Motivation Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on motivation.

Everyone suggests other than the person lack motivation, or directly suggests the person remain motivated. But, no one ever tells what is the motivation of how one can stay motivated. Motivation means to face the obstacle and find an inspiration that helps you to go through tough times. In addition, it helps you to move further in life.

Meaning of Motivation

Motivation is something that cannot be understood with words but with practice. It means to be moved by something so strongly that it becomes an inspiration for you. Furthermore, it is a discipline that helps you to achieve your life goals and also helps to be successful in life .

Besides, it the most common practice that everyone does whether it is your boss in office or a school teacher or a university professor everyone motivates others in a way or other.

Role of Motivation

It is a strong tool that helps to get ahead in life. For being motivated we need a driving tool or goal that keeps us motivated and moves forward. Also, it helps in being progressive both physically and mentally.

Moreover, your goal does not be to big and long term they can be small and empowering. Furthermore, you need the right mindset to be motivated.

Besides, you need to push your self towards your goal no one other than you can push your limit. Also, you should be willing to leave your comfort zone because your true potential is going to revel when you leave your comfort zone.

Types of Motivation

Although there are various types of motivation according to me there are generally two types of motivation that are self- motivation and motivation by others.

Self-motivation- It refers to the power of someone to stay motivated without the influence of other situations and people. Furthermore, self-motivated people always find a way to reason and strength to complete a task. Also, they do not need other people to encourage them to perform a challenging task.

Motivation by others- This motivation requires help from others as the person is not able to maintain a self-motivated state. In this, a person requires encouragement from others. Also, he needs to listen to motivational speeches, a strong goal and most importantly and inspiration.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Importance of Motivation

Motivation is very important for the overall development of the personality and mind of the people. It also puts a person in action and in a competitive state. Furthermore, it improves efficiency and desire to achieve the goal. It leads to stability and improvement in work.

Above all, it satisfies a person’s needs and to achieve his/her goal. It helps the person to fight his negative attitude. The person also tries to come out of his/her comfort zone so that she/ he can achieve the goal.

To conclude, motivation is one of the key elements that help a person to be successful. A motivated person tries to push his limits and always tries to improve his performance day by day. Also, the person always gives her/his best no matter what the task is. Besides, the person always tries to remain progressive and dedicated to her/his goals.

FAQs about Motivation Essay

Q.1 Define what is motivation fit. A.1 This refers to a psychological phenomenon in which a person assumes or expects something from the job or life but gets different results other than his expectations. In a profession, it is a primary criterion for determining if the person will stay or leave the job.

Q.2 List some best motivators. A.2 some of the best motivators are:

- Inspiration

- Fear of failure

- Power of Rejection

- Don’t pity your self

- Be assertive

- Stay among positive and motivated people

- Be calm and visionary

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

- Teaching Sustainability

- Teaching Social Justice

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

- Student Writing Lessons

- Visual Learning Lessons

- Tough Topics Discussion Guides

- About the YES! for Teachers Program

- Student Writing Contest

Follow YES! For Teachers

Eight brilliant student essays on what matters most in life.

Read winning essays from our spring 2019 student writing contest.

For the spring 2019 student writing contest, we invited students to read the YES! article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age” by Nancy Hill. Like the author, students interviewed someone significantly older than them about the three things that matter most in life. Students then wrote about what they learned, and about how their interviewees’ answers compare to their own top priorities.

The Winners

From the hundreds of essays written, these eight were chosen as winners. Be sure to read the author’s response to the essay winners and the literary gems that caught our eye. Plus, we share an essay from teacher Charles Sanderson, who also responded to the writing prompt.

Middle School Winner: Rory Leyva

High School Winner: Praethong Klomsum

University Winner: Emily Greenbaum

Powerful Voice Winner: Amanda Schwaben

Powerful Voice Winner: Antonia Mills

Powerful Voice Winner: Isaac Ziemba

Powerful Voice Winner: Lily Hersch

“Tell It Like It Is” Interview Winner: Jonas Buckner

From the Author: Response to Student Winners

Literary Gems

From A Teacher: Charles Sanderson

From the Author: Response to Charles Sanderson

Middle School Winner

Village Home Education Resource Center, Portland, Ore.

The Lessons Of Mortality

“As I’ve aged, things that are more personal to me have become somewhat less important. Perhaps I’ve become less self-centered with the awareness of mortality, how short one person’s life is.” This is how my 72-year-old grandma believes her values have changed over the course of her life. Even though I am only 12 years old, I know my life won’t last forever, and someday I, too, will reflect on my past decisions. We were all born to exist and eventually die, so we have evolved to value things in the context of mortality.

One of the ways I feel most alive is when I play roller derby. I started playing for the Rose City Rollers Juniors two years ago, and this year, I made the Rosebud All-Stars travel team. Roller derby is a fast-paced, full-contact sport. The physicality and intense training make me feel in control of and present in my body.

My roller derby team is like a second family to me. Adolescence is complicated. We understand each other in ways no one else can. I love my friends more than I love almost anything else. My family would have been higher on my list a few years ago, but as I’ve aged it has been important to make my own social connections.

Music led me to roller derby. I started out jam skating at the roller rink. Jam skating is all about feeling the music. It integrates gymnastics, breakdancing, figure skating, and modern dance with R & B and hip hop music. When I was younger, I once lay down in the DJ booth at the roller rink and was lulled to sleep by the drawl of wheels rolling in rhythm and people talking about the things they came there to escape. Sometimes, I go up on the roof of my house at night to listen to music and feel the wind rustle my hair. These unique sensations make me feel safe like nothing else ever has.

My grandma tells me, “Being close with family and friends is the most important thing because I haven’t

always had that.” When my grandma was two years old, her father died. Her mother became depressed and moved around a lot, which made it hard for my grandma to make friends. Once my grandma went to college, she made lots of friends. She met my grandfather, Joaquin Leyva when she was working as a park ranger and he was a surfer. They bought two acres of land on the edge of a redwood forest and had a son and a daughter. My grandma created a stable family that was missing throughout her early life.

My grandma is motivated to maintain good health so she can be there for her family. I can relate because I have to be fit and strong for my team. Since she lost my grandfather to cancer, she realizes how lucky she is to have a functional body and no life-threatening illnesses. My grandma tries to eat well and exercise, but she still struggles with depression. Over time, she has learned that reaching out to others is essential to her emotional wellbeing.

Caring for the earth is also a priority for my grandma I’ve been lucky to learn from my grandma. She’s taught me how to hunt for fossils in the desert and find shells on the beach. Although my grandma grew up with no access to the wilderness, she admired the green open areas of urban cemeteries. In college, she studied geology and hiked in the High Sierras. For years, she’s been an advocate for conserving wildlife habitat and open spaces.

Our priorities may seem different, but it all comes down to basic human needs. We all desire a purpose, strive to be happy, and need to be loved. Like Nancy Hill says in the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” it can be hard to decipher what is important in life. I believe that the constant search for satisfaction and meaning is the only thing everyone has in common. We all want to know what matters, and we walk around this confusing world trying to find it. The lessons I’ve learned from my grandma about forging connections, caring for my body, and getting out in the world inspire me to live my life my way before it’s gone.

Rory Leyva is a seventh-grader from Portland, Oregon. Rory skates for the Rosebuds All-Stars roller derby team. She loves listening to music and hanging out with her friends.

High School Winner

Praethong Klomsum

Santa Monica High School, Santa Monica, Calif.

Time Only Moves Forward

Sandra Hernandez gazed at the tiny house while her mother’s gentle hands caressed her shoulders. It wasn’t much, especially for a family of five. This was 1960, she was 17, and her family had just moved to Culver City.

Flash forward to 2019. Sandra sits in a rocking chair, knitting a blanket for her latest grandchild, in the same living room. Sandra remembers working hard to feed her eight children. She took many different jobs before settling behind the cash register at a Japanese restaurant called Magos. “It was a struggle, and my husband Augustine, was planning to join the military at that time, too.”

In the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” author Nancy Hill states that one of the most important things is “…connecting with others in general, but in particular with those who have lived long lives.” Sandra feels similarly. It’s been hard for Sandra to keep in contact with her family, which leaves her downhearted some days. “It’s important to maintain that connection you have with your family, not just next-door neighbors you talk to once a month.”

Despite her age, Sandra is a daring woman. Taking risks is important to her, and she’ll try anything—from skydiving to hiking. Sandra has some regrets from the past, but nowadays, she doesn’t wonder about the “would have, could have, should haves.” She just goes for it with a smile.

Sandra thought harder about her last important thing, the blue and green blanket now finished and covering

her lap. “I’ve definitely lived a longer life than most, and maybe this is just wishful thinking, but I hope I can see the day my great-grandchildren are born.” She’s laughing, but her eyes look beyond what’s in front of her. Maybe she is reminiscing about the day she held her son for the first time or thinking of her grandchildren becoming parents. I thank her for her time and she waves it off, offering me a styrofoam cup of lemonade before I head for the bus station.

The bus is sparsely filled. A voice in my head reminds me to finish my 10-page history research paper before spring break. I take a window seat and pull out my phone and earbuds. My playlist is already on shuffle, and I push away thoughts of that dreaded paper. Music has been a constant in my life—from singing my lungs out in kindergarten to Barbie’s “I Need To Know,” to jamming out to Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space” in sixth grade, to BTS’s “Intro: Never Mind” comforting me when I’m at my lowest. Music is my magic shop, a place where I can trade away my fears for calm.

I’ve always been afraid of doing something wrong—not finishing my homework or getting a C when I can do better. When I was 8, I wanted to be like the big kids. As I got older, I realized that I had exchanged my childhood longing for the 48 pack of crayons for bigger problems, balancing grades, a social life, and mental stability—all at once. I’m going to get older whether I like it or not, so there’s no point forcing myself to grow up faster. I’m learning to live in the moment.

The bus is approaching my apartment, where I know my comfy bed and a home-cooked meal from my mom are waiting. My mom is hard-working, confident, and very stubborn. I admire her strength of character. She always keeps me in line, even through my rebellious phases.

My best friend sends me a text—an update on how broken her laptop is. She is annoying. She says the stupidest things and loves to state the obvious. Despite this, she never fails to make me laugh until my cheeks feel numb. The rest of my friends are like that too—loud, talkative, and always brightening my day. Even friends I stopped talking to have a place in my heart. Recently, I’ve tried to reconnect with some of them. This interview was possible because a close friend from sixth grade offered to introduce me to Sandra, her grandmother.

I’m decades younger than Sandra, so my view of what’s important isn’t as broad as hers, but we share similar values, with friends and family at the top. I have a feeling that when Sandra was my age, she used to love music, too. Maybe in a few decades, when I’m sitting in my rocking chair, drawing in my sketchbook, I’ll remember this article and think back fondly to the days when life was simple.

Praethong Klomsum is a tenth-grader at Santa Monica High School in Santa Monica, California. Praethong has a strange affinity for rhyme games and is involved in her school’s dance team. She enjoys drawing and writing, hoping to impact people willing to listen to her thoughts and ideas.

University Winner

Emily Greenbaum

Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

The Life-Long War

Every morning we open our eyes, ready for a new day. Some immediately turn to their phones and social media. Others work out or do yoga. For a certain person, a deep breath and the morning sun ground him. He hears the clink-clank of his wife cooking low sodium meat for breakfast—doctor’s orders! He sees that the other side of the bed is already made, the dogs are no longer in the room, and his clothes are set out nicely on the loveseat.

Today, though, this man wakes up to something different: faded cream walls and jello. This person, my hero, is Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James.

I pulled up my chair close to Roger’s vinyl recliner so I could hear him above the noise of the beeping dialysis machine. I noticed Roger would occasionally glance at his wife Susan with sparkly eyes when he would recall memories of the war or their grandkids. He looked at Susan like she walked on water.

Roger James served his country for thirty years. Now, he has enlisted in another type of war. He suffers from a rare blood cancer—the result of the wars he fought in. Roger has good and bad days. He says, “The good outweighs the bad, so I have to be grateful for what I have on those good days.”

When Roger retired, he never thought the effects of the war would reach him. The once shallow wrinkles upon his face become deeper, as he tells me, “It’s just cancer. Others are suffering from far worse. I know I’ll make it.”

Like Nancy Hill did in her article “Three Things that Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I asked Roger, “What are the three most important things to you?” James answered, “My wife Susan, my grandkids, and church.”

Roger and Susan served together in the Vietnam war. She was a nurse who treated his cuts and scrapes one day. I asked Roger why he chose Susan. He said, “Susan told me to look at her while she cleaned me up. ‘This may sting, but don’t be a baby.’ When I looked into her eyes, I felt like she was looking into my soul, and I didn’t want her to leave. She gave me this sense of home. Every day I wake up, she makes me feel the same way, and I fall in love with her all over again.”

Roger and Susan have two kids and four grandkids, with great-grandchildren on the way. He claims that his grandkids give him the youth that he feels slowly escaping from his body. This adoring grandfather is energized by coaching t-ball and playing evening card games with the grandkids.

The last thing on his list was church. His oldest daughter married a pastor. Together they founded a church. Roger said that the connection between his faith and family is important to him because it gave him a reason to want to live again. I learned from Roger that when you’re across the ocean, you tend to lose sight of why you are fighting. When Roger returned, he didn’t have the will to live. Most days were a struggle, adapting back into a society that lacked empathy for the injuries, pain, and psychological trauma carried by returning soldiers. Church changed that for Roger and gave him a sense of purpose.

When I began this project, my attitude was to just get the assignment done. I never thought I could view Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James as more than a role model, but he definitely changed my mind. It’s as if Roger magically lit a fire inside of me and showed me where one’s true passions should lie. I see our similarities and embrace our differences. We both value family and our own connections to home—his home being church and mine being where I can breathe the easiest.

Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James has shown me how to appreciate what I have around me and that every once in a while, I should step back and stop to smell the roses. As we concluded the interview, amidst squeaky clogs and the stale smell of bleach and bedpans, I looked to Roger, his kind, tired eyes, and weathered skin, with a deeper sense of admiration, knowing that his values still run true, no matter what he faces.

Emily Greenbaum is a senior at Kent State University, graduating with a major in Conflict Management and minor in Geography. Emily hopes to use her major to facilitate better conversations, while she works in the Washington, D.C. area.

Powerful Voice Winner

Amanda Schwaben

Wise Words From Winnie the Pooh

As I read through Nancy Hill’s article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I was comforted by the similar responses given by both children and older adults. The emphasis participants placed on family, social connections, and love was not only heartwarming but hopeful. While the messages in the article filled me with warmth, I felt a twinge of guilt building within me. As a twenty-one-year-old college student weeks from graduation, I honestly don’t think much about the most important things in life. But if I was asked, I would most likely say family, friendship, and love. As much as I hate to admit it, I often find myself obsessing over achieving a successful career and finding a way to “save the world.”

A few weeks ago, I was at my family home watching the new Winnie the Pooh movie Christopher Robin with my mom and younger sister. Well, I wasn’t really watching. I had my laptop in front of me, and I was aggressively typing up an assignment. Halfway through the movie, I realized I left my laptop charger in my car. I walked outside into the brisk March air. Instinctively, I looked up. The sky was perfectly clear, revealing a beautiful array of stars. When my twin sister and I were in high school, we would always take a moment to look up at the sparkling night sky before we came into the house after soccer practice.

I think that was the last time I stood in my driveway and gazed at the stars. I did not get the laptop charger from

my car; instead, I turned around and went back inside. I shut my laptop and watched the rest of the movie. My twin sister loves Winnie the Pooh. So much so that my parents got her a stuffed animal version of him for Christmas. While I thought he was adorable and a token of my childhood, I did not really understand her obsession. However, it was clear to me after watching the movie. Winnie the Pooh certainly had it figured out. He believed that the simple things in life were the most important: love, friendship, and having fun.

I thought about asking my mom right then what the three most important things were to her, but I decided not to. I just wanted to be in the moment. I didn’t want to be doing homework. It was a beautiful thing to just sit there and be present with my mom and sister.

I did ask her, though, a couple of weeks later. Her response was simple. All she said was family, health, and happiness. When she told me this, I imagined Winnie the Pooh smiling. I think he would be proud of that answer.

I was not surprised by my mom’s reply. It suited her perfectly. I wonder if we relearn what is most important when we grow older—that the pressure to be successful subsides. Could it be that valuing family, health, and happiness is what ends up saving the world?

Amanda Schwaben is a graduating senior from Kent State University with a major in Applied Conflict Management. Amanda also has minors in Psychology and Interpersonal Communication. She hopes to further her education and focus on how museums not only preserve history but also promote peace.

Antonia Mills

Rachel Carson High School, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Decoding The Butterfly

For a caterpillar to become a butterfly, it must first digest itself. The caterpillar, overwhelmed by accumulating tissue, splits its skin open to form its protective shell, the chrysalis, and later becomes the pretty butterfly we all know and love. There are approximately 20,000 species of butterflies, and just as every species is different, so is the life of every butterfly. No matter how long and hard a caterpillar has strived to become the colorful and vibrant butterfly that we marvel at on a warm spring day, it does not live a long life. A butterfly can live for a year, six months, two weeks, and even as little as twenty-four hours.

I have often wondered if butterflies live long enough to be blissful of blue skies. Do they take time to feast upon the sweet nectar they crave, midst their hustling life of pollinating pretty flowers? Do they ever take a lull in their itineraries, or are they always rushing towards completing their four-stage metamorphosis? Has anyone asked the butterfly, “Who are you?” instead of “What are you”? Or, How did you get here, on my windowsill? How did you become ‘you’?

Humans are similar to butterflies. As a caterpillar

Suzanna Ruby/Getty Images

becomes a butterfly, a baby becomes an elder. As a butterfly soars through summer skies, an elder watches summer skies turn into cold winter nights and back toward summer skies yet again. And as a butterfly flits slowly by the porch light, a passerby makes assumptions about the wrinkled, slow-moving elder, who is sturdier than he appears. These creatures are not seen for who they are—who they were—because people have “better things to do” or they are too busy to ask, “How are you”?

Our world can be a lonely place. Pressured by expectations, haunted by dreams, overpowered by weakness, and drowned out by lofty goals, we tend to forget ourselves—and others. Rather than hang onto the strands of our diminishing sanity, we might benefit from listening to our elders. Many elders have experienced setbacks in their young lives. Overcoming hardship and surviving to old age is wisdom that they carry. We can learn from them—and can even make their day by taking the time to hear their stories.

Nancy Hill, who wrote the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” was right: “We live among such remarkable people, yet few know their stories.” I know a lot about my grandmother’s life, and it isn’t as serene as my own. My grandmother, Liza, who cooks every day, bakes bread on holidays for our neighbors, brings gifts to her doctor out of the kindness of her heart, and makes conversation with neighbors even though she is isn’t fluent in English—Russian is her first language—has struggled all her life. Her mother, Anna, a single parent, had tuberculosis, and even though she had an inviolable spirit, she was too frail to care for four children. She passed away when my grandmother was sixteen, so my grandmother and her siblings spent most of their childhood in an orphanage. My grandmother got married at nineteen to my grandfather, Pinhas. He was a man who loved her more than he loved himself and was a godsend to every person he met. Liza was—and still is—always quick to do what was best for others, even if that person treated her poorly. My grandmother has lived with physical pain all her life, yet she pushed herself to climb heights that she wasn’t ready for. Against all odds, she has lived to tell her story to people who are willing to listen. And I always am.

I asked my grandmother, “What are three things most important to you?” Her answer was one that I already expected: One, for everyone to live long healthy lives. Two, for you to graduate from college. Three, for you to always remember that I love you.

What may be basic to you means the world to my grandmother. She just wants what she never had the chance to experience: a healthy life, an education, and the chance to express love to the people she values. The three things that matter most to her may be so simple and ordinary to outsiders, but to her, it is so much more. And who could take that away?

Antonia Mills was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York and attends Rachel Carson High School. Antonia enjoys creative activities, including writing, painting, reading, and baking. She hopes to pursue culinary arts professionally in the future. One of her favorite quotes is, “When you start seeing your worth, you’ll find it harder to stay around people who don’t.” -Emily S.P.

Powerful Voice Winner

Isaac Ziemba

Odyssey Multiage Program, Bainbridge Island, Wash.

This Former State Trooper Has His Priorities Straight: Family, Climate Change, and Integrity

I have a personal connection to people who served in the military and first responders. My uncle is a first responder on the island I live on, and my dad retired from the Navy. That was what made a man named Glen Tyrell, a state trooper for 25 years, 2 months and 9 days, my first choice to interview about what three things matter in life. In the YES! Magazine article “The Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I learned that old and young people have a great deal in common. I know that’s true because Glen and I care about a lot of the same things.

For Glen, family is at the top of his list of important things. “My wife was, and is, always there for me. My daughters mean the world to me, too, but Penny is my partner,” Glen said. I can understand why Glen’s wife is so important to him. She’s family. Family will always be there for you.

Glen loves his family, and so do I with all my heart. My dad especially means the world to me. He is my top supporter and tells me that if I need help, just “say the word.” When we are fishing or crabbing, sometimes I

think, what if these times were erased from my memory? I wouldn’t be able to describe the horrible feeling that would rush through my mind, and I’m sure that Glen would feel the same about his wife.

My uncle once told me that the world is always going to change over time. It’s what the world has turned out to be that worries me. Both Glen and I are extremely concerned about climate change and the effect that rising temperatures have on animals and their habitats. We’re driving them to extinction. Some people might say, “So what? Animals don’t pay taxes or do any of the things we do.” What we are doing to them is like the Black Death times 100.

Glen is also frustrated by how much plastic we use and where it ends up. He would be shocked that an explorer recently dived to the deepest part of the Pacific Ocean—seven miles!— and discovered a plastic bag and candy wrappers. Glen told me that, unfortunately, his generation did the damage and my generation is here to fix it. We need to take better care of Earth because if we don’t, we, as a species, will have failed.

Both Glen and I care deeply for our families and the earth, but for our third important value, I chose education and Glen chose integrity. My education is super important to me because without it, I would be a blank slate. I wouldn’t know how to figure out problems. I wouldn’t be able to tell right from wrong. I wouldn’t understand the Bill of Rights. I would be stuck. Everyone should be able to go to school, no matter where they’re from or who they are. It makes me angry and sad to think that some people, especially girls, get shot because they are trying to go to school. I understand how lucky I am.

Integrity is sacred to Glen—I could tell by the serious tone of Glen’s voice when he told me that integrity was the code he lived by as a former state trooper. He knew that he had the power to change a person’s life, and he was committed to not abusing that power. When Glen put someone under arrest—and my uncle says the same—his judgment and integrity were paramount. “Either you’re right or you’re wrong.” You can’t judge a person by what you think, you can only judge a person from what you know.”

I learned many things about Glen and what’s important in life, but there is one thing that stands out—something Glen always does and does well. Glen helps people. He did it as a state trooper, and he does it in our school, where he works on construction projects. Glen told me that he believes that our most powerful tools are writing and listening to others. I think those tools are important, too, but I also believe there are other tools to help solve many of our problems and create a better future: to be compassionate, to create caring relationships, and to help others. Just like Glen Tyrell does each and every day.

Isaac Ziemba is in seventh grade at the Odyssey Multiage Program on a small island called Bainbridge near Seattle, Washington. Isaac’s favorite subject in school is history because he has always been interested in how the past affects the future. In his spare time, you can find Isaac hunting for crab with his Dad, looking for artifacts around his house with his metal detector, and having fun with his younger cousin, Conner.

Lily Hersch

The Crest Academy, Salida, Colo.

The Phone Call

Dear Grandpa,

In my short span of life—12 years so far—you’ve taught me a lot of important life lessons that I’ll always have with me. Some of the values I talk about in this writing I’ve learned from you.

Dedicated to my Gramps.

In the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” author and photographer Nancy Hill asked people to name the three things that mattered most to them. After reading the essay prompt for the article, I immediately knew who I wanted to interview: my grandpa Gil.

My grandpa was born on January 25, 1942. He lived in a minuscule tenement in The Bronx with his mother,

father, and brother. His father wasn’t around much, and, when he was, he was reticent and would snap occasionally, revealing his constrained mental pain. My grandpa says this happened because my great grandfather did not have a father figure in his life. His mother was a classy, sharp lady who was the head secretary at a local police district station. My grandpa and his brother Larry did not care for each other. Gramps said he was very close to his mother, and Larry wasn’t. Perhaps Larry was envious for what he didn’t have.

Decades after little to no communication with his brother, my grandpa decided to spontaneously visit him in Florida, where he resided with his wife. Larry was taken aback at the sudden reappearance of his brother and told him to leave. Since then, the two brothers have not been in contact. My grandpa doesn’t even know if Larry is alive.

My grandpa is now a retired lawyer, married to my wonderful grandma, and living in a pretty house with an ugly dog named BoBo.

So, what’s important to you, Gramps?

He paused a second, then replied, “Family, kindness, and empathy.”

“Family, because it’s my family. It’s important to stay connected with your family. My brother, father, and I never connected in the way I wished, and sometimes I contemplated what could’ve happened. But you can’t change the past. So, that’s why family’s important to me.”

Family will always be on my “Top Three Most Important Things” list, too. I can’t imagine not having my older brother, Zeke, or my grandma in my life. I wonder how other kids feel about their families? How do kids trapped and separated from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border feel? What about orphans? Too many questions, too few answers.

“Kindness, because growing up and not seeing a lot of kindness made me realize how important it is to have that in the world. Kindness makes the world go round.”

What is kindness? Helping my brother, Eli, who has Down syndrome, get ready in the morning? Telling people what they need to hear, rather than what they want to hear? Maybe, for now, I’ll put wisdom, not kindness, on my list.

“Empathy, because of all the killings and shootings [in this country.] We also need to care for people—people who are not living in as good circumstances as I have. Donald Trump and other people I’ve met have no empathy. Empathy is very important.”

Empathy is something I’ve felt my whole life. It’ll always be important to me like it is important to my grandpa. My grandpa shows his empathy when he works with disabled children. Once he took a disabled child to a Christina Aguilera concert because that child was too young to go by himself. The moments I feel the most empathy are when Eli gets those looks from people. Seeing Eli wonder why people stare at him like he’s a freak makes me sad, and annoyed that they have the audacity to stare.

After this 2 minute and 36-second phone call, my grandpa has helped me define what’s most important to me at this time in my life: family, wisdom, and empathy. Although these things are important now, I realize they can change and most likely will.

When I’m an old woman, I envision myself scrambling through a stack of storage boxes and finding this paper. Perhaps after reading words from my 12-year-old self, I’ll ask myself “What’s important to me?”

Lily Hersch is a sixth-grader at Crest Academy in Salida, Colorado. Lily is an avid indoorsman, finding joy in competitive spelling, art, and of course, writing. She does not like Swiss cheese.

“Tell It Like It Is” Interview Winner

Jonas Buckner

KIPP: Gaston College Preparatory, Gaston, N.C.

Lessons My Nana Taught Me

I walked into the house. In the other room, I heard my cousin screaming at his game. There were a lot of Pioneer Woman dishes everywhere. The room had the television on max volume. The fan in the other room was on. I didn’t know it yet, but I was about to learn something powerful.

I was in my Nana’s house, and when I walked in, she said, “Hey Monkey Butt.”

I said, “Hey Nana.”

Before the interview, I was talking to her about what I was gonna interview her on. Also, I had asked her why I might have wanted to interview her, and she responded with, “Because you love me, and I love you too.”

Now, it was time to start the interview. The first

question I asked was the main and most important question ever: “What three things matter most to you and you only?”

She thought of it very thoughtfully and responded with, “My grandchildren, my children, and my health.”

Then, I said, “OK, can you please tell me more about your health?”

She responded with, “My health is bad right now. I have heart problems, blood sugar, and that’s about it.” When she said it, she looked at me and smiled because she loved me and was happy I chose her to interview.

I replied with, “K um, why is it important to you?”

She smiled and said, “Why is it…Why is my health important? Well, because I want to live a long time and see my grandchildren grow up.”

I was scared when she said that, but she still smiled. I was so happy, and then I said, “Has your health always been important to you.”

She responded with “Nah.”

Then, I asked, “Do you happen to have a story to help me understand your reasoning?”

She said, “No, not really.”

Now we were getting into the next set of questions. I said, “Remember how you said that your grandchildren matter to you? Can you please tell me why they matter to you?”

Then, she responded with, “So I can spend time with them, play with them, and everything.”

Next, I asked the same question I did before: “Have you always loved your grandchildren?”

She responded with, “Yes, they have always been important to me.”

Then, the next two questions I asked she had no response to at all. She was very happy until I asked, “Why do your children matter most to you?”

She had a frown on and responded, “My daughter Tammy died a long time ago.”

Then, at this point, the other questions were answered the same as the other ones. When I left to go home I was thinking about how her answers were similar to mine. She said health, and I care about my health a lot, and I didn’t say, but I wanted to. She also didn’t have answers for the last two questions on each thing, and I was like that too.

The lesson I learned was that no matter what, always keep pushing because even though my aunt or my Nana’s daughter died, she kept on pushing and loving everyone. I also learned that everything should matter to us. Once again, I chose to interview my Nana because she matters to me, and I know when she was younger she had a lot of things happen to her, so I wanted to know what she would say. The point I’m trying to make is that be grateful for what you have and what you have done in life.

Jonas Buckner is a sixth-grader at KIPP: Gaston College Preparatory in Gaston, North Carolina. Jonas’ favorite activities are drawing, writing, math, piano, and playing AltSpace VR. He found his passion for writing in fourth grade when he wrote a quick autobiography. Jonas hopes to become a horror writer someday.

From The Author: Responses to Student Winners

Dear Emily, Isaac, Antonia, Rory, Praethong, Amanda, Lily, and Jonas,

Your thought-provoking essays sent my head spinning. The more I read, the more impressed I was with the depth of thought, beauty of expression, and originality. It left me wondering just how to capture all of my reactions in a single letter. After multiple false starts, I’ve landed on this: I will stick to the theme of three most important things.

The three things I found most inspirational about your essays:

You listened.

You connected.

We live in troubled times. Tensions mount between countries, cultures, genders, religious beliefs, and generations. If we fail to find a way to understand each other, to see similarities between us, the future will be fraught with increased hostility.

You all took critical steps toward connecting with someone who might not value the same things you do by asking a person who is generations older than you what matters to them. Then, you listened to their answers. You saw connections between what is important to them and what is important to you. Many of you noted similarities, others wondered if your own list of the three most important things would change as you go through life. You all saw the validity of the responses you received and looked for reasons why your interviewees have come to value what they have.

It is through these things—asking, listening, and connecting—that we can begin to bridge the differences in experiences and beliefs that are currently dividing us.

Individual observations

Each one of you made observations that all of us, regardless of age or experience, would do well to keep in mind. I chose one quote from each person and trust those reading your essays will discover more valuable insights.

“Our priorities may seem different, but they come back to basic human needs. We all desire a purpose, strive to be happy, and work to make a positive impact.”

“You can’t judge a person by what you think , you can only judge a person by what you know .”

Emily (referencing your interviewee, who is battling cancer):

“Master Chief Petty Officer James has shown me how to appreciate what I have around me.”

Lily (quoting your grandfather):

“Kindness makes the world go round.”

“Everything should matter to us.”

Praethong (quoting your interviewee, Sandra, on the importance of family):

“It’s important to always maintain that connection you have with each other, your family, not just next-door neighbors you talk to once a month.”

“I wonder if maybe we relearn what is most important when we grow older. That the pressure to be successful subsides and that valuing family, health, and happiness is what ends up saving the world.”

“Listen to what others have to say. Listen to the people who have already experienced hardship. You will learn from them and you can even make their day by giving them a chance to voice their thoughts.”

I end this letter to you with the hope that you never stop asking others what is most important to them and that you to continue to take time to reflect on what matters most to you…and why. May you never stop asking, listening, and connecting with others, especially those who may seem to be unlike you. Keep writing, and keep sharing your thoughts and observations with others, for your ideas are awe-inspiring.

I also want to thank the more than 1,000 students who submitted essays. Together, by sharing what’s important to us with others, especially those who may believe or act differently, we can fill the world with joy, peace, beauty, and love.

We received many outstanding essays for the Winter 2019 Student Writing Competition. Though not every participant can win the contest, we’d like to share some excerpts that caught our eye:

Whether it is a painting on a milky canvas with watercolors or pasting photos onto a scrapbook with her granddaughters, it is always a piece of artwork to her. She values the things in life that keep her in the moment, while still exploring things she may not have initially thought would bring her joy.

—Ondine Grant-Krasno, Immaculate Heart Middle School, Los Angeles, Calif.

“Ganas”… It means “desire” in Spanish. My ganas is fueled by my family’s belief in me. I cannot and will not fail them.

—Adan Rios, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

I hope when I grow up I can have the love for my kids like my grandma has for her kids. She makes being a mother even more of a beautiful thing than it already is.

—Ashley Shaw, Columbus City Prep School for Girls, Grove City, Ohio

You become a collage of little pieces of your friends and family. They also encourage you to be the best you can be. They lift you up onto the seat of your bike, they give you the first push, and they don’t hesitate to remind you that everything will be alright when you fall off and scrape your knee.

— Cecilia Stanton, Bellafonte Area Middle School, Bellafonte, Pa.

Without good friends, I wouldn’t know what I would do to endure the brutal machine of public education.

—Kenneth Jenkins, Garrison Middle School, Walla Walla, Wash.

My dog, as ridiculous as it may seem, is a beautiful example of what we all should aspire to be. We should live in the moment, not stress, and make it our goal to lift someone’s spirits, even just a little.

—Kate Garland, Immaculate Heart Middle School, Los Angeles, Calif.

I strongly hope that every child can spare more time to accompany their elderly parents when they are struggling, and moving forward, and give them more care and patience. so as to truly achieve the goal of “you accompany me to grow up, and I will accompany you to grow old.”

—Taiyi Li, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

I have three cats, and they are my brothers and sisters. We share a special bond that I think would not be possible if they were human. Since they do not speak English, we have to find other ways to connect, and I think that those other ways can be more powerful than language.

—Maya Dombroskie, Delta Program Middle School, Boulsburg, Pa.

We are made to love and be loved. To have joy and be relational. As a member of the loneliest generation in possibly all of history, I feel keenly aware of the need for relationships and authentic connection. That is why I decided to talk to my grandmother.

—Luke Steinkamp, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

After interviewing my grandma and writing my paper, I realized that as we grow older, the things that are important to us don’t change, what changes is why those things are important to us.

—Emily Giffer, Our Lady Star of the Sea, Grosse Pointe Woods, Mich.

The media works to marginalize elders, often isolating them and their stories, and the wealth of knowledge that comes with their additional years of lived experiences. It also undermines the depth of children’s curiosity and capacity to learn and understand. When the worlds of elders and children collide, a classroom opens.

—Cristina Reitano, City College of San Francisco, San Francisco, Calif.

My values, although similar to my dad, only looked the same in the sense that a shadow is similar to the object it was cast on.

—Timofey Lisenskiy, Santa Monica High School, Santa Monica, Calif.

I can release my anger through writing without having to take it out on someone. I can escape and be a different person; it feels good not to be myself for a while. I can make up my own characters, so I can be someone different every day, and I think that’s pretty cool.

—Jasua Carillo, Wellness, Business, and Sports School, Woodburn, Ore.

Notice how all the important things in his life are people: the people who he loves and who love him back. This is because “people are more important than things like money or possessions, and families are treasures,” says grandpa Pat. And I couldn’t agree more.

—Brody Hartley, Garrison Middle School, Walla Walla, Wash.

Curiosity for other people’s stories could be what is needed to save the world.

—Noah Smith, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

Peace to me is a calm lake without a ripple in sight. It’s a starry night with a gentle breeze that pillows upon your face. It’s the absence of arguments, fighting, or war. It’s when egos stop working against each other and finally begin working with each other. Peace is free from fear, anxiety, and depression. To me, peace is an important ingredient in the recipe of life.

—JP Bogan, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

From A Teacher

Charles Sanderson

Wellness, Business and Sports School, Woodburn, Ore.

The Birthday Gift

I’ve known Jodelle for years, watching her grow from a quiet and timid twelve-year-old to a young woman who just returned from India, where she played Kabaddi, a kind of rugby meets Red Rover.

One of my core beliefs as an educator is to show up for the things that matter to kids, so I go to their games, watch their plays, and eat the strawberry jam they make for the county fair. On this occasion, I met Jodelle at a robotics competition to watch her little sister Abby compete. Think Nerd Paradise: more hats made from traffic cones than Golden State Warrior ball caps, more unicorn capes than Nike swooshes, more fanny packs with Legos than clutches with eyeliner.

We started chatting as the crowd chanted and waved six-foot flags for teams like Mystic Biscuits, Shrek, and everyone’s nemesis The Mean Machine. Apparently, when it’s time for lunch at a robotics competition, they don’t mess around. The once-packed gym was left to Jodelle and me, and we kept talking and talking. I eventually asked her about the three things that matter to her most.

She told me about her mom, her sister, and her addiction—to horses. I’ve read enough of her writing to know that horses were her drug of choice and her mom and sister were her support network.

I learned about her desire to become a teacher and how hours at the barn with her horse, Heart, recharge her when she’s exhausted. At one point, our rambling conversation turned to a topic I’ve known far too well—her father.

Later that evening, I received an email from Jodelle, and she had a lot to say. One line really struck me: “In so many movies, I have seen a dad wanting to protect his daughter from the world, but I’ve only understood the scene cognitively. Yesterday, I felt it.”

Long ago, I decided that I would never be a dad. I had seen movies with fathers and daughters, and for me, those movies might as well have been Star Wars, ET, or Alien—worlds filled with creatures I’d never know. However, over the years, I’ve attended Jodelle’s parent-teacher conferences, gone to her graduation, and driven hours to watch her ride Heart at horse shows. Simply, I showed up. I listened. I supported.

Jodelle shared a series of dad poems, as well. I had read the first two poems in their original form when Jodelle was my student. The revised versions revealed new graphic details of her past. The third poem, however, was something entirely different.

She called the poems my early birthday present. When I read the lines “You are my father figure/Who I look up to/Without being looked down on,” I froze for an instant and had to reread the lines. After fifty years of consciously deciding not to be a dad, I was seen as one—and it felt incredible. Jodelle’s poem and recognition were two of the best presents I’ve ever received.

I know that I was the language arts teacher that Jodelle needed at the time, but her poem revealed things I never knew I taught her: “My father figure/ Who taught me/ That listening is for observing the world/ That listening is for learning/Not obeying/Writing is for connecting/Healing with others.”

Teaching is often a thankless job, one that frequently brings more stress and anxiety than joy and hope. Stress erodes my patience. Anxiety curtails my ability to enter each interaction with every student with the grace they deserve. However, my time with Jodelle reminds me of the importance of leaning in and listening.

In the article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age” by Nancy Hill, she illuminates how we “live among such remarkable people, yet few know their stories.” For the last twenty years, I’ve had the privilege to work with countless of these “remarkable people,” and I’ve done my best to listen, and, in so doing, I hope my students will realize what I’ve known for a long time; their voices matter and deserve to be heard, but the voices of their tias and abuelitos and babushkas are equally important. When we take the time to listen, I believe we do more than affirm the humanity of others; we affirm our own as well.

Charles Sanderson has grounded his nineteen-year teaching career in a philosophy he describes as “Mirror, Window, Bridge.” Charles seeks to ensure all students see themselves, see others, and begin to learn the skills to build bridges of empathy, affinity, and understanding between communities and cultures that may seem vastly different. He proudly teaches at the Wellness, Business and Sports School in Woodburn, Oregon, a school and community that brings him joy and hope on a daily basis.

From The Author: Response to Charles Sanderson

Dear Charles Sanderson,

Thank you for submitting an essay of your own in addition to encouraging your students to participate in YES! Magazine’s essay contest.

Your essay focused not on what is important to you, but rather on what is important to one of your students. You took what mattered to her to heart, acting upon it by going beyond the school day and creating a connection that has helped fill a huge gap in her life. Your efforts will affect her far beyond her years in school. It is clear that your involvement with this student is far from the only time you have gone beyond the classroom, and while you are not seeking personal acknowledgment, I cannot help but applaud you.

In an ideal world, every teacher, every adult, would show the same interest in our children and adolescents that you do. By taking the time to listen to what is important to our youth, we can help them grow into compassionate, caring adults, capable of making our world a better place.

Your concerted efforts to guide our youth to success not only as students but also as human beings is commendable. May others be inspired by your insights, concerns, and actions. You define excellence in teaching.

Get Stories of Solutions to Share with Your Classroom

Teachers save 50% on YES! Magazine.

Inspiration in Your Inbox

Get the free daily newsletter from YES! Magazine: Stories of people creating a better world to inspire you and your students.

Home — Essay Samples — Psychology — Personality Psychology — Motivation

Essays on Motivation

🌟 the importance of writing a motivation essay 📝.

Motivation is like that extra sprinkle of magic dust that gives us the boost we need to achieve our goals and dreams ✨✨. It's the driving force behind our actions and the fuel that keeps us going when things get tough. Writing an essay about motivation allows us to delve deeper into this fascinating topic and explore its various aspects. So, why not grab your pen (or keyboard) and let's dive into the world of motivation! 💪📚

🔍 Choosing the Perfect Motivation Essay Topic 🤔

When it comes to choosing a topic for your motivation essay, there are a few things to consider. First, think about what aspect of motivation you find most intriguing. Is it personal motivation, motivation in the workplace, or maybe the psychology behind motivation? Once you have a general idea, narrow it down further to a specific angle that interests you the most.

💡 Motivation Argumentative Essay 💪📝

An argumentative essay on motivation requires you to take a stance and provide evidence to support your viewpoint. Here are ten exciting topics to get those creative juices flowing:

- The role of intrinsic motivation in academic success

- The impact of extrinsic rewards on employee motivation

- Does social media affect motivation levels in teenagers?

- The connection between motivation and self-esteem

- How does motivation differ between genders?

- The influence of music on motivation levels

- Does money truly motivate people in the workplace?

- The effects of positive reinforcement on motivation

- The link between motivation and mental health

- How does goal-setting impact motivation?

🌪️ Motivation Cause and Effect Essay 📝

In a cause and effect essay, you explore the reasons behind certain motivations and their outcomes. Here are ten thought-provoking topics to consider:

- The causes and effects of procrastination on motivation

- How does a lack of motivation impact academic performance?

- The relationship between motivation and success in sports

- The effects of parental motivation on children's achievements

- How does motivation affect mental well-being?

- The causes and effects of burnout on motivation levels

- The impact of motivation on work-life balance

- How does motivation affect creativity and innovation?

- The causes and effects of peer pressure on motivation

- The relationship between motivation and goal attainment

💬 Motivation Opinion Essay 💭📝

In an opinion essay, you express your personal thoughts and beliefs about motivation. Here are ten intriguing topics to spark your imagination:

- Is self-motivation more effective than external motivation?

- Are rewards a necessary form of motivation?

- Should schools focus more on intrinsic motivation?

- The role of motivation in achieving work-life balance

- Is motivation a learned behavior or innate?

- The impact of motivation on personal growth and development

- Does motivation play a significant role in overcoming obstacles?

- Is fear an effective motivator?

- The role of motivation in maintaining a healthy lifestyle

- Can motivation be sustained in the long term?

📚 Motivation Informative Essay 🧠📝

An informative essay on motivation aims to educate and provide valuable insights. Here are ten fascinating topics to explore:

- The psychology behind motivation and its theories

- How to stay motivated in challenging times

- The impact of motivation on personal and professional success

- Motivation techniques for achieving fitness goals

- The role of motivation in leadership and management

- Motivation in the context of mental health and well-being

- The history of motivation research and key figures

- Motivation strategies for students and educators

- Motivation and its connection to creativity and innovation

- Motivation in different cultural and societal contexts

📜 Thesis Statement Examples 📜

Here are a few thesis statement examples to inspire your motivation essay:

- 1. "Motivation, whether intrinsic or extrinsic, plays a pivotal role in driving individuals towards achieving their goals and aspirations."

- 2. "This essay explores the multifaceted nature of motivation, examining its psychological underpinnings, societal influences, and practical applications."

- 3. "In a world filled with challenges and opportunities, understanding the mechanisms of motivation empowers individuals to overcome obstacles and reach new heights of success."

📝 Introduction Paragraph Examples 📝

Here are some introduction paragraph examples for your motivation essay:

- 1. "Motivation is the driving force behind human actions, the invisible hand that propels us toward our goals. It is the spark that ignites the fire of determination within us, pushing us to overcome obstacles and realize our dreams."

- 2. "In a world where challenges often outnumber opportunities, motivation serves as the compass guiding us through life's intricate maze. It is the unwavering belief in our abilities and the fuel that keeps our ambitions burning bright."

- 3. "Picture a world without motivation—a world where dreams remain unfulfilled, talents remain hidden, and aspirations remain dormant. Fortunately, we do not live in such a world, and this essay delves into the profound impact of motivation on human lives."

🔚 Conclusion Paragraph Examples 📝

Here are some conclusion paragraph examples for your motivation essay:

- 1. "As we conclude this journey through the realm of motivation, let us remember that it is the driving force behind our accomplishments, the cornerstone of our achievements. With unwavering motivation, we can surmount any obstacle and turn our aspirations into reality."

- 2. "In the grand tapestry of human existence, motivation weaves the threads of determination, perseverance, and success. This essay's culmination serves as a testament to the enduring power of motivation and its ability to shape our destinies."

- 3. "As we bid farewell to this exploration of motivation, let us carry forward the knowledge that motivation is not just a concept but a potent force that propels us toward greatness. With motivation as our guide, we can continue to chase our dreams and conquer new horizons."

The Puzzle of Motivation Analysis

Team captain speech, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Brutus Character Analysis

Finding of what motivates you: nick vujicic, motivation letter (bachelor of business administration), the main types of motivation, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Motivation and Its Various Types

Pushing beyond limits: finding motivation to succeed, my motivation to study medical/health administration, life as a student-athlete, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Learning Styles and Motivation Reflection

My motivation to undergo a masters program in business, entrepreneurship, and technology, my letter of motivation: electrical and electronics engineering, assessment of my motivation and values, overview of the motivational theories for business, autonomy, mastery, and purpose: motivation, applying work motivation theories to business situations, drive-reduction theory and motivation, the impact of motivation and affect on judgement, my motivation to study biomedical engineering in the netherlands, research of the theories of motivation: expectancy theory and the equity theory, understanding of my personal motivation, the motivation letter for you, herzberg two-factor theory of motivation, motivation in different aspects of our lives, the importance of motivation in human resource management, my motivation to get a bachelor degree in nursing, my potential and motivation to excel in the field of medicine, my motivational letter: mechanical engineering, motivation letter for computer science scholarship.

Motivation is what explains why people or animals initiate, continue or terminate a certain behavior at a particular time. Motivational states are commonly understood as forces acting within the agent that create a disposition to engage in goal-directed behavior.

There are four main tyoes of motivation: Intrinsic, extrinsic, unconscious, and conscious.

Theories articulating the content of motivation: Maslow's hierarchy of needs, Herzberg's two-factor theory, Alderfer's ERG theory, Self-Determination Theory, Drive theory.

Relevant topics

- Growth Mindset

- Procrastination

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

How to Motivate Students: 12 Classroom Tips & Examples

Inspire. Instill drive. Incite excitement. Stimulate curiosity.

These are all common goals for many educators. However, what can you do if your students lack motivation? How do you light that fire and keep it from burning out?

This article will explain and provide examples of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the classroom. Further, we will provide actionable methods to use right now in your classroom to motivate the difficult to motivate. Let’s get started!

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your students create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

The science of motivation explained, how to motivate students in the classroom, 9 ways teachers can motivate students, encouraging students to ask questions: 3 tips, motivating students in online classes, helpful resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Goal-directed activities are started and sustained by motivation. “Motivational processes are personal/internal influences that lead to outcomes such as choice, effort, persistence, achievement, and environmental regulation” (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020). There are two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic motivation is internal to a person.

For example, you may be motivated to achieve satisfactory grades in a foreign language course because you genuinely want to become fluent in the language. Students like this are motivated by their interest, enjoyment, or satisfaction from learning the material.

Not surprisingly, intrinsic motivation is congruous with higher performance and predicts student performance and higher achievement (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Extrinsic motivation is derived from a more external source and involves a contingent reward (Benabou & Tirole, 2003).

For example, a student may be motivated to achieve satisfactory grades in a foreign language course because they receive a tangible reward or compliments for good grades. Their motivation is fueled by earning external rewards or avoiding punishments. Rewards may even include approval from others, such as parents or teachers.

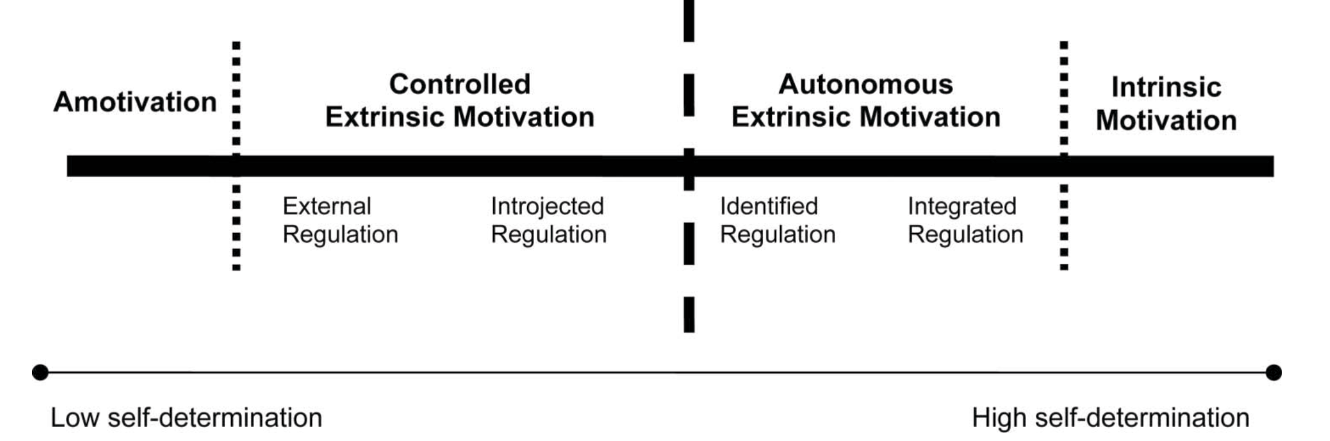

Self-determination theory addresses the why of behavior and asserts that there are various motivation types that lie on a continuum, including external motivation, internal motivation, and amotivation (Sheehan et al., 2018).

- Relatedness

Student autonomy is the ownership they take of their learning or initiative.

Generate students’ autonomy by involving them in decision-making. Try blended learning, which combines whole class lessons with independent learning. Teach accountability by holding students accountable and modeling and thinking aloud your own accountability.

In addressing competence, students must feel that they can succeed and grow. Assisting students in developing their self-esteem is critical. Help students see their strengths and refer to their strengths often. Promote a kid’s growth mindset .

Relatedness refers to the students’ sense of belonging and connection. Build this by establishing relationships. Facilitate peer connections by using team-building exercises and encouraging collaborative learning. Develop your own relationship with each student. Explore student interests to develop common ground.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Motivating students while teaching a subject and providing classroom management is definitely a juggling act. Try introducing a few of the suggestions below and see what happens.

Relationships

First and foremost, it is critical to develop relationships with your students. When students begin formal schooling, they need to develop quality relationships, as interpersonal relationships in the school setting influence children’s development and positively impact student outcomes, which includes their motivation to learn, behavior, and cognitive skills (McFarland et al., 2016).

Try administering interest inventories at the beginning of the school year. Make a point to get to know each student and demonstrate your interest by asking them about their weekend, sports game, or other activities they may participate in.

Physical learning environment

Modify the physical learning environment. Who says students need to sit in single-file rows all facing the front of the room or even as desks for that matter?

Flexible seating is something you may want to try. Students who are comfortable in a learning space are better engaged, which leads to more meaningful, impactful learning experiences (Cole et al., 2021). You may try to implement pillows, couches, stools, rocking chairs, rolling chairs, bouncing chairs, or even no chairs at all.

Include parents

Involve parents and solicit their aid to help encourage students. Parents are a key factor in students’ motivation (Tóth-Király et al., 2022).

It is important to develop your relationship with these crucial allies. Try making positive phone calls home prior to the negative phone calls to help build an effective relationship. Involve parents by sending home a weekly newsletter or by inviting them into your classroom for special events. Inform them that you are a team and have the same goals for their child.

The relevance of the material is critical for instilling motivation. Demonstrating why the material is useful or tying the material directly to students’ lives is necessary for obtaining student interest.

It would come as no surprise that if a foreign language learner is not using relevant material, it will take longer for that student to acquire the language and achieve their goals (Shatz, 2014). If students do not understand the importance or real-world application for what they are learning, they may not be motivated to learn.

Student-centered learning

Student-centered learning approaches have been proven to be more effective than teacher-centered teaching approaches (Peled et al., 2022).

A student-centered approach engages students in the learning process, whereas a teacher-centered approach involves the teacher delivering the majority of the information. This type of teaching requires students to construct meaning from new information and prior experience.

Give students autonomy and ownership of what they learn. Try enlisting students as the directors of their own learning and assign project-based learning activities.

Find additional ways to integrate technology. Talk less and encourage the students to talk more. Involving students in decision-making and providing them opportunities to lead are conducive to a student-centered learning environment.

Collaborative learning

Collaborative learning is definitely a strategy to implement in the classroom. There are both cognitive and motivational benefits to collaborative learning (Järvelä et al., 2010), and social learning theory is a critical lens with which to examine motivation in the classroom.

You may try assigning group or partner work where students work together on a common task. This is also known as cooperative learning. You may want to offer opportunities for both partner and small group work. Allowing students to choose their partners or groups and assigning partners or groups should also be considered.

Alternative answering

Have you ever had a difficult time getting students to answer your questions? Who says students need to answer verbally? Try using alternative answering methods, such as individual whiteboards, personal response systems such as “clickers,” or student response games such as Kahoot!

Quizlet is also an effective method for obtaining students’ answers (Setiawan & Wiedarti, 2020). Using these tools allows every student to participate, even the timid students, and allows the teacher to perform a class-wide formative assessment on all students.

New teaching methods

Vary your teaching methods. If you have become bored with the lessons you are delivering, it’s likely that students have also become bored.

Try new teaching activities, such as inviting a guest speaker to your classroom or by implementing debates and role-play into your lessons. Teacher and student enjoyment in the classroom are positively linked, and teachers’ displayed enthusiasm affects teacher and student enjoyment (Frenzel et al., 2009).

Perhaps check out our article on teacher burnout to reignite your spark in the classroom. If you are not enjoying yourself, your students aren’t likely to either.

Aside from encouraging students to answer teacher questions, prompting students to ask their own questions can also be a challenge.

When students ask questions, they demonstrate they are thinking about their learning and are engaged. Further, they are actively filling the gaps in their knowledge. Doğan and Yücel-Toy (2020, p. 2237) posit:

“The process of asking questions helps students understand the new topic, realize others’ ideas, evaluate their own progress, monitor learning processes, and increase their motivation and interest on the topic by arousing curiosity.”

Student-created questions are critical to an effective learning environment. Below are a few tips to help motivate students to ask questions.

Instill confidence and a safe environment

Students need to feel safe in their classrooms. A teacher can foster this environment by setting clear expectations of respect between students. Involve students in creating a classroom contract or norms.

Refer to your classroom’s posted contract or norms periodically to review student expectations. Address any deviation from these agreements and praise students often. Acknowledge all students’ responses, no matter how wild or off-topic they may be.

Graphic organizers

Provide students with graphic organizers such as a KWL chart. The KWL chart helps students organize what they already Know , what they Want to learn, and what they Learned .

Tools such as these will allow students to process their thinking and grant them time to generate constructive questions. Referring to this chart will allow more timid students to share their questions.

Although intrinsic motivation is preferred (Ryan & Deci, 2020), incentives should also be used when appropriate. Token systems, where students can exchange points for items, are an effective method for improving learning and positively affecting student behavior (Homer et al., 2018).

Tangible and intangible incentives may be used to motivate students if they have not developed intrinsic motivation. Intangible items may include lunch with the teacher, a coupon to only complete half of an assignment, or a show-and-tell session. Of course, a good old-fashioned treasure box may help as well.

If students are unwilling to ask questions in front of the class, try implementing a large poster paper where students are encouraged to use sticky notes to write down their questions. Teachers may refer to the questions and answer them at a separate time. This practice is called a “parking lot.” Also, consider allowing students to share questions in small groups or with partners.

Student motivation: how to motivate students to learn

Just as in the face-to-face setting, relationships are crucial for online student motivation as well. Build relationships by getting to know your students’ interests. Determining student interests will also be key in the virtual environment.

Try incorporating a show-and-tell opportunity where students can display and talk about objects from around their home that are important to them. Peer-to-peer relationships should also be encouraged, and accomplishing this feat in an online class can be difficult. Here is a resource you can use to help plan team-building activities to bring your students together.

Game-based response systems such as Kahoot! may increase motivation. These tools use gamification to encourage motivation and engagement.

Incentives may also be used in the computer-based setting. Many schools have opted to use Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports Rewards . This curriculum nurtures a positive school culture and aims to improve student behavior. Points are earned by students meeting expectations and can be exchanged for items in an online store.

To further develop strong relationships with students and parents, remark on the relevancy of the materials and instill a student-centered learning approach that addresses autonomy. You may also wish to include alternative means of answering questions, vary your teaching methods, and implement collaborative learning.

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We have many useful articles and worksheets you can use with your students. To get an excellent start on the foundations of motivation, we recommend our article What Is Motivation? A Psychologist Explains .

If you’re curious about intrinsic motivation, you may be interested in What Is Intrinsic Motivation? 10 Examples and Factors Explained . And if you wish to learn more about extrinsic motivation, What Is Extrinsic Motivation? 9 Everyday Examples and Activities may be of interest to you.

Perhaps using kids’ reward coupons such as these may help increase motivation. Teachers could modify the coupons to fit their classroom or share these exact coupons with parents at parent–teacher conferences to reinforce children’s efforts at school .

For some students, coloring is an enjoyable and creative outlet. Try using a coloring sheet such as this Decorating Cookies worksheet for when students complete their work or as a reward for good behavior.

These 17 Motivation and Goal Achievement Exercises were designed for professionals to help others turn their dreams into reality by applying the latest science-based behavioral change techniques. You can consider these exercises to better understand your own motivation or tweak some activities for younger learners.

“The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles, but to irrigate deserts.”

C. S. Lewis

While we know how challenging it is to motivate students while teaching our specific subjects and attending to classroom management, we also understand the importance of motivation.