- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 What We Do and Do Not Know: A Review of the Knowledge Transfer Literature

- Published: April 2023

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Attempts to transfer knowledge across organizational borders vary greatly in terms of processes and outcomes. There are both successes and failures. This chapter reviews a broad selection of literature to shed light on what we know from research about the expressions of and causes of such variations. The chapter identifies and reviews literature from seven research traditions that study the influence on knowledge processes and outcomes from (1) formal organizational structure, (2) absorptive capacity, (3) social networks, (4) geographical distance, (5) cultural distance, (6) institutional distance, and (7) characteristics of the transferred knowledge. The review sums up consistent findings as well as mixed and inconsistent findings. It also identifies white spots in our understanding of why border crossing knowledge transfers vary in processes and outcomes.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, a systematic review of the antecedents of knowledge transfer: an actant-object view.

European Business Review

ISSN : 0955-534X

Article publication date: 14 October 2019

While numerous studies have studied knowledge transfer (KT) and endeavored to address factors influencing KT, little effort has been made to integrate the findings of prior studies. This paper aims to classify the literature on KT through a detailed exploration of different perspectives of KT inter and intra organizations.

Design/methodology/approach

Using actor–network theory (ANT) as the baseline, we conducted a systematic review of KT research to summarize prior KT studies and classify the influential factors on KT. The review covered 115 empirical articles published between 1987 and 2017.

Drawing on the review and ANT guidelines, the authors proposed a conceptual model to categorize KT constitutes into objects including those related to (1) knowledge, (2) knowledge exchange and (3) technology, as well as actants including those related to (4) organization, (5) team/business unit and (6) knowledge sender/receiver.

Research limitations/implications

Adopting a holistic synthesized approach based on ANT, this research puts forward a valid theoretical foundation on further understanding of KT and its antecedents. Indeed, this paper investigates KT inter and intra organizations to recognize and locate the key antecedents of KT, which is of substantial applicability in today’s knowledge-driven economy.

Practical implications

The findings advance managers and practitioners’ understanding of the important role of actants and objects and their interplay in KT practices.

Originality/value

While most studies on KT have a narrow focus, this research contributes to holistic understanding of motivational, behavioral, technological and organizational issues related to KT. It also offers a thorough and context-free literature review on KT, which synthesizes the findings of prior studies on KT.

- Knowledge transfer

- Actor network theory (ANT)

- Antecedents

- Knowledge exchange

- Systematic review

Shahbaznezhad, H. , Rashidirad, M. and Vaghefi, I. (2019), "A systematic review of the antecedents of knowledge transfer: an actant-object view", European Business Review , Vol. 31 No. 6, pp. 970-995. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-07-2018-0133

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

Language: English | Chinese

Key components of knowledge transfer and exchange in health services research: Findings from a systematic scoping review

卫生服务研究中知识传递和交流的关键组分:系统性范围综述得来的调查结果, lucia prihodova.

1 UCD School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin Ireland

2 Palliative Care Research Network, All Ireland Institute for Hospice and Palliative Care, Dublin Ireland

Suzanne Guerin

3 UCD Centre for Disability Studies, University College Dublin, Dublin Ireland

Conall Tunney

W. george kernohan.

4 Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Belfast Northern Ireland

Associated Data

To identify the key common components of knowledge transfer and exchange in existing models to facilitate practice developments in health services research.

There are over 60 models of knowledge transfer and exchange designed for various areas of health care. Many of them remain untested and lack guidelines for scaling‐up of successful implementation of research findings and of proven models ensuring that patients have access to optimal health care, guided by current research.

A scoping review was conducted in line with PRISMA guidelines. Key components of knowledge transfer and exchange were identified using thematic analysis and frequency counts.

Data Sources

Six electronic databases were searched for papers published before January 2015 containing four key terms/variants: knowledge, transfer, framework, health care.

Review Methods

Double screening, extraction and coding of the data using thematic analysis were employed to ensure rigour. As further validation stakeholders’ consultation of the findings was performed to ensure accessibility.

Of the 4,288 abstracts, 294 full‐text articles were screened, with 79 articles analysed. Six key components emerged: knowledge transfer and exchange message, Stakeholders and Process components often appeared together, while from two contextual components Inner Context and the wider Social, Cultural and Economic Context, with the wider context less frequently considered. Finally, there was little consideration of the Evaluation of knowledge transfer and exchange activities. In addition, specific operational elements of each component were identified.

Conclusions

The six components offer the basis for knowledge transfer and exchange activities, enabling researchers to more effectively share their work. Further research exploring the potential contribution of the interactions of the components is recommended.

目的

的在于确定已有模式中知识传递和交流的关键通用组分,以促进卫生服务研究的实践发展。

背景为各种医疗保健领域设计了60多种知识转移和交流模式。当中许多吧没有进行测试,也没有指导方针来既扩大研究结果的成功实施,又没有指导方针来扩大已证模型的成功实施,以便于确保患者在当前研究的指导下获得最佳的医疗保健。

设计

根据PRISMA指南进行了范围综述。采用了主题分析和频率计数来确定知识传递和交流的关键组分。

数据来源

在6个电子数据库中搜索了2015年1月之前发表的论文,其中包含四个关键术语/变体:知识、传递、框架、医疗保健。

综述方法

采用了主题分析对数据进行双重筛选,提取和编码,以便确保严谨性。随着进一步确认,利益相关者对调查结果进行了协商,以确保可访问性。

结果

在4288篇摘要中,筛选了294篇全文文章,分析了79篇文章。出现了6个关键组分:知识传递和交流信息、利益相关者和流程组件经常一起出现、而出现于两个上下文组件——内部语境和更广阔的社会,文化和经济语境、不太经常考虑更广阔的语境。最后,很少考虑对知识传递和交流活动的评估。此外,还确定了每个组分的具体操作要素。

结论

这六个组分为知识传递和交流活动提供了基础,使研究人员能够更有效地共享其工作。建议进一步研究探讨组件交互的潜在贡献。

Why is this research or review needed?

- There is lack of studies that inform the application of knowledge transfer and exchange strategies across various healthcare settings to enable evidence‐based practice.

- Analysis and synthesis of existing knowledge transfer and exchange frameworks would identify their commonalities and core concepts.

What are the key findings?

- Six key components emerged from analysis of 79 articles; the knowledge transfer and exchange Message, Stakeholders and Process, Inner Context, Social, Cultural and Economic Context and Evaluation. Their prevalence varied, especially in relation to the Evaluation of KTE activities.

- In addition, specific operational elements of each key component were identified.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

- The components and the specific operational elements offer guidance for knowledge transfer and exchange activities in applied setting and can serve as a framework within which to evaluate their impact.

1. INTRODUCTION

While the ultimate aim of health research is to inform practice and policy, research findings can only change population health outcomes if adopted and embedded by healthcare systems, organizations and clinicians (Grimshaw, Ward, & Eccles, 2006 ). Therefore, it is important to explore the most effective ways of implementing existing evidence into practice (Kutner 2011 ). Applying research findings to practice is especially difficult due to the broad, holistic and elements of complex interventions offered in various practice settings (Evans, Snooks, Howson, & Davies, 2013 ). Several frameworks or models have been developed to provide guidance for the process of implementing research evidence into practice, including the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework (PARiHS; Rycroft‐Malone, 2004 ) and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR, Damschroder et al., 2009 ). This review was performed with the focus on a specific aspect of implementation—the concept of knowledge transfer and exchange (KTE), which is often noted but not explicated in existing models in the area of implementation. Discussing the impact of implementation research in mental health services (Proctor et al., 2009 ) considers KTE in this wider context, noting the movement of research into practice settings as the basis for implementation. They also cite work by the NIH and the CDC, which defines implementation as requiring the generation of knowledge, the dissemination (transfer, our addition) of this knowledge, followed by active efforts to support the implementation of this knowledge.

1.1. Background

There are many terms used to refer to KTE related activity, including dissemination, knowledge transfer and knowledge mobilization. A review by (Pentland et al., 2011 ) highlighted the variation in this area, stressing the challenge that this can create in providing guidance to researchers and practitioners. However, to frame the current research, it is important to be explicit about the definition of KTE that underpins this work. For this study, we adopted the following definition of KTE, as one which is routinely cited in research and reflects the views of the authors:

“an interactive interchange of knowledge between research users and researcher producers (Kiefer et al., 2005 ). [Its purpose is] to increase the likelihood that research evidence will be used in policy and practice decisions and to enable researchers to identify practice and policy‐relevant research questions” (cited in Mitton, Adair, McKenzie, Patten, & Perry, 2007 .729).

KTE is a complex, dynamic and iterative social process, (Kiefer et al., 2005 ; Ward, House, & Hamer, 2009a , 2009b ; Ward, Smith, Foy, House, & Hamer, 2010 ) which does not necessarily contribute directly to implementation but instead to an increased chance that evidence can and will be implemented. Consequently, KTE presents an early challenge to implementation of evidence‐based health care. To be rigorous and effective, it has been recommended that KTE activities are guided by a model that clearly shows how the process works and how it can help knowledge producers and users plan and evaluate KTE activities (Anderson, Allen, Peckham, & Goodwin, 2008 ; Armstrong, Waters, Roberts, Oliver, & Popay, 2006 ; Estabrooks, Squires, Cummings, Birdsell, & Norton, 2009 ; Graham, Tetroe, & Grp, 2007 ; McKibbon et al., 2013 ; Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2009 ; Ward, House, & Hamer, 2009a ; Ward, Smith, House, & Hamer, 2012 ; Wilson, Petticrew, Calnan, & Nazareth, 2010 ). Yet, KTE as a key aspect of implementation has rarely been explicitly operationalized in existing models of implementation.

2. THE REVIEW

The aim of this study was to review, analyse and synthesize the key components of KTE as evidenced in published health services research. Apart from the prevalence of the individual components of the components we will also capture the operational elements of these components and their interactions. To contextualize the components and their interactions, the findings will be presented in a form of a model.

2.2. Design

A scoping approach was adopted, following a detailed protocol (Prihodova, Guerin, & Kernohan, 2015 ). The review was guided the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005 ), with additional amendments based on (Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien, 2010 ; Levac et al., 2010 ). While the protocol for this review set out as one of the aims as appraisal of the relevance and suitability of these components for providers, settings and dimensions of palliative care, this study will report the general components of KTE in any healthcare setting identified by the review and their appraisal for palliative care will be addressed in a subsequent publication. In addition, in the absence of reporting guidelines for scoping reviews, the six‐stage process (Table 1 ) was benchmarked against the PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Grp, 2009 ) to ensure rigour.

Stages of systematic review applied

2.3. Search strategy

The search strategy included four search terms and their variations (knowledge (evidence, research, information, data), transfer (exchange, generation, translation, uptake, mobilization, dissemination, implementation), framework (model, concept) and health care (health system, health service, healthcare provider)) and was designed to be as extensive as possible. The search was performed across six main electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE (Elsevier), CINAHL Plus (EBSCO), PsycINFO (ProQuest), Social Services Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)). Only studies that sufficiently described an original (or adapted) explicit framework, model or concept of KTE applied in healthcare setting were included.

To be included, articles had to provide a description of an original (or adapted) model or framework (noting that these terms are often used interchangeably) that considered the implementation of research knowledge and its application. This included articles which presented a specific model of KTE and articles that used KTE models or model elements to inform the implementation of research into practice. Limiting searches to health services settings was intended to ensure a practical focus of the work and the potential to synthesize the operational elements of the KTE process rather than just the theoretical.

2.4. Search outcomes

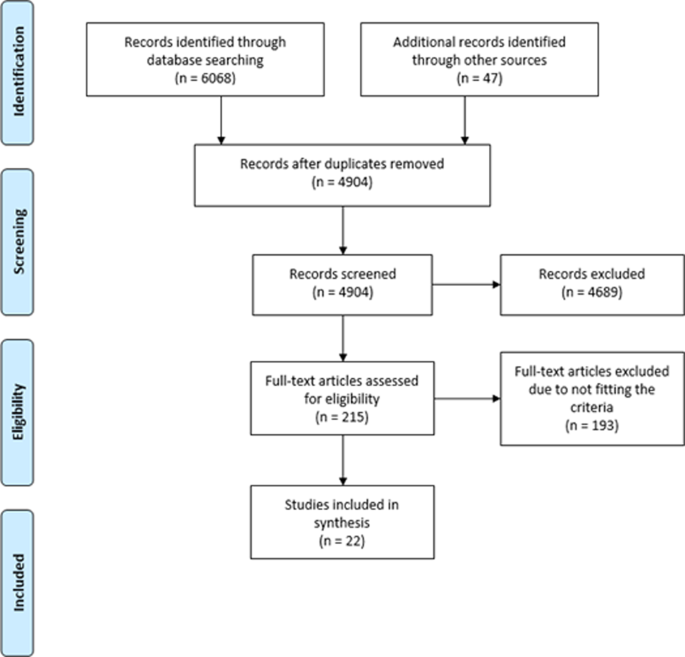

The initial database search identified 7,544 abstracts with none identified elsewhere (Figure 1 ). After the removal of duplicates ( N = 2,672; 35%), a further 7.7% of abstracts were removed due to following exclusion criteria: not research articles ( N = 356; book/book chapter/conference proceedings, etc.); low quality ( N = 158; no abstract, published in non‐peer reviewed journals); were not involving humans ( N = 70). The remaining abstracts ( N = 4,288; 57%) were screened independently by two authors (92% agreement rate on inclusion/exclusion), resulting in 298 (3.9%) articles identified for full‐text screening.

Flow diagram of the systematic review (modified from Moher et al., 2009 )

From the identified abstracts, we were unable to source 12 full‐texts and therefore 286 full‐texts were reviewed independently by two reviewers, with 75% agreement on inclusion/exclusion. A further 202 articles (71%) articles were removed at the full‐text review as they were found to not fit the inclusion criteria, with the final number 84 (29%) of articles included in data extraction. At the data extraction phase, the articles underwent a criteria appraisal (Table 3) and five more articles were removed following an in‐depth analysis due to very vague description of the model or its application. The final number of articles included in data analysis was 79 (28%). The summary details of these articles are included in Table 2 .

Studies identified by systematic review and included in the final analysis grouped by model used

2.5. Quality appraisal

In line with scoping reviews, limited application of quality appraisal criteria was undertaken; and aggregated quality assessments of the dataset are presented rather than study level assessments (Table 3 ).

Quality appraisal of articles included in the scoping review

2.6. Data abstraction and synthesis

Analysis of extracted data was conducted at two levels: descriptive and explorative. Level 1 (descriptive analysis) involved tabulation of basic information such as study design, participant samples and the named models. Level 2 (explorative analysis) involved thematic analysis of narrative data, of the descriptions of identified models and of their visual representations. We used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ) wherein initial coding and the development of candidate themes were conducted independently by two authors, who then met to agree the final thematic map of the findings. Once the themes were agreed, two authors coded the data, while a third author conducted an independent coding check of 10% of the articles. The agreement for the credibility check of the independently coded themes was 83%. Frequency analysis provided the occurrence of each theme across the identified articles, as a reflection of the salience of the theme in the data.

As a validity check, stakeholder consultation was performed by presenting the findings at a national workshop for researchers, policy makers and patient/carer representatives in health services research. A stenographer recorded the workshop and feedback was gathered from attendees to allow reflection on the discussions. No significant changes were made to the components; however, the discussion highlighted the need for some clarity regarding the operational elements and the nature of the interaction between components. This led to some changes in the naming of components and operational elements and more clarity on structure. A visualization, incorporating the revisions from this process is presented in this paper.

3.1. Overview of articles and models

Of the 79 articles included in this scoping review, the majority were published in medical (53%) and nursing (25%) journals, followed by behavioural/psychological journals (7.6%), journals on medical training (6.3%), health services research (5%) and miscellaneous (2.1%). The earliest studies were published in 1985, with 2014 being the latest year included in the search; 70 articles (89%) were published after 2001 and over a third of all articles (35%) were published after 2010. This suggests a relatively recent increase in interest in the issue of knowledge transfer in health research.

In the 79 articles were references to 88 models or frameworks (including multiple occurrences across articles), with 49 unique models/frameworks named and 13 models not explicitly named. Five models were mentioned in multiple articles, with PARiHS being the most frequently cited (Rycroft‐Malone, 2004 ). When it came to the theoretical background of the framework, 19 (24%) articles provided no information, while 24 (30%) referred to previous publications. From the remaining articles, 25 (32%) referred to multiple other models/frameworks or theories and 11 (14%) to a single framework. Over half of the articles indicated the target audience for the KTE ( N = 43, 54%), with the majority proposing the use of the model in multiple stakeholder groups ( N = 32, 41%).

Our quality appraisal focused on fatal flaws, as outlined by Dixon‐Woods et al. (Dixon‐Woods et al., 2006 ). We also rated the level of detail in the description of the framework or its application. The findings highlight several limitations (see Table 3 ). All articles had clear statements of the aims and objectives, a majority (>90%) had a clearly described research design (where appropriate) and a significant proportion (76%) provided sufficient detail to analyse the framework. However, fewer articles (67%) provided a clear account of data analysis and findings or presented data to support their interpretations (40%), which may highlight the need for more critical evaluation of dissemination activities and limitations in the quality of this research.

3.2. Identifying the core components and operational elements of knowledge transfer and exchange

From the thematic analysis, six key themes were identified to represent the core components of KTE.

The first component of KTE—the Message reflects the information to be shared. Within this component, the most common operational element was the idea that the message is needs‐driven . This often‐presented research as a clinical or practical problem, while multiple studies applying the PARiHS framework referred to the research as needs‐ or problem‐based (Kristensen, Borg, & Hounsgaard, 2011 ; Rycroft‐Malone, 2004 ; Tilson & Mickan, 2014 ). The operational elements or attributes of the message as credible and actionable occurred with equal frequency. Research findings being actionable related to its use or application in practice and were particularly evident in articles considering the Ottawa Model of Research Use (Logan & Graham, 1998 ; Logan, Harrison, Graham, Dunn, & Bissonnette, 1999 ; Pronovost, Berenholtz, & Needham, 2008 ). The credibility of the message referred to the use of outcomes that are considered valid (Pronovost et al., 2008 ). Jack and Tonmyr (Jack & Tonmyr, 2008 ) applied Lavis’ model of KTE and referred to the importance of messages containing credible information. Occurring slightly less frequently was the operational element of the message as accessible , which was represented in as translating the knowledge or tailoring it for key stakeholders (Kitson et al., 2013 ; Tugwell, O'Connor, et al., 2006 ). The final operational element noted was that multiple types of message are important , which reflected the use of different research methods to generate messages and the potential for research to have different messages to transfer. For example, the revised PARiHS Framework (Rycroft‐Malone et al., 2002 ) noted that different types of research evidence are required to answer different questions relevant to practice.

The Process component represented the activities intended to implement the transfer of knowledge. This was often identified as a collaborative aspect of KTE, reflecting the “push‐pull” dynamic exchange of information. Taking the operational element of KTE as an interactive exchange, the Research Practice Integration model (Sterling & Weisner, 2006 ) referred to the bidirectional relationship between stakeholders in treatment and research. KTE was described as requiring skilled facilitation, with multiple articles referring to PARiHS model that highlights the importance of this. The KTE processes were also expected to be targeted and timely, stressing the need to target key groups such as policy makers (Aguilar‐Gaxiola et al., 2002b ), recognizing the importance of activities taking place at the right time (Haynes, Hayward, & Lomas, 1995 ).

The Process component also included the operational element of marketing the message, reflecting the need for the communicators (typically the researchers) to communicate in a way that effectively pitched information to their target audience. Herr et al. (Borbas, Morris, McLaughlin, Asinger, & Gobel, 2000 ; Herr, English, & Brown, 2003 ) drew on the Knowledge Development and Application model, discussing the need to ‘get the message out’ through dissemination activities. The KTE process was also recognized to require the support or endorsement of opinion leaders/champions, for example the article by Borbas et al. (Borbas et al., 2000 ) reported on their Healthcare Education and Research Foundation process, which uses clinical opinion leaders to support research implementation, while the Translating Research into Practice model reported by Tschannen et al. (Tschannen, Talsma, Gombert, & Mowry, 2011 ) also highlights the use of opinion leaders in the process. The final operational element reflected the need for KTE to draw on diverse activities, for example Aguilar‐Gaxiola et al. described multiple multifaceted activities as part of research on mental health care for Mexican Americans (Aguilar‐Gaxiola et al., 2002a , 2002b ).

The Stakeholders represent the people involved on either side of the exchange process. This was operationalized into four operational elements: knowledge users, knowledge beneficiaries and multiple stakeholders. The knowledge producers refer predominantly to the researchers themselves (Dufault, 2004 ; Ho et al., 2004 ; Sterling & Weisner, 2006 ); while knowledge users , sometimes referred to as knowledge consumers (Ho et al., 2004 ) represent the most common stakeholders—practitioners and policy makers, positioning them in the context of communities of professional practice, e.g., primary care practitioners (McCaughan, 2005 ). The knowledge beneficiaries represent the wider group of patients and families who benefit from the implementation (Hemmelgarn et al., 2012 ; Jack & Tonmyr, 2008 ). Finally, several papers emphasized that those involved in KTE have multiple stakeholders to consider including patients’ families and the general public (Anderson, Cosby, et al., 1999b ; Ho et al., 2004 ; Orlandi, 1987 ).

The context for KTE was reported at two important levels: local and wider social, economic and cultural. The Local Context, addressing the immediate, often organizational environments, where the transfer would occur, included four operational elements. The most prevalent of these was organizational influence, with organizations and their leaders/managers identified as key influencers in the KTE process. Senior colleagues in organizations were reported as instrumental in the adoption of research knowledge to implement change, (Dobbins, Ciliska, Cockerill, Burnsley, & DiCenso, 2002 ) or support evidence‐based practice (Stetler, 2003 ). Closely linked to this was the operational element of organizational culture, which may be expressed as the attitudes, knowledge and values expressed in the organization. Multiple articles implementing the PARIHS Framework (Helfrich et al., 2010 ) or the Translating Research into Practice model highlighted the importance of organizational culture and the importance of setting organizational standards (Tschannen et al., 2011 ).

Our findings highlighted the need for dedicated resources for KTE activities . For example, the Multisystem Model of Knowledge Integration and Translation, referred to resourcing effective implementation (Palmer & Kramlich, 2011 ), while the Conservation of Resources Theory, recognized the range of resources required and noted that these may differ at different stages of the process (Alvaro et al., 2010 ). The final operational element in this section was readiness for knowledge . One application of PARIHS emphasized receptivity of the context—a factor which is common in many of the articles applying or using this KTE model (Helfrich et al., 2011 ).

The inclusion of the Social, Cultural & Economic Context component recognized the influence of wider environmental factors influencing research and practice. While this was the least frequent theme it was evident in the Evidence‐based Information Circle, designed to help practitioners engage with evidence‐based practice (Thomson‐O'Brien & Moreland, 1998 ). This component included an outer context representing factors that may have an impact on decision making, with specific reference to aspects of the social, cultural and economic context. In the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model the external environment was considered to have an influence on the implementation of research (Feldstein & Glasgow, 2008 ) while in the CFIR model, the outer setting incorporating wider cultural, political and economic factors was explicitly referenced (Damschroder & Hagedorn, 2011 ).

The final component of KTE highlighted the importance of evaluation in the model, with the concept of Evaluating Efficacy expressing the need for a mechanism for evaluation of the success of the knowledge transfer activity. It is interesting to note that, alongside the theme of Social, Cultural and Economic context, this component was least prevalent in the coding of data extracted. The Ottawa Model of Research Use (Logan & Graham, 1998 ; Logan et al., 1999 ) highlighted the importance of evaluating the outcomes of KTE and implementation work, while others referred to the importance of examining the effectiveness of transfer activities (Anderson, Caplan, et al., 1999a ) and the importance of both outcome and process evaluation (Sakala & Mayberry, 2006 ).

3.3. Reflections on the structure of the components

Informed by the discussions at the stakeholder workshop, a visualization incorporating these components is presented in Figure 2 . Also included are the operational elements identified as part of the analysis and the frequency of occurrence of each component and operational element.

Key components of knowledge transfer identified through thematic analysis (with frequencies reported)

Taking the components together the starting point of KTE activity is the knowledge to be transferred ( the Message ). The message is influenced by the Stakeholders, recognizing that there may be multiple groups who may influence the way the message needs to be communicated). Based on the message and the stakeholders the knowledge producer should identify the Processes to be used to ensure the message can be delivered to the stakeholders effectively. Also important is allowing for feedback to come back though the same channels. These interacting components sit in two identified layers, the Local Context and the wider Social, Cultural and Economic Context and highlight the need for researchers to consider how these contexts may have an impact on the Message, Stakeholders and Processes.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to identify key components and related operational elements of KTE, intended to guide researchers’ actions in relation to KTE, in the broader context of implementation. The search identified 79 articles which included an explicit model related to transferring research findings in health settings. These articles were drawn from a range of disciplines, although medicine and nursing were the most common. The publication date range highlights a recent increase in research and dissemination activity in this area. This review identified almost 50 individual models or frameworks, with PARiHS the most frequent. Quality appraisal of the articles highlighted several limitations to the quality of the research; however, few articles were excluded on the basis of a lack of information on the model itself.

The thematic analysis identified six core components of KTE, three of which were commonly present in the articles. The messages to be transferred, the stakeholders and the specific processes by which transfer was achieved were considered in detail. However, the key practical finding lies in the operational elements in these components, which provide more specific and practical guidance for researchers intending to maximize the potential impact of their research. Recognizing that multiple types of message are important highlights the need to be aware of different processes when communicating with different stakeholders. Echoing this, the use of diverse activities as part of the KTE process was rarely evident in articles, perhaps due to the dominance of traditional methods that focus on academic dissemination. Another key finding is the importance of targeted and timely KTE activities. Rather than planning for dissemination at the end of the research process, the evidence presented in this review stresses the need for KTE to be an ongoing activity across the lifetime of the project. While transfer processes were frequently considered in previous studies, few considered multiple processes for a single study, suggesting a simplistic, linear approach to knowledge transfer. This does not reflect the complex non‐linear process of KTE evident across the findings of this review.

Recognizing the context where KTE is to take place is another key finding. While the immediate or local context was considered in more than half of the articles, the issue of the wider social, cultural and economic context was considered in less detail, with no evidence of specific operational elements to guide the researcher when considering the influence of this wider context. The need to consider not just the local but the wider context represents a possible shift in KTE activities. However, given that change in the health sector is often influenced by these wider factors (for example the impact of an economic recession), it is perhaps surprising that these aspects of the context are poorly expressed in existing models. Given the lack of representation of this component in the existing literature we would argue there is a need to increase awareness of its role in KTE and the possible activities that would operationalize this level of the process.

A novel finding is the lack of evidence that process and outcomes of KTE activity is being evaluated by those engaged in the process. In addition, the presence of methodological issues in the studies, such as lack of grounding in data and or detail on analysis and process, further highlights the need for rigorous evaluation of KTE activities. If researchers apply the key principles of evidence‐based practice to their KTE activities, then evaluating the effectiveness of these KTE activities becomes necessary. The focus on audit of practice evident in other areas of the health services (Ivers et al., 2012 ) could and should be extended to KTE, with researchers recognizing the importance of assessing how effective their KTE activities have been in reaching key stakeholders, beyond more traditional metrics such as article citation counts and journal impacts.

It is important to reflect on the methodological quality of this review before final conclusions can be drawn. While the presented findings are based on evidence pre‐2015, there was an exponential rise in the number of studies published since 2015; re‐running the search terms employed in this review yielded over 4000 results, highlighting the urgency in understanding KTE and implementation. While in‐depth analysis of the search terms is beyond the scope of this review, many of the recent studies were based on refining of existing models and clarifying the ways of using them in the process of implementation, e.g., (Harvey & Kitson, 2016 ). There have been significant developments in the conduct and use of systematic reviews in intervention and health research, which allowed for clear guidance in the development of this review. The method of review used was mapped onto the PRISMA procedure as the agreed process for systematic reviews and validity checks such as phases of independent review were included in the screening of articles and in the extraction and analysis of data. In addition, the methodology of the review was peer reviewed and published in advance of the completion of the study. However, there are limitations, not least the lack of engagement with unpublished and policy‐related literature and the timeframe of the search (papers published before January 2015). Despite these limitations we are confident that the rigour evident in the search and analysis provides a basis for confidence in the findings.

5. CONCLUSION

The components identified represent both established and emerging aspects of KTE, with a clear focus on effective ways of transferring research knowledge to care providers and stakeholders and could be used in applied settings and to inform future research. Specific operational elements in these components can directly guide the researcher to maximize the activities in relation to these components. The synthesis of the components and operational elements identified potentially provides a functional model of KTE that could offer researchers the tools to ensure their KTE activities are appropriate and a framework within which to evaluate their actions. Given the process of identification undertaken in this study the authors are tentatively proposing the structure presented in Figure 2 as an Evidence‐based model for the Transfer and Exchange of Research Knowledge (EMTReK).

While requiring further research, EMTReK could act as a resource for researchers planning KTE activities, with this review establishing an initial evidence‐base for the components and the operational evidence. We are conscious that the components and operational elements presented are not new, with each one less or more evident in the articles reviewed. The real potential for contribution lies in its focus on operational elements that may serve as a practical guide for researchers. To conduct an initial exploration of the model we have conducted a series of case studies where healthcare researchers applied the model to their own KTE activities. Initial findings are positive and highlight the need to develop a process guide to complement the description of the model presented in this article. This could be particularly important if there is increased interest in routine evaluation of KTE activities. However, there is a need for further evaluation of the EMTReK model (including the operational elements) before a definitive statement can be made about its contribution.

We recommend that researchers consider EMTReK as a possible functional model of KTE in health services research to ensure that research is conducted with knowledge transfer in mind from the earliest phases of the process. We also recommend that researchers develop evaluation strategies to both assess their activities and to provide feedback on the potential contribution of this model.

6. DECLARATIONS

- Ethics approval and consent to participate—Approval was not required given the documentary nature of the study and the lack of human participants (see www.ucd.i.e/researchethics ).

- Availability of data and material—The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study (namely the database of articles and extracted data) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Authors’ contributions: LP, SG and GWK designed the study and conducted the review. SG and CT conducted the analysis of model components, LP conducted credibility checks. LP and SG drafted the article. All authors reviewed multiple drafts of the article.

7. REGISTRATION

As a scoping review the study was not registered, though the protocol of the review was published (PMID: 25739936; https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12642 ).

8. IMPACT STATEMENT

- Through rigorous synthesis of evidence from a range of disciplines, this review identified key components and related operational elements of knowledge transfer and exchange (KTE) that may guide researchers’ actions in KTE in the broader context of implementation.

- The components represent established and emerging aspects of KTE and the specific operational elements are positioned to guide the KTE activities in applied settings.

- As a result, we propose that these components may represent a functional model of KTE—the Evidence‐based model for the Transfer and Exchange of Research Knowledge (EMTReK), highlighting the elements for consideration to ensure KTE activities are appropriate and as a framework where to evaluate their impact.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE ( http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/ )]:

- substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Supporting information

Acknowledgements.

The authors thank the All Ireland Institute of Hospice & Palliative Care who funded the research, Geraldine Boland who supported the data extraction and reliability checks, and Mary Jane Brown and Cathy Payne who provided comments on the research.

Prihodova L, Guerin S, Tunney C, Kernohan WG. Key components of knowledge transfer and exchange in health services research: Findings from a systematic scoping review . J Adv Nurs . 2019; 75 :313–326. 10.1111/jan.13836 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

This research was funded by the All Ireland Institute of Hospice & Palliative Care. The funding body reviewed and commented on the proposal for the research but were not involved in any aspect of the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data

- Aguilar‐Gaxiola, S. A. , Zelezny, L. , Garcia, B. , Edmondson, C. , Alejo‐Garcia, C. , & Vega, W. A. (2002a). Translating research into action: Reducing disparities in mental health care for Mexican Americans . Psychiatric Services , 53 ( 12 ), 1563–1568. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1563 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aguilar‐Gaxiola, S. A. , Zelezny, L. , Garcia, B. , Edmondson, C. , Alejo‐Garcia, C. , & Vega, W. A. (2002b). Mental health care for Latinos: Translating research into action: Reducing disparities in mental health care for Mexican Americans . Psychiatric Services , 53 ( 12 ), 1563–1568. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1563 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aguilar‐Gaxiola, S. A. , Zelezny, L. , Garcia, B. , Edmondson, C. , Alejo‐Garcia, C. , & Vega, W. A. (2002c) Translating research into action: Reducing disparities in mental health care for Mexican Americans . Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) , 53 ( 12 ), 1563–1568. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1563 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alkema, G. E. , & Frey, D. (2006). Implications of translating research into practice: A medication management intervention . Home Health Care Services Quarterly , 25 ( 1–2 ), 33–54. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alvaro, C. , Lyons, R. F. , Warner, G. , Hobfoll, S. E. , Martens, P. J. , Labonte, R. , & Brown, R. E. (2010). Conservation of resources theory and research use in health systems . Implementation Science , 5 , 79 10.1186/1748-5908-5-79 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ammentorp, J. , & Kofoed, P. E. (2011). Research in communication skills training translated into practice in a large organization: A proactive use of the RE‐AIM framework . Patient Education and Counseling , 82 , 482–487. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, S. , Allen, P. , Peckham, S. , & Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services . Health Res Policy Syst , 6 , 7 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, L. A. , Caplan, L. S. , Buist, D. S. , Newton, K. M. , Curry, S. J. , Scholes, D. , & LaCroix, A. Z. (1999a) Perceived barriers and recommendations concerning hormone replacement therapy counseling among primary care providers . Menopause (New York, N.Y.) , 6 ( 2 ), 161–166. 10.1097/00042192-199906020-00014 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, M. , Cosby, J. , Swan, B. , Moore, H. , & Broekhoven, M. (1999b). The use of research in local health service agencies . Social Science & Medicine , 49 , 1007–1019. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00179-3 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework . International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 8 ( 1 ), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Armstrong, R. , Waters, E. , Roberts, H. , Oliver, S. , & Popay, J. (2006). The role and theoretical evolution of knowledge translation and exchange in public health . Journal of Public Health , 28 ( 4 ), 384–389. 10.1093/pubmed/fdl072 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Atchan, M. , Davis, D. , & Foureur, M. (2014). Applying a knowledge translation model to the uptake of the Baby Friendly Health Initiative in the Australian health care system . Women and Birth , 27 , 79–85. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, A. , Bergman, D. A. , Rahm, A. K. , Dearing, J. W. , & Glasgow, R. E. (2009). Using implementation and dissemination concepts to spread 21st‐century well‐child care at a health maintenance organization . Permanente Journal , 13 ( 3 ), 10–18. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackwood, B. (2003). Can protocolised‐weaning developed in the United States transfer to the United Kingdom context: A discussion . Intensive and Critical Care Nursing , 19 ( 4 ), 215–225. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boratgis, G. , Broderick, S. , Callahan, M. , Combes, J. , Lannon, C. , Mebane‐Sims, I. , … Watt, A. (2007). Disseminating QI interventions… quality improvement . Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety , 33 ( 12 ), 48–65. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borbas, C. , Morris, N. , McLaughlin, B. , Asinger, R. , & Gobel, F. (2000). The role of clinical opinion leaders in guideline implementation and quality improvement . Chest , 118 ( 2 Suppl ), 24S–32S. 10.1378/chest.118.2_suppl.24S [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3 ( 2 ), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown, D. , & McCormack, B. (2005). Developing postoperative pain management: Utilising the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework . Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing , 2 , 131–141. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capasso, V. , Collins, J. , Griffith, C. , Lasala, C. A. , Kilroy, S. , Martin, A. T. , … Wood, S. L. (2009). Outcomes of a clinical nurse specialist‐initiated wound care education program using the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services Framework . Clinical Nurse Specialist , 23 , 252–257. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Damschroder, L. J. , Aron, D. C. , Keith, R. E. , Kirsh, S. R. , Alexander, J. A. , & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science . Implementation Science , 4 , 15 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Damschroder, L. J. , & Hagedorn, H. J. (2011). A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment . Psychology of Addictive Behaviors , 25 , 194–205. 10.1037/a0022284 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- D'Andreta, D. , Scarbrough, H. , & Evans, S. (2013). The enactment of knowledge translation: A study of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care initiative within the English National Health Service . Journal of Health Services Research and Policy , 18 ( 3 ), 40–52. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dixon‐Woods, M. , Cavers, D. , Agarwal, S. , Annandale, E. , Arthur, A. , Harvey, J. , … Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups . BMC Medical Research Methodology , 6 , 35 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dobbins, M. , Ciliska, D. , Cockerill, R. , Burnsley, J. , & DiCenso, A. (2002). A framework for the dissemination and utilization of research for health‐care policy and practice . Online Journal of Knowledge Synthesis for Nursing , 9 ( 7 ), 12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donaldson, N. E. , Rutledge, D. N. , & Ashley, J. (2004). Outcomes of adoption: Measuring evidence uptake by individuals and organizations . Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing , 1 , s41–s51. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Doran, D. M. , & Sidani, S. (2007). Outcomes‐focused knowledge translation: A framework for knowledge translation and patient outcomes improvement . Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing , 4 , 3–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Douglas, M. L. , McGhan, S. L. , Tougas, D. , Fenton, N. , Sarin, C. , Latycheva, O. , & Befus, A. D. (2013). Asthma education program for First Nations children: An exemplar of the Knowledge‐to‐Action Framework . Canadian Respiratory Journal , 20 , 295–300. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dufault, M. (2004). Testing a collaborative research utilization model to translate best practices in pain management . Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing , 1 , S26–S32. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04049.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dzewaltowski, D. A. , Glasgow, R. G. , Klesges, L. M. , Estabrooks, P. A. , & Brock, E. (2004). RE‐AIM: Evidence‐based standards and a web resource to improve translation of research into practice . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 28 ( 2 ), 75–80. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliott, S. J. , O'Loughlin, J. , Robinson, K. , Eyles, J. , Cameron, R. , Harvey, D. , … Gelskey, D. (2003). Conceptualizing dissemination research and activity: The case of the Canadian Heart Health Initiative . Health Education and Behaviour , 30 ( 3 ), 267–282, 283–286. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis, I. , Howard, P. , Larson, A. , & Robertson, J. (2005). From workshop to work practice: An exploration of context and facilitation in the development of evidence‐based practice . Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing , 2 , 84–93. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Estabrooks, C. A. , Squires, J. E. , Cummings, G. G. , Birdsell, J. M. , & Norton, P. G. (2009). Development and assessment of the Alberta Context Tool . Bmc Health Services Research , 9 , 234 10.1186/1472-6963-9-234 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]