- Chapter 3: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

What is a Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Design?

Tips for using narrative inquiry in a dissertation, summary of the elements of a qualitative narrative inquiry design, sampling and data collection, resource videos.

- SAGE Research Methods

- Alignment of Dissertation Components for DIS-9902ABC

- IRB Resources This link opens in a new window

- Research Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- Dataset Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

Narrative inquiry is relatively new among the qualitative research designs compared to qualitative case study, phenomenology, ethnography, and grounded theory. What distinguishes narrative inquiry is it beings with the biographical aspect of C. Wright Mills’ trilogy of ‘biography, history, and society’(O’Tolle, 2018). The primary purpose for a narrative inquiry study is participants provide the researcher with their life experiences through thick rich stories. Narrative inquiry was first used by Connelly and Calandinin as a research design to explore the perceptions and personal stories of teachers (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990). As the seminal authors, Connelly & Clandinin (1990), posited:

Although narrative inquiry has a long intellectual history both in and out of education, it is increasingly used in studies of educational experience. One theory in educational research holds that humans are storytelling organisms who, individually and socially, lead storied lives. Thus, the study of narrative is the study of the ways humans experience the world. This general concept is refined into the view that education and educational research is the construction and reconstruction of personal and social stories; learners, teachers, and researchers are storytellers and characters in their own and other's stories. In this paper we briefly survey forms of narrative inquiry in educational studies and outline certain criteria, methods, and writing forms, which we describe in terms of beginning the story, living the story, and selecting stories to construct and reconstruct narrative plots.

Attribution: Reprint Policy for Educational Researcher: No written or oral permission is necessary to reproduce a tale, a figure, or an excerpt fewer that 500 words from this journal, or to make photocopies for classroom use. Copyright (1990) by the American Educational Research Association; reproduced with permission from the publisher.

The popularity of narrative inquiry in education is increasing as a circular and pedagogical strategy that lends itself to the practical application of research (Kim, 2016). Keep in mind that by and large practical and professional benefits that arise from a narrative inquiry study revolve around exploring the lived experiences of educators, education administrators, students, and parents or guardians. According to Dunne (2003),

Research into teaching is best served by narrative modes of inquiry since to understand the teacher’s practice (on his or her own part or on the part of an observer) is to find an illuminating story (or stories) to tell of what they have been involved with their student” (p. 367).

- Temporality – the time of the experiences and how the experiences could influence the future;

- Sociality – cultural and personal influences of the experiences; and;

- Spatiality – the environmental surroundings during the experiences and their influence on the experiences.

From Haydon and van der Riet (2017)

- Narrative researchers collect stories from individuals retelling of their life experiences to a particular phenomenon.

- Narrative stories may explore personal characteristics or identities of individuals and how they view themselves in a personal or larger context.

- Chronology is often important in narrative studies, as it allows participants to recall specific places, situations, or changes within their life history.

Sampling and Sample Size

- Purposive sampling is the most often used in narrative inquiry studies. Participants must meet a form of requirement that fits the purpose, problem, and objective of the study

- There is no rule for the sample size for narrative inquiry study. For a dissertation the normal sample size is between 6-10 participants. The reason for this is sampling should be terminated when no new information is forthcoming, which is a common strategy in qualitative studies known as sampling to the point of redundancy.

Data Collection (Methodology)

- Participant and researcher collaborate through the research process to ensure the story told and the story align.

- Extensive “time in the field” (can use Zoom) is spent with participant(s) to gather stories through multiple types of information including, field notes, observations, photos, artifacts, etc.

- Field Test is strongly recommended. The purpose of a field study is to have a panel of experts in the profession of the study review the research protocol and interview questions to ensure they align to the purpose statement and research questions.

- Member Checking is recommended. The trustworthiness of results is the bedrock of high-quality qualitative research. Member checking, also known as participant or respondent validation, is a technique for exploring the credibility of results. Data or results are returned to participants to check for accuracy and resonance with their experiences. Member checking is often mentioned as one in a list of validation techniques (Birt, et al., 2016).

Narrative Data Collection Essentials

- Restorying is the process of gathering stories, analyzing themes for key elements (e.g., time, place, plot, and environment) and then rewriting the stories to place them within a chronological sequence (Ollerenshaw & Creswell, 2002).

- Narrative thinking is critical in a narrative inquiry study. According to Kim (2016), the premise of narrative thinking comprises of three components, the storyteller’s narrative schema, his or her prior knowledge and experience, and cognitive strategies-yields a story that facilitates an understanding of the others and oneself in relation to others.

Instrumentation

- In qualitative research the researcher is the primary instrument.

- In-depth, semi-structured interviews are the norm. Because of the rigor that is required for a narrative inquiry study, it is recommended that two interviews with the same participant be conducted. The primary interview and a follow-up interview to address any additional questions that may arise from the interview transcriptions and/or member checking.

Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26 (13), 1802-1811. http://dx.doi.org./10.1177/1049732316654870

Cline, J. M. (2020). Collaborative learning for students with learning disabilities in inclusive classrooms: A qualitative narrative inquiry study (Order No. 28263106). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2503473076).

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19 (5), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2018.1465839

Dunne, J. (2003). Arguing for teaching as a practice: A reply to Alasdair Macintyre. Journal of Philosophy of Education . https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.00331

Haydon, G., & der Riet, P. van. (2017). Narrative inquiry: A relational research methodology suitable to explore narratives of health and illness. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research , 37(2), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057158516675217

Kim, J. H. (2016). Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The crafting and analysis of stories as research. Sage Publications.

Kim J. H. (2017). Jeong-Hee Kim discusses narrative methods [Video]. SAGE Research Methods Video https://www-doi-org.proxy1.ncu.edu/10.4135/9781473985179

O’ Toole, J. (2018). Institutional storytelling and personal narratives: reflecting on the value of narrative inquiry. Institutional Educational Studies, 37 (2), 175-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2018.1465839

Ollerenshaw, J. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2002). Narrative research: A comparison of two restorying data analysis approaches. Qualitative Inquiry, 8 (3), 329–347.

- << Previous: Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Next: SAGE Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: Nov 2, 2023 10:17 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1007179

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

Qualitative study design: Narrative inquiry

- Qualitative study design

- Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

Narrative inquiry can reveal unique perspectives and deeper understanding of a situation. Often giving voice to marginalised populations whose perspective is not often sought.

Narrative inquiry records the experiences of an individual or small group, revealing the lived experience or particular perspective of that individual, usually primarily through interview which is then recorded and ordered into a chronological narrative. Often recorded as biography, life history or in the case of older/ancient traditional story recording - oral history.

- Qualitative survey

- Recordings of oral history (documents can be used as support for correlation and triangulation of information mentioned in interview.)

- Focus groups can be used where the focus is a small group or community.

Reveals in-depth detail of a situation or life experience.

Can reveal historically significant issues not elsewhere recorded.

Narrative research was considered a way to democratise the documentation and lived experience of a wider gamut of society. In the past only the rich could afford a biographer to have their life experience recorded, narrative research gave voice to marginalised people and their lived experience.

Limitations

“The Hawthorne Effect is the tendency, particularly in social experiments, for people to modify their behaviour because they know they are being studied, and so to distort (usually unwittingly) the research findings.” SRMO

The researcher must be heavily embedded in the topic with a broad understanding of the subject’s life experience in order to effectively and realistically represent the subject’s life experience.

There is a lot of data to be worked through making this a time-consuming method beyond even the interview process itself.

Subject’s will focus on their lived experience and not comment on the greater social movements at work at the time. For example, how the Global Financial Crisis affected their lives, not what caused the Global Financial Crisis.

This research method relies heavily on the memory of the subject. Therefore, triangulation of the information is recommended such as asking the question in a different way, at a later date, looking for correlating documentation or interviewing similarly related participants.

Example questions

- What is the lived experience of a home carer for a terminal cancer patient?

- What is it like for parents to have their children die young?

- What was the role of the nurse in Australian hospitals in the 1960s?

- What is it like to live with cerebral palsy?

- What are the difficulties of living in a wheelchair?

Example studies

- Francis, M. (2018). A Narrative Inquiry Into the Experience of Being a Victim of Gun Violence. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 25(6), 381–388. https://doi-org.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/10.1097/JTN.0000000000000406

- Kean, B., Oprescu, F., Gray, M., & Burkett, B. (2018). Commitment to physical activity and health: A case study of a paralympic gold medallist. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(17), 2093-2097. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1323234 https://doi-org.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/10.1080/09638288.2017.1323234

- Liamputtong, P. (2009). Qualitative research methods. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b2351301&site=eds-live

- Padgett, D. (2012). Qualitative and mixed methods in public health. SAGE. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b3657335&authtype=sso&custid=deakin&site=eds-live&scope=site

- << Previous: Historical

- Next: Action research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 11:12 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

Difference Between Case Study And Narrative Research

- Success Team

- January 19, 2023

Working with language data? Save 80%+ of your time and costs.

Join 150,000+ individuals and teams who rely on speak ai to capture and analyze unstructured language data for valuable insights. streamline your workflows, unlock new revenue streams and keep doing what you love..

Get a 7-day fully-featured trial!

Research is an important part of any organization or business. There are two main types of research: case studies and narrative research. Both are valuable tools for gathering and analyzing information, but they have some important differences. Understanding the difference between case study and narrative research can help you select the best research method for your particular project.

What is Case Study Research?

Case study research is a type of qualitative research that focuses on a single case, or a small number of cases, to examine in depth. It seeks to understand a phenomenon by examining the context of the case and looking at the experiences, perspectives, and behavior of the people involved. Case study research is often used to explore complex social phenomena, such as poverty, health, education, and social change.

What is Narrative Research?

Narrative research is also a type of qualitative research that focuses on understanding how people make sense of their experiences. It involves collecting and analyzing stories, or narratives, from participants. These stories can be collected through interviews, focus groups, or other data collection techniques. By examining the stories in detail, researchers can gain insights into how people think about and make sense of the world around them.

Differences Between Case Study and Narrative Research

The most important differences between case study and narrative research are the focus and the type of data collected. Case studies focus on a single case or a small number of cases, while narrative research focuses on understanding how people make sense of their experiences. Case studies typically rely on quantitative data, such as surveys and measurements, while narrative research relies on qualitative data, such as interviews, stories, and observations.

Which is Better?

The answer to this question depends on the research question and the type of data needed to answer it. If the goal is to understand a single case in depth, then a case study is the best approach. If the goal is to understand how people make sense of their experiences, then narrative research is the best approach. In some cases, it may be beneficial to use a combination of both approaches.

Case study and narrative research are both valuable tools for gathering and analyzing information. Understanding the difference between the two can help you select the best research method for your particular project. While case studies are useful for understanding a single case in depth, narrative research is better for understanding how people make sense of their experiences. In some cases, it may be beneficial to use a combination of both approaches.

How To Use The Best Large Language Models For Research With Speak

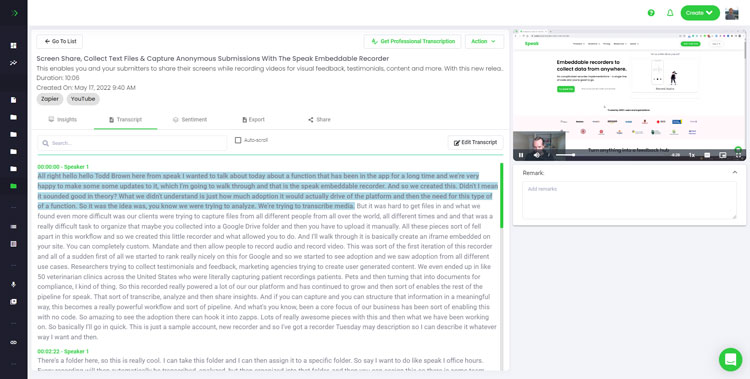

Step 1: Create Your Speak Account

To start your transcription and analysis, you first need to create a Speak account . No worries, this is super easy to do!

Get a 7-day trial with 30 minutes of free English audio and video transcription included when you sign up for Speak.

To sign up for Speak and start using Speak Magic Prompts, visit the Speak app register page here .

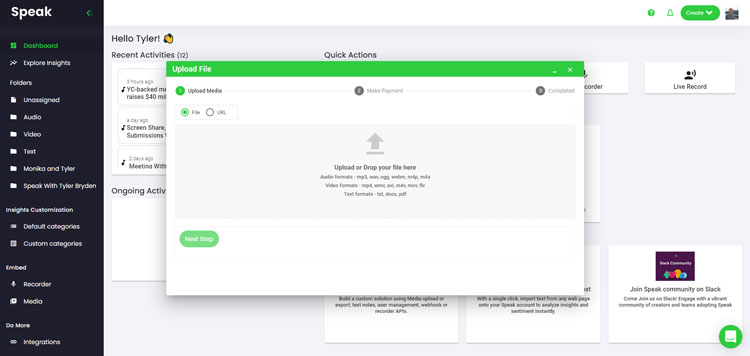

Step 2: Upload Your Research Data

We typically recommend MP4s for video or MP3s for audio.

However, we accept a range of audio, video and text file types.

You can upload your file for transcription in several ways using Speak:

Accepted Audio File Types

Accepted video file types, accepted text file types, csv imports.

You can also upload CSVs of text files or audio and video files. You can learn more about CSV uploads and download Speak-compatible CSVs here .

With the CSVs, you can upload anything from dozens of YouTube videos to thousands of Interview Data.

Publicly Available URLs

You can also upload media to Speak through a publicly available URL.

As long as the file type extension is available at the end of the URL you will have no problem importing your recording for automatic transcription and analysis.

YouTube URLs

Speak is compatible with YouTube videos. All you have to do is copy the URL of the YouTube video (for example, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qKfcLcHeivc ).

Speak will automatically find the file, calculate the length, and import the video.

If using YouTube videos, please make sure you use the full link and not the shortened YouTube snippet. Additionally, make sure you remove the channel name from the URL.

Speak Integrations

As mentioned, Speak also contains a range of integrations for Zoom , Zapier , Vimeo and more that will help you automatically transcribe your media.

This library of integrations continues to grow! Have a request? Feel encouraged to send us a message.

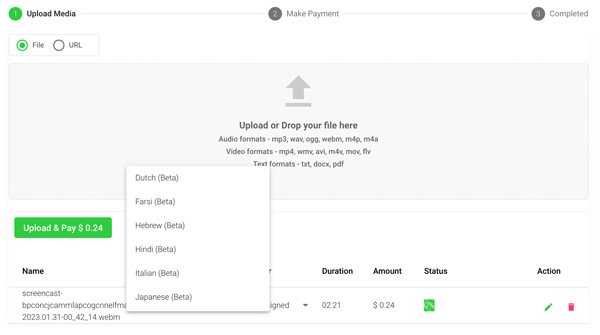

Step 3: Calculate and Pay the Total Automatically

Once you have your file(s) ready and load it into Speak, it will automatically calculate the total cost (you get 30 minutes of audio and video free in the 7-day trial - take advantage of it!).

If you are uploading text data into Speak, you do not currently have to pay any cost. Only the Speak Magic Prompts analysis would create a fee which will be detailed below.

Once you go over your 30 minutes or need to use Speak Magic Prompts, you can pay by subscribing to a personalized plan using our real-time calculator .

You can also add a balance or pay for uploads and analysis without a plan using your credit card .

Step 4: Wait for Speak to Analyze Your Research Data

If you are uploading audio and video, our automated transcription software will prepare your transcript quickly. Once completed, you will get an email notification that your transcript is complete. That email will contain a link back to the file so you can access the interactive media player with the transcript, analysis, and export formats ready for you.

If you are importing CSVs or uploading text files Speak will generally analyze the information much more quickly.

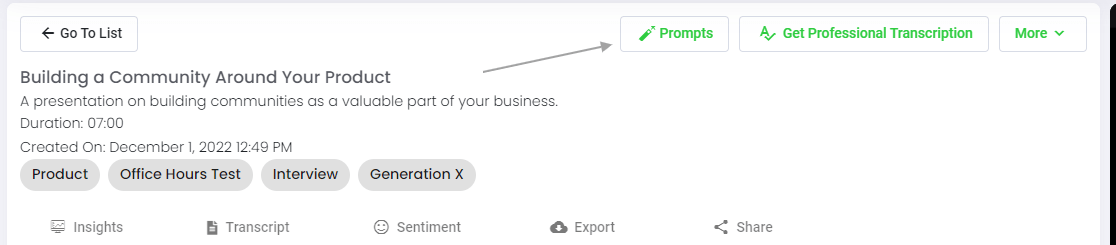

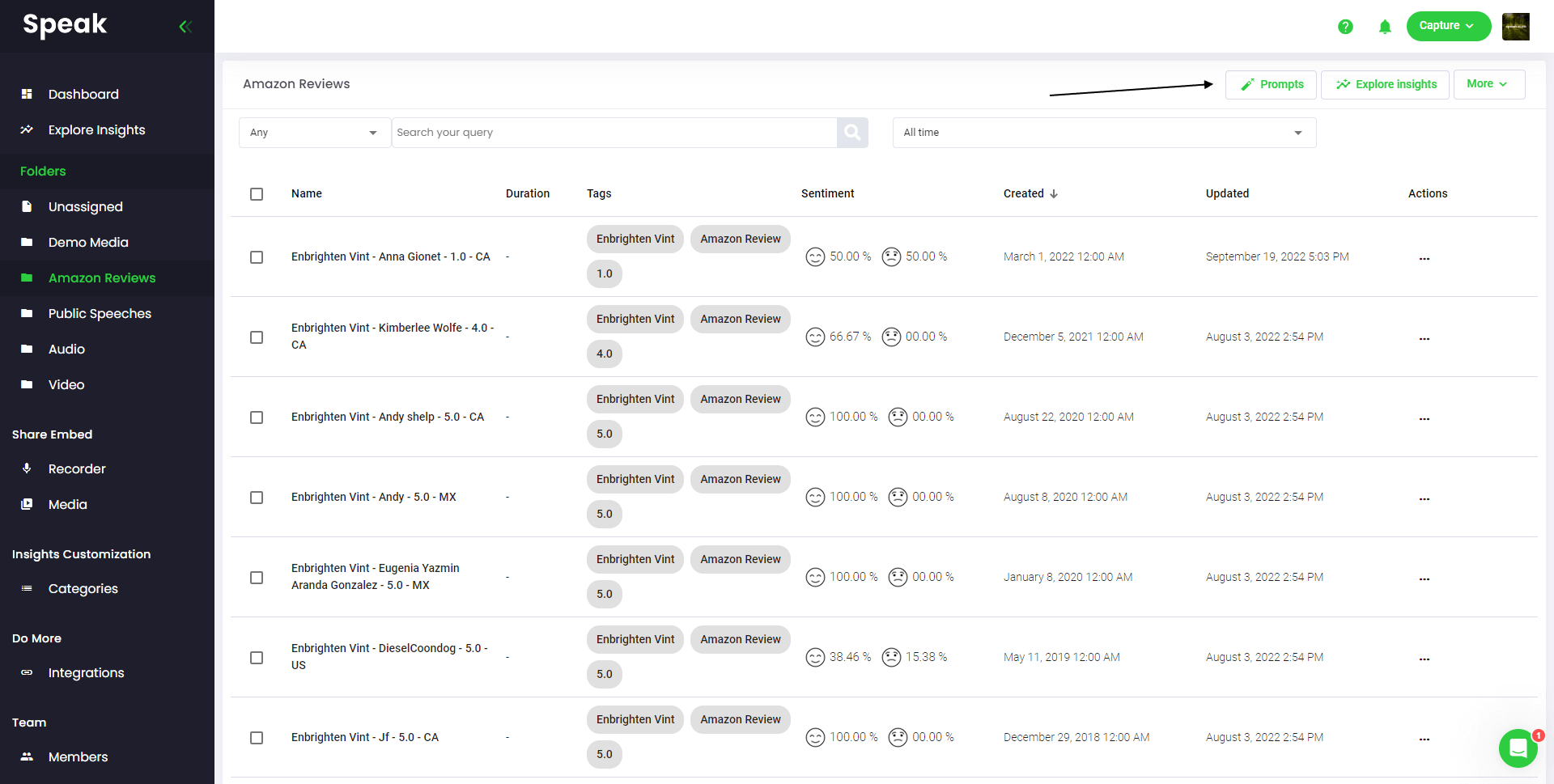

Step 5: Visit Your File Or Folder

Speak is capable of analyzing both individual files and entire folders of data.

When you are viewing any individual file in Speak, all you have to do is click on the "Prompts" button.

If you want to analyze many files, all you have to do is add the files you want to analyze into a folder within Speak.

You can do that by adding new files into Speak or you can organize your current files into your desired folder with the software's easy editing functionality.

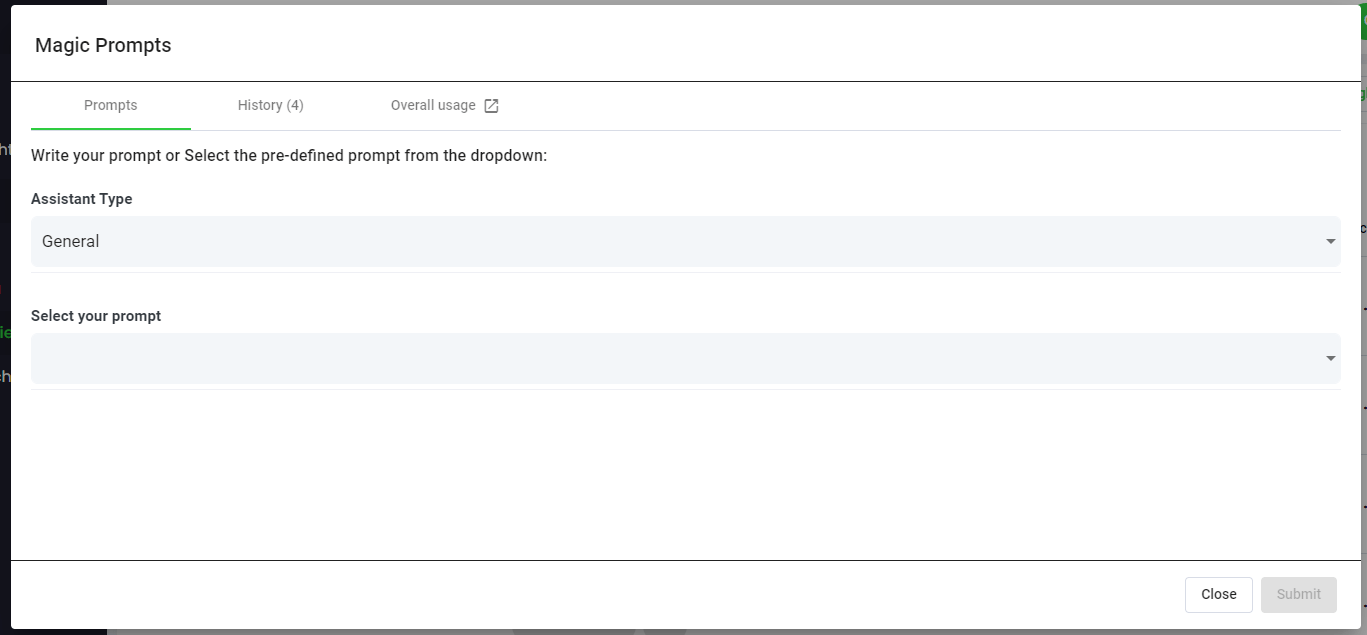

Step 6: Select Speak Magic Prompts To Analyze Your Research Data

What are magic prompts.

Speak Magic Prompts leverage innovation in artificial intelligence models often referred to as "generative AI".

These models have analyzed huge amounts of data from across the internet to gain an understanding of language.

With that understanding, these "large language models" are capable of performing mind-bending tasks!

With Speak Magic Prompts, you can now perform those tasks on the audio, video and text data in your Speak account.

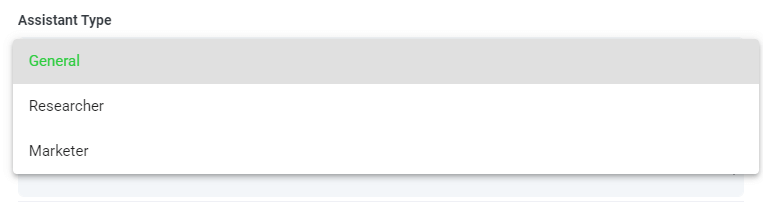

Step 7: Select Your Assistant Type

To help you get better results from Speak Magic Prompts, Speak has introduced "Assistant Type".

These assistant types pre-set and provide context to the prompt engine for more concise, meaningful outputs based on your needs.

To begin, we have included:

Choose the most relevant assistant type from the dropdown.

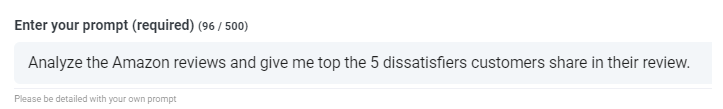

Step 8: Create Or Select Your Desired Prompt

Here are some examples prompts that you can apply to any file right now:

- Create a SWOT Analysis

- Give me the top action items

- Create a bullet point list summary

- Tell me the key issues that were left unresolved

- Tell me what questions were asked

- Create Your Own Custom Prompts

A modal will pop up so you can use the suggested prompts we shared above to instantly and magically get your answers.

If you have your own prompts you want to create, select "Custom Prompt" from the dropdown and another text box will open where you can ask anything you want of your data!

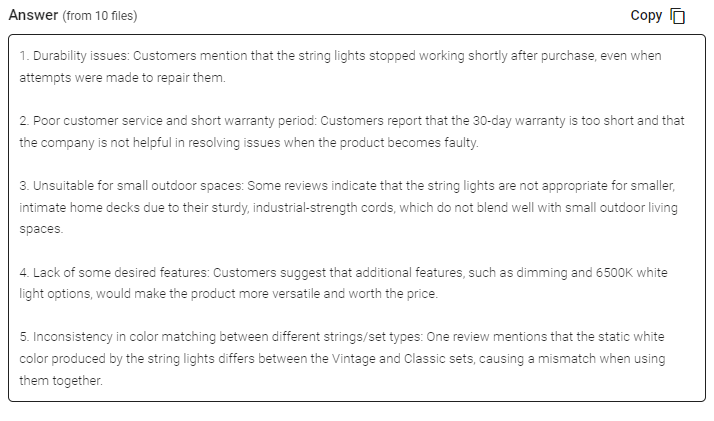

Step 9: Review & Share Responses

Speak will generate a concise response for you in a text box below the prompt selection dropdown.

In this example, we ask to analyze all the Interview Data in the folder at once for the top product dissatisfiers.

You can easily copy that response for your presentations, content, emails, team members and more!

Speak Magic Prompts As ChatGPT For Research Data Pricing

Our team at Speak Ai continues to optimize the pricing for Magic Prompts and Speak as a whole.

Right now, anyone in the 7-day trial of Speak gets 100,000 characters included in their account.

If you need more characters, you can easily include Speak Magic Prompts in your plan when you create a subscription.

You can also upgrade the number of characters in your account if you already have a subscription.

Both options are available on the subscription page .

Alternatively, you can use Speak Magic Prompts by adding a balance to your account. The balance will be used as you analyze characters.

Completely Personalize Your Plan 📝

Here at Speak, we've made it incredibly easy to personalize your subscription.

Once you sign-up, just visit our custom plan builder and select the media volume, team size, and features you want to get a plan that fits your needs.

No more rigid plans. Upgrade, downgrade or cancel at any time.

Claim Your Special Offer 🎁

When you subscribe, you will also get a free premium add-on for three months!

That means you save up to $50 USD per month and $150 USD in total.

Once you subscribe to a plan, all you have to do is send us a live chat with your selected premium add-on from the list below:

- Premium Export Options (Word, CSV & More)

- Custom Categories & Insights

- Bulk Editing & Data Organization

- Recorder Customization (Branding, Input & More)

- Media Player Customization

- Shareable Media Libraries

We will put the add-on live in your account free of charge!

What are you waiting for?

Refer Others & Earn Real Money 💸

If you have friends, peers and followers interested in using our platform, you can earn real monthly money.

You will get paid a percentage of all sales whether the customers you refer to pay for a plan, automatically transcribe media or leverage professional transcription services.

Use this link to become an official Speak affiliate.

Check Out Our Dedicated Resources📚

- Speak Ai YouTube Channel

- Guide To Building Your Perfect Speak Plan

Book A Free Implementation Session 🤝

It would be an honour to personally jump on an introductory call with you to make sure you are set up for success.

Just use our Calendly link to find a time that works well for you. We look forward to meeting you!

Save 99% of your time and costs!

Use Speak's powerful AI to transcribe, analyze, automate and produce incredible insights for you and your team.

Narrative Inquiry

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Benjamin Kutsyuruba 4 &

- Rebecca Stroud Stasel 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

4464 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter describes the narrative inquiry approach. Narrative inquiry has dual purpose as a methodology and a conceptual framework, and generally focuses on stories or narratives or descriptions of a series of events. It is this attention to analyzing and understanding stories lived and told that situates narrative inquiry as a qualitative research methodology. In this chapter, we provide key elements of narrative inquiry as a qualitative research methodology which can help guide scholars towards further examination based upon their purposes and interests with narrative. We outline the brief history, purpose, and methods of narrative inquiry, provide an outline of its process, strengths and limitations, and application, and offer further readings, resources, and suggestions for student engagement activities.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bolton, G. (2006). Narrative writing: Reflective enquiry into professional practice. Educational Action Research, 14 (2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790600718076

Article Google Scholar

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds . Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Clandinin, D., & Connelly, F. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research . Jossey-Bass.

Google Scholar

Clandinin, D. J., & Murphy, M. S. (2007). Looking ahead: Conversations with Elliot Mishler, Don Polkinghorne, and Amia Lieblich. In D. J. (Ed.). Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 632–650). SAGE.

Clandinin, D. J., & Rosiek, J. L. (2007). Mapping a landscape of narrative inquiry: Borderland spaces and tensions. In D. J. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 35–76). SAGE.

Clandinin, D. J. (2013). Engaging in narrative inquiry . Left Coast Press.

Clandinin, D. J., & Huber, J. (2010). Narrative inquiry. In E. Baker & B. McGaw (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (3rd ed., pp. 436–441). Elsevier.

Chapter Google Scholar

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19 (5), 2–14.

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1999). Narrative inquiry. In J. P. Keeves & G. Lakomski (Eds.), Issues in educational research (pp. 132–140). Pergamon.

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry. In J. Green, G. Camilli, & P. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 375–385). Erlbaum.

Craig, C. J. (2014). From stories of staying to stories of leaving: A US beginning teacher’s experience. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46 (1), 81–115.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Handbook of qualitative research . SAGE.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education . Macmillan. https://www.schoolofeducators.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/EXPERIENCE-EDUCATION-JOHN-DEWEY.pdf

Dewey, J. (2012). Democracy and education . Start Publishing.

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 733–768). SAGE.

Elbaz-Luwisch, F. (2007). Studying teachers’ lives and experience: Narrative inquiry into K-12 teaching. In D. J. Clandinin (Ed.), Narrative inquiry (pp. 357–381). SAGE.

Geertz, C. (1983). Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology . Basic Books.

Hurworth, R. (2003). Photo-interviewing for research. Social Research Update, 40 , 1–4.

Van Maanen, J. (1988). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography . University of Chicago Press.

MacIntyre, A. C. (1981). After virtue: A study in moral theory . University of Notre Dame Press.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (1999). Designing qualitative research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Martin, W. (1986). Recent theories of narrative . Cornell University Press.

McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2010). Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (7th ed.). Pearson.

Pinnegar, S., & Daynes, J. G. (2007). Locating narrative inquiry historically: Thematics in the turn to narrative. In D. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 3–34). SAGE.

Polkinghorne, D. (1988). Narrative knowing in the human sciences . State University of New York Press.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences . SAGE.

Riessman, C. K., & Speedy, J. (2007). Narrative inquiry in the psychotherapy professions: A critical review. In D. J. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 426–456). SAGE.

Roy, A. (1997). The god of small things . Random House.

Sarbin, T. R. (Ed.). (1986). Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct . Praeger.

Taylor, S. (2007). A narrative inquiry into the experience of women seeking professional help with severe chronic migraines (Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB).

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behavior, 24 (3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Benjamin Kutsyuruba & Rebecca Stroud Stasel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benjamin Kutsyuruba .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Janet Mola Okoko

Scott Tunison

Department of Educational Administration, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Keith D. Walker

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Kutsyuruba, B., Stasel, R.S. (2023). Narrative Inquiry. In: Okoko, J.M., Tunison, S., Walker, K.D. (eds) Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_51

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_51

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-04396-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-04394-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Narrative approaches to case studies

Related Papers

International Journal of Qualitative Methods

Elelwani Ramugondo

Case study and narrative inquiry as merged methodological frameworks can make a vital contribution that seeks to understand processes that may explain current realities within professions and broader society. This article offers an explanation of how a critical perspective on case study and narrative inquiry as an embedded methodology unearthed the interplay between structure and agency within storied lives. This case narrative emerged out of a doctoral thesis in occupational therapy, a single instrumental case describing a process of professional role transition within school-level specialized education in the Western Cape, South Africa. This case served as an exemplar in demonstrating how case study recognized the multiple layers to the context within which the process of professional role transition unfolded. The embedded narrative inquiry served to clarify emerging professional identities for occupational therapists within school-level specialized education in postapartheid Sout...

Maria Tamboukou

"Examining narrative methods in the context of its multi-disciplinary social science origins, this text looks at its theoretical underpinnings, while retaining an emphasis on the process of doing narrative research. The authors provide a comprehensive guide to narrative methods, taking the reader from initial decisions about forms of narrative analysis, through more complex issues of reflexivity, interpretation and the research context. The contributions included here clearly demonstrate the value of narrative methods for contemporary social research and practice. This book will be invaluable for all social science postgraduate students and researchers looking to use narrative methods in their own research."

Doing Narrative Research edition 1

Corinne Squire

Hervé Corvellec

This article is intended to be an introduction to narrative analysis. It introduces key terms in narrative theory (eg story and plot), discusses various types of narratives relevant for social studies and features three selected analytical approaches to narratives: a poetic classification, a tripartite way of reading and a deconstructive analysis. The conclusion presents some reflections on narratives as ways to make sense of time.

Hubert Van Puyenbroeck

John Schostak

Anecdotes are central to understanding and writing about people's lives. They provide an essential stepping stone to case studies and are fundamental to qualitative research methodologies. It draws upon Laclau's poststructuralist approach to discourse in exploring the development of narrative based case studies and in doing so presents an approach to 'triangulation' as a basis for validity and the reduction of bias.

NB This paper is a draft. Please reference the chapter as published: Esin, C., Fathi, M., & Squire, C. (2014). Narrative analysis: The constructionist approach. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. (pp. 203-217). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446282243.n14 Narrative analysis is an analytical method that accommodates a variety of approaches. Through these approaches, social researchers explore how people story their lives. This is also a process through which researchers understand the complexities of personal and social relations. Narrative analysis provides the researcher with useful tools to comprehend the diversity and the different levels involved in stories, rather than treating those stories simply as coherent, natural and unified entities (Andrews et al., 2004). It is this approach to narrative analysis, which we shall call the constructionist approach to narrative analysis, that we aim to explain in the chapter that follows.

Maura Striano

Corinne Squire , shelley day sclater

David M Boje

Narrative analysis is the sequencing of events and character identities derived by retrospective sensory representation. Narrative representations includes first a chronology and second a whole structure of constituent elements that relate together in poetic form, in order to examine how past shapes present, present perspectives filter the past. Narrative analysis represents how the author and others value events, characters, and elements differently. Narrative analysis can be applied to cases used for pedagogy and theory building in the social sciences. Case narratives are sensory representations derived from oral, document, or observational sources (including dramaturgical gestures, décor, or architecture).

RELATED PAPERS

Susana Chavez

Panagiotis Filos

Çocuk Enfeksiyon Dergisi/Journal of Pediatric Infection

Gulsah Demir

Journal of Wireless Communications

Niranjan Panigrahi

Physical Review Letters

MONALIZA RIOS SILVA

Xavier Banquy

Ciência Florestal

Stevanie (C1C119003)

Mahmud Yusuf

Law Нerald of Dagestan State University

LEGAL ADVISOR

BMC psychology

Raul Vicente SALVA ARCOS

International Journal of Communication Systems

Celine Mary Stuart

Transactual

Natacha Kennedy

Journal of Evidence Based Medicine and Healthcare

MD Shamim rana

Macromolecules

Christiane Helm

Salsabila Syah Rokhim

Advances in Social Work

Janelle Bryan

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

Dimitris Antoniadis

Clinical Infectious Diseases

MARÍA GANAHA

Renewable Energy

Grigoris Papagiannis

Applied Soil Ecology

Genxing Pan

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, narrative, storytelling and program evaluation, the context: a community intervention trial to promote the health of recent mothers, illustrating the analytic approach: the unique insights from narrative, two examples of stories from the cdo data set, concluding remarks.

- < Previous

Researching practice: the methodological case for narrative inquiry

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Therese Riley, Penelope Hawe, Researching practice: the methodological case for narrative inquiry, Health Education Research , Volume 20, Issue 2, April 2005, Pages 226–236, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg122

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Research interest in the analysis of stories has increased as researchers in many disciplines endeavor to see the world through the eyes of others. We make the methodological case for narrative inquiry as a unique means to get inside the world of health promotion practice. We demonstrate how this form of inquiry may reveal what practitioners value most in and through their practice, and the indigenous theory or the cause-and-consequence thinking that governs their actions. Our examples draw on a unique data set, i.e. 2 two years' of diaries being kept by community development officers in eight communities engaged in a primary care and community development intervention to reduce postnatal depression and promote the physical health of recent mothers. Narrative inquiry examines the way a story is told by considering the positioning of the actor/storyteller, the endpoints, the supporting cast, the sequencing and the tension created by the revelation of some events, in preference to others. Narrative methods may provide special insights into the complexity of community intervention implementation over and above more familiar research methods.

When preventive intervention programs are described, they tend to focus on the technology of the intervention without informing us about how the context in which it was implemented affected the technology. We learn little about the many compromises, choice points and backroom conversations that allowed it to take the form it took. [( Trickett, 1998 ), p. 329].

The history of health promotion has been one of developing and testing increasingly sophisticated theories to inform and strengthen the effectiveness of actions taken by the front-line workers. Theories of health promotion have been developed for multiple levels of analysis (individual, group, organizational, community, etc.) ( Glanz et al. , 1990 ) and for a variety of settings (schools, workplaces, hospitals, etc.) ( Poland et al. , 2000 ). Large-scale, whole-community prevention trials have been conducted purporting to test particular state-of-the-art theories in cancer control and heart disease prevention ( Thompson et al. , 2003 ). Studies of interventions typically include process evaluations, which allow investigators to comment on the extent to which what took place actually matched what was planned ( Flora et al. , 1993 ).

What we hear less about, however, is the private contexts of practice as Trickett describes above and ways of viewing the ‘problem’ at hand other than those preconceived by the intervention's designers. Evaluators who use qualitative methods may get closer to this ( Patton, 1990 ). ‘Key informant’ interviews have become increasingly used to gain insight into the factors that have helped or hindered program development or might explain why programs appear to work in some contexts, but not in others ( Goodman et al. , 1993 ). Even so, this literature contains examples of studies where interviews held at the end of the program still have failed to give investigators confidence about what really happened and why ( Tudor-Smith et al. , 1998 ). Investigators who have engaged practitioners in interviews about the nature of their practice have also commented on how difficult it is for people, in retrospect, to articulate aspects of what they do and think ( Hawe et al. , 1998 ). Thus, many aspects of practice remain elusive.

In this paper we suggest that narrative methods may give new and deeper insights into the complexity of practice contexts. By narrative inquiry, we mean the use of personal journals by and serial interviews with fieldworkers during their implementation of a health promotion intervention. Narrative methods may also allow us to better understand the mechanisms through which health programs are transported and translated. In doing so, the natural or indigenous theory of an intervention may be revealed, i.e. the cause-and-consequence thinking of practitioners, which may or may not match the theory supposed to be tested by the intervention. We use a case study from a whole-community intervention trial to illustrate how we are using these methods. The results of the analysis are not presented here.

Narrative inquiry has a long, strong and contested tradition. There are a range of approaches to narrative inquiry, emanating from diverse disciplines such as psychology, sociology, medicine, literature and cultural studies ( Riessman, 1993 ; Mishler, 1995 ). As a result, the process of interpreting stories is now a point of scholarly investigation in itself, because there is no one unifying method ( Riessman, 1993 ; Mishler, 1995 ; Schegloff, 1997 ; Manning et al. , 1998 ). Approaches differ on the core questions of why and how stories are told. That is, the nature of the storytelling occasion and therefore the knowledge claims that can be made about the problem under investigation.

‘Story’ and ‘narrative’ are words often used interchangeably, but they are analytically different. The difference relates to where the primary data ends and where the analysis of that data begins. Frank ( Frank, 2000 ) points out that people tell stories, but narratives come from the analysis of stories. Therefore, the researcher's role is to interpret the stories in order to analyze the underlying narrative that the storytellers may not be able to give voice to themselves. For example, in a narrative study of people who are unemployed, Ezzy ( Ezzy, 2000 ) explored the role that broader social forces play in how people tell stories about their job loss. He described two narratives: the heroic and tragic job loss narratives. The heroic narrative gives prominence to the role of a person's individual agency and autonomy, whereas the tragic job loss narrative is one is which the person is a victim of institutional or social forces beyond their control. These narrative structures provide insights into how people come to understand their unemployment and the type of action or inaction they take as a result.

The word ‘narrative’ is used extensively in health research. It commonly refers to the field of illness narratives, such as accounts of cancer from the patient's perspective ( Frank, 1998 ). The use of words like ‘narrative’ and ‘story’ became more popular in health promotion in the early 1990s as part of an increased emphasis on reflective practice and methods of program evaluation which gave more control to research participants. For example, Dixon argued that storytelling methods were ideally suited to community development projects because the creation of the project's meaning or public representation is placed more in the control of participants, as opposed to external researchers ( Dixon, 1995 ). Storytelling has developed as a training and practice development technique for knowledge development in health promotion ( Centre for Community Development in Health, 1993 ; Labonte et al. , 1999 ).

Thus health promotion was part of what Chamberlayne et al. ( Chamberlayne et al. , 2000 ) referred to as the ‘biographical turn’ in the social sciences. That is, they were part of the larger move towards methods that tap into the personal and social meanings that are considered to be the basis of people's actions. Incorporated within these methods are mechanisms for critical reflection which conceive the individual as the primary sense-making agent in the construction of his/her own identity ( Blumer, 1969 ; Giddens, 1984 , 1991 ; Schwandt, 1998 ). Reflective writing also became a feature within the context of professional development literature ( Schon, 1999 ), and also in education ( Orem, 2001 ), business ( Hartog, 2002 ) and medicine ( Webster, 2002 ).

In our case, narrative inquiry is providing insight into the mechanisms by which community development officers facilitate transformative change among people and organizations, as part of their role to implement a new community-level intervention. We are using narrative inquiry alongside a fleet of methods including self-completed questionnaires, interviews, observation, document analysis and network analysis of inter organizational collaboration patterns ( Hawe et al. , 2004 ).

The intervention, PRISM (Program of Resources, Information and Support for Mothers), is a coordinated and comprehensive primary care and community-based strategy to promote maternal health after childbirth. The study involved 16 local government areas in the state of Victoria, Australia and approximately 20 000 women. The rationale for the intervention and the evidence on which it is based are described by the PRISM designers ( Gunn et al. , 2003 ; Lumley et al. , 2003 ). The intervention is anchored and facilitated in each of the eight intervention communities by a full-time community development officer (CDO) working with a local steering committee for 2 years.

The diaries and interviews

The data are in the form of field diaries and in-depth interviews. Each CDO maintained a field diary over the 2 years of their employment. CDOs were invited to record in it their feelings, thoughts, frustrations, plans and hopes. Agreement to be involved in program documentation was a part of their employment contract with the PRISM research team. Nevertheless the CDOs' agreement to write diaries with the authors (the ‘EcoPRISM team’) was confidential and entirely independent of the PRISM research team. The average field diary consists of approximately 40 000 words of verbatim reflection.

The interview data comprise 34 interviews (in total) undertaken at strategic points of intervention implementation with each CDO. The interviews provided the opportunity for CDOs to talk about what they may have found tedious or difficult to write down. The interviews explored emerging themes within the data. The interviews were tape recorded and transcribed. They were undertaken both over the telephone and face-to-face.

Creating and sustaining the right research conditions for collecting this data was paramount. Unless we could create the right conditions, the CDOs may tell us only part of their story, what they think we want to hear or indeed nothing at all. These conditions encompassed:Creating these conditions in order to gather data in an ethical and principled manner required the researcher (T. R.) to position herself closely with the CDOs. CDOs spent approximately 90 min a week working on program documentation.

Flexibility in how the data were recorded. Some CDOs had electronic diaries. Some were hand written. Some were emails and others were a combination of the three. A couple of CDOs changed recording methods over time.

Adjusting recording methods to suit field conditions.

Empathy to the challenges CDOs faced in implementing the intervention and in their research relationship with us.

Participation in project dissemination. Co-authoring of papers and conference presentations about the project with CDOs.

Trust within the research relationship. By this we mean trust that we would maintain confidentiality and trust that we would represent the CDOs' story accurately.

How narrative analysis differs from thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is common in health promotion research. It involves the open coding of data, i.e. the building of a set of themes to describe the phenomenon of interest by putting ‘like with like’ ( Morse and Field, 1995 ). The researcher looks for patterns in the data, labels them and groups them accordingly ( Strauss, 1987 ). This approach to analysis can stop at the stage of simple listing of themes [e.g. ( Gordon and Turner, 2003 )]. If the development of themes is led by the researcher's a priori interests, some researchers have preferred to use the term ‘template’ analysis ( Crabtree and Miller, 1999 ). On the other hand, if the themes are derived inductively from the data itself then the thematic analysis may be considered to be more close to a grounded theory analysis [e.g. ( Kalnins et al. , 2002 )]. In practice, many researchers in health promotion conduct thematic analyses that reflect both the ideas they bring to the data set beforehand (from the research questions) as well as being open to ‘new’ themes in the data.

Narrative analysis differs from thematic analysis in two interconnected ways. First, narrative analysis focuses more directly on the dynamic ‘in process’ nature of interpretation ( Ezzy, 2002 ). That is, how the interpretations of the CDOs might change with time, with new experiences, and with new and varied social interactions. So, integration of time and context in the construction of meaning is a distinctly narrative characteristic ( Simms, 2003 ). This is something that Ricoeur calls the ‘threefold present’ in which the past and the future co-exist with the present in the mind of the narrator, through memory in the first case and expectation in the second. A thematic analysis might document different themes arising at different stages of the intervention. However, how time drives or potentially transforms the interpretation is integral to the construction of narratives. It is central to the development of narrative types ( Schutz, 1963a , b ), as we describe later.

Second, narrative analysis begins from the stand point of storyteller, or in our case CDO. From here we analyze how people, events, norms and values, organizations, and past histories and future possibilities, are made sense of and incorporated into the storyteller's interpretations and subsequent actions. That is, narrative analysis contextualizes the sense-making process by focusing on the person, rather than a set of themes. This is an important methodological distinction. In analyzing the CDO diaries we attempt to stand in the CDOs' shoes and experience events as they do. As situations, people and events change over time, our vantage point remains the same. In this way we gain unique insights into how they interpret the world. Thematic analysis, in contrast, de-contextualizes the data (e.g. by ‘cutting and pasting’ themes together) to examine the meta or broader issues. Narrative inquiry shares with discourse analysis both a concern for how broader institutional values and cultural norms are expressed in language, and the belief that language is a form of action ( Potter and Wetherell, 1987 ). However, narrative analysis adds further insights into ‘contexts of practice’ because it studies the world through the eyes of one storyteller and applies a theory of time.

Key features of narrative inquiry

Narrative inquiry attempts to understand how people think through events and what they value. We learn this through a close examination of how people talk about events and whose perspectives they draw on to make sense of such events. This may reveal itself in how and when particular events or activities are introduced, how tension is portrayed, and in how judgments are carried out (e.g. the portrayal of right and wrong).

A narrative approach looks closely at the sentences constructed by the storyteller and the information and meaning they portray. The following categories have been adapted from Young ( Young, 1984 ). Are the sentences descriptive? That is, a sentence or paragraph that sets the scene, but has no temporal role in the story. Are they consecutive ? Is there a logic to where the sentence fits into the story? Are they consequential to the story? That is, they have causal implications. If the sentences are evaluative , do they show something of the attitude of the CDO? These sentences give meaning to the story. If they are transformative , they express a change in how the storyteller evaluates something, such as an epiphany.

Narrative inquiry captures how people make sense of the world. This ‘thinking through’ events is presented in the recording of events, such as the extent of detail given. It is also captured in the form of internalized soliloquies ( Athens, 1994 ; Ezzy, 1998 ). These are the conversations one has with oneself or imagined others.

Narrative analysis focuses on who is mentioned in the telling of events (and who is absent) and the role they have in the telling of events. Gergen and Gergen ( Gergen and Gergen, 1984 ) refer to these people as the supporting cast of a person's narrative. As a supporting cast member, they have a purpose or reason for existing in the story. The manner in which the supporting cast are discussed in the field diaries may range from factual accounting of events, to theorizing what that supporting cast member is thinking or doing. Most importantly, who is mentioned in the field diary reveals the people or organizations that are most significant to the CDO in their practice.

Thinking about the context of the storytelling is another important feature of narrative inquiry. Frank ( Frank, 2000 ) refers to the storytelling relation . By this he means that data emerges from within the relation between the teller, the listener and the context of the telling of the story. Storytelling can be a political occasion. Narrative inquiry takes as a given that people may exclude details of events or exaggerate aspects of stories ( Ezzy, 2000 ). What is of analytical interest to the narrative researcher is why these exclusions or exaggerations exist.

On the basis of careful examination of the data, why and how the story is being told, who the supporting cast are and the nature of the storytelling occasion, one can determine the narrative's plot or what the story is about. The plot of a persons' narrative is the organizing theme ( Ezzy, 1998 ) that brings coherence to the telling of events. Events are understood according to the plot. As a result, we can see and understand how a person makes sense of the world.

Finally, the point of the story considers both the organizing theme and the form of the narrative. Form refers to the flow of the narrative over time. Common prototypes are stable, progressive and regressive narratives ( Gergen and Gergen, 1988 ). A stable narrative is one in which the person's evaluations of situations and events remains the same over the course of time. A regressive narrative is one in which these evaluations get worse with time. A progressive narrative is one in which the person's evaluations improve over time. These broad narrative forms are represented in Frye's ( Frye, 1957 ) forms of literary narrative: the tragedy, the comedy, the happy ending, the satire, the romantic saga, etc. It is the inter-relationship of the organizing theme and form that creates what is called ‘coherent directionality’ in the narrative. This means how it makes sense over time.

A complete narrative analysis takes all CDOs and all their stories. It is beyond the scope of this paper to present this in totality here. Instead, to illustrate the insights we are gaining through narrative inquiry, we present two examples of stories below. Table I outlines the narrative approach applied to these two examples. We have also demonstrated the type of themes we could derive from the same quotations if we were to undertake two kinds of thematic analysis, either guided by an a priori interest in program implementation or not. This is presented in Tables II and III .

Example of narrative analysis of two stories

Thematic analysis of two stories: example led by a priori interests

Thematic analysis of two stories: example based on text (free codes) for both stories

The cinema story

I do a lot of my best project work after hours in the supermarket. Friday evening after work was very fruitful in this way. Good conversations with three young mums interested in the project, one who inspired me weeks ago to set up classes at the swimming pool—and then I bumped into the local cinema owner. I had asked him some time ago to think about piloting a Cry Baby program at his cinema, but hadn't got back to him to check. At the bakery counter he said yes! So next week we'll get together to discuss upcoming films, a launch for the first Cry Baby session…

Catching the hairdresser

Ring Sally the hairdresser—catch her at last. She seems interested (though privately always consider that when people are hard to catch and not returning calls it suggests that they may well end up not contributing— my personal theory that, in the end, people contribute to any activity in inverse proportion to the amount of effort involved in contacting them in the first place) so send her again details of Project and [voucher] contract.

As demonstrated in Table I narrative analysis can be applied to short, very specific stories. We have applied these steps to the entire CDO data set in order to identify the main plots to each of the CDO narratives. Then, through a process of comparison between each of the narratives, a narrative typology or model of ideal types (of narratives) has been created, understood from a phenomenological point of view ( Schutz, 1963a , b ). This means comparing each of the organizing themes for similarities and differences regarding their interpretative framework. By placing each narrative theme under scrutiny, we find that some plots are very similar in nature (form and theme), while others stand out as different. In this way we hope to be able to put forward some of the defining characteristics of practice in the context we have researched, that is, experienced community development practitioners working within the context of a community intervention trial.

The assumption that we bring to this work is that a better understanding of intervention dynamics and indigenous theory may lead to fewer failed community interventions ( Thompson et al. , 2003 ). Because our PRISM trial collaborators are conducting a traditional process evaluation ( Lumley et al. , 2003 ), focused on the program elements, we will be able to determine how a different way of describing intervention unfolding sheds additional light on the ‘black box’ of the intervention. Our interpretations will also be linked to the burgeoning field of implementation analysis ( Ottoson et al. , 1987 ; Bauman, 1991 ; Bammer, 2003 ). This field argues that we need to move beyond mechanistic ways of viewing interventions [e.g. ( Flora et al. , 1993 )] to encompass new methods better suited to the complexity of the personal, organizational and community change processes that interventions purport to bring about.

A primary weakness of narrative inquiry is that it is retrospective. So the length of time required for analysis and presentation of results can be a disincentive. For this reason, fine-tuning narrative methods is a major challenge for future work. Hence, we relied on thematic analysis in order to feedback data that might be timely and important for fine-tuning the intervention in progress ( Riley et al. , 2004 ). However, the narrative analysis takes us much further into the private world of the practitioner and helps us (re)think what the intervention represents. It helps us understand the intensely personal investments being made by CDOs in the project. This is revealed in the CDO's placement of ‘self’ in the narrative. We learn about the progressive or regressive trade-offs, risks and rewards. This provides the social context to allow us to better interpret project dynamics and tensions. For example, the stakes involved when different opinions arose regarding how far PRISM could be adapted to suit local context ( Riley et al. , 2004 ).

Riger ( Riger, 1989 ) argues that some of the most important (but typically untold) stories within community interventions are about the power dynamics, i.e. what gets said publicly about the intervention and why. Our analysis thus far privileges the perspective of the CDO. However, another data set in our study, key informant interviews held in each community at the end of the intervention, will allow us to challenge or confirm these views. This includes members of the steering committees (i.e. some of the ‘supporting cast’).

Narrative analysis requires an in-depth engagement with and understanding of the participant's experience. As a result, there is a blurring of interpretive boundaries between the analyst and the research participant. Such a blurring results in two distinct criticisms of narrative analysis. One is that the analyst can play too strong an interpretative role without sufficient links back to empirical data ( Atkinson, 1997 ). The other criticism is that the analyst plays too weak an interpretive role. Atkinson ( Atkinson, 1997 ) argues that within some forms of narrative analysis there is a lack of analytical attention to social context and interaction, subsequently celebrating, rather than analyzing, the research participant's stories. Researchers are likely to be open to such criticism when unable to define and defend the interpretive framework that is being applied to interrogate the data.

Narrative inquiry encourages the analyst to consider what is in the data set and also what is not there, such as missing characters or alternative viewpoints. This makes the systematic ‘coding’ of data extremely difficult ( Rice and Ezzy, 1999 ) and affirms the importance of a guiding set of analytical principles with which to interrogate the data. Introspective reflexivity is critical in this regard ( Finlay, 2003 ). By this we mean that researchers must interrogate the dynamic created between the researcher and ‘the researched’ and devise accountability mechanisms. In this way the researchers' location and representation within the study is a key component of both data collection and analysis and we have drawn on insights from ethnography in this regard ( Michalowski, 1997 ; Reinharz, 1997 ; McCorkel and Myers, 2003 ). The challenges arising from our research context have been explored in a series of presentations and publications we have pursued with CDOs ( Riley and Hawe, 2000 , 2001 , 2002 ; Riley et al. , 2001 ; Sanders et al. , 2001 ). For an exploration of the ethical challenges we faced, see Riley et al. ( Riley et al. , 2004 ).

Our data set is unique. We know of no other large-scale intervention studies using narrative methods to understand practice contexts. CDOs told us that, overall, writing about their experience helped. It enabled their viewpoints to be articulated and better heard. We hope that by describing our narrative approach we will encourage other researchers to investigate the opportunity provided by narrative inquiry in everyday practice and in intervention study contexts.

We are indebted to the CDOs (Wendy Arney, Deborah Brown, Kay Dufty, Serena Everill, Annie Lanyon, Melanie Sanders, Leanne Skipsey, Jennifer Stone and Scilla Taylor) for their willingness to engage with us and to share their reflections on their use of diaries. The PRISM research trial team is Judith Lumley, Rhonda Small, Stephanie Brown, Lyn Watson, Wendy Dawson, Jane Gunn and Creina Mitchell. Our thanks to them for the opportunity to participate as collaborators in the trial. The EcoPRISM study is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia. P. H. is a Senior Scholar of the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, Canada and holds the Markin Chair in Health and Society at the University of Calgary.

Athens, L. ( 1994 ) The self as a soliloquy. Sociological Quarterly , 35 , 521 –532.

Atkinson, P. ( 1997 ) Narrative turn or blind alley. Qualitative Health Research , 7 , 325 –344.

Bammer, G. ( 2003 ) Integration and implementation sciences: building a new specialisation. Available: http://www.anu.edu.au//iisn ; retrieved: 13 September 2003.

Bauman, L.J., Stein, R.E.K. and Ireys, H.T. ( 1991 ) Reinventing fidelity: the transfer of social technology among settings. American Journal of Community Psychology , 19 , 619 –639.

Blumer, H. ( 1969 ) Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method . Prentice-Hill, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Centre for Community Development in Health ( 1993 ) Case Studies of Community Development in Health. Centre for Community Development in Health, Melbourne.

Chamberlayne, P., Bornat, J. and Wengraf, T. ( 2000 ) Introduction: the biographical turn. In Chamberlayne, P., Bornat, J. and Wengraf, T. (eds), The Turn to Biographical Methods in Social Science . Routledge, London, pp. 1–30.

Crabtree, B.F. and Miller, W.L. ( 1999 ) Using codes and code manuals: a template organizing style of interpretation. In Crabtree, B.F. and Miller, W.L. (eds), Doing Qualitative Research , 2ne edn. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Dixon, J. ( 1995 ) Community stories and indicators for evaluating community development. Community Development Journal , 30 , 327 –336.

Ezzy, D. ( 1998 ) Theorizing narrative Identity: symbolic interactionism and hermeneutics. The Sociological Quarterly , 39 , 239 –263.

Ezzy, D. ( 2000 ) Fate and agency in job loss narratives, Qualitative Sociology , 23 , 121 –134.

Ezzy, D. ( 2002 ) Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Innovation . Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

Finlay, L. ( 2003 ) The Reflexive journey: mapping multiple routes. In Finlay, L. and Gough, B. (eds), Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences . Blackwell, Oxford.

Flora, J.A., Lefebvre, R.C., Murray, D.M., Stone, E.J., Assaf, A., Mittelmark, M.B. and Finnegan, J.R. Jr. ( 1993 ) A community education monitoring system: methods from the Stanford Five-City Project, the Minnesota Heart Health Program and the Pawtucket Heart Health Program. Health Education Research , 8 , 81 –95.

Frank, A. ( 1998 ) Just listening: narrative and deep illness. Families, Systems and Health , 16 , 197 –212.

Frank, A. ( 2000 ) The standpoint of storyteller. Qualitative Health Research , 10 , 354 –365.

Frye, N. ( 1957 ) Anatomy of Criticism . Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Gergen, K. and Gergen, M. ( 1988 ) Narrative and the self as relationship. Advances in Environmental Social Psychology , 21 , 17 –56.

Gergen, M. and Gergen, K. ( 1984 ) The social construction of narrative accounts. In Gergen, M. and Gergen, K. (eds), Historical Social Psychology . Lawrence Erlbaum, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Giddens, A. ( 1984 ) The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration . Polity Press, Cambridge.

Giddens, A. ( 1991 ) Modernity and Self Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age . Polity Press, Cambridge.

Glanz, K., Lewis, F.M. and Rimer, B.K. (eds) ( 1990 ) Health Education and Health Behavior: Theory, Research and Practice. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Goodman, R.M., Steckler, A., Hoover, S. and Schwartz, R. ( 1993 ) A critique of contemporary community health promotion approaches based on a qualitative review of six programs in Maine. American Journal of Health Promotion , 7 , 208 –220.

Gordon, K. and Turner, K.M. ( 2003 ) Ifs, maybes and butts: factors influencing staff enforcement of pupil smoking restrictions. Health Education Research , 18 , 329 –340.

Gunn, J., Southern, D., Chondros, P., Thomson, P. and Robertson, K. ( 2003 ) Guidelines for assessing postnatal problems: introducing evidence based guidelines in Australian general practice. Family Practice , 20 , 382 –389.

Hartog, M. ( 2002 ) Becoming a reflective practitioner: a continuing professional development strategy through humanistic action research. Business Ethics: A European Review , 11 , 233 –243.

Hawe, P., King, L., Noort, M., Gifford, S.M. and Lloyd, B. ( 1998 ) Working invisibly: health workers talk about capacity-building in health promotion. Health Promotion International , 13 , 285 –295.

Hawe, P., Shiell, A., Riley, T. and Gold, L. ( 2004 ) Methods for exploring implementation variation and local context within a cluster randomized community intervention trial. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health , 58 , 788 –793.

Kalnins, I., Hart, C., Ballantyne, P., Quartaro, G., Love, R., Sturis, G. and Pollack, P. ( 2002 ) Children's perceptions of strategies for resolving community health problems. Health Promotion International , 17 , 223 –233.

Labonte, R., Feather, J. and Hills, M. ( 1999 ) A story/dialogue method for health promotion knowledge development and evaluation. Health Education Research , 14 , 39 –50.

Lumley, J., Small, R., Brown, S., Watson, L., Gunn, J., Mitchell, C. and Dawson, W. ( 2003 ) PRISM (Program of Resources, Information and Support for Mothers) Protocol for a community-randomised trial [ISRCTN03464021]. BMC Public Health , 3 , 36 .

Manning, P. and Cullum-Swan, B. ( 1998 ) Narrative, content and semiotic analysis. In Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y. (eds), Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials , Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 221–259.

McCorkel, J. and Myers, K. ( 2003 ) What difference does difference make: position and privilege in the field. Qualitative Sociology , 26 , 199 –251.

Michalowski, R.A. ( 1997 ) Ethnology and anxiety: field work and reflexivity in the vortex of US–Cuban relations. In Hertz, R. (ed.), Reflexivity and Voice. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 45–69.

Mishler, E. ( 1995 ) Models of narrative analysis: a typology. Journal of Narrative and Life History , 5 , 87 –123.

Morse, J.M. and Field, P.A. ( 1995 ) Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals . Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Orem, R. ( 2001 ) Journal writing in adult ESL: improving practice through reflective writing. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education , 90 , 69 –77.

Ottoson, J.M. and Green, L.W. ( 1987 ) Reconciling concept and context: theory of implementation. Advances in Health Education and Promotion , 2 , 353 –382.

Patton, M.Q. ( 1990 ) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods , 2nd edn. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Poland, B., Rootman, I. and Green, L.W. (eds) ( 2000 ) Settings for Health Promotion. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Potter, J. and Wetherell, M. ( 1987 ) Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour . Sage, London.

Reinharz, S. ( 1997 ) Who am I? The need for a variety of selves in the field. In Hertz, R. (ed.), Reflexivity and Voice. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 3–20.

Rice, P.L. and Ezzy, D. ( 1999 ) Qualitative Research Methods . Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ricoeur, P. ( 1980 ) Narrative time. Critical Inquiry , 7 , 160 –190.

Riessman, C. ( 1993 ) Narrative Analysis (Qualitative Research Methods Series 30) . Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Riger, S. ( 1989 ) The politics of community intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology , 17 , 379 –383.

Riley, T. and Hawe P. ( 2000 ) Researcher as subject: searching for ethical guidance within a cluster randomised community intervention trial. Paper presented to Social Science Methodology in the New Millennium, 5th International Conference on Logic and Methodology . University of Cologne, October.

Riley, T. and Hawe P. ( 2001 ) It's story time: the dilemmas of narrative construction. Paper presented to The Australasian Sociological Association (TASA) Conference , Sydney, December.

Riley, T. and Hawe, P. ( 2002 ) Narratives of practice: telling the stories of health program fieldworkers. Paper presented to World Congress of Sociology , Brisbane, July.

Riley, T., Sanders, M., Taylor, S., Stone, J., Skipsey, L., Everill, S., Dufty, K., Arney, W. and Brown, D. ( 2001 ) Who is being researched? Paper presented to Critical Issues in Qualitative Research, 2nd International Conference. Melbourne, July.

Riley, T., Hawe, P. and Shiell, A. ( 2004 ) Contested ground: how should qualitative evidence inform the conduct of a community intervention trial? Journal of Health Services Research and Policy , in press.

Sanders, M., Dufty, K., Arney, W., Riley, T. and Everill, S. ( 2001 ) Rewarding intelligent failure. Paper presented to 13th Australian Health Promotion National Conference , Queensland, June.

Schegloff, E. ( 1997 ) ‘Narrative analysis’ thirty years later. Journal of Narrative and Life History , 7 , 97 –106.

Schon, D. ( 1999 ) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action . Ashgate, London.

Schutz, A. ( 1963 a) Concept and theory formation in the social sciences. In Natanson, M. (ed), Philosophy of the Social Sciences . Random House, New York, pp. 231–249.

Schutz, A. ( 1963 b) Common sense and scientific interpretation of human action. In Natanson, M. (ed.), Philosophy of the Social Sciences . Random House, New York, pp. 302–346.

Schwandt, T. ( 1998 ) Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. In Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y. (eds), The Landscape of Qualitative Research Theoretical Issues . Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 221–259.

Simms, K. ( 2003 ) Paul Ricoeur . Routledge, London.

Strauss, A. ( 1987 ) Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Thompson, B., Coronado, G., Snipes, S.A. and Puschel, K. ( 2003 ) Methodological advances and ongoing challenges in designing community based health promotion interventions. Annual Review of Public Health , 24 , 315 –340.

Tudor-Smith, C., Nutbeam, D., Moore, L. and Catford, J. ( 1998 ) Effects of the Heartbeat Wales programme over five years on behavioural risks for cardiovascular disease: quasi-experimental comparison of results from Wales and a matched reference area. British Medical Journal , 316 , 818 –822.

Trickett, E. ( 1998 ) Toward a framework for defining and resolving ethical issues in the protection of communities involved in primary prevention projects. Ethics and Behaviour , 8 , 321 –337.

Webster, J. ( 2002 ) Using reflective writing to gain insight into practice with older people. Nursing Older People , 14 , 18 –21.

Young, K. G. ( 1984 ) Ontological puzzles about narrative. Poetics , 13 , 239 –259.

Author notes

1VicHealth Centre for the Promotion of Mental Health and Social Wellbeing, School of Population Health, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia (Formerly at the Centre for the Study of Mothers' and Children's Health, LaTrobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia), 2Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N 4N1, Canada and 3School of Public Health, LaTrobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS