Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 12 February 2024

Education reform and change driven by digital technology: a bibliometric study from a global perspective

- Chengliang Wang 1 ,

- Xiaojiao Chen 1 ,

- Teng Yu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5198-7261 2 , 3 ,

- Yidan Liu 1 , 4 &

- Yuhui Jing 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 256 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

6235 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

- Science, technology and society

Amidst the global digital transformation of educational institutions, digital technology has emerged as a significant area of interest among scholars. Such technologies have played an instrumental role in enhancing learner performance and improving the effectiveness of teaching and learning. These digital technologies also ensure the sustainability and stability of education during the epidemic. Despite this, a dearth of systematic reviews exists regarding the current state of digital technology application in education. To address this gap, this study utilized the Web of Science Core Collection as a data source (specifically selecting the high-quality SSCI and SCIE) and implemented a topic search by setting keywords, yielding 1849 initial publications. Furthermore, following the PRISMA guidelines, we refined the selection to 588 high-quality articles. Using software tools such as CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Charticulator, we reviewed these 588 publications to identify core authors (such as Selwyn, Henderson, Edwards), highly productive countries/regions (England, Australia, USA), key institutions (Monash University, Australian Catholic University), and crucial journals in the field ( Education and Information Technologies , Computers & Education , British Journal of Educational Technology ). Evolutionary analysis reveals four developmental periods in the research field of digital technology education application: the embryonic period, the preliminary development period, the key exploration, and the acceleration period of change. The study highlights the dual influence of technological factors and historical context on the research topic. Technology is a key factor in enabling education to transform and upgrade, and the context of the times is an important driving force in promoting the adoption of new technologies in the education system and the transformation and upgrading of education. Additionally, the study identifies three frontier hotspots in the field: physical education, digital transformation, and professional development under the promotion of digital technology. This study presents a clear framework for digital technology application in education, which can serve as a valuable reference for researchers and educational practitioners concerned with digital technology education application in theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

A bibliometric analysis of knowledge mapping in Chinese education digitalization research from 2012 to 2022

Digital transformation and digital literacy in the context of complexity within higher education institutions: a systematic literature review

Education big data and learning analytics: a bibliometric analysis

Introduction.

Digital technology has become an essential component of modern education, facilitating the extension of temporal and spatial boundaries and enriching the pedagogical contexts (Selwyn and Facer, 2014 ). The advent of mobile communication technology has enabled learning through social media platforms (Szeto et al. 2015 ; Pires et al. 2022 ), while the advancement of augmented reality technology has disrupted traditional conceptions of learning environments and spaces (Perez-Sanagustin et al., 2014 ; Kyza and Georgiou, 2018 ). A wide range of digital technologies has enabled learning to become a norm in various settings, including the workplace (Sjöberg and Holmgren, 2021 ), home (Nazare et al. 2022 ), and online communities (Tang and Lam, 2014 ). Education is no longer limited to fixed locations and schedules, but has permeated all aspects of life, allowing learning to continue at any time and any place (Camilleri and Camilleri, 2016 ; Selwyn and Facer, 2014 ).

The advent of digital technology has led to the creation of several informal learning environments (Greenhow and Lewin, 2015 ) that exhibit divergent form, function, features, and patterns in comparison to conventional learning environments (Nygren et al. 2019 ). Consequently, the associated teaching and learning processes, as well as the strategies for the creation, dissemination, and acquisition of learning resources, have undergone a complete overhaul. The ensuing transformations have posed a myriad of novel issues, such as the optimal structuring of teaching methods by instructors and the adoption of appropriate learning strategies by students in the new digital technology environment. Consequently, an examination of the principles that underpin effective teaching and learning in this environment is a topic of significant interest to numerous scholars engaged in digital technology education research.

Over the course of the last two decades, digital technology has made significant strides in the field of education, notably in extending education time and space and creating novel educational contexts with sustainability. Despite research attempts to consolidate the application of digital technology in education, previous studies have only focused on specific aspects of digital technology, such as Pinto and Leite’s ( 2020 ) investigation into digital technology in higher education and Mustapha et al.’s ( 2021 ) examination of the role and value of digital technology in education during the pandemic. While these studies have provided valuable insights into the practical applications of digital technology in particular educational domains, they have not comprehensively explored the macro-mechanisms and internal logic of digital technology implementation in education. Additionally, these studies were conducted over a relatively brief period, making it challenging to gain a comprehensive understanding of the macro-dynamics and evolutionary process of digital technology in education. Some studies have provided an overview of digital education from an educational perspective but lack a precise understanding of technological advancement and change (Yang et al. 2022 ). Therefore, this study seeks to employ a systematic scientific approach to collate relevant research from 2000 to 2022, comprehend the internal logic and development trends of digital technology in education, and grasp the outstanding contribution of digital technology in promoting the sustainability of education in time and space. In summary, this study aims to address the following questions:

RQ1: Since the turn of the century, what is the productivity distribution of the field of digital technology education application research in terms of authorship, country/region, institutional and journal level?

RQ2: What is the development trend of research on the application of digital technology in education in the past two decades?

RQ3: What are the current frontiers of research on the application of digital technology in education?

Literature review

Although the term “digital technology” has become ubiquitous, a unified definition has yet to be agreed upon by scholars. Because the meaning of the word digital technology is closely related to the specific context. Within the educational research domain, Selwyn’s ( 2016 ) definition is widely favored by scholars (Pinto and Leite, 2020 ). Selwyn ( 2016 ) provides a comprehensive view of various concrete digital technologies and their applications in education through ten specific cases, such as immediate feedback in classes, orchestrating teaching, and community learning. Through these specific application scenarios, Selwyn ( 2016 ) argues that digital technology encompasses technologies associated with digital devices, including but not limited to tablets, smartphones, computers, and social media platforms (such as Facebook and YouTube). Furthermore, Further, the behavior of accessing the internet at any location through portable devices can be taken as an extension of the behavior of applying digital technology.

The evolving nature of digital technology has significant implications in the field of education. In the 1890s, the focus of digital technology in education was on comprehending the nuances of digital space, digital culture, and educational methodologies, with its connotations aligned more towards the idea of e-learning. The advent and subsequent widespread usage of mobile devices since the dawn of the new millennium have been instrumental in the rapid expansion of the concept of digital technology. Notably, mobile learning devices such as smartphones and tablets, along with social media platforms, have become integral components of digital technology (Conole and Alevizou, 2010 ; Batista et al. 2016 ). In recent times, the burgeoning application of AI technology in the education sector has played a vital role in enriching the digital technology lexicon (Banerjee et al. 2021 ). ChatGPT, for instance, is identified as a novel educational technology that has immense potential to revolutionize future education (Rospigliosi, 2023 ; Arif, Munaf and Ul-Haque, 2023 ).

Pinto and Leite ( 2020 ) conducted a comprehensive macroscopic survey of the use of digital technologies in the education sector and identified three distinct categories, namely technologies for assessment and feedback, mobile technologies, and Information Communication Technologies (ICT). This classification criterion is both macroscopic and highly condensed. In light of the established concept definitions of digital technology in the educational research literature, this study has adopted the characterizations of digital technology proposed by Selwyn ( 2016 ) and Pinto and Leite ( 2020 ) as crucial criteria for analysis and research inclusion. Specifically, this criterion encompasses several distinct types of digital technologies, including Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), Mobile tools, eXtended Reality (XR) Technologies, Assessment and Feedback systems, Learning Management Systems (LMS), Publish and Share tools, Collaborative systems, Social media, Interpersonal Communication tools, and Content Aggregation tools.

Methodology and materials

Research method: bibliometric.

The research on econometric properties has been present in various aspects of human production and life, yet systematic scientific theoretical guidance has been lacking, resulting in disorganization. In 1969, British scholar Pritchard ( 1969 ) proposed “bibliometrics,” which subsequently emerged as an independent discipline in scientific quantification research. Initially, Pritchard defined bibliometrics as “the application of mathematical and statistical methods to books and other media of communication,” however, the definition was not entirely rigorous. To remedy this, Hawkins ( 2001 ) expanded Pritchard’s definition to “the quantitative analysis of the bibliographic features of a body of literature.” De Bellis further clarified the objectives of bibliometrics, stating that it aims to analyze and identify patterns in literature, such as the most productive authors, institutions, countries, and journals in scientific disciplines, trends in literary production over time, and collaboration networks (De Bellis, 2009 ). According to Garfield ( 2006 ), bibliometric research enables the examination of the history and structure of a field, the flow of information within the field, the impact of journals, and the citation status of publications over a longer time scale. All of these definitions illustrate the unique role of bibliometrics as a research method for evaluating specific research fields.

This study uses CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Charticulator to analyze data and create visualizations. Each of these three tools has its own strengths and can complement each other. CiteSpace and VOSviewer use set theory and probability theory to provide various visualization views in fields such as keywords, co-occurrence, and co-authors. They are easy to use and produce visually appealing graphics (Chen, 2006 ; van Eck and Waltman, 2009 ) and are currently the two most widely used bibliometric tools in the field of visualization (Pan et al. 2018 ). In this study, VOSviewer provided the data necessary for the Performance Analysis; Charticulator was then used to redraw using the tabular data exported from VOSviewer (for creating the chord diagram of country collaboration); this was to complement the mapping process, while CiteSpace was primarily utilized to generate keyword maps and conduct burst word analysis.

Data retrieval

This study selected documents from the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) in the Web of Science Core Collection as the data source, for the following reasons:

(1) The Web of Science Core Collection, as a high-quality digital literature resource database, has been widely accepted by many researchers and is currently considered the most suitable database for bibliometric analysis (Jing et al. 2023a ). Compared to other databases, Web of Science provides more comprehensive data information (Chen et al. 2022a ), and also provides data formats suitable for analysis using VOSviewer and CiteSpace (Gaviria-Marin et al. 2019 ).

(2) The application of digital technology in the field of education is an interdisciplinary research topic, involving technical knowledge literature belonging to the natural sciences and education-related literature belonging to the social sciences. Therefore, it is necessary to select Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) as the sources of research data, ensuring the comprehensiveness of data while ensuring the reliability and persuasiveness of bibliometric research (Hwang and Tsai, 2011 ; Wang et al. 2022 ).

After establishing the source of research data, it is necessary to determine a retrieval strategy (Jing et al. 2023b ). The choice of a retrieval strategy should consider a balance between the breadth and precision of the search formula. That is to say, it should encompass all the literature pertaining to the research topic while excluding irrelevant documents as much as possible. In light of this, this study has set a retrieval strategy informed by multiple related papers (Mustapha et al. 2021 ; Luo et al. 2021 ). The research by Mustapha et al. ( 2021 ) guided us in selecting keywords (“digital” AND “technolog*”) to target digital technology, while Luo et al. ( 2021 ) informed the selection of terms (such as “instruct*,” “teach*,” and “education”) to establish links with the field of education. Then, based on the current application of digital technology in the educational domain and the scope of selection criteria, we constructed the final retrieval strategy. Following the general patterns of past research (Jing et al. 2023a , 2023b ), we conducted a specific screening using the topic search (Topics, TS) function in Web of Science. For the specific criteria used in the screening for this study, please refer to Table 1 .

Literature screening

Literature acquired through keyword searches may contain ostensibly related yet actually unrelated works. Therefore, to ensure the close relevance of literature included in the analysis to the research topic, it is often necessary to perform a manual screening process to identify the final literature to be analyzed, subsequent to completing the initial literature search.

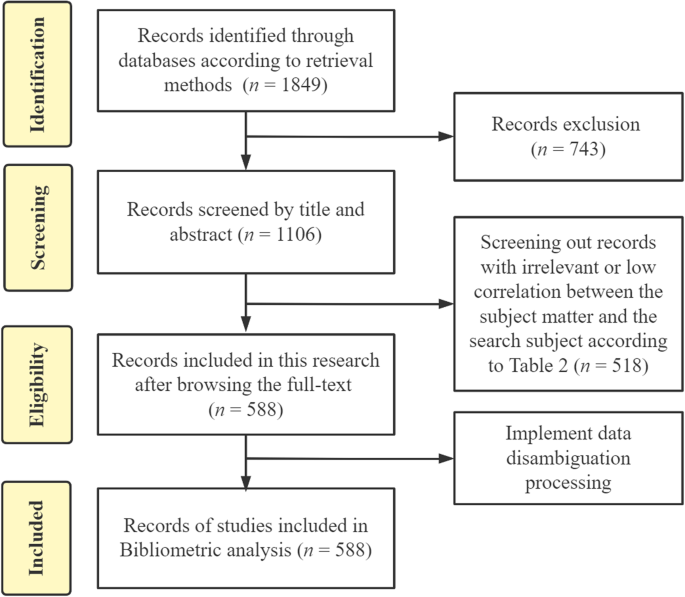

The manual screening process consists of two steps. Initially, irrelevant literature is weeded out based on the title and abstract, with two members of the research team involved in this phase. This stage lasted about one week, resulting in 1106 articles being retained. Subsequently, a comprehensive review of the full text is conducted to accurately identify the literature required for the study. To carry out the second phase of manual screening effectively and scientifically, and to minimize the potential for researcher bias, the research team established the inclusion criteria presented in Table 2 . Three members were engaged in this phase, which took approximately 2 weeks, culminating in the retention of 588 articles after meticulous screening. The entire screening process is depicted in Fig. 1 , adhering to the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al. 2021 ).

The process of obtaining and filtering the necessary literature data for research.

Data standardization

Nguyen and Hallinger ( 2020 ) pointed out that raw data extracted from scientific databases often contains multiple expressions of the same term, and not addressing these synonymous expressions could affect research results in bibliometric analysis. For instance, in the original data, the author list may include “Tsai, C. C.” and “Tsai, C.-C.”, while the keyword list may include “professional-development” and “professional development,” which often require merging. Therefore, before analyzing the selected literature, a data disambiguation process is necessary to standardize the data (Strotmann and Zhao, 2012 ; Van Eck and Waltman, 2019 ). This study adopted the data standardization process proposed by Taskin and Al ( 2019 ), mainly including the following standardization operations:

Firstly, the author and source fields in the data are corrected and standardized to differentiate authors with similar names.

Secondly, the study checks whether the journals to which the literature belongs have been renamed in the past over 20 years, so as to avoid the influence of periodical name change on the analysis results.

Finally, the keyword field is standardized by unifying parts of speech and singular/plural forms of keywords, which can help eliminate redundant entries in the knowledge graph.

Performance analysis (RQ1)

This section offers a thorough and detailed analysis of the state of research in the field of digital technology education. By utilizing descriptive statistics and visual maps, it provides a comprehensive overview of the development trends, authors, countries, institutions, and journal distribution within the field. The insights presented in this section are of great significance in advancing our understanding of the current state of research in this field and identifying areas for further investigation. The use of visual aids to display inter-country cooperation and the evolution of the field adds to the clarity and coherence of the analysis.

Time trend of the publications

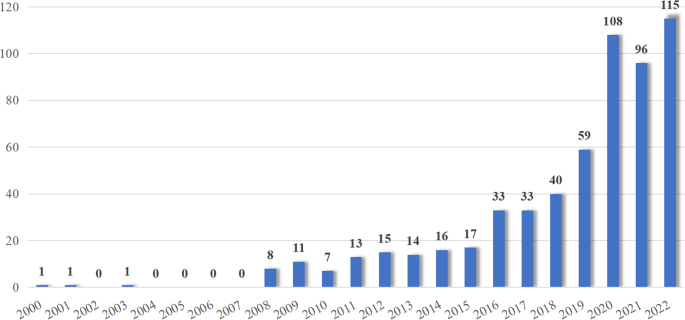

To understand a research field, it is first necessary to understand the most basic quantitative information, among which the change in the number of publications per year best reflects the development trend of a research field. Figure 2 shows the distribution of publication dates.

Time trend of the publications on application of digital technology in education.

From the Fig. 2 , it can be seen that the development of this field over the past over 20 years can be roughly divided into three stages. The first stage was from 2000 to 2007, during which the number of publications was relatively low. Due to various factors such as technological maturity, the academic community did not pay widespread attention to the role of digital technology in expanding the scope of teaching and learning. The second stage was from 2008 to 2019, during which the overall number of publications showed an upward trend, and the development of the field entered an accelerated period, attracting more and more scholars’ attention. The third stage was from 2020 to 2022, during which the number of publications stabilized at around 100. During this period, the impact of the pandemic led to a large number of scholars focusing on the role of digital technology in education during the pandemic, and research on the application of digital technology in education became a core topic in social science research.

Analysis of authors

An analysis of the author’s publication volume provides information about the representative scholars and core research strengths of a research area. Table 3 presents information on the core authors in adaptive learning research, including name, publication number, and average number of citations per article (based on the analysis and statistics from VOSviewer).

Variations in research foci among scholars abound. Within the field of digital technology education application research over the past two decades, Neil Selwyn stands as the most productive author, having published 15 papers garnering a total of 1027 citations, resulting in an average of 68.47 citations per paper. As a Professor at the Faculty of Education at Monash University, Selwyn concentrates on exploring the application of digital technology in higher education contexts (Selwyn et al. 2021 ), as well as related products in higher education such as Coursera, edX, and Udacity MOOC platforms (Bulfin et al. 2014 ). Selwyn’s contributions to the educational sociology perspective include extensive research on the impact of digital technology on education, highlighting the spatiotemporal extension of educational processes and practices through technological means as the greatest value of educational technology (Selwyn, 2012 ; Selwyn and Facer, 2014 ). In addition, he provides a blueprint for the development of future schools in 2030 based on the present impact of digital technology on education (Selwyn et al. 2019 ). The second most productive author in this field, Henderson, also offers significant contributions to the understanding of the important value of digital technology in education, specifically in the higher education setting, with a focus on the impact of the pandemic (Henderson et al. 2015 ; Cohen et al. 2022 ). In contrast, Edwards’ research interests focus on early childhood education, particularly the application of digital technology in this context (Edwards, 2013 ; Bird and Edwards, 2015 ). Additionally, on the technical level, Edwards also mainly prefers digital game technology, because it is a digital technology that children are relatively easy to accept (Edwards, 2015 ).

Analysis of countries/regions and organization

The present study aimed to ascertain the leading countries in digital technology education application research by analyzing 75 countries related to 558 works of literature. Table 4 depicts the top ten countries that have contributed significantly to this field in terms of publication count (based on the analysis and statistics from VOSviewer). Our analysis of Table 4 data shows that England emerged as the most influential country/region, with 92 published papers and 2401 citations. Australia and the United States secured the second and third ranks, respectively, with 90 papers (2187 citations) and 70 papers (1331 citations) published. Geographically, most of the countries featured in the top ten publication volumes are situated in Australia, North America, and Europe, with China being the only exception. Notably, all these countries, except China, belong to the group of developed nations, suggesting that economic strength is a prerequisite for fostering research in the digital technology education application field.

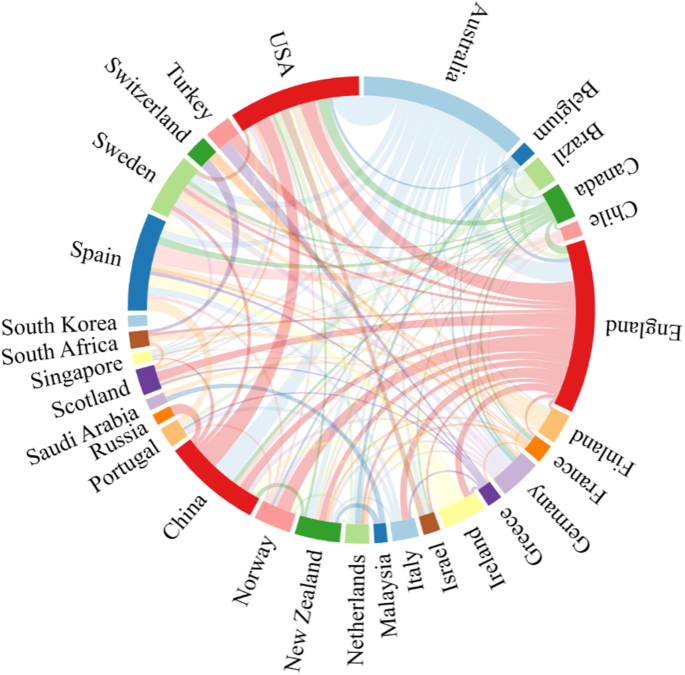

This study presents a visual representation of the publication output and cooperation relationships among different countries in the field of digital technology education application research. Specifically, a chord diagram is employed to display the top 30 countries in terms of publication output, as depicted in Fig. 3 . The chord diagram is composed of nodes and chords, where the nodes are positioned as scattered points along the circumference, and the length of each node corresponds to the publication output, with longer lengths indicating higher publication output. The chords, on the other hand, represent the cooperation relationships between any two countries, and are weighted based on the degree of closeness of the cooperation, with wider chords indicating closer cooperation. Through the analysis of the cooperation relationships, the findings suggest that the main publishing countries in this field are engaged in cooperative relationships with each other, indicating a relatively high level of international academic exchange and research internationalization.

In the diagram, nodes are scattered along the circumference of a circle, with the length of each node representing the volume of publications. The weighted arcs connecting any two points on the circle are known as chords, representing the collaborative relationship between the two, with the width of the arc indicating the closeness of the collaboration.

Further analyzing Fig. 3 , we can extract more valuable information, enabling a deeper understanding of the connections between countries in the research field of digital technology in educational applications. It is evident that certain countries, such as the United States, China, and England, display thicker connections, indicating robust collaborative relationships in terms of productivity. These thicker lines signify substantial mutual contributions and shared objectives in certain sectors or fields, highlighting the interconnectedness and global integration in these areas. By delving deeper, we can also explore potential future collaboration opportunities through the chord diagram, identifying possible partners to propel research and development in this field. In essence, the chord diagram successfully encapsulates and conveys the multi-dimensionality of global productivity and cooperation, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the intricate inter-country relationships and networks in a global context, providing valuable guidance and insights for future research and collaborations.

An in-depth examination of the publishing institutions is provided in Table 5 , showcasing the foremost 10 institutions ranked by their publication volume. Notably, Monash University and Australian Catholic University, situated in Australia, have recorded the most prolific publications within the digital technology education application realm, with 22 and 10 publications respectively. Moreover, the University of Oslo from Norway is featured among the top 10 publishing institutions, with an impressive average citation count of 64 per publication. It is worth highlighting that six institutions based in the United Kingdom were also ranked within the top 10 publishing institutions, signifying their leading position in this area of research.

Analysis of journals

Journals are the main carriers for publishing high-quality papers. Some scholars point out that the two key factors to measure the influence of journals in the specified field are the number of articles published and the number of citations. The more papers published in a magazine and the more citations, the greater its influence (Dzikowski, 2018 ). Therefore, this study utilized VOSviewer to statistically analyze the top 10 journals with the most publications in the field of digital technology in education and calculated the average citations per article (see Table 6 ).

Based on Table 6 , it is apparent that the highest number of articles in the domain of digital technology in education research were published in Education and Information Technologies (47 articles), Computers & Education (34 articles), and British Journal of Educational Technology (32 articles), indicating a higher article output compared to other journals. This underscores the fact that these three journals concentrate more on the application of digital technology in education. Furthermore, several other journals, such as Technology Pedagogy and Education and Sustainability, have published more than 15 articles in this domain. Sustainability represents the open access movement, which has notably facilitated research progress in this field, indicating that the development of open access journals in recent years has had a significant impact. Although there is still considerable disagreement among scholars on the optimal approach to achieve open access, the notion that research outcomes should be accessible to all is widely recognized (Huang et al. 2020 ). On further analysis of the research fields to which these journals belong, except for Sustainability, it is evident that they all pertain to educational technology, thus providing a qualitative definition of the research area of digital technology education from the perspective of journals.

Temporal keyword analysis: thematic evolution (RQ2)

The evolution of research themes is a dynamic process, and previous studies have attempted to present the developmental trajectory of fields by drawing keyword networks in phases (Kumar et al. 2021 ; Chen et al. 2022b ). To understand the shifts in research topics across different periods, this study follows past research and, based on the significant changes in the research field and corresponding technological advancements during the outlined periods, divides the timeline into four stages (the first stage from January 2000 to December 2005, the second stage from January 2006 to December 2011, the third stage from January 2012 to December 2017; and the fourth stage from January 2018 to December 2022). The division into these four stages was determined through a combination of bibliometric analysis and literature review, which presented a clear trajectory of the field’s development. The research analyzes the keyword networks for each time period (as there are only three articles in the first stage, it was not possible to generate an appropriate keyword co-occurrence map, hence only the keyword co-occurrence maps from the second to the fourth stages are provided), to understand the evolutionary track of the digital technology education application research field over time.

2000.1–2005.12: germination period

From January 2000 to December 2005, digital technology education application research was in its infancy. Only three studies focused on digital technology, all of which were related to computers. Due to the popularity of computers, the home became a new learning environment, highlighting the important role of digital technology in expanding the scope of learning spaces (Sutherland et al. 2000 ). In specific disciplines and contexts, digital technology was first favored in medical clinical practice, becoming an important tool for supporting the learning of clinical knowledge and practice (Tegtmeyer et al. 2001 ; Durfee et al. 2003 ).

2006.1–2011.12: initial development period

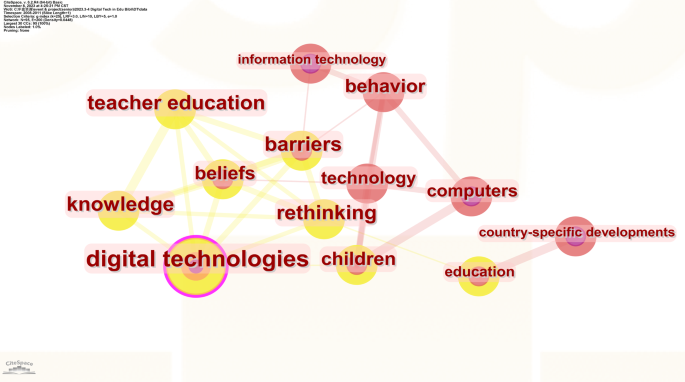

Between January 2006 and December 2011, it was the initial development period of digital technology education research. Significant growth was observed in research related to digital technology, and discussions and theoretical analyses about “digital natives” emerged. During this phase, scholars focused on the debate about “how to use digital technology reasonably” and “whether current educational models and school curriculum design need to be adjusted on a large scale” (Bennett and Maton, 2010 ; Selwyn, 2009 ; Margaryan et al. 2011 ). These theoretical and speculative arguments provided a unique perspective on the impact of cognitive digital technology on education and teaching. As can be seen from the vocabulary such as “rethinking”, “disruptive pedagogy”, and “attitude” in Fig. 4 , many scholars joined the calm reflection and analysis under the trend of digital technology (Laurillard, 2008 ; Vratulis et al. 2011 ). During this phase, technology was still undergoing dramatic changes. The development of mobile technology had already caught the attention of many scholars (Wong et al. 2011 ), but digital technology represented by computers was still very active (Selwyn et al. 2011 ). The change in technological form would inevitably lead to educational transformation. Collins and Halverson ( 2010 ) summarized the prospects and challenges of using digital technology for learning and educational practices, believing that digital technology would bring a disruptive revolution to the education field and bring about a new educational system. In addition, the term “teacher education” in Fig. 4 reflects the impact of digital technology development on teachers. The rapid development of technology has widened the generation gap between teachers and students. To ensure smooth communication between teachers and students, teachers must keep up with the trend of technological development and establish a lifelong learning concept (Donnison, 2009 ).

In the diagram, each node represents a keyword, with the size of the node indicating the frequency of occurrence of the keyword. The connections represent the co-occurrence relationships between keywords, with a higher frequency of co-occurrence resulting in tighter connections.

2012.1–2017.12: critical exploration period

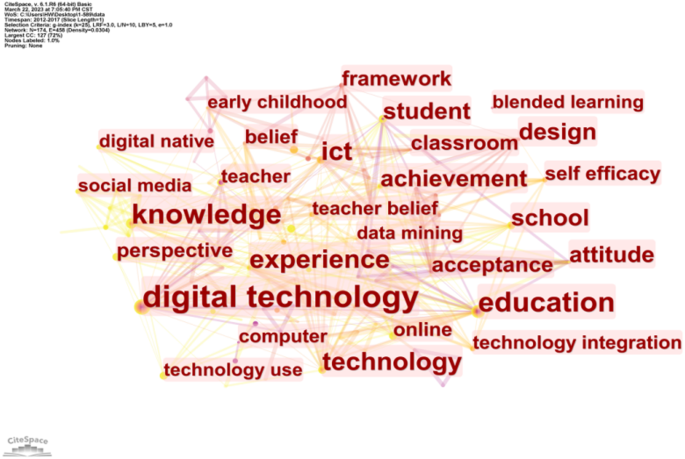

During the period spanning January 2012 to December 2017, the application of digital technology in education research underwent a significant exploration phase. As can be seen from Fig. 5 , different from the previous stage, the specific elements of specific digital technology have started to increase significantly, including the enrichment of technological contexts, the greater variety of research methods, and the diversification of learning modes. Moreover, the temporal and spatial dimensions of the learning environment were further de-emphasized, as noted in previous literature (Za et al. 2014 ). Given the rapidly accelerating pace of technological development, the education system in the digital era is in urgent need of collaborative evolution and reconstruction, as argued by Davis, Eickelmann, and Zaka ( 2013 ).

In the domain of digital technology, social media has garnered substantial scholarly attention as a promising avenue for learning, as noted by Pasquini and Evangelopoulos ( 2016 ). The implementation of social media in education presents several benefits, including the liberation of education from the restrictions of physical distance and time, as well as the erasure of conventional educational boundaries. The user-generated content (UGC) model in social media has emerged as a crucial source for knowledge creation and distribution, with the widespread adoption of mobile devices. Moreover, social networks have become an integral component of ubiquitous learning environments (Hwang et al. 2013 ). The utilization of social media allows individuals to function as both knowledge producers and recipients, which leads to a blurring of the conventional roles of learners and teachers. On mobile platforms, the roles of learners and teachers are not fixed, but instead interchangeable.

In terms of research methodology, the prevalence of empirical studies with survey designs in the field of educational technology during this period is evident from the vocabulary used, such as “achievement,” “acceptance,” “attitude,” and “ict.” in Fig. 5 . These studies aim to understand learners’ willingness to adopt and attitudes towards new technologies, and some seek to investigate the impact of digital technologies on learning outcomes through quasi-experimental designs (Domínguez et al. 2013 ). Among these empirical studies, mobile learning emerged as a hot topic, and this is not surprising. First, the advantages of mobile learning environments over traditional ones have been empirically demonstrated (Hwang et al. 2013 ). Second, learners born around the turn of the century have been heavily influenced by digital technologies and have developed their own learning styles that are more open to mobile devices as a means of learning. Consequently, analyzing mobile learning as a relatively novel mode of learning has become an important issue for scholars in the field of educational technology.

The intervention of technology has led to the emergence of several novel learning modes, with the blended learning model being the most representative one in the current phase. Blended learning, a novel concept introduced in the information age, emphasizes the integration of the benefits of traditional learning methods and online learning. This learning mode not only highlights the prominent role of teachers in guiding, inspiring, and monitoring the learning process but also underlines the importance of learners’ initiative, enthusiasm, and creativity in the learning process. Despite being an early conceptualization, blended learning’s meaning has been expanded by the widespread use of mobile technology and social media in education. The implementation of new technologies, particularly mobile devices, has resulted in the transformation of curriculum design and increased flexibility and autonomy in students’ learning processes (Trujillo Maza et al. 2016 ), rekindling scholarly attention to this learning mode. However, some scholars have raised concerns about the potential drawbacks of the blended learning model, such as its significant impact on the traditional teaching system, the lack of systematic coping strategies and relevant policies in several schools and regions (Moskal et al. 2013 ).

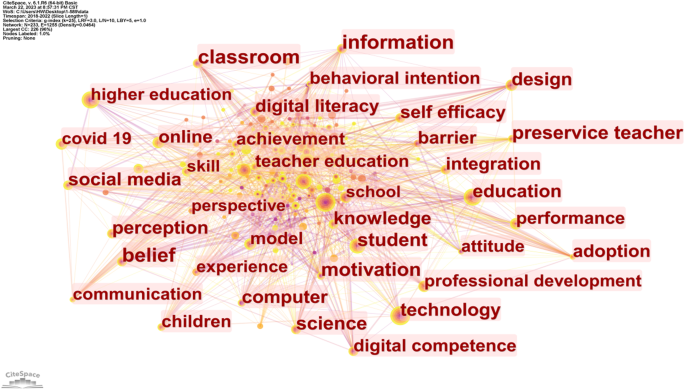

2018.1–2022.12: accelerated transformation period

The period spanning from January 2018 to December 2022 witnessed a rapid transformation in the application of digital technology in education research. The field of digital technology education research reached a peak period of publication, largely influenced by factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Yu et al. 2023 ). Research during this period was built upon the achievements, attitudes, and social media of the previous phase, and included more elements that reflect the characteristics of this research field, such as digital literacy, digital competence, and professional development, as depicted in Fig. 6 . Alongside this, scholars’ expectations for the value of digital technology have expanded, and the pursuit of improving learning efficiency and performance is no longer the sole focus. Some research now aims to cultivate learners’ motivation and enhance their self-efficacy by applying digital technology in a reasonable manner, as demonstrated by recent studies (Beardsley et al. 2021 ; Creely et al. 2021 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as a crucial backdrop for the digital technology’s role in sustaining global education, as highlighted by recent scholarly research (Zhou et al. 2022 ; Pan and Zhang, 2020 ; Mo et al. 2022 ). The online learning environment, which is supported by digital technology, has become the primary battleground for global education (Yu, 2022 ). This social context has led to various studies being conducted, with some scholars positing that the pandemic has impacted the traditional teaching order while also expanding learning possibilities in terms of patterns and forms (Alabdulaziz, 2021 ). Furthermore, the pandemic has acted as a catalyst for teacher teaching and technological innovation, and this viewpoint has been empirically substantiated (Moorhouse and Wong, 2021 ). Additionally, some scholars believe that the pandemic’s push is a crucial driving force for the digital transformation of the education system, serving as an essential mechanism for overcoming the system’s inertia (Romero et al. 2021 ).

The rapid outbreak of the pandemic posed a challenge to the large-scale implementation of digital technologies, which was influenced by a complex interplay of subjective and objective factors. Objective constraints included the lack of infrastructure in some regions to support digital technologies, while subjective obstacles included psychological resistance among certain students and teachers (Moorhouse, 2021 ). These factors greatly impacted the progress of online learning during the pandemic. Additionally, Timotheou et al. ( 2023 ) conducted a comprehensive systematic review of existing research on digital technology use during the pandemic, highlighting the critical role played by various factors such as learners’ and teachers’ digital skills, teachers’ personal attributes and professional development, school leadership and management, and administration in facilitating the digitalization and transformation of schools.

The current stage of research is characterized by the pivotal term “digital literacy,” denoting a growing interest in learners’ attitudes and adoption of emerging technologies. Initially, the term “literacy” was restricted to fundamental abilities and knowledge associated with books and print materials (McMillan, 1996 ). However, with the swift advancement of computers and digital technology, there have been various attempts to broaden the scope of literacy beyond its traditional meaning, including game literacy (Buckingham and Burn, 2007 ), information literacy (Eisenberg, 2008 ), and media literacy (Turin and Friesem, 2020 ). Similarly, digital literacy has emerged as a crucial concept, and Gilster and Glister ( 1997 ) were the first to introduce this concept, referring to the proficiency in utilizing technology and processing digital information in academic, professional, and daily life settings. In practical educational settings, learners who possess higher digital literacy often exhibit an aptitude for quickly mastering digital devices and applying them intelligently to education and teaching (Yu, 2022 ).

The utilization of digital technology in education has undergone significant changes over the past two decades, and has been a crucial driver of educational reform with each new technological revolution. The impact of these changes on the underlying logic of digital technology education applications has been noticeable. From computer technology to more recent developments such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and artificial intelligence (AI), the acceleration in digital technology development has been ongoing. Educational reforms spurred by digital technology development continue to be dynamic, as each new digital innovation presents new possibilities and models for teaching practice. This is especially relevant in the post-pandemic era, where the importance of technological progress in supporting teaching cannot be overstated (Mughal et al. 2022 ). Existing digital technologies have already greatly expanded the dimensions of education in both time and space, while future digital technologies aim to expand learners’ perceptions. Researchers have highlighted the potential of integrated technology and immersive technology in the development of the educational metaverse, which is highly anticipated to create a new dimension for the teaching and learning environment, foster a new value system for the discipline of educational technology, and more effectively and efficiently achieve the grand educational blueprint of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Zhang et al. 2022 ; Li and Yu, 2023 ).

Hotspot evolution analysis (RQ3)

The examination of keyword evolution reveals a consistent trend in the advancement of digital technology education application research. The emergence and transformation of keywords serve as indicators of the varying research interests in this field. Thus, the utilization of the burst detection function available in CiteSpace allowed for the identification of the top 10 burst words that exhibited a high level of burst strength. This outcome is illustrated in Table 7 .

According to the results presented in Table 7 , the explosive terminology within the realm of digital technology education research has exhibited a concentration mainly between the years 2018 and 2022. Prior to this time frame, the emerging keywords were limited to “information technology” and “computer”. Notably, among them, computer, as an emergent keyword, has always had a high explosive intensity from 2008 to 2018, which reflects the important position of computer in digital technology and is the main carrier of many digital technologies such as Learning Management Systems (LMS) and Assessment and Feedback systems (Barlovits et al. 2022 ).

Since 2018, an increasing number of research studies have focused on evaluating the capabilities of learners to accept, apply, and comprehend digital technologies. As indicated by the use of terms such as “digital literacy” and “digital skill,” the assessment of learners’ digital literacy has become a critical task. Scholarly efforts have been directed towards the development of literacy assessment tools and the implementation of empirical assessments. Furthermore, enhancing the digital literacy of both learners and educators has garnered significant attention. (Nagle, 2018 ; Yu, 2022 ). Simultaneously, given the widespread use of various digital technologies in different formal and informal learning settings, promoting learners’ digital skills has become a crucial objective for contemporary schools (Nygren et al. 2019 ; Forde and OBrien, 2022 ).

Since 2020, the field of applied research on digital technology education has witnessed the emergence of three new hotspots, all of which have been affected to some extent by the pandemic. Firstly, digital technology has been widely applied in physical education, which is one of the subjects that has been severely affected by the pandemic (Parris et al. 2022 ; Jiang and Ning, 2022 ). Secondly, digital transformation has become an important measure for most schools, especially higher education institutions, to cope with the impact of the pandemic globally (García-Morales et al. 2021 ). Although the concept of digital transformation was proposed earlier, the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly accelerated this transformation process. Educational institutions must carefully redesign their educational products to face this new situation, providing timely digital learning methods, environments, tools, and support systems that have far-reaching impacts on modern society (Krishnamurthy, 2020 ; Salas-Pilco et al. 2022 ). Moreover, the professional development of teachers has become a key mission of educational institutions in the post-pandemic era. Teachers need to have a certain level of digital literacy and be familiar with the tools and online teaching resources used in online teaching, which has become a research hotspot today. Organizing digital skills training for teachers to cope with the application of emerging technologies in education is an important issue for teacher professional development and lifelong learning (Garzón-Artacho et al. 2021 ). As the main organizers and practitioners of emergency remote teaching (ERT) during the pandemic, teachers must put cognitive effort into their professional development to ensure effective implementation of ERT (Romero-Hall and Jaramillo Cherrez, 2022 ).

The burst word “digital transformation” reveals that we are in the midst of an ongoing digital technology revolution. With the emergence of innovative digital technologies such as ChatGPT and Microsoft 365 Copilot, technology trends will continue to evolve, albeit unpredictably. While the impact of these advancements on school education remains uncertain, it is anticipated that the widespread integration of technology will significantly affect the current education system. Rejecting emerging technologies without careful consideration is unwise. Like any revolution, the technological revolution in the education field has both positive and negative aspects. Detractors argue that digital technology disrupts learning and memory (Baron, 2021 ) or causes learners to become addicted and distracted from learning (Selwyn and Aagaard, 2020 ). On the other hand, the prudent use of digital technology in education offers a glimpse of a golden age of open learning. Educational leaders and practitioners have the opportunity to leverage cutting-edge digital technologies to address current educational challenges and develop a rational path for the sustainable and healthy growth of education.

Discussion on performance analysis (RQ1)

The field of digital technology education application research has experienced substantial growth since the turn of the century, a phenomenon that is quantifiably apparent through an analysis of authorship, country/region contributions, and institutional engagement. This expansion reflects the increased integration of digital technologies in educational settings and the heightened scholarly interest in understanding and optimizing their use.

Discussion on authorship productivity in digital technology education research

The authorship distribution within digital technology education research is indicative of the field’s intellectual structure and depth. A primary figure in this domain is Neil Selwyn, whose substantial citation rate underscores the profound impact of his work. His focus on the implications of digital technology in higher education and educational sociology has proven to be seminal. Selwyn’s research trajectory, especially the exploration of spatiotemporal extensions of education through technology, provides valuable insights into the multifaceted role of digital tools in learning processes (Selwyn et al. 2019 ).

Other notable contributors, like Henderson and Edwards, present diversified research interests, such as the impact of digital technologies during the pandemic and their application in early childhood education, respectively. Their varied focuses highlight the breadth of digital technology education research, encompassing pedagogical innovation, technological adaptation, and policy development.

Discussion on country/region-level productivity and collaboration

At the country/region level, the United Kingdom, specifically England, emerges as a leading contributor with 92 published papers and a significant citation count. This is closely followed by Australia and the United States, indicating a strong English-speaking research axis. Such geographical concentration of scholarly output often correlates with investment in research and development, technological infrastructure, and the prevalence of higher education institutions engaging in cutting-edge research.

China’s notable inclusion as the only non-Western country among the top contributors to the field suggests a growing research capacity and interest in digital technology in education. However, the lower average citation per paper for China could reflect emerging engagement or different research focuses that may not yet have achieved the same international recognition as Western counterparts.

The chord diagram analysis furthers this understanding, revealing dense interconnections between countries like the United States, China, and England, which indicates robust collaborations. Such collaborations are fundamental in addressing global educational challenges and shaping international research agendas.

Discussion on institutional-level contributions to digital technology education

Institutional productivity in digital technology education research reveals a constellation of universities driving the field forward. Monash University and the Australian Catholic University have the highest publication output, signaling Australia’s significant role in advancing digital education research. The University of Oslo’s remarkable average citation count per publication indicates influential research contributions, potentially reflecting high-quality studies that resonate with the broader academic community.

The strong showing of UK institutions, including the University of London, The Open University, and the University of Cambridge, reinforces the UK’s prominence in this research field. Such institutions are often at the forefront of pedagogical innovation, benefiting from established research cultures and funding mechanisms that support sustained inquiry into digital education.

Discussion on journal publication analysis

An examination of journal outputs offers a lens into the communicative channels of the field’s knowledge base. Journals such as Education and Information Technologies , Computers & Education , and the British Journal of Educational Technology not only serve as the primary disseminators of research findings but also as indicators of research quality and relevance. The impact factor (IF) serves as a proxy for the quality and influence of these journals within the academic community.

The high citation counts for articles published in Computers & Education suggest that research disseminated through this medium has a wide-reaching impact and is of particular interest to the field. This is further evidenced by its significant IF of 11.182, indicating that the journal is a pivotal platform for seminal work in the application of digital technology in education.

The authorship, regional, and institutional productivity in the field of digital technology education application research collectively narrate the evolution of this domain since the turn of the century. The prominence of certain authors and countries underscores the importance of socioeconomic factors and existing academic infrastructure in fostering research productivity. Meanwhile, the centrality of specific journals as outlets for high-impact research emphasizes the role of academic publishing in shaping the research landscape.

As the field continues to grow, future research may benefit from leveraging the collaborative networks that have been elucidated through this analysis, perhaps focusing on underrepresented regions to broaden the scope and diversity of research. Furthermore, the stabilization of publication numbers in recent years invites a deeper exploration into potential plateaus in research trends or saturation in certain sub-fields, signaling an opportunity for novel inquiries and methodological innovations.

Discussion on the evolutionary trends (RQ2)

The evolution of the research field concerning the application of digital technology in education over the past two decades is a story of convergence, diversification, and transformation, shaped by rapid technological advancements and shifting educational paradigms.

At the turn of the century, the inception of digital technology in education was largely exploratory, with a focus on how emerging computer technologies could be harnessed to enhance traditional learning environments. Research from this early period was primarily descriptive, reflecting on the potential and challenges of incorporating digital tools into the educational setting. This phase was critical in establishing the fundamental discourse that would guide subsequent research, as it set the stage for understanding the scope and impact of digital technology in learning spaces (Wang et al. 2023 ).

As the first decade progressed, the narrative expanded to encompass the pedagogical implications of digital technologies. This was a period of conceptual debates, where terms like “digital natives” and “disruptive pedagogy” entered the academic lexicon, underscoring the growing acknowledgment of digital technology as a transformative force within education (Bennett and Maton, 2010 ). During this time, the research began to reflect a more nuanced understanding of the integration of technology, considering not only its potential to change where and how learning occurred but also its implications for educational equity and access.

In the second decade, with the maturation of internet connectivity and mobile technology, the focus of research shifted from theoretical speculations to empirical investigations. The proliferation of digital devices and the ubiquity of social media influenced how learners interacted with information and each other, prompting a surge in studies that sought to measure the impact of these tools on learning outcomes. The digital divide and issues related to digital literacy became central concerns, as scholars explored the varying capacities of students and educators to engage with technology effectively.

Throughout this period, there was an increasing emphasis on the individualization of learning experiences, facilitated by adaptive technologies that could cater to the unique needs and pacing of learners (Jing et al. 2023a ). This individualization was coupled with a growing recognition of the importance of collaborative learning, both online and offline, and the role of digital tools in supporting these processes. Blended learning models, which combined face-to-face instruction with online resources, emerged as a significant trend, advocating for a balance between traditional pedagogies and innovative digital strategies.

The later years, particularly marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, accelerated the necessity for digital technology in education, transforming it from a supplementary tool to an essential platform for delivering education globally (Mo et al. 2022 ; Mustapha et al. 2021 ). This era brought about an unprecedented focus on online learning environments, distance education, and virtual classrooms. Research became more granular, examining not just the pedagogical effectiveness of digital tools, but also their role in maintaining continuity of education during crises, their impact on teacher and student well-being, and their implications for the future of educational policy and infrastructure.

Across these two decades, the research field has seen a shift from examining digital technology as an external addition to the educational process, to viewing it as an integral component of curriculum design, instructional strategies, and even assessment methods. The emergent themes have broadened from a narrow focus on specific tools or platforms to include wider considerations such as data privacy, ethical use of technology, and the environmental impact of digital tools.

Moreover, the field has moved from considering the application of digital technology in education as a primarily cognitive endeavor to recognizing its role in facilitating socio-emotional learning, digital citizenship, and global competencies. Researchers have increasingly turned their attention to the ways in which technology can support collaborative skills, cultural understanding, and ethical reasoning within diverse student populations.

In summary, the past over twenty years in the research field of digital technology applications in education have been characterized by a progression from foundational inquiries to complex analyses of digital integration. This evolution has mirrored the trajectory of technology itself, from a facilitative tool to a pervasive ecosystem defining contemporary educational experiences. As we look to the future, the field is poised to delve into the implications of emerging technologies like AI, AR, and VR, and their potential to redefine the educational landscape even further. This ongoing metamorphosis suggests that the application of digital technology in education will continue to be a rich area of inquiry, demanding continual adaptation and forward-thinking from educators and researchers alike.

Discussion on the study of research hotspots (RQ3)

The analysis of keyword evolution in digital technology education application research elucidates the current frontiers in the field, reflecting a trajectory that is in tandem with the rapidly advancing digital age. This landscape is sculpted by emergent technological innovations and shaped by the demands of an increasingly digital society.

Interdisciplinary integration and pedagogical transformation

One of the frontiers identified from recent keyword bursts includes the integration of digital technology into diverse educational contexts, particularly noted with the keyword “physical education.” The digitalization of disciplines traditionally characterized by physical presence illustrates the pervasive reach of technology and signifies a push towards interdisciplinary integration where technology is not only a facilitator but also a transformative agent. This integration challenges educators to reconceptualize curriculum delivery to accommodate digital tools that can enhance or simulate the physical aspects of learning.

Digital literacy and skills acquisition

Another pivotal frontier is the focus on “digital literacy” and “digital skill”, which has intensified in recent years. This suggests a shift from mere access to technology towards a comprehensive understanding and utilization of digital tools. In this realm, the emphasis is not only on the ability to use technology but also on critical thinking, problem-solving, and the ethical use of digital resources (Yu, 2022 ). The acquisition of digital literacy is no longer an additive skill but a fundamental aspect of modern education, essential for navigating and contributing to the digital world.

Educational digital transformation

The keyword “digital transformation” marks a significant research frontier, emphasizing the systemic changes that education institutions must undergo to align with the digital era (Romero et al. 2021 ). This transformation includes the redesigning of learning environments, pedagogical strategies, and assessment methods to harness digital technology’s full potential. Research in this area explores the complexity of institutional change, addressing the infrastructural, cultural, and policy adjustments needed for a seamless digital transition.

Engagement and participation

Further exploration into “engagement” and “participation” underscores the importance of student-centered learning environments that are mediated by technology. The current frontiers examine how digital platforms can foster collaboration, inclusivity, and active learning, potentially leading to more meaningful and personalized educational experiences. Here, the use of technology seeks to support the emotional and cognitive aspects of learning, moving beyond the transactional view of education to one that is relational and interactive.

Professional development and teacher readiness

As the field evolves, “professional development” emerges as a crucial area, particularly in light of the pandemic which necessitated emergency remote teaching. The need for teacher readiness in a digital age is a pressing frontier, with research focusing on the competencies required for educators to effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices. This includes familiarity with digital tools, pedagogical innovation, and an ongoing commitment to personal and professional growth in the digital domain.

Pandemic as a catalyst

The recent pandemic has acted as a catalyst for accelerated research and application in this field, particularly in the domains of “digital transformation,” “professional development,” and “physical education.” This period has been a litmus test for the resilience and adaptability of educational systems to continue their operations in an emergency. Research has thus been directed at understanding how digital technologies can support not only continuity but also enhance the quality and reach of education in such contexts.

Ethical and societal considerations

The frontier of digital technology in education is also expanding to consider broader ethical and societal implications. This includes issues of digital equity, data privacy, and the sociocultural impact of technology on learning communities. The research explores how educational technology can be leveraged to address inequities and create more equitable learning opportunities for all students, regardless of their socioeconomic background.

Innovation and emerging technologies

Looking forward, the frontiers are set to be influenced by ongoing and future technological innovations, such as artificial intelligence (AI) (Wu and Yu, 2023 ; Chen et al. 2022a ). The exploration into how these technologies can be integrated into educational practices to create immersive and adaptive learning experiences represents a bold new chapter for the field.

In conclusion, the current frontiers of research on the application of digital technology in education are multifaceted and dynamic. They reflect an overarching movement towards deeper integration of technology in educational systems and pedagogical practices, where the goals are not only to facilitate learning but to redefine it. As these frontiers continue to expand and evolve, they will shape the educational landscape, requiring a concerted effort from researchers, educators, policymakers, and technologists to navigate the challenges and harness the opportunities presented by the digital revolution in education.

Conclusions and future research

Conclusions.

The utilization of digital technology in education is a research area that cuts across multiple technical and educational domains and continues to experience dynamic growth due to the continuous progress of technology. In this study, a systematic review of this field was conducted through bibliometric techniques to examine its development trajectory. The primary focus of the review was to investigate the leading contributors, productive national institutions, significant publications, and evolving development patterns. The study’s quantitative analysis resulted in several key conclusions that shed light on this research field’s current state and future prospects.

(1) The research field of digital technology education applications has entered a stage of rapid development, particularly in recent years due to the impact of the pandemic, resulting in a peak of publications. Within this field, several key authors (Selwyn, Henderson, Edwards, etc.) and countries/regions (England, Australia, USA, etc.) have emerged, who have made significant contributions. International exchanges in this field have become frequent, with a high degree of internationalization in academic research. Higher education institutions in the UK and Australia are the core productive forces in this field at the institutional level.

(2) Education and Information Technologies , Computers & Education , and the British Journal of Educational Technology are notable journals that publish research related to digital technology education applications. These journals are affiliated with the research field of educational technology and provide effective communication platforms for sharing digital technology education applications.

(3) Over the past two decades, research on digital technology education applications has progressed from its early stages of budding, initial development, and critical exploration to accelerated transformation, and it is currently approaching maturity. Technological progress and changes in the times have been key driving forces for educational transformation and innovation, and both have played important roles in promoting the continuous development of education.

(4) Influenced by the pandemic, three emerging frontiers have emerged in current research on digital technology education applications, which are physical education, digital transformation, and professional development under the promotion of digital technology. These frontier research hotspots reflect the core issues that the education system faces when encountering new technologies. The evolution of research hotspots shows that technology breakthroughs in education’s original boundaries of time and space create new challenges. The continuous self-renewal of education is achieved by solving one hotspot problem after another.

The present study offers significant practical implications for scholars and practitioners in the field of digital technology education applications. Firstly, it presents a well-defined framework of the existing research in this area, serving as a comprehensive guide for new entrants to the field and shedding light on the developmental trajectory of this research domain. Secondly, the study identifies several contemporary research hotspots, thus offering a valuable decision-making resource for scholars aiming to explore potential research directions. Thirdly, the study undertakes an exhaustive analysis of published literature to identify core journals in the field of digital technology education applications, with Sustainability being identified as a promising open access journal that publishes extensively on this topic. This finding can potentially facilitate scholars in selecting appropriate journals for their research outputs.

Limitation and future research

Influenced by some objective factors, this study also has some limitations. First of all, the bibliometrics analysis software has high standards for data. In order to ensure the quality and integrity of the collected data, the research only selects the periodical papers in SCIE and SSCI indexes, which are the core collection of Web of Science database, and excludes other databases, conference papers, editorials and other publications, which may ignore some scientific research and original opinions in the field of digital technology education and application research. In addition, although this study used professional software to carry out bibliometric analysis and obtained more objective quantitative data, the analysis and interpretation of data will inevitably have a certain subjective color, and the influence of subjectivity on data analysis cannot be completely avoided. As such, future research endeavors will broaden the scope of literature screening and proactively engage scholars in the field to gain objective and state-of-the-art insights, while minimizing the adverse impact of personal subjectivity on research analysis.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/F9QMHY

Alabdulaziz MS (2021) COVID-19 and the use of digital technology in mathematics education. Educ Inf Technol 26(6):7609–7633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10602-3

Arif TB, Munaf U, Ul-Haque I (2023) The future of medical education and research: is ChatGPT a blessing or blight in disguise? Med Educ Online 28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2023.2181052

Banerjee M, Chiew D, Patel KT, Johns I, Chappell D, Linton N, Cole GD, Francis DP, Szram J, Ross J, Zaman S (2021) The impact of artificial intelligence on clinical education: perceptions of postgraduate trainee doctors in London (UK) and recommendations for trainers. BMC Med Educ 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02870-x

Barlovits S, Caldeira A, Fesakis G, Jablonski S, Koutsomanoli Filippaki D, Lázaro C, Ludwig M, Mammana MF, Moura A, Oehler DXK, Recio T, Taranto E, Volika S(2022) Adaptive, synchronous, and mobile online education: developing the ASYMPTOTE learning environment. Mathematics 10:1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10101628

Article Google Scholar

Baron NS(2021) Know what? How digital technologies undermine learning and remembering J Pragmat 175:27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.01.011

Batista J, Morais NS, Ramos F (2016) Researching the use of communication technologies in higher education institutions in Portugal. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0571-6.ch057

Beardsley M, Albó L, Aragón P, Hernández-Leo D (2021) Emergency education effects on teacher abilities and motivation to use digital technologies. Br J Educ Technol 52. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13101

Bennett S, Maton K(2010) Beyond the “digital natives” debate: towards a more nuanced understanding of students’ technology experiences J Comput Assist Learn 26:321–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00360.x

Buckingham D, Burn A (2007) Game literacy in theory and practice 16:323–349

Google Scholar

Bulfin S, Pangrazio L, Selwyn N (2014) Making “MOOCs”: the construction of a new digital higher education within news media discourse. In: The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 15. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i5.1856

Camilleri MA, Camilleri AC(2016) Digital learning resources and ubiquitous technologies in education Technol Knowl Learn 22:65–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-016-9287-7

Chen C(2006) CiteSpace II: detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 57:359–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317

Chen J, Dai J, Zhu K, Xu L(2022) Effects of extended reality on language learning: a meta-analysis Front Psychol 13:1016519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016519

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chen J, Wang CL, Tang Y (2022b) Knowledge mapping of volunteer motivation: a bibliometric analysis and cross-cultural comparative study. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883150

Cohen A, Soffer T, Henderson M(2022) Students’ use of technology and their perceptions of its usefulness in higher education: International comparison J Comput Assist Learn 38(5):1321–1331. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12678

Collins A, Halverson R(2010) The second educational revolution: rethinking education in the age of technology J Comput Assist Learn 26:18–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00339.x

Conole G, Alevizou P (2010) A literature review of the use of Web 2.0 tools in higher education. Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, UK: the Open University, retrieved 17 February

Creely E, Henriksen D, Crawford R, Henderson M(2021) Exploring creative risk-taking and productive failure in classroom practice. A case study of the perceived self-efficacy and agency of teachers at one school Think Ski Creat 42:100951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100951

Davis N, Eickelmann B, Zaka P(2013) Restructuring of educational systems in the digital age from a co-evolutionary perspective J Comput Assist Learn 29:438–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12032

De Belli N (2009) Bibliometrics and citation analysis: from the science citation index to cybermetrics, Scarecrow Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12032

Domínguez A, Saenz-de-Navarrete J, de-Marcos L, Fernández-Sanz L, Pagés C, Martínez-Herráiz JJ(2013) Gamifying learning experiences: practical implications and outcomes Comput Educ 63:380–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.020

Donnison S (2009) Discourses in conflict: the relationship between Gen Y pre-service teachers, digital technologies and lifelong learning. Australasian J Educ Technol 25. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1138

Durfee SM, Jain S, Shaffer K (2003) Incorporating electronic media into medical student education. Acad Radiol 10:205–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80046-6

Dzikowski P(2018) A bibliometric analysis of born global firms J Bus Res 85:281–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.054

van Eck NJ, Waltman L(2009) Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping Scientometrics 84:523–538 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Edwards S(2013) Digital play in the early years: a contextual response to the problem of integrating technologies and play-based pedagogies in the early childhood curriculum Eur Early Child Educ Res J 21:199–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293x.2013.789190

Edwards S(2015) New concepts of play and the problem of technology, digital media and popular-culture integration with play-based learning in early childhood education Technol Pedagogy Educ 25:513–532 https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939x.2015.1108929

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Eisenberg MB(2008) Information literacy: essential skills for the information age DESIDOC J Libr Inf Technol 28:39–47. https://doi.org/10.14429/djlit.28.2.166

Forde C, OBrien A (2022) A literature review of barriers and opportunities presented by digitally enhanced practical skill teaching and learning in health science education. Med Educ Online 27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2022.2068210

García-Morales VJ, Garrido-Moreno A, Martín-Rojas R (2021) The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Front Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.616059

Garfield E(2006) The history and meaning of the journal impact factor JAMA 295:90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.1.90

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Garzón-Artacho E, Sola-Martínez T, Romero-Rodríguez JM, Gómez-García G(2021) Teachers’ perceptions of digital competence at the lifelong learning stage Heliyon 7:e07513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07513

Gaviria-Marin M, Merigó JM, Baier-Fuentes H(2019) Knowledge management: a global examination based on bibliometric analysis Technol Forecast Soc Change 140:194–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.006

Gilster P, Glister P (1997) Digital literacy. Wiley Computer Pub, New York

Greenhow C, Lewin C(2015) Social media and education: reconceptualizing the boundaries of formal and informal learning Learn Media Technol 41:6–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1064954

Hawkins DT(2001) Bibliometrics of electronic journals in information science Infor Res 7(1):7–1. http://informationr.net/ir/7-1/paper120.html

Henderson M, Selwyn N, Finger G, Aston R(2015) Students’ everyday engagement with digital technology in university: exploring patterns of use and “usefulness J High Educ Policy Manag 37:308–319 https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080x.2015.1034424

Huang CK, Neylon C, Hosking R, Montgomery L, Wilson KS, Ozaygen A, Brookes-Kenworthy C (2020) Evaluating the impact of open access policies on research institutions. eLife 9. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.57067

Hwang GJ, Tsai CC(2011) Research trends in mobile and ubiquitous learning: a review of publications in selected journals from 2001 to 2010 Br J Educ Technol 42:E65–E70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01183.x

Hwang GJ, Wu PH, Zhuang YY, Huang YM(2013) Effects of the inquiry-based mobile learning model on the cognitive load and learning achievement of students Interact Learn Environ 21:338–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2011.575789

Jiang S, Ning CF (2022) Interactive communication in the process of physical education: are social media contributing to the improvement of physical training performance. Universal Access Inf Soc, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-022-00911-w

Jing Y, Zhao L, Zhu KK, Wang H, Wang CL, Xia Q(2023) Research landscape of adaptive learning in education: a bibliometric study on research publications from 2000 to 2022 Sustainability 15:3115–3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043115