- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

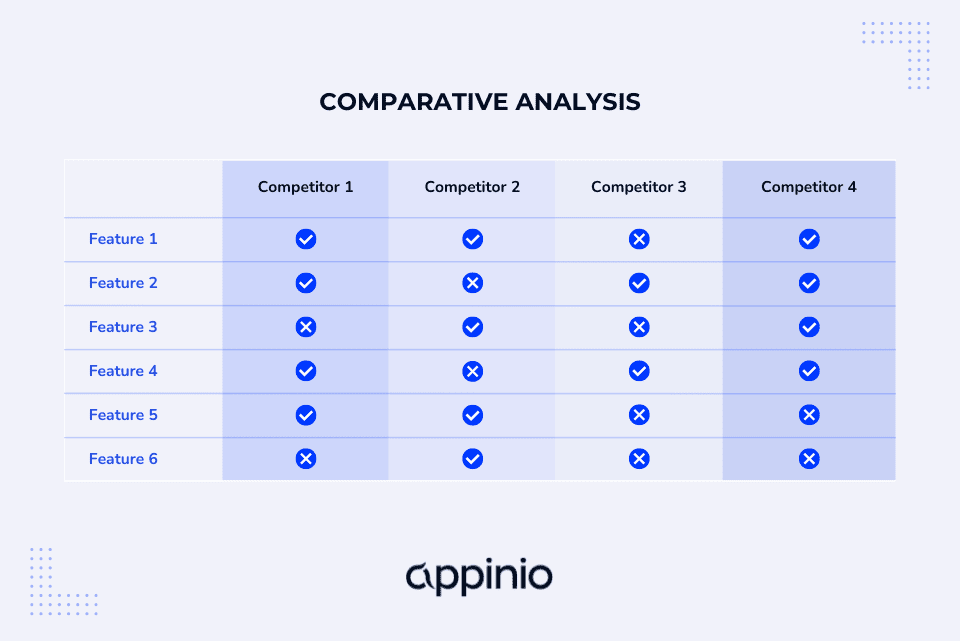

- Comparative Analysis

What It Is and Why It's Useful

Comparative analysis asks writers to make an argument about the relationship between two or more texts. Beyond that, there's a lot of variation, but three overarching kinds of comparative analysis stand out:

- Coordinate (A ↔ B): In this kind of analysis, two (or more) texts are being read against each other in terms of a shared element, e.g., a memoir and a novel, both by Jesmyn Ward; two sets of data for the same experiment; a few op-ed responses to the same event; two YA books written in Chicago in the 2000s; a film adaption of a play; etc.

- Subordinate (A → B) or (B → A ): Using a theoretical text (as a "lens") to explain a case study or work of art (e.g., how Anthony Jack's The Privileged Poor can help explain divergent experiences among students at elite four-year private colleges who are coming from similar socio-economic backgrounds) or using a work of art or case study (i.e., as a "test" of) a theory's usefulness or limitations (e.g., using coverage of recent incidents of gun violence or legislation un the U.S. to confirm or question the currency of Carol Anderson's The Second ).

- Hybrid [A → (B ↔ C)] or [(B ↔ C) → A] , i.e., using coordinate and subordinate analysis together. For example, using Jack to compare or contrast the experiences of students at elite four-year institutions with students at state universities and/or community colleges; or looking at gun culture in other countries and/or other timeframes to contextualize or generalize Anderson's main points about the role of the Second Amendment in U.S. history.

"In the wild," these three kinds of comparative analysis represent increasingly complex—and scholarly—modes of comparison. Students can of course compare two poems in terms of imagery or two data sets in terms of methods, but in each case the analysis will eventually be richer if the students have had a chance to encounter other people's ideas about how imagery or methods work. At that point, we're getting into a hybrid kind of reading (or even into research essays), especially if we start introducing different approaches to imagery or methods that are themselves being compared along with a couple (or few) poems or data sets.

Why It's Useful

In the context of a particular course, each kind of comparative analysis has its place and can be a useful step up from single-source analysis. Intellectually, comparative analysis helps overcome the "n of 1" problem that can face single-source analysis. That is, a writer drawing broad conclusions about the influence of the Iranian New Wave based on one film is relying entirely—and almost certainly too much—on that film to support those findings. In the context of even just one more film, though, the analysis is suddenly more likely to arrive at one of the best features of any comparative approach: both films will be more richly experienced than they would have been in isolation, and the themes or questions in terms of which they're being explored (here the general question of the influence of the Iranian New Wave) will arrive at conclusions that are less at-risk of oversimplification.

For scholars working in comparative fields or through comparative approaches, these features of comparative analysis animate their work. To borrow from a stock example in Western epistemology, our concept of "green" isn't based on a single encounter with something we intuit or are told is "green." Not at all. Our concept of "green" is derived from a complex set of experiences of what others say is green or what's labeled green or what seems to be something that's neither blue nor yellow but kind of both, etc. Comparative analysis essays offer us the chance to engage with that process—even if only enough to help us see where a more in-depth exploration with a higher and/or more diverse "n" might lead—and in that sense, from the standpoint of the subject matter students are exploring through writing as well the complexity of the genre of writing they're using to explore it—comparative analysis forms a bridge of sorts between single-source analysis and research essays.

Typical learning objectives for single-sources essays: formulate analytical questions and an arguable thesis, establish stakes of an argument, summarize sources accurately, choose evidence effectively, analyze evidence effectively, define key terms, organize argument logically, acknowledge and respond to counterargument, cite sources properly, and present ideas in clear prose.

Common types of comparative analysis essays and related types: two works in the same genre, two works from the same period (but in different places or in different cultures), a work adapted into a different genre or medium, two theories treating the same topic; a theory and a case study or other object, etc.

How to Teach It: Framing + Practice

Framing multi-source writing assignments (comparative analysis, research essays, multi-modal projects) is likely to overlap a great deal with "Why It's Useful" (see above), because the range of reasons why we might use these kinds of writing in academic or non-academic settings is itself the reason why they so often appear later in courses. In many courses, they're the best vehicles for exploring the complex questions that arise once we've been introduced to the course's main themes, core content, leading protagonists, and central debates.

For comparative analysis in particular, it's helpful to frame assignment's process and how it will help students successfully navigate the challenges and pitfalls presented by the genre. Ideally, this will mean students have time to identify what each text seems to be doing, take note of apparent points of connection between different texts, and start to imagine how those points of connection (or the absence thereof)

- complicates or upends their own expectations or assumptions about the texts

- complicates or refutes the expectations or assumptions about the texts presented by a scholar

- confirms and/or nuances expectations and assumptions they themselves hold or scholars have presented

- presents entirely unforeseen ways of understanding the texts

—and all with implications for the texts themselves or for the axes along which the comparative analysis took place. If students know that this is where their ideas will be heading, they'll be ready to develop those ideas and engage with the challenges that comparative analysis presents in terms of structure (See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more on these elements of framing).

Like single-source analyses, comparative essays have several moving parts, and giving students practice here means adapting the sample sequence laid out at the " Formative Writing Assignments " page. Three areas that have already been mentioned above are worth noting:

- Gathering evidence : Depending on what your assignment is asking students to compare (or in terms of what), students will benefit greatly from structured opportunities to create inventories or data sets of the motifs, examples, trajectories, etc., shared (or not shared) by the texts they'll be comparing. See the sample exercises below for a basic example of what this might look like.

- Why it Matters: Moving beyond "x is like y but also different" or even "x is more like y than we might think at first" is what moves an essay from being "compare/contrast" to being a comparative analysis . It's also a move that can be hard to make and that will often evolve over the course of an assignment. A great way to get feedback from students about where they're at on this front? Ask them to start considering early on why their argument "matters" to different kinds of imagined audiences (while they're just gathering evidence) and again as they develop their thesis and again as they're drafting their essays. ( Cover letters , for example, are a great place to ask writers to imagine how a reader might be affected by reading an their argument.)

- Structure: Having two texts on stage at the same time can suddenly feel a lot more complicated for any writer who's used to having just one at a time. Giving students a sense of what the most common patterns (AAA / BBB, ABABAB, etc.) are likely to be can help them imagine, even if provisionally, how their argument might unfold over a series of pages. See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more information on this front.

Sample Exercises and Links to Other Resources

- Common Pitfalls

- Advice on Timing

- Try to keep students from thinking of a proposed thesis as a commitment. Instead, help them see it as more of a hypothesis that has emerged out of readings and discussion and analytical questions and that they'll now test through an experiment, namely, writing their essay. When students see writing as part of the process of inquiry—rather than just the result—and when that process is committed to acknowledging and adapting itself to evidence, it makes writing assignments more scientific, more ethical, and more authentic.

- Have students create an inventory of touch points between the two texts early in the process.

- Ask students to make the case—early on and at points throughout the process—for the significance of the claim they're making about the relationship between the texts they're comparing.

- For coordinate kinds of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is tied to thesis and evidence. Basically, it's a thesis that tells the reader that there are "similarities and differences" between two texts, without telling the reader why it matters that these two texts have or don't have these particular features in common. This kind of thesis is stuck at the level of description or positivism, and it's not uncommon when a writer is grappling with the complexity that can in fact accompany the "taking inventory" stage of comparative analysis. The solution is to make the "taking inventory" stage part of the process of the assignment. When this stage comes before students have formulated a thesis, that formulation is then able to emerge out of a comparative data set, rather than the data set emerging in terms of their thesis (which can lead to confirmation bias, or frequency illusion, or—just for the sake of streamlining the process of gathering evidence—cherry picking).

- For subordinate kinds of comparative analysis , a common pitfall is tied to how much weight is given to each source. Having students apply a theory (in a "lens" essay) or weigh the pros and cons of a theory against case studies (in a "test a theory") essay can be a great way to help them explore the assumptions, implications, and real-world usefulness of theoretical approaches. The pitfall of these approaches is that they can quickly lead to the same biases we saw here above. Making sure that students know they should engage with counterevidence and counterargument, and that "lens" / "test a theory" approaches often balance each other out in any real-world application of theory is a good way to get out in front of this pitfall.

- For any kind of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is structure. Every comparative analysis asks writers to move back and forth between texts, and that can pose a number of challenges, including: what pattern the back and forth should follow and how to use transitions and other signposting to make sure readers can follow the overarching argument as the back and forth is taking place. Here's some advice from an experienced writing instructor to students about how to think about these considerations:

a quick note on STRUCTURE

Most of us have encountered the question of whether to adopt what we might term the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure or the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure. Do we make all of our points about text A before moving on to text B? Or do we go back and forth between A and B as the essay proceeds? As always, the answers to our questions about structure depend on our goals in the essay as a whole. In a “similarities in spite of differences” essay, for instance, readers will need to encounter the differences between A and B before we offer them the similarities (A d →B d →A s →B s ). If, rather than subordinating differences to similarities you are subordinating text A to text B (using A as a point of comparison that reveals B’s originality, say), you may be well served by the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure.

Ultimately, you need to ask yourself how many “A→B” moves you have in you. Is each one identical? If so, you may wish to make the transition from A to B only once (“A→A→A→B→B→B”), because if each “A→B” move is identical, the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure will appear to involve nothing more than directionless oscillation and repetition. If each is increasingly complex, however—if each AB pair yields a new and progressively more complex idea about your subject—you may be well served by the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure, because in this case it will be visible to readers as a progressively developing argument.

As we discussed in "Advice on Timing" at the page on single-source analysis, that timeline itself roughly follows the "Sample Sequence of Formative Assignments for a 'Typical' Essay" outlined under " Formative Writing Assignments, " and it spans about 5–6 steps or 2–4 weeks.

Comparative analysis assignments have a lot of the same DNA as single-source essays, but they potentially bring more reading into play and ask students to engage in more complicated acts of analysis and synthesis during the drafting stages. With that in mind, closer to 4 weeks is probably a good baseline for many single-source analysis assignments. For sections that meet once per week, the timeline will either probably need to expand—ideally—a little past the 4-week side of things, or some of the steps will need to be combined or done asynchronously.

What It Can Build Up To

Comparative analyses can build up to other kinds of writing in a number of ways. For example:

- They can build toward other kinds of comparative analysis, e.g., student can be asked to choose an additional source to complicate their conclusions from a previous analysis, or they can be asked to revisit an analysis using a different axis of comparison, such as race instead of class. (These approaches are akin to moving from a coordinate or subordinate analysis to more of a hybrid approach.)

- They can scaffold up to research essays, which in many instances are an extension of a "hybrid comparative analysis."

- Like single-source analysis, in a course where students will take a "deep dive" into a source or topic for their capstone, they can allow students to "try on" a theoretical approach or genre or time period to see if it's indeed something they want to research more fully.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Formative Writing Assignments

- Single-Source Analysis

- Research Essays

- Multi-Modal or Creative Projects

- Giving Feedback to Students

Assignment Decoder

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Comparative Analysis: What It Is & How to Conduct It

When a business wants to start a marketing campaign or grow, a comparative analysis can give them information that helps them make crucial decisions. This analysis gathers different data sets to compare different options so a business can make good decisions for its customers and itself. If you or your business want to make good decisions, learning about comparative analyses could be helpful.

In this article, we’ll explain the comparative analysis and its importance. We’ll also learn how to do a good in-depth analysis .

What is comparative analysis?

Comparative analysis is a way to look at two or more similar things to see how they are different and what they have in common.

It is used in many ways and fields to help people understand the similarities and differences between products better. It can help businesses make good decisions about key issues.

One meaningful way it’s used is when applied to scientific data. Scientific data is information that has been gathered through scientific research and will be used for a certain purpose.

When it is used on scientific data, it determines how consistent and reliable the data is. It also helps scientists make sure their data is accurate and valid.

Importance of comparative analysis

Comparative analyses are important if you want to understand a problem better or find answers to important questions. Here are the main goals businesses want to reach through comparative analysis.

- It is a part of the diagnostic phase of business analytics. It can answer many of the most important questions a company may have and help you figure out how to fix problems at the company’s core to improve performance and even make more money.

- It encourages a deep understanding of the opportunities that apply to specific processes, departments, or business units. This analysis also ensures that we’re addressing the real reasons for performance gaps.

- It is used a lot because it helps people understand the challenges an organization has faced in the past and the ones it faces now. This method gives objective, fact-based information about performance and ways to improve it.

How to successfully conduct it

Consider using the advice below to carry out a successful comparative analysis:

Conduct research

Before doing an analysis, it’s important to do a lot of research . Research not only gives you evidence to back up your conclusions, but it might also show you something you hadn’t thought of before.

Research could also tell you how your competitors might handle a problem.

Make a list of what’s different and what’s the same.

When comparing two things in a comparative analysis, you need to make a detailed list of the similarities and differences.

Try to figure out how a change to one thing might affect another. Such as how increasing the number of vacation days affects sales, production, or costs.

A comparative analysis can also help you find outside causes, such as economic conditions or environmental analysis problems.

Describe both sides

Comparative analysis may try to show that one argument or idea is better, but the analysis must cover both sides equally. The analysis shows both sides of the main arguments and claims.

For example, to compare the benefits and drawbacks of starting a recycling program, one might examine both the positive effects, such as corporate responsibility and the potential negative effects, such as high implementation costs, to make wise, practical decisions or come up with alternate solutions.

Include variables

A thorough comparison unit of analysis is usually more than just a list of pros and cons because it usually considers factors that affect both sides.

Variables can be both things that can’t be changed, like how the weather in the summer affects shipping speeds, and things that can be changed, like when to work with a local shipper.

Do analyses regularly

Comparative analyses are important for any business practice. Consider the different areas and factors that a comparative analysis looks at:

- Competitors

- How well do stocks

- Financial position

- Profitability

- Dividends and revenue

- Development and research

Because a comparative analysis can help more than one department in a company, doing them often can help you keep up with market changes and stay relevant.

We’ve talked about how good a comparative analysis is for your business. But things always have two sides. It is a good workaround, but still do your own user interviews or user tests if you can.

We hope you have fun doing comparative analyses! Comparative analysis is always a method you like to use, and the point of learning from competitors is to add your own ideas. In this way, you are not just following but also learning and making.

QuestionPro can help you with your analysis process, create and design a survey to meet your goals, and analyze data for your business’s comparative analysis.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software and a library of insights for all kinds of l ong-term research . If you want to book a demo or learn more about our platform, just click here.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Top 12 Interactive Presentation Software to Engage Your User

May 29, 2024

Trend Report: Guide for Market Dynamics & Strategic Analysis

Cannabis Industry Business Intelligence: Impact on Research

May 28, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

How to Do Comparative Analysis in Research ( Examples )

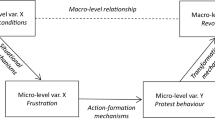

Comparative analysis is a method that is widely used in social science . It is a method of comparing two or more items with an idea of uncovering and discovering new ideas about them. It often compares and contrasts social structures and processes around the world to grasp general patterns. Comparative analysis tries to understand the study and explain every element of data that comparing.

We often compare and contrast in our daily life. So it is usual to compare and contrast the culture and human society. We often heard that ‘our culture is quite good than theirs’ or ‘their lifestyle is better than us’. In social science, the social scientist compares primitive, barbarian, civilized, and modern societies. They use this to understand and discover the evolutionary changes that happen to society and its people. It is not only used to understand the evolutionary processes but also to identify the differences, changes, and connections between societies.

Most social scientists are involved in comparative analysis. Macfarlane has thought that “On account of history, the examinations are typically on schedule, in that of other sociologies, transcendently in space. The historian always takes their society and compares it with the past society, and analyzes how far they differ from each other.

The comparative method of social research is a product of 19 th -century sociology and social anthropology. Sociologists like Emile Durkheim, Herbert Spencer Max Weber used comparative analysis in their works. For example, Max Weber compares the protestant of Europe with Catholics and also compared it with other religions like Islam, Hinduism, and Confucianism.

To do a systematic comparison we need to follow different elements of the method.

1. Methods of comparison The comparison method

In social science, we can do comparisons in different ways. It is merely different based on the topic, the field of study. Like Emile Durkheim compare societies as organic solidarity and mechanical solidarity. The famous sociologist Emile Durkheim provides us with three different approaches to the comparative method. Which are;

- The first approach is to identify and select one particular society in a fixed period. And by doing that, we can identify and determine the relationship, connections and differences exist in that particular society alone. We can find their religious practices, traditions, law, norms etc.

- The second approach is to consider and draw various societies which have common or similar characteristics that may vary in some ways. It may be we can select societies at a specific period, or we can select societies in the different periods which have common characteristics but vary in some ways. For example, we can take European and American societies (which are universally similar characteristics) in the 20 th century. And we can compare and contrast their society in terms of law, custom, tradition, etc.

- The third approach he envisaged is to take different societies of different times that may share some similar characteristics or maybe show revolutionary changes. For example, we can compare modern and primitive societies which show us revolutionary social changes.

2 . The unit of comparison

We cannot compare every aspect of society. As we know there are so many things that we cannot compare. The very success of the compare method is the unit or the element that we select to compare. We are only able to compare things that have some attributes in common. For example, we can compare the existing family system in America with the existing family system in Europe. But we are not able to compare the food habits in china with the divorce rate in America. It is not possible. So, the next thing you to remember is to consider the unit of comparison. You have to select it with utmost care.

3. The motive of comparison

As another method of study, a comparative analysis is one among them for the social scientist. The researcher or the person who does the comparative method must know for what grounds they taking the comparative method. They have to consider the strength, limitations, weaknesses, etc. He must have to know how to do the analysis.

Steps of the comparative method

1. Setting up of a unit of comparison

As mentioned earlier, the first step is to consider and determine the unit of comparison for your study. You must consider all the dimensions of your unit. This is where you put the two things you need to compare and to properly analyze and compare it. It is not an easy step, we have to systematically and scientifically do this with proper methods and techniques. You have to build your objectives, variables and make some assumptions or ask yourself about what you need to study or make a hypothesis for your analysis.

The best casings of reference are built from explicit sources instead of your musings or perceptions. To do that you can select some attributes in the society like marriage, law, customs, norms, etc. by doing this you can easily compare and contrast the two societies that you selected for your study. You can set some questions like, is the marriage practices of Catholics are different from Protestants? Did men and women get an equal voice in their mate choice? You can set as many questions that you wanted. Because that will explore the truth about that particular topic. A comparative analysis must have these attributes to study. A social scientist who wishes to compare must develop those research questions that pop up in your mind. A study without those is not going to be a fruitful one.

2. Grounds of comparison

The grounds of comparison should be understandable for the reader. You must acknowledge why you selected these units for your comparison. For example, it is quite natural that a person who asks why you choose this what about another one? What is the reason behind choosing this particular society? If a social scientist chooses primitive Asian society and primitive Australian society for comparison, he must acknowledge the grounds of comparison to the readers. The comparison of your work must be self-explanatory without any complications.

If you choose two particular societies for your comparative analysis you must convey to the reader what are you intended to choose this and the reason for choosing that society in your analysis.

3 . Report or thesis

The main element of the comparative analysis is the thesis or the report. The report is the most important one that it must contain all your frame of reference. It must include all your research questions, objectives of your topic, the characteristics of your two units of comparison, variables in your study, and last but not least the finding and conclusion must be written down. The findings must be self-explanatory because the reader must understand to what extent did they connect and what are their differences. For example, in Emile Durkheim’s Theory of Division of Labour, he classified organic solidarity and Mechanical solidarity . In which he means primitive society as Mechanical solidarity and modern society as Organic Solidarity. Like that you have to mention what are your findings in the thesis.

4. Relationship and linking one to another

Your paper must link each point in the argument. Without that the reader does not understand the logical and rational advance in your analysis. In a comparative analysis, you need to compare the ‘x’ and ‘y’ in your paper. (x and y mean the two-unit or things in your comparison). To do that you can use likewise, similarly, on the contrary, etc. For example, if we do a comparison between primitive society and modern society we can say that; ‘in the primitive society the division of labour is based on gender and age on the contrary (or the other hand), in modern society, the division of labour is based on skill and knowledge of a person.

Demerits of comparison

Comparative analysis is not always successful. It has some limitations. The broad utilization of comparative analysis can undoubtedly cause the feeling that this technique is a solidly settled, smooth, and unproblematic method of investigation, which because of its undeniable intelligent status can produce dependable information once some specialized preconditions are met acceptably.

Perhaps the most fundamental issue here respects the independence of the unit picked for comparison. As different types of substances are gotten to be analyzed, there is frequently a fundamental and implicit supposition about their independence and a quiet propensity to disregard the mutual influences and common impacts among the units.

One more basic issue with broad ramifications concerns the decision of the units being analyzed. The primary concern is that a long way from being a guiltless as well as basic assignment, the decision of comparison units is a basic and precarious issue. The issue with this sort of comparison is that in such investigations the depictions of the cases picked for examination with the principle one will in general turn out to be unreasonably streamlined, shallow, and stylised with contorted contentions and ends as entailment.

However, a comparative analysis is as yet a strategy with exceptional benefits, essentially due to its capacity to cause us to perceive the restriction of our psyche and check against the weaknesses and hurtful results of localism and provincialism. We may anyway have something to gain from history specialists’ faltering in utilizing comparison and from their regard for the uniqueness of settings and accounts of people groups. All of the above, by doing the comparison we discover the truths the underlying and undiscovered connection, differences that exist in society.

Also Read: How to write a Sociology Analysis? Explained with Examples

Sociology Group

We believe in sharing knowledge with everyone and making a positive change in society through our work and contributions. If you are interested in joining us, please check our 'About' page for more information

What is Comparative Analysis and How to Conduct It? (+ Examples)

Appinio Research · 30.10.2023 · 36min read

Have you ever faced a complex decision, wondering how to make the best choice among multiple options? In a world filled with data and possibilities, the art of comparative analysis holds the key to unlocking clarity amidst the chaos.

In this guide, we'll demystify the power of comparative analysis, revealing its practical applications, methodologies, and best practices. Whether you're a business leader, researcher, or simply someone seeking to make more informed decisions, join us as we explore the intricacies of comparative analysis and equip you with the tools to chart your course with confidence.

What is Comparative Analysis?

Comparative analysis is a systematic approach used to evaluate and compare two or more entities, variables, or options to identify similarities, differences, and patterns. It involves assessing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with each entity or option to make informed decisions.

The primary purpose of comparative analysis is to provide a structured framework for decision-making by:

- Facilitating Informed Choices: Comparative analysis equips decision-makers with data-driven insights, enabling them to make well-informed choices among multiple options.

- Identifying Trends and Patterns: It helps identify recurring trends, patterns, and relationships among entities or variables, shedding light on underlying factors influencing outcomes.

- Supporting Problem Solving: Comparative analysis aids in solving complex problems by systematically breaking them down into manageable components and evaluating potential solutions.

- Enhancing Transparency: By comparing multiple options, comparative analysis promotes transparency in decision-making processes, allowing stakeholders to understand the rationale behind choices.

- Mitigating Risks : It helps assess the risks associated with each option, allowing organizations to develop risk mitigation strategies and make risk-aware decisions.

- Optimizing Resource Allocation: Comparative analysis assists in allocating resources efficiently by identifying areas where resources can be optimized for maximum impact.

- Driving Continuous Improvement: By comparing current performance with historical data or benchmarks, organizations can identify improvement areas and implement growth strategies.

Importance of Comparative Analysis in Decision-Making

- Data-Driven Decision-Making: Comparative analysis relies on empirical data and objective evaluation, reducing the influence of biases and subjective judgments in decision-making. It ensures decisions are based on facts and evidence.

- Objective Assessment: It provides an objective and structured framework for evaluating options, allowing decision-makers to focus on key criteria and avoid making decisions solely based on intuition or preferences.

- Risk Assessment: Comparative analysis helps assess and quantify risks associated with different options. This risk awareness enables organizations to make proactive risk management decisions.

- Prioritization: By ranking options based on predefined criteria, comparative analysis enables decision-makers to prioritize actions or investments, directing resources to areas with the most significant impact.

- Strategic Planning: It is integral to strategic planning, helping organizations align their decisions with overarching goals and objectives. Comparative analysis ensures decisions are consistent with long-term strategies.

- Resource Allocation: Organizations often have limited resources. Comparative analysis assists in allocating these resources effectively, ensuring they are directed toward initiatives with the highest potential returns.

- Continuous Improvement: Comparative analysis supports a culture of continuous improvement by identifying areas for enhancement and guiding iterative decision-making processes.

- Stakeholder Communication: It enhances transparency in decision-making, making it easier to communicate decisions to stakeholders. Stakeholders can better understand the rationale behind choices when supported by comparative analysis.

- Competitive Advantage: In business and competitive environments , comparative analysis can provide a competitive edge by identifying opportunities to outperform competitors or address weaknesses.

- Informed Innovation: When evaluating new products , technologies, or strategies, comparative analysis guides the selection of the most promising options, reducing the risk of investing in unsuccessful ventures.

In summary, comparative analysis is a valuable tool that empowers decision-makers across various domains to make informed, data-driven choices, manage risks, allocate resources effectively, and drive continuous improvement. Its structured approach enhances decision quality and transparency, contributing to the success and competitiveness of organizations and research endeavors.

How to Prepare for Comparative Analysis?

1. define objectives and scope.

Before you begin your comparative analysis, clearly defining your objectives and the scope of your analysis is essential. This step lays the foundation for the entire process. Here's how to approach it:

- Identify Your Goals: Start by asking yourself what you aim to achieve with your comparative analysis. Are you trying to choose between two products for your business? Are you evaluating potential investment opportunities? Knowing your objectives will help you stay focused throughout the analysis.

- Define Scope: Determine the boundaries of your comparison. What will you include, and what will you exclude? For example, if you're analyzing market entry strategies for a new product, specify whether you're looking at a specific geographic region or a particular target audience.

- Stakeholder Alignment: Ensure that all stakeholders involved in the analysis understand and agree on the objectives and scope. This alignment will prevent misunderstandings and ensure the analysis meets everyone's expectations.

2. Gather Relevant Data and Information

The quality of your comparative analysis heavily depends on the data and information you gather. Here's how to approach this crucial step:

- Data Sources: Identify where you'll obtain the necessary data. Will you rely on primary sources , such as surveys and interviews, to collect original data? Or will you use secondary sources, like published research and industry reports, to access existing data? Consider the advantages and disadvantages of each source.

- Data Collection Plan: Develop a plan for collecting data. This should include details about the methods you'll use, the timeline for data collection, and who will be responsible for gathering the data.

- Data Relevance: Ensure that the data you collect is directly relevant to your objectives. Irrelevant or extraneous data can lead to confusion and distract from the core analysis.

3. Select Appropriate Criteria for Comparison

Choosing the right criteria for comparison is critical to a successful comparative analysis. Here's how to go about it:

- Relevance to Objectives: Your chosen criteria should align closely with your analysis objectives. For example, if you're comparing job candidates, your criteria might include skills, experience, and cultural fit.

- Measurability: Consider whether you can quantify the criteria. Measurable criteria are easier to analyze. If you're comparing marketing campaigns, you might measure criteria like click-through rates, conversion rates, and return on investment.

- Weighting Criteria : Not all criteria are equally important. You'll need to assign weights to each criterion based on its relative importance. Weighting helps ensure that the most critical factors have a more significant impact on the final decision.

4. Establish a Clear Framework

Once you have your objectives, data, and criteria in place, it's time to establish a clear framework for your comparative analysis. This framework will guide your process and ensure consistency. Here's how to do it:

- Comparative Matrix: Consider using a comparative matrix or spreadsheet to organize your data. Each row in the matrix represents an option or entity you're comparing, and each column corresponds to a criterion. This visual representation makes it easy to compare and contrast data.

- Timeline: Determine the time frame for your analysis. Is it a one-time comparison, or will you conduct ongoing analyses? Having a defined timeline helps you manage the analysis process efficiently.

- Define Metrics: Specify the metrics or scoring system you'll use to evaluate each criterion. For example, if you're comparing potential office locations, you might use a scoring system from 1 to 5 for factors like cost, accessibility, and amenities.

With your objectives, data, criteria, and framework established, you're ready to move on to the next phase of comparative analysis: data collection and organization.

Comparative Analysis Data Collection

Data collection and organization are critical steps in the comparative analysis process. We'll explore how to gather and structure the data you need for a successful analysis.

1. Utilize Primary Data Sources

Primary data sources involve gathering original data directly from the source. This approach offers unique advantages, allowing you to tailor your data collection to your specific research needs.

Some popular primary data sources include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Design surveys or questionnaires and distribute them to collect specific information from individuals or groups. This method is ideal for obtaining firsthand insights, such as customer preferences or employee feedback.

- Interviews: Conduct structured interviews with relevant stakeholders or experts. Interviews provide an opportunity to delve deeper into subjects and gather qualitative data, making them valuable for in-depth analysis.

- Observations: Directly observe and record data from real-world events or settings. Observational data can be instrumental in fields like anthropology, ethnography, and environmental studies.

- Experiments: In controlled environments, experiments allow you to manipulate variables and measure their effects. This method is common in scientific research and product testing.

When using primary data sources, consider factors like sample size , survey design, and data collection methods to ensure the reliability and validity of your data.

2. Harness Secondary Data Sources

Secondary data sources involve using existing data collected by others. These sources can provide a wealth of information and save time and resources compared to primary data collection.

Here are common types of secondary data sources:

- Public Records: Government publications, census data, and official reports offer valuable information on demographics, economic trends, and public policies. They are often free and readily accessible.

- Academic Journals: Scholarly articles provide in-depth research findings across various disciplines. They are helpful for accessing peer-reviewed studies and staying current with academic discourse.

- Industry Reports: Industry-specific reports and market research publications offer insights into market trends, consumer behavior, and competitive landscapes. They are essential for businesses making strategic decisions.

- Online Databases: Online platforms like Statista , PubMed , and Google Scholar provide a vast repository of data and research articles. They offer search capabilities and access to a wide range of data sets.

When using secondary data sources, critically assess the credibility, relevance, and timeliness of the data. Ensure that it aligns with your research objectives.

3. Ensure and Validate Data Quality

Data quality is paramount in comparative analysis. Poor-quality data can lead to inaccurate conclusions and flawed decision-making. Here's how to ensure data validation and reliability:

- Cross-Verification: Whenever possible, cross-verify data from multiple sources. Consistency among different sources enhances the reliability of the data.

- Sample Size : Ensure that your data sample size is statistically significant for meaningful analysis. A small sample may not accurately represent the population.

- Data Integrity: Check for data integrity issues, such as missing values, outliers, or duplicate entries. Address these issues before analysis to maintain data quality.

- Data Source Reliability: Assess the reliability and credibility of the data sources themselves. Consider factors like the reputation of the institution or organization providing the data.

4. Organize Data Effectively

Structuring your data for comparison is a critical step in the analysis process. Organized data makes it easier to draw insights and make informed decisions. Here's how to structure data effectively:

- Data Cleaning: Before analysis, clean your data to remove inconsistencies, errors, and irrelevant information. Data cleaning may involve data transformation, imputation of missing values, and removing outliers.

- Normalization: Standardize data to ensure fair comparisons. Normalization adjusts data to a standard scale, making comparing variables with different units or ranges possible.

- Variable Labeling: Clearly label variables and data points for easy identification. Proper labeling enhances the transparency and understandability of your analysis.

- Data Organization: Organize data into a format that suits your analysis methods. For quantitative analysis, this might mean creating a matrix, while qualitative analysis may involve categorizing data into themes.

By paying careful attention to data collection, validation, and organization, you'll set the stage for a robust and insightful comparative analysis. Next, we'll explore various methodologies you can employ in your analysis, ranging from qualitative approaches to quantitative methods and examples.

Comparative Analysis Methods

When it comes to comparative analysis, various methodologies are available, each suited to different research goals and data types. In this section, we'll explore five prominent methodologies in detail.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a methodology often used when dealing with complex, non-linear relationships among variables. It seeks to identify patterns and configurations among factors that lead to specific outcomes.

- Case-by-Case Analysis: QCA involves evaluating individual cases (e.g., organizations, regions, or events) rather than analyzing aggregate data. Each case's unique characteristics are considered.

- Boolean Logic: QCA employs Boolean algebra to analyze data. Variables are categorized as either present or absent, allowing for the examination of different combinations and logical relationships.

- Necessary and Sufficient Conditions: QCA aims to identify necessary and sufficient conditions for a specific outcome to occur. It helps answer questions like, "What conditions are necessary for a successful product launch?"

- Fuzzy Set Theory: In some cases, QCA may use fuzzy set theory to account for degrees of membership in a category, allowing for more nuanced analysis.

QCA is particularly useful in fields such as sociology, political science, and organizational studies, where understanding complex interactions is essential.

Quantitative Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Comparative Analysis involves the use of numerical data and statistical techniques to compare and analyze variables. It's suitable for situations where data is quantitative, and relationships can be expressed numerically.

- Statistical Tools: Quantitative comparative analysis relies on statistical methods like regression analysis, correlation, and hypothesis testing. These tools help identify relationships, dependencies, and trends within datasets.

- Data Measurement: Ensure that variables are measured consistently using appropriate scales (e.g., ordinal, interval, ratio) for meaningful analysis. Variables may include numerical values like revenue, customer satisfaction scores, or product performance metrics.

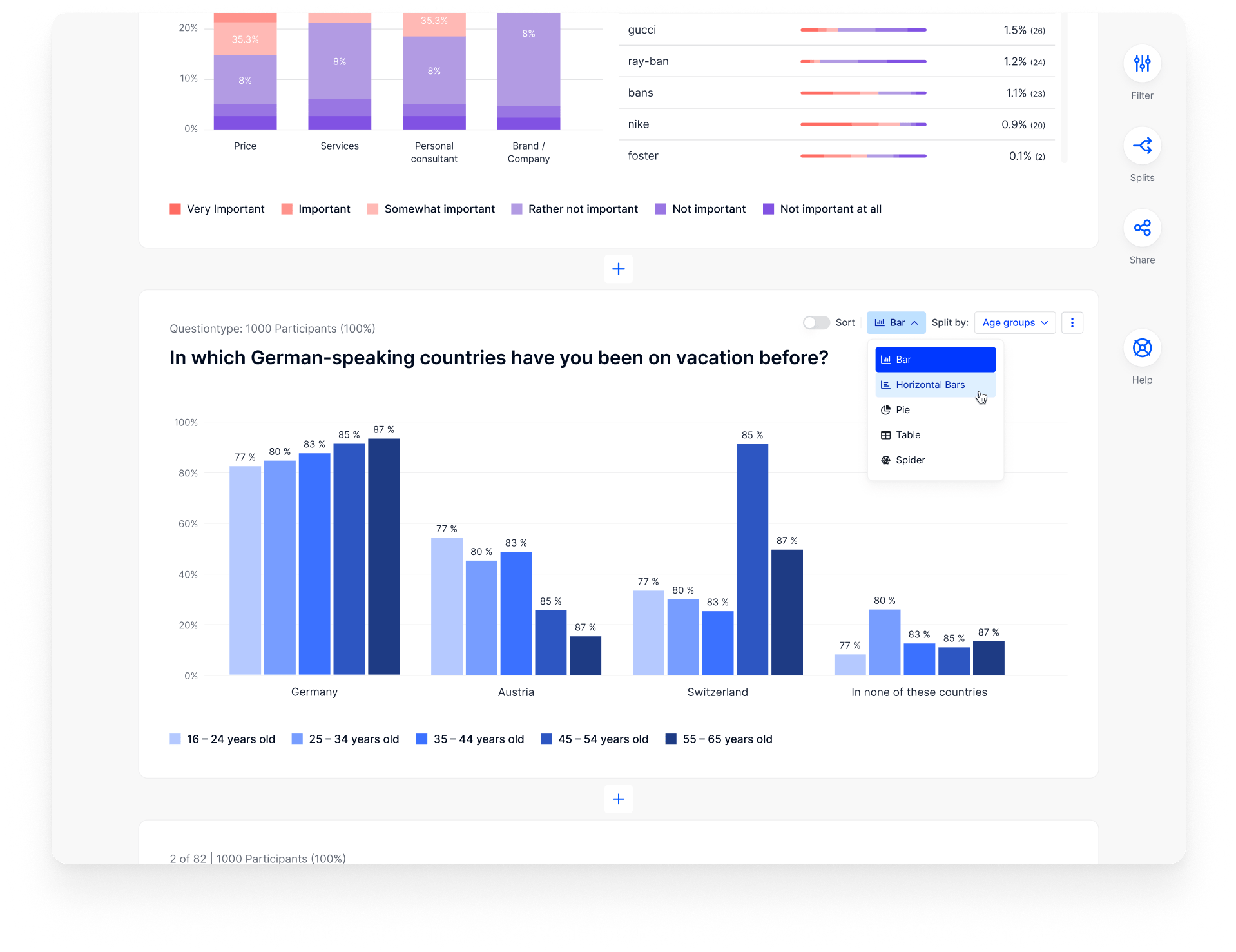

- Data Visualization: Create visual representations of data using charts, graphs, and plots. Visualization aids in understanding complex relationships and presenting findings effectively.

- Statistical Significance: Assess the statistical significance of relationships. Statistical significance indicates whether observed differences or relationships are likely to be real rather than due to chance.

Quantitative comparative analysis is commonly applied in economics, social sciences, and market research to draw empirical conclusions from numerical data.

Case Studies

Case studies involve in-depth examinations of specific instances or cases to gain insights into real-world scenarios. Comparative case studies allow researchers to compare and contrast multiple cases to identify patterns, differences, and lessons.

- Narrative Analysis: Case studies often involve narrative analysis, where researchers construct detailed narratives of each case, including context, events, and outcomes.

- Contextual Understanding: In comparative case studies, it's crucial to consider the context within which each case operates. Understanding the context helps interpret findings accurately.

- Cross-Case Analysis: Researchers conduct cross-case analysis to identify commonalities and differences across cases. This process can lead to the discovery of factors that influence outcomes.

- Triangulation: To enhance the validity of findings, researchers may use multiple data sources and methods to triangulate information and ensure reliability.

Case studies are prevalent in fields like psychology, business, and sociology, where deep insights into specific situations are valuable.

SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is a strategic tool used to assess the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats associated with a particular entity or situation. While it's commonly used in business, it can be adapted for various comparative analyses.

- Internal and External Factors: SWOT Analysis examines both internal factors (Strengths and Weaknesses), such as organizational capabilities, and external factors (Opportunities and Threats), such as market conditions and competition.

- Strategic Planning: The insights from SWOT Analysis inform strategic decision-making. By identifying strengths and opportunities, organizations can leverage their advantages. Likewise, addressing weaknesses and threats helps mitigate risks.

- Visual Representation: SWOT Analysis is often presented as a matrix or a 2x2 grid, making it visually accessible and easy to communicate to stakeholders.

- Continuous Monitoring: SWOT Analysis is not a one-time exercise. Organizations use it periodically to adapt to changing circumstances and make informed decisions.

SWOT Analysis is versatile and can be applied in business, healthcare, education, and any context where a structured assessment of factors is needed.

Benchmarking

Benchmarking involves comparing an entity's performance, processes, or practices to those of industry leaders or best-in-class organizations. It's a powerful tool for continuous improvement and competitive analysis.

- Identify Performance Gaps: Benchmarking helps identify areas where an entity lags behind its peers or industry standards. These performance gaps highlight opportunities for improvement.

- Data Collection: Gather data on key performance metrics from both internal and external sources. This data collection phase is crucial for meaningful comparisons.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare your organization's performance data with that of benchmark organizations. This analysis can reveal where you excel and where adjustments are needed.

- Continuous Improvement: Benchmarking is a dynamic process that encourages continuous improvement. Organizations use benchmarking findings to set performance goals and refine their strategies.

Benchmarking is widely used in business, manufacturing, healthcare, and customer service to drive excellence and competitiveness.

Each of these methodologies brings a unique perspective to comparative analysis, allowing you to choose the one that best aligns with your research objectives and the nature of your data. The choice between qualitative and quantitative methods, or a combination of both, depends on the complexity of the analysis and the questions you seek to answer.

How to Conduct Comparative Analysis?

Once you've prepared your data and chosen an appropriate methodology, it's time to dive into the process of conducting a comparative analysis. We will guide you through the essential steps to extract meaningful insights from your data.

1. Identify Key Variables and Metrics

Identifying key variables and metrics is the first crucial step in conducting a comparative analysis. These are the factors or indicators you'll use to assess and compare your options.

- Relevance to Objectives: Ensure the chosen variables and metrics align closely with your analysis objectives. When comparing marketing strategies, relevant metrics might include customer acquisition cost, conversion rate, and retention.

- Quantitative vs. Qualitative : Decide whether your analysis will focus on quantitative data (numbers) or qualitative data (descriptive information). In some cases, a combination of both may be appropriate.

- Data Availability: Consider the availability of data. Ensure you can access reliable and up-to-date data for all selected variables and metrics.

- KPIs: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are often used as the primary metrics in comparative analysis. These are metrics that directly relate to your goals and objectives.

2. Visualize Data for Clarity

Data visualization techniques play a vital role in making complex information more accessible and understandable. Effective data visualization allows you to convey insights and patterns to stakeholders. Consider the following approaches:

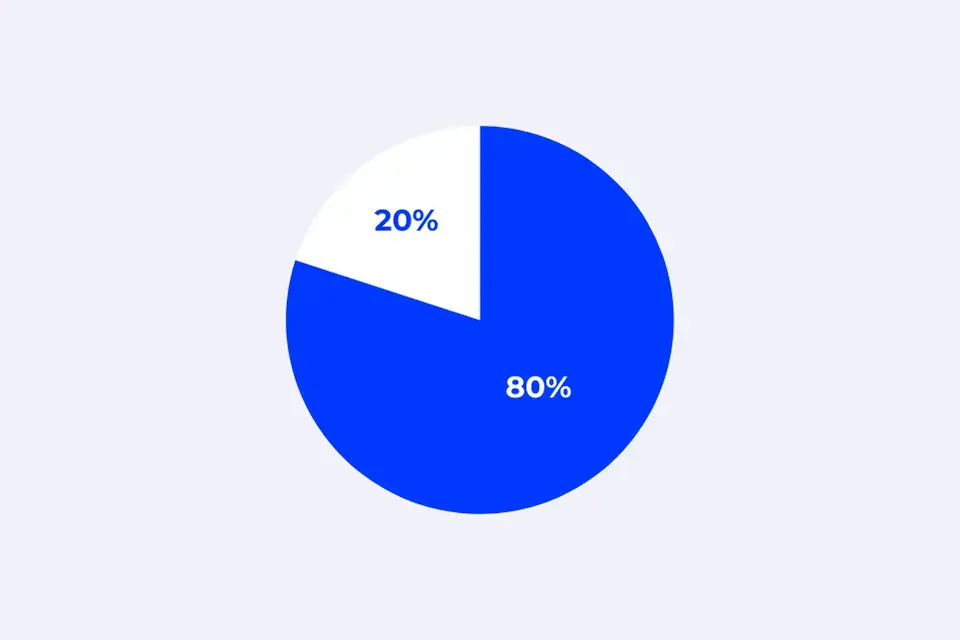

- Charts and Graphs: Use various types of charts, such as bar charts, line graphs, and pie charts, to represent data. For example, a line graph can illustrate trends over time, while a bar chart can compare values across categories.

- Heatmaps: Heatmaps are particularly useful for visualizing large datasets and identifying patterns through color-coding. They can reveal correlations, concentrations, and outliers.

- Scatter Plots: Scatter plots help visualize relationships between two variables. They are especially useful for identifying trends, clusters, or outliers.

- Dashboards: Create interactive dashboards that allow users to explore data and customize views. Dashboards are valuable for ongoing analysis and reporting.

- Infographics: For presentations and reports, consider using infographics to summarize key findings in a visually engaging format.

Effective data visualization not only enhances understanding but also aids in decision-making by providing clear insights at a glance.

3. Establish Clear Comparative Frameworks

A well-structured comparative framework provides a systematic approach to your analysis. It ensures consistency and enables you to make meaningful comparisons. Here's how to create one:

- Comparison Matrices: Consider using matrices or spreadsheets to organize your data. Each row represents an option or entity, and each column corresponds to a variable or metric. This matrix format allows for side-by-side comparisons.

- Decision Trees: In complex decision-making scenarios, decision trees help map out possible outcomes based on different criteria and variables. They visualize the decision-making process.

- Scenario Analysis: Explore different scenarios by altering variables or criteria to understand how changes impact outcomes. Scenario analysis is valuable for risk assessment and planning.

- Checklists: Develop checklists or scoring sheets to systematically evaluate each option against predefined criteria. Checklists ensure that no essential factors are overlooked.

A well-structured comparative framework simplifies the analysis process, making it easier to draw meaningful conclusions and make informed decisions.

4. Evaluate and Score Criteria

Evaluating and scoring criteria is a critical step in comparative analysis, as it quantifies the performance of each option against the chosen criteria.

- Scoring System: Define a scoring system that assigns values to each criterion for every option. Common scoring systems include numerical scales, percentage scores, or qualitative ratings (e.g., high, medium, low).

- Consistency: Ensure consistency in scoring by defining clear guidelines for each score. Provide examples or descriptions to help evaluators understand what each score represents.

- Data Collection: Collect data or information relevant to each criterion for all options. This may involve quantitative data (e.g., sales figures) or qualitative data (e.g., customer feedback).

- Aggregation: Aggregate the scores for each option to obtain an overall evaluation. This can be done by summing the individual criterion scores or applying weighted averages.

- Normalization: If your criteria have different measurement scales or units, consider normalizing the scores to create a level playing field for comparison.

5. Assign Importance to Criteria

Not all criteria are equally important in a comparative analysis. Weighting criteria allows you to reflect their relative significance in the final decision-making process.

- Relative Importance: Assess the importance of each criterion in achieving your objectives. Criteria directly aligned with your goals may receive higher weights.

- Weighting Methods: Choose a weighting method that suits your analysis. Common methods include expert judgment, analytic hierarchy process (AHP), or data-driven approaches based on historical performance.

- Impact Analysis: Consider how changes in the weights assigned to criteria would affect the final outcome. This sensitivity analysis helps you understand the robustness of your decisions.

- Stakeholder Input: Involve relevant stakeholders or decision-makers in the weighting process. Their input can provide valuable insights and ensure alignment with organizational goals.

- Transparency: Clearly document the rationale behind the assigned weights to maintain transparency in your analysis.

By weighting criteria, you ensure that the most critical factors have a more significant influence on the final evaluation, aligning the analysis more closely with your objectives and priorities.

With these steps in place, you're well-prepared to conduct a comprehensive comparative analysis. The next phase involves interpreting your findings, drawing conclusions, and making informed decisions based on the insights you've gained.

Comparative Analysis Interpretation

Interpreting the results of your comparative analysis is a crucial phase that transforms data into actionable insights. We'll delve into various aspects of interpretation and how to make sense of your findings.

- Contextual Understanding: Before diving into the data, consider the broader context of your analysis. Understand the industry trends, market conditions, and any external factors that may have influenced your results.

- Drawing Conclusions: Summarize your findings clearly and concisely. Identify trends, patterns, and significant differences among the options or variables you've compared.

- Quantitative vs. Qualitative Analysis: Depending on the nature of your data and analysis, you may need to balance both quantitative and qualitative interpretations. Qualitative insights can provide context and nuance to quantitative findings.

- Comparative Visualization: Visual aids such as charts, graphs, and tables can help convey your conclusions effectively. Choose visual representations that align with the nature of your data and the key points you want to emphasize.

- Outliers and Anomalies: Identify and explain any outliers or anomalies in your data. Understanding these exceptions can provide valuable insights into unusual cases or factors affecting your analysis.

- Cross-Validation: Validate your conclusions by comparing them with external benchmarks, industry standards, or expert opinions. Cross-validation helps ensure the reliability of your findings.

- Implications for Decision-Making: Discuss how your analysis informs decision-making. Clearly articulate the practical implications of your findings and their relevance to your initial objectives.

- Actionable Insights: Emphasize actionable insights that can guide future strategies, policies, or actions. Make recommendations based on your analysis, highlighting the steps needed to capitalize on strengths or address weaknesses.

- Continuous Improvement: Encourage a culture of continuous improvement by using your analysis as a feedback mechanism. Suggest ways to monitor and adapt strategies over time based on evolving circumstances.

Comparative Analysis Applications

Comparative analysis is a versatile methodology that finds application in various fields and scenarios. Let's explore some of the most common and impactful applications.

Business Decision-Making

Comparative analysis is widely employed in business to inform strategic decisions and drive success. Key applications include:

Market Research and Competitive Analysis

- Objective: To assess market opportunities and evaluate competitors.

- Methods: Analyzing market trends, customer preferences, competitor strengths and weaknesses, and market share.

- Outcome: Informed product development, pricing strategies, and market entry decisions.

Product Comparison and Benchmarking

- Objective: To compare the performance and features of products or services.

- Methods: Evaluating product specifications, customer reviews, and pricing.

- Outcome: Identifying strengths and weaknesses, improving product quality, and setting competitive pricing.

Financial Analysis

- Objective: To evaluate financial performance and make investment decisions.

- Methods: Comparing financial statements, ratios, and performance indicators of companies.

- Outcome: Informed investment choices, risk assessment, and portfolio management.

Healthcare and Medical Research

In the healthcare and medical research fields, comparative analysis is instrumental in understanding diseases, treatment options, and healthcare systems.

Clinical Trials and Drug Development

- Objective: To compare the effectiveness of different treatments or drugs.

- Methods: Analyzing clinical trial data, patient outcomes, and side effects.

- Outcome: Informed decisions about drug approvals, treatment protocols, and patient care.

Health Outcomes Research

- Objective: To assess the impact of healthcare interventions.

- Methods: Comparing patient health outcomes before and after treatment or between different treatment approaches.

- Outcome: Improved healthcare guidelines, cost-effectiveness analysis, and patient care plans.

Healthcare Systems Evaluation

- Objective: To assess the performance of healthcare systems.

- Methods: Comparing healthcare delivery models, patient satisfaction, and healthcare costs.

- Outcome: Informed healthcare policy decisions, resource allocation, and system improvements.

Social Sciences and Policy Analysis

Comparative analysis is a fundamental tool in social sciences and policy analysis, aiding in understanding complex societal issues.

Educational Research

- Objective: To compare educational systems and practices.

- Methods: Analyzing student performance, curriculum effectiveness, and teaching methods.

- Outcome: Informed educational policies, curriculum development, and school improvement strategies.

Political Science

- Objective: To study political systems, elections, and governance.

- Methods: Comparing election outcomes, policy impacts, and government structures.

- Outcome: Insights into political behavior, policy effectiveness, and governance reforms.

Social Welfare and Poverty Analysis

- Objective: To evaluate the impact of social programs and policies.

- Methods: Comparing the well-being of individuals or communities with and without access to social assistance.

- Outcome: Informed policymaking, poverty reduction strategies, and social program improvements.

Environmental Science and Sustainability

Comparative analysis plays a pivotal role in understanding environmental issues and promoting sustainability.

Environmental Impact Assessment

- Objective: To assess the environmental consequences of projects or policies.

- Methods: Comparing ecological data, resource use, and pollution levels.

- Outcome: Informed environmental mitigation strategies, sustainable development plans, and regulatory decisions.

Climate Change Analysis

- Objective: To study climate patterns and their impacts.

- Methods: Comparing historical climate data, temperature trends, and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Outcome: Insights into climate change causes, adaptation strategies, and policy recommendations.

Ecosystem Health Assessment

- Objective: To evaluate the health and resilience of ecosystems.

- Methods: Comparing biodiversity, habitat conditions, and ecosystem services.

- Outcome: Conservation efforts, restoration plans, and ecological sustainability measures.

Technology and Innovation

Comparative analysis is crucial in the fast-paced world of technology and innovation.

Product Development and Innovation

- Objective: To assess the competitiveness and innovation potential of products or technologies.

- Methods: Comparing research and development investments, technology features, and market demand.

- Outcome: Informed innovation strategies, product roadmaps, and patent decisions.

User Experience and Usability Testing

- Objective: To evaluate the user-friendliness of software applications or digital products.

- Methods: Comparing user feedback, usability metrics, and user interface designs.

- Outcome: Improved user experiences, interface redesigns, and product enhancements.

Technology Adoption and Market Entry

- Objective: To analyze market readiness and risks for new technologies.

- Methods: Comparing market conditions, regulatory landscapes, and potential barriers.

- Outcome: Informed market entry strategies, risk assessments, and investment decisions.

These diverse applications of comparative analysis highlight its flexibility and importance in decision-making across various domains. Whether in business, healthcare, social sciences, environmental studies, or technology, comparative analysis empowers researchers and decision-makers to make informed choices and drive positive outcomes.

Comparative Analysis Best Practices

Successful comparative analysis relies on following best practices and avoiding common pitfalls. Implementing these practices enhances the effectiveness and reliability of your analysis.

- Clearly Defined Objectives: Start with well-defined objectives that outline what you aim to achieve through the analysis. Clear objectives provide focus and direction.

- Data Quality Assurance: Ensure data quality by validating, cleaning, and normalizing your data. Poor-quality data can lead to inaccurate conclusions.

- Transparent Methodologies: Clearly explain the methodologies and techniques you've used for analysis. Transparency builds trust and allows others to assess the validity of your approach.

- Consistent Criteria: Maintain consistency in your criteria and metrics across all options or variables. Inconsistent criteria can lead to biased results.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct sensitivity analysis by varying key parameters, such as weights or assumptions, to assess the robustness of your conclusions.

- Stakeholder Involvement: Involve relevant stakeholders throughout the analysis process. Their input can provide valuable perspectives and ensure alignment with organizational goals.

- Critical Evaluation of Assumptions: Identify and critically evaluate any assumptions made during the analysis. Assumptions should be explicit and justifiable.

- Holistic View: Take a holistic view of the analysis by considering both short-term and long-term implications. Avoid focusing solely on immediate outcomes.

- Documentation: Maintain thorough documentation of your analysis, including data sources, calculations, and decision criteria. Documentation supports transparency and facilitates reproducibility.

- Continuous Learning: Stay updated with the latest analytical techniques, tools, and industry trends. Continuous learning helps you adapt your analysis to changing circumstances.

- Peer Review: Seek peer review or expert feedback on your analysis. External perspectives can identify blind spots and enhance the quality of your work.

- Ethical Considerations: Address ethical considerations, such as privacy and data protection, especially when dealing with sensitive or personal data.

By adhering to these best practices, you'll not only improve the rigor of your comparative analysis but also ensure that your findings are reliable, actionable, and aligned with your objectives.

Comparative Analysis Examples

To illustrate the practical application and benefits of comparative analysis, let's explore several real-world examples across different domains. These examples showcase how organizations and researchers leverage comparative analysis to make informed decisions, solve complex problems, and drive improvements:

Retail Industry - Price Competitiveness Analysis

Objective: A retail chain aims to assess its price competitiveness against competitors in the same market.

Methodology:

- Collect pricing data for a range of products offered by the retail chain and its competitors.

- Organize the data into a comparative framework, categorizing products by type and price range.

- Calculate price differentials, averages, and percentiles for each product category.

- Analyze the findings to identify areas where the retail chain's prices are higher or lower than competitors.

Outcome: The analysis reveals that the retail chain's prices are consistently lower in certain product categories but higher in others. This insight informs pricing strategies, allowing the retailer to adjust prices to remain competitive in the market.

Healthcare - Comparative Effectiveness Research

Objective: Researchers aim to compare the effectiveness of two different treatment methods for a specific medical condition.

- Recruit patients with the medical condition and randomly assign them to two treatment groups.

- Collect data on treatment outcomes, including symptom relief, side effects, and recovery times.

- Analyze the data using statistical methods to compare the treatment groups.

- Consider factors like patient demographics and baseline health status as potential confounding variables.

Outcome: The comparative analysis reveals that one treatment method is statistically more effective than the other in relieving symptoms and has fewer side effects. This information guides medical professionals in recommending the more effective treatment to patients.

Environmental Science - Carbon Emission Analysis

Objective: An environmental organization seeks to compare carbon emissions from various transportation modes in a metropolitan area.

- Collect data on the number of vehicles, their types (e.g., cars, buses, bicycles), and fuel consumption for each mode of transportation.

- Calculate the total carbon emissions for each mode based on fuel consumption and emission factors.

- Create visualizations such as bar charts and pie charts to represent the emissions from each transportation mode.

- Consider factors like travel distance, occupancy rates, and the availability of alternative fuels.

Outcome: The comparative analysis reveals that public transportation generates significantly lower carbon emissions per passenger mile compared to individual car travel. This information supports advocacy for increased public transit usage to reduce carbon footprint.

Technology Industry - Feature Comparison for Software Development Tools

Objective: A software development team needs to choose the most suitable development tool for an upcoming project.

- Create a list of essential features and capabilities required for the project.

- Research and compile information on available development tools in the market.

- Develop a comparative matrix or scoring system to evaluate each tool's features against the project requirements.

- Assign weights to features based on their importance to the project.

Outcome: The comparative analysis highlights that Tool A excels in essential features critical to the project, such as version control integration and debugging capabilities. The development team selects Tool A as the preferred choice for the project.

Educational Research - Comparative Study of Teaching Methods

Objective: A school district aims to improve student performance by comparing the effectiveness of traditional classroom teaching with online learning.

- Randomly assign students to two groups: one taught using traditional methods and the other through online courses.

- Administer pre- and post-course assessments to measure knowledge gain.

- Collect feedback from students and teachers on the learning experiences.

- Analyze assessment scores and feedback to compare the effectiveness and satisfaction levels of both teaching methods.

Outcome: The comparative analysis reveals that online learning leads to similar knowledge gains as traditional classroom teaching. However, students report higher satisfaction and flexibility with the online approach. The school district considers incorporating online elements into its curriculum.

These examples illustrate the diverse applications of comparative analysis across industries and research domains. Whether optimizing pricing strategies in retail, evaluating treatment effectiveness in healthcare, assessing environmental impacts, choosing the right software tool, or improving educational methods, comparative analysis empowers decision-makers with valuable insights for informed choices and positive outcomes.

Conclusion for Comparative Analysis

Comparative analysis is your compass in the world of decision-making. It helps you see the bigger picture, spot opportunities, and navigate challenges. By defining your objectives, gathering data, applying methodologies, and following best practices, you can harness the power of Comparative Analysis to make informed choices and drive positive outcomes.

Remember, Comparative analysis is not just a tool; it's a mindset that empowers you to transform data into insights and uncertainty into clarity. So, whether you're steering a business, conducting research, or facing life's choices, embrace Comparative Analysis as your trusted guide on the journey to better decisions. With it, you can chart your course, make impactful choices, and set sail toward success.

How to Conduct Comparative Analysis in Minutes?

Are you ready to revolutionize your approach to market research and comparative analysis? Appinio , a real-time market research platform, empowers you to harness the power of real-time consumer insights for swift, data-driven decisions. Here's why you should choose Appinio:

- Speedy Insights: Get from questions to insights in minutes, enabling you to conduct comparative analysis without delay.

- User-Friendly: No need for a PhD in research – our intuitive platform is designed for everyone, making it easy to collect and analyze data.

- Global Reach: With access to over 90 countries and the ability to define your target group from 1200+ characteristics, Appinio provides a worldwide perspective for your comparative analysis

Get free access to the platform!

Join the loop 💌

Be the first to hear about new updates, product news, and data insights. We'll send it all straight to your inbox.

Get the latest market research news straight to your inbox! 💌

Wait, there's more

30.05.2024 | 29min read

Pareto Analysis: Definition, Pareto Chart, Examples

28.05.2024 | 32min read

What is Systematic Sampling? Definition, Types, Examples

16.05.2024 | 30min read

Time Series Analysis: Definition, Types, Techniques, Examples

Comparative Analysis

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Kenisha Blair-Walcott 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

4784 Accesses

Comparative analysis is a multidisciplinary method, which spans a wide cross-section of disciplines (Azarian, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(4), 113–125 (2014)). It is the process of comparing multiple units of study for the purpose of scientific discovery and for informing policy decisions (Rogers, Comparative effectiveness research, 2014). Even though there has been a renewed interest in comparative analysis as a research method over the last decade in fields such as education, it has been used in studies for decades.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout