The Senior Thesis

From the outset of their time at Princeton, students are encouraged and challenged to develop their scholarly interests and to evolve as independent thinkers.

The culmination of this process is the senior thesis, which provides a unique opportunity for students to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing. At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project.

Integral to the senior thesis process is the opportunity to work one-on-one with a faculty member who guides the development of the project. Thesis writers and advisers agree that the most valuable outcome of the senior thesis is the chance for students to enhance skills that are the foundation of future success, including creativity, intellectual engagement, mental discipline and the ability to meet new challenges.

Many students develop projects from ideas sparked in the classes they’ve taken; others fashion their topics on the basis of long-standing personal passions. Most thesis writers encounter the intellectual twists and turns of any good research project, where the questions emerge as they proceed, often taking them in unexpected directions.

Planning for the senior thesis starts in earnest in the junior year, when students complete a significant research project known as the junior paper. Students who plan ahead can make good use of the University's considerable resources, such as receiving University funds to do research in the United States or abroad. Other students use summer internships as a launching pad for their thesis. For some science and engineering projects, students stay on campus the summer before their senior year to get a head start on lab work.

Writing a thesis encourages the self-confidence and high ambitions that come from mastering a difficult challenge. It fosters the development of specific skills and habits of mind that augur well for future success. No wonder generations of graduates look back on the senior thesis as the most valuable academic component of their Princeton experience.

Navigating Colombia’s Magdalena River, One Story At A Time

For his senior thesis, Jordan Salama, a Spanish and Portuguese major, produced a nonfiction book of travel writing about the people and places along Colombia’s main river, the Magdalena.

Embracing the Classics to Inform Policymaking for Public Education

For her senior thesis, Emma Treadwayconsiders how the basic tenets of Stoicism — a school of philosophy that dates from 300 BCE — can teach students to engage empathetically with the world and address inequities in the classroom.

Creating A Faster, Cheaper and Greener Chemical Reaction

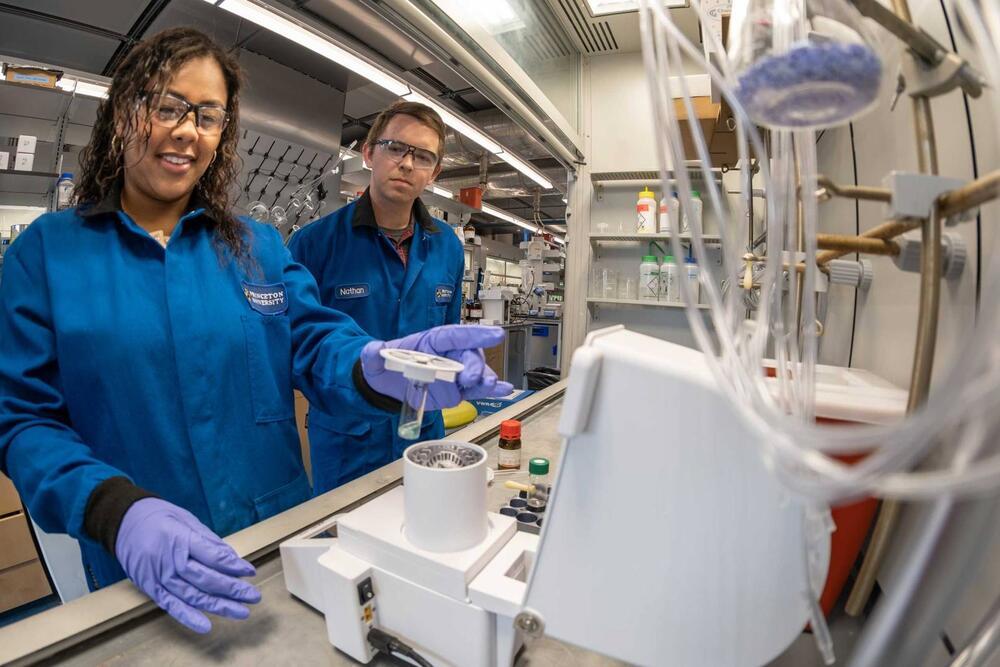

One way to make drugs more affordable is to make them cheaper to produce. For her senior thesis research, Cassidy Humphreys, a chemistry major with a passion for medicine, took on the challenge of taking a century-old formula at the core of many modern medications — and improving it.

The Humanity of Improvisational Dance

Esin Yunusoglu investigated how humans move together and exist in a space — both on the dance floor and in real life — for the choreography she created as her senior thesis in dance, advised by Professor of Dance Susan Marshall.

From the Blog

The infamous senior thesis, revisiting wwii: my senior thesis, independent work in its full glory, advisers, independent work and beyond.

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

- PUL Quick Answers

- Special Collections

Q. How do I access Princeton University Senior Theses?

- Economics & Finance

- General Library

- Interlibrary Loan & ArticleExpress

- 1 Appraisals

- 1 Conservation

- 5 Digitization

- 2 Donations

- 5 Princeton University

- 1 Publications

- 10 Research help

- 1 Rights & Permissions

- 6 University Archives

Answered By: Mudd Library Last Updated: Dec 18, 2023 Views: 3393

The Princeton University Archives located in the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library is the official repository for Princeton University undergraduate senior theses from 1924 to the present.

Digital and Original Format Senior Theses

Members of the University community with an active NetID can access digital theses in Dataspace when connected to any Princeton-networked computer (if you’re not on campus, please first connect to the campus network via the GlobalProtect or SonicWall desktop applications).

Independent researchers who are not members of the University community (including Princeton alumni) should use the Library Catalog or DataSpace to browse senior theses.

Please create a Special Collections Research Account , if you don’t already have an active account, prior to submitting the Senior Thesis Order Form. In some cases we will be unable to digitize the senior thesis due to an embargo that prohibits digital access. Copyright of the theses are held by the author.

Senior Thesis Order Form

Please note: your order can only be fulfilled if you have completed the Senior Thesis Order Form and have a current Special Collections Research Account. Due to high volume, staff are unable to respond to requests without the necessary information.

Original Format Senior Theses - In person

- You are welcome to view senior theses that have not been scanned or born-digital in our reading room at Mudd Library . No appointment is needed during our academic hours which are Monday through Friday, 9:00 AM - 4:45 PM.

- We recommend researchers create a Special Collections Research Account to submit online requests for material in advance of your visit. Material can be requested through the Princeton University Catalog . We encourage you to submit your requests in advance. Once you have arrived and been signed into the reading room, we will page up to 6 items at a time. If you are having any issues with registering or requesting materials, we can assist you by submitting an Ask Us! or when you arrive in person.

Please note : Researchers will be asked to show a photo ID such as a driver's license or academic/work ID upon arrival to Special Collections reading rooms. While it is not required at Mudd, we do recommend making your way to Firestone Library to obtain an Access Card as it will ease future visits. Should you not obtain an Access Card, you will need to show your photo ID at each visit to Mudd Library. Visitors to Firestone Library are required to obtain an Access Card to make it easy to enter the library's turnstiles.

Laptops, cell phones, cameras and pencils are permitted in the reading room. All other personal belongings can be placed in one of our free, secure lockers. More information about reading room guidelines can be found on our website . If you have accessibility needs that will impact your ability to conduct your research effectively or comfortably, please don’t hesitate to let me know and our team will do our best to accommodate you.

For additional information, please visit Theses & Dissertations page of our website. Please direct any questions you may have to Special Collections staff via Ask Us! .

Links & Files

- How can I access Special Collections?

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 1 No 1

Related Topics

- Princeton University

- Research help

- University Archives

- Digitization

Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2023

Members of the princeton community wishing to view a senior thesis from 2014 and later while away from campus should follow the instructions outlined on the oit website for connecting to campus resources remotely..

- Communities Collections

Collections in this community

Aeronautical engineering, 1945-1975, african american studies, 2020-2023, anthropology, 1961-2023, architecture school, 1968-2023, art and archaeology, 1926-2023, astrophysical sciences, 1990-2023, biochemical sciences, 1968-1985, biology, 1925-1990, chemical and biological engineering, 1931-2023, chemistry, 1926-2023, civil and environmental engineering, 2000-2023, civil engineering and operations research, 1931-2000, classics, 1934-2023, comparative literature, 1975-2023, computer science, 1987-2023, creative writing program, 1995-2023, east asian studies, 1951-2023, east asian studies program, 2017-2022, ecology and evolutionary biology, 1992-2023, economics, 1927-2023, electrical and computer engineering, 1932-2023, engineering and applied science, 1933-1987, english, 1925-2023, french and italian, 2002-2023, geosciences, 1929-2023, german, 1958-2023, global health and health policy program, 2017-2023, history, 1926-2023, independent concentration, 1972-2023, mathematics, 1934-2023, mechanical and aerospace engineering, 1924-2023, medieval studies, 1976-1981, modern languages, 1926-1958, molecular biology, 1954-2023, music, 1948-2023, near eastern studies, 1969-2023, neuroscience, 2017-2023, operations research and financial engineering, 2000-2023, oriental studies, 1959-1969, philosophy, 1924-2023, physics, 1936-2023, politics, 1927-2023, princeton school of public and international affairs, 1929-2023, program in dance, program in visual arts, psychology, 1930-2023, religion, 1946-2023, robotics and intelligent systems program, romance languages and literatures, 1928-2002, slavic languages and literature, 1962-2023, sociology, 1954-2023, south asian studies program, spanish and portuguese, 2002-2023, special program in humanities, 1936-1972, statistics, 1967-1985, theater program, 1940-2023.

Search form

Inbox thesis trauma and a recurring nightmare.

The recent PAW thesis piece honors the glories of the senior thesis, but doesn’t spend much time on the agonies.

As a Nassoon, I spent year after year watching my good friends senior to me go through the rituals of getting their theses done, such that I had acquired a good case of “thesis PTSD” by my senior year.

I hated my carrel, used only for working with books that had to say in the “libe”; wrote my thesis in a two-week marathon session of getting up at noon, eating lunch, then writing until 6 the next morning (visited nightly at 3 a.m. by the herds of cockroaches who lived in Laughlin Hall); and finished a pedestrian effort that earned me the Princeton equivalent of a B+, then graduated.

Looking back, I so regret the lost opportunity to really do something with my thesis (as I regret not majoring in history to study the 20th century, as I do now on my own). I also marvel at how that effort seemed so daunting looking back from much higher hills conquered in later life.

For decades afterward, I periodically had the thesis equivalent of the famous “exam dream” — It’s due today! Have I started it? Where do I turn it in? No wait, I was an early concentrator and actually wrote it last year — whew! Or did I? Ugh!

#PolicyProfile: Fernando Pernas, MPA '24

My great-grandmother was one of the first female candidates for vice president in Latin America and navigated the perilous waters of politics and activism during a time of brutal political oppression. Driven by a deep-seated commitment to justice, free speech, and democratic principles, she consistently chose to do what she believed was right, regardless of the potential consequences. Her legacy has motivated me to pursue a career in civil service and to actively participate in transformative processes within the public sector. While studying economics at @pucmm, I developed a passion for economic development, particularly the transformative processes that enhance a nation's productivity, prosperity, and overall well-being.

This interest convinced me that a career in civil service would enable me to actively participate in and influence these transformative processes from within the public sector. Fernando Pernas, MPA '24

I spent five years working for the Dominican Republic government in organizations such as the Central Bank, the Ministry of Economy, Development and Planning, and the Ministry of Industry and Commerce. I've seen firsthand that having good policymakers in macroeconomic areas creates financial and political stability that fosters growth. The country's growth has been some of the highest in the world in the last 20 years. The highlight of my time there was working on the COVID response task force and creating emergency economic and social relief programs. Despite the high uncertainty at the time, we were able to create cash transfer programs that helped millions of people. Studies have shown that as many as 400,000 people didn't fall below the poverty line because of these programs. My long-term goal is to return to the DR and work in government, and I am committed to pursuing good, evidence-based policymaking. I am driven by the understanding that while good policy does not automatically ensure economic development, bad policy can decidedly undermine it.

At SPIA, We Care

Our community.

- Global Elections

- About Speakers Bureau Careers

How Princeton got burned by its outreach to Iran

Sign up for Semafor Principals: What the White House is reading. Read it now .

In this article:

The View From Princeton

The view from iran.

As US-Iran relations thawed during the Obama administration, Princeton University saw an opportunity to make the school a central player in bridging the decades-long divide between the two antagonists. It established an Iran center, welcomed a senior Iranian diplomat to its ivy-coated halls, and pursued a student exchange program with Iran.

But within a dozen years, two of Princeton’s graduate students had been detained or kidnapped by Tehran and its military proxies. And a Republican-led Congress is now formally probing the school’s ties to Iranian regime officials.

Princeton’s experience is a cautionary tale of how American institutions can be ensnared in the internal politics of Tehran and Washington and become pawns in those battles, even as they see themselves as working towards noble goals. After Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, Princeton is also another Ivy League school that is seeking to balance academic freedom with scholarship and speech that some US lawmakers and educators believe are hostile to American interests.

Princeton’s ambitions to position itself as an arbiter in reducing tensions between Iran and the US are clear in a large cache of Iranian foreign ministry emails obtained by Iran International, a Persian-language television channel banned in Iran, and shared with Semafor. They’re also illustrated in the Princeton faculty’s extensive writings, speeches, and appearances focused on Iran.

Students abducted

Princeton’s student exchange program first took off in 2014, when a prominent Iranian-American scholar and future Biden administration official, Ariane Tabatabai, connected the Iran center’s then-associate director to Mostafa Zahrani, a senior Iranian foreign ministry diplomat with strong ties to his country’s elite military force, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). “I wanted to introduce you to a friend who is in Princeton, and you will see him in Vienna in three weeks,” Tabatabai wrote, cc’ing Kevan Harris, the then associate director. “He is interested in sharing with you a plan to send Iranian students to Princeton and to send American students to Iran.”

Harris jumped at this opening, according to correspondence seen by Semafor, and arranged to see Zahrani in Austria two weeks later on the sidelines of the nuclear negotiations that were taking place between Iran, the US, and other global powers. The follow-up took time, but by early 2015, Princeton welcomed its first candidate for the Iran program: a Chinese-American graduate student named Wang Xiyue.

Wang was hesitant about going to Tehran, he told Semafor in recent interviews. He didn’t speak Farsi, and his Ph.D. work initially focused on the Soviet Union’s role in Central Asia, rather than issues related to Iran itself. He also raised with Princeton his concerns about security, given Iran’s history of abducting American citizens and the fact Tehran had no diplomatic ties with Washington.

On Dec. 1, 2015, Wang emailed administrators that he felt he needed to be as specific as possible about his scholarship with Iranian officials to protect himself once on the ground. “[A]s a US citizen of non-Iranian descen[t], I think it would be preferable for me to be as transparent as possible so that I would not be deported from the country for doing things my visa does not prescribe me to do,” he wrote.

But Harris and other Princeton officials reassured Wang about his safety and the importance of learning Farsi in Iran, both for his dissertation and future academic work. “It’s a good time to go [to Iran] — looks like they are in a good mood over there,” Harris wrote to Wang in the weeks before his January 2016 departure. “Take advantage of it.”

Wang’s reservations proved to be right. Six months after his arrival in Tehran, Iran’s intelligence ministry confiscated his US passport. On Aug. 7, 2016, he was arrested on espionage charges and sent to Iran’s feared Evin Prison, where he spent more than three years, at times in solitary confinement and threatened with death.

Princeton denied that it in any way downplayed the risks of travel to Iran nor pressured Wang into joining the exchange program. “Princeton did not direct, and indeed did not have the power to direct, Mr. Wang’s travel,” university spokesman Michael Hotchkiss told Semafor. “And it was Princeton University that undertook a relentless, multi-year and multi-million-dollar global effort to secure his release.”

Last year, a second Princeton graduate student, Elizabeth Tsurkov, was abducted by an Iranian-backed militia in Iraq. She hasn’t been seen since last November.

Tsurkov’s journey to Princeton was an unusual one. The academic and journalist was born in Russia, raised and educated in Israel, and earned her master’s degree in social science from the University of Chicago in 2019 with a 3.9 GPA. Throughout this time, she showed a remarkable ability — particularly for an Israeli — to engage the Middle East’s religious groups, militias, and political movements in hotspots like Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon.

Tsurkov has said in published interviews that she began her reporting through the heavy use of social media. Fluent in Arabic, she employed Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp to document the plight of people caught in war zones, and amassed a substantial online following and network in the process. She also used her Russian passport to visit Arab countries that are largely off limits to Israelis.

Tsurkov has acknowledged that her citizenship and religion unnerved some of her contacts. But her colleagues and family said that her writings, which have focused heavily on the plight of victims of regional and sectarian violence — including Palestinians — have allowed her to gain and maintain the trust of the groups and individuals she’s documenting. Among her affiliations is an Israeli-Palestinian think tank that educates Israelis on Islam and their Arab neighbors in a bid to support the peace process.

“I think that what drives all of them, at the end of the day, to speak to me is a feeling that I care about them, and I want to properly reflect their perspectives and their views,” Tsurkov told the media outlet Al-Monitor in a 2021 podcast.

Tsurkov’s doctoral work at Princeton was focused on the patronage systems that underpin political movements in Lebanon, Iraq, and Iraqi Kurdistan and why their members often remain loyal to feudal and sectarian leaders who deliver little economic development in return. In her thesis proposal from 2021, which was approved and funded by Princeton, she outlined the travels she’d made, and would continue to make, to Baghdad, northern Iraq, and Lebanon.

Tsurkov was kidnapped on March 21, 2023 from a cafe in the central Baghdad neighborhood of Karrada, just days after undergoing back surgery in an Iraqi hospital for a herniated disc. Both the US and Israeli governments blame the Iranian-backed militia Kataib Hezbollah (KH) for the abduction.

KH was established in 2003 with the direct support of Iran’s IRGC, and is designated by the US as a terrorist organization. KH’s militia forms the largest part of Iraq’s national guard, known as the Popular Mobilization Forces, and KH politicians serve in Iraqi Prime Minister Shia Al Sudani’s government. US officials say KH also regularly coordinates with the IRGC to attack American military facilities and personnel in Iraq and the wider region. This includes a January drone strike on a Pentagon base in Jordan that killed three American troops.

The Trump administration assassinated KH’s founding commander, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, in a January 2020 missile strike on his convoy in Baghdad. He was accompanied by the IRGC’s most powerful general, Qasem Soleimani, who also died in the attack. Iran has vowed to avenge both of their deaths. KH hasn’t contacted the Tsurkov family nor made any demands for her release.

Elizabeth’s sister, Emma Tsurkov, has publicly criticized Princeton’s response to the kidnapping — mirroring, in many ways, complaints raised by Wang Xiyue. Last August, she penned an opinion piece in the New Jersey Star-Ledger claiming the school had been denying it approved Elizabeth’s travel to Iraq and was telling the State Department that their grad student had essentially gone rogue. Emma Tsurkov stressed in her article that any divide between the school and Elizabeth was extremely dangerous as it could only fuel charges that she was a spy and “hurt her chances of coming home.”

Emma told Semafor that Elizabeth, once in Iraq, was in regular contact with her Princeton thesis advisor, Professor Amaney Jamal, the dean of the School of Public and International Affairs. This included occasional video calls from Baghdad. But the Tsurkov family has been disappointed that Jamal hasn’t met with Emma in person since Elizabeth’s disappearance, something Princeton doesn’t dispute.

The school in October, for the first time, publicly took responsibility for Elizabeth’s research and travel to Iraq, even while raising questions about whether she followed proper procedures going there. Spokesman Hotchkiss told Semafor that Princeton is totally committed to gaining her release “by making available reputable outside experts the University has retained and by advocating with US government officials to use their influence to help bring Elizabeth home safely.”

He added that Jamal “directly communicated her deep concern for Elizabeth and her family to Emma Tsurkov” via email and that the school has appointed a deputy dean at the graduate school to serve as a point person. “[The administrator] is available for Emma at any time and remains in contact with her,” he said.

KH released a proof-of-life video in November in which a visibly exhausted Elizabeth Tsurkov reads a statement in Hebrew claiming she was both an operative for the CIA and Mossad, the Israeli spy agency. (The US and Israel deny this charge.) The student is believed to still be in Baghdad.

Emma Tsurkov is now focused on pressuring Iraq’s government to secure Elizabeth’s freedom, given Baghdad’s close ties to KH. The family believes Iraq should be designated as a state sponsor of terrorism and have its US aid budget slashed unless it wins Elizabeth’s release. Emma Tsurkov directly confronted the Iraqi prime minister at a Washington think tank last month on behalf of her sister, publicly accusing him of “not doing anything to save her.”

The Iraqi government hasn’t responded to requests for comment from Semafor.

An Iranian diplomat on campus

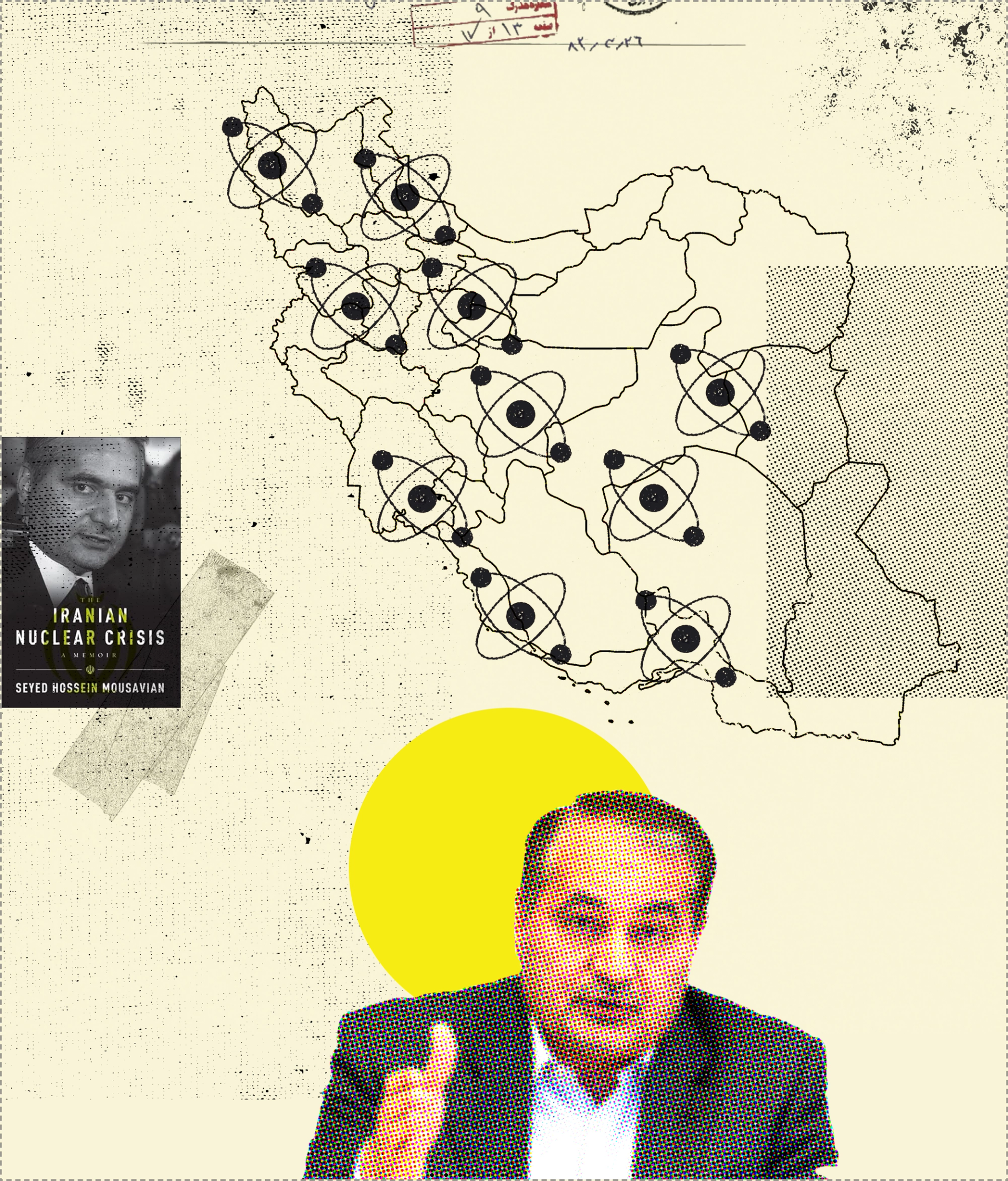

Princeton entered the Iran debate in a significant way in 2009, when it agreed to host Hossein Mousavian, a top regime diplomat and former nuclear negotiator, in New Jersey. Mousavian fled Tehran that year after being charged with espionage by then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s government, and briefly detained. The Islamic Republic insider would be cleared, but still found himself starkly on the wrong side of his country’s vicious political infighting.

Mousavian was no dissident, though, and used his perch at Princeton to advocate Iran’s positions on its nuclear program and other key national security issues. A former ambassador to Germany, Mousavian has supported ties with the West in ways that have placed him at odds with the IRGC and other hardline parties in Tehran. He has also sought to improve relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Many of Mousavian’s dictums on the nuclear file would be adopted by the Iranian government after his close political ally, Hassan Rouhani, succeeded Ahmadinejad as president in 2013 and moved to negotiate directly with the Obama administration over the next two years. The Princeton scholar was a prolific producer of opinion pieces and commentary during this period who liaised, at times, with Iranian diplomats, including Mostafa Zahrani and then-Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, to promote their messaging and engagements in the West, according to the foreign ministry correspondence reviewed by Semafor.

Princeton officials lauded Mousavian’s ability to advise the US and Iranian delegations to help advance the nuclear deal, which was finalized in July 2015. And in the eyes of Wang Xiyue, the graduate student, this reflected his school’s strong ties to the upper echelons of the Islamic Republic’s leadership. This sense of security was only bolstered, Wang told Semafor, by the fact that one of his advisers at Princeton’s Iran center, Mona Rahmani, was herself related to an Iranian government official. Her father ran Tehran’s interests section in Washington, an Iranian government body that works to support dual US-Iran citizens, from 2010-2015.

“My concerns were alleviated by the fact that there were these direct links between Princeton and Iran,” Wang said. “It looked like there was coordination.”

Following his arrest in August 2016, these connections to Tehran proved of little use, Wang outlined in a lawsuit he filed against Princeton in 2021, charging negligence. The university advised Wang’s wife to stay quiet and not publicly criticize the Iranian government, he says. And Mousavian told Princeton’s leadership that his outreach to Zahrani, Zarif, and other Iranian officials would be counterproductive for Wang, given the Princeton scholar’s own sparring with Tehran’s security state. Rahmani, meanwhile, also declined to lobby the regime, the lawsuit states. She left the university in 2017.

Wang says he felt totally abandoned during the more than three years he was incarcerated in Evin Prison. He was released on December 7, 2019 as part of a prisoner exchange negotiated between the Trump administration and Iran. “Simply put, after encouraging and convincing Mr. Wang to go to Iran, Princeton chose to put their reputation and political interest ahead of Mr. Wang’s personal safety,” reads his lawsuit.

Princeton denies that it placed its reputation or ties to Iran ahead of Wang’s safety. And the school said it invested enormous resources behind gaining his release. “Throughout his ordeal, the University worked in close coordination with his wife and provided extensive financial and other support to Mr. Wang and his family during and after his imprisonment,” Princeton’s legal team at Akin Gump wrote to congressional lawmakers investigating the school’s ties to Iran last year.

Princeton reached a financial settlement with Wang last September but denies all charges made against the school in the suit. “We have chosen to help them [Wang’s family] move on with their lives by avoiding protracted litigation,” spokesman Hotchkiss said.

Princeton officials strongly back the school’s decision to provide Mousavian a base to conduct his scholarship from 2009 through today. The school cites his role in helping to promote the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, and his efforts to reduce tensions between Washington and Tehran that some Western officials worry could expand into an all-out war. “Based on my personal observations, Dr. Mousavian, as an advisor to the negotiators on both sides, was as responsible as anyone for the creative ideas that bridged the gaps in the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Princeton Professor Emeritus Frank von Hippel, who helped bring Mousavian to Princeton, wrote in a 2022 opinion piece.

Mousavian has remained active in the Iran debate, including speaking last August at the Pentagon’s Strategic Command headquarters in Nebraska on the history of US-Iran relations — from Tehran’s perspective. Some Republican lawmakers were outraged that a former regime official — who maintains ties to Tehran — was invited to speak to such an important US military body. The House Committee on Education and the Workforce launched a formal probe last fall into Mousavian’s employment at Princeton, questioning whether he was operating as an unregistered foreign agent for Tehran. “Mousavian’s position ... raises significant concerns about the influence of foreign hostile regimes on American institutions,” the committee wrote to Princeton President Christopher Eisgruber last November.

Princeton, via Akin Gump, told the committee that Mousavian’s employment is compliant with US law and furthers the school’s educational mission, “including its commitment to scholarly excellence and academic freedom.” In March, the National Association of Scholars, a higher education membership organization and think tank, called for Princeton to dismiss Mousavian on the grounds that his position threatens US national security and “cedes academia’s integrity to a hostile regime linked to terrorism and human rights abuses.”

The school’s Iran center — formally known as the Sharmin and Bijan Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies — meanwhile, promotes scholarship that seeks to better understand the Islamic Republic. The center’s director, Professor Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi , has been outspoken while at Princeton in highlighting what he views as some of the Islamic Revolution’s accomplishments, including, the empowerment of women. In the fall of 2022, at the height of the Iranian government’s crackdown on women-led protests against the regime and laws that enforce Islamic head scarves, he wrote : “Despite all this, women’s social mobility and presence in [the] public sphere grew exponentially in the past four decades.”

Princeton also hosted Robert Malley, the Biden administration’s suspended special Iran envoy, as a guest lecturer for the 2023 fall semester. The State Department revoked Malley’s security clearance in March of last year, and he’s currently being investigated by the FBI for the possible mishandling of classified information. He’s been one of the strongest proponents in Washington for engaging the Iranian regime.

The desire for stronger academic ties during the mid-2010s was a two-way street. Throughout former President Barack Obama’s tenure, Tehran communicated to Washington a desire to increase the numbers of Iranians at elite American universities, according to current and former US officials. The formalizing of the 2015 nuclear agreement was seen as a way to accelerate this process.

“As I mentioned to you in Vienna, we are also considering sending a few of our scholars and researchers to your university. A Ph.D. course is what we had in mind,” Mostafa Zahrani wrote to Kevan Harris of Princeton’s Iran center, in November 2014. “I would appreciate [it] if you give details on if and how this would be possible or information on any other program you had in mind.”

Wang Xiyue’s imprisonment two years later appeared to be a deliberate attempt by the IRGC, and other hardline elements of the regime, to sabotage academic or business engagement with the US, according to American and European officials. Iran’s security forces imprisoned a prominent Iranian-American businessman, Siamak Namazi, three months after the finalizing of the nuclear deal in July 2015, and held him for eight years until his 2023 release. This placed a significant chill on the willingness of diaspora Iranians to travel to Iran and attempt to conduct business. Wang and Namazi were both charged with being Western spies.

Attempts by Semafor to reach Zahrani and other Iranian officials about the student exchange program were unsuccessful. Ariane Tabatabai, who first put Zahrani in touch with Princeton while she was working at Harvard University, “played no part in a separate institution’s student exchange,” a person close to her work told Semafor.

KH, the Iranian proxy force in Iraq, has also couched the abduction of Elizabeth Tsurkov as part of its broader battle against the US and Israel — though its statements appear aimed at distancing itself from the actual kidnapping. “We in the victorious Kataib Hezbollah, in turn, will increase our efforts to find out the fate of the Zionist prisoner or prisoners in Iraq,” KH security chief, Abu Ali Al-Askari, said about the Tsurkov kidnapping in a statement released last July on Iraqi television. “[We will] learn more about the intentions of this criminal gang, and who facilitates their movements in a country that prohibits and criminalizes dealing with them.”

The KH chief appears to be referring to the Israeli government.

The story of Mousavian’s exile in New Jersey is one for which I’ve had a front row seat. I was the first journalist to interview the Iranian diplomat and scholar following his quiet arrival at Princeton in 2009. And his saga speaks to what’s been a decades-long effort — pursued by both the US government and private American institutions — to identify and engage moderates in revolutionary Iran.

Obama administration and European officials flocked to meet Mousavian, and closely scrutinized his writings, once he was ensconced in the US. Mousavian was clear to me and others at that time that he wasn’t seeking asylum and planned to return to Iran. From his modest office at Princeton, he pumped out books and papers that helped serve as building blocks for what would be the landmark 2015 nuclear deal. Some Western officials told me that they saw Mousavian as serving as a critical interlocutor if he joined a future Iranian government.

I thought Mousavian would serve as a senior official in President Rouhani’s government, which took power in 2013. But the diplomat never left Princeton. He’s publicly said that he remains barred from government service. And he’s privately told people that he runs the risk of arrest by the IRGC and other hardline factions if he travels to Iran.

Mousavian’s status raises serious questions about whether Iranian officials, courted by the West, can really survive in Iran’s authoritarian and Islamist system. Supporters of the Obama administration’s nuclear policy point out — correctly — that it was the US under Donald Trump who pulled the plug on the nuclear accord. But it’s also true that most of the constraints placed on Tehran were going to expire. And even Mousavian, in his writings, acknowledges that he’s not sure what the IRGC’s long-term plans for the nuclear program might entail.

“I hold to the assessment that Iran has not made a decision to acquire a nuclear weapon as distinguished from a nuclear weapons option,” he wrote in his 2012 book: The Iranian Nuclear Crisis: A Memoir . Mousavian has recently voiced his concern that the current tensions in the Middle East involving Iran, Israel, and the US are only increasing the chances that Tehran will seek to develop nuclear weapons.

Princeton’s efforts to establish a student-exchange program were also derailed by Tehran’s political warfare. Correspondence reviewed by Semafor details the optimism Princeton officials held for academic exchanges with Tehran just weeks before Wang’s arrest. They clearly didn’t seem to appreciate that there were forces inside Iran eager to maintain the country’s hostility towards the US.

“What the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran did to Xiyue Wang and his family is outrageous, unjust, and alarming for researchers and academics around the world,” Harris, the former Princeton postdoctoral researcher who worked on student exchanges, told me. He left in the summer of 2015 for UCLA where he currently works as an associate professor of sociology. “No one in an academic institution should be subject to such treatment by Iran’s government, whether they are a citizen of Iran or a foreigner.”

- An organization of Iranian exiles — called the Alliance Against Islamic Regime of Iran Apologists — has been staging events and protests calling for Mousavian’s dismissal, including at Princeton. Some of the protesters are relatives of Kurdish dissidents assassinated by the Iranian regime in Berlin in 1992, when Mousavian served as Tehran’s ambassador to Germany. AAIRIA accuses Mousavian of being complicit in the terrorist attack, which he denies.

- Elizabeth Tsurkov’s writings on the Middle East have also focused on Jewish settler violence against Palestinians and Israeli Arabs. Her June 2021 piece in New Lines Magazine documents how Jewish militias have moved their operations into Israel proper from the West Bank.

- Current and former IRGC generals have spoken in recent weeks of revising the country’s nuclear doctrine , which Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has ruled explicitly forbids the development of atomic weapons. “If the Zionist regime wants to use the threat of attacking our country’s nuclear centers as a tool to pressure Iran, it is possible to review the nuclear doctrine,” Gen. Ahmad Haqtalab said on April 18.

- Top Republicans investigating the suspension of the Biden administration’s Iran envoy, Robert Malley, said they uncovered evidence that the diplomat sent classified documents to his personal devices , and may have been hacked by a foreign power. The lawmakers’ conclusions were documented in a letter sent to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on May 6 — which was obtained by The Washington Post — and laid out 19 questions on the matter. The State Department declined to answer media requests for comment.

2024 Young Alumni Trustee General Election Candidates

Below are the candidates for the 2024 Young Alumni Trustee election, in alphabetical order: Aisha Chebbi, Sydney S. Johnson and Chioma Ugwonali.

Candidates have agreed that they will not engage in any organized solicitation of votes during this primary election, nor will they ask any other student or organization to do so.

Disclaimer The role of a Young Alumni Trustee is to serve the long-term interests of the University as a member of the board, bringing to the role an important perspective informed by their recent experience as an undergraduate student. It is not to represent or advocate for a particular constituency or point of view. The views, information and opinions expressed by the candidates in their statements are solely their own. Further, the University does not undertake to verify or ensure the accuracy of the candidates’ statements.

Aisha Chebbi Miami, FL, USA Major(s): Anthropology; Certificate(s): Global Health and Health Policy

For Aisha Chebbi ’24, fostering dialogue across difference has been at the center of her commitment to service at Princeton, and it motivates her as a Young Alumni Trustee candidate.

“The majority of my service to Princeton’s undergraduate body has been centered on bringing together student voices from different communities, particularly those that would otherwise fall along lines of marginalization, to engage in productive, action-driven discourse,” said Chebbi. “I see this as not just an act of speaking up for students for the long term, but also of finding tangible ways to improve everyone’s experiences in the present moment.”

A medical anthropology major whose certificate will be in global health policy, Chebbi is from Miami, Florida, and has worked on behalf of health and wellness both on campus and beyond. She also has held leadership positions across many student and service organizations, and her interests include cultural affinity organizing and advocacy, student mentorship, podcasting and interfaith dialogue.

As co-president of the Muslim Students Association (MSA), Chebbi collaborated with campus administrators and Dining Services to initiate new programming for the month of Ramadan, including streamlined meal pickup and consistent prayer spaces. The MSA also organized nightly prayer services and dinner distribution every day for the month of Ramadan and arranged programming for Eid. As a residential college adviser at Yeh College, Chebbi counseled first-year students, organized weekly study breaks and promoted college-wide events.

Other activities include co-coordinating the Partners in Health Engage, which involved organizing campus-wide events to create awareness of global health issues; serving as student representative to the Global Health Program Advisory Committee; representing first-years on Class Council of the Undergraduate Student Government; chairing the Princeton Arab Society; serving as a fellow at the Carl A. Fields Center for Equality and Cultural Understanding and as a Community Action Orientation leader with the Pace Center for Civic Engagement.

“The coalescing of diverse student voices, University administration and alumni experience is an element of my leadership style that equips me well to tackle the difficult questions that being a Young Alumni Trustee poses,” Chebbi said.

Beyond campus, Chebbi completed an internship at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance in Geneva, Switzerland. She also created, organized, and led a trip to Havana, Cuba, through the Office of Religious Life. An avid podcaster, Chebbi created a personal podcast delving into questions of identity and belonging and has hosted another podcast highlighting inspiring career stories.

After graduation, Chebbi will pursue a study/research award in Germany as a Fulbright Scholar. This research will expand on her thesis work, which seeks to understand vaccine hesitancy in minoritized religious communities. Ultimately, she intends to pursue a career as a pediatric physician with an emphasis on global health in a role where she can directly serve patients, while also playing a formative role in shaping the policy that removes barriers to accessing health care.

Sydney S. Johnson Piscataway, NJ, USA Major(s): Spanish - Creative Arts; Certificate(s): Urban and Latin American Studies

Sydney Johnson ’24 would use her term as Young Alumni Trustee to continue learning, leading and supporting others in order to improve the University experience.

“I am running for Young Alumni Trustee to continue learning from and supporting others within the Princeton Community, while bringing a diverse perspective to all conversations concerning the development of the University,” Johnson said.

Johnson is a Spanish and creative arts major from Piscataway, New Jersey, who has served as a class government officer all four years at Princeton. As the senior class president, she leads the Senior Commencement Committee, coordinates multimedia communications with more than a thousand students, facilitates alumni outreach and oversees the Class Day and Commencement Fair/Senior Checkout committees.

“During my time as a class officer, especially in the past three years as class president, I have cultivated the necessary skills to understand and represent the needs of various demographics within a larger collective, as well as the ability to directly communicate with University administration, alumni and students,” she said.

Through mentoring first-year students via the Princeton University Mentoring Program, assisting with the Orientation Welcome Committee and serving as a residential college adviser, Johnson noted she has developed a “deep understanding and respect for the needs of incoming Tigers as they become acclimated to our campus.” These peer-to-peer roles, she said, also enhanced her knowledge of campus resources, student health and wellness needs, and the impact of the residential college system.

Johnson also served on both the Priorities and University Accreditation committees, the former helping her understand Princeton’s working structure and operating budget and allowing her to make suggestions for key focal points in the coming years. On the Middle States Accreditation Committee, she had the opportunity to speak to student experiences with large and small departments, technology, pathways into or away from majors, and practical concerns around space and resources amidst the University’s expansion. She also served on the Class Affairs Committee of the Alumni Council Executive Committee, learning about alumni engagement and governance as a representative of the student body.

Active in women’s club volleyball and passionate about the entertainment industry, Johnson served on the Sport Club executive board and founded the undergraduate chapter of Princeton in Hollywood. “Founding a student organization this past year has demonstrated my capacity to identify key points for growth and petition existing structures to support new initiatives,” she said. “Since the fall, we have educated undergraduates and graduates interested in the entertainment industry via conversations with alumni, educational resources and speaker events, like the screening and talkback with filmmaker Barry Jenkins.”

After graduation, Johnson will move to Los Angeles to work as an executive assistant at Peter Rice Productions, a film and TV company that collaborates with A24 and across Hollywood.

Chioma Ugwonali Arlington, TX, USA Major(s): Ecology and Evolutionary Biology; Certificate(s): Environmental Studies

As a candidate for Young Alumni Trustee, Chioma Ugwonali ’24 is committed to reinforcing the University’s values of service and belonging.

“Service is inherently generous, communal and healing,” said Ugwonali, who is from Arlington, Texas. “Countless people and places have poured love, encouragement and guidance into me that have shaped who I am today. I have tried to do the same for those around me, at Princeton and otherwise, and would love to continue to do so for the University at large.”

A major in ecology and evolutionary biology, Ugwonali has promoted student well-being, serving as head of the Butler College Council’s Civic Engagement Committee and co-launching the Peer Health Advisers’ (PHA) Wellness Is Worth It Initiative, part of the TigerWell Initiative. The wellness initiative included Wellness Chats, a Wellness Partnership Luncheon and a series of Mental Wellness 101 workshops.

Ugwonali served as PHA’s head of external relations, bolstering partnerships between the student volunteer group and the Princeton University Library, Campus Recreation, Campus Dining and the Undergraduate Student Government Mental Health Committee. During her junior and senior years, she was a residential college adviser for Butler College. She was also one of the inaugural recipients of the Emerging Peer Leader of the Year award granted by the Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Students.

“My first year at Princeton being virtual reminded me that nothing in life is guaranteed and that there is so much to be grateful for,” said Ugwonali. “I endeavored to make each day count.” That approach led her to collaborate with a group of fellow community members to bring the “Telephone of the Wind” to campus, an interactive art exhibit incorporating a rotary phone used to “call” someone they love who has passed away, is incarcerated, lost or otherwise distant.

In her senior year, she coordinated the arts programs for the inaugural Community Care Day, worked as a student fellow for the Office of Campus Engagement and served on committees such as the TigerWell Grant Selection Committee, University Mental Health Taskforce and the Student Health Advisory Board.

Beyond campus, her focus on social justice and the environment led her to organize Roots Community Cookout, a mutual aid cookout for individuals in need in Fort Worth, Texas. Following this, Ugwonali organized Roots Collective, an event including an environmental justice workshop for high schoolers, urban agricultural tours and a public wellness festival amplifying the efforts of local environmental justice and well-being advocates.

“I have embraced a plethora of learning opportunities Princeton has to offer outside of the classroom and have built many meaningful relationships along the way,” Ugwonali said. “It is never too late to reimagine one’s Princeton experience and how we go on to engage with the world.”

Following graduation, she plans to apply to medical school while working as a community health program coordinator; she will also volunteer at local community gardens and environmental justice organizations.

Copyright © 2023 The Trustees of Princeton University

IMAGES

COMMENTS

At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project. ... others fashion their topics on the basis of long-standing personal passions. Most thesis writers encounter the intellectual twists and turns of any good research project, where the questions emerge as ...

For many alumni, their year-long senior thesis is the most rewarding academic exercise of their years at Princeton. This guide represents an effort to better inform students of what to expect when writing a thesis. It provides key dates, deadlines,

The Thesis Central website portal opens for submissions beginning on March 25, 2024. Class of 2024 Senior Thesis Timeline. Thesis Central open to submissions March 25, 2024. Last day for students to submit to Thesis Central is May 7, 2024 (Dean's Date) Review and approvals must be complete by June 24, 2024

Submit thesis prospectus (title and 1-page description) to senior thesis adviser, DUS, and UPA via email. November 20 (Monday) Submit an outline of thesis and a full working bibliography to adviser, DUS, and UPA. By January 26 (Friday) Submit partial first draft (of at least 20 pages) to adviser on or before this date. March 8 (Friday)

Senior Thesis Deadlines. Thesis Proposal Form Due Thursday, September 21, 2023. You must submit your thesis proposal form, signed by your advisor, via email to [email protected] by 12pm (noon).. First Semester Progress Report Due Monday, December 4, 2023. You must submit your first-semester progress report to your advisor and to [email protected] by 12pm (noon).

Thesis Central will be available for student submissions starting in March 25th, 2024 thru the 2024 Dean's date, May 7th, 2024. To access the site, go to the Princeton Thesis Central homepage and login with your netid. Allow roughly 20 minutes to complete the upload process. Note: be sure to check with your home department for additional ...

Bound Ph.D. Dissertations in the Mudd Manuscript Library stacks. The Princeton University Archives located within the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library is the official repository for Undergraduate Senior Theses, Master's Theses and Ph.D. Dissertations. Princeton University undergraduate senior theses range from 1924 to the present.

Princeton University Library One Washington Road Princeton, NJ 08544-2098 USA (609) 258-1470

The senior thesis is the report of a student's independent research project. Whether based in the laboratory or not, the thesis should demonstrate a solid knowledge of molecular biology and of the problem under analysis. It should move logically from this background to one or more clearly articulated, testable hypotheses. Most students elect to ...

This senior thesis guide applies to all CEE students who are satisfying the senior thesis requirement by signing up for CEE 478The Senior Thesis, CEE 478, is a year. -long research project and is considered by many Princeton graduates to be one of the most fulfilling academic activities of their four years. The thesis process requires independent

Use This Database. List of theses starting in 1926 written by seniors at Princeton University. Not all departments are represented. Princeton University network connected patrons may view most 2014 to current theses.

Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2023. Members of the Princeton community wishing to view a senior thesis from 2014 and later while away from campus should follow the instructions outlined on the OIT website for connecting to campus resources remotely. Communities.

The PAW article on the history of the senior thesis (May issue) included a photo of Edward T. Cone '39 and the information that his was the first work submitted as a "creative thesis." This brought back quite a few memories for me. Ed Cone was my mother's distant cousin and probably the most compelling reason for my attending Princeton ...

Thesis Trauma and a Recurring Nightmare. By David G. Robinson '67. Published online May 9, 2024. 0. SEND A RESPONSE TO INBOX. In Response to: The Senior Thesis at 100: Back to the Future. The recent PAW thesis piece honors the glories of the senior thesis, but doesn't spend much time on the agonies. As a Nassoon, I spent year after year ...

May 10 2024. By Brittany N. Murray. Source Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. Share. My great-grandmother was one of the first female candidates for vice president in Latin America and navigated the perilous waters of politics and activism during a time of brutal political oppression. Driven by a deep-seated commitment to ...

Students and instructors in LAS 302/ HIS 305 The Long 1960s in Latin America: ... Senior Thesis Titles; Senior Thesis Prizes; Undergraduate Certificate Submenu. ... 323-338 Aaron Burr Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544 [email protected] (609) 258-4148. Digital Accessibility

Students abducted. Princeton's student exchange program first took off in 2014, when a prominent Iranian-American scholar and future Biden administration official, Ariane Tabatabai, connected the Iran center's then-associate director to Mostafa Zahrani, a senior Iranian foreign ministry diplomat with strong ties to his country's elite military force, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps ...

This senior thesis guide applies to all CEE students who are satisfying the senior thesis requirement by signing up for CEE 478. Senior thesis can be co-advised by several faculty from CEE or out of CEE; however, at least one faculty from CEE must be co-advisor. Students in the "Architecture and Engineering - Architecture Focus" track are ...

Below are the candidates for the 2024 Young Alumni Trustee election, in alphabetical order: Aisha Chebbi, Sydney S. Johnson and Chioma Ugwonali. Candidates have agreed that they will not engage in any organized solicitation of votes during this primary election, nor will they ask any other student or organization to do so.

Thesis: Theory of Topological Phenomena in Condensed Matter Systems ... (Senior Specialist at FINMA) Ying Ran (Associate Professor, Boston College) ... Nishimori's cat: stable long-range entanglement from finite-depth unitaries and weak measurements Physical Review Letters 131 (20), 200201, 30 (2023). ...