GCIII Commentary: ten essential protections for prisoners of war

Over the past seventy years, the Third Geneva Convention (GCIII) has ensured that prisoners of war are treated humanely and with respect for their dignity while in the hands of enemy forces, saving countless lives. The Convention was drafted in the wake of the Second World War, during which time millions of prisoners of war were victims of horrific atrocities. In 1949, with these painful lessons in mind , the Third Geneva Convention revised and expanded the existing protection afforded to prisoners of war under the 1929 Convention .

The 1949 Convention contains 143 articles, 46 more than its predecessor. These additions and revisions were deemed necessary, given the changes that had occurred during the previous two decades in the conduct of warfare and its consequences. Experience had shown that the daily life of prisoners revolved around the specific interpretations of the Convention’s general regulations.

As a result, certain regulations of the 1949 Convention were designed more explicitly, providing clarity that was lacking in the preceding provisions. The categories of persons entitled to prisoner of war status were broadened to encompass members of militias or volunteer corps belonging to parties to conflicts under certain conditions. The conditions and places of captivity were also more precisely defined, in particular with regard to the labour of prisoners of war, their financial resources, and the relief they receive. The guarantees to be afforded in the judicial proceedings instituted against prisoners were specified; and a unilateral obligation was established to release and repatriate them without delay after the cessation of active hostilities.

As part of its mandate, the ICRC visits prisoners of war to ensure respect for the Convention’s protective standards. In our work, we have been in a position to witness the impact that the Third Geneva Convention can have for prisoners of war when it is respected. The detaining authorities’ compliance with the protections afforded by the Convention is directly reflected in prisoners’ physical and mental health, their resilience in the face of adversity, and their capacity to recover from captivity.

Last month, the ICRC launched its updated Commentary on the Third Geneva Convention of 1949. The updated Commentary analyzes how the practice in the application and interpretation of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 has evolved in the past decades. It also provides a fresh interpretation of the Convention, taking into consideration the legal and technological developments that have occurred since the publication of the first Commentary on the Third Geneva Convention sixty years ago.

The following provides an overview of ten of the most essential protections afforded by the Third Geneva Convention to prisoners of war in armed conflict.

1. Humane treatment

At the heart of the Third Geneva Convention is the fundamental principle that prisoners of war must be treated humanely and protected at all times. They are protected against acts of violence and intimidation, insults and public curiosity, and against reprisals. Prisoners of war may never be subjected to medical or scientific experiments that are not medically justified and in their own interest – a key protection and a hard-won lesson from the experience of the Second World War. The overarching principle of humane treatment is reflected in many provisions of the Convention and must guide their interpretation.

2. Respect for their persons and honour

Humane treatment of prisoners of war also means that the Detaining Power must respect their persons and their honour in all circumstances. While some old-fashioned undertones tinge a reading of these provisions, the enduring idea is one of ‘due regard for the sense of value that every person has of themselves’. Prisoners of war must not only be allowed to wear their badges of rank and nationality and their military decorations and be treated in accordance with their rank and age, in respect of their military honour; they must also, importantly, be granted suitable working conditions, which can never be humiliating, and they must be paid for their work.

3. Principles of equality and non-adverse distinction

All prisoners of war are entitled to the same respect and protection and must be treated equally . This entails not only a prohibition against discrimination of certain prisoners of war, but also an obligation to take into consideration and respond to specific needs, especially when dealing with certain categories of prisoners such as women, persons with disabilities, or children. While the vocabulary used in the 1949 Conventions is somewhat outdated, for instance language relating to ‘mental disorder’, it represented progress in its time. For example, while the 1929 Convention merely required that women be treated ‘with all consideration due to their sex’, the 1949 Convention added that they must be afforded in all cases ‘treatment as favourable as that granted to men’. Today, the wording of the Convention, interpreted in light of its object and purpose, allows for an interpretation that takes into account specific needs of diverse prisoners of war.

4. Questioning

When questioned , prisoners of war are bound to give only their name, rank, date of birth and military service number. Upon receiving such information, the Detaining Power will be able to establish their identity, status and rank as members of the enemy armed forces. This is an essential safeguard, as it enables the Detaining Power to properly identify prisoners of war and prevent them from going missing, as well as to accord them the treatment to which they are entitled. It is absolutely prohibited to subject prisoners of war to any physical or mental torture, nor to any other form of coercion, to obtain information of any kind whatsoever.

5. Medical attention

The Third Geneva Convention specifies a series of measures to ensure that prisoners of war receive adequate medical attention , as required by their state of health. Throughout the Convention, both physical and mental health is emphasized. Such measures comprise, for example, monthly medical inspections and access to healthcare – including special treatment in case of serious diseases – and access to special healthcare facilities for persons with disabilities. The Convention also prescribes the creation of isolation wards in case of contagious diseases and imposes hygiene and sanitary measures to ensure clean and healthy living conditions in camps. Seriously wounded or sick prisoners of war must be directly repatriated to their own country or transferred to a neutral country for treatment, depending on the expected likelihood and time of their recovery.

6. Contact with the outside world

The Third Geneva Convention affords prisoners of war the right to keep in contact with their family. It allows them to send and receive letters and cards , receive parcels and collective relief shipments and strictly regulates the possibility to censor correspondence and examine consignments. More modern means of communication should also be considered, as such provisions must be interpreted in light of the latest technological developments in telecommunication. The Third Geneva Convention reinforces the obligation – already present in 1929 – to establish a Central Tracing Agency for prisoners of war, mandated to collect and centralize information on prisoners of war and transmit it to the Parties to a conflict. Since 1949, the Agency has been under the ICRC’s responsibility.

7. Right to be visited by the ICRC

The Detaining Power must allow ICRC delegates to visit all places where prisoners of war are located and interview them without witnesses. The authorities cannot impose any restriction on which places and prisoners of war may be visited. With its supervisory role, the ICRC makes sure that prisoners of war are treated in compliance with the rights and obligations afforded by the Third Geneva Convention, that their needs are met, and that they do not go missing. To this end, the ICRC may provide additional support to the authorities through the Central Tracing Agency or based on its right to offer its services as a humanitarian and impartial organization.

8. Right to a fair trial

The objective of the internment of prisoners of war is not to punish them, but to prevent captured soldiers from further taking part in the ongoing hostilities against the Detaining Power. Therefore, prisoners of war may not be prosecuted for the mere fact of having participated in hostilities. If accused of an offence, prisoners of war must be tried before an independent and impartial court, in a fair trial affording all essential judicial guarantees. For their sentence to be valid, it must be issued by the same courts and according to the same procedures as in the case of the members of the Detaining Power’s armed forces.

9. Educational and recreational activities

The detaining authorities must encourage prisoners of war to pursue intellectual, educational, and recreational activities . To this end, the authorities must provide adequate premises and equipment to practice activities such as studying, playing musical instruments, sports and games, with a special attention to physical exercise and open-air activities. This protection is directly related to the principle of humane treatment, as it helps the prisoners of war cope with their captivity by maintaining their physical and mental well-being. The Detaining Power must always respect the prisoners’ individual preferences and must not subject them to propaganda activities.

10. Release and repatriation

Prisoners of war must be released and repatriated to their own country without delay after the cessation of active hostilities, except where they have been criminally indicted or are serving a criminal judicial sentence. Due to the lack of formal peace agreements, the release of millions of prisoners of war was delayed for many years after the end of the Second World War. For this reason, the 1949 Third Geneva Convention specifies that the obligation to release and repatriate prisoners of war does not depend on reciprocity and is applicable even in the absence of a peace treaty.

Seventy years on, the Third Geneva Convention remains the most important international treaty protecting prisoners of war. It was a milestone of progressive thinking on the meaning of humane treatment in its time. It remains so today and, when read together with the more contemporary interpretations provided by the updated Commentary , is a practical and invaluable source for safeguarding the humane treatment of prisoners of war in armed conflicts.

- Jean-Marie Henckaerts, GCIII Commentary: ICRC unveils first update in sixty years , June 18, 2020

- Cédric Cotter, The 1918 Bern Agreements: repatriating prisoners in a total war , March 29, 2018

- Jean-Marie Henckaerts, Joint series: Locating the Geneva Conventions Commentaries in the international legal landscape , June 29, 2017

Civilian internment in international armed conflict: when does it begin?

12 mins read Analysis / Detention / GCIII Commentary / Law and Conflict Jelena Pejic

The internment of protected persons and the Fourth Geneva Convention

15 mins read Analysis / Detention / GCIII Commentary / Law and Conflict Mikhail Orkin

Strange that in the 10 points, there is no explicit mention of right to food and adequate nutrition.

GCIII Framework reads perfectly well – it covers most of fundamental needs needed by prisoners of war just like any other persons.

I would like to understand on Item 4 “Questioning”. I am imagining the situation when some people are forced to engage themselves in war crimes against their own will. Does the questioning process get to granular level to ascertain whether captured war prisoners were the case of forced involvement in war crimes? If so, what happens afterwards in this case?

With reference to Item 9 “Educational and Recreational activities”. My suggestion on this point is in subsequent GC versions, “correctional services” should be considered as an important aspect to the prisoners of war. Training should go beyond intellectual and education, things like psychological, emotional intelligence and many other should be offered to prisoners of war – the aim is to make sure after their release and getting back to their respective countries they become better citizens and forgetting about war conflict experiences.

Lastly, on Item 10 “Release and Repatriation”. What I miss from the analysis is whether the GCIII provides provisions to follow up on repatriated prisoners of war in their respective countries. Reintegrating back to the society might be a big challenge especially when members of societies perceive repatriated prisoners bad persons. This might lead to retaliation and/or any form of backlash to such returning prisoners of war. My question is does the ICRC have follow up programme to ensure returning prisoners of war do not face backlash from their own people?

Great article and very informative.

thank you very much dear Cordula this is very impressive: very important topics so clearly formulated and indeed beautifully read! I was involved with PoW during my missions as Medical delegate to Iran/Iraq in 1980 at the beginning of that war in September 1980 and in 1982 when we had to bring back the first Sovjet PoW since WWII to a “neutral Country” (=Switzerland) from the Afghan border which then allowed the ICRC to open again the Delegation in Kabul… and last year for the opening of that impressive Exhibition 7millions! in Verdun Congratulations & thanks! Jürg

Leave a comment

Click here to cancel reply.

Email address * This is for content moderation. Your email address will not be made public.

Your comment

Prisoners of war and detainees protected under international humanitarian law

29-10-2010 overview.

The third Geneva Convention provides a wide range of protection for prisoners of war. It defines their rights and sets down detailed rules for their treatment and eventual release. International humanitarian law (IHL) also protects other persons deprived of liberty as a result of armed conflict.

The rules protecting prisoners of war (POWs) are specific and were first detailed in the 1929 Geneva Convention. They were refined in the third 1949 Geneva Convention, following the lessons of World War II, as well as in Additional Protocol I of 1977.

The status of POW only applies in international armed conflict. POWs are usually members of the armed forces of one of the parties to a conflict who fall into the hands of the adverse party. The third 1949 Geneva Convention also classifies other categories of persons who have the right to POW status or may be treated as POWs.

POWs cannot be prosecuted for taking a direct part in hostilities. Their detention is not a form of punishment, but only aims to prevent further participation in the conflict. They must be released and repatriated without delay after the end of hostilities. The detaining power may prosecute them for possible war crimes, but not for acts of violence that are lawful under IHL.

POWs must be treated humanely in all circumstances. They are protected against any act of violence, as well as against intimidation, insults, and public curiosity. IHL also defines minimum conditions of detention covering such issues as accommodation, food, clothing, hygiene and medical care.

The fourth 1949 Geneva Convention and Additional Protocol I also provide extensive protection for civilian internees during international armed conflicts. If justified by imperative reasons of security, a party to the conflict may subject civilians to assigned residence or to internment. Therefore, internment is a security measure, and cannot be used as a form of punishment. This means that each interned person must be released as soon as the reasons which necessitated his/her internment no longer exist.

Rules governing the treatment and conditions of detention of civilian internees under IHL are very similar to those applicable to prisoners of war.

In non-international armed conflicts, Article 3 common to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol II provide that persons deprived of liberty for reasons related to the conflict must also be treated humanely in all circumstances. In particular, they are protected against murder, torture, as well as cruel, humiliating or degrading treatment. Those detained for participation in hostilities are not immune from criminal prosecution under the applicable domestic law for having done so.

© CICR/VII / R. Haviv / ht-e-00347

Related sections

- Prisoners of war and detainees

- Visiting detainees

- Directories

- Agriculture

- All Things Congressional

- American State Papers

- Arms Control Sales and Data

- Army Corps of Engineers, Annual Reports

- Bills - U.S. Congress

- Bills - Washington State Legislature

- Business and Economics

- Census and Population

- Census 2000

- Census 2010

- Census 2020

- CIS Index to the U.S. Executive Branch Documents

- Citation Guides for Government Publications

- Cities, Counties and States

- Climate Change

- [All Things] Congressional

- Congressional Floor and Committee Schedules

- Congressional Hearings

- Congressional Issues

- Congressional News

- Congressional Papers

- Congressional Prints

- Congressional Record

- Congressional Reports

- Congressional Voting Records

- Country Information

- [U.S.] Congressional Serial Set

- Defense and War

- Directories and Biographies

- Employment and Labor

- Employment Rights

- Enumeration Districts

- Environment

- Environmental Impact Statements (EIS)

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- European Union

- Exchange Rates

- Executive Branch Documents

- The Executive Office of the President

- Executive Orders and Proclamations, U.S. President

- Executive Request Legislation, Washington State

- [U.S. Lower] Federal Courts

- Federal Register

- Federally Published Peer Reviewed Journals

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

- Foreign Aid

- Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS)

- Foreign Direct Investment

- Foreign Relations of the U.S.

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Gays in the Military

- Geneva Conventions: Treatment of Prisoners of War

- Government Manuals

- Grants and Contracts

- Hanford Site

- Health Care Reform

- Helsinki Accords

- Homelessness

- How to Trace Washington State Law

- Human Rights in Government Publications

- Immigration

- Impeachment of a U.S. President

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

- International Aid Data

- International Financial Statistics

- International Monetary Fund (IMF)

- Journals of the House and Senate

- King County Voter Guides

- Laws, Regulations, Constitutions

- Legislative Branch Overview

- Legislative Histories

- Legislative Process

- Library of Congress

- Local Northwest

- Maps in Government Publications

- Migration & Refugees

- National Security Archive

- Native Americans

- Northwest and Alaska Fisheries

- Occupational Safety

- Official Register

- Oil Spill 2010

- Open Government

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- Oso (SR 530) Landslide

- Pacific Northwest

- Patents and Trademarks

- [Federally Published] Peer Reviewed Journals

- The [U.S.] Presidency

- [The Executive Office of the] President

- Senate Executive Documents and Reports

- [U.S. Congressional] Serial Set

- Social Security

- Statistical Abstract of the United States

- [U.S.] Statistics

- Statistics in Government Publications

- Supreme Court

- Sustainable Living in the Pacific Northwest

- Technical Reports

- Transportation

- United Kingdom Parliament

- United Nations (UN)

- U.S. Congressional Serial Set

- [U.S. Executive Branch] Departments and Agencies

- U.S. Federal Regulations

- U.S. Supreme Court

- Videos and Tutorials

- Vital Records

- Vital Statistics

- Washington State

- Washington State Historical Census Records

- Women in the Labor Force

- World Bank Group

- Who We Are: Diversity in Government Documents

- Back to Government Publications guide

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Government Sources by Subject

Government Sources by Subject: Geneva Conventions: Treatment of Prisoners of War

Starting points.

The Geneva Conventions, also known as the Geneva Red Cross Conventions, are international agreements to protect non-hostile individuals such as the sick, wounded, prisoners of war, and civilians during times of war.

- GENEVA CONVENTION, The Avalon Project, Yale University Laws of War: a list of agreements with their coinciding years and links to the full text. The Geneva Conventions are at the bottom of the page.

- Encyclopedia of Prisoners of War and Internment Nearly 300 entries on the history of prisoners of war and interned civilians. Includes entries for the Geneva Conventions. See the index for other entries that refer to the conventions.

Geneva Convention 1929

- Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War Full text provided by the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Geneva Convention 1949

- Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, United Nations The text of the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, from the United Nations.

- United Nations Treaty Series (UNTS), 1949, volume 75 Print only. * I. Amelioration of the wounded & sick (land) * II. Amelioration of the wounded & sick (sea) * III. Treatment of POWs * IV. Protection of civilians

- Multilateral treaties : index and current status Print only. See citation and notes under Treaties 238 to 241.

1864 Geneva Convention

Delegate signatures on the 1864 Geneva Convention.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons .

- << Previous: Gays in the Military

- Next: Government Manuals >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 1:48 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/govpubs-quick-links

- Advanced Search

Version 1.0

Last updated 08 october 2014, prisoners of war (germany).

Long overlooked, the prisoner of war experience of the estimated 2.4 million combatants held in German captivity during the Great War has recently been the subject of significant new research. Historians now emphasise the scale of captivity, the modern technologies used, the differences between the German home front camps and the front line camp system and the extent of prisoner of war forced labour in the German war economy. They interpret the prisoner of war experience in terms of what it shows about wartime processes of totalisation and brutalisation.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Historiography

- 3 The German home front and Etappen camp systems

- 4 Totalisation

- 5 Brutalisation

- 6 Humanitarianism

- 7 Conclusion

Selected Bibliography

Introduction ↑.

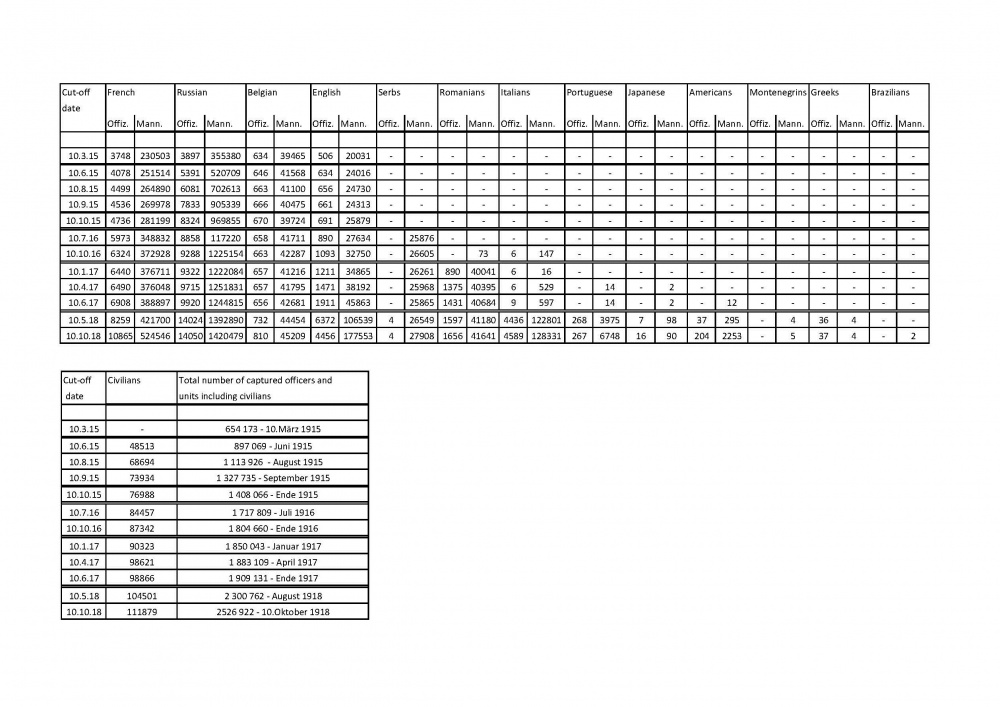

At least seven, and perhaps as many as eight to nine million soldiers in total were taken prisoner in 1914-1918. [1] In German prisoner of war camps alone, the military authorities estimated that there were approximately 2.4 million soldiers from thirteen nations by the end of the war; the biggest nationality among these captives were the over 1.4 million Russians taken prisoner by Germany by October 1918, followed by over half a million French prisoners. [2] In 1914, Germany captured dramatically high numbers of prisoners, particularly at the battles of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes. By 1915, Germany already held over a million captives.

Historiography ↑

In spite of these immense numbers, captivity was for decades a forgotten aspect of the war experience. Prisoners of war from the Great War were largely ignored in the historiography of all the belligerent states. In the German case, the catastrophic experience of the Second World War and the long campaign into the 1950s to obtain the release of German Second World War prisoners from the Soviets, left little room for interest in the treatment of prisoners of war in 1914-1918. This first changed in the 1990s: in Germany, research into German crimes against prisoners of war and forced labourers in 1939-1945 raised the question of possible historical continuities linking the two world wars [4] and German reunification allowed access to new source materials. Internationally, the interpretation of the First World War broadened to include new research on both the everyday experience of the conflict and its cultural dimensions, including its impact on home front societies beyond the battlefront, a shift which facilitated new work on prisoners of war. Above all new research paradigms emerged: what role the First World War played in the development of " total war " in the 20 th century became a central question. [5]

The German home front and Etappen camp systems ↑

As a result of these new research perspectives many important aspects of the German prisoner of war camp system – as well as the development of forced labour in the First World War [6] – have now been intensively researched. [7] It is now clear that the prisoner of war camp system within Germany developed from a largely improvised scattering of ad hoc , relatively primitive camps in 1914-1915, frequently located at or near existing military barracks and urban centres, to a relatively sophisticated system of major, industrial scale camps ( Stammlagern ) by 1916. This included a complex network of smaller, more mobile, working unit affiliates ( Arbeitskommandos ), allowing prisoner labour to be deployed to where it was most needed by the wartime economy: several German economic sectors, including agriculture, heavy industry in the Ruhr, mining, quarrying and land drainage became very dependent on prisoner labour during the war. Prisoner labour was used on an enormous scale: by August 1916, 90 percent of all prisoners in Germany were employed outside their camp in working units. [8]

While in 1914-1915 prisoner nationalities were mixed, the German authorities later opted to partly segregate nationalities within large camps into different sections or barracks. From the very start of the war, officer prisoners of war were segregated in specially designated officer camps where facilities were better than in the camps for other rank captives. Among the biggest camps within Germany were Limburg, Heilsberg, Schneidemühl, Gardelegen, Merseburg, Lamsdorf, Neuhammer, Münster, Friedrichsfeld, Güstrow, Parchim, Hameln, Soltau, Cassel-Niederzwehren, Worms, Danzig-Troyl, Hammerstein, Darmstadt, Tuchel, Saarbrücken and Senne, to each of which over twenty thousand prisoners were assigned. [9]

As well as home front camps, the German army also established prisoner of war labour companies for other rank prisoners in the front hinterland areas ( Etappen ) in occupied French, Belgian and Russian territory. The first prisoner of war labour companies on the Western Front were established by the German army in 1915, containing Russian prisoner of war labourers transferred to the west. By 1916, German prisoner of war labour companies at the Western Front and its hinterland contained multiple prisoner nationalities, including British and French captives. In total, German prisoner of war labour companies on the Western Front contained over 250,000 prisoner workers by 1916. These prisoners were often mistreated and generally endured worse working and living conditions than their counterparts in Germany. In 1918, conditions in German army prisoner of war labour units on the Western Front deteriorated badly, due to food shortages and the strain of incorporating over 70,000 British captives taken in the first weeks of the Ludendorff Offensive, the majority of whom were sent directly into front line labour companies, where they endured frequent beatings and did not usually have access to food parcels or post from home. Prisoner of war labour companies on the Western Front were used by the German army for heavy manual labour, maintaining roads and railways, lines of communication and loading and unloading supplies. Total death rates for prisoners of war in these Western Front labour companies remain uncertain but witness evidence suggests they were high in 1917-1918. [10] Little is known still of conditions in prisoner of war labour companies working for the German army on the Eastern Front .

The management of prisoner of war labour varied between the front and the home front captivity systems. In the prisoner of war labour company system, operating at the front line and Etappen areas in the hinterland to the front, a variety of different military levels and army administrative departments controlled the treatment of prisoners. Although aware of Prussian Ministry of War general directives on prisoner of war treatment emanating from Berlin they had considerable leeway to ignore them and the prisoners in their charge were effectively under the complete control of the German army in the field. Within Germany proper, however, captivity administration was organized differently, by over twenty regional district army commanders and their subordinate administrative departments, with considerable local powers, working together with a number of Prussian Ministry of War sub-departments in Berlin, as well as the regional Ministries of War, where one existed, such as in Bavaria or Saxony. Although the Unterkunftsdepartment at the Prussian Ministry of War led by General Emil Friedrich was theoretically meant to oversee the system, this administrative complexity led to confusion, as well as overlap, in terms of who had competence to manage particular aspects of prisoner treatment. Uta Hinz has referred to how this complex administrative system suffered from "bureaucratic fragmentation," something which increased as the numbers of prisoners employed in the German war economy rapidly rose. The military authorities within Germany responsible for prisoner treatment stated that prisoners of war were subject to German military law and German army disciplinary regulations, which was in accordance with international law . This legal status continued until the end of the war, although the implementation of these legal controls on the ground was far from uniform, particularly during the early years of the war.

In sum, between 1914-1918, Germany developed a very sophisticated home front system of captivity which utilised technological advances such as barbed wire and improved hygiene knowledge, logistical advances in railways and bureaucratic advances in maintaining records, to distribute and manage a forced labour cohort of over 2 million men, the vast majority of whom survived the war, although death rates were significantly high for Romanian and Italian prisoners in German captivity. There was relatively little disease in German prisoner of war camps, with the exception of a major typhus outbreak in 1915 and the Spanish influenza outbreak in 1918. Indeed, the major organizational challenge which the German authorities faced with regard to prisoners was not disease but food supply. According to international law, set out in The Hague Conventions , prisoners of war were to be fed the same rations as the troops of the captor army. However, as early as 1915, the German military administration, aware that in a long war with an on-going Allied maritime blockade Germany would face a shortage of food supplies, introduced measures to economise on food provided to prisoners. Initially in 1915, the quality of prisoner food was reduced and the prisoner of war bread ration was made equivalent to that provided to German civilians, not German troops; a break with international law. From 1917, in many of the main home front prisoner of war camps the minimum calorie ration set by the German administration was no longer being provided to prisoners. Those working outside the camps in prisoner of war working units in Germany often fared better, receiving better food. However, during the war, all prisoners, in camps or working units in Germany became increasingly dependent on food parcels from their home state in order to survive. German prisoners of war in enemy hands also benefited as the parcel system was allowed on a "reciprocal" basis. In addition, parcels helped to alleviate the increasing economic difficulties that Germany faced in feeding its prisoners of war as the conflict went on.

German captivity in the Great War thus combined forced labour with relatively high survival rates for most prisoner nationalities, presenting historians with a conundrum: how to interpret its combination of harsh discipline, inadequate rations and heavy forced labour on the one hand with the modernisation of prisoner living conditions and relative lenience in permitting prisoners access to leisure and educational activities within home front camps, on the other. For historians this paradox lies at the heart of Great War captivity in Germany. There is generally the consensus that between 1914 and 1918 captivity underwent fundamental changes. Yet the causes of these radicalisation processes, as well as the extent of their impact, have been emphasised in different ways by historians.

Totalisation ↑

One interpretation situates German prisoner of war policy in terms of an increasing process of ideological and economic totalisation of both war practices and imagery. Uta Hinz contends that an ever-widening definition of what constituted wartime necessity led to radicalisation processes, [11] whose impact, however, did not affect all areas of prisoner of war treatment to the same degree. [12] Totalisation describes a structural shift in how war is waged which leads to the breakdown of the boundaries between the front and home front, as well as between combatant and non-combatant, being the result of an ever more radical mobilisation, control and exploitation of resources, as the historians Stig Förster and Roger Chickering have argued. [13]

Elements of such totalisation are identifiable in Germany from 1915 on. The original purpose of captivity, to weaken the enemy militarily by reducing its combatant numbers through capture, decreased in importance. A shift from seeing prisoners in military terms to seeing them in economic terms took place. Until 1915, enemy prisoners were perceived in largely military terms, held in extremely provisional, military-run camps and the German authorities saw prisoners in terms of captive soldiers rather than labourers; illustrated by the fact that one of the main problems that the German captor army focused on up to this point was how to maintain military "discipline" among captives. From 1915 on, however, other rank soldiers from the over 100 main prisoner of war home front camps in Germany were employed in agriculture and, from 1916 on, increasingly in industrial working units where in some cases working conditions were very poor as wartime output demands led to the attenuation of peacetime safety norms in mines and factories. The central aim now was to exploit prisoners’ labour as comprehensively as possible, according to the military assessment of what was economically necessary – an assessment that was subject to ever-decreasing constraints.

From spring 1916, all prisoners were classified according to their work capability, with only those categorised as "heavy manual labourers" still receiving the full food ration; prisoners’ work skills were also identified so that those with previous experience as mechanics or miners could be used in the relevant work sectors. The classifications regarding who was fit enough to work and what kinds of work they could do became increasingly broad as the war continued and ministerial instructions regarding how to increase worker output became successively harsher. The prohibition on employing prisoners on tasks connected with their captor state’s war effort which was enshrined in Article 6 of the annex to the 1907 Hague Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land was increasingly ignored, both within Germany and in the prisoner of war labour companies in the front hinterland. Even though the food situation in Germany was precarious in 1916, and progressively worsened in the following years, no major exchange of prisoners of war who were capable of working took place, nor did the separate Brest-Litovsk peace agreement with Russia in 1918 lead to the repatriation of Russian prisoners of war from Germany as these were too important a labour resource to lose.

The status of captured soldiers was increasingly defined by their utilization in the war economy. This structural totalisation proceeded in stages and even by 1917-1918 it did not affect all parts of the fragmented German prisoner of war system to the same extent. Two-thirds of all prisoners of war employed in Germany worked in agricultural working units where military control was weakest and the food supply situation remained tolerable. This latter fact was crucial for prisoners of war who received little or no material support from their home states, particularly the over 1.4 million Russian soldiers in German captivity, a large proportion of whom worked in agriculture. According to the military authorities, guards’ and employers’ treatment of prisoners working in agriculture was far too "lax." Indeed, economic totalisation – which necessitated prisoner labour – in some ways impeded brutal treatment as prisoner workers could do more work when adequately fed and cared for. Both civilian employers and the military were forced to recognize that incentives improved prisoner work performance more than repression or punishment.

Brutalisation ↑

A second approach by historians sees prisoner of war treatment in the context of a comprehensive wartime cultural brutalisation with regard to the treatment of non-combatants. [14] It focuses in particular upon the question of violence against prisoners, examined within an international perspective. [15] Heather Jones emphasises the processes of reciprocal brutalisation, evident in reprisals against prisoners. Jones also considers the extensive development of a prisoner of war labour company system by Germany in 1915-1918 as part of a "drive to extremes" and argues that radicalisation processes were not only economic but were also driven by military cultural attitudes and practices, which in the German case remained beyond the limits of civilian political control.

Indeed, totalisation was facilitated by certain brutalisation shifts towards harsher attitudes to captives: prisoner of war treatment was directly affected by the incendiary escalation of the propaganda war which began at the very outset of the conflict. Reports of breaches of the laws of war by the enemy radicalised the image of the enemy and led to a brutalisation of reprisal practices against captives. In particular, Jones points to two incidents of reprisals: first, in 1916, when the German army forced British and French prisoners to work behind the Eastern Front trenches in freezing conditions in retaliation for the French use of German prisoner labour in North Africa and the British use of German prisoner labour in French ports; second, in 1917, when the German army forced British and French captives to work directly behind the lines on the Western Front, without access to proper food or shelter, in retaliation for French and British use of German prisoner labour in close proximity to the combat zone, (including, by the French, upon the Verdun battlefield). For Jones, these offer two examples of the extreme ruthlessness that developed within the German command regarding the kinds of extreme official prisoner of war reprisals that could be used. Overall, during the war, brutalisation particularly affected prisoner of war treatment in those areas which were under the exclusive influence of the German army leadership and commanders. Prisoners employed in prisoner of war labour companies at the front or in the front line hinterland suffered from severe overwork which was not subject to any form of checks and they were sometimes made to work in areas that lay within the firing zone and beaten to force them to work.

However, while brutalisation was clearly occurring, particularly with regard to attitudes to prisoner labourers working for the army in the hinterland of the front and with regard to reprisals, it was far from universal within the German home front camp system where the majority of men captured by Germany were held. The extent to which prisoners in these home front camps became the object of enmity and violence varied according to the stage of the war and differed from camp to camp and between prisoner nationalities. Individual prison camp commandants wielded a large amount of power in the German wartime state and as a result the level of mistreatment depended very much on the character of the commandant in charge of a given camp. Up to 1918, the media and wartime propaganda sometimes portrayed prisoners as the "enemy within the country", and they did depict them as epitomising different degrees of "civilisation," with Russian prisoners, in particular, often mocked as illiterate and unclean and colonial non-white prisoners of war depicted as "savage." During the years 1914 and 1915 there is also evidence that British and Russian prisoners in particular were mistreated using harsh physical punishments in some home front camps -contrary to disciplinary regulations.

Despite ministerial decrees against physical violence and increasing formal regulation, disciplinary practices remained a grey area in terms of the day-to-day reality on the ground. In contrast, prisoners from a number of distinct cultural, national, or ethnic identities were given privileged treatment to entice them to change sides and support Germany: among these groups were Irish prisoners, who were concentrated in Limburg camp in 1915 and subjected to a largely unsuccessful propaganda campaign to force them to change sides to fight against Britain; Muslim prisoners captured fighting with the British, French and Russian armies who were subject to propaganda visits by Turkish dignitaries and some of whom were ultimately sent to fight in the Ottoman army; and finally ethnic Germans captured fighting with the Russian army who were encouraged to become naturalised German citizens. Ultimately none of these policies was particularly successful; most prisoners continued to support their state of origin. In contrast, Italian prisoners were subject to particularly harsh treatment as Italy was perceived as having betrayed Germany by entering the war on the side of the Allies and, from 1917 on, Romanian prisoners of war were frequently singled out to be sent directly to work on the Western Front in very poor conditions with high death rates.

Overall, within the Reich’s borders, there is evidence that the authorities did initiate a brutalisation of prisoner of war treatment in the last two years of the war through their ever harsher orders on how prisoner labour was to be employed. According to international law prisoners were only to be put to work on tasks to which they were humanely physically suited; however, from 1917 on, this stipulation was frequently disregarded. In industrial Kommandos or working units there were also frequent complaints from prisoners that they were subject to punishments and violence if they failed to manage the heavy workload demanded of them. For the German military authorities the maintenance of legal or humanitarian standards became increasingly dispensable, dependent only upon the " needs of the war effort ." The two main factors that prevented this development from radicalising further were political and practical: the political interest in maintaining prisoner of war labour output and the practical reality of the decentralised nature of the prisoner of war system in the Reich. The visible harshening of prisoner of war policies from 1916-1917 onwards was not possible to fully implement in a regionally and military-bureaucratically fragmented system.

Humanitarianism ↑

Finally, wartime humanitarian actions also prevented further radicalisation. First, international law provided a basic level of protection for captives. The German Reich had signed both the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions on Land Warfare which, for the first time, defined international standards for prisoner of war treatment, albeit in broad general terms. Second, a form of external supervision of prisoner treatment developed with the agreement of all belligerents to the introduction of camp inspections by delegations from neutral states from 1915 on, even if this was also relatively limited in practice and limited to prisoner of war camps within the German Reich, excluding those in occupied territory and also included very few inspections of prisoner workplaces or working units located away from the main camps. Third, the Great War saw a dramatic increase in NGO activity. This was particularly true of the International Committee of the Red Cross which established an international prisoner of war aid effort based in Geneva that provided information on prisoners and organised its own camp inspections. The scale of its aid operations was immense and it increasingly expanded as the war went on. Likewise the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) provided significant aid to prisoners in Germany. Aid to prisoners also came from national relief organisations in their home countries. In sum, aid was crucial to ensuring prisoners’ physical and mental welfare – and, indeed, survival.

A trend within the German home front camp system towards humanising captivity is also visible, particularly in 1915 when the desolate conditions in German camps in 1914-1915 with regard to accommodation, hygiene and medical care improved markedly. The military authorities played a decisive role in this, their motives including not only the fear that the typhus epidemic of that year might spread to the civilian population in Germany and that the Allies might make use of poor prisoner treatment in Germany in their propaganda , but also the desire to present Germany at war as a civilized nation with a well-organised war effort. Additionally, private organisations and individuals were also engaged in improving the cultural and spiritual welfare of captives, particularly religious groups; indeed, in many large camps significant amenities for captives developed through collaborative efforts between prisoners, charities and the camp authorities, such as libraries, chapels or synagogues, printing facilities where prisoners produced their own newspapers, sports facilities, football grounds, orchestras, choirs or theatres and organized post and parcel distribution systems. Although the situation remained far bleaker for prisoners held in prisoner of war labour companies working for the German army in front hinterlands and occupied territories.

In the long-term, however, the double-edged principle of "reciprocity" proved more effective in ensuring basic standards of prisoner treatment were maintained than the motive of humanity or even the framework provided by the new international laws of war. Germany only accepted many of the humanitarian initiatives to protect prisoners in Germany on the grounds that these would equally benefit German captives in Allied hands. The inspections of prisoner of war camps were established on the grounds of reciprocity and the reciprocity principle facilitated bilateral agreements on prisoner of war treatment between Germany and individual enemy belligerent states.

Conclusion ↑

To conclude, it is clear that captivity in Germany during the Great War introduced important conceptual changes to how prisoners of war were viewed and managed. Unlike previous conflicts, the Great War saw the introduction of a sophisticated system for utilising forced labour in wartime, with the state and the military operating together to facilitate this. The scale and longevity of this forced labour system marked a decisive break with past wars, as did the very modern and technologically advanced types of prisoner of war camps that Germany constructed. This was the context in which new dynamics of totalisation and brutalisation took place. The key differences between this system and the 1939-45 war, however, were the strength of the humanitarian dynamic within the captivity sphere during the war, which safeguarded prisoners’ interests, as well as the lack of an overall ideological theoretical framework for radicalisation. Brutalisation during the Great War was always limited to certain particular sectors of the prisoner of war system or to individual camp circumstances. It was frequently ad hoc , and was never defined or formulated in terms of an overall coherent centralised policy or racialised doctrine for the whole camp system. This meant that the captivity space in Germany during the Great War remained very different to that of 1939-45, even if dangerous precedents had been set.

Uta Hinz, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf and Heather Jones, London School of Economics and Political Science

Section Editor: Christoph Cornelißen

- ↑ Oltmer, Jochen: Einführung, in: Oltmer, Jochen (ed.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, Paderborn 2006, p. 11.

- ↑ Hauptstaatsarchiv (HStA) Stuttgart, M 1/6 - 1430: Preußisches Kriegsministerium: Nachweisung der Zahl der Kriegsgefangenen nach dem Stande vom 10.10.1918. For the statistic on Russian captives see: Doegen, Wilhelm: Kriegsgefangene Völker. Der Kriegsgefangenen Haltung und Schicksal in Deutschland, Berlin 1921, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Data based on Doegen, Wilhelm: Kriegsgefangene Völker, Der Kriegsgefangenen Haltung und Schicksal in Deutschland, Tafel G., Berlin 1921, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Herbert, Ulrich: Fremdarbeiter. Politik und Praxis des "Ausländer-Einsatzes" in der Kriegswirtschaft des Dritten Reiches, Berlin 1985, pp. 24-35.

- ↑ Förster, Stig: Introduction, in: Chickering, Roger/Förster, Stig (eds.): Great War, Total War. Combat and Mobilization on the Western Front, Cambridge 2000, pp. 1-19.

- ↑ See Oltmer, Jochen: Bäuerliche Ökonomie und Arbeitskräftepolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Beschäftigungsstruktur, Arbeitsverhältnisse und Rekrutierung von Ersatzarbeitskräften in der Landwirtschaft des Emslandes 1914-1918, Bentheim 1995; Rawe, Kai: ‚...Wir werden sie schon zur Arbeit bringen‘. Ausländerbeschäftigung und Zwangsarbeit im Ruhrkohlenbergbau während des Ersten Weltkrieges, Essen, 2005; Thiel, Jens: "Menschenbassin Belgien". Anwerbung, Deportation und Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen 2007; Spoerer, Mark: The mortality of Allied prisoners of war and Belgian civilian deportees in German custody during the First World War. A reappraisal of the effects of forced labour, in: Population Studies, vol. 60 (2006), No. 2, pp. 121-136.

- ↑ Oltmer, Bäuerliche Ökonomie und Arbeitskräftepolitik, 1995; Mitze, Katja: Das Kriegsgefangenenlager Ingolstadt während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Univ. Diss. Münster 1999; Hinz, Uta: Gefangen im Großen Krieg. Kriegsgefangenschaft in Deutschland 1914-1921, Essen 2006; as well as Jones, Heather: Violence against Prisoners of War in the First World War. Britain, France and Germany 1914-1920, Cambridge 2011.

- ↑ Hinz, Gefangen im Großen Krieg 2006, p. 128.

- ↑ Doegen, Kriegsgefangene Völker 1921, pp. 12-19.

- ↑ For further information see Jones, Violence Against Prisoners of War 2011, Part Two.

- ↑ This is the argument in Uta Hinz’s analysis which focuses upon the development of camps in Germany: Hinz, Gefangen im Großen Krieg 2006.

- ↑ Ibid., in particular, pp. 356-363; Abbal, Odon: Soldats oubliés: les prisonniers de guerre français, Bez-et-Esparon 2001, p. 120f.

- ↑ See: Becker, Annette: Oubliés de la Grande Guerre. Humanitaire et culture de guerre 1914-1918. Populations occupées, déportés civils, prisonniers de guerre, Paris 1998, p. 20 and p. 90.

- ↑ For the first systematic comparison see: Jones, Violence against Prisoners of War 2011; for the broader context of prisoner treatment in terms of war violence in general, see: Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of Destruction. Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War, Oxford 2007, pp. 62-68; Kramer, Alan: Prisoners in the First World War, in: Scheipers, Sibylle (ed.): Prisoners in War, Oxford 2010, pp. 75-90.

- Abbal, Odon: Soldats oubliés. Les prisonniers de guerre français , Bez-et-Esparon 2001: E & C.

- Auerbach, Karl: Die russischen Kriegsgefangenen in Deutschland (von August 1914 bis zum Beginn der Grossen Sozialistischen Oktoberrevolution), thesis , Potsdam 1973: Pädagogische Hochschule Potsdam.

- Becker, Annette: Oubliés de la Grande guerre. Humanitaire et culture de guerre, 1914-1918. Populations occupées, déportés civils, prisonniers de guerre , Paris 1998: Éd. Noêsis.

- Hinz, Uta: Gefangen im Grossen Krieg. Kriegsgefangenschaft in Deutschland 1914-1921 , Essen 2006: Klartext Verlag.

- Jones, Heather: Violence against prisoners of war in the First World War. Britain, France, and Germany, 1914-1920 , Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Oltmer, Jochen (ed.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs , Paderborn 2006: Schöningh.

- Pöppinghege, Rainer: Im Lager unbesiegt. Deutsche, englische und französische Kriegsgefangenen-Zeitungen im Ersten Weltkrieg , Essen 2006: Klartext.

- Speed, Richard Berry: Prisoners, diplomats, and the Great War. A study in the diplomacy of captivity , New York 1990: Greenwood Press.

- Spoerer, Mark: The mortality of Allied prisoners of war and Belgian civilian deportees in German custody during the First World War. A reappraisal of the effects of forced labour , in: Population Studies 60/2, 2006, pp. 121-136.

Jones, Heather, Hinz, Uta: Prisoners of War (Germany) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI : 10.15463/ie1418.10387 .

This text is licensed under: CC by-NC-ND 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Non-commercial, No Derivative Works.

Related Articles

External links.

In these challenging times, JURIST is pledged to provide accurate, well-documented, clear and comprehensive coverage of the rule of law in crisis. But we're a non-profit service powered by law students. We need financial support from our global readership to help us train our volunteers, maintain our website, and expand our reach. Please donate to support our unique educational mission and encourage our dedicated staff in their public commitment to make a more just world. Thank you!

Bernard Hibbitts

Recently, medical workers at Israeli hospitals told BBC News that Palestinian detainees from Gaza were “ shackled and blindfolded ” while they received treatment. Physicians owe a duty to their patients based on well-established ethical principles. In truth, the doctor-patient relationship is aspirational, and at the bedside, circumstance reveals a much more complex exchange. At the core of the doctor-patient relationship, two assumptions are needed. The patient must be at liberty, and the patient must want to live. Sometimes a patient wants to die, or at least rejects treatment to allow natural death. Discourse around doctor-assisted death is important, but such requests are currently under much debate internationally and not specific to Palestinian detainees. When the patient is also a prisoner, the traditional doctor-patient dynamic really starts to fall apart.

As a physician, I have worked extensively with prisoners on death row in the US. My work concerns post-conviction death penalty defense. I have been to death rows in eight states. As an ICU doctor, I may never hear the voice of my patient owing to illness. I learn about them through friends and families. We improperly call these proxy decision-makers “loved ones.” This is a poor assumption as we cannot know the nature of these relationships. I cannot know if my patient is the abuser or the abused. Sometimes, patients can advocate for themselves and make decisions about care that are clearly not in what I imagine would be in their best interest. In best interest discourse, I hew to the middle of the road and imagine the theoretically reasonable person with normal aspirations and desires.

Sometimes, a patient demands to be released during treatment. Patients have different reasons for such demands, some tragic, some nefarious. Sometimes I let them go “against medical advice,” sometimes I double down and prevent them from leaving. My argument is that as an advocate of their best interest, they would make a different decision if they were rational. To do this, I sometimes use physical and chemical restraints to hold a patient in the bed. Such practices are common in the ICU. Laws govern the use of such restraints , but the physician is granted extraordinary power in the name of patient advocacy.

I am particularly troubled in these moments of conflict because the right to make terrible choices is at the heart of liberty, and I recognize I might be accused of projecting my beliefs when I want them to choose differently. Sometimes, my patient has done terrible things or may do terrible things to others in the future. It is not the doctor’s job to police such actions when the patient is at liberty. When I confront a morally objectionable person, I am challenged. My experience has taught me that I still owe a duty to the patient in these moments, but this might be configured as the classic example of loving humanity but hating man. The kind of patient I like the most might be the one I like the least as a person. Under these circumstances, the medical work is pure.

As difficult as the theoretical doctor-patient relationship is, the complexity rises sharply when the patient is a prisoner. In the US, Estele v. Gamble enshrines a constitutional right to healthcare, and the upholding of this right is particularly vexing when the state tries to kill the prisoner as a lawful but controversial punishment. When a prisoner becomes sick before execution, they must have their health restored, but once healthy, they can then be killed. Is it reasonable to assume a prisoner would consent to treatment so they may be executed? Physicians have also found themselves maintaining the health of prisoners so they may be further interrogated. The blurry line of physician duty to the prisoner-patient on one hand and the state on the other confounds bioethical practice as ethical adjudication can justify seemingly conflicting positions.

Modern military medicine involves physicians on the battlefield, and international humanitarian law protects them in accordance with the rules of war. The military doctor owes a duty to the soldier and civilian patient but also to the mission. In extreme circumstances, a military physician might use a weapon to defend a soldier, civilian patient, or themselves. As a relatively benign comparison, physicians may be hired by a sports team to protect the health of players but also to keep the player in the game . The player wants to play, and the physician advocates for their desire even if playing would compromise their health.

Physicians not under the employ of state corrections can be tasked with caring for prisoners as can non-military physicians be utilized to care for injured prisoners in war. An enemy combatant is owed specific protection when they fight within a recognized state army. When individuals fight as non-state combatants, as in the case of Hamas, they are not afforded the traditional protections of prisoners of war. The legal consensus on how to manage these actions remains under debate. Captured non-state combatants may be guilty of crimes and fall under the legal system’s jurisdiction for adjudicating such actions. Prisoners in Israel are entitled to medical care in a fashion like in the US. In both instances, because the prisoner is not at liberty and can present an ongoing danger to others, they are guarded and always restrained when they are receiving care in a civilian hospital that lacks the sort of security that might be present in a prison. Exceptions to physical restraint may occur when such actions directly interfere with patient care, but in that circumstance, a guard is present to guarantee the safety of the medical staff.

The physician-prisoner relationship is not a fiduciary one. From a legal perspective, it most closely resembles the relationship between a public health physician and a patient. In both cases, the physician’s duty is primarily to the health and safety of the community and not to the patient. Such a relationship does not permit subjecting the prisoner to cruelty but threading the needle of what we consider cruelty beyond incarceration is problematic. Restraint may need to be physical. The prisoner patient might not be permitted to use bathroom facilities and instead be required to use a diaper. They may be fed through a straw or a tube. Not only prisoners but sick ICU patients may also be restrained, be fed through a tube inserted via the nose or mouth into the stomach, and be required to relieve bladder and bowel functions directly into the hospital bed. Such circumstance is not advanced as desirable but is advanced and done as necessary. No one likes this. Not the doctor, not the nurse, not the patient, not the courts, not the public.

In discussion, qualitative words like “dignity” might be raised. Dignity can be many things, and even defecation into a bed can be dignified when properly understood. In the Israel-Hamas war, emotions are high, and doctors are subject to a complex and seemingly competing set of demands. Doctors are people, guided by an ethical principle to do right, but the additional danger faced by civilian doctors caring for Palestinian prisoners is the risk of being too close to the narrative. We teach doctors to utilize empathy when dealing with patients. This is poor advice. Empathy is easily weaponized against oneself or against others. The good torturer lacks empathy, but the excellent torturer is very empathic – if you want to make it hurt for someone else, you need to understand what the pain feels like to yourself. In place of empathy, the well-trained and practiced physician utilizes compassion. We have compassion for the patients we do not like as people, and we guard their interests but recognize in the case of a prisoner, the lack of liberty sets them into a different category of duty because the physician owes a vital and higher community duty. Such a duty does not set medical ethics aside. On the contrary, it upholds medical ethics. In these terrible circumstances, we place adherence to our values as our highest priority.

Joel Zivot is a practicing physician in anesthesiology and intensive care medicine and a senior fellow in ethics at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Zivot is a recognized expert who advocates against the use of lethal injection in the death penalty and is against the use of the tools of medicine as an arm of state power. Follow him on “X”/Twitter @joel_zivot

Treaty of Trianon concludes WWI between Allies and Hungary

On June 4, 1920, the Allies and Hungary signed the Treaty of Trianon , which concluded peace between the two sides after World War I. The treaty cost Hungary 72% of its territory, which went primarily to Romania, Czechoslovakia, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

US Supreme Court ruled wiretapping legal to secure evidence in police investigations

On June 4, 1928, in Olmstead v. United States , the US Supreme Court decided that wiretapping private telephone conversations to secure evidence was permissible. Learn more about the history surrounding the case and view the text of the decision.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

State of the World from NPR

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

A Visit to the Gateway for Ukrainian Prisoners of War Freed from Russia

Joanna Kakissis

Polina Lytvynova

The Ukrainian border town of Krasnopillia, in the country's northeast, is near the only open checkpoint between Ukraine and Russia. When Ukrainians are freed from Russian captivity, or when the bodies of dead Ukrainian soldiers are returned, they usually come through the town. Our correspondent visited and found the returning countrymen are always welcomed by residents and the staff from the town's scrappy local newspaper.

Demand, Supply, and Price in P.O.W. Camps Term Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Thesis statement, the main body.

The demand and supply illustrate the market dealings among the potential buyers and sellers of a given commodity. The two are supposed to establish the equilibrium price and amount sold in the trading setup. The supply and the demand model forecasts that the price works to ensure equality of the amount demanded by buyers and the amount supplied by the manufacturers leading to the achievement of a monetary price and quantity balance mostly in a competitive market.

The law of demand states that the increases in the price of a normal good lead to a decrease in quantity demanded of that good, all factors held or ceteris paribus and vice versa. On the other hand, the law of supply states that increases in the prices of a normal good will consequently lead to an increase in the amount supplied and vice versa when all other factors are held constant. In addition, the law of demand and supply dictates that the equilibrium price and amount of goods in the market lie at the meeting point of the buyer demand and the producer supply. At this point, the amount demanded =amount supplied, and prices remain stable at this level.

In the P.O.W. camp, the number of people living in a camp was around 1200 to 2500, and these people were prisoners or soldiers abducted to fight on behalf of other countries during the Second World War. These people lived in big houses and could socialize and trade with others. Therefore, the market setup was simple, and in most cases, the amount supplied kept on changing considering that the conditions of an effective trade were undesirable and these prisoners had to depend on their countries and Red Cross for their food and cigarettes supplies. Therefore, they had little control over the forces of demand and supply in their trading setup.

The paper attempts to investigate how the supply and the demand of the food and the cigarettes affected the price in the P.O.W. camp or at the time before and during the Second World War, considering that the market was not developed and the factors of holding an effective were unfavorable. Secondly, the currency system was undeveloped as many people depended on the barter trade to obtain food and cigarettes hence the forces of demand and supply were as there was no commodity that had a standard of value to be used as money, and many opted to use cigarettes which varied in size and quality. Therefore, the paper would like to explore how the amount supplied and demanded influenced the prices of the basic commodities in such a market set up and at a time when conditions for trade were unfavorable.

The amount supplied of both commodities tended to affect their respective prices. For instance, the cigarettes and the food packages were supplied on a weekly basis, mostly on Mondays. This caused the noneconomic demand for cigars to rise, and less elastic than the amount of food demanded. Hence the prices of these goods varied on a weekly basis where they would drop just before Sunday night and ascending stridently on a Monday morning. However, the problem would be solved by the people storing some of the commodities hence avoiding acute shortage.

Secondly, the arrival of new prisoners of war would basically lead to an increase in the amount demanded of cigarettes and food. For instance, intense air invasion of the camps led to the rise in noneconomic demand for cigars and a heightened general fall in the price of the two commodities. In addition, the good and the awful reports war, as well as the general expectations of new supplies or lack of supplies, would affect the price of a good, for example, in March of 1945, when prisoners were taking their breakfast, news spread through the camp of new arrivals of food and cigarettes supplies. Many people entered into a deal of selling their treacle share at four cigarettes or even three, however later, the gossip was rejected, and even a treacle for two cigars was difficult.

Thirdly, the variations in the price makeup are caused by the variations in the amount supplied of the two commodities. For example, the changes in the amount supplied in the German allocation range or the structure of the Red Cross packages would lead to variations in prices of one good relative to another. In scorching weather conditions, the price of cocoa falls while that of the soap rises.

The amount supplied of a close substitute similarly affects the price of food and cigarettes. At the same time, cigarettes had no close substitutes; however, there are many types of food, each with a close substitute. When the supplies of close substitutes increase, its prices will fall down and become affordable compared to the other good. For example, the Canadian butter and marmalade because of more value after being sufficiently supplied compared to a loss of value of the German jam and margarine due to reduced supply creating shortage hence rise therefore unaffordable.

The quantity supplied and demanded of the food and the cigarettes has had an influential impact on their respective prices in the P.O.W. camp. However, the impact on the prices of cigarettes was less elastic compared to that of the food. This is mainly because cigarettes were taken as a commodity of trade with the qualities of the money. These include the standard of value, store of value and medium of exchange, whereas food prices were highly responsive to the amount supplied and demanded as they have qualities of a normal good. Therefore, the prices of food were highly influenced by the supply and the demand compared to the cigarettes in P.O.W. camps.

Alan Griffiths &Stuart Wall, Intermediate Microeconomics, U.K.: Pearson Education Publisher, 2000.

Frank Cow ell, microeconomics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Radford R.A. “The economic organization of a P.O.W. camp,” London: Blackwell publishing corporation, 1945.

Samuelson, P. A. &William D. Nordhaus. Economics, 17th edition, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers, 2001.

- Highs and Lows of the Geneva Convention

- Human Rights Issues in Guantanamo Bay

- "Blackberry Winter" and "Powwow Highway"

- Community Journalism. Rising Gas Prices in Chicago

- Market Failures and Their Reasons

- Linking Small-Scale Farmers to Input-Output Markets

- Microeconomics. Poverty in America

- Doing Business in Saudi Arabia

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, October 26). Demand, Supply, and Price in P.O.W. Camps. https://ivypanda.com/essays/economics-supply-amp-demand-in-prisoner-of-war-camps/

"Demand, Supply, and Price in P.O.W. Camps." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/economics-supply-amp-demand-in-prisoner-of-war-camps/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Demand, Supply, and Price in P.O.W. Camps'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Demand, Supply, and Price in P.O.W. Camps." October 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/economics-supply-amp-demand-in-prisoner-of-war-camps/.

1. IvyPanda . "Demand, Supply, and Price in P.O.W. Camps." October 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/economics-supply-amp-demand-in-prisoner-of-war-camps/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Demand, Supply, and Price in P.O.W. Camps." October 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/economics-supply-amp-demand-in-prisoner-of-war-camps/.

- My View My View

- Following Following

- Saved Saved

Ukraine and Russia announce major prisoner swap

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Reporting by Anastasiia Malenko and Olena Harmash; Editing by Giles Elgood

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

World Chevron

Security tight in China and Hong Kong on Tiananmen crackdown anniversary

Security was tight and access restricted to Beijing's Tiananmen Square on Tuesday, the 35th anniversary of the June 4 crackdown, while Hong Kong also increased policing as activists in Taiwan and elsewhere prepared to mark the date with vigils.

Advertisement

Supported by

Ukraine Starts Freeing Some Prisoners to Join Its Military

Nearly 350 inmates have been freed under a new law that allows them to serve in exchange for the possibility of parole, the country’s justice minister said.

- Share full article

By Constant Méheut

Reporting from Kyiv, Ukraine

Ukraine has begun releasing prisoners to serve in its army, part of a wider effort to rebuild a military that has been depleted by more than two years of war and is strained by relentless Russian assaults.

Denys Maliuska, Ukraine’s justice minister, said in an interview on Friday that nearly 350 prisoners had already been freed under a law enacted last week that allows convicts to serve in the army in exchange for the possibility of parole at the end of their service.

The country’s courts must approve each prisoner’s bid to enlist, and Mr. Maliuska said that the judiciary was already considering most of the 4,300 applications submitted so far. Up to 20,000 such applicants, including people who were in pretrial detention, could be recruited to join the hundreds of thousands of soldiers already serving in Ukraine’s military, he said.

The policy echoes a practice widely used by Russia to bolster its forces, but differs in some ways. Russia’s program is open to prisoners convicted of violent crimes, while the Ukrainian law does not extend to people convicted of two or more murders, rape or other serious offenses.

Several Ukrainian lawmakers initially said that people convicted of premeditated murder would not be eligible. But Mr. Maliuska clarified on Friday that someone convicted of a single murder could be released, unless the crime was committed with aggravating circumstances such as sexual violence.

“There is some similarity, but I can’t say that this is the same as Russia did,” Mr. Maliuska said.

Ukraine had mocked Russia’s push to recruit prisoners in exchange for parole earlier in the war. But with the conflict now in its third year and with Ukrainian forces struggling all along the front line, Kyiv desperately needs more soldiers.

“The deficit of soldiers — of course, the difficulties with the draft of ordinary citizens — those were the main reasons for the law,” Mr. Maliuska said.

President Volodymyr Zelensky said in February that 31,000 Ukrainian soldiers had been killed in the war — a figure that is well below estimates by American officials, who said in August that nearly 70,000 Ukrainian soldiers had been killed at that point.

In recent months, Ukraine has stepped up border patrols to catch anyone trying to avoid being drafted and lowered the draft eligibility age to 25 from 27 . It has not drafted younger men, to avoid hollowing out an already small generation of men in their 20s, the result of a demographic crisis stretching back more than a century .

Most recently, Kyiv passed a law requiring all men of military age to ensure that the government had current details about their address and health status. Ukraine’s Defense Ministry said this week that about 700,000 people had updated their details on an online platform.

Ukraine’s urgent need for additional troops has become particularly apparent since Russian forces opened a new front in the northeast of the country two weeks ago, near the city of Kharkiv. The offensive by Moscow has stretched Ukrainian forces and compelled them to redeploy units from other hot spots of the front line, weakening their defenses there.

Gen. Oleksandr Syrsky, Ukraine’s commander in chief, said on Friday that Russian forces were trying to break through Ukrainian defenses in the southeastern Donetsk region.

Visiting Kharkiv on Friday, Mr. Zelensky also highlighted in a social media post the difficult situation in Vovchansk, a small town near the Russian border that Moscow’s troops have been attacking for the past two weeks, targeting it with heavy bombs and engaging in street fighting. Russian forces have captured about half of the town , according to Ukrainian officials.

This week, a court in the western city of Khmelnytsky said that it had freed more than 50 prisoners under the law allowing for the recruitment of inmates. It said that most of the prisoners who had applied for conditional release to join the military were young men convicted of theft, and that many had relatives and friends who had died in the war, motivating them to join the fight.

The move to recruit prisoners has drawn little criticism from the Ukrainian public, with many civilians and lawmakers saying that convicts have a duty to defend their country like any other citizen. They have also said that joining the military to fight against Russia is a chance for redemption.

“I believe that people who have not committed serious crimes, if they serve in special units, perhaps even on the front line, whether they dig trenches or build fortifications, why not,” Pavlo Litovkin, 31, a resident of Kyiv, said in an interview last week. “We should not imitate Russia’s methods of warfare, but we should manage our resources effectively.”