A Step-by-Step Guide To Case Discussion

By ashi jain.

Join InsideIIM GOLD

Webinars & Workshops

- Compare B-Schools

- Free CAT Course

Take Free Mock Tests

Upskill With AltUni

CAT Study Planner

Are you comfortable in Decision Making in a given situation How aptly you analyze the situation with a logical approach How much time do you take in arriving at a decision How good are you in taking the rightful course of action

Solved Example:

Hari, the only working member of the family has been working an organization for 25 years. His job required long standing hours. One day, while working, he lost his leg in an accident. The company paid for his medical reimbursement.

Since he was a hardworking employee; the company offered him another compensatory job. He refused by saying, ‘Once a Lion, always a Lion’. As an HR, what solution would you suggest?

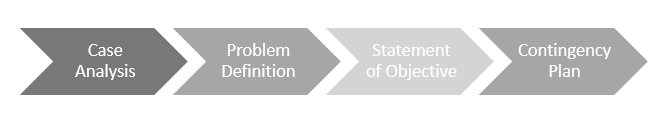

Identification of the Problem:

Obvious: accident, refusal of job, only earning member, his attitude, and inability to do his current job Hidden: the reputation of the company at stake, the course of action might influence other employees

Action Plan:

As an HR, you are first expected to check the company records and find out how a similar case has been dealt with in the past. Second, you need to take cognizance of the track record of the employee highlighted by the keyword ‘hardworking’.

Given the situation at hand, he is deemed unfit for his current role. However, the problem arises because of his attitude towards the compensatory job. Hence, in such a case, counselling is required.

Here, three levels of Counselling is required: 1. Ist level is with Hari 2. IInd level of counselling is required with the Union Leader (if any) to keep the collective interest and the reputation of the company in mind 3. IIIrd level of counselling is required with his family members as they constitute of the afflicted party

If the counselling does not work, one should also identify a contingency plan or Plan B. In this case, the Contingency Plan would be – hire someone from his family for a compensatory role.

Note that the following options are out of scope and should be avoided: 1. Increase Hari’s salary so that he gives in and agrees to do the compensatory job 2. Status Quo – do not bother as long as the Company is making a profit 3. Replace Hari with someone else

1. Pinpoint the key issues to be solved and identify their cause and effects

2. Start broad and try to work through a range of issues methodically

3. Connect the facts and evidence and focus on the big picture

4. Discuss any trade-offs or implications of your proposed solution

5. Relate your conclusion back to the problem statement and make sure you have answered all the questions

1. Do not be anxious if you are not able to understand the situation well or unable to justify the problem. Read again, a little slowly, it will help you understand better.

2. Do not jump to conclusions; try to move systematically and gradually.

3. Do not panic if you are unable to analyze the situation. Listen carefully to others as the discussion starts, it will help you gauge the problem at hand.

All the best! Ace the GDPI season.

Related Tags

FMS Delhi Summer Placements 2024: Median Stipend at 3 Lakhs

Mini Mock Test

CUET-PG Mini Mock 2 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

CUET-PG Mini Mock 3 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

CUET-PG Mini Mock 1 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

MBA Admissions 2024 - WAT 1

SNAP Quantitative Skills

SNAP Quant - 1

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 1

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 2

SNAP DILR Mini Mock - 4

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 2

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 4

SNAP LR Mini Mock - 3

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 3

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 3

SNAP - Quant Mini Mock 5

XAT Decision Making 2020

XAT Decision Making 2019

XAT Decision Making 2018

XAT Decision Making -10

XAT Decision Making -11

XAT Decision Making - 12

XAT Decision Making - 13

XAT Decision Making - 14

XAT Decision Making - 15

XAT Decision Making - 16

XAT Decision Making - 17

XAT Decision Making 2021

LR Topic Test

DI Topic Test

ParaSummary Topic Test

Take Free Test Here

Life of indian mba students in milan, italy - what’s next.

By InsideIIM Career Services

IMI Delhi: Worth It? | MBA ROI, Fees, Selection Process, Campus Life & More | KYC

How to calculate the real cost of an mba in 2024 ft. imt nagpur professors, mahindra university mba: worth it | campus life, academics, courses, placement | know your campus, how to uncover the reality of b-schools before joining, ft. masters' union, gmat focus edition: syllabus, exam pattern, scoring system, selection & more | new gmat exam, how to crack the jsw challenge 2023: insider tips and live q&a with industry leaders, why an xlri jamshedpur & fms delhi graduate decided to join the pharma industry, subscribe to our newsletter.

For a daily dose of the hottest, most insightful content created just for you! And don't worry - we won't spam you.

Who Are You?

Top B-Schools

Write a Story

InsideIIM Gold

InsideIIM.com is India's largest community of India's top talent that pursues or aspires to pursue a career in Management.

Follow Us Here

Konversations By InsideIIM

TestPrep By InsideIIM

- NMAT by GMAC

- Score Vs Percentile

- Exam Preparation

- Explainer Concepts

- Free Mock Tests

- RTI Data Analysis

- Selection Criteria

- CAT Toppers Interview

- Study Planner

- Admission Statistics

- Interview Experiences

- Explore B-Schools

- B-School Rankings

- Life In A B-School

- B-School Placements

- Certificate Programs

- Katalyst Programs

Placement Preparation

- Summer Placements Guide

- Final Placements Guide

Career Guide

- Career Explorer

- The Top 0.5% League

- Konversations Cafe

- The AltUni Career Show

- Employer Rankings

- Alumni Reports

- Salary Reports

Copyright 2024 - Kira9 Edumedia Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Triangulation in Research – Types, Methods and...

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and...

Applied Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and...

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Illinois Online

- Illinois Remote

- TA Resources

- Teaching Consultation

- Teaching Portfolio Program

- Grad Academy for College Teaching

- Faculty Events

- The Art of Teaching

- 2022 Illinois Summer Teaching Institute

- Large Classes

- Leading Discussions

- Laboratory Classes

- Lecture-Based Classes

- Planning a Class Session

- Questioning Strategies

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

- The Case Method

- Community-Based Learning: Service Learning

- Group Learning

- Just-in-Time Teaching

- Creating a Syllabus

- Motivating Students

- Dealing With Cheating

- Discouraging & Detecting Plagiarism

- Diversity & Creating an Inclusive Classroom

- Harassment & Discrimination

- Professional Conduct

- Foundations of Good Teaching

- Student Engagement

- Assessment Strategies

- Course Design

- Student Resources

- Teaching Tips

- Graduate Teacher Certificate

- Certificate in Foundations of Teaching

- Teacher Scholar Certificate

- Certificate in Technology-Enhanced Teaching

- Master Course in Online Teaching (MCOT)

- 2022 Celebration of College Teaching

- 2023 Celebration of College Teaching

- Hybrid Teaching and Learning Certificate

- 2024 Celebration of College Teaching

- Classroom Observation Etiquette

- Teaching Philosophy Statement

- Pedagogical Literature Review

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Instructor Stories

- Podcast: Teach Talk Listen Learn

- Universal Design for Learning

Sign-Up to receive Teaching and Learning news and events

Cases are narratives, situations, select data samplings, or statements that present unresolved and provocative issues, situations, or questions (Indiana University Teaching Handbook, 2005). The case method is a participatory, discussion-based way of learning where students gain skills in critical thinking, communication, and group dynamics. It is a type of problem-based learning . Often seen in the professional schools of medicine, law, and business, the case method is now used successfully in disciplines such as engineering, chemistry, education, and journalism. Students can work through a case during class as a whole or in small groups.

In addition to the definition above, the case method of teaching (or learning):

- Is a partnership between students and teacher as well as among students.

- Promotes more effective contextual learning and long-term retention.

- Involves trust that students will find the answers.

- Answers questions not only of “how” but “why.”

- Provides students the opportunity to “walk around the problem” and to see varied perspectives.

(Bruner, 2002, and Christensen, Garvin, and Sweet, 1991)

What is the value of the case method?

Bruner (1991) states that the case method:

- Is effective: It employs active learning, involves self-discovery where the teacher serves as facilitator.

- Builds the capacity for critical thinking: It uses questioning skills as modeled by the teacher and employs discussion and debates.

- Exercises an administrative point of view: Students must develop a framework for making decisions.

- Models a learning environment: It offers an exchange and flow of ideas from one person to another and achieves trust, respect, and risk-taking.

- Models the process of inductive learning-from-experience: It is valuable in promoting life-long learning. It also promotes more effective contextual learning and long-term retention.

- Mimics the real world: Decisions are sometimes based not on absolute values of right and wrong, but on relative values and uncertainty.

What are some ways to use the case method appropriately?

Choose an appropriate case

Cases can be any of the following (Indiana University Teaching Handbook, 2005):

- Finished cases based on facts; these are useful for purposes of analysis.

- Unfinished open-ended cases; where the results are not clear yet, so the student must predict, make suggestions, and conclusions.

- Fictional cases that the teacher writes; the difficulty is in writing these cases so they reflect a real-world situation.

- Original documents, such as the use of news articles, reports, data sets, ethnographies; an interesting case would be to provide two sides of a scenario.

Develop effective questions

Think about ways to start the discussion such as using a hypothetical example or employing the background knowledge of your students.

Get students prepared

To prepare for the next class ask students to think about the following questions:

- What is the problem or decision?

- Who is the key decision-maker?

- Who are the other people involved?

- What caused the problem?

- What are some underlying assumptions or objectives?

- What decision needs to be made?

- Are there alternative responses?

Set ground rules with your students

For effective class discussion suggest the following to your students:

- Carefully listen to the discussion, but do not wait too long to participate.

- Collaboration and respect should always be present.

- Provide value-added comments, suggestions, or questions. Strive to think of the class objective by keeping the discussion going toward constructive inquiry and solutions.

Other suggestions

- Try to refrain from being the “sage on the stage” or a monopolizer. If you are, students are merely absorbing and not engaging with the material in the way that the case method allows.

- Make sure the students have finished presenting their perspective before interjecting. Wait and check their body language before adding or changing the discussion.

- Take note of the progress and the content in the discussion. One way is by using the board or computer to structure the comments. Another way, particularly useful where there is a conflict or multiple alternatives, is the two-column method. In this method, the teacher makes two columns: “For and Against” or “Alternative A and Alternative B.” All arguments/comments are listed in the respective column before discussions or evaluations occur. Don't forget to note supportive evidence.

- In addition to the discussion method, you can also try debates, role-plays, and simulations as ways to uncover the lesson from the case.

- If you decide to grade participation, make sure that your grading system is an accurate and defensible portrayal of the contributions.

In conclusion, cases are a valuable way for learning to occur. It takes a fair amount of preparation by both the teacher and the students, but don't forget these benefits (Bruner, 2002):

- The teacher is learning as well as the students. Because of the interactive nature of this method, the teacher constantly “encounters fresh perspective on old problems or tests classic solutions to new problems.”

- The students are having fun, are motivated and engaged. If done well, the students are working collaboratively to support each other.

Where can I learn more?

- Case Studies, Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University

- Case-based Teaching, Center for Research on Teaching and Learning, University of Michigan

- Barnes, L. B., Christensen, C. R., & Hansen, A. J. (1994). Teaching and the case method (3rd ed.). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Boehrer, J., & Linsky, M. (1990). Teaching with cases: Learning to question. In M. D. Svinicki (Ed.), New Directions for Teaching and Learning: No. 42, The changing face of college teaching . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bruner, R. (2002). Socrates' muse: Reflections on effective case discussion leadership . New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Christensen, C. R., Garvin, D. A., & Sweet, A. (Eds.). (1991). Education for judgment: The artistry of discussion leadership . Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Indiana University, Bloomington, Campus Instructional Consulting. (n.d.). Teaching with the case method. In Indiana University Teaching Handbook . Retrieved June 23, 2010, from http://www.teaching.iub.edu/wrapper_big.php?section_id=case

- Mitchell, T., & Rosenstiel, T. (2003). Background and tips for case study teaching . Retrieved June 23, 2010, from http://www.journalism.org/node/1757

Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning

249 Armory Building 505 East Armory Avenue Champaign, IL 61820

217 333-1462

Email: [email protected]

Office of the Provost

- Utility Menu

GA4 tagging code

- Demonstrating Moves Live

- Raw Clips Library

- Facilitation Guide

Structuring the Case Discussion

Well-designed cases are intentionally complex. Therefore, presenting an entire case to students all at once has the potential to overwhelm student groups and lead them to overlook key details or analytic steps. Accordingly, Barbara Cockrill asks students to review key case concepts the night before, and then presents the case in digestible “chunks” during a CBCL session. Structuring the case discussion around key in-depth questions, Cockrill creates a thoughtful interplay between small group work and whole group discussion that makes for more systematic forays into the case at hand.

Barbara Cockrill , Harold Amos Academy Associate Professor of Medicine

Student Group

Harvard Medical School

Homeostasis I

40 students

Additional Details

First-year requisite

- Classroom Considerations

- Relevant Research

- Related Resources

- CBCL provides students the opportunity to apply course material in new ways. For this reason, you might consider not sharing the case with students beforehand and having them experience it in class with fresh eyes.

- Chunk cases so students can focus on case specifics and gradually build-up to greater complexity and understanding.

- Introduce variety into case-based discussions. Integrate a mix of independent work, small group discussion, and whole group share outs to keep students engaged and provide multiple junctures for students to get feedback on their understanding.

- Instructor scaffolding is critical for effective case-based learning ( Ramaekers et al., 2011 )

- This resource from the Harvard Business School provides suggestions for questioning, listening, and responding during a case discussion .

- This comprehensive resource on “The ABCs of Case Teaching” provides helpful tips for planning and “running” your case .

Related Moves

Experiencing the Case as a Student Team

Regulating the Flow of Energy in the Classroom

Designing Focused Discussions for Relevance and Transfer of Knowledge

Facilitating a Case Discussion

Have a plan, but be ready to adjust it.

Enter each case discussion with a plan that includes the major topics you hope to cover (with rough time estimates) and the questions you hope to ask for each topic. Be as flexible as you can about how and when the topics are covered, and allow the participants to drive the discussion.

Ask Good Questions

Strive to make your questions interesting (a good measure is your own interest in the answer), clear, and as concise as possible. Emphasize questions that require judgment and analysis rather than purely factual responses. You want as many students as possible to be engaged and interested in joining the discussion. Vary your question types and style to avoid being predictable and keep students engaged.

When calling on students, consider three strategies: an open call , where you call on volunteers; a warm call , where you provide advance notice to a student before or during class before calling on them; and a cold call , where you call on them without any prior warning and when they did not volunteer. If you choose to allow students to speak without raising their hands, be careful to monitor the impact on the distribution of who speaks when—those comfortable speaking out may not be representative of all of your students.

Listen Attentively and Monitor Airtime

If you want students to be engaged and listen to each other, you must also be sure to listen well yourself. Use what you hear to drive your follow-up questions and the next student you call on. As the facilitator, you need to balance the opportunities to speak in class as well as the amount of “airtime” each student gets. The airtime need not be equal in each class session, but track this over time to keep it in balance.

Allow Space to Adjust

Your teaching plan will include several key themes to cover. As you consider transitions, ask yourself a few key questions: Have you covered the key issues in the discussion? What remains to be covered? Is it imperative to cover that material today rather than in a subsequent class?

Incorporate Group Work

Small groups in and outside class can elevate the discussions and increase student engagement. Having teams prepare cases together gives students an opportunity to test ideas and lower the preparation burden. Within class, small groups can accelerate analysis, fill in gaps in preparation, and set up debates. Be sure to give groups clear instructions, and make use of any deliverables they create.

Embrace the Open-Ended

Most students will crave clear answers at the end of each case discussion. Be wary of sharing prefabricated slides with conclusions, and rely more on students to provide the lessons. Call on students to share their thoughts (these can be warm calls at the start of class), have small groups generate their takeaways, or leave students with a question to ponder rather than answers to write down. Vary how you wrap up each class to stay unpredictable.

The Art of Cold Calling

The Perfect Opening Question

Questions for Class Discussion

What to Do When Students Bring Case Solutions to Class

More Key Topics

Teaching Cases in Hybrid Settings

How to balance the needs of both your in-person and remote students.

Assessing Learning Outcomes in Case Classrooms

Steps to equitably and credibly grade discussion-based learning.

Selecting Cases to Use in Your Classes

Find the right materials to achieve your learning goals.

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 4. Techniques for Leading Group Discussions

Chapter 16 Sections

- Section 1. Conducting Effective Meetings

- Section 2. Developing Facilitation Skills

- Section 3. Capturing What People Say: Tips for Recording a Meeting

- Main Section

A local coalition forms a task force to address the rising HIV rate among teens in the community. A group of parents meets to wrestle with their feeling that their school district is shortchanging its students. A college class in human services approaches the topic of dealing with reluctant participants. Members of an environmental group attend a workshop on the effects of global warming. A politician convenes a “town hall meeting” of constituents to brainstorm ideas for the economic development of the region. A community health educator facilitates a smoking cessation support group.

All of these might be examples of group discussions, although they have different purposes, take place in different locations, and probably run in different ways. Group discussions are common in a democratic society, and, as a community builder, it’s more than likely that you have been and will continue to be involved in many of them. You also may be in a position to lead one, and that’s what this section is about. In this last section of a chapter on group facilitation, we’ll examine what it takes to lead a discussion group well, and how you can go about doing it.

What is an effective group discussion?

The literal definition of a group discussion is obvious: a critical conversation about a particular topic, or perhaps a range of topics, conducted in a group of a size that allows participation by all members. A group of two or three generally doesn’t need a leader to have a good discussion, but once the number reaches five or six, a leader or facilitator can often be helpful. When the group numbers eight or more, a leader or facilitator, whether formal or informal, is almost always helpful in ensuring an effective discussion.

A group discussion is a type of meeting, but it differs from the formal meetings in a number of ways: It may not have a specific goal – many group discussions are just that: a group kicking around ideas on a particular topic. That may lead to a goal ultimately...but it may not. It’s less formal, and may have no time constraints, or structured order, or agenda. Its leadership is usually less directive than that of a meeting. It emphasizes process (the consideration of ideas) over product (specific tasks to be accomplished within the confines of the meeting itself. Leading a discussion group is not the same as running a meeting. It’s much closer to acting as a facilitator, but not exactly the same as that either.

An effective group discussion generally has a number of elements:

- All members of the group have a chance to speak, expressing their own ideas and feelings freely, and to pursue and finish out their thoughts

- All members of the group can hear others’ ideas and feelings stated openly

- Group members can safely test out ideas that are not yet fully formed

- Group members can receive and respond to respectful but honest and constructive feedback. Feedback could be positive, negative, or merely clarifying or correcting factual questions or errors, but is in all cases delivered respectfully.

- A variety of points of view are put forward and discussed

- The discussion is not dominated by any one person

- Arguments, while they may be spirited, are based on the content of ideas and opinions, not on personalities

- Even in disagreement, there’s an understanding that the group is working together to resolve a dispute, solve a problem, create a plan, make a decision, find principles all can agree on, or come to a conclusion from which it can move on to further discussion

Many group discussions have no specific purpose except the exchange of ideas and opinions. Ultimately, an effective group discussion is one in which many different ideas and viewpoints are heard and considered. This allows the group to accomplish its purpose if it has one, or to establish a basis either for ongoing discussion or for further contact and collaboration among its members.

There are many possible purposes for a group discussion, such as:

- Create a new situation – form a coalition, start an initiative, etc.

- Explore cooperative or collaborative arrangements among groups or organizations

- Discuss and/or analyze an issue, with no specific goal in mind but understanding

- Create a strategic plan – for an initiative, an advocacy campaign, an intervention, etc.

- Discuss policy and policy change

- Air concerns and differences among individuals or groups

- Hold public hearings on proposed laws or regulations, development, etc.

- Decide on an action

- Provide mutual support

- Solve a problem

- Resolve a conflict

- Plan your work or an event

Possible leadership styles of a group discussion also vary. A group leader or facilitator might be directive or non-directive; that is, she might try to control what goes on to a large extent; or she might assume that the group should be in control, and that her job is to facilitate the process. In most group discussions, leaders who are relatively non-directive make for a more broad-ranging outlay of ideas, and a more satisfying experience for participants.

Directive leaders can be necessary in some situations. If a goal must be reached in a short time period, a directive leader might help to keep the group focused. If the situation is particularly difficult, a directive leader might be needed to keep control of the discussion and make

Why would you lead a group discussion?

There are two ways to look at this question: “What’s the point of group discussion?” and “Why would you, as opposed to someone else, lead a group discussion?” Let’s examine both.

What’s the point of group discussion?

As explained in the opening paragraphs of this section, group discussions are common in a democratic society. There are a number of reasons for this, some practical and some philosophical.

A group discussion:

- G ives everyone involved a voice . Whether the discussion is meant to form a basis for action, or just to play with ideas, it gives all members of the group a chance to speak their opinions, to agree or disagree with others, and to have their thoughts heard. In many community-building situations, the members of the group might be chosen specifically because they represent a cross-section of the community, or a diversity of points of view.

- Allows for a variety of ideas to be expressed and discussed . A group is much more likely to come to a good conclusion if a mix of ideas is on the table, and if all members have the opportunity to think about and respond to them.

- Is generally a democratic, egalitarian process . It reflects the ideals of most grassroots and community groups, and encourages a diversity of views.

- Leads to group ownership of whatever conclusions, plans, or action the group decides upon . Because everyone has a chance to contribute to the discussion and to be heard, the final result feels like it was arrived at by and belongs to everyone.

- Encourages those who might normally be reluctant to speak their minds . Often, quiet people have important things to contribute, but aren’t assertive enough to make themselves heard. A good group discussion will bring them out and support them.

- Can often open communication channels among people who might not communicate in any other way . People from very different backgrounds, from opposite ends of the political spectrum, from different cultures, who may, under most circumstances, either never make contact or never trust one another enough to try to communicate, might, in a group discussion, find more common ground than they expected.

- Is sometimes simply the obvious, or even the only, way to proceed. Several of the examples given at the beginning of the section – the group of parents concerned about their school system, for instance, or the college class – fall into this category, as do public hearings and similar gatherings.

Why would you specifically lead a group discussion?

You might choose to lead a group discussion, or you might find yourself drafted for the task. Some of the most common reasons that you might be in that situation:

- It’s part of your job . As a mental health counselor, a youth worker, a coalition coordinator, a teacher, the president of a board of directors, etc. you might be expected to lead group discussions regularly.

- You’ve been asked to . Because of your reputation for objectivity or integrity, because of your position in the community, or because of your skill at leading group discussions, you might be the obvious choice to lead a particular discussion.

- A discussion is necessary, and you’re the logical choice to lead it . If you’re the chair of a task force to address substance use in the community, for instance, it’s likely that you’ll be expected to conduct that task force’s meetings, and to lead discussion of the issue.

- It was your idea in the first place . The group discussion, or its purpose, was your idea, and the organization of the process falls to you.

You might find yourself in one of these situations if you fall into one of the categories of people who are often tapped to lead group discussions. These categories include (but aren’t limited to):

- Directors of organizations

- Public officials

- Coalition coordinators

- Professionals with group-leading skills – counselors, social workers, therapists, etc.

- Health professionals and health educators

- Respected community members. These folks may be respected for their leadership – president of the Rotary Club, spokesperson for an environmental movement – for their positions in the community – bank president, clergyman – or simply for their personal qualities – integrity, fairness, ability to communicate with all sectors of the community.

- Community activists. This category could include anyone from “professional” community organizers to average citizens who care about an issue or have an idea they want to pursue.

When might you lead a group discussion?

The need or desire for a group discussion might of course arise anytime, but there are some times when it’s particularly necessary.

- At the start of something new . Whether you’re designing an intervention, starting an initiative, creating a new program, building a coalition, or embarking on an advocacy or other campaign, inclusive discussion is likely to be crucial in generating the best possible plan, and creating community support for and ownership of it.

- When an issue can no longer be ignored . When youth violence reaches a critical point, when the community’s drinking water is declared unsafe, when the HIV infection rate climbs – these are times when groups need to convene to discuss the issue and develop action plans to swing the pendulum in the other direction.

- When groups need to be brought together . One way to deal with racial or ethnic hostility, for instance, is to convene groups made up of representatives of all the factions involved. The resulting discussions – and the opportunity for people from different backgrounds to make personal connections with one another – can go far to address everyone’s concerns, and to reduce tensions.

- When an existing group is considering its next step or seeking to address an issue of importance to it . The staff of a community service organization, for instance, may want to plan its work for the next few months, or to work out how to deal with people with particular quirks or problems.

How do you lead a group discussion?

In some cases, the opportunity to lead a group discussion can arise on the spur of the moment; in others, it’s a more formal arrangement, planned and expected. In the latter case, you may have the chance to choose a space and otherwise structure the situation. In less formal circumstances, you’ll have to make the best of existing conditions.

We’ll begin by looking at what you might consider if you have time to prepare. Then we’ll examine what it takes to make an effective discussion leader or facilitator, regardless of external circumstances.

Set the stage

If you have time to prepare beforehand, there are a number of things you may be able to do to make the participants more comfortable, and thus to make discussion easier.

Choose the space

If you have the luxury of choosing your space, you might look for someplace that’s comfortable and informal. Usually, that means comfortable furniture that can be moved around (so that, for instance, the group can form a circle, allowing everyone to see and hear everyone else easily). It may also mean a space away from the ordinary.

One organization often held discussions on the terrace of an old mill that had been turned into a bookstore and café. The sound of water from the mill stream rushing by put everyone at ease, and encouraged creative thought.

Provide food and drink

The ultimate comfort, and one that breaks down barriers among people, is that of eating and drinking.

Bring materials to help the discussion along

Most discussions are aided by the use of newsprint and markers to record ideas, for example.

Become familiar with the purpose and content of the discussion

If you have the opportunity, learn as much as possible about the topic under discussion. This is not meant to make you the expert, but rather to allow you to ask good questions that will help the group generate ideas.

Make sure everyone gets any necessary information, readings, or other material beforehand

If participants are asked to read something, consider questions, complete a task, or otherwise prepare for the discussion, make sure that the assignment is attended to and used. Don’t ask people to do something, and then ignore it.

Lead the discussion

Think about leadership style

The first thing you need to think about is leadership style, which we mentioned briefly earlier in the section. Are you a directive or non-directive leader? The chances are that, like most of us, you fall somewhere in between the extremes of the leader who sets the agenda and dominates the group completely, and the leader who essentially leads not at all. The point is made that many good group or meeting leaders are, in fact, facilitators, whose main concern is supporting and maintaining the process of the group’s work. This is particularly true when it comes to group discussion, where the process is, in fact, the purpose of the group’s coming together.

A good facilitator helps the group set rules for itself, makes sure that everyone participates and that no one dominates, encourages the development and expression of all ideas, including “odd” ones, and safeguards an open process, where there are no foregone conclusions and everyone’s ideas are respected. Facilitators are non-directive, and try to keep themselves out of the discussion, except to ask questions or make statements that advance it. For most group discussions, the facilitator role is probably a good ideal to strive for.

It’s important to think about what you’re most comfortable with philosophically, and how that fits what you’re comfortable with personally. If you’re committed to a non-directive style, but you tend to want to control everything in a situation, you may have to learn some new behaviors in order to act on your beliefs.

Put people at ease

Especially if most people in the group don’t know one another, it’s your job as leader to establish a comfortable atmosphere and set the tone for the discussion.

Help the group establish ground rules

The ground rules of a group discussion are the guidelines that help to keep the discussion on track, and prevent it from deteriorating into namecalling or simply argument. Some you might suggest, if the group has trouble coming up with the first one or two:

- Everyone should treat everyone else with respect : no name-calling, no emotional outbursts, no accusations.

- No arguments directed at people – only at ideas and opinions . Disagreement should be respectful – no ridicule.

- Don’t interrupt . Listen to the whole of others’ thoughts – actually listen, rather than just running over your own response in your head.

- Respect the group’s time . Try to keep your comments reasonably short and to the point, so that others have a chance to respond.

- Consider all comments seriously, and try to evaluate them fairly . Others’ ideas and comments may change your mind, or vice versa: it’s important to be open to that.

- Don’t be defensive if someone disagrees with you . Evaluate both positions, and only continue to argue for yours if you continue to believe it’s right.

- Everyone is responsible for following and upholding the ground rules .

Ground rules may also be a place to discuss recording the session. Who will take notes, record important points, questions for further discussion, areas of agreement or disagreement? If the recorder is a group member, the group and/or leader should come up with a strategy that allows her to participate fully in the discussion.

Generate an agenda or goals for the session

You might present an agenda for approval, and change it as the group requires, or you and the group can create one together. There may actually be no need for one, in that the goal may simply be to discuss an issue or idea. If that’s the case, it should be agreed upon at the outset.

How active you are might depend on your leadership style, but you definitely have some responsibilities here. They include setting, or helping the group to set the discussion topic; fostering the open process; involving all participants; asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion; summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, and ideas; and wrapping up the session. Let’s look at these, as well as some do’s and don’t’s for discussion group leaders.

- Setting the topic . If the group is meeting to discuss a specific issue or to plan something, the discussion topic is already set. If the topic is unclear, then someone needs to help the group define it. The leader – through asking the right questions, defining the problem, and encouraging ideas from the group – can play that role.

- Fostering the open process . Nurturing the open process means paying attention to the process, content, and interpersonal dynamics of the discussion all at the same time – not a simple matter. As leader, your task is not to tell the group what to do, or to force particular conclusions, but rather to make sure that the group chooses an appropriate topic that meets its needs, that there are no “right” answers to start with (no foregone conclusions), that no one person or small group dominates the discussion, that everyone follows the ground rules, that discussion is civil and organized, and that all ideas are subjected to careful critical analysis. You might comment on the process of the discussion or on interpersonal issues when it seems helpful (“We all seem to be picking on John here – what’s going on?”), or make reference to the open process itself (“We seem to be assuming that we’re supposed to believe X – is that true?”). Most of your actions as leader should be in the service of modeling or furthering the open process.

Part of your job here is to protect “minority rights,” i.e., unpopular or unusual ideas. That doesn’t mean you have to agree with them, but that you have to make sure that they can be expressed, and that discussion of them is respectful, even in disagreement. (The exceptions are opinions or ideas that are discriminatory or downright false.) Odd ideas often turn out to be correct, and shouldn’t be stifled.

- Involving all participants . This is part of fostering the open process, but is important enough to deserve its own mention. To involve those who are less assertive or shy, or who simply can’t speak up quickly enough, you might ask directly for their opinion, encourage them with body language (smile when they say anything, lean and look toward them often), and be aware of when they want to speak and can’t break in. It’s important both for process and for the exchange of ideas that everyone have plenty of opportunity to communicate their thoughts.

- Asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion . The leader should be aware of the progress of the discussion, and should be able to ask questions or provide information or arguments that stimulate thinking or take the discussion to the next step when necessary. If participants are having trouble grappling with the topic, getting sidetracked by trivial issues, or simply running out of steam, it’s the leader’s job to carry the discussion forward.

This is especially true when the group is stuck, either because two opposing ideas or factions are at an impasse, or because no one is able or willing to say anything. In these circumstances, the leader’s ability to identify points of agreement, or to ask the question that will get discussion moving again is crucial to the group’s effectiveness.

- Summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, or ideas . This task entails making sure that everyone understands a point that was just made, or the two sides of an argument. It can include restating a conclusion the group has reached, or clarifying a particular idea or point made by an individual (“What I think I heard you say was…”). The point is to make sure that everyone understands what the individual or group actually meant.

- Wrapping up the session . As the session ends, the leader should help the group review the discussion and make plans for next steps (more discussion sessions, action, involving other people or groups, etc.). He should also go over any assignments or tasks that were agreed to, make sure that every member knows what her responsibilities are, and review the deadlines for those responsibilities. Other wrap-up steps include getting feedback on the session – including suggestions for making it better – pointing out the group’s accomplishments, and thanking it for its work.

Even after you’ve wrapped up the discussion, you’re not necessarily through. If you’ve been the recorder, you might want to put the notes from the session in order, type them up, and send them to participants. The notes might also include a summary of conclusions that were reached, as well as any assignments or follow-up activities that were agreed on.

If the session was one-time, or was the last of a series, your job may now be done. If it was the beginning, however, or part of an ongoing discussion, you may have a lot to do before the next session, including contacting people to make sure they’ve done what they promised, and preparing the newsprint notes to be posted at the next session so everyone can remember the discussion.

Leading an effective group discussion takes preparation (if you have the opportunity for it), an understanding of and commitment to an open process, and a willingness to let go of your ego and biases. If you can do these things, the chances are you can become a discussion leader that can help groups achieve the results they want.

Do’s and don’ts for discussion leaders

- Model the behavior and attitudes you want group members to employ . That includes respecting all group members equally; advancing the open process; demonstrating what it means to be a learner (admitting when you’re wrong, or don’t know a fact or an answer, and suggesting ways to find out); asking questions based on others’ statements; focusing on positions rather than on the speaker; listening carefully; restating others’ points; supporting your arguments with fact or logic; acceding when someone else has a good point; accepting criticism; thinking critically; giving up the floor when appropriate; being inclusive and culturally sensitive, etc.

- Use encouraging body language and tone of voice, as well as words . Lean forward when people are talking, for example, keep your body position open and approachable, smile when appropriate, and attend carefully to everyone, not just to those who are most articulate.

- Give positive feedback for joining the discussion . Smile, repeat group members’ points, and otherwise show that you value participation.

- Be aware of people’s reactions and feelings, and try to respond appropriately . If a group member is hurt by others’ comments, seems puzzled or confused, is becoming angry or defensive, it’s up to you as discussion leader to use the ground rules or your own sensitivity to deal with the situation. If someone’s hurt, for instance, it may be important to point that out and discuss how to make arguments without getting personal. If group members are confused, revisiting the comments or points that caused the confusion, or restating them more clearly, may be helpful. Being aware of the reactions of individuals and of the group as a whole can make it possible to expose and use conflict, or to head off unnecessary emotional situations and misunderstandings.