Think Like a Researcher: Instruction Resources: #6 Developing Successful Research Questions

- Guide Organization

- Overall Summary

- #1 Think Like a Researcher!

- #2 How to Read a Scholarly Article

- #3 Reading for Keywords (CREDO)

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research (Alternate)

- #5 Integrating Sources

- Research Question Discussion

- #7 Avoiding Researcher Bias

- #8 Understanding the Information Cycle

- #9 Exploring Databases

- #10 Library Session

- #11 Post Library Session Activities

- Summary - Readings

- Summary - Research Journal Prompts

- Summary - Key Assignments

- Jigsaw Readings

- Permission Form

Course Learning Outcome: Develop ability to synthesize and express complex ideas; demonstrate information literacy and be able to work with evidence

Goal: Develop students’ ability to recognize and create successful research questions

Specifically, students will be able to

- identify the components of a successful research question.

- create a viable research question.

What Makes a Good Research Topic Handout

These handouts are intended to be used as a discussion generator that will help students develop a solid research topic or question. Many students start with topics that are poorly articulated, too broad, unarguable, or are socially insignificant. Each of these problems may result in a topic that is virtually un-researchable. Starting with a researchable topic is critical to writing an effective paper.

Research shows that students are much more invested in writing when they are able to choose their own topics. However, there is also research to support the notion that students are completely overwhelmed and frustrated when they are given complete freedom to write about whatever they choose. Providing some structure or topic themes that allow students to make bounded choices may be a way mitigate these competing realities.

These handouts can be modified or edited for your purposes. One can be used as a handout for students while the other can serve as a sample answer key. The document is best used as part of a process. For instance, perhaps starting with discussing the issues and potential research questions, moving on to problems and social significance but returning to proposals/solutions at a later date.

- Research Questions - Handout Key (2 pgs) This document is a condensed version of "What Makes a Good Research Topic". It serves as a key.

- Research Questions - Handout for Students (2 pgs) This document could be used with a class to discuss sample research questions (are they suitable?) and to have them start thinking about problems, social significance, and solutions for additional sample research questions.

- Research Question Discussion This tab includes materials for introduction students to research question criteria for a problem/solution essay.

Additional Resources

These documents have similarities to those above. They represent original documents and conversations about research questions from previous TRAIL trainings.

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? - Original Handout (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan. 2016 (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan 2016 with comments

Topic Selection (NCSU Libraries)

Howard, Rebecca Moore, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigues. " Writing from sources, writing from sentences ." Writing & Pedagogy 2.2 (2010): 177-192.

Research Journal

Assign after students have participated in the Developing Successful Research Topics/Questions Lesson OR have drafted a Research Proposal.

Think about your potential research question.

- What is the problem that underlies your question?

- Is the problem of social significance? Explain.

- Is your proposed solution to the problem feasible? Explain.

- Do you think there is evidence to support your solution?

Keys for Writers - Additional Resource

Keys for Writers (Raimes and Miller-Cochran) includes a section to guide students in the formation of an arguable claim (thesis). The authors advise students to avoid the following since they are not debatable.

- "a neutral statement, which gives no hint of the writer's position"

- "an announcement of the paper's broad subject"

- "a fact, which is not arguable"

- "a truism (statement that is obviously true)"

- "a personal or religious conviction that cannot be logically debated"

- "an opinion based only on your feelings"

- "a sweeping generalization" (Section 4C, pg. 52)

The book also provides examples and key points (pg. 53) for a good working thesis.

- << Previous: #5 Integrating Sources

- Next: Research Question Discussion >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:23 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/think_like_a_researcher

Research Question Examples 🧑🏻🏫

25+ Practical Examples & Ideas To Help You Get Started

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | October 2023

A well-crafted research question (or set of questions) sets the stage for a robust study and meaningful insights. But, if you’re new to research, it’s not always clear what exactly constitutes a good research question. In this post, we’ll provide you with clear examples of quality research questions across various disciplines, so that you can approach your research project with confidence!

Research Question Examples

- Psychology research questions

- Business research questions

- Education research questions

- Healthcare research questions

- Computer science research questions

Examples: Psychology

Let’s start by looking at some examples of research questions that you might encounter within the discipline of psychology.

How does sleep quality affect academic performance in university students?

This question is specific to a population (university students) and looks at a direct relationship between sleep and academic performance, both of which are quantifiable and measurable variables.

What factors contribute to the onset of anxiety disorders in adolescents?

The question narrows down the age group and focuses on identifying multiple contributing factors. There are various ways in which it could be approached from a methodological standpoint, including both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Do mindfulness techniques improve emotional well-being?

This is a focused research question aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific intervention.

How does early childhood trauma impact adult relationships?

This research question targets a clear cause-and-effect relationship over a long timescale, making it focused but comprehensive.

Is there a correlation between screen time and depression in teenagers?

This research question focuses on an in-demand current issue and a specific demographic, allowing for a focused investigation. The key variables are clearly stated within the question and can be measured and analysed (i.e., high feasibility).

Examples: Business/Management

Next, let’s look at some examples of well-articulated research questions within the business and management realm.

How do leadership styles impact employee retention?

This is an example of a strong research question because it directly looks at the effect of one variable (leadership styles) on another (employee retention), allowing from a strongly aligned methodological approach.

What role does corporate social responsibility play in consumer choice?

Current and precise, this research question can reveal how social concerns are influencing buying behaviour by way of a qualitative exploration.

Does remote work increase or decrease productivity in tech companies?

Focused on a particular industry and a hot topic, this research question could yield timely, actionable insights that would have high practical value in the real world.

How do economic downturns affect small businesses in the homebuilding industry?

Vital for policy-making, this highly specific research question aims to uncover the challenges faced by small businesses within a certain industry.

Which employee benefits have the greatest impact on job satisfaction?

By being straightforward and specific, answering this research question could provide tangible insights to employers.

Examples: Education

Next, let’s look at some potential research questions within the education, training and development domain.

How does class size affect students’ academic performance in primary schools?

This example research question targets two clearly defined variables, which can be measured and analysed relatively easily.

Do online courses result in better retention of material than traditional courses?

Timely, specific and focused, answering this research question can help inform educational policy and personal choices about learning formats.

What impact do US public school lunches have on student health?

Targeting a specific, well-defined context, the research could lead to direct changes in public health policies.

To what degree does parental involvement improve academic outcomes in secondary education in the Midwest?

This research question focuses on a specific context (secondary education in the Midwest) and has clearly defined constructs.

What are the negative effects of standardised tests on student learning within Oklahoma primary schools?

This research question has a clear focus (negative outcomes) and is narrowed into a very specific context.

Need a helping hand?

Examples: Healthcare

Shifting to a different field, let’s look at some examples of research questions within the healthcare space.

What are the most effective treatments for chronic back pain amongst UK senior males?

Specific and solution-oriented, this research question focuses on clear variables and a well-defined context (senior males within the UK).

How do different healthcare policies affect patient satisfaction in public hospitals in South Africa?

This question is has clearly defined variables and is narrowly focused in terms of context.

Which factors contribute to obesity rates in urban areas within California?

This question is focused yet broad, aiming to reveal several contributing factors for targeted interventions.

Does telemedicine provide the same perceived quality of care as in-person visits for diabetes patients?

Ideal for a qualitative study, this research question explores a single construct (perceived quality of care) within a well-defined sample (diabetes patients).

Which lifestyle factors have the greatest affect on the risk of heart disease?

This research question aims to uncover modifiable factors, offering preventive health recommendations.

Examples: Computer Science

Last but certainly not least, let’s look at a few examples of research questions within the computer science world.

What are the perceived risks of cloud-based storage systems?

Highly relevant in our digital age, this research question would align well with a qualitative interview approach to better understand what users feel the key risks of cloud storage are.

Which factors affect the energy efficiency of data centres in Ohio?

With a clear focus, this research question lays a firm foundation for a quantitative study.

How do TikTok algorithms impact user behaviour amongst new graduates?

While this research question is more open-ended, it could form the basis for a qualitative investigation.

What are the perceived risk and benefits of open-source software software within the web design industry?

Practical and straightforward, the results could guide both developers and end-users in their choices.

Remember, these are just examples…

In this post, we’ve tried to provide a wide range of research question examples to help you get a feel for what research questions look like in practice. That said, it’s important to remember that these are just examples and don’t necessarily equate to good research topics . If you’re still trying to find a topic, check out our topic megalist for inspiration.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Our Mission

Using Student-Generated Questions to Promote Deeper Thinking

Asking students to create their own questions has a powerful impact on learning. Plus, 5 tips to encourage high-quality questions.

You’ve seen a penny hundreds, if not thousands, of times. But can you draw one from memory?

In a famous decades-old study , adults were asked to draw a U.S. penny without any aids. Although they were confident that they knew what a penny looked like, their performance on the test was “remarkably poor.” And when shown pennies with slightly different characteristics, such as misplaced text or with Lincoln’s portrait facing the wrong direction, few were able to identify the inaccuracies.

It’s a maddening quirk of human memory: We’re often convinced that we know something, but upon closer examination, it’s just an illusion. And this, of course, is no surprise to teachers, who often encounter students who overestimate how well they know a topic.

Understanding how people learn and reliably commit things to memory is what prompted psychology professor Mirjam Ebersbach and her colleagues at the University of Kassel to study how students prepare for an exam, and what strategies yielded the optimal improvements in student learning.

In a recent study , Ebersbach and her research team randomly assigned 82 university students to one of three groups. In the restudy group, students simply revisited and restudied the material from a lesson in their psychology course. In the testing group, students studied the material and then took a short 10-question quiz. In the last group, students studied the same material and then created their own probing questions.

One week later, all of the students took a test on the material. Students in the restudy group scored an average of 42 percent on the test, while students in the testing and generating questions groups both scored 56 percent—an improvement of 14 percentage points, or the equivalent of a full letter grade.

“Question generation promotes a deeper elaboration of the learning content,” Ebersbach told Edutopia. “One has to reflect what one has learned and how an appropriate knowledge question can be inferred from this knowledge.”

Stronger Memory Traces

Why is generating questions so effective? Past studies reveal that learning strategies that require additional cognitive effort— retrieval practice, elaboration, concept mapping , or drawing , for example—encourage students to process the material more deeply and consider it in new contexts, generating additional memory traces that aid retention.

Yet the most commonly used strategies are also the least effective. In the study, students filled out a survey identifying the learning strategies they typically used when studying for exams. By far, they said that taking notes and restudying were their go-to strategies—a surprisingly common finding that’s been regularly reported in the research . Less than half as many mentioned practice tests, and only one student among 82 mentioned generating questions.

Passive strategies such as rereading or highlighting passages are “superficial” and may even impair long‐term retention, Ebersbach explained. “This superficial learning is promoted by the illusion of knowledge, which means that learners often have the impression after the reading of a text, for instance, that they got the messages. However, if they are asked questions related to the text (or are asked to generate questions relating to the text), they fail because they lack a deeper understanding,” she told Edutopia.

That lasting “impression” of success makes it hard to convince people that rereading and underlining are, in fact, suboptimal approaches. They register the minor benefits as major improvements and hold fast to the strategies, even when the research reveals that we’re wrong.

Getting Students to Generate Productive Questions in Class

While generating questions is an effective study strategy, it also can be adapted into a classroom activity, whether online or in person.

Here are five ideas to incorporate student-generated questions into your classroom.

Teach students how to ask good questions: At first, it can be difficult for students to generate their own questions, and many will start with simple yes/no or factual prompts. To encourage better questions, ask students to think about and focus on some of the tougher or more important concepts they encountered in the lesson, and then have them propose questions that start with “explain” or that use “how” and “why” framing. Direct your students to road-test their questions by answering them themselves: Do the questions lead to longer, more substantive answers, or can they be answered with a simple “yes” or “no”?

A bonus: Students who propose questions and then answer them to test their soundness are also relearning the materials more deeply themselves. Very sneaky.

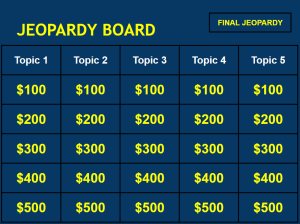

Play Jeopardy! : Research shows that active learning strategies, such as using the format of the popular game show Jeopardy! to review concepts, not only boosts student engagement but also increases academic performance. You can involve students by asking them to write the questions themselves.

To create the game, specialized software isn’t even necessary: The researchers in the study used the wiki feature in the class’s learning management system to create a 6x5 table with each cell containing a question. Similarly, you can use PowerPoint or Google Slides to create the Jeopardy! game grid. Here’s a handy template .

Have students create their own test and quiz questions: Is it cheating if students write the questions to the exam? In a 2014 study , researchers evaluated a strategy whereby students not only developed the learning materials for the class but also wrote a significant part of the exams. The result? A 10 percentage point increase in the final grade, attributed largely to an increase in student engagement and motivation. Popular tools like Kahoot and Quizlet are fun and convenient ways to create quizzes, no matter if your classroom is in person, hybrid, or virtual.

Improve class-wide discussions: In a 2018 study , students were asked to write questions based on Bloom’s taxonomy; questions ranged from lower-order true/false and multiple-choice questions to challenging questions that required analysis and synthesis. The students not only enjoyed the exercise—many called it a “rewarding experience”—but also scored 7 percentage points higher on the final exam, compared with their peers in other classes.

Use some class time to identify the characteristics of higher-order questions; then collect student questions and discuss some of the more challenging ones as a group.

Get at ‘driving questions’: For Andrew Miller, a former high school teacher and current administrator at an international pre-K–12 school, taking a page out of project-based learning and asking students to create driving questions —such as “Why do leaves have different shapes?”—not only enhances their understanding of the topic but also “creates interest and a feeling of challenge” that can draw in even the most reluctant students.

Final Summer I 2024 Application Deadline is June 2, 2024.

Click here to apply.

Featured Posts

10 AI Project Ideas for High School Students

The Warner Bros. Reach Honorship Program — Should You Apply?

10 Free Summer Programs for High School Students in NYC (New York City)

Is Applying to Tech Flex Leaders Worth It?

8 Awesome Biology Articles for High School Students

8 Medical Camps for Middle School Students

10 Graphic Design Internships for High School Students

10 Art History Summer Programs for High School Students

Everything You Need To Know About College Tours as a High School Student

MITE at UT Austin- Is it Worth it?

How to do Research in High School: Everything You Need to Know

If you are passionate about a certain subject, doing research in that field is a fantastic way to explore your interests, set the building blocks for a future career, and stand out on college applications. However, for many students, the idea of conducting research seems daunting and inaccessible while in high school and the question of where to start remains a mystery. This guide’s goal is to provide a starter for any students interested in high school research.

Research experience for high school students: Why do research?

Research is a fantastic way to delve into a field of interest. Research students at Lumiere have investigated everything, from ways to detect ocean health, new machine learning algorithms, and the artists of the 19th century. Engaging in research means you can familiarize yourself with a professional environment and develop high-level research skills early on; working with experts means you might discover things you may have never dreamed of before. You are given a valuable opportunity to think ahead and ask yourself foundational questions:

“Is this what I want in a future career?”

“What do I like and dislike about this process?”

As a huge plus (and do not underestimate the value of this!), you will likely gain extremely valuable connections, mentors, and recommenders in working closely with your team.

Let’s face it, the college selection process is becoming more and more competitive each year and admission teams are always looking for new ways to distinguish strong candidates. Doing a research project shows that you are someone with passions and, more importantly, someone with a willingness to take the extra step and explore those passions. You showcase your abilities, ambition, work ethic, eagerness to learn, and professionalism, all at the same time. This will no doubt help you when the time for college applications rolls around.

How to do research in high school: finding opportunities

Now that we’ve covered the ‘why’, let’s cover the ‘how’! There are two ways you can go about this, and it’s a great idea to run these in parallel so that one can serve as a backup for the other.

1. Identify research opportunities and apply strategically: Some opportunities are recurring programs. Usually, these are advertised. These can be structured research programs or internships run by universities, non-profits or government departments.

Organization and preparation were key to my own application processes, so be sure to start thinking ahead. Note that most research programs take place in the summer and require applications that are due by January or February. Make a spreadsheet of programs you’d be interested in and take note of their application deadlines, cost, required materials, etc. Applications often have you write essays and submit recommendation letters, so you want to think about those in advance as well.

2. Cold email to find research opportunities that are not advertised: Another way to pursue research outside of the programs is to try contacting people directly and get involved in their research projects. This would mainly involve university faculty, but you might also find a mentor elsewhere; for instance, if you are interested in medical work, you could contact someone at your local hospital. If you are interested in government, you might reach out to your local representative. If you don’t have any personal connections with faculty members in your field, cold emailing them is the way to go. You’ll need to email a lot of researchers; chances are some are busy, some aren’t in need of interns, and some simply don’t check their emails. To up your chances, you should try reaching out to at least 25 people of interest.

For cold emailing, you’ll be asking for opportunities that may not be advertised. You’ll need to prepare an “email template” of sorts that you’ll be sending out to everyone. It should start with an introduction—who are you, where are you from, how do you know this person—and include a set of your skills and interests that you could bring to the table. Keep this email short, friendly and to the point. Don’t be afraid to follow-up if they don’t respond within the first two weeks! Your message might have just gotten lost in their inbox. You’ll also want to update your resumé to attach to the email be sure to include any relevant coursework, accomplishments, and experience in the field.

Types of research opportunities for high school students

1. do a structured research program in high school.

Structured research programs are excellent ways to gain experience under some top researchers and university faculty, and often include stays at actual labs or college campuses with a wide variety of peers, mentors, and faculty. Examples of some competitive research programs include Research Science Institute (RSI) hosted by MIT, the Summer Academy for Math and Science (SAMS) offered by Carnegie Mellon, and a program hosted by the Baker Institute at Rice University for students interested in political science. For more options, here’s a list of 24 programs for this upcoming summer that we’ve compiled for you!

Another great way of deep-diving into an area of your interest and doing university-level research is through 1-1 mentorship.

Lumiere Research Scholar Program

Founded by Harvard and Oxford researchers, Lumiere offers its own structured research programs in which ambitious high school students work 1-1 with top PhDs and develop and independent research paper.

Students have had the opportunity to work on customized research projects across STEM, social sciences, AI and business. Lumiere’s growing network of mentors currently has over 700, carefully selected PhDs from top universities who are passionate about leading the next generation of researchers. The program is fully virtual! You can find the application form here .

Also check out the Lumiere Research inclusion Foundation , a non-profit research program for talented, low-income students.

Veritas AI’s Summer Fellowship Program

Veritas AI has a range of AI programs for ambitious high school students , starting from close-group, collaborative learning to customized project pathways with 1:1 mentorship . The programs have been designed and run by Harvard graduate students & alumni.

In the AI Fellowship, you will create a novel AI project independently with the support of a mentor over 12-15 weeks. Examples of past projects can be found here .

Apply now !

2. Work with a professor in high school

Research typically asks for an advisor, professional, or mentor. So how does someone end up doing research with a researcher in high school? The very first thing you need to do is identify an area of interest. If you really enjoy biology at school, perfect. If you find history fascinating, you’ve found your topic. The important thing is that you’re truly interested in this area; any discipline is fair game!

3. Participate in competitions and fairs

There are many research competitions and fairs available for high school students to participate in. For example, the Davidson Institute offers cash scholarships for student projects in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, literature, music, or philosophy. The Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair is a particularly well-known competition for students who have completed independent research projects. Research fairs are a great way to motivate students in pursuing their own interests, showing initiative and drive. Winning a competition also looks great on a resumé! Check out Lumiere’s guide to research competitions here .

4. Pursue your own passion projects

A passion project can mean more than just a presentation made for competition. For example, a student I know created an app to track music trends at our school and then analyzed the data on his own—just for fun! It was a great story to include on his future internship applications. Take a look at Lumiere’s guide for passion projects here .

5. Write a research paper

Once you’ve pursued your own research project, writing a research paper is a next great step. This way, you have a writing sample you’ll be able to send to colleges as an additional supplement, or to labs and researchers for future opportunities. It’s also a fantastic exercise in writing. We know that many high school students might struggle with learning how to write a research paper on their own. This is something you might work with your high school science teacher on, or with the guidance of a Lumiere mentor.

6. Research internships

These can be standalone or part of a research program. In looking for a more structured research experience, a research internship can be particularly valuable in building strong foundations in research. There are always tons of internship opportunities available in all different fields, some as specific as medical research . If you are wondering how to get a research internship in high school, then check out our blog posts and apply!

Things to keep in mind when working with a researcher.

You’ve gotten into a research program! Now you want to do the best job possible. There are a few things to keep in mind while conducting research.

1. Maintain a professional and friendly demeanor

Chances are, there are many things you don’t know or haven’t learned about this field. The important thing is to keep an open mind and remain eager to learn. Don’t be afraid to ask questions or to offer to help with anything, even if it’s not in your job description. Your mentor will appreciate your willingness to adapt, follow procedures, and engage with challenging material.

2. Keep track of what’s happening

Open up your notes app or get a small journal to remember what has happened in each step of the process. I remember the hardest part of writing my college essays was the very beginning: trying to come up with a list of memorable moments to talk about. If you’re looking to write about your research experience in your college application, you need to remember the moments where you struggled, where you learned, where you almost gave up but didn’t, where you realized something, even the moment you first stepped into the lab! If you are given feedback: write that down! If you are asked to reflect on everything you learned: write that down! This will be incredibly important for now and for later.

3. Ask questions

Not only is your mentor there as a potential future recommender, but they are also there to help you learn as much as possible. Absorb as much as you can from them! Ask as many questions as you can about their career, their previous research, their education, their own moments of realization, etc. This will help you discover what this career really entails and what you might look for in navigating your own future career.

Making the most out of your research: How to publish a research paper in high school

A question we often get is whether or not you need to publish your research for you to mention it in your college application. While the answer is no, the experience is a great one to have and definitely allows your work to stand out amongst your peers. Lumiere has published a complete guide to publishing research in high school here . What’s important to keep in mind is that there are various journals that specifically accept high school research reports and papers, such as the Concord Review or the Journal of Emerging Investigators. In our articles below, we go through a detailed guide of what these journals are and how a student might best approach the submission process.

Useful guides for publishing a research paper in high school

The Concord Review: The Complete Guide To Getting In (lumiere-education.com)

The John Locke Essay Competition

The Complete Guide to the Journal of Emerging Investigators (lumiere-education.com)

Research is an incredibly rewarding learning experience for everyone. While high school may seem early, it’s always better to start sooner rather than later, both for your college applications and for your own personal progress. Although the process may seem daunting at first, we hope we’ve broken it down in a way that’s simple and digestible. And if you want extra support, the Lumiere Research Scholar Program is always here to help!

Amelia is a current junior at Harvard College studying art history with a minor in economics. She’s enthusiastic about music, movies, and writing, and is excited to help Lumiere’s students as much as she can!

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

100 Interesting Research Paper Topics for High Schoolers

What’s covered:, how to pick the right research topic, elements of a strong research paper.

- Interesting Research Paper Topics

Composing a research paper can be a daunting task for first-time writers. In addition to making sure you’re using concise language and your thoughts are organized clearly, you need to find a topic that draws the reader in.

CollegeVine is here to help you brainstorm creative topics! Below are 100 interesting research paper topics that will help you engage with your project and keep you motivated until you’ve typed the final period.

A research paper is similar to an academic essay but more lengthy and requires more research. This added length and depth is bittersweet: although a research paper is more work, you can create a more nuanced argument, and learn more about your topic. Research papers are a demonstration of your research ability and your ability to formulate a convincing argument. How well you’re able to engage with the sources and make original contributions will determine the strength of your paper.

You can’t have a good research paper without a good research paper topic. “Good” is subjective, and different students will find different topics interesting. What’s important is that you find a topic that makes you want to find out more and make a convincing argument. Maybe you’ll be so interested that you’ll want to take it further and investigate some detail in even greater depth!

For example, last year over 4000 students applied for 500 spots in the Lumiere Research Scholar Program , a rigorous research program founded by Harvard researchers. The program pairs high-school students with Ph.D. mentors to work 1-on-1 on an independent research project . The program actually does not require you to have a research topic in mind when you apply, but pro tip: the more specific you can be the more likely you are to get in!

Introduction

The introduction to a research paper serves two critical functions: it conveys the topic of the paper and illustrates how you will address it. A strong introduction will also pique the interest of the reader and make them excited to read more. Selecting a research paper topic that is meaningful, interesting, and fascinates you is an excellent first step toward creating an engaging paper that people will want to read.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is technically part of the introduction—generally the last sentence of it—but is so important that it merits a section of its own. The thesis statement is a declarative sentence that tells the reader what the paper is about. A strong thesis statement serves three purposes: present the topic of the paper, deliver a clear opinion on the topic, and summarize the points the paper will cover.

An example of a good thesis statement of diversity in the workforce is:

Diversity in the workplace is not just a moral imperative but also a strategic advantage for businesses, as it fosters innovation, enhances creativity, improves decision-making, and enables companies to better understand and connect with a diverse customer base.

The body is the largest section of a research paper. It’s here where you support your thesis, present your facts and research, and persuade the reader.

Each paragraph in the body of a research paper should have its own idea. The idea is presented, generally in the first sentence of the paragraph, by a topic sentence. The topic sentence acts similarly to the thesis statement, only on a smaller scale, and every sentence in the paragraph with it supports the idea it conveys.

An example of a topic sentence on how diversity in the workplace fosters innovation is:

Diversity in the workplace fosters innovation by bringing together individuals with different backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences, which stimulates creativity, encourages new ideas, and leads to the development of innovative solutions to complex problems.

The body of an engaging research paper flows smoothly from one idea to the next. Create an outline before writing and order your ideas so that each idea logically leads to another.

The conclusion of a research paper should summarize your thesis and reinforce your argument. It’s common to restate the thesis in the conclusion of a research paper.

For example, a conclusion for a paper about diversity in the workforce is:

In conclusion, diversity in the workplace is vital to success in the modern business world. By embracing diversity, companies can tap into the full potential of their workforce, promote creativity and innovation, and better connect with a diverse customer base, ultimately leading to greater success and a more prosperous future for all.

Reference Page

The reference page is normally found at the end of a research paper. It provides proof that you did research using credible sources, properly credits the originators of information, and prevents plagiarism.

There are a number of different formats of reference pages, including APA, MLA, and Chicago. Make sure to format your reference page in your teacher’s preferred style.

- Analyze the benefits of diversity in education.

- Are charter schools useful for the national education system?

- How has modern technology changed teaching?

- Discuss the pros and cons of standardized testing.

- What are the benefits of a gap year between high school and college?

- What funding allocations give the most benefit to students?

- Does homeschooling set students up for success?

- Should universities/high schools require students to be vaccinated?

- What effect does rising college tuition have on high schoolers?

- Do students perform better in same-sex schools?

- Discuss and analyze the impacts of a famous musician on pop music.

- How has pop music evolved over the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of women in music changed in the media over the past decade?

- How does a synthesizer work?

- How has music evolved to feature different instruments/voices?

- How has sound effect technology changed the music industry?

- Analyze the benefits of music education in high schools.

- Are rehabilitation centers more effective than prisons?

- Are congestion taxes useful?

- Does affirmative action help minorities?

- Can a capitalist system effectively reduce inequality?

- Is a three-branch government system effective?

- What causes polarization in today’s politics?

- Is the U.S. government racially unbiased?

- Choose a historical invention and discuss its impact on society today.

- Choose a famous historical leader who lost power—what led to their eventual downfall?

- How has your country evolved over the past century?

- What historical event has had the largest effect on the U.S.?

- Has the government’s response to national disasters improved or declined throughout history?

- Discuss the history of the American occupation of Iraq.

- Explain the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

- Is literature relevant in modern society?

- Discuss how fiction can be used for propaganda.

- How does literature teach and inform about society?

- Explain the influence of children’s literature on adulthood.

- How has literature addressed homosexuality?

- Does the media portray minorities realistically?

- Does the media reinforce stereotypes?

- Why have podcasts become so popular?

- Will streaming end traditional television?

- What is a patriot?

- What are the pros and cons of global citizenship?

- What are the causes and effects of bullying?

- Why has the divorce rate in the U.S. been declining in recent years?

- Is it more important to follow social norms or religion?

- What are the responsible limits on abortion, if any?

- How does an MRI machine work?

- Would the U.S. benefit from socialized healthcare?

- Elderly populations

- The education system

- State tax bases

- How do anti-vaxxers affect the health of the country?

- Analyze the costs and benefits of diet culture.

- Should companies allow employees to exercise on company time?

- What is an adequate amount of exercise for an adult per week/per month/per day?

- Discuss the effects of the obesity epidemic on American society.

- Are students smarter since the advent of the internet?

- What departures has the internet made from its original design?

- Has digital downloading helped the music industry?

- Discuss the benefits and costs of stricter internet censorship.

- Analyze the effects of the internet on the paper news industry.

- What would happen if the internet went out?

- How will artificial intelligence (AI) change our lives?

- What are the pros and cons of cryptocurrency?

- How has social media affected the way people relate with each other?

- Should social media have an age restriction?

- Discuss the importance of source software.

- What is more relevant in today’s world: mobile apps or websites?

- How will fully autonomous vehicles change our lives?

- How is text messaging affecting teen literacy?

Mental Health

- What are the benefits of daily exercise?

- How has social media affected people’s mental health?

- What things contribute to poor mental and physical health?

- Analyze how mental health is talked about in pop culture.

- Discuss the pros and cons of more counselors in high schools.

- How does stress affect the body?

- How do emotional support animals help people?

- What are black holes?

- Discuss the biggest successes and failures of the EPA.

- How has the Flint water crisis affected life in Michigan?

- Can science help save endangered species?

- Is the development of an anti-cancer vaccine possible?

Environment

- What are the effects of deforestation on climate change?

- Is climate change reversible?

- How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect global warming and climate change?

- Are carbon credits effective for offsetting emissions or just marketing?

- Is nuclear power a safe alternative to fossil fuels?

- Are hybrid vehicles helping to control pollution in the atmosphere?

- How is plastic waste harming the environment?

- Is entrepreneurism a trait people are born with or something they learn?

- How much more should CEOs make than their average employee?

- Can you start a business without money?

- Should the U.S. raise the minimum wage?

- Discuss how happy employees benefit businesses.

- How important is branding for a business?

- Discuss the ease, or difficulty, of landing a job today.

- What is the economic impact of sporting events?

- Are professional athletes overpaid?

- Should male and female athletes receive equal pay?

- What is a fair and equitable way for transgender athletes to compete in high school sports?

- What are the benefits of playing team sports?

- What is the most corrupt professional sport?

Where to Get More Research Paper Topic Ideas

If you need more help brainstorming topics, especially those that are personalized to your interests, you can use CollegeVine’s free AI tutor, Ivy . Ivy can help you come up with original research topic ideas, and she can also help with the rest of your homework, from math to languages.

Disclaimer: This post includes content sponsored by Lumiere Education.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Open access

- Published: 06 September 2016

Promoting the asking of research questions in a high-school biotechnology inquiry-oriented program

- Tom Bielik 1 &

- Anat Yarden ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3948-9400 1

International Journal of STEM Education volume 3 , Article number: 15 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

6306 Accesses

10 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Asking questions is an important scientific practice, and students around the world are expected to learn how to ask their own research questions while performing inquiry. In contrast to authentic scientific inquiry, in most simple inquiry tasks that are carried out in schools, the research questions are given to the students. Here, we characterized the teaching and learning of research-question-asking in the context of an innovative inquiry-oriented program for high-school biotechnology majors, focusing on two case studies of lessons in which students were expected to formulate their research questions.

In-depth examination of students’ questions, written during the two lessons, revealed that only in one of the lessons students’ ability to ask research questions improved. A connection was found between the more student-centered, dialogic, and interactive teaching strategy and the development of students’ ability to ask research questions in that class. Most of the research questions that were investigated by the students originated from a peer-critique activity during the student-centered lesson, unlike the teacher-focused lesson from which none of the students’ suggested research questions were selected for investigation.

Conclusions

It can be concluded that a student-centered, dialogic, and interactive teaching strategy may contribute to the development of students’ ability to ask research questions in an inquiry-oriented high-school program. Encouraging teachers to implement dialogic and interactive classroom discourse in authentic inquiry could be a meaningful tool to support the teaching and learning of scientific abilities such as asking research questions.

Asking questions is considered a crucial component in developing scientific literacy, as emphasized in various policy documents worldwide (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA] 2012 ; European Commission 2007 ; National Research Council [NRC] 2012 ; United Kingdom Department of Education 2013 ). Students’ questions play an important role in promoting their scientific habits of mind and their understanding of scientific knowledge (Chin and Osborne 2008 ). Students are expected to ask their own research questions while participating in inquiry learning (Lombard and Schneider 2013 ), and teachers are expected to teach their students to ask research questions that are feasible for investigations, by providing them with inquiry environments that encourage asking research questions (Hartford and Good 1982 ). The teacher’s assistance is required in scaffolding students’ learning, transforming their questions into research questions that are appropriate for authentic scientific inquiry (Wayne Allison and Shrigley 1986 ). However, in most simple inquiry tasks that are carried out in schools, the research questions are given to the students, in contrast to authentic scientific inquiry, where scientists are expected to develop and explore their own research questions (Chinn and Malhotra 2002 ). In light of the need for a better understanding of the processes contributing to the development of students’ ability to ask research questions, we explored the teaching and learning of this ability in an innovative inquiry-oriented program entitled Bio-Tech. We demonstrate that a student-centered teaching strategy that includes a peer-critique activity during the lesson on how to ask research questions improved students’ ability to formulate research questions that are appropriate for investigation in the Bio-Tech program.

Inquiry-based science teaching

Engaging students in scientific inquiry is one of the principal goals of science education, recommended by researchers and in various policy documents (Bybee 2000 ; European Commission 2007 ; National Research Council [NRC] 1996 , 2000 ).

One of the commonly accepted definitions of scientific inquiry is the one published in the National Research Council (NRC) ( 1996 ): “Scientific inquiry refers to the diverse ways in which scientists study the natural world and propose explanations based on the evidence derived from their work. Inquiry also refers to the activities of students in which they develop knowledge and understanding of scientific ideas, as well as an understanding of how scientists study the natural world” (p. 23). The NRC further elaborates on the components of scientific inquiry: “Inquiry is a multifaceted activity that involves making observations; posing questions; examining books and other sources of information to see what is already known; planning investigations; reviewing what is already known in light of experimental evidence; using tools to gather, analyze, and interpret data; proposing answers, explanations, and predictions; and communicating the results. Inquiry requires identification of assumptions, use of critical and logical thinking, and consideration of alternative explanations” (p. 26). We base the research presented in this article on the above definition of inquiry.

The NRC ( 2000 ) suggests five features that best define the teaching and learning of inquiry. Engaging in scientifically oriented questions is one of these features. Asking questions is also one of the eight crucial scientific practices suggested in the recent framework for K-12 science education (NRC 2012 ). Students around the world are required to learn about and gain an understanding of the inquiry process and develop their understanding of scientific practices by experiencing authentic inquiry in an active learning environment (Abd-El-Khalick et al. 2004 ; Bybee 2000 ; European Commission 2007 ; National Research Council [NRC] 1996 ). By practicing inquiry, students are expected to cultivate scientific habits of mind, practice logical scientific reasoning, develop critical thinking abilities in a scientific context, and experience meaningful learning of scientific concepts and processes (Chinn and Malhotra 2002 ; Harlen 2004 ; Hmelo-Silver et al. 2007 ). However, a debate still exists regarding the goals, methods, and strategies used to incorporate inquiry into the science-education classroom (European Commission 2007 ; Tamir 2006 ; Windschitl et al. 2008 ), and many issues remain unclear regarding the learning goals and suitable strategies for teaching scientific inquiry (Furtak et al. 2012 ; Minner et al. 2010 ).

Asking research questions

Asking questions is a core scientific practice required for gaining scientific literacy and developing students’ critical thinking and their understanding of the inquiry process (Cuccio-Schirripa and Steiner 2000 ; Dori and Herscovitz 1999 ; Hartford and Good 1982 ; National Research Council [NRC] 2012 ; Pedrosa-de-Jesus et al. 2012 ). The goals of teaching how to ask questions are to direct students’ knowledge construction, foster communication, help them self-evaluate their understanding, and increase their motivation and curiosity (Chin and Osborne 2008 ). Asking questions is an integral part of the practice of critiquing, which is important for developing students’ scientific literacy (Henderson et al. 2015 ).

Research questions, also termed researchable questions (Chin and Kayalvizhi 2002 ; Cuccio-Schirripa and Steiner 2000 ), investigable questions (Chin, 2002 ), or operational questions (Wayne Allison and Shrigley 1986 ), are questions that call for hands-on, manipulative, operational actions and can lead to a process of collecting data to answer them (Hartford and Good 1982 ). Research questions should be meaningful, interesting, and challenging for the students, providing them with opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and abilities and also encouraging them to exercise their critical and creative thinking (Chin and Kayalvizhi 2002 ). To answer the research questions, they must be appropriate to the student’s cognitive developmental level and the procedures should be accessible and manageable to the student (Keys 1998 ). Students’ research questions should be investigable within the limitations of time and materials. The inquiry process that is required to answer research questions should not be too expensive, complicated, or dangerous to perform (Chin and Kayalvizhi 2002 ). Furthermore, research questions should lead to genuine exploration and discovery of previously unknown knowledge (Cuccio-Schirripa and Steiner 2000 ).

Students are expected to ask their own research questions while participating in scientific inquiry (Cuccio-Schirripa and Steiner 2000 ). These questions should help students progress to the next stages of the inquiry process (Chin 2002 ) and develop their procedural and conceptual knowledge (Chin and Brown 2002 ). Students are expected to formulate their own research questions during their school science learning (National Research Council [NRC] 2007 ). In addition, students should be able to distinguish between research questions and other types of questions and to refine their empirical questions that lead to open investigations (National Research Council [NRC] 2000 ). Harris et al. ( 2012 ) investigated fifth-grade teachers’ instructional moves and teaching strategies while teaching students how to ask research questions. They found that although the teachers displayed a student-centered and dialogic approach, they experienced challenges in developing their students’ ideas into investigable questions. Lombard and Schneider ( 2013 ) found that high-school biology majors’ ability to write research questions appropriate for investigation improved while maintaining their ownership of the inquiry process. Some of the students’ ability to write appropriate research questions was achieved by employing structured teacher guidance while engaging students in peer discussions (Lombard and Schneider 2013 ). Considering the above, there is a need to explore means of promoting the learning of how to ask research questions in science classrooms. This study aims to explore the development of students’ ability to ask research questions while participating in an inquiry-oriented program.

Classroom discourse and communicative approach

Examining classroom discourse is a powerful tool for evaluating the development of students’ scientific understanding and abilities (Osborne 2010 ; Pimentel and McNeill 2013 ). The discourse that is carried out in most secondary science classrooms is teacher-centered (Newton et al. 1999 ), as it is difficult for teachers to shift from the traditional teacher-centered instruction to more student-centered discursive teaching strategies (Jimenez-Aleixandre et al. 2000 ; Lemke 1990 ).

One of the methods of investigating classroom discourse is the communicative approach. The communicative approach analytical framework was developed by Mortimer and Scott ( 2003 ) to examine and classify types of classroom discourse. This approach focuses on the teacher–student interactions that serve to develop students’ ideas and understanding in the classroom. The framework is based on sociocultural principles, according to which individual learning and understanding is influenced by the social interaction context (Scott 1998 ; Vygotsky 1978 ) and the role of language during classroom talk (Lemke 1990 ).

Central to the communicative approach are the dialogic/authoritative and interactive/non-interactive dimensions. The dialogic/authoritative dimension determines whether the teacher acts as a transmitter of knowledge embodied in one scientific meaning or adopts a dialogic instruction that encourages exploration of different views and ideas to develop shared meaning of new knowledge (Scott 1998 ). In an authoritative discourse, the discussion is “closed” to other voices, having a fixed intent and controlled outcome. In a dialogic discourse, the teacher encourages the students to express their ideas and debate their points of view. The discussion is “open” and may include several different views. The intent of the dialogic discourse is generative, and the outcome is unknown. Scott et al. ( 2006 ) suggested that there is a necessary tension during classroom discourse between the authoritative and dialogic dimensions. The teachers may shift between approaches, according to their teaching purposes and goals (Scott et al. 2006 ). The interactive/non-interactive dimension determines the students’ involvement level during the discourse. In interactive discourse, many students participate in the discussion, whereas in non-interactive discourse, the number of students participating in the discussion is limited to one or a very few.

The communicative approach examines the patterns of interaction during classroom discourse. These are represented by the triadic dialog, comprised of the Initiation-Response-Evaluation (I-R-E) structure (Mehan 1979 ). According to this pattern, each dialogic sequence usually starts with teacher initiation (mostly in the form of a question); this is followed by a response from a student (an answer to the question), and the sequence closes with a teacher evaluation of the response. This short and closed-chain triadic sequence dominates most teacher-centered classroom discourse and is very common in high-school classrooms (Lemke 1990 ; Scott et al. 2006 ). Mortimer and Scott ( 2003 ) suggested that interactive discourse is characterized by long and open non-triadic patterns, in which the teacher refrains from immediate evaluation of the student’s response and instead may prompt the students to further elaborate on their ideas or encourage other students to critique their ideas.

The discursive moves used by the teacher during the lesson are pivotal in navigating the classroom discussion and promoting meaningful discourse (Pimentel and McNeill 2013 ), as well as for providing collaborative feedback (Gan Joo Seng and Hill 2014 ). Among the various teacher moves, teachers’ questions play an important role in students’ learning, as they scaffold students’ thinking and understanding and encourage their involvement in the classroom discourse (Chin 2007 ; Kawalkar and Vijapurkar 2011 ). One way of classifying teachers’ questions is as open or closed. Open questions, in which the teacher probes for students’ ideas without expecting a specific known answer, promote dialogic discourse and increase students’ involvement in the discussion. In contrast, closed questions require the students to recall factual knowledge and lead to authoritative discourse that does not promote students’ meaningful learning (Chin 2007 ). This research focuses on the discourse in two classrooms during whole-class discussions in lessons designed to teach students how to ask their research questions. Examining the communicative approaches and teachers’ moves allowed analyzing the possible connections between the teachers’ instructional strategies and students’ learning to ask questions.

In light of the important role of asking research questions on students’ learning in authentic scientific inquiry environments, we characterized the teaching and learning of this ability in the context of a high-school inquiry-oriented biotechnology program. We focused on both the teaching of asking research questions, as reflected in the two teachers’ teaching strategies described in the case studies, and on students’ learning, as reflected in the analysis of the research questions they generated during the lesson. Students’ ability to ask research questions, which differ from other questions by being manipulative, feasible, and meaningful for the students, was evaluated before and during a lesson that was designed to support students in formulating research questions to be investigated. Specifically, we asked:

Did—and how did—the Bio-Tech students’ ability to ask research questions change during the lessons?

What teaching strategies, mostly concerning teachers’ actions, dialogic moves, and time management, were used by the Bio-Tech teachers during the lessons?

This is a mixed-methods case study comparison research that involves mixed methods—both quantitative and qualitative. It involves non-random case studies of two teachers and their classes. The collected data include a pre-lesson questionnaire, students’ written sheets during the lessons, audio-recordings of class observations, and interviews with the class teachers.

Research context: the Bio-Tech program

The inquiry-oriented program that served as the context for this study was an inquiry program of 11th-grade biotechnology majors, entitled Bio-Tech. The Bio-Tech program is an optional part (1 credit out of a total of 5 credits) of the Israeli matriculation examinations. Bio-Tech is a year-long program, carried out in both the school and a research institute. At the beginning of the school year, the Bio-Tech classroom lessons are devoted to the study of Adapted Primary Literature (APL) scientific articles (Yarden et al. 2001 ) which present the students with the background content knowledge as well as the methods, tools, and procedures carried out in their designated research group. About 2 months into the Bio-Tech program, the class goes to the research institute for a preliminary experiment. At this stage, the students meet a scientist from one of the participating research laboratories and visit that laboratory. They learn about the research institute’s structure, departments, and main fields of research. They take part in small-scale preliminary experiments, where they are familiarized with the program’s tools and methods.

Following the preliminary visit to the research institute, the students are divided into groups of two or three students and start to plan their inquiry experiment under their teacher’s guidance, with occasional assistance from a scientist and science educator. At this stage, the students are expected to formulate their own research questions to be investigated in the main experiment. The experiment is restricted to the tools and methods available in the research institute laboratories and needs to be relevant to the research content. Once all of the students have planned their experiments and have had them approved by the teacher and scientist, the class returns to the research institute laboratories for 2 days to perform their experiments. The students then collect the data and begin to analyze and interpret the results. Once back at school, students continue to analyze the data, write up the research assay, and prepare for a final oral exam, assisted by their teacher.

Lessons in asking research questions

As already noted, students are expected to ask research questions that will lead them to the planning and execution of inquiry in the Bio-Tech program. This task usually takes place after learning the APL article and the preliminary visit to the research institute, where students are introduced to the researchers and to the laboratory techniques that will be used in their research. Back in the classroom, the teacher is expected to teach the students how to ask research questions that are appropriate to the Bio-Tech program and the class’s specific research topic. Students are expected to generate their own research questions, with the teacher’s support, which will lead them to the hands-on experiments conducted at the research institute. Here, we focus on lessons in which students were taught how to ask research questions, including an activity in which they formulated research questions and critiqued the questions formulated by their class peers. The teachers who took part in this research were asked to include the peer-critique activity in their question-asking lesson. This activity was designed as a pedagogical tool to encourage the asking of research questions and to promote the students’ communication and collaboration abilities by writing research questions in groups and having them reviewed by their peers, as recommended by Henderson et al. ( 2015 ).

The peer-critique activity was based on a written sheet received by each group. First, the students were asked to write down three research questions that they would like to investigate in the Bio-Tech program. Then, they chose one of the questions and asked it as a research question, according to what they had learned in the previous part of the lesson. The groups then exchanged their written question with another group. The students were asked to critique the other group’s question, based on the research-question characteristics they had learned. These characteristics include the following: (i) the question should be related to the research topic, (ii) the question should consist of dependent and independent variables and the relationships between them, and (iii) the question should be appropriate for research under the limitations of complexity, available equipment, and time. The critiquing students were also asked to rewrite the research question so that it would be appropriate for the Bio-Tech program. Subsequently, the original groups got their reviewed question back, wrote their response to the other students’ critique, and formulated their final research question. Taken together, this interactive activity offered the students an opportunity to independently formulate their own research questions and to evaluate their own and their peers’ questions. Collected data included students’ written questions in the pre-lesson questionnaire, questions during the peer-critique activity, and final research questions which were investigated by the students later in the program.

Participants

Two biotechnology teachers and their students were chosen for this study by convenience sampling. The teachers, Sam and Rebecca (not their real names), were experienced biotechnology and biology teachers. Their students participated in the Bio-Tech program during the 2012/2013 academic year. The two teachers were chosen for this research because they were both experienced biotechnology teachers with many years of experience in teaching different inquiry programs (Table 1 ). Most of the students were of middle to high-middle average socio-economic background, based on the teachers’ report and the 2006 Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics report, in which the local municipalities were ranked 139 and 147 for the average socio-economic ratio out of 197 (197 being the highest socio-economic ranked municipality, http://www.cbs.gov.il/www/publications/pw77.pdf ).

Observations, recordings, and artifacts of the lessons

The teaching and learning of how to ask research questions in the Bio-Tech classes that participated in this study were facilitated by a lesson that included explanations and examples of appropriate research questions and the peer-critique activity. The teachers, who volunteered to use the peer-critique activity, were trained to use the activity and asked to incorporate it in their planned lessons. Prior to the lesson on how to ask research questions, students were given a questionnaire in which they were asked to write at least three research questions that they would like to explore. The pre-lesson questionnaire was filled out by individual students, while the peer-critique activity was performed by the designated research groups. The results presented in this study were taken from lessons of the two Bio-Tech teachers, Sam and Rebecca, who performed the activity in the 2012/2013 academic school year. Collected data included students’ written sheets and audio-recordings of the lessons. Students’ written questions during the peer-critique activity were collected, analyzed, and compared to the students’ questions in the pre-lesson questionnaire and to their final research questions, investigated in the Bio-Tech program.

Interviews with the teachers

Semi-structured interviews with the two Bio-Tech teachers were performed right after the lesson on how to ask research questions, at the end of the school year, and 1 year later. In the interviews, the teachers described their teaching strategies and goals for the asking of research questions in the Bio-Tech program and addressed specific cases from the analyzed lessons that were presented to them.

Parts of the interviews that address the teaching and learning of asking research questions were transcribed and analyzed. Teachers were prompted to describe their approach when teaching students how to ask research questions, the process that the Bio-Tech students experienced during the program when formulating and investigating their research questions, and other opportunities the students may had to engage in asking research-question practice in school. Teachers’ answers which addressed these issues were transcribed and used to determine teachers’ attitudes towards their teaching approach and students’ learning of asking research questions in the Bio-Tech program. Another science-education researcher validated emerging attitudes, and consensus was reached for determining teachers’ attitude.

Analysis of students’ written questions

Students’ written questions in the pre-lesson questionnaire and in the peer-critique activity sheet were classified as research or non-research questions, based on the definition of Cuccio-Schirripa and Steiner ( 2000 ). To be classified as a research question, the following criteria are required: (i) answering the question requires a hands-on investigation and data collection; (ii) the question includes a specific measurable dependent variable, a specific manipulated independent variable, and the connection between them; and (iii) the answer to the question is unknown to the student. Questions that did not meet all of these criteria were classified as non-research questions. For example, one of the students’ suggested research question was as follows: “The effect of LDL on dismantling of neural toxic gas.” This question was classified as a non-research question, since it is not specific and does not include measurable variables. Another example was the following question: “What is the difference between the effect of Tetracycline and Kanamycin antibiotics in the growth medium on the growth of the bacteria that contain the PON1 gene?” This question was classified as a research question, since it required hands-on investigation, includes measurable variables, and the answer is not known to the students.

Students’ questions were statistically analyzed using Pearson’s χ 2 test of independence. Effect size was calculated for standardized differences between two means of percentage of research questions in each class using Cohen’s d . Students’ questions prior to the lesson were matched and compared to the research questions they wrote during the peer-critique activity and to the final research questions that they investigated during the Bio-Tech program. Classification of the students’ questions was validated by four science-education researchers who rated a sample of about 10 % of the questions. Raters were asked to classify the questions as research or non-research. More than 80 % agreement was achieved between the raters. Debatable questions were further discussed among the authors until full agreement was reached.

Analysis of the classroom discourse

The communicative approach analytical framework (Mortimer and Scott 2003 ) was chosen to examine the classroom discourse during the lesson on how to ask research questions. Audio-recordings of this lesson were fully transcribed and divided into episodes and utterances. The episodes were divided according to the content discussed in each part of the lesson. Each utterance included one speech turn. Some speech turns were divided into several utterances according to their content. Each utterance was coded and classified according to the communicative approach framework (Mortimer and Scott 2003 ). Utterances were analyzed according to the I-R-E patterns of interaction (Lemke 1990 ; Mehan 1979 ).

Frequencies of dialogic sequences were calculated for each examined lesson part. Dialogic interactions that were interrupted or not completed were classified as “truncated chains.” Dialogic sequences that included only the triadic pattern were classified as “closed I-R-E chains.” Dialogic sequences that included the teacher’s prompting and delayed evaluation were classified as “long open chains.” The teachers’ instructional moves were coded into the following categories, based on Pimentel and McNeill ( 2013 ): open questions (questions with many possible answers, aimed to expose students’ ideas and thoughts), closed questions (questions with one possible answer that is known to the teacher), probing (asking the student to clarify or elaborate on his/her response, avoiding evaluation), elaborating (long teacher explanation following a short response from a student), toss-back (asking the students to comment on another student’s response, avoiding evaluation), and re-voicing (repeating a student’s response with slight changes, avoiding evaluation). Long speech acts were defined as teachers’ utterances of more than 100 consecutive words. The percentage of teacher talk during the examined lessons was calculated by dividing the number of teacher words by the total number of words spoken during the examined lesson part. For validation purposes, about 10 % of the transcribed lessons were analyzed by five science-education researchers, and more than 80 % agreement was achieved between the raters. The debatable sequences were further discussed until a full consensus was reached.

Development of students’ ability to ask research questions during the lessons

To examine the possible development of students’ ability to ask research questions, an in-depth examination of students’ questions, written during classroom lessons, was performed. The Bio-Tech lessons of two teachers, Sam and Rebecca, were chosen for examination. These lessons included a peer-critique activity that was designed to engage students in collaborative discussions and critiquing. These lessons were assumed to be central to the students’ learning to ask research questions in the Bio-Tech program. It is not suggested that this is the only factor that contributes to the development of the Bio-Tech students’ ability to ask research questions; however, it might be a meaningful part of the program that contributed to the students’ learning of this ability. Students’ research questions, written during the peer-critique activity in the examined lessons, were compared to two sets of questions: (i) students’ suggested research questions in the pre-lesson questionnaire and (ii) students’ research questions that were investigated in the main experiments of the Bio-Tech program.

Students’ questions were categorized as research or non-research questions, based on the aforementioned definition of Cuccio-Schirripa and Steiner ( 2000 ). The percentage of research questions written by Rebecca’s students significantly increased during the peer-critique activity (38.5 % in the pre-lesson questionnaire and 89.3 % in the peer-critique activity, χ 2 = 15.45, df = 1, p < .001). The percentage of research questions written by Sam’s students remained low in the pre-lesson questionnaire and during the peer-critique activity (3.7 and 5.4 %, respectively, χ 2 < .001, df = 1, p = 1). The effect size in Rebecca’s class was high (Cohen’s d = 1.03) compared to the low effect size in Sam’s class (Cohen’s d = .08), indicating that Rebecca’s lesson improved her students’ ability to ask research questions, in contrast to Sam’s lesson (Fig. 1 ).

A comparison of students’ ability to ask research questions before and during the two lessons. * p < .001, n = number of questions

In Sam’s class, 12 groups of students formulated their research questions during the peer-critique activity. However, none of the final research questions that were investigated by Sam’s students in the Bio-Tech program were based on the questions that his students formulated during the lesson. In his interview, Sam mentioned that most of the research questions were given to the students prior to the main experiment at the research institute. He claimed that he tried to match the research questions to those suggested by the students during the lesson but that most of their questions were not appropriate or impossible to investigate at the research institute.