10 Rhetorical Situation Examples

The term ‘rhetorical situation’ is defined as “the context in which speakers or writers create discourse” (Bitzer, 1999, p. 217)

If a literacy teacher asks you to describe the rhetorical situation, they’re asking you to analyze the context of the discourse.

So, what does this mean?

Usually, it means you need to examine two things:

- The rhetorical elements used, and

- The rhetorical devices used.

I’ll summarize these below so we can jump straight to our examples, then elaborate on them toward the end of the article. Here’s the TL;DR:

Rhetorical Elements

You’ll need to examine the following elements first and foremost to demonstrate the ‘rhetorical situation’:

- Text: e.g. a books, speech, podcast, film, video, etc.

- Author: e.g. the speaker, writer, or producer of the text.

- Audience: e.g. the listener, reader, viewer, or consumer of the text.

- Purpose: e.g. why the text was produced.

- A setting: e.g. the time, location, and contextual factors (Gabrielsen, 2010).

Rhetorical Devices

These are the methods of communicating utilized in the text, including:

- Logos: the use of logic to communicate.

- Ethos: the use of authority or credibility when conveying a message.

- Pathos: the use of emotion to communicate.

These devices are based on Aristotle’s philosophy.

By examining rhetorical elements and devices, we can develop a deeper understanding of a rhetorical situation, how it works, and perhaps, why it hasn’t worked so well!

Rhetorical Situation Examples

1. steve jobs stanford speech (2005).

In 2005, Steve Jobs delivered the commencement address at Stanford University, sharing personal stories of his life and career. The speech, titled “Connecting the Dots,” has since become iconic, offering lessons on life, work, and following one’s passion. Jobs addressed a crowd of graduates, faculty, and family members, leaving a lasting impact on the audience.

To determine the rhetorical situation, let’s unpick the key elements and devices in this discourse:

- Text: The text was a commencement address, consisting of anecdotes from Jobs’ life, including dropping out of college, being fired from Apple, and facing a life-threatening illness, to convey broader life lessons.

- Author: The author was Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple Inc. and Pixar Animation Studios, known for his innovation in the technology and entertainment industries.

- Audience: The primary audience was the graduating class of Stanford University, along with faculty and families, but the speech has since reached a global audience through various media.

- Purpose: The purpose of the speech was to inspire and motivate the graduates by encouraging them to pursue their passions, face setbacks with resilience, and see opportunities in life’s challenges.

- Rhetorical Devices: Jobs employed storytelling as a major rhetorical device, using personal anecdotes to create an emotional connection (pathos) with the audience. He also established ethos through his reputation as a successful entrepreneur and innovator. The use of repetition and parallel structure helped emphasize key points and make the speech memorable.

2. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter (1997)

In 1997, J.K. Rowling released “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone,” the first book in a series that would become a global phenomenon. The novel introduced readers to a magical world filled with complex characters, intricate plots, and a battle between good and evil. The book, and the series it initiated, captivated audiences worldwide, influencing an entire generation and beyond.

- Text: The text is a fantasy novel, blending elements of magic, adventure, and coming-of-age to explore themes of friendship, courage, and the choice between good and evil.

- Author: The author, J.K. Rowling, was relatively unknown at the time but has since become one of the most successful and influential writers in modern literature.

- Audience: Initially aimed at children and young adults, the novel quickly attracted readers of all ages, transcending demographic boundaries.

- Purpose: The primary purpose was to entertain, but the novel also sought to explore deeper themes and values, such as the importance of choice, the value of friendship, and the nature of courage.

- Rhetorical Devices: Rowling used vivid imagery and detailed world-building to immerse readers in the magical universe. The use of allegory allowed for the exploration of real-world themes within a fantastical context, and character development served to engage and invest the audience in the narrative.

3. Malala Yousafzai’s UN Speech (2012)

In 2012, Malala Yousafzai, a Pakistani activist for female education, delivered a speech at the United Nations Youth Assembly, advocating for the right to education for every child. This speech came after she survived an assassination attempt by the Taliban for her activism. Her address, titled “Malala Day,” called for worldwide access to education and emphasized the power of youth.

- Text: The text was a formal speech, rich with personal anecdotes, global examples, and a call to action, focusing on the importance of education and the role of youth in enacting change.

- Author: The author, Malala Yousafzai, was a young education activist from Pakistan, who became a symbol of resilience and advocacy for girls’ education worldwide.

- Audience: The primary audience was the United Nations Youth Assembly, but the speech was also broadcast globally, reaching a diverse international audience.

- Purpose: The purpose was to advocate for universal access to education, particularly for girls, and to inspire young people to take action for change.

- Rhetorical Devices: Malala used ethos by sharing her personal experiences and challenges, pathos by evoking emotions related to the struggles of children deprived of education, and logos by presenting facts and logical arguments for universal education. The repetition of phrases like “We will continue” emphasized determination and resilience.

4. Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth (2006)

In 2006, former Vice President Al Gore released the documentary “An Inconvenient Truth,” aiming to educate the public about the reality and dangers of climate change. The film combined data, personal anecdotes, and visual imagery to present a compelling case for urgent action. It played a significant role in raising global awareness about climate change and won two Academy Awards.

- Text: The text was a documentary film, utilizing a mix of scientific data, visual graphics, personal narratives, and future projections to convey the urgency of addressing climate change.

- Author: The author and narrator of the documentary was Al Gore, former Vice President of the United States, and a long-time environmental advocate.

- Audience: The intended audience was the global public, policymakers, and anyone with a stake in the future of the planet.

- Purpose: The film aimed to raise awareness about the reality of climate change, educate the public on its consequences, and inspire individual and collective action to address it.

- Rhetorical Devices: Gore effectively used ethos, drawing on his political background and environmental advocacy. Pathos was employed through alarming visual imagery and projections of climate impact, and logos through the presentation of scientific data and facts. The juxtaposition of current realities with future projections served to emphasize the urgency of action.

5. Greta Thunberg’s UN Speech (2019)

In 2019, Greta Thunberg, a young climate activist from Sweden, addressed the United Nations Climate Action Summit, passionately urging world leaders to take immediate action against climate change. Her speech, “How Dare You,” criticized the inaction of political leaders and highlighted the urgent need for substantive change to combat environmental degradation. The address became a rallying cry for environmental activists around the world.

- Text: The text was a concise yet powerful speech, marked by emotive language, direct criticism, and a clear call for urgent and meaningful action against climate change.

- Author: The author, Greta Thunberg, was a teenage climate activist from Sweden, who gained international recognition for her Fridays for Future movement and candid advocacy for environmental protection.

- Audience: The primary audience was the world leaders and delegates at the United Nations Climate Action Summit, but the speech also reached a global audience through extensive media coverage.

- Purpose: The purpose of the speech was to hold world leaders accountable for their inaction, raise awareness about the climate crisis, and galvanize immediate and substantive action to protect the environment.

- Rhetorical Devices: Thunberg employed pathos through her passionate and emotive delivery, ethos by referencing her personal sacrifices and commitment to climate activism, and logos by citing scientific data on climate change. The repeated phrase “How dare you” served as a powerful rhetorical device to emphasize her criticism and demand accountability.

6. Facebook (2004-Now)

In 2004, Mark Zuckerberg launched Facebook, a social networking platform initially for Harvard students, which quickly expanded to other universities and eventually to the general public. Facebook’s mission was to connect people and build community, but it also raised questions about privacy, data security, and the impact on social dynamics. The platform revolutionized communication and became a subject of scrutiny and debate.

- Text: The text in this scenario is the platform itself, Facebook, which included user profiles, status updates, friend requests, and various features that allowed for online social interaction and information sharing.

- Author: The author is, well, anyone with a Facebook profile who wants to make a post!

- Audience: The initial audience was Harvard students, but it quickly expanded to include a diverse and global user base, ranging from teenagers to older adults.

- Purpose: The primary purpose of Facebook was to connect people, facilitate communication, and build online communities, but it also aimed to monetize user engagement through targeted advertising.

- Rhetorical Devices: The platform utilized user-friendly interface and features to appeal to a wide audience (ethos), incorporated real-time notifications and updates to engage users emotionally (pathos), and used algorithms and data analytics to optimize user experience and advertising (logos). The concept of “friends” and “likes” served as rhetorical devices to foster a sense of community and validation.

7. MLK’s I Have a Dream Speech (1963)

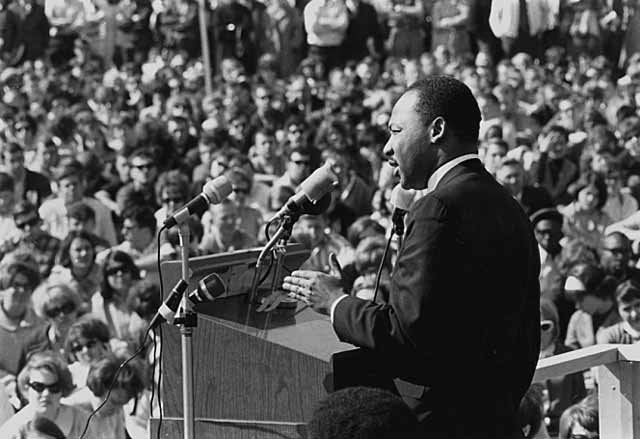

In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The speech articulated King’s vision of a future where people would not be judged by the color of their skin but by their character. This address became a defining moment in the Civil Rights Movement and a symbol of the ongoing fight for racial equality.

- Text: The text was a public speech, characterized by its rhythmic cadence, vivid imagery, and references to the American Dream, the Bible, and the U.S. Constitution.

- Author: The author, Martin Luther King Jr., was a prominent leader in the Civil Rights Movement, known for his advocacy for nonviolent resistance and racial equality.

- Audience: The immediate audience was the over 250,000 civil rights supporters present at the march, but the speech was also broadcast nationwide, reaching a much wider audience.

- Purpose: The purpose of the speech was to advocate for an end to racism and segregation, inspire hope and solidarity among civil rights supporters, and call for freedom and equality for all.

- Rhetorical Devices: King employed a range of rhetorical devices including anaphora, through the repetition of the phrase “I have a dream,” metaphors, comparing racial injustice to a “bank of injustice,” and allusions to biblical and historical texts, establishing ethos, pathos, and logos.

8. Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (1590s)

William Shakespeare’s play “Romeo and Juliet,” written in the early 1590s, is a tragic tale of two young lovers from feuding families in Verona. The play explores themes of love, fate, conflict, and death, and it has been celebrated for its exploration of the human condition and the consequences of societal discord. The timeless story has been adapted countless times across various mediums.

- Text: The text is a play, written in iambic pentameter, consisting of dialogue, soliloquies, and stage directions, exploring complex characters and universal themes.

- Author: The author, William Shakespeare, was an English playwright and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language and world literature.

- Audience: The original audience was the theatergoers of Elizabethan England, but the play has since reached a global audience and has been studied and performed worldwide.

- Purpose: The purpose of “Romeo and Juliet” was to entertain, but also to explore and reflect on human nature, societal conflict, love, and fate.

- Rhetorical Devices: Shakespeare used a variety of rhetorical devices including metaphor, simile, foreshadowing, and dramatic irony. The use of soliloquies provided insight into characters’ thoughts and motivations, and the poetic structure added rhythm and emphasis to the dialogue.

9. Churchill’s We Shall Fight on the Beaches (1944)

In 1940, Winston Churchill delivered one of his most famous speeches to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom during World War II, known as the “We Shall Fight on the Beaches” speech. The speech was a powerful call to arms, aiming to inspire the British people and maintain morale during a particularly challenging time in the war. Churchill’s words became a symbol of British resilience and determination.

- Text: The text was a wartime speech, characterized by its defiant tone, vivid imagery of defense, and the repeated assurance of Britain’s resolve to fight against Nazi Germany, regardless of the circumstances.

- Author: The author, Winston Churchill, was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, known for his leadership during World War II and his ability to inspire and unite the British people through his speeches.

- Audience: The immediate audience was the House of Commons, but the speech was also broadcast over the radio to the British public and the wider world.

- Purpose: The purpose of the speech was to bolster British morale, assure the public of the government’s commitment to victory, and demonstrate resolve to the international community.

- Rhetorical Devices: Churchill employed anaphora, with the repetition of the phrase “We shall fight,” to emphasize determination. He used vivid imagery to depict various battle scenarios, and pathos to evoke a sense of national pride and duty.

10. The US Declaration of Independence (1776)

In 1776, Thomas Jefferson penned the United States Declaration of Independence, a document that declared the thirteen American colonies independent from British rule. The text outlined the philosophical justification for independence, listed grievances against King George III, and articulated the fundamental principles that the new nation would embody. The Declaration is a foundational document of the United States and a symbol of the pursuit of liberty.

- Text: The text is a formal political document, characterized by its eloquent prose, philosophical reasoning, and clear enumeration of grievances and principles.

- Author: The principal author was Thomas Jefferson, a Founding Father and the third President of the United States, with contributions from John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston.

- Audience: The immediate audience was the British Crown, but the document was also addressed to the international community and the American people, both contemporaneous and future.

- Purpose: The purpose of the Declaration was to formally announce and justify the colonies’ decision to sever ties with Britain and to articulate the foundational principles of the new nation, including equality, liberty, and self-governance.

- Rhetorical Devices: Jefferson employed a range of rhetorical devices including parallelism, in the listing of grievances; allusion, to philosophical and Enlightenment ideas; and pathos, to evoke a sense of injustice and the desire for liberty. The famous phrase “We hold these truths to be self-evident” exemplifies the use of ethos to establish the moral grounding of the American cause.

Let’s dive deeper into the five rhetorical elements you’ll want to look at in order to explain a rhetorical istuation:

The text is the medium through which the message is conveyed.

It can take various forms, such as books, speeches, podcasts, films, videos, or digital content, each with its unique characteristics and conventions.

The nature of the text influences how the message is received and interpreted by the audience (Gabrielsen, 2010).

For instance, a speech might appeal to the audience’s emotions through tone and delivery, while a written article might rely on structured arguments and evidence (Toye, 2013). Understanding the nuances of the text is crucial for analyzing the effectiveness of the communication.

See More: A List of Text Types

The author is the originator of the message, responsible for crafting the content and delivering it to the audience.

This person utilizes their knowledge, experiences, and perspectives to shape the message, whether they are a speaker, writer, filmmaker, or content creator.

The author’s credibility, intentions, and relationship with the audience play a significant role in how the message is received (Toye, 2013). For example, a well-respected expert in a field may have more influence over an audience than an unknown individual.

Analyzing the author’s background, motivations, and biases is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the rhetorical situation.

3. Audience

The audience is the recipient of the message, whose interpretation and response are integral to the communication process.

This group can be diverse, encompassing listeners, readers, viewers, or consumers, each bringing their unique perspectives, values, and expectations to the interaction.

The audience’s background, beliefs, and context significantly influence how they perceive and react to the message (Gabrielsen, 2010; Toye, 2013).

A successful communicator must understand and consider the audience’s needs, expectations, and potential biases to effectively convey their message. The audience’s engagement and response are key indicators of the success or failure of the rhetorical situation.

See More: Examples of Intended Audiences

The purpose is the driving force behind the creation of the text, answering the question of why the message was produced.

It can range from informing, persuading, entertaining, inspiring, to challenging the audience, and it shapes the content, tone, and structure of the message (Gabrielsen, 2010).

Understanding the purpose is crucial for both the author and the audience, as it guides the creation of the message and influences how the audience interprets and responds to it (Toye, 2013).

A clear and well-defined purpose is more likely to result in effective communication and achieve the desired outcome. Analyzing the purpose provides insight into the goals of the author and the potential impact of the message.

Analyzing purpose is a particularly important media literacy skill .

The setting encompasses the time, location, and contextual factors that frame the rhetorical situation (Toye, 2013).

This includes the historical, cultural, social, and political environment in which the communication occurs.

The setting influences both the creation and reception of the message, shaping the author’s perspective and the audience’s interpretation.

For example, a speech delivered during a time of crisis may be received differently than one given in a period of stability.

Understanding the setting is essential for a holistic analysis of the rhetorical situation, providing context and background that illuminate the motivations, challenges, and implications of the communication (Gabrielsen, 2010).

Rhetorical Devices (Aristotle)

Besides elements of the text, we can also examine the text’s rhetorical devices, which are the methods employed to communicate and persuade.

Generally, we refer to Aristotle’s writings on rhetoric for this.

Here are Aristotle’s rhetorical devices:

1. Logos (Appeal to Logic)

Logos is a rhetorical device that involves the use of logical reasoning to persuade the audience. It often incorporates facts, statistics, data, and well-structured arguments to appeal to the audience’s sense of reason.

A communicator using logos will aim to present clear, concise, and coherent arguments that are supported by evidence and sound reasoning (Bitzer, 1998).

This approach is particularly effective when discussing topics that require a rational and objective perspective.

By appealing to the audience’s intellect, logos helps to establish the credibility of the argument and the reliability of the speaker or writer.

Read More: Logos Examples

2. Ethos (Appeal to Credibility)

Ethos is a rhetorical device focused on establishing the credibility and moral character of the speaker or writer.

It involves demonstrating knowledge, expertise, and a sense of ethics to gain the trust and respect of the audience.

Ethos can be established through the author’s reputation, professional background, and the way they present themselves and their arguments.

The use of appropriate language, tone, and style, as well as showing respect for differing viewpoints, contributes to building ethos (Bitzer, 1998; Rapp, 2022).

When the audience perceives the communicator as credible and trustworthy, they are more likely to be persuaded by the message.

Read More: Ethos Examples

3. Pathos (Appeal to Emotions)

Pathos appeals to the emotions, values, and desires of the audience to elicit feelings that support the speaker or writer’s argument.

It involves the use of emotive language, vivid imagery, and personal anecdotes to create an emotional response.

Pathos can be particularly effective in persuading the audience by making them feel a certain way, whether it be compassion, anger, joy, or sorrow (Bitzer, 1998).

However, it is important for pathos to be balanced with logos and ethos to ensure the argument does not become overly emotional or manipulative.

When used effectively, pathos can create a strong connection between the audience and the message, making the argument more compelling.

Read More: Pathos Examples

4. Telos (Purpose)

Telos is not traditionally listed as a rhetorical device in the same manner as logos, ethos, and pathos.

However, in a broader sense, telos refers to the purpose or goal of a rhetorical situation or a speaker’s intention in communication (Rapp, 2022). It involves considering the end purpose of the message and how it aligns with the values, expectations, and needs of the audience.

Understanding telos is crucial for both the communicator and the audience, as it provides insight into the motivations behind the message and its intended impact. A clear and well-defined telos is essential for effective communication and achieving the desired outcome.

5. Kairos (Timing)

Kairos refers to the opportune moment or the right timing in which to deliver a message. It involves considering when the audience will be most receptive and when the message will have the greatest impact.

Kairos takes into account external factors such as the cultural, social, and political climate, as well as internal factors like the audience’s mood and level of interest (Rapp, 2022).

Recognizing and seizing the opportune moment can significantly enhance the effectiveness of the message.

Kairos, therefore, emphasizes the importance of context and timing in rhetorical situations, contributing to the persuasiveness and success of the communication.

Aristotle. (2014). The Art of Rhetoric . Toronto: HarperCollins.

Bitzer, L. (1998). The Rhetorical Sitaution . In Condit, C. M., Lucaites, J. L., & Caudill, S. (Eds.). Contemporary Rhetorical Theory, First Edition. Guilford Publications.

Gabrielsen, J. (2010). The Power of Speech . Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Rapp, C. (2022). Aristotle’s Rhetoric. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2022). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/

Toye, R. (2013). Rhetoric: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 7 Key Features of 21st Century Learning

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Sociocultural Theory of Learning in the Classroom

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ The 4 Principles of Pragmatism in Education

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 17 Deep Processing Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis Essay–Examples & Template

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

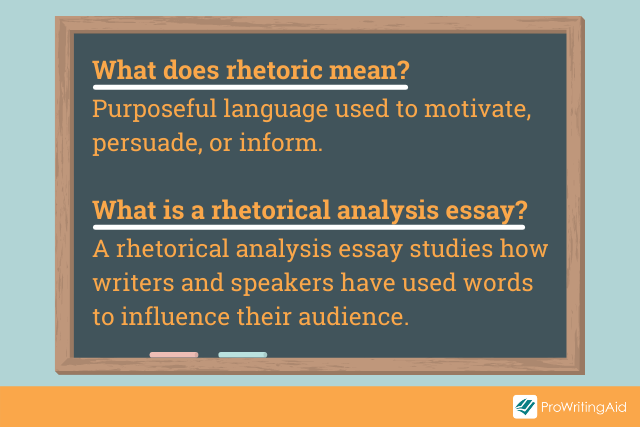

A rhetorical analysis essay is, as the name suggests, an analysis of someone else’s writing (or speech, or advert, or even cartoon) and how they use not only words but also rhetorical techniques to influence their audience in a certain way. A rhetorical analysis is less interested in what the author is saying and more in how they present it, what effect this has on their readers, whether they achieve their goals, and what approach they use to get there.

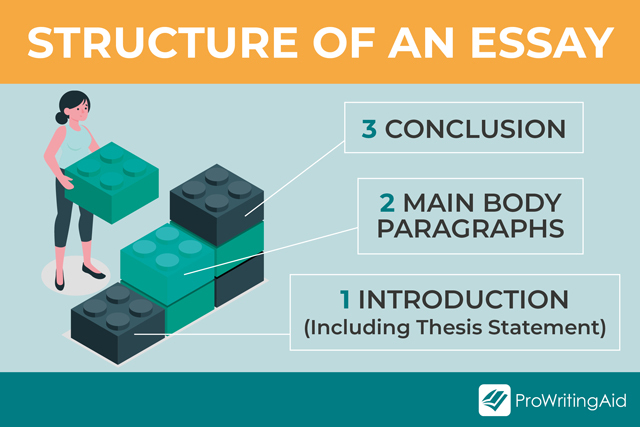

Its structure is similar to that of most essays: An Introduction presents your thesis, a Body analyzes the text you have chosen, breaks it down into sections and explains how arguments have been constructed and how each part persuades, informs, or entertains the reader, and a Conclusion section sums up your evaluation.

Note that your personal opinion on the matter is not relevant for your analysis and that you don’t state anywhere in your essay whether you agree or disagree with the stance the author takes.

In the following, we will define the key rhetorical concepts you need to write a good rhetorical analysis and give you some practical tips on where to start.

Key Rhetorical Concepts

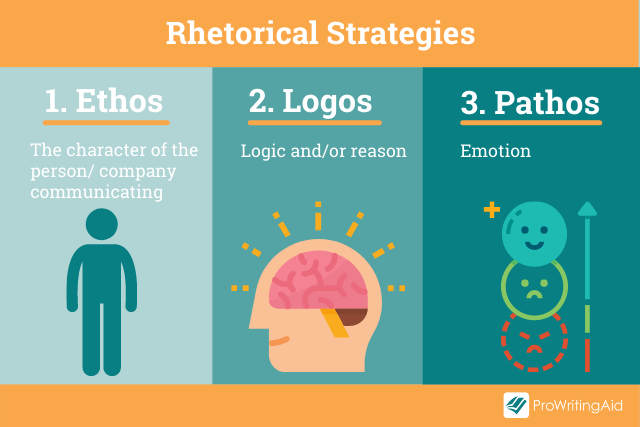

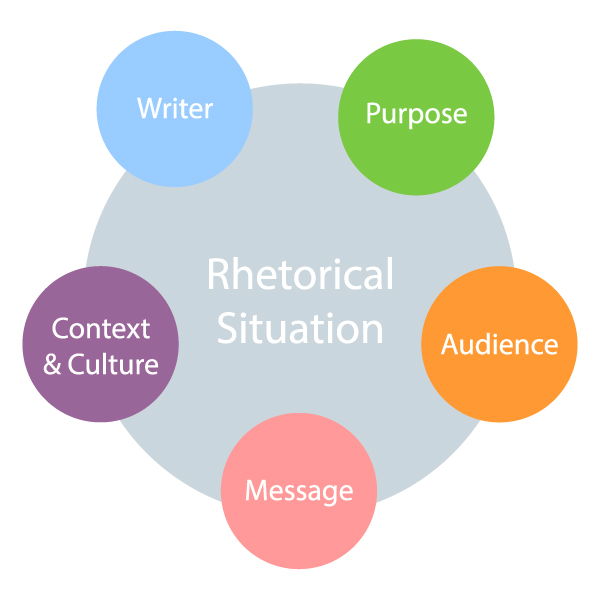

Your goal when writing a rhetorical analysis is to think about and then carefully describe how the author has designed their text so that it has the intended effect on their audience. To do that, you need to consider a number of key rhetorical strategies: Rhetorical appeals (“Ethos”, “Logos”, and “Pathos”), context, as well as claims, supports, and warrants.

Ethos, Logos, and Pathos were introduced by Aristotle, way back in the 4th century BC, as the main ways in which language can be used to persuade an audience. They still represent the basis of any rhetorical analysis and are often referred to as the “rhetorical triangle”.

These and other rhetorical techniques can all be combined to create the intended effect, and your job as the one analyzing a text is to break the writer’s arguments down and identify the concepts they are based on.

Rhetorical Appeals

Rhetorical appeal #1: ethos.

Ethos refers to the reputation or authority of the writer regarding the topic of their essay or speech and to how they use this to appeal to their audience. Just like we are more likely to buy a product from a brand or vendor we have confidence in than one we don’t know or have reason to distrust, Ethos-driven texts or speeches rely on the reputation of the author to persuade the reader or listener. When you analyze an essay, you should therefore look at how the writer establishes Ethos through rhetorical devices.

Does the author present themselves as an authority on their subject? If so, how?

Do they highlight how impeccable their own behavior is to make a moral argument?

Do they present themselves as an expert by listing their qualifications or experience to convince the reader of their opinion on something?

Rhetorical appeal #2: Pathos

The purpose of Pathos-driven rhetoric is to appeal to the reader’s emotions. A common example of pathos as a rhetorical means is adverts by charities that try to make you donate money to a “good cause”. To evoke the intended emotions in the reader, an author may use passionate language, tell personal stories, and employ vivid imagery so that the reader can imagine themselves in a certain situation and feel empathy with or anger towards others.

Rhetorical appeal #3: Logos

Logos, the “logical” appeal, uses reason to persuade. Reason and logic, supported by data, evidence, clearly defined methodology, and well-constructed arguments, are what most academic writing is based on. Emotions, those of the researcher/writer as well as those of the reader, should stay out of such academic texts, as should anyone’s reputation, beliefs, or personal opinions.

Text and Context

To analyze a piece of writing, a speech, an advertisement, or even a satirical drawing, you need to look beyond the piece of communication and take the context in which it was created and/or published into account.

Who is the person who wrote the text/drew the cartoon/designed the ad..? What audience are they trying to reach? Where was the piece published and what was happening there around that time?

A political speech, for example, can be powerful even when read decades later, but the historical context surrounding it is an important aspect of the effect it was intended to have.

Claims, Supports, and Warrants

To make any kind of argument, a writer needs to put forward specific claims, support them with data or evidence or even a moral or emotional appeal, and connect the dots logically so that the reader can follow along and agree with the points made.

The connections between statements, so-called “warrants”, follow logical reasoning but are not always clearly stated—the author simply assumes the reader understands the underlying logic, whether they present it “explicitly” or “implicitly”. Implicit warrants are commonly used in advertisements where seemingly happy people use certain products, wear certain clothes, accessories, or perfumes, or live certain lifestyles – with the connotation that, first, the product/perfume/lifestyle is what makes that person happy and, second, the reader wants to be as happy as the person in the ad. Some warrants are never clearly stated, and your job when writing a rhetorical analysis essay is therefore to identify them and bring them to light, to evaluate their validity, their effect on the reader, and the use of such means by the writer/creator.

What are the Five Rhetorical Situations?

A “rhetorical situation” refers to the circumstance behind a text or other piece of communication that arises from a given context. It explains why a rhetorical piece was created, what its purpose is, and how it was constructed to achieve its aims.

Rhetorical situations can be classified into the following five categories:

Asking such questions when you analyze a text will help you identify all the aspects that play a role in the effect it has on its audience, and will allow you to evaluate whether it achieved its aims or where it may have failed to do so.

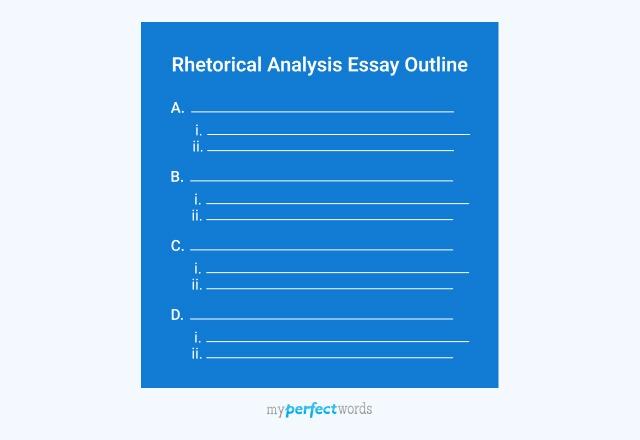

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Outline

Analyzing someone else’s work can seem like a big task, but as with every assignment or writing endeavor, you can break it down into smaller, well-defined steps that give you a practical structure to follow.

To give you an example of how the different parts of your text may look when it’s finished, we will provide you with some excerpts from this rhetorical analysis essay example (which even includes helpful comments) published on the Online Writing Lab website of Excelsior University in Albany, NY. The text that this essay analyzes is this article on why one should or shouldn’t buy an Ipad. If you want more examples so that you can build your own rhetorical analysis template, have a look at this essay on Nabokov’s Lolita and the one provided here about the “Shitty First Drafts” chapter of Anne Lamott’s writing instruction book “Bird by Bird”.

Analyzing the Text

When writing a rhetorical analysis, you don’t choose the concepts or key points you think are relevant or want to address. Rather, you carefully read the text several times asking yourself questions like those listed in the last section on rhetorical situations to identify how the text “works” and how it was written to achieve that effect.

Start with focusing on the author : What do you think was their purpose for writing the text? Do they make one principal claim and then elaborate on that? Or do they discuss different topics?

Then look at what audience they are talking to: Do they want to make a group of people take some action? Vote for someone? Donate money to a good cause? Who are these people? Is the text reaching this specific audience? Why or why not?

What tone is the author using to address their audience? Are they trying to evoke sympathy? Stir up anger? Are they writing from a personal perspective? Are they painting themselves as an authority on the topic? Are they using academic or informal language?

How does the author support their claims ? What kind of evidence are they presenting? Are they providing explicit or implicit warrants? Are these warrants valid or problematic? Is the provided evidence convincing?

Asking yourself such questions will help you identify what rhetorical devices a text uses and how well they are put together to achieve a certain aim. Remember, your own opinion and whether you agree with the author are not the point of a rhetorical analysis essay – your task is simply to take the text apart and evaluate it.

If you are still confused about how to write a rhetorical analysis essay, just follow the steps outlined below to write the different parts of your rhetorical analysis: As every other essay, it consists of an Introduction , a Body (the actual analysis), and a Conclusion .

Rhetorical Analysis Introduction

The Introduction section briefly presents the topic of the essay you are analyzing, the author, their main claims, a short summary of the work by you, and your thesis statement .

Tell the reader what the text you are going to analyze represents (e.g., historically) or why it is relevant (e.g., because it has become some kind of reference for how something is done). Describe what the author claims, asserts, or implies and what techniques they use to make their argument and persuade their audience. Finish off with your thesis statement that prepares the reader for what you are going to present in the next section – do you think that the author’s assumptions/claims/arguments were presented in a logical/appealing/powerful way and reached their audience as intended?

Have a look at an excerpt from the sample essay linked above to see what a rhetorical analysis introduction can look like. See how it introduces the author and article , the context in which it originally appeared , the main claims the author makes , and how this first paragraph ends in a clear thesis statement that the essay will then elaborate on in the following Body section:

Cory Doctorow ’s article on BoingBoing is an older review of the iPad , one of Apple’s most famous products. At the time of this article, however, the iPad was simply the latest Apple product to hit the market and was not yet so popular. Doctorow’s entire career has been entrenched in and around technology. He got his start as a CD-ROM programmer and is now a successful blogger and author. He is currently the co-editor of the BoingBoing blog on which this article was posted. One of his main points in this article comes from Doctorow’s passionate advocacy of free digital media sharing. He argues that the iPad is just another way for established technology companies to control our technological freedom and creativity . In “ Why I Won’t Buy an iPad (and Think You Shouldn’t, Either) ” published on Boing Boing in April of 2010, Cory Doctorow successfully uses his experience with technology, facts about the company Apple, and appeals to consumer needs to convince potential iPad buyers that Apple and its products, specifically the iPad, limit the digital rights of those who use them by controlling and mainstreaming the content that can be used and created on the device .

Doing the Rhetorical Analysis

The main part of your analysis is the Body , where you dissect the text in detail. Explain what methods the author uses to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience. Use Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle and the other key concepts we introduced above. Use quotations from the essay to demonstrate what you mean. Work out why the writer used a certain approach and evaluate (and again, demonstrate using the text itself) how successful they were. Evaluate the effect of each rhetorical technique you identify on the audience and judge whether the effect is in line with the author’s intentions.

To make it easy for the reader to follow your thought process, divide this part of your essay into paragraphs that each focus on one strategy or one concept , and make sure they are all necessary and contribute to the development of your argument(s).

One paragraph of this section of your essay could, for example, look like this:

One example of Doctorow’s position is his comparison of Apple’s iStore to Wal-Mart. This is an appeal to the consumer’s logic—or an appeal to logos. Doctorow wants the reader to take his comparison and consider how an all-powerful corporation like the iStore will affect them. An iPad will only allow for apps and programs purchased through the iStore to be run on it; therefore, a customer must not only purchase an iPad but also any programs he or she wishes to use. Customers cannot create their own programs or modify the hardware in any way.

As you can see, the author of this sample essay identifies and then explains to the reader how Doctorow uses the concept of Logos to appeal to his readers – not just by pointing out that he does it but by dissecting how it is done.

Rhetorical Analysis Conclusion

The conclusion section of your analysis should restate your main arguments and emphasize once more whether you think the author achieved their goal. Note that this is not the place to introduce new information—only rely on the points you have discussed in the body of your essay. End with a statement that sums up the impact the text has on its audience and maybe society as a whole:

Overall, Doctorow makes a good argument about why there are potentially many better things to drop a great deal of money on instead of the iPad. He gives some valuable information and facts that consumers should take into consideration before going out to purchase the new device. He clearly uses rhetorical tools to help make his case, and, overall, he is effective as a writer, even if, ultimately, he was ineffective in convincing the world not to buy an iPad .

Frequently Asked Questions about Rhetorical Analysis Essays

What is a rhetorical analysis essay.

A rhetorical analysis dissects a text or another piece of communication to work out and explain how it impacts its audience, how successfully it achieves its aims, and what rhetorical devices it uses to do that.

While argumentative essays usually take a stance on a certain topic and argue for it, a rhetorical analysis identifies how someone else constructs their arguments and supports their claims.

What is the correct rhetorical analysis essay format?

Like most other essays, a rhetorical analysis contains an Introduction that presents the thesis statement, a Body that analyzes the piece of communication, explains how arguments have been constructed, and illustrates how each part persuades, informs, or entertains the reader, and a Conclusion section that summarizes the results of the analysis.

What is the “rhetorical triangle”?

The rhetorical triangle was introduced by Aristotle as the main ways in which language can be used to persuade an audience: Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, Ethos to the writer’s status or authority, and Pathos to the reader’s emotions. Logos, Ethos, and Pathos can all be combined to create the intended effect, and your job as the one analyzing a text is to break the writer’s arguments down and identify what specific concepts each is based on.

Let Wordvice help you write a flawless rhetorical analysis essay!

Whether you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay as an assignment or whether it is part of an application, our professional proofreading services feature professional editors are trained subject experts that make sure your text is in line with the required format, as well as help you improve the flow and expression of your writing. Let them be your second pair of eyes so that after receiving paper editing services or essay editing services from Wordvice, you can submit your manuscript or apply to the school of your dreams with confidence.

And check out our editing services for writers (including blog editing , script editing , and book editing ) to correct your important personal or business-related work.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

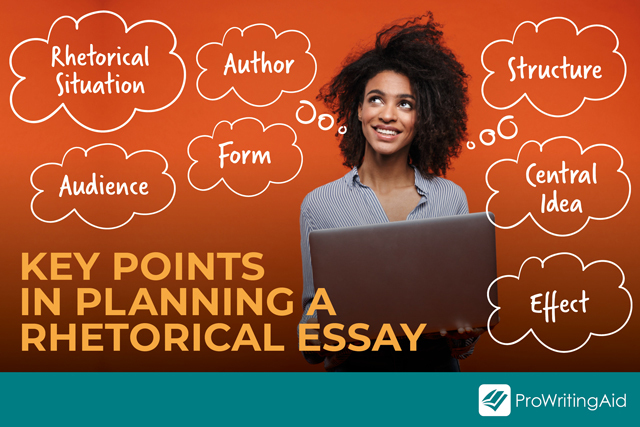

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

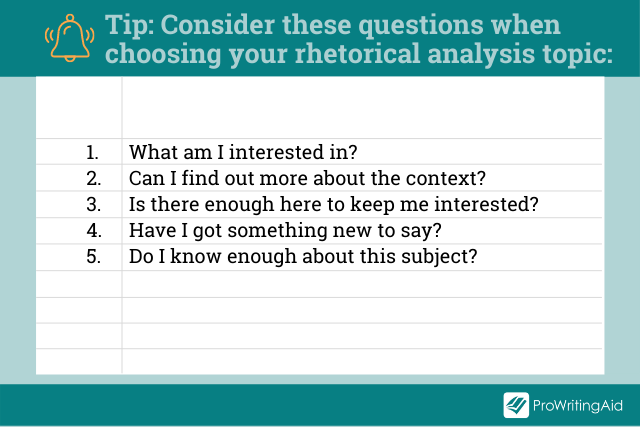

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

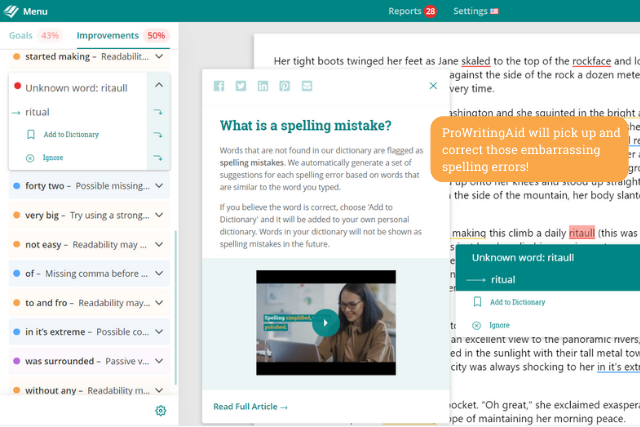

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

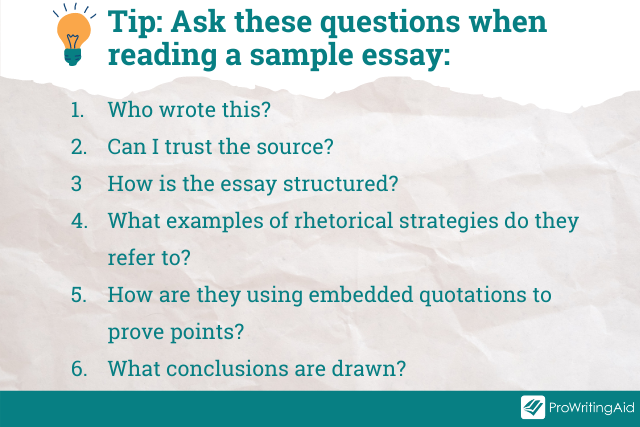

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

What is a Rhetorical Situation?

Using the Power of Language to Persuade, Inform, and Inspire

ThoughtCo / Ran Zheng

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Understanding the use of rhetoric can help you speak convincingly and write persuasively—and vice versa. At its most basic level, rhetoric is defined as communication —whether spoken or written, predetermined or extemporaneous—that’s aimed at getting your intended audience to modify their perspective based on what you’re telling them and how you’re telling it to them.

One of the most common uses of rhetoric we see is in politics. Candidates use carefully crafted language—or messaging—to appeal to their audiences’ emotions and core values in an attempt to sway their vote. However, because the purpose of rhetoric is a form of manipulation , many people have come to equate it with fabrication, with little or no regard to ethical concerns. (There’s an old joke that goes: Q: How do you know when a politician is lying? A: His lips are moving. )

While some rhetoric is certainly far from fact-based, the rhetoric itself is not the issue. Rhetoric is about making the linguistic choices that will have the most impact. The author of the rhetoric is responsible for the veracity of its content, as well as the intent—whether positive or negative—of the outcome he or she is attempting to achieve.

The History of Rhetoric

Probably the most influential pioneer in establishing the art of rhetoric itself was the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle , who defined it as “an ability, in each particular case, to see the available means of persuasion.” His treatise detailing the art of persuasion, “On Rhetoric,” dates from the 4th century BCE. Cicero and Quintilian, two of the most famous Roman teachers of rhetoric, often relied on elements culled from Aristotle’s precepts in their own work.

Aristotle explained how rhetoric functions using five core concepts: logos , ethos , pathos , kairos, and telos and much of rhetoric as we know it today is still based on these principles. In the last few centuries, the definition of “rhetoric” has shifted to encompass pretty much any situation in which people exchange ideas. Because each of us has been informed by a unique set of life circumstances, no two people see things in exactly the same way. Rhetoric has become a way not only to persuade but to use language in an attempt to create mutual understanding and facilitate consensus.

Fast Facts: Aristotle's Five Core Concepts of Rhetoric

- Logos: Often translated as “logic or reasoning,” logos originally referred to how a speech was organized and what it contained but is now more about content and structural elements of a text.

- Ethos: Ethos translates as “credibility or trustworthiness,” and refers to the character a speaker or author and how they portray themselves through words.

- Pathos: Pathos is the element of language designed to play to the emotional sensibilities of an intended audience, and geared toward using the audience’s own attitudes to incite agreement or action.

- Telos: Telos refers to the particular purpose a speaker or author hopes to achieve, even though the goals and attitude of the speaker may differ vastly from those of his or her audience.

- Kairos: Loosely translated, kairos means “setting” and deals with the time and place that a speech takes place and how that setting may influence its outcome.

Elements of a Rhetorical Situation

What exactly is a rhetorical situation ? An impassioned love letter, a prosecutor's closing statement, an advertisement hawking the next needful thing you can't possibly live without—are all examples of rhetorical situations. As different as their content and intent may be, all of them have the same five basic underlying principles:

- The text , which is the actual communication, whether written or spoken

- The author , which is the person who creates a specific communication

- The audience , who is the recipient of a communication

- The purpose(s) , which are the various reasons for authors and audiences to engage in communication

- The setting , which is the time, place, and environment that surrounds a particular communication

Each of these elements has an impact on the eventual outcome of any rhetorical situation. If a speech is poorly written, it may be impossible to persuade the audience of its validity or worth, or if its author lacks credibility or passion the result may be the same. On the other hand, even the most eloquent speaker can fail to move an audience that is firmly set in a belief system that directly contradicts the goal the author hopes to achieve and is unwilling to entertain another point of view. Finally, as the saying implies, "timing is everything." The when, where, and prevailing mood surrounding a rhetorical situation can greatly influence its eventual outcome.

While the most commonly accepted definition of a text is a written document, when it comes to rhetorical situations, a text can take on any form of communication a person intentionally creates. If you think of communication in terms of a road trip, the text is the vehicle that gets you to your desired destination—depending on the driving conditions and whether or not you have enough fuel to go the distance. There are three basic factors that have the biggest influence on the nature of any given text: the medium in which it’s delivered, the tools that are used to create it, and the tools required to decipher it:

- The Medium —Rhetorical texts can take the form of pretty much any and every kind of media that people use to communicate. A text can be a hand-written love poem; a cover letter that’s typed, or a personal dating profile that’s computer-generated. Text can encompass works in the audio, visual, spoken-word, verbal, non-verbal, graphic, pictorial, and tactile realms, to name but a few. Text can take the form of a magazine ad, a PowerPoint presentation, a satirical cartoon, a film, a painting, a sculpture, a podcast, or even your latest Facebook post, Twitter tweet, or Pinterest pin.

- The Author’s Toolkit (Creating) —The tools required to author any form of text impact its structure and content. From the very rudimentary anatomical tools humans use to produce speech (lips, mouth, teeth, tongue, and so forth) to the latest high-tech gadget, the tools we choose to create our communication can help make or break the final outcome.

- Audience Connectivity (Deciphering) —Just as an author requires tools to create, an audience must have the capability to receive and understand the information that a text communicates, whether via reading, viewing, hearing, or other forms of sensory input. Again, these tools can range from something as simple as eyes to see or ears to hear to something as complex as sophisticated as an electron microscope. In addition to physical tools, an audience often requires conceptual or intellectual tools to fully comprehend the meaning of a text. For instance, while the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise,” may be a rousing song on its musical merits alone, if you don’t speak French, the meaning and importance of the lyrics are lost.

Loosely speaking, an author is a person who creates text to communicate. Novelists, poets, copywriters, speechwriters, singer/songwriters, and graffiti artists are all authors. Each author is influenced by his or her individual background. Factors such as age, gender identification, geographic location, ethnicity, culture, religion, socio-economic condition, political beliefs, parental pressure, peer involvement, education, and personal experience create the assumptions authors use to see the world, as well as the way in which they communicate to an audience and the setting in which they are likely to do so.

The Audience

The audience is the recipient of the communication. The same factors that influence an author also influence an audience, whether that audience is a single person or a stadium crowd, the audience’s personal experiences affect how they receive communication, especially with regard to the assumptions they may make about the author, and the context in which they receive the communication.

There are as many reasons to communicate messages as there are authors creating them and audiences who may or may not wish to receive them, however, authors and audiences bring their own individual purposes to any given rhetorical situation. These purposes may be conflicting or complementary.

The authors’ purpose in communicating is generally to inform, to instruct, or to persuade. Some other author goals may include to entertain, startle, excite, sadden, enlighten, punish, console, or inspire the intended audience. The purpose of the audience to become informed, to be entertained, to form a different understanding, or to be inspired. Other audience takeaways may include excitement, consolation, anger, sadness, remorse, and so on.

As with purpose, the attitude of both the author and the audience can have a direct impact on the outcome of any rhetorical situation. Is the author rude and condescending, or funny and inclusive? Does he or she appear knowledgeable on the subject on which they’re speaking, or are they totally out of their depth? Factors such as these ultimately govern whether or not the audience understands, accepts, or appreciates the author’s text.

Likewise, audiences bring their own attitudes to the communication experience. If the communication is undecipherable, boring, or of a subject that holds no interest, the audience will likely not appreciate it. If it’s something to which they are attuned or piques their curiosity, the author’s message may be well received.

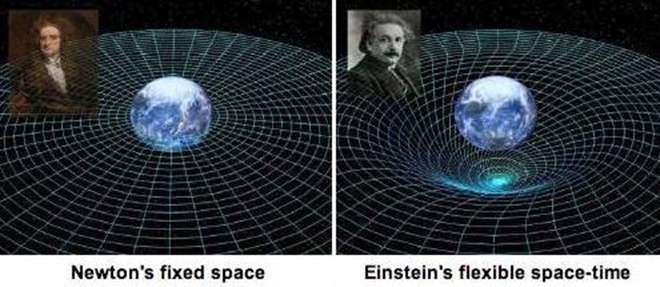

Every rhetorical situation happens in a specific setting within a specific context, and are all constrained by the time and environment in which they occur. Time, as in a specific moment in history, forms the zeitgeist of an era. Language is directly affected by both historical influence and the assumptions brought to bear by the current culture in which it exists. Theoretically, Stephen Hawking and Sir Isaac Newton could have had a fascinating conversation on the galaxy, however, the lexicon of scientific information available to each during his lifetime would likely have influenced the conclusions they reached as a result.

The specific place that an author engages his or her audience also affects the manner in which a text is both created and received. Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a Dream” speech, delivered to a rapt crowd on August 28, 1963, is considered by many as one of the most memorable pieces of American rhetoric of the 20 th century, but a setting doesn’t have to be public, or an audience large for communication to have a profound impact. Intimate settings, in which information is exchanged, such as a doctor’s office or promises are made—perhaps on a moonlit balcony—can serve as the backdrop for life-changing communication.

In some rhetorical contexts, the term “community” refers to a specific group united by like interests or concerns rather than a geographical neighborhood. Conversation, which most often refers to a dialog between a limited number of people takes on a much broader meaning to and refers to a collective conversation which encompasses a broad understanding, belief system, or assumptions that are held by the community at large.

- Constraints: Definition and Examples in Rhetoric

- Audience Analysis in Speech and Composition

- Exigence in Rhetoric

- The Implied Audience

- An Overview of Classical Rhetoric

- What Is a Message in Communication?

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- Definition of Audience

- Word Choice in English Composition and Literature

- Situated Ethos in Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Rhetorical Stance

- Definition and Examples of Paragraphing in Essays

- Common Ground in Rhetoric

- What Is a Rhetorical Device? Definition, List, Examples

- Rhetorical Move

- Rhetoric: Definitions and Observations

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 10: The Rhetorical Situation

This chapter is about the rhetorical situation . The rhetorical situation is a framework for rhetorical analysis designed for individual speeches and assessing their reception by an audience. This chapter offers a detailed explanation of the rhetorical situation and defines its core components: the exigence , the audience , and constraints . The second section of the chapter provides detailed examples of the rhetorical situation. The third section explains a related model of “situation” called the “ rhetorical ecology .” This chapter contains YouTube video content not presented in the recorded lectures.

Watching the video clips embedded in the chapters may add to the projected “read time” listed in the headers. Please also note that the audio recording for this chapter covers the same tested content as is presented in the chapter below.

Chapter Recordings

- Part 1: Defining the Rhetorical Situation (Video, ~20m)

- Part 2: Analysis of a Rhetorical Situation (Video, ~20m)

- Part 3: Rhetorical Ecologies (Video, ~12m)

Read this Next

- Palczewski, Catherine Helen, et al. “Chapter 8 Rhetorical Situations.” Rhetoric in Civic Life , Strata Pub., State College, PA, 2012, pp. 225–263.

Written Assignments

- Assignment Description for Short Paper 3: Rhetorical Analysis

Part 1: Defining the Rhetorical Situation

The rhetorical situation is a fundamental framework for understanding rhetoric as a form of persuasion , that is, as a speech or text that seeks to influence an audience’s actions. It describes rhetoric as a response to a problem or an answer to a question. Given an imperfect state of affairs, rhetoric responds or intervenes to create some change by addressing an audience. The rhetorical situation is also part of the tradition of public address scholarship. Public address may consist in the composition of eloquent speeches that are to be delivered in public settings, a studied reflection upon the geographical locations where public events have occurred in the past, or the researching of presidential correspondence, letters, or newsprint publications about former occupants of the executive branch. Public address is most aptly described as the criticism of public speech that approximates more closely a genuinely historical point of view regarding the ideas of our shared social history.

The rhetorical situation is also part of a tradition that understands rhetoric as context-dependent. Often, rhetorical scholars attribute this idea to Aristotle, who defines rhetoric as “the available means of persuasion in any given situation. “ In other words, understanding the force of a persuasive speech act relies upon a deep knowledge of the setting in which it was spoken. Aristotle also describes rhetoric’s situations in terms of three discrete genres : Forensic rhetoric is about the past and whether it did or did not happen; the traditional “situation” for forensic rhetoric was the courtroom proceeding. Epideictic, about matters of praise or blame, was speech situated in public spaces and delivered to a mass audience. Deliberative or policy-making speeches would occur in the situation of legislation and lawmaking, in service of developing a future course of action.

These three original genres of speech give the speech that is delivered in these spaces a specific function. They respond to a set of pre-defined circumstances concerning matters of fact , good and bad judgment , and policy . The rhetorical situation is an extension of this understanding. It provides us with a framework that says that speech responds to a set of pre-existing circumstances and is tailored for an audience.

According to Lloyd Bitzer, the rhetorical situation is that it is a “complex of persons, events, objects, and relations presenting an actual or potential exigence which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced in the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence.

- First, the rhetorical situation is a complex of persons, events, objects, and relations . The complex of persons includes speakers and audiences. Events include important and historic instances of speech and speech-making. Objects include the symbols gathered by speeches, what those speeches reference, and the speech’s effects. The complex relations of the situation describes the audiences it brings forth and the modes of identification it cultivates.

- Second, the rhetorical situation presents an actual or potential exigence . An exigence is “an urgency marked by imperfection.” It describes a state of discontent or emergency in which speech is an adequate response and can bring about a resolution. Exigences ultimately describe the problem that the speech must respond to.

- Third, the rhetorical situation can completely or partially remove the exigence . This means that an adequate speech makes the exigence is reversible by producing effects and audiences that are capable of addressing or effecting the change as the emergency requires.

- Fourth, the rhetorical situation introduces discourse into the situation . This means that the use or application of rhetoric can undo the emergency. A speech that will heal the situation will bring things to a resolution.

- Fifth, the speech presented in a rhetorical situation may constrain human decisions or actions . This means that a situation is rhetorical when speech resolves an emergency by steering people to act in a way that, had the speech not happened, they otherwise would not.

- Finally, the speech presented in a rhetorical situation may bring about a significant modification of the exigence . Significant modification means that the speech does something to address the problem. Ultimately, this effect of speech upon a greater exigence is what makes the situation a rhetorical one.

Key Aspects of Rhetorical Situations

- The historical context is the larger background in which a message is situated. The rhetorical situation is a subset of that field, a smaller, more defined relative of a greater historical context.

- The rhetorical situation always places three specific elements into a relationship with each other. These are the rhetorical exigence , the audience , and the constraints .

- A rhetorical exigence is an urgency marked by imperfection. It is the thing to which a speech – the rhetorical response – responds.

- A rhetorical audience is those people who have the capacity to act on the speaker’s message.

- A rhetorical constraint describes those things that limit the audience to interpret the message and steer them to act in one direction or another.

A Rhetorical Situation is not a “Context” …

A further important feature of the rhetorical situation is that it is not the same as context. This is, first of all, because every message occurs in a context, and not all contexts are rhetorical. Practically, this means that context is general, and the rhetorical situation is specific. A historical context is one in which any message can occur.

… because not all contexts are rhetorical.

A rhetorical situation is a situation that allows for a response, a speech that is capable of changing people’s minds and motivating their actions. The second reason the rhetorical situation is not the same as context is that only a rhetorical situation can invite a rhetorical response.

… because only a rhetorical situation can invite a rhetorical response.

Context is the history of an utterance, a series of motivations, occurrences, and acts that set a precedent for a public and cultural status quo . As a running example of the difference between context and situation, let’s consider the 2020 presidential impeachment hearings.

The greater context for these presidential impeachment hearings might include the 1987 Iran-Contra scandal and the 1998 impeachment hearing of Bill Clinton. Both are distant historical events in which speeches and arguments were made concerning Congress’s authority over the Executive branch. Consistently, attorneys for the President have claimed that Congress did not have the authority to investigate the President whereas Congress has claimed that authority.

The rhetorical situation for Presidential impeachment hearings in 2020 would instead be the circumstances and consequences surrounding a 2019 phone call between Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Donald Trump. The speakers and speeches generated by the impeachment trials themselves would be the “rhetoric” that responded to this situation. It would be comprised of Congressional testimony, official investigative reports, political biographies, and commentary by political pundits.

Rhetorical Response/Rhetorical Audience

Not every response to a rhetorical situation is rhetorical. Non-rhetorical responses are those that do not affect the exigency. Rhetorical responses are those that do. An emergency such as war might provoke messages that people should be afraid or display courage. Those messages can’t be separated from the emergency that occasioned it. In that sense, they are “responses” to the rhetorical situation. But not every “response” has its intended effects, and not every “response” can be directly tied back to the exigence at hand.

Below is an example of the testimony offered during the 2019 impeachment hearings instigated by the Zelensky-Trump phone conversation. The speaker is Fiona Hill, a U.S. diplomatic liaison to the Ukraine who was removed from her post just days before the phone call occurred.

A response is rhetorical when it is addressed to a rhetorical audience , that is, those auditors or listeners who have the capacity to act. Not all audiences can be rhetorical audiences. In practice, this means more people will hear the rhetorical response than can address it—only people who can act count as the rhetorical audience.

For example, consider a political speech urging young people to vote delivered by a candidate that is delivered to an audience that has a mix of high school students. However, this speech may be heard by the younger members of the crowd or people whose naturalization status prevents them from voting. If the sought-after effect of the speech is for people to vote for the candidate, then Bitzer’s theory of the rhetorical situation is limited because it only includes those with the capability to vote.

Exigence, Audience, and Constraints