- Mind and Health

Stress Matters

While some patients – about 10 to 20 percent – exhibit extreme anxiety and depression indicative of a major psychiatric disorder, most people have what is best termed “everyday psychological distress .” This more common type of psychological distress has a major impact on daily physical and social functions. It even produces disabilities equivalent to diabetes, hypertension or arthritis.

The majority of Americans report unhealthy stress levels. And 1 in 5 people quantify their stress level as “extremely high.” What’s perhaps even more worrisome is that only 37 percent of Americans feel they’re able to adequately manage their stress. Most commonly, stress originates from work, financial pressures, family responsibilities, relationships and personal health concerns.

Ironically, stress negatively impacts the aspects of people’s lives that cause it in the first place. For instance, 70 percent of individuals who are stressed experience physical symptoms, lower productivity at work, and disruptions in their family and social lives.

Furthermore, adults with high stress levels are less likely to eat healthily, engage in physical activity, get enough sleep or moderate their alcohol consumption. These behaviors – often caused by stress – lead to additional health problems like depression, cardiovascular disease and even a greater susceptibility to colds. Stress can even affect our genes and speed up the aging process. Women with high stress levels experience a shortening in portions of their DNA with results equivalent to nearly a decade of accelerated aging compared to women with less stress.

We know stress-related symptoms take a toll on individual health. But studies also show the dire impact stress has on our nation’s work productivity and overall health care system. A third of U.S. workers report feeling extremely stressed at work . And this job-related stress is costing American industry an estimated $300 billion a year in absenteeism, turnover, diminished productivity and on-the-job accidents. Meanwhile, health care expenditures are nearly 50 percent greater for workers who report high levels of stress.

Early childhood stress seems to exert an exceptionally powerful influence throughout life. A long-term study of 17,000 people, found that adverse childhood experiences are very common:

- 11% experienced emotional abuse

- 28% experienced physical abuse

- 21% experienced sexual abuse

- 15% experienced emotional neglect

- 10% experienced physical neglect

- 13% witnessed their mothers being treated violently

- 27% grew up with someone in the household using alcohol and/or drugs

- 19% grew up with a mentally-ill person in the household

- 23% lost a parent due to separation or divorce

- 5% grew up with a household member in jail or prison

The study also found that these children have profound, lasting, and damaging effects throughout life. The more categories of trauma experienced in childhood, the greater the likelihood of experiencing:

- alcoholism and alcohol abuse

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- ischemic heart disease (IHD)

- liver disease

- suicide attempts

- poor health-related quality of life

- illicit drug use

- risk for intimate partner violence

- multiple sexual partners

- sexually transmitted diseases (STDs)

- unintended pregnancies

- fetal death

The total lifetime economic burden resulting from new cases of fatal and nonfatal child maltreatment in the United States is approximately $124 billion in 2010 dollars. This economic burden rivals the cost of other high profile public health problems, such as stroke and type 2 diabetes.

Fortunately, there is evidence that some of this child maltreatment and its health, social and economic consequences can be prevented.

The Other Side Of Stress: Why Positive Moods and Mindset Matters

Some stress can actually be positive , particularly when it motivates necessary lifestyle changes and builds resilience. Interestingly, the effect of stress on health and well-being, seems to be moderated by your view or “ mindset ” regarding the impact of stress. People who view stress as potentially helpful, something to be used and embraced (“stress-is-enhancing mindset”), fare much better than those who see stress as something that makes you sick and to be avoided and reduced (stress-is-debilitating mindset”). The good news is that these stress mindsets can be altered. In one experiment, when “stress-is-enhancing” videos were shown to people, their symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as work performance improved.

In a study of over 28,000 people those who reported both a lot of stress and the perception that stress affects their health had a 43% increased risk of death. In fact, believing that stress is harmful to health may have caused over 20,000 premature deaths per year, making this the 15th leading cause of death in America. Seeing the upside of stress is not about deciding whether stress is either all good or all bad. It’s about how choosing to see the good in stress can help you meet the challenges in your life.

Studies show that positive and negative moods influence physical health and longevity independently. Mounting evidence demonstrates that happiness, pleasure, joy, optimism, excitement and sense of humor each have positive biological and physiological effects. So, while counteracting chronic stress and reducing negativity is important, another key to better health is finding happiness.

People who report that they are very happy (with less negative and more positive emotion and optimism) live 4 to 10 years longer than unhappy individuals. More so, those extra years are also lived healthier. Further, people who express positive emotions like joy, cheerfulness, and enthusiasm are 22 percent less likely to develop heart disease than those who don’t. In fact, in a study of nearly 100,000 women, optimists were 30 percent less likely to die from coronary heart disease than pessimists. Happiness, even expressed in a given day, is a statistical predictor of health. In one study, those who reported a more positive mood in one 24-hour period experienced a 50 percent lower death rate over the next five years compared to those who were less happy that day.

The fact that happiness – and its many forms – can improve one’s health raises an important question: Can we choose to be happy? If we’re generally unhappy, can we reset this emotion or are some people too influenced by genetics, upbringing, and environment to modify their emotional state?

Of course, separating cause and effect is difficult here. Does one’s negativity cause stress that causes negative health outcomes? Likewise, can day-to-day happiness alone reverse negative health trends? Evaluating the impact of stress levels on lifestyle change is complex.

Factors like genetics and the environment can impact both disease prevalence and mood. But regardless of etiology, when faced with such adversity, happy people optimize their health and cope better than those who are unhappy.

Happily, there is mounting evidence that our moods and happiness can be modified by some simple activities and interventions that reshape our thoughts and moods each day.

In the series: The Pursuit of Health

- What Causes Health

- Who Provides Care

- Self-Managing Chronic Disease

Further Reading

External stories and videos.

UK Appoints a Minister for Loneliness

Ceylan yeginsu, new york times.

Since Britain voted to leave the European Union more than a year ago, Europeans have mockingly said that the decision will result in an isolated, lonely island nation. But Britain, in fact, already has a serious problem with loneliness, research has found, affecting more than nine million people, prompting Prime Minister Theresa May to appoint a minister for loneliness.

Change Your Mindset, Change the Game

Stanford professor, athlete and psychologist Alia Crum investigates the role of mindsets in affecting health behaviors and outcomes.

How to Make Stress Your Friend

Kelly McGonigal

Psychologist Kelly McGonigal urges us to see stress as a positive, and introduces us to an unsung mechanism for stress reduction: reaching out to others.

The Game That Can Give You 10 Extra Years of Life

Jane McGonigal

In this moving talk, McGonigal explains how a game can boost resilience — and promises to add 7.5 minutes to your life.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Mental Illness Isn’t All in Your Head

A “formulation” gathers the biological, psychological and social factors that lead to a mental illness — and offers clues to the way out of suffering.

By Lisa Pryor

Contributing Opinion Writer

When psychiatry is in the news, so often it is for a controversy over diagnosis. Do psychiatrists mislabel grief as depression? Should internet addiction be considered a mental health disorder? Are children with behavioral difficulties too often tagged as having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder?

With such a focus on diagnosis and classification, you would be forgiven for thinking that psychiatry is a profession devoted merely to sorting and labeling humans. This is highlighted by the common description of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders — the thick volume published by the American Psychiatric Association listing the various diseases of the mind — as the “bible” of psychiatry.

In reality, the D.S.M., the abbreviation by which it is commonly known, is more like a dictionary than a bible. It is an explanation of the human mind no more than a dictionary is an explanation of literature.

There is another psychiatry concept that gets less of an airing in public but that could be more helpful for understanding how many psychiatrists think about the mind — and how any of us can think about mental suffering. This concept is the psychiatric formulation.

If a diagnosis is a label, a formulation is more like a story. In a few sentences, a formulation gathers up all the biological, psychological and social factors that have led to a person becoming unwell and considers how these factors interconnect. In doing so, it provides clues to the pathway out of suffering.

This story might take into account the individual’s genetic predisposition for mental illness, attachment to a primary caregiver as a child, developmental trauma, intellectual functioning, economic circumstances, illicit drug use or complications created by physical illness, such as thyroid disease or chronic pain.

As you may have noticed, these factors are not located solely within the brain, nor are they solely located within the individual.

For me, a medical doctor training to be a psychiatrist, the formulation is a reminder that however far our understanding of the brain advances, in terms of its myriad receptors and neurotransmitters, this organ never exists in a vacuum.

The brain exists within a human body, which in turn exists within a family, a culture, a society, an economy. When factors outside the brain contribute to mental illness, then the solutions to those problems may also exist outside the brain. Indeed, some of the most valuable mental health interventions we have might be preventive. I am thinking here of measures to reduce poverty and child abuse, for example.

Let’s consider an example of a formulation. The diagnosis “major depressive disorder” may not tell you much about a person, but consider a formulation for an individual, which might go something like this: “Forty-six-year-old single mother of two presents with a three-month history of depressive symptoms including low mood, insomnia and poor appetite (with weight loss). Her condition was precipitated by psychosocial stressors, including unstable housing and credit-card debt since the breakdown of her marriage eight months ago. This is on a background of an introverted and passive temperament and a childhood in which her parents encouraged dependency, and this was followed by a marriage in which her husband had complete control of finances. There is a strong family history of depression; her mother and maternal grandfather were hospitalized for this condition. Protective factors include a strong network of friends and a willingness to engage with therapy.”

Obviously people who all have the same diagnosis of “major depressive disorder” can have different formulations. The combination of predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating and protective factors will be different for everyone. If a diagnosis is a stamp, a formulation is more like a fingerprint, unique to each individual.

In the hypothetical example above, treatment may not be limited to medication; it might include a suite of other interventions. Long-term psychotherapy to help build confidence and a sense of self-efficacy might be one element, as would other measures that on the face of it might not seem to be within the realm of psychiatric treatment. For example, it would make sense to provide assistance for obtaining safe and affordable housing if unstable living arrangements helped cause spiraling feelings of hopelessness. Similarly, helping the person find a course to learn budgeting skills or get a job might be beneficial.

If you have come to believe from what you have read that psychiatry is the study of the isolated and disembodied brain, you might be surprised to learn how important this component of the psychiatric process is and how long it has been around.

One of the early key proponents of this biopsychosocial model of mental illness was George L. Engel, an internist and psychiatrist who practiced in Rochester, N.Y., for most of his career, starting in the 1940s. Working with both physical and psychiatric illness, he was well placed to consider the relationship between the mind and the body, between emotions and disease.

He set out his ideas succinctly in 1977 in a landmark article in the journal Science. In this essay, Engel articulated why psychiatry should not be drawn too far into the medical model of disease, and why, in fact, medicine itself would do well to look beyond this model, which he suggested did not fully account for mental illness or physical illness, for schizophrenia or even diabetes.

The biopsychosocial formulation dovetails nicely with more recent developments in mental health, such as trauma-informed care, a model developed for patients who have suffered traumatic experiences such as abuse and assault. The goal is to avoid traumatizing them again in offering the very services meant to help them. Often this approach is summarized as moving from thinking, “What is wrong with you?” to considering, “What happened to you?” Like the formulation, a label is reframed as a story.

The biopsychosocial formulation also offers much to all of us, when we think about our own well-being and mental health, the factors leading to our own flourishing, or its opposite.

None of us are static objects, we have histories and stories, we change over time. Who we are today is influenced by the sum of the things that have happened to us along the way, but how things are today is not how they are always destined to be.

So when something is wrong we would do well to ask not just, “What is my diagnosis?” but instead, “What is my formulation?”

Lisa Pryor, a medical doctor, is the author, most recently, of “A Small Book About Drugs” and a contributing opinion writer.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the group that publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It is the American Psychiatric Association, not the American Psychiatric Society.

How we handle corrections

- Contributors

- What's New

- Other Sports

- Marie Claire

- Appointments

- Business News

- Business RoundUp

- Capital Market

- Communications

- BusinessAgro

- Executive Motoring

- Executive Briefs

- Friday Worship

- Youth Speak

- Social Media

- Love and Relationships

- On The Cover

- Travel and Places

- Visual Arts

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Philanthropy

- Social Impact

- Environment

- Mortgage Finance

- Real Estate

- Urban Development

- Youth Magazine

- Life & Style

- Love & Life

- Travel & Tourism

- Brand Intelligence

- Weekend Beats

- Ibru Ecumenical Centre

- News Feature

- Living Healthy Diet

- Living Wellbeing

- Guardian TV

Health and wellness starts from the mind

- Good health

Good health starts from the mind. As cliché as this sounds, your mind and emotional state can have a profound effect on your physical body, your spiritual experience, and your over-all quality of life. People experience a variety of emotions that either have a positive or negative effect within the body. These emotions may include: happiness, sadness, anger, excitement, depression etc.

Feelings and thoughts are associated with specific parts of the body and may be linked to different illnesses or ailments. Those who have good emotional health are often mindful of their thoughts and feelings and have cultivated habits and ways of coping with stressors they experience daily in their lives. Chemicals released within the body cause individuals to experience a variety of emotions. For example, when serotonin is released in the body, a happy feeling is experienced.

Similarly, emotions can cause the body to experience physical reactions. For example, if an individual feels nervous or anxious, the feeling may be observed in their stomach which is commonly described as “butterflies”. Even if an individual has developed these coping mechanisms, some life event (positive and negative) can disrupt an individual’s emotional health and their ability to deal with stress. The death of a loved one, the loss of a job, and money problems may cause an individual to experience strong feelings of sadness, stress, and anxiety.

The body responds to thoughts and feelings and as a result of poor emotional health, it may bring about a variety of physical signs and symptoms such as: Weight gain or loss, back pain, chest pain, headache, sweating, insomnia, constipation, lack of appetite, voracious eating, and extreme general fatigue. These are enhancing factors of poor emotional health and can make individuals more prone to diseases and illnesses. The reason is that, they will be less likely to eat healthy meals, exercise or take their prescribed medication. They may also be more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol which worsens their state of mind and subsequently, their physical health. On the other hand, good emotional health can broaden the perspective of an individual and build resilience to negative emotional experiences over time. According to research, a good emotional state of being has benefits for both physical and mental health which includes: better sleep, fewer illnesses, faster recovery from stress, and an overall better sense of happiness.

Tips on how to improve and maintain good emotional health. Here are a few tips on how to improve and maintain good emotional health:

• Learn to identify your emotional triggers. The emotional health of a person can be improved by the person learning to identify what triggers his /her emotional responses. The moment these triggers are spot on, the easier it becomes to control and manage the emotional health successfully.

• Take out time to relax. It is very important take out time to relax and free your mind from the very numerous worries and hustles of this world. Go on vacations, go to the movies or a soothing musical concert, go to the spa for a massage, take yoga classes e.t.c. Basically, make sure you relax.

• Focus on positive experiences. Focusing exclusively on problems at work, school, or home can cause an individual to overemphasize negative feelings more often. There is actually no way to completely avoid negative feelings; however, they can be managed and properly addressed. It is important to focus on positive experiences and feelings when negative feelings begin to get in the way. Identify hobbies and activities that you enjoy and would distract you from stressors.

• Express emotions appropriately. There are times when your emotions may go beyond control. In such cases, find ways to express those emotions rather than bottling them up and allowing them eat deep within, because the truth is that those stacked up emotions will eventually affect your physical health. Discuss your feelings with a loved one, or seeking counsel from a good counsellor. Ensure to find an outlet for those negative emotions as it will improve your ability to deal with stressors and boost a good mood.

• Cultivate healthy habits. The human mind and body are connected and the condition of either will affect the other. Eating healthy meals, getting enough rest/sleep and exercising regularly can improve one’s emotional health and subsequently one’s physical health. Healthy habits can help expel toxic emotions that may be detrimental to our overall health. Ensure to avoid using drugs and alcohol as shortcuts or coping mechanisms, as these only worsens the overall wellbeing.

In this article

- Bunmi George

cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Why are you flagging this comment?

I disagree with this user

Targeted harassment - posted harassing comments or discussions targeting me, or encouraged others to do so

Spam - posted spam comments or discussions

Inappropriate profile - profile contains inappropriate images or text

Threatening content - posted directly threatening content

Private information - posted someone else's personally identifiable information

Before flagging, please keep in mind that Disqus does not moderate communities. Your username will be shown to the moderator, so you should only flag this comment for one of the reasons listed above.

We will review and take appropriate action.

Get the latest news delivered straight to your inbox every day of the week. Stay informed with the Guardian’s leading coverage of Nigerian and world news, business, technology and sports.

Please Enable JavaScript in your Browser to Visit this Site.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Build Your Resilience in the Face of a Crisis

- Rasmus Hougaard,

- Jacqueline Carter,

- Moses Mohan

Three strategies for taking care of your mental health.

As the spread of Covid-19 dominates the news, we have all seen and experienced the parallel spread of anxiety. Indeed, in a crisis, our mental state often seems only to exacerbate the challenge, becoming a major obstacle in itself. How can we change this? Mindfulness experts Rasmus Hougaard and Jacqueline Carter show, by way of the Buddhist parable of the second arrow, how the mind’s response to crisis is a choice we can control. They offer three strategies — calm and clear the mind; pull back and reflect; connect with others through compassion — for restoring yourself and building mental resilience.

In these difficult times, we’ve made a number of our coronavirus articles free for all readers. To get all of HBR’s content delivered to your inbox, sign up for the Daily Alert newsletter.

As the spread and far-reaching impacts of Covid-19 dominate the world news, we have all been witnessing and experiencing the parallel spread of worry, anxiety, and instability. Indeed, in a crisis, our mental state often seems only to exacerbate an already extremely challenging situation, becoming a major obstacle in itself. Why is this and how can we change it? As the CEO of a firm that brings mindfulness to companies to unlock new ways of thinking and working, let me share a bit about how the mind responds to crises, like the threat of a pandemic.

Even without a constant barrage of bad or worrisome news, your mind’s natural tendency is to get distracted. Our most recent study found that 58% of employees reported an inability to regulate their attention at work. As the mind wanders, research has shown that it easily gets trapped into patterns and negative thinking . During times of crisis — such as those we are living through now — this tendency is exacerbated, and the mind can become even more hooked by obsessive thinking, as well as feelings of fear and helplessness. It’s why we find ourselves reading story after horrible story of quarantined passengers on a cruise ship, even though we’ve never stepped foot on a cruise ship, nor do we plan to.

When your mind gets stuck in this state, a chain reaction begins. Fear begins to narrow your field of vision, and it becomes harder to see the bigger picture and the positive, creative possibilities in front of you. As perspective shrinks, so too does our tendency to connect with others. Right now, the realities of how the coronavirus spreads can play into our worst fears about others and increase our feelings of isolation, which only adds fuel to our worries.

Watching the past month’s turmoil unfold, I have been reminded of the old Buddhist parable of the second arrow. The Buddha once asked a student: “If a person is struck by an arrow, is it painful? If the person is struck by a second arrow, is it even more painful?” He then went on to explain, “In life, we cannot always control the first arrow. However, the second arrow is our reaction to the first. And with this second arrow comes the possibility of choice.”

We are all experiencing the first arrow of the coronavirus these days. We are impacted by travel restrictions, plummeting stock prices, supply shortages etc. But the second arrow — anxiety about getting the virus ourselves, worry that our loved ones will get it, worries about financial implications and all the other dark scenarios flooding the news and social media — is to a large extent of our own making. In short, the first arrow causes unavoidable pain, and our resistance to it creates fertile ground for all the second arrows.

It’s important to remember that these second arrows — our emotional and psychological response to crises — are natural and very human. But the truth is they often bring us more suffering by narrowing and cluttering our mind and keeping us from seeing clearly the best course of action.

The way to overcome this natural tendency is to build our mental resilience through mindfulness. Mental resilience, especially in challenging times like the present, means managing our minds in a way that increases our ability to face the first arrow and to break the second before it strikes us. Resilience is the skill of noticing our own thoughts, unhooking from the non-constructive ones, and rebalancing quickly. This skill can be nurtured and trained. Here are three effective strategies:

First, calm the mind.

When you focus on calming and clearing your mind, you can pay attention to what is really going on around you and what is coming up within you. You can observe and manage your thoughts and catch them when they start to run away towards doomsday scenarios. You can hold your focus on what you choose (e.g. “Isn’t it a gift to be able to work from home!”) versus what pulls at you with each ping of a breaking news notification (e.g. “Oh no…the stock market has dropped again.”).

This calm and present state is crucial. Right away, it helps keep the mind from wandering and getting hooked, and it reduces the pits of stress and worry that we can easily get stuck in. Even more importantly, the continued practice of unhooking and focusing our minds builds a muscle of resilience that will serve us time and time again. When we practice bringing ourselves back to the present moment, we deepen our capacity to cope and weather all sorts of crises, whether global or personal. (Fortunately, there are a number of free apps available to help calm your mind and increase your own mindfulness.)

Look out the window.

Despair and fear can lead to overreactions. Often, it feels better to be doing something … anything … rather than sitting with uncomfortable emotions. In the past few weeks, I have felt disappointment and frustration with important business initiatives that have been adversely impacted by Covid-19. But I have been trying to meet this frustration with reflection versus immediate reaction. I know my mind has needed space to unhook from the swirl of bad news and to settle into a more stable position from which good planning and leadership can emerge. So, I have been trying to work less and to spend more time looking out my window and reflecting. In doing so, I have been able to find clearer answers about how best to move forward, both personally and as a leader.

Connect with others through compassion.

Unfortunately, many of the circles of community that provide support in times of stress are now closed off to us as cities and governments work to contain the spread of the virus. Schools are shut down, events are cancelled, and businesses have enacted work-from-home policies and travel bans. The natural byproduct of this is a growing sense of isolation and separation from the people and groups who can best quell our fears and anxieties.

The present climate of fear can also create stigmas and judgments about who is to blame and who is to be avoided, along with a dark, survivalist “every person for him/herself” mindset and behaviors. We can easily forget our shared vulnerability and interdependence.

But meaningful connection can occur even from the recommended six feet of social distance between you and your neighbor — and it begins with compassion. Compassion is the intention to be of benefit to others and it starts in the mind. Practically speaking, compassion starts by asking yourself one question as you go about your day and connect — virtually and in person — with others: How can I help this person to have a better day?

With that simple question, amazing things begin to happen. The mind expands, the eyes open to who and what is really in front of us, and we see possibilities for ourselves and others that are rich with hope and ripe with opportunity.

If our content helps you to contend with coronavirus and other challenges, please consider subscribing to HBR . A subscription purchase is the best way to support the creation of these resources.

- Rasmus Hougaard is the founder and CEO of Potential Project , a global leadership development and research firm serving Accenture, Cisco, KPMG, Citi, and hundreds of other organizations. He is the coauthor, with Jacqueline Carter, of Compassionate Leadership: How to Do Hard Things in a Human Way and The Mind of the Leader: How to Lead Yourself, Your People, and Your Organization for Extraordinary Results .

- Jacqueline Carter is a senior partner and the North American Director of Potential Project. She has extensive experience working with senior leaders to enable them to achieve better performance while enhancing a more caring culture. She is the coauthor, with Rasmus Hougaard, of Compassionate Leadership: How to Do Hard Things in a Human Way and The Mind of the Leader – How to Lead Yourself, Your People, and Your Organization for Extraordinary Results .

- MM Moses Mohan is a leadership expert with Potential Project, formerly with McKinsey & Company and former Zen monk.

Partner Center

- Welcome to the Spring Semester

- Centers & Initiatives

Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education

In this section.

- Complete Collection

- Racial Justice, Racial Equity, and Anti-Racism Reading List

- Katie Rose Guest Pryal

“ Academia isn ’ t an easy place to be if your brain isn ’ t quite right. Colleagues carelessly call each other ‘schizo ’ and ‘bipolar ’ . Another colleague is fired--easy enough to do these days, when most college teachers no longer have tenure--for ‘instability ’ . In these ways and many more, psychiatrically disabled people working in higher education are reminded every day that their privilege, their very livelihoods, can be stripped away by the groundless suspicions of others. Their lives can be, in an instant, interrupted. The essays in this book cover topics such as disclosure of disabilities, accommodations and accessibility, how to be a good abled friend to a disabled person, the trigger warnings debate, and more. Written for a popular audience, for those with disabilities and for those who want to learn more about living a disabled life, Life of the Mind Interrupted aims to make higher education, and the rest of our society, more humane. ” -- Book cover .

Pryal, Katie Rose Guest. Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education . Chapel Hill, NC: Blue Crow Publishing, 2017.

“In Sickness and in Health”: Writing Life through the Essay

Introduction

‘An Essay-Writer must practise in the Chymical Method’: The Early Royal Society’s Adoption of the Essay Genre

This paper will examine the use made of the emergent genre of the essay by seventeenth century members and associates of the Royal Society. Robert Boyle is often cited as the epitome of the experimentalist essay writers, who used the genre to publish their findings. However, works titled as essays were generally written to advance the Society as well as the scientific method itself. Abraham Cowley's scientific interests found expression in a short prose pamphlet published in 1661, but he turned to the essay when making the case for his personal retreat and agricultural life being the best engagement, he could have with the natural world. William Petty turned to essay writing in his later life, and his essays put a Baconian passion for quantitative precision to political use. Joseph Glanvill’s Scepsis Scientifica (1665) earned him a Society fellowship, and he continued to use the essay form to promote the activities and philosophy of the Society thereafter. Boyle can be seen as an exception to, rather than the epitome of, the use of the essay form by Royal Society members and associates, yet the essay was still a vital tool for the promotion of the new natural philosophy.

Caroline Curtis took their first degree in English Literature at the University of Oxford and is currently undertaking doctoral work at the University of Birmingham. Their thesis examines autobiographical practices of members of the early Royal Society, arguing that such practices were essential, rather than incidental, to the Society's success.

‘And Other Essays’: Illness Narratives and Creative Non-Fiction

This paper discusses the changing forms of illness narratives, where contemporary works are moving away from traditional modes of pathography or chronological memoir, to something closer to the essay form. Thinking especially about collections of works such as Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays From a Nervous System (2017) by Sonja Huber and The Empathy Exams: Essays (2014) by Leslie Jameson, I explore the idea of the essay compilation, what relationship each piece has with one another, and what this indicates about current approaches to illness memoir and medical experiences. Does the essay form suggest a different representational relationship with the illness experience? Is the essay a means of marking the chronicity of certain conditions? Is the essay a unique domain of the body, and the self?

Dr Marie Allit is a Humanities and Healthcare Fellow at the University of Oxford, on the project ‘Advancing Medical Professionalism: Integrating Humanities Teaching in the University of Oxford’s Medical School’. She is also the Postdoctoral Research Assistant for the Northern Network for Medical Humanities Research, at the University of Leeds. Marie is a collaborator on the Wellcome small grant project ‘Senses and Modern Health/care Environments: Exploring interdisciplinary and international opportunities’, led by Dr Victoria Bates. She is also a co-investigator on a Wellcome Discretionary Award, ‘Thinking Through Things’, which aims to develop a cross-disciplinary ECR research network that engages with the Wellcome Collection, in connection with the Northern Network for Medical Humanities Research and Durham’s Institute for Medical Humanities. Marie completed her PhD in English Literature at the University of York in 2018, focusing on experiences and representations of spaces and senses in First World War medical caregiving narratives. Marie’s research focuses on medical life writing; practitioner health; medical spaces and senses; and early 20th century surgery.

“To Be Ill and Writing”: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and the Confessional Essay

The “need to bind things together again makes pathographical literature a rich source for the literary critic.” But what if the writer of the pathography, or illness narrative, is herself a literary critic—one, no less, whose “mother’s milk has been deconstruction”, a critical orientation wary of clean-cut dualisms and tidy unities? This dissertation traces the ways in which, from the critical moment of her breast cancer diagnosis in 1991 through to her death in 2009, the monographs and essay collections, poems and art-objects of queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick reach across forms, genres, and styles, in such a way that the ‘critical’ and the ‘confessional’ begin to, in Sedgwick’s own words, “intimate[ly] adhe[re]”. This paper will suggest that these “adventures in applied deconstruction” offered Sedgwick, and continues to offer readers, spaces in which to think, write and live chronic illness in ways that side-step the conventional, fatalistic narrative arc which often structures contemporary illness narratives. As such, this paper will demonstrate some of the ways in which Sedgwick’s experiments with the essay form—with “transfigur[ing …] the energies of some received forms of writing that were important to [her]”—offered her, as a critic, as a poet, as a reader, a means to theorise (and find new ways of experiencing) optimism, pleasure and love in the face of terminal illness.

Rowena Gutsell is a first year DPhil (PhD) student at the University of Oxford. Her thesis explores the place of close reading within contemporary queer literary theory. Her research interests include reader-response, affect and emotion, poetry and poetics, and queer theory.

Virginia Woolf, Eccentricity, and the Essay

Professor Dame Hermione Lee was President of Wolfson College from 2008 to 2017 and is Emeritus Professor of English Literature in the English Faculty at Oxford University. She is a biographer and critic whose work includes biographies of Virginia Woolf (1996), Edith Wharton (2006) and Penelope Fitzgerald (2013, winner of the 2014 James Tait Black Prize for Biography and one of the New York Times best 10 books of 2014). She has also written books on Elizabeth Bowen, Philip Roth and Willa Cather, an OUP Very Short Introduction to Biography, and a collection of essays on life-writing, Body Parts. Her most recent book is a biography of the playwright Tom Stoppard, Tom Stoppard: A Life. From 1998 to 2008 she was the Goldsmiths’ Professor of English Literature at Oxford. She is a Fellow of the British Academy and on the Council of the Royal Society of Literature, as well as a Trustee of the Wolfson Foundation and a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The Impersonal Essay

What is the opposite of the much-maligned personal essay? This talk thinks through a taxonomy of opposites (the impersonal essay, the political essay, the collective essay) to reveal the specific aesthetic and historical stakes of the personal essay. At the heart of the personal essay, I argue, resides at once an illusion of a purely private selfhood and the fictionalized breach of that privacy through a risky act of address. As the illusion of a purely private selfhood becomes increasingly difficult to sustain, the narration of the breach must become increasingly spectacularized, resulting in the tawdriness and self-indulgence frequently attributed to personal essays today.

Dr Merve Emre is associate professor of English at the University of Oxford. She is the author of Paraliterary: The Making of Bad Readers in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), The Ferrante Letters (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), and The Personality Brokers (Doubleday: New York, 2018), which was selected as one of the best books of 2018 by the New York Times, the Economist, NPR, CBC, and the Spectator, and has been adapted for CNN/HBO Max as the documentary feature film Persona. She is the editor of Once and Future Feminist (Cambridge: MIT, 2018), The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway (New York: Liveright, 2021), and The Norton Modern Library Mrs. Dalloway (New York: Norton, expected in 2022). Her essays and criticism have appeared in publications ranging from The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, Harper's, The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, and the London Review of Books to American Literature, American Literary History, and Modernism/modernity. In 2019, she was awarded a Philip Leverhulme Prize, and her work has been supported by the Whiting Foundation, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Leverhulme Trust, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Quebec, and the Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin, where she is a fellow from 2020-2021. She is currently finishing a book titled Post-Discipline: Literature, Professionalism, and the Crisis of the Humanities (under contract with the University of Chicago Press) and starting a book called Woman: The History of an Idea (under contract with Doubleday US / Harper Collins UK).

More Videos

"But I’m nothing special…”: Reflections on Writing the Lives of ‘Ordinary’ People

A Life in Text: the Biographical Material in Constance Garnett’s Translations

Art & Action: Authorship, Celebrity, and Politics

Artefacts as Actors at Abydos

Balancing Acts: Negotiating Relations in Response to Trauma in life-writing

Edward Maufe, Architect and Cathedral Builder

El Greco: The Bivalent Artist

From the stave to sounds, into words

Inscribing biographies in Global South History

Into the oppressor’s mind

Ivor Gurney: Dweller in Shadows

Jenny Diski: A Celebration

- Search the site GO Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

Poor Body Health May Indicate Poor Mental Health—Experts Discuss Mind-Body Connection

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/30mwNuGT_400x400-KaitlinSullivan-396e889683c84931bd30f939325d60ea.jpg)

- New research found that poor physical health can serve as a strong indicator of poor mental health.

- The indication was particularly strong regarding the metabolic, liver, and immune system's correlation to mental well-being.

- Experts recommend individuals keep track of physical and mental symptoms to help them better understand the connection between their physical health and mental well-being.

According to new research, poor physical health could be a strong indicator of mental health issues—even stronger than brain scans.

Scientists have long studied the connection between mental well-being and physical well-being. The ability to use one to clarify the other helps healthcare professionals and patients alike.

About 20% of American adults live with mental illness. In a 2021 National Institutes of Health survey, nearly half of all Americans surveyed reported feeling depressed or anxious.

“Paying attention to the rest of the body that is not the brain is definitely something we need to be doing in psychiatric patients, not just to take care of those patients but to make sure we know what is going on,” John Denninger, MD, PhD , director of integrative science and clinical training at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, told Health .

Getty Images / Kathrin Ziegler

What the Research Says

To expand the growing body of research on how mental and physical health are closely linked, researchers in Australia used data banks of adults in the U.S., U.K., and Australia.

The study compared nearly 86,000 people with psychiatric disorders to about the same number of people who did not. The psychiatric disorders ranged from neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder , to depression and generalized anxiety disorder.

The team used a combination of markers found in blood, urine, and other samples that correlated with the function of seven different body systems: lungs, musculoskeletal, kidney, metabolic, liver, cardiovascular, and immune systems. They also used data from MRI brain scans. Armed with this information, the researchers divided people into different groups based on the quality of their physical health.

The data revealed that poor physical health, particularly when it involved the metabolic, liver, or immune system, was a better indication of poor mental health than brain changes that show up on an MRI.

The study’s lead author, Ye Ella Tian, MBBS, PhD, a Mary Lugton Postdoc Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne’s Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre in Australia, noted that her team was surprised by the findings.

“Mental illnesses are typically understood as disorders of the brain,” she explained. The results of the new study did not suggest this understanding is incorrect, but did “indicate that poor body health is also a very important component of mental illness.”

The research was not able to determine whether or not the connection was related to people having a more difficult time taking care of their physical health, if they also were struggling with poor mental health, or if the connection is related to something else. Tian noted that further research will need to examine why poor mental health appeared to be tied specifically to poor liver, immune system, and metabolic health .

For now, “mental health professionals and physicians need to work more closely together to monitor and attend to the physical health of these people, even from very early stages of psychiatric and mental care,” she emphasized.

Deciphering Mental Illness and Physical Illness

While it’s useful to make the distinction between physical illnesses that are related to mental health and those that are not, Tied noted that a clear distinction is questionable.

Scientists are still unraveling many mysteries of the brain, including the influence a person’s thoughts and mental state have on their physical body. According to Dr. Denninger, the concept of mind-body connection is a bit of a false dichotomy since the brain is part of the body.

“We benefit ourselves when we recognize that the brain and the rest of the body is one system,” he explained. “It gets rid of some of these problems with trying to determine: Is it in the brain or in the body?”

Tian suspects the relationship between mental health and physical health is both complex and bidirectional, meaning physical health and mental health affect each other.

Past research has documented how mental illnesses such as anxiety can create a feedback loop with a wide range of physical symptoms, such as stomach aches, dizziness, or chest pain. Because of this, people with psychiatric conditions may not get diagnosed with physical illness in the same ways that healthcare providers diagnose people without the conditions.

“It’s not unusual for people who have a psychiatric illness for everything to be prescribed to the mental illness, so many ailments get missed,” noted Dr. Denninger.

So how can you determine which physical conditions are caused by a poor mental state?

“My glib answer to that is you can’t,” Dr. Denninger stressed. “These things are so closely intertwined that it’s very difficult to tell what’s being caused by the brain and what is being caused by the body. It’s a complex system...anytime we have something going on in our bodies, our brain plays a role.”

The important thing to understand is that it’s vital for people treating patients with psychiatric conditions to also enable people to take care of their physical health and address associated concerns.

“We know that mental illness is associated with reduced life expectancy,” added Tian. “And the majority of deaths in people with mental illness relates to poor physical health.”

Tracking Symptoms of Mental and Physical Ailments

While it’s difficult to draw a line between mental and physical ailments, Dr. Denninger recommended keeping a log of symptoms, both physical and mental (or emotional), to better understand what may be triggering a physical symptom.

For example, does a person tend to get sick more often when they are experiencing poor mental health, or does it seem to be unrelated?

“The big mystery about the mind-body connection is not the fact that there is a connection, but understanding for all these disorders,” he stressed. “What is the path from what happens in our brains to what we perceive in our bodies?”

Tian YE, Di Biase MA, Mosley PE, et al. Evaluation of brain-body health in individuals with common neuropsychiatric disorders . JAMA Psychiatry . Published online April 26, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0791

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About mental health .

NIH COVID-19 Research. Mental health .

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) .

Ilyas A, Chesney E, Patel R. Improving life expectancy in people with serious mental illness: should we place more emphasis on primary prevention? Br J Psychiatry . 2017;211(4):194-197. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.117.203240

Related Articles

January 1, 2017

13 min read

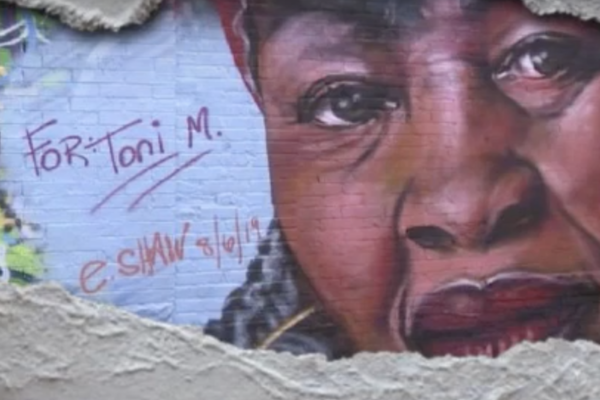

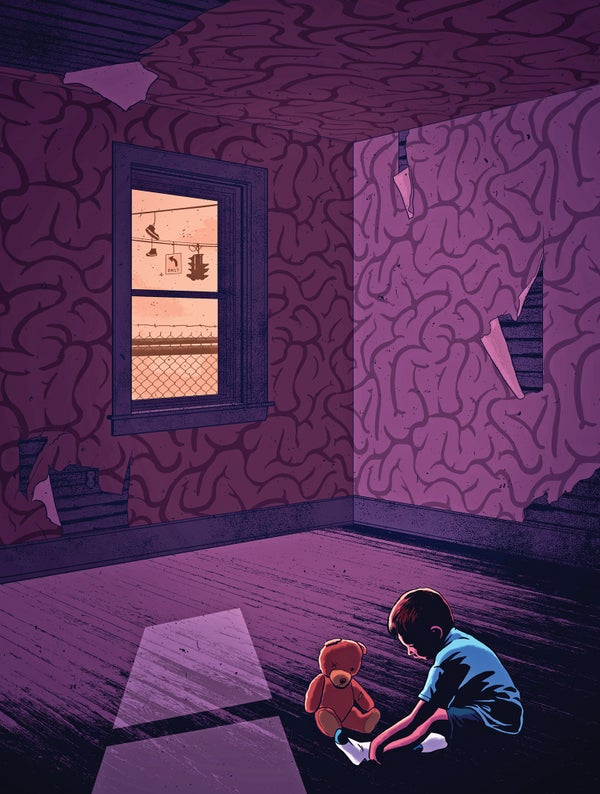

Does Poverty Shape the Brain?

Growing up in a poor family can leave a mark on the developing brain. Understanding how and why has important implications for educators and society

By John D. E. Gabrieli & Silvia A. Bunge

Imagine that you are a child again. In this version of your childhood, you arrive at school hungry, tired and anxious. Your mother was not able to pay the rent this month. The cupboards are bare. A car alarm went off late last night, and it fell to you to soothe your baby brother back to sleep. You woke up early to take the bus across town, and by the time the school bell rings, you have so much on your mind that it is difficult to concentrate.

Myriad stressors collect and compound for children who grow up in poverty. Although their stories are all different, we know that the many challenges they face can have a lasting impact. In the U.S., one in four infants and toddlers lives below the federal poverty line.

Despite our societal desire to see education as an equalizer that elevates people from difficult circumstances, social scientists have known for some time that the truth is not so simple. The income of the family you are born into has a powerful effect on educational outcomes and, in turn, future job prospects and economic security. Education researcher Sean Reardon and his colleagues at Stanford University recently completed an analysis showing that children in school districts with high levels of poverty score an average of four grade levels below peers from the most affluent districts on tests of reading and math. And kids born to a low-income family have a far worse chance of getting a college degree than children born to a high-income family, in turn constricting economic and career opportunities.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As disquieting as these inequities may be, this so-called income-achievement gap is not new. Educators and social scientists have been tracking the relation between school success and poverty for roughly half a century. Although there is now some evidence that the divide may be starting to narrow—after three decades of expansion—the pace of change is too slow to help this generation or even the next. In fact, it could take 60 to 110 years to close the gap at its current rate of change, according to a 2016 calculation by Reardon.

In the meantime, strong evidence has begun to emerge about how family income relates to the development of a child's brain. In essence, scientists are finding anatomical differences tied to poverty—and some of this variation has implications for education. Everything that is learned, after all, depends on the brain's plasticity, its ability to grow and change. The new discoveries, in turn, serve not only as an added call to action but may also fuel ideas about how to best intervene.

Building the Brain

At birth, we have a rich supply of both gray matter, which is primarily composed of cell bodies, and white matter, which encompasses the tracts of cablelike axons that transmit signals from one neuron to the next. We start out with more neural material than we strictly need. The brain is sculpted into a more efficient organ as we learn and grow, strengthening some networks, eliminating others.

From late childhood through early adulthood, a part of the brain called the neocortical gray matter steadily thins. This area comprises six layers of cortex that cover the brain and support perception, language, thought and action. Researchers believe this thinning reflects a massive pruning of cells and the connections between them. Also during this life stage, white matter develops in ways that improve the connectivity of large-scale networks across the brain.

Scientists have only recently begun to examine how socioeconomic status (SES) might influence the normal course of brain development. SES is a complex construct that is measured by combining educational attainment, income and occupation. There is substantial variation among individuals and families at every socioeconomic level, making it hard to generalize about an individual's experiences. In addition, disadvantages, where they exist, tend to co-occur or correlate with one another, so it is difficult to relate specific circumstances to particular outcomes. For example, very low SES or poverty is associated with poor health, family instability and high stress. It can also entail malnutrition, limited health care, modest language and intellectual stimulation at home, inferior schools and lowered social expectations. These conditions could all, in turn, affect neural and cognitive development.

A classic series of experiments conducted in the 1960s at the University of California, Berkeley, proved that adverse early environments harm the brain in rodents. Neuroscientist Marian Diamond showed that rearing rats in an impoverished environment—lacking toys and opportunities to socialize—hampered their brain development and ability to learn.

Click or tap to enlarge

Credit: Rob Dobi; Sources: Child Poverty in America 2015: National Analysis . Children's Defense Fund, September 13, 2016 ( children in poverty ); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ( poverty line ); Child Poverty and Intergenerational Mobility , by Sarah Fass et al. National Center for Children in Poverty, December 2009 ( poverty at age 35 ); Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States: 45 Year Trend Report . Revised. Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Education and Penn Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy, 2015 ( college completion for bottom quartile ); “Is College Worth It? Clearly, New Data Say,” by David Loenhardt, in the Upshot, New York Times . Published online May 27, 2014 ( pay increase with college degree )

Such studies would be unethical in humans, but a long-term follow-up of Romanian children who had been warehoused in an appalling system of state orphanages found similar outcomes. Beginning in 2001, developmental psychologists Charles A. Nelson III of Harvard University, Nathan A. Fox of the University of Maryland and Charles H. Zeanah, Jr., of Tulane University compared kids who remained trapped in that system with those who escaped to foster care or adoption and found dire emotional and cognitive repercussions for the first group. They confirmed that the environment can shape cognitive and brain growth and showed that a supportive intervention can substantially ameliorate early privations.

Seeing the Difference

Most children growing up in poverty face some adversity, but it is rarely as extreme as the absence of human interaction and enrichment experienced by the Romanian orphans. Nevertheless, even lesser deprivation appears to alter brain development. In the past few years several large, high-quality studies using MRI have linked variation in a child's neuroanatomy with family income. In no area are the disparities more striking than in the cortex.

One of us (Gabrieli) has made this observation in his own laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He, Allyson Mackey and their colleagues compared cortical thickness among 58 eighth grade students from lower-income versus higher-income families. The results, published in 2015, revealed that the lower-income group had a thinner cortex in widespread regions of the brain. For all students, regardless of income, a thicker cortex was associated with better scores on statewide tests of reading and math. This study, therefore, directly related family income, brain anatomy and educational achievement.

In the same year, cognitive neuroscientist Kim Noble of Columbia University and her colleagues published findings from an MRI examination of 1,099 children ages three through 20. They discovered that cortical surface area was larger in children with greater family income. Critically, they found that small differences in income among families earning less than $50,000 a year were associated with relatively large differences in surface area. But this pattern did not hold true among kids from families who made more than $50,000. These findings suggest a threshold model in which small disparities in earnings may matter greatly among lower-income individuals, but above a certain income level, these differences have less impact.

Also in 2015 Seth Pollak, a psychologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, published a study of 389 children and young adults, aged four to 22, that examined the relation between household poverty, academic performance and MRI data. He and his colleagues found that people with higher scores on cognitive and achievement tests had greater cortical volumes in the frontal and temporal lobes—and, as in the other studies, poorer children had less cortical gray matter (a finding that in all three studies was unrelated to race or ethnicity).

All of this work is correlational, so it is important to note that it cannot prove whether or not an impoverished environment caused these changes—or, for that matter, whether these differences in structure definitely translate into academic deficits. There are some remarkable students, for example, who do very well in school despite an impoverished background, and we do not know how their neural structure compares. It may resemble that of a more affluent child—or perhaps their brain can compensate, enabling equal academic performance despite differences in brain architecture.

The consistent finding that poverty is associated with a smaller cortex is notable, however, because we associate brain maturation from childhood through young adulthood with a thinning cortex. In fact, several studies have reported that better cognitive abilities are associated with a thinner cortex among adolescents at a given age. (These findings most likely involved children from higher-income families who are more likely to volunteer for research studies.)

Total Gray Matter: Using MRI to track brain development in 77 infants, psychologists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison found that differences associated with socioeconomic status (SES) became increasingly pronounced over time. By age three, toddlers from low-income households showed significantly less gray matter than those raised in wealthier homes. Source: “Family Poverty Affects the Rate of Human Infant Brain Growth,” by Jamie L. Hanson et al., in PLOS One , Vol. 8, No. 12, Article No. e80954; December 11, 2013

On the one hand, a reduced cortex may simply reflect the deleterious consequence of impoverished environments. On the other hand, it could reflect a protective adaptation to such environments. Accelerated thinning could perhaps diminish the influence of negative experiences on the developing brain. Preventing the brain from being shaped by harsh influences over the course of many years could be an evolutionarily adaptive response, helping a child to better cope in adverse conditions—but premature thinning could also reduce education's influence on the developing brain.

A Question of Timing?

Researchers have been trying to determine when brain differences associated with SES first become apparent: Do they start in the womb or as an infant experiences more or less supportive environments after birth? In principle, brain imaging offers a novel way to answer these questions, but findings thus far have been inconsistent.

One 2015 study of 44 infants by cognitive neuroscientist Martha Farah of the University of Pennsylvania and her colleagues found that by one month of age, higher SES (defined by income and maternal education) was associated with larger cortical volume in girls. This finding suggests that differences emerge very early—although it is hard to know what such variation means.

Pollak and his colleagues, however, looked at infants aged five months to four years and in 2013 found that SES-related brain differences were minimal at early ages but increased over time. This gap does not grow indefinitely, however. Investigation later in life has yielded no evidence for widening brain differences after early childhood.

It is also important to consider the specific influences that may shape development during these years. Another study by Farah linked home environment to brain development. Researchers visited homes when children were four and then again at eight years of age, and both times they measured environmental stimulation, such as exposure to books, conversation, trips and music.

When the same group of kids reached adolescence, they were given MRI scans. The researchers found that a stimulating home at age four, but not at age eight, predicted greater cortical thickness in the frontal and temporal cortex. It may be that the home environment has a particularly powerful influence on brain development in the early childhood years—or that by age eight, school and social peers exert greater influence than the home does.

It is also possible that, given the range of factors related to socioeconomic status, there may not be a single or simple answer to the question of when brain differences first emerge. Furthermore, there may not be a special or “critical” period of development that is uniquely potent in predicting long-term outcomes. It seems logical that early preventive help is more likely to be effective than remedial support after a child has fallen behind, but education occurs continuously through a child's development and matters at all ages.

Finding Ways to Help

Early experience does not determine outcomes; it merely influences their probability. Given individual variation in response to adversity, we cannot and should not make assumptions about a child's potential based on his or her background. The brain, after all, is plastic and continues to change with experience over a life span.

Yet the longer we wait to get started, the more intensive the effort we may need to counteract the effects of early adversity. The detriments associated with the Romanian orphanages, for example, were not as pronounced among kids placed into family foster care early in childhood. The best solution is therefore prevention, and the next best is remediation. That means that tackling income inequality—and particularly extreme child poverty—at the societal level is of paramount importance, and we hope that neuroscientific evidence can be a spur for shifting policy in that direction. Meanwhile there are some promising steps, inspired by the new findings, that we can take to mitigate the negative effects of indigence on children.

A number of research-based programs for disadvantaged kids are showing good results. Structured group play sessions, such as those offered at Childhaven in Seattle ( left ) or a Tools of the Mind classroom such as this one at Christina Seix Academy in Trenton, N.J. ( right ), can help boost executive functions, a crucial set of skills that includes problem solving, reasoning and planning. Credit: Courtesy of Childhaven ( left ); Courtesy of Tools of the Mind ( right )

There are a number of ways people are trying to improve life outcomes for disadvantaged children—including efforts targeting factors such as sleep and nutrition, cognitive and academic skills, and even finance, career development and parenting strategies for parents and caregivers. Columbia's Noble and her colleagues, for example, have begun a pilot project in which they are testing whether cash transfers to low-income mothers will improve their child's environment and cognition and lower maternal stress. If the threshold model is correct, even modest financial assistance could make a big difference.

Applying techniques from neuroscience may yield unique insight into a given intervention's power. One example of an approach that has been assessed in part through brain measurements is the Kids in Transition to School (KITS) program, developed by psychologist Philip Fisher and his colleagues at the Oregon Social Learning Center, which works with children in foster care and youngsters from low-income families two months before the start of kindergarten and continues until two months after entry.

Aimed at boosting self-regulatory skills, as well as early literacy and prosocial behavior, KITS includes 24 sessions of therapeutic play for children, as well as an eight-session workshop for caregivers. In the classroom, students practice skills such as sitting still and raising their hand, as well as cooperating with their peers. In the workshop, adults learn ways to establish routines with children and encourage good behavior.

Two-generation approaches are effective for many reasons, among them the fact that when parents are involved, children can be helped outside of class and they may not feel as singled out among their peers. In a paper published in 2013 Helen Neville, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Oregon, and her colleagues compared a parent-and-child intervention based on KITS with an intervention focused solely on kids. They found that the combined approach did a better job of boosting nonverbal IQ and language skills. This result was supported by electroencephalography (EEG) findings indicating that the children had a bigger improvement in their brain's capacity to filter out distracting information while focusing on a task.

Both of us are directly involved in testing other interventions for children in poverty that involve their parents and caregivers. As part of the Boston Charter Research Collaborative, Gabrieli works with teachers at six charter school management organizations, serving nearly 7,000 inner-city students in the metropolitan area. The teachers describe their challenges, and researchers at Harvard and M.I.T. offer evidence-based solutions; together they implement and evaluate these programs. Some of the participating students come for brain imaging before and after an intervention so that beneficial brain plasticity can be visualized.

Neuroimaging can also pinpoint cognitive targets for an intervention. The executive functions, for example, are a suite of skills that help people focus on a task, regulate feelings and behaviors, and consider possible consequences before making a decision. They not only increase the odds of staying in school but also appear to be highly vulnerable to poverty. Indeed, executive functions are associated with the prefrontal cortex, an area that shows clear differences in imaging studies that compare children of wealth with those of poverty.

Bunge is involved in the Frontiers of Innovation (FOI) network, established by the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard. This group of researchers and practitioners at multiple sites around the U.S. identifies and develops promising approaches for assisting parents and other caregivers of young children living in adversity. Through FOI, Bunge's team at U.C. Berkeley has been collaborating with Seattle-based Childhaven, which provides therapeutic services to children under age six who have suffered neglect or maltreatment at home. Pilot data from this work suggest that simple classroom activities, such as structured group play that requires children to follow explicit rules and take turns with their classmates, can begin to boost executive functions within 10 weeks.

Several other approaches have shown success in strengthening these functions. One example is the Tools of the Mind curriculum, an alternative to traditional kindergarten developed at Metropolitan State University of Denver by psychologists Elena Bodrova and Debora Leong. The curriculum focuses on building executive functions through “scaffolded” play, which involves targeted interactions with peers and teachers. In 2014 psychologists Clancy Blair and Cybele Raver of New York University found this program was especially beneficial in high-poverty preschools.

What Comes Next?

Although the nature of brain differences was unknown until the past decade, it had to be expected that the profound disparities in educational, occupational and health outcomes associated with childhood poverty or affluence would be reflected in the brain's development. In many ways, the findings complement the long-standing research into the income-achievement gap.

Yet this work also hints at a special role for neuroscience, beyond descriptive imaging. Monitoring the progress of a particular approach with EEG, as well as behavioral measures, for instance, can offer a fast and revealing indicator of its strengths or failings. Furthermore, the nature of neural differences associated with SES is instructive. If longitudinal evidence supports the idea that more rapid cortical thinning occurs in children raised in poverty, then developing strategies to slow such thinning could be helpful.

Ultimately individual children will respond in varied ways to any given intervention. The challenge is to develop personalized solutions that are not overly expensive or time-consuming for educators. Broadly speaking, the most beneficial programs will be intensive (involving multiple, regular sessions or spanning several years), engage a range of skills in diverse ways, and incorporate not only children and educators but also caregivers and the home environment. Best of all would be public policies and societal changes that take aim at child poverty and income inequality.

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds face many challenges, but thanks in part to the remarkable power of neuroplasticity, no one's story is predetermined. Our hope is that the new brain-based findings may inspire and guide solutions to help these kids flourish and thrive.

John D. E. Gabrieli is a professor in the department of brain and cognitive sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is director of the Athinoula A. Martinos Imaging Center at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the Gabrieli Laboratory, both at M.I.T.

Silvia A. Bunge is a professor in the department of psychology and at the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, where she also directs the Building Blocks of Cognition Laboratory.

LIFE OF THE MIND INTERRUPTED: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education

About LIFE OF THE MIND INTERRUPTED:

From IPPY-Gold-winning author Katie Rose Guest Pryal comes a book that tackles mental illness with a “refreshing and raw honesty.”

Early in her career, Katie Pryal learned that being a professor isn’t easy if your brain isn’t quite right.

“I was a junior in college when I finally realized that I was different in a way that my medically inclined parents would call ‘clinical.’”

In these deeply personal, fiery essays, Pryal tells her story of transformation that began the moment she chose to publicly disclose her own mental illness and leave her career in higher education to begin fighting for a better world for people with psychiatric disabilities. The stories she tells are universal: the fear of stigma, the fight for accommodations, and the raw reality of living with mental illness in a world that pushes mental health to the margins.

People carelessly call each other “schizo” and “bipolar.” A colleague is fired for “instability.” Pryal learned that, as a psychiatrically disabled person working in higher education, her very livelihood could be stripped away by the groundless suspicions of others.

But the problem persists beyond academia.

With candor and grace, these essays discuss the disclosure of disabilities, accommodations and accessibility, how to be a good abled friend to a disabled person, the trigger warnings debate, and more. While harrowing at times, Pryal’s story is ultimately one of hope. With this memoir, she aims to make higher education—and all of our society—more humane.

“Pryal writes with a refreshing and raw honesty.” – Booktrib Magazine

“ Life of the Mind Interrupted is personal, political, polemical, and pointed in its vision for transforming higher education to be more inclusive of disabled and mentally ill people. … If you want to understand how higher education is built, and not built, for people with disabilities—especially mental health–related ones—Pryal’s book is for you.” -Book Riot

Praise for LIFE OF THE MIND INTERRUPTED:

“Katie Rose Guest Pryal is one of the foremost writers of disability and higher education we have today.” – Catherine J. Prendergast, author of The Gilded Edge: Two Audacious Women and the Cyanide Love Triangle that Shook America

“These thoughtfully chosen and arranged essays grapple with issues relevant to disabled students and scholars as well as those who would be allies. With a particular focus on mental illness and other forms of invisible disability, Pryal calls on us to do much, much better.” -Kecia Ali, Ph.D., author of Sexual Ethics and Islam: Feminist Reflections on Qur’an, Hadith, and Jurisprudence

“Pryal’s wit and humor shine through even as she tackles harrowing subjects, like living with depression and suicide. She shows us how important it is to make academia, and our world, more accessible for everyone. … This is not a book to miss.” -Kelly J. Baker, award-winning author of Sexism Ed: Essays on Gender and Labor in Higher Education

Book Information:

- Author: Katie Rose Guest Pryal

- Title: Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education

- Publication Date: October 2017

- Page Count: 210

- Paper ISBN: 978-1-947834-05-7, Ebook ISBN: 978-1-947834-06-4

- Distributed by Ingram

- lifeofthemindinterrupted.com

Share this:

Back to Home Page

Self Help, Relationships, Poetry, Photography & much more.

- Relationships

- Photography

Ill Health Begins In The Mind – 3 Ways To Take Care Of Your Mind

Do you believe ill health begins in the mind ?

Are health issues related with mind?

I think, yes. I do believe mind is where the ill health begins. Why? Read this article till the end to know.

Hello Everyone! Finally, I’m writing a new article on my blog. Actually this topic was allotted to me for Verbal Presentation at my English class . I liked the topic & wanted to say more about it. So here i am.

As usual we will go step by step to understand the title of this article.

Table of Contents

What Is The Meaning of Ill Health ?

Meaning of ill health.

Ill health in short is being sick. A person having health issues, minor or major, like Headache, High Blood Pressure, Diabetes, Depression , etc can be said to have an ill health. These all are commonly observed diseases with many people around us.

You might think all of the mentioned diseases originates with physical action, habits, changes,etc.

Diseases Which Begins In The Mind

Before getting to know how an ill health begins in the mind , let’s look at few examples of diseases which originates with mind.

1. Mental Health Diseases

- Depression – A common disease which begins with the mind. In short, depression is a mental health disease in which the person experiences constant sadness, lack of interest in daily activities, loneliness, etc. Depression can cause due to various reasons but it is mainly associated with the mind.

More examples of diseases which begins with mind includes Anxiety, Bipolar Disorder, ADHD, etc.

All of these mental health diseases starts with mind. Be it due Overthinking, Trauma, Fear or Major loss . It always starts in the mind and affects very badly on physical health as well.

Also read: Why So Many Depressed?| How To Deal With It?

2. Addictions

We often say that a person is addicted to consuming Alcohol or Tobacco, etc. But if you observe deeply, that person is actually addicted to the feelings & sensations which are produced when it’s getting consumed.

So, an addict actually craves for that feeling or sensation and the happy brain chemicals. For ex: Dopamine, Endorphin, Oxytocin, etc.

We all are aware about the deadly heath issues faced by such addicts. And we can conclude that such issues are actually originated from mind.