Importance of ICT in Education Essay

Ict: introduction, teachers and their role in education, impact of ict in education, use of ict in education, importance of ict to students, works cited.

Information and Communication Technology is among the most indispensable tools that the business world relies on today. Virtually all businesses, in one way or another, rely on technology tools to carry out operations. Other organizations like learning institutions are not left behind technology-wise. ICT is increasingly being employed in contemporary learning institutions to ease the work of students and teachers.

Among the most commendable successes of employing ICT in learning institutions is e-learning, in which the ICT tools are used to access classrooms remotely. This paper explores the importance of the tools of the tools of ICT in education and the roles that these tools have played in making learning better and easier.

Teachers are scholars who have mastered specific subjects that form part of their specialty and help in imparting knowledge to students. Some of the roles that teachers play in academic institutions include designing syllabuses, preparing timetables, preparing for lessons and convening students for lessons, and carrying out continuous assessments on students.

Others include keeping records of academic reports, disciplinary records, and other records related to the activities of students in school, like the participation of students in games and other activities.

In cases where there are limitations such that it is impossible to convene people and resources together for learning. E-learning provides a very important and convenient way of teaching people. In such a case, a teacher provides learning materials and lessons online, which can be accessed by his/her students at their convenience.

The materials can be audio files of recorded classroom lessons, audio-visual files for lessons requiring visual information like practical or even text documents, and hypertext documents (Tinio 1). This method of teaching is also convenient for teachers because they are able to record lessons at their convenience, and the assessment of students involves less documentation.

This is because with the use of the internet, teachers are able to upload assignments and continuous assessments on the e-learning systems, and after students are done with the assignments, they use the system or emails to send their completed assignments to their teachers. This comes with a number of advantages which are brought about by having students complete assignments in soft copies.

One of these advantages is that feedback from teachers will be timely and it will be convenient for the teachers. Teachers can also use technology tools such as plagiarism software to check if students have copied the works of other scholars and thus establish the authenticity of the assignment. It can thus be argued that although e-learning systems have their disadvantages, they are very instrumental in teaching people whose schedules are tight and who may have limitations as far as accessing the classroom is concerned.

Therefore technology has been an influential and essential tool in the career of education, and several innovations have been made that have made teaching a much easier career. The paragraph below discusses other ways in which technology has been employed in the education career.

Teachers can also use the tools of ICT in other functions. One such function is keeping records of student performances and other kinds of records within the academic institution. This can be done by uploading the information to a Management Information System for the school or college, which should have a database for supporting the same. The information can also be stored in soft form in Compact Disks, Hard Drives, Flash Disks, or even Digital Video Disks (Obringer 1).

This ensures that information is properly stored and backed up and also ensures that records are not as bulky as they would have been in the absence of the tools of ICT. Such a system also ensures that information can easily be accessed and also ensures that proper privacy of the data is maintained.

Another way in which teachers can use the tools of ICT to ease their work is by employing tools like projectors for presentations of lessons, iPads for students, computers connected to the internet for communicating to students about continuous assessments, and the like (Higgins 1). This way, the teacher will be able to reduce the paperwork that he /she uses in his/her work, and this is bound to make his/her work easier.

For instance, if the teacher can access a projector, he/she can prepare a presentation of a lesson for his/her students, and this way, he will not have to carry textbooks, notebooks, and the like to the classroom for the lesson. The teacher can also post notes and relevant texts for a given course on the information system for the school or on an interactive website, and thus he/she will have more time for discussions during lessons.

Teachers can also, in consultation with IT specialists, develop real-time systems where students can answer questions related woo what they have learned in class and get automated results through the system (Masie 1).

This will help the students understand the concepts taught in class better, and this way, teachers will have less workload. Such websites will also help teachers to show the students how questions related to their specialty are framed early enough so that students can concentrate on knowledge acquisition during class hours.

This is as opposed to a case where the students remain clueless about the kind of questions they expect in exams and spend most of their time preparing for exams rather than reading extensively to acquire knowledge. ICT can also be sued by teachers to advertise the kind of services they offer in schools and also advertise the books and journals they have written. This can be achieved by using websites for the school or specific teachers or professors.

As evidenced in the discussion above, ICT is a very instrumental tool in education as a career. The specific tools of ICT used in education, as discussed above, include the use of ICT in distance learning, storage of student performance and other relevant information in databases and storage media, and the use of tools of ICT in classroom like projectors, iPads and the like. Since the invention of the internet and the subsequent popularity of computers, a lot of functions of education as a career have been made simpler.

These include the administration of continuous assessments, marking continuous assessments, giving feedback to students, and even checking the originality of the ideas expressed in the assignments and examinations. All in all, the impact that ICT has had in educational institutions is so much that school life without ICT is somehow impossible for people who are accustomed to using ICT.

Higgins, Steve. “Does ICT improve learning and teaching in schools”. 2007. Web.

Masie, Shank. “What is electronic learning?” 2007. Web.

Obringer, Ann. “ How E-Learning Works ”. 2008. Web.

Tinio, Victoria. “ICT in Education”. 2008. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, February 20). Importance of ICT in Education. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ict-in-education/

"Importance of ICT in Education." IvyPanda , 20 Feb. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/ict-in-education/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Importance of ICT in Education'. 20 February.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Importance of ICT in Education." February 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ict-in-education/.

1. IvyPanda . "Importance of ICT in Education." February 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ict-in-education/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Importance of ICT in Education." February 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ict-in-education/.

- Traditional Learning and E-Learning Differences

- E-Learning: Video, Television and Videoconferencing

- Nontakers Perceptiom Towards ICT

- Technological Advances in Education

- Computer Based Training Verses Instructor Lead Training

- Smart Classroom and Its Effect on Student Learning

- Use of Technology as a Learning Tool

- Computers & Preschool Children: Why They Are Required in Early Childhood Centers

This site belongs to UNESCO's International Institute for Educational Planning

IIEP Learning Portal

Search form

- issue briefs

- Improve learning

Information and communication technology (ICT) in education

Information and communications technology (ict) can impact student learning when teachers are digitally literate and understand how to integrate it into curriculum..

Schools use a diverse set of ICT tools to communicate, create, disseminate, store, and manage information.(6) In some contexts, ICT has also become integral to the teaching-learning interaction, through such approaches as replacing chalkboards with interactive digital whiteboards, using students’ own smartphones or other devices for learning during class time, and the “flipped classroom” model where students watch lectures at home on the computer and use classroom time for more interactive exercises.

When teachers are digitally literate and trained to use ICT, these approaches can lead to higher order thinking skills, provide creative and individualized options for students to express their understandings, and leave students better prepared to deal with ongoing technological change in society and the workplace.(18)

ICT issues planners must consider include: considering the total cost-benefit equation, supplying and maintaining the requisite infrastructure, and ensuring investments are matched with teacher support and other policies aimed at effective ICT use.(16)

Issues and Discussion

Digital culture and digital literacy: Computer technologies and other aspects of digital culture have changed the ways people live, work, play, and learn, impacting the construction and distribution of knowledge and power around the world.(14) Graduates who are less familiar with digital culture are increasingly at a disadvantage in the national and global economy. Digital literacy—the skills of searching for, discerning, and producing information, as well as the critical use of new media for full participation in society—has thus become an important consideration for curriculum frameworks.(8)

In many countries, digital literacy is being built through the incorporation of information and communication technology (ICT) into schools. Some common educational applications of ICT include:

- One laptop per child: Less expensive laptops have been designed for use in school on a 1:1 basis with features like lower power consumption, a low cost operating system, and special re-programming and mesh network functions.(42) Despite efforts to reduce costs, however, providing one laptop per child may be too costly for some developing countries.(41)

- Tablets: Tablets are small personal computers with a touch screen, allowing input without a keyboard or mouse. Inexpensive learning software (“apps”) can be downloaded onto tablets, making them a versatile tool for learning.(7)(25) The most effective apps develop higher order thinking skills and provide creative and individualized options for students to express their understandings.(18)

- Interactive White Boards or Smart Boards : Interactive white boards allow projected computer images to be displayed, manipulated, dragged, clicked, or copied.(3) Simultaneously, handwritten notes can be taken on the board and saved for later use. Interactive white boards are associated with whole-class instruction rather than student-centred activities.(38) Student engagement is generally higher when ICT is available for student use throughout the classroom.(4)

- E-readers : E-readers are electronic devices that can hold hundreds of books in digital form, and they are increasingly utilized in the delivery of reading material.(19) Students—both skilled readers and reluctant readers—have had positive responses to the use of e-readers for independent reading.(22) Features of e-readers that can contribute to positive use include their portability and long battery life, response to text, and the ability to define unknown words.(22) Additionally, many classic book titles are available for free in e-book form.

- Flipped Classrooms: The flipped classroom model, involving lecture and practice at home via computer-guided instruction and interactive learning activities in class, can allow for an expanded curriculum. There is little investigation on the student learning outcomes of flipped classrooms.(5) Student perceptions about flipped classrooms are mixed, but generally positive, as they prefer the cooperative learning activities in class over lecture.(5)(35)

ICT and Teacher Professional Development: Teachers need specific professional development opportunities in order to increase their ability to use ICT for formative learning assessments, individualized instruction, accessing online resources, and for fostering student interaction and collaboration.(15) Such training in ICT should positively impact teachers’ general attitudes towards ICT in the classroom, but it should also provide specific guidance on ICT teaching and learning within each discipline. Without this support, teachers tend to use ICT for skill-based applications, limiting student academic thinking.(32) To support teachers as they change their teaching, it is also essential for education managers, supervisors, teacher educators, and decision makers to be trained in ICT use.(11)

Ensuring benefits of ICT investments: To ensure the investments made in ICT benefit students, additional conditions must be met. School policies need to provide schools with the minimum acceptable infrastructure for ICT, including stable and affordable internet connectivity and security measures such as filters and site blockers. Teacher policies need to target basic ICT literacy skills, ICT use in pedagogical settings, and discipline-specific uses. (21) Successful implementation of ICT requires integration of ICT in the curriculum. Finally, digital content needs to be developed in local languages and reflect local culture. (40) Ongoing technical, human, and organizational supports on all of these issues are needed to ensure access and effective use of ICT. (21)

Resource Constrained Contexts: The total cost of ICT ownership is considerable: training of teachers and administrators, connectivity, technical support, and software, amongst others. (42) When bringing ICT into classrooms, policies should use an incremental pathway, establishing infrastructure and bringing in sustainable and easily upgradable ICT. (16) Schools in some countries have begun allowing students to bring their own mobile technology (such as laptop, tablet, or smartphone) into class rather than providing such tools to all students—an approach called Bring Your Own Device. (1)(27)(34) However, not all families can afford devices or service plans for their children. (30) Schools must ensure all students have equitable access to ICT devices for learning.

Inclusiveness Considerations

Digital Divide: The digital divide refers to disparities of digital media and internet access both within and across countries, as well as the gap between people with and without the digital literacy and skills to utilize media and internet.(23)(26)(31) The digital divide both creates and reinforces socio-economic inequalities of the world’s poorest people. Policies need to intentionally bridge this divide to bring media, internet, and digital literacy to all students, not just those who are easiest to reach.

Minority language groups: Students whose mother tongue is different from the official language of instruction are less likely to have computers and internet connections at home than students from the majority. There is also less material available to them online in their own language, putting them at a disadvantage in comparison to their majority peers who gather information, prepare talks and papers, and communicate more using ICT. (39) Yet ICT tools can also help improve the skills of minority language students—especially in learning the official language of instruction—through features such as automatic speech recognition, the availability of authentic audio-visual materials, and chat functions. (2)(17)

Students with different styles of learning: ICT can provide diverse options for taking in and processing information, making sense of ideas, and expressing learning. Over 87% of students learn best through visual and tactile modalities, and ICT can help these students ‘experience’ the information instead of just reading and hearing it. (20)(37) Mobile devices can also offer programmes (“apps”) that provide extra support to students with special needs, with features such as simplified screens and instructions, consistent placement of menus and control features, graphics combined with text, audio feedback, ability to set pace and level of difficulty, appropriate and unambiguous feedback, and easy error correction. (24)(29)

Plans and policies

- India [ PDF ]

- Detroit, USA [ PDF ]

- Finland [ PDF ]

- Alberta Education. 2012. Bring your own device: A guide for schools . Retrieved from http://education.alberta.ca/admin/technology/research.aspx

- Alsied, S.M. and Pathan, M.M. 2015. ‘The use of computer technology in EFL classroom: Advantages and implications.’ International Journal of English Language and Translation Studies . 1 (1).

- BBC. N.D. ‘What is an interactive whiteboard?’ Retrieved from http://www.bbcactive.com/BBCActiveIdeasandResources/Whatisaninteractivewhiteboard.aspx

- Beilefeldt, T. 2012. ‘Guidance for technology decisions from classroom observation.’ Journal of Research on Technology in Education . 44 (3).

- Bishop, J.L. and Verleger, M.A. 2013. ‘The flipped classroom: A survey of the research.’ Presented at the 120th ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition. Atlanta, Georgia.

- Blurton, C. 2000. New Directions of ICT-Use in Education . United National Education Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO).

- Bryant, B.R., Ok, M., Kang, E.Y., Kim, M.K., Lang, R., Bryant, D.P. and Pfannestiel, K. 2015. ‘Performance of fourth-grade students with learning disabilities on multiplication facts comparing teacher-mediated and technology-mediated interventions: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Behavioral Education. 24.

- Buckingham, D. 2005. Educación en medios. Alfabetización, aprendizaje y cultura contemporánea, Barcelona, Paidós.

- Buckingham, D., Sefton-Green, J., and Scanlon, M. 2001. 'Selling the Digital Dream: Marketing Education Technologies to Teachers and Parents.' ICT, Pedagogy, and the Curriculum: Subject to Change . London: Routledge.

- "Burk, R. 2001. 'E-book devices and the marketplace: In search of customers.' Library Hi Tech 19 (4)."

- Chapman, D., and Mählck, L. (Eds). 2004. Adapting technology for school improvement: a global perspective. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Cheung, A.C.K and Slavin, R.E. 2012. ‘How features of educational technology applications affect student reading outcomes: A meta-analysis.’ Educational Research Review . 7.

- Cheung, A.C.K and Slavin, R.E. 2013. ‘The effectiveness of educational technology applications for enhancing mathematics achievement in K-12 classrooms: A meta-analysis.’ Educational Research Review . 9.

- Deuze, M. 2006. 'Participation Remediation Bricolage - Considering Principal Components of a Digital Culture.' The Information Society . 22 .

- Dunleavy, M., Dextert, S. and Heinecke, W.F. 2007. ‘What added value does a 1:1 student to laptop ratio bring to technology-supported teaching and learning?’ Journal of Computer Assisted Learning . 23.

- Enyedy, N. 2014. Personalized Instruction: New Interest, Old Rhetoric, Limited Results, and the Need for a New Direction for Computer-Mediated Learning . Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center.

- Golonka, E.M., Bowles, A.R., Frank, V.M., Richardson, D.L. and Freynik, S. 2014. ‘Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness.’ Computer Assisted Language Learning . 27 (1).

- Goodwin, K. 2012. Use of Tablet Technology in the Classroom . Strathfield, New South Wales: NSW Curriculum and Learning Innovation Centre.

- Jung, J., Chan-Olmsted, S., Park, B., and Kim, Y. 2011. 'Factors affecting e-book reader awareness, interest, and intention to use.' New Media & Society . 14 (2)

- Kenney, L. 2011. ‘Elementary education, there’s an app for that. Communication technology in the elementary school classroom.’ The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications . 2 (1).

- Kopcha, T.J. 2012. ‘Teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology under situated professional development.’ Computers and Education . 59.

- Miranda, T., Williams-Rossi, D., Johnson, K., and McKenzie, N. 2011. "Reluctant readers in middle school: Successful engagement with text using the e-reader.' International journal of applied science and technology . 1 (6).

- Moyo, L. 2009. 'The digital divide: scarcity, inequality and conflict.' Digital Cultures . New York: Open University Press.

- Newton, D.A. and Dell, A.G. 2011. ‘Mobile devices and students with disabilities: What do best practices tell us?’ Journal of Special Education Technology . 26 (3).

- Nirvi, S. (2011). ‘Special education pupils find learning tool in iPad applications.’ Education Week . 30 .

- Norris, P. 2001. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide . Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- Project Tomorrow. 2012. Learning in the 21st century: Mobile devices + social media = personalized learning . Washington, D.C.: Blackboard K-12.

- Riasati, M.J., Allahyar, N. and Tan, K.E. 2012. ‘Technology in language education: Benefits and barriers.’ Journal of Education and Practice . 3 (5).

- Rodriquez, C.D., Strnadova, I. and Cumming, T. 2013. ‘Using iPads with students with disabilities: Lessons learned from students, teachers, and parents.’ Intervention in School and Clinic . 49 (4).

- Sangani, K. 2013. 'BYOD to the classroom.' Engineering & Technology . 3 (8).

- Servon, L. 2002. Redefining the Digital Divide: Technology, Community and Public Policy . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Smeets, E. 2005. ‘Does ICT contribute to powerful learning environments in primary education?’ Computers and Education. 44 .

- Smith, G.E. and Thorne, S. 2007. Differentiating Instruction with Technology in K-5 Classrooms . Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

- Song, Y. 2014. '"Bring your own device (BYOD)" for seamless science inquiry in a primary school.' Computers & Education. 74 .

- Strayer, J.F. 2012. ‘How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation.’ Learning Environment Research. 15.

- Tamim, R.M., Bernard, R.M., Borokhovski, E., Abrami, P.C. and Schmid, R.F. 2011. ‘What forty years of research says about the impact of technology on learning: A second-order meta-analysis and validation study. Review of Educational Research. 81 (1).

- Tileston, D.W. 2003. What Every Teacher Should Know about Media and Technology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Turel, Y.K. and Johnson, T.E. 2012. ‘Teachers’ belief and use of interactive whiteboards for teaching and learning.’ Educational Technology and Society . 15(1).

- Volman, M., van Eck, E., Heemskerk, I. and Kuiper, E. 2005. ‘New technologies, new differences. Gender and ethnic differences in pupils’ use of ICT in primary and secondary education.’ Computers and Education. 45 .

- Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Cox, M., Knezek, D. and ten Brummelhuis, A. 2013. ‘Under which conditions does ICT have a positive effect on teaching and learning? A call to action.’ Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 29 (1).

- Warschauer, M. and Ames, M. 2010. ‘Can one laptop per child save the world’s poor?’ Journal of International Affairs. 64 (1).

- Zuker, A.A. and Light, D. 2009. ‘Laptop programs for students.’ Science. 323 (5910).

Related information

- Information and communication technologies (ICT)

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Kate Billingsley

introduction

Technology is the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry. Technology is a tool that can be used to solve real-world problems. The field of Science, Technology, and Society (STS) “seeks to promote cross-disciplinary integration, civic engagement, and critical thinking” of concepts in the worlds of science and technology ( Harvard University, n.d.). As an aspect of everyday life, technology is continuously evolving to ensure that humanity can be productive, efficient, and follow the path of globalization . STS is a concept that encompasses countless fields of study. “Scientists, engineers, and medical professionals swim (as they must) in the details of their technical work: experiments, inventions, treatments and cures. “promotes cross-disciplinary integration, civic engagement, and critical thinking” It’s an intense and necessary focus” ( Stanford University , n.d.). On the opposite side of the spectrum is STS, which “draws attention to the water: the social, political, legal, economic, and cultural environment that shapes research and invention, supports or inhibits it — and is in turn shaped by evolving science and technology” ( Stanford University , n.d.). Technology is a crucial part of life that is constantly developing to fit the changing needs of society and aiding humanity in simplifying the demands of everyday life.

According to Oberdan (2010), science and technology share identical goals. “At first glance, they seem to provide a deep and thorough going division between the two but, as the discussion progresses, it will become clear that there are, indeed, areas of overlap, too” (Oberdan, 25). Philosophers believe that for a claim to be considered knowledge, it must first be justified, like a hypothesis, and true. Italian astronomer, physicist, and engineer, Galileo Galilei , was incredibly familiar with the obstacles involved with proving something to be a fact or a theory within the scientific world. Galileo was condemned by the Roman Catholic church for his beliefs that contradicted existing church doctrine (Coyne, 2013). Galileo’s discoveries, although denounced by the church were incredibly innovative and progressive for their time, and are still seen as the basis for modern astronomy today. Nearly 300 years later, Galileo was eventually forgiven by the church, and to this day he is seen as one of the most well known and influential astronomers of all time. Many new innovations and ideas often receive push back before becoming revolutionary and universal practices.

INNOVATION IN TECHNOLOGY

Flash forward to modern time where we can see that innovation is happening even more around us. Look no further than what could be considered the culmination of modern technological innovation: the mobile phone. Cell phone technology has developed exponentially since the invention of the first mobile phone in 1973 ( Seward , 2013). Although there was a period for roughly 20 years in which cell phones were seen as unnecessary and somewhat impractical, as society’s needs changed and developed in the late 1990s, there was a large spike in consumer purchases of mobile phones. Now, cell phones are an entity that can be seen virtually anywhere, which is in large part due to their practicality. Cell phones, specifically smartphones such as Apple’s iPhone , have changed the way society uses technology. Smartphone technology has eliminated the need for people to have a separate cell phone, MP3 player, GPS, mobile video gaming systems, and more. Consumers may fail to realize how many aspects of modern technological advancement are involved in the use of their mobile phones. Cell phones use wifi to browse the internet, use google, access social media, and more. Although these technologies are beneficial, they also allow consumers locations to be traced and phone conversations to be recorded. Modern cell phone technologies collect data on consumers, and many people are unsure how this information is being used. Additionally, mobile phones come equipped with virus protection which brings the field of cybersecurity into smartphone usage. The technological advances that have been made in the market for mobile phones have been targeted towards the changing needs of consumers and society. As proven by the rise in cell phones, with advancements in the field of STS comes new unforeseen obstacles and ethical dilemmas.

Technology is changing the way we live in this world. Innovations in the scientific world are becoming increasingly more advanced to help conserve earth’s resources and aid in the reduction of pollutants . Transportation is a field that has changed greatly in recent years due to modernization in science and technology, as well as an increased awareness of environmental concerns. The transportation industry continues to be a large producer of pollution

due to emissions from cars, trains, and other modes of transportation. As a result, cars have changed a great deal in recent years. A frontrunner in creating environmentally friendly luxury cars is Tesla, lead by CEO Elon Musk. Although nearly every brand of car has an electric option that either runs completely gas free, or uses significantly less fuel than standard cars, Tesla has taken this one step further and created a zero emissions vehicle. However, some believe that Tesla has taken their innovations in the transportation market a bit too far, specifically with their release of driverless cars.

“The recent reset of expectations on driverless cars is a leading indicator for other types of AI-enabled systems as well,” says David A. Mindell, professor of aeronautics and astronautics, and the Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing at MIT. “These technologies hold great promise, but it takes time to understand the optimal combination of people and machines. And the timing of adoption is crucial for understanding the impact on workers” ( Dizikes , 2019).

As the earth becomes more and more polluted, consumers are seeking to find new ways to cut down on their negative impacts on the earth. Eco-friendly cars are a simple yet effective way in which consumers can cut back on their pollution within their everyday lives.

THE INTERSECTION OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

The way in which energy is generated has changed greatly to benefit consumers and the environment. Energy production has followed a rather linear path over time, and is a prime example of how new innovations stem from old technologies. In the early 1800s, the steam engine acted as the main form of creating energy. It wasn’t until the mid-late 1800s that the combustion engine was invented. This invention was beneficial because it was more efficient than its predecessor, and became a form of energy that was streamlined to be used in countless applications. As time has progressed, this linear path of innovation has continued. As new energy creating technologies have emerged, machinery that was once seen as efficient and effective have been phased out. Today, largely due to the increased demand for clean energy sources, the linear path has split and consumers are faced with numerous options for clean, environmentally friendly energy sources. Over time, scientists and engineers have come to realize that these forms of energy pollute and damage the earth. Solar power, a modern form of clean energy, was once seen as an expensive and impractical way of turning the sun’s energy into usable energy. Now, it is common to see newly built homes with solar panels already built in. Since technology develops to fit the needs of society, scientists have worked to improve solar panels to make them cheaper and easier to access. A total of 173,000 terawatts (trillions of watts) of solar energy strikes the Earth continuously, which is more than 10,000 times of the world’s total energy use ( Chandler , 2011). This information may seem staggering, but is crucial in understanding the importance, as well as the large influence that modern forms of energy can have on society.

Technology has become a crucial part of our society. Without technological advancements, so much of our everyday lives would be drastically different. As technology develops, it strives to fulfill the changing needs of society. Technology progresses as society evolves. That being said, progress comes at a price. This price is different for each person, and varies based on how much people value technological and scientific advancements in their own lives. Thomas Parke Hughes’s Networks of Power “compared how electric power systems developed in America, England, and Germany, showing that they required not only electrical but social ‘engineering’ to create the necessary legal frameworks, financing, standards, political support, and organizational designs” ( Stanford University ). In other words, the scientific invention and production of a new technology does not ensure its success. Technology’s success is highly dependent on society’s acceptance or rejection of a product, as well as whether or not any path dependence is involved. Changing technologies benefit consumers in countless aspects of their lives including in the workforce, in communications, in the use of natural resources, and so much more. These innovations across numerous different markets aid society by making it easier to complete certain tasks. Innovation will never end; rather, it will continue to develop at increasing rates as science and technological fields becomes more and more cutting edge.

Chapter Questions

- True or False: Improvements in science and technology always benefit society

- Multiple Choice : Technology is: A. The application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry B. Tools and machines that may be used to solve real-world problems C. Something that does not change D. Both A and B

- Short Answer: Discuss ways in which technological progression over time is related and how this relationship has led to the creation of new innovation.

Chandler, D. (2011). Shining brightly: Vast amounts of solar energy radiate to the Earth constantly, but tapping that energy cost-effectively remains a challenge. MIT News. http://news.mit.edu/2011/energy-scale-part3-1026

Coyne, SJ, G. V. (2013). Science meets biblical exegesis in the Galileo affair. Zygon® , 48 (1), 221-229. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2012.01324.x

Dizikes, P., & MIT News Office. (2019). MIT report examines how to make technology work for society. http://news.mit.edu/2019/work-future-report-technology-jobs-society-0904

Florez, D., García-Duque, C. E., & Osorio, J. C. (2019). Is technology (still) applied science? Technology in Society. Technology in Society, 59. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101193

Groce, J. E., Farrelly, M. A., Jorgensen, B. S., & Cook, C. N. (2019). Using social‐network research to improve outcomes in natural resource management. Conservation biology , 33 (1), 53-65. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/cobi.13127

Harvard University. (n.d.) What is STS? . http://sts.hks.harvard.edu/about/whatissts.html .

Union of Concerned Scientists. (2018). How Do Battery Electric Cars Work? https://www.ucsusa.org/clean-vehicles/electric-vehicles/how-do-battery-electric-cars-work .

Oberdan, T. (2010). Science, Technology, and the Texture of Our Lives. Tavenner Publishing Company.

Seward, Z. M. (2013). The First Mobile Phone Call Was Made 40 Years Ago Today . The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/04/the-first- mobile-phone-call-was-made-40-years-ago-today/274611/ .

Stanford University. (n.d.). What is the Study of STS? . https://sts.stanford.edu/about/what-study-sts .

Wei, R., & Lo, V.-H. (2006). Staying connected while on the move: Cell phone use and social connectedness. New Media & Society, 8 (1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444806059870

Winston, B. (2006). Media Technology and Society: A History From the Telegraph to the Internet . London: Routledge.

Images & Videos

“Tesla Model 3 Monaco” is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Building bridges between science and society for a better future. | Nadine Bongaerts | TEDxSaclay

“Tesla Model 3 Monaco” is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

To the extent possible under law, Kate Billingsley has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to Science, Technology, & Society: A Student-Led Exploration , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academic & Employability Skills

Subscribe to academic & employability skills.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 412 other subscribers.

Email Address

How to write a conclusion

Posted in: academic writing , essay-writing

Your conclusion is very important as it presents the final words of your assignment. It should leave the reader satisfied that you have provided a thorough, well-researched and reasoned response to the assignment question.

Your conclusion should move from the specific to the general (Introductions move from general to specific). You can begin your conclusion by reformulating the thesis statement you wrote in your introduction. This will remind the reader of the purpose of your essay.

Your conclusion should also include some or all of the following elements:

Here is a simple conclusion to illustrate how it works:

Hopkins, D. and Reid, T., 2018. The Academic Skills Handbook: Your Guid e to Success in Writing, Thinking and Communicating at University . Sage.

Share this:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click here to cancel reply.

- Email * (we won't publish this)

Write a response

Bias-proof your GenAI: Strategies to mitigate algorithmic and human biases

As the world of Higher Education increasingly embraces the power of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI), the University is taking proactive steps to equip you with the knowledge and skills to navigate this rapidly evolving landscape. On 10 April, we started...

How skills enrichment workshops have helped me improve my work

Third year BSc Biomedical Sciences student Sophie Benton tells us how skills enrichment workshops have increased her confidence with academic writing.

Meet the skills enrichment team

As the Skills Centre’s programme of academic and employability skills workshops gets underway, we introduce our friendly team of teachers, dedicated to sharing their expertise to help enrich your academic journey at Bath, and share some of their academic skills...

NCI LIBRARY

Academic writing skills guide: conclusions.

- Key Features of Academic Writing

- The Writing Process

- Understanding Assignments

- Brainstorming Techniques

- Planning Your Assignments

- Thesis Statements

- Writing Drafts

- Structuring Your Assignment

- How to Deal With Writer's Block

- Using Paragraphs

- Conclusions

- Introductions

- Revising & Editing

- Proofreading

- Grammar & Punctuation

- Reporting Verbs

- Signposting, Transitions & Linking Words/Phrases

- Using Lecturers' Feedback

Communications from the Library: Please note all communications from the library, concerning renewal of books, overdue books and reservations will be sent to your NCI student email account.

- << Previous: Using Paragraphs

- Next: Introductions >>

- Last Updated: Apr 23, 2024 1:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ncirl.ie/academic_writing_skills

Conclusions and Discussion

- Open Access

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Julian Fraillon 2 ,

- John Ainley 2 ,

- Wolfram Schulz 2 ,

- Tim Friedman 2 &

- Eveline Gebhardt 2

25k Accesses

The International Computer and Information Literacy Study 2013 (ICILS 2013) investigated the ways in which young people have developed the computer and information literacy (CIL) that enables them to participate fully in the digital age. This study, the first in international research to investigate students’ acquisition of CIL, has been groundbreaking in two ways. The first is its establishment of a crossnationally agreed definition and explication of CIL in terms of its component knowledge, skills, and understandings. The second is its operationalization of CIL as a crossnationally comparable measurement tool and marker of digital literacy.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

- Reference Class

- Information Literacy

- Digital Literacy

- Parental Educational Attainment

- Parental Occupational Status

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

The CIL construct was developed with reference to decades of research into the knowledge, skills, and understanding involved in effective use of information and communication technology (ICT). Various terms with similar but not identical meanings such as information literacy, computer literacy, digital literacy , and ICT literacy have been used to characterize this set of competences.

The CIL construct is described and explained in detail in the ICILS Assessment Framework (Fraillon, Schulz, & Ainley, 2013 ). The framework, developed in consultation with ICILS national research coordinators (NRCs) and other people expert in digital and ICT literacy, guided all aspects of the ICILS instrument development and data collection stages. One important outcome of this work has been the establishment of a crossnational, empirical foundation for describing the competencies underpinning the CIL construct.

The ICILS assessment of CIL is unique in the field of crossnational assessment because it comprises tasks grouped into self-contained, computer-based “modules” that reflect school-based research and communication. Included in each module is at least one “open” task wherein students create an information product (such as a poster, presentation, or website) using purpose-built software that applies the conventions of software interface design. The ICILS assessment is thus similar to classroom-based assessments that allow students freedom to work with a range of software tools on open-ended tasks.

However, in order to ensure standardization of students’ experience and comparability of the resultant data, the ICILS 2013 assessment required students to work in a contained test environment, designed to prevent differential exposure to digital resources from outside that environment. Such exposure could have confounded the comparability (a necessary feature of instruments used in large-scale assessments) of the student data.

The previous chapters in this international report on ICILS 2013 provided information on CIL achievement across countries, the contexts in which CIL was being taught and learned, and the relationship of CIL as a learning outcome to student characteristics and school contexts.

To provide an overview in this current chapter of these earlier recorded results, we summarize the main study outcomes with respect to each of the four research questions that guided the study. We also discuss country-level outcomes concerned with aspects of ICT use in education as well as the findings from our bivariate and multivariate analyses designed to explore associations between CIL and student and school factors. We then consider a number of implications of the study’s findings for educational policy and practice. We conclude the chapter by suggesting future directions for international research on CIL education.

ICILS guiding questions

The four research questions that guided the study were these:

What variations exist between countries, and within countries, in student computer and information literacy?

What aspects of schools and education systems are related to student achievement in computer and information literacy with respect to:

The general approach to computer and information literacy education;

School and teaching practices regarding the use of technologies in computer and information literacy;

Teacher attitudes to and proficiency in using computers;

Access to ICT in schools; and

Teacher professional development and within-school delivery of computer and information literacy programs.

What characteristics of students’ levels of access to, familiarity with, and self-reported proficiency in using computers are related to student achievement in computer and information literacy?

How do these characteristics differ among and within countries?

To what extent do the strengths of the relations between these characteristics and measured computer and information literacy differ among countries?

What aspects of students’ personal and social backgrounds (such as gender, socioeconomic background, and language background) are related to computer and information literacy?

Student proficiency in using computers

Student CIL proficiency was measured using an instrument comprising four thematic modules, each of which included discrete tasks Footnote 1 and each of which typically took less than a minute to complete. These tasks were followed by a large task that typically took 15 to 20 minutes to complete. The following discussion of student CIL proficiency includes examples taken from the After-School Exercise assessment module. The large task from this module required students to use given digital resources to create a poster advertising an after-school exercise program. Chapter 3 of this report provides a more detailed discussion, along with illustrative examples, of CIL proficiency.

The computer and information literacy (CIL) scale

The ICILS CIL scale, which has an average score set to 500 and a standard deviation of 100, comprises four proficiency levels. Accounts of what students should be able to achieve at each level serve to describe the scale.

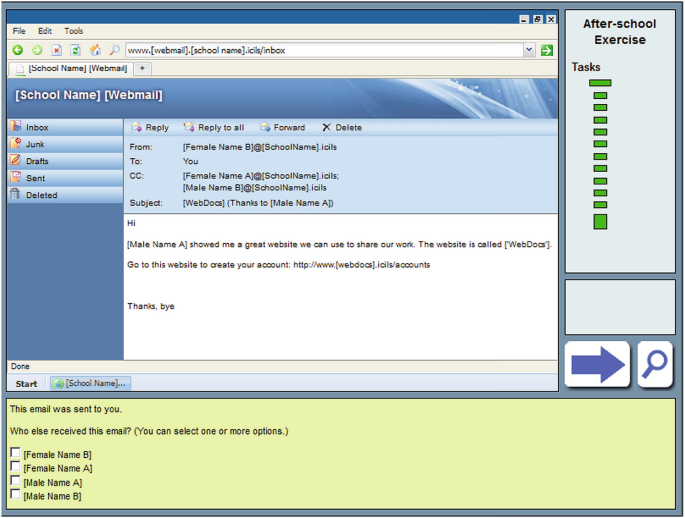

Students working at Level 1 demonstrate familiarity with the basic range of software commands that enable them to access files and complete routine text and layout editing when directed to do so. Students can recognize some basic software conventions as well as the potential for misuse of computers by unauthorized users. Figure 9.1 provides an example of a Level 1 task. This task required students to identify the recipients of an email displaying the “From,” “To,” and “Cc” fields. The task assessed students’ familiarity with the conventions used to display the sender and recipients of emails.

Example Level 1 task

The work involved in doing the large task (creating a poster) contained in the After-School Exercise module provides another example of achievement at Level 1. The Level 1 aspect of the task required students to provide evidence of planning the poster in terms of selecting colors that would denote the roles of the poster’s text, background, and images.

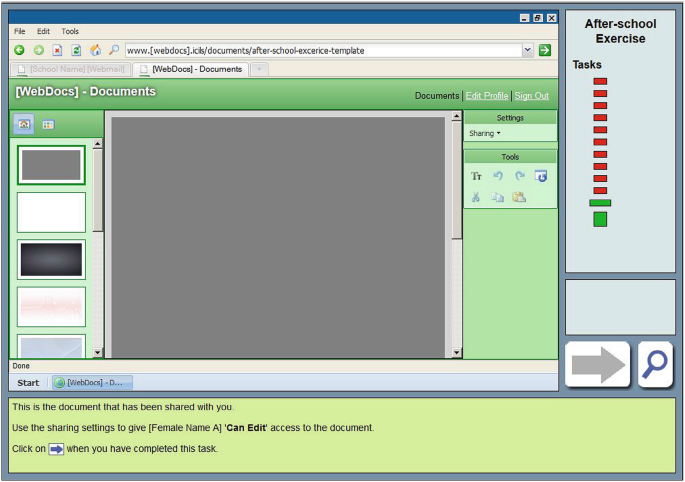

Students working at Level 2 demonstrate basic use of computers as information resources. Students are able to locate explicit information in simple electronic resources, select and add content to information products, and demonstrate some control of layout and formatting of text and images in information products. They demonstrate awareness of the need to protect access to some electronic information and of some possible consequences of unwanted access to information. Figure 9.2 provides an example of a Level 2 task.

Example Level 2 task

The task shown in the figure required students to allocate “can edit” rights in the collaborative workspace to another student with whom, according to the module narrative, students were “collaborating” on the task. To complete this nonlinear skills task, Footnote 2 students needed to navigate within the website to the “settings” menu and then use its options to allocate the required user access. The Level 2 aspect of the module’s large task required students to produce a relevant title for the poster, and then format the title to make its role clear. Ability to use formatting tools to some degree in order to show the role of different text elements is thus an indicator of achievement at Level 2. may be biased

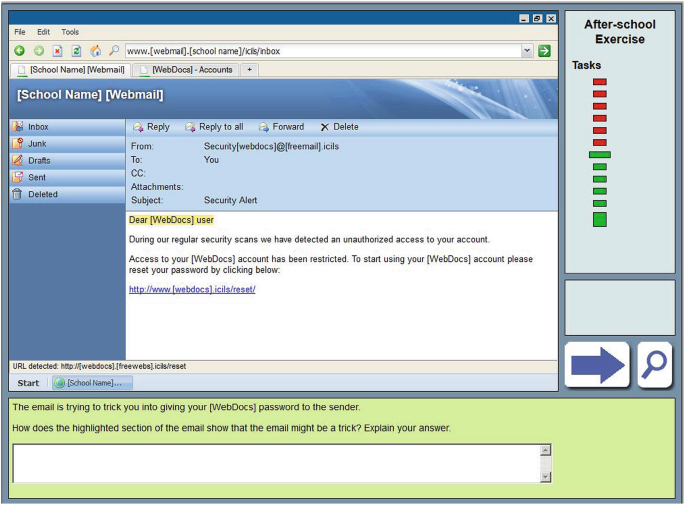

Students working at Level 3 demonstrate sufficient knowledge, skills, and understanding to independently search for and locate information and then edit it to suit the audience for, and the purpose of, the information products they create. Students at this level are able to select relevant information from within electronic resources and develop information products that exhibit controlled layout and design. They also demonstrate awareness that the information they access may be biased, inaccurate, or unreliable. Figure 9.3 provides an example of a Level 3 task.

Example Level 3 task

The task shown in Figure 9.3 required students to explain how the greeting (highlighted in the email) might be evidence that the email is trying to “trick” them. Ability to recognize that a generic (rather than personalized) greeting is one possible piece of evidence is an example of achievement at Level 3. Examples of Level 3 achievements in the large-task poster include students being able to complete some adaptation of information from resources (as opposed to directly copying and pasting information) and ability to include images that are well aligned with the poster’s other elements.

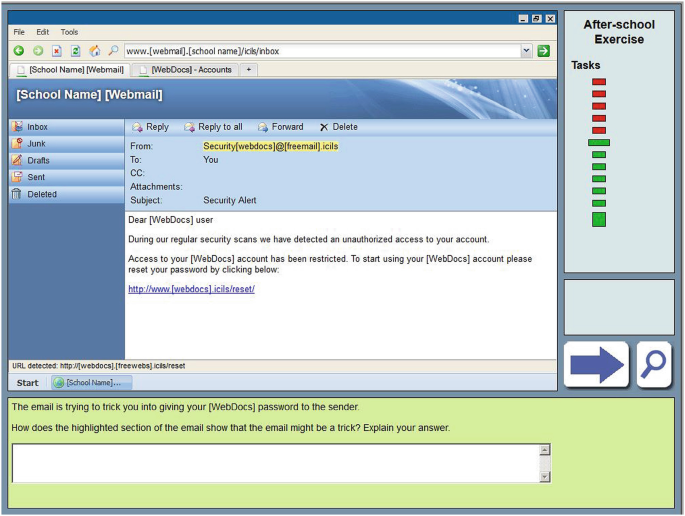

Students working at Level 4 execute control and evaluative judgment when searching for information and creating information products. They also demonstrate awareness of audience and purpose when searching for information, selecting information to include in information products, and formatting and laying out the information products they create. They furthermore demonstrate awareness of the potential for information to be a commercial and malleable commodity and of issues relating to the use of electronically sourced third-party intellectual property. Figure 9.4 provides an example of a Level 4 task.

Example Level 4 task

As with the task shown in Figure 9.3 , the task in Figure 9.4 asked students to explain how the email address of the sender (highlighted in the email) might be evidence of the email trying to “trick” them. Students who recognize that the email is from a “freemail” account (and not a company account) or that the email address does not match the root of the hyperlink are achieving at Level 4 rather than lower levels because they demonstrate a more sophisticated understanding of email protocols with respect to safe and secure use. Examples of Level 4 achievements in the After-School Exercise poster task include students rephrasing the key points from source information and using formatting tools consistently throughout the poster so that the roles of the different text elements are clear to the reader.

Student achievement on the CIL scale

We can interpret and compare students’ CIL by referring to their CIL scale scores and the proficiency levels of the scale.

Student CIL varied considerably across the ICILS countries. The average national scores on the scale ranged from 361 to 553 scale points, a span that extends from below Level 1 to a standard of proficiency within Level 3. This range was equivalent to almost two standard deviations. However, we need to acknowledge that the distribution of country CIL means was skewed because of the means of three countries being significantly below the ICILS 2013 average and the means of 12 other countries being significantly above the ICILS 2013 average.

Eighty-one percent of students achieved scores that placed them within CIL Levels 1, 2, and 3. In all but two countries, Turkey and Thailand, the highest percentage of students was in Level 2.

Students’ computer use and CIL

A long conducted and established research literature shows that students’ social background characteristics Footnote 3 and students’ personal characteristics Footnote 4 are associated with student achievement across a range of learning areas. These same student-level factors were associated with CIL proficiency in ICILS. Characteristics reflecting higher socioeconomic status were associated with higher CIL proficiency both within and across countries.

Female students had higher CIL scale scores in all but two countries (Thailand and Turkey, where the differences were not statistically significant). This finding was not unexpected given that CIL is heavily reliant on text-based reading skills and given past research showing that females tend to outperform males on tests of reading. Similarly, students who spoke the language of the CIL test (which is also the language of instruction in their country) also performed better on the assessment.

When we took the associations between these various student factors into account using multiple regression techniques, we found that the following variables had statistically significant positive associations with CIL in most countries: students’ gender (female compared to male), students’ expected educational attainment, parental educational attainment, parental occupational status, the number of books in the home, and ICT home resources.

ICILS also investigated student access to, familiarity with, and confidence in using computers. Students were asked a range of questions relating to their access to and use of computers at home, at school, and in other places. There is an assumption that the generation of young people that includes the ICILS target grade students (i.e., Grade 8) has grown up with computers as a ubiquitous part of their lives. However, questions remain as to how such access relates to their CIL.

Almost all ICILS students reported that they were experienced users of computers and had access to them at home and at school. On average across the ICILS countries, more than one third of the Grade 8 students said they had been using computers for seven or more years, with a further 29 percent reporting that they had been using computers for between five and seven years. Ninety-four percent of the students on average crossnationally reported having at least one computer (desktop, laptop, notebook, or tablet device) at home, while 48 percent reported having three or more computers at home. Ninety-two percent of students stated that they had some form of internet connection at home. Both number of computers students had at home and access to a home internet connection were positively associated with CIL scores.

The ICILS student questionnaire also asked students a range of questions about their frequency of computer use, the types of tasks they completed using computers, and their attitudes toward using computers. These questions were underpinned by hypotheses that increased computer use, and focused use, would be positively associated with CIL.

Students across the ICILS countries reported using computers more frequently at home than elsewhere. On average, 87 percent said they used a computer at home at least once a week, whereas 54 percent and 13 percent reported this same frequency of computer use at school and other places respectively.

Computer use outside school

ICILS 2013 data indicate that students were making widespread and frequent use of digital technologies when outside school. Students tended to use the internet for social communication and exchange of information, computers for recreation, and software applications for school work and other purposes.

On average across the ICILS countries, three-quarters of the students said they communicated with others by way of messaging or social networks at least weekly. Just over half said that they used the internet for “searching for information for study or school work” at least once a week, and almost half indicated that they engaged in “posting comments to online profiles or blogs” at least once each week. On average, there was evidence of slightly more frequent use of the internet for social communication and exchanging information among females than among males.

Students were also frequently using computers for recreation. On average across the ICILS countries, 82 percent of students reported “listening to music” on a computer at least once a week, 68 percent reported “watching downloaded or streamed video (e.g., movies, TV shows, or clips)” on a weekly basis, and 62 percent said they used the internet to “get news about things of interest,” also on a weekly basis. Just over half of all the ICILS students were “playing games” once a week or more. Overall, we recorded only a small, albeit statistically significant, gender difference in the extent of recreational use of computers, with males reporting slightly higher frequencies than females.

Students also reported using software applications outside school. Generally across the ICILS countries, the most extensive weekly use of software applications involved “creating or editing documents” (28% of students). Use of most other utilities was much less frequent. For example, only 18 percent of the students were “using education software designed to help with school study.” We found no significant difference between female and male students with respect to using software applications outside school.

Use of ICT for school work

Crossnationally, just under half (45%) of the ICILS students, on average, were using computers to “prepare reports or essays” at least once a week. We recorded a similar extent of use for “preparing presentations” (44%). Forty percent of students reported using ICT when working with other students from their own school at least weekly, and 39 percent of students reported using a computer once a week or more to complete worksheets or exercises.

Two school-related uses of computers were reported by less than one fifth of the students. These were “writing about one’s own learning,” which referred to using a learning log, and “working with other students from other schools.” Nineteen percent of students said they used a computer for the first of these tasks; 13 percent said they used a computer for the second.

The subject area in which computers were most frequently being used was, not surprisingly, information technology or computer studies (56%). On average, about one fifth of the students studying (natural) sciences said they used computers in most or all lessons. The same proportion reported using computers in most or all of their human sciences/humanities lessons. In language arts (the test language) and language arts (foreign languages), students were using computers a little less frequently: about one sixth of the students reported computer use in most or all lessons. Approximately one in seven students studying mathematics reported computer use in most mathematics lessons or almost every lesson. Of the students studying creative arts, just a little more than one in 10 reported computer use in most or all lessons.

The ICILS teacher questionnaire asked teachers to select one of their Grade 8 classes as a reference class and then to report their use of ICT in that class. The order of frequency of ICT use by subject was very similar to that reported by students. On average, the percentage of teachers using ICT was greatest if the reference class was being taught information technology or computer studies (95%), but it was also very high if the class was studying (natural) sciences (84%) or human sciences/humanities (84%). Seventy-nine percent of teachers whose reference class was engaged in language arts (test language) or language arts (foreign languages) reported using ICT in their teaching. Across countries, three quarters of teachers whose reference class was a creative arts class, and 71 percent of those teaching mathematics, said they used ICT in their teaching.

Students’ perceptions of ICT

The ICILS student questionnaire also gathered information about two aspects of student perceptions of ICT. One concerned students’ confidence in using computers (their ICT self-efficacy). The other was students’ interest and enjoyment in using ICT. The questions relating to students’ ICT self-efficacy formed two scales— basic ICT skills (such as searching for and finding a file) and advanced ICT skills (such as creating a database, computer program, or macro).

Some small gender differences were evident in basic ICT self-efficacy in seven countries, with males scoring lower than females in six of these countries. However, in the case of advanced ICT self-efficacy, males scored significantly and substantially higher than females in all 14 countries that met sampling requirements.

We found no consistent associations overall between advanced ICT self-efficacy and CIL scale scores, but did observe positive associations between basic ICT self-efficacy and CIL scale scores. This finding is not unexpected given the nature of the CIL assessment construct, which is made up of information literacy and communication skills that are not necessarily related to advanced computer skills such as programming or database management. Even though CIL is computer based, in the sense that students demonstrate CIL in the context of computer use, the CIL construct itself does not emphasize advanced computer-based technical skills.

Students were asked to indicate their agreement with a series of statements about their interest and enjoyment in using computers and doing computing. Overall, students expressed interest in computing and said they enjoyed it. Greater interest and enjoyment was associated with higher CIL scores, an effect that was statistically significant in nine of the 14 countries that met the ICILS sampling requirements.

Teacher, school, and education system characteristics relevant to CIL

General approaches to cil education.

The ICILS countries differed in terms of the characteristics of their education systems, their ICT infrastructure, and their approaches to ICT use.

Data from international databases show large differences among countries in their economies and (of particular relevance to this current study) ICT infrastructure. Data from the ICILS national context survey suggest that most of the participating countries were supportive at either the national or state/provincial level or both levels for using ICT in education. Plans and policies mostly included strategies for improving and supporting student learning and providing ICT resources.

International databases also show that countries differ with regard to including an ICT-related subject at the primary and lower-secondary levels of education. Although almost all of the ICILS countries had a subject or curriculum area equivalent to CIL at one or more levels of their respective education systems, fewer than half of the participating countries said their education system supported using ICT for student assessments. Across the countries, teaching CIL-related content was set within specific ICT-related subjects and was also regarded as a crosscurricular responsibility.

Teacher capacity to use ICT was rarely a requirement for teacher registration. However, teacher capacity to use ICT was often supported during preservice and inservice programs. In general, nearly all countries offered some form of support for teacher access to and participation in ICT-based professional development.

Teachers and CIL

Generally, the ICILS data confirm extensive use of ICT in school education. Across the ICILS countries, three out of every five teachers said they used computers at least once a week when teaching, while four out of every five reported using computers on a weekly basis for other work at their schools. As we commented in an earlier chapter, it is not possible to judge whether the reported level of use was appropriate, but we can agree that it was extensive.

Teachers in most countries were experienced users of ICT and generally recognized the positive aspects of using ICT in teaching and learning at school, especially with respect to accessing and managing information. On balance, teachers reported generally positive attitudes toward the use of ICT, although many teachers were aware that ICT use could have some detrimental aspects, such as adversely affecting students’ development of writing, calculation, and estimation skills.

In general, teachers were confident about their ability to use many computer applications; two thirds of them expressed confidence in their ability to use these technologies for assessing and monitoring student progress. There were differences, however, among countries in the level of confidence that teachers expressed with regard to using computer technologies, and younger teachers tended to be more confident ICT users than their older colleagues.

A substantial majority of the ICILS teachers were using ICT in their teaching. This use was greatest among teachers who were confident about their ICT expertise and who were working in school environments where there was collaboration about and planning of ICT use, and where there were fewer resource limitations to that use. These were also the conditions that supported teaching CIL. These findings suggest that if schools are to develop students’ CIL to the greatest possible extent, then teacher expertise in ICT use needs to be augmented, and ICT use needs to be supported by collaborative environments that incorporate institutional planning.

According to the ICILS teachers, the utilities (software) most frequently used in their respective reference classes were those concerned with wordprocessing, presentations, and computer-based information resources, such as websites, wikis, and encyclopedias. Teachers said that, within their classrooms, ICT was most commonly being used by their students to search for information, work on short assignments, and undertake individual work on learning materials. The survey data also suggest that ICT was often being used to present information in class and reinforce skills. Overall, teachers appeared to be using ICT most frequently for relatively simple tasks and less often for more complex tasks.

Schools and CIL

Data from the ICT-coordinator questionnaire showed that, in general, the schools participating in ICILS were well equipped in terms of internet-related and software resources. The types of computer resources available for use were more variable, however, with countries being less likely to have on hand tablet devices, a school intranet, internet-based applications for collaborative work, and a learning management system.

An examination of the ratio of number of students in a school per available computers showed substantial differences across countries. Ten of the 16 countries that met sampling requirements had more computers per student available in rural settings than in urban schools. We investigated the association between CIL and the ratio of students to computers in schools across countries and found that students from countries with greater access to computing in schools tended to have stronger CIL skills.

Computers in schools were most often located in computer laboratories and libraries. However, there was some variation among countries as to whether portable class-sets of computers or student computers brought to class were being used. Most schools had policies about the use of ICT, but there was substantial cross-country variation regarding policies relating to access to school computers for both students and members of the local community. The same can be said with regard to provision of laptops and other mobile learning devices for use at school or home.

The ICT-coordinators reported a range of hindrances to teaching and learning ICT. These typically related to resource provision and to personnel and teaching support. In general, the coordinators rated personnel and teaching support issues as more problematic than resource issues. However, there was considerable variation across schools within countries and across countries in the types of limitation arising from resource inadequacy.

Variation was also evident in the level of teachers’ agreement with negatively worded statements about the use of ICT in teaching at school. Statements reflecting insufficient time to prepare ICT-related lessons, schools not viewing ICT as a priority, and insufficient technical support to maintain ICT resources all attracted relatively high levels of teacher agreement.

Both teachers and principals provided perspectives on the range of professional development activities relevant to pedagogical use of ICT. According to principals, teachers were most likely to participate in school-provided courses on pedagogical use of ICT, to talk about this type of use when they were within groups of teachers, and to discuss ICT use in education as a regular item during meetings of teaching staff. From the teachers’ perspective, the most common professional development activities available included observing other teachers using ICT in their teaching, introductory courses on general applications, and sharing and evaluating digital resources with others via a collaborative work space.

Results from the multivariate analyses

These results showed that students’ experience with computers as well as regular home-based use of computers had significant positive effects in many countries, even after we had controlled for the influence of personal and social context. ICT resources, particularly the number of computers at home, no longer had effects once we took socioeconomic background into account.

Only a few countries recorded significant influences of school-level variables on CIL, and some of these associations were not significant after we controlled for the effect of the school’s socioeconomic context.

In a number of education systems, the extent of students’ computer use (at home) and the extent to which students had learned about ICT-related tasks at school appeared to be influencing students’ CIL. There is much potential here for secondary analyses directed toward further investigating the associations between CIL education and CIL outcomes within countries.

Reflections on policy and practice

The findings from ICILS 2013 can be considered to constitute two broad categories: the nature and measurement of CIL, and factors that relate to CIL proficiency.

ICILS has provided a description of the competencies underpinning CIL that incorporates the notions of being able to safely and responsibly access and use digital information as well as to produce and develop digital products. ICILS has also provided an empirically derived scale and description of the CIL learning progress that can be used to anchor interpretations of learning in this field. It furthermore provides a common language and framework that policymakers and scholars can use when deliberating about CIL education. This common framework and associated measurement scale also offer a basis for understanding variation in CIL at present and for monitoring change in the CIL that results from developments in policy and practice over time.

Some of the findings of this report are similar to those of crossnational studies in other learning areas. For example, students from economically and socially advantaged backgrounds typically have higher levels of achievement. However, other findings relate specifically to the development of CIL through education.

One question raised by the ICILS results relates to the place of CIL in the curriculum. While many countries have some form of subject and curriculum associated with CIL, responsibility for addressing and assessing the relevant learning outcomes is less clear. Countries generally appear to use a combination of information technology or computer studies classes together with the expectation that the learning outcomes associated with CIL are a crosscurricular responsibility shared across discipline-based subjects.

The ICILS data show that teaching emphases relating to CIL outcomes were most frequently being addressed in technology or computer studies classes and in (natural) sciences and human sciences or humanities classes. Teachers and students differed in their perceptions of computer use across the subjects. Queries remain, however, about how schools maintain the continuity, completeness, and coherence of their CIL education programs. This last concern had particular relevance in several ICILS countries, where there was only limited, nonobligatory assessment of CIL-related competences, or where assessment took place only at the school level.

A second question relates to the role of ICT resource availability and its relationship to CIL. Overall, the ICILS data suggest that increased access to ICT resources at home and school are associated with higher levels of CIL, but only up to a certain point, as is evident at the different levels of our analyses. At the student level, each additional computer at home was associated with an increase in CIL. At the national level, higher average levels of CIL were associated with higher country rankings on the ICT Development Index (see Chapter 1 ), and lower ratios of students to computers. These associations are somewhat difficult to interpret fully given that higher levels of CIL resourcing are typically associated with higher levels of economic development, which itself has a strong positive association with CIL.

The ICILS results also suggest that the knowledge, skills, and understandings that comprise CIL can and should be taught. To some extent, this conclusion challenges perspectives of young people as digital natives with a self-developed capacity to use digital technology. Even though we can discern in the ICILS findings high levels of access to ICT and high levels of use by young people in and (especially) outside school, we need to remain aware of the large variations in CIL proficiency within and across the ICILS countries.

The CIL construct combines information literacy, critical thinking, technical skills, and communication skills applied across a range of contexts and for a range of purposes. The variations in CIL proficiency show that while some of the young people participating in ICILS were independent and critical users of ICT, there were many who were not. As the volume of computer-based information available to young people continues to increase, so too will the onus on societies to critically evaluate the credibility and value of that information.

Changing and more sophisticated technologies (such as social media and mobile technologies) are increasing the ability of young people to communicate with one another and publish information to a worldwide audience in real time. This facility obliges individuals to consider what is ethically appropriate and to determine how to maximize the communicative efficacy of information products. The knowledge, skills, and understandings that are the basis of the receptive and productive aspects of CIL can and need to be taught and learned through coherent education programs. The knowledge, skills, and understandings described in the CIL scale show that, regardless of whether or not we consider young people to be digital natives, we would be naive to expect them to develop CIL in the absence of coherent learning programs.

One message from the ICILS teacher data is that a certain set of factors appears to influence their confidence in using ICT and integrating CIL in their teaching. It is therefore worth repeating here that teachers’ ICT use was greatest when the teachers were confident about their expertise and were working in school environments that collaborated on and planned ICT use and had few if any resource limitations hindering that use. These were also the conditions that supported teachers’ ability to teach CIL.

Once threshold levels of ICT resourcing have been met in a school, we suggest that system- and school-level resourcing and planning should focus on increasing teacher expertise in ICT use. Attention should also be paid to implementing supportive collaborative environments that incorporate institutional planning focused on using ICT and teaching CIL in schools.

ICILS also showed differences in teacher attitudes toward and self-efficacy in using ICT in their teaching. Older teachers typically held less positive views than younger teachers about using ICT and expressed lower confidence in their ability to use ICT in their teaching practice. Programs developed to support teachers gain the skills and confidence they need to use ICT effectively would be valuable for all teachers. Consideration should also be given to ensuring that these programs meet the requirements of older teachers and, in some instances, directly target these teachers.

The ICILS results also call into question some of the idealized images commonly associated with visions of ICT in teaching and learning. In ICILS, both students and teachers were asked about students’ use of computers in classes. Students reported most frequently using computers to “prepare reports or essays” and “prepare presentations” in class, and using utilities to “create or edit documents” out of school. When teachers were asked to report on their own use of ICT in teaching, the two practices reported as most frequent were “presenting information through direct class instruction” and “reinforcing learning of skills through repetition of examples.” Although teachers reported high levels of access to and use of ICT in their professional work, including in the classroom, the ICILS data suggest that computers were most commonly being used to access digital textbooks and workbooks rather than provide dynamic, interactive pedagogical tools.