Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

Nursing Resources : Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Table of Evidence

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Reliability

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

Definitions

In an experiment, the independent variable is the variable that is varied or manipulated by the researcher.

The dependent variable is the response that is measured.

For example:

- << Previous: Cohort vs Case studies

- Next: Sampling Methods and Statistics >>

- Last Updated: Mar 19, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/nursing

Kraemer Family Library

How to recognize nurs study methodology: independent | dependent variables.

- Primary | Secondary

- Observational | Experimental

- Cross Sectional | Longitudinal

- Prospective | Retrospective

- Independent | Dependent Variables

Independent v Dependent Variables

Variables are any characteristics in the study that can take on different values. The main difference between independent and dependent variables is cause and effect. The independent variable is not expected to be impacted by the study (it's independent), but to cause the difference in the dependent variable. The dependent variable is the effect. The dependent variable expected to change because of the independent variable (it depends on the other factors involved).

Independent Variables - What to look for

Is this a variable that the researchers deliberately introduced or that would have occurred regardless of the study?

The independent variable is the cause, not the effect. So if researchers introduce something in the experiment, like an intervention, that's the independent variable. For observational studies, the independent variable is what was already present in the patients before the outcome that's being measured.

An observational study wants to know if patients who worked high stress jobs had more strokes. Having a high stress job is the independent variable. It's not really the variable that's being measured. It's the variable that may or may not cause strokes.

An experimental study wants to know if training soccer players on knee stability exercises reduces the number of injuries in a season. The knee stability training is the independent variable. Here, the researchers deliberately introduced training on knee stability exercises. It's not what they want to measure; they want to measure injuries. But this variable that they've introduced is what may or may not cause a reduction in injuries.

Dependent Variables - What to look for

Is this the variable that is being studied/measured?

The easiest way to know what is the dependent variable is to look at what the study is trying to measure. That's the dependent variable, it's what the researchers expect will be impacted by other factors in the study, it's the factor that they're wanting to measure.

If this is an experimental study, is this the variable that would be impacted by the intervention?

The dependent variable depends on the other variables. It is the thing that will be affected by the other variables in the study.

An observational study wants to know if patients who worked high stress jobs had more strokes. Having or not having a stroke is the dependent variable.

An experimental study wants to know if training soccer players on knee stability exercises reduces the number of injuries in a season. The number of injuries in the season is the dependent variable.

- << Previous: Prospective | Retrospective

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 2:30 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uccs.edu/nurs-methods

Need Research Assistance? Get Help

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 2, Issue 4

- The fundamentals of quantitative measurement

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Donna Ciliska , RN, PhD * ,

- Nicky Cullum , RN, PhD 2 ,

- Alba Dicenso , RN, PhD *

- * School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- 2 Centre for Evidence Based Nursing, Department of Health Studies, University of York, York, UK

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebn.2.4.100

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

The main purpose of the EBN Notebook is to equip readers with the necessary skills to critically appraise primary research studies and to provide a more detailed description of some of the methodological issues that arise in the papers we abstract. In the July 1999 issue of Evidence-Based Nursing, the EBN Notebook explored the concept of sampling. 1 In this issue we will provide a basic introduction to quantitative measurement of health outcomes, which may be assessed in studies of treatment, causation, prognosis, diagnosis, and in economic evaluations. Examples of health related outcomes are blood pressure, quality of life, patient satisfaction, and costs.

Health can be measured in many different ways; the various aspects of health that can be measured are referred to as variables . 2 For example, in the treatment study by Dunn et al in this issue of Evidence-Based Nursing (p 117), the interventions (known as the independent variables) were lifestyle and structured exercise programmes and the outcomes (known as the dependent variables) were physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness. In a treatment study, the independent variables are those that are under the control of the investigator, and the dependent variables are the outcomes that may be influenced by the independent variable. In a causation study, the investigator relies on natural variation between both variables and looks for a relation between the 2 variables. For example, when determining whether smoking causes lung cancer, smoking is the independent variable and lung cancer is the dependent variable. In the abstracts included in Evidence-Based Nursing , the independent variables are identified under the “intervention” section for treatment studies and under the “assessment of risk factors” section for causation studies. The dependent variables are identified under the “main outcome measures” section.

Types of variables

Variables can be classified as nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio variables. Nominal (categorical) variables are simply names of categories. Some nominal variables (referred to as dichotomous variables) have only 2 possible values, such as sex (men or women), survival (dead or alive), or whether a specific feature is present or absent (eg, diabetes or no diabetes); others may have several possible values, such as race (white, black, Hispanic, and others). The actual number of categories can be determined by the researcher; for example, race can be defined as 2 options (black or non-black) or by several possible options. No hierarchy is presumed with nominal data—that is, being alive is not twice as good as being dead (although most patients would argue with us about that one). In contrast, ordinal variables are sets of “ordered” categories. 2 For example, patients are often asked to rate the severity of their pain on a scale of 0–10, where 0 is no pain and 10 is unbearable, excruciating pain. Although we can safely say that a pain rating of 8 is worse than a pain rating of 5, we do not really know how much these 2 ratings differ because we do not know the size of the intervals between each rating. 2 Ordinal scales have also been used to grade pressure sore severity and to classify the staging of various cancers (eg, stage I, II, or III). Interval variables consist of an ordered set of categories, with the additional requirement that the categories form a series of intervals that are all exactly the same size. Thus, the difference between a temperature of 37°C and 38°C is 1 degree, and between 38°C and 39°C is 1 degree, and so on. However, an interval scale does not have an absolute zero point that indicates complete absence of the variable being measured. Because there is no absolute zero point on an interval scale, ratios of values are not meaningful—that is, 2 values cannot be compared by claiming that one is “twice as large” as another. A ratio variable has all the features of an interval variable but adds an absolute zero point, which indicates none (complete absence) of the variable being measured. The advantage of an absolute zero is that ratios of numbers on the scale reflect ratios of magnitude for the variable being measured. 3 To illustrate, 100°C is not twice as hot as 50°C (interval data) but 100 cm is twice as long as 50 cm, and a pulse of 80 beats per minute is twice a pulse rate of 40 beats per minute (ratio data).

Issues in measurement

It is important to remember that most measurements in healthcare research encapsulate several things: the “real” or true value of the variable that is being measured; the variability of the measure; the accuracy of the instrument with which we are measuring; and perhaps the position of the patient or the skill and expectations of the person doing the measurement. Some of these elements are within the control of the measurer (eg, ensuring that a scale is at 0 before we weigh someone), whereas other elements are not (eg, a patient's blood pressure varies by time of day; therefore researchers try to assess blood pressure at the same time each day).

Some measures are more objective than others and are less likely to be influenced by human error or bias. Examples of objective measures include all cause mortality (ie, whether one is “dead” or “alive”) and serum cholesterol concentrations. In contrast, subjective measures may be influenced by the perception of the individual doing the measurement (eg, patient self reported pain ratings). Most paper and pencil type questionnaires are subjective measures. The Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care described in the diagnosis study by Steer et al in this issue (p 126) is an example of a subjective paper and pencil questionnaire.

Frequency counts, such as incidence or prevalence, are often used when we want to know the extent of a disease or condition in a population. Others may be more interested in the beneficial and harmful effects of an intervention, such as differences in the rates of sexually transmitted diseases after a behavioural intervention provided to minority women (see the treatment study by Shain et al p 121).

What measurement issues should I look for when reading an article?

Are the measures reliable and valid.

These are 2 critically important properties of measurement. Reliability refers to the degree to which a measure gives the same result twice (or more) under similar circumstances, and may relate to the measure being used or the people using it. For example, if a patient's blood pressure is measured every 4 minutes on the same arm, by the same nurse, and the patient is not subject to any intervention such as activity or medication, you would expect to get similar sphygmomanometer readings. The extent to which repeated readings are similar is called reliability. Assessment of the similarity of repeated readings taken by the same nurse provides a measure of intra-rater or within-rater reliability . You would also hope that 2 different nurses measuring the same patient's blood pressure under the same circumstances would get similar readings. The extent to which the readings from 2 different nurses are similar is known as inter-rater or between-rater reliability .

Validity is the ability of a measurement tool to accurately measure what it is intended to measure. There are many different types of validity, but one of the most important is criterion related validity , which requires comparison of a given measure with a gold standard , or the best existing measure of the variable. 4 In the study by Steer et al in this issue (p 126), the results obtained from the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care were compared with the results of a standardised interview based on DSM-IV criteria and conducted by a physician. The interview results were considered to be the gold standard. Other examples of gold standards are direct central venous pressure readings for sphygmomanometer measures of blood pressure and serum hormone concentrations for the results of a urine test for pregnancy.

IS THE MEASURE SUBJECT TO BIAS?

There are several potential sources of bias. It is not important to remember what they are called, but you should be able to recognise sources of bias in a study. One way that bias can occur in a study is when the healthcare providers, patients, and data collectors participating in an intervention study are not masked or blinded to the treatment allocation. In an ideal world, studies would be “triple blinded”—that is, the healthcare provider delivering the intervention, the patient, and the research staff measuring the outcomes would not know which treatment the patient was receiving. Although triple blinding is possible in randomised trials evaluating new drugs, it is far more difficult to achieve in evaluations of most nursing interventions. Often, neither the nurses delivering the intervention nor the patients receiving the intervention can be masked (eg, nurses know that they are providing a patient education intervention and patients know that they are receiving it). In such studies, it is often possible, however, to mask the person measuring the outcome. By ensuring that the person measuring the outcome is masked to a patient's group allocation, researchers try to minimise the bias that could be introduced by unconscious adjustments assessors might make if they were aware of a patient's group allocation. For example, in the study by Dunn et al (p 117), which compared 2 interventions to increase physical activity, the people who assessed blood pressure, pulse rate, and body fat did not know which intervention participants had received. If they had known, this might have influenced their perceptions when they were doing the measurements, particularly if they had a clear opinion about which intervention was most effective. Similarly, participants reporting their own level of activity might alter their reporting of actual behaviour depending on whether they enjoyed or if they wished they had been allocated to a different group. Beginning with this issue of Evidence-Based Nursing , we will specify in the description of the design, whether the study was unblinded, single, or double blinded and who was blinded.

Another common type of bias is social desirability bias , in which people's responses to questions may reflect their desire to under report their socially unfavourable habits, such as the number of cigarettes smoked, illicit drug use, or unsafe sexual practices. Conversely, people may overestimate what they perceive to be socially desirable practices, such as exercise participation or daily intake of fruits and vegetables.

A third type of bias is recall bias , which acknowledges that human memory is fallible. Reports of seat belt use 5 years ago or fibre intake last month, for example, are not as accurate as concurrent or prospective measurements, where seat belt use or diet diaries are recorded on a daily basis.

Investigators often use strategies to try to overcome these potential biases. These strategies include having outcome assessors who do not know the purpose of a study nor which intervention the patient received; having study participants complete self report questionnaires in a private area, ensuring that their responses to sensitive or potentially embarrassing questions are confidential; and collecting information on a prospective basis (ie, as it happens), rather than on a retrospective basis (historically).

In summary, readers of research reports need to consider the type of measures that are used, the reliability and validity of the measures, and methods used to minimise bias in the measurement of outcomes. These are some of the elements considered when selecting studies for abstraction in Evidence-Based Nursing . In the next issue of the journal, the EBN Notebook will address how study outcomes are analysed and the appropriateness of the statistical test for the type of data collected.

- ↵ Thomson C. If you could just provide me with a sample: examining sampling in qualitative and quantitative research papers [editorial]. Evidence-Based Nursing 1999 Jul; 2 : 68 –70. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Norman GT, Streiner DL. PDQ statistics . Toronto: BC Decker, 1986.

- ↵ Gravetter FJ, Wallnau LB. Essentials of statistics for the behavioral sciences . California: Brooks/Cole, 1998.

- ↵ Anthony D. Understanding advanced statistics. A guide for nurses and health care researchers . Volume 4. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

University of Illinois Chicago

University library, search uic library collections.

Find items in UIC Library collections, including books, articles, databases and more.

Advanced Search

Search UIC Library Website

Find items on the UIC Library website, including research guides, help articles, events and website pages.

- Search Collections

- Search Website

Nursing Experts: Translating the Evidence - Public Health Nursing

- Public Health Nursing

- The EBP Process

- Finding Evidence

- Finding Health Statistics: Going Beyond the Literature

- Appraising the Evidence

- Translating the Evidence

- Learning, Leadership, and Professionalism

- Sharing Evidence & Results

- NExT Online Course for Public Health Nursing

- Mobile Resources

- Go To NExT Home

- Go To Acute & Ambulatory Nursing Care

- Go To Public Health Professionals This link opens in a new window

Appraisal Concepts - Validity & Reliability

What is validity?

Internal validity is the extent to which the study demonstrated a cause-effect relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

External validity is the extent to which one may safely generalize from the sample studied to the defined target population and to other populations.

What is reliability?

Reliability is the extent to which the results of the study are replicable. The research methodology should be described in detail so that the experiment could be repeated with similar results.

Scientific Experiment Terminology

Hypothesis - a statement that is believed to be true but has not yet been tested.

Independent variable - the component of an experiment that is controlled by the researcher (for example - a new therapy).

Dependent variable - the component of an experiment that changes, or not, as a result of the independent variable (for example - the existence of a disease).

Bias - prejudice or the lack of neutrality. A systematic deviation from the truth that affects the conclusions and occurs in the process or design of the research.

Confounding - a mixing of the effects within an experiment because the variables have not been sufficiently separated. Possible confounding variables should be discussed in the report of the research.

See also Study Design Terminology from the Levels of Evidence tab in the EBM Guide .

Sample Questions for Evaluating a Study

- Has the study's aim been clearly stated?

- Does the sample accurately reflect the population?

- Has the sampling method and size been described and justified?

- Have exclusions been stated?

- Is the control group easily identified?

- Is the loss to follow-up detailed?

- Can the results be replicated?

- Are there confounding factors?

- Are the conclusions logical?

- Can the results be extrapolated to other populations?

Standards for the Reporting of Scientific/Medical Research:

- CONSORT Statement

- EQUATOR Network

- MOOSE Consensus Statement

- PRISMA Statement more... less... formerly called QUORUM

- SQUIRE Guidelines

- TREND Statement more... less... from the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC)

Online Appraisal Resources:

- NExT Appraisal Tool

- CASP Checklists Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools for reading research

- Centre for Evidence Based Medicine - Critical Appraisal

- EBM and Decision Tools Alan Schwartz - UIC College of Medicine

- EBM Librarian - Appraising the Evidence

- Joanna Briggs Institute - Critical Appraisal Tools

- UIC College of Nursing - Appraising your evidence guide

- << Previous: Finding Health Statistics: Going Beyond the Literature

- Next: Translating the Evidence >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.uic.edu/NExT

- Skip to Guides Search

- Skip to breadcrumb

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

- Skip to chat link

- Report accessibility issues and get help

- Go to Penn Libraries Home

- Go to Franklin catalog

Resources for Nursing Students in Research Courses

- Critical Appraisal Tutorials

- Resources for Reporting Study Types

- Table of Evidence Resources

- Biostatistics Resources: Research Methods, Study Results & More

- Research Design

- Independent & Dependent Variables

- Resources for Understanding Qualitative & Quantitive Studies

- Type I and Type II Errors

- Writing and Publishing Resources

- Resources on Integrative Reviews

- Evidence Levels & Quality Rating

- Using Boolean Connectors & Other Options for Effective Database Searching

- Special Resources for Anesthesia

- Resource Guide for Clinicians

- Resources on Literature Searching

- Guide to Library Resources for DNP Students

- Evidence-Based Practice: PICO

- Finding Tests

Independent versus Dependent Variables

- Identify Independent and Dependent Variables

- Independent vs Dependent Variables Discusses the difference between independent variables and dependent variables, while exploring proper design of a controlled experiment. Near the end of the video are review questions to check your understanding.

- Video: INTERACTIVE: Part 1: Identify the Independent and Dependent Variables with the MythBusters!

Clinical & Graduate Research Liaison

Integrative Review Resources

- << Previous: Research Design

- Next: Resources for Understanding Qualitative & Quantitive Studies >>

- Last Updated: Apr 20, 2024 2:03 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.upenn.edu/NursingResearch

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Definitions

Dependent Variable The variable that depends on other factors that are measured. These variables are expected to change as a result of an experimental manipulation of the independent variable or variables. It is the presumed effect.

Independent Variable The variable that is stable and unaffected by the other variables you are trying to measure. It refers to the condition of an experiment that is systematically manipulated by the investigator. It is the presumed cause.

Cramer, Duncan and Dennis Howitt. The SAGE Dictionary of Statistics . London: SAGE, 2004; Penslar, Robin Levin and Joan P. Porter. Institutional Review Board Guidebook: Introduction . Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2010; "What are Dependent and Independent Variables?" Graphic Tutorial.

Identifying Dependent and Independent Variables

Don't feel bad if you are confused about what is the dependent variable and what is the independent variable in social and behavioral sciences research . However, it's important that you learn the difference because framing a study using these variables is a common approach to organizing the elements of a social sciences research study in order to discover relevant and meaningful results. Specifically, it is important for these two reasons:

- You need to understand and be able to evaluate their application in other people's research.

- You need to apply them correctly in your own research.

A variable in research simply refers to a person, place, thing, or phenomenon that you are trying to measure in some way. The best way to understand the difference between a dependent and independent variable is that the meaning of each is implied by what the words tell us about the variable you are using. You can do this with a simple exercise from the website, Graphic Tutorial. Take the sentence, "The [independent variable] causes a change in [dependent variable] and it is not possible that [dependent variable] could cause a change in [independent variable]." Insert the names of variables you are using in the sentence in the way that makes the most sense. This will help you identify each type of variable. If you're still not sure, consult with your professor before you begin to write.

Fan, Shihe. "Independent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design. Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 592-594; "What are Dependent and Independent Variables?" Graphic Tutorial; Salkind, Neil J. "Dependent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 348-349;

Structure and Writing Style

The process of examining a research problem in the social and behavioral sciences is often framed around methods of analysis that compare, contrast, correlate, average, or integrate relationships between or among variables . Techniques include associations, sampling, random selection, and blind selection. Designation of the dependent and independent variable involves unpacking the research problem in a way that identifies a general cause and effect and classifying these variables as either independent or dependent.

The variables should be outlined in the introduction of your paper and explained in more detail in the methods section . There are no rules about the structure and style for writing about independent or dependent variables but, as with any academic writing, clarity and being succinct is most important.

After you have described the research problem and its significance in relation to prior research, explain why you have chosen to examine the problem using a method of analysis that investigates the relationships between or among independent and dependent variables . State what it is about the research problem that lends itself to this type of analysis. For example, if you are investigating the relationship between corporate environmental sustainability efforts [the independent variable] and dependent variables associated with measuring employee satisfaction at work using a survey instrument, you would first identify each variable and then provide background information about the variables. What is meant by "environmental sustainability"? Are you looking at a particular company [e.g., General Motors] or are you investigating an industry [e.g., the meat packing industry]? Why is employee satisfaction in the workplace important? How does a company make their employees aware of sustainability efforts and why would a company even care that its employees know about these efforts?

Identify each variable for the reader and define each . In the introduction, this information can be presented in a paragraph or two when you describe how you are going to study the research problem. In the methods section, you build on the literature review of prior studies about the research problem to describe in detail background about each variable, breaking each down for measurement and analysis. For example, what activities do you examine that reflect a company's commitment to environmental sustainability? Levels of employee satisfaction can be measured by a survey that asks about things like volunteerism or a desire to stay at the company for a long time.

The structure and writing style of describing the variables and their application to analyzing the research problem should be stated and unpacked in such a way that the reader obtains a clear understanding of the relationships between the variables and why they are important. This is also important so that the study can be replicated in the future using the same variables but applied in a different way.

Fan, Shihe. "Independent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design. Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 592-594; "What are Dependent and Independent Variables?" Graphic Tutorial; “Case Example for Independent and Dependent Variables.” ORI Curriculum Examples. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Research Integrity; Salkind, Neil J. "Dependent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 348-349; “Independent Variables and Dependent Variables.” Karl L. Wuensch, Department of Psychology, East Carolina University [posted email exchange]; “Variables.” Elements of Research. Dr. Camille Nebeker, San Diego State University.

- << Previous: Design Flaws to Avoid

- Next: Glossary of Research Terms >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 8:59 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Intervention research: establishing fidelity of the independent variable in nursing clinical trials

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 48109, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 17179874

- DOI: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00007

Background: Internal validity of a randomized clinical trial of a nursing intervention is dependent on intervention fidelity. Although several methods have been developed, evaluating audio or audiovisual tapes for prescribed and proscribed interventionist behaviors is considered the gold standard test of treatment fidelity. This approach requires development of a psychometrically sound instrument to meaningfully categorize and quantify interventionist behaviors.

Objective: To outline critical steps necessary to develop a treatment fidelity instrument.

Methods: A comprehensive literature review was conducted to determine procedures used by other researchers. The literature review produced five quantitative studies of treatment fidelity, all in the field of psychotherapy, and two replication studies. A synthesis of methodologies across studies combined with researchers' experiences resulted in identification of the steps necessary to develop a treatment fidelity measure.

Results: Seven sequential steps were identified as essential to the development of a valid and reliable measure of treatment fidelity. These steps include (a) identification of the essential elements of the experimental and control treatment modalities; (b) construction of scale items; (c) development of item scaling; (d) identification of the units for coding; (e) item testing and revision; (f) specification of rater qualifications and development of rater training program; and (g) development and completion of pilot testing to test psychometric properties. Development of the Possibilities Project Psychotherapy Coding Questionnaire is described as an illustration of the seven-step process.

Discussion: The results show the essential steps that are unique to the development of treatment fidelity measures and show the feasibility of using these steps to construct a psychometrically sound treatment-specific fidelity measure.

Publication types

- Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural

- Anorexia Nervosa / therapy

- Bulimia Nervosa / therapy

- Clinical Nursing Research / methods*

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Observer Variation

- Pilot Projects

- Psychometrics / methods*

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic / methods*

- Reproducibility of Results

- Research Design*

Grants and funding

- 1 R55 NR 05277-01/NR/NINR NIH HHS/United States

- R01 05277-01/PHS HHS/United States

Nursing 465: Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- EBP & Levels of Evidence

- Evidence-Based Research Sources

- Health Statistics

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Types of Studies

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Table of Evidence

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Nursing Related Apps

- Distance & Online Library Services

Definitions

In an experiment, the independent variable is the variable that is varied or manipulated by the researcher.

The dependent variable is the response that is measured.

For example:

- << Previous: Study Designs

- Next: Types of Studies >>

- Last Updated: Jan 31, 2024 10:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sdstate.edu/c.php?g=1177663

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

Developing a survey to measure nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, influences, and willingness to be involved in Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): a mixed method modified e-Delphi study

- Jocelyn Schroeder 1 ,

- Barbara Pesut 1 , 2 ,

- Lise Olsen 2 ,

- Nelly D. Oelke 2 &

- Helen Sharp 2

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 326 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) was legalized in Canada in 2016. Canada’s legislation is the first to permit Nurse Practitioners (NP) to serve as independent MAiD assessors and providers. Registered Nurses’ (RN) also have important roles in MAiD that include MAiD care coordination; client and family teaching and support, MAiD procedural quality; healthcare provider and public education; and bereavement care for family. Nurses have a right under the law to conscientious objection to participating in MAiD. Therefore, it is essential to prepare nurses in their entry-level education for the practice implications and moral complexities inherent in this practice. Knowing what nursing students think about MAiD is a critical first step. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a survey to measure nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, influences, and willingness to be involved in MAiD in the Canadian context.

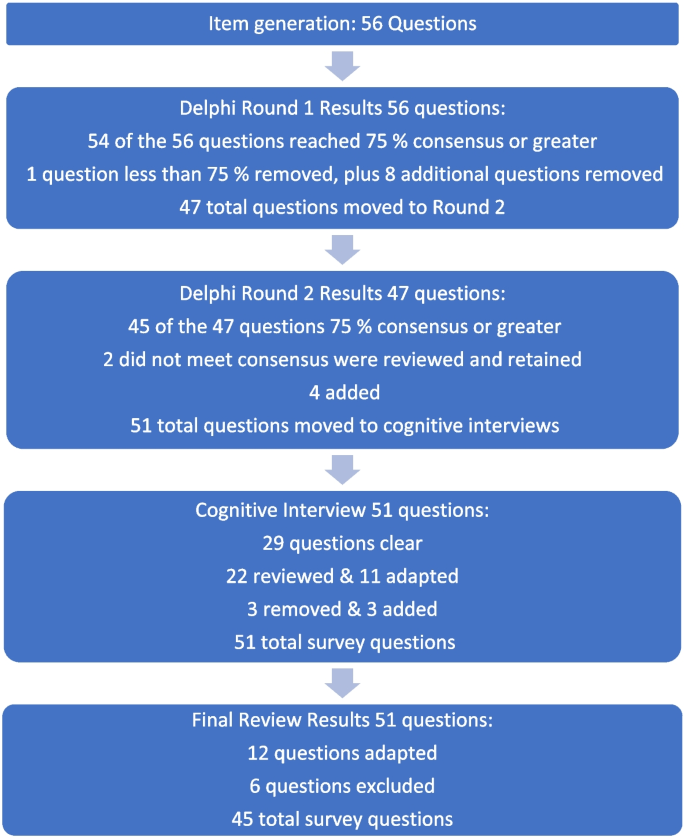

The design was a mixed-method, modified e-Delphi method that entailed item generation from the literature, item refinement through a 2 round survey of an expert faculty panel, and item validation through a cognitive focus group interview with nursing students. The settings were a University located in an urban area and a College located in a rural area in Western Canada.

During phase 1, a 56-item survey was developed from existing literature that included demographic items and items designed to measure experience with death and dying (including MAiD), education and preparation, attitudes and beliefs, influences on those beliefs, and anticipated future involvement. During phase 2, an expert faculty panel reviewed, modified, and prioritized the items yielding 51 items. During phase 3, a sample of nursing students further evaluated and modified the language in the survey to aid readability and comprehension. The final survey consists of 45 items including 4 case studies.

Systematic evaluation of knowledge-to-date coupled with stakeholder perspectives supports robust survey design. This study yielded a survey to assess nursing students’ attitudes toward MAiD in a Canadian context.

The survey is appropriate for use in education and research to measure knowledge and attitudes about MAiD among nurse trainees and can be a helpful step in preparing nursing students for entry-level practice.

Peer Review reports

Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) is permitted under an amendment to Canada’s Criminal Code which was passed in 2016 [ 1 ]. MAiD is defined in the legislation as both self-administered and clinician-administered medication for the purpose of causing death. In the 2016 Bill C-14 legislation one of the eligibility criteria was that an applicant for MAiD must have a reasonably foreseeable natural death although this term was not defined. It was left to the clinical judgement of MAiD assessors and providers to determine the time frame that constitutes reasonably foreseeable [ 2 ]. However, in 2021 under Bill C-7, the eligibility criteria for MAiD were changed to allow individuals with irreversible medical conditions, declining health, and suffering, but whose natural death was not reasonably foreseeable, to receive MAiD [ 3 ]. This population of MAiD applicants are referred to as Track 2 MAiD (those whose natural death is foreseeable are referred to as Track 1). Track 2 applicants are subject to additional safeguards under the 2021 C-7 legislation.

Three additional proposed changes to the legislation have been extensively studied by Canadian Expert Panels (Council of Canadian Academics [CCA]) [ 4 , 5 , 6 ] First, under the legislation that defines Track 2, individuals with mental disease as their sole underlying medical condition may apply for MAiD, but implementation of this practice is embargoed until March 2027 [ 4 ]. Second, there is consideration of allowing MAiD to be implemented through advanced consent. This would make it possible for persons living with dementia to receive MAID after they have lost the capacity to consent to the procedure [ 5 ]. Third, there is consideration of extending MAiD to mature minors. A mature minor is defined as “a person under the age of majority…and who has the capacity to understand and appreciate the nature and consequences of a decision” ([ 6 ] p. 5). In summary, since the legalization of MAiD in 2016 the eligibility criteria and safeguards have evolved significantly with consequent implications for nurses and nursing care. Further, the number of Canadians who access MAiD shows steady increases since 2016 [ 7 ] and it is expected that these increases will continue in the foreseeable future.

Nurses have been integral to MAiD care in the Canadian context. While other countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands also permit euthanasia, Canada is the first country to allow Nurse Practitioners (Registered Nurses with additional preparation typically achieved at the graduate level) to act independently as assessors and providers of MAiD [ 1 ]. Although the role of Registered Nurses (RNs) in MAiD is not defined in federal legislation, it has been addressed at the provincial/territorial-level with variability in scope of practice by region [ 8 , 9 ]. For example, there are differences with respect to the obligation of the nurse to provide information to patients about MAiD, and to the degree that nurses are expected to ensure that patient eligibility criteria and safeguards are met prior to their participation [ 10 ]. Studies conducted in the Canadian context indicate that RNs perform essential roles in MAiD care coordination; client and family teaching and support; MAiD procedural quality; healthcare provider and public education; and bereavement care for family [ 9 , 11 ]. Nurse practitioners and RNs are integral to a robust MAiD care system in Canada and hence need to be well-prepared for their role [ 12 ].

Previous studies have found that end of life care, and MAiD specifically, raise complex moral and ethical issues for nurses [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. The knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of nurses are important across practice settings because nurses have consistent, ongoing, and direct contact with patients who experience chronic or life-limiting health conditions. Canadian studies exploring nurses’ moral and ethical decision-making in relation to MAiD reveal that although some nurses are clear in their support for, or opposition to, MAiD, others are unclear on what they believe to be good and right [ 14 ]. Empirical findings suggest that nurses go through a period of moral sense-making that is often informed by their family, peers, and initial experiences with MAID [ 17 , 18 ]. Canadian legislation and policy specifies that nurses are not required to participate in MAiD and may recuse themselves as conscientious objectors with appropriate steps to ensure ongoing and safe care of patients [ 1 , 19 ]. However, with so many nurses having to reflect on and make sense of their moral position, it is essential that they are given adequate time and preparation to make an informed and thoughtful decision before they participate in a MAID death [ 20 , 21 ].

It is well established that nursing students receive inconsistent exposure to end of life care issues [ 22 ] and little or no training related to MAiD [ 23 ]. Without such education and reflection time in pre-entry nursing preparation, nurses are at significant risk for moral harm. An important first step in providing this preparation is to be able to assess the knowledge, values, and beliefs of nursing students regarding MAID and end of life care. As demand for MAiD increases along with the complexities of MAiD, it is critical to understand the knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of engagement with MAiD among nursing students as a baseline upon which to build curriculum and as a means to track these variables over time.

Aim, design, and setting

The aim of this study was to develop a survey to measure nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, influences, and willingness to be involved in MAiD in the Canadian context. We sought to explore both their willingness to be involved in the registered nursing role and in the nurse practitioner role should they chose to prepare themselves to that level of education. The design was a mixed-method, modified e-Delphi method that entailed item generation, item refinement through an expert faculty panel [ 24 , 25 , 26 ], and initial item validation through a cognitive focus group interview with nursing students [ 27 ]. The settings were a University located in an urban area and a College located in a rural area in Western Canada.

Participants

A panel of 10 faculty from the two nursing education programs were recruited for Phase 2 of the e-Delphi. To be included, faculty were required to have a minimum of three years of experience in nurse education, be employed as nursing faculty, and self-identify as having experience with MAiD. A convenience sample of 5 fourth-year nursing students were recruited to participate in Phase 3. Students had to be in good standing in the nursing program and be willing to share their experiences of the survey in an online group interview format.

The modified e-Delphi was conducted in 3 phases: Phase 1 entailed item generation through literature and existing survey review. Phase 2 entailed item refinement through a faculty expert panel review with focus on content validity, prioritization, and revision of item wording [ 25 ]. Phase 3 entailed an assessment of face validity through focus group-based cognitive interview with nursing students.

Phase I. Item generation through literature review

The goal of phase 1 was to develop a bank of survey items that would represent the variables of interest and which could be provided to expert faculty in Phase 2. Initial survey items were generated through a literature review of similar surveys designed to assess knowledge and attitudes toward MAiD/euthanasia in healthcare providers; Canadian empirical studies on nurses’ roles and/or experiences with MAiD; and legislative and expert panel documents that outlined proposed changes to the legislative eligibility criteria and safeguards. The literature review was conducted in three online databases: CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Medline. Key words for the search included nurses , nursing students , medical students , NPs, MAiD , euthanasia , assisted death , and end-of-life care . Only articles written in English were reviewed. The legalization and legislation of MAiD is new in many countries; therefore, studies that were greater than twenty years old were excluded, no further exclusion criteria set for country.

Items from surveys designed to measure similar variables in other health care providers and geographic contexts were placed in a table and similar items were collated and revised into a single item. Then key variables were identified from the empirical literature on nurses and MAiD in Canada and checked against the items derived from the surveys to ensure that each of the key variables were represented. For example, conscientious objection has figured prominently in the Canadian literature, but there were few items that assessed knowledge of conscientious objection in other surveys and so items were added [ 15 , 21 , 28 , 29 ]. Finally, four case studies were added to the survey to address the anticipated changes to the Canadian legislation. The case studies were based upon the inclusion of mature minors, advanced consent, and mental disorder as the sole underlying medical condition. The intention was to assess nurses’ beliefs and comfort with these potential legislative changes.

Phase 2. Item refinement through expert panel review

The goal of phase 2 was to refine and prioritize the proposed survey items identified in phase 1 using a modified e-Delphi approach to achieve consensus among an expert panel [ 26 ]. Items from phase 1 were presented to an expert faculty panel using a Qualtrics (Provo, UT) online survey. Panel members were asked to review each item to determine if it should be: included, excluded or adapted for the survey. When adapted was selected faculty experts were asked to provide rationale and suggestions for adaptation through the use of an open text box. Items that reached a level of 75% consensus for either inclusion or adaptation were retained [ 25 , 26 ]. New items were categorized and added, and a revised survey was presented to the panel of experts in round 2. Panel members were again asked to review items, including new items, to determine if it should be: included, excluded, or adapted for the survey. Round 2 of the modified e-Delphi approach also included an item prioritization activity, where participants were then asked to rate the importance of each item, based on a 5-point Likert scale (low to high importance), which De Vaus [ 30 ] states is helpful for increasing the reliability of responses. Items that reached a 75% consensus on inclusion were then considered in relation to the importance it was given by the expert panel. Quantitative data were managed using SPSS (IBM Corp).

Phase 3. Face validity through cognitive interviews with nursing students

The goal of phase 3 was to obtain initial face validity of the proposed survey using a sample of nursing student informants. More specifically, student participants were asked to discuss how items were interpreted, to identify confusing wording or other problematic construction of items, and to provide feedback about the survey as a whole including readability and organization [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The focus group was held online and audio recorded. A semi-structured interview guide was developed for this study that focused on clarity, meaning, order and wording of questions; emotions evoked by the questions; and overall survey cohesion and length was used to obtain data (see Supplementary Material 2 for the interview guide). A prompt to “think aloud” was used to limit interviewer-imposed bias and encourage participants to describe their thoughts and response to a given item as they reviewed survey items [ 27 ]. Where needed, verbal probes such as “could you expand on that” were used to encourage participants to expand on their responses [ 27 ]. Student participants’ feedback was collated verbatim and presented to the research team where potential survey modifications were negotiated and finalized among team members. Conventional content analysis [ 34 ] of focus group data was conducted to identify key themes that emerged through discussion with students. Themes were derived from the data by grouping common responses and then using those common responses to modify survey items.

Ten nursing faculty participated in the expert panel. Eight of the 10 faculty self-identified as female. No faculty panel members reported conscientious objector status and ninety percent reported general agreement with MAiD with one respondent who indicated their view as “unsure.” Six of the 10 faculty experts had 16 years of experience or more working as a nurse educator.

Five nursing students participated in the cognitive interview focus group. The duration of the focus group was 2.5 h. All participants identified that they were born in Canada, self-identified as female (one preferred not to say) and reported having received some instruction about MAiD as part of their nursing curriculum. See Tables 1 and 2 for the demographic descriptors of the study sample. Study results will be reported in accordance with the study phases. See Fig. 1 for an overview of the results from each phase.

Fig. 1 Overview of survey development findings

Phase 1: survey item generation

Review of the literature identified that no existing survey was available for use with nursing students in the Canadian context. However, an analysis of themes across qualitative and quantitative studies of physicians, medical students, nurses, and nursing students provided sufficient data to develop a preliminary set of items suitable for adaptation to a population of nursing students.

Four major themes and factors that influence knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about MAiD were evident from the literature: (i) endogenous or individual factors such as age, gender, personally held values, religion, religiosity, and/or spirituality [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ], (ii) experience with death and dying in personal and/or professional life [ 35 , 40 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 45 ], (iii) training including curricular instruction about clinical role, scope of practice, or the law [ 23 , 36 , 39 ], and (iv) exogenous or social factors such as the influence of key leaders, colleagues, friends and/or family, professional and licensure organizations, support within professional settings, and/or engagement in MAiD in an interdisciplinary team context [ 9 , 35 , 46 ].

Studies of nursing students also suggest overlap across these categories. For example, value for patient autonomy [ 23 ] and the moral complexity of decision-making [ 37 ] are important factors that contribute to attitudes about MAiD and may stem from a blend of personally held values coupled with curricular content, professional training and norms, and clinical exposure. For example, students report that participation in end of life care allows for personal growth, shifts in perception, and opportunities to build therapeutic relationships with their clients [ 44 , 47 , 48 ].

Preliminary items generated from the literature resulted in 56 questions from 11 published sources (See Table 3 ). These items were constructed across four main categories: (i) socio-demographic questions; (ii) end of life care questions; (iii) knowledge about MAiD; or (iv) comfort and willingness to participate in MAiD. Knowledge questions were refined to reflect current MAiD legislation, policies, and regulatory frameworks. Falconer [ 39 ] and Freeman [ 45 ] studies were foundational sources for item selection. Additionally, four case studies were written to reflect the most recent anticipated changes to MAiD legislation and all used the same open-ended core questions to address respondents’ perspectives about the patient’s right to make the decision, comfort in assisting a physician or NP to administer MAiD in that scenario, and hypothesized comfort about serving as a primary provider if qualified as an NP in future. Response options for the survey were also constructed during this stage and included: open text, categorical, yes/no , and Likert scales.

Phase 2: faculty expert panel review

Of the 56 items presented to the faculty panel, 54 questions reached 75% consensus. However, based upon the qualitative responses 9 items were removed largely because they were felt to be repetitive. Items that generated the most controversy were related to measuring religion and spirituality in the Canadian context, defining end of life care when there is no agreed upon time frames (e.g., last days, months, or years), and predicting willingness to be involved in a future events – thus predicting their future selves. Phase 2, round 1 resulted in an initial set of 47 items which were then presented back to the faculty panel in round 2.

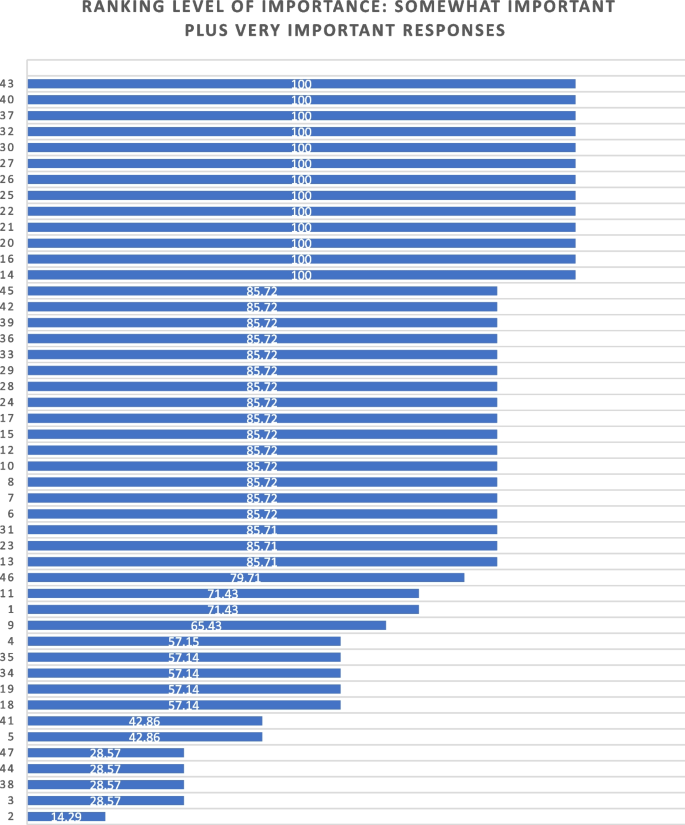

Of the 47 initial questions presented to the panel in round 2, 45 reached a level of consensus of 75% or greater, and 34 of these questions reached a level of 100% consensus [ 27 ] of which all participants chose to include without any adaptations) For each question, level of importance was determined based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very unimportant, 2 = somewhat unimportant, 3 = neutral, 4 = somewhat important, and 5 = very important). Figure 2 provides an overview of the level of importance assigned to each item.

Ranking level of importance for survey items

After round 2, a careful analysis of participant comments and level of importance was completed by the research team. While the main method of survey item development came from participants’ response to the first round of Delphi consensus ratings, level of importance was used to assist in the decision of whether to keep or modify questions that created controversy, or that rated lower in the include/exclude/adapt portion of the Delphi. Survey items that rated low in level of importance included questions about future roles, sex and gender, and religion/spirituality. After deliberation by the research committee, these questions were retained in the survey based upon the importance of these variables in the scientific literature.

Of the 47 questions remaining from Phase 2, round 2, four were revised. In addition, the two questions that did not meet the 75% cut off level for consensus were reviewed by the research team. The first question reviewed was What is your comfort level with providing a MAiD death in the future if you were a qualified NP ? Based on a review of participant comments, it was decided to retain this question for the cognitive interviews with students in the final phase of testing. The second question asked about impacts on respondents’ views of MAiD and was changed from one item with 4 subcategories into 4 separate items, resulting in a final total of 51 items for phase 3. The revised survey was then brought forward to the cognitive interviews with student participants in Phase 3. (see Supplementary Material 1 for a complete description of item modification during round 2).

Phase 3. Outcomes of cognitive interview focus group

Of the 51 items reviewed by student participants, 29 were identified as clear with little or no discussion. Participant comments for the remaining 22 questions were noted and verified against the audio recording. Following content analysis of the comments, four key themes emerged through the student discussion: unclear or ambiguous wording; difficult to answer questions; need for additional response options; and emotional response evoked by questions. An example of unclear or ambiguous wording was a request for clarity in the use of the word “sufficient” in the context of assessing an item that read “My nursing education has provided sufficient content about the nursing role in MAiD.” “Sufficient” was viewed as subjective and “laden with…complexity that distracted me from the question.” The group recommended rewording the item to read “My nursing education has provided enough content for me to care for a patient considering or requesting MAiD.”

An example of having difficulty answering questions related to limited knowledge related to terms used in the legislation such as such as safeguards , mature minor , eligibility criteria , and conscientious objection. Students were unclear about what these words meant relative to the legislation and indicated that this lack of clarity would hamper appropriate responses to the survey. To ensure that respondents are able to answer relevant questions, student participants recommended that the final survey include explanation of key terms such as mature minor and conscientious objection and an overview of current legislation.

Response options were also a point of discussion. Participants noted a lack of distinction between response options of unsure and unable to say . Additionally, scaling of attitudes was noted as important since perspectives about MAiD are dynamic and not dichotomous “agree or disagree” responses. Although the faculty expert panel recommended the integration of the demographic variables of religious and/or spiritual remain as a single item, the student group stated a preference to have religion and spirituality appear as separate items. The student focus group also took issue with separate items for the variables of sex and gender, specifically that non-binary respondents might feel othered or “outed” particularly when asked to identify their sex. These variables had been created based upon best practices in health research but students did not feel they were appropriate in this context [ 49 ]. Finally, students agreed with the faculty expert panel in terms of the complexity of projecting their future involvement as a Nurse Practitioner. One participant stated: “I certainly had to like, whoa, whoa, whoa. Now let me finish this degree first, please.” Another stated, “I'm still imagining myself, my future career as an RN.”

Finally, student participants acknowledged the array of emotions that some of the items produced for them. For example, one student described positive feelings when interacting with the survey. “Brought me a little bit of feeling of joy. Like it reminded me that this is the last piece of independence that people grab on to.” Another participant, described the freedom that the idea of an advance request gave her. “The advance request gives the most comfort for me, just with early onset Alzheimer’s and knowing what it can do.” But other participants described less positive feelings. For example, the mature minor case study yielded a comment: “This whole scenario just made my heart hurt with the idea of a child requesting that.”

Based on the data gathered from the cognitive interview focus group of nursing students, revisions were made to 11 closed-ended questions (see Table 4 ) and 3 items were excluded. In the four case studies, the open-ended question related to a respondents’ hypothesized actions in a future role as NP were removed. The final survey consists of 45 items including 4 case studies (see Supplementary Material 3 ).

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a survey that can be used to track the growth of knowledge about MAiD among nursing students over time, inform training programs about curricular needs, and evaluate attitudes and willingness to participate in MAiD at time-points during training or across nursing programs over time.

The faculty expert panel and student participants in the cognitive interview focus group identified a need to establish core knowledge of the terminology and legislative rules related to MAiD. For example, within the cognitive interview group of student participants, several acknowledged lack of clear understanding of specific terms such as “conscientious objector” and “safeguards.” Participants acknowledged discomfort with the uncertainty of not knowing and their inclination to look up these terms to assist with answering the questions. This survey can be administered to nursing or pre-nursing students at any phase of their training within a program or across training programs. However, in doing so it is important to acknowledge that their baseline knowledge of MAiD will vary. A response option of “not sure” is important and provides a means for respondents to convey uncertainty. If this survey is used to inform curricular needs, respondents should be given explicit instructions not to conduct online searches to inform their responses, but rather to provide an honest appraisal of their current knowledge and these instructions are included in the survey (see Supplementary Material 3 ).

Some provincial regulatory bodies have established core competencies for entry-level nurses that include MAiD. For example, the BC College of Nurses and Midwives (BCCNM) requires “knowledge about ethical, legal, and regulatory implications of medical assistance in dying (MAiD) when providing nursing care.” (10 p. 6) However, across Canada curricular content and coverage related to end of life care and MAiD is variable [ 23 ]. Given the dynamic nature of the legislation that includes portions of the law that are embargoed until 2024, it is important to ensure that respondents are guided by current and accurate information. As the law changes, nursing curricula, and public attitudes continue to evolve, inclusion of core knowledge and content is essential and relevant for investigators to be able to interpret the portions of the survey focused on attitudes and beliefs about MAiD. Content knowledge portions of the survey may need to be modified over time as legislation and training change and to meet the specific purposes of the investigator.

Given the sensitive nature of the topic, it is strongly recommended that surveys be conducted anonymously and that students be provided with an opportunity to discuss their responses to the survey. A majority of feedback from both the expert panel of faculty and from student participants related to the wording and inclusion of demographic variables, in particular religion, religiosity, gender identity, and sex assigned at birth. These and other demographic variables have the potential to be highly identifying in small samples. In any instance in which the survey could be expected to yield demographic group sizes less than 5, users should eliminate the demographic variables from the survey. For example, the profession of nursing is highly dominated by females with over 90% of nurses who identify as female [ 50 ]. Thus, a survey within a single class of students or even across classes in a single institution is likely to yield a small number of male respondents and/or respondents who report a difference between sex assigned at birth and gender identity. When variables that serve to identify respondents are included, respondents are less likely to complete or submit the survey, to obscure their responses so as not to be identifiable, or to be influenced by social desirability bias in their responses rather than to convey their attitudes accurately [ 51 ]. Further, small samples do not allow for conclusive analyses or interpretation of apparent group differences. Although these variables are often included in surveys, such demographics should be included only when anonymity can be sustained. In small and/or known samples, highly identifying variables should be omitted.

There are several limitations associated with the development of this survey. The expert panel was comprised of faculty who teach nursing students and are knowledgeable about MAiD and curricular content, however none identified as a conscientious objector to MAiD. Ideally, our expert panel would have included one or more conscientious objectors to MAiD to provide a broader perspective. Review by practitioners who participate in MAiD, those who are neutral or undecided, and practitioners who are conscientious objectors would ensure broad applicability of the survey. This study included one student cognitive interview focus group with 5 self-selected participants. All student participants had held discussions about end of life care with at least one patient, 4 of 5 participants had worked with a patient who requested MAiD, and one had been present for a MAiD death. It is not clear that these participants are representative of nursing students demographically or by experience with end of life care. It is possible that the students who elected to participate hold perspectives and reflections on patient care and MAiD that differ from students with little or no exposure to end of life care and/or MAiD. However, previous studies find that most nursing students have been involved with end of life care including meaningful discussions about patients’ preferences and care needs during their education [ 40 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 52 ]. Data collection with additional student focus groups with students early in their training and drawn from other training contexts would contribute to further validation of survey items.

Future studies should incorporate pilot testing with small sample of nursing students followed by a larger cross-program sample to allow evaluation of the psychometric properties of specific items and further refinement of the survey tool. Consistent with literature about the importance of leadership in the context of MAiD [ 12 , 53 , 54 ], a study of faculty knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes toward MAiD would provide context for understanding student perspectives within and across programs. Additional research is also needed to understand the timing and content coverage of MAiD across Canadian nurse training programs’ curricula.

The implementation of MAiD is complex and requires understanding of the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. Within the field of nursing this includes clinical providers, educators, and students who will deliver clinical care. A survey to assess nursing students’ attitudes toward and willingness to participate in MAiD in the Canadian context is timely, due to the legislation enacted in 2016 and subsequent modifications to the law in 2021 with portions of the law to be enacted in 2027. Further development of this survey could be undertaken to allow for use in settings with practicing nurses or to allow longitudinal follow up with students as they enter practice. As the Canadian landscape changes, ongoing assessment of the perspectives and needs of health professionals and students in the health professions is needed to inform policy makers, leaders in practice, curricular needs, and to monitor changes in attitudes and practice patterns over time.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to small sample sizes, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

British Columbia College of Nurses and Midwives

Medical assistance in dying

Nurse practitioner

Registered nurse

University of British Columbia Okanagan

Nicol J, Tiedemann M. Legislative Summary: Bill C-14: An Act to amend the Criminal Code and to make related amendments to other Acts (medical assistance in dying). Available from: https://lop.parl.ca/staticfiles/PublicWebsite/Home/ResearchPublications/LegislativeSummaries/PDF/42-1/c14-e.pdf .

Downie J, Scallion K. Foreseeably unclear. The meaning of the “reasonably foreseeable” criterion for access to medical assistance in dying in Canada. Dalhousie Law J. 2018;41(1):23–57.

Nicol J, Tiedeman M. Legislative summary of Bill C-7: an act to amend the criminal code (medical assistance in dying). Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2021.

Google Scholar

Council of Canadian Academies. The state of knowledge on medical assistance in dying where a mental disorder is the sole underlying medical condition. Ottawa; 2018. Available from: https://cca-reports.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/The-State-of-Knowledge-on-Medical-Assistance-in-Dying-Where-a-Mental-Disorder-is-the-Sole-Underlying-Medical-Condition.pdf .

Council of Canadian Academies. The state of knowledge on advance requests for medical assistance in dying. Ottawa; 2018. Available from: https://cca-reports.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The-State-of-Knowledge-on-Advance-Requests-for-Medical-Assistance-in-Dying.pdf .

Council of Canadian Academies. The state of knowledge on medical assistance in dying for mature minors. Ottawa; 2018. Available from: https://cca-reports.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/The-State-of-Knowledge-on-Medical-Assistance-in-Dying-for-Mature-Minors.pdf .

Health Canada. Third annual report on medical assistance in dying in Canada 2021. Ottawa; 2022. [cited 2023 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying/annual-report-2021.html .

Banner D, Schiller CJ, Freeman S. Medical assistance in dying: a political issue for nurses and nursing in Canada. Nurs Philos. 2019;20(4): e12281.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pesut B, Thorne S, Stager ML, Schiller CJ, Penney C, Hoffman C, et al. Medical assistance in dying: a review of Canadian nursing regulatory documents. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2019;20(3):113–30.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

College of Registered Nurses of British Columbia. Scope of practice for registered nurses [Internet]. Vancouver; 2018. Available from: https://www.bccnm.ca/Documents/standards_practice/rn/RN_ScopeofPractice.pdf .

Pesut B, Thorne S, Schiller C, Greig M, Roussel J, Tishelman C. Constructing good nursing practice for medical assistance in dying in Canada: an interpretive descriptive study. Global Qual Nurs Res. 2020;7:2333393620938686. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393620938686 .

Article Google Scholar

Pesut B, Thorne S, Schiller CJ, Greig M, Roussel J. The rocks and hard places of MAiD: a qualitative study of nursing practice in the context of legislated assisted death. BMC Nurs. 2020;19:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-0404-5 .

Pesut B, Greig M, Thorne S, Burgess M, Storch JL, Tishelman C, et al. Nursing and euthanasia: a narrative review of the nursing ethics literature. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(1):152–67.

Pesut B, Thorne S, Storch J, Chambaere K, Greig M, Burgess M. Riding an elephant: a qualitative study of nurses’ moral journeys in the context of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD). Journal Clin Nurs. 2020;29(19–20):3870–81.

Lamb C, Babenko-Mould Y, Evans M, Wong CA, Kirkwood KW. Conscientious objection and nurses: results of an interpretive phenomenological study. Nurs Ethics. 2018;26(5):1337–49.

Wright DK, Chan LS, Fishman JR, Macdonald ME. “Reflection and soul searching:” Negotiating nursing identity at the fault lines of palliative care and medical assistance in dying. Social Sci & Med. 2021;289: 114366.

Beuthin R, Bruce A, Scaia M. Medical assistance in dying (MAiD): Canadian nurses’ experiences. Nurs Forum. 2018;54(4):511–20.

Bruce A, Beuthin R. Medically assisted dying in Canada: "Beautiful Death" is transforming nurses' experiences of suffering. The Canadian J Nurs Res | Revue Canadienne de Recherche en Sci Infirmieres. 2020;52(4):268–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0844562119856234 .

Canadian Nurses Association. Code of ethics for registered nurses. Ottawa; 2017. Available from: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/nursing/regulated-nursing-in-canada/nursing-ethics .

Canadian Nurses Association. National nursing framework on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada. Ottawa: 2017. Available from: https://www.virtualhospice.ca/Assets/cna-national-nursing-framework-on-maidEng_20170216155827.pdf .

Pesut B, Thorne S, Greig M. Shades of gray: conscientious objection in medical assistance in dying. Nursing Inq. 2020;27(1): e12308.

Durojaiye A, Ryan R, Doody O. Student nurse education and preparation for palliative care: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286678 .

McMechan C, Bruce A, Beuthin R. Canadian nursing students’ experiences with medical assistance in dying | Les expériences d’étudiantes en sciences infirmières au regard de l’aide médicale à mourir. Qual Adv Nurs Educ - Avancées en Formation Infirmière. 2019;5(1). https://doi.org/10.17483/2368-6669.1179 .

Adler M, Ziglio E. Gazing into the oracle. The Delphi method and its application to social policy and public health. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1996

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):205–12.

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. 1st ed. City: Wiley; 2011.

Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 2005. ISBN: 9780761928041

Lamb C, Evans M, Babenko-Mould Y, Wong CA, Kirkwood EW. Conscience, conscientious objection, and nursing: a concept analysis. Nurs Ethics. 2017;26(1):37–49.

Lamb C, Evans M, Babenko-Mould Y, Wong CA, Kirkwood K. Nurses’ use of conscientious objection and the implications of conscience. J Adv Nurs. 2018;75(3):594–602.

de Vaus D. Surveys in social research. 6th ed. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2014.

Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, Melgar-Quiñonez HR, Young SL. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149 .

Puchta C, Potter J. Focus group practice. 1st ed. London: Sage; 2004.

Book Google Scholar

Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Adesina O, DeBellis A, Zannettino L. Third-year Australian nursing students’ attitudes, experiences, knowledge, and education concerning end-of-life care. Int J of Palliative Nurs. 2014;20(8):395–401.

Bator EX, Philpott B, Costa AP. This moral coil: a cross-sectional survey of Canadian medical student attitudes toward medical assistance in dying. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):58.

Beuthin R, Bruce A, Scaia M. Medical assistance in dying (MAiD): Canadian nurses’ experiences. Nurs Forum. 2018;53(4):511–20.

Brown J, Goodridge D, Thorpe L, Crizzle A. What is right for me, is not necessarily right for you: the endogenous factors influencing nonparticipation in medical assistance in dying. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(10):1786–1800.

Falconer J, Couture F, Demir KK, Lang M, Shefman Z, Woo M. Perceptions and intentions toward medical assistance in dying among Canadian medical students. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):22.

Green G, Reicher S, Herman M, Raspaolo A, Spero T, Blau A. Attitudes toward euthanasia—dual view: Nursing students and nurses. Death Stud. 2022;46(1):124–31.

Hosseinzadeh K, Rafiei H. Nursing student attitudes toward euthanasia: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(2):496–503.

Ozcelik H, Tekir O, Samancioglu S, Fadiloglu C, Ozkara E. Nursing students’ approaches toward euthanasia. Omega (Westport). 2014;69(1):93–103.

Canning SE, Drew C. Canadian nursing students’ understanding, and comfort levels related to medical assistance in dying. Qual Adv Nurs Educ - Avancées en Formation Infirmière. 2022;8(2). https://doi.org/10.17483/2368-6669.1326 .

Edo-Gual M, Tomás-Sábado J, Bardallo-Porras D, Monforte-Royo C. The impact of death and dying on nursing students: an explanatory model. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(23–24):3501–12.