- Personality

Self-Presentation in the Digital World

Do traditional personality theories predict digital behaviour.

Posted August 31, 2021 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- What Is Personality?

- Find a therapist near me

- Personality theories can help explain real-world differences in self-presentation behaviours but they may not apply to online behaviours.

- In the real world, women have higher levels of behavioural inhibition tendencies than men and are more likely to avoid displeasing others.

- Based on this assumption, one would expect women to present themselves less on social media, but women tend to use social media more than men.

Digital technology allows people to construct and vary their self-identity more easily than they can in the real world. This novel digital- personality construction may, or may not, be helpful to that person in the long run, but it is certainly more possible than it is in the real world. Yet how this relates to "personality," as described by traditional personality theories, is not really known. Who will tend to manipulate their personality online, and would traditional personality theories predict these effects? A look at what we do know about gender differences in the real and digital worlds suggests that many aspects of digital behaviour may not conform to the expectations of personality theories developed for the real world.

Half a century ago, Goffman suggested that individuals establish social identities by employing self-presentation tactics and impression management . Self-presentational tactics are techniques for constructing or manipulating others’ impressions of the individual and ultimately help to develop that person’s identity in the eyes of the world. The ways other people react are altered by choosing how to present oneself – that is, self-presentation strategies are used for impression management . Others then uphold, shape, or alter that self-image , depending on how they react to the tactics employed. This implies that self-presentation is a form of social communication, by which people establish, maintain, and alter their social identity.

These self-presentational strategies can be " assertive " or "defensive." 1 Assertive strategies are associated with active control of the person’s self-image; and defensive strategies are associated with protecting a desired identity that is under threat. In the real world, the use of self-presentational tactics has been widely studied and has been found to relate to many behaviours and personalities 2 . Yet, despite the enormous amounts of time spent on social media , the types of self-presentational tactics employed on these platforms have not received a huge amount of study. In fact, social media appears to provide an ideal opportunity for the use of self-presentational tactics, especially assertive strategies aimed at creating an identity in the eyes of others.

Seeking to Experience Different Types of Reward

Social media allows individuals to present themselves in ways that are entirely reliant on their own behaviours – and not on factors largely beyond their ability to instantly control, such as their appearance, gender, etc. That is, the impression that the viewer of the social media post receives is dependent, almost entirely, on how or what another person posts 3,4 . Thus, the digital medium does not present the difficulties for individuals who wish to divorce the newly-presented self from the established self. New personalities or "images" may be difficult to establish in real-world interactions, as others may have known the person beforehand, and their established patterns of interaction. Alternatively, others may not let people get away with "out of character" behaviours, or they may react to their stereotype of the person in front of them, not to their actual behaviours. All of which makes real-life identity construction harder.

Engaging in such impression management may stem from motivations to experience different types of reward 5 . In terms of one personality theory, individuals displaying behavioural approach tendencies (the Behavioural Activation System; BAS) and behavioural inhibition tendencies (the Behavioural Inhibition System; BIS) will differ in terms of self-presentation behaviours. Those with strong BAS seek opportunities to receive or experience reward (approach motivation ); whereas, those with strong BIS attempt to avoid punishment (avoidance motivation). People who need to receive a lot of external praise may actively seek out social interactions and develop a lot of social goals in their lives. Those who are more concerned about not incurring other people’s displeasure may seek to defend against this possibility and tend to withdraw from people. Although this is a well-established view of personality in the real world, it has not received strong attention in terms of digital behaviours.

Real-World Personality Theories May Not Apply Online

One test bed for the application of this theory in the digital domain is predicted gender differences in social media behaviour in relation to self-presentation. Both self-presentation 1 , and BAS and BIS 6 , have been noted to show gender differences. In the real world, women have shown higher levels of BIS than men (at least, to this point in time), although levels of BAS are less clearly differentiated between genders. This view would suggest that, in order to avoid disapproval, women will present themselves less often on social media; and, where they do have a presence, adopt defensive self-presentational strategies.

The first of these hypotheses is demonstrably false – where there are any differences in usage (and there are not that many), women tend to use social media more often than men. What we don’t really know, with any certainty, is how women use social media for self-presentation, and whether this differs from men’s usage. In contrast to the BAS/BIS view of personality, developed for the real world, several studies have suggested that selfie posting can be an assertive, or even aggressive, behaviour for females – used in forming a new personality 3 . In contrast, sometimes selfie posting by males is related to less aggressive, and more defensive, aspects of personality 7 . It may be that women take the opportunity to present very different images of themselves online from their real-world personalities. All of this suggests that theories developed for personality in the real world may not apply online – certainly not in terms of putative gender-related behaviours.

We know that social media allows a new personality to be presented easily, which is not usually seen in real-world interactions, and it may be that real-world gender differences are not repeated in digital contexts. Alternatively, it may suggest that these personality theories are now simply hopelessly anachronistic – based on assumptions that no longer apply. If that were the case, it would certainly rule out any suggestion that such personalities are genetically determined – as we know that structure hasn’t changed dramatically in the last 20 years.

1. Lee, S.J., Quigley, B.M., Nesler, M.S., Corbett, A.B., & Tedeschi, J.T. (1999). Development of a self-presentation tactics scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(4), 701-722.

2. Laghi, F., Pallini, S., & Baiocco, R. (2015). Autopresentazione efficace, tattiche difensive e assertive e caratteristiche di personalità in Adolescenza. Rassegna di Psicologia, 32(3), 65-82.

3. Chua, T.H.H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 190-197.

4. Fox, J., & Rooney, M.C. (2015). The Dark Triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self-presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 161-165.

5. Hermann, A.D., Teutemacher, A.M., & Lehtman, M.J. (2015). Revisiting the unmitigated approach model of narcissism: Replication and extension. Journal of Research in Personality, 55, 41-45.

6. Carver, C.S., & White, T.L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319.

7. Sorokowski, P., Sorokowska, A., Frackowiak, T., Karwowski, M., Rusicka, I., & Oleszkiewicz, A. (2016). Sex differences in online selfie posting behaviors predict histrionic personality scores among men but not women. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 368-373.

Phil Reed, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at Swansea University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

The self presentation theory and how to present your best self

Jump to section

What does self presentation mean?

What are self presentation goals, individual differences and self presentation.

How can you make the most of the self presentation theory at work?

We all want others to see us as confident, competent, and likeable — even if we don’t necessarily feel that way all the time. In fact, we make dozens of decisions every day — whether consciously or unconsciously — to get people to see us as we want to be seen. But is this kind of self presentation dishonest? Shouldn’t we just be ourselves?

Success requires interacting with other people. We can’t control the other side of those interactions. But we can think about how the other person might see us and make choices about what we want to convey.

Self presentation is any behavior or action made with the intention to influence or change how other people see you. Anytime we're trying to get people to think of us a certain way, it's an act of self presentation. Generally speaking, we work to present ourselves as favorably as possible. What that means can vary depending on the situation and the other person.

Although at first glance this may seem disingenuous, we all engage in self-presentation. We want to make sure that we show up in a way that not only makes us look good, but makes us feel good about ourselves.

Early research on self presentation focused on narcissism and sociopathy, and how people might use the impression others have of them to manipulate others for their benefit. However, self presentation and manipulation are distinct. After all, managing the way others see us works for their benefit as well as ours.

Imagine, for example, a friend was complaining to you about a tough time they were having at work . You may want to show up as a compassionate person. However, it also benefits your friend — they feel heard and able to express what is bothering them when you appear to be present, attentive, and considerate of their feelings. In this case, you’d be conscious of projecting a caring image, even if your mind was elsewhere, because you value the relationship and your friend’s experience.

To some extent, every aspect of our lives depends on successful self-presentation. We want our families to feel that we are worthy of attention and love. We present ourselves as studious and responsible to our teachers. We want to seem fun and interesting at a party, and confident at networking events. Even landing a job depends on you convincing the interviewer that you are the best person for the role.

There are three main reasons why people engage in self presentation:

Tangible or social benefits:

In order to achieve the results we want, it often requires that we behave a certain way. In other words, certain behaviors are desirable in certain situations. Matching our behavior to the circumstances can help us connect to others, develop a sense of belonging , and attune to the needs and feelings of others.

Example: Michelle is a new manager . At her first leadership meeting, someone makes a joke that she doesn’t quite get. When everyone else laughs, she smiles, even though she’s not sure why.

By laughing along with the joke, Michelle is trying to fit in and appear “in the know.” Perhaps more importantly, she avoids feeling (or at least appearing) left out, humorless, or revealing that she didn’t get it — which may hurt her confidence and how she interacts with the group in the future.

To facilitate social interaction:

As mentioned, certain circumstances and roles call for certain behaviors. Imagine a defense attorney. Do you think of them a certain way? Do you have expectations for what they do — or don’t — do? If you saw them frantically searching for their car keys, would you feel confident with them defending your case?

If the answer is no, then you have a good idea of why self presentation is critical to social functioning. We’re surprised when people don’t present themselves in a way that we feel is consistent with the demands of their role. Having an understanding of what is expected of you — whether at home, work, or in relationships — may help you succeed by inspiring confidence in others.

Example: Christopher has always been called a “know-it-all.” He reads frequently and across a variety of topics, but gets nervous and tends to talk over people. When attending a networking event, he is uncharacteristically quiet. Even though he would love to speak up, he’s afraid of being seen as someone who “dominates” the conversation.

Identity Construction:

It’s not enough for us to declare who we are or what we want to be — we have to take actions consistent with that identity. In many cases, we also have to get others to buy into this image of ourselves as well. Whether it’s a personality trait or a promotion, it can be said that we’re not who we think we are, but who others see.

Example: Jordan is interested in moving to a client-facing role. However, in their last performance review, their manager commented that Jordan seemed “more comfortable working independently.”

Declaring themselves a “people person” won’t make Jordan’s manager see them any differently. In order to gain their manager’s confidence, Jordan will have to show up as someone who can comfortably engage with clients and thrive in their new role.

We may also use self presentation to reinforce a desired identity for ourselves. If we want to accomplish something, make a change, or learn a new skill , making it public is a powerful strategy. There's a reason why people who share their goals are more likely to be successful. The positive pressure can help us stay accountable to our commitments in a way that would be hard to accomplish alone.

Example: Fatima wants to run a 5K. She’s signed up for a couple before, but her perfectionist tendencies lead her to skip race day because she feels she hasn’t trained enough. However, when her friend asks her to run a 5K with her, she shows up without a second thought.

In Fatima’s case, the positive pressure — along with the desire to serve a more important value (friendship) — makes showing up easy.

Because we spend so much time with other people (and our success largely depends on what they think of us), we all curate our appearance in one way or another. However, we don’t all desire to have people see us in the same way or to achieve the same goals. Our experiences and outcomes may vary based on a variety of factors.

One important factor is our level of self-monitoring when we interact with others. Some people are particularly concerned about creating a good impression, while others are uninterested. This can vary not only in individuals, but by circumstances. A person may feel very confident at work , but nervous about making a good impression on a first date.

Another factor is self-consciousness — that is, how aware people are of themselves in a given circumstance. People that score high on scales of public self-consciousness are aware of how they come across socially. This tends to make it easier for them to align their behavior with the perception that they want others to have of them.

Finally, it's not enough to simply want other people to see you differently. In order to successfully change how other people perceive you, need to have three main skills:

1. Perception and empathy

Successful self-presentation depends on being able to correctly perceive how people are feeling , what's important to them, and which traits you need to project in order to achieve your intended outcomes.

2. Motivation

If we don’t have a compelling reason to change the perception that others have of us, we are not likely to try to change our behavior. Your desire for a particular outcome, whether it's social or material, creates a sense of urgency.

3. A matching skill set

You’ve got to be able to walk the talk. Your actions will convince others more than anything you say. In other words, you have to provide evidence that you are the person you say you are. You may run into challenges if you're trying to portray yourself as skilled in an area where you actually lack experience.

How can you make the most of the self presentation theory at work?

At its heart, self presentation requires a high-level of self awareness and empathy. In order to make sure that we're showing up as our best in every circumstance — and with each person — we have to be aware of our own motivation as well as what would make the biggest difference to the person in front of us.

Here are 6 strategies to learn to make the most of the self-presentation theory in your career:

1. Get feedback from people around you

Ask a trusted friend or mentor to share what you can improve. Asking for feedback about specific experiences, like a recent project or presentation, will make their suggestions more relevant and easier to implement.

2. Study people who have been successful in your role

Look at how they interact with other people. How do you perceive them? Have they had to cultivate particular skills or ways of interacting with others that may not have come easily to them?

3. Be yourself

Look for areas where you naturally excel and stand out. If you feel comfortable, confident, and happy, you’ll have an easier time projecting that to others. It’s much harder to present yourself as confident when you’re uncomfortable.

4. Be aware that you may mess up

As you work to master new skills and ways of interacting with others, keep asking for feedback . Talk to your manager, team, or a trusted friend about how you came across. If you sense that you’ve missed the mark, address it candidly. People will understand, and you’ll learn more quickly.

Try saying, “I hope that didn’t come across as _______. I want you to know that…”

5. Work with a coach

Coaches are skilled in interpersonal communication and committed to your success. Roleplay conversations to see how they land, and practice what you’ll say and do in upcoming encounters. Over time, a coach will also begin to know you well enough to notice patterns and suggest areas for improvement.

6. The identity is in the details

Don’t forget about the other aspects of your presentation. Take a moment to visualize yourself being the way that you want to be seen. Are there certain details that would make you feel more like that person? Getting organized, refreshing your wardrobe, rewriting your resume, and even cleaning your home office can all serve as powerful affirmations of your next-level self.

Self presentation is defined as the way we try to control how others see us, but it’s just as much about how we see ourselves. It is a skill to achieve a level of comfort with who we are and feel confident to choose how we self-present. Consciously working to make sure others get to see the very best of you is a wonderful way to develop into the person you want to be.

Transform your life

Make meaningful changes and become the best version of yourself. BetterUp's professional Coaches are here to support your personal growth journey.

Allaya Cooks-Campbell

With over 15 years of content experience, Allaya Cooks Campbell has written for outlets such as ScaryMommy, HRzone, and HuffPost. She holds a B.A. in Psychology and is a certified yoga instructor as well as a certified Integrative Wellness & Life Coach. Allaya is passionate about whole-person wellness, yoga, and mental health.

Impression management: Developing your self-presentation skills

How to make a presentation interactive and exciting, 6 presentation skills and how to improve them, how to give a good presentation that captivates any audience, what is self-preservation 5 skills for achieving it, how self-knowledge builds success: self-awareness in the workplace, 8 clever hooks for presentations (with tips), self-management skills for a messy world, developing psychological flexibility, similar articles, how self-compassion strengthens resilience, what is self-efficacy definition, examples, and 7 ways to improve it, what is self-awareness and how to develop it, how to not be nervous for a presentation — 13 tips that work (really), what i didn't know before working with a coach: the power of reflection, self-advocacy: improve your life by speaking up, building resilience part 6: what is self-efficacy, why learning from failure is your key to success, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Online self-presentation strategies and fulfillment of psychological needs of chinese sojourners in the united states.

- 1 School of Overseas Education, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2 Business School, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

This study statistically analyzed survey data to examine the relationship between fulfillment of psychological needs of 223 Chinese sojourners in the United States and their online self-presentation strategies on Chinese and American social media. The results showed that the combined use of proactive and defensive self-presentation strategies on Chinese social media instead of American social media were more effective to fulfill the sojourners’ need for autonomy. Moreover, presentation strategies that helped to meet the sojourners’ need for relatedness were significantly different between Chinese and American social media. Specifically, a proactive strategy was more effective to meet sojourners’ need for relatedness on Chinese social media, while a defensive strategy was more effective to fulfill their need for relatedness on American social media.

Introduction

Self-presentation is the core concept of American sociologist Irving Goffman’s Dramaturgy . As an individual’s role-playing behavior of self-expression in interpersonal interaction, self-presentation provides an impetus for self-promotion in real life ( Goffman, 1959 ). Western social psychologists have tested and revised the Goffman’s theory ( Jones and Nisbett, 1971 ), and the impression management theory (IMT) has been developed, which suggests that people apply a series of strategies (such as modification, concealment, and decoration) to control others’ perception of themselves as impression decoration or self-presentation.

With social media widely involved in people’s daily lives, there have appeared an increasing number of studies that are based on the theories of Dramaturgy and the self-determination theory (SDT), analyzing the relationship between online self-presentation behavior and the fulfillment of psychological needs. Online self-presentation is an important part of online social interaction and is influenced by multiple factors such as individual psychology, social context, and social culture. For instance, self-enhancers will selectively choose only positive life events and favorable personal information to share with their social network friends, but other people may entail presenting both positive and negative aspects of the self on social media to reveal their true feelings ( Lee-Won et al., 2014 ; Bareket-Bojmel et al., 2016 ).

In terms of self-presentation and need for relatedness, for example, Deters and Mehl (2013) pointed out that the active self-presentation on Facebook can reduce loneliness; Pittman and Reich (2016) found that compared with text-based platforms, social media users’ presentation on image-based platforms significantly reduced loneliness due to their enhanced intimacy with others. In terms of self-presentation and the need for autonomy, since a more multidimensional space for self-determined behaviors is provided in social media ( Reinecke et al., 2014 ), people can freely present their true selves without being affected by the outside world, therefore meeting their needs for autonomy ( Chen, 2019 ). For immigrants or sojourners, studies have found that they are more inclined to fulfill their autonomy needs through self-presentation on ethnic social media ( Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007 ; Lim and Pham, 2016 ; Pang, 2018 ; Hofhuis et al., 2019 ). Additionally, proactive self-presentation strategies were found to be positively related to the maintenance of psychological well-being ( Swickert et al., 2002 ; Kim and Lee, 2011 ; Ellison et al., 2014 ; Stieger, 2019 ), and in order to obtain more social support, people need to keep a balance between the use of selective and authentic presentational strategies ( Bayer et al., 2020 ).

The psychological effect of online self-presentation has attracted more and more academic attention. However, these studies still remain inconclusive as how people fulfill their psychological needs by means of online self-presentation behavior in intercultural contexts. Specifically, most studies of sojourners are conducted in unitary contexts, either in sojourners’ ethnic social media environments or the social media of the host country, ignoring sojourners’ co-performance in dual-cultural contexts. Moreover, with the growth of the scale of Chinese sojourners, an increasing number of studies have been aimed at them, yet most have focused more on acculturation problems than online self-presentation behaviors. However, online self-presentation has gradually become an important behavior mechanism for Chinese sojourners’ acculturation and communication under the increasing influence of social media. Therefore, it is necessary to fill in the gaps in current research has left and to investigate the logical relationship between the online self-presentation and fulfillment of psychological need of Chinese sojourners in China and America’s dual-cultural contexts.

As important members of intercultural communication groups, Chinese sojourners in the United States are in the dual-cultural contexts of Chinese and American social media, thus they are ideal research participants. In view of this, this study focuses on the following questions:

RQ 1: Do Chinese sojourners mainly use Chinese or American social media to fulfill their psychological needs?

RQ 2: What kinds of presentation strategies are more effective in fulfilling Chinese sojourners’ psychological needs in dual-cultural contexts?

The purpose of this research is to study the logical relationship between online self-presentation strategies and the fulfillment of psychological needs (for autonomy and relatedness) of Chinese sojourners in the context of American and Chinese cultures and to further understand the characteristics of the psychological effects of Chinese sojourners’ online self-presentation behavior in intercultural contexts, so as to provide a new and resourceful way of thinking about maintaining Chinese sojourners’ mental health, as well as helping them to acculturate and communicate more effectively.

Participants and Procedure

This study focused on Chinese sojourners, who are mainly distributed on the east and west coasts of the United States. However, due to factors, such as the uniqueness of sojourners’ identity and their mobility, it is not possible to verify the official statistics on the population data. Therefore, the sampling method used in this study was a nonrandom sampling, and we were utilizing snowball sampling approach to recruit participants.

To be specific, our study initially chose Chinese overseas students, visiting scholars (college teachers and Confucius Institute teachers), and Chinese with a working visa in Washington state in the northwest of the United States as the main sample groups. We applied “Wenjuanxing” (wjx.cn), the most commonly used online questionnaire platform, to send out our questionnaires to people we knew in these three sample groups. We asked them to fill out the questionnaires and distributed the questionnaire link to their interpersonal social networks, including the WeChat groups of Chinese students studying in the United States and visiting scholars in American Colleges and universities, as well as online communities of local American Chinese. Following these procedures, we collected a snowballing sample of 300 questionnaires with responses.

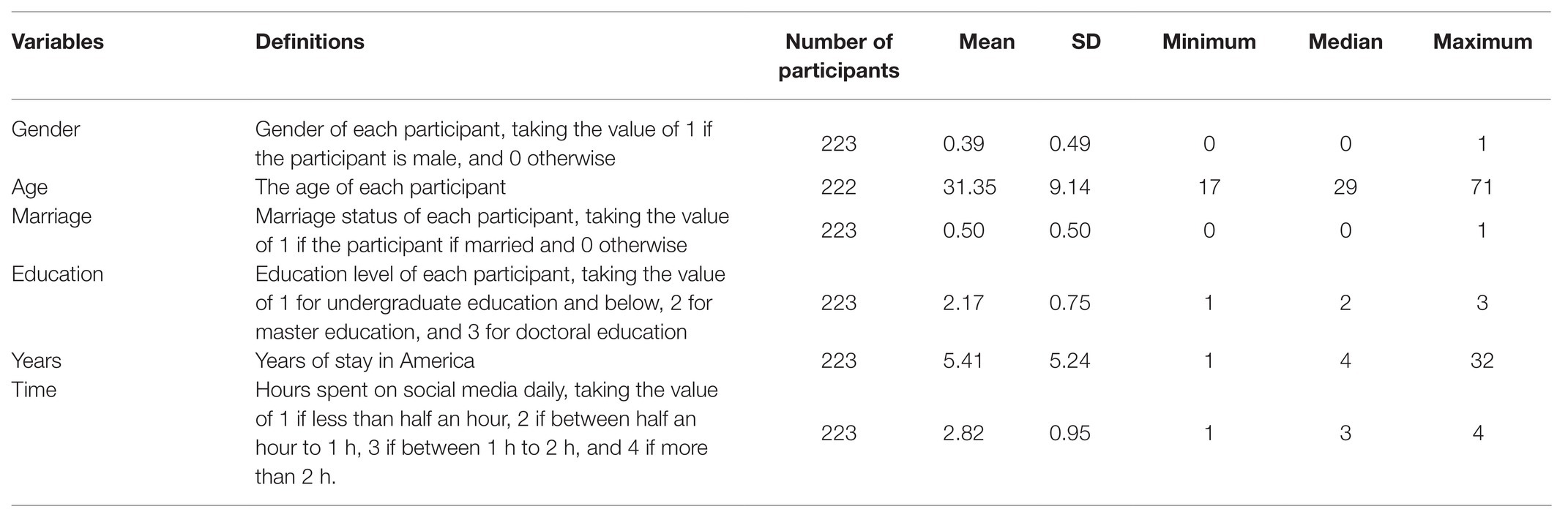

In order to further reduce the error, the study carefully checked the responses to the 300 questionnaires; 29 questionnaires that did not indicate the use of both Chinese and American social media were excluded from the total sample, leaving 223 questionnaires as statistically valid. According to the data analysis of the demographic characteristics of the sample (see Table 1 ), a total of 135 female and 88 male sojourners participated in the survey. In terms of age, they ranged from 17 to 60 years of age, and the number of people aged between 21 and 30 was the biggest (120 people); there were 211 sojourners who had lived in the United States for 1 year or more.

Table 1 . Descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics of participants.

Finally, based on the data collected, this study performed a descriptive statistical analysis of self-presentation strategies and psychological needs on Chinese and American social media followed by a regression analysis of the two main variables.

Self-presentation strategies and the fulfillment of psychological needs were two major variables in our questionnaire, and both of them were measured with multiple items that were modified from established scales ( Lee et al., 1999 ; Partala, 2011 ; Chen, 2019 ).

Self-Presentation Strategies

Although there were differences in the classification of self-presentation strategies in the field of psychology at the microlevel, the self-presentation strategies could still be divided into two categories: proactive strategies and defensive strategies ( Goffman, 1959 ; Arkin et al., 1980 ; Tedeschi and Melburg, 1984 ; Fiske and Taylor, 1991 ). Based on this dichotomy and the self-presentation tactic scale developed by Lee et al. (1999) , as well as our empirical observation of Chinese sojourners’ online self-presentation behavior in the United States, this paper specified six presentational tactics, namely “posting selected photos,” “expressing humorous and close content,” and “displaying discipline” for proactive strategies, aimed at actively shaping and maintaining an ideal image and, “expressing controlled feelings,” “self-taunting,” and “reporting only good news” for defensive strategies, aimed at preventing others from depreciating or belittling one’s image. These tactics were measured with six statements; responses were captured on a 5-point Likert scale from “1-never use” to “5-use almost every time.”

Psychological Need Fulfillment

Our measure of the fulfillment of need for autonomy was based on scale for the satisfaction of psychological needs on social networking sites developed by Partala (2011) and was specified with the statements “I feel that my choices express my ‘true self’” and “I have a say in what happens and can voice my opinion.” To measure the fulfillment of need for relatedness, we adapted existing measures of need satisfaction ( La Guardia et al., 2000 ; Ryan et al., 2006 ; Partala, 2011 ) to the intercultural context on social media. Specifically, sojourners mainly maintained and developed three types of relationships in the intercultural context: the relationship with relatives and friends in their home country, the relationship with co-nationals or immigrants of the same cultural background, and the relationship with the locals in the host country ( Lim and Pham, 2016 ; Hofhuis et al., 2019 ; Liu and Kramer, 2019 ). Based on the existing research, this study divided the needs for relatedness of Chinese sojourners in the United States into three categories: first, relational need with domestic relatives and friends, which was stated as “I feel close and connected with my domestic relatives and friends”; second, relational need with Chinese Americans, which was stated as “I feel a sense of contact with Chinese Americans”; third, relational need with Americans, which was stated as “I feel a sense of contact with Americans.” Responses were captured on a 5-point Likert scale from “1-totally disagree” to “5-totally agree.”

In order to understand the basic identity characteristics of Chinese sojourners, this study designed demographic characteristics variables, including “gender,” “age,” “marital status,” “education level,” “time to the United States,” “daily social media use time.” On this basis, this study designed a set of scale to evaluate the online self-presentation behavior of Chinese sojourners in the United States from the overall level. The scale consists of three parts: demographic information, self-presentation strategy, and psychological need fulfillment. Responses were captured with 5-point Likert scales, except for demographic characteristics. Since WeChat and Facebook were the two social media that are most frequently used according to our preliminary study on Chinese sojourners’ general use of social media, this paper chose WeChat and Facebook as the main platforms to observe and analyze the self-presentation behavior of the sojourners. On the basis of quantitative research, this study conducted interviews with 18 Chinese sojourners from all the respondents to understand the logical relationship between self-presentation strategies and fulfillment of psychological needs on Chinese and American social media.

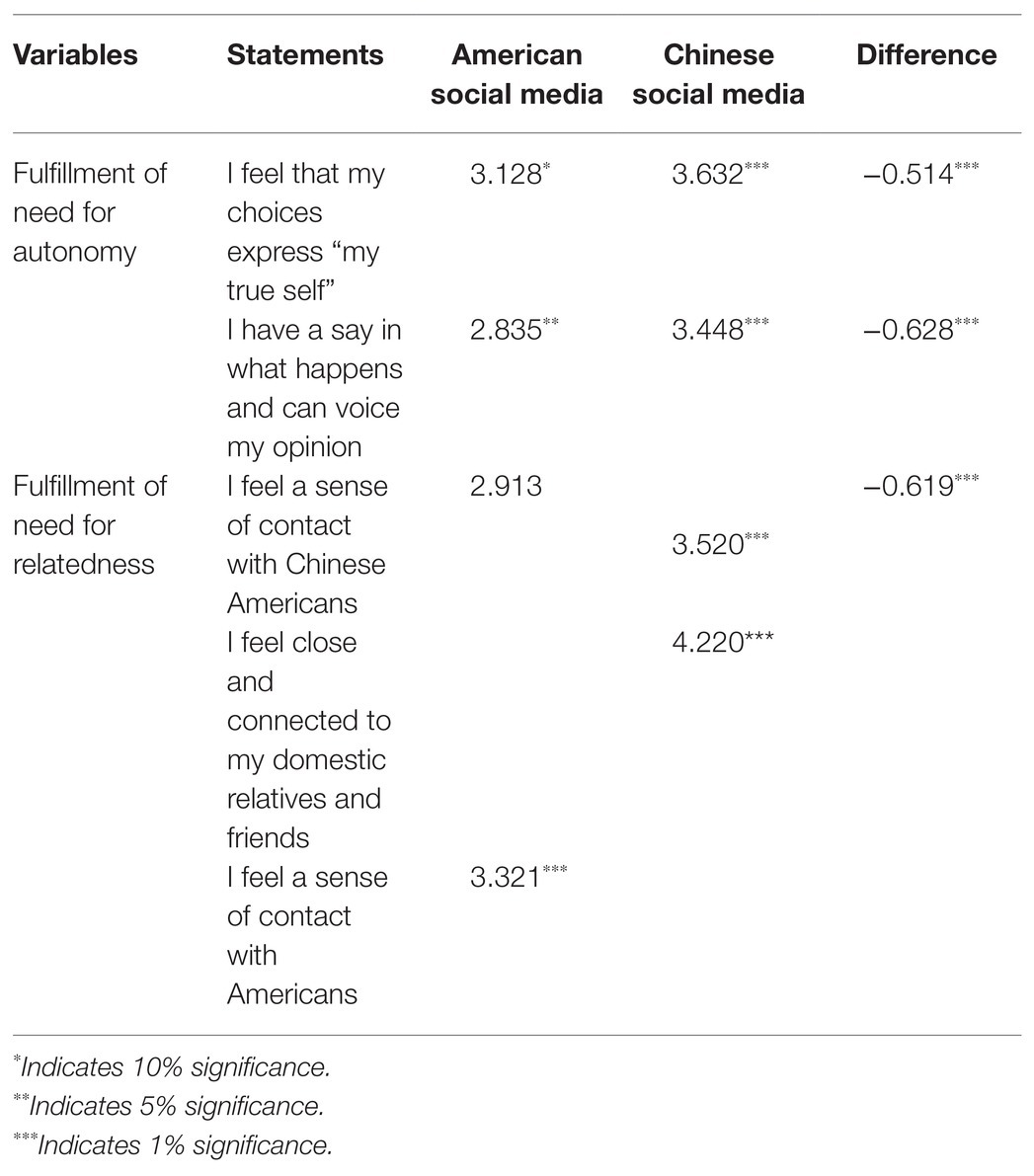

RQ 1: Do Chinese Sojourners Mainly Use Chinese or American Social Media to Fulfill Their Psychological Needs?

In order to answer this question, this study conducted a descriptive statistical analysis of the questionnaire data, and the results are shown in Table 2 . We first calculated the average score of the respondents’ psychological needs on social media in China and the United States and then used a t -test to compare the difference of the average scores between Chinese and American social media. As for “the fulfillment of the need for autonomy,” the results showed that the average score of Chinese social media was significantly higher than that of American social media at the level of 1%, indicating that the self-presentation behavior of Chinese social media was more effective for the fulfillment of Chinese sojourners’ need for autonomy.

Table 2 . Fulfillment of the needs for autonomy and relatedness in American and Chinese social media.

In terms of “the fulfillment of the need for relatedness,” the average score of American social media was significantly higher than 3 (a score of 3 represents neutrality), indicating that the development of a relationship with Americans through online self-presentation was significant. In Chinese social media, the average score of “maintaining the relationship with domestic relatives and friends” was significantly higher than 3 at the level of 1%, indicating that Chinese social media had a significant impact on the relationship with family and friends back in China. As for maintaining a relationship with American Chinese, the average score of Chinese social media was significantly higher than that of American social media at the level of 1%, suggesting that the Chinese social media could promote the relationship between sojourners and American Chinese more effectively than American social media.

RQ 2: What Kinds of Presentation Strategies Are More Effective to Fulfill Chinese Sojourners’ Psychological Needs in the Dual-Cultural Contexts?

In order to test the relationship between online self-presentation strategies and the fulfillment of psychological needs, this study further applied a regression analysis after controlling the demographic characteristics of sojourners such as gender, age, marital status, education level, years in the United States, and time spent on social media. The specific regression model was as follows:

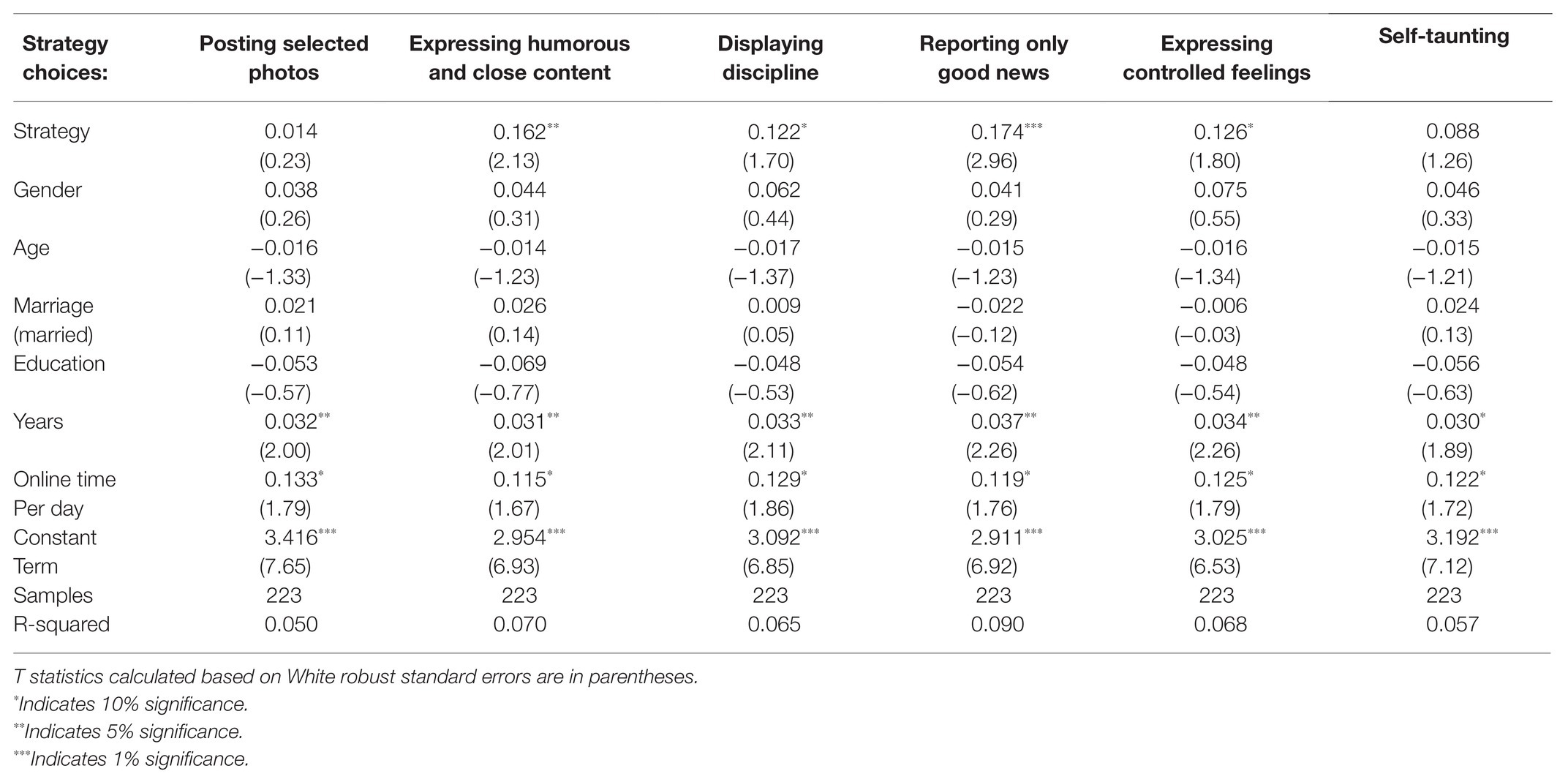

Among them, the dependent variable Effect represented the fulfillment of psychological needs (autonomy and relatedness) brought by the online self-presentation behaviors of the Chinese sojourners, and the independent variable Strategy represented the self-presentation strategies including “posting selected photos,” “expressing humorous and close content,” “displaying discipline,” “reporting only good news,” “expressing controlled feelings,” and “self-taunting.” The control variables included the sojourners’ gender ( Gender ), age ( Age ), marital status ( Marriage ), education level ( Education ), length of stay in America ( Years ), and hours spent on social media daily ( Time ). Table 1 illustrates the descriptive statistics for the above demographic characteristics of participants in our regression.

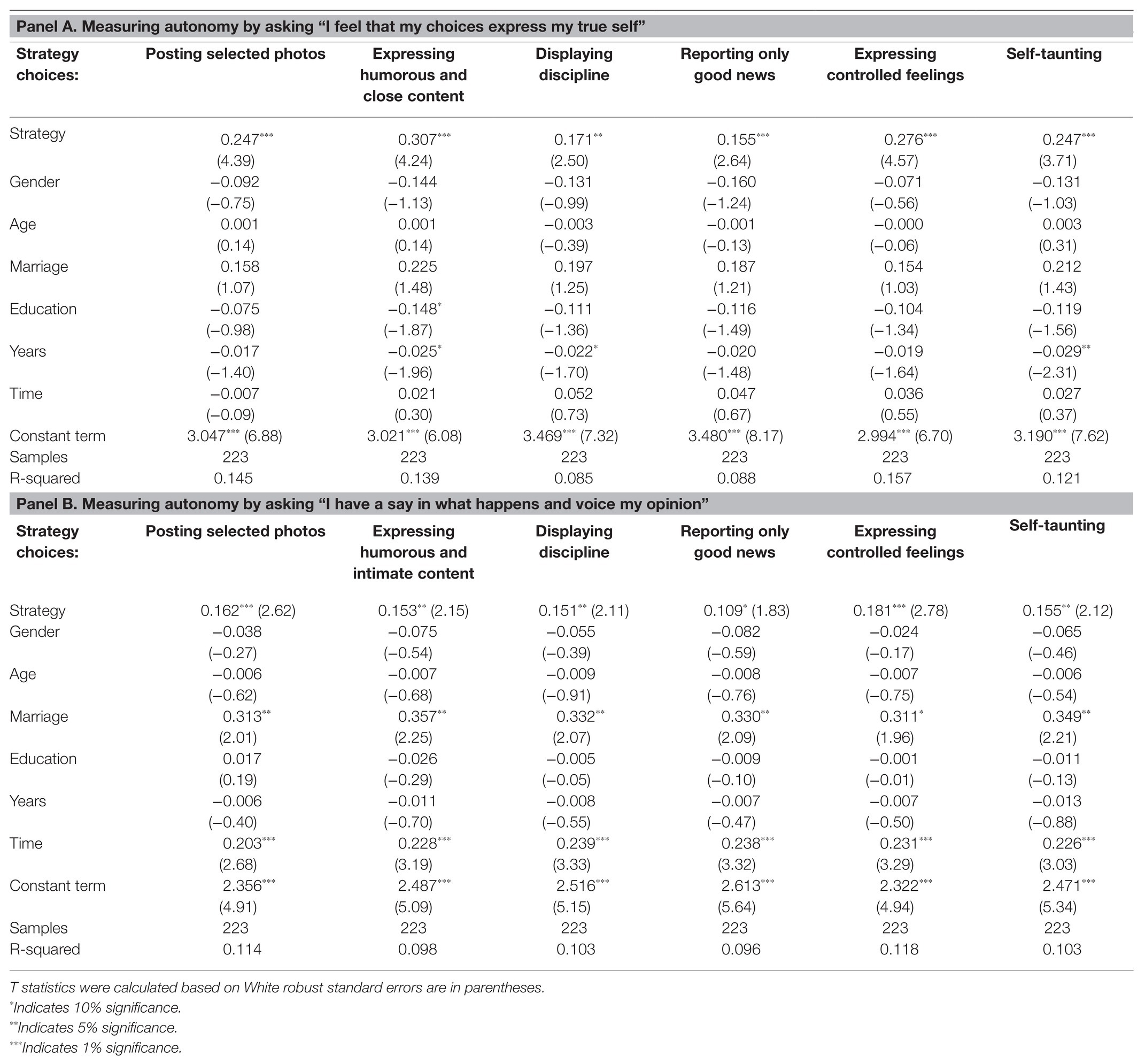

We have found in Table 2 that Chinese sojourners’ self-presentation behavior on Chinese social media is more effective in fulfilling their need for autonomy. Therefore, we conducted a regression analysis on the relationship between the presentation strategies adopted by the sojourners on Chinese social media and their need for autonomy (see Table 3 for the research results). It was found that all six presentation strategies can significantly promote the fulfillment of the sojourners’ need for autonomy but that there are differences in the effectiveness of these strategies. Specifically, for the autonomy dimension of “expressing one’s true self,” the strategy with the most obvious effect was the proactive strategy “expressing humorous and close content,” while for the autonomy dimension of “voicing one’s opinion,” the strategy with the most obvious effect was the defensive strategy “expressing one’s controlled feelings.” It could be seen that in the context of social media in China, the combination of proactive and defensive strategies played a more positive role in meeting the need for autonomy. Through offline interviews, the results of quantitative analysis were further supported. Interviewees have said that the presentation strategy of “expressing humorous and close content” played an important role in arousing emotional resonance and expressing one’s true self; while for important events in personal or social life, using the defensive strategy of “expressing one’s controlled feelings” was more helpful for sojourners to voice his or her opinion in an objective stand and build an intercultural image with the ability of reflection.

Table 3 . The effect of different self-presentation strategies on the fulfillment of the need for autonomy in Chinese social media.

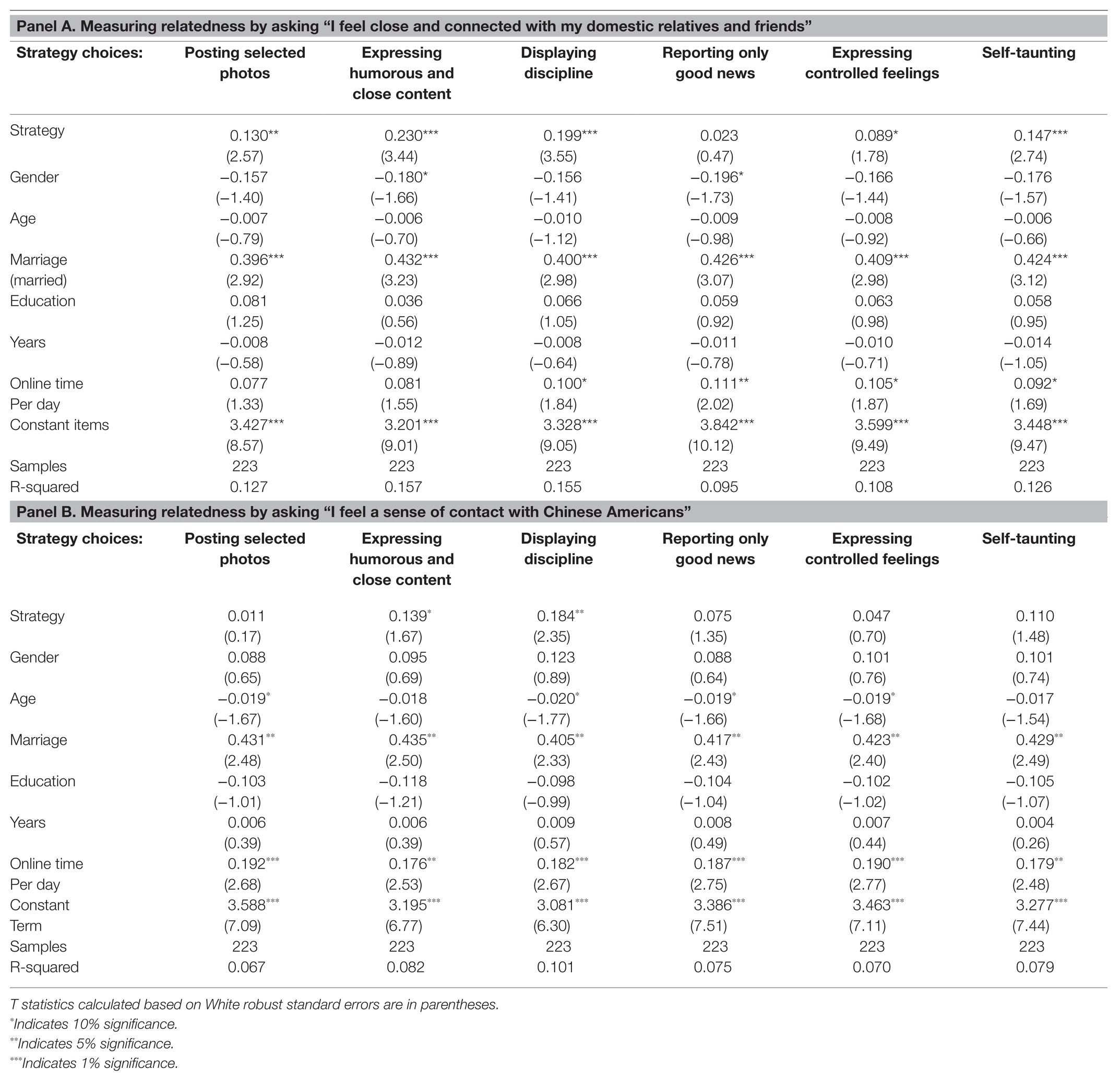

The empirical analysis in this paper had shown that the self-presentation behavior was effective in fulfilling sojourners’ need for relatedness in both Chinese and American social media. In order to investigate the differences between presentation strategies used in Chinese and American social media, this paper then conducted a regression analysis of the two platforms’ presentation strategies and fulfillment of sojourners’ needs for relatedness.

For Chinese social media, panel A in Table 4 shows that except “reporting only good news,” the other five presentation strategies have positive effects on maintaining the relationship between sojourners and their domestic relatives and friends. However, there were differences in the effectiveness of these strategies in fulfilling such a need, specifically, the proactive strategies of “expressing humorous and close content” and “displaying discipline” were comparatively more effective in fulfilling sojourners’ need to maintain domestic relationships. Similarly, the results in panel B shows that only the two proactive strategies of “displaying discipline” and “expressing humorous and close content” played an active role in maintaining the relationship between sojourners and Chinese Americans. It could be seen that the self-presentation on Chinese social media, whether to meet the relational needs with domestic relatives and friends or with Chinese Americans, was more effective by adopting proactive presentation strategies. The results of offline interviews further supported the quantitative research results. Interviewees said that “expressing humorous and close content” played an important role in maintaining the relationship with domestic relatives and friends, and this strategy could help them to narrow down the emotional distance with their relatives and friends back in China. At the same time, interviewees often expressed humorous and close content in the WeChat group of “Fellow Countrymen Association,” so as to promote the emotional connection with Chinese Americans. Also, interviewees considered as it necessary to present their “principled” side on Chinese social media and pointed out that “forwarding + commenting” was the most effective way to show the principle. Interviewees said that the strategy of “displaying principle” could help them to shape their self-image of self-discipline, self-reliance, and maintenance of their own cultural identity, thus strengthening the connection with their domestic relatives, friends, and Chinese Americans.

Table 4 . The effect of different self-presentation strategies on the fulfillment of the need for relatedness in Chinese social media.

For American social media, the statistical results of Table 5 shows that four presentation strategies played effective roles in developing the relationship between sojourners and Americans, but that there were differences in their degree of effectiveness. According to a ranking of their effect, the top three presentation strategies included two defensive ones, which were “reporting only good news” and “expressing controlled feelings,” and “reporting only good news” served as the most effective strategy to fulfill sojourners’ need for intercultural relatedness. This result was different from the situation on Chinese social media. That was, on Chinese social media, sojourners mainly adopted a proactive strategy to fulfill their need for relatedness with domestic relatives, friends, and Chinese Americans, while on American social media, sojourners preferred to use a defensive strategy to promote the fulfillment of their needs for relatedness. In the offline interview, the interviewees said that the strategy of “reporting only good news” could build a positive impression, activate dialog more quickly, and protect personal privacy. Such strategy conformed to the communication code of conduct on American social media, thus laying a good foundation for the establishment and maintenance of the interpersonal relations between Chinese sojourners and Americans. Additionally, the cultural context of American social media is obviously different from that of Chinese social media. In order to avoid possible cultural misunderstanding or even conflict, the interviewees said that they would control the limit of emotional expression on American social media. The results of interview analysis supported the quantitative research.

Table 5 . The effect of different self-presentation strategies on the fulfillment of the need for relatedness in American social media.

Our study recruited 223 Chinese sojourners in the United States as research participants, investigated, and analyzed the relationship between their self-presentation behavior and the fulfillment of their psychological needs (autonomy and relatedness) on Chinese and American social media.

The study shows that, compared with American social media, the self-presentation behavior on Chinese social media can more significantly promote the fulfillment of sojourners’ need for autonomy. This paper holds that the main reason for this difference may be cultural context, that is, Chinese social media are more conducive to the realization of the sojourners’ autonomy. After all, there are cultural values and relational networks that the sojourners are familiar and identified with. The higher the degree of identification and integration with the cultural context, the higher the degree of autonomy of individual actions ( Chirkov et al., 2003 ). In contrast, the cultural context of social media in the United States is relatively unfamiliar and features more heterogeneity. According to SDT, heterogeneity is a reverse force that hinders the realization of autonomy ( Deci and Ryan, 1985 , 2000 ); therefore, compared with the heterogeneous American social media, self-presentation behavior on Chinese social media is more active in promoting the satisfaction of the need for autonomy. Additionally, the results show that Chinese social media play a more active role in maintaining the relationship between sojourners and Chinese Americans than American social media. This result shows that the relatively homogeneous cultural context of Chinese social media provides sufficient emotional and spiritual exchange opportunities, as well as mutual social assistance space for sojourners and Chinese Americans, which is more recognized and adapted by both sides, thus helping to meet the fulfillment of their need for relatedness in the common cultural context ( Lim and Pham, 2016 ; Xiao et al., 2018 ).

This study found that on Chinese social media, the comprehensive use of proactive and defensive presentation strategies helps to meet sojourners’ need for autonomy, which to a certain extent reflects the expediency of Chinese self-presentation behavior ( Zhai, 2017 , p. 56). That is, even when “expressing one’s true self,” sojourners still pay attention to what to say and what not to say, what kind of emotion needs to be expressed and what need not be, which generally reflects that sojourners are striking a balance between sense and sensibility on Chinese social media. At the same time, the sojourners not only distribute and adjust their presentation content but also pay attention to “voicing one’s opinion” through different forms of media, and Chinese social media is technically providing the sojourners with different kinds of effective ways to present ideal self-images and realize autonomous expression.

There are significant differences between Chinese and American social media in the use of self-presentation strategies that help to fulfill sojourners’ need for relatedness. On Chinese social media, a proactive strategy is more effective in meeting sojourners’ need for relatedness, while on American social media, sojourners tend to use a defensive strategy to promote the fulfillment of their need for relatedness. This paper argues that the differences in the connotation of the relationship between Chinese and American cultures affect sojourners’ tendencies when choosing presentation strategies. In the Chinese context, relationship ( guanxi ) is “a kind of social force exerted by family chain and social structure prior to individual existence” ( Zhai, 2011 , p. 187). Individuals must actively maintain important relationships for settling down and gain identification from the social environment at the same time. For Chinese sojourners, their intercultural identity and experiences more intangibly promoting them to adopt proactive presentation strategies on Chinese social media to meet their need for relatedness, because on the one hand, they can help them to consolidate different domestic relationships, and on the other hand, the maintenance of domestic relationships can provide them emotional attachment and a sense of belonging, which help them to alleviate various negative emotions caused by cultural maladjustment.

Compared with the guanxi in China, interpersonal relationships in the American context are clear “role relationships” and have a distinct public-private boundary ( Chu, 1979 ). In the classic social interaction mode with an American-style interpersonal relationship at the core, the means of maintaining and developing the relationship presents very obvious characteristics of instrumental rationality ( Altman and Taylor, 1973 ). Most of the Chinese sojourners who participated in this study came to the United States between 1 and 2 years prior. With the purpose of achieving their specific goals of sojourning in the United States, they needed to develop intercultural interpersonal relationships with local Americans as much as possible; on the other hand, the context of American social media is full of strangeness, heterogeneity, and uncertainty, which made the sojourners more cautious and more aware of all kinds of intercultural communication barriers. Therefore, based on the identification and understanding of the characteristics of relationships in an American context, Chinese sojourners are more likely to adopt a defensive strategy as the main and proactive strategy as the auxiliary to achieve the purpose of fulfilling their need for intercultural relatedness on American social media.

Unlike most previous studies that mainly analyzed the relationship between self-presentation strategies and psychological need fulfillment in a single cultural context, this paper provides empirical evidence for the first time on how self-presentation strategies affect fulfillment of psychological needs in the contexts of dual culture (host and home culture), which provides new inspiration for the study of online self-presentation behavior of sojourners, an important intercultural communication group.

Future Directions

Future research might include empirical research on the relationship between online self-presentation strategies and the satisfaction of Chinese sojourners’ need for competence ( Deci and Ryan, 2000 ) in the United States. In addition, future research might examine how the psychological effects of Chinese sojourners’ online self-presentation behavior affect their offline intercultural adaptation and communication, as well as the acquisition of social capital; such research should be strictly followed by an intercultural analysis of the causes of the general impact. On the basis of empirical research, future research might discuss ways to positively promote the intercultural adaptation and communication of international sojourners, and help sojourners to maintain their psychological well-being in host countries over the long run.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study on human participants, which was in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

TY contributed to research design, theoretical discussion, and manuscript writing. QY contributed to data processing and empirical analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Social Sciences General Project of China’s Sichuan Province (SC19B067), the research fund from Sichuan University (2018hhs-24, SCU-SOE-ZY-202008, SKSYL201822, and SCU-BS-PY-202003), and the Youth Fund Project for the Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (18YJC790204).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Sichuan University and all the funding resources that helped us in the completion of this research.

Altman, I., and Taylor, D. A. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Google Scholar

Arkin, R. M., Appleman, A. J., and Burger, J. M. (1980). Social anxiety, self-presentation, and the self-serving bias in causal attribution. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 38, 23–25. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.38.1.23

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bareket-Bojmel, L., Moran, S., and Shahar, G. (2016). Strategic self-presentation on Facebook: personal motives and audience response to online behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.033

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bayer, J. B., Triệu, P., and Ellison, N. B. (2020). Social media elements, ecologies, and effects. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 71, 471–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050944

Chen, A. (2019). From attachment to addiction: the mediating role of need satisfaction on social networking sites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 98, 80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.034.

Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., and Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: a self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 97–110. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.97

Chu, G. (1979). “Communication and cultural change in China: a conceptual framework” in Moving a mountain: Cultural change in China. eds. G. Chu and F. L. K. Hsu (Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii).

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

Deters, F. G., and Mehl, M. R. (2013). Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 4, 579–586. doi: 10.1177/1948550612469233

Ellison, N. B., Gray, R., Lampe, C., and Fiore, A. T. (2014). Social capital and resource requests on Facebook. New Media Soc. 16, 1104–1121. doi: 10.1177/1461444814543998

Fiske, S. T., and Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition: From brains to culture. Sage Publishing.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: A Division of Random House, Inc.

Hofhuis, J., Hanke, K., and Rutten, T. (2019). Social network sites and acculturation of international sojourners in the Netherlands: the mediating role of psychological alienation and online social support. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 69:120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.02.002

Jones, E. E., and Nisbett, R. E. (1971). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. New York: General Learning Press.

Kim, J., and Lee, J. -E. R. (2011). The Facebook paths to happiness: effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 14, 359–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0374

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: a self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 367–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367

Lee, S., Quigley, B. M., Nesler, M. S., Corbett, A. B., and Tedeschi, J. T. (1999). Development of a self-presentation tactics scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 26, 701–722. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00178-0

Lee-Won, R. J., Shim, M., Joo, Y. K., and Park, S. G. (2014). Who puts the best “face” forward on Facebook?: positive self-presentation in online social networking and the role of self-consciousness, actual-to-total Friends ratio, and culture. Comput. Hum. Behav. 39, 413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.08.007

Lim, S. S., and Pham, B. (2016). “If you are a foreigner in a foreign country, you stick together”: technologically mediated communication and acculturation of migrant students. New Media Soc. 18, 2171–2188. doi: 10.1177/1461444816655612

Liu, Y., and Kramer, E. (2019). Cultural value discrepancies, strategic positioning and integrated identity: American migrants’ experiences of being the other in mainland China. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2019.1679226

Mikulincer, M., and Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press.

Pang, H. (2018). Exploring the beneficial effects of social networking site use on Chinese students’ perceptions of social capital and psychological well-being in Germany. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 67, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.08.002

Partala, T. (2011). Psychological needs and virtual worlds: case second life. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 69, 787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2011.07.004

Pittman, M., and Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 3, 155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084.

Reinecke, L., Vorderer, P., and Knop, K. (2014). Entertainment 2.0? The role of intrinsic and extrinsic need satisfaction for the enjoyment of Facebook use. J. Commun. 64, 417–438. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12099.

Ryan, R., Rigby, C., and Przybylski, A. (2006). The motivational pull of video games: a self-determination theory approach. Motiv. Emot. 30, 344–360. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8.

Stieger, S. (2019). Facebook usage and life satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 10:2711. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02711

Swickert, R. J., et al. (2002). Relationships among Internet use, personality, and social support. Comput. Hum. Behav. 18, 437–451. doi: 10.1016/S0747-5632(01)00054-1.

Tedeschi, J. T., and Melburg, V. (1984). “Impression management and influence in the organization” in Research in the sociology of organizations. Vol. 3. eds. S. B. Bacharach and E. J. Lawler (Greenwich, CT: JAI), 31–58.

Xiao, Y., Cauberghe, V., and Hudders, L. (2018). Humor as a double ‐ edged sword in response to crises versus rumors: the effectiveness of humorously framed crisis response messages on social media. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 26, 247–260. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12188

Zhai, X. (2011). The principles of Chinese guanxi: Time-space order, life desire and their changes. Peking University Press.

Zhai, X. (2017). The behavioral logic of Chinese. Beijing: Joint Publishing.

Keywords: self-presentation strategies, fulfillment of need for autonomy, fulfillment of need for relatedness, social media, Chinese sojourners

Citation: Yang T and Ying Q (2021) Online Self-Presentation Strategies and Fulfillment of Psychological Needs of Chinese Sojourners in the United States. Front. Psychol . 11:586204. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586204

Received: 09 October 2020; Accepted: 29 December 2020; Published: 29 January 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Yang and Ying. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qianwei Ying, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Presentation of Self Online

Introduction.

Web users are engaging in computer-mediated self-expression in varying ways. The technology that enables this is developing fast, and how it does so is influenced by many more factors than just the needs of the people it touches. This chapter explores literature about the impact of computer-mediated self-expression on:

- people's everyday lives.

- individual self-expression and exploration.

- interactions and relations with others.

- interactions with and expectations of society and community.

We ground our discussion in established literature about non-digital self-expression and identity from the social sciences. This raises the key theme of individuals desiring control over how others see us, yet wanting to behave in a way that is authentic, or consistent with their internal identities. There is also emphasis on the collaborative and collective nature of identity formation; that is, our self-presentation fluctuates depending on the people we're with, the situation we're in, and norms of the society we're part of. The focus on face-to-face interactions and embodiment leads us to draw contrasts between online and offline experiences, and to look at the substitutes for the body in digital spaces.

The extent to which online and offline identities interact and overlap is hotly debated. Is creating an online identity a chance to reset, to reshape yourself as an ideal? Or are you simply using it to convey true information about what is happening in your daily offline life? Is it a shallow, picture of you, or a forum for deep self-exploration? How does the way one portrays oneself in digital spaces feedback to ones offline self-presentation? We explore these questions in section 3 .

Section 4 examines social media and blog use, including how one's imagined audience affects self-presentation in public, and how context collapse might occur when the actual audience is different to expected. There are several examples of techniques for managing who sees which 'version' of oneself, and the types of 'versions' of self that are commonly seen to be constructed on social media, and with what degree of transparency they are linked together. Most of the longitudinal studies in this space are of teenagers and young people, who have never known a world without social media, and who may incorporate it naturally and seamlessly into their daily practices, thus making it a core part of their identity during formative years. I draw a contrast between the relationship-driven architecture of contemporary social networking sites, and the more personal, customisable blogging platforms which preceded them. Studies of bloggers and blogging communities reveal some different priorities and habits than what is common practice today, and offer insight into how online self-presentation is evolving.

Throughout literature from both social and computer sciences, privacy is a common concern. In section 5 we look further at how tensions between users and the privacy settings of systems they use impact on personal information disclosure. Does self-censorship affect identity formation? How do people weigh up the risks and benefits of exposing themselves online? This is particularly pertinent for future systems development, as more and more people become aware of state surveillance, for-profit data collection, and their diminished rights over their personal data.

Finally we introduce the relatively new Web Science concept of Social Machines in section 6 in order to recapture the circular interdependencies between humans, technologies, and communities. We propose to build on current work of describing and classifying social machines to better account for the individual perspectives of participants.

Ultimately we posit that online is simultaneously a reflection, a distortion, an enhancement, and a diminishment of the offline world. They impact each other in complex ways, particularly with regards to self-presentation and identity formation. The various theories and studies described in this chapter form the basis for which we conduct the investigative and technical work in the remainder of this thesis.

My perspective on this review

I'd like to take a moment to note that whilst reading various studies about young peoples' reactions to and interactions with rapidly evolving digital technologies from the 2000s, it occurred to me that the subject of these studies is in fact my own age group. Some of the results are instinctively familiar to me; I was there, I experienced these things. Some are ridiculous. I don't know how my first-hand experience of growing up with technology (I was born in the same year as the Web, and my parents were early adopters) affects my reading of these studies, or my ability to study others' use of technology, but it is something I ponder.

Performing the self

The obvious place to start when embarking on a discussion about self-presentation is Goffman [ goffman1959 ]. In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life , Goffman posits several, now well-established, theories using drama as a metaphor:

- Everyone is performing. The front-stage of our performance is what we create for others - the audience - to see, so that they may evaluate and interact appropriately with us.

- We also have a back-stage; how we act when there is no audience, or an audience of our team . Our team participate alongside and collude with us on the front-stage.

- Our performances have both conscious and unconscious aspects. That is, we consciously give information about ourselves to others in order to manage their impression of us, but we also unconsciously give off information that others may pick up on and take into account when deciding how to interact with us.

- Both actors and audiences are complicit in maintaining the cohesion of a situation. Performances break down if actors break character, deliberately or accidentally, or if there is a mismatch between parties' definition of the situation.

These theories emphasise the collaborative or social nature of self-presentation, and apply to face-to-face interaction.

Whilst Goffman's dramaturgy refers mostly to body language, a related theory is Brunswik's lens model [ brunswick56 , lens01 ], part of which suggests that individuals infer things about others based on "generated artifacts", or things left behind. In [ bedrooms02 ] this model is used to study how personal spaces (offices and bedrooms) affect observers' assessments of the characteristics of the owner of the space. This study links individuals to their environments by:

- self-directed identity claims (eg. purposeful decorations like posters or use of colour);

- other-directed identity claims (eg. decorations which communicate shared values that others would recognise);

- interior behavioural residue (ie. "physical traces of activities conducted within an environment");

- exterior behavioural residue (ie. traces of activities conducted outside of the immediate environment which nonetheless provide some cues as to the personality of the environment occupant).

Self-presentation is largely unconscious in the physical realm and comes naturally to most people. People may also use in-crowd markers (like a shirt with a band logo on) consciously to send certain messages to people who will recognise them, whilst not drawing any attention from people who won't [ boydfacid ]. Later in this chapter I look at how our presence in digital spaces fail and succeed to take the place of the physical body when it comes to interactions and identity formation.

https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2013/01/10/context-collapse-a-literature-review/

Social psychologists argue that we come to know ourselves by seeing what we do and how others react to us, and that through interaction, actors seek to maintain the identity meanings associated with each role (Burke and Stets 2009; Cooley 1902; Mead 1934). Indeed, Mead (1934) contends that for each role the actor plays, there is a separate Generalized Other, or larger moral understanding of who the person is and how the person is expected to be in the world, and that social actors manage their roles by adhering to disparate expectations as is situationally necessary. Similarly, Goffman (1959) demonstrates the skillful ways in which social actors reveal and conceal aspects of themselves for varying audiences, maintaining separate faces within distinct social arenas, while Leary (1995) discusses playing to each audience, their values, and their perceived positive opinion of the actor.

The self in context

By reflexively adjusting one’s perception of self in reaction to society, people construct their individual identity. [ boydfacid ]

Development of personal identity is not only something that happens internally. We are strongly influenced by feedback (conscious and unconscious) from others around us, as well as the particular setting and culture in which we find ourselves. How we react to things outside of our control in part determines our identity construction, and some people adjust their behaviour in response to feedback more than others [ snyder74 ]. Thus identity is socially constructed, and often is dynamically adjusted according to context [ boydfacid ].

(self-awareness is identity situated as in society.) A person's understanding of the context in which they are performing impacts their performance [boydfacid]. boyd argues that online, people find it much more difficult to evaluate this context, and thus run increased risk of performing inappropriately, or experience context collapse when multiple audiences are inadvertently combined. This is explored further in section 4 .

…. political, cultural, racial. stuff about web dissolving these [Turkle], but not really. [Kenny] study about people using identity language (with a corpus of terms that corresponds to culture/society), but in content not wrt themselves or in their profiles.

The project of the self

Giddens [ giddens84 ] looks at the relationship between macro and micro views of the world, acknowledging that broader effects of society impact individual behaviour, and vice versa, with neither one being the primary driving force. This suits well my ideas about online self-presentation, confirming the complex interplay between technological affordances, individual actions, and the place of both in a cultural and social context.

Giddens argues that self-identity is an aggregation of a person's experiences, an ongoing account, and a continuous integration of events. In contrast to Goffman's dramaturgy, Giddens downplays the role of an audience, and in contrast to Brunswik's lens theory, he downplays what we can learn from the traces someone leaves behind. Giddens argues that self-identity cannot be uncovered from a moment, but something which is ongoing, over time. Modern society, according to Giddens, affords us more freedom to create our own narratives to determine our self-identity. In the past, rigid social expectations dictated our roles for us. However, increased choices about what to do with ourselves may also increase stress and prove problematic. Awareness of the body is central to awareness of the self, as the body is directly involved in moments we experience in daily life. As we are now explicitly constructing a narrative about our identities, rather than having one ascribed to us by society, the self is an ongoing project which takes work to maintain [ giddens91 ].

The focus on explicit actions and decision making about self-presentation is pertinent when it comes to digital representations of identity.

Extending the self

Early to mid 20th century philosophers and social scientists complicate notions of the 'self' by combining it and extending it with our physical surroundings, and this view emerged long before the Web. Heidegger expresses technology as coming into being through use by a human; when tools are used the tool and its user do not exist as independent entities, but as the experience of the task at hand (using the example of a carpenter hammering, unaware of himself or his hammer) [ manhammer ]. McLuhan discusses media, literate and electronic, from the printing press and electric light to radio, TV and telephone, and its impact on how we communicate. He places communication technologies as simultaneously extensions of and amputations of our bodies and senses, which continuously and fundamentally re-shape the way we (humans) see and place ourselves the world [ mcluhan ]. More recently, Clark's Extended Mind Theory uses the example of a notebook as a means of externally processing information that would otherwise be carried out by the brain, drawing the external world in as party to our cognitive processes [ clarkmind ].

The next logical step is to consider how the modern digital technologies of Web and social networking can also be considered extensions of the self, and this is addressed in part by Luppicini's notion of Technoself [ technoself ]. Technoself incorporates (amongst other things) extension of the self through physical technology embedded in the body (cyborgology); in our changing understanding of what it is to be , as life is extended and augmented through advancing healthcare; but also in our relationships with our virtual selves. This is not a topic into which I will dive deeply from a philosophical standpoint, but the idea of the Web and online social networks as extensions to the self rather than as separate entities or concepts is worth bearing in mind as this thesis proceeds to explore the complexities of intertwined digital and offline identities.

maybe something to do with hyperreality, Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

Offline to online… and back again

When people use digital technologies to communicate, they are passing a version of themselves through the filter of the platform they use. In this section I discuss the relationships between online and offline selves.