Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2022

Effect of sleep and mood on academic performance—at interface of physiology, psychology, and education

- Kosha J. Mehta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0716-5081 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 16 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

66k Accesses

11 Citations

39 Altmetric

Metrics details

Academic achievement and cognitive functions are influenced by sleep and mood/emotion. In addition, several other factors affect learning. A coherent overview of the resultant interrelationships is essential but has not been presented till date. This unique and interdisciplinary review sits at the interface of physiology, psychology, and education. It compiles and critically examines the effects of sleep and mood on cognition and academic performance while including relevant conflicting observations. Moreover, it discusses the impact of several regulatory factors on learning, namely, age, gender, diet, hydration level, obesity, sex hormones, daytime nap, circadian rhythm, and genetics. Core physiological mechanisms that mediate the effects of these factors are described briefly and simplistically. The bidirectional relationship between sleep and mood is addressed. Contextual pictorial models that hypothesise learning on an emotion scale and emotion on a learning scale have been proposed. Essentially, convoluted associations between physiological and psychological factors, including sleep and mood that determine academic performance are recognised and affirmed. The emerged picture reveals far more complexity than perceived. It questions the currently adopted ‘one-size fits all’ approach in education and urges to envisage formulating bespoke strategies to optimise teaching-learning approaches while retaining uniformity in education. The information presented here can help improvise education strategies and provide better academic and pastoral support to students during their academic journey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students

A 4-year longitudinal study investigating the relationship between flexible school starts and grades

Early morning university classes are associated with impaired sleep and academic performance

Introduction.

Academic performance and cognitive activities like learning are influenced by sleep and mood or emotion. This review discusses the roles of sleep and mood/emotion in learning and academic performance.

Sleep, mood, and emotion: definitions and descriptions

Sleep duration refers to “total amount of sleep obtained, either during the nocturnal sleep episode or across the 24-hour period” (Kline, 2013a ). Sleep quality is defined as “one’s satisfaction of the sleep experience, integrating aspects of sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, sleep quantity, and refreshment upon awakening” (Kline, 2013b ). Along similar lines, it is thought to be “one’s perception that they fall asleep easily, get sufficient duration so as to wake up feeling rested, and can make it through their day without experiencing excessive daytime sleepiness” (Štefan et al., 2018 ). Sleep disturbance includes disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (insomnias) and sleep–wake schedule, as well as dysfunctions associated with either sleep or stages of sleep or partial arousals (Cormier, 1990 ). Sleep deprivation is a term used loosely to describe a lack of appropriate/sufficient amount of sleep (Levesque, 2018 ). It is “abnormal sleep that can be described in measures of deficient sleep quantity, structure and/or sleep quality” (Banfi et al., 2019 ). In a study, sleep deprivation was defined as a sleep duration of 6 h or less (Roberts and Duong, 2014 ). Sleep disorder overarches disorders related to sleep. It has many classifications (B. Zhu et al., 2018 ). Sleep disorders or sleep-related problems include insomnia, hypersomnia, obstructive sleep apnoea, restless legs and periodic limb movement disorders, and circadian rhythm sleep disorders (Hershner and Chervin, 2014 ).

Mood is a pervasive and sustained feeling that is felt internally and affects all aspects of an individual’s behaviour (Sekhon and Gupta, 2021 ). However, by another definition, it is believed to be transient. It is low-intensity, nonspecific, and an affective state. Affective state is an overarching term that includes both emotions and moods. In addition to transient affective states of daily life, mood includes low-energy/activation states like fatigue or serenity (Kleinstäuber, 2013 ). Yet another definition of mood refers to mood as feelings that vary in intensity and duration, and that usually involves more than one emotion (Quartiroli et al., 2017 ). According to the American Psychological Association, mood is “any short-lived emotional state, usually of low intensity” and which lacks stimuli, whereas emotion is a “complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioural and physiological elements”. Emotion is a certain level of pleasure or displeasure (X. Liu et al., 2018 ). It is “a response to external stimuli and internal mental representations” (L. Zhang et al., 2021 ). It is “a conscious mental reaction (such as anger or fear) which is subjectively experienced as a strong feeling usually deriving from one’s circumstances, mood, or relationships with others”. “This feeling is typically accompanied by physiological and behavioural changes in the body”. “This mental state is an instinctive or intuitive feeling which arises spontaneously as distinguished from reasoning or knowledge” (Thibaut, 2015 ).

Since there is some overlap between the descriptions of mood and emotion, in the context of the core content of this review, here, mood and emotion have not been differentiated based on their theoretical/psychological definitions. This is because the aim of the review is not to distinguish between the effects of mood and emotion on learning. Thus, these have been referred to as general affective states; essentially specific states of mind that affect learning. Also, these have been addressed in the context of the study being discussed and cited in that specific place in the review.

Rationale for the topic

Sleep is essential for normal physiological functionality. The panel of National Sleep Foundation suggests sleep durations for various age groups and agrees that the appropriate sleep duration for young adults and adults would be 7–9 hours, and for older adults would be 7–8 hours (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015 ). Today, people sleep for 1–2 hours less than that around 50–100 years ago (Roenneberg, 2013 ). Millions of adults frequently get insufficient sleep (Vecsey et al., 2009 ), including college and university students who often report poor and/or insufficient sleep (Bahammam et al., 2012 ; Curcio et al., 2006 ; Hershner and Chervin, 2014 ). During the COVID-19 pandemic, sleep problems have been highly prevalent in the general population (Gualano et al., 2020 ; Jahrami et al., 2021 ; Janati Idrissi et al., 2020 ) and the student community (Marelli et al., 2020 ). Poor and insufficient sleep is a public health issue because it increases the risk of developing chronic pathologies, and imparts negative social and economic outcomes (Hafner et al., 2017 ).

Like sleep, mood and emotions determine our physical and mental health. Depressive disorders have prevailed as one of the leading causes of health loss for nearly 30 years (James et al., 2018 ). Increased incidence of mood disorders amongst the general population has been observed (Walker et al., 2020 ), and there is an increase in such disorders amongst students (Auerbach et al., 2018 ). These have further risen during the COVID-19 pandemic (Son et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ).

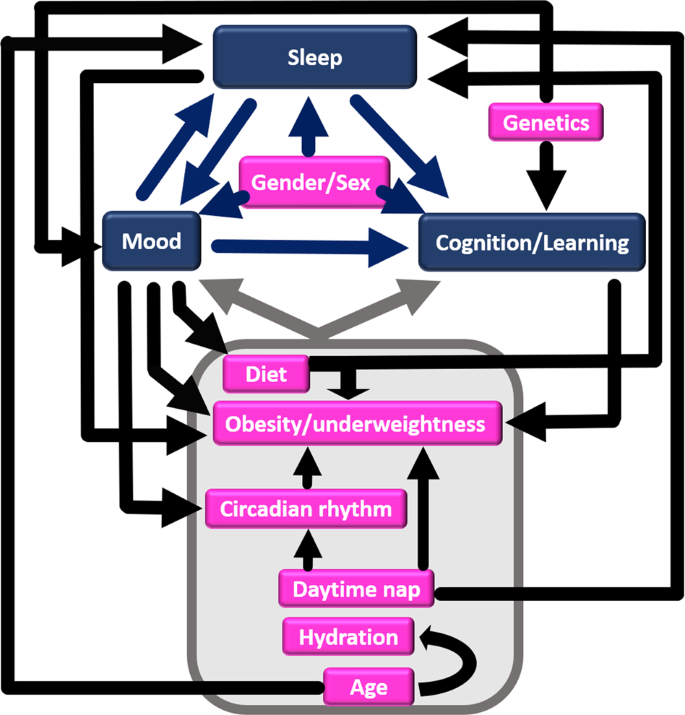

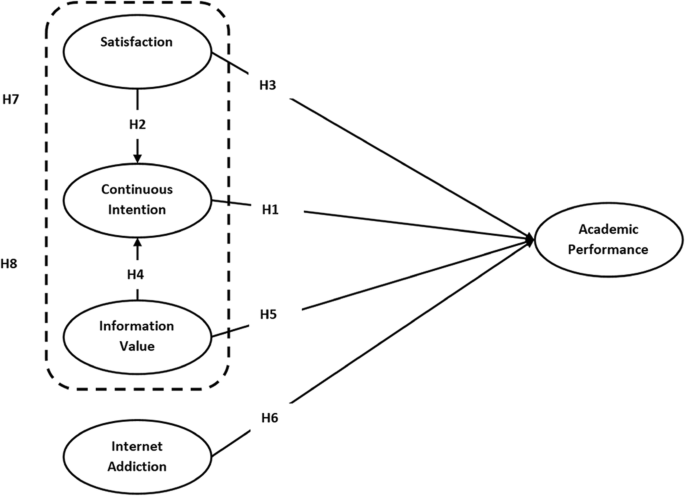

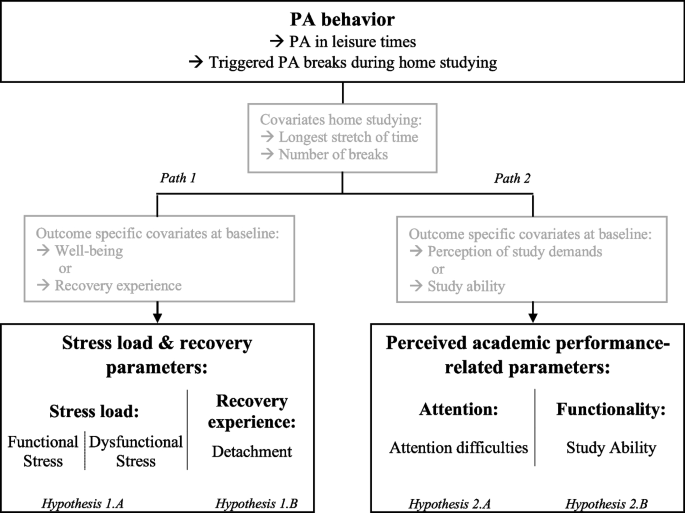

The relationship between sleep, mood and cognition/learning is far more complex than perceived. Therefore, this review aims to recognise the interrelationships between the aforementioned trio. It critically examines the effects of sleep and mood on cognition, learning and academic performance (Fig. 1 ). Furthermore, it discusses how various regulatory factors can directly or indirectly influence cognition and learning. Factors discussed here are age, gender, diet, hydration level, obesity, sex hormones, daytime nap, circadian rhythm, and genetics (Fig. 1 ). The effect of sleep and mood on each other is also addressed. Pictorial models that hypothesise learning on an emotion scale and vice-versa have been proposed.

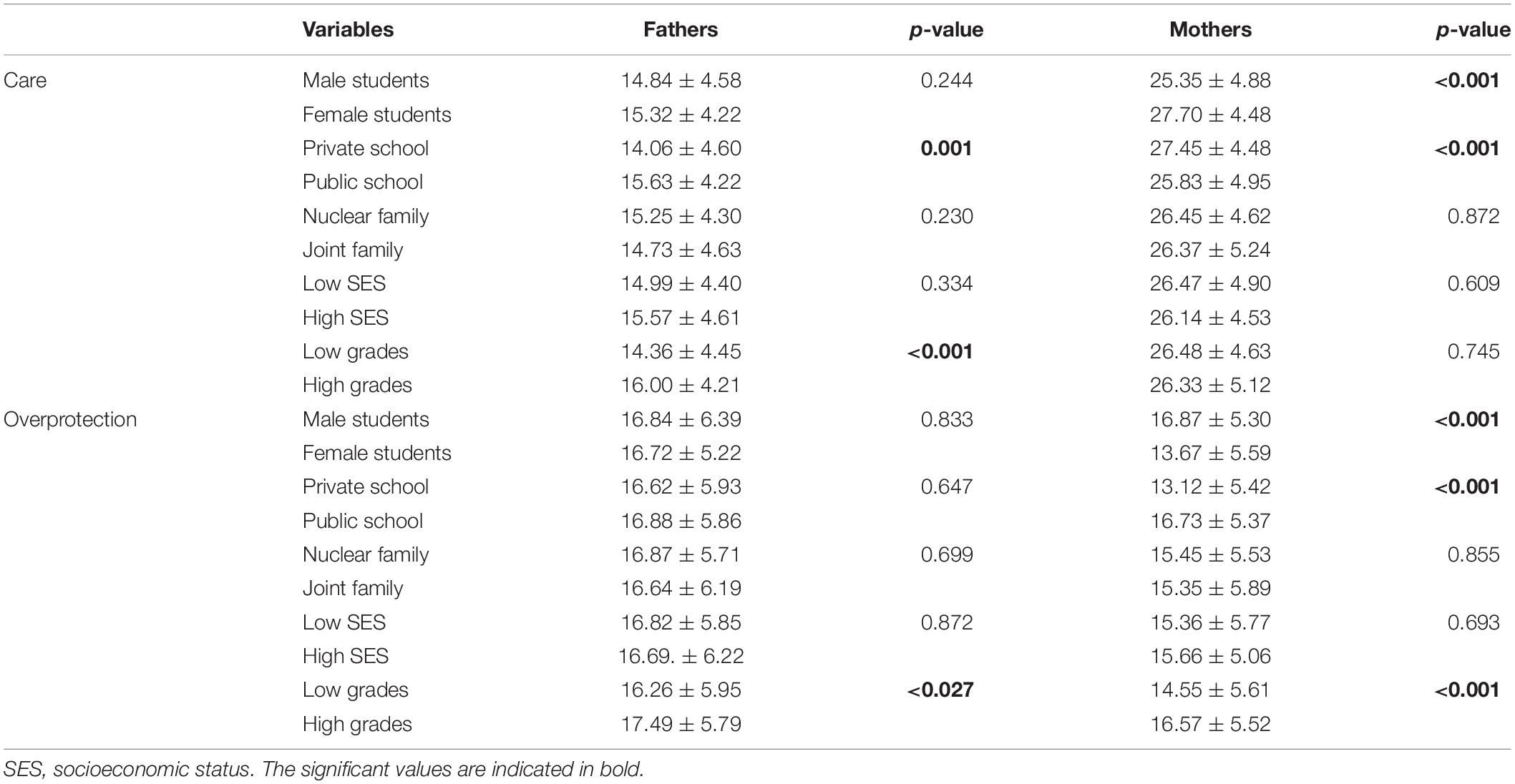

Sleep and mood/emotion affect cognition and academic achievement. Their effects can be additionally influenced by other factors like diet, metabolic disorders (e.g., obesity), circadian rhythm, daytime nap, hydration level, age, gender, and genetics. The figure presents the interrelationships and highlights the complexity emerging from the interdependence between factors, action of multiple factors on a single factor or vice-versa and the bidirectional nature of some associations. These associations collectively determine learning and thereby, academic achievement. Direction of the arrow represents effect of a factor on another.

Effect of sleep on cognition and academic performance

Adequate sleep positively affects memory, learning, acquisition of skills and knowledge extraction (Fenn et al., 2003 ; Friedrich et al., 2020 ; Huber et al., 2004 ; Schönauer et al., 2017 ; Wagner et al., 2004 ). It allows the recall of previously gained knowledge despite the acquisition of new information and memories (Norman, 2006 ). Sleeping after learning acquisition regardless of the time of the day is thought to be beneficial for memory consolidation and performance (Hagewoud et al., 2010 ). Therefore, unperturbed sleep is essential for maintaining learning efficiency (Fattinger et al., 2017 ).

Sleep quality and quantity are strongly associated with academic achievement in college students (Curcio et al., 2006 ; Okano et al., 2019 ). Sufficient sleep positively affects grade point average, which is an indicator of academic performance (Abdulghani et al., 2012 ; Hershner and Chervin, 2014 ) and supports cognitive functionality in school-aged children (Gruber et al., 2010 ). As expected, insufficient sleep is associated with poor performance in school, college and university students (Bahammam et al., 2012 ; Hayley et al., 2017 ; Hedin et al., 2020 ; Kayaba et al., 2020 ; Perez-Chada et al., 2007 ; Shochat et al., 2014 ; Suardiaz-Muro et al., 2020 ; Taras and Potts-Datema, 2005 ). In adolescents aged 14–18 years, not only did sleep quality affect academic performance (Adelantado-Renau, Jiménez-Pavón, et al., 2019 ) but one night of total sleep deprivation negatively affected neurobehavioral performance-attention, reaction time and speed of cognitive processing, thereby putting them at risk of poor academic performance (Louca and Short, 2014 ). In university students aged 18–25 years, poor sleep quality has been strongly associated with daytime dysfunctionality (Assaad et al., 2014 ). Medical students tend to show poor sleep quality and quantity. In these students, not sleep duration but sleep quality has been shown to correlate with academic scores (Seoane et al., 2020 ; Toscano-Hermoso et al., 2020 ). Students may go through repeated cycles wherein the poor quality of sleep could lead to poor performance, which in turn may again lead to poor quality of sleep (Ahrberg et al., 2012 ). Sleep deprivation in surgical residents tends to decrease procedural skills, while in non-surgical residents it diminishes interpretational ability and performance (Veasey et al., 2002 ).

Such effects of sleep deprivation are obvious because it can impair procedural and declarative learning (Curcio et al., 2006 ; Kurniawan et al., 2016 ), decrease alertness (Alexandre et al., 2017 ), and impair memory consolidation (Hagewoud et al., 2010 ), attention and decision making (Alhola and Polo-Kantola, 2007 ). It can increase low-grade systemic inflammation and hinder cognitive functionality (Choshen-Hillel et al., 2020 ). Hippocampus is the region in the brain that plays the main role in learning, memory, social cognition, and emotion regulation (Y. Zhu et al., 2019 ). cAMP signalling plays an important role in several neural processes such as learning and memory, cellular excitability, motor function and pain (Lee, 2015 ). A brief 5-hour period of sleep deprivation interferes with cAMP signalling in the hippocampus and impairs its function (Vecsey et al., 2009 ). Thus, optimal academic performance is hindered, if there is a sleep disorder (Hershner and Chervin, 2014 ).

Caveats to affirming the impact of sleep on cognition and academic performance

Despite the clear significance of appropriate sleep quality and quantity in cognitive processes, there are some caveats to drawing definitive conclusions in certain areas. First, there are uncertainties around how much sleep is optimal and how to measure sleep quality. This is further confounded by the dependence of sleep quality and quantity on various genetic and environmental factors (Roenneberg, 2013 ). Moreover, although sleep enhances emotional memory, during laboratory investigations, this effect has been observed only under specific experimental conditions. Also, the experiments conducted have differed in the methods used and in considering parameters like timing and duration of sleep, age, gender and outcome measure (Lipinska et al., 2019 ). This orientates conclusions to be specific to those experimental conditions and prevents the formation of generic opinions that would be applicable to all circumstances.

Furthermore, some studies on the effects of sleep on learning and cognitive functions have shown either inconclusive or apparently unexpected results. For example, in a study, although college students at risk for sleeping disorders were thought to be at risk for academic failure, this association remained unclear (Gaultney, 2010 ). Other studies showed that the effect of sleep quality and duration on academic performance was trivial (Dewald et al., 2010 ) and did not significantly correlate with academic performance (Johnston et al., 2010 ; Sweileh et al., 2011 ). In yet another example, despite the reduction in sleep hours during stressful periods, pharmacy students did not show adversely affected academic performance (Mnatzaganian et al., 2020 ). Also, the premise underlining the significance of sleep hours in enhancing the performance of clinical duties was challenged when the average daily sleep did not affect burnout in clinical residents, where the optimal sleep hours that would maximise learning and improve performance remained unknown (Mendelsohn et al., 2019 ). In some other examples, poor sleep quality was associated with stress but not with academic performance that was measured as grade point average (Alotaibi et al., 2020 ), showed no significant impact on academic scores (Javaid et al., 2020 ) and there was no significant difference between high-grade and low-grade achievers based on sleep quality (Jalali et al., 2020 ). Insomnia reflects regularly experienced sleeping problems. Strangely, in adults aged 40–69 years, those with frequent insomnia showed slightly better cognitive performance than others (Kyle et al., 2017 ).

The reason for such inconclusive and unanticipated results could be that sleep is not the sole determinant of learning. Learning is affected by various other factors that may alter, exacerbate, or surpass the influence of sleep on learning (Fig. 1 ). These factors have been discussed in the subsequent sections.

Effect of mood/emotion on cognition and learning

Emotions reflect a certain level of pleasure or displeasure (X. Liu et al., 2018 ). Panksepp described seven basic types of emotions, whereby lust, seeking, play and care are positive emotions whereas anger, fear and sadness are negative emotions (Davis and Montag, 2019 ). Emotions influence all cognitive functions including memory, focus, problem-solving and reasoning (Tyng et al., 2017 ). Positive emotions such as hope, joy and pride positively correlate with students’ academic interest, effort and achievement (Valiente et al., 2012 ) and portend a flexible brain network that facilitates cognitive flexibility and learning (Betzel et al., 2017 ).

Mood deficit often precedes learning impairment (LeGates et al., 2012 ). In a study by Miller et al. ( 2018 ), the negative mood is referred to as negative emotional induction, as was achieved by watching six horror films by the subjects in that study. Other examples of negative emotions given by the authors were anxiety and shame. Negative mood can unfavourably affect the learning of an unfamiliar language by suppressing the processing of native language that would otherwise help make connections, thereby reiterating the link between emotions and cognitive processing (Miller et al., 2018 ). Likewise, worry and anxiety affect decision-making. High level of worry is associated with poor task performance and decreased foresight during decision-making (Worthy et al., 2014 ). State anxiety reflects a current mood state and trait anxiety reflects a stable personality trait. Both are associated with an increased tendency of “more negative or more threatening interpretation of ambiguous information”, as can be the case in clinically depressed individuals (Bisson and Sears, 2007 ). This could explain why some people who show the symptoms of depression and anxiety may complain of confusion and show an inability to focus and use cognition skills to appraise contextual clues. Patients with major depressive disorder have scored lower on working and verbal memory, motor speed and attention than healthy participants (Hidese et al., 2018 ). Similarly, apathy, anxiety, depression, and mood disorders in stroke patients can adversely affect the functional recovery of patients’ cognitive functions (Hama et al., 2020 ). These examples collectively present a positive correlation between good mood and cognitive processes.

Caveats to affirming the impact of mood/emotion on cognition and academic performance

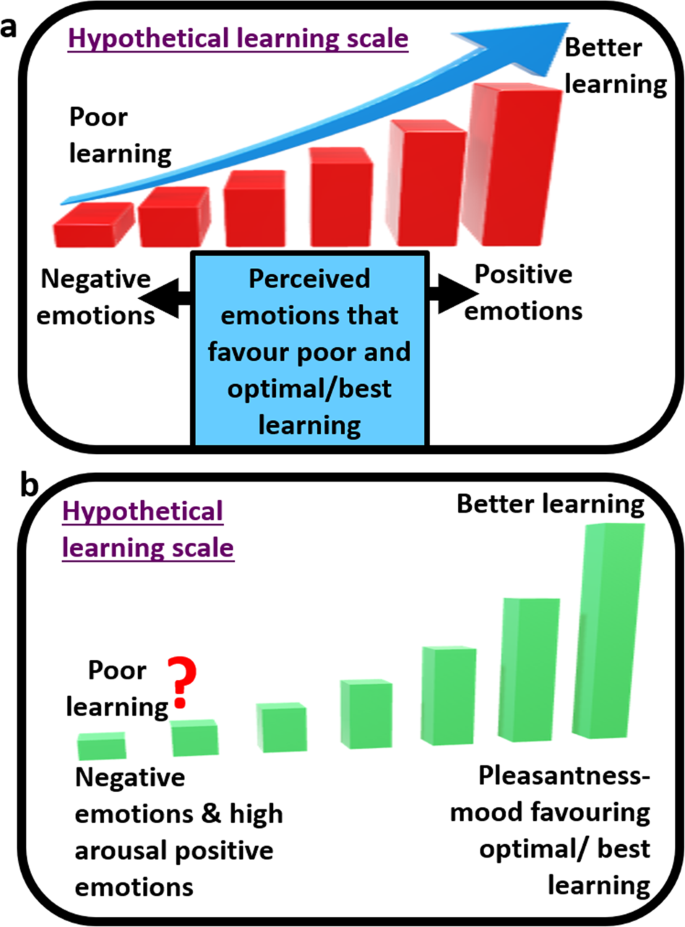

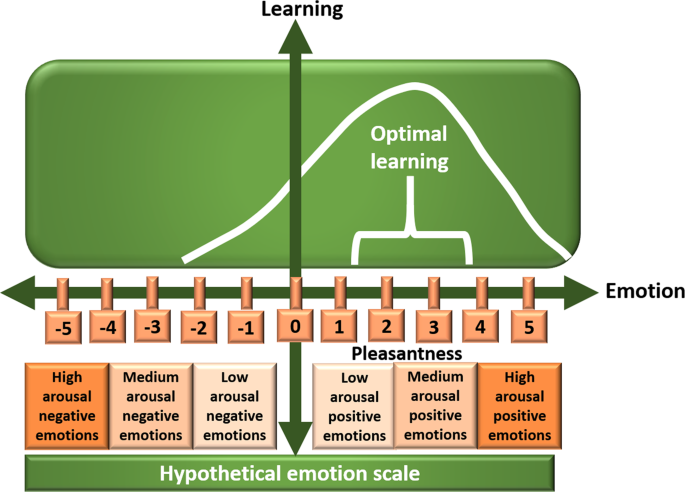

Based on the examples and discussion so far, a direct relationship between emotions and learning could be hypothesised, whereby positive emotions would promote creative learning strategies and academic success, whereas negative emotions would lead to cognitive impairment (Fig. 2a ). However, this relationship is far more complex and different than perceived.

Emotions have been shown on a hypothetical learning scale. a Usually, positive and negative emotions are perceived to match with optimal and poor learning, respectively. b Emotions that lead to sub-optimal/poor and optimal/better learning have been shown on the hypothetical learning scale. Here, distinct from ( a ), both negative emotions and high arousal positive emotions have been implicated in poorer learning compared with low-intensity positive emotion like pleasantness; the latter is believed to lead to optimal learning. The question mark reflects that some negative emotions like shame might stimulate learning, but the exact intensity of such emotions and whether these would facilitate better or worse learning than high arousal positive emotions or pleasantness need to be investigated.

Although positive mood favours the recall of learnt words, it correlates with increased distraction and poor planning (Martin and Kerns, 2011 ). High levels of positive emotions like excitedness and elatedness may decrease achievement (Fig. 2b ) (Valiente et al., 2012 ). It may be surprising to know that negative emotions such as shame and anxiety can arouse cognitive activity (Miller et al., 2018 ). Along similar lines, it has been observed that participants exposed to sad and neutral moods performed similarly in visual statistical (learning) tasks but those who experienced sad stimuli showed high conscious access to the acquired statistical knowledge (Bertels et al., 2013 ). Dysphoria is a state of dissatisfaction that may be accompanied by anxiety and depression. Participants with dysphoria have shown more sensitivity to temporal shifts in outcome contingencies than those without dysphoria (Msetfi et al., 2012 ), and these participants reiterated the depressive realism effect and were quicker in endorsing the connection between negative words and ambiguous statements, demonstrating a negative bias (Hindash and Amir, 2012 ). Likewise, not the positive emotion but negative emotion has been shown to influence the learning outcomes, and it increased the efficiency and precision of learning morphosyntactic instructions involving morphology and syntax of a foreign language (X. Liu et al., 2018 ). Thus, negative emotions can allow, and at times, stimulate or facilitate learning (Figs. 2 and 3 ). Further investigation is needed on the intensity of these emotions, whether these would facilitate better or worse learning than high-intensity positive emotions and whether the results would be task specific.

The figure depicts that low-to-medium intensity positive emotion like pleasantness leads to optimal learning, whereas high-intensity emotions, either positive or negative, may lead to suboptimal or comparatively poorer learning. The model considers the apparently unexpected data that negative emotions may stimulate learning. However, which negative emotions these would be, their intensities and their corresponding level of learning are not known, and so these are not shown in the figure. Also, the figure shows bias towards positive emotions in mediating optimal learning. This information is based on the literature so far. Note that the figure represents concepts only and is not prescriptive. It shows inequality and differences between the impacts of high arousal positive and high arousal negative emotions. This concept needs to be investigated. Therefore, the figure may/may not be an accurate mathematical representation of learning with regards to the intensities of positive and negative emotions. In actuality, the scaling and intensities of emotions on the negative and positive sides of the scale may not be equal, particularly in reference to the position of optimal learning on the scale. Furthermore, upon plotting the 3rd dimension, which could be one or more of the regulatory factors discussed here might alter the position and shape of the optimal learning peak.

Moreover, the intensity of positive emotions does not show direct mathematical proportionality to learning/achievement. In other words, the concept of ‘higher the intensity of positive emotions, higher the achievement’ is not applicable. Low-intensity positive emotions such as satisfaction and relaxedness may be potentially dysregulating and high-intensity positive emotions may hamper achievement (Figs. 2b and 3 ). Optimal achievement is likely to be associated with low to medium level intensity of positive emotions like pleasantness (Valiente et al., 2012 ) (Fig. 3 ). Therefore, it has been proposed that both positive and negative high arousal emotions impair cognitive ability (Figs. 2b and 3 ) whereas low-arousal emotions could enhance behavioural performance (Miller et al., 2018 ).

Interestingly, some studies have indicated that emotions do not play a significant role in context. For example, a study showed that there was no evidence that negative emotions in depressed participants showed negative interpretations of ambiguous information (Bisson and Sears, 2007 ). In another study, improvements in visuomotor skills happened regardless of perturbation or mood states (Kaida et al., 2017 ). Thus, mood can either impair, enhance or have no effect on cognition. The effect of mood on cognition and learning can be variable and depend on the complexity of the task (Martin and Kerns, 2011 ) and/or other factors. Some of these factors have been discussed in the following section. The discrepancies in the data on the effects of mood on cognition and learning may be partly attributed to the influence of these factors on cognitive functions.

Factors affecting cognition and its relationships with sleep and mood/emotion

The relationship of cognition with sleep and mood is confounded by the influence of various factors (Tyng et al., 2017 ) such as diet, hydration level, metabolic disorders (e.g., obesity), sex hormones and gender, sleep, circadian rhythm, age and genetics (Fig. 1 ). These factors and their relationships with learning are discussed in this section.

A healthy diet is defined as eating many servings per day of fruits and vegetables, while maintaining a critical view of the consumption of saturated fat, sugar and salt (Healthy Diet—an Overview|ScienceDirect Topics, n.d.). It is also about adhering to two or more of the three healthy attributes with regards to food intake, namely, sufficiently low meat, high fish and high fruits and vegetables (Sarris et al., 2020 ). Another definition of a healthy diet is the total score of the healthy eating index >51 (Zhao et al., 2021 ).

The association between an unhealthy diet and the development of metabolic disorders has been long established. In addition, food affects both cognition and emotion (Fig. 1 ) (Spencer et al., 2017 ). Food and mood show a bidirectional relation whereby food affects mood and mood affects the choice of food made by the individual. Alongside, poor diet can lead to depression while a healthy diet reduces the risk of depression (Francis et al., 2019 ). A high-fat diet stimulates the hippocampus to initiate neuroinflammatory responses to minor immune challenges and this causes memory loss. Likewise, low intake of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids can affect endocannabinoid and inflammatory pathways in the brain causing microglial phagocytosis, i.e., engulfment of synapses by the brain microglia in the hippocampus, eventually leading to memory deficits and depression. On the other hand, vegetables and fruits rich in polyphenolics can lower oxidative stress and inflammation, and thereby avert and/or reverse age-related cognitive dysfunctionality (Spencer et al., 2017 ). Fruits and vegetables, fish, eggs, nuts, and dairy products found in the Mediterranean diet can reduce the risk of developing depression and promote better mental health than sugar-sweetened beverages and high-fat food found in Western diets. Consumption of dietary antioxidants such as the polyphenols in green tea has shown a negative correlation with depression-like symptoms (Firth et al., 2020 ; Huang et al., 2019 ; Knüppel et al., 2017 ). Likewise, chocolate or its components have been found to reduce negative mood or enhance mood, and also enhance or alter cognitive functions temporarily (Scholey and Owen, 2013 ). Alcohol consumption is prevalent amongst university students including those who report feelings of sadness and hopelessness (Htet et al., 2020 ). It can lead to poor academic performance, hamper tasks that require a high degree of cognitive control, dampen emotional responsiveness, impair emotional processing, and generally cause emotional dysregulation (Euser and Franken, 2012 ). Further details on the effects of diet on mood have been discussed elsewhere (Singh, 2014 ). Diet also affects sleep (Binks et al., 2020 ), which in turn affects learning and academic performance. Thus, diet is linked with sleep, mood, and brain functionality (Fig. 1 ).

Water is a critical nutrient accounting for about 3/4th of the brain mass (N. Zhang et al., 2019 ). Unlike the previously thought deficit of 2% or more in body water levels, loss of about 1–2% can be detrimental and hinder normal cognitive functionality (Riebl and Davy, 2013 ). Thus, mild dehydration can disrupt cognitive functions and mood; particularly applicable to the very old, the very young and those living in hot climatic conditions or those exercising rigorously. Dehydration diminishes alertness, concentration, short-term memory, arithmetic ability, psychomotor skills and visuomotor tracking. This is possibly due to the dehydration-induced physiological stress which competes with cognitive processes. In children, voluntary water intake has been shown to improve visual attention, enhance memory performance (Popkin et al., 2010 ) and generally improve memory and attention (Benton, 2011 ). In adults, dehydration can elevate anger, fatigue and depression and impair short-term memory and attention, while rehydration can alleviate or significantly improve these parameters (Popkin et al., 2010 ; N. Zhang et al., 2019 ). Thus, dehydration causes alterations in cognition and emotions, thereby showcasing the impact of hydration levels on both learning and emotional status (Fig. 1 ).

Interestingly, when older persons are deprived of water, they are less thirsty and less likely to drink water than water-deprived younger persons. This can be due to the defective functionality of baroreceptors, osmoreceptors and opioid receptors that alter thirst regulation with aging (Popkin et al., 2010 ). Since water is essential for the maintenance of memory and cognitive performance, the decline of cognitive functionality in the elderly could be partly attributed to their lack of sufficient fluid/water intake when dehydrated.

Obesity and underweightness

Normal weight is defined as a body mass index between 18.5 and 25 kg/m 2 (McGee and Diverse Populations Collaboration, 2005 ) or between 22 and 26.99 kg/m 2 (Nösslinger et al., 2021 ). Being underweight reflects rapid weight loss or an inability to increase body mass and is defined through grades (1–3) of thinness. In children, these are associated with poor academic performance in reading and writing skills, and mathematics (Haywood and Pienaar, 2021 ). Basically, underweight children may have health issues and this could affect their academic abilities (Zavodny, 2013 ). Also, malnourished children tend to show low school attendance and may show poor concentration and impaired motor functioning and problem-solving skills that could collectively lead to poor academic performance at school (Haywood and Pienaar, 2021 ). Malnourished children can show poor performance on cognitive tasks that require executive function. Executive functions could be impaired in overweight children too and this may lead to poor academic performance (Ishihara et al., 2020 ). The negative relation between overweightness and academic performance also implies that the reverse may be true. Poor academic outcome may cause children to overeat and reduce exercise or play and this could lead to them being overweight (Zavodny, 2013 ).

The influence of weight on academic performance is reiterated in observations that in children independent of socioeconomic and other factors, weight loss in overweight/obese children and weight gain in underweight children positively influenced their academic performance (Ishihara et al., 2020 ). Interestingly, independent of the BMI classification, perceptions of underweight and overweight can predict poorer academic performance. In youth, not only larger body sizes but perceptions about deviating from the “correct weight” can impede academic success. This clearly indicates an impact of overweight and underweight perceptions on the emotional and physical health of adolescents (Fig. 1 ) (Livermore et al., 2020 ).

Cognitive and mood disorders are common co-morbidities associated with obesity. Compared to people with normal weight, obese individuals frequently show some dysfunction in learning, memory, and other executive functions. This has been partly attributed to an unhealthy diet, which causes a drift in the gut microbiota. In turn, the obesity-associated microbiota contributes to obesity-related complications including neurochemical, endocrine and inflammatory changes underlying obesity and its comorbidities (Agustí et al., 2018 ). The exacerbated inflammation in obesity may impair the functionality of the region in the brain that is associated with learning, memory, and mood regulation (Castanon et al., 2015 ).

Obesity and mood appear to have a reciprocal relationship whereby obesity is highly prevalent amongst individuals with major depressive disorder and obese individuals are at a high risk of developing anxiety, depression and cognitive malfunction (Restivo et al., 2017 ). In patients with major depressive disorder, obesity has been associated with reduced cognitive functions, likely due to the reduction in grey matter and impaired integrity of white matter in the brain, particularly in areas related to cognition (Hidese et al., 2018 ). Obesity has been shown to be a predictor of depression and the two are linked via psychobiological mechanisms (LaGrotte et al., 2016 ). Notably, sleep deprivation increases the risk of obesity (Beccuti and Pannain, 2011 ) and sleep helps evade obesity (Pearson, 2006 ). Collectively, this links cognition and academic achievement with sleep, obesity, and mood.

Sex hormones and gender

According to the Office of National Statistics, the UK government defines sex as that assigned at birth and which is generally male or female, whereas gender is where an individual may see themselves as having no gender or non-binary gender or on a spectrum between man and woman. The following section discusses both sex and gender in context, as addressed within the cited studies.

Studies show that females outperform males in most academic subjects (Okano et al., 2019 ) and show more sustained performance in tests than male peers (Balart and Oosterveen, 2019 ). This indicates that biological sex may play a role in academic performance. The hormone oestrogen helps develop and maintain female characteristics and the reproductive system. Oestrogen also affects hippocampal neurogenesis, which involves neural stem cells proliferation and survival, and this contributes to memory retention and cognitive processing. Generally, on average, females show higher levels of oestrogen than males. This may partly explain the observed sex-based differences in academic achievement. Administration of oestrogen in females has been proposed to positively affect cognitive behaviour as well as depressive-like and anxiety-like behaviours (Hiroi et al., 2016 ). Clinical trials can establish whether there are any sex-based differences in cognition following oestrogen administration in males and females.

Progesterone, the hormone released by ovaries in females is also produced by males to synthesise testosterone. It affects some non-reproduction functions in the central nervous system in both males and females such as neural circuits formation, and regulates memory, learning and mood (González-Orozco and Camacho-Arroyo, 2019 ). The menstrual cycle in females shows alterations in oestrogen and progesterone levels and is broadly divided into early follicular, mid ovulation and late luteal phase. It is believed that the low-oestrogen-low-progesterone early follicular phase relates to better spatial abilities and “male favouring” cognitive abilities, whereas the high-oestrogen-high-progesterone late follicular or mid-luteal phases relate to verbal fluency, memory and other “female favouring” cognitive abilities (Sundström Poromaa and Gingnell, 2014 ). Thus, sex-hormone derivatives (salivary oestrogen and salivary progesterone) can be used as predictors of cognitive behaviour (McNamara et al., 2014 ). These ovarian hormones decline with menopause, which may affect cognitive and somatosensory functions. However, ovariectomy of rats, which depleted ovarian hormones, caused depression-like behaviour in rats but did not affect spatial performance (Li et al., 2014 ). While this suggests a positive effect of these hormones on mood, it questions their function in cognition and proposes activity-specific functions, which need to be investigated.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter. Reduced serotonin is correlated with cognitive dysfunctions. Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 is the rate-limiting enzyme in serotonin synthesis. Polymorphisms of this enzyme have been implicated in cognitive disorders. Women have a lower rate of serotonin synthesis and are more susceptible to such dysfunctions than men (Hiroi et al., 2016 ; Nishizawa et al., 1997 ), implying a greater impact of serotonin reduction on cognitive functions in women than in men. Central serotonin also helps to maintain the feeling of happiness and wellbeing, regulates behaviour, and suppresses appetite, thereby modulating nutrient intake. Additionally, it has the ability to promote the wake state and inhibit rapid eye movement sleep (Arnaldi et al., 2015 ; Yabut et al., 2019 ). Thus, any sex-based differences in serotonin levels may affect cognitive functions directly or indirectly via the aforementioned parameters.

Interestingly, data on the relationship between sex and sleep have been ambiguous. While in one study, female students at a university showed less sleep difficulties than male peers (Assaad et al., 2014 ), other studies showed that female students were at a higher risk of presenting sleep disorders related to nightmares (Toscano-Hermoso et al., 2020 ) and insomnia was significantly associated with the risk of poor academic performance only in females (Marta et al., 2020 ). Collectively, sex and gender may influence learning directly, or indirectly by affecting sleep and mood; the other two factors that affect cognitive functions (Fig. 1 ).

Circadian rhythm

Circadian rhythm is a biological phenomenon that lasts for ~24 hours and regulates various physiological processes in the body including the sleep–wake cycles. Circadian rhythm is linked with memory formation, learning (Gerstner and Yin, 2010 ), light, mood and brain circuits (Bedrosian and Nelson, 2017 ). We use light to distinguish between day and night. Interestingly, light stimulates the expression of microRNA-132, which is the sole known microRNA involved in photic regulation of circadian clock in mammals (Teodori and Albertini, 2019 ). The photosensitive retinal ganglions that express melanopsin in eyes not only orchestrate the circadian rhythm with the external light-dark cycle but also influence the impact of light on mood, learning and overall health (Patterson et al., 2020 ). For example, we frequently experience depression-like feelings during the dark winter months and pleasantness during bright summer months. This can be attributed to the circadian regulation of neural systems such as the limbic system, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, and monoamine neurotransmitters. Mistimed light in the night disturbs our biological judgement leading to a negative impact on health and mood. Thus, increased incidence of mood disorders correlates with disruption of the circadian rhythm (Walker et al., 2020 ). Interestingly, a study involving university students showed the significance of short-wavelength light, specifically, blue-enriched LED light in reducing melatonin levels [best circadian marker rhythm (Arendt, 2019 )], and improved the perception of mood and alertness (Choi et al., 2019 ). While these examples depict the effect of circadian rhythm on mood, the reverse is also true. Individuals who demonstrate depression show altered circadian rhythm and disturbances in sleep (Fig. 1 ) (Germain and Kupfer, 2008 ). Also, since circadian rhythm regulates physiological and metabolic processes, disruption in circadian rhythm can cause metabolic dysfunctions like diabetes and obesity (Shimizu et al., 2016 ), eventually affecting cognition and learning (Fig. 1 ).

Delayed circadian preference including a tendency to sleep later in the night is common amongst young adults and university students (Hershner and Chervin, 2014 ). This delayed sleep phase disorder, often seen in adolescents, negatively impacts academic achievement and is frequently accompanied by depression (Bartlett et al., 2013 ; Sivertsen et al., 2015 ). Alongside, there is a positive correlation between sleep regularity and academic grades, implying that irregularity in sleep–wake cycles is associated with poor academic performance, delayed circadian rhythm and sleep and wake timings (Phillips et al., 2017 ). Even weekday-to-weekend discrepancy in sleeping patterns has been associated with impaired academic performance in adolescents (Sun et al., 2019 ). Further connection between sleep pattern, circadian rhythm, alertness, and the mood was observed in adolescents aged 13–18 where evening chronotypes showed poor sleep quality and low alertness. In turn, sleep quality was associated with poor outcomes including low daytime alertness and depressed mood. Evening chronotypes and those with poor sleep quality were more likely to report poor academic performance via association with depression. Strangely, sleep duration did not directly affect their functionality (Short et al., 2013 ). Contrastingly, in adults aged 40–69 years, the evening and morning chronotypes were associated with superior and poor cognitive performance, respectively, relative to intermediate chronotype (Kyle et al., 2017 ). In addition to this age-specific effect, the effect of chronotype can be subject-specific. For example, in subjects involving fluid cognition for example science, there was a significant correlation between grades and chronotype, implying that late chronotypes would be disadvantaged in exams of scientific subjects if examined early in the day. This was distinct from humanistic/linguistic subjects in which no correlation with chronotype was observed (Zerbini et al., 2017 ). These observations question the “one size fits all” approach of assessment strategies.

Daytime nap

The benefits of daytime napping in healthy adults have been discussed in detail elsewhere (Milner and Cote, 2009 ). In children, daytime nap facilitates generalisation of word meanings (Horváth et al., 2016 ) and explicit memory consolidation but not implicit perceptual learning (Giganti et al., 2014 ). A 90-min nap increases hippocampal activation, restores its function and improves declarative memory encoding (Ong et al., 2020 ). Generally, daytime napping has been found to be beneficial for memory, alertness, and abstraction of general concepts, i.e. creating relational memory networks (Lau et al., 2011 ). Delayed nap following a learning activity helps in the retention of declarative memory (Alger et al., 2010 ) and exercising before the daytime nap is thought to benefit memory more than napping or exercising alone (Mograss et al., 2020 ). Also, napping for 0.1–1 hour has been associated with a reduced prevalence of overweightness (Chen et al., 2019 ).

Contrastingly, in some studies, napping has been found to impart no substantial benefits to cognition. For example, despite the daytime nap of 1 hour, procedural performance remained impaired after total deprivation of night sleep (Kurniawan et al., 2016 ), indicating that daytime nap may not always be reparative. In other studies, 4 weeks of 90-minute nap intervention (napping or restriction) did not alter behavioural performance or brain activity during sleep in healthy adults aged 18–35 (McDevitt et al., 2018 ) and enhancements in visuomotor skills occurred regardless of daytime nap (Kaida et al., 2017 ). Age is a factor in relishing the benefits of napping. A 90-min nap can benefit episodic memory retention in young adults but these benefits decrease with age (Scullin et al., 2017 ) and may be harmful in the older population, particularly in those getting more than 9 hours of sleep (Mantua and Spencer, 2017 ; Mehra and Patel, 2012 ).

Napping can increase the risk for depression (Foley et al., 2007 ) and show a positive association with depression, i.e., napping is associated with greater likelihood of depression (Y. Liu et al., 2018 ). Cardiovascular diseases, cirrhosis and kidney disease have been linked with both daytime napping and depression (Abdel-Kader et al., 2009 ; Hare et al., 2014 ; Ko et al., 2013 ). While a previous study indicated that the time of nap, morning or afternoon, made no difference to its effect on mood (Gillin et al., 1989 ), a subsequent study suggested that the timing of nap influenced relapses into depression. Specifically, in depressed individuals, morning naps caused a higher propensity of relapse into depression than afternoon naps, thereby proposing the involvement of circadian rhythm in this process. Apart from depression, studies have struggled to identify the direct effect of nap on mood (Gillin et al., 1989 ; Wiegand et al., 1993 ). As daytime napping has been associated with poor sleep quality (Alotaibi et al., 2020 ), it may lead to irregular sleep–wake patterns and thereby alter circadian rhythm (Phillips et al., 2017 ). Also, nap duration was found to be important. In patients with affirmed depression, shorter naps were found to be more detrimental than longer naps (Wiegand et al., 1993 ), whereas, in the elderly, more and longer naps were associated with increased risk of mortality amongst the cognitively impaired individuals (Hays et al., 1996 ). Thus, daytime napping can affect cognitive processes directly or indirectly via its association with circadian rhythm, metabolic dysfunctions, mood, or sleep (Fig. 1 ).

Aging is associated with decreased neurogenesis and structural changes in the hippocampus amongst other neurophysiological effects. This in turn is associated with age-related mood and memory impairments (Kodali et al., 2015 ). Study on the effect of age on mood and emotion regulation in adults aged 20–70 years showed that older participants had a higher tendency to use cognitive reappraisal while reducing negative mood and enhancing positive mood. Interestingly, while women did not show correlations between age and reappraisal, men showed an increment in cognitive reappraisal with age. This indicates gender-based differences in the effect of aging on emotion regulation (Masumoto et al., 2016 ). The influence of age on sleep is well known. Older people that have sleep patterns like the young demonstrate stronger cognitive functions and lesser health issues than those whose sleep patterns match their age (Djonlagic et al., 2021 ). Collectively, this interlinks age, cognition, mood, and sleep.

Apparently, there is a genetic influence on learning and emotions. Approximately 148 independent genetic loci have been identified that influence and support the notion of heritability of general cognitive functions (Davies et al., 2018 ). This indicates the role of genetics in cognition (Fig. 1 ). The α-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (encoded by the gene CHRNA7 ) is expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems and other peripheral tissues. It has been implicated in various behavioural and psychiatric disorders (Yin et al., 2017 ) and recognised as an important receptor of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway that exhibits a neuroprotective role. Its activation has been shown to improve learning, working memory and cognition (Ren et al., 2017 ). However, there have been some contrasting results related to this receptor. While its deletion has been linked with cognitive impairments, aggressive behaviours, decreased attention span and epilepsy, Chrna7 deficient mice have shown normal learning and memory, and the gene was not deemed essential for the control of emotions and behaviour in mice. Thus, the role of α-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in maintaining mood and cognitive functions, although indicative, is yet to be fully deciphered in humans (Yin et al., 2017 ). Similarly, the gene Slitrk6 , which plays a role in the development of neural circuits in the inner ear may also play a role in some cognitive functions, but it does not appear to play a clear role in mood or memory (Matsumoto et al., 2011 ). Notably, inborn errors of metabolism, i.e., rare inherited disorders may show psychiatric manifestations even in the absence of obvious neurological symptoms. These manifestations could involve impairments in cognitive functions, and/or in the regulation of learning, mood and behaviour (Bonnot et al., 2015 ).

Other factors and associations

Indeed, optimal learning is additionally influenced by factors beyond those discussed here. These factors could be adequate meal frequency, physical activity and low screen time (Adelantado-Renau, Jiménez-Pavón, et al., 2019 ; Burns et al., 2018 ). In adolescents, the time of internet usage was identified as a factor that mediated the association between sleep quality (but not duration) and academic performance (Adelantado-Renau, Diez-Fernandez, et al., 2019 ; Evers et al., 2020 ). Self-perception is another determinant of performance. The American Psychological Association defines self-perception as “person’s view of his or herself or of any of the mental or physical attributes that constitute the self. Such a view may involve genuine self-knowledge or varying degrees of distortion”. Compared to other residents, surgery residents indicated the less perceived impact of sleep-loss on their performance (Woodrow et al., 2008 ). This may be related to specific work culture or profession where there is the reluctance of acceptance of natural human limitations posed by sleep deprivation. Whether there is real resistance to sleep deprivation amongst such professional groups or a misconception requires investigation. Exercise affects both sleep and mood; the latter probably affects in a sex-dependent manner. Thus, moderate exercise has been proposed as a therapy for treating mood disorders (Lalanza et al., 2015 ).

Sleep and mood: a bidirectional but unequal relationship

While the cause of the relationship between sleep and mood is not fully understood, adequate quality and quantity of sleep has shown physiological benefits and may enhance mood (Scully, 2013 ). Sleep encourages insightful behaviour (Wagner et al., 2004 ) and regulates mood (Vandekerckhove and Wang, 2017 ). Sleeping and dreaming activate emotional and reward systems that help process information, and consolidate memory “with high emotional or motivational value”. Inevitably, sleep disturbances can dysregulate these motivational and emotional processes and cause predisposition to mood disorders (Perogamvros et al., 2013 ). Sleep loss can reinforce negative emotions, reduce positive emotions, and increase the risk for psychiatric disorders. In children and adolescents, it can increase anger, depression, confusion and aggression (Vandekerckhove and Wang, 2017 ). Thus, sleep disorder has been associated with depression, where the former can predict the latter (LaGrotte et al., 2016 ). Sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness amongst adolescents and college students cause mood deficits, negatively affect their mood and learning, and lead to poor academic performance (Hershner and Chervin, 2014 ; Short and Louca, 2015 ). Thus, disrupted sleep acts as a diagnostic factor for mood disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, major depression and anxiety (Walker et al., 2020 ).

In turn, mood affects sleep quality. Emotional events and stress during the daytime can affect sleep physiology. Negative states such as sadness, loneliness, and grief are related to sleep impairments, whereas positive states like love can be associated with lessened sleep duration but better sleep quality; the latter needs further evidence. Although dysregulation of emotion relates to poor sleep quality (Vandekerckhove and Wang, 2017 ), the effect of mood on sleep can be modulated by our approach of coping with our emotions (Vandekerckhove and Wang, 2017 ). Therefore, this effect is significantly smaller than the reverse (Triantafillou et al., 2019 ).

Summary and future direction

Sleep and mood influence cognitive functions and thereby affect academic performance. In turn, these are influenced by a network of regulatory factors that directly or indirectly affect learning. The compilation of observations clearly demonstrates the complexity and multifactorial dependence of academic achievement on students’ lifestyle and physiology, as discussed in the form of effectors like age, gender, diet, hydration level, obesity, sex hormones, circadian rhythm, and genetics (Fig. 1 ).

The emerged picture brings forth two points. First, it partly explains the ambiguous and conflicting data on the effects of sleep and mood on academic performance. Second, these revelations collectively question the ‘one-size fits all’ approach in implementing education strategies. It urges to explore formulating bespoke group-specific or subject-specific strategies to optimise teaching–learning approaches. Knowledge of these factors and their associations with each other can aid in forming these groups and improving educational strategies to better support students. However, it is essential to retain parity in education, and this would be the biggest challenge while formulating bespoke approaches.

In the context of sleep, studies could be conducted that first establish standardised means of measuring sleep quality and then measure sleep quality and quantity simultaneously in individuals of different ages groups, sex, and professions. This could then be related to their performance in their respective fields/professions; academic or otherwise. Such studies will help to better understand these interrelationships and address some discrepancies in the data.

Limitations

One limitation of this review is that it addresses only academic performance. Performance should be viewed broadly and be inclusive of all types, for example, athletic performance, dance performance or performance at work on a desk job that may include creative work or financial/mathematical calculations. It would be interesting to investigate the effect of alterations in sleep and mood on various types of performances and those results will be able to provide us with a much broader picture than the one depicted here. Notably, while learning can be assessed, it is difficult to quantify emotions (Ayaz‐Alkaya, 2018 ; Nieh et al., 2013 ). As such, it is believed that qualitative research is a better approach for studying emotional responses than quantitative research (Ayaz‐Alkaya, 2018 ).

Another point of limitation is related to the proposed models in Figs. 2 and 3 . These show hypothetical mathematical scales of learning and emotion where emotions are placed on a scale of learning, and learning is placed on the scale of emotions, respectively. While these models certainly help to better visualise and understand the interrelationships, these scales show only 2-dimensions. There could be a 3rd dimension, and this could be either one of the factors or a combination of the several factors discussed here (and beyond) that determine the effect of mood/emotion on learning/cognition. Additionally, the depicted scales and their interpretations may vary between individuals because the intensity of the same emotion felt by different individuals may differ. Figure 3 depicts emotions and learning. Based on the studies so far, here, negative emotions have been shown to stimulate learning, but which negative emotions these would be (for e.g., shame or anxiety), at what intensities these would stimulate optimal learning if at all, and how this compares with optimal learning induced by positive emotions remains to be investigated. Therefore, the extent to which these scales can be applied in real-life needs to be verified.

Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD (2009) Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4(6):1057–1064. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00430109

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Abdulghani HM, Alrowais NA, Bin-Saad NS, Al-Subaie NM, Haji AMA, Alhaqwi AI (2012) Sleep disorder among medical students: relationship to their academic performance. Med Teacher 34(Suppl 1):S37–S41. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.656749

Article Google Scholar

Adelantado-Renau M, Diez-Fernandez A, Beltran-Valls MR, Soriano-Maldonado A, Moliner-Urdiales D (2019) The effect of sleep quality on academic performance is mediated by Internet use time: DADOS study. J Pediatr 95(4):410–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2018.03.006

Adelantado-Renau M, Jiménez-Pavón D, Beltran-Valls MR, Moliner-Urdiales D (2019) Independent and combined influence of healthy lifestyle factors on academic performance in adolescents: DADOS Study. Pediatr Res 85(4):456–462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0285-z

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Agustí A, García-Pardo MP, López-Almela I, Campillo I, Maes M, Romaní-Pérez M, Sanz Y (2018) Interplay between the gut–brain axis, obesity and cognitive function. Front Neurosci 12:155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00155

Ahrberg K, Dresler M, Niedermaier S, Steiger A, Genzel L (2012) The interaction between sleep quality and academic performance. J Psychiatr Res 46(12):1618–1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.008

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Alexandre C, Latremoliere A, Ferreira A, Miracca G, Yamamoto M, Scammell TE, Woolf CJ (2017) Decreased alertness due to sleep loss increases pain sensitivity in mice. Nat Med 23(6):768–774. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4329

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alger SE, Lau H, Fishbein W (2010) Delayed onset of a daytime nap facilitates retention of declarative memory. PLoS ONE 5(8):e12131. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012131

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alhola P, Polo-Kantola P (2007) Sleep deprivation: impact on cognitive performance Neuropsychiatr Disease Treat 3(5):553–567. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2656292/

Alotaibi AD, Alosaimi FM, Alajlan AA, Bin Abdulrahman KA (2020) The relationship between sleep quality, stress, and academic performance among medical students. J Fam Community Med 27(1):23–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_132_19

Arendt J (2019). Melatonin: countering chaotic time cues. Front Endocrinol 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00391

Arnaldi D, Famà F, De Carli F, Morbelli S, Ferrara M, Picco A, Accardo J, Primavera A, Sambuceti G, Nobili F (2015) The role of the serotonergic system in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 38(9):1505–1509. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.5000

Assaad S, Costanian C, Haddad G, Tannous F (2014) Sleep patterns and disorders among university students in Lebanon. J Res Health Sci 14(3):198–204

PubMed Google Scholar

Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Ebert DD, Green JG, Hasking P, Murray E, Nock MK, Pinder-Amaker S, Sampson NA, Stein DJ, Vilagut G, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC (2018) The WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnormal Psychol 127(7):623–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362

Ayaz‐Alkaya S (2018) Overview of psychosocial problems in individuals with stoma: a review of literature. Int Wound J 16(1):243–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13018

Bahammam AS, Alaseem AM, Alzakri AA, Almeneessier AS, Sharif MM (2012) The relationship between sleep and wake habits and academic performance in medical students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 12:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-61

Balart P, Oosterveen M (2019) Females show more sustained performance during test-taking than males. Nat Commun 10(1):3798. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11691-y

Banfi T, Coletto E, d’Ascanio P, Dario P, Menciassi A, Faraguna U, Ciuti G (2019) Effects of sleep deprivation on surgeons dexterity. Front Neurol 10:595. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00595

Bartlett DJ, Biggs SN, Armstrong SM (2013) Circadian rhythm disorders among adolescents: assessment and treatment options. Med J Aust 199(8):S16–S20. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja13.10912

Beccuti G, Pannain S (2011) Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 14(4):402–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283479109

Bedrosian TA, Nelson RJ (2017) Timing of light exposure affects mood and brain circuits. Transl Psychiatry 7(1):e1017. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.262

Benton D (2011) Dehydration influences mood and cognition: a plausible hypothesis? Nutrients 3(5):555–573. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3050555

Bertels J, Demoulin C, Franco A, Destrebecqz A (2013) Side effects of being blue: influence of sad mood on visual statistical learning. PLoS ONE 8(3):e59832. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059832

Betzel RF, Satterthwaite TD, Gold JI, Bassett DS (2017) Positive affect, surprise, and fatigue are correlates of network flexibility. Sci Rep 7(1):520. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00425-z

Binks H, Vincent E, Gupta G, Irwin C, Khalesi S (2020) Effects of diet on sleep: a narrative review. Nutrients 12(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12040936

Bisson MAS, Sears CR (2007) The effect of depressed mood on the interpretation of ambiguity, with and without negative mood induction. Cogn Emotion 21(3):614–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600750715

Bonnot O, Herrera PM, Tordjman S, Walterfang M (2015) Secondary psychosis induced by metabolic disorders. Front Neurosci 9:177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00177

Burns RD, Fu Y, Brusseau TA, Clements-Nolle K, Yang W (2018) Relationships among physical activity, sleep duration, diet, and academic achievement in a sample of adolescents. Prev Med Rep 12:71–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.08.014

Castanon N, Luheshi G, Layé S (2015) Role of neuroinflammation in the emotional and cognitive alterations displayed by animal models of obesity. Front Neurosci 9:229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00229

Chen M, Zhang X, Liang Y, Xue H, Gong Y, Xiong J, He F, Yang Y, Cheng G (2019) Associations between nocturnal sleep duration, midday nap duration and body composition among adults in Southwest China. PLoS ONE 14(10):e0223665. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223665

Choi K, Shin C, Kim T, Chung HJ, Suk H-J (2019) Awakening effects of blue-enriched morning light exposure on university students’ physiological and subjective responses. Sci Rep 9(1):345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36791-5

Choshen-Hillel S, Ishqer A, Mahameed F, Reiter J, Gozal D, Gileles-Hillel A, Berger I (2020) Acute and chronic sleep deprivation in residents: cognition and stress biomarkers. Med Educ. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14296

Cormier RE (1990) Sleep disturbances. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW (eds) Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations, 3rd edn. Butterworths.

Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L (2006) Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev 10(5):323–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001

Davies G, Lam M, Harris SE, Trampush JW, Luciano M, Hill WD, Hagenaars SP, Ritchie SJ, Marioni RE, Fawns-Ritchie C, Liewald DCM, Okely JA, Ahola-Olli AV, Barnes CLK, Bertram L, Bis JC, Burdick KE, Christoforou A, DeRosse P, Deary IJ (2018) Study of 300,486 individuals identifies 148 independent genetic loci influencing general cognitive function. Nat Commun 9(1):2098. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04362-x

Davis KL, Montag C (2019) Selected principles of pankseppian affective neuroscience. Front Neurosci 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.01025

Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM (2010) The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev 14(3):179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004

Djonlagic I, Mariani S, Fitzpatrick AL, Van Der Klei V.M.G.T.H, Johnson DA, Wood AC, Seeman T, Nguyen HT, Prerau MJ, Luchsinger JA, Dzierzewski JM, Rapp SR, Tranah GJ, Yaffe K, Burdick KE, Stone KL, Redline S, Purcell SM (2021) Macro and micro sleep architecture and cognitive performance in older adults. Nat Hum Behav 5, 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00964-y

Euser AS, Franken IHA (2012) Alcohol affects the emotional modulation of cognitive control: an event-related brain potential study. Psychopharmacology 222(3):459–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-012-2664-6

Evers K, Chen S, Rothmann S, Dhir A, Pallesen S (2020) Investigating the relation among disturbed sleep due to social media use, school burnout, and academic performance. J Adolesc 84:156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.08.011

Fattinger S, de Beukelaar TT, Ruddy KL, Volk C, Heyse NC, Herbst JA, Hahnloser RHR, Wenderoth N, Huber R (2017) Deep sleep maintains learning efficiency of the human brain. Nat Commun 8:15405. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15405

Fenn KM, Nusbaum HC, Margoliash D (2003) Consolidation during sleep of perceptual learning of spoken language. Nature 425(6958):614–616. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01951

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Firth, J, Gangwisch, JE, Borsini, A, Wootton, RE, & Mayer, EA (2020). Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? The BMJ 369. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2382

Foley DJ, Vitiello MV, Bliwise DL, Ancoli-Israel S, Monjan AA, Walsh JK (2007) Frequent napping is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia in older adults: findings from the National Sleep Foundation ‘2003 Sleep in America’ Poll. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 15(4):344–350. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000249385.50101.67

Francis HM, Stevenson RJ, Chambers JR, Gupta D, Newey B, Lim CK (2019) A brief diet intervention can reduce symptoms of depression in young adults—a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 14(10):e0222768. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222768

Friedrich M, Mölle M, Friederici AD, Born J (2020) Sleep-dependent memory consolidation in infants protects new episodic memories from existing semantic memories. Nat Commun 11(1):1298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14850-8

Gaultney JF (2010) The prevalence of sleep disorders in college students: Impact on academic performance. J Am College Health 59(2):91–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.483708

Germain A, Kupfer DJ (2008) Circadian rhythm disturbances in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol 23(7):571–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.964

Gerstner JR, Yin JCP (2010) Circadian rhythms and memory formation. Nat Rev Neurosci 11(8):577–588. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2881

Giganti F, Arzilli C, Conte F, Toselli M, Viggiano MP, Ficca G (2014) The effect of a daytime nap on priming and recognition tasks in preschool children. Sleep 37(6):1087–1093. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3766

Gillin JC, Kripke DF, Janowsky DS, Risch SC (1989) Effects of brief naps on mood and sleep in sleep-deprived depressed patients. Psychiatry Res 27(3):253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90141-8

González-Orozco JC, Camacho-Arroyo I (2019) Progesterone actions during central nervous system development. Front Neurosci 13:503. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00503

Gruber R, Laviolette R, Deluca P, Monson E, Cornish K, Carrier J (2010) Short sleep duration is associated with poor performance on IQ measures in healthy school-age children. Sleep Med 11(3):289–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2009.09.007

Gualano MR, Lo Moro G, Voglino G, Bert F, Siliquini R (2020) Effects of Covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134779

Hafner M, Stepanek M, Taylor J, Troxel WM, van Stolk C (2017) Why sleep matters-the economic costs of insufficient sleep: a Cross-Country Comparative Analysis. Rand Health Q 6(4):11

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hagewoud R, Whitcomb SN, Heeringa AN, Havekes R, Koolhaas JM, Meerlo P (2010) A time for learning and a time for sleep: the effect of sleep deprivation on contextual fear conditioning at different times of the day Sleep 33(10):1315–1322. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2941417/

Hama S, Yoshimura K, Yanagawa A, Shimonaga K, Furui A, Soh Z, Nishino S, Hirano H, Yamawaki S, Tsuji T (2020) Relationships between motor and cognitive functions and subsequent post-stroke mood disorders revealed by machine learning analysis. Sci Rep 10(1):19571. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76429-z

Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T (2014) Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J 35(21):1365–1372. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht462

Hayley AC, Sivertsen B, Hysing M, Vedaa Ø, Øverland S (2017) Sleep difficulties and academic performance in Norwegian higher education students. Br J Educ Psychol 87(4):722–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12180

Hays JC, Blazer DG, Foley DJ (1996) Risk of napping: excessive daytime sleepiness and mortality in an older community population. J Am Geriatr Soc 44(6):693–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01834.x

Haywood X, Pienaar AE (2021) Long-term influences of stunting, being underweight, and thinness on the academic performance of primary school girls: the NW-CHILD Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(17):8973. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178973

Healthy Diet—an overview|ScienceDirect Topics (n.d.) https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/healthy-diet . Accessed 4 Dec 2021.

Hedin G, Norell-Clarke A, Hagell P, Tønnesen H, Westergren A, Garmy P (2020). Insomnia in relation to academic performance, self-reported health, physical activity, and substance use among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176433

Hershner SD, Chervin RD (2014) Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat Sci Sleep 6:73–84. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S62907

Hidese S, Ota M, Matsuo J, Ishida I, Hiraishi M, Yoshida S, Noda T, Sato N, Teraishi T, Hattori K, Kunugi H (2018) Association of obesity with cognitive function and brain structure in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 225:188–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.028

Hindash AHC, Amir N (2012) Negative interpretation bias in individuals with depressive symptoms. Cogn Ther Res 36(5):502–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9397-4

Hiroi R, Weyrich G, Koebele SV, Mennenga SE, Talboom JS, Hewitt LT, Lavery CN, Mendoza P, Jordan A, Bimonte-Nelson HA (2016) Benefits of hormone therapy estrogens depend on estrogen type: 17β-estradiol and conjugated equine estrogens have differential effects on cognitive, anxiety-like, and depressive-like behaviors and increase tryptophan hydroxylase-2 mRNA levels in dorsal raphe nucleus subregions. Front Neurosci 10:517. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00517

Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Katz ES, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Neubauer DN, O’Donnell AE, Ohayon M, Peever J, Rawding R, Sachdeva RC, Setters B, Vitiello MV, Ware JC, Adams Hillard PJ (2015) National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 1(1):40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010

Horváth K, Liu S, Plunkett K (2016) A daytime nap facilitates generalization of word meanings in young toddlers. Sleep 39(1):203–207. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.5348

Htet H, Saw YM, Saw TN, Htun NMM, Mon KL, Cho SM, Thike T, Khine AT, Kariya T, Yamamoto E, Hamajima N (2020) Prevalence of alcohol consumption and its risk factors among university students: a cross-sectional study across six universities in Myanmar. PLoS ONE 15(2):e0229329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229329

Huang Q, Liu H, Suzuki K, Ma S, Liu C (2019) Linking what we eat to our mood: a review of diet, dietary antioxidants, and depression. Antioxidants 8(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8090376

Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, Tononi G (2004) Local sleep and learning. Nature 430(6995):78–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02663

Ishihara T, Nakajima T, Yamatsu K, Okita K, Sagawa M, Morita N (2020) Longitudinal relationship of favorable weight change to academic performance in children. npj Sci Learn 5(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0063-z

Jahrami H, BaHammam AS, Bragazzi NL, Saif Z, Faris M, Vitiello MV (2021) Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 17(2):299–313. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8930

Jalali R, Khazaei H, Paveh BK, Hayrani Z, Menati L (2020) The effect of sleep quality on students’ academic achievement. Adv Med Educ Pract 11:497–502. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S261525

James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, Abdollahpour I, Abdulkader RS, Abebe Z, Abera SF, Abil OZ, Abraha HN, Abu-Raddad LJ, Abu-Rmeileh NME, Accrombessi MMK, Murray CJL (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 392(10159):1789–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

Janati Idrissi A, Lamkaddem A, Benouajjit A, Ben El Bouaazzaoui M, El Houari F, Alami M, Labyad S, Chahidi A, Benjelloun M, Rabhi S, Kissani N, Zarhbouch B, Ouazzani R, Kadiri F, Alouane R, Elbiaze M, Boujraf S, El Fakir S, Souirti Z (2020) Sleep quality and mental health in the context of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Morocco. Sleep Med 74:248–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.07.045

Javaid R, Momina AU, Sarwar MZ, Naqi SA (2020) Quality of sleep and academic performance among medical university students. J College Physicians Surg-Pakistan 30(8):844–848. https://doi.org/10.29271/jcpsp.2020.08.844

Johnston A, Gradisar M, Dohnt H, Billows M, Mccappin S (2010) Adolescent sleep and fluid intelligence performance. Sleep Biol Rhythm 8(3):180–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-8425.2010.00442.x

Kaida K, Itaguchi Y, Iwaki S (2017) Interactive effects of visuomotor perturbation and an afternoon nap on performance and the flow experience. PLoS ONE 12(2):e0171907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171907

Kayaba M, Matsushita T, Enomoto M, Kanai C, Katayama N, Inoue Y, Sasai-Sakuma T (2020) Impact of sleep problems on daytime function in school life: a cross-sectional study involving Japanese university students. BMC Public Health 20(1):371. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08483-1

Kleinstäuber M (2013) Mood. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR (eds) Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. Springer, pp. 1259–1261

Kline C (2013a) Sleep duration. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR (eds) Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. Springer, pp. 1808–1810

Kline C (2013b) Sleep quality. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR (eds) Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. Springer, pp. 1811–1813

Knüppel A, Shipley MJ, Llewellyn CH, Brunner EJ (2017) Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: prospective findings from the Whitehall II study. Sci Rep 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05649-7

Ko F-Y, Yang AC, Tsai S-J, Zhou Y, Xu L-M (2013) Physiologic and laboratory correlates of depression, anxiety, and poor sleep in liver cirrhosis. BMC Gastroenterol 13:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-13-18

Kodali M, Parihar VK, Hattiangady B, Mishra V, Shuai B, Shetty AK (2015) Resveratrol prevents age-related memory and mood dysfunction with increased hippocampal neurogenesis and microvasculature, and reduced glial activation. Sci Rep 5:8075. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08075

Kurniawan IT, Cousins JN, Chong PLH, Chee MWL (2016) Procedural performance following sleep deprivation remains impaired despite extended practice and an afternoon nap. Sci Rep 6:36001. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36001

Kyle SD, Sexton CE, Feige B, Luik AI, Lane J, Saxena R, Anderson SG, Bechtold DA, Dixon W, Little MA, Ray D, Riemann D, Espie CA, Rutter MK, Spiegelhalder K (2017) Sleep and cognitive performance: cross-sectional associations in the UK Biobank. Sleep Med 38:85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.07.001

LaGrotte C, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Calhoun SL, Liao D, Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN (2005) (2016). The relative association of obstructive sleep apnea, obesity and excessive daytime sleepiness with incident depression: a longitudinal, population-based study. Int J Obes 40(9):1397–1404. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.87

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lalanza JF, Sanchez-Roige S, Cigarroa I, Gagliano H, Fuentes S, Armario A, Capdevila L, Escorihuela RM (2015) Long-term moderate treadmill exercise promotes stress-coping strategies in male and female rats. Sci Rep 5:16166. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16166

Lau H, Alger SE, Fishbein W (2011) Relational memory: a daytime nap facilitates the abstraction of general concepts. PLoS ONE 6(11):e27139. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027139

Lee D (2015) Global and local missions of cAMP signaling in neural plasticity, learning, and memory. Front Pharmacol 6:161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00161

LeGates TA, Altimus CM, Wang H, Lee H-K, Yang S, Zhao H, Kirkwood A, Weber ET, Hattar S (2012) Aberrant light directly impairs mood and learning through melanopsin-expressing neurons. Nature 491(7425):594–598. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11673

Levesque RJR (2018) Sleep deprivation. In: Levesque RJR (ed) Encyclopedia of adolescence. Springer International Publishing, pp. 3606–3607

Li L-H, Wang Z-C, Yu J, Zhang Y-Q (2014) Ovariectomy results in variable changes in nociception, mood and depression in adult female rats. PLoS ONE 9(4):e94312. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094312

Lipinska G, Stuart B, Thomas KGF, Baldwin DS, Bolinger E (2019) Preferential consolidation of emotional memory during sleep: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol 10:1014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01014

Liu X, Xu X, Wang H (2018) The effect of emotion on morphosyntactic learning in foreign language learners. PLoS ONE 13(11):e0207592. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207592

Liu Y, Peng T, Zhang S, Tang K (2018) The relationship between depression, daytime napping, daytime dysfunction, and snoring in 0.5 million Chinese populations: exploring the effects of socio-economic status and age. BMC Public Health 18(1):759. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5629-9

Livermore M, Duncan MJ, Leatherdale ST, Patte KA (2020) Are weight status and weight perception associated with academic performance among youth? J Eat Disord 8:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00329-w

Louca M, Short MA (2014) The effect of one night’s sleep deprivation on adolescent neurobehavioral performance. Sleep 37(11):1799–1807. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4174