Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

Your ultimate guide to questionnaires and how to design a good one

The written questionnaire is the heart and soul of any survey research project. Whether you conduct your survey using an online questionnaire, in person, by email or over the phone, the way you design your questionnaire plays a critical role in shaping the quality of the data and insights that you’ll get from your target audience. Keep reading to get actionable tips.

What is a questionnaire?

A questionnaire is a research tool consisting of a set of questions or other ‘prompts’ to collect data from a set of respondents.

When used in most research, a questionnaire will consist of a number of types of questions (primarily open-ended and closed) in order to gain both quantitative data that can be analyzed to draw conclusions, and qualitative data to provide longer, more specific explanations.

A research questionnaire is often mistaken for a survey - and many people use the term questionnaire and survey, interchangeably.

But that’s incorrect.

Which is what we talk about next.

Get started with our free survey maker with 50+ templates

Survey vs. questionnaire – what’s the difference?

Before we go too much further, let’s consider the differences between surveys and questionnaires.

These two terms are often used interchangeably, but there is an important difference between them.

Survey definition

A survey is the process of collecting data from a set of respondents and using it to gather insights.

Survey research can be conducted using a questionnaire, but won’t always involve one.

Questionnaire definition

A questionnaire is the list of questions you circulate to your target audience.

In other words, the survey is the task you’re carrying out, and the questionnaire is the instrument you’re using to do it.

By itself, a questionnaire doesn’t achieve much.

It’s when you put it into action as part of a survey that you start to get results.

Advantages vs disadvantages of using a questionnaire

While a questionnaire is a popular method to gather data for market research or other studies, there are a few disadvantages to using this method (although there are plenty of advantages to using a questionnaire too).

Let’s have a look at some of the advantages and disadvantages of using a questionnaire for collecting data.

Advantages of using a questionnaire

1. questionnaires are relatively cheap.

Depending on the complexity of your study, using a questionnaire can be cost effective compared to other methods.

You simply need to write your survey questionnaire, and send it out and then process the responses.

You can set up an online questionnaire relatively easily, or simply carry out market research on the street if that’s the best method.

2. You can get and analyze results quickly

Again depending on the size of your survey you can get results back from a questionnaire quickly, often within 24 hours of putting the questionnaire live.

It also means you can start to analyze responses quickly too.

3. They’re easily scalable

You can easily send an online questionnaire to anyone in the world and with the right software you can quickly identify your target audience and your questionnaire to them.

4. Questionnaires are easy to analyze

If your questionnaire design has been done properly, it’s quick and easy to analyze results from questionnaires once responses start to come back.

This is particularly useful with large scale market research projects.

Because all respondents are answering the same questions, it’s simple to identify trends.

5. You can use the results to make accurate decisions

As a research instrument, a questionnaire is ideal for commercial research because the data you get back is from your target audience (or ideal customers) and the information you get back on their thoughts, preferences or behaviors allows you to make business decisions.

6. A questionnaire can cover any topic

One of the biggest advantages of using questionnaires when conducting research is (because you can adapt them using different types and styles of open ended questions and closed ended questions) they can be used to gather data on almost any topic.

There are many types of questionnaires you can design to gather both quantitative data and qualitative data - so they’re a useful tool for all kinds of data analysis.

Disadvantages of using a questionnaire

1. respondents could lie.

This is by far the biggest risk with a questionnaire, especially when dealing with sensitive topics.

Rather than give their actual opinion, a respondent might feel pressured to give the answer they deem more socially acceptable, which doesn’t give you accurate results.

2. Respondents might not answer every question

There are all kinds of reasons respondents might not answer every question, from questionnaire length, they might not understand what’s being asked, or they simply might not want to answer it.

If you get questionnaires back without complete responses it could negatively affect your research data and provide an inaccurate picture.

3. They might interpret what’s being asked incorrectly

This is a particular problem when running a survey across geographical boundaries and often comes down to the design of the survey questionnaire.

If your questions aren’t written in a very clear way, the respondent might misunderstand what’s being asked and provide an answer that doesn’t reflect what they actually think.

Again this can negatively affect your research data.

4. You could introduce bias

The whole point of producing a questionnaire is to gather accurate data from which decisions can be made or conclusions drawn.

But the data collected can be heavily impacted if the researchers accidentally introduce bias into the questions.

This can be easily done if the researcher is trying to prove a certain hypothesis with their questionnaire, and unwittingly write questions that push people towards giving a certain answer.

In these cases respondents’ answers won’t accurately reflect what is really happening and stop you gathering more accurate data.

5. Respondents could get survey fatigue

One issue you can run into when sending out a questionnaire, particularly if you send them out regularly to the same survey sample, is that your respondents could start to suffer from survey fatigue.

In these circumstances, rather than thinking about the response options in the questionnaire and providing accurate answers, respondents could start to just tick boxes to get through the questionnaire quickly.

Again, this won’t give you an accurate data set.

Questionnaire design: How to do it

It’s essential to carefully craft a questionnaire to reduce survey error and optimize your data . The best way to think about the questionnaire is with the end result in mind.

How do you do that?

Start with questions, like:

- What is my research purpose ?

- What data do I need?

- How am I going to analyze that data?

- What questions are needed to best suit these variables?

Once you have a clear idea of the purpose of your survey, you’ll be in a better position to create an effective questionnaire.

Here are a few steps to help you get into the right mindset.

1. Keep the respondent front and center

A survey is the process of collecting information from people, so it needs to be designed around human beings first and foremost.

In his post about survey design theory, David Vannette, PhD, from the Qualtrics Methodology Lab explains the correlation between the way a survey is designed and the quality of data that is extracted.

“To begin designing an effective survey, take a step back and try to understand what goes on in your respondents’ heads when they are taking your survey.

This step is critical to making sure that your questionnaire makes it as likely as possible that the response process follows that expected path.”

From writing the questions to designing the survey flow, the respondent’s point of view should always be front and center in your mind during a questionnaire design.

2. How to write survey questions

Your questionnaire should only be as long as it needs to be, and every question needs to deliver value.

That means your questions must each have an individual purpose and produce the best possible data for that purpose, all while supporting the overall goal of the survey.

A question must also must be phrased in a way that is easy for all your respondents to understand, and does not produce false results.

To do this, remember the following principles:

Get into the respondent's head

The process for a respondent answering a survey question looks like this:

- The respondent reads the question and determines what information they need to answer it.

- They search their memory for that information.

- They make judgments about that information.

- They translate that judgment into one of the answer options you’ve provided. This is the process of taking the data they have and matching that information with the question that’s asked.

When wording questions, make sure the question means the same thing to all respondents. Words should have one meaning, few syllables, and the sentences should have few words.

Only use the words needed to ask your question and not a word more .

Note that it’s important that the respondent understands the intent behind your question.

If they don’t, they may answer a different question and the data can be skewed.

Some contextual help text, either in the introduction to the questionnaire or before the question itself, can help make sure the respondent understands your goals and the scope of your research.

Use mutually exclusive responses

Be sure to make your response categories mutually exclusive.

Consider the question:

What is your age?

Respondents that are 31 years old have two options, as do respondents that are 40 and 55. As a result, it is impossible to predict which category they will choose.

This can distort results and frustrate respondents. It can be easily avoided by making responses mutually exclusive.

The following question is much better:

This question is clear and will give us better results.

Ask specific questions

Nonspecific questions can confuse respondents and influence results.

Do you like orange juice?

- Like very much

- Neither like nor dislike

- Dislike very much

This question is very unclear. Is it asking about taste, texture, price, or the nutritional content? Different respondents will read this question differently.

A specific question will get more specific answers that are actionable.

How much do you like the current price of orange juice?

This question is more specific and will get better results.

If you need to collect responses about more than one aspect of a subject, you can include multiple questions on it. (Do you like the taste of orange juice? Do you like the nutritional content of orange juice? etc.)

Use a variety of question types

If all of your questionnaire, survey or poll questions are structured the same way (e.g. yes/no or multiple choice) the respondents are likely to become bored and tune out. That could mean they pay less attention to how they’re answering or even give up altogether.

Instead, mix up the question types to keep the experience interesting and varied. It’s a good idea to include questions that yield both qualitative and quantitative data.

For example, an open-ended questionnaire item such as “describe your attitude to life” will provide qualitative data – a form of information that’s rich, unstructured and unpredictable. The respondent will tell you in their own words what they think and feel.

A quantitative / close-ended questionnaire item, such as “Which word describes your attitude to life? a) practical b) philosophical” gives you a much more structured answer, but the answers will be less rich and detailed.

Open-ended questions take more thought and effort to answer, so use them sparingly. They also require a different kind of treatment once your survey is in the analysis stage.

3. Pre-test your questionnaire

Always pre-test a questionnaire before sending it out to respondents. This will help catch any errors you might have missed. You could ask a colleague, friend, or an expert to take the survey and give feedback. If possible, ask a few cognitive questions like, “how did you get to that response?” and “what were you thinking about when you answered that question?” Figure out what was easy for the responder and where there is potential for confusion. You can then re-word where necessary to make the experience as frictionless as possible.

If your resources allow, you could also consider using a focus group to test out your survey. Having multiple respondents road-test the questionnaire will give you a better understanding of its strengths and weaknesses. Match the focus group to your target respondents as closely as possible, for example in terms of age, background, gender, and level of education.

Note: Don't forget to make your survey as accessible as possible for increased response rates.

Questionnaire examples and templates

There are free questionnaire templates and example questions available for all kinds of surveys and market research, many of them online. But they’re not all created equal and you should use critical judgement when selecting one. After all, the questionnaire examples may be free but the time and energy you’ll spend carrying out a survey are not.

If you’re using online questionnaire templates as the basis for your own, make sure it has been developed by professionals and is specific to the type of research you’re doing to ensure higher completion rates. As we’ve explored here, using the wrong kinds of questions can result in skewed or messy data, and could even prompt respondents to abandon the questionnaire without finishing or give thoughtless answers.

You’ll find a full library of downloadable survey templates in the Qualtrics Marketplace , covering many different types of research from employee engagement to post-event feedback . All are fully customizable and have been developed by Qualtrics experts.

Qualtrics // Experience Management

Qualtrics, the leader and creator of the experience management category, is a cloud-native software platform that empowers organizations to deliver exceptional experiences and build deep relationships with their customers and employees.

With insights from Qualtrics, organizations can identify and resolve the greatest friction points in their business, retain and engage top talent, and bring the right products and services to market. Nearly 20,000 organizations around the world use Qualtrics’ advanced AI to listen, understand, and take action. Qualtrics uses its vast universe of experience data to form the largest database of human sentiment in the world. Qualtrics is co-headquartered in Provo, Utah and Seattle.

Related Articles

December 20, 2023

Top market research analyst skills for 2024

November 7, 2023

Brand Experience

The 4 market research trends redefining insights in 2024

September 14, 2023

How BMG and Loop use data to make critical decisions

August 21, 2023

Designing for safety: Making user consent and trust an organizational asset

June 27, 2023

The fresh insights people: Scaling research at Woolworths Group

June 20, 2023

Bank less, delight more: How Bankwest built an engine room for customer obsession

June 16, 2023

How Qualtrics Helps Three Local Governments Drive Better Outcomes Through Data Insights

April 1, 2023

Academic Experience

How to write great survey questions (with examples)

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

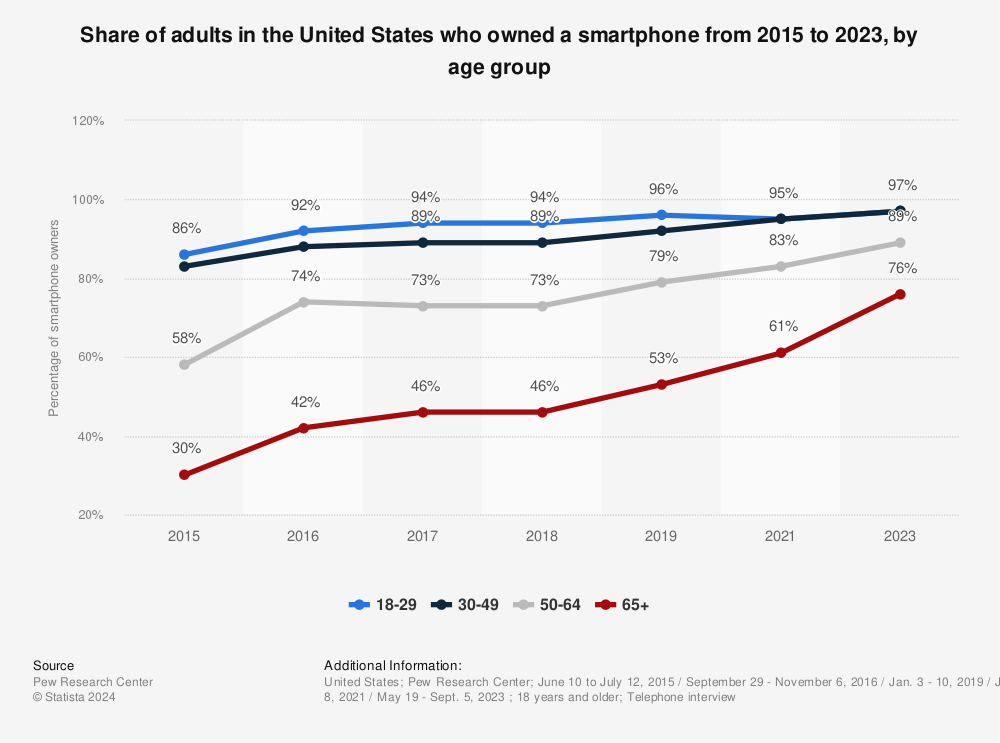

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

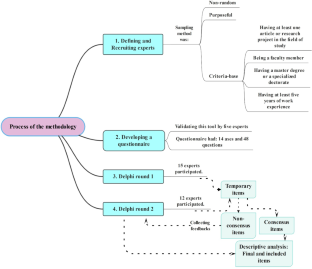

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

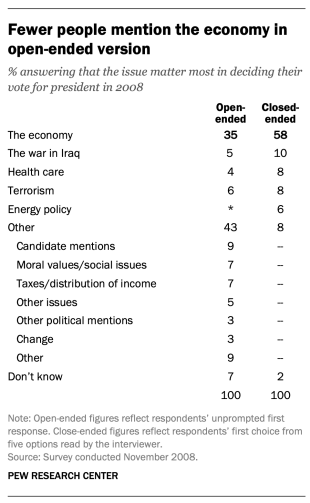

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

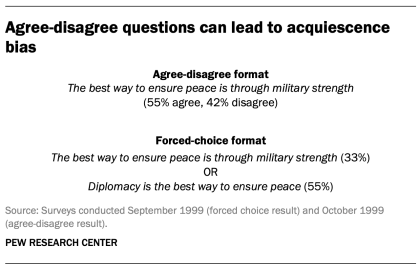

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

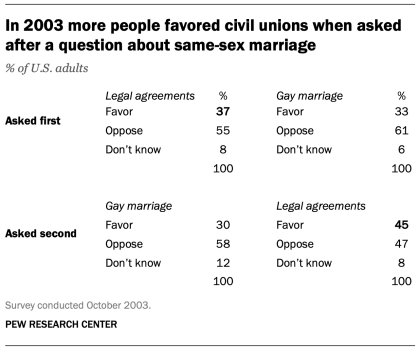

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

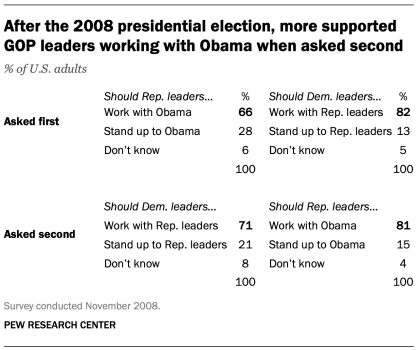

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).

The order questions are asked is of particular importance when tracking trends over time. As a result, care should be taken to ensure that the context is similar each time a question is asked. Modifying the context of the question could call into question any observed changes over time (see measuring change over time for more information).

A questionnaire, like a conversation, should be grouped by topic and unfold in a logical order. It is often helpful to begin the survey with simple questions that respondents will find interesting and engaging. Throughout the survey, an effort should be made to keep the survey interesting and not overburden respondents with several difficult questions right after one another. Demographic questions such as income, education or age should not be asked near the beginning of a survey unless they are needed to determine eligibility for the survey or for routing respondents through particular sections of the questionnaire. Even then, it is best to precede such items with more interesting and engaging questions. One virtue of survey panels like the ATP is that demographic questions usually only need to be asked once a year, not in each survey.

U.S. Surveys

Other research methods.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Privacy Policy

Home » Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Table of Contents

Survey Research

Definition:

Survey Research is a quantitative research method that involves collecting standardized data from a sample of individuals or groups through the use of structured questionnaires or interviews. The data collected is then analyzed statistically to identify patterns and relationships between variables, and to draw conclusions about the population being studied.

Survey research can be used to answer a variety of questions, including:

- What are people’s opinions about a certain topic?

- What are people’s experiences with a certain product or service?

- What are people’s beliefs about a certain issue?

Survey Research Methods

Survey Research Methods are as follows:

- Telephone surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents over the phone, often used in market research or political polling.

- Face-to-face surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents in person, often used in social or health research.

- Mail surveys: A survey research method where questionnaires are sent to respondents through mail, often used in customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Online surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through online platforms, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Email surveys: A survey research method where questionnaires are sent to respondents through email, often used in customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Mixed-mode surveys: A survey research method that combines two or more survey modes, often used to increase response rates or reach diverse populations.

- Computer-assisted surveys: A survey research method that uses computer technology to administer or collect survey data, often used in large-scale surveys or data collection.

- Interactive voice response surveys: A survey research method where respondents answer questions through a touch-tone telephone system, often used in automated customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Mobile surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through mobile devices, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Group-administered surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to a group of respondents simultaneously, often used in education or training evaluation.

- Web-intercept surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to website visitors, often used in website or user experience research.

- In-app surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to users of a mobile application, often used in mobile app or user experience research.

- Social media surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through social media platforms, often used in social media or brand awareness research.

- SMS surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through text messaging, often used in customer feedback or opinion surveys.

- IVR surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through an interactive voice response system, often used in automated customer feedback or opinion surveys.

- Mixed-method surveys: A survey research method that combines both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, often used in exploratory or mixed-method research.

- Drop-off surveys: A survey research method where respondents are provided with a survey questionnaire and asked to return it at a later time or through a designated drop-off location.

- Intercept surveys: A survey research method where respondents are approached in public places and asked to participate in a survey, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Hybrid surveys: A survey research method that combines two or more survey modes, data sources, or research methods, often used in complex or multi-dimensional research questions.

Types of Survey Research

There are several types of survey research that can be used to collect data from a sample of individuals or groups. following are Types of Survey Research:

- Cross-sectional survey: A type of survey research that gathers data from a sample of individuals at a specific point in time, providing a snapshot of the population being studied.

- Longitudinal survey: A type of survey research that gathers data from the same sample of individuals over an extended period of time, allowing researchers to track changes or trends in the population being studied.

- Panel survey: A type of longitudinal survey research that tracks the same sample of individuals over time, typically collecting data at multiple points in time.

- Epidemiological survey: A type of survey research that studies the distribution and determinants of health and disease in a population, often used to identify risk factors and inform public health interventions.

- Observational survey: A type of survey research that collects data through direct observation of individuals or groups, often used in behavioral or social research.

- Correlational survey: A type of survey research that measures the degree of association or relationship between two or more variables, often used to identify patterns or trends in data.

- Experimental survey: A type of survey research that involves manipulating one or more variables to observe the effect on an outcome, often used to test causal hypotheses.

- Descriptive survey: A type of survey research that describes the characteristics or attributes of a population or phenomenon, often used in exploratory research or to summarize existing data.

- Diagnostic survey: A type of survey research that assesses the current state or condition of an individual or system, often used in health or organizational research.

- Explanatory survey: A type of survey research that seeks to explain or understand the causes or mechanisms behind a phenomenon, often used in social or psychological research.

- Process evaluation survey: A type of survey research that measures the implementation and outcomes of a program or intervention, often used in program evaluation or quality improvement.

- Impact evaluation survey: A type of survey research that assesses the effectiveness or impact of a program or intervention, often used to inform policy or decision-making.

- Customer satisfaction survey: A type of survey research that measures the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of customers with a product, service, or experience, often used in marketing or customer service research.

- Market research survey: A type of survey research that collects data on consumer preferences, behaviors, or attitudes, often used in market research or product development.

- Public opinion survey: A type of survey research that measures the attitudes, beliefs, or opinions of a population on a specific issue or topic, often used in political or social research.

- Behavioral survey: A type of survey research that measures actual behavior or actions of individuals, often used in health or social research.

- Attitude survey: A type of survey research that measures the attitudes, beliefs, or opinions of individuals, often used in social or psychological research.

- Opinion poll: A type of survey research that measures the opinions or preferences of a population on a specific issue or topic, often used in political or media research.

- Ad hoc survey: A type of survey research that is conducted for a specific purpose or research question, often used in exploratory research or to answer a specific research question.

Types Based on Methodology

Based on Methodology Survey are divided into two Types:

Quantitative Survey Research

Qualitative survey research.

Quantitative survey research is a method of collecting numerical data from a sample of participants through the use of standardized surveys or questionnaires. The purpose of quantitative survey research is to gather empirical evidence that can be analyzed statistically to draw conclusions about a particular population or phenomenon.

In quantitative survey research, the questions are structured and pre-determined, often utilizing closed-ended questions, where participants are given a limited set of response options to choose from. This approach allows for efficient data collection and analysis, as well as the ability to generalize the findings to a larger population.

Quantitative survey research is often used in market research, social sciences, public health, and other fields where numerical data is needed to make informed decisions and recommendations.

Qualitative survey research is a method of collecting non-numerical data from a sample of participants through the use of open-ended questions or semi-structured interviews. The purpose of qualitative survey research is to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences, perceptions, and attitudes of participants towards a particular phenomenon or topic.

In qualitative survey research, the questions are open-ended, allowing participants to share their thoughts and experiences in their own words. This approach allows for a rich and nuanced understanding of the topic being studied, and can provide insights that are difficult to capture through quantitative methods alone.

Qualitative survey research is often used in social sciences, education, psychology, and other fields where a deeper understanding of human experiences and perceptions is needed to inform policy, practice, or theory.

Data Analysis Methods

There are several Survey Research Data Analysis Methods that researchers may use, including:

- Descriptive statistics: This method is used to summarize and describe the basic features of the survey data, such as the mean, median, mode, and standard deviation. These statistics can help researchers understand the distribution of responses and identify any trends or patterns.

- Inferential statistics: This method is used to make inferences about the larger population based on the data collected in the survey. Common inferential statistical methods include hypothesis testing, regression analysis, and correlation analysis.

- Factor analysis: This method is used to identify underlying factors or dimensions in the survey data. This can help researchers simplify the data and identify patterns and relationships that may not be immediately apparent.

- Cluster analysis: This method is used to group similar respondents together based on their survey responses. This can help researchers identify subgroups within the larger population and understand how different groups may differ in their attitudes, behaviors, or preferences.

- Structural equation modeling: This method is used to test complex relationships between variables in the survey data. It can help researchers understand how different variables may be related to one another and how they may influence one another.

- Content analysis: This method is used to analyze open-ended responses in the survey data. Researchers may use software to identify themes or categories in the responses, or they may manually review and code the responses.

- Text mining: This method is used to analyze text-based survey data, such as responses to open-ended questions. Researchers may use software to identify patterns and themes in the text, or they may manually review and code the text.

Applications of Survey Research

Here are some common applications of survey research:

- Market Research: Companies use survey research to gather insights about customer needs, preferences, and behavior. These insights are used to create marketing strategies and develop new products.

- Public Opinion Research: Governments and political parties use survey research to understand public opinion on various issues. This information is used to develop policies and make decisions.

- Social Research: Survey research is used in social research to study social trends, attitudes, and behavior. Researchers use survey data to explore topics such as education, health, and social inequality.

- Academic Research: Survey research is used in academic research to study various phenomena. Researchers use survey data to test theories, explore relationships between variables, and draw conclusions.

- Customer Satisfaction Research: Companies use survey research to gather information about customer satisfaction with their products and services. This information is used to improve customer experience and retention.

- Employee Surveys: Employers use survey research to gather feedback from employees about their job satisfaction, working conditions, and organizational culture. This information is used to improve employee retention and productivity.

- Health Research: Survey research is used in health research to study topics such as disease prevalence, health behaviors, and healthcare access. Researchers use survey data to develop interventions and improve healthcare outcomes.

Examples of Survey Research

Here are some real-time examples of survey research:

- COVID-19 Pandemic Surveys: Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, surveys have been conducted to gather information about public attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions related to the pandemic. Governments and healthcare organizations have used this data to develop public health strategies and messaging.

- Political Polls During Elections: During election seasons, surveys are used to measure public opinion on political candidates, policies, and issues in real-time. This information is used by political parties to develop campaign strategies and make decisions.

- Customer Feedback Surveys: Companies often use real-time customer feedback surveys to gather insights about customer experience and satisfaction. This information is used to improve products and services quickly.

- Event Surveys: Organizers of events such as conferences and trade shows often use surveys to gather feedback from attendees in real-time. This information can be used to improve future events and make adjustments during the current event.

- Website and App Surveys: Website and app owners use surveys to gather real-time feedback from users about the functionality, user experience, and overall satisfaction with their platforms. This feedback can be used to improve the user experience and retain customers.

- Employee Pulse Surveys: Employers use real-time pulse surveys to gather feedback from employees about their work experience and overall job satisfaction. This feedback is used to make changes in real-time to improve employee retention and productivity.

Survey Sample

Purpose of survey research.

The purpose of survey research is to gather data and insights from a representative sample of individuals. Survey research allows researchers to collect data quickly and efficiently from a large number of people, making it a valuable tool for understanding attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

Here are some common purposes of survey research:

- Descriptive Research: Survey research is often used to describe characteristics of a population or a phenomenon. For example, a survey could be used to describe the characteristics of a particular demographic group, such as age, gender, or income.

- Exploratory Research: Survey research can be used to explore new topics or areas of research. Exploratory surveys are often used to generate hypotheses or identify potential relationships between variables.

- Explanatory Research: Survey research can be used to explain relationships between variables. For example, a survey could be used to determine whether there is a relationship between educational attainment and income.

- Evaluation Research: Survey research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a program or intervention. For example, a survey could be used to evaluate the impact of a health education program on behavior change.

- Monitoring Research: Survey research can be used to monitor trends or changes over time. For example, a survey could be used to monitor changes in attitudes towards climate change or political candidates over time.

When to use Survey Research

there are certain circumstances where survey research is particularly appropriate. Here are some situations where survey research may be useful:

- When the research question involves attitudes, beliefs, or opinions: Survey research is particularly useful for understanding attitudes, beliefs, and opinions on a particular topic. For example, a survey could be used to understand public opinion on a political issue.

- When the research question involves behaviors or experiences: Survey research can also be useful for understanding behaviors and experiences. For example, a survey could be used to understand the prevalence of a particular health behavior.

- When a large sample size is needed: Survey research allows researchers to collect data from a large number of people quickly and efficiently. This makes it a useful method when a large sample size is needed to ensure statistical validity.

- When the research question is time-sensitive: Survey research can be conducted quickly, which makes it a useful method when the research question is time-sensitive. For example, a survey could be used to understand public opinion on a breaking news story.

- When the research question involves a geographically dispersed population: Survey research can be conducted online, which makes it a useful method when the population of interest is geographically dispersed.

How to Conduct Survey Research

Conducting survey research involves several steps that need to be carefully planned and executed. Here is a general overview of the process:

- Define the research question: The first step in conducting survey research is to clearly define the research question. The research question should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the population of interest.

- Develop a survey instrument : The next step is to develop a survey instrument. This can be done using various methods, such as online survey tools or paper surveys. The survey instrument should be designed to elicit the information needed to answer the research question, and should be pre-tested with a small sample of individuals.

- Select a sample : The sample is the group of individuals who will be invited to participate in the survey. The sample should be representative of the population of interest, and the size of the sample should be sufficient to ensure statistical validity.

- Administer the survey: The survey can be administered in various ways, such as online, by mail, or in person. The method of administration should be chosen based on the population of interest and the research question.

- Analyze the data: Once the survey data is collected, it needs to be analyzed. This involves summarizing the data using statistical methods, such as frequency distributions or regression analysis.

- Draw conclusions: The final step is to draw conclusions based on the data analysis. This involves interpreting the results and answering the research question.

Advantages of Survey Research

There are several advantages to using survey research, including:

- Efficient data collection: Survey research allows researchers to collect data quickly and efficiently from a large number of people. This makes it a useful method for gathering information on a wide range of topics.

- Standardized data collection: Surveys are typically standardized, which means that all participants receive the same questions in the same order. This ensures that the data collected is consistent and reliable.

- Cost-effective: Surveys can be conducted online, by mail, or in person, which makes them a cost-effective method of data collection.

- Anonymity: Participants can remain anonymous when responding to a survey. This can encourage participants to be more honest and open in their responses.

- Easy comparison: Surveys allow for easy comparison of data between different groups or over time. This makes it possible to identify trends and patterns in the data.

- Versatility: Surveys can be used to collect data on a wide range of topics, including attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and preferences.

Limitations of Survey Research

Here are some of the main limitations of survey research:

- Limited depth: Surveys are typically designed to collect quantitative data, which means that they do not provide much depth or detail about people’s experiences or opinions. This can limit the insights that can be gained from the data.

- Potential for bias: Surveys can be affected by various biases, including selection bias, response bias, and social desirability bias. These biases can distort the results and make them less accurate.

- L imited validity: Surveys are only as valid as the questions they ask. If the questions are poorly designed or ambiguous, the results may not accurately reflect the respondents’ attitudes or behaviors.

- Limited generalizability : Survey results are only generalizable to the population from which the sample was drawn. If the sample is not representative of the population, the results may not be generalizable to the larger population.

- Limited ability to capture context: Surveys typically do not capture the context in which attitudes or behaviors occur. This can make it difficult to understand the reasons behind the responses.

- Limited ability to capture complex phenomena: Surveys are not well-suited to capture complex phenomena, such as emotions or the dynamics of interpersonal relationships.

Following is an example of a Survey Sample:

Welcome to our Survey Research Page! We value your opinions and appreciate your participation in this survey. Please answer the questions below as honestly and thoroughly as possible.

1. What is your age?

- A) Under 18

- G) 65 or older

2. What is your highest level of education completed?

- A) Less than high school

- B) High school or equivalent

- C) Some college or technical school

- D) Bachelor’s degree

- E) Graduate or professional degree

3. What is your current employment status?

- A) Employed full-time

- B) Employed part-time

- C) Self-employed

- D) Unemployed

4. How often do you use the internet per day?

- A) Less than 1 hour

- B) 1-3 hours

- C) 3-5 hours

- D) 5-7 hours

- E) More than 7 hours

5. How often do you engage in social media per day?

6. Have you ever participated in a survey research study before?

7. If you have participated in a survey research study before, how was your experience?

- A) Excellent

- E) Very poor

8. What are some of the topics that you would be interested in participating in a survey research study about?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

9. How often would you be willing to participate in survey research studies?

- A) Once a week

- B) Once a month

- C) Once every 6 months

- D) Once a year

10. Any additional comments or suggestions?

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. Your feedback is important to us and will help us improve our survey research efforts.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Survey Research: Definition, Examples and Methods

Survey Research is a quantitative research method used for collecting data from a set of respondents. It has been perhaps one of the most used methodologies in the industry for several years due to the multiple benefits and advantages that it has when collecting and analyzing data.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

In this article, you will learn everything about survey research, such as types, methods, and examples.

Survey Research Definition

Survey Research is defined as the process of conducting research using surveys that researchers send to survey respondents. The data collected from surveys is then statistically analyzed to draw meaningful research conclusions. In the 21st century, every organization’s eager to understand what their customers think about their products or services and make better business decisions. Researchers can conduct research in multiple ways, but surveys are proven to be one of the most effective and trustworthy research methods. An online survey is a method for extracting information about a significant business matter from an individual or a group of individuals. It consists of structured survey questions that motivate the participants to respond. Creditable survey research can give these businesses access to a vast information bank. Organizations in media, other companies, and even governments rely on survey research to obtain accurate data.

The traditional definition of survey research is a quantitative method for collecting information from a pool of respondents by asking multiple survey questions. This research type includes the recruitment of individuals collection, and analysis of data. It’s useful for researchers who aim to communicate new features or trends to their respondents.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis Generally, it’s the primary step towards obtaining quick information about mainstream topics and conducting more rigorous and detailed quantitative research methods like surveys/polls or qualitative research methods like focus groups/on-call interviews can follow. There are many situations where researchers can conduct research using a blend of both qualitative and quantitative strategies.

LEARN ABOUT: Survey Sampling

Survey Research Methods

Survey research methods can be derived based on two critical factors: Survey research tool and time involved in conducting research. There are three main survey research methods, divided based on the medium of conducting survey research:

- Online/ Email: Online survey research is one of the most popular survey research methods today. The survey cost involved in online survey research is extremely minimal, and the responses gathered are highly accurate.

- Phone: Survey research conducted over the telephone ( CATI survey ) can be useful in collecting data from a more extensive section of the target population. There are chances that the money invested in phone surveys will be higher than other mediums, and the time required will be higher.

- Face-to-face: Researchers conduct face-to-face in-depth interviews in situations where there is a complicated problem to solve. The response rate for this method is the highest, but it can be costly.

Further, based on the time taken, survey research can be classified into two methods:

- Longitudinal survey research: Longitudinal survey research involves conducting survey research over a continuum of time and spread across years and decades. The data collected using this survey research method from one time period to another is qualitative or quantitative. Respondent behavior, preferences, and attitudes are continuously observed over time to analyze reasons for a change in behavior or preferences. For example, suppose a researcher intends to learn about the eating habits of teenagers. In that case, he/she will follow a sample of teenagers over a considerable period to ensure that the collected information is reliable. Often, cross-sectional survey research follows a longitudinal study .

- Cross-sectional survey research: Researchers conduct a cross-sectional survey to collect insights from a target audience at a particular time interval. This survey research method is implemented in various sectors such as retail, education, healthcare, SME businesses, etc. Cross-sectional studies can either be descriptive or analytical. It is quick and helps researchers collect information in a brief period. Researchers rely on the cross-sectional survey research method in situations where descriptive analysis of a subject is required.

Survey research also is bifurcated according to the sampling methods used to form samples for research: Probability and Non-probability sampling. Every individual in a population should be considered equally to be a part of the survey research sample. Probability sampling is a sampling method in which the researcher chooses the elements based on probability theory. The are various probability research methods, such as simple random sampling , systematic sampling, cluster sampling, stratified random sampling, etc. Non-probability sampling is a sampling method where the researcher uses his/her knowledge and experience to form samples.

LEARN ABOUT: Survey Sample Sizes

The various non-probability sampling techniques are :

- Convenience sampling

- Snowball sampling

- Consecutive sampling

- Judgemental sampling

- Quota sampling

Process of implementing survey research methods:

- Decide survey questions: Brainstorm and put together valid survey questions that are grammatically and logically appropriate. Understanding the objective and expected outcomes of the survey helps a lot. There are many surveys where details of responses are not as important as gaining insights about what customers prefer from the provided options. In such situations, a researcher can include multiple-choice questions or closed-ended questions . Whereas, if researchers need to obtain details about specific issues, they can consist of open-ended questions in the questionnaire. Ideally, the surveys should include a smart balance of open-ended and closed-ended questions. Use survey questions like Likert Scale , Semantic Scale, Net Promoter Score question, etc., to avoid fence-sitting.

LEARN ABOUT: System Usability Scale

- Finalize a target audience: Send out relevant surveys as per the target audience and filter out irrelevant questions as per the requirement. The survey research will be instrumental in case the target population decides on a sample. This way, results can be according to the desired market and be generalized to the entire population.

LEARN ABOUT: Testimonial Questions

- Send out surveys via decided mediums: Distribute the surveys to the target audience and patiently wait for the feedback and comments- this is the most crucial step of the survey research. The survey needs to be scheduled, keeping in mind the nature of the target audience and its regions. Surveys can be conducted via email, embedded in a website, shared via social media, etc., to gain maximum responses.

- Analyze survey results: Analyze the feedback in real-time and identify patterns in the responses which might lead to a much-needed breakthrough for your organization. GAP, TURF Analysis , Conjoint analysis, Cross tabulation, and many such survey feedback analysis methods can be used to spot and shed light on respondent behavior. Researchers can use the results to implement corrective measures to improve customer/employee satisfaction.

Reasons to conduct survey research

The most crucial and integral reason for conducting market research using surveys is that you can collect answers regarding specific, essential questions. You can ask these questions in multiple survey formats as per the target audience and the intent of the survey. Before designing a study, every organization must figure out the objective of carrying this out so that the study can be structured, planned, and executed to perfection.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

Questions that need to be on your mind while designing a survey are:

- What is the primary aim of conducting the survey?

- How do you plan to utilize the collected survey data?

- What type of decisions do you plan to take based on the points mentioned above?

There are three critical reasons why an organization must conduct survey research.

- Understand respondent behavior to get solutions to your queries: If you’ve carefully curated a survey, the respondents will provide insights about what they like about your organization as well as suggestions for improvement. To motivate them to respond, you must be very vocal about how secure their responses will be and how you will utilize the answers. This will push them to be 100% honest about their feedback, opinions, and comments. Online surveys or mobile surveys have proved their privacy, and due to this, more and more respondents feel free to put forth their feedback through these mediums.

- Present a medium for discussion: A survey can be the perfect platform for respondents to provide criticism or applause for an organization. Important topics like product quality or quality of customer service etc., can be put on the table for discussion. A way you can do it is by including open-ended questions where the respondents can write their thoughts. This will make it easy for you to correlate your survey to what you intend to do with your product or service.

- Strategy for never-ending improvements: An organization can establish the target audience’s attributes from the pilot phase of survey research . Researchers can use the criticism and feedback received from this survey to improve the product/services. Once the company successfully makes the improvements, it can send out another survey to measure the change in feedback keeping the pilot phase the benchmark. By doing this activity, the organization can track what was effectively improved and what still needs improvement.

Survey Research Scales

There are four main scales for the measurement of variables:

- Nominal Scale: A nominal scale associates numbers with variables for mere naming or labeling, and the numbers usually have no other relevance. It is the most basic of the four levels of measurement.

- Ordinal Scale: The ordinal scale has an innate order within the variables along with labels. It establishes the rank between the variables of a scale but not the difference value between the variables.

- Interval Scale: The interval scale is a step ahead in comparison to the other two scales. Along with establishing a rank and name of variables, the scale also makes known the difference between the two variables. The only drawback is that there is no fixed start point of the scale, i.e., the actual zero value is absent.

- Ratio Scale: The ratio scale is the most advanced measurement scale, which has variables that are labeled in order and have a calculated difference between variables. In addition to what interval scale orders, this scale has a fixed starting point, i.e., the actual zero value is present.

Benefits of survey research