A True Story of Living With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

An authentic and personal perspective of the internal battles within the mind..

Posted April 3, 2017

- What Is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?

- Find a therapist to treat OCD

Contributed by Tiffany Dawn Hasse in collaboration with Kristen Fuller, M.D.

The underlying reasons why I have to repeatedly re-zip things, blink a certain way, count to an odd number, check behind my shower curtain to ensure no one is hiding to plot my abduction, make sure that computer cords are not rat tails, etc., will never be clear to me. Is it the result of a poor reaction to the anesthesiology that was administered during my wisdom teeth extraction? These aggravating thoughts and compulsions began immediately after the procedure. Or is it related to PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal infection) which is a proposed theory connoting a strange relationship between group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection with rapidly developing symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the basal ganglia? Is it simply a hereditary byproduct of my genetic makeup associated with my nervous personality ? Or is it a defense tactic I developed through having an overly concerned mother?

The consequences associated with my OCD

Growing up with mild, in fact dormant, obsessive-compulsive disorder, I would have never proposed such bizarre questions until 2002, when an exacerbated overnight onset of severe OCD mentally paralyzed me. I'd just had my wisdom teeth removed and was immediately bombarded with incessant and intrusive unwanted thoughts, ranging from a fear of being gay to questioning if I was truly seeing the sky as blue. I'm sure similar thoughts had passed through my mind before; however, they must have been filtered out of my conscious, as I never had such incapacitating ideas enter my train of thought before. During the summer of 2002, not one thought was left unfiltered from my conscious. Thoughts that didn't even matter and held no significance were debilitating; they prevented me from accomplishing the simplest, most mundane tasks. Tying my shoe only to untie it repetitively, continuously being tardy for work and school, spending long hours in a bathroom engaging in compulsive rituals such as tapping inanimate objects endlessly with no resolution, and finally medically withdrawing from college, eventually to drop out completely not once but twice, were just a few of the consequences I endured.

Seeking help

After seeing a medical specialist for OCD, I had tried a mixed cocktail of medications over a 10-year span, including escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), risperidone (Risperdal), aripiprazole (Abilify), sertraline (Zoloft), clomipramine (Anafranil), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and finally, after a recent bipolar disorder II diagnosis, lurasidone (Latuda). The only medication that has remotely curbed my intrusive thoughts and repetitive compulsions is lurasidone, giving me approximately 60 to 70 percent relief from my symptoms.

Many psychologists and psychiatrists would argue that a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacological management might be the only successful treatment approach for an individual plagued with OCD. If an individual is brave enough to undergo exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), a type of CBT that has been shown to relieve symptoms of OCD and anxiety through desensitization and habituation, then my hat is off to them; however, I may have an alternative perspective. It's not a perspective that has been researched or proven in clinical trials — just a coping mechanism I have learned through years of suffering and endless hours of therapy that has allowed me to see light at the end of the tunnel.

In my experience with cognitive behavioral therapy, it may be semi-helpful by deconstructing or cognitively restructuring the importance of obsessive thoughts in a hierarchical order; however, I still encounter many problems with this type of technique, especially because each and every OCD thought that gets stuck in my mind, big or small, tends to hold great importance. Thoughts associated with becoming pregnant , seeing my family suffer, or living with rats are deeply rooted within me, and simply deconstructing them to meaningless underlying triggers was not a successful approach for me.

In the majority of cases of severe OCD, I believe pharmacological management is a must. A neurological malfunction of transitioning from gear to gear, or fight-or-flight, is surely out of whack and often falsely fired, and therefore, medication works to help balance this misfiring of certain neurotransmitters.

Exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP) is an aggressive and abrasive approach that did not work for me, although it may be helpful for militant-minded souls that seek direct structure. When I was enrolled in the OCD treatment program at UCLA, I had an intense fear of gaining weight, to the point that I thought my body could morph into something unsightly. I remember being encouraged to literally pour chocolate on my thighs when the repetitive fear occurred that chocolate, if touching my skin, could seep through the epidermal layers, and thus make my thighs bigger. While I boldly mustered up the courage to go through with this ERP technique recommended by my specialist, the intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviors associated with my OCD still and often abstain these techniques. Yes, the idea of initially provoking my anxiety in the hope of habituating and desensitizing its triggers sounds great in theory, and even in a technical scientific sense; but as a human with real emotions and feelings, I find this therapy aggressive and infringing upon my comfort level.

How I conquered my OCD

So, what does a person incapacitated with OCD do? If, as a person with severe OCD, I truly had an answer, I would probably leave my house more often, take a risk once in a while, and live freely without fearing the mundane nuances associated with public places. It's been my experience with OCD to take everything one second at a time and remain grateful for those good seconds. If I were to take OCD one day at a time, well, too many millions of internal battles would be lost in this 24-hour period. I have learned to live with my OCD through writing and performing as a spoken word artist. I have taken the time to explore my pain and transmute it into an art form which has allowed me to explore the topic of pain as an interesting and beneficial subject matter. I am the last person to attempt to tell any individuals with OCD what the best therapy approach is for them, but I will encourage each and every individual to explore their own pain, and believe that manageability can come in many forms, from classic techniques to intricate art forms, in order for healing to begin.

Tiffany Dawn Hasse is a performance poet, a TED talk speaker , and an individual successfully living with OCD who strives to share about her disorder through her art of written and spoken word.

Kristen Fuller M.D. is a clinical writer for Center For Discovery.

Facebook image: pathdoc/Shutterstock

Kristen Fuller, M.D., is a physician and a clinical mental health writer for Center For Discovery.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

OCD is so much more than handwashing or tidying. As a historian with the disorder, here’s what I’ve learned

PhD Candidate in History, University of Sheffield

Disclosure statement

Eva Surawy Stepney receives funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) via the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities (WRoCAH).

University of Sheffield provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Readers are advised that this article contains explicit discussion of suicide and suicidal and obsessional thoughts. If you are in need of support, contact details are included at the end of the article.

At the age of 12, “out of nowhere”, Matt says he started having repetitive thoughts concerning whether he wanted to end his life. Every time he saw a knife, he would ask himself: “Am I going to stab myself?” Or, when he was near a ledge: “Am I going to jump?”

Matt had heard a lot about teenage depression, and thought this must be what was going on. But it was confusing, he says: “I didn’t feel suicidal, I really enjoyed my life. I just had an intense fear of doing something to hurt myself.”

Shortly afterwards, pre-empted by hearing about a notorious banned film, Matt began questioning whether he, like the central character, might be a serial killer. These thoughts “kept coming and coming” and he would lie in bed running over scenarios, trying to work out whether he was “going crazy”:

I really needed help. I didn’t know who to talk to. But it wasn’t on my radar to think about this as OCD.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a significant mental health diagnosis in the 21st century. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists it as one of the ten most disabling illnesses in terms of loss of earning and reduced quality of life, and OCD is frequently cited as the fourth most common mental disorder globally after depression, substance abuse and social phobia (anxiety about social interactions).

Yet everything Matt knew about OCD, he tells me, came from daytime talkshows where “people were washing their hands 1,000 times a day – it was all about external and really extreme behaviours”. And that didn’t feel like what he was going through.

Across the world, we’re seeing unprecedented levels of mental illness at all ages, from children to the very old – with huge costs to families, communities and economies. In this series , we investigate what’s causing this crisis, and report on the latest research to improve people’s mental health at all stages of life.

A similar experience is recounted in the 2011 book Taking Control of OCD by John (not his real name) who, after a colleague had taken their own life, became “inundated with thoughts” about what he might do to himself. Every time he crossed the road, John thought: “What would happen if I stopped moving and was run over by a bus?” He also had thoughts of murdering those he loved. John recalled:

Try as I might, I just couldn’t chase the thoughts out of my head … When I tried to explain what was going on to my girlfriend, I couldn’t find a way of articulating what was happening to me … At the time, I thought OCD was all about triple-checking you had locked the front door and that your drawers were tidy.

Despite the prevalence of OCD in contemporary society, the experiences of Matt and John reflect two important features of this disorder. First, that the stereotype of OCD is one of washing and checking behaviours – the compulsions aspect, defined clinically as “repetitive behaviours that a person feels driven to perform”. And that obsessions – defined as “ unwanted, unpleasant thoughts ” often of a harmful, sexual or blasphemous nature – are viewed as obscure, confusing and unrecognisable as OCD.

People who experience obsessional thoughts are therefore frequently unable to identify their symptoms as OCD – and neither , very often, are the experts they see in clinical settings. Due to mischaracterisations of the disorder, OCD sufferers with non-typical, less visible presentations usually go undiagnosed for ten or more years .

When John visited his GP, he was diagnosed with depression. He recalled that the GP concentrated more on the visible effects of his distress - a lack of appetite and disrupted sleeping patterns. The thoughts remained invisible. As he put it:

I don’t know how you’re supposed to tell someone you don’t know that you have thoughts about killing people you love.

Even for those with “textbook” OCD such as my friend Abby, “the compulsion is just the tip of the iceberg”. Abby was able to self-diagnose at the age of 12, when she experienced handwashing and locking door compulsions. She says people still think of her as “Abby [who] likes to wash her hands a lot”.

Now, she tells me, “I realise that I have no interest in washing my hands – I’m a pretty messy person, and I don’t mind other people being messy.” Rather than a love of cleaning, her acts were related to the altogether scarier obsessional thought: “What if I am going to hurt other people?”

Clinical guidelines, such as those provided in the UK by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence , define OCD as being characterised by both compulsions and obsessions. So, why do the difficulties encountered by Matt, John and Abby – of recognising the internal thoughts that dominate their lives – appear to be so common ?

My experience of OCD

From the age of 16, I have also suffered with thoughts that I later came to associate with OCD, but which began as invisible and tormenting. An article I wrote in 2014, entitled The Unseen Obsession , described my experience of having left university midway through my studies due to a single thought that gathered “such power that I even ended up attacking my body in an attempt to eliminate its force”. I wrote:

I have suffered with obsessional thoughts for the last four years, and can safely say that [OCD] is far from being about clean hands.

My obsessions have taken many forms since my teenage years. They began with me wondering whether things really existed, whether my parents were really who they said they were, and whether I wanted to harm – and was a risk to – my family, friends, even my dog.

Many of us know what it is like to ruminate about a person, a conflict, or something else we feel anxious about. But for those with obsessional thoughts (diagnosed or otherwise), this is quite different to simply “overthinking”. As I attempted to explain in my article:

Conversations falter as the thought leaps through your mind. Other topics seem less important, and time to yourself provides space to assess, analyse, and look for evidence of the thought being ‘true’ … [Obsessing] is like fighting: you push and shove your thoughts away and they come back with twice as much force. You spend time trying to avoid them and they pop up everywhere, taunting and mocking your failed attempt at running away.

It took me six months of weekly therapy sessions before I felt able to voice my obsessional thought to my therapist – someone I had known for a number of years. My unwillingness to be open about it was not only tied up with feelings of shame about its taboo content, but also my inability to see such thinking as part of a recognised disorder.

The question of what constitutes OCD, why we understand – and misunderstand – it as we do, as well as my own experience of living with it, led me to study how OCD became recognised and categorised as a mental health disorder .

In particular, my research shows that there are important insights to be gained from the research decisions made by a group of influential clinical psychologists in south London in the early 1970s – shedding light on why so many people, myself included, still struggle to recognise and make sense of our obsessional thoughts.

The origin of the concepts

Categories of mental illness are not stable across time. As medical, scientific, and public knowledge about an illness changes, so does how it is experienced and diagnosed.

Prior to the 1970s, “obsessions” and “compulsions” did not exist in a unified category – rather, they appeared in an array of psychiatric classifications. At the start of the 20th century, for example, British doctor James Shaw defined verbal obsessions as “a mode of cerebral activity in which a thought – mostly obscene or blasphemous – forces itself into consciousness”.

Such cerebral activity could, according to Shaw, arise in hysteria, neurasthenia , or as a precursor to delusions. One of his patients – a woman who experienced “irresistible, obscene, blasphemous and unutterable thoughts” – was diagnosed with obsessional melancholia, a “form of insanity”.

The symptom arose from what Shaw defined as “nervous weakness”, an explanation that reflected the broader 19th-century view that obsessional thoughts were indicative of a fragile nervous system – either inherited, or weakened through overwork, alcohol or promiscuous behaviour (described as “ degeneration theory ”). Notably, Shaw did not mention any form of repetitive behaviour in relation to these verbal obsessions.

At a similar time to Shaw’s writings, Sigmund Freud, the Austrian founder of psychoanalysis, developed his psychoanalytic category of “ Zwangsneurose – translated in Britain as "obsessional neurosis” and in the US as “compulsion neurosis”. In Freud’s writings , the “Zwang” referred to persistent ideas that emerged from a repressed conflict between unresolved childhood impulses (those of love and hate) and the critical self (ego).

Freud’s most famous case study , published in 1909, featured the “Rat Man”, a former Austrian army officer who possessed a variety of elaborate symptoms. In the first instance, he had become obsessed that he would fall victim to a horrific rat-based punishment that had been recounted to him by a colleague. The patient also expressed that if he had certain desires such as a wish to see a woman naked, his already-deceased father “will be bound to die”.

The Rat Man was described by Freud as engaging in a “system of ceremonial defences” and “elaborate manoeuvres full of contradictions” that have been read by some as the behavioural aspects of what would become OCD. However, there are crucial differences between the “defences” of Freud’s client and the compulsions of OCD, including that the former largely involved thinking rather than acting, and were by no means consistent or stereotyped.

This article is part of Conversation Insights The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

The psychoanalytic category of “obsessional neurosis” was adopted and modified in Britain during the first world war, and became a staple – but inconsistently defined – diagnosis in British psychiatric textbooks of the inter-war period. Up to the 1950s, the terms “obsession” and “compulsion” were being used interchangeably in psychiatric writing. The complexity surrounding their meaning is demonstrated in the writings of Aubrey Lewis , a leading figure in post-war British psychiatry, who referred to “obsessional illnesses” as being made up of “compulsive thoughts” and “compulsive inner speech”.

Like Freud, Lewis mentioned the “complex rituals” of the obsessional – such as the patient “who is perpetually putting himself in the greatest trouble to ensure that he never steps on a worm inadvertently”. But he cautioned against “the dangers of associating any kind of repetitious activity with obsessionality”, writing that “it certainly cannot be judged on behaviourist grounds”.

Defining OCD by visible behaviour

OCD began to emerge in the form we recognise it today from the early 1970s – and was established as a formal psychiatric disorder through its inclusion in the third and fourth editions of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (commonly known as DSM-III and DSM-IV) in 1980 and 1994.

The centrality of visible and measurable behaviours in the categorisation of OCD – particularly washing and checking – can be traced back to a series of experiments conducted by clinical psychologists in the early 1970s at the Institute of Psychiatry and the Maudsley Hospital in south London.

Under the direction of South African psychologist Stanley Rachman, the complex array of symptoms contained in the categories of obsessional illness and obsessional neurosis were divided into two: “visible” compulsive rituals, and “invisible” obsessional ruminations. While Rachman and his colleagues conducted a large research programme on compulsive behaviours, obsessions were relegated to the backburner.

For example, in their investigation of ten psychiatric inpatients diagnosed with obsessional neurosis, “compulsions had to be present for entry into the trial and patients complaining of ruminations were excluded” – a statement reiterated throughout subsequent experiments.

Indeed, this study did not merely require patients to exhibit some form of visible compulsion. The ten patients included were exclusively those with “visible handwashing” behaviour, which was viewed as the “easiest” symptom to experiment on. Likewise, the second round of studies only included patients who engaged in visible “checking” behaviour, such as whether a door was unlocked.

In a 1971 paper , Rachman offered his rationale for taking this approach, explaining how “obsessional ruminators raise special problems for the clinical psychologist because of their subjective, private nature”. This, he argued, was in contrast with “the other main feature of obsessional neurosis, compulsive behaviour, which can be approached with greater ease. It is visible, has a predictable quality, and many reproducible analogies in animal research”.

Rachman viewed compulsions as “visible” and “predictable” in large part due to the way clinical psychology had developed as a new profession in Britain, at the Maudsley Hospital in particular, in the decades following the second world war. To differentiate their practice from the existing mental health professions of psychiatry (medically trained doctors specialising in mental health) and psychoanalysis (talking therapy derived from Freud), these early clinical psychologists presented themselves as “ applied scientists ” who brought scientific methods from the laboratory to a clinical setting. Their conception of science was rooted in empiricism – with an emphasis on visibility, measurability and experimentation.

As part of this commitment to empirical science, these clinical psychologists adopted a model of anxiety derived from 20th-century behaviourism. This focus on observable behaviour was viewed as having much greater scientific value than psychoanalysis, which dealt with the “ unverifiable ” and “unscientific” realm of thoughts and thinking.

So, when obsessional ruminations gained a renewed focus in the mid-1970s, it was through this lens of visible compulsive behaviours. Rachman and his colleagues started talking about “mental compulsions” (such as saying a good thought after a bad thought) as “equivalent to handwashing”- rather than focusing on the importance and content of these thoughts in their own right.

In the early 1980s, clinical psychology came under pressure from cognitive psychologists (those concerned with thinking and language) for its reductive focus on behaviour. But despite this move to include cognitive approaches , the centrality of visible behavioural compulsions has continued to characterise perceptions of OCD in cultural and clinical domains.

This is perhaps most evident in media portrayals of the disorder – a critique taken up by cultural scholars such as Dana Fennell , who look at representations of OCD in TV and film.

The archetypal portrayal of OCD has not been helped by the recent publicity given to David Beckham and his extensive tidying . When I ask Abby what she thought about the attention that Beckham’s OCD was receiving in the media, she replies: “It’s so boring. It’s the same presentation that always gets thought of as OCD.”

Limitations to the ‘gold standard’ treatment

This archetypal portrayal of OCD also relates to how it is treated. The “gold standard” treatment in the UK today is the behavioural technique of exposure and ritual prevention (ERP), either on its own or combined with cognitive therapy. ERP gained acceptance from the experiments of Rachman and colleagues in the early 1970s, when they were exclusively working with patients with observable behaviours.

One of their key studies involved patients from the Maudsley Hospital who repeatedly washed their hands. They were told to touch smears of dog excrement and put hamsters in their bags and in their hair, while being prevented from washing for increased lengths of time.

Such experiments were again governed by observability and measurability. The “success” of ERP treatment – and its perceived superiority over psychiatric and psychoanalytic methods – was demonstrated by a reduction in the patients’ visible handwashing behaviour.

Today, if you are diagnosed with OCD by a psychiatrist and given OCD-specialist treatment via the NHS, you will most likely be told to undergo the same kind of ERP procedure that hospital inpatients were experimentally given in the 1970s: touching a set of items that you fear (exposure) while being prevented from engaging in your usual compulsive behaviour.

An identical method is also used when it comes to obsessional thoughts. Patients are asked to identify their worrying obsession, then either expose themselves to provoking situations or repeat the thought in their mind without engaging in “mental compulsions” – such as counting, replacing a bad thought with a good thought, or trying to “solve” the content of the obsessional thought.

It’s certainly true that this form of behavioural therapy can be hugely helpful in the treatment of OCD symptoms. Abby, after undergoing ERP for 14 years, said she had “developed a lot of practices around not giving into my [washing and checking] compulsions”.

I also found the approach beneficial in reducing the threatening quality of my obsessional thoughts. Repeating “I want to hurt my family” or “I don’t really exist” to myself over and over again, without actually trying to solve these issues, reduced the time I spent ruminating.

However, while being a huge advocate of ERP, Abby also observed that “sometimes when I get rid of a compulsion, it doesn’t mean I just get rid of the obsession.” While the “outward compulsions” disappear, “it doesn’t mean my mind stops cycling and mental questioning”.

Some contemporary clinicians have referred to ERP, designed around visible symptom reduction, as a “ whack-a-mole technique ” – you get rid one symptom (obsession or compulsion) and another pops up.

ERP is frequently accompanied with cognitive therapy techniques, such as cognitive restructuring (identifying beliefs and providing evidence for and against them), or being told that obsessions are “just thoughts”, that they are meaningless, and that you do not want to enact them.

Despite the success of cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) and ERP in scientific trials, a major review of evidence in 2021 questioned whether the effects of the approach in treating OCD had been overstated – reflecting the high proportion of OCD cases that are designated as “ treatment resistant ”.

I also believe there are some crucial limitations to contemporary treatments for OCD. Exposure (ERP) techniques stem from a period in which thoughts were not being considered at all by clinical psychologists, while CBT designates the content of obsessional thoughts as unimportant. Matt, like me, has found that CBT “can only take you so far”, explaining:

Part of this was that [CBT therapists] are so committed to the idea that thoughts don’t have meaning … [They] treat your symptom and once those are gone, you should get on with your life. I didn’t find that there was a way of thinking about [my] ruminations in the context of my whole life.

Experiences of alternative treatments

So much of my understanding about OCD has changed since I first wrote about it for Rethink Mental Illness almost a decade ago. Thinking about the historical development and categorisation of OCD has, it turns out, given me a greater sense of ease regarding this widely misunderstood condition. I feel less bound by our current conceptual frameworks, and more able to reflect on what I think is helpful in terms of how to successfully manage my obsessional thoughts.

For example, despite being warned away from psychoanalysis from a young age (my mum is a clinical psychologist, and psychologists are often fervently anti-psychoanalytic!), I have found psychoanalysis incredibly helpful in becoming comfortable with my thoughts.

This is because CBT typically focuses on present symptoms without looking into their meaning or how they relate to your personal history, and this comes into tension with my desire, as a historian, to think about the past. In contrast, psychoanalysis locates obsessional thoughts in history – pointing to childhood as a crucial point of psychic development. I have been able to understand my obsessions as the result of a deep childhood fear concerning the death of my loved ones, from which I developed a rigid desire for control.

As a young teenager trying to determine what was going on with him, Matt went to the public library and took out a Freud reader . He describes this as “the worst possible thing for a 14-year-old to read”, as it made him believe “that I did really have all these [murderous suicidal] impulses and all my fears are true”.

Despite this experience, while training to become a social worker, he “got into psychoanalysis as an alternate way to think about therapy and think about my own experience”. For him, psychoanalysis revealed the opposite to the image of “OCD as handwashing”.

Instead, he says, it focused on the aspects of “obsessionality that are internal”, showing him that the “mind is so powerful that it can produce a lot of imaginary fears”. It also allowed him to see “OCD symptoms as wrapped up with my whole life”.

Particularly profound in psychoanalytic thought is the acceptance of the complexity and unknowability at the heart of human experience. As Jaqueline Rose, professor of humanities at Birkbeck, University of London, wrote: :

Psychoanalysis begins with a mind in flight, a mind that cannot take the measure of its own pain. It begins, that is, with the recognition that the world – or what Freud sometimes refers to as ‘civilisation’ – makes demands on human subjects that are too much to bear.

This idea of “a mind in flight” has helped me think about my obsessions – whether my parents are really who they say they are; am I going to hurt those I love? – as part of a battle for certainty and control that is both unattainable and understandable, considering the world we live in.

The aim of psychoanalytic treatment is not to eradicate symptoms but to bring to light the difficult knots that humans have to deal with. Matt refers to psychoanalysis as acknowledging “a sort of messiness of the mind … I’ve found the psychoanalytic view of accepting your own messiness extremely helpful”. Rose similarly describes psychoanalysis as “the opposite of housework in how it deals with the mess we make”.

In the UK, psychoanalysis has been rejected within NHS service provision. And I believe this is, at least in part, a result of historical critiques levelled at it by clinical psychologists as they developed behaviour therapies to treat OCD in the late 20th century.

‘A lot of emotion and sadness’

While compulsive behaviour such as handwashing and checking is widely perceived as “representative” of OCD, the tormenting experience of having obsessional thoughts is still rarely acknowledged and discussed. The shame and confusion attached to such thoughts, coupled with the feeling of being misunderstood, make this an important issue to address, particularly when misdiagnosis of OCD is so high.

My PhD on the history of OCD has also showed me the ways in which psychological research shapes how we conceive of diagnostic categories – and consequently, ourselves. While psychology’s commitment to objectivity, empiricism and visibility has provided tools that are tremendously useful in the clinic, my research sheds lights on how the often-exclusive focus on visible symptoms has at times trumped the appreciation of the complex experience of having obsessional thoughts.

I first met Matt in 2019 at the first OCD in Society conference, held at Queen Mary University of London, where he was giving a presentation on the “multiple meanings of OCD”. We discussed our own experiences of the disorder, and what we thought that history, psychoanalysis and anthropology could contribute to understandings of OCD.

Matt was 34, and he told me this was the first time he “had ever voiced the internal stuff out loud, and heard other people talk about it”. Recalling how this made him feel, he continued:

I felt a lot of emotion and sadness. The isolation had been such a big part of my life that I had stopped noticing it. Then being out of the isolation was such a relief, it made me realise how bad it had been.

If you are experiencing suicidal thoughts and need support, you can call your GP, NHS 111 , or free helplines including Samaritans (116 123), Calm (0800 585858) or Papyrus (0800 068 4141).

In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Hotline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14. Hotlines in other countries can be found here .

For you: more from our Insights series :

How to solve our mental health crisis

How music heals us, even when it’s sad – by a neuroscientist leading a new study of musical therapy

Unlocking new clues to how dementia and Alzheimer’s work in the brain – Uncharted Brain podcast series

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter .

- Mental health

- Sigmund Freud

- Mental illness

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Mental illness stigma

- Mental health care

- Psychoanalysis

- Insights series

- Obsessive compulsive disorder

- Tackling the mental health crisis

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Coordinator, Academic Advising

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Time changes all concepts. "Obsessive-compulsive disorder" is no exception. In the seventeenth century, obsessions and compulsions were often described as symptoms of religious melancholy. The Oxford Don, Robert Burton, reported a case in his compendium, the Anatomy of Melancholy (1621): "If he be in a silent auditory, as at a sermon, he is afraid he shall speak aloud and unaware, something indecent, unfit to be said." In 1660, Jeremy Taylor, Bishop of Down and Connor, Ireland, was referring to obsessional doubting when he wrote of "scruples": [A scruple] is trouble where the trouble is over, a doubt when doubts are resolved." In his 1691 sermon on religious melancholy, John Moore, Bishop of Norwich, England, referred to individuals obsessed by "naughty, and sometimes Blasphemous Thoughts [which] start in their Minds, while they are exercised in the Worship of God [despite] all their endeavours to stifle and suppress them ... the more they struggle with them, the more they encrease."

Modern concepts of OCD began to evolve in the nineteenth century, when Faculty Psychology, phrenology and Mesmerism were popular theories and when "neurosis" implied a neuropathological condition. Like ourselves, psychiatrists then struggling to understand the mentally ill were influenced by intellectual currents coursing through philosophy, physiology, physics, chemistry and political thought. Obsessions, in which insight was preserved, were gradually distinguished from delusions, in which it was not. Compulsions were distinguished from "impulsions," which included various forms of paroxysmal, stereotyped and irresistible behavior. Influential psychiatrists disagreed about whether the source of OCD lay in disorders of the will, the emotions or the intellect.

In his 1838 psychiatric textbook, Esquirol (1772-1840) described OCD as a form of monomania, or partial insanity. He fluctuated between attributing OCD to disordered intellect and disordered will. After French psychiatrists abandoned the concept of monomania in the 1850s, they attempted to understand obsessions and compulsions within various broad nosological categories. These often included the conditions we now identify as phobias, panic disorder, and agoraphobia and hypochondriasis; certain classification schemes also included sexual perversions, manic behavior and even some forms of epilepsy. Dagonet (1823-1902), for example, considered compulsions to be a kind of impulsion and OCD a form of folie impulsive (impulsive insanity). In this illness, impulsions violentes , irresistibles overcame the will and became manifest in obsessions or compulsions. Morel (1809-1873) placed OCD within the category, " delire emotif " (diseases of the emotions), which he believed originated from pathology affecting the autonomic nervous system. He felt that attempts to explain obsessions and compulsions as arising from a disorder of intellect did not account for the accompanying anxiety. Magnan (1835-1916) considered OCD a "folie des degeneres" (psychosis of degeneration), indicating cerebral pathology due to defective heredity.

While the emotive and volitional views held sway in France, German psychiatry regarded OCD, along with paranoia, as a disorder of intellect. In 1868, Griesenger published three cases of OCD, which he termed " Grubelnsucht ," a ruminatory or questioning illness (from the Old German, Grubelen, racking one's brains). In 1877, Westpahal ascribed obsessions to disordered intellectual function. Westphal's use of the term Zwangsvorstellung (compelled presentation or idea) gave rise to our current terminology, since the concept of "presentation" encompassed both mental experiences and actions. In Great Britain Zwangsvorstellung was translated as "obsession," while in the United States it become "compulsion." The term "obsessive-compulsive disorder" emerged as a compromise.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the diagnostic category, neurasthenia (inadequate "tonus" of the nervous system), engulfed OCD along with numerous other disorders. As the twentieth century opened, both Pierre Janet (1859-1947) and Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) isolated OCD from neurasthenia. In his highly regarded work, Les Obsessions et la Psychasthenie ( Obsessions and Psychasthenia ), Janet proposed that obsessions and compulsions arise in the third (deepest) stage of psychasthenic illness. Because the individual lacks sufficient psychological tension (a form of nervous energy) to complete higher level mental activities (those of will and directed attention), nervous energy is diverted into and activates more primitive psychological operations that include obsessions and compulsions.

Freud gradually evolved a conceptualization of OCD that influenced and then drew upon his ideas of mental structure, mental energies, and defense mechanisms. In Freud's view, the patient's mind responded maladaptively to conflicts between unacceptable, unconscious sexual or aggressive id impulses and the demands of conscience and reality. It regressed to concerns with control and to modes of thinking characteristic of the anal-sadistic stage of psychosexual development: ambivalence, which produced doubting, and magical thinking, which produced superstitious compulsive acts. The ego marshalled certain defenses: intellectualization and isolation (warding off the affects associated with the unacceptable ideas and impulses), undoing (carrying out compulsions to neutralize the offending ideas and impulses) and reaction formation (adopting character traits exactly opposite of the feared impulses). The imperfect success of these defenses gave rise to OCD symptoms: anxiety; preoccupation with dirt or germs or moral questions; and, fears of acting on unacceptable impulses.

As the twenty-first century begins, advances in pharmacology, neuroanatomy, neurophysiology and learning theory have allowed us to reach a more therapeutically useful conceptualization of OCD. Although the causes of the disorder still elude us, the recent identification of children with OCD caused by an autoimmune response to group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection promises to bring increased understanding of the disorder's pathogenesis.

- Rodriguez Lab Site

- Department of Psychiatry

Move it for mental health

Take on the 31 miles in May challenge. Walk, run, cycle, or skip – whatever movement you enjoy.

- Sign up now

Home / Blog / Obsessive Compulsive Disorder – Sophie’s story

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder – Sophie’s story

Sophie is a 26-year-old mental health advocate who has lived with OCD for 11 years. She won a Bill Pringle Award with Rethink Mental Illness for her poem on managing OCD in 2019 and has spoken publicly about her experience on radio and on social media. She is open and vocal about mental health and mental illness because she knows first-hand how isolating and scary it can be in the beginning.

“I just felt guilty all the time about every small thing that, before OCD, wouldn’t really have bothered me at all, and I needed people to tell me I was a good person.”

Obsessive compulsive disorder

OCD is a chronic and potentially debilitating mental health condition in which an individual has uncontrollable (“obsessive”) thoughts or images and compulsive behaviours that can be distressing, frightening and upsetting.

The myths that annoy me – and the truth about them

Ocd is characterized by the desire to keep yourself and/or your space clean..

False. While the compulsion to clean isn’t unheard of among individuals with OCD, cleanliness and OCD aren’t mutually exclusive and the compulsion to clean shouldn’t be considered a choice or desire. Instead, they may feel that it is mandatory in order to find relief.

Everyone is “a little bit OCD.”

False. You cannot be a “little bit” OCD. OCD isn’t an adjective – it’s a complex disorder that affects only 1-2% of people and can be incredibly difficult to manage without the appropriate treatment and care.

OCD can be cured.

False . While this may sound daunting, OCD can be effectively controlled and managed with treatment that suits the individual, allowing them to live a healthy, happy life.

My symptoms When my OCD first started I thought it was simply anxiety, but after doing some research into mental health I realised it was OCD. I felt guilty and paranoid for most of the day with very little relief, overthinking every little bit of whatever thought or image was in my head at the time. I would wake up with palpitations and struggle sleeping because I couldn’t stop ruminating. Logical thought takes a back seat with OCD. When your brain wants to convince you that you’re a bad person, it will give you lots of evidence to try and support it. When you don’t know how to fight back, it can be truly terrifying – you’re defenceless.

My lowest moments I began to worry about leaving the house because I couldn’t determine what situation might trigger another intrusive thought, and that lack of control over your own thought process can completely take over your daily life. When I did leave the house, I would avoid the people or things that were involved in my thoughts, otherwise I struggled to cope. I would experience the same recurring intrusive thought or image for months at a time and would only find (albeit short-lived) peace when I was completely distracted.

I haven’t experienced many compulsions, but my primary one was reassurance-seeking or “confessing.” I constantly felt guilty for my thoughts and at my lowest point, when it became overwhelming, I would find myself asking my mum or partner to remind me that I am a good person, but my brain didn’t seem to want to believe it. It was a terrifying circle – an intrusive thought would come in, I’d panic and ruminate, find someone to “confess” to and the process would start all over again. This lasted for a number of years before I discovered that it was only making my OCD worse.

My way forward After two failed attempts at seeking help via public and private mental health services, I admittedly haven’t been very lucky with professional help and so had to learn to manage my OCD on my own, with the additional support of a select few trusted friends and family. As such, I trained in mental health first aid and undertook a lot of personal research, not only to help myself but to help others like me. I’m the nominated mental health champion at my place of work, though I generally remain a passionate advocate for mental health in all aspects of my life, and I will continue to help others for as long as I possibly can. I also love to write and have found solace in writing about my OCD via reflective poetry.

Why I’m sharing my story When I felt my lowest, when I felt there was no escape, it wasn’t professional help that ultimately helped me but the experiences of others with OCD or who know about OCD. It was the advice of mental health charities, the blog pages of people with lived experience and the never-ending stream of support I had that helped me to help myself. I’m very proud that I can now manage my OCD successfully and, if I ever find myself feeling low or overwhelmed, I know that I can overcome it. I see my OCD as an enduring and experienced reflection of myself – it is no longer a threat.

Your donation will make the difference

Just £10 could help pay for a call to our advice and information line, supporting someone living with mental illness who may be feeling in distress during this time.

Join our newsletter

Sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our events and appeals. Click 'subscribe' to choose your contact preferences

Latest blog posts

“My overriding emotion about my Borderline Personality Disorder diagnosis was relief.” – Claire’s story

16th May 2024

Read article

Benefits and barriers to movement

12th May 2024

Tyler shares how accessibility is the main barrier to movement

Module 5: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Stressor Related Disorders

Case studies: ocd and ptsd, learning objectives.

- Identify OCD and PTSD in case studies

Case Study: Mauricio

Case Study: Cho

Possible treatment considerations for Cho may include CBT or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). This could also be coupled with pharmaceutical treatment, such as anti-anxiety medication or anti-depressants to help alleviate symptoms. Cho will need a trauma therapist who is experienced in working with adolescents. Other treatment that may be helpful is starting family therapy as well to ensure everyone is learning to cope with the trauma and work together through the painful experience.

Link to Learning

To read more about the ongoing issues of PTSD in violent-prone communities, read this article about a mother and her seven-year-old with PTSD .

Think It Over

If you were a licensed counselor working in a community that experienced a high rate of violent crimes, how might you treat the patients that sought therapeutic help? What might be some of the challenges in assisting them?

- Case Studies. Authored by : Christina Hicks for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Desk top. Located at : https://www.pickpik.com/desk-top-desk-notebook-keyboard-desktop-shallow-116155 . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lightning strike. Authored by : John Fowler. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/snowpeak/3761397491 . License : CC BY: Attribution

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Imagery rescripting on guilt-inducing memories in ocd: a single case series study.

- 1 Associazione Scuola di Psicoterapia Cognitiva (APC-SPC), Rome, Italy

- 2 Department of Social and Developmental Psychology Sapienza, University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 3 Department of Human Sciences, Marconi University, Rome, Italy

Background and objectives: Criticism is thought to play an important role in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and obsessive behaviors have been considered as childhood strategies to avoid criticism. Often, patients with OCD report memories characterized by guilt-inducing reproaches. Starting from these assumptions, the aim of this study is to test whether intervening in memories of guilt-inducing reproaches can reduce current OCD symptoms. The emotional valence of painful memories may be modified through imagery rescripting (ImRs), an experiential technique that has shown promising results.

Methods: After monitoring a baseline of symptoms, 18 OCD patients underwent three sessions of ImRs, followed by monitoring for up to 3 months. Indexes of OCD, depression, anxiety, disgust, and fear of guilt were collected.

Results: Patients reported a significant decrease in OCD symptoms. The mean value on the Yale−Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) changed from 25.94 to 14.11. At the 3-month follow-up, 14 of the 18 participants (77.7%) achieved an improvement of ≥35% on the Y-BOCS. Thirteen patients reported a reliable improvement, with ten reporting a clinically significant change (reliable change index = 9.94). Four reached the asymptomatic criterion. Clinically significant changes were not detected for depression and anxiety.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that after ImRs intervention focusing on patients’ early experiences of guilt-inducing reproaches there were clinically significant changes in OCD symptomatology. The data support the role of ImRs in reducing OCD symptoms and the previous cognitive models of OCD, highlighting the role of guilt-related early life experiences in vulnerability to OCD.

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common clinical condition experienced by about 1.2% of the population and with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 2.3% ( 1 , 2 ). OCD produces suffering and seriously compromises patients’ overall quality of life, weighing heavily also on the quality of life of the co-habiting family ( 3 – 6 ).

OCD is characterized by obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are “ recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges, or impulses that are experienced at some time during the disturbance, as intrusive and unwanted, and that in most individuals causes marked anxiety or distress” . Compulsions are “repetitive behaviors … or mental acts … that the individual feels driven to perform in response to an obsession or according to rules that must be applied rigidly. The behaviors or mental acts are aimed at preventing or reducing anxiety or distress, or preventing some dreaded event or situation” ( 7 ).

A crucial role in OCD onset and maintenance has been attributed to responsibility and guilt by Rachman ( 8 – 10 ) and by Salkovskis ( 11 ). Results from different studies have corroborated this thesis. OCD patients experience more intense guilt and higher responsibility when compared to other people ( 12 – 17 ). OCD patients are characterized by high levels of fear of guilt ( 18 – 20 ). Takahashi et al. ( 21 ) found similar brain activity between OCD patients when exposed to stimuli eliciting OCD symptoms, and nonclinical subjects when exposed to stimuli eliciting guilt. Moreover, studies have corroborated the hypothesis that compulsions are aimed at reducing or preventing responsibility and guilt. Lopatcka and Rachman ( 22 ) and Shafran ( 23 ) have shown that OCD symptoms diminish when the level of responsibility is lowered, by asking to put an agreement in writing, so the responsibility for any consequence for not carrying out the compulsions was of the experimenter or by varying the presence or absence of the experimenter during the behavioral task. Cognitive Therapy Interventions (e.g., Socratic dialogue, pie-technique, double-standard technique, and the court technique) aimed at reducing the responsibility and consequentially the risk of being guilty ( 24 – 26 ) lead to a significant reduction of OCD symptoms. Additionally, when responsibility and fear of guilt are induced experimentally, especially when associated with the fear of making mistakes, nonclinical participants begin to behave in an obsessive-compulsive–like way and those with OCD show an increase in obsessive-compulsive behaviors ( 16 , 18 , 27 – 29 ). Arntz and colleagues ( 30 ) experimentally induced the sense of responsibility and the fear of guilt in OCD patients, in other-clinical and nonclinical groups. Checking behaviors were higher in OCD patients than in the other two groups. This result suggest that OCD patients, regardless the subtype, are particularly sensitive to responsibility and fear of guilt. One might ask if checking behaviors are aimed at reducing or preventing responsibility and guilt, while washing behaviors are only aimed at reducing or preventing disgust and not responsibility and guilt. According to Bhikram et al. [( 31 ), 300] “ exaggerated and inappropriate disgust reactions may drive some of the symptoms of OCD, and in some cases, may even eclipse feelings of anxiety .” Two questions arise: What is the relationship between guilt and disgust? Is it possible that guilt implies the activation of disgust resulting in washing behavior? Some studies ( 32 , 33 ) found the so-called Macbeth effect “ that is, a threat to one’s moral purity induces the need to cleanse oneself … physical cleansing alleviates the upsetting consequences of unethical behavior and reduces threats to one’s moral self-image .” [( 32 ), 1451]. This effect has not been detected in some studies ( 34 ), but Reuven et al. ( 35 ) found it particularly prominent in OCD. Ottaviani et al. ( 36 ) found that in nonclinical participants, the induction of a specific sense of guilt, the deontological guilt, which is related to having transgressed moral norms, regardless of whether someone has been harmed ( 37 , 38 ) elicits obsessive-like washing behaviors, which reduce guilt and increase positive emotions ( 39 ).

It is plausible, therefore, that all obsessive symptomatology, not only checking compulsions, are the expression of an intense concern for one’s own morality, in particular for the deontological morality ( 37 , 38 , 40 ).

Such moral concern is found in Ehntholt’s and colleagues work ( 41 , 779):

“OCD patients reported more fear that others would see them in a completely negative manner, e.g., others would “loathe” or “despise” them if it was possible that they would cause others harm or problems, suggesting a sensitivity to blame and criticism. Our findings that those in the OCD group are more sensitive to the criticism of others is also consistent with Turner, Steketee & Foa ( 1979 )” .

In line with these results are those from a small pilot study from Mancini and colleagues ( 42 ), where OCD participants, compared to non-OCD, showed higher distress when exposed to Ekman’s Pictures of Facial Affect of contempt, anger, disgust, if requested to imagine that such expressions were addressed to them and, above all, that they deserved them. Moreover, OCD participants declared, more than other participants, that they reminded them the faces of the parents, or one of the two, and their parents’ facial expressions at a time when they were being reproached and experiencing intense distress. In fact, families of obsessive patients are described as demanding and critical [see ( 43 – 45 )]. In a recent study, Basile et al. ( 46 ) found that OCD patients reported significantly more painful memories of guilt-inducing blame/reproach compared to a non-OCD group.

An interesting observation of the type of discipline used by parents of future OCD patients is the threat to the continuity of the relationship itself ( 47 ). Clinical observations show that in cases of reproach, parents of future OCD patients withdraw love, ignore the child and are not prone to forgive ( 45 ). It is plausible that these experiences have taught the patient that a small mistake is enough to receive serious, aggressive, contemptuous, demeaning reproaches by significant figures such as parents, without having the possibility to justify oneself or be forgiven, and that his/her behavior can determine the end of such significant relationships ( 45 ). Briefly, the expectation that guilt has catastrophic consequences may derive from these kinds of experiences. Along the same lines, according to Pace et al. ( 43 ), obsessive behaviors may be considered as strategies used by the child to avoid criticism and obtain approval. According to Cameron ( 48 ), obsessive behaviors may be created as methods to obtain the parents’ satisfaction and avoid being criticized. Some studies suggest that obsessions could also be intrusive mental images that evoke adverse early experiences ( 49 ), and that obsessive thoughts have implications for a person’s sense of self ( 50 ) as well as such guilt-inducing experiences.

It is possible to modify the meaning attached to past adverse or traumatic events, especially childhood or adolescence events, intervening in those events’ memories through imagery rescripting (ImRs). ImRs is an experiential technique that has shown promising results in different clinical disorders ( 51 , 52 ). It has been theorized that the way ImRs works is by changing the meaning attached to memories ( 53 ).

ImRs has been employed in OCD by Veale et al. [( 54 ), 230] who stated that:

“Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), including exposure and response prevention, remains the psychological treatment of choice for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder … However, a significant proportion of cases still fail to respond to CBT … This has prompted the search for new target areas for intervention, in the hope that outcomes can be improved.”

Veale et al. ( 54 ) examined the efficacy of one single ImRs session, as a standalone intervention, where intrusive images linked to aversive memories were present. The presence of intrusions linked to aversive past events has been detected in many studies ( 49 , 55 , 56 ). In the study of Veale et al. ( 54 ) after ImRs, nine patients showed a reliable change and seven a clinically significant change at the 3-month follow-up session. A major change was detected three months after the end of treatment. More recently, Maloney et al. ( 57 ) investigated the efficacy of ImRs as a treatment for OCD cases that were not responsive to standard exposure and response prevention. In the study, the authors investigated the efficacy of 1–6 ImRs sessions in 13 OCD patients who experienced intrusive distressing images associated with OCD. Of those 13 patients, 12 reached an improvement of at least 35% in OCD symptoms. Six patients reached the improvement after only a single ImRs session, whereas the rest required 2–5 ImRs sessions. The results of both studies were very promising, suggesting the opportunity to carry out other studies on ImRs’ efficacy on OCD.

Starting from the work of Veale et al. ( 54 ) and considering the role of guilt-inducing reproaches in the development of the fear of guilt, we hypothesize that an intervention of ImRs on childhood memories of guilt-inducing reproach in OCD people could reduce current obsessive symptoms.

The main hypothesis that we wanted to test is that after an intervention of ImRs, OCD symptoms—regardless the subtype—would decrease and that change would be maintained.

We also hypothesize a reduction in both the fear of guilt and in the propensity to disgust.

In addition we measured the effect of ImRs on anxiety and depression, to control the effect of ImRs on these two emotions. We expected that the effect of ImRs would be less than the one on specific obsessive symptoms, due to the specific nature of ImRs intervention on memories for OCD.

The study is centered on a single-case series experimental design. According to Lobo et al. ( 58 ), in single-case studies, indexes are assessed repeatedly for each participant across time. The different interventions are defined as “phases,” and one phase is considered as a baseline for comparison. In single case studies, a control group is not required because each participant represents a proper control.

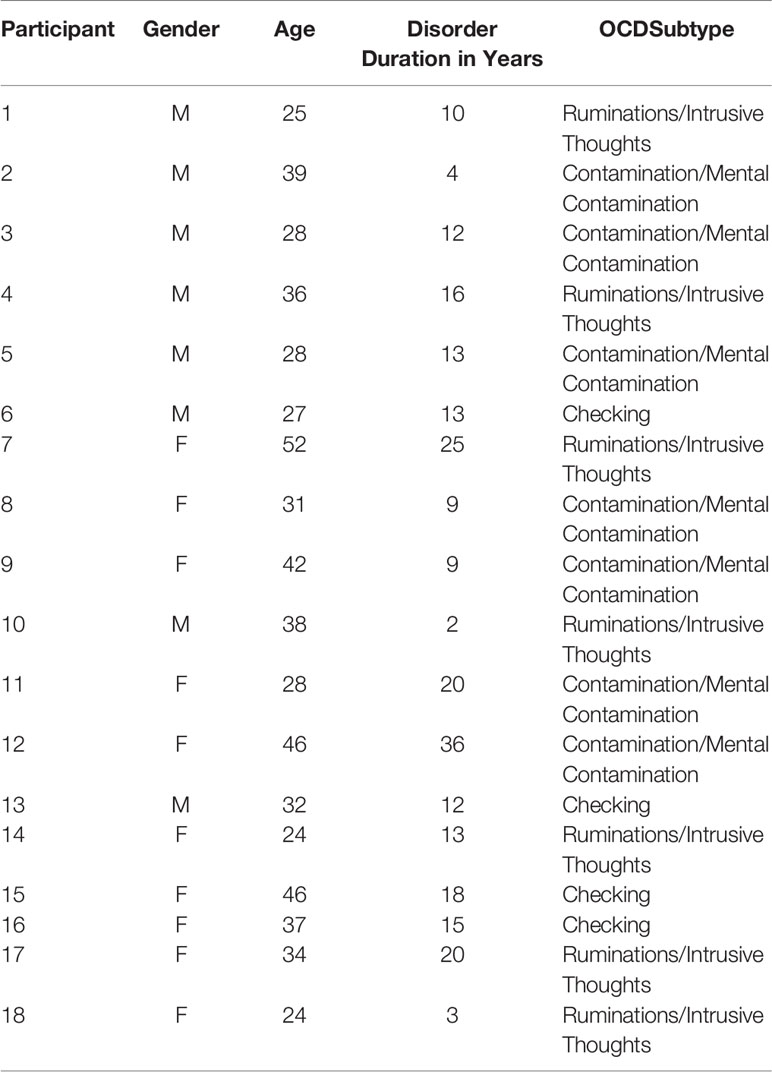

Participants

A sample of 18 participants seeking treatment for OCD at “Studio di Psicoterapia Cognitiva” in Rome was enrolled for the study. At an early stage, recruitment was attempted through the Internet and flyers’ announcements, but these modalities were ineffective.

Twenty-four people, seeking treatment voluntarily, were asked to enroll in the study and two refused to take part. Of the 22 participants who accepted, 18 completed the procedure, two dropped out and two were excluded due to a change of psychopharmacological drugs during the procedure.

Approximately two thirds had received prior treatment and were not awaiting other treatments, but a few started a treatment after the last follow-up. Nobody was in treatment during the 9 months of the experimental trial.

The participants were not preselected for showing a relevant memory, but all showed at least one memory, Table 1 reports gender, age, disorder duration in years, and OCD subtypes for each subject. Mental contamination refers to that form of contamination arising from “ experiencing psychological or physical violation. The source of the contaminations is a person, not contact with an inert inanimate substance ” ( 4 , 59 ).

Table 1 Clinical summary of participants.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants were included if they were aged 18–65 years with an OCD diagnosis according to DSM-5 ( 7 ) and a score on the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) higher than 18.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded if they were having ongoing psychotherapy, if psychotherapy had ended less than three months prior to the beginning of the procedure or if psychopharmacological drugs had been changed in the last three months or during the procedure.

To monitor for possible changes in drug therapy, at each assessment meeting the participants were asked whether the therapy had remained constant. The participants received the same procedure but if there was a change in drugs their data were not considered in the analysis because we could not be sure whether the effect on symptoms was attributable to the intervention or to the change in drugs.

A further exclusion criterion was a comorbid diagnosis of psychosis, schizotypy, mania, borderline personality disorder, alcoholism, impaired cognitive function (assessed on the basis of the educational level and with a clinical interview) or dissociation symptoms [a score higher than 30 on the Dissociative Experiences Scale: ( 60 )].

1. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 [SCID-5; ( 61 )] is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview, aimed at assessing diagnoses according to the fifth edition of the DSM [DSM-5; ( 7 )].

2. The Dissociative Experiences Scale [DES; ( 60 )].

The DES is a 28-item self-report questionnaire that assesses forms of dissociation. The scores range from 0 (never) to 100 (always). The DES has proven to have adequate test–retest reliability as well as a good internal consistency, and good clinical validity ( 62 , 63 ). A cutoff score of 30 to detect dissociative psychopathology in clinical sample is recommended ( 64 , 65 ).

3. The Yale–Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale [Y-BOCS; ( 66 )].

4. The Y-BOCS is a 10-item clinician-rated scale that assesses the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and the effectiveness of treatment. The clinician attributes a score from 0 (absence of symptoms) to 4 (very severe symptoms). The total score is in a range from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate more severe OCD symptomatology. The scale has proven to have high internal consistency [alpha = 0.82; ( 67 )].

5. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory [OCI-r; ( 68 )].

The OCI-r is an 18-item self-report questionnaire, which assesses the severity of OC symptoms on the 5-point Likert scale. There are six subscales (washing, checking, ordering, obsessing, hoarding, and mental neutralizing). The total score ranges from 0 to 72. The OCI-r Italian version ( 67 ) showed good internal consistency as well as a convergent and divergent, and criterion validity [alpha = 0.85; ( 67 )].

6. The Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition [BDI-II; ( 69 )]. The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report, measuring the severity of several components of depression. The Italian version of the BDI-II has proven to have good internal consistency [alpha = 0.80; ( 70 )] as well as good convergent and divergent and criterion validity ( 70 , 71 ).

7. The Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI; ( 72 )]. The BAI is a 21-item self-report, that measures the severity of anxiety. The BAI Italian version shows good internal consistency [alpha = 0.89; ( 70 )] as well as good convergent and divergent, and criterion validity ( 70 , 73 ).

8. The Fear of Guilt Sclale [FOGS; ( 19 , 20 )]. FOGS is a 17-item self-report scale, ranging from 0 to 7, assessing the extent to which a person values and fears guilt and how she/he behaves in relation to guilt. The FOGS consists of two factors: Punishment (drive to punish oneself for feelings of guilt) and Harm Prevention (drive to proactively prevent guilt). The FOGS demonstrated strong internal consistency as well as convergent and divergent validity [alpha = 0.92; ( 20 )]. It also significantly predicted OCD symptom severity over measures of neuroticism, depression, trait guilt, and inflated responsibility beliefs ( 19 ).

9. The Disgust Propensity Questionnaire [DPQ; ( 74 )]. DPQ is a 33-item scale aimed at assessing the individual’s propensity for disgust. The participant expresses the agreement on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”). The total score range is from 0 to 132. The questionnaire has been proven to have a one-factor structure, as well as good internal consistency [alpha in the range 0.85–0.91; ( 74 )] as well good test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.85) and also construct validity ( 74 ).

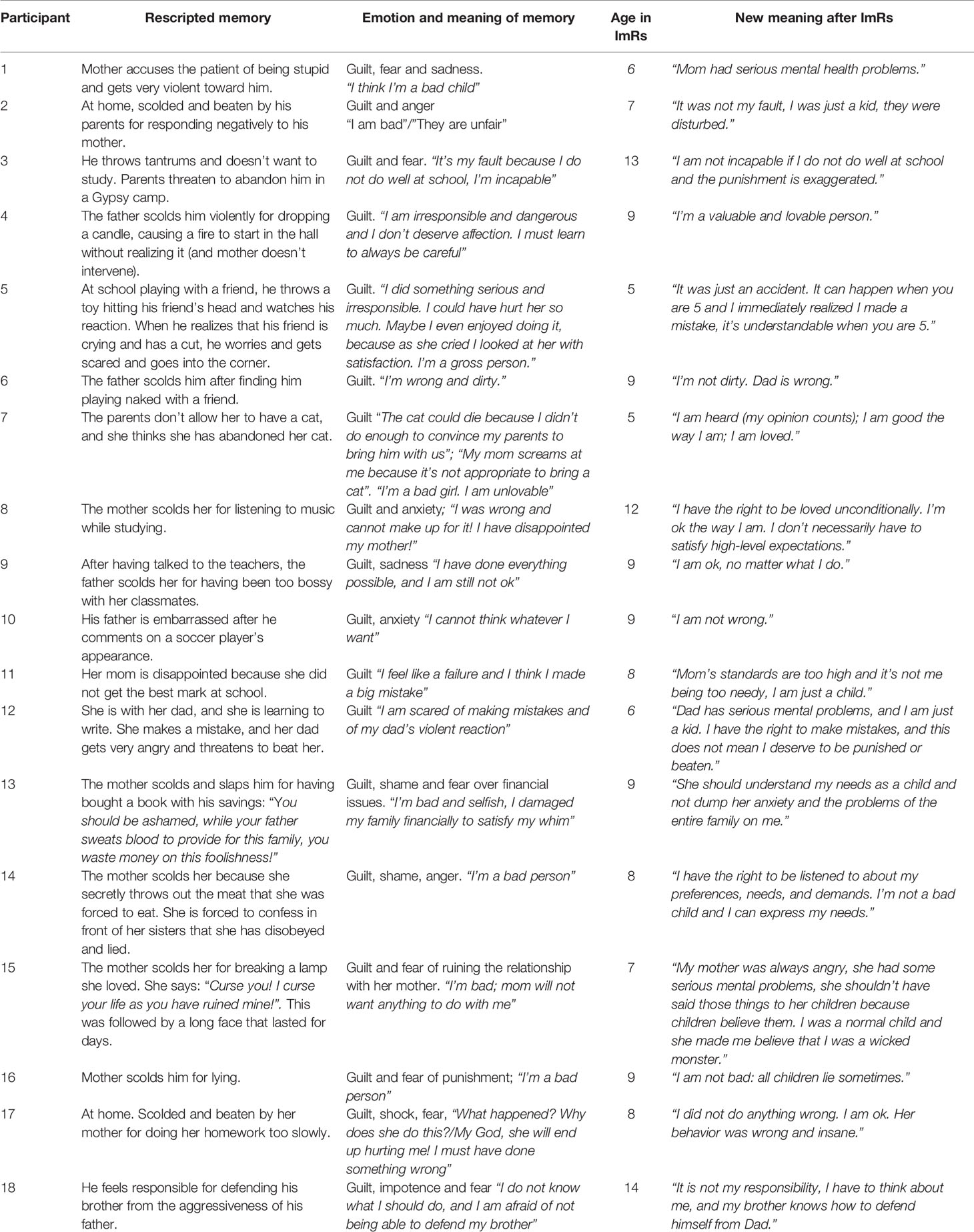

Participants who accepted to be enrolled in the study signed an informed consent form. In an initial clinical interview, we checked for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were assessed through clinical interview and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5: 61). Diagnostic interviews were conducted by experts who had a master’s degree in psychodiagnosis, were trained to administer the SCID and conducted the interview according to the reference manuals; they were also blind to the study’s hypothesis. In the second session we measured the obsessive symptoms’ subtype and severity; and in the third meeting we ran an ad hoc interview on memories (see Appendix) in order to detect guilt-inducing reproaches memory that could be examined in the three following ImRs sessions. The selection of the memories was driven by the aim of intervening on generic memories of guilt-inducing reproaches not necessarily related to the current symptomatology. We selected memories in a different way from Veale et al. ( 54 ), where the authors selected participants who experienced intrusive imagery as part of their OCD, which was considered by the participant and assessor to be emotionally linked to memories of past aversive events, and from Maloney et al. ( 57 ), where intrusive imagery was selected because it was associated with OCD and considered by the patient to be linked to memories of aversive events.

We asked participants to recall reproaches similar to those which had been found by Basile et al. ( 46 ).

As already stated, we found, for each participant, generic memories of guilt-inducing reproaches, and so no one was excluded for this reason.

In particular, we focused on generic reproach experiences not necessarily related to the symptom domain. For example, a childhood memory selected by an OCD patient with washing symptoms was not directly related to being reproached for being dirty, but rather was independent of the symptom domain. The first criterion used for the memory’s selection was the earliest childhood memories reported by the participants, the second was the most intense memory from an emotional point of view.

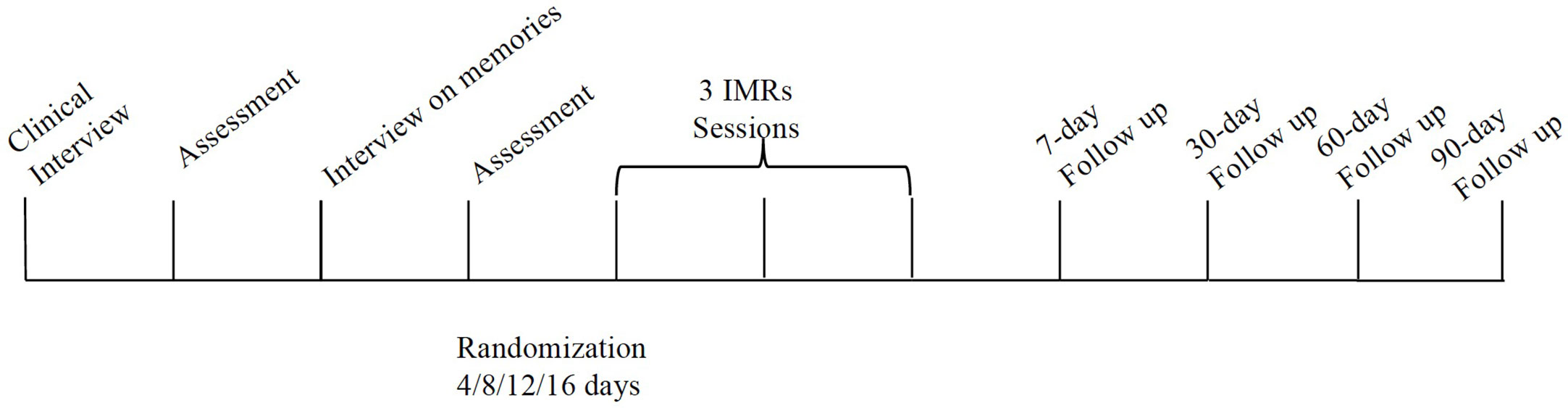

Participants received a symptoms’ assessment and then as Veale and colleagues ( 54 ) did were randomized to 4, 8, 12, or 16 days of symptom monitoring before receiving ImRs (4 participants in the condition of 4 days monitoring, 5 in the condition of 8 days monitoring; 4 in the condition of 12 days monitoring; 5 in the condition of 16 days monitoring). Within the three 45-min ImRs treatment sessions, the previously selected memory was addressed and rescripted. For each participant, we selected one memory that was rescripted during the three sessions. The clinicians who ran the ImRs sessions were all experts in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for OCD (with an average of 10 years of experience) and in imagery techniques and the adherence to the protocol was supervised by three trainers and supervisors in ImRs. Based on the work of Veale et al. ( 54 ), we carried out each ImRs session according to Arntz’s three-stage technique ( 75 ), adapting it to the Schema Therapy suggestions ( 76 ) for patients with difficulty meeting their needs autonomously. The technique consisted of a first phase in which the patient was invited to relive the memory with his/her eyes closed, from the standpoint of their childhood self. In the second phase, the patient looked at the same event as an adult, tried to detect the unmet need of his/her childhood self and proposed an imaginative change (the rescripting) aimed at satisfying the unmet emotional needs. In the third phase, the patient as a child looked at the event with the changes proposed by the adult. In line with the procedure, if the patient could not find a solution to the unmet need in the second phase, the therapist then suggested some interventions or asked the patient to include the therapist into the image of their childhood, in order to meet the patient’s needs. The traditional protocol was employed as proposed by Arntz—“ part of rescripting involves a secure adult that meets the child’s needs to be reassured and comforted ” [( 53 ), 467]. By unmet need we mean the core emotional need, whose unfulfillment is the cause of the emotional sufferance. The intervention of the adult in the second phase, and the rescripting, are stimulated by the clinician’s questions: “Is there anything you would like to do?” “Is there anything that should be done?”

After each session, as per the traditional protocol ( 53 , 77 ), the patient listened to a recording of the session between one session and the next. Data were not collected between sessions. After clinical intervention, four follow-up assessment sessions (at 7, 30, 60, and 90-day intervals, respectively) were held, as in Veale et al. ( 54 ).

An outline of the procedure is shown in Figure 1 and the procedure has been approved by the ethical committee of Guglielmo Marconi University.

Figure 1 Procedural timeline.

Appendix Table 1 shows a summary of the contents of the rescripted memories. It reports the event and the emotion experienced, the participant’s age in the memory and meaning attached to the memory, verbally expressed by the participant. The “Emotion and meaning of memory” refers to the answers that participants gave when, in the first phase of rescripting, the patient was invited to relive the memory with his/her eyes closed, from the standpoint of their childhood self. In that phase of the technique they were asked: “What is happening?” “What do you feel?” “What do you think about the situation?” and the therapist just wrote down the participant’s verbal expression. “New meaning” after the ImRs refers to the event’s appraisals after the third intervention and the answers to the question the therapist asks “What do you think about the situation?,” which is asked in the third phase of rescripting, when the patient as a child looked at the event with the changes proposed by the adult in the second phase of the technique.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 25, Inc., Chicago, IL) for parametric and nonparametric analyses, while the Leeds Reliable Change Indicator was used to calculate change indexes ( 78 , 79 ).

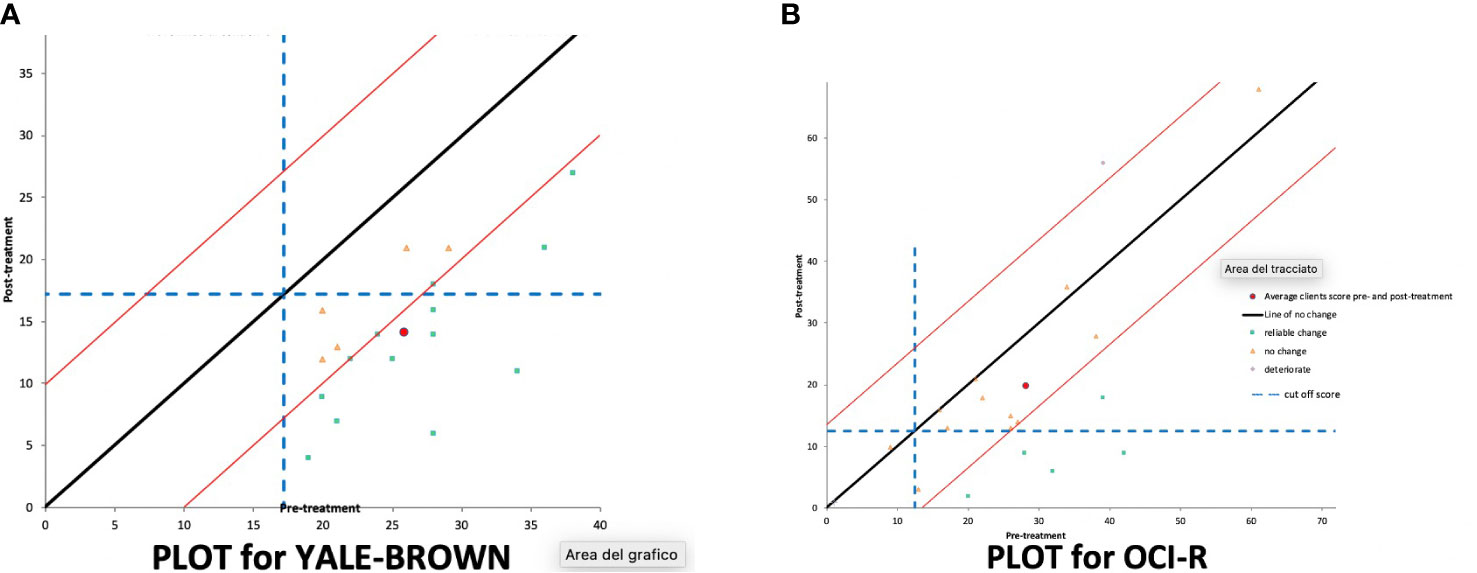

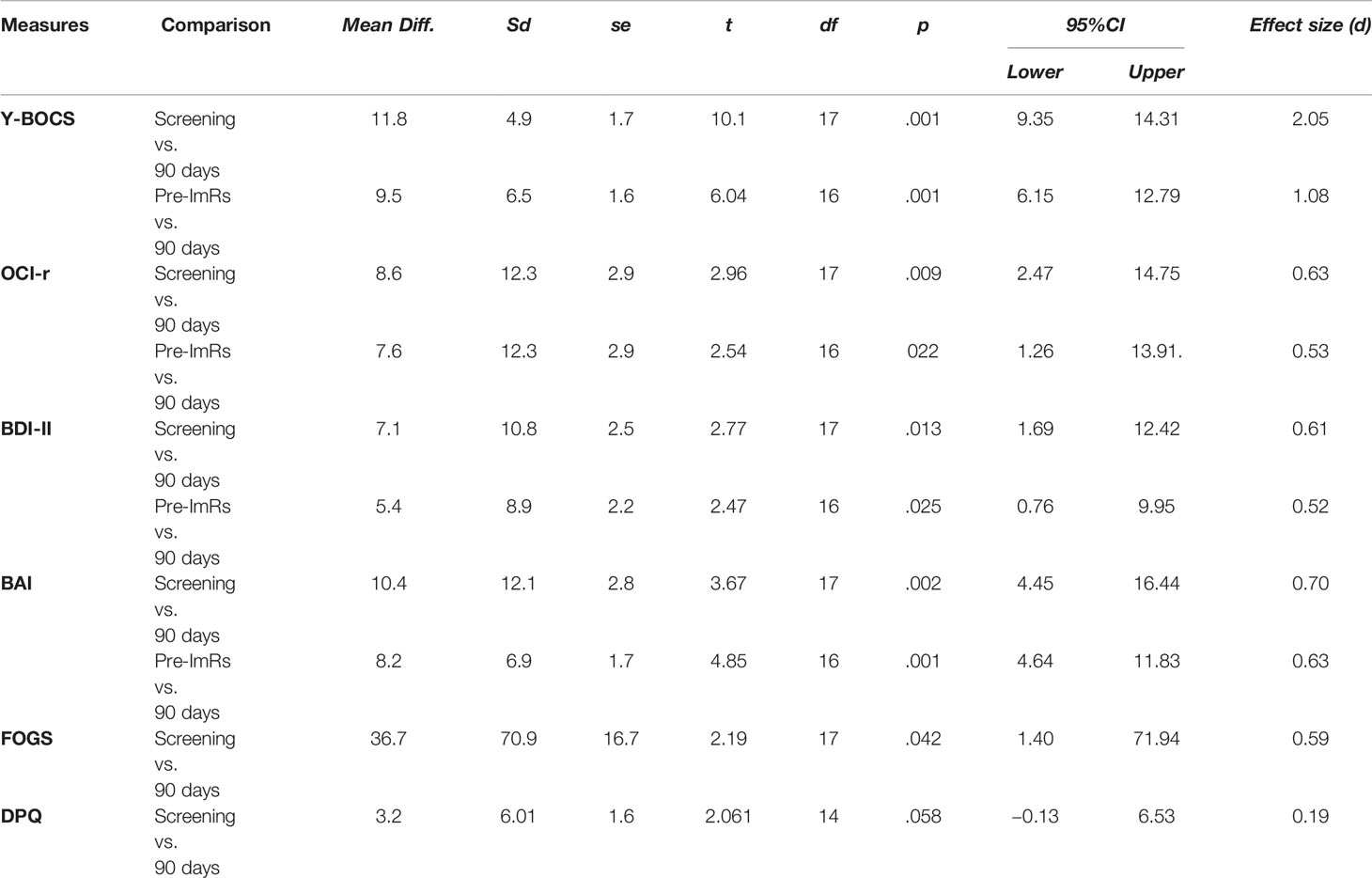

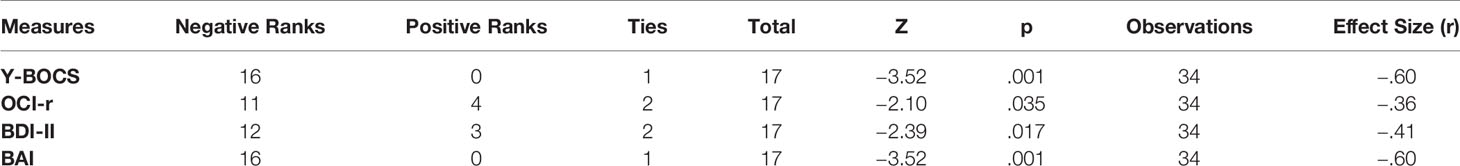

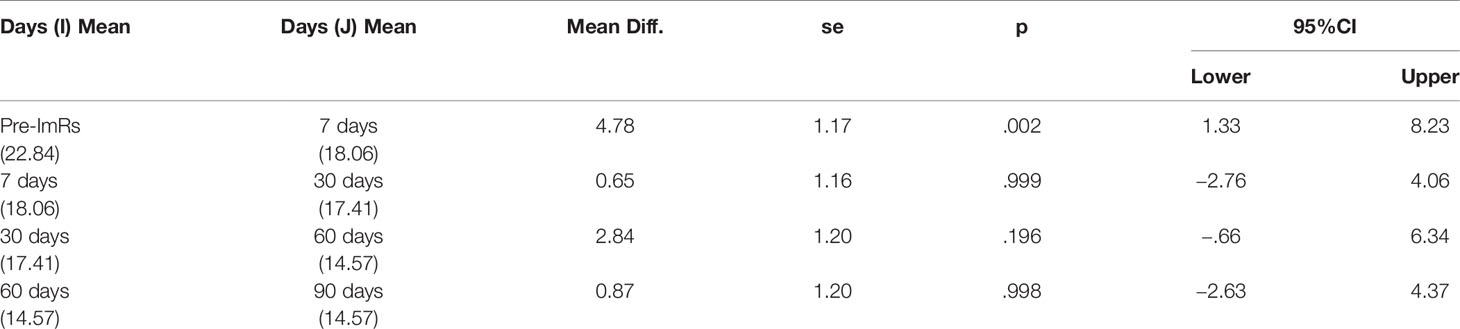

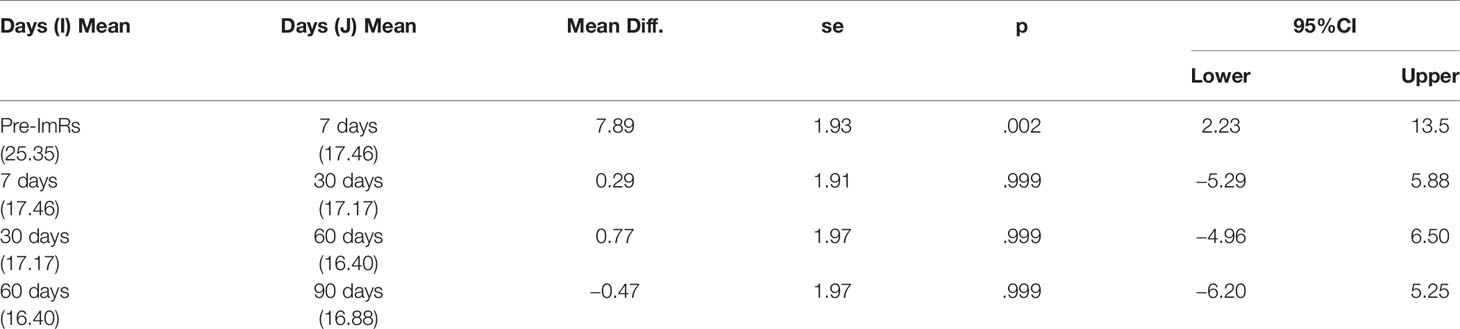

Beyond initial descriptive analyses, we calculated reliable and clinically significant change indexes for all clinical measures (Y-BOCS, OCI-r, BAI, and BDI-II). Like Veale and colleagues ( 54 ), we considered the over-time change of the Y-BOCS total score. In particular, we considered indexes related to (a) reliable change and (b) clinically significant change ( 80 ). We evaluated the change in scores from screening to 90-day follow-up of at least 2 standard deviations (SDs) from the original mean. A reliable change was identified by the Leeds Reliable Change Indicator as a 10-point reduction on the Y-BOCS. A clinically significant change is the condition where criterion a was satisfied and the participant’s scores were under the clinical cutoff (for the Y-BOCS, score less than 17). As proposed by Veale and colleagues ( 54 ), we considered Pallanti’s asymptomatic criterion ( 81 ), which refers to an approximate total absence of OCD symptoms. The asymptomatic criterion for OCD has been defined as a recovery on the Y-BOCS (score 7 or less). The same analysis was performed for the OCI-r total score.

Paired samples t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests on the different measures (e.g., Y-BOCS, OCI-r, BAI, and BDI-II) were also performed between screening and 90-day follow-up, as well as, between pre-ImRs baseline and 90-day follow-up.

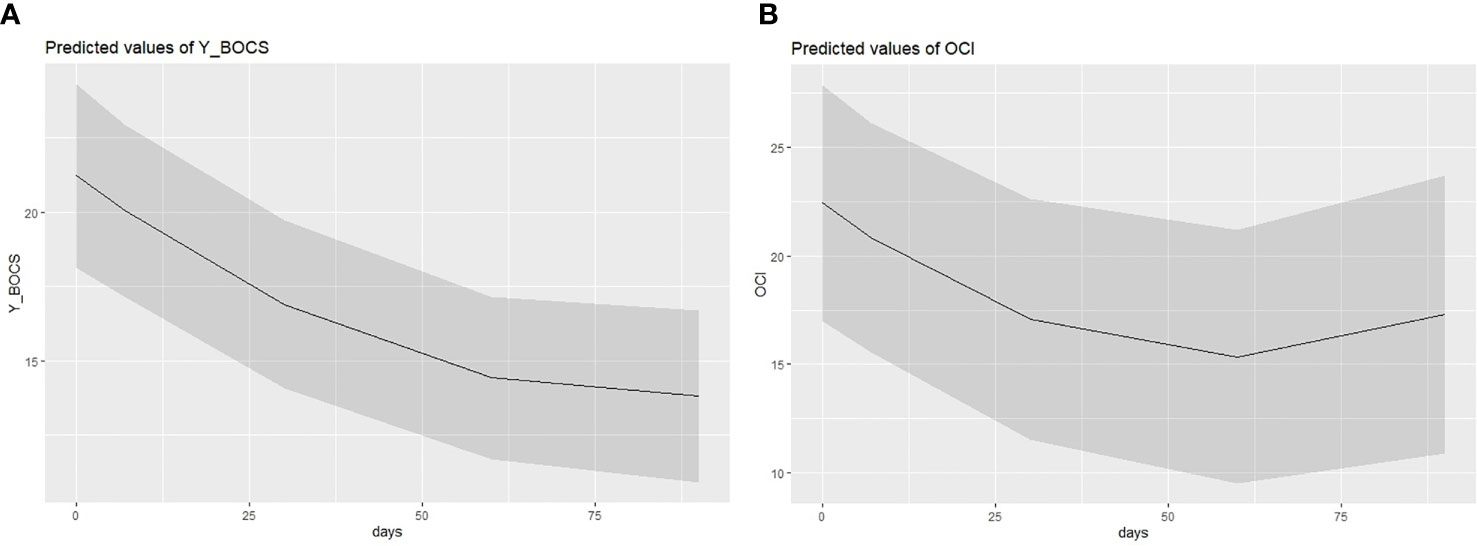

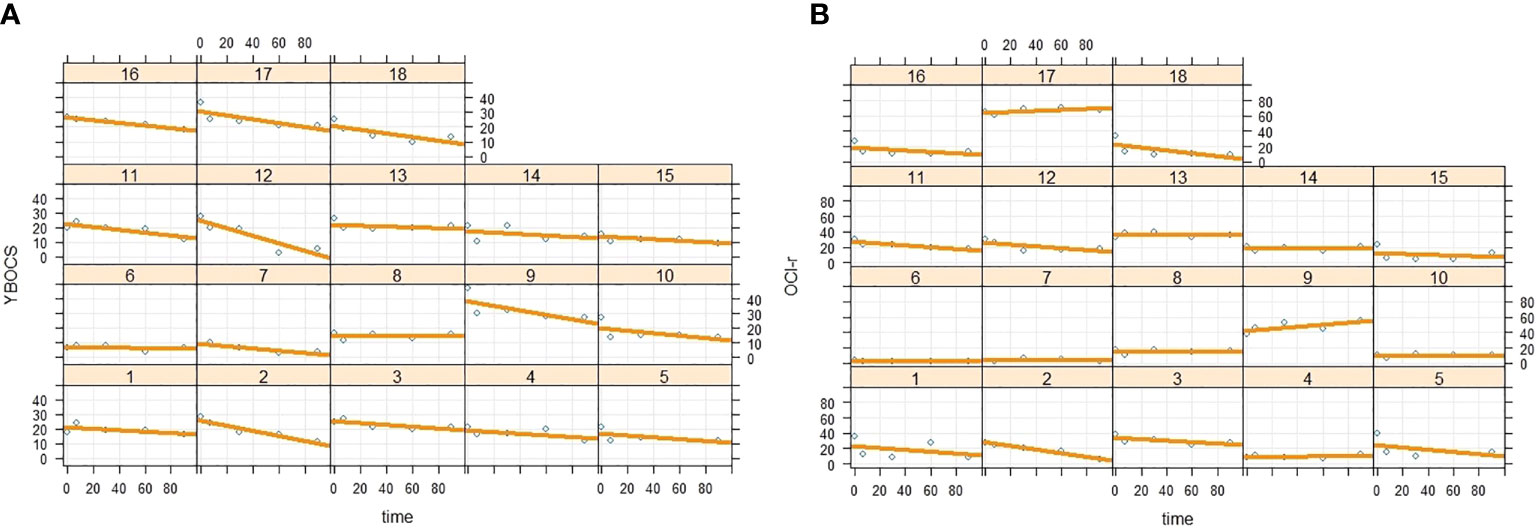

Afterward, two distinct linear mixed regression models were performed in order to test the fixed effect of the ImRs treatment on the OCD-related measures (i.e., Y-BOCS and OCI-r) and its random variations across patients. The strength of these kinds of models’ lies in the fact that the random variability of the parameters is also taken into account. Thus, the analysis allowed us to estimate whether the OCD-related symptoms decreased after the ImRs intervention and across the different measurement times, simultaneously considering the random variability of such hypothesized reduction for each of the 18 patients. Before running the analyses, it was necessary to carry out a restructuring of the data. Thus, we changed the data matrix from a wide format to a long format. Afterward, we stacked the scores of the Y-BOCS and OCI-r, obtained at each measurement time, into two distinct variables. These variables were in turn associated with an indicator of the measurement times (i.e., pre-ImRs baseline, 7-, 30-, 60-, and 90-day follow-up). Since we were interested in testing the effectiveness of the ImRs intervention, we focused our attention on the observed changes starting from the pre-ImRs baseline. Thus, the indicator variable was centered on the pre-ImRs assessment by coding such time point as 0. In this way, we were able to test the fixed effect of the time and the related random variability of intercept and slope. Moreover, we also estimated the quadratic effect of the time to test whether the differences that had emerged were in the extremes of the experimental region or inside it. These analyses were performed with the lme4 package ( 82 ) using RStudio ( 83 ), a graphical interface for R software. Both models were tested using a restricted maximum likelihood method (REML).

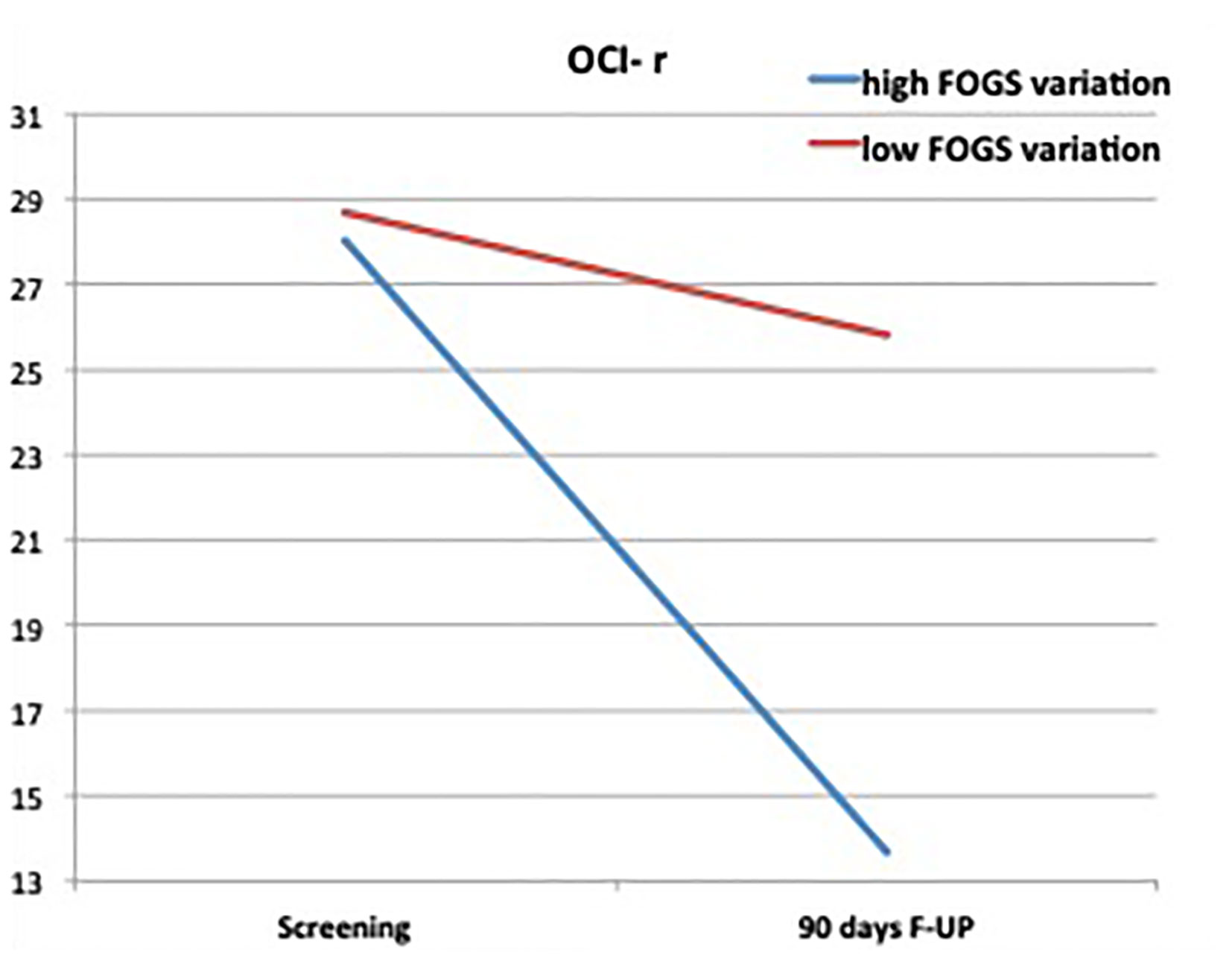

Then, a mixed ANOVA was conducted to determine the extent to which levels of change on fear of guilt (low vs. high) affected ImRS intervention on obsessive symptoms.

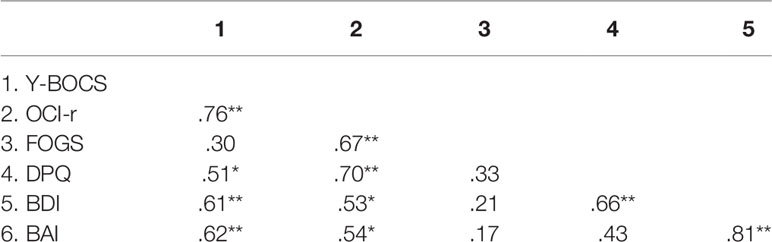

Finally, we computed intercorrelations among all the variables investigated at the 90-day follow-up in order to explore the relationships among them after the ImRs intervention.

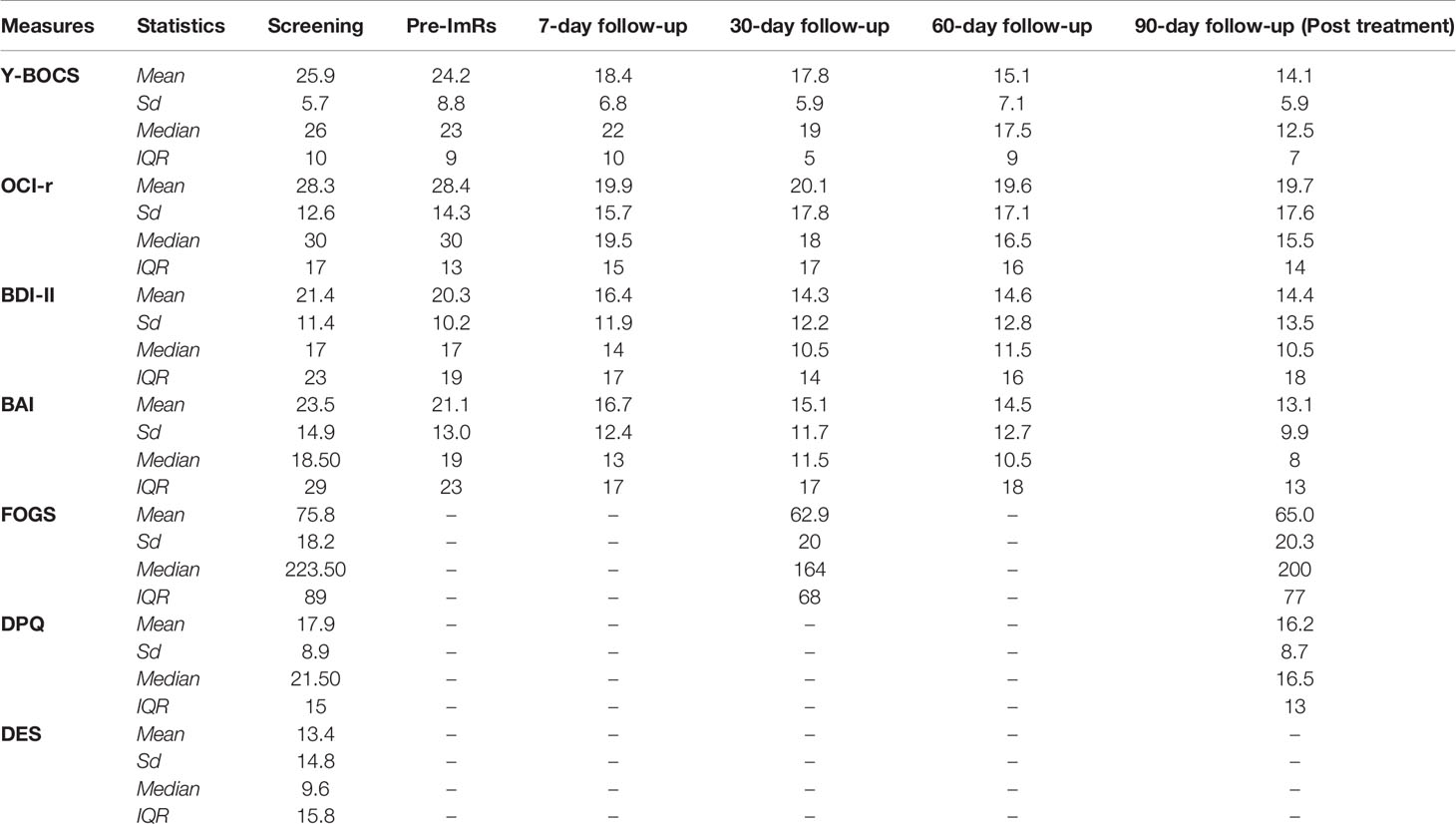

First, we explored the structure of our data by means of some descriptive statistics (see Table 2 ). Thus, we computed the mean and the related standard deviations of each measure at the different detection times. Moreover, because of the reduced size of the sample under examination, we also computed the median and considered the interquartile range as a measure of the data dispersion from their central value.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics: Means, Standard Deviations, Median and Inter-Quartile Range (IQR) of the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory revised (OCI-r), Beck Depression Inventory - Second Edition (BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Fear of Guilt Scale (FOGS), Disgust Propensity Questionnaire (DPQ), Dissociative Experience Scale (DES).

Clinical Response to Imagery Rescripting

At the 3-month follow-up, 14 of the 18 participants (77.7%) achieved an improvement of ≥35% on the Y-BOCS, defined by Farris ( 84 ) and Mataix-Cols et al. ( 85 ) as corresponding to the most predictive of treatment response. Based on the results of the retrospective investigation of Tolin et al. ( 86 ), that is, the reduction criterion of at least 30% on the Y-BOCS as optimal for determining clinical improvement, it is possible to say that 15 participants (83%) reported a significant improvement.

Eleven of the 18 participants (61%) reached an absolute raw score of 12 or less on the Y-BOCS measure, which is identified by Lewin et al. ( 87 ) as optimal for predicting remission in a clinical setting. Based on Pallanti’s asymptomatic criterion ( 81 ), four participants reached the asymptomatic criterion (7 or less on Y-BOCS) at 90-day follow-up.

Reliable and Clinically Significant Change on the Y-BOCS

Of the whole sample, 13 patients reported a reliable change, with 10 of them revealing a clinically significant change on the OCD clinical measure (RCI = 9.94) using criterion A. The average scores from pretreatment and post-treatment met the criteria for reliable and clinically significant change.