Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Patient Mrs. B.C. is a 56 year old female who is presenting to her WHNP for her annual exam. She had to cancel her appointment two months ago and didn’t reschedule until now. Her last pap smear and mammogram were normal. Today, while performing her breast exam, her nurse practitioner notices dimpling in the left breast as the patient raises her arms over her head. When the NP mentions it to Mrs. B.C. she is surprised and denies noticing it before today. A firm, non-tender, immobile nodule is palpated in the upper quadrant of her breast . The NP then asks Mrs. B.C. how frequently she is performing breast self-exams, she admits to only doing them randomly when she remembers, which is about every few months. She reports no recent or abnormal drainage from her breast. Further examination reveals palpable axillary lymph nodes.

Mrs. B.C. is about 30 pounds overweight and walks her dog around her neighborhood every morning before work and every evening when she gets home. She reports drinking a glass of white wine before bed each night. She denies any history of tobacco use. She reports use of a combination birth control pill on and off for 25 years until she reached menopause. She is not currently taking any prescription medications.

Past Medical History

- Menarche (Age 10)

- Post-menopausal (Age 53)

- No other pertinent medical history

Family History:

- Father George- deceased from stroke (75 years old), history of hypertension, CAD, HLD

- Mother Maryanne alive- 76 years old, history of dementia, osteoporosis

- Brother Michael- alive, 57 years old, history of hypertension, CAD and cardiac stent placement (54 years old)

- Sister, Michelle- alive 53 years old, history of GERD, Asthma

- Brother- Jimmy- alive 50 years old, no past medical history

Social History:

Mrs. B.C. works Monday-Friday 8am-5pm at the local dentist’s office at the front desk as a schedule coordinator. She is planning to retire in a few years. In her spare time, she is involved in various community efforts to feed the homeless and helps to prepare dinners at her local church one night a week. She also enjoys cooking and baking at home, gardening, and nature photography.

Mrs. B.C. has two children. Her oldest son, Patrick, is 21 years old and is in his final year of pre-med. He is attending a public university about 2 hours away from home where he lives year-round. As an infant, Patrick was breastfed until 18 months when he self-weaned. Her daughter, Veronica, is 19 years old and lives at home while attending the local branch campus of a state university. She is in her second year of a business degree and then plans to transfer to the main campus next year. When Veronica was an infant she had difficulty latching onto the breast due to an undiagnosed tongue and lip ties resulting in Mrs. BC exclusively pumping and bottle feeding for six months. After six months, Mrs. B.C. was having a hard time keeping up while working and her found her supply diminished. Veronica had begun eating solid foods so Mrs. B.C. switched to supplemental formula, which was a big relief.

Mrs. B.C. was married to her now ex-husband Kent for 26 years. They divorced two years ago when Veronica was a senior in high school. They have remained friends and Kent lives 25 minutes away in a condo with his girlfriend. She also has two brothers who live nearby and a sister who lives out of state. Her 7 nieces and nephews range in age from 9 years old to 26 years old. Her father, George, passed away from a sudden stroke 4 years ago. Her mother, Maryanne, has dementia and is living in a nearby memory care facility. She also has many close friends.

Lessons learned from COVID-19: improving breast cancer care post-pandemic from the patient perspective

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2024

- Volume 32 , article number 338 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Charlotte Myers 1 ,

- Kathleen Bennett 2 &

- Caitriona Cahir 2

162 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Since the onset of the pandemic, breast cancer (BC) services have been disrupted in most countries. The purpose of this qualitative study is to explore the unmet needs, patient-priorities, and recommendations for improving BC healthcare post-pandemic for women with BC and to understand how they may vary based on social determinants of health (SDH), in particular socio-economic status (SES).

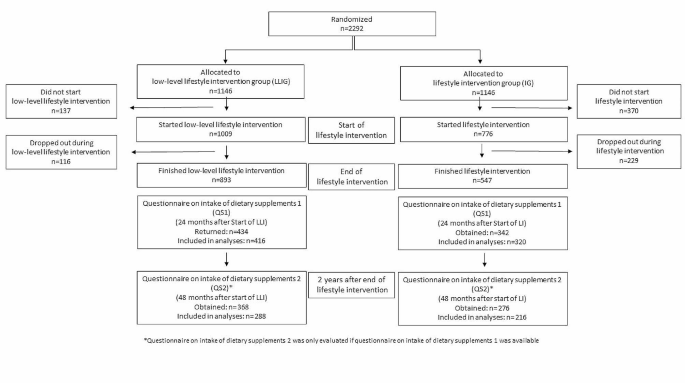

Thirty-seven women, who were purposively sampled based on SDH and previously interviewed about the impact of COVID-19 on BC, were invited to take part in follow-up semi-structured qualitative interviews in early 2023. The interviews explored their perspectives of BC care since the easing of COVID-19 government restrictions, including unmet needs, patient-priorities, and recommendations specific to BC care. Thematic analysis was conducted to synthesize each topic narratively with corresponding sub-themes. Additionally, variation by SDH was analyzed within each sub-theme.

Twenty-eight women (mean age = 61.7 years, standard deviation (SD) = 12.3) participated in interviews (response rate = 76%). Thirty-nine percent ( n = 11) of women were categorized as high-SES, while 61% ( n = 17) of women were categorized as low-SES. Women expressed unmet needs in their BC care including routine care and mental and physical well-being care, as well as a lack of financial support to access BC care. Patient priorities included the following: developing cohesion between different aspects of BC care; communication with and between healthcare professionals; and patient empowerment within BC care. Recommendations moving forward post-pandemic included improving the transition from active to post-treatment, enhancing support resources, and implementing telemedicine where appropriate. Overall, women of low-SES experienced more severe unmet needs, which in turn resulted in varied patient priorities and recommendations.

As health systems are recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, the emphasis should be on restoring access to BC care and improving the quality of BC care, with a particular consideration given to those women from low-SES, to reduce health inequalities post-pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Access to health services among culturally and linguistically diverse populations in the Australian universal health care system: issues and challenges

Connecting communities to primary care: a qualitative study on the roles, motivations and lived experiences of community health workers in the Philippines

COVID-19 impact on urban low-income individuals in Bangladesh: a qualitative content analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Globally, health services for breast cancer (BC) across the cancer continuum were significantly disrupted and compromised due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic [ 1 ]. Breast screening services were curtailed or paused during periods of COVID-19 restrictions [ 2 ]. Active cancer treatment, such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, was disrupted and/ or modified to account for the level of restrictions in place [ 3 , 4 ]. Post-treatment care (i.e., routine care), which includes mammograms, follow-up appointments, blood tests, and other scans, was significantly disrupted during the pandemic [ 5 ]. Support services, which address the multi-disciplinary needs of those living with a diagnosis of cancer, including physiotherapy and psycho-oncology, were paused or modified during the pandemic [ 6 , 7 ].

Breast screening services generally resumed after government restrictions were lifted [ 8 ]; however, the impact of pausing breast screening services on BC diagnoses is only now becoming apparent with later stage and more symptomatic BC diagnoses [ 9 ] which may have a negative impact on survival rates in the future [ 10 ]. Furthermore, the issue of backlogs and waiting lists across the cancer continuum is continuing [ 11 ]. There are likely to be considerable unmet needs in healthcare for women with BC due to barriers such as availability, affordability, accessibility, and acceptability of BC services [ 12 ] which were apparent during the pandemic. Unmet needs, which can be measured by the difference between required healthcare services and received healthcare services, can assess the effectiveness in healthcare delivery [ 13 ]. A failure to address unmet needs can have a negative impact on an individual’s quality of life and other health outcomes [ 14 ]. Previous research conducted during the pandemic identified unmet needs for individuals living with a diagnosis of BC such as psychological and emotional support, management of side effects, complementary therapy, communication among healthcare providers, local health care services, and transportation [ 15 ]. However, similar research has not been conducted qualitatively post-pandemic to identify lasting unmet needs.

Considering the long-lasting consequences of the pandemic, the acquired knowledge and experience from COVID-19 can be used by healthcare providers and policy makers to improve BC care and to prepare health systems for future unexpected events [ 16 ]. Historically, pandemics and other crises have provided opportunities to strengthen health systems by exploiting faults in the pre-existing health system and exacerbating pre-existing health inequalities [ 17 ]. For example, low socio-economic status (SES) has been associated with higher disease burden [ 18 ] and decreased access to healthcare [ 19 ]. Within the context of non-communicable diseases, including BC, the social determinants of health (SDH) framework have been applied to the COVID-19 pandemic to explain health disparities [ 20 ]. Specific to BC care, SDH identified during the pandemic include age, race, insurance status, and region (1); however, it is unknown whether these SDH persist post-pandemic. Therefore, health systems should respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by addressing the multidisciplinary and personalized needs of all individuals to improve health equality.

The reorganization of BC services during the pandemic provides an opportunity to improve overall BC care and the experience and priorities of women with BC. To effectively address the needs of individuals, the patient experience and voice is integral for healthcare improvement. The aims of this qualitative study are (i) to explore and identify the unmet needs, patient-priorities, and recommendations for improvements in BC healthcare post-pandemic and (ii) to understand how they may vary for women with BC according to SDH, in particular SES.

Study design

A qualitative exploratory study was conducted using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines [ 21 ].

Participants

Women with BC were initially enrolled into a prospective cohort study measuring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on BC healthcare services and women’s well-being using a questionnaire ( N = 387) [ 22 ]. In total, 37 women from this cohort, purposively sampled based on SDH, were interviewed about their experience of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care and well-being during the pandemic [ 23 ]. These 37 women were invited to take part in a follow-up qualitative study to explore the impact of COVID-19 post-pandemic on BC care. The initial SDH sampling strata in the baseline interviews were further refined to include age, education level, annual income, work status, health insurance, and region. SES was established by considering annual income, education level, and health insurance status, respectively. Regarding health insurance status in Ireland, eligibility for entire public coverage through a medical card is based primarily on income, while health status and age are also considered. A medical card entitles the individual to primary care and hospital services free at the point of access; however, only 32% of the population are eligible for such coverage [ 24 ]. This eligibility structure causes inequalities for health services [ 25 ]. Thus, nearly 50% of Irish citizens seek out additional private, or voluntary, health insurance for quicker access to care [ 26 ]. Additional clinical information was obtained from the survey components, including year of diagnosis and cancer stage. Further information on the overall study design, participant recruitment, and sampling strata can be found in Supplementary 1 .

Data collection

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted between January and March 2023 via Microsoft Teams (General Data Protection Regulation compliant) using a topic guide developed from the analysis of the baseline qualitative study [ 23 ] and baseline and follow-up survey study [ 22 ] by two qualitatively trained researchers (CM, CC). The topic guide included questions to explore women’s experiences and perspectives of BC care since the easing of COVID-19 government restrictions, including unmet needs, patient priorities, and recommendations specific to BC care. The topic guide was adjusted by removing, adding, or rewording questions during the interview process, a process known as reflexivity in qualitative research, which reduces researcher bias in data collection [ 27 ]. The final topic guide can be found in Supplementary 2 . The interviews were anonymised and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Interviews were analyzed using a codebook approach to thematic analysis within NVivo software, which identifies themes early in the analysis process and subsequently maps concepts around central patterns or relationships within the data [ 28 ]. The codebook approach utilizes both deductive reasoning (e.g., the creation of the topic guide as a preliminary codebook, aligning with the research objectives) and inductive reasoning (e.g., the addition of topics and codes as the interviews was conducted). The codebook approach to thematic analysis was conducted using the following steps: identifying existing code sources/code development; familiarization with new data, generating additional codes, identifying patterns around codes for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report [ 28 , 29 ]. The data was organized by themes, summarized by sub-themes, and illustrated with quotations. Furthermore, cross-tabulation within NVivo was used to explore any variation in themes and sub-themes by SDH to associate patterns in variation. Evident variations were identified with a difference in proportion greater than 20%. SDH were then interpreted within the corresponding themes and sub-themes.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Office for National Research Ethics Committee in Ireland (20-NREC-COV-078). Participation was voluntary, and participants were able to withdraw their consent at any point throughout the research study.

Participant characteristics

The follow-up interview study included 28 of the original participants which was a 76% response rate from the baseline interview study. There were nine women who were either lost to follow-up, uninterested, or deceased. Table 1 presents the clinical and demographic data of participants interviewed at follow-up. The average age for women in the study was 61.7 years (standard deviation (SD) = 12.3). Over half of women were diagnosed prior to 2020 (57%) and the majority of women reported an early stage (e.g. stage I–II) diagnosis (68%). Fifty-four percent of women were highly educated, and 68% of women reported not working due to unemployment, retirement, or as a result of BC. Half of women (50%) reported an annual household income of less than €40,000. Furthermore, 39% ( n = 11) of women were categorized as high SES, while 61% ( n = 17) of women were categorized as low SES. Supplementary 3 presents the refined SDH sampling strata by participant.

The three main themes, along with their sub-themes and corresponding codes, are described narratively below, and also summarized in Table 2 . SES was the only SDH that was associated with varied themes and sub-themes; therefore, SES is integrated narratively when evident.

Unmet needs in BC health care

Most women ( n = 26, 98%) mentioned at least one on-going unmet need specific to their BC health care, which negatively impacts their overall well-being since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unmet needs in routine care for BC

Post-treatment care (i.e., routine care) includes follow-up appointments, exams, scans, and other tests that occur after active treatment, and most women reported an unmet need regarding their routine care ( n = 21). Many women experienced persisting delays and/or cancellations ( n = 16) since the pandemic. A higher proportion of women with low SES reported disruptions ( n = 12, 71%) compared to women with high SES ( n = 4, 36%) for routine appointments. Overall, these reported delays and/or cancellations were typically rescheduled and/or modified; however, women were dissatisfied without in-person annual mammograms: “Now, it was a drawback not being able to have my mammogram for two years and, well, I was keeping up with, you know, with my examinations myself, so I was kind of half OK, you know, that if anything was there, I would have felt it.” (P6, low SES).

Regarding routine care, many women expressed difficulty contacting their BC team ( n = 17). Additional concerns included delays with breast reconstruction procedures ( n = 6) and BC medication ( n = 11). A higher proportion of women from low SES backgrounds reported medication difficulties ( n = 9, 53%) compared to women from higher SES background ( n = 2, 18%), including disruptions with supply of BC medications and a lack of support for the side effects and consequences from tamoxifen: “When I was given tamoxifen, I wasn’t aware that other medications could actually reduce its’ effectiveness. That was something I discovered during the year, myself, on my own. So I had to bring that to the attention of my doctors and request that they be changed.” (P8, low SES).

Unmet needs in mental and physical healthcare

The combination of experiencing COVID-19 and having BC exacerbated both physical health and mental health for women, regardless of SES: “But the last six or eight months, again, I have felt very un-well and it just can’t be gotten to the bottom of, medically, you know… I don’t know whether it’s right or wrong or appropriate to attribute it to COVID or post-pandemic or is it just a fact of life post cancer?” (P28, high SES).

For physical health ( n = 13), women noted developing pain, co-morbidities, and fatigue which was attributed to the disruption and lack of access to healthcare services during the pandemic: “That side of my arm and breast is very sore, so maybe if I was going to physio, it mightn’t be so bad. It’s hard to lift up that arm. It’s very, very sore.” (P16, low SES).

For mental health ( n = 18), women expressed persisting depression, anxiety, and fear of cancer recurrence, which they believed would have improved post-pandemic, if they were able to access treatment: “Now I find in the last sort of six months, I’m struggling mentally. I’m a bit overwhelmed at times. I think that would be the best way to put it. And you know, the impact now of it, I suppose, is really taking effect now because you are dealing with the treatments and stuff like that. (P2, low SES).

However, these mental health needs were infrequently addressed through their BC care: “But they need to be more aware of the mental… health side of it as well. I don’t think there’s anything, well look, there is nothing done, there’s nothing there for it. That’s not part of the treatment plan and I think it should be.” (P7, low SES).

Unmet financial support to access BC healthcare

Throughout the pandemic, some women experienced financial difficulties ( n = 10), including disruption to work and income due to BC and/or COVID-19, resulting in an inability to pay for BC services and medications, and transportation issues. A higher proportion of women with low SES reported financial difficulties ( n = 9, 53%) compared to women with high SES ( n = 1, 9%): “And I wasn’t working, so I had no money at all. And so, I got sorted out. Well, it took a while and I think that’s hard on people because I had to like, actually beg for a medical card because I wasn’t even going to get the operation because I had no money to pay for an operation.” (P1, low SES).

The lack of financial support is still evident and on-going post-pandemic: “I have the hormone medication, the breast cancer one. So it is, that’s a bit of a pain every three months, having to pay that.” (P13, low SES).

Patient priorities for BC healthcare

Women proposed priorities for their BC care ( n = 28); which were personalized and included improving their health-related anxiety and overall well-being.

Cohesion in BC healthcare

Cohesion among multidisciplinary BC care (e.g., oncology, surgery, radiotherapy, GP, physiotherapy, psychology, and pharmacy), spanning from diagnosis through post-treatment care, was a top priority for all women ( n = 28). However, women’s experience with cohesive BC care varied; the majority of women described adequate BC cohesion ( n = 18); however, of the women who described poor BC cohesion ( n = 10), a higher proportion was of low SES ( n = 8, 80%): “It didn’t feel linked… it almost felt a bit like a conveyor belt system. And you know…you could be with radiology and you might say something or have a concern and they’d be like, well, that’s not really our department. So you need to phone oncology.” (P7, low SES).

Women with poor BC cohesion expressed that the different elements for BC care (e.g. radiology, oncology) were not linked and those who attended appointments in varying BC clinics addressed concern regarding clarity in patient information: “When you’re coming in as a patient, they should know your history… Like I’ve been asked, ‘So you had cancer on the left?’ And then I said, ‘Yeah but I had double mastectomy.’ ‘Oh, I didn’t know that’, you know? They’re the type of things you should know as a doctor or a nurse…you should read the notes. They should have a preliminary page that says this patient has had this, this, and this.” (P3, low SES).

On the other hand, women expressed better cohesion with continuity and on-going monitoring with BC health professionals post-treatment: “Now I’m really lucky because we know they’re there. So, for instance, next month I’m having… a breast CT…so I’m kind of back into six-monthly checks now again. So that’s where I am at the moment, [I’m] being watched quite carefully now.” (P23, high SES).

Many women discussed the importance of efficiency with appointments ( n = 13), including timely results and less delays: “I think the fact that the hospital…quite quickly geared up to being very, very efficient and they dealt with people when they arrived and soon as you were kind of finished, you were let go. There wasn’t any of the delays that would have been before.” (P24, high SES).

Communication with and between BC healthcare providers

Proper communication, including consistency and understandability, with health professionals was another top priority for women interviewed in the study ( n = 28). All women who expressed adequate cohesion in their BC care attributed it to good communication ( n = 18): “Since [the pandemic], it has been the same, consistent. If they give me an appointment, it goes ahead and there’s no changes. If you ring them… they answer the phone and you get on to them and you know the details are there and so everything is fine from that point of view.” (P21, high SES).

However, poor communication was a common concern for some women ( n = 10), and women’s experience with poor communication was attributed to the unmet need of fall-out from routine care: “It’s communication. It always comes back to communication, doesn’t it? And if you had somebody that you could just have a 5-min conversation with an’ it’s kind of like, just give me your opinion. Hear me. Hear me. First of all.” (P18, high SES).

To enhance communication, many women mentioned the use of telemedicine ( n = 21), especially during the pandemic when in-person appointments were limited: “To know that there was somebody picking up your file, looking at it, picking up the phone and checking in with you. It was very reassuring.” (P6, low SES).

Indeed, there were differences in women’s experiences with communication. Similar to cohesion, 80% ( n = 8) of women who expressed poor communication were of low SES, even with the use to telemedicine: “The phone call, like I said, you were just talking… there were no personal details. You know, you couldn’t show [them anything] over the phone.” (P9, low SES).

Additionally, women described the role of a BC nurse, junior doctor, or GP as an integral component to their BC care to enhance both communication and cohesion: “That continuity of care was very important… I found my oncology link nurse was extremely supportive… And I got that. But I imagine not everyone probably is that lucky.” (P20, high SES).

Patient empowerment in BC healthcare

Empowerment was another top priority, and most women ( n = 20) described the ability to be an active participant in their BC care. The personalization of BC care enhanced patient empowerment: “Everybody has different needs and different wants. And what I would find satisfactory, somebody else wouldn’t, you know?” (P10, low SES).

Furthermore, proper education and knowledge on BC treatment and results also improved mental well-being: “They really kind of involved me in a sense, showed me the evidence. And that really made a difference. I mean, that melted away any lingering anxiety I had. Now I’m just a new person. That could make a huge difference to somebody.” (P8, low SES).

However, several women did not experience empowerment and involvement within their BC care ( n = 5), which was more common among women of low SES ( n = 4, 80%). This lack of control caused health-related anxiety and worry: “It’s the effects of all the other things, you know? I find that a bit problematic… It’s a struggle. I don’t know what anyone even could do about it because I don’t know even myself.” (P1, low SES).

Women also discussed the importance of managing their BC care by understanding their specific pathway for treatment and care, and being aware of next steps: “I had my plan set out for me from the beginning of where we were going. Chemo, surgery, radiation. So you knew all that, which was great. You know, you weren’t second guessing it all the time. You knew you had a plan and the plan was going to plan.” (P2, low SES).

Recommendations to improve BC healthcare

Considering their unmet needs and priorities for proper and personalized BC care, all women ( n = 28) proposed improvements and recommendations to enhance BC care moving forward post-pandemic. Most of the recommendations addressed an unmet need and/or a patient priority.

Transition from active treatment to post-treatment

To address the unmet need of routine care fall-out, many women ( n = 17) suggested ways to improve the transition from active to post-treatment, a period of time when women feel abandoned from their habitual BC care. Women proposed continuity in care through continued contact with a designated BC nurse: “I think that could help a lot of people out, if you could ring the nurse and they could tell you what’s going on. It might be something very simple or, you know…it’s something that’s part of [the BC] because, as you know, the side effects are massive from medications.” (P17, low SES).

Women expressed the desire for clear communication on their BC care plan post-treatment: “I didn’t feel that they gave you…a little pamphlet or booklet or something that could give you directions if you have anything, anxieties… How do you get back into your normal life? And how do you deal with maybe upcoming events, something like that? It was just like dead stop.” (P2, low SES).

The promotion of local cancer support centers from the BC care team was a common suggestion to enhance the transition from active treatment to post-treatment: “There should be something, a follow-up from your treatment, as in a nurse even saying to you, ‘look, I think you should contact your local [support centre]’ or something but like I, I literally finished my treatment and that was it.” (P4, low SES).

Likewise, the use of local cancer support centers offered women supportive care to address physical and mental health unmet needs: “That psych-oncologist was brilliant and she arranged… she gave me the name and number of somebody in [support centre] to ring, which I did. And she said, ‘I think these services, these things, the thrive and survive… this would be really beneficial for you.’” (P18, high SES).

Support resources for BC care

In addition to support centers, many women ( n = 18) expressed the importance of support resources for their BC care to improve the transition from active treatment. To address the unmet need of financial support within BC care, women ( n = 9) suggested ways to improve the barrier of healthcare costs specific to BC: “Look, there’s definitely…grants and stuff like that. I never chase them because they made it too difficult for you to access. When you’re in the midst of a diagnosis and you’re trying to process everything, the last thing you want to do is go through your emails, try find pay slips and try to find, you know, bank statements…a letter from your oncologist should be enough. You know?” (P7, low SES).

Women also recommended ways to improve the patient experience with general issues such as transportation ( n = 8): “And I do think the volunteer drivers with the [support centre] that’s a massive plus. That’s how I used to get in because I would be very dopey when I finished treatment, so I wasn’t, it wasn’t safe for me to drive, so they were huge resource … and I wasn’t made aware of that in the hospital.” (P19, high SES).

Specific to BC, women discussed BC specific resources such as bras and wigs ( n = 9); however, there was limited knowledge on the accessibility and availability of such resources: “I’m only talking about what’s available locally… I don’t think there are those things here. Even down to…getting a proper fitting bra or where to go for it… I didn’t seem to realize that the mastectomy bra… you get those cheap or free for your first one.” (P27, high SES).

Telemedicine

The use of telemedicine was common throughout the pandemic ( n = 21), and women recommended the adaptation of telemedicine moving forward post-pandemic when feasible ( n = 7): “The use of technology has been…a positive. If I was to turn around and say, ‘can I have a video, you know, a phone consultation?’ I think most of the time, it wouldn’t be a problem if you were to ask for that rather than just having an actual face-to-face.” (P23, high SES).

More so, the adaptation of telemedicine can eliminate transportation barriers and reduce time spent waiting for appointments: “They were useful in the pandemic in that you couldn’t physically be in the same spot. You know, we were in lockdown. And I actually think sometimes it’s better to be able to do that rather than going up to spend 3 or 4 h in the hospital waiting to speak to somebody.” (P3, low SES).

The current study found that women with a diagnosis of BC are experiencing many unmet needs associated with their BC care post-pandemic. Unmet needs included disruption and discontinuation of routine BC care, a lack of treatments and support services to address women’s mental and physical well-being, and a lack of financial support for those women of low SES to help them access and obtain BC care. Considering such unmet needs, women identified their priorities for receiving adequate BC care and further proposed recommendations for improving BC care in the future. Cohesion within BC health care delivery and improved communication among BC healthcare providers were considered top priorities, both of which were perceived to empower women in managing their BC care. The following three recommendations addressed unmet needs and patient priorities: (1) improving the transition from active to post-treatment care, (2) enhancing and promoting support resources, and (3) appropriate adaptation of telemedicine.

Unmet supportive care needs were common for all BC patients throughout the pandemic, including physical and psychological needs, communication with clinicians, health system information needs, and other financial and social needs [ 30 ]. A previous quantitative study conducted during the pandemic found that unmet needs for BC survivors can be addressed with either comprehensive care or psychological and emotional support and women who reported more unmet needs also reported a significantly lower quality of life [ 15 ]. The results of our study found that women of low SES experienced greater disruption to routine care and increased financial difficulties specific to BC, which is consistent with research conducted prior to the pandemic [ 31 ]. It is likely the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing socio-economic inequalities in BC care; therefore, women who experienced greater unmet needs should be reintegrated into routine BC care along the entire cancer continuum [ 22 ].

The identification of patient priorities for personalized BC care ensures equality in BC care [ 32 ]. The women in our study identified cohesion and communication as top priorities; however, poorer cohesion and communication were both common for women from lower SES backgrounds. Personalized BC care should address comprehensive continuity for all women, regardless of SES, to improve equity in healthcare services. Women in this study proposed improving the transition from active to post-treatment by having a designated, or liaison, healthcare professional to support them with the transition. Research has shown the multidisciplinary benefits of a liaison nurse for cancer care, including physical, psychosocial, and communicative outcomes [ 33 ]. Cancer support centers also improve the transition from active treatment by providing cancer survivors a social and community network to address multidisciplinary needs [ 34 ]. However, the pandemic created barriers towards accessing such resources. Women should be made more aware of the availability of these centers, and other supportive care, directly from their BC care team.

Providing financial aid and transportation means to women in need, especially women from low SES backgrounds, can address health inequalities specific to accessing and obtaining BC care [ 35 ]. Strategies from a health systems level for reducing cancer-related inequalities include enhancing patient navigation along the cancer continuum and integrating telemedicine for routine care [ 36 ]. Furthermore, transportation barriers and auxiliary costs can be addressed with telemedicine, which was a widely utilized practice during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 37 ]. In addition, telemedicine can improve communication with continued contact with BC health professionals. As BC services recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, consideration should be given to the use of telemedicine in BC care and how it could be used more effectively to support women.

Strengths and limitations

The study has a number of strengths including the large number of women interviewed and the selection via stratified purposive sampling to ensure diverse representation. This study is one of few studies to associate SDH, in particular SES, with BC care experience. The interviews were conducted immediately following COVID-19 government restrictions; therefore, they were timely and represent experiences of the transition from pandemic restrictions. There is limited research post-pandemic from the patient perspective; therefore, it addresses an evidence gap. However, there are several limitations to the study regarding generalizability. The participants do not represent all women living with a diagnosis of BC. The study was conducted in Ireland, a country which experienced severe and longer periods of restrictions compared with other countries [ 38 ]. Ireland remains the only country within the European Union without universal healthcare, and health inequalities have been associated with health insurance status and SES [ 39 ]. To enhance health equality in BC care, the findings from this research, in tandem with previous related research conducted during the pandemic [ 22 ], suggest that all women with a diagnosis of BC should be entitled to a medical card to assist with healthcare costs, if needed. Despite differences in health care systems, women with BC may be experiencing similar unmet needs across different countries and further research across countries with varying health care systems is needed to fully understand unmet needs for women with BC post-pandemic and inequities in these unmet needs. Additional future research may include comparing individual SDH characteristics to determine what SDH characteristics have a greater influence on women’s experience with BC care.

The pandemic has impacted BC services considerably for women in Ireland with BC, and this study has identified a range of unmet needs in BC care, patient-centered priorities, and recommendations for addressing these unmet needs. These priorities and recommendations align with the goals of the national cancer strategy, which aims to put structures in place to allow for increased patient involvement in the delivery of BC care going forward [ 40 ]. As health systems are recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, the emphasis should be on both restoring access to BC care and improving the quality of BC care to achieve the best possible health outcomes for women living with and beyond a diagnosis of BC. Particular consideration needs to be given to those women from lower socioeconomic groups, in order to reduce health inequalities, which have been further exacerbated by the pandemic. As health systems are recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, an emphasis to restore and enhance better BC care should be essential, with consideration and emphasis from the patient perspective.

Myers C, Bennett K, Cahir C (2023) Breast cancer care amidst a pandemic: a scoping review to understand the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on health services and health outcomes. Int J Qual Health Care 35(3)

Vanni G, Pellicciaro M, Materazzo M, Bruno V, Oldani C, Pistolese CA et al (2020) Lockdown of breast cancer screening for COVID-19: possible scenario. In Vivo 34(5):3047–53

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gasparri ML, Gentilini OD, Lueftner D, Kuehn T, Kaidar-Person O, Poortmans P (2020) Changes in breast cancer management during the Corona Virus Disease 19 pandemic: an international survey of the European Breast Cancer Research Association of Surgical Trialists (EUBREAST). Breast 52:110–115

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lee J, Jung JH, Kim WW, Park CS, Park HY (2020) Patterns of delaying surgery for breast cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu. South Korea Front Surg 7:576196

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mo A, Chung J, Eichler J, Yukelis S, Feldman S, Fox JL et al (2021) Breast cancer survivorship care during the COVID-19 pandemic within an urban new york hospital system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 111(3):e169–e170

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Helm EE, Kempski KA, Galantino MLA (2020) Effect of disrupted rehabilitation services on distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rehabil Oncol 38(4)

Archer S, Holch P, Armes J, Calman L, Foster C, Gelcich S et al (2020) “No turning back” psycho-oncology in the time of COVID-19: insights from a survey of UK professionals. Psychooncology 29(9):1430–1435

Pairawan SS, Olmedo Temich L, de Armas S, Folkerts A, Solomon N, Cora C et al (2021) Recovery of screening mammogram cancellations during COVID-19. Am Surg 87(10)

Toss A, Isca C, Venturelli M, Nasso C, Ficarra G, Bellelli V et al (2021) Two-month stop in mammographic screening significantly impacts on breast cancer stage at diagnosis and upfront treatment in the COVID era. ESMO Open 6(2)

Sprague BL, Lowry KP, Miglioretti DL, Alsheik N, Bowles EJA, Tosteson ANA et al (2021) Changes in mammography use by women’s characteristics during the first 5 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Natl Cancer Inst 113(9):1161–1167

Haribhai S, Bhatia K, Shahmanesh M (2023) Global elective breast- and colorectal cancer surgery performance backlogs, attributable mortality and implemented health system responses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. PLOS Glob Public Health 3(4):e0001413

Rahman MM, Rosenberg M, Flores G, Parsell N, Akter S, Alam MA et al (2022) A systematic review and meta-analysis of unmet needs for healthcare and long-term care among older people. Heal Econ Rev 12(1):60

Article Google Scholar

Carr W, Wolfe S (1976) Unmet needs as sociomedical indicators. Int J Health Serv 6(3):417–430

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ (2009) What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 17(8):1117–1128

Miroševič Š, Prins J, Borštnar S, Besić N, Homar V, Selič-Zupančič P et al (2022) Factors associated with a high level of unmet needs and their prevalence in the breast cancer survivors 1–5 years after post local treatment and (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy during the COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol 13:969918

Kenis I, Theys S, Hermie E, Foulon V, Van Hecke A (2022) Impact of COVID-19 on the Organization of Cancer Care in Belgium: lessons learned for the (post-)pandemic future. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(19):12456

Ahmed F, Ne Ahmed, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J (2020) Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 5(5):e240

Mamelund S-E, Shelley-Egan C, Rogeberg O (2021) The association between socioeconomic status and pandemic influenza: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 16(9):e0244346

McCarthy G, Shore S, Ozdenerol E, Stewart A, Shaban-Nejad A, Schwartz DL (2023) History repeating-how pandemics collide with health disparities in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 10(3):1455–1465

Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 74(11):964–968

PubMed Google Scholar

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357

Myers C, Bennett K, Kelly C, Walshe J, O’Sullivan N, Quinn M et al (2023) Impact of COVID-19 on health care and quality of life in women with breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr 7(3)

Myers CL, Waldron C, Bennett K, Cahir C (2022) COVID-19 and breast cancer care in Ireland: a qualitative study to explore the perspective of breast cancer patients on their health and health care. Cancer Res 82(12)

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2019) Ireland: country health profile 2019. State of health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European observatory on health systems and policies. Brussels

McDaid D, Wiley M, Maresso A, Mossialos E (2009) Ireland: health system review. Health Syst Trans (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies) 11(4)

The Health Insurance Authority (2022) Health insurance in Ireland: market report 2022

Dodgson JE (2019) Reflexivity in qualitative research. J Hum Lact 35(2):220–222

Braun V, Clarke V (2022) Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol 9(1):3

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E (2006) Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 5(1):80–92

Legge H, Toohey K, Kavanagh PS, Paterson C (2022) The unmet supportive care needs of people affected by cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. J Cancer Survivorship 17(4):1036–1056

DeGuzman P, Colliton K, Nail CJ, Keim-Malpass J (2017) Survivorship care plans: rural, low-income breast cancer survivor perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs 21(6):692–698

Roux A, Cholerton R, Sicsic J, Moumjid N, French DP, Giorgi Rossi P et al (2022) Study protocol comparing the ethical, psychological and socio-economic impact of personalised breast cancer screening to that of standard screening in the “My Personal Breast Screening” (MyPeBS) randomised clinical trial. BMC Cancer 22(1):507

Kerr H, Donovan M, McSorley O (2021) Evaluation of the role of the clinical nurse specialist in cancer care: an integrative literature review. Eur J Cancer Care 30(3):e13415

McIllmurray MB, Thomas C, Francis B, Morris S, Soothill K, Al-Hamad A (2001) The psychosocial needs of cancer patients: findings from an observational study. Eur J Cancer Care 10(4):261–269

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kong YC, Wong LP, Ng CW, Taib NA, Bhoo-Pathy NT, Yusof MM et al (2020) Understanding the financial needs following diagnosis of breast cancer in a setting with universal health coverage. Oncologist 25(6):497–504

Dickerson JC, Ragavan MV, Parikh DA, Patel MI (2020) Healthcare delivery interventions to reduce cancer disparities worldwide. World J Clin Oncol 11(9):705–722

McGrowder DA, Miller FG, Vaz K, Anderson Cross M, Anderson-Jackson L, Bryan S et al (2021) The utilization and benefits of telehealth services by health care professionals managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 9(10):1401

Hale T, Angrist N, Kira B, Petherick A, Phillips T, Webster S (2020) Variation in government responses to COVID-19. University of Oxford

Burke S, Pentony S (2011) Eliminating health inequalities: a matter of life and death. TASC: think-tank for action on social change

National Cancer Strategy 2017–2026 (2017) Department of Health, and National Patient Safety (NPS) Office: Ireland

Download references

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium This work is independent research funded by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (Strategic Academic Recruitment funding).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Population Health, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, 123 St Stephen’s, Green, Dublin, D02 YN77, Ireland

Charlotte Myers

Data Science Centre, School of Population Health, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin, Ireland

Kathleen Bennett & Caitriona Cahir

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

C.M., K.B., and C.C. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by C.M. The first draft of the manuscript was written by C.M. and K.B. and C.C. commented and edited versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Charlotte Myers .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained from the Office for National Research Ethics Committee in Ireland (20-NREC-COV-078). Participation was voluntary, and participants were able to withdraw their consent at any point throughout the research study.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 26 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Myers, C., Bennett, K. & Cahir, C. Lessons learned from COVID-19: improving breast cancer care post-pandemic from the patient perspective. Support Care Cancer 32 , 338 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08540-0

Download citation

Received : 27 October 2023

Accepted : 01 May 2024

Published : 10 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08540-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breast cancer

- Social determinants of health

- Quality of life

- Patient voice

- Health policy

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Around the Practice

- Between the Lines

- Contemporary Concepts

- Readout 360

- Insights from Experts at Mayo Clinic on Translating Evidence to Clinical Practice

- Optimizing Outcomes in Patients with HER2+ Metastatic Breast Cancer

- Conferences

- Publications

- Career Center

Patient Case: A 37-Year-Old Woman With HER2+/HR- Breast Cancer

- Vijayakrishna K. Gadi, MD, PhD

- Sara A. Hurvitz, MD

Adam Brufsky, MD, PhD, presents the case of a 37-year-old woman with HER2+/HR- metastatic breast cancer and polls the audience about screening for brain metastases.

EP: 1 . Patient Case: A 37-Year-Old Woman With HER2+/HR- Breast Cancer

EP: 2 . Management Approaches for Patients with HER2+ BC at Risk for Brain Metastases

EP: 3 . The Role of Prophylactic Therapy in HER2+ BC

Ep: 4 . decision making in selecting treatment in her2+ bc, ep: 5 . her2+ bc: considerations for sequencing treatment, ep: 6 . screening and recognition of ild in her2+ bc, ep: 7 . monitoring symptoms of ild in her2+ breast cancer, ep: 8 . management of ild in her2+ bc, ep: 9 . the evolving space of her2+ breast cancer.

EP: 10 . HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: Special Challenges and Expert Insight

Adam Brufsky, MD, PhD: Welcome to this CancerNetwork ® Around the Practice presentation, “HER2+ Breast Cancer Special Challenges and Expert Insight.” I am your host, Dr Adam Brufsky, from UPMC [University of Pittsburgh Medical Center] Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Tonight we have a great panel of very enthusiastic investigators, all of whom are very experienced in this field and have lots to add to this discussion. We have Dr VK Gadi from University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago; Dr Sara Hurvitz from UCLA [University of California, Los Angeles] Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles, California; and finally, Dr Neil Iyengar from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Tonight, we’re going to talk about 3 challenges we face in our practices. The first is how to optimally treat patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and brain metastases. We’ll also discuss considerations for sequencing therapies and how we make sequencing decisions in second-, third-, and fourth-line HER2+ metastatic breast cancer. I’ll add parenthetically that it’s a comment on how far this field has come that we’re now debating third-, fourth-, and fifth-line therapy in HER2+ metastatic disease. Finally, we’ll talk about the identification and management of interstitial lung disease and how it impacts the next steps for therapy. During this time, we’ll review a single patient case. Instead of 3 cases, we’re going to do 1 case and add to it as we go along during this hour. We’re going to ask the audience several polling questions using an interactive polling platform.

Let’s start. We’d appreciate if people answer this question. How often do you screen asymptomatic patients with metastatic HER2+ breast cancer for brain metastases? Always, sometimes, rarely, or never?

The results show 20% are always screening, 60% sometimes, 20% rarely, and 0% never.

How often do you treat prophylactically for brain metastases in asymptomatic patients with HER2+ breast cancer? Always, sometimes, rarely, or never? Please fill out the poll.

This is interesting stuff. No one chose always, 25% do sometimes, 25% do rarely, and 2 votes for never. Interesting. Let’s move on and talk about a case. I’ll fill in the details of this case. It is hard to put it all in 1 or 2 slides. This is a 37-year-old woman who 3 or 4 years ago presented with a 5-cm lump in her right breast. She has the typical HER2+, IHC [immunohistochemistry] score of 3+, hormone receptor-negative breast cancer, and no other metastatic disease or LVF [left ventricular failure], and she feels well otherwise. We gave her neoadjuvant TCHP [docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, pertuzumab] for 6 cycles, and she did pretty well with it. Then she had a lumpectomy after being on radiation, had a pCR [pathologic complete response], and then was given trastuzumab and pertuzumab for the remainder of her therapy, which we can debate back and forth.

She did well for about 2.5 years and then came to the clinic complaining of increased fatigue and persistent cough. She had a chest CT scan that showed a 1.5-cm nodule in the left upper—not superior—lobe. She got a lung biopsy, which showed she has adenocarcinoma persistent with the breast primary that is IHC 3+ for HER2 and negative for ER [estrogen receptor] and PR [progesterone receptor]. She had a PET [positron emission tomography]/CT scan that showed no other bone or liver metastases, but did show several lung metastases, not just 1. Had she just had 1, we would have probably taken it out and called it a day. That’s a whole other question. She had 3 or 4 lung metastases, each of which is about 2 to 3 cm.

At this point, she was given a typical first-line regimen. She was given THP [docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab], and started on bisphosphonates every 3 months. She was given the docetaxel for probably 8 cycles and then complained of neuropathy. At that point, we discontinued that and just continued her on HP [trastuzumab, pertuzumab]. But it’s now 2 years later and a routine CT showed 3 liver metastases, each of which is about 1 or 2 cm in diameter. There is 1 that’s about 3 cm. She has 4 liver metastases, none of which are incredibly damaging to her organs, but she does clearly have visceral disease progression in her liver after THP [docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab] in the first line.

Here is the first polling question for the audience. You have a woman who has been on THP [docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab] for 2 years for metastatic disease. Would you screen her for brain metastases at that point? Obviously, she has had PET/CT, but would you actually screen an asymptomatic patient for brain metastases?

Let’s see what we’ve got. Fifty-fifty, right down the middle. This is going to be an interesting discussion with our esteemed audience and our esteemed group of investigators to see what they think.

If you did not know whether she had brain metastases, and you decide not to screen her, what would you give this patient in the absence of an MRI? She has progressive disease in her liver. She has been on HP [trastuzumab, pertuzumab] alone for about 18 months. Would you rechallenge her with THP [docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab], give her T-DM1 [trastuzumab emtansine], give her trastuzumab deruxtecan, or something else? The results show that 14% would rechallenge with THP [docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab], which is not a bad idea, 57% would give T-DM1 [trastuzumab emtansine], 29% would give trastuzumab deruxtecan, and 0% would give other.

Transcript edited for clarity.

52 UK Experience of Non-Radioisotope, Non-Magnetic Guided Breast Wide Local Excision and Sentinel Node Biopsy

Managing CDK4/6 Inhibitor, ADC Toxicity in Metastatic Breast Cancer

Sarah Donahue, MPH, NP, speaks to the importance of communicating potential adverse effects associated with treatments such as CDK4/6 inhibitors to patients with breast cancer.

Dato-DXd Shows Improved Tolerability Vs Chemo in HR+/HER2– Breast Cancer

Safety data further support datopotamab deruxtecan as a new treatment option in metastatic hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

HER2CLIMB-02 Trial Shows ‘Interesting Data’ in HER2+ Breast Cancer

Tucatinib plus trastuzumab emtansine shows a progression-free survival improvement in HER2-positive breast cancer in the phase 3 HER2CLIMB-02 trial, says Sara A. Hurvitz, MD, FACP.

55 Language as a Barrier to Deep Inspiration Breath Hold (DIBH) Radiation Therapy for Left Breast Cancer

56 Predictive Factors Correlating With Pathologic Complete Response Rates in Racially Diverse, Minority Populations Receiving Neoadjuvant Therapy for HR+/HER2– Breast Cancer

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

Personalized circulating tumor DNA response to local radiotherapy in a patient with an early lobular breast cancer: A case report

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Medicine and Oncology, Lady Davis Institute and Segal Cancer Centre, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University Montreal, Montreal, QC H3T 1E2, Canada.

- 2 Division of Oncology, Lady Davis Institute and Segal Cancer Centre, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University Montreal, Montreal, QC H3T 1E2, Canada.

- PMID: 38736743

- PMCID: PMC11082640

- DOI: 10.3892/ol.2024.14415

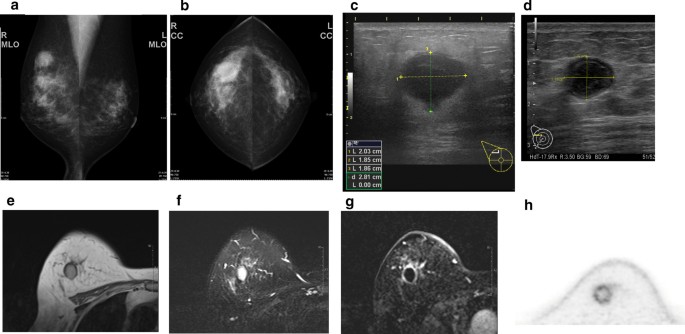

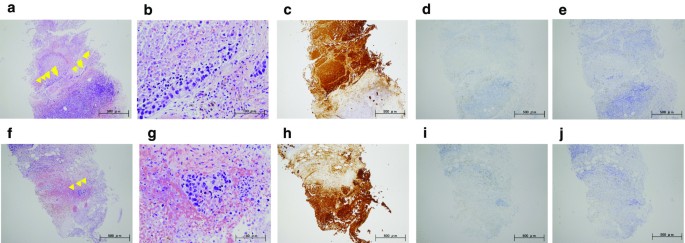

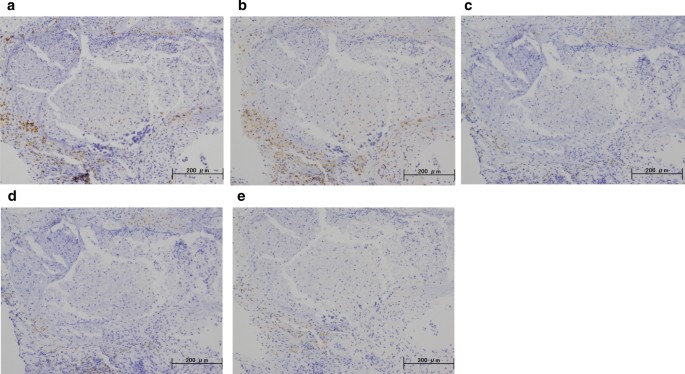

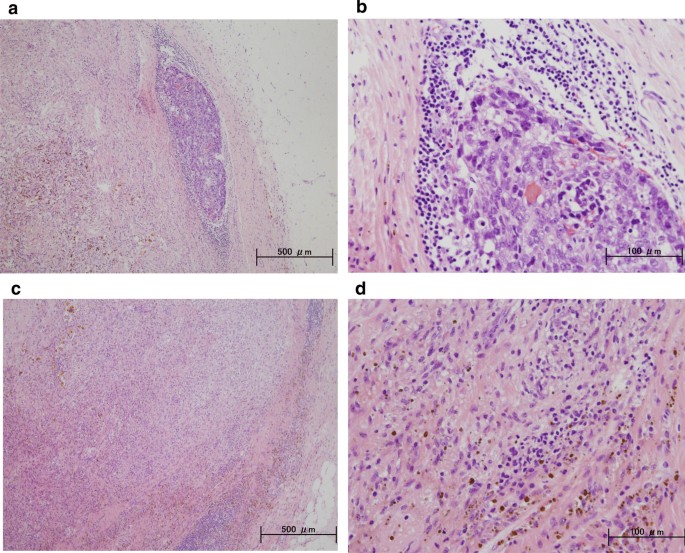

The detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the plasma of cancer patients is emerging as a very sensitive and specific prognostic biomarker. Previous studies with ctDNA have focused on the ability of ctDNA detection to predict micrometastatic and eventual clinical metastatic relapse. There are few data on the role of ctDNA in monitoring response to local therapy. The present study reports the case of a patient with early-stage lobular breast cancer, with a detectable ctDNA test which resolved with local radiotherapy to the breast. This case suggests that ctDNA is sensitive enough to detect the response of minimal residual disease, localized in the breast, to radiation therapy, and thus may assist in providing indications for local breast cancer treatment.

Keywords: biomarker; ctDNA; lobular breast cancer; radiotherapy prognostic.

Copyright © 2024, Spandidos Publications.

Publication types

- Case Reports

Grants and funding

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department Hospital Universitario Central of Asturias, Oviedo, Spain

Roles Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Ourense, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Laura Ciria-Suarez,

- Paula Jiménez-Fonseca,

- María Palacín-Lois,

- Mónica Antoñanzas-Basa,

- Ana Fernández-Montes,

- Aranzazu Manzano-Fernández,

- Beatriz Castelo,

- Elena Asensio-Martínez,

- Susana Hernando-Polo,

- Caterina Calderon

- Published: September 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680

- Reader Comments

Registered Report Protocol

21 Dec 2020: Ciria-Suarez L, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Palacín-Lois M, Antoñanzas-Basa M, Férnández-Montes A, et al. (2020) Ascertaining breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study protocol. PLOS ONE 15(12): e0244355. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244355 View registered report protocol

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases in women. Prevention and treatments have lowered mortality; nevertheless, the impact of the diagnosis and treatment continue to impact all aspects of patients’ lives (physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual).

This study seeks to explore the experiences of the different stages women with breast cancer go through by means of a patient journey.

This is a qualitative study in which 21 women with breast cancer or survivors were interviewed. Participants were recruited at 9 large hospitals in Spain and intentional sampling methods were applied. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview that was elaborated with the help of medical oncologists, nurses, and psycho-oncologists. Data were processed by adopting a thematic analysis approach.

The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer entails a radical change in patients’ day-to-day that linger in the mid-term. Seven stages have been defined that correspond to the different medical processes: diagnosis/unmasking stage, surgery/cleaning out, chemotherapy/loss of identity, radiotherapy/transition to normality, follow-up care/the “new” day-to-day, relapse/starting over, and metastatic/time-limited chronic breast cancer. The most relevant aspects of each are highlighted, as are the various cross-sectional aspects that manifest throughout the entire patient journey.

Conclusions

Comprehending patients’ experiences in depth facilitates the detection of situations of risk and helps to identify key moments when more precise information should be offered. Similarly, preparing the women for the process they must confront and for the sequelae of medical treatments would contribute to decreasing their uncertainty and concern, and to improving their quality-of-life.

Citation: Ciria-Suarez L, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Palacín-Lois M, Antoñanzas-Basa M, Fernández-Montes A, Manzano-Fernández A, et al. (2021) Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 16(9): e0257680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680

Editor: Erin J. A. Bowles, Kaiser Permanente Washington, UNITED STATES

Received: February 17, 2021; Accepted: September 3, 2021; Published: September 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Ciria-Suarez et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Relevant anonymized data excerpts from the transcripts are in the main body of the manuscript. They are supported by the supplementary documentation at 10.1371/journal.pone.0244355 .

Funding: This work was funded by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) in 2018. The sponsor of this research has not participated in the design of research, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the one that associates the highest mortality rates among Spanish women, with 32,953 new cases estimated to be diagnosed in Spain in 2020 [ 1 ]. Thanks to early diagnosis and therapeutic advances, survival has increased in recent years [ 2 ]. The 5-year survival rate is currently around 85% [ 3 , 4 ].

Though high, this survival rate is achieved at the expense of multiple treatment modalities, such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy, the side effects and sequelae of which can interfere with quality-of-life [ 5 ]. Added to this is the uncertainty surrounding prognosis; likewise, life or existential crises are not uncommon, requiring great effort to adjust and adapt [ 6 ]. This will not only affect the patient psychologically, but will also impact their ability to tolerate treatment and their socio-affective relations [ 7 ].

Several medical tests are performed (ultrasound, mammography, biopsy, CT, etc.) to determine tumor characteristics and extension, and establish prognosis [ 8 ]. Once diagnosed, numerous treatment options exist. Surgery is the treatment of choice for non-advanced breast cancer; chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy are adjuvant treatments with consolidated benefit in diminishing the risk of relapse and improving long-term survival [ 9 ]. Breast cancer treatments prompt changes in a person’s physical appearance, sexuality, and fertility that interfere with their identity, attractiveness, self-esteem, social relationships, and sexual functioning [ 10 ]. Patients also report more fatigue and sleep disturbances [ 11 ]. Treatment side effects, together with prognostic uncertainty cause the woman to suffer negative experiences, such as stress in significant relationships, and emotions, like anxiety, sadness, guilt, and/or fear of death with negative consequences on breast cancer patients’ quality-of-life [ 10 , 12 ]. Once treatment is completed, patients need time to recover their activity, as they report decreased bodily and mental function [ 13 ], fear of relapse [ 14 ], and changes in employment status [ 15 ]. After a time, there is a risk of recurrence influenced by prognostic factors, such as nodal involvement, size, histological grade, hormone receptor status, and treatment of the primary tumor [ 16 ]. Thirty percent (30%) of patients with early breast cancer eventually go on to develop metastases [ 17 ]. There is currently no curative treatment for patients with metastatic breast cancer; consequently, the main objectives are to prolong survival, enhance or maintain quality-of-life, and control symptoms [ 17 , 18 ]. In metastatic stages, women and their families are not only living with uncertainty about the future, the threat of death, and burden of treatment, but also dealing with the existential, social, emotional, and psychological difficulties their situation entails [ 18 , 19 ].

Supporting and accompanying breast cancer patients throughout this process requires a deep understanding of their experiences. To describe the patient’s experiences, including thoughts, emotions, feelings, worries, and concerns, the phrase “patient voice” has been used, which is becoming increasingly common in healthcare [ 20 ]. Insight into this “voice” allows us to delve deeper into the physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual effects of the patient’s life. This narrative can be portrayed as a “cancer journey", an experiential map of patients’ passage through the different stages of the disease [ 21 ] that captures the path from prevention to early diagnosis, acute care, remission, rehabilitation, possible recurrence, and terminal stages when the disease is incurable and progresses [ 22 ]. The term ‘patient journey’ has been used extensively in the literature [ 23 – 25 ] and is often synonymous with ‘patient pathway’ [ 26 ]. Richter et al. [ 26 ] state that there is no common definition, albeit in some instances the ‘patient journey’ comprises the core concept of the care pathway with greater focus on the individual and their perspective (needs and preferences) and including mechanisms of engagement and empowerment.

While the patient’s role in the course of the disease and in medical decision making is gaining interest, little research has focused on patient experiences [ 27 , 28 ]. Patient-centered care is an essential component of quality care that seeks to improve responsiveness to patients’ needs, values, and predilections and to enhance psychosocial outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, unmet support needs, and quality of life [ 29 ]. Qualitative studies are becoming more and more germane to grasp specific aspects of breast cancer, such as communication [ 27 , 30 ], body image and sexuality [ 31 , 32 ], motherhood [ 33 ], social support [ 34 ], survivors’ reintegration into daily life [ 13 , 15 ], or care for women with incurable, progressive cancer [ 17 ]. Nevertheless, few published studies address the experience of women with breast cancer from diagnosis to follow-up. These include a clinical pathway approach in the United Kingdom in the early 21st century [ 35 ], a breast cancer patient journey in Singapore [ 25 ], a netnography of breast cancer patients in a French specialized forum [ 28 ], a meta-synthesis of Australian women living with breast cancer [ 36 ], and a systematic review blending qualitative studies of the narratives of breast cancer patients from 30 countries [ 37 ]. Sanson-Fisher et al. [ 29 ] concluded that previously published studies had examined limited segments of patients’ experiences of cancer care and emphasized the importance of focusing more on their experiences across multiple components and throughout the continuum of care. Therefore, the aim of this study is to depict the experiences of Spanish breast cancer patients in their journey through all stages of the disease. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that examine the experience of women with breast cancer in Spain from diagnosis through treatment to follow-up of survivors and those who suffer a relapse or incurable disease presented as a journey map.

A map of the breast cancer patient’s journey will enable healthcare professionals to learn first-hand about their patients’ personal experiences and needs at each stage of the disease, improve communication and doctor-patient rapport, thereby creating a better, more person-centered environment. Importantly, understanding the transitional phases and having a holistic perspective will allow for a more holistic view of the person. Furthermore, information about the journey can aid in shifting the focus of health care toward those activities most valued by the patient [ 38 ]. This is a valuable and efficient contribution to the relationship between the system, medical team, and patients, as well as to providing resources dedicated to the patient’s needs at any given time, thus improving their quality of life and involving them in all decisions.

Study design and data collection

We conducted a qualitative study to explore the pathway of standard care for women with breast cancer and to develop a schematic map of their journey based on their experiences. A detailed description of the methodology is reported in the published protocol “Ascertaining breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study protocol” [ 39 ].

An interview guide was created based on breast cancer literature and adapted with the collaboration of two medical oncologists, three nurses (an oncology nurse from the day hospital, a case manager nurse who liaises with the different services and is the ‘named’ point of contact for breast cancer patients for their journey throughout their treatment, and a nurse in charge of explaining postoperative care and treatment), and two psycho-oncologists. The interview covered four main areas. First, sociodemographic and medical information. Second, daily activities, family, and support network. Third, participants were asked about their overall perception of breast cancer and their coping mechanisms. Finally, physical, emotional, cognitive, spiritual, and medical aspects related to diagnosis, treatment, and side effects were probed. Additionally, patients were encouraged to express their thoughts should they want to expand on the subject.

The study was carried out at nine large hospitals located in six geographical areas of Spain. To evaluate the interview process, a pilot test was performed. Interviews were conducted using the interview guide by the principal investigator who had previous experience in qualitative research. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, all interviews were completed online and video recorded with the consent of the study participants for subsequent transcription. Relevant notes were taken during the interview to document key issues and observations.

Participant selection and recruitment

Inclusion criteria were being female, over 18 years of age, having a diagnosis of histologically-confirmed adenocarcinoma of the breast, and good mental status. To ascertain the reality of women with breast cancer, most of the patients recruited (80%) had been diagnosed in the past 5 years. Patients (20%) were added who had been diagnosed more than 5 years earlier, with the aim of improving the perspective and ascertaining their experience after 5 years.

Medical oncologists and nurses working at the centers helped identify patients who met the inclusion criteria. Participants went to the sites for follow-up between December 2019 and January 2021. Eligible women were informed of the study and invited to participate during an in-person visit by these healthcare professionals. Those who showed interest gave permission to share their contact information (e-mail or telephone number) with the principal investigator, who was the person who conducted all interviews. The principal investigator contacted these women, giving them a more detailed explanation of the study and clarifying any doubts they may have. If the woman agreed to participate, an appointment was made for a videoconference.

A total of 21 women agreed to participate voluntarily in this research. With the objective of accessing several experiences and bolstering the transferability of the findings, selection was controlled with respect to subjects’ stage of cancer, guaranteeing that there would be a proportional number of women with cancer in all stages, as well as with relapses.

Data analysis

The data underwent qualitative content analysis. To assure trustworthiness, analyses were based on the system put forth by Graneheim, and Lundman [ 40 ]. Interviews were transcribed and divided into different content areas; units of meaning were obtained and introduced into each content area; meaning codes were extracted and added; codes were categorized in terms of differences and similarities, and themes were created to link underlying meanings in the categories. All members of the research team (core team, two medical oncologists, three nurses and two psycho-oncologists) reviewed the data and triangulated the outcomes between two sources of data: qualitative data from the interview and non-modifiable information, such as sociodemographic (i.e., age, marital status, having children) and clinical (i.e., cancer stage and surgery type) data. Following this process, we reached saturation of the interview data by the time we had completed 21 interviews.

Ethical considerations

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of University of Barcelona (Institutional Review Board: IRB00003099) and supported by the Bioethics Group of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) 2018 grant. All participants received a written informed consent form that they signed prior to commencing with the interviews and after receiving information about the study.

Patient baseline characteristics

In total, 21 women with a mean age of 47 years (range, 34 to 61) were interviewed. Most of the study population was married (66.7%), had a college education (66.7%), and had 2 or more children (42.9%). All cancer stages were represented, up to 23.8% tumor recurrence, and most of the primary cancers had been resected (95.2%) (see Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680.t001

Description of the breast cancer patient journey

The women diagnosed with breast cancer describe the journey as a process tremendously affected by the different medical stages. Each stage has its own characteristics that condition the experiences, unleashing specific physical, emotional, cognitive, and social processes. Additionally, the patients perceive this entire process as pre-established journey they must undertake to save their life, with its protocols based on the type and stage of cancer.

“ People said to me , ‘What do you think ? ’ and I answered that there was nothing for me to think about because everything is done , I have to go on the journey and follow it and wait to see how it goes” (Patient 6)

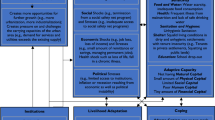

Fig 1 displays the various phases of the journey that patients with breast cancer go through; nevertheless, each woman will go through some or others, depending on their type of cancer.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680.g001

Throughout the entire patient journey.