Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Assessing the impact of healthcare research: A systematic review of methodological frameworks

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Centre for Patient Reported Outcomes Research, Institute of Applied Health Research, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

- Samantha Cruz Rivera,

- Derek G. Kyte,

- Olalekan Lee Aiyegbusi,

- Thomas J. Keeley,

- Melanie J. Calvert

- Published: August 9, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370

- Reader Comments

Increasingly, researchers need to demonstrate the impact of their research to their sponsors, funders, and fellow academics. However, the most appropriate way of measuring the impact of healthcare research is subject to debate. We aimed to identify the existing methodological frameworks used to measure healthcare research impact and to summarise the common themes and metrics in an impact matrix.

Methods and findings

Two independent investigators systematically searched the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), the Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL+), the Health Management Information Consortium, and the Journal of Research Evaluation from inception until May 2017 for publications that presented a methodological framework for research impact. We then summarised the common concepts and themes across methodological frameworks and identified the metrics used to evaluate differing forms of impact. Twenty-four unique methodological frameworks were identified, addressing 5 broad categories of impact: (1) ‘primary research-related impact’, (2) ‘influence on policy making’, (3) ‘health and health systems impact’, (4) ‘health-related and societal impact’, and (5) ‘broader economic impact’. These categories were subdivided into 16 common impact subgroups. Authors of the included publications proposed 80 different metrics aimed at measuring impact in these areas. The main limitation of the study was the potential exclusion of relevant articles, as a consequence of the poor indexing of the databases searched.

Conclusions

The measurement of research impact is an essential exercise to help direct the allocation of limited research resources, to maximise research benefit, and to help minimise research waste. This review provides a collective summary of existing methodological frameworks for research impact, which funders may use to inform the measurement of research impact and researchers may use to inform study design decisions aimed at maximising the short-, medium-, and long-term impact of their research.

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- There is a growing interest in demonstrating the impact of research in order to minimise research waste, allocate resources efficiently, and maximise the benefit of research. However, there is no consensus on which is the most appropriate tool to measure the impact of research.

- To our knowledge, this review is the first to synthesise existing methodological frameworks for healthcare research impact, and the associated impact metrics by which various authors have proposed impact should be measured, into a unified matrix.

What did the researchers do and find?

- We conducted a systematic review identifying 24 existing methodological research impact frameworks.

- We scrutinised the sample, identifying and summarising 5 proposed impact categories, 16 impact subcategories, and over 80 metrics into an impact matrix and methodological framework.

What do these findings mean?

- This simplified consolidated methodological framework will help researchers to understand how a research study may give rise to differing forms of impact, as well as in what ways and at which time points these potential impacts might be measured.

- Incorporating these insights into the design of a study could enhance impact, optimizing the use of research resources.

Citation: Cruz Rivera S, Kyte DG, Aiyegbusi OL, Keeley TJ, Calvert MJ (2017) Assessing the impact of healthcare research: A systematic review of methodological frameworks. PLoS Med 14(8): e1002370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370

Academic Editor: Mike Clarke, Queens University Belfast, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: February 28, 2017; Accepted: July 7, 2017; Published: August 9, 2017

Copyright: © 2017 Cruz Rivera et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and supporting files.

Funding: Funding was received from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript ( http://www.conacyt.mx/ ).

Competing interests: I have read the journal's policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: MJC has received consultancy fees from Astellas and Ferring pharma and travel fees from the European Society of Cardiology outside the submitted work. TJK is in full-time paid employment for PAREXEL International.

Abbreviations: AIHS, Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions; CAHS, Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; CIHR, Canadian Institutes of Health Research; CINAHL+, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; EMBASE, Excerpta Medica Database; ERA, Excellence in Research for Australia; HEFCE, Higher Education Funding Council for England; HMIC, Health Management Information Consortium; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; IOM, Impact Oriented Monitoring; MDG, Millennium Development Goal; NHS, National Health Service; MEDLINE, Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; PHC RIS, Primary Health Care Research & Information Service; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PROM, patient-reported outcome measures; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; R&D, research and development; RAE, Research Assessment Exercise; REF, Research Excellence Framework; RIF, Research Impact Framework; RQF, Research Quality Framework; SDG, Sustainable Development Goal; SIAMPI, Social Impact Assessment Methods for research and funding instruments through the study of Productive Interactions between science and society

Introduction

In 2010, approximately US$240 billion was invested in healthcare research worldwide [ 1 ]. Such research is utilised by policy makers, healthcare providers, and clinicians to make important evidence-based decisions aimed at maximising patient benefit, whilst ensuring that limited healthcare resources are used as efficiently as possible to facilitate effective and sustainable service delivery. It is therefore essential that this research is of high quality and that it is impactful—i.e., it delivers demonstrable benefits to society and the wider economy whilst minimising research waste [ 1 , 2 ]. Research impact can be defined as ‘any identifiable ‘benefit to, or positive influence on the economy, society, public policy or services, health, the environment, quality of life or academia’ (p. 26) [ 3 ].

There are many purported benefits associated with the measurement of research impact, including the ability to (1) assess the quality of the research and its subsequent benefits to society; (2) inform and influence optimal policy and funding allocation; (3) demonstrate accountability, the value of research in terms of efficiency and effectiveness to the government, stakeholders, and society; and (4) maximise impact through better understanding the concept and pathways to impact [ 4 – 7 ].

Measuring and monitoring the impact of healthcare research has become increasingly common in the United Kingdom [ 5 ], Australia [ 5 ], and Canada [ 8 ], as governments, organisations, and higher education institutions seek a framework to allocate funds to projects that are more likely to bring the most benefit to society and the economy [ 5 ]. For example, in the UK, the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF) has recently been used to assess the quality and impact of research in higher education institutions, through the assessment of impact cases studies and selected qualitative impact metrics [ 9 ]. This is the first initiative to allocate research funding based on the economic, societal, and cultural impact of research, although it should be noted that research impact only drives a proportion of this allocation (approximately 20%) [ 9 ].

In the UK REF, the measurement of research impact is seen as increasingly important. However, the impact element of the REF has been criticised in some quarters [ 10 , 11 ]. Critics deride the fact that REF impact is determined in a relatively simplistic way, utilising researcher-generated case studies, which commonly attempt to link a particular research outcome to an associated policy or health improvement despite the fact that the wider literature highlights great diversity in the way research impact may be demonstrated [ 12 , 13 ]. This led to the current debate about the optimal method of measuring impact in the future REF [ 10 , 14 ]. The Stern review suggested that research impact should not only focus on socioeconomic impact but should also include impact on government policy, public engagement, academic impacts outside the field, and teaching to showcase interdisciplinary collaborative impact [ 10 , 11 ]. The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) has recently set out the proposals for the REF 2021 exercise, confirming that the measurement of such impact will continue to form an important part of the process [ 15 ].

With increasing pressure for healthcare research to lead to demonstrable health, economic, and societal impact, there is a need for researchers to understand existing methodological impact frameworks and the means by which impact may be quantified (i.e., impact metrics; see Box 1 , 'Definitions’) to better inform research activities and funding decisions. From a researcher’s perspective, understanding the optimal pathways to impact can help inform study design aimed at maximising the impact of the project. At the same time, funders need to understand which aspects of impact they should focus on when allocating awards so they can make the most of their investment and bring the greatest benefit to patients and society [ 2 , 4 , 5 , 16 , 17 ].

Box 1. Definitions

- Research impact: ‘any identifiable benefit to, or positive influence on, the economy, society, public policy or services, health, the environment, quality of life, or academia’ (p. 26) [ 3 ].

- Methodological framework: ‘a body of methods, rules and postulates employed by a particular procedure or set of procedures (i.e., framework characteristics and development)’ [ 18 ].

- Pathway: ‘a way of achieving a specified result; a course of action’ [ 19 ].

- Quantitative metrics: ‘a system or standard of [quantitative] measurement’ [ 20 ].

- Narrative metrics: ‘a spoken or written account of connected events; a story’ [ 21 ].

Whilst previous researchers have summarised existing methodological frameworks and impact case studies [ 4 , 22 – 27 ], they have not summarised the metrics for use by researchers, funders, and policy makers. The aim of this review was therefore to (1) identify the methodological frameworks used to measure healthcare research impact using systematic methods, (2) summarise common impact themes and metrics in an impact matrix, and (3) provide a simplified consolidated resource for use by funders, researchers, and policy makers.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Initially, a search strategy was developed to identify the available literature regarding the different methods to measure research impact. The following keywords: ‘Impact’, ‘Framework’, and ‘Research’, and their synonyms, were used during the search of the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE; Ovid) database, the Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) database, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL+) database (inception to May 2017; see S1 Appendix for the full search strategy). Additionally, the nonindexed Journal of Research Evaluation was hand searched during the same timeframe using the keyword ‘Impact’. Other relevant articles were identified through 3 Internet search engines (Google, Google Scholar, and Google Images) using the keywords ‘Impact’, ‘Framework’, and ‘Research’, with the first 50 results screened. Google Images was searched because different methodological frameworks are summarised in a single image and can easily be identified through this search engine. Finally, additional publications were sought through communication with experts.

Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see S1 PRISMA Checklist ), 2 independent investigators systematically screened for publications describing, evaluating, or utilising a methodological research impact framework within the context of healthcare research [ 28 ]. Papers were eligible if they included full or partial methodological frameworks or pathways to research impact; both primary research and systematic reviews fitting these criteria were included. We included any methodological framework identified (original or modified versions) at the point of first occurrence. In addition, methodological frameworks were included if they were applicable to the healthcare discipline with no need of modification within their structure. We defined ‘methodological framework’ as ‘a body of methods, rules and postulates employed by a particular procedure or set of procedures (i.e., framework characteristics and development)’ [ 18 ], whereas we defined ‘pathway’ as ‘a way of achieving a specified result; a course of action’ [ 19 ]. Studies were excluded if they presented an existing (unmodified) methodological framework previously available elsewhere, did not explicitly describe a methodological framework but rather focused on a single metric (e.g., bibliometric analysis), focused on the impact or effectiveness of interventions rather than that of the research, or presented case study data only. There were no language restrictions.

Data screening

Records were downloaded into Endnote (version X7.3.1), and duplicates were removed. Two independent investigators (SCR and OLA) conducted all screening following a pilot aimed at refining the process. The records were screened by title and abstract before full-text articles of potentially eligible publications were retrieved for evaluation. A full-text screening identified the publications included for data extraction. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with the involvement of a third reviewer (MJC, DGK, and TJK) when necessary.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction occurred after the final selection of included articles. SCR and OLA independently extracted details of impact methodological frameworks, the country of origin, and the year of publication, as well as the source, the framework description, and the methodology used to develop the framework. Information regarding the methodology used to develop each methodological framework was also extracted from framework webpages where available. Investigators also extracted details regarding each framework’s impact categories and subgroups, along with their proposed time to impact (‘short-term’, ‘mid-term’, or ‘long-term’) and the details of any metrics that had been proposed to measure impact, which are depicted in an impact matrix. The structure of the matrix was informed by the work of M. Buxton and S. Hanney [ 2 ], P. Buykx et al. [ 5 ], S. Kuruvila et al. [ 29 ], and A. Weiss [ 30 ], with the intention of mapping metrics presented in previous methodological frameworks in a concise way. A consensus meeting with MJC, DGK, and TJK was held to solve disagreements and finalise the data extraction process.

Included studies

Our original search strategy identified 359 citations from MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE, CINAHL+, HMIC, and the Journal of Research Evaluation, and 101 citations were returned using other sources (Google, Google Images, Google Scholar, and expert communication) (see Fig 1 ) [ 28 ]. In total, we retrieved 54 full-text articles for review. At this stage, 39 articles were excluded, as they did not propose new or modified methodological frameworks. An additional 15 articles were included following the backward and forward citation method. A total of 31 relevant articles were included in the final analysis, of which 24 were articles presenting unique frameworks and the remaining 7 were systematic reviews [ 4 , 22 – 27 ]. The search strategy was rerun on 15 May 2017. A further 19 publications were screened, and 2 were taken forward to full-text screening but were ineligible for inclusion.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370.g001

Methodological framework characteristics

The characteristics of the 24 included methodological frameworks are summarised in Table 1 , 'Methodological framework characteristics’. Fourteen publications proposed academic-orientated frameworks, which focused on measuring academic, societal, economic, and cultural impact using narrative and quantitative metrics [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 8 , 29 , 31 – 39 ]. Five publications focused on assessing the impact of research by focusing on the interaction process between stakeholders and researchers (‘productive interactions’), which is a requirement to achieve research impact. This approach tries to address the issue of attributing research impact to metrics [ 7 , 40 – 43 ]. Two frameworks focused on the importance of partnerships between researchers and policy makers, as a core element to accomplish research impact [ 44 , 45 ]. An additional 2 frameworks focused on evaluating the pathways to impact, i.e., linking processes between research and impact [ 30 , 46 ]. One framework assessed the ability of health technology to influence efficiency of healthcare systems [ 47 ]. Eight frameworks were developed in the UK [ 2 , 3 , 29 , 37 , 39 , 42 , 43 , 45 ], 6 in Canada [ 8 , 33 , 34 , 44 , 46 , 47 ], 4 in Australia [ 5 , 31 , 35 , 38 ], 3 in the Netherlands [ 7 , 40 , 41 ], and 2 in the United States [ 30 , 36 ], with 1 model developed with input from various countries [ 32 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370.t001

Methodological framework development

The included methodological frameworks varied in their development process, but there were some common approaches employed. Most included a literature review [ 2 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 – 46 ], although none of them used a recognised systematic method. Most also consulted with various stakeholders [ 3 , 8 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 35 – 38 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 47 ] but used differing methods to incorporate their views, including quantitative surveys [ 32 , 35 , 43 , 46 ], face-to-face interviews [ 7 , 29 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 42 , 43 ], telephone interviews [ 31 , 46 ], consultation [ 3 , 7 , 36 ], and focus groups [ 39 , 43 ]. A range of stakeholder groups were approached across the sample, including principal investigators [ 7 , 29 , 43 ], research end users [ 7 , 42 , 43 ], academics [ 3 , 8 , 39 , 40 , 43 , 46 ], award holders [ 43 ], experts [ 33 , 38 , 39 ], sponsors [ 33 , 39 ], project coordinators [ 32 , 42 ], and chief investigators [ 31 , 35 ]. However, some authors failed to identify the stakeholders involved in the development of their frameworks [ 2 , 5 , 34 , 41 , 45 ], making it difficult to assess their appropriateness. In addition, only 4 of the included papers reported using formal analytic methods to interpret stakeholder responses. These included the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences framework, which used conceptual cluster analysis [ 33 ]. The Research Contribution [ 42 ], Research Impact [ 29 ], and Primary Health Care & Information Service [ 31 ] used a thematic analysis approach. Finally, some authors went on to pilot their framework, which shaped refinements on the methodological frameworks until approval. Methods used to pilot the frameworks included a case study approach [ 2 , 3 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 40 , 42 , 44 , 45 ], contrasting results against available literature [ 29 ], the use of stakeholders’ feedback [ 7 ], and assessment tools [ 35 , 46 ].

Major impact categories

1. primary research-related impact..

A number of methodological frameworks advocated the evaluation of ‘research-related impact’. This encompassed content related to the generation of new knowledge, knowledge dissemination, capacity building, training, leadership, and the development of research networks. These outcomes were considered the direct or primary impacts of a research project, as these are often the first evidenced returns [ 30 , 62 ].

A number of subgroups were identified within this category, with frameworks supporting the collection of impact data across the following constructs: ‘research and innovation outcomes’; ‘dissemination and knowledge transfer’; ‘capacity building, training, and leadership’; and ‘academic collaborations, research networks, and data sharing’.

1 . 1 . Research and innovation outcomes . Twenty of the 24 frameworks advocated the evaluation of ‘research and innovation outcomes’ [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 29 – 39 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 46 ]. This subgroup included the following metrics: number of publications; number of peer-reviewed articles (including journal impact factor); citation rates; requests for reprints, number of reviews, and meta-analysis; and new or changes in existing products (interventions or technology), patents, and research. Additionally, some frameworks also sought to gather information regarding ‘methods/methodological contributions’. These advocated the collection of systematic reviews and appraisals in order to identify gaps in knowledge and determine whether the knowledge generated had been assessed before being put into practice [ 29 ].

1 . 2 . Dissemination and knowledge transfer . Nineteen of the 24 frameworks advocated the assessment of ‘dissemination and knowledge transfer’ [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 7 , 29 – 32 , 34 – 43 , 46 ]. This comprised collection of the following information: number of conferences, seminars, workshops, and presentations; teaching output (i.e., number of lectures given to disseminate the research findings); number of reads for published articles; article download rate and number of journal webpage visits; and citations rates in nonjournal media such as newspapers and mass and social media (i.e., Twitter and blogs). Furthermore, this impact subgroup considered the measurement of research uptake and translatability and the adoption of research findings in technological and clinical applications and by different fields. These can be measured through patents, clinical trials, and partnerships between industry and business, government and nongovernmental organisations, and university research units and researchers [ 29 ].

1 . 3 . Capacity building , training , and leadership . Fourteen of 24 frameworks suggested the evaluation of ‘capacity building, training, and leadership’ [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 8 , 29 , 31 – 35 , 39 – 41 , 43 ]. This involved collecting information regarding the number of doctoral and postdoctoral studentships (including those generated as a result of the research findings and those appointed to conduct the research), as well as the number of researchers and research-related staff involved in the research projects. In addition, authors advocated the collection of ‘leadership’ metrics, including the number of research projects managed and coordinated and the membership of boards and funding bodies, journal editorial boards, and advisory committees [ 29 ]. Additional metrics in this category included public recognition (number of fellowships and awards for significant research achievements), academic career advancement, and subsequent grants received. Lastly, the impact metric ‘research system management’ comprised the collection of information that can lead to preserving the health of the population, such as modifying research priorities, resource allocation strategies, and linking health research to other disciplines to maximise benefits [ 29 ].

1 . 4 . Academic collaborations , research networks , and data sharing . Lastly, 10 of the 24 frameworks advocated the collection of impact data regarding ‘academic collaborations (internal and external collaborations to complete a research project), research networks, and data sharing’ [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 7 , 29 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 41 , 43 ].

2. Influence on policy making.

Methodological frameworks addressing this major impact category focused on measurable improvements within a given knowledge base and on interactions between academics and policy makers, which may influence policy-making development and implementation. The returns generated in this impact category are generally considered as intermediate or midterm (1 to 3 years). These represent an important interim stage in the process towards the final expected impacts, such as quantifiable health improvements and economic benefits, without which policy change may not occur [ 30 , 62 ]. The following impact subgroups were identified within this category: ‘type and nature of policy impact’, ‘level of policy making’, and ‘policy networks’.

2 . 1 . Type and nature of policy impact . The most common impact subgroup, mentioned in 18 of the 24 frameworks, was ‘type and nature of policy impact’ [ 2 , 7 , 29 – 38 , 41 – 43 , 45 – 47 ]. Methodological frameworks addressing this subgroup stressed the importance of collecting information regarding the influence of research on policy (i.e., changes in practice or terminology). For instance, a project looking at trafficked adolescents and women (2003) influenced the WHO guidelines (2003) on ethics regarding this particular group [ 17 , 21 , 63 ].

2 . 2 . Level of policy impact . Thirteen of 24 frameworks addressed aspects surrounding the need to record the ‘level of policy impact’ (international, national, or local) and the organisations within a level that were influenced (local policy makers, clinical commissioning groups, and health and wellbeing trusts) [ 2 , 5 , 8 , 29 , 31 , 34 , 38 , 41 , 43 – 47 ]. Authors considered it important to measure the ‘level of policy impact’ to provide evidence of collaboration, coordination, and efficiency within health organisations and between researchers and health organisations [ 29 , 31 ].

2 . 3 . Policy networks . Five methodological frameworks highlighted the need to collect information regarding collaborative research with industry and staff movement between academia and industry [ 5 , 7 , 29 , 41 , 43 ]. A policy network emphasises the relationship between policy communities, researchers, and policy makers. This relationship can influence and lead to incremental changes in policy processes [ 62 ].

3. Health and health systems impact.

A number of methodological frameworks advocated the measurement of impacts on health and healthcare systems across the following impact subgroups: ‘quality of care and service delivering’, ‘evidence-based practice’, ‘improved information and health information management’, ‘cost containment and effectiveness’, ‘resource allocation’, and ‘health workforce’.

3 . 1 . Quality of care and service delivery . Twelve of the 24 frameworks highlighted the importance of evaluating ‘quality of care and service delivery’ [ 2 , 5 , 8 , 29 – 31 , 33 – 36 , 41 , 47 ]. There were a number of suggested metrics that could be potentially used for this purpose, including health outcomes such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), patient satisfaction and experience surveys, and qualitative data on waiting times and service accessibility.

3 . 2 . Evidence-based practice . ‘Evidence-based practice’, mentioned in 5 of the 24 frameworks, refers to making changes in clinical diagnosis, clinical practice, treatment decisions, or decision making based on research evidence [ 5 , 8 , 29 , 31 , 33 ]. The suggested metrics to demonstrate evidence-based practice were adoption of health technologies and research outcomes to improve the healthcare systems and inform policies and guidelines [ 29 ].

3 . 3 . Improved information and health information management . This impact subcategory, mentioned in 5 of the 24 frameworks, refers to the influence of research on the provision of health services and management of the health system to prevent additional costs [ 5 , 29 , 33 , 34 , 38 ]. Methodological frameworks advocated the collection of health system financial, nonfinancial (i.e., transport and sociopolitical implications), and insurance information in order to determine constraints within a health system.

3 . 4 . Cost containment and cost-effectiveness . Six of the 24 frameworks advocated the subcategory ‘cost containment and cost-effectiveness’ [ 2 , 5 , 8 , 17 , 33 , 36 ]. ‘Cost containment’ comprised the collection of information regarding how research has influenced the provision and management of health services and its implication in healthcare resource allocation and use [ 29 ]. ‘Cost-effectiveness’ refers to information concerning economic evaluations to assess improvements in effectiveness and health outcomes—for instance, the cost-effectiveness (cost and health outcome benefits) assessment of introducing a new health technology to replace an older one [ 29 , 31 , 64 ].

3 . 5 . Resource allocation . ‘Resource allocation’, mentioned in 6frameworks, can be measured through 2 impact metrics: new funding attributed to the intervention in question and equity while allocating resources, such as improved allocation of resources at an area level; better targeting, accessibility, and utilisation; and coverage of health services [ 2 , 5 , 29 , 31 , 45 , 47 ]. The allocation of resources and targeting can be measured through health services research reports, with the utilisation of health services measured by the probability of providing an intervention when needed, the probability of requiring it again in the future, and the probability of receiving an intervention based on previous experience [ 29 , 31 ].

3 . 6 . Health workforce . Lastly, ‘health workforce’, present in 3 methodological frameworks, refers to the reduction in the days of work lost because of a particular illness [ 2 , 5 , 31 ].

4. Health-related and societal impact.

Three subgroups were included in this category: ‘health literacy’; ‘health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours’; and ‘improved social equity, inclusion, or cohesion’.

4 . 1 . Health knowledge , attitudes , and behaviours . Eight of the 24 frameworks suggested the assessment of ‘health knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, and outcomes’, which could be measured through the evaluation of levels of public engagement with science and research (e.g., National Health Service (NHS) Choices end-user visit rate) or by using focus groups to analyse changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour among society [ 2 , 5 , 29 , 33 – 35 , 38 , 43 ].

4 . 2 . Improved equity , inclusion , or cohesion and human rights . Other methodological frameworks, 4 of the 24, suggested capturing improvements in equity, inclusion, or cohesion and human rights. Authors suggested these could be using a resource like the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (superseded by Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs] in 2015) and human rights [ 29 , 33 , 34 , 38 ]. For instance, a cluster-randomised controlled trial in Nepal, which had female participants, has demonstrated the reduction of neonatal mortality through the introduction of maternity health care, distribution of delivery kits, and home visits. This illustrates how research can target vulnerable and disadvantaged groups. Additionally, this research has been introduced by the World Health Organisation to achieve the MDG ‘improve maternal health’ [ 16 , 29 , 65 ].

4 . 3 . Health literacy . Some methodological frameworks, 3 of the 24, focused on tracking changes in the ability of patients to make informed healthcare decisions, reduce health risks, and improve quality of life, which were demonstrably linked to a particular programme of research [ 5 , 29 , 43 ]. For example, a systematic review showed that when HIV health literacy/knowledge is spread among people living with the condition, antiretroviral adherence and quality of life improve [ 66 ].

5. Broader economic impacts.

Some methodological frameworks, 9 of 24, included aspects related to the broader economic impacts of health research—for example, the economic benefits emerging from the commercialisation of research outputs [ 2 , 5 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 67 ]. Suggested metrics included the amount of funding for research and development (R&D) that was competitively awarded by the NHS, medical charities, and overseas companies. Additional metrics were income from intellectual property, spillover effects (any secondary benefit gained as a repercussion of investing directly in a primary activity, i.e., the social and economic returns of investing on R&D) [ 33 ], patents granted, licences awarded and brought to the market, the development and sales of spinout companies, research contracts, and income from industry.

The benefits contained within the categories ‘health and health systems impact’, ‘health-related and societal impact’, and ‘broader economic impacts’ are considered the expected and final returns of the resources allocated in healthcare research [ 30 , 62 ]. These benefits commonly arise in the long term, beyond 5 years according to some authors, but there was a recognition that this could differ depending on the project and its associated research area [ 4 ].

Data synthesis

Five major impact categories were identified across the 24 included methodological frameworks: (1) ‘primary research-related impact’, (2) ‘influence on policy making’, (3) ‘health and health systems impact’, (4) ‘health-related and societal impact’, and (5) ‘broader economic impact’. These major impact categories were further subdivided into 16 impact subgroups. The included publications proposed 80 different metrics to measure research impact. This impact typology synthesis is depicted in ‘the impact matrix’ ( Fig 2 and Fig 3 ).

CIHR, Canadian Institutes of Health Research; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; PHC RIS, Primary Health Care Research & Information Service; RAE, Research Assessment Exercise; RQF, Research Quality Framework.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370.g002

AIHS, Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions; CAHS, Canadian Institutes of Health Research; IOM, Impact Oriented Monitoring; REF, Research Excellence Framework; SIAMPI, Social Impact Assessment Methods for research and funding instruments through the study of Productive Interactions between science and society.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370.g003

Commonality and differences across frameworks

The ‘Research Impact Framework’ and the ‘Health Services Research Impact Framework’ were the models that encompassed the largest number of the metrics extracted. The most dominant methodological framework was the Payback Framework; 7 other methodological framework models used the Payback Framework as a starting point for development [ 8 , 29 , 31 – 35 ]. Additional methodological frameworks that were commonly incorporated into other tools included the CIHR framework, the CAHS model, the AIHS framework, and the Exchange model [ 8 , 33 , 34 , 44 ]. The capture of ‘research-related impact’ was the most widely advocated concept across methodological frameworks, illustrating the importance with which primary short-term impact outcomes were viewed by the included papers. Thus, measurement of impact via number of publications, citations, and peer-reviewed articles was the most common. ‘Influence on policy making’ was the predominant midterm impact category, specifically the subgroup ‘type and nature of policy impact’, in which frameworks advocated the measurement of (i) changes to legislation, regulations, and government policy; (ii) influence and involvement in decision-making processes; and (iii) changes to clinical or healthcare training, practice, or guidelines. Within more long-term impact measurement, the evaluations of changes in the ‘quality of care and service delivery’ were commonly advocated.

In light of the commonalities and differences among the methodological frameworks, the ‘pathways to research impact’ diagram ( Fig 4 ) was developed to provide researchers, funders, and policy makers a more comprehensive and exhaustive way to measure healthcare research impact. The diagram has the advantage of assorting all the impact metrics proposed by previous frameworks and grouping them into different impact subgroups and categories. Prospectively, this global picture will help researchers, funders, and policy makers plan strategies to achieve multiple pathways to impact before carrying the research out. The analysis of the data extraction and construction of the impact matrix led to the development of the ‘pathways to research impact’ diagram ( Fig 4 ). The diagram aims to provide an exhaustive and comprehensive way of tracing research impact by combining all the impact metrics presented by the different 24 frameworks, grouping those metrics into different impact subgroups, and grouping these into broader impact categories.

NHS, National Health Service; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; R&D, research and development.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370.g004

This review has summarised existing methodological impact frameworks together for the first time using systematic methods ( Fig 4 ). It allows researchers and funders to consider pathways to impact at the design stage of a study and to understand the elements and metrics that need to be considered to facilitate prospective assessment of impact. Users do not necessarily need to cover all the aspects of the methodological framework, as every research project can impact on different categories and subgroups. This review provides information that can assist researchers to better demonstrate impact, potentially increasing the likelihood of conducting impactful research and reducing research waste. Existing reviews have not presented a methodological framework that includes different pathways to impact, health impact categories, subgroups, and metrics in a single methodological framework.

Academic-orientated frameworks included in this review advocated the measurement of impact predominantly using so-called ‘quantitative’ metrics—for example, the number of peer-reviewed articles, journal impact factor, and citation rates. This may be because they are well-established measures, relatively easy to capture and objective, and are supported by research funding systems. However, these metrics primarily measure the dissemination of research finding rather than its impact [ 30 , 68 ]. Whilst it is true that wider dissemination, especially when delivered via world-leading international journals, may well lead eventually to changes in healthcare, this is by no means certain. For instance, case studies evaluated by Flinders University of Australia demonstrated that some research projects with non-peer-reviewed publications led to significant changes in health policy, whilst the studies with peer-reviewed publications did not result in any type of impact [ 68 ]. As a result, contemporary literature has tended to advocate the collection of information regarding a variety of different potential forms of impact alongside publication/citations metrics [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 29 – 47 ], as outlined in this review.

The 2014 REF exercise adjusted UK university research funding allocation based on evidence of the wider impact of research (through case narrative studies and quantitative metrics), rather than simply according to the quality of research [ 12 ]. The intention was to ensure funds were directed to high-quality research that could demonstrate actual realised benefit. The inclusion of a mixed-method approach to the measurement of impact in the REF (narrative and quantitative metrics) reflects a widespread belief—expressed by the majority of authors of the included methodological frameworks in the review—that individual quantitative impact metrics (e.g., number of citations and publications) do not necessary capture the complexity of the relationships involved in a research project and may exclude measurement of specific aspects of the research pathway [ 10 , 12 ].

Many of the frameworks included in this review advocated the collection of a range of academic, societal, economic, and cultural impact metrics; this is consistent with recent recommendations from the Stern review [ 10 ]. However, a number of these metrics encounter research ‘lag’: i.e., the time between the point at which the research is conducted and when the actual benefits arise [ 69 ]. For instance, some cardiovascular research has taken up to 25 years to generate impact [ 70 ]. Likewise, the impact may not arise exclusively from a single piece of research. Different processes (such as networking interactions and knowledge and research translation) and multiple individuals and organisations are often involved [ 4 , 71 ]. Therefore, attributing the contribution made by each of the different actors involved in the process can be a challenge [ 4 ]. An additional problem associated to attribution is the lack of evidence to link research and impact. The outcomes of research may emerge slowly and be absorbed gradually. Consequently, it is difficult to determine the influence of research in the development of a new policy, practice, or guidelines [ 4 , 23 ].

A further problem is that impact evaluation is conducted ‘ex post’, after the research has concluded. Collecting information retrospectively can be an issue, as the data required might not be available. ‘ex ante’ assessment is vital for funding allocation, as it is necessary to determine the potential forthcoming impact before research is carried out [ 69 ]. Additionally, ex ante evaluation of potential benefit can overcome the issues regarding identifying and capturing evidence, which can be used in the future [ 4 ]. In order to conduct ex ante evaluation of potential benefit, some authors suggest the early involvement of policy makers in a research project coupled with a well-designed strategy of dissemination [ 40 , 69 ].

Providing an alternate view, the authors of methodological frameworks such as the SIAMPI, Contribution Mapping, Research Contribution, and the Exchange model suggest that the problems of attribution are a consequence of assigning the impact of research to a particular impact metric [ 7 , 40 , 42 , 44 ]. To address these issues, these authors propose focusing on the contribution of research through assessing the processes and interactions between stakeholders and researchers, which arguably take into consideration all the processes and actors involved in a research project [ 7 , 40 , 42 , 43 ]. Additionally, contributions highlight the importance of the interactions between stakeholders and researchers from an early stage in the research process, leading to a successful ex ante and ex post evaluation by setting expected impacts and determining how the research outcomes have been utilised, respectively [ 7 , 40 , 42 , 43 ]. However, contribution metrics are generally harder to measure in comparison to academic-orientated indicators [ 72 ].

Currently, there is a debate surrounding the optimal methodological impact framework, and no tool has proven superior to another. The most appropriate methodological framework for a given study will likely depend on stakeholder needs, as each employs different methodologies to assess research impact [ 4 , 37 , 41 ]. This review allows researchers to select individual existing methodological framework components to create a bespoke tool with which to facilitate optimal study design and maximise the potential for impact depending on the characteristic of their study ( Fig 2 and Fig 3 ). For instance, if researchers are interested in assessing how influential their research is on policy making, perhaps considering a suite of the appropriate metrics drawn from multiple methodological frameworks may provide a more comprehensive method than adopting a single methodological framework. In addition, research teams may wish to use a multidimensional approach to methodological framework development, adopting existing narratives and quantitative metrics, as well as elements from contribution frameworks. This approach would arguably present a more comprehensive method of impact assessment; however, further research is warranted to determine its effectiveness [ 4 , 69 , 72 , 73 ].

Finally, it became clear during this review that the included methodological frameworks had been constructed using varied methodological processes. At present, there are no guidelines or consensus around the optimal pathway that should be followed to develop a robust methodological framework. The authors believe this is an area that should be addressed by the research community, to ensure future frameworks are developed using best-practice methodology.

For instance, the Payback Framework drew upon a literature review and was refined through a case study approach. Arguably, this approach could be considered inferior to other methods that involved extensive stakeholder involvement, such as the CIHR framework [ 8 ]. Nonetheless, 7 methodological frameworks were developed based upon the Payback Framework [ 8 , 29 , 31 – 35 ].

Limitations

The present review is the first to summarise systematically existing impact methodological frameworks and metrics. The main limitation is that 50% of the included publications were found through methods other than bibliographic databases searching, indicating poor indexing. Therefore, some relevant articles may not have been included in this review if they failed to indicate the inclusion of a methodological impact framework in their title/abstract. We did, however, make every effort to try to find these potentially hard-to-reach publications, e.g., through forwards/backwards citation searching, hand searching reference lists, and expert communication. Additionally, this review only extracted information regarding the methodology followed to develop each framework from the main publication source or framework webpage. Therefore, further evaluations may not have been included, as they are beyond the scope of the current paper. A further limitation was that although our search strategy did not include language restrictions, we did not specifically search non-English language databases. Thus, we may have failed to identify potentially relevant methodological frameworks that were developed in a non-English language setting.

In conclusion, the measurement of research impact is an essential exercise to help direct the allocation of limited research resources, to maximise benefit, and to help minimise research waste. This review provides a collective summary of existing methodological impact frameworks and metrics, which funders may use to inform the measurement of research impact and researchers may use to inform study design decisions aimed at maximising the short-, medium-, and long-term impact of their research.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. search strategy..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370.s001

S1 PRISMA Checklist. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370.s002

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank Mrs Susan Bayliss, Information Specialist, University of Birmingham, and Mrs Karen Biddle, Research Secretary, University of Birmingham.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. HEFCE. REF 2014: Assessment framework and guidance on submissions 2011 [cited 2016 15 Feb]. Available from: http://www.ref.ac.uk/media/ref/content/pub/assessmentframeworkandguidanceonsubmissions/GOS%20including%20addendum.pdf .

- 8. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Developing a CIHR framework to measure the impact of health research 2005 [cited 2016 26 Feb]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/MR21-65-2005E.pdf .

- 9. HEFCE. HEFCE allocates £3.97 billion to universities and colleges in England for 2015–1 2015. Available from: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/news/newsarchive/2015/Name,103785,en.html .

- 10. Stern N. Building on Success and Learning from Experience—An Independent Review of the Research Excellence Framework 2016 [cited 2016 05 Aug]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/541338/ind-16-9-ref-stern-review.pdf .

- 11. Matthews D. REF sceptic to lead review into research assessment: Times Higher Education; 2015 [cited 2016 21 Apr]. Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/ref-sceptic-lead-review-research-assessment .

- 12. HEFCE. The Metric Tide—Report of the Independent Review of the Role of Metrics in Research Assessment and Management 2015 [cited 2016 11 Aug]. Available from: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/media/HEFCE,2014/Content/Pubs/Independentresearch/2015/The,Metric,Tide/2015_metric_tide.pdf .

- 14. LSE Public Policy Group. Maximizing the impacts of your research: A handbook for social scientists. http://www.lse.ac.uk/government/research/resgroups/LSEPublicPolicy/Docs/LSE_Impact_Handbook_April_2011.pdf . London: LSE; 2011.

- 15. HEFCE. Consultation on the second Research Excellence Framework. 2016.

- 18. Merriam-Webster Dictionary 2017. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/methodology .

- 19. Oxford Dictionaries—pathway 2016 [cited 2016 19 June]. Available from: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/pathway .

- 20. Oxford Dictionaries—metric 2016 [cited 2016 15 Sep]. Available from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/metric .

- 21. WHO. WHO Ethical and Safety Guidelines for Interviewing Trafficked Women 2003 [cited 2016 29 July]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mip/2003/other_documents/en/Ethical_Safety-GWH.pdf .

- 31. Kalucy L, et al. Primary Health Care Research Impact Project: Final Report Stage 1 Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research & Information Service; 2007 [cited 2016 26 Feb]. Available from: http://www.phcris.org.au/phplib/filedownload.php?file=/elib/lib/downloaded_files/publications/pdfs/phcris_pub_3338.pdf .

- 33. Canadian Academy of Health Sciences. Making an impact—A preferred framework and indicators to measure returns on investment in health research 2009 [cited 2016 26 Feb]. Available from: http://www.cahs-acss.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/ROI_FullReport.pdf .

- 39. HEFCE. RAE 2008—Guidance in submissions 2005 [cited 2016 15 Feb]. Available from: http://www.rae.ac.uk/pubs/2005/03/rae0305.pdf .

- 41. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. The societal impact of applied health research—Towards a quality assessment system 2002 [cited 2016 29 Feb]. Available from: https://www.knaw.nl/en/news/publications/the-societal-impact-of-applied-health-research/@@download/pdf_file/20021098.pdf .

- 48. Weiss CH. Using social research in public policy making: Lexington Books; 1977.

- 50. Kogan M, Henkel M. Government and research: the Rothschild experiment in a government department: Heinemann Educational Books; 1983.

- 51. Thomas P. The Aims and Outcomes of Social Policy Research. Croom Helm; 1985.

- 52. Bulmer M. Social Science Research and Government: Comparative Essays on Britain and the United States: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- 53. Booth T. Developing Policy Research. Aldershot, Gower1988.

- 55. Kalucy L, et al Exploring the impact of primary health care research Stage 2 Primary Health Care Research Impact Project Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research & Information Service (PHCRIS); 2009 [cited 2016 26 Feb]. Available from: http://www.phcris.org.au/phplib/filedownload.php?file=/elib/lib/downloaded_files/publications/pdfs/phcris_pub_8108.pdf .

- 56. CHSRF. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation 2000. Health Services Research and Evidence-based Decision Making [cited 2016 February]. Available from: http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/migrated/pdf/mythbusters/EBDM_e.pdf .

- 58. W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Logic Model Development Guide 2004 [cited 2016 19 July]. Available from: http://www.smartgivers.org/uploads/logicmodelguidepdf.pdf .

- 59. United Way of America. Measuring Program Outcomes: A Practical Approach 1996 [cited 2016 19 July]. Available from: https://www.bttop.org/sites/default/files/public/W.K.%20Kellogg%20LogicModel.pdf .

- 60. Nutley S, Percy-Smith J and Solesbury W. Models of research impact: a cross sector review of literature and practice. London: Learning and Skills Research Centre 2003.

- 61. Spaapen J, van Drooge L. SIAMPI final report [cited 2017 Jan]. Available from: http://www.siampi.eu/Content/SIAMPI_Final%20report.pdf .

- 63. LSHTM. The Health Risks and Consequences of Trafficking in Women and Adolescents—Findings from a European Study 2003 [cited 2016 29 July]. Available from: http://www.oas.org/atip/global%20reports/zimmerman%20tip%20health.pdf .

- 70. Russell G. Response to second HEFCE consultation on the Research Excellence Framework 2009 [cited 2016 04 Apr]. Available from: http://russellgroup.ac.uk/media/5262/ref-consultation-response-final-dec09.pdf .

- Open access

- Published: 26 May 2022

Structural changes in the Russian health care system: do they match European trends?

- Sergey Shishkin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0807-3277 1 ,

- Igor Sheiman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5238-4187 2 ,

- Vasily Vlassov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5203-549X 2 ,

- Elena Potapchik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7004-3100 1 &

- Svetlana Sazhina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2023-3384 1

Health Economics Review volume 12 , Article number: 29 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7408 Accesses

3 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

In the last two decades, health care systems (HCS) in the European countries have faced global challenges and have undergone structural changes with the focus on early disease prevention, strengthening primary care, changing the role of hospitals, etc. Russia has inherited the Semashko model from the USSR with dominance of inpatient care, and has been looking for the ways to improve the structure of service delivery. This paper compares the complex of structural changes in the Russian and the European HCS.

We address major developments in four main areas of medical care delivery: preventive activities, primary care, inpatient care, long-term care. Our focus is on the changes in the organizational structure and activities of health care providers, and in their interaction to improve service delivery. To describe the ongoing changes, we use both qualitative characteristics and quantitative indicators. We extracted the relevant data from the national and international databases and reports and calculated secondary estimates. We also used data from our survey of physicians and interviews with top managers in medical care system.

The main trends of structural changes in Russia HCS are similar to the changes in most EU countries. The prevention and the early detection of diseases have developed intensively. The reduction in hospital bed capacity and inpatient care utilization has been accompanied by a decrease in the average length of hospital stay. Russia has followed the European trend of service delivery concentration in hospital-physician complexes, while the increase in the average size of hospitals is even more substantial. However, distinctions in health care delivery organization in Russia are still significant. Changes in primary care are much less pronounced, the system remains hospital centered. Russia lags behind the European leaders in terms of horizontal ties between providers. The reasons for inadequate structural changes are rooted in the governance of service delivery.

The structural transformations must be intensified with the focus on strengthening primary care, further integration of care, and development of new organizational structures that mitigate the dependence on inpatient care.

In the last two decades, health care systems in the European Union countries have faced global challenges, including aging populations, a substantial rise in chronic and multiple diseases, the emergence of new medical and information technologies, and a growing citizen awareness of the role of a healthy lifestyle in disease prevention [ 1 ]. The responses of health systems to these challenges included structural changes in their organization with a focus on the promotion of healthy lifestyles and disease prevention, the growing scale of screening for early disease detection, strengthening primary care, changing the role of the hospitals, the development of chronic disease management programs, etc. [ 2 , 3 ]

Studies of these trends address mostly Western countries. Much less attention has been paid to the post-Soviet countries. In this paper, we study structural changes in the health care in Russia. Russian health care has inherited the Semashko model of health care organization. Its main distinction is state-centered financing, regulation, and provision of health care. The model has specific forms of provider organization, for example, outpatient clinics (polyclinics) with a large number of various specialists, the separation of care for adults and children, and large highly-specialized hospitals [ 4 ].

The Soviet and post-Soviet health systems have been underfunded. Public health funding in the 1990s dropped almost by one third in real terms [ 5 ]. The organization of medical care in the 1990s has not changed significantly relative to Soviet times, and the system has adapted through the reduction in the volume of services and increased payments by patients, frequently informal [ 6 ]. The surge in oil prices after 2000 allowed health funding to increase and while encouraged noticeable changes in service delivery.

The changes in the Russian health system have been discussed in the literature mostly focusing on specific sectors and health finance reforms [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. But these changes in different sectors were not analyzed together, from a single methodological position, as changes in the structural characteristics of the Russian health care system, i.e. the changes in the ratio of different types of medical care, in the structure of medical service providers, in functionalities and modes of their interaction.

The objective of this paper is to explore the entire complex of structural changes over the past two decades in comparison with European trends. What were the structural changes in European health care systems, what were they like in Russia, and how can their differences be explained?

Study design

We followed a six-step methodological framework. The first stage involved designation of the types of medical care and the types of structural changes for identification and comparison. We considered four main areas of medical care delivery: preventive activities, primary care, inpatient care, long-term care. We focused on three different dimensions of structural changes: i) changes in the organizational structure of medical service providers; ii) changes in the structure of their activities (in its types and in their coverage of the population / patients); iii) changes in the organization of interaction between different service providers.

The second stage consisted of identifying for each type of medical care the changes in these three dimensions in the last twenty years before the COVID-19 pandemic. We described the changes that met two criteria: 1) these changes are assessed in the OECD, WHO, and World Bank reviews, and other review publications on this topic as the most noteworthy characteristics of the development of European health care systems, and 2) they have spread in a large number of European countries.

The changes identified according to the formulated criteria cover not all dimensions of structural changes for each type of medical care. For preventive activities, there are changes in the types of activities and in their coverage of the population. In primary and inpatient care, there are changes in the organizational structure of service providers, in the structure of their activities, and in the organization of interaction with other providers. In long-term care, there are changes in the structure of developed activities and their coverage of the population.

To describe the ongoing changes, we use both qualitative characteristics and, if possible, quantitative indicators that highlight them to the greatest extent.

The third stage involved detection of structural changes in four main areas of medical care delivery in Russia. We used the results of our previous studies and conducted an additional search for data characterizing structural changes in health care, using new statistical data, evidence derived from our survey of physicians and interviews with top managers in medical care system.

On the fourth stage we compared the identified structural changes in European health care systems (HCS) with the changes taking place in Russian health care. We identified the presence or absence of similar types of structural changes and the differences between them. The fifth stage was the consideration of the driving forces of structural changes in the Russian health care system. The sixth stage included discussion of the reasons for the distinctions with European developments.

Data sources

To identify the main structural changes in medical care delivery during last twenty years we searched the literature addressing both European HCS and Russia in the all aspects of changes of health care system indicators, better classified by MeSH term “health care reform”. We searched MEDLINE using the query: (russia OR europ* OR “european union” OR semashko) AND health care reform [mh] AND 2000:2021[dp]). All 788 findings were checked manually and 86 were relevant. We also used sources snowballed from these reports and the grey literature related to Russian health care, including those in limited circulation, unpublished documents, memorandums, and presentations from our personal collections covering more than twenty years.

We also used data from an online survey of 999 primary care physicians (further – survey) conducted by the authors in April–May 2019. The respondents representing 82 out of 85 regions of the Russian Federation were asked about implementation of the national prophylactic medical examination program. We also interviewed four leading specialists of the national Ministry of Health on the criteria for the inclusion of the components into the program.

To identify the driving forces of structural changes in the Russian health care system, we used materials from 10 interviews on the issues of implementing state health care programs that we conducted in 2019 with current and former top-managers in the federal government and in five regional governments. We also used the grey literature as well as published reports.

We used statistical data from the international databases of OECD [ 18 ], WHO [ 19 ], World Bank [ 20 ], as well as the Russian sources — the Federal State Statistics Service [ 21 ] and the Russian Research Instuitute of Health [ 22 ]. The data was analyzed for the period from 2000 to the latest date with available data for both EU member states and Russia. To ensure the comparability of the composition of countries in different years, the analysis of the dynamics of some indicators was limited to EU 19 members, i.e. excluding Cyprus, Greece, Croatia, Bulgaria, Luxemburg, Malta, Netherland, Poland, and Romania. The averages for EU 19 estimates are based on population size-weighted averages. If the studied publications and databases did not contain the necessary indicators, we made our own estimates.

Each section of the paper contains a brief description of the main trends in the European countries, and then provides a comparative analysis of the corresponding changes in Russian health care. The comparison is followed by a discussion of the driving forces and the limitations of structural changes in Russia compared to the main European trends. We limited our analysis to the pre – COVID-19 pandemic years.

The development of preventive activities

European hcs.

Most of them have implemented health check-ups, and population and opportunistic screenings for the early detection of diseases. These activities are viewed as a way to improve outcomes by ensuring that health services can focus on diagnosing and treating disease earlier [ 23 ]. The population covered by screenings is high and growing. In Germany 81% of population between 50 and 74 years in 2014 had been tested for colorectal cancer at least once, in Austria 78%, France 60%, Great Britain 48% [ 24 ].

The impact of these activities on health outcomes depends on the selection of preventive services, as well as on their implementation in specific national contexts. The selection of preventive services is increasingly based on research into their potential impact on mortality and other health indicators, as well as their cost effectiveness, with some services being declined because of their inadequate input into health gains [ 25 ]. It is particularly important that screenings are focused on socially disadvantaged groups with the highest probability of disease identification and the expected benefits of their management. Therefore, screening programs are based on the evaluation of local needs. Physicians have discretion in the choice of patients for screenings, depending on their importance for specific groups of the population, and individual risks and preferences.

It is increasingly common for a screening program to include follow-up management of any detected illnesses, with the implication that policy makers design such programs as a set of interrelated preventive and curative activities [ 26 ].

The original Semashko model and the current legislation prioritize preventive activities, while their implementation has been limited by the chronic underfunding of the health system. In the 2000s, the priority of prevention campaigns was revitalized in the form of a national prophylactic medical examination program (Prophylactic Program, called Dispanserization) that is a set of health check-ups and screenings. The major expectation from this Prophylactic Program is the same as in European HCS [ 27 ].

To supplement the analysis of the Prophylactic Program, we analyzed the evidence base for the components of the program and interviewed leading specialists of the federal Ministry of Health on the criteria for the inclusion of the components into the program. We found that some screenings were not evidence based and effect on the population health and/or health of participants is small [ 28 ]. The screening package of the dispanserization was expanded and reduced couple of times, but still number of ineffective screenings are included in the package (electrocardiography (ECG) screening of healthy subjects, prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening of middle age and adult men, urinalysis and routine blood tests, mammography from age 40 etc.).

Primary care physicians play a major role in conducting screenings and check-ups as well as subsequent interventions. There are also public health units responsible exclusively for these preventive activities in big polyclinics. Polled in 2019, primary care physicians responded that in 11% of polyclinics check-ups are carried out in these departments only, and in 24% of primary care organizations the check-ups are conducted by district physicians as well as by staff of these preventive units.

Under the current Prophylactic Program, people over 40 are supposed to have a set of check-ups annually; those 18–39 every three years. Most children go through physicals only. The official estimates of the coverage of the eligible population in the Prophylactic Program are around 100% [ 29 ], while service providers are less optimistic. According to the survey, more than half of the respondents reported that this share was less than 60%, while 17.4% reported less than 20% [ 27 ].

An important shortcoming of the Prophylactic Program design and implementation is the gap between its major objective and the capacity of primary care. The shortage of primary care physicians does not allow the target groups to be provided with all preventive services. Physicians have to distort the service to their registered population and to underprovide the follow-up care of detected cases. The lack of a systematic approach, less focus on local conditions, and the lack of a professional autonomy of providers are the major distinctions between Russian prevention campaigns and similar activities in Europe.

The Prophylactic Program is built on the presumption that preventive activities should include the follow-up management of any detected conditions. There is some evidence, however, that this is not taking place: according to our survey, a half of primary care physicians are unaware of the results of check-ups and screenings. The reported coverage and quality of the follow-up management of identified cases are low: a half of the respondents indicate that less than 60% of patients with identified diseases become objects of the follow-up disease management. Only 7.7% of respondents indicate that a set of disease management services corresponds to a pattern of dispensary surveillance issued by the federal Ministry of Health. The majority reports that these requirements are met only for some patients or are not met at all.

Disease management of newly identified chronic and multiple cases is focused on process rather than outcome indicators. The information on the latter is very fragmented. According to our survey, a decrease in the number of disability days of chronic patients is reported by only 14% of physicians. More than a half of respondents are unaware of the number of emergency care visits and hospital admissions of their chronic patients.

Strengthening primary care

There is a trend of multi-disciplinary primary care practices or networks development and promotion of teamwork and providers coordination in response to the growing complexity of patients. In Spain, France, and the UK it is increasingly common for large general practices to serve more than 20,000 people and provide a wider spectrum of services than in traditional solo and group practices. These emerging extended practices include pharmacists, mental care professionals, dieticians, and sometimes 2–3 specialists [ 30 , 31 ]. The role of nurses is also expanding. Most advanced nurses independently see patients, provide immunizations, health promotion, routine checks for chronically ill patients in all EU member states [ 32 ]. Related to these extended practices is the growing concentration of primary care providers via mergers and reconfigurations that increase the size of the units. The major benefits are economies of scale and scope through staff sharing and better integrated care.

There is also a general trend to strengthen the links with the local community, social care and hospitals [ 32 ]. Primary care providers are increasingly involved in chronic disease management programs together with other professionals in and out of general practices. Links with hospitals are developing beyond simple referral systems [ 33 ].

The trend of multidisciplinary practices development has greatly affected Russian health care. However, this trend in Russia differs significantly from the European HCS. It began in the 1980s, when large numbers of specialists were employed by polyclinics, which are the major providers of both primary care and outpatient specialty care. Today, large urban polyclinics employ 15–20 categories of specialists, and polyclinics in small towns 3–5 categories. The generalist who serves for the catchment area (district doctors) is limited in the scope of services they provide. Multidisciplinary practices are built through employing new specialists, while in European countries mainly through nurses and other categories of staff. Specialists in Russian polyclinics do not supplement, but essentially replace district doctors: they accounted for 66% of visits in 2019. Footnote 1

The scope of district doctors’ services is limited: at least 30–40% of initial visits end with referrals to a specialist or to a hospital, while in Europe only 5–15% [ 35 , 36 ]. Gatekeeping is promoted, but district doctors are overloaded and not interested in expanding the scope of their services. Specialists in polyclinics have insufficient training and poorly equipped, e.g. urologists do not do ureteroscopy and ophthalmologists do not practice surgery.

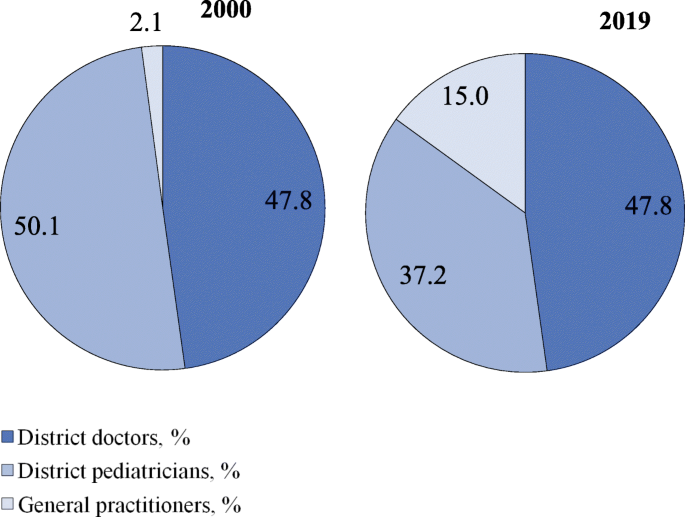

Since the 1990s, some regions started replacing district doctors and pediatricians with general practitioners. But this initiative has not been supported by the federal Ministry of Health, therefore the institution of a general practitioner is not accepted throughout the country. Currently, the share of general practitioners in the total number of generalists serving a catchment area is only 15% (Fig. 1 ). The model of general practice is used only in some regions. The main part of the primary care in the country is provided by district doctors and pediatricians, whose task profile remains narrower than that of general practitioners. The division of primary care for children and adults is preserved. The family is not a whole object of medical care. This division is actively defended by Russian pediatricians with references to specific methods of managing child diseases.

Distribution of generalists in Russia by categories in 2000, 2019. Source: Calculated from RRIH [ 22 , 37 ]

The prevailing trend in all European HCS is to increase the role of nurses. In Russia, the participation of nurses in medical care is limited to fulfilling doctors’ prescriptions and performing ancillary functions.

The transformation of inpatient care

Due to increased costs, technological advances in diagnosis and treatment, there were changes in patterns of diseases and patients treated in hospitals. A substantial amount of inpatient care has been moved to outpatient settings with a respective decrease in bed capacity. This is an almost universal trend in European HCS [ 19 ].

Hospitals continue to be centers of high-tech care, which concentrate most difficult cases and intensify inpatient care with a corresponding decrease in the average length of stay. These changes have been promoted by the move to diagnostic related groups based payment systems and a growing integration with other sectors of service delivery.

In many European countries, most hospitals no longer act as discrete entities and have become units of hospital-physician systems which are multi-level complex adaptive structures [ 3 ]. A new function of hospital specialists is their involvement in chronic disease management in close collaboration with general practitioners, outpatient specialists, and rehabilitative and community care providers [ 38 ].

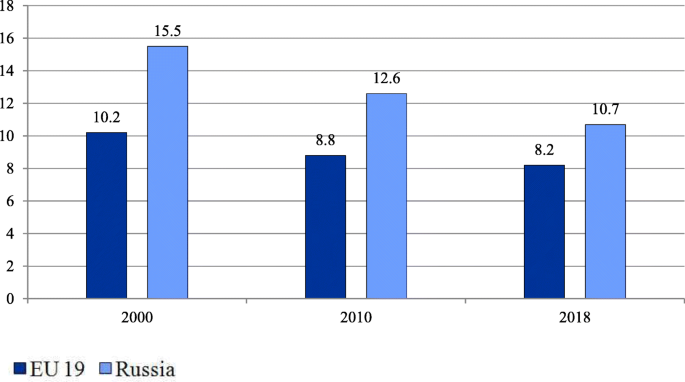

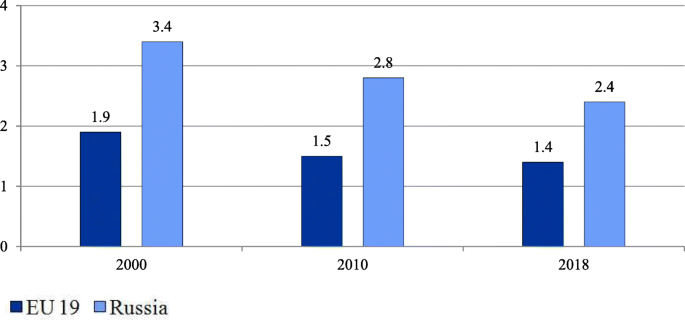

Over the past two decades the treatment of relatively simple cases and preoperative testing have gradually moved to day care wards and polyclinics. In annual health funding, the federal government sets decreasing targets of inpatient care which are obligatory and which regions use to plan their inpatient care. However, inpatient care discharges per 100 people have been almost stable (21.9 in 2000 and 22.4 in 2018) in contrast to the EU 19 members Footnote 2 (18.4 in 2000 and 16.9 in 2018) [ 18 ]. The pressure of decreasing targets resulted in a drop in the average length of hospital stays (Fig. 2 ) and the total bed-days per person (Fig. 3 ). These indicators, along with bed supply (Fig. 4 ), decreased even faster than in the EU.

Average length of stay in hospital in EU members and Russia (days). Note: Calculated for EU 19 member states (see Methods). The EU 19 average length of hospital stay estimates are calculated as the sum of the products of inpatient care discharges by the average length of stay for each country, weighted average by the total inpatient care discharges. Source: OECD Health Statistics [ 18 ]

Number of bed-days per person in the EU and Russia. Note: Calculated for EU 19 member states (see Methods). EU 19 estimates are calculated as the sum of the products of inpatient care discharges by the average length of stay for each country weighted by the total population. Source: OECD Health Statistics [ 18 ]

Hospital beds per 1000 people in the EU and Russia. Note: Calculated as the average for all EU 28 members weighted by the total population. Source: World Bank [ 20 ]

At the same time, the intensity of medical care processes in hospitals in Russia remains significantly lower than in European countries. An indicator of this is the gap in the number of hospital employees per 1000 discharged (Table 1 ).

Over the past 20 years, significant efforts have been made to deploy day wards, both in hospitals and polyclinics, to reduce the burden on hospitals. As a result, the proportion of patients treated in day wards in the total number of patients treated in hospitals increased from 7.6% in 2000 to 20.8% in 2016 [ 21 ]. However, there is fragmentary evidence that this figure is still noticeably lower than in Europe. The share of cataract surgery carried out as ambulatory cases varies in most European countries between 80 to 99% [ 24 ] but is negligible in Russia.

Despite these positive trends, the health system remains hospital centered. The number of bed-days per person remains nearly twice as high as the EU average (Fig. 3 ).