Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Harvard-led study IDs statin that may block pathway to some cancers

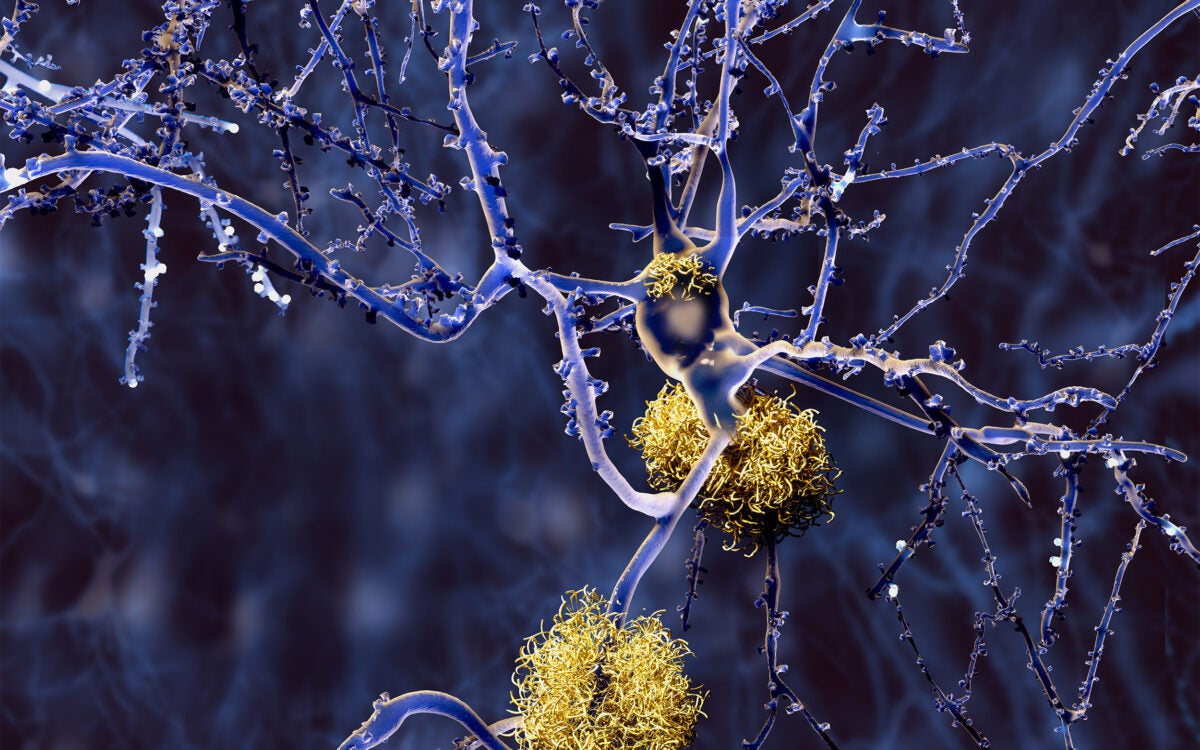

New Alzheimer’s study suggests genetic cause of specific form of disease

Had a bad experience meditating? You’re not alone.

When love and science double date.

Illustration by Sophie Blackall

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Sure, your heart thumps, but let’s look at what’s happening physically and psychologically

“They gave each other a smile with a future in it.” — Ring Lardner

Love’s warm squishiness seems a thing far removed from the cold, hard reality of science. Yet the two do meet, whether in lab tests for surging hormones or in austere chambers where MRI scanners noisily thunk and peer into brains that ignite at glimpses of their soulmates.

When it comes to thinking deeply about love, poets, philosophers, and even high school boys gazing dreamily at girls two rows over have a significant head start on science. But the field is gamely racing to catch up.

One database of scientific publications turns up more than 6,600 pages of results in a search for the word “love.” The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is conducting 18 clinical trials on it (though, like love itself, NIH’s “love” can have layered meanings, including as an acronym for a study of Crohn’s disease). Though not normally considered an intestinal ailment, love is often described as an illness, and the smitten as lovesick. Comedian George Burns once described love as something like a backache: “It doesn’t show up on X-rays, but you know it’s there.”

Richard Schwartz , associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and a consultant to McLean and Massachusetts General (MGH) hospitals, says it’s never been proven that love makes you physically sick, though it does raise levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that has been shown to suppress immune function.

Love also turns on the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is known to stimulate the brain’s pleasure centers. Couple that with a drop in levels of serotonin — which adds a dash of obsession — and you have the crazy, pleasing, stupefied, urgent love of infatuation.

It’s also true, Schwartz said, that like the moon — a trigger of its own legendary form of madness — love has its phases.

“It’s fairly complex, and we only know a little about it,” Schwartz said. “There are different phases and moods of love. The early phase of love is quite different” from later phases.

During the first love-year, serotonin levels gradually return to normal, and the “stupid” and “obsessive” aspects of the condition moderate. That period is followed by increases in the hormone oxytocin, a neurotransmitter associated with a calmer, more mature form of love. The oxytocin helps cement bonds, raise immune function, and begin to confer the health benefits found in married couples, who tend to live longer, have fewer strokes and heart attacks, be less depressed, and have higher survival rates from major surgery and cancer.

Schwartz has built a career around studying the love, hate, indifference, and other emotions that mark our complex relationships. And, though science is learning more in the lab than ever before, he said he still has learned far more counseling couples. His wife and sometime collaborator, Jacqueline Olds , also an associate professor of psychiatry at HMS and a consultant to McLean and MGH, agrees.

Spouses Richard Schwartz and Jacqueline Olds, both associate professors of psychiatry, have collaborated on a book about marriage.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

More knowledge, but struggling to understand

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago, but I don’t think it tells us very much that we didn’t already know about love,” Schwartz said. “It’s kind of interesting, it’s kind of fun [to study]. But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.”

Love and companionship have made indelible marks on Schwartz and Olds. Though they have separate careers, they’re separate together, working from discrete offices across the hall from each other in their stately Cambridge home. Each has a professional practice and independently trains psychiatry students, but they’ve also collaborated on two books about loneliness and one on marriage. Their own union has lasted 39 years, and they raised two children.

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago … But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.” Richard Schwartz, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

“I have learned much more from doing couples therapy, and being in a couple’s relationship” than from science, Olds said. “But every now and again, something like the fMRI or chemical studies can help you make the point better. If you say to somebody, ‘I think you’re doing this, and it’s terrible for a relationship,’ they may not pay attention. If you say, ‘It’s corrosive, and it’s causing your cortisol to go way up,’ then they really sit up and listen.”

A side benefit is that examining other couples’ trials and tribulations has helped their own relationship over the inevitable rocky bumps, Olds said.

“To some extent, being a psychiatrist allows you a privileged window into other people’s triumphs and mistakes,” Olds said. “And because you get to learn from them as they learn from you, when you work with somebody 10 years older than you, you learn what mistakes 10 years down the line might be.”

People have written for centuries about love shifting from passionate to companionate, something Schwartz called “both a good and a sad thing.” Different couples experience that shift differently. While the passion fades for some, others keep its flames burning, while still others are able to rekindle the fires.

“You have a tidal-like motion of closeness and drifting apart, closeness and drifting apart,” Olds said. “And you have to have one person have a ‘distance alarm’ to notice the drifting apart so there can be a reconnection … One could say that in the couples who are most successful at keeping their relationship alive over the years, there’s an element of companionate love and an element of passionate love. And those each get reawakened in that drifting back and forth, the ebb and flow of lasting relationships.”

Children as the biggest stressor

Children remain the biggest stressor on relationships, Olds said, adding that it seems a particular problem these days. Young parents feel pressure to raise kids perfectly, even at the risk of their own relationships. Kids are a constant presence for parents. The days when child care consisted of the instruction “Go play outside” while mom and dad reconnected over cocktails are largely gone.

When not hovering over children, America’s workaholic culture, coupled with technology’s 24/7 intrusiveness, can make it hard for partners to pay attention to each other in the evenings and even on weekends. It is a problem that Olds sees even in environments that ought to know better, such as psychiatry residency programs.

“There are all these sweet young doctors who are trying to have families while they’re in residency,” Olds said. “And the residencies work them so hard there’s barely time for their relationship or having children or taking care of children. So, we’re always trying to balance the fact that, in psychiatry, we stand for psychological good health, but [in] the residency we run, sometimes we don’t practice everything we preach.”

“There is too much pressure … on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. … Of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.” Jacqueline Olds, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

All this busy-ness has affected non-romantic relationships too, which has a ripple effect on the romantic ones, Olds said. A respected national social survey has shown that in recent years people have gone from having three close friends to two, with one of those their romantic partner.

More like this

Strength in love, hope in science

Love in the crosshairs

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

“Often when you scratch the surface … the second [friend] lives 3,000 miles away, and you can’t talk to them on the phone because they’re on a different time schedule,” Olds said. “There is too much pressure, from my point of view, on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. There’s just so much pressure on the role of spouse that of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.”

Since the rising challenges of modern life aren’t going to change soon, Schwartz and Olds said couples should try to adopt ways to fortify their relationships for life’s long haul. For instance, couples benefit from shared goals and activities, which will help pull them along a shared life path, Schwartz said.

“You’re not going to get to 40 years by gazing into each other’s eyes,” Schwartz said. “I think the fact that we’ve worked on things together has woven us together more, in good ways.”

Maintain curiosity about your partner

Also important is retaining a genuine sense of curiosity about your partner, fostered both by time apart to have separate experiences, and by time together, just as a couple, to share those experiences. Schwartz cited a study by Robert Waldinger, clinical professor of psychiatry at MGH and HMS, in which couples watched videos of themselves arguing. Afterwards, each person was asked what the partner was thinking. The longer they had been together, the worse they actually were at guessing, in part because they thought they already knew.

“What keeps love alive is being able to recognize that you don’t really know your partner perfectly and still being curious and still be exploring,” Schwartz said. “Which means, in addition to being sure you have enough time and involvement with each other — that that time isn’t stolen — making sure you have enough separateness that you can be an object of curiosity for the other person.”

Share this article

You might like.

Cholesterol-lowering drug suppresses chronic inflammation that creates dangerous cascade

Findings eventually could pave way to earlier diagnosis, treatment, and affect search for new therapies

Altered states of consciousness through yoga, mindfulness more common than thought and mostly beneficial, study finds — though clinicians ill-equipped to help those who struggle

Six receive honorary degrees

Harvard recognizes educator, conductor, theoretical physicist, advocate for elderly, writer, and Nobel laureate

When should Harvard speak out?

Institutional Voice Working Group provides a roadmap in new report

Day to remember

One journey behind them, grads pause to reflect before starting the next

- CONTACT A LOCATION

- REQUEST APPOINTMENT

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- View Locations

© 2014 Riordan Clinic All Rights Reserved

- High Dose IV Vitamin C (IVC)

- Integrative Medicine

- Integrative Oncology

The Research on Love: A Psychological, Scientific Perspective on Love

Dr. Nina Mikirova

And now here is this topic about love, the subject without which no movie, novel, poem or song can exist. This topic has fascinated scientists, philosophers, historians, poets, playwrights, novelists, and songwriters. I decided to look at this subject from a scientific point of view. It was very interesting to research and to write this article, and I am hoping it will be interesting to you as a reader.

Whereas psychological science was slow to develop active interest in love, the past few decades have seen considerable growth in research on the subject. The following is a comprehensive review of the central and well-established findings from psychologically-informed research on love and its influence in adult human relationships as presented in the article: “Love. What Is It, Why Does It Matter, and How Does It Operate?” by H. Reis and A. Aron. A brief summary of the ideas from this article is presented below.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF LOVE RESEARCH

Most popular contemporary ideas about love can be traced to the classical Greek philosophers. Prominent in this regard is Plato’s Symposium. It is a systematic and seminal analysis whose major ideas

have probably influenced contemporary work on love more than all subsequent philosophical work combined. However, four major intellectual developments of the 19th and 20th centuries provided key insights that helped shape the agenda for current research and theory of love.

The first of these was led by Charles Darwin, who proposed that reproductive success was the central process underlying the evolution of species. Evolutionary theorizing has led directly to such currently popular concepts as mate preference, sexual mating strategies, and attachment, as well as to the adoption of a comparative approach across species.

A second important figure was Sigmund Freud. He introduced many psychodynamic principles, such as the importance of early childhood experiences, the powerful impact of motives operating outside of awareness, the role of defenses in shaping the behavioral expression of motives, and the role of sexuality as a force in human behavior.

A third historically significant figure was Margaret Mead. Mead expanded awareness with vivid descriptions of cultural variations in the expression of love and sexuality. This led researchers to consider the influence of socialization and to recognize cultural variation in many aspects of love.

The emerging women’s movement during the 1970s also contributed to a cultural climate that made the study of what had been traditionally thought of as ‘‘women’s concerns’’ not only acceptable, but in fact necessary for the science of human behavior. At the same time, a group of social psychologists were beginning their work to show that adult love could be studied experimentally and in the laboratory.

WHAT’S PSYCHOLOGY GOT TO DO WITH LOVE

What is Love? According to authors, Reis and Aron, love is defined as a desire to enter, maintain, or expand a close, connected, and ongoing relationship with another person. Considerable evidence supports a basic distinction, first offered in 1978, between passionate love (“a state of intense longing for union with another”) and other types of romantic love, labeled companionate love (“the affection we feel for those with whom our lives are deeply entwined”).

The evidence for this distinction comes from a variety of research methods, including psychometric techniques, examinations of the behavioral and relationship consequences of different forms of romantic love, and biological studies, which are discussed in this article. Most work has focused on identifying and measuring passionate love and several aspects of romantic love, which include two components: intimacy and commitment. Some scholars see companionate love as a combination of intimacy and commitment, whereas others see intimacy as the central component, with commitment as a peripheral factor (but important in its own right, such as for predicting relationship longevity).

In some studies, trust and caring were considred highly prototypical of love, whereas uncertainty and butterflies in the stomach were more peripheral.

Passionate and companionate love solves different adaptation problems. Passionate love may be said to solve the attraction problem—that is, for individuals to enter into a potentially long-term mating relationship, they must identify and select suitable candidates, attract the other’s interest, engage in relationship-building behavior, and then go about reorganizing existing activities and relationships so as to include the other. All of this is strenuous, time-consuming, and disruptive. Consequently, passionate love is associated with many changes in cognition, emotion, and behavior. For the most part, these changes are consistent with the idea of disrupting existing activities, routines, and social networks to orient the individual’s attention and goal-directed behavior toward a specific new partner.

Considerably less study has been devoted to understanding the evolutionary significance of the intimacy and commitment aspects of love. However, much evidence indicates that love in long-term relationships is associated with intimacy, trust, caring, and attachment; all factors that contribute to the maintenance of relationships over time. More generally, the term companionate love may be characterized by communal relationship; a relationship built on mutual expectations that oneself and a partner will be responsive to each other’s needs.

It was speculated that companionate love, or at least the various processes associated with it, is responsible for the noted association among social relatedness, health, and well-being. In a recent series of papers, it was claimed that marriage is linked to health benefits. Having noted the positive functions of love, it is also important to consider the dark side. That is, problems in love and love relationships are a significant source of suicides, homicides, and both major and minor emotional disorders, such as anxiety and depression. Love matters not only because it can make our lives better, but also because it is a major source of misery and pain that can make life worse.

It is also believed that research will address how culture shapes the experience and expression of love. Although both passionate and companionate love appear to be universal, it is apparent that their manifestations may be moderated by culture-specific norms and rules.

Passionate love and companionate love has profoundly different implications for marriage around the world, considered essential in some cultures but contraindicated or rendered largely irrelevant in others. For example, among U.S. college students in the 1960s, only 24% of women and 65% of men considered love to be the basis of marriage, but in the 1980s this view was endorsed by more than 80% of both women and men.

Finally, the authors believe that the future will see a better understanding of what may be the quintessential question about love: How this very individualistic feeling is shaped by experiences in interaction with particular others.

Related Health Hunter News Articles

Dark Chocolate Avocado Spinach Brownies

Trauma, Cancer, & Disease

Recipe: Salmon with Garlic “Cream” Sauce Over Cauliflower Rice

- Shop Nutrients

- ORDER LAB tests

You can see how this popup was set up in our step-by-step guide: https://wppopupmaker.com/guides/auto-opening-announcement-popups/

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Regulation of Romantic Love Feelings: Preconceptions, Strategies, and Feasibility

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Missouri–St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, United States of America, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, United States of America

Affiliation Institute of Psychology, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Sandra J. E. Langeslag,

- Jan W. van Strien

- Published: August 16, 2016

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087

- Reader Comments

Love feelings can be more intense than desired (e.g., after a break-up) or less intense than desired (e.g., in long-term relationships). If only we could control our love feelings! We present the concept of explicit love regulation, which we define as the use of behavioral and cognitive strategies to change the intensity of current feelings of romantic love. We present the first two studies on preconceptions about, strategies for, and the feasibility of love regulation. Questionnaire responses showed that people perceive love feelings as somewhat uncontrollable. Still, in four open questions people reported to use strategies such as cognitive reappraisal, distraction, avoidance, and undertaking (new) activities to cope with break-ups, to maintain long-term relationships, and to regulate love feelings. Instructed up-regulation of love using reappraisal increased subjective feelings of attachment, while love down-regulation decreased subjective feelings of infatuation and attachment. We used the late positive potential (LPP) amplitude as an objective index of regulation success. Instructed love up-regulation enhanced the LPP between 300–400 ms in participants who were involved in a relationship and in participants who had recently experienced a romantic break-up, while love down-regulation reduced the LPP between 700–3000 ms in participants who were involved in a relationship. These findings corroborate the self-reported feasibility of love regulation, although they are complicated by the finding that love up-regulation also reduced the LPP between 700–3000 ms in participants who were involved in a relationship. To conclude, although people have the preconception that love feelings are uncontrollable, we show for the first time that intentional regulation of love feelings using reappraisal, and perhaps other strategies, is feasible. Love regulation will benefit individuals and society because it could enhance positive effects and reduce negative effects of romantic love.

Citation: Langeslag SJE, van Strien JW (2016) Regulation of Romantic Love Feelings: Preconceptions, Strategies, and Feasibility. PLoS ONE 11(8): e0161087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087

Editor: Alexandra Key, Vanderbilt University, UNITED STATES

Received: March 8, 2016; Accepted: July 31, 2016; Published: August 16, 2016

Copyright: © 2016 Langeslag, van Strien. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Our data cannot be made publicly available for ethical reasons. That is, participants were not asked for permission for their data to be shared. Parts of the data are available on request. Please send requests to Sandra Langeslag ( [email protected] ).

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Romantic love strikes virtually everyone at least once (i.e., its lifetime prevalence approaches 100%) [ 1 ] and has a great impact on our lives. Romantic love has positive effects on individuals and society as a whole. For example, love is associated with positive emotions such as euphoria [ 2 ] and romantic relationships enhance happiness and life satisfaction [ 3 ]. But love also has a negative impact on individuals and society. For example, love is associated with stress [ 4 ] and jealousy [ 5 ], and romantic break-ups are associated with sadness and shame [ 6 ], a decrease in happiness and life satisfaction [ 7 ], and depression [ 8 ]. The high prevalence of love combined with its significant positive and negative impact on individuals and society make it an important research topic.

The word ‘love’ has many different meanings and may have different meanings to different people. Researchers have proposed several taxonomies of love, with various numbers of love types or components [ 9 – 13 ]. In this study, two types of love feelings are considered: infatuation and attachment. Infatuation is the overwhelming, amorous feeling for one individual, and is similar to the concepts ‘passion’ or ‘infatuated love’ [ 10 ], ‘romantic love’ [ 11 ], ‘passionate love’ [ 12 ], and ‘attraction’ [ 13 ]. Attachment, on the other hand, is the comforting feeling of emotional bonding with another individual, and is similar to the concepts ‘intimacy’ with ‘decision/commitment’ [ 10 ], and ‘companionate love’ [ 10 – 12 ].

Love feelings are sometimes weaker than desired. Infatuation is typically most intense at the early stages of love after which it decreases relatively quickly [ 13 – 15 ] and attachment takes some time to develop [ 13 – 15 ] after which it decreases over the course of decades [ 16 ]. The decrease of infatuation and attachment over time threatens the stability of romantic relationships. Indeed, falling out of love is the primary reason for divorce [ 17 ]. Love feelings can also be stronger than desired. People may, for example, be in love with someone who does not love them back or who has broken up with them. Clearly, it would be advantageous if we could regulate love feelings at will, so that we could up-regulate them when they are weaker than desired, and down-regulate them when they are stronger than desired.

We define love regulation as the use of behavioral or cognitive strategies to change the intensity of current feelings of romantic love. In an interview study, participants reported that their love feelings were involuntary and uncontrollable [ 2 ]. Nevertheless, three lines of research suggest that love regulation may actually be feasible. First, it is well known that people can regulate their emotions [ 18 – 21 ], which entails generating new emotions or changing the intensity of current emotions using behavioral or cognitive strategies [ 20 ]. There are multiple emotion regulation strategies, including situation selection, distraction, expression suppression, and cognitive reappraisal. Situation selection is to avoid or seek out certain situations to change the way you feel (e.g., attending a party to have fun) [ 21 ]. Distraction entails performing a secondary task to reduce the intensity of emotions (e.g., playing a video game to forget about a bad incident at work) [ 20 ]. Expression suppression involves inhibiting the expression of an emotion (e.g., keeping a poker face) [ 22 ]. Cognitive reappraisal involves reinterpreting the situation to change the way you feel (e.g., decreasing or increasing nervousness by reinterpreting an upcoming job interview as an opportunity to learn more about the company or as a once in a lifetime opportunity, respectively) [ 22 ]. Emotion regulation can be used to up- and down-regulate positive and negative emotions [ 23 ] and may happen implicitly or explicitly [ 18 ].

However, love is sometimes considered a motivation (or drive) rather than an emotion [ 24 ]. One reason why love would not be an emotion is that it elicits different emotions depending on the situation. Reciprocated love, for example, may elicit the emotion euphoria, while unreciprocated love may elicit the emotion sadness. It is therefore important that a second line of research has shown that people can use cognitive strategies to regulate their motivations, including sexual arousal [ 25 ], excitement about monetary reward [ 26 – 29 ], and craving for alcohol, food, and cigarettes [ 30 , 31 ]. The evidence that motivations can be regulated intentionally supports the idea that explicit love regulation may be feasible.

Finally, a third research line has shown that people think more favorably of their romantic partner than objectively justified [ 32 , 33 ]. Importantly, people who idealize their partner and whose partners idealize them have happier relationships [ 34 ]. These findings suggest that implicit up-regulation of love feelings for the current romantic partner is feasible and that it contributes to relationship satisfaction.

Even though this last research line shows that people can regulate their love feelings implicitly, there are no studies that provide information about the deliberate, explicit up- and down-regulation of love feelings. In two studies, we systematically examined preconceptions about, strategies for, and the feasibility of explicit regulation of love feelings. The first goal was to determine whether people think that love feelings can be controlled or not. Participants answered a series of questions that measured perceived control over love feelings and previous research [ 2 ] led us to hypothesize that people would perceive love feelings as uncontrollable. The second goal was to reveal which strategies people use when they try to up- and down-regulate their love feelings. Participants responded to four open questions and we expected that people would report the use of typical behavioral and cognitive emotion regulation strategies mentioned above. First, we conducted a pilot study (Study 1) and then we conducted another study (Study 2) to confirm the findings of the pilot study.

In addition, Study 2 employed a love regulation task to achieve the final research goal, which was to examine if people can intentionally up- and down-regulate love feelings. In this first empirical test of the feasibility of love regulation, we focused on the reappraisal strategy because it is considered effective in altering feeling intensity and beneficial for cognitive and social functioning [ 21 ]. Situation-focused reappraisal entails changing the emotional meaning of a situation by reinterpreting it [ 21 ], for example by focusing on positive or negative aspects of the situation, or by imagining a positive or negative outcome [ 35 ]. The use of cognitive reappraisal to regulate love feelings is related to the notion that cognitive processes, including making attributions, are associated with relationship satisfaction [ 36 , 37 ]. We focus on the intensity of infatuation and attachment rather than relationship outcomes, since love feelings do not occur exclusively in the context of romantic relationships [ 14 ].

Because it depends on the situation whether people would benefit from love up- or down-regulation, we tested a group of people who were involved in a romantic relationship and a group of people who had recently experienced a romantic break-up. People who are currently in a romantic relationship were expected to benefit from love up-regulation, because that would stabilize their relationship. People who have just experienced a break-up, in contrast, would benefit from love down-regulation, because that could help them cope with the break-up. Because previous research has shown that intense feelings of romantic love can be elicited by viewing pictures of the beloved [ 38 ], pictures of the (ex-)partner were used to elicit feelings of love, which participants were instructed to regulate in an explicit regulation task. Because self-reports are the only way to assess phenomenology (i.e., how someone feels) [ 39 ], participants rated how infatuated and how attached they felt after each regulation condition. It was hypothesized that love up-regulation would increase feelings of infatuation and attachment, whereas love down-regulation would decrease feelings of infatuation and attachment in both groups. It is of course important to dissociate between the concept of love regulation and the well-established concept of emotion regulation. Therefore, participants also rated how negative or positive they felt after each regulation condition. It was expected that love up-regulation would make the relationship group feel more positive, while love down-regulation would make them feel more negative. The opposite pattern was expected for the break-up group: feeling more negative following up-regulation and more positive following down-regulation. This hypothesis shows how love regulation is theoretically distinct from emotion regulation. That is, love regulation targets the intensity of love feelings rather than emotions. Of course, the change in love feelings may in turn influence emotions or affect. The direction of the effect of love regulation on emotion or affect may differ depending on the context, as indicated by the hypothesized opposite effects of love regulation on emotion/affect in the relationship and break-up groups.

Even though self-reports gain a unique insight into what people experience, they also suffer from social desirability biases and demand characteristics [ 40 , 41 ]. Therefore, in addition to subjective self-reports, we used event-related potentials (ERPs) as a more objective measure of love regulation success. ERPs have been used before to study emotion regulation and to study romantic love, but not to study love regulation. The late positive potential (LPP) reflects multiple and overlapping positivies over the posterior scalp beginning in the time range of the classic P300, i.e., around 300 ms after stimulus onset. The LPP amplitude is typically enhanced for negative and positive compared to neutral stimuli [ 19 ] and is therefore thought to reflect the affective and motivational intensity of information and the resulting motivated attention [ 42 ]. Correspondingly, we have shown that the LPP is enhanced in response to pictorial and verbal beloved-related information compared to control information [ 32 , 43 , 44 ]. Importantly, the LPP amplitude is modulated by emotion regulation instructions according to the regulatory goal: emotion down-regulation reduces the LPP amplitude, while emotion up-regulation enhances the LPP amplitude [ 27 , 45 – 49 ]. The LPP amplitude can therefore be used as an objective measure of regulation success [ 19 ]. Because the LPP reflects affective and motivational significance and the resulting motivated attention, rather than valence [ 42 ], regulation effects in the LPP amplitude reflect how regulation changes the affective and motivational intensity of information and the amount of motivated attention allocated to that information. It was expected that love up-regulation would enhance the LPP in response to pictures of the (ex-)partner in both groups, which would indicate that love up-regulation would enhance the affective and motivational significance of, and the resulting motivated attention to the (ex-)partner. Love down-regulation, in contrast, was expected to reduce the LPP amplitude to (ex-)partner pictures in both groups, which would indicate that love down-regulation would reduce the affective and motivational significance of, and the resulting motivated attention to the (ex-)partner.

Study 1 –Methods

Participants.

Thirty-two participants (18–30 yrs, M = 21.4, 7 men) who were in love by self-report were recruited from the University of Maryland community in the US. Being in love was an inclusion criterion because some of the questions assessing perceived control over love feelings (see below) contained a blank in which the participants had to mentally insert the name of their beloved. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland and written informed consent was obtained. Participants were remunerated with $10.

First, participants completed some questions about their love feelings and their romantic relationship [ 44 ]. Participants also completed the Infatuation and Attachment Scales (IAS) [ 14 ], and the Passionate Love Scale (PLS) [ 50 ] to assess the intensity of infatuation and attachment. Then, participants completed 17 questions to assess perceived control of love feelings (Cronbach’s alpha = .93), see the S1 Appendix . These questions were phrased to measure perceived control over love in general, and over infatuation and attachment specifically. They were also phrased to measure perceived control over one’s own vs. people’s love feelings, and over the intensity and object of love feelings. Participants responded using a 9-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 9 = totally agree).

Subsequently, participants answered four open questions about the use of behavioral and cognitive strategies in the contexts of heartbreak and long-term relationships. We distinguished between emotion regulation and love down-regulation in the context of heartbreak by asking two questions: “What do you do or think to feel better when you have a broken heart?” (i.e., emotion regulation), “What do you do or think to decrease feelings of love when you have a broken heart?” (i.e., love down-regulation). In addition, we distinguished between maintaining relationships and love up-regulation in the context of long-term relationships by asking two questions: “What do you do or think to maintain a long-term relationship?” (i.e., maintaining relationships), and “What do you do or think to prevent that feelings of love decline in a long-term relationship?” (i.e., love up-regulation). If participants had not experienced heartbreak or any long-term relationships, they replied with what they think they would do in those circumstances.

The mean score on the 17 perceived control questions was subjected to a one-sample t -test against 5, to test if it differed from neutral. In addition, responses on subsets of the 17 questions that measured perceived control over a certain aspect of love were averaged to obtain measures of perceived control over seven different aspects of love (love in general, infatuation, attachment, self, people in general, intensity of love, and object of love). Five paired sample t -tests were conducted to test for differences in perceived control between related aspects of love (i.e., love in general vs. infatuation, love in general vs. attachment, infatuation vs. attachment, self vs. people in general, and intensity vs. object of feelings).

The responses to the four open strategy questions were analyzed qualitatively. Many participants listed multiple strategies in response to each of the four open strategy questions. Each strategy was scored as being an exemplar of a certain category. A priori categories were emotion regulation strategies such as reappraisal, distraction, and suppression [ 20 , 21 ]. In the heartbreak context, reappraisal was subdivided into “focus on the negative aspects of the beloved/relationship”, “think of negative future scenarios”, “think about the positive aspects of the situation”, and “other”. In the long-term relationship context, reappraisal was subdivided into “focus on the positive aspects of the beloved/relationship”, and “think of positive future scenarios”. Other categories such as avoidance (see Tables 1 and 2 ) were added on the basis of participants’ responses.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.t002

Study 1 –Results

Participant characteristics.

All participants had an opposite-sex beloved. Twenty-seven (84%) of the participants reported to be in a relationship with their beloved, which supports the idea that love does not occur exclusively in the context of relationships [ 14 ]. See Table 3 for the other love characteristics.

Means (ranges in parentheses).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.t003

Perceived control

The mean score on the 17 perceived control questions was 4.5 ( SD = 1.4). A one-sample t -test revealed that this tended to be lower than 5 (= neutral), t (31) = -1.9, p = .066, which implies that participants perceive love feelings as neither controllable, nor uncontrollable, or as somewhat uncontrollable, if anything. See Table 4 for the mean perceived control over the seven different aspects of love. Participants felt more in control of feelings of attachment than infatuation, t (31) = 2.4, p = .022. There was no difference between the perceived control over the own vs. people’s feelings, t (31) = 0.5, p = .64. Participants felt more control over the intensity than the object of their love feelings, t (31) = 2.1, p = .047.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.t004

See Tables 1 and 2 for the regulation strategies reported. In the context of heartbreak, participants mostly used distraction, social support, and reappraisal. Distraction (e.g., watching TV, listening to music, focusing on work or school, or exercise) and seeking social support (e.g., talking to or spending time with family/friends) were used more to feel better than to decrease love feelings. In contrast, reappraisal was used more to decrease love feelings than to feel better. Reappraisal by focusing on negative aspects of the beloved was the most popular reappraisal strategy. Examples of other reappraisal strategies were thinking that time will heal, finding someone else to love, or focusing on positive aspects of oneself or one’s life. Thinking about positive aspects of the situation (e.g., focusing on the advantages of being single or being hopeful for the future), as well as avoidance (i.e., not talking about the beloved, getting rid of all pictures, and eliminating all contact) were moderately popular strategies to decrease love feelings. Strategies such as reappraisal by thinking about negative future scenarios (“it just wasn’t meant to last”), eating/smoking, and expressing emotions (“cry”) were used least often. None of the participants reported the use of suppression. Two participants reported that they did not, or could not, decrease love feelings.

In the context of long-term relationships, participants stressed the importance of communication/honesty and undertaking (new) activities with their beloved. Communication/honesty was deemed important for maintaining long-term relationships, whereas undertaking (new) activities with the beloved, which is a situation selection strategy, was mostly used to prevent love feelings from declining. Other strategies such as expressing love feelings to the beloved, trust, spending (quality) time with the beloved, loving unconditionally/making compromises, the two reappraisal strategies, and spending time apart from the beloved were mentioned as well. Six participants stated that love feelings would not decline if the relationship was good and/or that they would end the relationship if love feelings would decline.

In short, several behavioral and cognitive strategies were used in the contexts of heartbreak and long-term relationships. Some of these strategies were the typical cognitive and behavioral emotion regulation strategies, such as reappraisal, distraction, and situation selection. While some strategies seemed specific for feeling better during heartbreak or for maintaining long-term relationships, strategies such as reappraisal by focusing on negative aspects of the beloved or the relationship and undertaking (new) activities with the beloved seemed specific for down- and up-regulation of love feelings, respectively.

Interim Discussion

The results of this first exploratory study show that people perceive love feelings as neither controllable, nor uncontrollable (or as somewhat uncontrollable, if anything). People did perceive more control over some aspects of love than others and the majority of people reported to use a variety of strategies when heartbroken or when in a long-term relationship. Some strategies seemed specific for changing the intensity of love feelings, rather than for regulating emotions or maintaining relationships. Because this was only a pilot study with mostly female participants, we conducted a follow-up study (Study 2) to replicate and confirm these preliminary findings in a more gender-balanced sample. As mentioned in the introduction, Study 2 also included a love regulation task to test the feasibility of love regulation.

Study 2 –Methods

Twenty participants who were in a romantic relationship (19–25 yrs, M = 21.7, 10 men) and 20 participants who had recently experienced a romantic break-up (19–26 yrs, M = 21.9, 10 men) were recruited from the Erasmus University Rotterdam community in The Netherlands. For brevity, we will use the words ‘partner’ and ‘relationship’ in the remainder of the paper regardless of whether the relationship was ongoing or had dissolved. Inclusion criteria were normal or corrected to-normal vision, right-handedness (as determined by a hand preference questionnaire [ 51 ]), no use of medication known to affect the central nervous system, and no mental disorders. The reason for excluding participants with mental disorders was that many mental disorders are associated with emotion dysregulation [ 23 ], which indicates that love regulation may also be different in patients than in healthy controls. Four participants had to be excluded from the EEG analyses because of experimenter error during the EEG recording ( n = 3) or too many artifacts ( n = 1, more information below). Therefore the EEG analyses are based on 18 participants who were in a romantic relationship (19–25 yrs, M = 21.8, 9 men) and 18 participants who had recently experienced a romantic break-up (19–26 yrs, M = 21.7, 8 men). The study was approved by the Psychologie Ethische Commissie of the Erasmus Universiteit Rottterdam and written informed consent was obtained. Participants were remunerated with course credit or €15.

Questionnaires

In addition to the questions about their love feelings and their romantic relationship [ 44 ], the 17 perceived control questions (Cronbach’s alpha = .92), the four open regulation strategy questions, the Infatuation and Attachment Scales (IAS) [ 14 ], and the Passionate Love Scale (PLS) [ 50 ] used in Study 1, participants completed the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) [ 22 ] to assess individual differences in the habitual use of reappraisal and suppression. Participants also completed the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedules (PANAS) twice, once about the last two weeks and once about this moment [ 52 ].

Participants provided 30 digital pictures of their partner. There were no other requirements than that the pictures had to contain the partner. Therefore, the pictures could display parts of the partner (e.g., just the face) or the whole body of the partner, people other than the partner, a variety of facial expressions, objects, and scenery. The pictures were presented to elicit love feelings [ 38 ] and to help the participant come up with negative or positive aspects of the partner/relationship and future scenarios (see below). It is important to note that the variety of information on the pictures does not confound the effects of regulation, because the same 30 partner pictures were presented in each regulation condition. For the same reason, differences in picture content between the two groups could not confound the differences in regulation effects between groups. In addition, the pictures ensure high ecological validity, as the partner is typically encountered in a wide variety of contexts and with varying facial expressions. The neutral stimuli were 30 neutral pictures displaying humans from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) [ 53 ] with neutral normative valence ( M = 5.4, SD = 0.5) and low normative arousal ( M = 3.5, SD = 0.5) ratings, see S1 Text .

Love regulation task

Participants completed a love regulation task, see Fig 1 , while their electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded. In the first two blocks, participants passively viewed partner and neutral pictures (order counterbalanced between participants). In the third and fourth block, participants were instructed to up- and down-regulate their love feelings in response to the partner pictures (order counterbalanced between participants) using reappraisal. Up-regulation instructions were to increase love feelings by thinking about positive aspects of the partner (e.g., “He is so funny”) or relationship (e.g., “We get along so well”), or positive future scenarios (e.g., “We’ll get married”). Down-regulation instructions were to decrease love feelings by thinking about negative aspects of the partner (e.g., “She is so lazy”) or relationship (e.g., “We often fight”), or negative future scenarios (e.g., “We won’t stay together forever”). Participants could use the information in the picture for inspiration. For example, the partner wearing a yellow shirt and standing next to a friend on a picture could inspire the participant to up-regulate love feelings by thinking “I love that yellow shirt he’s wearing” and to down-regulate love feelings by thinking “He is always hitting on that friend, and he might cheat on me one day”. These are instructions of situation-focused reappraisal, which involves reinterpreting “the nature of the events themselves, reevaluating others’ actions, dispositions, and outcomes” rather than self-focused reappraisal, which involves altering “the personal relevance of events” ([ 35 ], p. 484). That is, focusing on negative/positive aspects of the partner involves a reevaluation of the partner’s dispositions (“My partner is a wonderful person” when focusing on positive aspects vs. “My partner is a terrible person” when focusing on negative aspects), focusing on negative/positive aspects of the relationship involves a reevaluation of the relationship (“I am/was in a good relationship” when focusing on positive aspects, and “I am/was in a bad relationship” when focusing on negative aspects), and imagining positive/negative future relationship scenarios involves reevaluation of outcomes.

Please note that the stimulus in this figure is not actually one of the pictures that were submitted by the participants. Instead, it is an IAPS picture [ 53 ] that resembles the kinds of pictures that participants submitted.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g001

Each block started with an instruction word (‘view’, ‘increase’, ‘decrease’) for 4 sec and consisted of 30 trials. Trial structure was: fixation cross for 900–1100 ms, picture for 3 sec, and blank screen for 2 sec. After each block, participants completed four ratings on a 1–5 scale: infatuation, attachment, valence, and arousal, and they also completed the PANAS at this moment [ 52 ]. After the regulation task, participants wrote down what they had thought to up- and down-regulate love feelings to verify that they had followed the instructions.

EEG recording and preprocessing

The EEG was recorded using a 32-channel amplifier and data acquisition software (ActiveTwoSystem, BioSemi). The 32 Ag-AgCl active electrodes were placed upon the scalp by means of a head cap (BioSemi), according to the 10–20 International System. Vertical electro-oculogram and horizontal electro-oculogram were recorded by attaching additional electrodes (UltraFlat Active electrodes, BioSemi) above and below the left eye, and at the outer canthi of both eyes. Another two electrodes were attached to the left and right mastoids. An active electrode (common mode sense) and a passive electrode (driven right leg) were used to comprise a feedback loop for amplifier reference. All signals were digitized with a sampling rate of 512 Hz, a 24 bit A/D conversion and a low pass filter of 134 Hz. The EEG data were analyzed with BrainVision Analyzer 2 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). Per participant, a maximum of one bad electrode included in the analyses (see below) was corrected using spherical spline topographic interpolation. Offline, an average mastoids reference was applied and the data were filtered using a 0.1–30 Hz band pass filter (phase shift-free Butterworth filters; 24 dB/octave slope) and a 50 Hz notch filter. Data were segmented in epochs from 200 ms pre-stimulus until 3000 ms post-stimulus onset. Ocular artifact correction was applied semi-automatically according to the Gratton and Coles algorithm [ 54 ]. The 200 ms pre-stimulus period was used for baseline correction. Artifact rejection was performed at individual electrodes with the criterion minimum and maximum baseline-to-peak -75 to +75 μV. Because at least 12 trials are needed to adequately estimate emotion regulation effects in the LPP amplitude [ 55 ], the one participant that had fewer than 12 trials left per electrode per condition was excluded from the EEG analyses, as mentioned above. At the three electrodes used in the analyses (see below), the average number of accepted trials per condition ranged from 29.5 to 29.8 out of 30.

Statistical analyses

Questionnaire scores were analyzed with independent samples t -tests to test for differences between groups (adjusted t , df , and p values are shown when the Levene’s test for equality of variances indicated variance differences between the groups). Besides the one-sample t -test against 5 (= neutral), the perceived control scores were analyzed with three ANOVAs: one ANOVA with factors Love type (love in general, infatuation, attachment) and Group (relationship, break-up), one ANOVA with factors Self/People (self, people in general) and Group, and one ANOVA with factors Intensity/Object (intensity, object) and Group. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between the seven perceived control scores and the two ERQ subscales across groups. Ratings and PANAS scores after the view conditions were analyzed with an ANOVA with factors Picture (partner, neutral) and Group. Ratings and PANAS scores following the three conditions with partner pictures were analyzed with an ANOVA with factors Regulation (view, up-regulation, down-regulation) and Group. In this analysis, only significant effects involving the factor Regulation are reported, because the main effect of Group is not relevant for the research question.

Because the LPP begins in the time range of the classic P300 [ 19 ] and can last as long as the stimulus duration [ 56 ], the ERP was quantified by mean amplitude measures in four time windows based on previous work [ 47 , 48 , 56 – 58 ]: 300–400 ms, 400–700 ms, 700–1000 ms, 1000–3000 ms. For each time window, mean amplitudes measures at Fz, Cz, and Pz were subjected to two ANOVAs. The first concerned the two view blocks and tested the factors Picture, Group, and Caudality (Fz, Cz, Pz). Only significant effects involving the factor Picture are reported, because those are relevant for the research question. The second ANOVA concerned the three blocks with partner pictures and tested the factors Regulation, Group, and Caudality. In this analysis, only significant effects involving the factor Regulation are reported, because those are relevant for the research question. When applicable, the degrees of freedom were corrected using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction. The F values, uncorrected degrees of freedom, the ε values and corrected probability values are reported. A significance level of 5% (two-sided) was selected and Fisher’s least significance difference (LSD) procedure was applied. This procedure controls type I error rate by conducting follow-up tests for significant main and interaction effects only. Those follow-up tests were paired samples t -tests testing differences between conditions across both groups (in case of significant main or interaction effects without the factor Group) or within groups (in case of significant interactions with the factor Group).

Study 2 –Results

Group characteristics.

All participants had an opposite-sex partner. The average time since the break-up was 3.0 months (range = 0.5–13.5). Ten of these break-ups were initiated by the partner, six by the participant, and four break-ups were a joint decision. See Table 4 for the other group characteristics and the statistics related to group differences. The relationship and break-up groups did not differ in how long they had known their partner for, how long ago their love feelings had started, and the duration of their relationships. The break-up groups did tend to report lower relationship quality than the relationship group. The break-up group also felt less attached and tended to feel more infatuated with their partner than the relationship group. Moreover, the break-up group tended to have experienced less positive affect during the past two weeks and had experienced more negative affect in the past two weeks and at the start of the testing session than the relationship group. Finally, the relationship and break-up groups did not differ in their habitual use of reappraisal and suppression. Thus, the two groups differed from each other on variables that can be expected to be related to whether someone is in a relationship or has experienced a break-up, but the groups did not differ on variables that should be unrelated to relationship status.

The mean score on the 17 perceived control questions was 4.5 ( SD = 1.4). A one-sample t -test showed that this was significantly lower than 5 (= neutral), t (39) = -2.2, p = .032, which suggests that participants perceive love feelings as uncontrollable. See Table 3 for the mean perceived control over the seven different aspects of love. There was a significant main effect of Love type, F (2,76) = 19.8, ε = 1.0, p < .001. Participants felt more in control of feelings of attachment than of feelings of infatuation or love in general, both p s < .001. In addition, there tended to be a main effect of Self/People, F (1,38) = 3.9, p = .056. Participants tended to feel that they were less able to control their love feelings than people in general are. Finally, there was a main effect of Intensity/Object, F (1,38) = 14.6, p < .001. Participants felt more in control of the intensity than of the object of their love feelings. In none of these analyses, the main effect of Group or interactions with Group were significant, all F s < 2.4, all p s > .13, so perceived control over different aspects of love feelings did not differ between the relationship and break-up groups.

The ERQ reappraisal score correlated positively with perceived control over individual love feelings, r (38) = .32, p = .044, and tended to correlate positively with perceived control over the intensity of love feelings, r (38) = .30, p = .056, and with perceived control over the object of love feelings, r (38) = .29, p = .075, see Fig 2 . These findings suggest that the more participants used the reappraisal strategy to regulate emotions in their daily life, the more they perceived love feelings as controllable.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g002

See Tables 1 and 2 for the regulation strategies reported. Participants mostly used distraction and reappraisal when heartbroken. Distraction was used more to feel better, while reappraisal by focusing on the negative aspects of the beloved/relationship was used more to decrease love feelings. The other strategies, such as reappraisal by thinking about the positive aspects of the situation, other ways of reappraising, avoidance, suppression (“making yourself strong (pretend) for the outside world”), eating/smoking, and expressing emotions were used least often when heartbroken. None of the participants reported the use of reappraisal by thinking about negative future scenarios. Two participants reported that they could not decrease love feelings. The use of the different strategies did not appear to differ between the relationship and break-up groups. Seeking social support was less popular in the current Dutch sample than in the US sample in Study 1.

Participants stressed the importance of communication/honesty and undertaking (new) activities with their beloved during long-term relationships. Communication/honesty was mostly used for maintaining long-term relationships. The break-up group used undertaking (new) activities with the beloved mostly to prevent love feelings from declining, while the relationship group used this strategy both to maintain their relationship and to prevent love feelings from declining. Strategies such as expressing love feelings to the beloved, spending (quality) time with the beloved, and loving unconditionally/making compromises were mentioned by some participants. The latter was used more for maintaining long-term relationships than for preventing love feelings from declining. Both reappraisal strategies (i.e., focusing on positive aspects of the beloved/relationship and thinking about positive future scenarios), trust, and spending time apart from the beloved were mentioned by some participants. Two participants specifically stated that love feelings would not decline if the relationship was good and/or that they would end the relationship if love feelings would decline. Other than the above-mentioned difference in the context of undertaking (new) activities, there were no obvious differences between the relationship and break-up groups. There were no major differences between this Dutch sample and the US sample in Study 1.

To conclude, participants reported to use several behavioral and cognitive strategies in heartbreak and long-term relationship contexts. As in Study 1, some of these strategies were the typical cognitive and behavioral emotion regulation strategies, such as reappraisal, distraction, situation selection, and suppression. As in Study 1, some strategies seemed specific for feeling better during heartbreak (i.e., emotion regulation) or for maintaining long-term relationships, while strategies such as reappraisal by focusing on the negative aspects of the beloved or the relationship and undertaking (new) activities with the beloved were used to down- and up-regulate love feelings, respectively.

See Fig 3 for the infatuation, attachment, valence, and arousal ratings at the end of each block in the regulation task.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g003

View blocks.

The infatuation ratings after the two view blocks showed main effects of Picture, F (1,38) = 27.1, p < .001, and Group, F (1,38) = 5.6, p = .023. Infatuation was higher after passive viewing of partner than neutral pictures, and higher in the relationship than the break-up group. Attachment ratings also showed main effects of Picture, F (1,38) = 23.9, p < .001, and Group, F (1,38) = 5.6, p = .023. Attachment was higher after passive viewing of partner than neutral pictures, and higher in the relationship than the break-up group. Thus, partner pictures elicited more feelings of infatuation and attachment than neutral pictures in both groups, which shows that the use of partner pictures was effective in eliciting love feelings [ 38 ].

For valence ratings, the main effects of Picture, F (1,38) = 9.9, p = .003, and Group, F (1,38) = 7.7, p = .008 were modulated by a significant Picture x Group interaction, F (1,38) = 20.7, p < .001. The relationship group felt more positive after passive viewing of partner than neutral pictures, p < .001, whereas the break-up group did not, p = .41. Arousal ratings showed a main effect of Picture, F (1,38) = 26.8, p < .001, which was modulated by a significant Picture x Group interaction, F (1,38) = 7.9, p = .008. The relationship group felt more aroused after passive viewing of partner than neutral pictures, p < .001, whereas the break-up group did not, p = .10. Thus, partner pictures elicited positive and arousing feelings in the relationship group but not in break-up group, which confirms that the two groups differed in anticipated ways.

Regulation blocks.

The infatuation ratings after the three blocks with partner pictures showed a main effect of Regulation, F (2,76) = 39.6, ε = .84, p < .001. Infatuation was lower after down-regulation than after passive viewing or up-regulation, both p s < .001. Attachment ratings also showed a main effect of Regulation, F (2,76) = 36.7, ε = .91, p < .001. Attachment was highest after up-regulation, intermediate after passive viewing, and lowest after down-regulation, all p s < .013. Valence ratings showed a main effect of Regulation, F (2,76) = 31.6, ε = .98, p < .001. Participants felt less positive after down-regulation than after passive viewing or up-regulation, both p s < .001. Arousal ratings showed no significant effects involving the factor Regulation, all p s > .26. To summarize, subjective love feelings were modulated in the expected directions by instructed love regulation in both groups. Up-regulation of love increased feelings of attachment, and down-regulation of love decreased feelings of infatuation and attachment. Finally, down-regulation of love decreased the pleasantness of feelings in both groups.

Positive and negative affect

See Fig 4 for positive and negative affect during the regulation task.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g004

Positive affect after the two view blocks showed a main effect of Picture, F (1,38) = 27.2, p < .001, which was modulated by a significant Picture x Group interaction, F (1,38) = 21.7, p < .001. The relationship group experienced more positive affect after passive viewing of partner than neutral pictures, p < .001, while the break-up group did not, p = .71. Negative affect showed main effects of Picture, F (1,38) = 9.6, p = .004, and Group, F (1,38) = 25.7, p < .001, which were modulated by a significant Picture x Group interaction, F (1,38) = 8.7, p = .005. The break-up group experienced more negative affect after passive viewing of partner than neutral pictures, p = .006, while the relationship group did not, p = .69. In short, partner pictures elicited positive affect in the relationship group, but negative affect in the break-up group, again confirming that the groups differed in expected ways.

Positive affect after the three blocks with partner pictures showed a main effect of Regulation, F (2,76) = 21.3, ε = .94, p < .001, which was modulated by a significant Regulation x Group interaction, F (2,76) = 8.4, ε = .94, p = .001. While the relationship group experienced most positive affect after passive viewing of partner pictures, intermediate positive affect after up-regulation and least positive affect after down-regulation, all p s < .034, positive affect in the break-up group was not affected by instructed love regulation, all p s > .17. Negative affect showed a main effect of Regulation, F (2,76) = 6.4, ε = .74, p = .007, which was modulated by a significant Regulation x Group interaction, F (2,76) = 5.0, ε = .74, p = .017. The relationship group experienced most negative affect after down-regulation, both p s < .008, whereas negative affect in the break-up group was not affected by instructed love regulation, all p s > .67. To summarize, love regulation decreased positive affect in the relationship group, although down-regulation decreased positive affect more than up-regulation. Down-regulation also increased negative affect in the relationship group. Regulation of love feelings did not influence affect in the break-up group.

Event-related potentials

See Fig 5 for the ERP waveforms and Fig 6 for the scalp topographies of the differences between partner and neutral pictures in the view blocks. In all four time windows, there was a significant main effect of Picture (300–400 ms: F (1,34) = 72.6, p < .001, 400–700 ms: F (1,34) = 101.6, p < .001, 700–1000 ms: F (1,34) = 112.3, p < .001 and 1000–3000 ms: F (1,34) = 51.1, p < .001), indicating that the ERP between 300–3000 ms was more positive in response to the partner than neutral pictures. The interactions involving the factors Picture and Group were not significant in any of the time windows, all F s < 1, ns , which indicated that the ERP response to the partner compared to the neutral pictures did not differ between the relationship and break-up groups. Partner and neutral pictures differ in multiple ways: partner pictures were familiar to the participants, elicited emotional feelings, displayed at least one familiar person, and may have displayed the participant him-/herself. Because all of these factors modulate the ERP [ 32 , 42 , 59 – 61 ], it is not surprising that the ERP difference between partner and neutral pictures is so extended in time and topography, and similar between the two groups. Please note that the up- and down-regulation effects of interest discussed below involve comparisons between up- and down-regulation of responses to the partner pictures only.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g005

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g006

See Fig 5 for the ERP waveforms and Fig 7 for the scalp topographies of the differences between regulation and view conditions. In the 300–400 ms time window, there were a main effect of Regulation, F (2,68) = 4.4, ε = .96, p = .018, and a Regulation x Caudality interaction, F (4,136) = 3.7, ε = .62, p = .020. The ERP was more positive for up-regulation than passive viewing at Cz and Pz, both p s < .004. In the 400–700 ms time window, there was a Regulation x Group x Caudality interaction, F (4,136) = 4.9, ε = .72, p = .004, but none of the post hoc tests were significant. In the 700–1000 ms, there were Regulation x Caudality, F (4,136) = 5.8, ε = .65, p = .002, and Regulation x Group x Caudality, F (4,136) = 5.2, ε = .65, p = .004, interactions. In the relationship group, the ERP was less positive for up- and down-regulation than passive viewing at Pz, both p s < .002. In the break-up group, none of the post hoc tests were significant. In the 1000–3000 ms time window, there was a Regulation x Group x Caudality interaction, F (4,136) = 2.7, ε = .78, p = .048. In the relationship group, the ERP was less positive for down-regulation than passive viewing at Cz and Pz, both p s < .041, and for up-regulation than passive viewing at Pz, p = .005. In the break-up group, none of the post hoc tests were significant. Inspection of the data revealed that even though the break-up group showed a less positive ERP for down-regulation at Cz (and at Pz to a lesser extent), the variation in ERP amplitudes was larger in the break-up group (down-regulation effect at Cz = -1.7 μV, SD = 4.0) than the relationship group (down-regulation effect at Cz = -1.6 μV, SD = 3.0), which explains why the effect did not reach significance in the break-up group.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g007

To explore any associations between the LPP amplitude and self-reports measures, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between regulation effects in the LPP amplitude and regulation effects in infatuation ratings, attachment ratings, valence ratings, arousal ratings, positive affect, and negative affect, across groups. Because the regulation effects were largest at electrodes Cz and/or Pz, LPP regulation effects were averaged across these two electrodes. In the 700–1000 ms time window, the up-regulation effect in the LPP amplitude was negatively correlated with the up-regulation effect in negative affect, r (34) = -.40, p = .015, see Fig 8 . This correlation was not inflated by the possibly outlying data point (i.e., up-regulation effect in negative affect = 1.5), because the correlation was even greater and more significant after exclusion of this data point, r (33) = -.44, p = .008. As can be seen in Fig 8 , the more participants showed an enhanced LPP in response to up-regulation compared to passive viewing between 700–1000 ms, the more their negative affect decreased as a result of love up-regulation. The other correlations between the up-regulation effects in the LPP amplitude in any of the time windows and the up-regulation effects in self-reports were not significant, -.31 < all r s(34) < .32, all p s > .063. None of the down-regulation effects in the LPP amplitude in any of the time windows were significantly correlated with down-regulation effects in self-reports, -.20 < all r s(34) < .24, all p s > .17.

A negative up-regulation effect in negative affect means a reduction in negative affect due to love up-regulation. A positive up-regulation effect in the LPP amplitude means that the LPP was enhanced for love up-regulation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161087.g008

To summarize, up-regulation elicited a more positive ERP than passive viewing at midline centro-parietal electrodes between 300–400 ms. In addition, up- and down-regulation elicited a less positive ERP than passive viewing mostly at midline parietal electrodes between 700–3000 ms in the relationship group. The more love up-regulation enhanced the LPP amplitude between 700–1000 ms, the greater the decrease in negative affect by love up-regulation.

Because love feelings may be more or less intense than desired, it would be helpful if people could up- and down-regulate feelings of romantic love at will. In two studies, we examined preconceptions about, strategies for, and the feasibility of love regulation.

As expected, participants had the preconception that love is somewhat uncontrollable, as indicated by their scores on the series of questions assessing the perceived controllability of love feelings. Moreover, a few participants reported that they are unable to decrease love feelings when heartbroken. Some participants even stated that love feelings should not be up-regulated to maintain long-term relationships, because declining love feelings would indicate that the relationship is not meant to be. Research, however, has shown that infatuation (i.e., passionate love) and attachment (i.e., companionate love) typically do decline over time [ 14 , 16 ], so having this opinion might limit one’s chances of having long-lasting relationships. However, the mean score on the perceived control questions approached the midpoint of the scale, indicating that participants did not entirely reject the idea of controllable love. In addition, participants perceived some aspects of love to be more controllable than other aspects. Participants perceived feelings of attachment as more controllable than feelings of infatuation and they felt more in control of the intensity of love feelings than of who they are in love with. Finally, the more participants use the reappraisal strategy to regulate emotions in their daily life, the more they perceived love feelings as controllable, which provides a hint that reappraisal may be an effective love regulation strategy. Nevertheless, the questions about perceived control over love feelings have a couple of limitations. First, the two studies were conducted in different countries, in different languages, and with relatively small samples with different gender ratios. Second, in order to not be too statistically conservative in this explorative study, we did not correct for the number of statistical tests employed. Please note that the tests we performed are not independent, which reduces the chance of type I errors [ 62 ]. In addition, we used two-sided tests even when we had an a priori directional hypothesis. This was done to not increase the chance of Type I errors and to not exclude the possibility of observing any effects that were contrary to the hypothesis, again, because of the exploratory nature of the study. Finally, to the extent that the measures in Studies 1 and 2 overlapped, we base the conclusions above only on findings that replicated in both studies. This greatly reduces the chance that our conclusions are based on country-, language-, or gender-specific effects, or on spurious findings. It would be interesting to test whether perceived control over love feelings varies between regulation directions (i.e., whether people think it is easier to down-regulate love than to up-regulate love, or vice versa) in future studies.

We asked participants what they typically do or think when they are heartbroken and when maintaining long-term relationships. Participants reported the use of prototypical emotion regulation strategies such as reappraisal, distraction, and situation selection. Only one participant mentioned using suppression. Research has shown that expression suppression does not actually alter the intensity of feelings and that it has negative effects on cognitive and social functioning [ 21 ], so it might not be an adaptive strategy for regulating love feelings.

Importantly, responses to the questions suggested that there was a dissociation in the use of certain strategies for regulating actual love feelings (i.e., love regulation) versus feeling better during heartbreak (i.e., emotion regulation) or maintaining long-term relationships. In the context of heartbreak, reappraisal was often used, especially to decrease love feelings rather than to feel better. In contrast, distraction was used during heartbreak more to feel better than to decrease love feelings. It has been shown that people prefer to use distraction over reappraisal in situations in which emotions are very intense [ 63 ], which is often the case during heartbreak. Reappraisal may be more advantageous in the long run though, because decreasing love feelings might help people to move on after a break-up.

Some participants reported avoiding beloved-related cues, such as pictures or conversations, when heartbroken, which is a situation selection strategy [ 21 ]. It has been proposed that romantic love shows parallels to drug addiction [ 2 , 64 ]. Beloved-related cues elicit love feelings [ 38 ], just like drug-related cues increase drug craving [ 65 ], so avoiding beloved-related cues may reduce ‘craving’ for the beloved in the short term. However, one type of treatment for substance dependence and other mental disorders is exposure therapy, which is based on the mechanism of extinction [ 66 ]. Because avoidance of beloved-related cues might prevent extinction of the love feelings, it may not be a suitable strategy for down-regulating love feelings in the longer term.

In the context of long-term relationships, participants often mentioned the importance of communication/honesty and of undertaking (new) activities with their beloved. While communication/honesty was used more to maintain long-term relationships than to prevent love from declining, undertaking (new) activities with the beloved was mostly used to prevent love from declining. Previous work suggests that doing exciting things with the beloved may indeed be a successful strategy for love up-regulation [ 67 , 68 ]. Correspondingly, research on long-term romantic love has shown that married couples who engaged in novel and challenging activities together reported increases in love, closeness, and relationship quality [ 69 , 70 ]. Thus, undertaking novel and exciting activities with the beloved, which is a situation selection strategy [ 21 ], may be an effective behavioral strategy for up-regulating love feelings. Surprisingly, reappraisal was mentioned only infrequently in the context of maintaining long-term relationships. Given that reappraisal is an effective and healthy emotion regulation strategy [ 21 , 22 ], it may be an adaptive strategy to prevent love feelings from declining in long-term relationships.