wolchover 2012 ). This led to the question, if homework is not conducive to academic achievement at this level, how might it impact other areas of children’s lives? This study provides preliminary information regarding the possible impact of homework on the social-emotional health of elementary children. The preliminary conclusions from this perception research may guide districts, educators, and parents to advocate for evidence-based homework policies that support childrens’ academic and social-emotional health. If homework is to be assigned at the elementary level, Table 8 contains recommended best practices for such assignment, along with a sample of specific guidelines for districts, educators, and parents (Holland et al. 2015 ).

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Due to the preliminary nature of this research, some limitations must be addressed. First, research was conducted using newly developed parent, teacher, and student questionnaires, which were not pilot tested or formally validated. Upon analyzing the data, the researchers discovered limitations within the surveys. For example, due to the nature of the survey items, the variables produced were not always consistently scaled. This created challenges when making direct comparisons. Additionally, this limited the sophistication of the statistical procedures that could be used, and reliability could not be calculated in typical psychometric fashion (e.g., Cronbach’s Alpha). Secondly, the small sample size may limit the generalizability of the results, especially in regard to the limited number of teachers (n = 28) we were able to survey. Although numerous districts and schools were contacted within the region, only three districts granted permission. These schools may systematically differ from other schools in the region and therefore do not necessarily represent the general population. Third, this research is based on perception, and determining the actual impacts of homework on child wellness would necessitate a larger scale, better controlled study, examining variables beyond simple perception and eliminating potentially confounding factors. It is possible that individuals within and across rater groups interpreted survey items in different ways, leading to inconsistencies in the underlying constructs apparently being measured. Some phrases such as “social-emotional health” can be understood to mean different things by different raters, which could have affected the way raters responded and thus the results of this study. Relatedly, causal links between homework and student social-emotional well-being cannot be established through the present research design and future research should employ the use of matched control groups who do not receive homework to better delineate the direct impact of homework on well-being. Finally, interpretations of the results are limited by the nested nature of the data (parent and student by teacher). The teachers, parents, and students are not truly independent groups, as student and parent perceptions on the impact of homework likely differ as a function of the classroom (teacher) that they are in, as well as the characteristics of the school they attend, their family environment, and more. The previously mentioned challenge of making direct comparisons across raters due to the design of the surveys, as well as small sample size of teachers, limited the researchers’ ability to address this issue. Future research may address this limitation by collecting data and formulating related lines of inquiry that are more conducive to the analysis of nested data. At this time, this survey research is preliminary. An increased sample size and replication of results is necessary before further conclusions can be made. Researchers should also consider obtaining data from a geographically diverse population that mirrors the population in the United States, and using revised surveys that have undergone a rigorous validation process.

Abeles, V., & Rubenstein, G. (2015). Beyond measure: Rescuing an overscheduled, overtested, underestimated generation . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Google Scholar

American Psychological Association (APA). (2009). Stress in America 2009 . https://bit.ly/39FiTk3 .

American Psychological Association (APA). (2014). Stress in America: Are teens adopting adults’ stress habits? https://bit.ly/2SIiurC .

Baines, L. A., & Slutsky, R. (2009). Developing the sixth sense: Play. Educational HORIZONS , 87 (2), 97–101. https://bit.ly/39LLGU4 .

Bembenutty, H. (2011). The last word: An interview with harris cooper—Research, policies, tips, and current perspectives on homework. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22 (2), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X1102200207 .

Article Google Scholar

Bennett, S., & Kalish, N. (2006). The case against homework: How homework is hurting our children and what we can do about it . New York: Crown Publishers.

Bitsko, R. H., Holbrook, J. R., Ghandour, R. M., Blumberg, S. J., Visser, S. N., Perou, R., & Walkup, J. T. (2018). Epidemiology and impact of health care provider:Diagnosed anxiety and depression among US children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 39 (5), 395. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000571 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cameron, L., & Bartell, L. (2009). The researchers ate the homework! Toronto: Canadian Education Association.

Carrion, V. G., & Wong, S. S. (2012). Can traumatic stress alter the brain? Understanding the implications of early trauma on brain development and learning. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51 (2), S23–S28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.010 .

Cech, S. J. (2008). Poll of US teens finds heavier homework load, more stress over grades. Education Week, 27 (45), 9.

Child Mind Institute. Children’s mental health report . (2015). https://bit.ly/2SSzE4v .

Child Mind Institute. (2016). 2016 children’s mental health report . https://bit.ly/2SQ9kbj .