Science Essay

Learn How to Write an A+ Science Essay

11 min read

People also read

150+ Engaging Science Essay Topics To Hook Your Readers

Read 8 Impressive Science Essay Examples And Get Inspired

Science Fiction Essay: Examples & Easy Steps Guide

Essay About Science and Technology| Tips & Examples

Essay About Science in Everyday Life - Samples & Writing Tips

Check Out 5 Impressive Essay About Science Fair Examples

Did you ever imagine that essay writing was just for students in the Humanities? Well, think again!

For science students, tackling a science essay might seem challenging, as it not only demands a deep understanding of the subject but also strong writing skills.

However, fret not because we've got your back!

With the right steps and tips, you can write an engaging and informative science essay easily!

This blog will take you through all the important steps of writing a science essay, from choosing a topic to presenting the final work.

So, let's get into it!

- 1. What Is a Science Essay?

- 2. How To Write a Science Essay?

- 3. How to Structure a Science Essay?

- 4. Science Essay Examples

- 5. How to Choose the Right Science Essay Topic

- 6. Science Essay Topics

- 7. Science Essay Writing Tips

What Is a Science Essay?

A science essay is an academic paper focusing on a scientific topic from physics, chemistry, biology, or any other scientific field.

Science essays are mostly expository. That is, they require you to explain your chosen topic in detail. However, they can also be descriptive and exploratory.

A descriptive science essay aims to describe a certain scientific phenomenon according to established knowledge.

On the other hand, the exploratory science essay requires you to go beyond the current theories and explore new interpretations.

So before you set out to write your essay, always check out the instructions given by your instructor. Whether a science essay is expository or exploratory must be clear from the start. Or, if you face any difficulty, you can take help from a science essay writer as well.

Moreover, check out this video to understand scientific writing in detail.

Now that you know what it is, let's look at the steps you need to take to write a science essay.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

How To Write a Science Essay?

Writing a science essay is not as complex as it may seem. All you need to do is follow the right steps to create an impressive piece of work that meets the assigned criteria.

Here's what you need to do:

Choose Your Topic

A good topic forms the foundation for an engaging and well-written essay. Therefore, you should ensure that you pick something interesting or relevant to your field of study.

To choose a good topic, you can brainstorm ideas relating to the subject matter. You may also find inspiration from other science essays or articles about the same topic.

Conduct Research

Once you have chosen your topic, start researching it thoroughly to develop a strong argument or discussion in your essay.

Make sure you use reliable sources and cite them properly . You should also make notes while conducting your research so that you can reference them easily when writing the essay. Or, you can get expert assistance from an essay writing service to manage your citations.

Create an Outline

A good essay outline helps to organize the ideas in your paper. It serves as a guide throughout the writing process and ensures you don’t miss out on important points.

An outline makes it easier to write a well-structured paper that flows logically. It should be detailed enough to guide you through the entire writing process.

However, your outline should be flexible, and it's sometimes better to change it along the way to improve your structure.

Start Writing

Once you have a good outline, start writing the essay by following your plan.

The first step in writing any essay is to draft it. This means putting your thoughts down on paper in a rough form without worrying about grammar or spelling mistakes.

So begin your essay by introducing the topic, then carefully explain it using evidence and examples to support your argument.

Don't worry if your first draft isn't perfect - it's just the starting point!

Proofread & Edit

After finishing your first draft, take time to proofread and edit it for grammar and spelling mistakes.

Proofreading is the process of checking for grammatical mistakes. It should be done after you have finished writing your essay.

Editing, on the other hand, involves reviewing the structure and organization of your essay and its content. It should be done before you submit your final work.

Both proofreading and editing are essential for producing a high-quality essay. Make sure to give yourself enough time to do them properly!

After revising the essay, you should format it according to the guidelines given by your instructor. This could involve using a specific font size, page margins, or citation style.

Most science essays are written in Times New Roman font with 12-point size and double spacing. The margins should be 1 inch on all sides, and the text should be justified.

In addition, you must cite your sources properly using a recognized citation style such as APA , Chicago , or Harvard . Make sure to follow the guidelines closely so that your essay looks professional.

Following these steps will help you create an informative and well-structured science essay that meets the given criteria.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

How to Structure a Science Essay?

A basic science essay structure includes an introduction, body, and conclusion.

Let's look at each of these briefly.

- Introduction

Your essay introduction should introduce your topic and provide a brief overview of what you will discuss in the essay. It should also state your thesis or main argument.

For instance, a thesis statement for a science essay could be,

"The human body is capable of incredible feats, as evidenced by the many athletes who have competed in the Olympic games."

The body of your essay will contain the bulk of your argument or discussion. It should be divided into paragraphs, each discussing a different point.

For instance, imagine you were writing about sports and the human body.

Your first paragraph can discuss the physical capabilities of the human body.

The second paragraph may be about the physical benefits of competing in sports.

Similarly, in the third paragraph, you can present one or two case studies of specific athletes to support your point.

Once you have explained all your points in the body, it’s time to conclude the essay.

Your essay conclusion should summarize the main points of your essay and leave the reader with a sense of closure.

In the conclusion, you reiterate your thesis and sum up your arguments. You can also suggest implications or potential applications of the ideas discussed in the essay.

By following this structure, you will create a well-organized essay.

Check out a few example essays to see this structure in practice.

Science Essay Examples

A great way to get inspired when writing a science essay is to look at other examples of successful essays written by others.

Here are some examples that will give you an idea of how to write your essay.

Science Essay About Genetics - Science Essay Example

Environmental Science Essay Example | PDF Sample

The Science of Nanotechnology

Science, Non-Science, and Pseudo-Science

The Science Of Science Education

Science in our Daily Lives

Short Science Essay Example

Let’s take a look at a short science essay:

Want to read more essay examples? Here, you can find more science essay examples to learn from.

How to Choose the Right Science Essay Topic

Choosing the right science essay topic is a critical first step in crafting a compelling and engaging essay. Here's a concise guide on how to make this decision wisely:

- Consider Your Interests: Start by reflecting on your personal interests within the realm of science. Selecting a topic that genuinely fascinates you will make the research and writing process more enjoyable and motivated.

- Relevance to the Course: Ensure that your chosen topic aligns with your course or assignment requirements. Read the assignment guidelines carefully to understand the scope and focus expected by your instructor.

- Current Trends and Issues: Stay updated with the latest scientific developments and trends. Opting for a topic that addresses contemporary issues not only makes your essay relevant but also demonstrates your awareness of current events in the field.

- Narrow Down the Scope: Science is vast, so narrow your topic to a manageable scope. Instead of a broad subject like "Climate Change," consider a more specific angle like "The Impact of Melting Arctic Ice on Global Sea Levels."

- Available Resources: Ensure that there are sufficient credible sources and research materials available for your chosen topic. A lack of resources can hinder your research efforts.

- Discuss with Your Instructor: If you're uncertain about your topic choice, don't hesitate to consult your instructor or professor. They can provide valuable guidance and may even suggest specific topics based on your academic goals.

Science Essay Topics

Choosing an appropriate topic for a science essay is one of the first steps in writing a successful paper.

Here are a few science essay topics to get you started:

- How space exploration affects our daily lives?

- How has technology changed our understanding of medicine?

- Are there ethical considerations to consider when conducting scientific research?

- How does climate change affect the biodiversity of different parts of the world?

- How can artificial intelligence be used in medicine?

- What impact have vaccines had on global health?

- What is the future of renewable energy?

- How do we ensure that genetically modified organisms are safe for humans and the environment?

- The influence of social media on human behavior: A social science perspective

- What are the potential risks and benefits of stem cell therapy?

Important science topics can cover anything from space exploration to chemistry and biology. So you can choose any topic according to your interests!

Need more topics? We have gathered 100+ science essay topics to help you find a great topic!

Continue reading to find some tips to help you write a successful science essay.

Science Essay Writing Tips

Once you have chosen a topic and looked at examples, it's time to start writing the science essay.

Here are some key tips for a successful essay:

- Research thoroughly

Make sure you do extensive research before you begin writing your paper. This will ensure that the facts and figures you include are accurate and supported by reliable sources.

- Use clear language

Avoid using jargon or overly technical language when writing your essay. Plain language is easier to understand and more engaging for readers.

- Referencing

Always provide references for any information you include in your essay. This will demonstrate that you acknowledge other people's work and show that the evidence you use is credible.

Make sure to follow the basic structure of an essay and organize your thoughts into clear sections. This will improve the flow and make your essay easier to read.

- Ask someone to proofread

It’s also a good idea to get someone else to proofread your work as they may spot mistakes that you have missed.

These few tips will help ensure that your science essay is well-written and informative!

You've learned the steps to writing a successful science essay and looked at some examples and topics to get you started.

Make sure you thoroughly research, use clear language, structure your thoughts, and proofread your essay. With these tips, you’re sure to write a great science essay!

Do you still need expert help writing a science essay? Our science essay writing service is here to help. With our team of professional writers, you can rest assured that your essay will be written to the highest standards.

Contact our essay service now to get started!

Also, do not forget to try our essay typer tool for quick and cost-free aid with your essays!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Betty is a freelance writer and researcher. She has a Masters in literature and enjoys providing writing services to her clients. Betty is an avid reader and loves learning new things. She has provided writing services to clients from all academic levels and related academic fields.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Browse Course Material

Course info.

- Karen Boiko

Departments

- Comparative Media Studies/Writing

As Taught In

- Academic Writing

- Creative Writing

- Nonfiction Prose

Learning Resource Types

The science essay, course description.

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

notifications_active To return to the old version of the website Click here

Mastering the Art of Crafting an A+ Science Essay

Mastering science essay writing: a comprehensive guide for students, what is a science essay.

Science essays serve as a vital bridge between the realm of scientific inquiry and the wider world. They are a medium through which students can articulate their understanding of scientific concepts, theories, experiments, and findings. But what exactly constitutes a science essay?

At its core, a science essay is an academic piece of writing that explores a scientific topic or issue in depth. Unlike traditional essays, which may focus on literature, history, or philosophy, science essays delve into the complexities of the natural world and the scientific method used to understand it.

These essays come in various forms, each with its unique purpose and structure. They may take the shape of analytical essays, where students critically evaluate existing scientific research or theories. Alternatively, they could be argumentative essays, where students take a stance on a scientific controversy or propose a solution to a scientific problem. Additionally, science essays may also include reports of scientific experiments, observations, or fieldwork, presenting findings and drawing conclusions based on empirical evidence.

Regardless of the specific type, all science essays share common characteristics. They are evidence-based, relying on scientific literature, data, and experimentation to support claims and arguments. They are also written in a clear, concise, and precise manner, using language that is accessible to both scientific experts and non-experts alike. Furthermore, science essays adhere to academic conventions, including proper citation of sources and adherence to formatting guidelines such as APA, MLA, or Chicago style.

In essence, a science essay is not merely a means of demonstrating knowledge; it is a tool for engaging with the scientific community, contributing to the advancement of knowledge, and fostering critical thinking skills. By mastering the art of writing science essays, students can develop their ability to communicate complex scientific ideas effectively, paving the way for future success in their academic and professional endeavors.

Structuring Your Science Essay

When it comes to writing a science essay, the structure plays a pivotal role in ensuring clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness. By following a well-organized structure, you can effectively convey your ideas, present your arguments, and engage your reader from start to finish. Here’s how to structure your science essay for maximum impact:

Introduction: Hooking Your Reader and Presenting Your Thesis

The introduction serves as the gateway to your essay, setting the stage for what is to come and capturing the reader’s attention from the outset. To craft an effective introduction:

Hook Your Reader: Begin with a compelling hook or attention-grabbing anecdote that piques the reader’s curiosity and draws them into the topic. This could be a surprising fact, a thought-provoking question, or a relevant quote.

Provide Background Information: Offer brief background information on the topic to provide context and establish the significance of the subject matter. Highlight any relevant scientific theories, concepts, or research findings that will be discussed in the essay.

Present Your Thesis Statement: Clearly state your thesis statement, which outlines the main argument or purpose of your essay. Your thesis should be concise, specific, and debatable, providing a roadmap for the reader to follow as they navigate through your essay.

By crafting a compelling introduction, you lay the foundation for a well-structured and engaging science essay that captivates your reader’s interest from the very beginning.

Body Paragraphs: Organizing Your Arguments and Supporting Evidence

The body paragraphs form the heart of your science essay, where you develop your arguments, present supporting evidence, and delve into the complexities of your topic. To effectively structure your body paragraphs:

Focus on One Main Idea per Paragraph: Each body paragraph should revolve around a single main idea or argument that supports your thesis statement. Begin with a topic sentence that introduces the main point of the paragraph and provides a transition from the previous paragraph.

Provide Supporting Evidence: Support your main idea with relevant evidence, examples, or data drawn from your research. This could include scientific studies, experiments, observations, or scholarly sources that bolster your argument and lend credibility to your claims.

Offer Analysis and Interpretation: Analyze the evidence presented and explain how it supports your argument or contributes to your overall thesis. Offer insightful interpretations, draw connections between different pieces of evidence, and demonstrate your understanding of the subject matter.

Ensure Smooth Transitions: Use transition words and phrases to guide the reader smoothly from one paragraph to the next. This helps maintain coherence and clarity throughout your essay, allowing the reader to follow your line of reasoning effortlessly.

By organizing your body paragraphs in a logical and coherent manner, you can effectively convey your arguments, present compelling evidence, and persuade your reader of the validity of your claims.

Conclusion: Reinforcing Your Thesis and Leaving a Lasting Impression

The conclusion serves as the final opportunity to reinforce your thesis, summarize your key points, and leave a lasting impression on your reader. To craft an effective conclusion:

Restate Your Thesis: Begin by restating your thesis statement in slightly different words, emphasizing the main argument or central claim of your essay. This reaffirms the significance of your topic and reminds the reader of the purpose of your essay.

Summarize Your Key Points: Provide a brief summary of the main points discussed in your essay, highlighting the most important findings, arguments, or insights presented. This helps reinforce your thesis and reinforces the main takeaways for the reader.

Offer Insights or Recommendations: Reflect on the implications of your research and offer insights, recommendations, or suggestions for further study. Consider the broader significance of your findings and how they contribute to the existing body of scientific knowledge.

End with a Strong Closing Statement: Conclude your essay with a memorable closing statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. This could be a thought-provoking question, a call to action, or a powerful reflection that ties back to the introductory hook.

By crafting a compelling conclusion, you can leave your reader with a sense of closure, reinforce the significance of your thesis, and leave them with a lasting impression that resonates beyond the pages of your essay.

In summary, structuring your science essay with a captivating introduction, well-organized body paragraphs, and a compelling conclusion is essential for effectively communicating your ideas, engaging your reader, and making a persuasive argument. By following these guidelines, you can craft a structured and coherent essay that showcases your understanding of the subject matter and leaves a lasting impact on your audience.

Incorporating Scientific Evidence

In the realm of science essays, the strength of your argument hinges on the quality and relevance of the evidence you present. Scientific evidence serves as the backbone of your essay, providing support for your claims, validating your arguments, and bolstering your credibility as a writer. Here’s how to effectively incorporate scientific evidence into your essay:

Choosing the Right Evidence to Strengthen Your Argument

- Relevance is Key: Select evidence that directly supports your thesis statement and aligns with the main arguments you’re making in your essay. Avoid tangential or unrelated evidence that may detract from the focus of your essay.

- Prioritize Credible Sources: Seek out evidence from reputable scientific sources such as peer-reviewed journals, academic textbooks, and reliable websites. Pay attention to the expertise and authority of the authors, as well as the publication venue’s reputation within the scientific community.

- Consider the Currency of the Evidence: Choose recent and up-to-date evidence whenever possible, particularly in rapidly evolving fields of science. While seminal studies may hold historical significance, newer research often reflects the current state of knowledge and understanding.

- Diversify Your Sources: Draw evidence from a variety of sources to provide a comprehensive and balanced perspective on the topic. Incorporate a mix of primary research studies, meta-analyses, expert opinions, and statistical data to strengthen your argument.

- Evaluate the Strength of the Evidence: Assess the quality and reliability of the evidence by examining factors such as sample size, methodology, statistical significance, and potential biases. Strong evidence is characterized by robust study designs, rigorous data analysis, and consistent findings.

Integrating Data, Experiments, and Case Studies Effectively

- Provide Context: Introduce each piece of evidence with context to help the reader understand its significance and relevance to your argument. Explain the background of the study, the research question addressed, and the methodology employed to collect and analyze data.

- Present Data Clearly: Use tables, graphs, charts, and diagrams to present quantitative data in a clear and visually appealing manner. Ensure that the data are properly labeled, annotated, and explained to facilitate interpretation by the reader.

- Analyze and Interpret Findings: Analyze the findings of the studies or experiments you’re citing and interpret their implications in relation to your argument. Discuss how the evidence supports or challenges existing theories, hypotheses, or prevailing viewpoints in the field.

- Provide Examples and Case Studies: Illustrate your arguments with real-world examples, case studies, or anecdotes that demonstrate the practical applications or consequences of the scientific concepts under discussion. Case studies can offer concrete evidence of theoretical principles in action and lend credibility to your argument.

- Draw Connections Between Evidence: Connect different pieces of evidence together to build a cohesive and compelling narrative. Identify patterns, trends, or relationships among the evidence presented and use them to strengthen your overall argument.

By carefully selecting and integrating scientific evidence into your essay, you can substantiate your claims, enhance the credibility of your arguments, and engage your reader on a deeper level. Remember to prioritize relevance, credibility, and clarity when incorporating evidence, and to provide sufficient context and analysis to help your reader understand its significance within the broader context of your essay.

The Art of Writing Clear and Concise

In the realm of science essays, clarity and conciseness are paramount. As a writer, your goal is to communicate complex scientific ideas in a way that is accessible to your audience while maintaining accuracy and precision. Here are two key principles to master the art of clear and concise writing in your science essays:

Avoiding Jargon: Communicating Complex Ideas Simply

- Know Your Audience: Tailor your language to your intended audience, whether they are fellow scientists, students, or general readers with varying levels of scientific expertise. Avoid unnecessary technical jargon that may alienate or confuse your readers.

- Define Key Terms: When introducing technical terms or specialized terminology, provide clear definitions to ensure that your readers understand the concepts you’re discussing. Define terms in a way that is concise and accessible, using language that is familiar to your audience.

- Use Analogies and Examples: Simplify complex scientific concepts by using analogies, metaphors, or real-world examples that resonate with your readers’ experiences. Analogies can help bridge the gap between unfamiliar scientific concepts and everyday phenomena, making them easier to grasp.

- Clarify Ambiguous Language: Avoid ambiguous or vague language that may lead to misunderstandings. Be precise in your choice of words and phrases, and strive for clarity in your explanations. If a term or concept has multiple interpretations, clarify your meaning to avoid confusion.

- Test for Comprehension: Put yourself in your readers’ shoes and consider whether your writing is clear and understandable to someone with limited background knowledge in the subject. Ask for feedback from peers or colleagues to ensure that your writing effectively communicates your ideas.

Precision in Language: Conveying Scientific Concepts with Accuracy

- Use Specific Language: Choose words and phrases that accurately convey your intended meaning and avoid vague or imprecise language. Be specific in your descriptions, measurements, and observations to ensure clarity and accuracy.

- Define Technical Terms: Define technical terms and scientific terminology clearly and concisely to avoid ambiguity or misunderstanding. Provide definitions, explanations, or contextual clues to help readers understand the meaning of specialized terms within the context of your essay.

- Be Mindful of Nuance: Pay attention to nuances in language and terminology, especially when discussing complex scientific concepts or theories. Use language with care to accurately convey subtle distinctions or variations in meaning.

- Avoid Overly Technical Language: While precision is important, be cautious not to overwhelm your readers with overly technical language or excessive detail. Strike a balance between precision and accessibility, using language that is appropriate for your audience and the level of expertise expected.

- Edit for Clarity and Accuracy: Review your writing carefully to ensure that your language is precise, accurate, and free from errors. Clarify any ambiguities, refine your explanations, and eliminate unnecessary or redundant language to enhance clarity and conciseness.

By adhering to these principles of clear and concise writing, you can effectively communicate complex scientific ideas with precision, accuracy, and accessibility in your science essays. Strive to make your writing engaging and understandable to your audience, while maintaining the integrity and rigor of scientific communication.

Editing and Proofreading

Crafting a successful science essay doesn’t end with the completion of the first draft. In fact, the revision process is where the magic truly happens. Editing and proofreading your essay is essential to ensure clarity, coherence, and accuracy. Let’s explore the importance of revision and common mistakes to watch out for:

The Importance of Revision: Polishing Your Science Essay for Excellence

- Enhancing Clarity and Coherence: Revision allows you to refine your ideas, clarify your arguments, and ensure that your essay flows smoothly from start to finish. By reviewing and restructuring your sentences and paragraphs, you can improve the overall coherence and readability of your essay.

- Strengthening Your Argument: During the revision process, you have the opportunity to evaluate the strength of your argument and identify any weaknesses or gaps in your reasoning. You can strengthen your argument by providing additional evidence, refining your analysis, and addressing counterarguments effectively.

- Checking for Accuracy and Precision: Revision also involves verifying the accuracy of your scientific information, ensuring that all facts, data, and citations are correct and properly referenced. Pay close attention to details such as units of measurement, statistical analysis, and scientific terminology to maintain precision in your writing.

- Polishing Your Language: Use the revision process to refine your language and style, eliminating unnecessary words, phrases, and repetitions. Aim for clarity, conciseness, and precision in your writing, choosing words and expressions that effectively convey your ideas to your audience.

- Finalizing Formatting and Citation: Before submitting your essay, ensure that it adheres to the required formatting guidelines and citation style. Check the formatting of your title page, headings, citations, and reference list to ensure consistency and accuracy.

Common Mistakes to Watch Out For and How to Correct Them

- Grammatical Errors: Watch out for grammatical errors such as subject-verb agreement, tense consistency, and punctuation mistakes. Use grammar-checking tools or seek feedback from peers to identify and correct errors in your writing.

- Spelling and Typographical Errors: Proofread your essay carefully to catch any spelling mistakes, typos, or misspelled words. Pay attention to commonly confused words and homophones that may not be flagged by spell-checking tools.

- Inconsistent Formatting: Check for consistency in formatting throughout your essay, including headings, font style and size, margins, and spacing. Ensure that your essay follows the required formatting guidelines specified by your instructor or institution.

- Weak Transitions: Review your essay for weak or abrupt transitions between paragraphs and sections. Use transition words and phrases to guide the reader smoothly from one idea to the next, creating a cohesive and logical flow of information.

- Plagiarism: Avoid plagiarism by properly citing all sources used in your essay and giving credit to the original authors. Use quotation marks for direct quotes and paraphrase information in your own words while providing a citation to acknowledge the source.

By diligently editing and proofreading your science essay, you can polish your writing to achieve excellence, ensuring clarity, accuracy, and coherence. Take the time to review your essay thoroughly, addressing common mistakes and refining your arguments to create a polished and professional final product.

Citations and References

In the realm of academia, citations and references play a crucial role in acknowledging the contributions of other scholars, providing evidence to support your arguments, and maintaining academic integrity. Understanding different citation styles and properly citing sources are essential skills for every science essay writer. Let’s delve into the specifics:

Understanding Different Citation Styles: APA, MLA, and Chicago

APA (American Psychological Association): APA style is commonly used in the social sciences and sciences, including psychology, sociology, and biology. It features in-text citations with the author’s last name and year of publication, along with a corresponding reference list at the end of the document.

MLA (Modern Language Association): MLA style is typically used in the humanities, such as literature, languages, and cultural studies. It employs in-text citations with the author’s last name and page number, as well as a Works Cited page listing all sources cited in the essay.

Chicago Style: Chicago style encompasses two main citation formats: notes and bibliography (often used in humanities) and author-date (similar to APA, commonly used in social sciences and sciences). Chicago style offers flexibility in citation formats, allowing for either footnotes or in-text citations, along with a bibliography or reference list.

Properly Citing Sources to Avoid Plagiarism and Maintain Academic Integrity

- In-Text Citations: Whenever you use information, ideas, or direct quotes from a source, provide an in-text citation to acknowledge the source’s author and publication year. This allows readers to locate the original source if they wish to explore further.

- Quotation Marks for Direct Quotes: When directly quoting a source, enclose the quoted text in quotation marks and provide an in-text citation indicating the source’s author, publication year, and page number (if applicable).

- Reference List or Works Cited Page: Compile a comprehensive list of all sources cited in your essay and include it at the end of your document. Arrange the sources alphabetically by the author’s last name (or title if no author is provided), following the formatting guidelines of your chosen citation style.

- Provide Sufficient Information: Ensure that your citations include all necessary information for readers to identify and locate the sources cited. This typically includes the author’s name, title of the work, publication date, publisher, and relevant page numbers.

- Paraphrase and Summarize Ethically: When paraphrasing or summarizing information from a source, rephrase the content in your own words while still acknowledging the original source through an in-text citation. Avoid copying verbatim text without proper attribution, as this constitutes plagiarism.

- Be Consistent: Maintain consistency in your citation style throughout your essay, adhering to the formatting guidelines prescribed by your instructor or institution. Consistent citation practices enhance the readability and professionalism of your work.

By understanding the nuances of different citation styles and adhering to proper citation practices, you can avoid plagiarism, give credit to the original authors, and uphold the principles of academic integrity in your science essays. Remember to consult relevant style guides and resources for specific citation formatting instructions, and always double-check your citations to ensure accuracy and completeness.

Going Above and Beyond: Tips for Excellence

To truly excel in crafting your science essay, consider going beyond the basics and incorporating additional elements that enhance clarity, engagement, and effectiveness. Here are two key tips for taking your essay to the next level:

Incorporating Visuals: Using Diagrams, Graphs, and Images to Enhance Understanding

- Enhance Comprehension: Visual aids such as diagrams, graphs, charts, and images can effectively illustrate complex scientific concepts and relationships, making them easier for readers to understand. Use visuals to complement your written explanations and provide visual representations of data, processes, or structures discussed in your essay.

- Choose Appropriate Visuals: Select visuals that are relevant, clear, and visually appealing, ensuring that they enhance rather than detract from your essay. Consider the type of information you’re presenting and choose the most appropriate format, whether it’s a line graph to illustrate trends, a schematic diagram to depict a process, or a photograph to showcase a specimen or experiment.

- Label and Caption Effectively: Provide clear labels, titles, and captions for your visuals to guide readers in interpreting the information presented. Include relevant annotations, explanations, and units of measurement to ensure that readers understand the significance of the visual and how it relates to the content of your essay.

- Integrate Seamlessly: Integrate visuals seamlessly into your essay, placing them strategically within the text where they enhance understanding and reinforce key points. Refer to visuals in your writing to draw attention to specific elements and provide context for their interpretation.

- Ensure Accessibility: Consider the accessibility of your visuals for all readers, including those with visual impairments or disabilities. Provide alternative text descriptions for images and ensure that graphs and diagrams are compatible with screen readers and assistive technologies.

Seeking Feedback: Utilizing Peer Review and Instructor Feedback to Improve Your Essay

- Engage in Peer Review: Share your essay with peers or classmates for feedback and constructive criticism. Peer review allows you to gain fresh perspectives on your writing, identify areas for improvement, and receive valuable insights from others who may offer different viewpoints or expertise.

- Consider Instructor Feedback: Take advantage of feedback provided by your instructor or academic supervisor to identify strengths and weaknesses in your essay. Pay attention to specific suggestions for improvement and use them as guidance for revising and refining your work.

- Be Open to Critique: Approach feedback with an open mind and a willingness to learn and grow as a writer. Acknowledge areas where your essay may fall short and consider how you can address any shortcomings to enhance the quality and effectiveness of your writing.

- Iterate and Revise: Use feedback as a springboard for revision, iterating on your essay to incorporate suggestions, clarify points, and strengthen your argument. Take the time to revise and refine your essay based on feedback received, aiming for continuous improvement with each draft.

- Seek Additional Resources: In addition to peer and instructor feedback, seek out additional resources and support to further enhance your essay-writing skills. Consider attending writing workshops, consulting writing guides and style manuals, or seeking assistance from academic support services to refine your craft.

By incorporating visuals effectively and seeking feedback from peers and instructors, you can elevate your science essay to new heights of excellence. Embrace opportunities for collaboration, learning, and improvement, and strive to continually refine your writing skills to produce essays that are engaging, informative, and impactful.

Writing an A+ science essay requires dedication, attention to detail, and a commitment to excellence. Throughout this guide, we’ve explored the key steps and strategies for crafting a stellar science essay that engages readers, communicates complex ideas effectively, and upholds academic standards. As you conclude your journey through this guide, let’s recapitulate the essential steps and empower you to tackle future essay assignments with confidence:

Recapitulating the Key Steps to Writing an A+ Science Essay

- Understand the Assignment: Begin by thoroughly understanding the essay prompt, identifying key requirements, and clarifying expectations with your instructor.

- Research Thoroughly: Conduct comprehensive research using credible sources to gather relevant information and evidence to support your arguments.

- Craft a Strong Thesis Statement: Develop a clear and concise thesis statement that articulates your main argument and sets the direction for your essay.

- Structure Your Essay Effectively: Organize your essay with a compelling introduction, well-structured body paragraphs, and a convincing conclusion that reinforces your thesis.

- Incorporate Scientific Evidence: Choose appropriate evidence, such as data, experiments, and case studies, to substantiate your arguments and strengthen your essay.

- Write Clearly and Concisely: Communicate complex scientific ideas in simple, accessible language, avoiding jargon and ensuring precision in your writing.

- Edit and Proofread Diligently: Revise your essay carefully to polish your writing, correct errors, and ensure coherence, clarity, and accuracy.

- Cite Sources Properly: Follow the guidelines of your chosen citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago) to cite sources accurately and avoid plagiarism.

- Incorporate Visuals and Seek Feedback: Enhance your essay with visuals such as diagrams and graphs, and seek feedback from peers and instructors to refine your work further.

Empowering Yourself to Tackle Future Essay Assignments with Confidence

Armed with the knowledge, skills, and strategies outlined in this guide, you are well-equipped to tackle future science essay assignments with confidence. Approach each essay as an opportunity for growth and learning, embracing the challenges and seeking opportunities to refine your writing craft. Remember to:

- Plan and organize your time effectively to allow ample time for research, writing, and revision.

- Embrace feedback as a valuable tool for improvement, and actively seek out opportunities for peer review and instructor guidance.

- Continuously expand your knowledge and expertise in your field of study, staying informed of the latest developments and trends.

- Stay true to your unique voice and perspective as a writer, and strive to communicate your ideas with clarity, passion, and conviction.

By embodying these principles and approaches, you can confidently navigate the intricacies of science essay writing, producing essays that are not only academically rigorous but also engaging, insightful, and impactful. As you embark on your journey as a science essay writer , remember that each essay is an opportunity to sharpen your skills, deepen your understanding, and contribute to the broader conversation in your field of study. Embrace the challenge, and let your passion for science shine through in your writing.

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

Effective Writing

To construct sentences that reflect your ideas, focus these sentences appropriately. Express one idea per sentence. Use your current topic — that is, what you are writing about — as the grammatical subject of your sentence (see Verbs: Choosing between active and passive voice ). When writing a complex sentence (a sentence that includes several clauses), place the main idea in the main clause rather than a subordinate clause. In particular, focus on the phenomenon at hand, not on the fact that you observed it.

Constructing your sentences logically is a good start, but it may not be enough. To ensure they are readable, make sure your sentences do not tax readers' short-term memory by obliging these readers to remember long pieces of text before knowing what to do with them. In other words, keep together what goes together. Then, work on conciseness: See whether you can replace long phrases with shorter ones or eliminate words without loss of clarity or accuracy.

The following screens cover the drafting process in more detail. Specifically, they discuss how to use verbs effectively and how to take care of your text's mechanics.

Shutterstock. Much of the strength of a clause comes from its verb. Therefore, to express your ideas accurately, choose an appropriate verb and use it well. In particular, use it in the right tense, choose carefully between active and passive voice, and avoid dangling verb forms.

Verbs are for describing actions, states, or occurrences. To give a clause its full strength and keep it short, do not bury the action, state, or occurrence in a noun (typically combined with a weak verb), as in "The catalyst produced a significant increase in conversion rate." Instead write, "The catalyst increased the conversion rate significantly." The examples below show how an action, state, or occurrence can be moved from a noun back to a verb.

Using the right tense

In your scientific paper, use verb tenses (past, present, and future) exactly as you would in ordinary writing. Use the past tense to report what happened in the past: what you did, what someone reported, what happened in an experiment, and so on. Use the present tense to express general truths, such as conclusions (drawn by you or by others) and atemporal facts (including information about what the paper does or covers). Reserve the future tense for perspectives: what you will do in the coming months or years. Typically, most of your sentences will be in the past tense, some will be in the present tense, and very few, if any, will be in the future tense.

Work done We collected blood samples from . . . Groves et al. determined the growth rate of . . . Consequently, astronomers decided to rename . . . Work reported Jankowsky reported a similar growth rate . . . In 2009, Chu published an alternative method to . . . Irarrázaval observed the opposite behavior in . . . Observations The mice in Group A developed , on average, twice as much . . . The number of defects increased sharply . . . The conversion rate was close to 95% . . .

Present tense

General truths Microbes in the human gut have a profound influence on . . . The Reynolds number provides a measure of . . . Smoking increases the risk of coronary heart disease . . . Atemporal facts This paper presents the results of . . . Section 3.1 explains the difference between . . . Behbood's 1969 paper provides a framework for . . .

Future tense

Perspectives In a follow-up experiment, we will study the role of . . . The influence of temperature will be the object of future research . . .

Note the difference in scope between a statement in the past tense and the same statement in the present tense: "The temperature increased linearly over time" refers to a specific experiment, whereas "The temperature increases linearly over time" generalizes the experimental observation, suggesting that the temperature always increases linearly over time in such circumstances.

In complex sentences, you may have to combine two different tenses — for example, "In 1905, Albert Einstein postulated that the speed of light is constant . . . . " In this sentence, postulated refers to something that happened in the past (in 1905) and is therefore in the past tense, whereas is expresses a general truth and is in the present tense.

Choosing between active and passive voice

In English, verbs can express an action in one of two voices. The active voice focuses on the agent: "John measured the temperature." (Here, the agent — John — is the grammatical subject of the sentence.) In contrast, the passive voice focuses on the object that is acted upon: "The temperature was measured by John." (Here, the temperature, not John, is the grammatical subject of the sentence.)

To choose between active and passive voice, consider above all what you are discussing (your topic) and place it in the subject position. For example, should you write "The preprocessor sorts the two arrays" or "The two arrays are sorted by the preprocessor"? If you are discussing the preprocessor, the first sentence is the better option. In contrast, if you are discussing the arrays, the second sentence is better. If you are unsure what you are discussing, consider the surrounding sentences: Are they about the preprocessor or the two arrays?

The desire to be objective in scientific writing has led to an overuse of the passive voice, often accompanied by the exclusion of agents: "The temperature was measured " (with the verb at the end of the sentence). Admittedly, the agent is often irrelevant: No matter who measured the temperature, we would expect its value to be the same. However, a systematic preference for the passive voice is by no means optimal, for at least two reasons.

For one, sentences written in the passive voice are often less interesting or more difficult to read than those written in the active voice. A verb in the active voice does not require a person as the agent; an inanimate object is often appropriate. For example, the rather uninteresting sentence "The temperature was measured . . . " may be replaced by the more interesting "The measured temperature of 253°C suggests a secondary reaction in . . . ." In the second sentence, the subject is still temperature (so the focus remains the same), but the verb suggests is in the active voice. Similarly, the hard-to-read sentence "In this section, a discussion of the influence of the recirculating-water temperature on the conversion rate of . . . is presented " (long subject, verb at the end) can be turned into "This section discusses the influence of . . . . " The subject is now section , which is what this sentence is really about, yet the focus on the discussion has been maintained through the active-voice verb discusses .

As a second argument against a systematic preference for the passive voice, readers sometimes need people to be mentioned. A sentence such as "The temperature is believed to be the cause for . . . " is ambiguous. Readers will want to know who believes this — the authors of the paper, or the scientific community as a whole? To clarify the sentence, use the active voice and set the appropriate people as the subject, in either the third or the first person, as in the examples below.

Biologists believe the temperature to be . . . Keustermans et al. (1997) believe the temperature to be . . . The authors believe the temperature to be . . . We believe the temperature to be . . .

Avoiding dangling verb forms

A verb form needs a subject, either expressed or implied. When the verb is in a non-finite form, such as an infinitive ( to do ) or a participle ( doing ), its subject is implied to be the subject of the clause, or sometimes the closest noun phrase. In such cases, construct your sentences carefully to avoid suggesting nonsense. Consider the following two examples.

To dissect its brain, the affected fly was mounted on a . . . After aging for 72 hours at 50°C, we observed a shift in . . .

Here, the first sentence implies that the affected fly dissected its own brain, and the second implies that the authors of the paper needed to age for 72 hours at 50°C in order to observe the shift. To restore the intended meaning while keeping the infinitive to dissect or the participle aging , change the subject of each sentence as appropriate:

To dissect its brain, we mounted the affected fly on a . . . After aging for 72 hours at 50°C, the samples exhibited a shift in . . .

Alternatively, you can change or remove the infinitive or participle to restore the intended meaning:

To have its brain dissected , the affected fly was mounted on a . . . After the samples aged for 72 hours at 50°C, we observed a shift in . . .

In communication, every detail counts. Although your focus should be on conveying your message through an appropriate structure at all levels, you should also save some time to attend to the more mechanical aspects of writing in English, such as using abbreviations, writing numbers, capitalizing words, using hyphens when needed, and punctuating your text correctly.

Using abbreviations

Beware of overusing abbreviations, especially acronyms — such as GNP for gold nanoparticles . Abbreviations help keep a text concise, but they can also render it cryptic. Many acronyms also have several possible extensions ( GNP also stands for gross national product ).

Write acronyms (and only acronyms) in all uppercase ( GNP , not gnp ).

Introduce acronyms systematically the first time they are used in a document. First write the full expression, then provide the acronym in parentheses. In the full expression, and unless the journal to which you submit your paper uses a different convention, capitalize the letters that form the acronym: "we prepared Gold NanoParticles (GNP) by . . . " These capitals help readers quickly recognize what the acronym designates.

- Do not use capitals in the full expression when you are not introducing an acronym: "we prepared gold nanoparticles by… "

- As a more general rule, use first what readers know or can understand best, then put in parentheses what may be new to them. If the acronym is better known than the full expression, as may be the case for techniques such as SEM or projects such as FALCON, consider placing the acronym first: "The FALCON (Fission-Activated Laser Concept) program at…"

- In the rare case that an acronym is commonly known, you might not need to introduce it. One example is DNA in the life sciences. When in doubt, however, introduce the acronym.

In papers, consider the abstract as a stand-alone document. Therefore, if you use an acronym in both the abstract and the corresponding full paper, introduce that acronym twice: the first time you use it in the abstract and the first time you use it in the full paper. However, if you find that you use an acronym only once or twice after introducing it in your abstract, the benefit of it is limited — consider avoiding the acronym and using the full expression each time (unless you think some readers know the acronym better than the full expression).

Writing numbers

In general, write single-digit numbers (zero to nine) in words, as in three hours , and multidigit numbers (10 and above) in numerals, as in 24 hours . This rule has many exceptions, but most of them are reasonably intuitive, as shown hereafter.

Use numerals for numbers from zero to nine

- when using them with abbreviated units ( 3 mV );

- in dates and times ( 3 October , 3 pm );

- to identify figures and other items ( Figure 3 );

- for consistency when these numbers are mixed with larger numbers ( series of 3, 7, and 24 experiments ).

Use words for numbers above 10 if these numbers come at the beginning of a sentence or heading ("Two thousand eight was a challenging year for . . . "). As an alternative, rephrase the sentence to avoid this issue altogether ("The year 2008 was challenging for . . . " ) .

Capitalizing words

Capitals are often overused. In English, use initial capitals

- at beginnings: the start of a sentence, of a heading, etc.;

- for proper nouns, including nouns describing groups (compare physics and the Physics Department );

- for items identified by their number (compare in the next figure and in Figure 2 ), unless the journal to which you submit your paper uses a different convention;

- for specific words: names of days ( Monday ) and months ( April ), adjectives of nationality ( Algerian ), etc.

In contrast, do not use initial capitals for common nouns: Resist the temptation to glorify a concept, technique, or compound with capitals. For example, write finite-element method (not Finite-Element Method ), mass spectrometry (not Mass Spectrometry ), carbon dioxide (not Carbon Dioxide ), and so on, unless you are introducing an acronym (see Mechanics: Using abbreviations ).

Using hyphens

Punctuating text.

Punctuation has many rules in English; here are three that are often a challenge for non-native speakers.

As a rule, insert a comma between the subject of the main clause and whatever comes in front of it, no matter how short, as in "Surprisingly, the temperature did not increase." This comma is not always required, but it often helps and never hurts the meaning of a sentence, so it is good practice.

In series of three or more items, separate items with commas ( red, white, and blue ; yesterday, today, or tomorrow ). Do not use a comma for a series of two items ( black and white ).

In displayed lists, use the same punctuation as you would in normal text (but consider dropping the and ).

The system is fast, flexible, and reliable.

The system is fast, flexible, reliable.

This page appears in the following eBook

Topic rooms within Scientific Communication

Within this Subject (22)

- Communicating as a Scientist (3)

- Papers (4)

- Correspondence (5)

- Presentations (4)

- Conferences (3)

- Classrooms (3)

Other Topic Rooms

- Gene Inheritance and Transmission

- Gene Expression and Regulation

- Nucleic Acid Structure and Function

- Chromosomes and Cytogenetics

- Evolutionary Genetics

- Population and Quantitative Genetics

- Genes and Disease

- Genetics and Society

- Cell Origins and Metabolism

- Proteins and Gene Expression

- Subcellular Compartments

- Cell Communication

- Cell Cycle and Cell Division

© 2014 Nature Education

- Press Room |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

Visual Browse

- For Authors

- Collaboration

- Privacy Policy

- Conferences & Symposiums

Tools & Methods

How to successfully write a scientific essay.

Posted by Cody Rhodes

If you are undertaking a course which relates to science, you are more or less apt to write an essay on science. You need to know how to write a science essay irrespective of whether your professor gives you a topic or you come up with one. Additionally, you need to have an end objective in mind. Writing a science essay necessitates that you produce an article which has all the details and facts about the subject matter and it ought to be to the point. Also, you need to know and understand that science essays are more or less different from other types of essays. They require you to be analytical and precise when answering questions. Hence, this can be quite challenging and tiresome. However, that should not deter you from learning how to write your paper. You can always inquire for pre-written research papers for sale from writing services like EssayZoo.

Also, you can read other people’s articles and find out how they produce and develop unique and high-quality papers. Moreover, this will help you understand how to approach your essays in different ways. Nonetheless, if you want to learn how to write a scientific paper in a successful manner, consider the following tips.

Select a topic for your article Like any other type of essay, you need to have a topic before you start the actual writing process. Your professor or instructor may give you a science essay topic to write about or ask you to come up with yours. When selecting a topic for your paper, ensure that you choose one you can write about. Do not pick a complex topic which can make the writing process boring and infuriating for you. Instead, choose one that you are familiar with. Select a topic you will not struggle gathering information about. Also, you need to have an interest in it. If you are unable to come up with a good topic, trying reading other people’s articles. This will help you develop a topic with ease.

Draft a plan After selecting a topic, the next step is drafting a plan or an outline. An outline is fundamental in writing a scientific essay as it is the foundation on which your paper is built. Additionally, it acts as a road map for your article. Hence, you need to incorporate all the thoughts and ideas you will include in your essay in the outline. You need to know what you will include in the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. Drafting a plan helps you save a lot of time when writing your paper. Also, it helps you to keep track of the primary objective of your article.

Start writing the article After drafting a plan, you can begin the writing process. Writing your paper will be smooth and easier as you have an outline which helps simplify the writing process. When writing your article, begin with a strong hook for your introduction. Dictate the direction your paper will take. Provide some background information and state the issue you will discuss as well as the solutions you have come up with. Arrange the body of your article according to the essay structure you will use to guide you. Also, ensure that you use transitory sentences to show the relationship between the paragraphs of your article. Conclude your essay by summarizing all the key points. Also, highlight the practical potential of our findings and their impacts.

Proofread and check for errors in the paper Before submitting or forwarding your article, it is fundamental that you proofread and correct all the errors that you come across. Delivering a paper that is full of mistakes can affect your overall performance in a negative manner. Thus, it is essential you revise your paper and check for errors. Correct all of them. Ask a friend to proofread your paper. He or she may spot some of the mistakes you did not come across.

In conclusion, writing a scientific essay differs from writing other types of papers. A scientific essay requires you to produce an article which has all the information and facts about the subject matter and it ought to be to the point. Nonetheless, the scientific essay formats similar to the format of any other essay: introduction, body, and conclusion. You need to use your outline to guide you through the writing process. To learn how to write a scientific essay in a successful manner, consider the tips above.

Related Articles:

2 responses to how to successfully write a scientific essay.

Hai…you have posted great article, it really helpful to us.. I will refer this page to my friends; I hope you will like to read – scientific research paper writing service

Nice concentration on education blogs. Such a great work regarding education and online study to gain knowledge and time.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Top Keywords

Diabetes | Alzheimer’s disease Cancer | Breast cancer | Tumor Blood pressure | Heart Brain | Kidney | Liver | Lung Stress | Pain | Therapy Infection | Inflammation | Injury DNA | RNA | Receptor | Nanoparticles Bacteria | Virus | Plant

See more …

Proofread or Perish: Editing your scientific writing for successful publication

Lab Leader makes software applications for experiment design in life science

Cyagen Biosciences – Helping you choose the right animal model for your research

Labcollector lims and eln for improving productivity in the lab.

Image Cytometer – NucleoCounter® NC-3000™

Recent posts.

- Does UV-B radiation modify gene expression?

- Ferrate technology: an innovative solution for sustainable sewer and wastewater management

- Sleep abnormalities in different clinical stages of psychosis

- A compact high yield isotope enrichment system

- Late second trimester miscarriages

Making your scientific discoveries understandable to others is one of the most important things you can do as a scientist. You might come up with brilliant ideas, design clever experiments, and make groundbreaking discoveries. But if you can’t explain your work to your fellow scientists, your career won’t move forward.

Back in the early 90s, during my time at the University of California in Irvine , my research led me to a paper citation that seemed relevant to my work. I went to great lengths to get a hold of that paper, which was written in English but not by a native English speaker. Unfortunately, I couldn’t understand it well enough to confirm if the cited information was accurate. I tried contacting the authors multiple times but got no response. As a result, I couldn’t reference their work in my own papers, even though it seemed relevant. Being a good writer is crucial for success in science. Speaking English fluently doesn’t necessarily mean you can write well, even for native speakers. Writing skills improve with practice and guidance. However, simply having experience or guidance won’t make you a better writer unless you put in the effort to write.

- AI Tools for Science Writing: Why, How, When, and When Not To

- 15 Tips for Writing Influential Science Articles

15 Tips for Self-Editing Your Science Manuscript

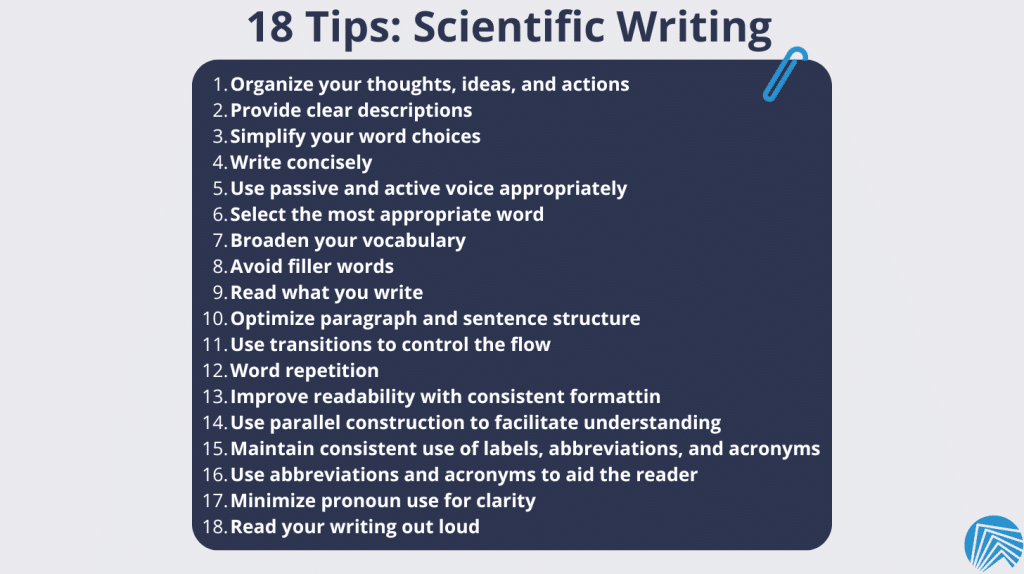

Tips to Improve your Scientific Writing

1. organize your thoughts, ideas, and actions in a logical manner.

Begin with sufficient background information to take your reader along the pathway from your observations to your hypothesis. Describe the background to appeal to a broad group of readers. Provide sufficient context to communicate the significance of your inquiry and experimental findings. Omit extraneous information so that the reader can obtain a clear picture. Group similar ideas together and state your ideas and thoughts concisely. Present ideas in a consistent manner throughout the manuscript. The most common structure of a scientific manuscript is the IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) format.

2. Provide clear descriptions

Repeat complex concepts as needed, explaining them from various angles. Begin with simplicity, advancing complexity as required for comprehension. Tailor your writing to your audience’s level of expertise, whether they understand specialized terms or require prior explanations. Keep your explanations straightforward.

3. Simplify your word choices

Utilize clear, straightforward language to ensure that both students and researchers, regardless of their field or English proficiency, can easily comprehend and engage with your research.

4. Write concisely

Note that this article mentions “ concise writing ” several times. Avoid lengthy or needless descriptions and paragraphs, as nobody values them.

5. Use passive and active voice appropriately

In science writing, it is important to know when to use passive and active voice. Using active voice makes your writing more natural, direct, and engaging, and you should employ it when discussing widely accepted findings. The Introduction section should primarily employ active voice because it narrates “what is.” However, when discussing the results of a particular study, it’s advisable to use passive voice. In the Methods and Results sections, passive voice should be employed to describe what you did and what you found. In the Discussion section, a mixture of passive and active voice is acceptable, but take care not to mix the 2 together in a single sentence.

6. Select the most appropriate word

Selecting the appropriate words can be challenging. The best words accurately capture what the author is trying to convey. If a word is not sufficiently precise, use a thesaurus to replace the word or phrase with a more appropriate word. Precise words allow for specific, clear, and accurate expression. While science writing differs from literature in that it does not need to be colorful, it should not be boring.

7. Broaden your vocabulary

Use clear, specific, and concrete words. Expand your vocabulary by reading in a broad range of fields and looking up terms you don’t know.

8. Avoid filler words

Filler words are unnecessary words that are vague and meaningless or do not add to the meaning or clarity of the sentence. Consider the following examples: “ it is ”, “ it was ”, “ there is ”, and “ there has been ”, “ it is important “, “ it is hypothesized that “, “ it was predicted that “, “ there is evidence suggesting that “, “ in order to ”, and “ there is a significant relationship “. All of these phrases can be replaced with more direct and clear language. See our list of words and phrases to avoid here .

9. Read what you write

Ensure you vary sentence length to maintain reader engagement and avoid a monotonous rhythm. However, don’t create excessively long or convoluted sentences that might hinder the reader’s comprehension. To enhance readability, consider reading the manuscript aloud to yourself after taking a break or having someone else review it.

10. Optimize paragraph and sentence structure

Each paragraph should present a single unifying idea or concept. Extremely long paragraphs tend to distract or confuse readers. If longer paragraphs are necessary, alternate them with shorter paragraphs to provide balance and rhythm to your writing. A good sentence allows readers to obtain critical information with the least effort.

Poor sentence structure interferes with the flow. Keep modifiers close to the object they are modifying. Consider the following sentence: “ Systemic diseases that may affect joint function such as infection should be closely monitored. ” In this example, “such as infection” is misplaced, as it is not a joint function, but rather a systemic disease. The meaning is more clear in the revised sentence: “ Systemic diseases such as infection that may affect joint function should be closely monitored. ”

11. Use transitions to control the flow

Sentences and paragraphs should flow seamlessly. Place transitional phrases and sentences at the beginning and end of the paragraphs to help the reader move smoothly through the paper.

12. Word repetition

Avoid repetitive use of the same word or phrase; opt for a more descriptive alternative whenever possible. Ensure that you do not sacrifice precision for variability. See our science-related Word Choice list here .

13. Improve readability with consistent formatting

Although in many cases it is no longer necessary to format your manuscript for a specific journal before peer review, you should pay attention to formatting for consistency. Use the same font size throughout; format headings consistently (e.g., bolded or not bolded, all uppercase or not, italicized or not); and references should be provided in an easy-to-follow, consistent format. Use appropriate subheadings in the Materials and Methods, and Results sections to help the reader quickly navigate your paper.

14. Use parallel construction to facilitate understanding

Your hypothesis, experimental measures, and results should be presented in the same order in the Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Tables. Words or phrases joined by coordinating conjunctions (and, but, for, nor, or, so, and yet) should have the same form.

15. Maintain consistent use of labels, abbreviations, and acronyms

Measures and variable/group names and labels should be consistent in both form and content throughout the text to avoid confusing the reader.

16. Use abbreviations and acronyms to aid the reader

Only use abbreviations/acronyms to help the reader more easily understand the paper. Follow the general rule of utilizing standard, accepted abbreviations/acronyms that appear at least 3 times in the main text of the paper. Always ask yourself, “Does this benefit me or the reader?” Exceptions might be applicable for widely-used abbreviations/acronyms where spelling them out might confuse the reader.

17. Minimize pronoun use for clarity

Make sure every pronoun is very clear, so the reader knows what it represents. In this case, being redundant may contribute to the clarity. Don’t refer to ‘this’ or ‘that’ because it makes the reader go back to the previous paragraph to see what ‘this’ or ‘that’ means. Also, limit or avoid the use of “former” and latter”.

18. Read your writing out loud

To assess the rhythm and identify repetitive words and phrases both within and between sentences and paragraphs, read your final paper aloud. Frequently, you will encounter unnecessary words that can be removed or substituted with more suitable alternatives.

Remember, your writing is your chance to show the scientific world who you are. You want to present a scholarly, clear, well-written description of your interests, ideas, results, and interpretations to encourage dialogue between scientists. Change your goal from that of simply publishing your manuscript to that of publishing an interesting manuscript that encourages discussion and citation, and inspires additional questions and hypotheses due to its fundamental clarity to the reader.

Want MORE Writing Tips?

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Email (required) *

Recent Articles

Discover 15 expert tips for self-editing your science manuscript and why hiring a professional editor could enhance its quality and impact.

The Art of Tailored Editing for Grant Applications and Scientific Manuscripts

Discover editing strategies for science grant applications and manuscripts to clearly communicate research and secure funding. 2 min read…

Optimizing Science Document Translations: Elevating Impact Through Post-Translation Editing

Learn the role of post-translation editing, ensuring manuscripts meet the standards of English-language journals for global impact.

Need Help With Your Writing?

At SciTechEdit, we are committed to delivering top-notch science editing services to enhance the impact and clarity of your research. We understand the importance of effective communication in the scientific community, and our team of experienced editors is here to help you refine and elevate your scientific manuscripts.

Storytelling in Science Writing

Page Contents

- 2.1 The And, But, Therefore Technique in Film and TV

- 2.2 The And, But, Therefore Technique in Science Writing

- 2.3 Let’s Explore the ABT Structure

- 2.4.1 And, And, And (AAA)

- 2.4.2 And, But, Therefore (ABT)

- 2.4.3 Despite, However, Yet (DHY)

- 2.5.1 Structuring your research article

- 2.5.2 Structuring your whole thesis and thesis chapters

- 2.5.3 Structuring your Abstract

- 2.5.4 Structuring your Introduction

- 2.6 Your Turn to Create an ABT Paragraph

- 2.7 More Information on the And, But, Therefore Technique

- 3.1 The Logline Technique in Film and TV

- 3.2 The Logline Technique in Science Writing

- 3.3 Why Use the Logline Technique?

- 3.4 When to Use the Logline Technique?

- 3.5 Your Turn to Create a Logline

- 3.6 More Information on the Logline Technique

- 4.1 Storyboarding in Film and TV

- 4.2 Storyboarding in Science Writing

- 4.3 Three Different Methods for Creating Storyboards

- 4.4 Storyboard Examples

- 4.5 Why Use the Storyboarding Technique?

- 4.6 When to Use the Storyboarding Technique?

- 4.7 Your Turn to Create a Storyboard

- 4.8 More Information on the Storyboarding Technique

- 5.1 How to Use All Techniques in Combination

Welcome to the Storytelling in Science Writing module. The techniques in this module all come from the world of film and TV. The first technique, using the And, But, Therefore structure, can create an engaging narrative. The second technique, creating a logline, can help identify the single focus of your scientific articles. The last technique, creating a storyboard, can help with structuring your writing.

I am Chris Greyson-Gaito, and I will help you through the different storytelling techniques. I am currently a researcher examining food webs and ecological-economics. I really enjoy trying to incorporate story into my science writing. I have found the techniques I will show here to be immensely helpful. I hope you will find these techniques similarly useful.

[A series of animated characters and objects appear in sequence over a backdrop that resembles an unfolded scroll. First, a trail of footprints appears. A detective wearing a hat and smoking a pipe follows the trail of footprints. A superhero with a ponytail and cape flies overhead. A knight riding a horse points a sword to the sky. The horse rears back on its hind legs then charges away. A witch and a cat on a broomstick fly into view. The cat extends a paw and shoots a fireball. A pirate ship lets loose a barrage of cannon balls. A dragon flaps its wings as it flies overhead. A rocket ship appears next to a planet with a ring system. The planet disappears and the rocket ship transforms into a star. The Writing in the Sciences logo and the title “Storytelling in Science Writing” appears.]

[The narrator Chris, a white man wearing a blue t-shirt, appears below the logo and video title.]

Welcome to the Storytelling in Science Writing module. My name is Chris Greyson-Gaito and I will be your facilitator. I am a former writing support teaching assistant at the University of Guelph who mentored students through the writing process in all disciplines. Currently, I am a researcher who uses mathematical modelling to explore food webs and ecological-economics.

In this module, we will explore how to incorporate story and narrative into your scientific writing. I hope by the end of this module you will understand that scientific writing can be engaging and fun. We will go through three techniques from the TV and film scriptwriting industry that will help you write engaging scientific articles and theses.

First, we will use the And, But, Therefore structure to write in an engaging manner. Next, we will create loglines to identify the single problem of your paper. Finally, we will explore storyboarding to help structure your paper.

And, But, Therefore

The and, but, therefore technique in film and tv.

Let’s use a silly story I created to understand the And, But, Therefore technique.

The And, But, Therefore Technique in Science Writing

The And, But, Therefore (ABT) structure can be used in scientific writing. Below, I highlight the general purpose of each And, But, and Therefore section and compare how this structure functions in a fictional story versus in a scientific article:

Let’s Explore the ABT Structure

On the following document, follow the instructions to explore the ABT structure in stories and scientific articles.

NOTE: You can view this document online, but you can also download it below as an accessible screen reader document.

Download PDF (Explore the ABT Structure – Worksheet)

Why Use the And, But, Therefore Technique?

To answer the question “ Why use the And, But, Therefore technique?” , let’s compare the ABT structure with other narrative structures in, what Dr. Randy Olson termed, the “narrative spectrum.”

And, And, And (AAA)

- List of facts without narrative

And, But, Therefore (ABT)

- Simple, cohesive narrative

Despite, However, Yet (DHY)

- Too many narrative directions

- Too many tensions, conflicts, or problems