An Essay on Criticism Summary & Analysis by Alexander Pope

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Criticism" seeks to lay down rules of good taste in poetry criticism, and in poetry itself. Structured as an essay in rhyming verse, it offers advice to the aspiring critic while satirizing amateurish criticism and poetry. The famous passage beginning "A little learning is a dangerous thing" advises would-be critics to learn their field in depth, warning that the arts demand much longer and more arduous study than beginners expect. The passage can also be read as a warning against shallow learning in general. Published in 1711, when Alexander Pope was just 23, the "Essay" brought its author fame and notoriety while he was still a young poet himself.

- Read the full text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

The Full Text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

1 A little learning is a dangerous thing;

2 Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

3 There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

4 And drinking largely sobers us again.

5 Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

6 In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts,

7 While from the bounded level of our mind,

8 Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

9 But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise

10 New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

11 So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try,

12 Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky;

13 The eternal snows appear already past,

14 And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

15 But those attained, we tremble to survey

16 The growing labours of the lengthened way,

17 The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes,

18 Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Summary

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” themes.

Shallow Learning vs. Deep Understanding

- See where this theme is active in the poem.

Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts, In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts, While from the bounded level of our mind, Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

Lines 11-14

So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try, Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky; The eternal snows appear already past, And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

Lines 15-18

But those attained, we tremble to survey The growing labours of the lengthened way, The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes, Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Symbols

The Mountains/Alps

- See where this symbol appears in the poem.

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- See where this poetic device appears in the poem.

Extended Metaphor

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” vocabulary.

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- A little learning

- Pierian spring

- Bounded level

- Short views

- The lengthened way

- See where this vocabulary word appears in the poem.

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

Rhyme scheme, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” speaker, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” setting, literary and historical context of “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing”, more “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” resources, external resources.

The Poem Aloud — Listen to an audiobook of Pope's "Essay on Criticism" (the "A little learning" passage starts at 12:57).

The Poet's Life — Read a biography of Alexander Pope at the Poetry Foundation.

"Alexander Pope: Rediscovering a Genius" — Watch a BBC documentary on Alexander Pope.

More on Pope's Life — A summary of Pope's life and work at Poets.org.

Pope at the British Library — More resources and articles on the poet.

LitCharts on Other Poems by Alexander Pope

Ode on Solitude

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

- Try the new Google Books

- Advanced Book Search

Get this book in print

- Barnes&Noble.com

- Books-A-Million

- Find in a library

- All sellers »

Selected pages

Other editions - View all

Common terms and phrases, bibliographic information.

Alexander Pope

An essay on criticism: part 1.

Si quid novisti rectius istis, Candidus imperti; si non, his utere mecum [If you have come to know any precept more correct than these, share it with me, brilliant one; if not, use these with me] (Horace, Epistle I.6.67)

#Couplet #Epistle

Other works by Alexander Pope...

Thou who shalt stop, where Thames… Shines a broad Mirror thro’ the s… Where ling’ring drops from min’ral… And pointed Crystals break the sp… Unpolish’d Gems no ray on Pride b…

Fain would my Muse the flow’ry Tr… And humble glories of the youthful… Where opening Roses breathing swe… And soft Carnations show’r their… Where Lilies smile in virgin robe…

Silence! coeval with Eternity; Thou wert, ere Nature’s—self bega… 'Twas one vast Nothing, all, and… II. Thine was the sway, ere heav’n was…

Lycidas. Thyrsis, the music of that murm’ri… Is not so mournful as the strains… Nor rivers winding thro’ the vales… So sweetly warble, or so smoothly…

I am his Highness’ dog at Kew; Pray tell me, sir, whose dog are y…

Father of all! in every age, In every clime adored, By saint, by savage, and by sage, Jehovah, Jove, or Lord! Thou Great First Cause, least un…

‘Sir, I admit your general rule, That every poet is a fool. But you yourself may serve to show… Every fool is not a poet.’

Of Manners gentle, of Affections… In Wit, a Man; Simplicity, a Chi… With native Humour temp’ring virt… Form’d to delight at once and lash… Above Temptation, in a low Estate…

When simple Macer, now of high re… First fought a Poet’s Fortune in… 'Twas all th’ Ambition his high s… To wear red stockings, and to dine… Some Ends of verse his Betters mi…

The Mighty Mother, and her son wh… The Smithfield muses to the ear o… I sing. Say you, her instruments… Called to this work by Dulness, J… You by whose care, in vain decried…

First in these fields I try the s… Nor blush to sport on Windsor’s b… Fair Thames, flow gently from thy… While on thy banks Sicilian Muses… Let vernal airs tho’ trembling osi…

When other fair ones to the shades… Still Chloe, Flavin, Delia, stay… Those ghosts of beauty wandering h… And haunt the places where their h…

Of gentle Philips will I ever sin… With gentle Philips shall the val… My numbers too for ever will I va… With gentle Budgell and with gent… Or if in ranging of the names I j…

Pallas grew vapourish once, and od… She would not do the least right t… Either for goddess, or for god, Nor work, nor play, nor paint, nor… Jove frown’d, and, ‘Use,’ he crie…

With no poetic ardour fir’d I press the bed where Wilmot lay; That here he lov’d, or here expir’… Begets no numbers grave or gay. Beneath thy roof, Argyle, are bre…

Poetry Prof

Read, Teach, Study Poetry

from An Essay on Criticism

Join Alexander Pope on a metaphysical journey of discovery… that will last a lifetime.

“[It is] difficult to know which part to prefer, when all is equally beautiful and noble.” Weekly Miscellany comments on the poetry of Alexander Pope

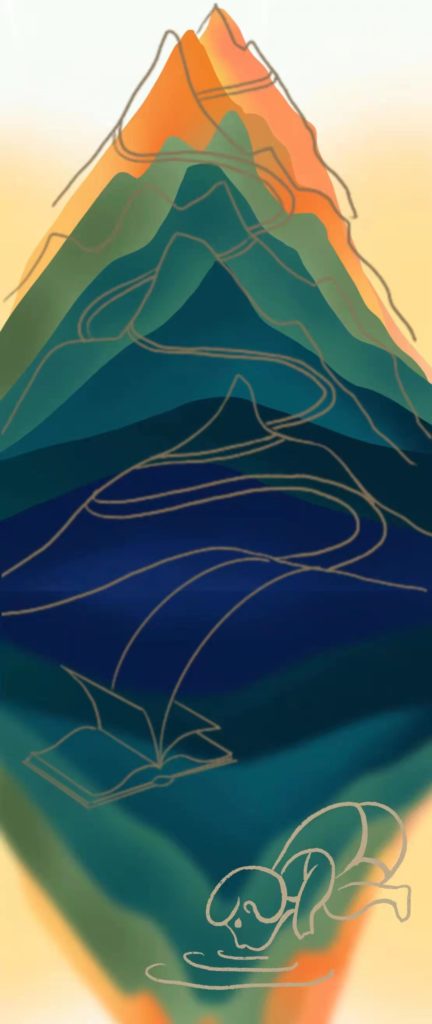

Alexander Pope spent his childhood in Windsor forest and, from an early age, gained a keen appreciation for nature. Later in his life he lived in a property by the River Thames in London where he cultivated his own garden that he opened for visitors. In today’s poem, written in 1709, we can see this love of the natural world through his shaping of elements of the landscape into an extended metaphor for knowledge. This landscape is vast and mountainous: the Alps , Europe’s largest mountain range are a prominent feature, as are hills, vales , an endless sky and eternal snows . Compared to this vast landscape, people are almost insignificant. Their role in the poem is to act as explorers who set off on a journey of discovery, trying to conquer the highest mountains by ascending to the summit; we tempt the heights of Arts… the towering Alps we try… Finally, despite being almost exhausted by his efforts, the explorer realises that his journey has barely begun; the mountain vista stretches ahead, unbroken, into the distance:

A poem’s central idea, often developed into an extended metaphor, is known as a conceit . Unlocking the first couplet should provide you the key to Pope’s conceit in An Essay on Criticism . Pope begins with a warning that:

The Pierian Spring is an important place in Greek Mythology , the source of a river of knowledge that was associated with the nine ancient Muses, themselves a metaphor for artistic inspiration. In this poem, it’s part of the landscape that functions as an extended metaphor for learning. It might seem strange that Pope begins by giving his readers a warning to taste not the waters of this river. However, it’s important to realise that Pope isn’t saying not to drink from the well of knowledge at all. He tells us to drink deep , emphasising his instruction with both alliterative D and using the imperative tense (where the verb is placed at the beginning of the line or phrase). To Pope’s mind, learning is seductive and intoxicating . Once you set out on the journey of learning, or take even a tiny sip from the wellspring of knowledge, you won’t be able to resist the temptation to learn more. Therefore, he suggests that you either prepare to immerse yourself completely in the Pierian Spring , or don’t drink at all.

Once you’ve discovered the connotations of Pierian Spring , the rest of the poem can be read as a warning (or criticism ) of anyone who is rash enough not to follow Pope’s instruction. Should you venture unprepared into the unknown, you must be clear about your limitations. As a spring is the starting point of a river, so too is it the starting point of Pope’s extended metaphor . From here, the reader sets out on a journey into an imposing mountainous landscape that, while initially appearing it can be ‘climbed’ or conquered, actually keeps expanding into an endless vista. No matter how far the explorer climbs, the top of the mountain never gets any nearer. Heights, lengthening way, increasing prospect and, most telling of all, eternal snows conjure the visual image of the landscape metaphysically stretching out in front of our weary eyes. Individual people are tiny and easily lost in this ever-shifting world. Pope creates a contrast between the boundless landscape and the bounded limits of human perception. At the last, the human explorer is tired by his efforts to conquer these mountains of knowledge – but the poem ends by revealing that he’d barely even gotten started on his journey: Hills peep o’er hills; Alps upon Alps arise .

Before we get too much further into the discussion of Pope’s ‘essay’, it might be helpful to place these lines in context. Despite the way they seem to be a complete poem in themselves, they are actually part of a much longer poem which stretches to three parts and a total of 744 lines! The eighteen-line extract you’ve read constitutes the second verse of Part 2 and it may help you to know that, in the first verse, Pope singled out pride as the characteristic that would eventually lead to the downfall of his explorer. Here are four lines from earlier in the Essay:

In this short sample, you can see the names Pope calls people who rush off on foolhardy adventures without taking the time to properly prepare: blind man , weak head and fools ! Younger readers might not enjoy this interpretation, but Pope finds the overconfidence of young people most problematic, associating youth with a kind of recklessness that, in hindsight, is misplaced.

You may argue that qualities such as fearless and passionate (fired) seem like compliments; but I detect a note of criticism in Pope’s words; he suggests that young people confuse emotion with clear thinking and they are too eager to plunge into the unknown. There’s an emphasis on speed and rashness ( pleased at first; at first sight ) that cannot last, like a novice marathon runner who goes sprinting out of the blocks while older, more wily competitors know to save themselves for the challenges ahead. While the young explorer does encounter some early success (implied by words like mount , more advanced , attained and, more significantly by an image : tread the sky ), the race is longer than the runner thought and inevitably the pace must sag. Later in the poem, positive diction disappears and words like trembling , growing labours , and tired take over as the true scale of the challenge becomes apparent. Sharp-eyed readers will already have noticed that the image of ‘treading the sky’ was in fact a simile : seem to tread the sky. Subtly, Pope’s use of a simile implies that any success the explorer thought he’d achieved wasn’t actually real.

The implication that over-enthusiasm can cloud good judgment can be traced through diction to do with looking and seeing: a t first sight, short views, see, behold, appear, survey, eyes and peep pepper the poem and convey the poet’s belief that, to our detriment, we can be short-sighted and tunnel-visioned. The eighth line of the poem is entirely concerned with this idea: short views we take, nor see the lengths behind paints a picture of a young explorer who only looks in one direction – eyes fixed straight ahead – and so misses the bigger picture.

While the poem is certainly didactic (it’s trying to impart a lesson), Pope’s tone of voice is not too condescending or stand-offish because he includes himself in his criticism as well. Throughout the poem the words us, we and our soften his accusations so there’s never a ‘them-and-us’ divide between young and old. In fact, Pope was only 21 years old when he finished his Essay on Criticism , so use your mind’s ear to imagine him speaking ruefully from experience, rather than as a nagging or pestering adult complaining about ‘young people today.’ The line Fired at first sight by what the Muse imparts is revealing in this regard. Alluding to the nine Muses of Greek mythology , this line personifies poetic inspiration, so in one sense the extended metaphor of trying to conquer an unknowable landscape represents his own experiences of writing poetry. ‘Meta-poems’ (poems about the writing of poems) actually have a name: ars poetica . Pope implies that rushing off on a path of artistic endeavour without realising the true extent of the commitment that entails is a mistake that he himself has made in his own attempts at writing.

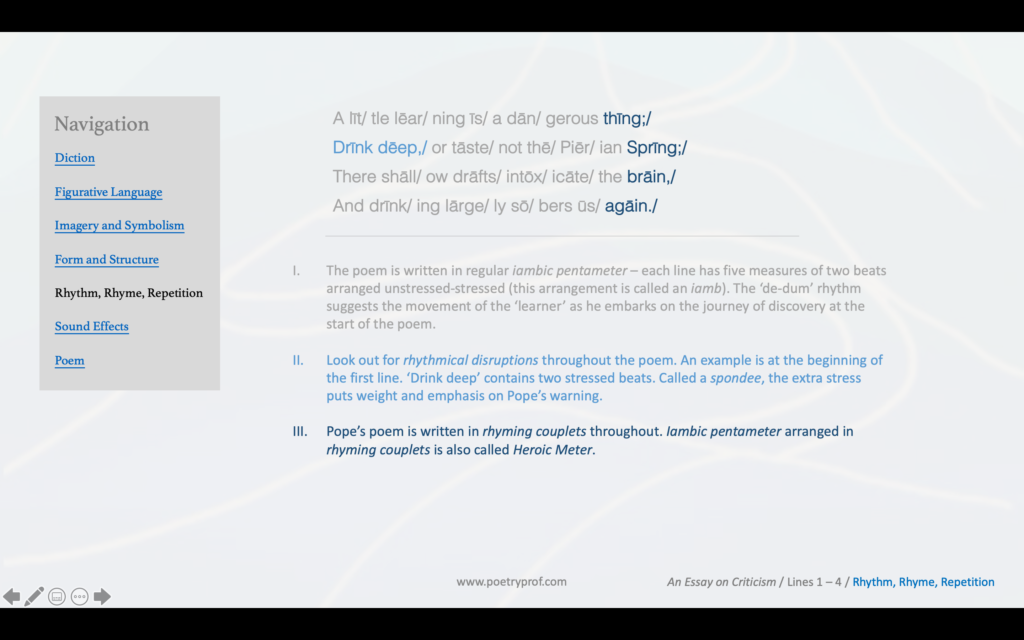

If you’re a student reading this who thinks you might be able to use Pope’s poem as an excuse not to do your homework or give up on your own writing: you shouldn’t be too rash. Pope’s not suggesting we should quit. Instead, he’s warning us that what might seem like a shallow pool is in fact a deep river of knowledge. Once you jump in, the current will sweep you away and there’s no going back. The poem is a criticism of unpreparedness and arrogance rather than an acknowledgement of futility. In fact, an element of form suggests that, for all the faults Pope has pointed out in young people who are too confident in their limited abilities, it is much more praiseworthy to try and fail to conquer the heights than never to try at all. The poem is written in iambic pentameter that is constant and regular as if, no matter how tough the going gets, the young explorer doesn’t give up. Compare these two lines, with iambic accents marked, from the beginning and end of the poem to see how the rhythm is unfailing:

More, the poem is arranged in rhyming couplets (the rhyme scheme is AA, BB, CC and so on). Rhyming couplets written in iambic pentameter are traditionally known by a more dramatic name: heroic couplets . Pope was widely considered to be the master of writing poetry in heroic couplets ; using them here implies that Pope ultimately believes any young person who’s brave – or foolhardy – enough to embark upon the lifelong journey of learning is worthy of praise.

The structure of Pope’s poetical essay matches the message he’s trying to convey – that, once you start learning, you won’t be able to stop. Look carefully at the punctuation marks, in particular his use of full stops . You’ll find the first one at the end of the fourth line, the second after the tenth and the third at the end of the poem (after eighteen lines). In other words, if the poem was arranged in verses, the first verse would be nice and short at only four lines, the second would stretch to six, but the final verse would have doubled in length to eight lines. Expanding sentences represent the conceit – a little learning is a dangerous thing – and match the images of the landscape expanding ( eternal snows , increasing prospect, lengthening way ) as you read further down the poem.

The end of the poem brings Pope’s criticism to its conclusion. We see the young explorer break through the eternal snows , climb above the clouds, and stand triumphantly on the mountain top, proudly surveying his achievements. Only now does he take a moment to look more deliberately at the mountains he’s trying to conquer:

Be alert to two words that might seem insignificant: appear and seem , words that signal the mistake the explorer made; he thought that he had already past the bulk of his journey. Read carefully to punctuation as well, and you’ll see the colon – a longer pause, which creates a caseura – representing the traveler pausing at the moment of his triumph… and it’s here that realisation finally dawns. Despite the difficulty of his climb thus far, the landscape ( increasing prospect ) stretches out endlessly in front of him: Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise . Here, repetition mixes with all that increasing and lengthening diction to create a surreal image of an ever-expanding landscape stretching out ahead. You might also notice P sounds peppering the last two lines of the poem in the words p ee p , Al p s, Al p s, and p ros p ect . Coming from a category of alliteration called plosive , this sound is excellent at conveying a release of negative emotion, as it is formed by pushing air through closed lips. The sound helps us perceive the taste of victory turning to defeat as the weary traveler’s shoulders slump at the prospect of the endless climb still to come.

What does Pope offer as a solution? He already warned us at the start of the poem: drinking largely sobers us again . Suddenly, the importance of the word sober becomes clear. While the idea of heading off on this journey of discovery was intoxicating , firing up those with passion to learn, discover and explore – the reality is very different. That young, over-confident learner/explorer is gone, replaced by a wiser, but more world-weary traveler who can finally see the true scale of the task ahead. By now it’s too late, he’s stuck on the mountain top and there’s only one thing he can do – go onwards!

So drink deep and be prepared to encounter much more than you expected when you set out on your journey.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- from Essay on Man by Alexander Pope

An Essay on Criticism was not the only poetical essay written by Pope. French writer Voltaire so admired Pope’s Essay on Man that he arranged for its translation into French and from there it spread around Europe.

- Marrysong by Dennis Scott

As in Pope’s poem, Scott creates a metaphor of the landscape to represent his marriage. He is an explorer in a strange land – each time the explorer glances up from his map, the landscape has changed and he’s lost again.

- Through the Dark Sod – As Education by Emily Dickinson

Victorians brought many different associations to all kinds of plants and flowers. In this Emily Dickinson poem, the lily represents beauty, purity and rebirth. This link will also take you to a fantastic blog which aims to read and provide comment on all of Emily Dickinson’s poems. So that’s 1 down, and nearly 2000 more to go…

- In the Mountains by Wang Wei

Often spoken of with the same reverence as Li Bai and Du Fu, Wang Wei is a famous imagist poet in China. In these exquisite portrait poems, Wang Wei paints pictures of the impressive landscapes of his mountain home.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying An Essay on Criticism at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs;

- A sample analytical paragraph for essay writing;

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem;

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on analysing diction and explaining lexical fields ;

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap;

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision;

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism ? Do you agree that the poem somewhat singles out young people? Can you relate to Pope’s messages about the temptations of learning? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

One comment

I would like to have an explanation of the frontispiece appended to the 1711 edition of An Essay on Criticism. Is it related to Pierrian Spring and the Muse of Poetry referred to in the poem. I would like to know more on it.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

The Meaning and Origin of ‘A Little Learning is a Dangerous Thing’

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library , Dr Oliver Tearle explores the origins of a famous quotation – and its less famous source

‘A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.’ This line is often quoted, but it’s actually, technically, a misquotation. What’s more, the meaning of this aperçu is worth analysing more closely, because it is open to misinterpretation as well as misquotation. Let’s take a look at the origins of ‘a little knowledge is a dangerous thing’ – or, more accurately, ‘a little learning is a dangerous thing’.

The source and origin for this quotation is Alexander Pope (1688-1744), one of the leading neoclassical or Augustan poets of the first half of the eighteenth century. Pope was a fascinating figure: as a young boy he was expelled from Twyford School for writing a satire about one of his teachers, and he continued to lose friends and create enemies through not being afraid to speak out and criticise those with whom he disagreed. (For a time, while fearing attacks from especially vicious rivals, Pope rarely left his house without a brace of pistols and his dog, a Great Dane named Bounce.)

Sadly, outside of academia, few people read Pope now because he is perceived as dry and emotionless (and therefore dull), and even in the late nineteenth century, his fellow master of the one-liner, Oscar Wilde, was quipping, ‘There are two ways of disliking poetry. One way is to dislike it, and the other is to read Pope.’

Pope’s poem ‘An Essay on Criticism’ gave us not only ‘A little learning is a dangerous thing’ but also ‘ To err is human; to forgive, divine ’ and ‘ For fools rush in where angels fear to tread .’ Given how proverbial all three of this statements have now become, that’s a pretty impressive hit rate for a single poem – and, what’s more, one written when its author was still only 23!

A little learning is a dang’rous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, And drinking largely sobers us again. Fir’d at first sight with what the Muse imparts, In fearless youth we tempt the heights of arts, While from the bounded level of our mind, Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind, But more advanc’d, behold with strange surprise New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

As the title of Pope’s poem, ‘An Essay on Criticism’, makes clear, Pope is specifically advising critics – especially literary critics – when he opines, ‘A little learning is a dang’rous thing’ (the elision in ‘dang’rous’, to indicate that the word should be pronounced as two syllables rather than three to keep with the iambic pentameter metre, is not often preserved when people quote Pope in their writing).

The Pierian Spring in Macedonia was sacred to the Muses, so in order to ‘taste the Pierian spring’ the critic (and poet?) needs to ‘drink deep’, i.e., read widely. A little learning is a dangerous thing because it can lead the critic to think they know it all when they, in fact, know very little. A little learning is more dangerous than complete ignorance, because it gives you the illusion of knowledge when you, in fact, have only cursory knowledge of the subject:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, And drinking largely sobers us again.

In other words, drinking only shallowly from the spring will make you drunk with your own knowledge, but drinking deeply or ‘largely’ brings you back to reality so you have a fairer and more accurate assessment of what you do and don’t know. So it is with learning: the more we learn, as the old adage has it, the less we know.

Pope, as a classicist, would have been familiar with the Delphic Oracle of Ancient Greece, who, asked to name who the wisest person in Athens was, proclaimed that it was Socrates, ‘for he alone is aware that he knows nothing’.

Pope, then, isn’t claiming that learning in itself is dangerous: but a little (as contrasted with a great deal ) is. Anyone who’s found themselves collared by the pub bore or in an argument on social media over some historical, scientific, or even literary topic will probably be able to attest to that.

Pope’s ‘An Essay on Criticism’ is, as I say, a didactic and discursive poem recommending good things for a critic to do. Much of his advice, though, can be extrapolated beyond the realm of literary critics and reviewers of poetry. Good taste and knowing one’s own limitations, for instance, are universal rules to live by, and poets as well as critics would do well to heed them.

So in many ways, ‘A little learning is a dangerous thing’ (or ‘dang’rous thing’) is a line that nearly encapsulates Pope’s argument in ‘An Essay on Criticism’. More mischief is arguably caused by those who think they know it all than those who know they know nothing.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

3 thoughts on “The Meaning and Origin of ‘A Little Learning is a Dangerous Thing’”

- Pingback: A Little Learning is a Dangerous Thing – Education Technology

Thank you very much for this very interesting post. I hadn’t given much thought to the phrase “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing” as being a quote from a poem that had passed into common speech as a proverb until I spotted it in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. I enjoyed how you expanded or little bit of knowledge with very interesting facts about the author and his life. The information in this snippet is much more engaging than what I read in The Oxford Book of Quotations – which merely gives you the name of the author and sometimes a bit more of the text from which the quote was taken.

- Pingback: ‘Fools Rush in Where Angels Fear to Tread’: Meaning and Origin – Interesting Literature

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Essay on Criticism for Students and Children

500+ words essay on criticism .

It is tough for anyone to criticism well. For some, criticism is a good thing while others disagree. Criticism in itself is one of those words that looks like negative. Thus, it gives a feeling of unwilling to accept or making a massive disagreement or being pessimistic. But to everyone’s surprise, it is not the case. Criticism is often different than what people perceive. The essay on criticism gives you an insight into the pros and cons of the criticism.

Criticism is expressing the disagreement for something or someone that is generally based on perceived faults, beliefs, and mistakes. So, the main point here is whether to consider criticism as good or bad. Also, if we go by the meaning of the word criticism then criticizing someone is bad. Also, simultaneously this might lead to improving the person who is being criticized. So, he/she is becoming a better person and does not repeat the mistakes is considered as providing criticism to be good. Thus, this depends entirely on the perceived value that is hidden behind the criticism.

A Good Part of the Criticism

Scope for improvements .

Constructive criticism will lead to locating the fault or mistakes that are made by the people. So, the people can work upon it and thereby improve their activities so a heedful and better life can be lived. Criticism calls for improvement on one plane and thereby avoiding the issues unwanted on the other side.

Expert and Credible Status

When the criticism is constructive it always makes the criticizer a central figure among the people. Thus, more honors and credibility is given and so criticism would rather be considered as expert advice. Thus, it will add to the status quo of the person that is criticizing.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

The Bad Side of Criticism

Leads to a feeling of demotivation.

A person that is being constantly criticized may feel at tines demotivated. So, this is because of the fact that his/her efforts have not been justifiably and rightfully appreciated. Thus, it may further lead to increase in hesitation in moving forward.

The Danger of Creating a Destructive and False Image

There are many times that it can occur that the people that criticize are seen as the villain of the society. Thus his/her image gets automatically shattered as well as abruptly changed. So, doing criticism may lead adversely to the criticizer as well.

So, we can understand that if the criticism is done in a constructive and positive way that this may lead to a good and fair outcome. Also, if it is done destructively than it may lead to adverse effects on both society as well as personal level.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

✍️Essay on Criticism for Students: Samples in 150 Words, 200 Words

- Updated on

- Mar 11, 2024

On this page, we will discuss some samples of essay on criticism. Such essay topics are part of the school curriculum, where students are assessed based on their writing skills.

Criticism is the process of judging someone or something, be it art, the character of a human, a movie, or anything else. Criticism is essential to grow in life. It can be positive or negative. It compares and evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of any person, or his work. How we face criticism determines our personality. Most people get offended and do not wish to take any criticism or judgment from the other person. Criticism is not what people perceive. Read this blog to get a sample essay on criticism and learn about various perspectives of criticism!

Check out our 200+ Essay Topics for School Students in English

Table of Contents

- 1 Short Essay on Criticism for Students

- 2 Essay on Criticism for Students 150 Words

- 3.1 📌 Pros of Criticism

- 3.2 📌 Cons of Criticism

Also Read: Speech on Fear

Short Essay on Criticism for Students

‘Criticism is a crucial part of the creative field . It is used to judge any situation, piece of art, person, movie, work, etc. Criticism can be better understood as two sides of coins. Just as a coin has two sides, criticism also has two sides. It could be constructive or destructive. Some people positively take criticism whereas some do not healthily accept criticism and get offended.

One should critically observe the work or thing before passing any judgement or criticising someone. If we look at the meaning of criticism it is the process of analysing something and expressing disagreement by looking at the faults. But the interpretation of criticism could be good or bad.

Criticism is a fundamental aspect of human interaction and progress. Understanding its different sides is very important for positive growth in life.’

Essay on Criticism for Students 150 Words

Criticism is an act of expressing one’s opinion about something. It entirely depends on the person who perceives it. If the person does not take criticism in a sporting way then it might lead to negative or destructive feelings against the person who judges the work. Criticism means analyzing something with a set standard to point out its strengths and weaknesses.

It is a valuable tool and a unique perspective to do the same work differently. Learning to deal with criticism will help a person to snatch the opportunity to improve. If one does not constructively take criticism then the chance to improve and do better will be missed and you could not analyze the other method to do any task.

Dealing with criticism in a healthy way is essential for positive growth. It can be done by:

- Accepting criticism and listening attentively.

- Asking questions for clarification.

- Taking feedback without any disagreement.

- Implementing the critic comments to improve the work.

Also Read: Essay on Sustainable Development

Essay on Criticism for Students 200 Words

Criticism is the act of representing one’s judgment based on a comparison with the standard. The outcome of criticism is determined by how the recipient perceives the criticism. Besides this, there are different types of criticism like political criticism, thematic criticism, formal criticism, historical criticism, etc. Criticism is mostly used in the field of art to judge the work of the artist.

The pros and cons of criticism are discussed below:

📌 Pros of Criticism

If you take the criticism in a considerate manner then, it could benefit you in a lot of ways. Criticism increases the scope of improvement and helps in reducing errors.

It provides expert advice and aids in attaining the credibility of the specified work. Crticicisng helps to develop critical thinking skills and thereby prepares you to face the real world. It is important for every phase of life because it enhances the ability to consider other’s opinions.

📌 Cons of Criticism

Apart from the positive aspects, there are some disadvantages of criticism. Those, who are not able to listen to other’s opinions or people who feel offended by attaining any kind of criticism could sometimes develop a feeling of demotivation.

Some people also tend to create negative or destructive images of the critic and intentionally work against the feedback given to them just to offend the critic.

Also Read: Essay on Gender Discrimination

Relevant Blogs

Students are like clay and it’s the responsibility of parents and teachers to mould them in perfect shape. Criticism helps students to read and write and prepares them for the real world.

Criticism is very important in life. One should take criticism seriously and try to look at a new perspective. Criticism could be constructive and it can give you an opportunity to improve and perform better.

Criticism refers to the act of judging someone or something critically. It could be positive or negative. Most of the time criticism is an act of disapproval.

To introduce criticism in an essay, make sure to be crisp and clear and mention the meaning of criticism in simple words. You can also include a critic’s opinion to start the introductory paragraph and then continue to write about your opinion with respect to the critic’s opinion.

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu .

Kajal Thareja

Hi, I am Kajal, a pharmacy graduate, currently pursuing management and is an experienced content writer. I have 2-years of writing experience in Ed-tech (digital marketing) company. I am passionate towards writing blogs and am on the path of discovering true potential professionally in the field of content marketing. I am engaged in writing creative content for students which is simple yet creative and engaging and leaves an impact on the reader's mind.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Whoa, nelly! It's time to upgrade your browser for a better experience. Until then, this website may not work as intended.

A Short Essay on Critics

by Margaret Fuller

If an essay on Criticism were a serious matter; for, though this age be emphatically critical, the writer would still find it necessary to investigate the laws of criticism as a science, to settle its conditions as an art. Essays, entitled critical, are epistles addressed to the public, through which the mind of the recluse relieves itself of its impressions. Of these the only law is, “Speak the best word that is in thee.” Or they are regular articles got up to order by the literary hack writer, for the literary mart, and the only law is to make them plausible. There is not yet deliberate recognition of a standard of criticism, though we hope the always strengthening league of the republic of letters must ere long settle laws on which its Amphictyonic council may act. Meanwhile let us not venture to write on criticism, but, by classifying the critics, imply our hopes and thereby our thoughts.

First, there are the subjective class (to make use of a convenient term, introduced by our German benefactors). These are persons to whom writing is no sacred, no reverend employment. They are not driven to consider, not forced upon investigation by the fact, that they are deliberately giving their thoughts an independent existence, and that it may live to others when dead to them. They know no agonies of conscientious research, no timidities of self-respect. They see no ideal beyond the present hour, which makes its mood an uncertain tenure. How things affect them now they know; let the future, let the whole take care of itself. They state their impressions as they rise, of other men’s spoken, written, or acted thoughts. They never dream of going out of themselves to seek the motive, to trace the law of another nature. They never dream that there are statures which cannot be measured from their point of view. They love, they like, or they hate; the book is detestable, immoral, absurd, or admirable, noble, of a most approved scope;—these statements they make with authority, as those who bear the evangel of pure taste and accurate judgment, and need be tried before no human synod. To them it seems that their present position commands the universe.

Thus the essays on the works of others, which are called criticisms, are often, in fact, mere records of impressions. To judge of their value you must know where the man was brought up, under what influences,—his nation, his church, his family even. He himself has never attempted to estimate the value of these circumstances, and find a law or raise a standard above all circumstances, permanent against all influence. He is content to be the creature of his place, and to represent it by his spoken and written word. He takes the same ground with a savage, who does not hesitate to say of the product of a civilization on which he could not stand, “It is bad,” or “It is good.”

The value of such comments is merely reflex. They characterize the critic. They give an idea of certain influences on a certain act of men in a certain time or place. Their absolute, essential value is nothing. The long review, the eloquent article by the man of the nineteenth century, are of no value by themselves considered, but only as samples of their kind. The writers were content to tell what they felt, to praise or to denounce without needing to convince us or themselves. They sought not the divine truths of philosophy, and she proffers them not if unsought.

Then there are the apprehensive. These can go out of themselves and enter fully into a foreign existence. They breathe its life; they live in its law; they tell what it meant, and why it so expressed its meaning. They reproduce the work of which they speak, and make it better known to us in so far as two statements are better than one. There are beautiful specimens in this kind. They are pleasing to us as bearing witness of the genial sympathies of nature. They have the ready grace of love with somewhat of the dignity of disinterested friendship. They sometimes give more pleasure than the original production of which they treat, as melodies will sometimes ring sweetlier in the echo. Besides there is a peculiar pleasure in a true response; it is the assurance of equipoise in the universe. These, if not true critics, come nearer the standard than the subjective class, and the value of their work is ideal as well as historical.

Then there are the comprehensive, who must also be apprehensive. They enter into the nature of another being, and judge his work by its own law. But having done so, having ascertained his design and the degree of his success in fulfilling it, thus measuring his judgment, his energy, and skill, they do also know how to put that aim in its place, and how to estimate its relations. And this the critic can only do who perceives the analogies of the universe, and how they are regulated by an absolute, invariable principle. He can see how far that work expresses this principle, as well as how far it is excellent in its details. Sustained by a principle, such as can be girt within no rule, no formula, he can walk around the work, he can stand above it, he can uplift it, and try its weight. Finally, he is worthy to judge it.

Critics are poets cut down, says some one by way of jeer; but, in truth, they are men with the poetical temperament to apprehend, with the philosophical tendency to investigate. The maker is divine; the critic sees this divine, but brings it down to humanity by the analytic process. The critic is the historian who records the order of creation. In vain for the maker, who knows without learning it, but not in vain for the mind of his race.

The critic is beneath the maker, but is his needed friend. What tongue could speak but to an intelligent ear, and every noble work demands its critic. The richer the work, the more severe should be its critic; the larger its scope, the more comprehensive must be his power of scrutiny. The critic is not a base caviller, but the younger brother of genius. Next to invention is the power of interpreting invention; next to beauty the power of appreciating beauty.

And of making others appreciate it; for the universe is a scale of infinite gradation, and below the very highest, every step is explanation down to the lowest. Religion, in the two modulations of poetry and music, descends through an infinity of waves to the lowest abysses of human nature. Nature is the literature and art of the divine mind; human literature and art the criticism on that; and they, too, find their criticism within their own sphere.

The critic, then, should be not merely a poet, not merely a philosopher, not merely an observer, but tempered of all three. If he criticise the poem, he must want nothing of what constitutes the poet, except the power of creating forms and speaking in music. He must have as good an eye and as fine a sense; but if he had as fine an organ for expression also, he would make the poem instead of judging it. He must be inspired by the philosopher’s spirit of inquiry and need of generalization, but he must not be constrained by the hard cemented masonry of method to which philosophers are prone. And he must have the organic acuteness of the observer, with a love of ideal perfection, which forbids him to be content with mere beauty of details in the work or the comment upon the work.

There are persons who maintain, that there is no legitimate criticism, except the reproductive; that we have only to say what the work is or is to us, never what it is not. But the moment we look for a principle, we feel the need of a criterion, of a standard; and then we say what the work is not , as well as what it is ; and this is as healthy though not as grateful and gracious an operation of the mind as the other. We do not seek to degrade but to classify an object, by stating what it is not. We detach the part from the whole, lest it stand between us and the whole. When we have ascertained in what degree it manifests the whole, we may safely restore it to its place, and love or admire it there ever after.

The use of criticism, in periodical writing, is to sift, not to stamp a work. Yet should they not be “sieves and drainers for the use of luxurious readers,” but for the use of earnest inquirers, giving voice and being to their objections, as well as stimulus to their sympathies. But the critic must not be an infallible adviser to his reader. He must not tell him what books are not worth reading, or what must be thought of them when read, but what he read in them. Woe to that coterie where some critic sits despotic, entrenched behind the infallible “We.” Woe to that oracle who has infused such soft sleepiness, such a gentle dulness into his atmosphere, that -when he opes his lips no dog will bark. It is this attempt at dictatorship in the reviewers, and the indolent acquiescence of their readers, that has brought them into disrepute. With such fairness did they make out their statements, with such dignity did they utter their verdicts, that the poor reader grew all too submissive. He learned his lesson with such docility, that the greater part of what will be said at any public or private meeting can be foretold by any one who has read the leading periodical works for twenty years back. Scholars sneer at and would fain dispense with them altogether; and the public, grown lazy and helpless by this constant use of props and stays, can now scarce brace itself even to get through a magazine article, but reads in the daily paper laid beside the breakfast-plate a short notice of the last number of the long-established and popular review, and there upon passes its judgment and is content.

Then the partisan spirit of many of these journals has made it unsafe to rely upon them as guide-books and expurgatory indexes. They could not be content merely to stimulate and suggest thought, they have at last become powerless to supersede it.

From these causes and causes like these, the journals have lost much of their influence. There is a languid feeling about them, an inclination to suspect the justice of their verdicts, the value of their criticisms. But their golden age cannot be quite past. They afford too convenient a vehicle for the transmission of knowledge; they are too natural a feature of our time to have done all their work yet. Surely they may be redeemed from their abuses, they may be turned to their true uses. But how?

It were easy to say what they should not do. They should not have an object to carry or a cause to advocate, which obliges them either to reject all writings which wear the distinctive traits of individual life, or to file away what does not suit them, till the essay, made true to their design, is made false to the mind of the writer. An external consistency is thus produced, at the expense of all salient thought, all genuine emotion of life, in short, and all living influence. Their purpose may be of value, but by such means was no valuable purpose ever furthered long. There are those, who have with the best intention pursued this system of trimming and adaptation, and thought it well and best to “Deceive their country for their country’s good.”

But their country cannot long be so governed. It misses the pure, the full tone of truth; it perceives that the voice is modulated to coax, to persuade, and it turns from the judicious man of the world, calculating the effect to be produced by each of his smooth sentences, to some earnest voice which is uttering thoughts, crude, rash, ill-arranged it may be, but true to one human breast, and uttered in full faith, that the God of Truth will guide them aright.

And here, it seems to me, has been the greatest mistake in the conduct of these journals. A smooth monotony has been attained, an uniformity of tone, so that from the title of a journal you can infer the tenor of all its chapters. But nature is ever various, ever new, and so should be her daughters, art and literature. We do not want merely a polite response to what we thought before, but by the freshness of thought in other minds to have new thought awakened in our own. We do not want stores of information only, but to be roused to digest these into knowledge. Able and experienced men write for us, and we would know what they think, as they think it not for us but for themselves. We would live with them, rather than be taught by them how to live; we would catch the contagion of their mental activity, rather than have them direct us how to regulate our own. In books, in reviews, in the senate, in the pulpit, we wish to meet thinking men, not schoolmasters or pleaders. We wish that they should do full justice to their own view, but also that they should be frank with us, and, if now our superiors, treat us as if we might some time rise to be their equals. It is this true manliness, this firmness in his own position, and this power of appreciating the position of others, that alone can make the critic our companion and friend. We would converse with him, secure that he will tell us all his thought, and speak as man to man. But if he adapts his work to us, if he stifles what is distinctively his, if he shows himself either arrogant or mean, or, above all, if he wants faith in the healthy action of free thought, and the safety of pure motive, we will not talk with him, for we cannot confide in him. We will go to the critic who trusts Genius and trusts us, who knows that all good writing must be spontaneous, and who will write out the bill of fare for the public as he read it for himself,—

Forgetting vulgar rules, with spirit free To judge each author by his own intent, Nor think one standard for all minds is meant.

Such an one will not disturb us with personalities, with sectarian prejudices, or an undue vehemence in favour of petty plans or temporary objects. Neither will he disgust us by smooth obsequious flatteries, and an inexpressive, lifeless gentleness. He will be free and make free from the mechanical and distorting influences we hear complained of on every side. He will teach us to love wisely what we before loved well, for he knows the difference between censoriousness and discernment, infatuation and reverence; and while delighting in the genial melodies of Pan, can perceive, should Apollo bring his lyre into audience, that there may be strains more divine than those of his native groves.

Piece first published in The Dial , July 1840

About the Author:

Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850) was an American critic, journalist and women’s rights advocate.

Share this article

You may also like, why digital criticism is so very important.

The trouble with Theory, then, is not so much the terms in which interpretations are couched, but the fact that it privileges creating those accounts over the finding of patterns.

Mark Mordue: Curate. Content. Click.

Not that ‘the critic’ has ever been a greatly appreciated or understood figure. Some fat toad with a feather in his hat who thinks he is a modern-day Oscar Wilde.

The defeat of New Criticism: French invasion or Civil War?

Why criticism matters.

Editor's Picks

Orwell’s cuppa.

The tea should be strong. For a pot holding a quart, if you are going to fill it nearly to the brim, six heaped teaspoons would be about right...

‘Us’ by Legacy Russell

The thing about new blooms is that they tend to bleed— / Those petals birthed / hugging close / that come warmer weather are tricked into jumping away...

‘from An Explanation of America: Countries and Explanations’ by Robert Pinsky

Farah Abdessamad on François-René de Chateaubriand

I spent a good part of my childhood at home staring outside my bedroom window, following the trail of planes approaching the nearby Paris airport in the sky from my banlieue. I envied the passengers...

A Monk Surfing

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Feminism: An Essay

Feminism: An Essay

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on April 27, 2016 • ( 6 )

Feminism as a movement gained potential in the twentieth century, marking the culmination of two centuries’ struggle for cultural roles and socio-political rights — a struggle which first found its expression in Mary Wollstonecraft ‘s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). The movement gained increasing prominence across three phases/waves — the first wave (political), the second wave (cultural) and the third wave (academic). Incidentally Toril Moi also classifies the feminist movement into three phases — the female (biological), the feminist (political) and the feminine (cultural).

The first wave of feminism, in the 19th and 20th centuries, began in the US and the UK as a struggle for equality and property rights for women, by suffrage groups and activist organisations. These feminists fought against chattel marriages and for polit ical and economic equality. An important text of the first wave is Virginia Woolf ‘s A Room of One’s Own (1929), which asserted the importance of woman’s independence, and through the character Judith (Shakespeare’s fictional sister), explicated how the patriarchal society prevented women from realising their creative potential. Woolf also inaugurated the debate of language being gendered — an issue which was later dealt by Dale Spender who wrote Man Made Language (1981), Helene Cixous , who introduced ecriture feminine (in The Laugh of the Medusa ) and Julia Kristeva , who distinguished between the symbolic and the semiotic language.

The second wave of feminism in the 1960s and ’70s, was characterized by a critique of patriarchy in constructing the cultural identity of woman. Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex (1949) famously stated, “One is not born, but rather becomes a woman” – a statement that highlights the fact that women have always been defined as the “Other”, the lacking, the negative, on whom Freud attributed “ penis-envy .” A prominent motto of this phase, “The Personal is the political” was the result of the awareness .of the false distinction between women’s domestic and men’s public spheres. Transcending their domestic and personal spaces, women began to venture into the hitherto male dominated terrains of career and public life. Marking its entry into the academic realm, the presence of feminism was reflected in journals, publishing houses and academic disciplines.

Mary Ellmann ‘s Thinking about Women (1968), Kate Millett ‘s Sexual Politics (1969), Betty Friedan ‘s The Feminine Mystique (1963) and so on mark the major works of the phase. Millett’s work specifically depicts how western social institutions work as covert ways of manipulating power, and how this permeates into literature, philosophy etc. She undertakes a thorough critical understanding of the portrayal of women in the works of male authors like DH Lawrence, Norman Mailer, Henry Miller and Jean Genet.

In the third wave (post 1980), Feminism has been actively involved in academics with its interdisciplinary associations with Marxism , Psychoanalysis and Poststructuralism , dealing with issues such as language, writing, sexuality, representation etc. It also has associations with alternate sexualities, postcolonialism ( Linda Hutcheon and Spivak ) and Ecological Studies ( Vandana Shiva )

Elaine Showalter , in her “ Towards a Feminist Poetics ” introduces the concept of gynocriticism , a criticism of gynotexts, by women who are not passive consumers but active producers of meaning. The gynocritics construct a female framework for the analysis of women’s literature, and focus on female subjectivity, language and literary career. Patricia Spacks ‘ The Female Imagination , Showalter’s A Literature of their Own , Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar ‘s The Mad Woman in the Attic are major gynocritical texts.

The present day feminism in its diverse and various forms, such as liberal feminism, cultural/ radical feminism, black feminism/womanism, materialist/neo-marxist feminism, continues its struggle for a better world for women. Beyond literature and literary theory, Feminism also found radical expression in arts, painting ( Kiki Smith , Barbara Kruger ), architecture( Sophia Hayden the architect of Woman’s Building ) and sculpture (Kate Mllett’s Naked Lady).

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: A Literature of their Own , A Room of One's Own , Barbara Kruger , Betty Friedan , Dale Spender , ecriture feminine , Elaine Showalter , Feminism , Gynocriticism , Helene Cixous , http://bookzz.org/s/?q=Kate+Millett&yearFrom=&yearTo=&language=&extension=&t=0 , Judith Shakespeare , Julia Kristeva , Kate Millett , Kiki Smith , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Man Made Language , Mary Ellmann , Mary Wollstonecraft , Patricia Spacks , Sandra Gilbert , Simone de Beauvoir , Sophia Hayden , Susan Gubar , The Female Imagination , The Feminine Mystique , The Laugh of the Medusa , The Mad Woman in the Attic , The Second Sex , Toril Moi , Towards a Feminist Poetics , Vandana Shiva , Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Related Articles

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s Contribution to Feminism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- The Influence of Poststructuralism on Feminism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Sigmund Freud and the Trauma Theory – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Gender and Transgender Criticism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Second Wave Feminism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Criticism" seeks to lay down rules of good taste in poetry criticism, and in poetry itself. Structured as an essay in rhyming verse, it offers advice to the aspiring critic while satirizing amateurish criticism and poetry. The famous passage beginning "A little learning is a dangerous thing" advises would-be critics to learn their field in depth, warning that the ...

Pope primarily used the heroic couplet, and his lines are immensely quotable; from "An Essay on Criticism" come famous phrases such as "To err is human; to forgive, divine," "A little learning is a dang'rous thing," and "For fools rush in where angels fear to tread.". After 1718 Pope lived on his five-acre property at ...

An Essay on Criticism (1711) was Pope's first independent work, published anonymously through an obscure bookseller [12-13]. Its implicit claim to authority is not based on a lifetime's creative work or a prestigious commission but, riskily, on the skill and argument of the poem alone. It offers a sort of master-class not only in doing….

An Essay on Criticism is one of the first major poems written by the English writer Alexander Pope (1688-1744), published in 1711. It is the source of the famous quotations "To err is human; to forgive, divine", "A little learning is a dang'rous thing" (frequently misquoted as "A little knowledge is a dang'rous thing"), and "Fools rush in ...

An Essay on Criticism, didactic poem in heroic couplets by Alexander Pope, first published anonymously in 1711 when the author was 22 years old.Although inspired by Horace's Ars poetica, this work of literary criticism borrowed from the writers of the Augustan Age.In it Pope set out poetic rules, a Neoclassical compendium of maxims, with a combination of ambitious argument and great ...

Plot Summary. "An Essay on Criticism" (1709) is a work of both poetry and criticism. Pope attempts in this long, three-part poem, which he wrote when he was twenty-three, to examine ...

An Essay on Criticism is considered part of the didactic poetry genre, aiming to instruct and enlighten readers about the dos and don'ts of criticism and poetry. In this poem, Pope discusses the rules of literary criticism and the qualities of a good critic, advocating for rules based on a broad understanding of nature and humanity.

Analysis. Last Updated September 5, 2023. Alexander Pope 's long three-part poem "An Essay on Criticism" is largely influenced by ancient poets, classical models of art, and Pope's own ...

Books. An Essay on Criticism: With Introductory and Explanatory Notes. Alexander Pope. The Floating Press, Feb 1, 2010 - Poetry - 57 pages. Despite its somewhat dry title, this text is not a musty prose dissection of literary criticism. Instead, the piece takes the shape of a long poem in which Pope, at the very peak of his powers, takes ...

An Essay on Criticism: Part 1. Si quid novisti rectius istis, Candidus imperti; si non, his utere mecum. [If you have come to know any precept more correct than these, share it with me, brilliant one; if not, use these with me] (Horace, Epistle I.6.67) 'Tis hard to say, if greater want of skill. Appear in writing or in judging ill;

About the Title. "An Essay on Criticism" is in the form of a rhyming poem, but its content is akin to a nonfiction essay detailing and supporting Pope's arguments about writers and critics. Alexander Pope wrote and translated many different types of literature, using poetic forms to express diverse content.

An Essay on Criticism, frontispiece. Published in 1711, Alexander Pope 's poem An Essay on Criticism is a series of finely-wrought epigrams on the art of writing and one of the most quoted poems ...

A poem's central idea, often developed into an extended metaphor, is known as a conceit. Unlocking the first couplet should provide you the key to Pope's conceit in An Essay on Criticism. Pope begins with a warning that: A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring: The Pierian Spring is an important ...

"An Essay on Criticism" can be understood as a nonfiction persuasive essay that rhymes. Other poems such as "The Rape of the Lock" function as rhyming short stories. Pope's English translation of Homer's works is revolutionary in its use of rhyming verse to recreate the experience of hearing them as poetry as the ancient Greeks had.

An Essay on Criticism: Part 2. By Alexander Pope. Of all the causes which conspire to blind. Man's erring judgment, and misguide the mind, What the weak head with strongest bias rules, Is pride, the never-failing vice of fools. Whatever Nature has in worth denied, She gives in large recruits of needful pride; For as in bodies, thus in souls, we ...

Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind, But more advanc'd, behold with strange surprise New, distant scenes of endless science rise! As the title of Pope's poem, 'An Essay on Criticism', makes clear, Pope is specifically advising critics - especially literary critics - when he opines, ...

The essay on criticism gives you an insight into the pros and cons of the criticism. Criticism is expressing the disagreement for something or someone that is generally based on perceived faults, beliefs, and mistakes. So, the main point here is whether to consider criticism as good or bad. Also, if we go by the meaning of the word criticism ...

According to Pope's An Essay on Criticism, how should one approach learning? Explain the second ten lines of part 1 in Alexander Pope's "Essay On Criticism". What ideas about human nature underlie ...

Short Essay on Criticism for Students. 'Criticism is a crucial part of the creative field. It is used to judge any situation, piece of art, person, movie, work, etc. Criticism can be better understood as two sides of coins. Just as a coin has two sides, criticism also has two sides. It could be constructive or destructive.

A Short Essay on Critics [Sarah] Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) The Dial: Volume I, July 1840-April 1841. An essay on Criticism were a serious matter; for, though this age be emphatically critical, the writer would still find it necessary to investigate the laws of criticism as a science, to settle its conditions as an art. ...

Ecocriticism is an intentionally broad approach that is known by a number of other designations, including "green (cultural) studies", "ecopoetics", and "environmental literary criticism.". Western thought has often held a more or less utilitarian attitude to nature —nature is for serving human needs. However, after the eighteenth ...

A Short Essay on Critics May 6, 2013. Margaret Fuller. by Margaret Fuller. If an essay on Criticism were a serious matter; for, though this age be emphatically critical, the writer would still find it necessary to investigate the laws of criticism as a science, to settle its conditions as an art. Essays, entitled critical, are epistles ...

Feminism: An Essay By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on April 27, 2016 • ( 6). Feminism as a movement gained potential in the twentieth century, marking the culmination of two centuries' struggle for cultural roles and socio-political rights — a struggle which first found its expression in Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). The movement gained increasing prominence ...