Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.4 The Effects of the Internet and Globalization on Popular Culture and Interpersonal Communication

Learning objectives.

- Describe the effects of globalization on culture.

- Identify the possible effects of news migrating to the Internet.

- Define the Internet paradox.

It’s in the name: World Wide Web . The Internet has broken down communication barriers between cultures in a way that could only be dreamed of in earlier generations. Now, almost any news service across the globe can be accessed on the Internet and, with the various translation services available (like Babelfish and Google Translate), be relatively understandable. In addition to the spread of American culture throughout the world, smaller countries are now able to cheaply export culture, news, entertainment, and even propaganda.

The Internet has been a key factor in driving globalization in recent years. Many jobs can now be outsourced entirely via the Internet. Teams of software programmers in India can have a website up and running in very little time, for far less money than it would take to hire American counterparts. Communicating with these teams is now as simple as sending e-mails and instant messages back and forth, and often the most difficult aspect of setting up an international video conference online is figuring out the time difference. Especially for electronic services such as software, outsourcing over the Internet has greatly reduced the cost to develop a professionally coded site.

Electronic Media and the Globalization of Culture

The increase of globalization has been an economic force throughout the last century, but economic interdependency is not its only by-product. At its core, globalization is the lowering of economic and cultural impediments to communication between countries all over the globe. Globalization in the sphere of culture and communication can take the form of access to foreign newspapers (without the difficulty of procuring a printed copy) or, conversely, the ability of people living in previously closed countries to communicate experiences to the outside world relatively cheaply.

TV, especially satellite TV, has been one of the primary ways for American entertainment to reach foreign shores. This trend has been going on for some time now, for example, with the launch of MTV Arabia (Arango, 2008). American popular culture is, and has been, a crucial export.

At the Eisenhower Fellowship Conference in Singapore in 2005, U.S. ambassador Frank Lavin gave a defense of American culture that differed somewhat from previous arguments. It would not be all Starbucks, MTV, or Baywatch , he said, because American culture is more diverse than that. Instead, he said that “America is a nation of immigrants,” and asked, “When Mel Gibson or Jackie Chan come to the United States to produce a movie, whose culture is being exported (Lavin, 2005)?” This idea of a truly globalized culture—one in which content can be distributed as easily as it can be received—now has the potential to be realized through the Internet. While some political and social barriers still remain, from a technological standpoint there is nothing to stop the two-way flow of information and culture across the globe.

China, Globalization, and the Internet

The scarcity of artistic resources, the time lag of transmission to a foreign country, and censorship by the host government are a few of the possible impediments to transmission of entertainment and culture. China provides a valuable example of the ways the Internet has helped to overcome (or highlight) all three of these hurdles.

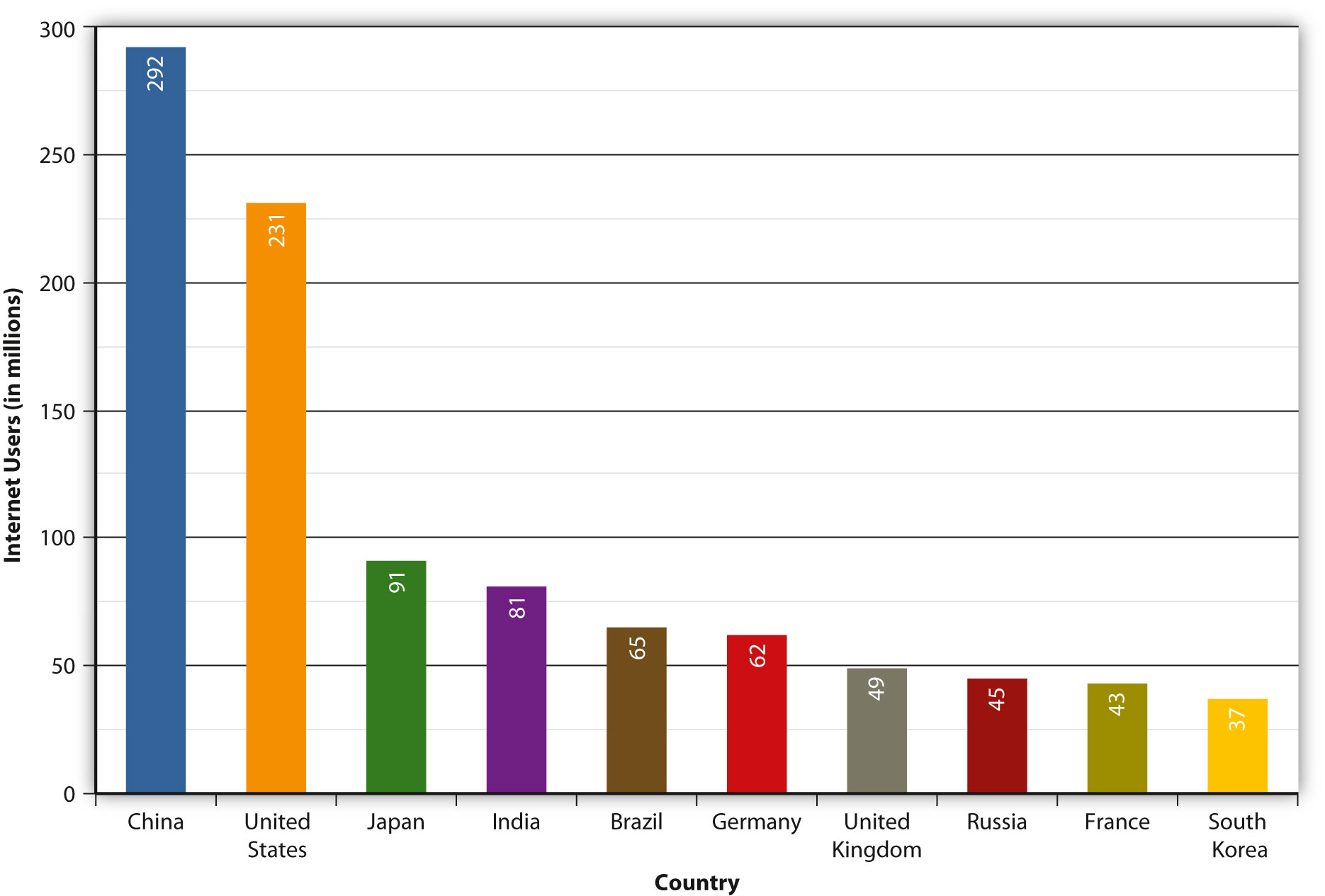

China, as the world’s most populous country and one of its leading economic powers, has considerable clout when it comes to the Internet. In addition, the country is ruled by a single political party that uses censorship extensively in an effort to maintain control. Because the Internet is an open resource by nature, and because China is an extremely well-connected country—with 22.5 percent (roughly 300 million people, or the population of the entire United States) of the country online as of 2008 (Google, 2010)—China has been a case study in how the Internet makes resistance to globalization increasingly difficult.

Figure 11.7

China has more Internet users than any other country.

On January 21, 2010, Hillary Clinton gave a speech in front of the Newseum in Washington, DC, where she said, “We stand for a single Internet where all of humanity has equal access to knowledge and ideas (Ryan & Halper, 2010).” That same month, Google decided it would stop censoring search results on Google.cn, its Chinese-language search engine, as a result of a serious cyber-attack on the company originating in China. In addition, Google stated that if an agreement with the Chinese government could not be reached over the censorship of search results, Google would pull out of China completely. Because Google has complied (albeit uneasily) with the Chinese government in the past, this change in policy was a major reversal.

Withdrawing from one of the largest expanding markets in the world is shocking coming from a company that has been aggressively expanding into foreign markets. This move highlights the fundamental tension between China’s censorship policy and Google’s core values. Google’s company motto, “Don’t be evil,” had long been at odds with its decision to censor search results in China. Google’s compliance with the Chinese government did not help it make inroads into the Chinese Internet search market—although Google held about a quarter of the market in China, most of the search traffic went to the tightly controlled Chinese search engine Baidu. However, Google’s departure from China would be a blow to antigovernment forces in the country. Since Baidu has a closer relationship with the Chinese government, political dissidents tend to use Google’s Gmail, which uses encrypted servers based in the United States. Google’s threat to withdraw from China raises the possibility that globalization could indeed hit roadblocks due to the ways that foreign governments may choose to censor the Internet.

New Media: Internet Convergence and American Society

One only needs to go to CNN’s official Twitter feed and begin to click random faces in the “Following” column to see the effect of media convergence through the Internet. Hundreds of different options abound, many of them individual journalists’ Twitter feeds, and many of those following other journalists. Considering CNN’s motto, “The most trusted name in network news,” its presence on Twitter might seem at odds with providing in-depth, reliable coverage. After all, how in-depth can 140 characters get?

The truth is that many of these traditional media outlets use Twitter not as a communication tool in itself, but as a way to allow viewers to aggregate a large amount of information they may have missed. Instead of visiting multiple home pages to see the day’s top stories from multiple viewpoints, Twitter users only have to check their own Twitter pages to get updates from all the organizations they “follow.” Media conglomerates then use Twitter as part of an overall integration of media outlets; the Twitter feed is there to support the news content, not to report the content itself.

Internet-Only Sources

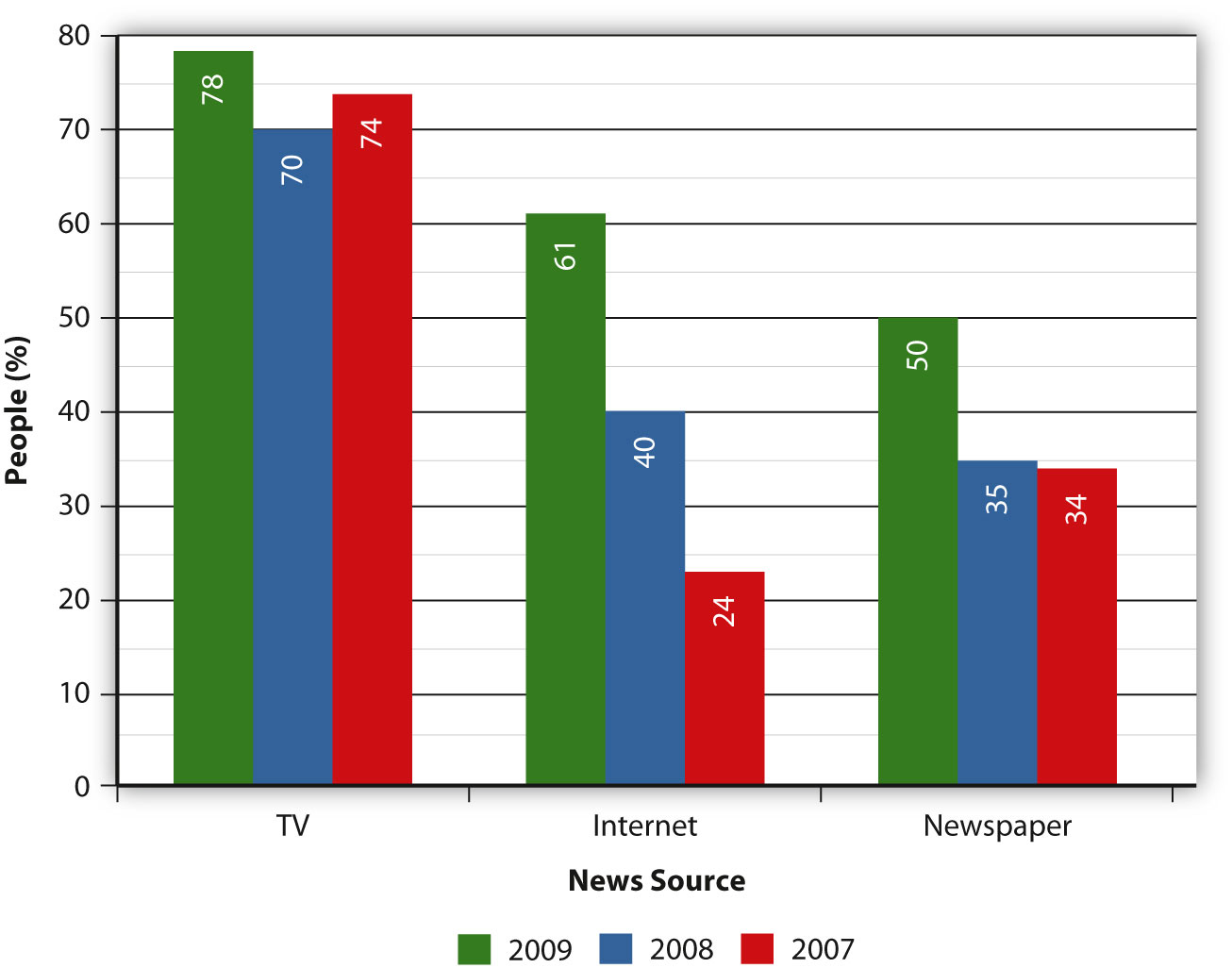

The threshold was crossed in 2008: The Internet overtook print media as a primary source of information for national and international news in the U.S. Television is still far in the lead, but especially among younger demographics, the Internet is quickly catching up as a way to learn about the day’s news. With 40 percent of the public receiving their news from the Internet (see Figure 11.8 ) (Pew Research Center for the People, 2008), media outlets have been scrambling to set up large presences on the web. Yet one of the most remarkable shifts has been in the establishment of online-only news sources.

Figure 11.8

Americans now receive more national and international news from the Internet than they do from newspapers.

The conventional argument claims that the anonymity and the echo chamber of the Internet undermine worthwhile news reporting, especially for topics that are expensive to report on. The ability of large news organizations to put reporters in the field is one of their most important contributions and (because of its cost) is often one of the first things to be cut back during times of budget problems. However, as the Internet has become a primary news source for more and more people, new media outlets—publications existing entirely online—have begun to appear.

In 2006, two reporters for the Washington Post , John F. Harris and Jim VandeHei, left the newspaper to start a politically centered website called Politico. Rather than simply repeating the day’s news in a blog, they were determined to start a journalistically viable news organization on the web. Four years later, the site has over 6,000,000 unique monthly visitors and about a hundred staff members, and there is now a Politico reporter on almost every White House trip (Wolff, 2009).

Far from being a collection of amateurs trying to make it big on the Internet, Politico’s senior White House correspondent is Mike Allen, who previously wrote for The New York Times , Washington Post , and Time . His daily Playbook column appears at around 7 a.m. each morning and is read by much of the politically centered media. The different ways that Politico reaches out to its supporters—blogs, Twitter feeds, regular news articles, and now even a print edition—show how media convergence has even occurred within the Internet itself. The interactive nature of its services and the active comment boards on the site also show how the media have become a two-way street: more of a public forum than a straight news service.

“Live” From New York …

Top-notch political content is not the only medium moving to the Internet, however. Saturday Night Live ( SNL ) has built an entire entertainment model around its broadcast time slot. Every weekend, around 11:40 p.m. on Saturday, someone interrupts a skit, turns toward the camera, shouts “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!” and the band starts playing. Yet the show’s sketch comedy style also seems to lend itself to the watch-anytime convenience of the Internet. In fact, the online TV service Hulu carries a full eight episodes of SNL at any given time, with regular 3.5-minute commercial breaks replaced by Hulu-specific minute-long advertisements. The time listed for an SNL episode on Hulu is just over an hour—a full half-hour less than the time it takes to watch it live on Saturday night.

Hulu calls its product “online premium video,” primarily because of its desire to attract not the YouTube amateur, but rather a partnership of large media organizations. Although many networks, like NBC and Comedy Central, stream video on their websites, Hulu builds its business by offering a legal way to see all these shows on the same site; a user can switch from South Park to SNL with a single click, rather than having to move to a different website.

Premium Online Video Content

Hulu’s success points to a high demand among Internet users for a wide variety of content collected and packaged in one easy-to-use interface. Hulu was rated the Website of the Year by the Associated Press (Coyle, 2008) and even received an Emmy nomination for a commercial featuring Alec Baldwin and Tina Fey, the stars of the NBC comedy 30 Rock (Neil, 2009). Hulu’s success has not been the product of the usual dot-com underdog startup, however. Its two parent companies, News Corporation and NBC Universal, are two of the world’s media giants. In many ways, this was a logical step for these companies to take after fighting online video for so long. In December 2005, the video “Lazy Sunday,” an SNL digital short featuring Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell, went viral with over 5,000,000 views on YouTube before February 2006, when NBC demanded that YouTube take down the video (Biggs, 2006). NBC later posted the video on Hulu, where it could sell advertising for it.

Hulu allows users to break out of programming models controlled by broadcast and cable TV providers and choose freely what shows to watch and when to watch them. This seems to work especially well for cult programs that are no longer available on TV. In 2008, the show Arrested Development , which was canceled in 2006 after repeated time slot shifts, was Hulu’s second-most-popular program.

Hulu certainly seems to have leveled the playing field for some shows that have had difficulty finding an audience through traditional means. 30 Rock , much like Arrested Development , suffered from a lack of viewers in its early years. In 2008, New York Magazine described the show as a “fragile suckling that critics coddle but that America never quite warms up to (Sternbergh, 2008).” However, even as 30 Rock shifted time slots mid-season, its viewer base continued to grow through the NBC partner of Hulu. The nontraditional media approach of NBC’s programming culminated in October 2008, when NBC decided to launch the new season of 30 Rock on Hulu a full week before it was broadcast over the airwaves (Wortham, 2008). Hulu’s strategy of providing premium online content seems to have paid off: As of March 2011, Hulu provided 143,673,000 viewing sessions to more than 27 million unique visitors, according to Nielsen (ComScore, 2011).

Unlike other “premium” services, Hulu does not charge for its content; rather, the word premium in its slogan seems to imply that it could charge for content if it wanted to. Other platforms, like Sony’s PlayStation 3, block Hulu for this very reason—Sony’s online store sells the products that Hulu gives away for free. However, Hulu has been considering moving to a paid subscription model that would allow users to access its entire back catalog of shows. Like many other fledgling web enterprises, Hulu seeks to create reliable revenue streams to avoid the fate of many of the companies that folded during the dot-com crash (Sandoval, 2009).

Like Politico, Hulu has packaged professionally produced content into an on-demand web service that can be used without the normal constraints of traditional media. Just as users can comment on Politico articles (and now, on most newspapers’ articles), they can rate Hulu videos, and Hulu will take this into account. Even when users do not produce the content themselves, they still want this same “two-way street” service.

Table 11.2 Top 10 U.S. Online Video Brands, Home and Work

The Role of the Internet in Social Alienation

In the early years, the Internet was stigmatized as a tool for introverts to avoid “real” social interactions, thereby increasing their alienation from society. Yet the Internet was also seen as the potentially great connecting force between cultures all over the world. The idea that something that allowed communication across the globe could breed social alienation seemed counterintuitive. The American Psychological Association (APA) coined this concept the “ Internet paradox .”

Studies like the APA’s “Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being (Kraut, et. al., 1998)?” which came out in 1998, suggested that teens who spent lots of time on the Internet showed much greater rates of self-reported loneliness and other signs of psychological distress. Even though the Internet had been around for a while by 1998, the increasing concern among parents was that teenagers were spending all their time in chat rooms and online. The fact was that teenagers spent much more time on the Internet than adults, due to their increased free time, curiosity, and familiarity with technology.

However, this did not necessarily mean that “kids these days” were antisocial or that the Internet caused depression and loneliness. In his critical analysis “Deconstructing the Internet Paradox,” computer scientist, writer, and PhD recipient from Carnegie Mellon University Joseph M. Newcomer points out that the APA study did not include a control group to adjust for what may be normal “lonely” feelings in teenagers. Again, he suggests that “involvement in any new, self-absorbing activity which has opportunity for failure can increase depression,” seeing Internet use as just another time-consuming hobby, much like learning a musical instrument or playing chess (Newcomer, 2000).

The general concept that teenagers were spending all their time in chat rooms and online forums instead of hanging out with flesh-and-blood friends was not especially new; the same thing had generally been thought of the computer hobbyists who pioneered the esoteric Usenet. However, the concerns were amplified when a wider range of young people began using the Internet, and the trend was especially strong in the younger demographics.

The “Internet Paradox” and Facebook

As they developed, it became quickly apparent that the Internet generation did not suffer from perpetual loneliness as a rule. After all, the generation that was raised on instant messaging invented Facebook and still makes up most of Facebook’s audience. As detailed earlier in the chapter, Facebook began as a service limited to college students—a requirement that practically excluded older participants. As a social tool and as a reflection of the way younger people now connect with each other over the Internet, Facebook has provided a comprehensive model for the Internet’s effect on social skills and especially on education.

A study by the Michigan State University Department of Telecommunication, Information Studies, and Media has shown that college-age Facebook users connect with offline friends twice as often as they connect with purely online “friends (Ellison, et. al., 2007).” In fact, 90 percent of the participants in the study reported that high school friends, classmates, and other friends were the top three groups that their Facebook profiles were directed toward.

In 2007, when this study took place, one of Facebook’s most remarkable tools for studying the ways that young people connect was its “networks” feature. Originally, a Facebook user’s network consisted of all the people at his or her college e-mail domain: the “mycollege” portion of “[email protected].” The MSU study, performed in April 2006, just 6 months after Facebook opened its doors to high school students, found that first-year students met new people on Facebook 36 percent more often than seniors did. These freshmen, in April 2006, were not as active on Facebook as high schoolers (Facebook began allowing high schoolers on its site during these students’ first semester in school) (Rosen, 2005). The study concluded that they could “definitively state that there is a positive relationship between certain kinds of Facebook use and the maintenance and creation of social capital (Ellison, et. al., 2007).” In other words, even though the study cannot show whether Facebook use causes or results from social connections, it can say that Facebook plays both an important and a nondestructive role in the forming of social bonds.

Although this study provides a complete and balanced picture of the role that Facebook played for college students in early 2006, there have been many changes in Facebook’s design and in its popularity. In 2006, many of a user’s “friends” were from the same college, and the whole college network might be mapped as a “friend-of-a-friend” web. If users allowed all people within a single network access to their profiles, it would create a voluntary school-wide directory of students. Since a university e-mail address was required for signup, there was a certain level of trust. The results of this Facebook study, still relatively current in terms of showing the Internet’s effects on social capital, show that not only do social networking tools not lead to more isolation, but that they actually have become integral to some types of networking.

However, as Facebook began to grow and as high school and regional networks (such as “New York City” or “Ireland”) were incorporated, users’ networks of friends grew exponentially, and the networking feature became increasingly unwieldy for privacy purposes. In 2009, Facebook discontinued regional networks over concerns that networks consisting of millions of people were “no longer the best way for you to control your privacy (Zuckerberg, 2009).” Where privacy controls once consisted of allowing everyone at one’s college access to specific information, Facebook now allows only three levels: friends, friends of friends, and everyone.

Meetup.com : Meeting Up “IRL”

Of course, not everyone on teenagers’ online friends lists are actually their friends outside of the virtual world. In the parlance of the early days of the Internet, meeting up “IRL” (shorthand for “in real life”) was one of the main reasons that many people got online. This practice was often looked at with suspicion by those not familiar with it, especially because of the anonymity of the Internet. The fear among many was that children would go into chat rooms and agree to meet up in person with a total stranger, and that stranger would turn out to have less-than-friendly motives. This fear led to law enforcement officers posing as underage girls in chat rooms, agreeing to meet for sex with older men (after the men brought up the topic—the other way around could be considered entrapment), and then arresting the men at the agreed-upon meeting spot.

In recent years, however, the Internet has become a hub of activity for all sorts of people. In 2002, Scott Heiferman started Meetup.com based on the “simple idea of using the Internet to get people off the Internet (Heiferman, 2009).” The entire purpose of Meetup.com is not to foster global interaction and collaboration (as is the purpose of something like Usenet,) but rather to allow people to organize locally. There are Meetups for politics (popular during Barack Obama’s presidential campaign), for New Yorkers who own Boston terriers (Fairbanks, 2008), for vegan cooking, for board games, and for practically everything else. Essentially, the service (which charges a small fee to Meetup organizers) separates itself from other social networking sites by encouraging real-life interaction. Whereas a member of a Facebook group may never see or interact with fellow members, Meetup.com actually keeps track of the (self-reported) real-life activity of its groups—ideally, groups with more activity are more desirable to join. However much time these groups spend together on or off the Internet, one group of people undoubtedly has the upper hand when it comes to online interaction: World of Warcraft players.

World of Warcraft : Social Interaction Through Avatars

A writer for Time states the reasons for the massive popularity of online role-playing games quite well: “[My generation’s] assumptions were based on the idea that video games would never grow up. But no genre has worked harder to disprove that maxim than MMORPGs—Massively Multiplayer Online Games (Coates, 2007).” World of Warcraft (WoW , for short) is the most popular MMORPG of all time, with over 11 million subscriptions and counting. The game is inherently social; players must complete “quests” in order to advance in the game, and many of the quests are significantly easier with multiple people. Players often form small, four-to five-person groups in the beginning of the game, but by the end of the game these larger groups (called “raiding parties”) can reach up to 40 players.

In addition, WoW provides a highly developed social networking feature called “guilds.” Players create or join a guild, which they can then use to band with other guilds in order to complete some of the toughest quests. “But once you’ve got a posse, the social dynamic just makes the game more addictive and time-consuming,” writes Clive Thompson for Slate (Thompson, 2005). Although these guilds do occasionally meet up in real life, most of their time together is spent online for hours per day (which amounts to quite a bit of time together), and some of the guild leaders profess to seeing real-life improvements. Joi Ito, an Internet business and investment guru, joined WoW long after he had worked with some of the most successful Internet companies; he says he “definitely (Pinckard, 2006)” learned new lessons about leadership from playing the game. Writer Jane Pinckard, for video game blog 1UP , lists some of Ito’s favorite activities as “looking after newbs [lower-level players] and pleasing the veterans,” which he calls a “delicate balancing act (Pinckard, 2006),” even for an ex-CEO.

Figure 11.9

Guilds often go on “raiding parties”—just one of the many semisocial activities in World of Warcraft .

monsieur paradis – gathering in Kargath before a raid – CC BY-NC 2.0.

With over 12 million subscribers, WoW necessarily breaks the boundaries of previous MMORPGs. The social nature of the game has attracted unprecedented numbers of female players (although men still make up the vast majority of players), and its players cannot easily be pegged as antisocial video game addicts. On the contrary, they may even be called social video game players, judging from the general responses given by players as to why they enjoy the game. This type of play certainly points to a new way of online interaction that may continue to grow in coming years.

Social Interaction on the Internet Among Low-Income Groups

In 2006, the journal Developmental Psychology published a study looking at the educational benefits of the Internet for teenagers in low-income households. It found that “children who used the Internet more had higher grade point averages (GPA) after one year and higher scores after standardized tests of reading achievement after six months than did children who used it less,” and that continuing to use the Internet more as the study went on led to an even greater increase in GPA and standardized test scores in reading (there was no change in mathematics test scores) (Jackson, et. al., 2006).

One of the most interesting aspects of the study’s results is the suggestion that the academic benefits may exclude low-performing children in low-income households. The reason for this, the study suggests, is that children in low-income households likely have a social circle consisting of other children from low-income households who are also unlikely to be connected to the Internet. As a result, after 16 months of Internet usage, only 16 percent of the participants were using e-mail and only 25 percent were using instant messaging services. Another reason researchers suggested was that because “African-American culture is historically an ‘oral culture,’” and 83 percent of the participants were African American, the “impersonal nature of the Internet’s typical communication tools” may have led participants to continue to prefer face-to-face contact. In other words, social interaction on the Internet can only happen if your friends are also on the Internet.

The Way Forward: Communication, Convergence, and Corporations

On February 15, 2010, the firm Compete, which analyzes Internet traffic, reported that Facebook surpassed Google as the No. 1 site to drive traffic toward news and entertainment media on both Yahoo! and MSN (Ingram, 2010). This statistic is a strong indicator that social networks are quickly becoming one of the most effective ways for people to sift through the ever-increasing amount of information on the Internet. It also suggests that people are content to get their news the way they did before the Internet or most other forms of mass media were invented—by word of mouth.

Many companies now use the Internet to leverage word-of-mouth social networking. The expansion of corporations into Facebook has given the service a big publicity boost, which has no doubt contributed to the growth of its user base, which in turn helps the corporations that put marketing efforts into the service. Putting a corporation on Facebook is not without risk; any corporation posting on Facebook runs the risk of being commented on by over 500 million users, and of course there is no way to ensure that those users will say positive things about the corporation. Good or bad, communicating with corporations is now a two-way street.

Key Takeaways

- The Internet has made pop culture transmission a two-way street. The power to influence popular culture no longer lies with the relative few with control over traditional forms of mass media; it is now available to the great mass of people with access to the Internet. As a result, the cross-fertilization of pop culture from around the world has become a commonplace occurrence.

- The Internet’s key difference from traditional media is that it does not operate on a set intervallic time schedule. It is not “periodical” in the sense that it comes out in daily or weekly editions; it is always updated. As a result, many journalists file both “regular” news stories and blog posts that may be updated and that can come at varied intervals as necessary. This allows them to stay up-to-date with breaking news without necessarily sacrificing the next day’s more in-depth story.

- The “Internet paradox” is the hypothesis that although the Internet is a tool for communication, many teenagers who use the Internet lack social interaction and become antisocial and depressed. It has been largely disproved, especially since the Internet has grown so drastically. Many sites, such as Meetup.com or even Facebook, work to allow users to organize for offline events. Other services, like the video game World of Warcraft , serve as an alternate social world.

- Make a list of ways you interact with friends, either in person or on the Internet. Are there particular methods of communication that only exist in person?

- Are there methods that exist on the Internet that would be much more difficult to replicate in person?

- How do these disprove the “Internet paradox” and contribute to the globalization of culture?

- Pick a method of in-person communication and a method of Internet communication, and compare and contrast these using a Venn diagram.

Arango, Tim. “World Falls for American Media, Even as It Sours on America,” New York Times , November 30, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/01/business/media/01soft.html .

Biggs, John. “A Video Clip Goes Viral, and a TV Network Wants to Control It,” New York Times , February 20, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/20/business/media/20youtube.html .

Coates, Ta-Nehisi Paul. “Confessions of a 30-Year-Old Gamer,” Time , January 12, 2007, http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1577502,00.html .

ComScore, “ComScore release March 2011 US Online Video Rankings,” April 12, 2011, http://www.comscore.com/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2011/4/ comScore_Releases_March_2011_U.S._Online_Video_Rankings .

Coyle, Jake. “On the Net: Hulu Is Web Site of the Year,” Seattle Times , December 19, 2008, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/entertainment/2008539776_aponthenetsiteoftheyear.html .

Ellison, Nicole B. Charles Steinfield, and Cliff Lampe, “The Benefits of Facebook ‘Friends’: Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14, no. 4 (2007).

Fairbanks, Amanda M. “Funny Thing Happened at the Dog Run,” New York Times , August 23, 2008, cse http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/24/nyregion/24meetup.html .

Google, “Internet users as percentage of population: China,” February 19, 2010, http://www.google.com/publicdata?ds=wb-wdi&met=it_net_user_p2&idim=country: CHN&dl=en&hl=en&q=china+internet+users .

Heiferman, Scott. “The Pursuit of Community,” New York Times , September 5, 2009, cse http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/jobs/06boss.html .

Ingram, Mathew. “Facebook Driving More Traffic Than Google,” New York Times , February 15, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/external/gigaom/2010/02/15/15gigaom-facebook-driving-more-traffic-than-google-42970.html .

Jackson, Linda A. and others, “Does Home Internet Use Influence the Academic Performance of Low-Income Children?” Developmental Psychology 42, no. 3 (2006): 433–434.

Kraut, Robert and others, “Internet Paradox: A Social Technology That Reduces Social Involvement and Psychological Well-Being?” American Psychologist, September 1998, http://psycnet.apa.org/index.cfm?fa=buy.optionToBuy&id=1998-10886-001 .

Lavin, Frank. “‘Globalization and Culture’: Remarks by Ambassador Frank Lavin at the Eisenhower Fellowship Conference in Singapore,” U.S. Embassy in Singapore, June 28, 2005, http://singapore.usembassy.gov/062805.html .

Neil, Dan. “‘30 Rock’ Gets a Wink and a Nod From Two Emmy-Nominated Spots,” Los Angeles Times , July 21, 2009, http://articles.latimes.com/2009/jul/21/business/fi-ct-neil21 .

Newcomer, Joseph M. “Deconstructing the Internet Paradox,” Ubiquity , Association for Computing Machinery, April 2000, http://ubiquity.acm.org/article.cfm?id=334533 . (Originally published as an op-ed in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette , September 27, 1998.).

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, “Internet Overtakes Newspapers as News Outlet,” December 23, 2008, http://people-press.org/report/479/internet-overtakes-newspapers-as-news-source .

Pinckard, Jane. “Is World of Warcraft the New Golf?” 1UP.com , February 8, 2006, http://www.1up.com/news/world-warcraft-golf .

Rosen, Ellen. “THE INTERNET; Facebook.com Goes to High School,” New York Times , October 16, 2005, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05EEDA173FF935A25753C1A9639C8B63&scp=5&sq=facebook&st=nyt .

Ryan, Johnny and Stefan Halper, “Google vs China: Capitalist Model, Virtual Wall,” OpenDemocracy, January 22, 2010, http://www.opendemocracy.net/johnny-ryan-stefan-halper/google-vs-china-capitalist-model-virtual-wall .

Sandoval, Greg. “More Signs Hulu Subscription Service Is Coming,” CNET , October 22, 2009, http://news.cnet.com/8301-31001_3-10381622-261.html .

Sternbergh, Adam. “‘The Office’ vs. ‘30 Rock’: Comedy Goes Back to Work,” New York Magazine , April 10, 2008, http://nymag.com/daily/entertainment/2008/04/the_office_vs_30_rock_comedy_g.html .

Thompson, Clive. “An Elf’s Progress: Finally, Online Role-Playing Games That Won’t Destroy Your Life,” Slate , March 7, 2005, http://www.slate.com/id/2114354 .

Wolff, Michael. “Politico’s Washington Coup,” Vanity Fair , August 2009, http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2009/08/wolff200908 .

Wortham, Jenna. “Hulu Airs Season Premiere of 30 Rock a Week Early,” Wired , October 23, 2008, http://www.wired.com/underwire/2008/10/hulu-airs-seaso/ .

Zuckerberg, Mark. “An Open Letter from Facebook Founder Mark Zuckerberg,” Facebook, December 1, 2009, http://blog.facebook.com/blog.php?post=190423927130 .

Understanding Media and Culture Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 July 2021

Cultural Divergence in popular music: the increasing diversity of music consumption on Spotify across countries

- Pablo Bello ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2343-9617 1 &

- David Garcia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2820-9151 2 , 3 , 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 182 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

32k Accesses

12 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

The digitization of music has changed how we consume, produce, and distribute music. In this paper, we explore the effects of digitization and streaming on the globalization of popular music. While some argue that digitization has led to more diverse cultural markets, others consider that the increasing accessibility to international music would result in a globalized market where a few artists garner all the attention. We tackle this debate by looking at how cross-country diversity in music charts has evolved over 4 years in 39 countries. We analyze two large-scale datasets from Spotify, the most popular streaming platform at the moment, and iTunes, one of the pioneers in digital music distribution. Our analysis reveals an upward trend in music consumption diversity that started in 2017 and spans across platforms. There are now significantly more songs, artists, and record labels populating the top charts than just a few years ago, making national charts more diverse from a global perspective. Furthermore, this process started at the peaks of countries’ charts, where diversity increased at a faster pace than at their bases. We characterize these changes as a process of Cultural Divergence, in which countries are increasingly distinct in terms of the music populating their music charts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Contextual and combinatorial structure in sperm whale vocalisations

The environmental price of fast fashion

Ethnography and ethnohistory support the efficiency of hunting through endurance running in humans

Introduction.

Digitization is arguably the biggest change the music market has undergone over the last decades. In 2016, digital sales already accounted for more than half of the revenues of the music industry (Coelho and Mendes, 2019 ). There are innumerable aspects on which digitization has impacted how we listen, produce, and commercialize music. For example, digital music is distributed at a null marginal cost, meaning that digital audio can be reproduced ad infinitum without an extra cost on the side of the record label. For the consumer, streaming has had homologous effects. In streaming platforms, listening to new music does not carry an extra monetary cost, as a listener only pays a flat monthly fee to subscribe to a platform like Spotify Footnote 1 . This way, time and search costs are the only ones remaining in the way of music exploration. On the distribution side, online catalogs of music are orders of magnitude larger than those of physical stores due to the lack of space constraints, making a more diverse offer of music (Anderson, 2006 ). There is evidence that the increased availability of music has been accompanied by an enhanced diversity and quantity of music consumption (Datta et al., 2018 ). In this paper, we explore the evolution of global diversity in the past years and find a clear trend towards global diversity in the music market.

Concerns of Cultural Convergence have been part of the public debate for decades. European governments, in particular, have made attempts to protect national cultural industries either directly (e.g. radio quotas) or indirectly (e.g. subsidizing national film production) (Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010 ; Waldfogel, 2018 ). Because digitization granted easier access to imported goods, predictions were that national cultural products were doomed, especially in smaller countries. Nonetheless, scientific research has not yet provided a definitive answer to whether this fear was well-grounded or not. There is evidence that digitization might have accelerated cultural convergence across countries in popular music (Gomez-Herrera et al., 2014 ; Verboord and Brandellero, 2018 ) while others find an increasing interest in national artists (Achterberg et al., 2011 ; Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010 ). Discrepancies most likely stem from the inconsistency in the sample of countries included in these studies and the limited granularity of data available. Therefore, the question of whether digitization and streaming are currently propelling cultural convergence is open for debate. For similar cultural products, such as YouTube videos, global convergence is limited by cultural values (Park et al., 2017 ).

The recent availability of datasets on music consumption across large numbers of countries has provided a way of overcoming some limitations of previous studies. In a recent example, Way and his collaborators, look at Spotify users’ listening behavior and find that “home bias”—the preference towards national artists—is on the rise globally (Way et al., 2020 ). A source of concern is the possible influence of a platform’s endogenous processes on the behavior of its users. For instance, what appears as an enhanced preference for national artists could be the result of changes in the recommendation algorithm. Alternatively, increased popularity of playlists like the New Music Friday, which are biased towards national artists (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018a ) could produce a similar effect. Although far from common, major changes in the recommendation system of Spotify happen, the latest one being announced in March of 2019 (Spotify, 2019 ). As a result, recommendations are now more personalized, which, if the nationality of a user is taken into account, could generate increasing divergence between countries by feeding users with national music. According to Spotify, up to one-fifth of their streams can be attributed to algorithmic recommendations (Anderson et al., 2020 ), which may be enough to sway macro-level trends in music consumption.

We deal with platform-specific confounders by supplementing our analysis of Spotify data with a dataset from iTunes. It must be noted, however, that changes similarly affecting both platforms may exist, such as the increasing use of recommendation systems or catalog expansions, as well as the mutual influence that would make these observations non-independent. Another caveat of using platform-specific data is the fact that users of such platforms might not be representative of the entire population. Spotify users are disproportionately young and male when compared to their countries’ population (Datta et al., 2018 ). Furthermore, the composition of users of a platform is in constant change and the timing of adoption correlates with individual listening habits. For instance, in Spotify, late adopters have a stronger preference for local music than those who joined the platform early on (Way et al., 2020 ). To minimize the impact of these issues, we reduce the sample of countries from the 59 available to 39, keeping those in which Spotify is strongly established. Therefore, we expect the population of users in these countries to be more stable than in recently incorporated ones such as India, in which market penetration is quickly expanding. Additionally, this can be considered as a within-sample comparison (Salganik, 2019 ), which, given the large user base of Spotify, is of interest in and on itself.

In this paper, we tackle the question of whether digitized music consumption is globalizing or not by looking at the ecology of the national music charts of Spotify and iTunes in the past few years. In other words, by observing the global diversity in the charts we can discern whether popular music is converging or diverging across countries. More diversity across countries would be a sign of Cultural Divergence. On the other hand, a decrease in diversity would be indicative of a process of Cultural Convergence across countries. We utilize the Rao-Stirling measure of diversity and its components (Stirling, 2007 ) to describe these trends. We find upward trends in the cross-national diversity of songs, artists, and labels, starting in 2017 in Spotify as well as in iTunes and ending in 2020 for Spotify. Popular music is thus diverging across countries in what we define as Cultural Divergence. To complement previous studies, we also look at the diversity of artists and labels and find that these have increased in parallel. Ultimately, this paper describes trends in popular music across a large sample of countries, giving a more clear perspective of the cultural dynamics in the digital era.

Research background

Winner-takes-all.

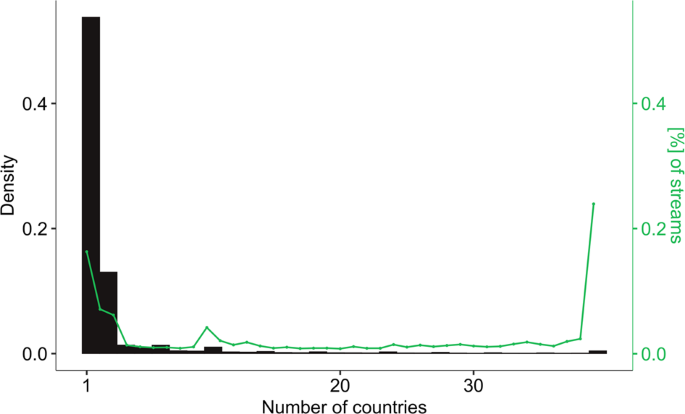

Cultural markets often exhibit a highly skewed distribution of success (e.g. Keuschnigg, 2015 , Salganik et al., 2006 ). In the music market in particular, a few hits expand across the globe while the majority of popular songs only hoard local success (see Fig. 1 ). Such inequalities are partly due to the scalability of cultural products, a property that refers to the fact that most of their cost is fixed – although this property does not apply to all cultural markets, being the art field an exception – while marginal costs are relatively low. For instance, once a song is recorded or a book is written, the cost of making another copy is insignificant when compared to the initial cost of producing it, measured in time, creativity, or money, making these products scalable to large audiences. As a result, demand is highly concentrated on the best alternatives, even when they are only marginally better than the rest (Rosen, 1981 ).

Bars represent the percentage of songs that got to the charts of exactly x countries. The green line represents the total number of streams that songs on each bin have accumulated while in the charts, as a measure of popularity in the period of analysis (2017-mid 2020).

Oftentimes this is an oversimplified view, since quality in cultural products is hard to define, and it is perceived (between others) as a function of previous success, thus creating path dependencies in the popularity of cultural products and artists. This process can be viewed as one in which information is accumulated, with consumers relying on it to moderate the quality uncertainty of their selection of cultural products (Giles, 2007 ). Information is aggregated in the form of consumer reviews, sales rankings, or top charts. In a pathbreaking experimental study, Salganik et al. ( 2006 ) found that information on other listener’s musical preferences results in an amplified inequality of popularity when compared to a world of independent listeners. Using social cues in the form of aggregated information might be beneficial for individuals in cultural markets in which preference is a matter of taste, but there are multiple strategies to leverage such information and its fit varies between individuals (Analytis et al., 2018 ). In the case of artists, during their careers, “small differences in talent become magnified in larger earning differences” (Rosen, 1981 ). This “superstar effect”—defined as the previous success of an artist—is the most important predictor of the popularity of a song, even when controlling for other factors (Interiano et al., 2018 ). Thus, the huge inequalities of success stemming from the scalability of cultural products and the social influence mechanisms intervening in their spread allows for the possibility of a few songs and artists to dominate the charts across the globe.

In principle, both scalability, as well as social influence processes, may have gained bearing after digitization and streaming. On the one hand, digitization reduced the marginal costs of music production by eliminating the need to manufacture an album. Some transaction costs for digital music remain, such as copyrights and distributing platform fees, but overall, the barriers for music to flow across countries are substantially lower than in the pre-digital era. On the other hand, information is more abundant than ever before. Users can get near-real-time data on the listening decisions of millions of other users. On Spotify, anyone can search through the Top 50 playlists tailored for every country. Each of them contains the most popular songs on the platform, which are updated daily. These playlists are extremely popular among users, for instance, the Top 50 Global has over 15 million followers. This deluge of information is complemented with second-order feedback effects (Easley and Kleinberg, 2010 ) such as recommender systems, which might be luring listeners towards the most popular songs. For Spotify, there is evidence that users who rely more heavily on algorithmic recommendations listen to less diverse music and podcasts than those who discover music for themselves (Anderson et al., 2020 , Holtz et al., 2020 ). In short, there are arguments to think that the winner-takes-all effects characteristic of the music market might be gaining bearing under the digital regime, decreasing the diversity and increasing the concentration of the market in the hands of a few hit songs, superstar artists, and major labels.

The long tail

The idea of the long tail, first proposed by Anderson ( 2004 ) in a widely circulated press article sustains that online retailing has led to increased diversity in the consumption of music. This happened because online retailers do not have the limitations of shelf space that traditional brick-and-mortar stores have, and so their catalogs can be virtually unlimited in size. The unlimited digital space can be filled with niche products that do not attract huge audiences but, bit by bit, make a difference in terms of profits generated. In the book following his article, Anderson ( 2006 ) goes beyond the original argument, suggesting that the Internet has a carrying capacity for cultural products previously unattainable and its impact on cultural markets has been broader than initially expected. Not only the distribution but also the production of cultural goods has thrived as a result of the new technologies for distribution (e.g. online retailers), production (e.g. cheaper software), and consumption (e.g. flat fees). Some have even qualified these changes as a renaissance of cultural markets (Waldfogel, 2018 ).

More recently, Aguiar and Waldfogel have argued that the idea of the long tail fails to account for the unpredictability of success in cultural markets (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018b ; Waldfogel, 2017 , 2020 ). When confronted with new artists, for instance, record labels have a scant capacity to assess what will be the success of those artists. Under such uncertainty, producers strive to pick those with better prospects but there will inevitably be miscalculations (e.g. the infamous Decca audition of The Beatles) and artists that were deemed unworthy of being promoted will end up reaping huge success, and the same in the opposite direction. In other words, before digitization, market intermediaries held most of the decision power over which products or artists were worthy of being produced and which ones did not, the inevitable result of which was that some hits were lost. The reduced costs of production and promotion of digital cultural goods have made possible the production of these products. Unlike what the original idea of the long tail proposed, not all of them will be niche products and some will end up achieving unexpected popularity. The same goes for independent record labels, which now have better opportunities to promote their artists even with small budgets. There is evidence that indie artists and labels have gained relevance under the digital music regime (Coelho and Mendes, 2019 ). For instance, top-selling albums in the US produced by independent labels increased from 12% in 2000 to 35% in 2010 (Waldfogel, 2015 ).

Waldfogel and Aguiar refer to this phenomenon as the random long tail of music production. The random long tail contains those cultural goods that despite not being attractive to traditional intermediaries can be brought into production and, due to the inherent unpredictability of cultural markets, sometimes reach unexpected success. Accordingly, the more unpredictable a cultural market is, the greater the number of unexpected hits. For instance, the success of songs is more difficult to predict than that of movies, whose box-office earnings heavily depend on the budget and cast of the film (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018b ). In summary, these studies put forward a vision of the music market in the digital era as more diverse and unpredictable.

Methods and data

Although there are multiple approaches to the study of diversity in social phenomena, Stirling’s ( 2007 ) is one of the most influential and widely applied. More importantly, the Rao–Stirling diversity index has already been used to study diversity in music taste, although at a different level of analysis than here (Park et al., 2015 ; Way et al., 2019 ). The Rao–Stirling index consists of three components: variety, balance, and disparity.

Variety is a function of the number of distinct units (songs, artists, or labels) in the charts on a given day. The more unique units the more variety there is in the charts. Naturally, in the case of songs variety is bounded by the fact that the same song cannot occupy more than one chart position per country so changes in variety should be interpreted, rather than the absolute size of the indicators (which also applies to the other measures of song diversity). We measure variety as the number of distinct units divided by the total number of chart positions. Balance refers to how evenly distributed the system is across units. Here we measure balance as 1−Gini, a common measure of the inequality of a distribution. In this case, it is the distribution of chart positions across songs, artists, or labels. The more equally distributed positions are the higher the balance in the system. Importantly, balance does not give any information about the number of units in the charts (variety). For instance, label balance would be highest if two labels produce all the songs in the charts with equal shares as well as if every song in the charts was produced by a different label (and there were no songs in more than one chart-country). The disparity is defined not by categories themselves but by the qualities of such categories or elements. In other words, the disparity is a measure of how different the elements of a system are. We define the qualities of a song by its acoustic features Footnote 2 and then calculate the euclidean distance between songs. In the case of artists, we define them by the central tendency of the acoustic features of their songs on the charts. The Rao–Stirling index combines variety, balance, and disparity into a single indicator of diversity Footnote 3 .

Additionally, we introduce Zeta diversity, a measure from biology. Zeta diversity was developed by Hui and McGeoch ( 2014 ) to tackle the issues with pairwise measures of diversity. Aggregated pairwise distance measures are consistently biased (Baselga, 2013 ) and, when the number of sites (countries) is large, they approximate their upper limit (Hui and McGeoch, 2014 ). More importantly, Zeta diversity gives a more nuanced view of the interplay between global and local hits. The distribution of the number of countries in which a song reaches the charts is right-skewed, as shown in Fig. 1 , meaning that most songs enter the charts of just one or two countries. As a consequence, what aggregated measures such as Rao–Stirling mainly capture is the effect of local hits. The influence of global hits is mostly null in such measures because of their paucity. Zeta diversity, on the other hand, measures distances at multiple orders. For instance, Zeta of order 3 ( ζ 3 ) represents the expected number of songs shared by groups of three countries. It is calculated by looking at all possible combinations of three countries and calculating the number of songs that each group shares. Higher orders or Zeta (e.g. songs shared by groups of 10 or more countries) capture the prevalence of more global hits. Here, we characterize Zeta by its central tendency, but other options are possible. As the order of Zeta increases its value decreases monotonically since there are always fewer songs charting in groups of three countries than in groups of two. In short, Zeta diversity gives us a more nuanced view of the distribution of success of songs across the charts compared to other diversity measures.

The data for the study comes from Spotify’s top 200 charts and iTunes’ top 100. We illustrate the analysis focusing on Spotify’s data because of the larger sample of countries (39 vs. 19). The entire list of countries can be found in Supplementary Table S1 online. Because iTunes data could not be retrieved from an official source (instead we obtained it through Kworb.com), the results are reported only as a means of externally validating our main findings. Spotify’s data covers the period from 2017-01-01 to 2020-06-20, iTunes top 100 daily charts for the period 2013-08-14 to 2020-07-16.

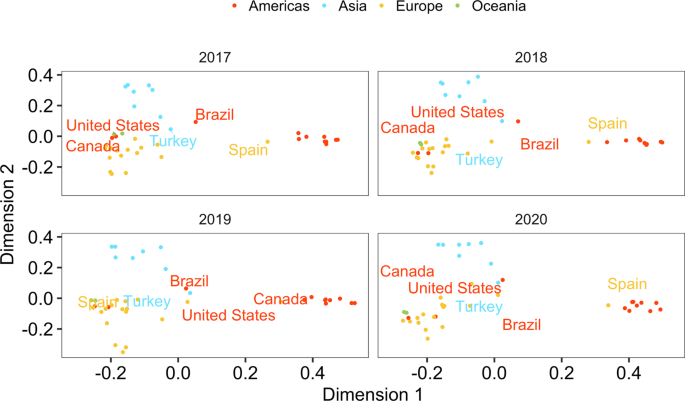

Figure 2 shows distances between countries as a function of the songs shared between their charts within a year. Countries appear geographically clustered. One cluster is formed by Western countries of which Spain is the exception, being part of a different cluster, together with the Latin American countries. The third cluster encapsulates the Asian countries and Brazil. There are some noticeable anomalies, such as the closeness between Turkey and Brazil. Upon closer examination, most of the songs shared between them are produced in the United States. This is likely the result of the small market penetration of Spotify, making for a user base of early adopters more internationally oriented. Alternatively, it could be the result of a small catalog of local music. In any case, the observable consequence is an over-representation of international (and mainly US) hits in both countries’ charts.

Jaccard distances calculated over annually constructed incidence matrices. Countries are colored according to the continent they belong to (red: Americas, yellow: Europe, blue: Asia, Green: Oceania).

Although positions are fairly stable over the years, if anything, clusters of countries seem to consolidate, being these three groups more clearly discernible in 2020 than in 2017. Following Park et al. ( 2017 ) we also look at the relationship between countries as a projection of the two-mode network between countries and songs. The modularity of the network indicates the degree to which countries are clustered into modules beyond what would be expected on a random network. Modularity increased consistently from 2017 up to 2020 (see Supplementary Fig. S4 ) indicating that countries within clusters are becoming more similar in their music charts and, at the same time, drifting away from other clusters. These results are consistent with general notions of cultural, geographical, and linguistic distance which elsewhere have been proved to be the main determinants of music taste similarities between countries (Moore et al., 2014 ; Pichl et al., 2017 ; Schedl et al., 2017 ) although with a few exceptions such as the above-mentioned.

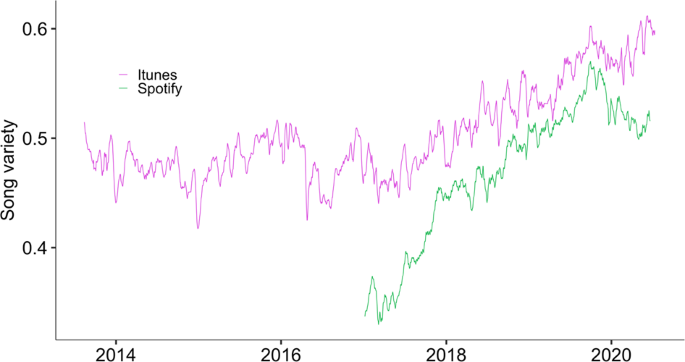

Seen as a whole, the diversity of songs, artists, and labels has increased during this period. Variety has grown not only on Spotify but on iTunes as well (Fig. 3 ). The resemblance between the two trends is startling, especially if we consider how different these platforms are, one being a streaming platform with growing popularity (Spotify) while the other (iTunes) is a digital music shop whose user base is in decay. The resemblance between the trends points to the external validity of the observations, although there could be some degree of influence between the platforms and thus they cannot be regarded as completely independent observations. The upward tendency in variety starts in 2017 and plateaus at the end of 2019 on Spotify while it keeps increasing in iTunes.

Values range from 0 (same set of songs in every country) to 1 (no overlap between the charts). Calculated for countries in both datasets (16 countries) and the same chart size (100 positions). Time series are calculated with daily frequency and smoothed over a 10-day window. Both Spotify and iTunes display consistent trends of increasing variety over time.

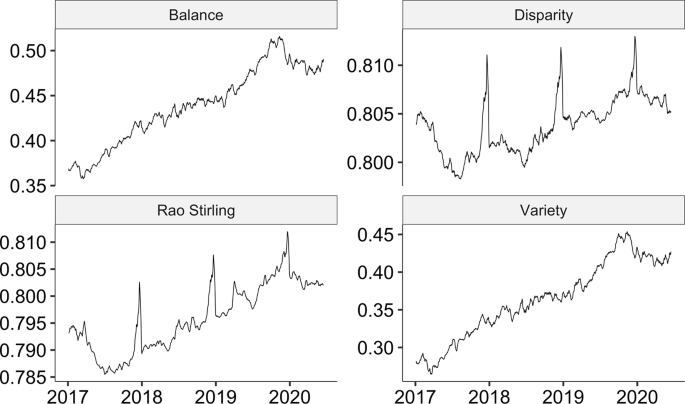

The increase in song diversity can be observed in Fig. 4 . Balance, disparity, and variety have all increased during the period. The disparity indicator also shows a strong seasonal burst around Christmas. This is consistent with other findings, suggesting that in countries in the Northern Hemisphere musical intensity declines around Christmas while the opposite is true for the Southern Hemisphere (Park et al., 2019 ). Overall diversity (Rao–Stirling index) rises from 2017 up to 2020 and then plateaus. Hence, not only there are more distinct songs in the charts (variety) but these are acoustically more dissimilar (disparity) and their distribution over the chart slots is more equal (balance) than at the beginning of the period.

Diversity, measured as balance, disparity, variety, or a combination of them, has been increasing consistently across countries with a plateau at the beginning of the year 2020. Besides the secular growth, disparity shows a strong seasonal component centered around Christmas.

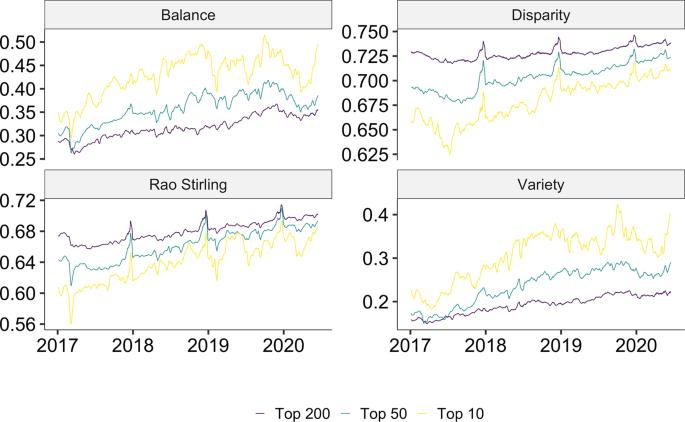

As for songs, the diversity of artists has also grown. However, the trend is distinct at the head of the charts than at the bottom. By slicing charts at certain ranking positions we create a top 10, top 50, and top 200 for each country. When it comes to balance and variety, the increase has been more pronounced at the head of the charts, which already presented a higher level at the beginning of the observed period. However, disparity is lowest within the top 10, indicating that the group of artists with songs on the head of the charts are stylistically more similar than those who just make it to the charts (a group that subsumes the former). What we can derive from these trends is that, while there are proportionally more unique artists at the top of the charts, the music that those artists produce is relatively similar, as if there was an acoustic “recipe” for reaching the peak of the charts. In general, artist diversity as a whole has increased at a similar pace across strata of the charts (Fig. 5 c).

All the components of artist diversity have increased steadily during the period. As for songs, artist disparity bursts around Christmas. While balance and variety are higher at the peak of the charts, disparity shows the opposite pattern.

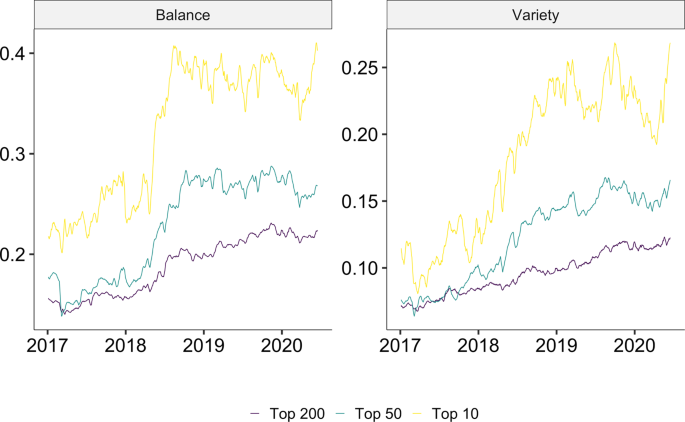

The increasing diversity of songs and artists in the charts has been accompanied by a more equally distributed market for record labels (Fig. 6 a). Again, the trend is steeper if we look only at the head of the charts. The number of distinct labels with at least one song in the charts has also increased in a stratified manner (Fig. 6 b). In general, labels had on average fewer artists and songs on the charts at the end of the period. While in the first 6 months of 2017 labels had on average 5.88 songs on the charts (and 2.19 artists), for the first half of 2020 it was one less song (and only 1.66 artists). Interestingly, the number of songs that each artist got on the charts has increased slightly, going from 2.67 in 2017 to 2.96 in 2020 (comparing the first half of each year).

The left panel shows the balance of labels over time for three sizes of the top chart, displaying increases over time especially for the highest positions in the chart. The right panel shows the variety of labels on the charts. The same patterns as for balance can be observed.

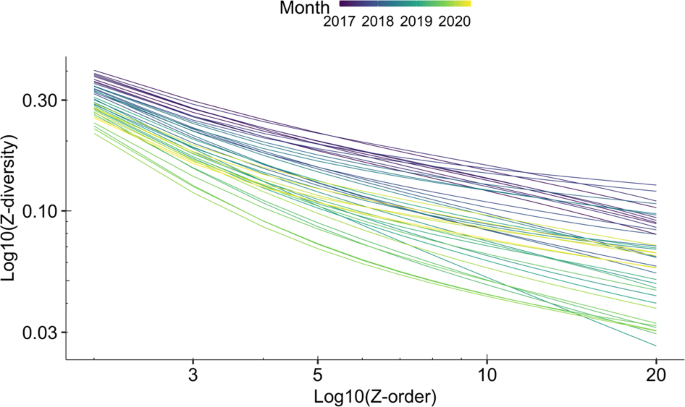

We can take a closer look at the interplay between local and global hits through the Zeta diversity measure. Figure 7 presents the results for monthly Zeta diversity measures of orders 2—which is equivalent to pairwise distances—up to 20—the mean number of common songs shared by groups of 20 countries. We observe that across all orders of Zeta the mean diversity tends to decrease with time (brighter colors) which is consistent with the previous results Footnote 4 . When we look at the decay of Z -values along orders of Zeta ( x -axis) we observe that it gets steeper over time. In other words, the slope of the regression with Z -values ( y -axis) as a dependent variable and Z -order ( x -axis) as a predictor gets greater with time. Table 1 presents the results of a linear regression model that shows the increase in steepness over time. The substantive interpretation is that global hits have taken the lion’s share of the increase in diversity, becoming an increasingly rare phenomenon.

The x -axis represents the order of Zeta and the y -axis the z -value, or mean percentage of songs shared across groups of x countries. Both axes are represented on a log10 scale. The function of Zeta with order shifts down over time and becomes steeper.

By analyzing 4 years of data of music charts in 39 countries, we find clear evidence of increased diversity in the music charts across countries. In the short period covered by this study, the number of unique songs, artists, and labels on the charts in our sample of countries has grown considerably. Despite the concerns expressed by several governments, particularly in Europe (Waldfogel, 2018 , p. 220), popular music is not increasingly globalized. Instead, countries’ popular music was amidst a process of Cultural Divergence that seemed to have come to a halt at the end of the observed period. The increase in diversity seems to be driven by a segmentation of the music market rather than an evenly heightened idiosyncrasy of music consumption. In other words, countries that were already close to one another in taste are becoming more similar but increasingly different from other clusters of countries. Such clusters appear strongly determined, but not only, by geographical and cultural distance. Research shows that regional clusters also differ in the acoustic properties of the music that their populations listen to (Park et al., 2019 ). Therefore, although diversity is usually taken as a positive trait of a system, the segmentation which is driving the increase in diversity can be a source of concern.

We also show that diversity has been on the rise in terms of artists and record labels. Particularly, the rise of label diversity rules out the possibility that the big labels are producing pop music fitted to different markets, as the proponents of glocalization would argue. As a consequence of these trends, not only songs might be increasingly distinct across countries, but also their production and distribution.

Whether it is the preferences of users or shifts in the production and distribution of music that are driving these changes is not clear. The possibility that Cultural Divergence is the result of a random long tail in music production is more consistent with the pace and ubiquity of these changes than preference-based accounts of the same phenomenon. Therefore, as an alternative to preference-based explanations of the increase in home bias (Way et al., 2020 ) and global diversity, we propose that these observations could be explained by changes in music production. One first source of concern with the preference-based explanation stems from the speed and ubiquity of the observed changes. Cultural shifts of this scale are generally slow, comparable in speed to the evolution of traits in animal populations (Lambert et al., 2020 ). Also, there is evidence that changes in the aggregated preferences of a population are mostly driven by generational replacement (Vaisey and Lizardo, 2016 ). Instead, we argue that field configurations can more rapidly sway macro-patterns by conditioning the opportunities of individuals. In the case of music, the random long tail of music production may have increased the available options of users to express their idiosyncratic preferences, which, being to some extent geographically determined (Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010 ; Gomez-Herrera et al., 2014 ; Way et al., 2020 ), would likely result in national music charts drifting away from each other.

Methodologically, this research shows the potential of Zeta diversity, a measure devised for the study of biodiversity, to gauge the globalization of cultural products at different levels. Since truly global hits are extremely rare phenomena when compared to songs that reach in small groups of culturally similar countries, they carry very low weight when calculating pairwise distances, which is a common way of looking at cross-national diversity. National charts could drift apart without affecting the likelihood of the eventual hit to spread globally and conventional pairwise measures would not pick this dynamic. As we show, this has not been the case for the music market, in which the positive trend in diversity has been accompanied by a significant decrease in the spread of global hits. The application of Zeta diversity is not without issues, one of them being that its calculation is computationally demanding when compared with the other measures of diversity presented here, because of its combinatorial nature. In return, it offers relatively stable estimates of rare events, a useful feature when studying heavy-tailed distributions in general, and cultural markets in particular, in which global hits are highly unlikely but more consequential in terms of collective attention than the more common local hits. More broadly, our analysis applies mathematical methods from ecology to analyze the consumption of cultural content. This interface between disciplines has other applications, for example, to understand the dynamical reorganization of user activity on social media (Palazzi et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, our work builds on existing literature utilizing methods from ecology to study musical taste and consumption (Park et al., 2015 ; Way et al., 2019 ).

To conclude, our results run counter to the notion of an unbounded market that can be distilled from the idea of globalization. It also challenges the expectations of the winner-takes-all set of theories that predict heightened inequality in the distribution of success under decreased restrictions to global expansion. Instead, the music market has become, in this short period, more hostile to the spread of hits across the globe. From a positive perspective, this means that “national cultures” are not disappearing, although this might come at the expense of a more segmented market in bundles of culturally similar countries, and the risks associated with such segmentation if spread, for instance, from esthetic to normative judgments.

Data availability

Data and code for the analyses are available at https://github.com/PabloBelloDelpon/Spotify_paper .

Users also have the option to get free access to a limited version of the platform, which is ad-supported.

Spotify measures the acoustic features of each song and groups them into the followingcategories, all of which we include in the analysis: danceability, energy, key, loudness, mode,speechiness, acousticness, instrumentalness, liveness, valence, tempo, and duration.

More precisely, Rao–Stirling is calculated as in Stirling ( 2007 ): D = ∑ it ( i ≠ j ) d ij ⋅ p i ⋅ p j , where p i and p j are the proportions of elements i and j in the system and did is the euclidean distance between their respective acoustic representations.

Zeta diversity is measured in the opposite direction than the previous indicators of diversity. Higher values indicate more overlap of songs across charts and smaller values indicate less overlap.

Achterberg P, Heilbron J, Houtman D, Aupers S (2011) A cultural globalization of popular music? American, Dutch, French, and German popular music charts (1965 to 2006). Am Behav Sci 55(5):589–608

Article Google Scholar

Aguiar L, Waldfogel J (2018a) Platforms, promotion, and product discovery: Evidence from spotify playlists. JRC digital economy working paper, 2018/04

Aguiar L, Waldfogel J (2018b) Quality predictability and the welfare benefits from new products: evidence from the digitization of recorded music. J Polit Econ. https://doi.org/10.1086/696229

Analytis PP, Barkoczi D, Herzog SM (2018) Social learning strategies for matters of taste. Nat Hum Behav 2(6):415–424

Anderson A, Maystre L, Anderson I, Mehrotra R, Lalmas M (2020) Algorithmic effects on the diversity of consumption on spotify. In: Proceedings of the web conference 2020, Taipei, Taiwan. ACM, pp. 2155–2165

Anderson C (2004) The long tail. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2004/10/tail . Accessed 20 Jul 2021

Anderson C (2006) The long tail: why the future of business is selling less of more. Hachette

Google Scholar

Baselga A (2013) Multiple site dissimilarity quantifies compositional heterogeneity among several sites, while average pairwise dissimilarity may be misleading. Ecography 36(2):124–128

Coelho MP, Mendes JZ (2019) Digital music and the death of the long tail. J Bus Res 101:454–460

Datta H, Knox G, Bronnenberg BJ (2018) Changing their tune: how consumers’ adoption of online streaming affects music consumption and discovery. Market Sci 37(1):5–21

Easley D, Kleinberg J (2010) Networks, crowds, and markets: reasoning about a highly connected world. Cambridge University Press

Ferreira F, Waldfogel J (2010) Pop internationalism: has a half century of world music trade displaced local culture? Technical Report w15964. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Giles DE (2007) Increasing returns to information in the US popular music industry. Appl Econ Lett 14(5):327–331

Gomez-Herrera E, Martens B, Waldfogel J (2014) What’s going on? Digitization and global music trade patterns since 2006. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2535803. Social Science Research Network, Rochester

Holtz D, Carterette B, Chandar P, Nazari Z, Cramer H, Aral S (2020) The engagement-diversity connection: evidence from a field experiment on spotify. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3555927, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY

Hui C, McGeoch MA (2014) Zeta diversity as a concept and metric that unifies incidence-based biodiversity patterns. Am Nat 184(5):684–694

Interiano M, Kazemi K, Wang L, Yang J, Yu Z, Komarova NL (2018) Musical trends and predictability of success in contemporary songs in and out of the top charts. R Soc Open Sci 5(5):171274

Article ADS Google Scholar

Keuschnigg M (2015) Product success in cultural markets: the mediating role of familiarity, peers, and experts. Poetics 51:17–36

Lambert B, Kontonatsios G, Mauch M, Kokkoris T, Jockers M, Ananiadou S, Leroi AM (2020) The pace of modern culture. Nat Hum Behav 4(4):352–360

Moore JL, Joachims T, Turnbull D (2014) Taste space versus the world: an embedding analysis of listening habits and geography. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Society for Music information retrieval conference, Taipei, Taiwan

Palazzi MJ, Solé-Ribalta A, Calleja-Solanas V, Meloni S, Plata CA, Suweis S, Borge-Holthoefer J (2020) Resilience and elasticity of co-evolving information ecosystems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.07005

Park M, Park J, Baek YM, Macy M (2017) Cultural values and cross-cultural video consumption on YouTube. PLoS ONE 12(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177865

Park M, Thom J, Mennicken S, Cramer H, Macy M (2019) Global music streaming data reveal diurnal and seasonal patterns of affective preference. Nat Hum Behav 3(3):230–236

Park M, Weber I, Naaman M, Vieweg S (2015) Understanding musical diversity via online social media. In: Proceedings of the ninth international AAAI conference on web and social media, Oxford, UK

Pichl M, Zangerle E, Specht G, Schedl M (2017) Mining culture-specific music listening behavior from social media data. In: 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), Taichung. IEEE, pp. 208–215

Rosen S (1981) The economics of superstars. Am Econ Rev 71:845–858

Salganik MJ (2019) Bit by bit: social research in the digital age. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Salganik MJ, Dodds PS, Watts DJ (2006) Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market Science 311(5762):854–856 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1121066 American Association for the Advancement of Science Section: Report

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Schedl M, Lemmerich F, Ferwerda B, Skowron M, Knees P (2017) Indicators of country similarity in terms of music taste, cultural, and socio-economic factors. In: 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), Taichung. IEEE, pp. 308–311

Spotify (2019) Our playlist ecosystem is evolving: here’s what it means for artists & their teams—news—spotify for artists. https://artists.spotify.com/blog/our-playlist-ecosystem-is-evolving . Accessed 10 Nov 2020

Stirling A (2007) A general framework for analysing diversity in science, technology and society. J R Soc Interface 4(15):707–719

Vaisey S, Lizardo O (2016) Cultural fragmentation or acquired dispositions? a new approach to accounting for patterns of cultural change. Socius 2:1–15

Verboord M, Brandellero A (2018) The globalization of popular music, 1960–2010: a multilevel analysis of music flows. Commun Res 45(4):603–627

Waldfogel J (2015) Digitization and the quality of new media products: the case of music. In Economic analysis of the digital economy. The University of Chicago Press, pp. 407–442

Waldfogel J (2017) The random long tail and the golden age of television. Innov Policy Econ 17:1–25

Waldfogel J (2018) Digital renaissance: what data and economics tell us about the future of popular culture. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Book Google Scholar

Waldfogel J (2020) Digitization and its consequences for creative-industry product and labor markets. In: The role of innovation and entrepreneurship in economic growth. The University of Chicago Press, p. 42

Way SF, Garcia-Gathright J, Cramer H (2020) Local trends in global music streaming. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol. 14. pp. 705–714

Way SF, Gil S, Anderson I, Clauset A (2019) Environmental changes and the dynamics of musical identity. In: Proceedings of the 13th international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol. 13. pp. 527–536

Download references

Acknowledgements

D.G. acknowledges funding from the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) through project VRG16-005. We thank Marc Keuschnigg and Paul Schuler for their insightful comments on previous versions of this article.

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Management and Engineering, The Institute for Analytical Sociology, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Pablo Bello

Graz University of Technology, Vienna, Austria

David Garcia

Complexity Science Hub Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author