Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

| Summarizing Conclusion | Impact of social media on adolescents’ mental health | In conclusion, our study has shown that increased usage of social media is significantly associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression among adolescents. These findings highlight the importance of understanding the complex relationship between social media and mental health to develop effective interventions and support systems for this vulnerable population. |

| Editorial Conclusion | Environmental impact of plastic waste | In light of our research findings, it is clear that we are facing a plastic pollution crisis. To mitigate this issue, we strongly recommend a comprehensive ban on single-use plastics, increased recycling initiatives, and public awareness campaigns to change consumer behavior. The responsibility falls on governments, businesses, and individuals to take immediate actions to protect our planet and future generations. |

| Externalizing Conclusion | Exploring applications of AI in healthcare | While our study has provided insights into the current applications of AI in healthcare, the field is rapidly evolving. Future research should delve deeper into the ethical, legal, and social implications of AI in healthcare, as well as the long-term outcomes of AI-driven diagnostics and treatments. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration between computer scientists, medical professionals, and policymakers is essential to harness the full potential of AI while addressing its challenges. |

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to write a high-quality conference paper, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives.

Research Skills

Results, discussion, and conclusion, results/findings.

The Results (or Findings) section follows the Methods and precedes the Discussion section. This is where the authors provide the data collected during their study. That data can sometimes be difficult to understand because it is often quite technical. Do not let this intimidate you; you will discover the significance of the results next.

The Discussion section follows the Results and precedes the Conclusions and Recommendations section. It is here that the authors indicate the significance of their results. They answer the question, “Why did we get the results we did?” This section provides logical explanations for the results from the study. Those explanations are often reached by comparing and contrasting the results to prior studies’ findings, so citations to the studies discussed in the Literature Review generally reappear here. This section also usually discusses the limitations of the study and speculates on what the results say about the problem(s) identified in the research question(s). This section is very important because it is finally moving towards an argument. Since the researchers interpret their results according to theoretical underpinnings in this section, there is more room for difference of opinion. The way the authors interpret their results may be quite different from the way you would interpret them or the way another researcher would interpret them.

Note: Some articles collapse the Discussion and Conclusion sections together under a single heading (usually “Conclusion”). If you don’t see a separate Discussion section, don’t worry. Instead, look in the nearby sections for the types of information described in the paragraph above.

When you first skim an article, it may be useful to go straight to the Conclusion and see if you can figure out what the thesis is since it is usually in this final section. The research gap identified in the introduction indicates what the researchers wanted to look at; what did they claim, ultimately, when they completed their research? What did it show them—and what are they showing us—about the topic? Did they get the results they expected? Why or why not? The thesis is not a sweeping proclamation; rather, it is likely a very reasonable and conditional claim.

Nearly every research article ends by inviting other scholars to continue the work by saying that more research needs to be done on the matter. However, do not mistake this directive for the thesis; it’s a convention. Often, the authors provide specific details about future possible studies that could or should be conducted in order to make more sense of their own study’s conclusions.

- Parts of An Article. Authored by : Kerry Bowers. Provided by : University of Mississippi. Project : WRIT 250 Committee OER Project. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Guide to Writing the Results and Discussion Sections of a Scientific Article

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing ( Bordage, 2001 ). In addition, a research paper must be clear, concise, and effective when presenting the information in an organized structure with a logical manner ( Sandercock, 2013 ).

In this article, we will take a closer look at the results and discussion section. Composing each of these carefully with sufficient data and well-constructed arguments can help improve your paper overall.

The results section of your research paper contains a description about the main findings of your research, whereas the discussion section interprets the results for readers and provides the significance of the findings. The discussion should not repeat the results.

Let’s dive in a little deeper about how to properly, and clearly organize each part.

How to Organize the Results Section

Since your results follow your methods, you’ll want to provide information about what you discovered from the methods you used, such as your research data. In other words, what were the outcomes of the methods you used?

You may also include information about the measurement of your data, variables, treatments, and statistical analyses.

To start, organize your research data based on how important those are in relation to your research questions. This section should focus on showing major results that support or reject your research hypothesis. Include your least important data as supplemental materials when submitting to the journal.

The next step is to prioritize your research data based on importance – focusing heavily on the information that directly relates to your research questions using the subheadings.

The organization of the subheadings for the results section usually mirrors the methods section. It should follow a logical and chronological order.

Subheading organization

Subheadings within your results section are primarily going to detail major findings within each important experiment. And the first paragraph of your results section should be dedicated to your main findings (findings that answer your overall research question and lead to your conclusion) (Hofmann, 2013).

In the book “Writing in the Biological Sciences,” author Angelika Hofmann recommends you structure your results subsection paragraphs as follows:

- Experimental purpose

- Interpretation

Each subheading may contain a combination of ( Bahadoran, 2019 ; Hofmann, 2013, pg. 62-63):

- Text: to explain about the research data

- Figures: to display the research data and to show trends or relationships, for examples using graphs or gel pictures.

- Tables: to represent a large data and exact value

Decide on the best way to present your data — in the form of text, figures or tables (Hofmann, 2013).

Data or Results?

Sometimes we get confused about how to differentiate between data and results . Data are information (facts or numbers) that you collected from your research ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

Whereas, results are the texts presenting the meaning of your research data ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

One mistake that some authors often make is to use text to direct the reader to find a specific table or figure without further explanation. This can confuse readers when they interpret data completely different from what the authors had in mind. So, you should briefly explain your data to make your information clear for the readers.

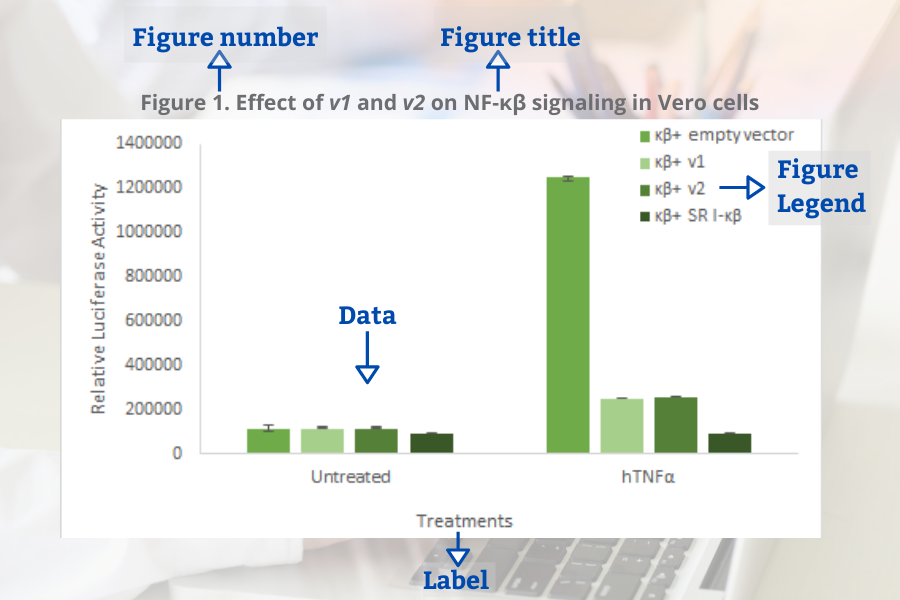

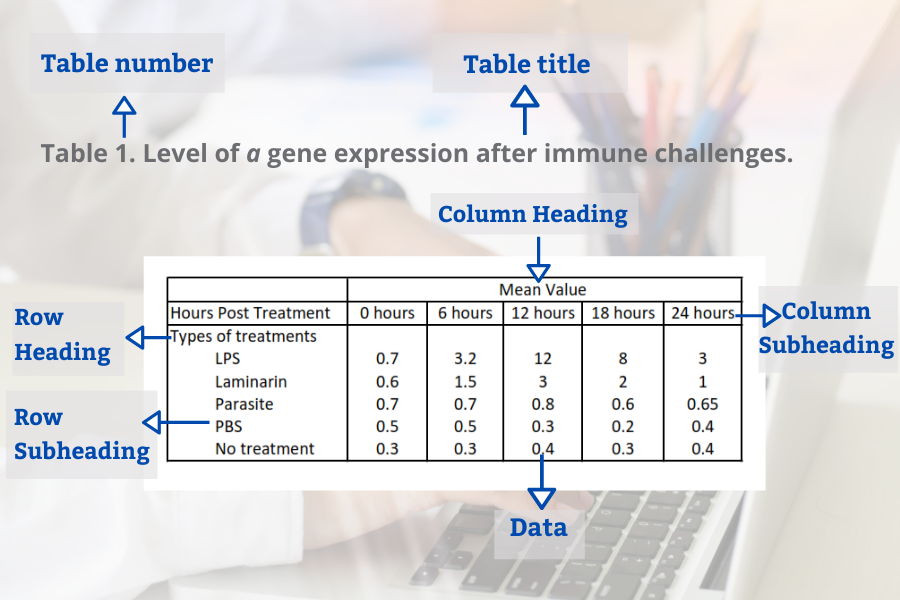

Common Elements in Figures and Tables

Figures and tables present information about your research data visually. The use of these visual elements is necessary so readers can summarize, compare, and interpret large data at a glance. You can use graphs or figures to compare groups or patterns. Whereas, tables are ideal to present large quantities of data and exact values.

Several components are needed to create your figures and tables. These elements are important to sort your data based on groups (or treatments). It will be easier for the readers to see the similarities and differences among the groups.

When presenting your research data in the form of figures and tables, organize your data based on the steps of the research leading you into a conclusion.

Common elements of the figures (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Figure number

- Figure title

- Figure legend (for example a brief title, experimental/statistical information, or definition of symbols).

Tables in the result section may contain several elements (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Table number

- Table title

- Row headings (for example groups)

- Column headings

- Row subheadings (for example categories or groups)

- Column subheadings (for example categories or variables)

- Footnotes (for example statistical analyses)

Tips to Write the Results Section

- Direct the reader to the research data and explain the meaning of the data.

- Avoid using a repetitive sentence structure to explain a new set of data.

- Write and highlight important findings in your results.

- Use the same order as the subheadings of the methods section.

- Match the results with the research questions from the introduction. Your results should answer your research questions.

- Be sure to mention the figures and tables in the body of your text.

- Make sure there is no mismatch between the table number or the figure number in text and in figure/tables.

- Only present data that support the significance of your study. You can provide additional data in tables and figures as supplementary material.

How to Organize the Discussion Section

It’s not enough to use figures and tables in your results section to convince your readers about the importance of your findings. You need to support your results section by providing more explanation in the discussion section about what you found.

In the discussion section, based on your findings, you defend the answers to your research questions and create arguments to support your conclusions.

Below is a list of questions to guide you when organizing the structure of your discussion section ( Viera et al ., 2018 ):

- What experiments did you conduct and what were the results?

- What do the results mean?

- What were the important results from your study?

- How did the results answer your research questions?

- Did your results support your hypothesis or reject your hypothesis?

- What are the variables or factors that might affect your results?

- What were the strengths and limitations of your study?

- What other published works support your findings?

- What other published works contradict your findings?

- What possible factors might cause your findings different from other findings?

- What is the significance of your research?

- What are new research questions to explore based on your findings?

Organizing the Discussion Section

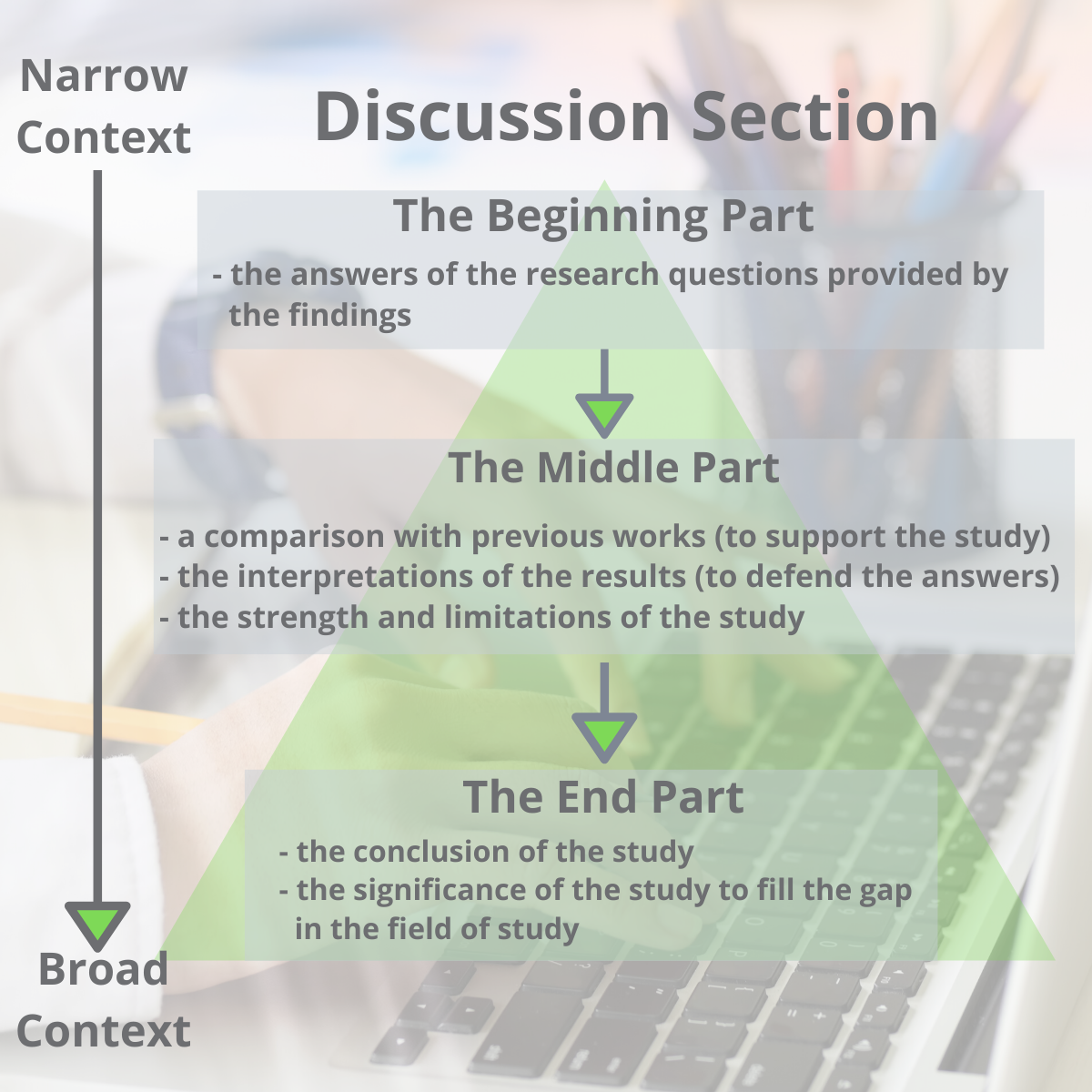

The structure of the discussion section may be different from one paper to another, but it commonly has a beginning, middle-, and end- to the section.

One way to organize the structure of the discussion section is by dividing it into three parts (Ghasemi, 2019):

- The beginning: The first sentence of the first paragraph should state the importance and the new findings of your research. The first paragraph may also include answers to your research questions mentioned in your introduction section.

- The middle: The middle should contain the interpretations of the results to defend your answers, the strength of the study, the limitations of the study, and an update literature review that validates your findings.

- The end: The end concludes the study and the significance of your research.

Another possible way to organize the discussion section was proposed by Michael Docherty in British Medical Journal: is by using this structure ( Docherty, 1999 ):

- Discussion of important findings

- Comparison of your results with other published works

- Include the strengths and limitations of the study

- Conclusion and possible implications of your study, including the significance of your study – address why and how is it meaningful

- Future research questions based on your findings

Finally, a last option is structuring your discussion this way (Hofmann, 2013, pg. 104):

- First Paragraph: Provide an interpretation based on your key findings. Then support your interpretation with evidence.

- Secondary results

- Limitations

- Unexpected findings

- Comparisons to previous publications

- Last Paragraph: The last paragraph should provide a summarization (conclusion) along with detailing the significance, implications and potential next steps.

Remember, at the heart of the discussion section is presenting an interpretation of your major findings.

Tips to Write the Discussion Section

- Highlight the significance of your findings

- Mention how the study will fill a gap in knowledge.

- Indicate the implication of your research.

- Avoid generalizing, misinterpreting your results, drawing a conclusion with no supportive findings from your results.

Aggarwal, R., & Sahni, P. (2018). The Results Section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 21-38): Springer.

Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Zadeh-Vakili, A., Hosseinpanah, F., & Ghasemi, A. (2019). The principles of biomedical scientific writing: Results. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(2).

Bordage, G. (2001). Reasons reviewers reject and accept manuscripts: the strengths and weaknesses in medical education reports. Academic medicine, 76(9), 889-896.

Cals, J. W., & Kotz, D. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part VI: discussion. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(10), 1064.

Docherty, M., & Smith, R. (1999). The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers: Much the same as that for structuring abstracts. In: British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

Faber, J. (2017). Writing scientific manuscripts: most common mistakes. Dental press journal of orthodontics, 22(5), 113-117.

Fletcher, R. H., & Fletcher, S. W. (2018). The discussion section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 39-48): Springer.

Ghasemi, A., Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Hosseinpanah, F., Shiva, N., & Zadeh-Vakili, A. (2019). The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Discussion. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(3).

Hofmann, A. H. (2013). Writing in the biological sciences: a comprehensive resource for scientific communication . New York: Oxford University Press.

Kotz, D., & Cals, J. W. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part V: results. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(9), 945.

Mack, C. (2014). How to Write a Good Scientific Paper: Structure and Organization. Journal of Micro/ Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS, 13. doi:10.1117/1.JMM.13.4.040101

Moore, A. (2016). What's in a Discussion section? Exploiting 2‐dimensionality in the online world…. Bioessays, 38(12), 1185-1185.

Peat, J., Elliott, E., Baur, L., & Keena, V. (2013). Scientific writing: easy when you know how: John Wiley & Sons.

Sandercock, P. M. L. (2012). How to write and publish a scientific article. Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal, 45(1), 1-5.

Teo, E. K. (2016). Effective Medical Writing: The Write Way to Get Published. Singapore Medical Journal, 57(9), 523-523. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016156

Van Way III, C. W. (2007). Writing a scientific paper. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 22(6), 636-640.

Vieira, R. F., Lima, R. C. d., & Mizubuti, E. S. G. (2019). How to write the discussion section of a scientific article. Acta Scientiarum. Agronomy, 41.

Related Articles

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing (Bordage, 200...

How to Survive and Complete a Thesis or a Dissertation

Writing a thesis or a dissertation can be a challenging process for many graduate students. There ar...

12 Ways to Dramatically Improve your Research Manuscript Title and Abstract

The first thing a person doing literary research will see is a research publication title. After tha...

15 Laboratory Notebook Tips to Help with your Research Manuscript

Your lab notebook is a foundation to your research manuscript. It serves almost as a rudimentary dra...

Join our list to receive promos and articles.

- Competent Cells

- Lab Startup

- Z')" data-type="collection" title="Products A->Z" target="_self" href="/collection/products-a-to-z">Products A->Z

- GoldBio Resources

- GoldBio Sales Team

- GoldBio Distributors

- Duchefa Direct

- Sign up for Promos

- Terms & Conditions

- ISO Certification

- Agarose Resins

- Antibiotics & Selection

- Biochemical Reagents

- Bioluminescence

- Buffers & Reagents

- Cell Culture

- Cloning & Induction

- Competent Cells and Transformation

- Detergents & Membrane Agents

- DNA Amplification

- Enzymes, Inhibitors & Substrates

- Growth Factors and Cytokines

- Lab Tools & Accessories

- Plant Research and Reagents

- Protein Research & Analysis

- Protein Expression & Purification

- Reducing Agents

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Conclusion

Definition:

A research paper conclusion is the final section of a research paper that summarizes the key findings, significance, and implications of the research. It is the writer’s opportunity to synthesize the information presented in the paper, draw conclusions, and make recommendations for future research or actions.

The conclusion should provide a clear and concise summary of the research paper, reiterating the research question or problem, the main results, and the significance of the findings. It should also discuss the limitations of the study and suggest areas for further research.

Parts of Research Paper Conclusion

The parts of a research paper conclusion typically include:

Restatement of the Thesis

The conclusion should begin by restating the thesis statement from the introduction in a different way. This helps to remind the reader of the main argument or purpose of the research.

Summary of Key Findings

The conclusion should summarize the main findings of the research, highlighting the most important results and conclusions. This section should be brief and to the point.

Implications and Significance

In this section, the researcher should explain the implications and significance of the research findings. This may include discussing the potential impact on the field or industry, highlighting new insights or knowledge gained, or pointing out areas for future research.

Limitations and Recommendations

It is important to acknowledge any limitations or weaknesses of the research and to make recommendations for how these could be addressed in future studies. This shows that the researcher is aware of the potential limitations of their work and is committed to improving the quality of research in their field.

Concluding Statement

The conclusion should end with a strong concluding statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. This could be a call to action, a recommendation for further research, or a final thought on the topic.

How to Write Research Paper Conclusion

Here are some steps you can follow to write an effective research paper conclusion:

- Restate the research problem or question: Begin by restating the research problem or question that you aimed to answer in your research. This will remind the reader of the purpose of your study.

- Summarize the main points: Summarize the key findings and results of your research. This can be done by highlighting the most important aspects of your research and the evidence that supports them.

- Discuss the implications: Discuss the implications of your findings for the research area and any potential applications of your research. You should also mention any limitations of your research that may affect the interpretation of your findings.

- Provide a conclusion : Provide a concise conclusion that summarizes the main points of your paper and emphasizes the significance of your research. This should be a strong and clear statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

- Offer suggestions for future research: Lastly, offer suggestions for future research that could build on your findings and contribute to further advancements in the field.

Remember that the conclusion should be brief and to the point, while still effectively summarizing the key findings and implications of your research.

Example of Research Paper Conclusion

Here’s an example of a research paper conclusion:

Conclusion :

In conclusion, our study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students. Our findings suggest that there is a significant association between social media use and increased levels of anxiety and depression among college students. This highlights the need for increased awareness and education about the potential negative effects of social media use on mental health, particularly among college students.

Despite the limitations of our study, such as the small sample size and self-reported data, our findings have important implications for future research and practice. Future studies should aim to replicate our findings in larger, more diverse samples, and investigate the potential mechanisms underlying the association between social media use and mental health. In addition, interventions should be developed to promote healthy social media use among college students, such as mindfulness-based approaches and social media detox programs.

Overall, our study contributes to the growing body of research on the impact of social media on mental health, and highlights the importance of addressing this issue in the context of higher education. By raising awareness and promoting healthy social media use among college students, we can help to reduce the negative impact of social media on mental health and improve the well-being of young adults.

Purpose of Research Paper Conclusion

The purpose of a research paper conclusion is to provide a summary and synthesis of the key findings, significance, and implications of the research presented in the paper. The conclusion serves as the final opportunity for the writer to convey their message and leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The conclusion should restate the research problem or question, summarize the main results of the research, and explain their significance. It should also acknowledge the limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research or action.

Overall, the purpose of the conclusion is to provide a sense of closure to the research paper and to emphasize the importance of the research and its potential impact. It should leave the reader with a clear understanding of the main findings and why they matter. The conclusion serves as the writer’s opportunity to showcase their contribution to the field and to inspire further research and action.

When to Write Research Paper Conclusion

The conclusion of a research paper should be written after the body of the paper has been completed. It should not be written until the writer has thoroughly analyzed and interpreted their findings and has written a complete and cohesive discussion of the research.

Before writing the conclusion, the writer should review their research paper and consider the key points that they want to convey to the reader. They should also review the research question, hypotheses, and methodology to ensure that they have addressed all of the necessary components of the research.

Once the writer has a clear understanding of the main findings and their significance, they can begin writing the conclusion. The conclusion should be written in a clear and concise manner, and should reiterate the main points of the research while also providing insights and recommendations for future research or action.

Characteristics of Research Paper Conclusion

The characteristics of a research paper conclusion include:

- Clear and concise: The conclusion should be written in a clear and concise manner, summarizing the key findings and their significance.

- Comprehensive: The conclusion should address all of the main points of the research paper, including the research question or problem, the methodology, the main results, and their implications.

- Future-oriented : The conclusion should provide insights and recommendations for future research or action, based on the findings of the research.

- Impressive : The conclusion should leave a lasting impression on the reader, emphasizing the importance of the research and its potential impact.

- Objective : The conclusion should be based on the evidence presented in the research paper, and should avoid personal biases or opinions.

- Unique : The conclusion should be unique to the research paper and should not simply repeat information from the introduction or body of the paper.

Advantages of Research Paper Conclusion

The advantages of a research paper conclusion include:

- Summarizing the key findings : The conclusion provides a summary of the main findings of the research, making it easier for the reader to understand the key points of the study.

- Emphasizing the significance of the research: The conclusion emphasizes the importance of the research and its potential impact, making it more likely that readers will take the research seriously and consider its implications.

- Providing recommendations for future research or action : The conclusion suggests practical recommendations for future research or action, based on the findings of the study.

- Providing closure to the research paper : The conclusion provides a sense of closure to the research paper, tying together the different sections of the paper and leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

- Demonstrating the writer’s contribution to the field : The conclusion provides the writer with an opportunity to showcase their contribution to the field and to inspire further research and action.

Limitations of Research Paper Conclusion

While the conclusion of a research paper has many advantages, it also has some limitations that should be considered, including:

- I nability to address all aspects of the research: Due to the limited space available in the conclusion, it may not be possible to address all aspects of the research in detail.

- Subjectivity : While the conclusion should be objective, it may be influenced by the writer’s personal biases or opinions.

- Lack of new information: The conclusion should not introduce new information that has not been discussed in the body of the research paper.

- Lack of generalizability: The conclusions drawn from the research may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, limiting the generalizability of the study.

- Misinterpretation by the reader: The reader may misinterpret the conclusions drawn from the research, leading to a misunderstanding of the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Problem Statement – Writing Guide, Examples and...

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Figures in Research Paper – Examples and Guide

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and...

- SpringerLink shop

Discussion and Conclusions

Your Discussion and Conclusions sections should answer the question: What do your results mean?

In other words, the majority of the Discussion and Conclusions sections should be an interpretation of your results. You should:

- Discuss your conclusions in order of most to least important.

- Compare your results with those from other studies: Are they consistent? If not, discuss possible reasons for the difference.

- Mention any inconclusive results and explain them as best you can. You may suggest additional experiments needed to clarify your results.

- Briefly describe the limitations of your study to show reviewers and readers that you have considered your experiment’s weaknesses. Many researchers are hesitant to do this as they feel it highlights the weaknesses in their research to the editor and reviewer. However doing this actually makes a positive impression of your paper as it makes it clear that you have an in depth understanding of your topic and can think objectively of your research.

- Discuss what your results may mean for researchers in the same field as you, researchers in other fields, and the general public. How could your findings be applied?

- State how your results extend the findings of previous studies.

- If your findings are preliminary, suggest future studies that need to be carried out.

- At the end of your Discussion and Conclusions sections, state your main conclusions once again .

Back │ Next

- Communicating in STEM Disciplines

- Features of Academic STEM Writing

- STEM Writing Tips

- Academic Integrity in STEM

- Strategies for Writing

- Science Writing Videos – YouTube Channel

- Educator Resources

- Lesson Plans, Activities and Assignments

- Strategies for Teaching Writing

- Grading Techniques

IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion)

Academic research papers in STEM disciplines typically follow a well-defined I-M-R-A-D structure: Introduction, Methods, Results And Discussion (Wu, 2011). Although not included in the IMRAD name, these papers often include a Conclusion.

Introduction

The Introduction typically provides everything your reader needs to know in order to understand the scope and purpose of your research. This section should provide:

- Context for your research (for example, the nature and scope of your topic)

- A summary of how relevant scholars have approached your research topic to date, and a description of how your research makes a contribution to the scholarly conversation

- An argument or hypothesis that relates to the scholarly conversation

- A brief explanation of your methodological approach and a justification for this approach (in other words, a brief discussion of how you gather your data and why this is an appropriate choice for your contribution)

- The main conclusions of your paper (or the “so what”)

- A roadmap, or a brief description of how the rest of your paper proceeds

The Methods section describes exactly what you did to gather the data that you use in your paper. This should expand on the brief methodology discussion in the introduction and provide readers with enough detail to, if necessary, reproduce your experiment, design, or method for obtaining data; it should also help readers to anticipate your results. The more specific, the better! These details might include:

- An overview of the methodology at the beginning of the section

- A chronological description of what you did in the order you did it

- Descriptions of the materials used, the time taken, and the precise step-by-step process you followed

- An explanation of software used for statistical calculations (if necessary)

- Justifications for any choices or decisions made when designing your methods

Because the methods section describes what was done to gather data, there are two things to consider when writing. First, this section is usually written in the past tense (for example, we poured 250ml of distilled water into the 1000ml glass beaker). Second, this section should not be written as a set of instructions or commands but as descriptions of actions taken. This usually involves writing in the active voice (for example, we poured 250ml of distilled water into the 1000ml glass beaker), but some readers prefer the passive voice (for example, 250ml of distilled water was poured into the 1000ml beaker). It’s important to consider the audience when making this choice, so be sure to ask your instructor which they prefer.

The Results section outlines the data gathered through the methods described above and explains what the data show. This usually involves a combination of tables and/or figures and prose. In other words, the results section gives your reader context for interpreting the data. The results section usually includes:

- A presentation of the data obtained through the means described in the methods section in the form of tables and/or figures

- Statements that summarize or explain what the data show

- Highlights of the most important results

Tables should be as succinct as possible, including only vital information (often summarized) and figures should be easy to interpret and be visually engaging. When adding your written explanation to accompany these visual aids, try to refer your readers to these in such a way that they provide an additional descriptive element, rather than simply telling people to look at them. This can be especially helpful for readers who find it hard to see patterns in data.

The Discussion section explains why the results described in the previous section are meaningful in relation to previous scholarly work and the specific research question your paper explores. This section usually includes:

- Engagement with sources that are relevant to your work (you should compare and contrast your results to those of similar researchers)

- An explanation of the results that you found, and why these results are important and/or interesting

Some papers have separate Results and Discussion sections, while others combine them into one section, Results and Discussion. There are benefits to both. By presenting these as separate sections, you’re able to discuss all of your results before moving onto the implications. By presenting these as one section, you’re able to discuss specific results and move onto their significance before introducing another set of results.

The Conclusion section of a paper should include a brief summary of the main ideas or key takeaways of the paper and their implications for future research. This section usually includes:

- A brief overview of the main claims and/or key ideas put forth in the paper

- A brief discussion of potential limitations of the study (if relevant)

- Some suggestions for future research (these should be clearly related to the content of your paper)

Sample Research Article

Resource Download

Wu, Jianguo. “Improving the writing of research papers: IMRAD and beyond.” Landscape Ecology 26, no. 10 (November 2011): 1345–1349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10980-011-9674-3.

Further reading:

- Organization of a Research Paper: The IMRAD Format by P. K. Ramachandran Nair and Vimala D. Nair

- George Mason University Writing Centre’s guide on Writing a Scientific Research Report (IMRAD)

- University of Wisconsin Writing Centre’s guide on Formatting Science Reports

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach

For most research papers in the social and behavioral sciences, there are two possible ways of organizing the results . Both approaches are appropriate in how you report your findings, but use only one approach.

- Present a synopsis of the results followed by an explanation of key findings . This approach can be used to highlight important findings. For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is appropriate to highlight this finding in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a result and then explain it, before presenting the next result then explaining it, and so on, then end with an overall synopsis . This is the preferred approach if you have multiple results of equal significance. It is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it is helpful to provide a brief conclusion that ties each of the findings together and provides a narrative bridge to the discussion section of the your paper.

NOTE: Just as the literature review should be arranged under conceptual categories rather than systematically describing each source, you should also organize your findings under key themes related to addressing the research problem. This can be done under either format noted above [i.e., a thorough explanation of the key results or a sequential, thematic description and explanation of each finding].

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following:

- Introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem underpinning your study . This is useful in re-orientating the reader's focus back to the research problem after having read a review of the literature and your explanation of the methods used for gathering and analyzing information.

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate key findings, if appropriate . Rather than relying entirely on descriptive text, consider how your findings can be presented visually. This is a helpful way of condensing a lot of data into one place that can then be referred to in the text. Consider referring to appendices if there is a lot of non-textual elements.

- A systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation . Not all results that emerge from the methodology used to gather information may be related to answering the " So What? " question. Do not confuse observations with interpretations; observations in this context refers to highlighting important findings you discovered through a process of reviewing prior literature and gathering data.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported . However, focus on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem. It is not uncommon to have unanticipated results that are not relevant to answering the research question. This is not to say that you don't acknowledge tangential findings and, in fact, can be referred to as areas for further research in the conclusion of your paper. However, spending time in the results section describing tangential findings clutters your overall results section and distracts the reader.

- A short paragraph that concludes the results section by synthesizing the key findings of the study . Highlight the most important findings you want readers to remember as they transition into the discussion section. This is particularly important if, for example, there are many results to report, the findings are complicated or unanticipated, or they are impactful or actionable in some way [i.e., able to be pursued in a feasible way applied to practice].

NOTE: Always use the past tense when referring to your study's findings. Reference to findings should always be described as having already happened because the method used to gather the information has been completed.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save this for the discussion section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to the work of Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings. This should have been done in your introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need for additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Writing up research is rarely a linear process. Always revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . A negative result generally refers to a finding that does not support the underlying assumptions of your study. Do not ignore them. Document these findings and then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, can give you an opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be hesitant to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater than other variables..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...." Subjective modifiers should be explained in the discussion section of the paper [i.e., why did one variable appear greater? Or, how does the finding demonstrate a promising trend?].

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you want to highlight a particular finding, it is appropriate to do so in the results section. However, you should emphasize its significance in relation to addressing the research problem in the discussion section. Do not repeat it in your results section because you can do that in the conclusion of your paper.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. Don't call a chart an illustration or a figure a table. If you are not sure, go here .

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070; Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Caprette, David R. Writing Research Papers. Experimental Biosciences Resources. Rice University; Hancock, Dawson R. and Bob Algozzine. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Researchers . 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press, 2011; Introduction to Nursing Research: Reporting Research Findings. Nursing Research: Open Access Nursing Research and Review Articles. (January 4, 2012); Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit ; Ng, K. H. and W. C. Peh. "Writing the Results." Singapore Medical Journal 49 (2008): 967-968; Reporting Research Findings. Wilder Research, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 2009); Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Results. Thesis Writing in the Sciences. Course Syllabus. University of Florida.

Writing Tip

Why Don't I Just Combine the Results Section with the Discussion Section?

It's not unusual to find articles in scholarly social science journals where the author(s) have combined a description of the findings with a discussion about their significance and implications. You could do this. However, if you are inexperienced writing research papers, consider creating two distinct sections for each section in your paper as a way to better organize your thoughts and, by extension, your paper. Think of the results section as the place where you report what your study found; think of the discussion section as the place where you interpret the information and answer the "So What?" question. As you become more skilled writing research papers, you can consider melding the results of your study with a discussion of its implications.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Aleksandra Kasztalska. Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Insiderness

- Next: Using Non-Textual Elements >>

- Last Updated: Jun 12, 2024 8:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

What Is the Difference Between Results and Conclusions in a Scientific Experiment?

Five steps make up most scientific experiments, beginning with the research question. The next step is the formulation of a hypothesis, which is a statement of what you expect your project will show. The procedure is your step-by-step plan for the experiment. The final two steps are the results, or what happens, and, finally, the conclusion, or what the results showed.

The Results

When you record the results of a scientific experiment, you record what happens as you follow your procedure. Results should be raw data that is measurable rather than general observations, and it should relate directly to your research question and hypothesis. For example, if your experiment involves growing plants, the results will be data about one aspect of the plants’ growth, such as how much each plant grows over a particular period of time or which seed sprouts first. The results should also include notations of any variations in the conditions of the experiment, which in this case might be an unexpected overnight freeze or which seed received the most water.

Data Organization

At the end of your experiment’s procedure, you have data that tells what happened, but at this point it is just a collection of facts or numbers. The data needs to be organized before you can understand it, but how you organize the data depends on the factor tested in your experiment. If you entered the data into a chart as you collected it, you may already see a pattern. Another way to organize the data is with a line graph to show change over time, especially temperature changes. In the example of plant growth, a bar graph can illustrate how much each plant grew between measurements.

The Conclusion

After all the data is organized in a form that relates it to your hypothesis, you can interpret it and reach a conclusion about the experiment. The conclusion is simply a report about what you learned based on whether the results agree or disagree with your hypothesis. It usually contains a summary of the actual procedure and makes note of anything unexpected that happened during the experiment. Your conclusion should consider all possible explanations of the data, including any errors you might have made, such as forgetting to water the plants one day. It can also give you a point from which to create further hypotheses relating to the experiment.

No Right or Wrong

The conclusion, which is also sometimes called a discussion or interpretation, is a statement about the experiment’s results. As a report of your data, it can’t be considered wrong even if the results don’t support your hypothesis. You have learned that your hypothesis does not answer your original research question.

- Agriculture Is a Science: Parts of a Science Project

- Vermont EPSCoR Streams Project: Data Analysis Tutorial

Cynthia Gast began writing professionally over 25 years ago in the automotive magazine niche and has also taught preschoolers and elementary grades. She has been a full-time freelance writer since 2008. Gast holds a Bachelor of Arts in history from the University of Illinois.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4