- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 26, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

Yom Kippur—the Day of Atonement—is considered the most important holiday in the Jewish faith. Falling in the month of Tishrei (September or October in the Gregorian calendar), it marks the culmination of the 10 Days of Awe, a period of introspection and repentance that follows Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. According to tradition, it is on Yom Kippur that God decides each person’s fate, so Jews are encouraged to make amends and ask forgiveness for sins committed during the past year. The holiday is observed with a 25-hour fast and a special religious service. Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah are known as Judaism’s “High Holy Days.” Yom Kippur 2023 begins on the evening of Sunday, September 24 and ends on the evening of Monday, September 25.

History and Significance of Yom Kippur

According to tradition, the first Yom Kippur took place after the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt and arrival at Mount Sinai, where God gave Moses the Ten Commandments. Descending from the mountain, Moses caught his people worshipping a golden calf and shattered the sacred tablets in anger. Because the Israelites atoned for their idolatry, God forgave their sins and offered Moses a second set of tablets.

Did you know? Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, one of the most famous Jewish athletes in American sports, made national headlines when he refused to pitch in the first game of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur. When Koufax’s replacement Don Drysdale was pulled from the game for poor performance, he told the Los Angeles Dodgers’ manager Walter Alston, "I bet you wish I was Jewish, too."

Jewish texts recount that during biblical times Yom Kippur was the only day on which the high priest could enter the inner sanctum of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem . There, he would perform a series of rituals and sprinkle blood from sacrificed animals on the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the Ten Commandments. Through this complex ceremony he made atonement and asked for God’s forgiveness on behalf of all the people of Israel . The tradition is said to have continued until the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 A.D; it was then adapted into a service for rabbis and their congregations in individual synagogues.

According to tradition, God judges all creatures during the 10 Days of Awe between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, deciding whether they will live or die in the coming year. Jewish law teaches that God inscribes the names of the righteous in the “book of life” and condemns the wicked to death on Rosh Hashanah; people who fall between the two categories have until Yom Kippur to perform “teshuvah,” or repentance. As a result, observant Jews consider Yom Kippur and the days leading up to it a time for prayer, good deeds, reflecting on past mistakes and making amends with others.

Observing Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur is Judaism’s most sacred day of the year; it is sometimes referred to as the “Sabbath of Sabbaths.” For this reason, even Jews who do not observe other traditions refrain from work, which is forbidden during the holiday, and participate in religious services on Yom Kippur, causing synagogue attendance to soar. Some congregations rent out additional space to accommodate large numbers of worshippers.

The Torah commands all Jewish adults (apart from the sick, the elderly and women who have just given birth) to abstain from eating and drinking between sundown on the evening before Yom Kippur and nightfall the next day. The fast is believed to cleanse the body and spirit, not to serve as a punishment. Religious Jews heed additional restrictions on bathing, washing, using cosmetics, wearing leather shoes and sexual relations. These prohibitions are intended to prevent worshippers from focusing on material possessions and superficial comforts.

Because the High Holy Day prayer services include special liturgical texts, songs and customs, rabbis and their congregations read from a special prayer book known as the machzor during both Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. Five distinct prayer services take place on Yom Kippur, the first on the eve of the holiday and the last before sunset on the following day. One of the most important prayers specific to Yom Kippur describes the atonement ritual performed by high priests during ancient times. The blowing of the shofar—a trumpet made from a ram’s horn—is an essential and emblematic part of both High Holy Days. On Yom Kippur, a single long blast is sounded at the end of the final service to mark the conclusion of the fast.

Traditions and Symbols of Yom Kippur

Pre-Yom Kippur feast: On the eve of Yom Kippur, families and friends gather for a bountiful feast that must be finished before sunset. The idea is to gather strength for 25 hours of fasting.

Breaking of the fast: After the final Yom Kippur service, many people return home for a festive meal. It traditionally consists of breakfast-like comfort foods such as blintzes, noodle pudding and baked goods.

Wearing white: It is customary for religious Jews to dress in white—a symbol of purity—on Yom Kippur. Some married men wear kittels, which are white burial shrouds, to signify repentance.

Charity: Some Jews make donations or volunteer their time in the days leading up to Yom Kippur. This is seen as a way to atone and seek God’s forgiveness. One ancient custom known as kapparot involves holding a live chicken or bundle of coins and circling it over one’s head while reciting a prayer. The chicken or money is then given to the poor.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Religion & Spirituality

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Return this item for free

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Mimini Mikhael: Essays on Yom Kippur and Teshuvah (Hebrew Edition) Hardcover – July 30, 2023

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 360 pages

- Language Hebrew

- Publisher Maggid

- Publication date July 30, 2023

- Dimensions 8.5 x 5.5 x 2 inches

- ISBN-10 159264645X

- ISBN-13 978-1592646456

- See all details

Customers who bought this item also bought

Product details

- Publisher : Maggid (July 30, 2023)

- Language : Hebrew

- Hardcover : 360 pages

- ISBN-10 : 159264645X

- ISBN-13 : 978-1592646456

- Item Weight : 1.23 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.5 x 5.5 x 2 inches

- #9,822 in Judaism (Books)

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top review from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Yom Kippur: What does Judaism actually say about forgiveness?

Professor of Psychology, Arizona State University

Disclosure statement

Adam B. Cohen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Arizona State University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

The Jewish High Holidays include Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. Traditionally, Jews view the holidays as a chance to reflect on our shortcomings, make amends and seek forgiveness, both from other people and from the Almighty.

Jews pray and fast on Yom Kippur to demonstrate their remorse and to focus on reconciliation. According to Jewish tradition, it is at the end of this solemn period that God seals his decision about each person’s fate for the coming year. Congregations recite a prayer called the “Unetanah Tokef ,” which recalls God’s power to decide “who shall live and who shall die, who shall reach the ends of his days and who shall not” – an ancient text that Leonard Cohen popularized with his song “ Who by Fire .”

Forgiveness and related concepts, such as compassion, are central virtues in many religions. What’s more, research has shown that it is psychologically beneficial .

But each religious tradition has its own particular views about forgiveness, as well, including Judaism. As a psychologist of religion , I have done research on these similarities and differences when it comes to forgiveness.

Person to person

Several specific attitudes about forgiveness are reflected in the liturgy of the Jewish High Holidays , so those who go to services are likely to be aware of them – even if they skip out for a snack.

In Jewish theology, only the victim has the right to forgive an offense against another person, and an offender should repent toward the victim before forgiveness can take place. Someone who has hurt another person must sincerely apologize three times . If the victim still withholds forgiveness, the offender is considered forgiven, and the victim now shares the blame.

The 10-day period known as the “Days of Awe” – Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur and the days between – is a popular time for forgiveness . Observant Jews reach out to friends and family they have wronged over the past year so that they can enter Yom Kippur services with a clean conscience and hope they have done all they can to mitigate God’s judgment.

The teaching that only a victim can forgive someone implies that God cannot forgive offenses between people until the relevant people have forgiven each other. It also means that some offenses, such as the Holocaust , can never be forgiven , because those martyred are dead and unable to forgive.

To forgive or not to forgive?

In psychological research , I have found that most Jewish and Christian participants endorse the views of forgiveness espoused by their religions.

As in Judaism, most Christian teachings encourage people to ask and give forgiveness for harms done to one another. But they tend to teach that more sins should be forgiven – and can be, by God, because Jesus’ death atoned vicariously for people’s sins .

Even in Christianity, not all offenses are forgivable. The New Testament describes blaspheming against the Holy Spirit as an unforgivable sin. And Catholicism teaches that there is a category called “ mortal sins ,” which cut off sinners from God’s grace unless they repent.

One of my research papers, consisting of three studies , shows that a majority of Jewish participants believe that some offenses are too severe to forgive; that it doesn’t make sense to ask someone other than the victim about forgiveness; and that forgiveness is not offered unconditionally, but after the offender has tried to make things right.

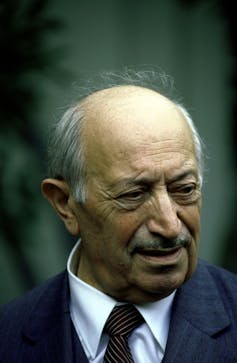

Take this specific example: In one of my research studies I asked Jewish and Christian participants if they thought a Jew should forgive a dying Nazi soldier who requested forgiveness for killing Jews. This scenario is described in “ The Sunflower ” by Simon Wiesenthal , a writer and Holocaust survivor famous for his efforts to prosecute German war criminals.

Jewish participants often didn’t think the question made sense: How could someone else – someone living – forgive the murder of another person? The Christian participants, on the other hand, who were all Protestants, usually said to forgive. They agreed more often with statements like “Mr. Wiesenthal should have forgiven the SS soldier” and “Mr. Wiesenthal would have done the virtuous thing if he forgave the soldier.”

It’s not just about the Holocaust. We also asked about a more everyday scenario – imagining that a student plagiarized a paper that participants’ friends had written, and then asked the participants for forgiveness – and saw similar results.

Jewish people have a wide variety of opinions on these topics, though, as they do in all things. “Two Jews, three opinions!” as the old saying goes. In other studies with my co-researchers, we showed that Holocaust survivors , as well as Jewish American college students born well after the Holocaust, vary widely in how tolerant they are of German people and products. Some are perfectly fine with traveling to Germany and having German friends, and others are unwilling to even listen to Beethoven.

In these studies, the key variable that seems to distinguish Jewish people who are OK with Germans and Germany from those who are not is to what extent they associate all Germans with Nazism. Among the Holocaust survivors , for example, survivors who had been born in Germany – and would have known German people before the war – were more tolerant than those whose first, perhaps only, exposure to Germans had been in the camps.

Forgiveness is good for you – or is it?

American society – where about 7 in 10 people identify as Christian – generally views forgiveness as a positive virtue. What’s more, research has found there are emotional and physical benefits to letting go of grudges.

But does this mean forgiveness is always the answer? To me, it’s an open question.

For example, future research could explore whether forgiveness is always psychologically beneficial, or only when it aligns with the would-be forgiver’s religious views.

If you are observing Yom Kippur, remember that – as with every topic – Judaism has a wide and, well, forgiving view of what is acceptable when it comes to forgiveness.

- Forgiveness

- apologising

- Jewish culture

- Religion and society

- High Holy Days

- High Holidays

- Religious holiday

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel from [“Remarks on Yom Kippur”] in Mas’at Rav (A Professional Supplement to Conservative Judaism) , August 1965, pp. 13–14 — reprinted in Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity (ed. Dr. Susannah Heschel, 1997), pp. 146-147.

Masat Rav (Rabbinical Assembly, August 1965) p. 13

Masat Rav (Rabbinical Assembly, August 1965) p. 14

Aharon N. Varady (transcription)

Aharon Varady (M.A.J.Ed./JTSA Davidson) is a volunteer transcriber for the Open Siddur Project. If you find any mistakes in his transcriptions, please let him know . Shgiyot mi yavin; Ministarot naqeni שְׁגִיאוֹת מִי־יָבִין; מִנִּסְתָּרוֹת נַקֵּנִי "Who can know all one's flaws? From hidden errors, correct me" (Psalms 19:13). If you'd like to directly support his work, please consider donating via his Patreon account . (Varady also translates prayers and contributes his own original work besides serving as the primary shammes of the Open Siddur Project and its website, opensiddur.org.)

Abraham Joshua Heschel

Abraham Joshua Heschel (January 11, 1907 – December 23, 1972) was a Polish-born American rabbi and one of the leading Jewish theologians and Jewish philosophers of the 20th century. Heschel, a professor of Jewish mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, authored a number of widely read books on Jewish philosophy and was active in the civil rights movement.

Works of related interest:

Comments, corrections, and queries cancel reply.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please consider supporting TheTorah.com .

Don’t miss the latest essays from TheTorah.com.

Stay updated with the latest scholarship

Study the Torah with Academic Scholarship

By using this site you agree to our Terms of Use

SBL e-journal

Staff Editors

Yom Kippur: A Celebration of Liberty on the Jubilee Year

TheTorah.com

APA e-journal

Historical Dimensions of Yom Kippur – Part 1

Categories:

ביום הכפרים תעבירו שופר…וקראתם דרור בארץ לכל ישביה

The very mention of the words “Yom Kippur” raise in many people’s mind the image of standing in shul all day, fasting, praying and saying viduy (confession). Yom Kippur, known as the holiest day of the year, is a somber day for reflection and repentance.

Yet we find in the Torah another dimension to Yom Kippur, that is somewhat surprising and more difficult to square with the characteristics of Yom Kippur at least as we know it today.

The Torah in Leviticus 25:8-12 instructs us to count seven Sabbatical years and to make the fiftieth year the Jubilee year. Besides cessation from all agricultural activity, the Jubilee year has two central features; all land sold between one Jubilee year and another reverts to its original owners and all indentured persons are released.

When does this liberation of land and servants take place? The answer is none other than on Yom Kippur! Verse 25:9 instructs us:

וְהַעֲבַרְתָּ שׁוֹפַר תְּרוּעָה בַּחֹדֶשׁ הַשְּׁבִעִי בֶּעָשׂוֹר לַחֹדֶשׁ בְּיוֹם הַכִּפֻּרִים תַּעֲבִירוּ שׁוֹפָר בְּכָל אַרְצְכֶם

Then you sound the horn loud; in the seventh month, on the tenth day of the month — the Day of Atonement — you shall have the horn sounded throughout the land.

Clearly in biblical times the concept of a synagogue did not exist, the format of our prayers was years away from being invented and the Israelites were not greeted on the eve of Yom Kippur with the somber melodious tune of Kol Nidrei. Nevertheless, it is difficult to imagine a day of repentance, the core of Yom Kippur, doubling as a moment of joyous celebration for all those freed from slavery.

Even more so, when one adds to Yom Kippur a moment in time that also serves to reset fifty years of real estate transactions—even granting that the actual transactions would have not been don on Yom Kippur itself—with families across the nation regaining their estates!

Read our short series on the Historical Dimensions of Yom Kippur

1 – Yom Kippur: A Celebration of Liberty on the Jubilee Year 2 – Yom Kippur: A Festival of Dancing Maidens 3 – The Absence of Yom Kippur in Nevi’im and Ketuvim 4 – Does Ezekiel in 572 B.C.E Know of Yom Kippur?

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

September 11, 2013

Last Updated

March 21, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Related Topics:

Essays on Related Topics:

Launched Shavuot 5773 / 2013 | Copyright © Project TABS, All Rights Reserved

The Six Day and Yom Kippur Wars in Historical Context

The confrontation between the Jewish state and its Arab neighbours is one of the most enduring and iconic conflicts that still persist today. Many scholars have argued that ‘for the best part of a century the Arab-Israeli conflict has been a complex problem with important ramifications for the international community’ [1] – and this is in many ways the truth. Created out of the ashes of the Second World War under the awful spectre of the Nazi Holocaust, Israel as a nation has survived and prospered both politically and economically, in no small part due to Western – primarily French and American – assistance. The Arab states have correspondingly been opposed to America and the West based on this implied support for Israel and has therefore turned to different stratagems in an attempt to combat this alliance – such as balancing with the USSR during the Cold War and increasingly using its market power (derived from the various oil reserves in the region) to further its political aims in the two decades since the Iron Curtain fell. Into this context there were two major (albeit rather short) wars – the Six Day War of 5-10 June 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Decisive, cataclysmic and dramatic, these two conflagrations have in many ways defined the conflict as it is today. But what were the main strategic and political consequences of these two wars? This essay will attempt to answer that question by examining relevant source material and analysing what conclusions can be drawn. The answers will fall into three broad areas – strategic, psychological and international – and will finish by assessing the importance of the 1967 and 1973 wars in relation to one another, as well as any collective inferences that can be made from that period as a whole.

It is easiest to begin with an examination of the pure strategic consequences of the two wars. This area can be further divided into two sub-categories – strategic depth and broader geo-politics, beginning with the former factor. A primarily military concept, strategic depth can be considered to be the literal and material barrier between the front line and the ‘vitals’ of the unit in question – which in this case is the nation of Israel. Prior to 1967 Israel appeared an embattled nation, sharing territory and borders with countries that were fundamentally hostile to it – with Egypt to the south, Jordan to the east and Syria and Lebanon to the north, Israel was hamstrung by the idea that a successful first strike could effectively cripple it as a nation. The events of early June 1967 changed the map completely. Writing in 1972, Edgar O’Ballance commented that ‘in six days of fighting the Israelis had occupied about 26,000 square miles of Arab territory’ [2] . Whilst his validity is slightly compromised by his inevitable ignorance of the events of the following year, the statement is still largely sound. The territorial spoils of war – including the Sinai, East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights and much of the West Bank – ‘increased Israel’s size by six times’ [3] and created a ‘vastly improved strategic situation’ [4] for the Israeli Defence Force (IDF). These borders, as opposed to those created following the 1948 conflict were ‘more defensible and afforded the military greater strategic depth’ [5] . This security was integral to the military and political thinking of Tel-Aviv meaning it is therefore fair to consider that the Six Day War has ‘defined the parameters of negotiations to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict ever since’ [6] . Even the 1973 war, despite being a more sustained confrontation, only ‘slightly modified the territorial framework’ [7] established in 1967. Neither side being willing to relinquish their various claims means that, when this stalemate is combined with the internationally sensitive Israeli occupation and settlement programmes in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, it can be justifiably considered that the strategic depth gained by Israel counts as the most clear-cut and tangible change wrought by the two wars as, simply put, the map of the Middle East in use today was in many ways drawn on the battlefields of 1967.

Despite all this however, it would be wrong to consider that the strategic consequences of the two wars were purely cartographic. The geo-political consequences were as far-reaching as they were varied and should be examined to give us a greater picture of the effect that 1967 and 1973 had. Whilst all the changes cannot be properly covered in this essay, the three main ones – Israeli relative strength, the issue of the Palestinians and the Lebanese Civil War – can be discussed in relation to the Six Day and Yom Kippur Wars and the effect they may have had. Looking at Israeli relative strength, it is understandable that the strategic depth gained by Israel in the 1967 war had a massive effect on Israel’s regional power. However, territory does not automatically equal power and similarly Israel’s post 1967 dominance in the Middle East was resultant of more than its geographical expansion. The comprehensive beating meted out by the IDF upon its three Arab counterparts (Syria, Jordan and Egypt) put Israel ‘in a stronger position than ever’ [8] . This, linked in with ever increasing US support and the physical security of strategic depth made Israel ‘the decisive military power in the Middle East’ which, despite some set-backs (for example in 1973) has never really been changed, and Israel both can and does act unilaterally to protect its interests.

This brings us neatly towards the next geo-political issue to discuss – the Palestinian question. The occupation of such a vast area meant that Israelis were ‘now faced with the problem or administering a large Arab population’ [9] . The conquest of the territories can therefore be considered to be a ‘poisoned chalice’, as through the creation of its ‘mini-empire’ Israel had won more territory –but now had to keep it [10] . This has required Israel’s ‘sword’ (i.e. its military machine) to become ‘ever heavier, ever blunter’ [11] to retain control of the regions it had taken and to pre-empt any external threats the may foment unrest in those regions.

The latter part is best shown in the Lebanese Civil War. The peace accords signed between Israel and Egypt post 1973 largely fractured the ideal of Pan-Arabism and allowed Israel to pursue any ‘police action’ that it felt necessary (within reason) [12] to protect its national integrity. This integrity was under threat due to the instability in Lebanon – which again partly came about as a result of the wars of 1967 and 1973. Following the Yom Kippur War, due to agreement with Israel, Jordan moved to expel elements of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) that were attacking Israeli targets from camps within Jordan. This was achieved, albeit with substantial bloodshed, and PLO duly relocated to just outside Beirut, ‘further destabilising the fragile Lebanese government’ [13] . Therefore when the IDF intervened in 1982 it would be valid to suggest that they were limiting a war of their own making. These events combined with the previous two are good examples of the vast geo-political changes that were created by the two wars and the indirect effect they could have. Israel became more powerful but correspondingly more responsible. It can be said then that 1967 and 1973 made Israel the dominant single power in the Middle East, with all the prestige, responsibility and problems that came with it.

The next area of analysis to be considered is the psychological consequences of the wars – which were inevitably both political and strategic also when considered in sufficient depth. The analysis can be divided along broadly national lines in this context – i.e. the consequences for the Israelis first can be looked at first the Arabs’ in subsequent comparison. The Israeli mindset post 1967 and 1973 could not have been more different. The Six Day War was a crushing Israeli victory, made more spectacular by the fact that a coalition of three Arab nations (whose manpower nominally overwhelmed the IDF) could not even challenge their Jewish foe. The country became ‘overrun by euphoria and a sense of having broken the noose that encircled it’ [14] ; for many of the Jews of Israel it was thus seen as a vindication of their national rights, and nothing short of a miracle. As mentioned above, vast swathes of previously Arab territory were conquered – including most importantly for this point ‘the whole Jerusalem area, including the Arab Old City’ [15] . The capture of this most symbolic of cities (including one of the most sacred sites in Judaism, the Western Wall) was seen as a religious as well as national triumph – that Israel, in every sense of the word, was whole again.

However, this ‘bright and glorious page in Israeli history [16] was short lived and in many ways culpable for its own downfall. The victory of 1967 was so overwhelming and conclusive that the offensive strategy that had served so well during the Six Days was dropped, and ‘gave way to a defensive posture – and hubris’ [17] . As P. R. Kumaraswamy argues ‘the political military echelon of Israel was overconfident of its military prowess and intelligence capabilities’ [18] . In the so-called War of Attrition between 1967 and 1973 the IDF became ’trapped by the concept that the Arabs were not ready for a war’ [19] . Thus the ‘disillusionment of 1973’ [20] came to pass. Even though the war could be considered at worst a draw for the Jewish side, ‘the coordinated Arab effort to breach the 1967 ceasefire line still haunts many (Israelis)’ [21] . It is perhaps just to consider that since the Six Day War was such a conclusive Israeli victory that anything less in 1973 could and was considered a defeat, at least in relative terms. What it meant in real terms however was that the country that emerged from the 1973 war ‘was a different nation: sober, mellowed, scarred in many lasting ways’ [22] . Despite the strategic depth won in 1967 not being severely threatened, the feelings of vulnerability and being surrounded were once again thrust to the forefront of the Israeli mindset, greatly amending their attitude towards their Arab counterparts in several lasting ways.

From this point the psychological consequences for the Arab participants of the two wars can be placed in contrast. This was predictably roughly opposite to the Israeli psyche in relation to the two wars – with a few crucial differences. The rout of 1967 was unarguably a humiliation for the Arab peoples. Inflammatory rhetoric on Arab national radio stations – such as Egypt’s Sawt al-‘arab (Voice of the Arabs) proclaimed easy Arab victories (even when the Arab armies were fleeing) and the shock of reality did not sit well with the Arab peoples and their leaders. However, this only ‘increased their public defiance’ [23] as, in Arab eyes, the problem was not resolved sufficiently – their means had simply been insufficient to achieve victory. They acted to rapidly improve their armed forces (extensively helped by the USSR) and, once the first policy started to take effect, tried to initiate a favourable war to put them back on level pegging with Israel. This duly happened in 1973 – and, from a Syrian-Egyptian perspective – could not have gone much better. The war ‘redeemed Arab self-esteem’ [24] and, in both Israeli and Arab eyes, once again radically altered the balance of power in the Middle East. The Arabs had matched the previously seemingly invincible IDF, and Israel could no longer afford to ignore their demands. This is best seen in the subsequent bilateral peace between Israel and Egypt – the so-called Camp David Accords – where Egyptian President Anwar Sadat successfully ‘extricated his country, and by consequence much of the Arab world from its fateful encounter with the Jewish state’ [25] . Thus it can be seen that the two wars of 1967 and 1973 as representing two extremes for the Arab nations, with the despair and defiance of the Six Days War giving way to the pride and feelings of reinstated equality given by the Yom Kippur conflict.

Accordingly the final segment of this essay’s argument is reached, which concerns the international consequences of the two wars. Like the previous two areas, this strand is also divided into two areas – Cold War conflicts and continuing American interests. Initially by looking at the Cold War aspect of the argument then it is clear that the alliance system that supported Israel so crucially throughout the Cold War underwent substantial flux in response to the various ‘strategic cross-currents that … beset the Middle East’ [26] . Despite the seemingly ubiquitous support given to the Jewish state by Washington today, the Israel in ‘its early years received only limited US support’ [27] . The main ally during the early Cold War was instead France, which was ‘relied upon heavily for diplomatic and military support’ [28] in the pre-1967 era – as seen in the Franco-Israeli collaboration during the 1956 Suez Crisis. However, the seemingly unprovoked attack by the Israelis in the 1967 war (despite President de Gaulle’s explicit warning not to act) led to a diplomatic schism between the two nations and a gap that America was willing to fill. This was not an immediate occurrence. Collaboration had been going on since the early 1960’s, as Israel proved to be a ‘significant source of foreign intelligence’ [29] useful to the US, which duly reciprocated by providing arms of an ‘entirely new level of in terms of quality and quantity’ for the Jewish state. The bi-polar world of the Cold War was unlikely to allow US political investment in the region without eliciting a Soviet response, which duly occurred following the emergent hegemony of Israel post 1967. Soviet influence with the Arabs ‘increased with defeat’ [30] as they sought to resurrect their nominal proxies. This increased priority led in a short time to the point where ‘Egypt and Syria were being supplied on a level far exceeding anything seen prior to 1967’ [31] . Thus by 1973 and the period afterwards the Cold War was effectively imported into the Middle East – best shown by the fact that during the conflict itself ‘the United States and the Soviet Union both actively resupplied their clients and rattled their sabres at each other’ [32] . It could reasonably be argued therefore that these two wars firmly gave this aspect of Middle Eastern politics a ‘Cold War character’ [33] by bringing in superpower interests and therefore rivalry directly into the respective sides of the existing local conflict, thus exacerbating the importance of the narrative in subsequent diplomacy.

Finally the other aspect of this argument strand can be considered – American continuing interests. Whilst chronologically there is obviously some overlap with the previous section, there are two key issues that are distinctly American which can be assessed in this separate context. Firstly, the wars put Israel ‘in a stronger position than ever, backed by Western states and much of Western public opinion’ [34] ; the heroic victory of an embattled under-dog resonated with the US people. Contemporary American identity as a ‘New Jerusalem’ [35] has firmly bonded these two nations together, and whilst 1967 and 1973 did not begin this inclination, they certainly more firmly tied the two nations together in a partly collective destiny. Linked in with this is a slightly more infamous issue – oil. It is convincingly argued that ‘during the 1967 war the Gulf States started to use oil prices and boycott as major weapons against the West’ [36] . The Suez Canal was closed and the flow of oil severely hampered, consequently showing America the ‘significant leverage the Arab states held over their oil-dependent economy’ [37] and it could thus be argued that increased American interest following 1967 was as much an effort to secure the oil stability as it was to pursue the political. This ‘fundamental restructuring between the OPEC and the West’ [38] can and has been extrapolated in the decades since the wars of 1967 and 1973, with many interpretations ranging from the Marxist to the cynic construing the US emphasis on the Middle East as centred purely on the security of the oil there. Regardless of viewpoint the importance of Middle Eastern oil to the American economy is undeniable and in relation to the question is a major strategic consequence, as American interests greater than the integrity of Israel have been another defining force in the Middle East peace process that cannot legitimately be ignored.

Consequentially, it is obvious that there are many varied issues to consider when identifying the primary strategic and political consequences of the 1967 and 1973 wars. This essay has tried to distil the major ones from a wide array of sources and analyse them to gain the best possible outlook of these two events. However, there is an interesting note to attach to the sources used concerning their provenance. A surprising amount of the relevant literature in circulation is by American, British or Israeli authors – or in the case of some (such as P. R. Kumaraswamy) those educated at Israeli institutions. Whilst it is not implied that this automatically devaluates the sources it is nevertheless an interesting point to consider that when analysing the Arab-Israeli conflict the Arab intellectual voice is much more underrepresented than its Israeli counterpart. Separate to that however the sources are generally sound and more than adequate for the task. It is difficult to look at the Six Days War and the Yom Kippur War as separate events due to the massive and inherent links between them, the final analysis should be done collectively. This ‘fault-line’ conflict, despite being one of many in the Middle-East and of course the world at large has become one of the most serious and lasting confrontations that exist today. The events of 1967 and 1973 by no means started this conflict or in any way moved them closer to ending. However, their importance should not be underestimated. The key issues – for example Israeli security, the Palestinian issue, American involvement etc. – were all created or brought to the forefront by one or both of these wars. These issues at the same time increased the importance of the conflict on the international agenda and made them ever more difficult to solve. In a sentence, the 1967 and 1973 wars made the Israeli-Arab conflict what it is today, and are therefore unavoidable when trying to understand this iconic, symbolic and consistently intractable subject.

Bibliography

O’Ballance, Edgar – The Third Arab-Israel War (1972)

Bull, General Odd – War and Peace in the Middle-East (1973)

Fawcett, Louise – International Relations of the Middle East (2005)

Halliday, Fred – The Middle East in International Relations (2005)

Smith, Charles D. – Palestine and the Arab Israeli Conflict: A History with Documents (2007)

Milton-Edwards, Beverley and Hinchcliffe, Peter – Conflicts in the Middle East Since 1945 (2004)

Kumaraswamy, P. R. – Revisiting the Yom Kippur War (2000)

La Guardia, Anton – Holy Land, Unholy War (2007)

Lesch, Ann M. – Origins and Development of the Arab-Israeli Conflict (2006)

Rabi, Uzi (ed.) International Intervention in Local Conflicts (2010)

[1] P8 Milton-Edwards, Beverley and Peter Hinchcliffe Conflicts in the Middle East since 1945 (2004)

[2] P272 O’Ballance, Edgar The Third Arab-Israeli War (1967)

[3] P16 Milton-Edwards, Beverley and Peter Hinchcliffe (2004)

[4] P102 Lesch, Ann M. Origins and Development of the Arab-Israeli Conflict (2006)

[5] P138 LaGuardia, Anton Holy Land, Unholy War (2007)

[7] P228 Smith, Charles in Louise Fawcett (ed.) International Relations of the Middle East (2005)

[8] P116 Halliday, Fred The Middle East in International Relations (2005)

[9] P272 O’Ballance, Edgar (1972)

[10] P137 LaGuardia, Anton (2007)

[12] P230, Smith, Charles in Louse Fawcett (2005)

[14] Smith, Charles D. Palestine and the Arab Conflict: A History with Documents (2007)

[15] P122 Bull, General Odd War and Peace in the Middle East (1973)

[16] P279 O’Ballance, Edgar (1972)

[17] P138 LaGuardia, Anton (2007)

[18] P3 Kumaraswamy, P.R. Revisiting the Yom Kippur War (2000)

[19] P139 LaGuardia, Anton (2007)

[21] P238 Kumaraswamy P.R. (2000)

[23] P138 LaGuardia Anton (2007)

[24] Karsh, Efraim (preface) in Kumaraswamy, P. R. (2000)

[26] P97 Halliday, Fred (2005)

[27] P97 Lieber, Robert in Rabi, Uzi International Intervention in Local Conflicts (2010)

[28] P268 O’Ballance, Edgar (1972)

[29] P98 Lieber, Rober in Rabi, Uzi (2010)

[30] P278 O’Ballance, Edgar (1972)

[31] P125 Bull, General Odd (1973)

[32] P141 LaGuardia, Anton (2007)

[33] P174 Halliday, Fred (2005)

[34] P116 Halliday, Fred (2005)

[36] P16 Milton-Edwards, Beverley and Peter Hinchcliffe (2004)

Written by: Harry Booty Written at: Kings College London Written for: Dr Peter Busch Date written: January 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Historical Institutionalism Meets IR: Explaining Patterns in EU Defence Spending

- The Implications of Stabilisation Logic in UN Peacekeeping: The Context of MINUSMA

- Analysing the ‘Special Relationship’ between the US and UK in a Transatlantic Context

- The Nuclear Weapons Anachronism: A Historical Perspective

- Challenging Historical and Contemporary Notions of Blackness in British Writing

- Identity and Turkish Foreign Policy in the AK Parti Era

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

Israel’s new Yom Kippur

- October 11, 2023

Ahron Bregman

For Israelis, the October 1973 national trauma is being revisited in October 2023.

/https%3A%2F%2Fengelsbergideas.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F10%2FYom-Kippur-War-1.jpg)

October, in the mind of many Israelis, is associated with the Yom Kippur War and regarded as a cursed month. It was in October 1973 that the armies of Egypt and Syria invaded the Sinai and Golan Heights, lands Israel had seized in 1967, catching the Israelis by surprise and off guard on their Day of Atonement. In the South, 100,000 Egyptian troops crossed the Suez Canal in small dinghies, used water jets to make massive holes in the Israeli Bar-Lev line of defence, breached it, and advanced into the desert. Facing them, on the Israeli side, inside the Bar-Lev line, were only 452 troops. In the north, Syrian troops moved deep into the occupied Golan and seized one third of it from the overwhelmed Israelis. The fiftieth anniversary of the October 1973 Yom Kippur War coincides with the current catastrophic event in Israel, which is still unfolding, in which Hamas , the militant Palestinian Islamist movement that rules the Gaza Strip, launched a massive commando military strike, catching the Israelis, just as in 1973, unprepared and off guard. The date of the attack is not accidental. For Israelis, the October 1973 national trauma is being revisited in October 2023.

The Palestinian attackers emerged from the Gaza Strip. Wedged between Israel and the Mediterranean Sea, the Gaza Strip is relatively small: forty kilometres long and between 6.4 and twelve kilometres wide. As a consequence of the 1948 War between Israel and its Arab neighbours, a massive influx of Palestinian refugees moved into the area which radically altered the composition of the Strip’s population. Up until 1948 the dominant people in the Gaza area were the indigenous Gazans, totalling around 80,000 and led by a small but wealthy elite of landowning families. But the arrival of 200,000 refugees fleeing the war in Palestine, transformed this reality overnight; the newcomers settled in makeshift camps, often in the orchards dotted around Gaza. During that war, Egyptian forces moved into the Gaza Strip, occupied it, and imposed a military regime.

In the post-1948 War, the Strip became a source of trouble for the Israelis, as fedayeen , Palestinian guerrillas, emerged from among the newly arrived refugees, crossed into Israel, and attacked its people, mainly in the small villages adjacent to the Strip. Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion , said on one occasion that he wished the Gaza Strip would ‘disappear under the sea’.

On the eve of the 1967 Six-Day War, the Israeli Defence Minister, Moshe Dayan, instructed his military forces that they should not occupy the Gaza Strip from the Egyptians, as the place is ‘bristled with problems… a nest of wasps’. It is a place which Israel must not occupy, he warned, if it did not want to get stuck with a quarter of million Palestinian refugees. Overlooking Dayan’s instructions, Israeli forces occupied the Gaza Strip anyway. For the next 38 years, Israel stayed in the Strip, building settlements, setting up military bases, and imposing military rule on the area and its people.

The Oslo Peace Process in the 1990s between Israel and Palestinian leadership, then under Yasser Arafat of the Fatah faction, led to partial Israeli withdrawal from the Strip. In 2005, when the Israeli-Palestinian peace talks stalled, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon decided that the presence of some 8,000 Jewish settlers in the Strip, squeezed among 1.8 million hostile Palestinians, was untenable and he decided to pull out, unilaterally, from Gaza. After the Israelis left, Hamas, helped by Iran, armed itself to the teeth and, in 2006 it won local elections, kicked out the remaining Fatah officials and started ruling the Gaza Strip. Officially, and like many other nations, Israel continued to regard Hamas as a terrorist organisation, but, on the ground, it accepted it and even strengthened it so that it could efficiently compete with the Fatah leadership. Playing one branch of the Palestinian movement against the other, went the Israeli thinking, could weaken the Palestinian movement, and prevent it from establishing a Palestinian state. While Israel and Hamas would clash every now and then, Israel never attempted to topple the organisation, fearing that without Hamas in power there would be chaos in Gaza, and Israel might have to return to rule the place from where it withdrew in 2005.

Over time, however, Hamas became restless. Israeli troops were no longer physically on the ground in the Strip, but Palestinian life had been totally dependent on Israeli goodwill – if Israel wanted to turn off the lights in Gaza, then they could just switch them off. If Israel wanted to stop labourers from Gaza getting into Israel, all they had to do was to keep the gates into Israel shut, which in turn would negatively affect the Strip’s economy leading to Palestinian criticism of the Hamas leadership.

Also, in competition with Palestinian leadership on the West Bank, Hamas was keen to impress on fellow Palestinians that Hamas did more than the West Bank leadership to fight the Israeli occupation. Fighting the Israelis, however, was not an easy matter. Hamas had long used rockets as a means of taking the war to Israel, but their impact was neutralised by the Iron Dome , an effective defence system invented by the Israelis which could intercept Hamas’s rockets.

Additionally, reports of US attempts to broker a peace deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia concerned Hamas, as they felt they were being abandoned by Arab governments; so, went Hamas’ thinking, if it attacked Israel and the latter responded and killed many innocent Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, then the Saudis would find it difficult to sign with Israel.

As for Israel: the current Netanyahu government, the most extreme in Israel’s history, with militant settlers holding key governmental positions, added to Hamas’s frustration by accelerating the building of settlements in Palestinian areas on the West Bank. Disruptive members of the Netanyahu government, notably the two settlers, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and Internal Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, had been busy aggravating relations with the Palestinians.

Finally, Hamas could see a recent divide in Israeli society, as the Netanyahu government attempted to bring in reforms which could reduce the power of the judiciary. This, in turn, led to massive demonstrations in Israel and open declarations by military reservists that they would refuse to serve in the military if the government proceeded with the reforms.

These elements, namely Palestinian frustrations, competition between different Palestinian factions, and the perception within Hamas that Israel was vulnerable, led to its decision to launch its largest surprise attack in decades.

More than 1,500 Hamas gunmen crossed into Israel by sea and air, but their main thrust was on land. They brought in bulldozers and flattened parts of the sophisticated six-metre-high fence, which was equipped with electronic sensors and other advanced devices that Israel had built, at huge expense, around the Gaza Strip. Israel boasted that their fence was impenetrable, but like the Bar-Lev line of defence which collapsed in 1973, it was easily breached where attacked by Hamas. Using GPS and riding on motorbikes and trucks, well-trained Hamas commando gunmen rode the short distance into 22 Israeli villages, towns, and army bases.

This military operation was not one carried out on the spur of the moment. It was hatched over months, in great secrecy and probably with Iranian support . Hamas copied the Hezbollah plan which was aimed at crossing the Lebanese border with Israel, entering Israeli settlements, and taking civilian prisoners. Israel knew about the Hezbollah plan and prepared itself for such an eventuality, but no such preparations were done in the south, as it never occurred to the Israelis that Hamas might adopt Hezbollah’s plan.

When the gunmen reached their targets, they broke into houses, dragged inhabitants out into the streets and shot them in cold blood. On some occasions, when Israelis locked themselves up inside their houses to protect themselves, the gunmen forced them out by setting their houses on fire. The militants also reached the site of a desert music festival, where hundreds of youths had gathered to celebrate, ambushed them, and killed at least 260 with gun fire and hand grenades. On this tragic day – 7 October – more than 1000 Israelis were killed and 3,000 injured; Hamas and Islamic Jihad, another Palestinian militant organization, also abducted into the Gaza Strip more than 130 Israelis – children, women, men – which they would keep as bargaining cards to negotiate with Israel a future release of Palestinian prisoners locked up in Israeli jails.

In the Yom Kippur War, as is the case now, the Israelis had enough intelligence indicating that the enemy was planning an attack; neither in 1973, nor in 2023 was there any lack of information. In both cases, however, a set of beliefs – ‘conceptions’, as it is known in Israel – led the Israelis to ignore the hard facts and stick to a false set of beliefs. In 1973, it was that the Arabs were as bad at fighting as they had been in 1967, and that if they did attack then the IDF could easily stop them. In 2023, the Israeli held that Hamas did not want war, it was not strong enough, and if only Israel allowed more Palestinian labourers to take up jobs in Israel, then this would calm Hamas down. In both cases Israel got it wrong.

What compounded the Israeli catastrophic intelligence failure was the fact that, when Hamas did attack, there was hardly any significant Israeli force to stop it. As in 1973, the line of defence was much too thin, since, not expecting a Hamas attack, the military command diverted troops to the West Bank to protect Jewish settlers and their illegal settlements and separate Palestinian from extremist Jewish groups stirring up trouble in the West Bank. Worse still, the IDF has a special commando brigade composed of special units – Duvdevan, Egoz, Maglan – whose mission is to move fast by helicopters to reinforce existing forces during surprise attacks; for some reason these forces failed to arrive on time to tackle the invading Hamas gunmen. The Israeli victims begged and screamed for help, sending urgent messages to the authorities on social media calling for the military to come rescue them, but the army was nowhere to be seen.

Clearly, when the dust settles, these catastrophic intelligence and operational failures will be properly investigated and probably be put right, and lessons will be learned. But no investigation could erase the national trauma which is now added to the list of past Jewish and Israeli traumas.

I was nine years old, growing up in Israel, when it occupied the Gaza Strip, and other Arab lands, in just six days in June 1967, and I can still remember the euphoria of the great military victory. Six years later, on 6 October 1973, at two o’clock in the afternoon, the 1967 euphoria crashed to the ground when Arab armies invaded the Sinai and Golan. I will never forget the appearance of Defence Minister, Moshe Dayan, on our black-and-white TV screen: defeated, his head bowed and his voice trembling, he told us that our troops at the two fronts were fighting an invading enemy and that ‘we are fighting for our lives’. In subsequent years, the Yom Kippur trauma continued to deeply affect our collective life, as losing close to 3,000 young men touched upon every corner of the then small Israeli community.

Now, fifty years later, a new trauma has emerged, far worse than Yom Kippur. In 1973, despite the failure at the opening phase of the war, Israeli forces, when fully mobilised, managed to hit hard at the invading forces, crossing the Suez Canal into Africa, stopping 101 kilometres from Cairo and also pushing the Syrians back. The fighting itself was far away from home, taking place in the Sinai desert and on the Golan Heights, occupied areas, but not part of sovereign Israel. By contrast, the current incident took place on Israeli territory and inside Israeli villages and towns; the last time the enemy entered Israeli villages was back in the 1948 War of Independence. To see Hamas gunmen walking freely inside Israeli residential areas, smoking, joking, dragging women and children, young and old from their homes and shooting them in cold blood, are horrific sights. The images emerging from the killing fields in which 260 young Israelis were shot by guns fire while celebrating in a desert music festival are almost impossible to watch. And then the heart breaking story of a young Israeli lady who opened her Facebook page only to find a clip of her grandmother in a pool of blood. It emerges that the Hamas gunman who shot her, took her phone, filmed her dying, and then uploaded the clip to Facebook. Such horrific stories of death and survival keep coming. This helplessness of Israeli citizens who, for years, trusted the IDF to protect them in such eventualities is difficult to comprehend. My 92-year-old mother who has lived through all of Israel’s wars from 1948 to now keeps asking me, ‘Where are our troops? Where is the IDF which has always protected us?’

Israel is a nation in mourning. Anger, panic, fear, and bewilderment combine with horrific pictures of the dead and injured, circulating by social media, to create a trauma which will linger and continue to haunt, not only the families of the dead, injured and abducted, but the whole nation.

Israel will hit back – and hard. It has got to do so. A nation cannot afford to lose hundreds of its citizens in a single day and do nothing about it. A nation which strives to live in the sometimes-difficult Middle East cannot afford to show weakness or allow such breach of its sovereignty. Even given a reality of injustice and suffering of Palestinians, the brutal killing which we have just witnessed is totally unacceptable in a civilized world. ‘Hitting back’ in a Middle Eastern context always has in it the eye-for-an-eye element, a sort of an undeclared revenge for wrongdoing. But, for Israel, hitting back is also necessary in order to deter other enemies, notably Hezbollah, whose combatants, riding on motorbikes, constantly patrol the Israeli-Lebanese border where Israeli villages are adjacent to the border-fence. Hezbollah might try to repeat the successful Hamas attack.

But will the Israeli government, now leading a shaken nation, be able to resist overdoing it? After 9/11 , the Bush administration hit hard at Afghanistan and then went after Saddam Hussein of Iraq, which resulted in American troops getting stuck in a terrible, senseless war in Iraq from where they only withdrew after more than seven years, leaving behind a terrible mess.

What does ‘overdoing’ mean for Israel in the current context? An example is imposing siege on the Gaza Strip, cutting off electricity, water, and food. If Israel goes down this route it will, very quickly, lose its international support and outpouring of sympathy. Another example of ‘overdoing it’ would be turning the Gaza Strip into a modern Dresden. The Israeli Air Force is very powerful, equipped with massive one-tonne bombs. If it wants, it could flatten whole neighbourhoods in the Gaza Strip, causing physical damage and also hundreds, perhaps thousands, of casualties. Finally, invading the Strip in order to topple the Hamas regime could be a mistake the Israelis might regret. Getting rid of the brutal Hamas government is perhaps tempting but removing them without handing over the keys to someone else would leave the Gaza Strip in total chaos and be counter-productive for the Israelis. If the Israelis decide to remove Hamas and stay there to run the place, they will have to face 2.2 million hostile Gazans.

Big dilemmas and dramatic moments now face many in the Middle East, particularly Israel. Such events as the ones we are now witnessing are often game-changers, but at this point in time, it is difficult to see the direction of potential changes. One could only hope that some good will emerge from this horrific tragedy. One thing is sure which is that the trauma caused by Hamas’s senseless and brutal attack on innocent civilians in southern Israel is likely to remain on the Israeli psyche for at least as long as the Yom Kippur trauma.

Latest essays

Why machiavelli wrote the prince, georgian nightmare, testament to doomed media, the looming battle for succession in iran.

ESSAY SAUCE

FOR STUDENTS : ALL THE INGREDIENTS OF A GOOD ESSAY

Essay: The Yom Kippur War

Essay details and download:.

- Subject area(s): History essays

- Reading time: 6 minutes

- Price: Free download

- Published: 19 September 2015*

- File format: Text

- Words: 1,706 (approx)

- Number of pages: 7 (approx)

Text preview of this essay:

This page of the essay has 1,706 words. Download the full version above.

The Yom Kippur War resulted in a large shift in regional balance of power, allowing for peaceful negotiations and a coalition between Arab states to start. Before the war there had been limited support in Egypt for peace and a general reluctance to negotiate peace after the crushing defeat in the 1967 war. Benjamin Lai, Israeli historian stated in 2004 that ‘Egypt had felt in a position of weakness and feared that any settlement would be entirely dictated by Israel’ (Lai, 2004, p221). This would make it impossible for Anwar Sadat, Egyptian President, to make serious efforts towards peace. Prior to the war, Egypt was in no position to discuss any political or peace matters with Israel. Many ‘New Historians’, including Josiah Ginat, Israeli historian, are of the opinion, that ‘the depth of Egypt’s sense of humiliation required a military achievement to make it possible for [him] to offer peace’ (Rubin, Ginat, Ma’oz, 1994, p35). This view is endorsed by how two years before the Yom Kippur war, Sadat’s peace initiative was rejected by Israel (Rubin, 1994). By contrast success in the Yom Kippur war was seen as restoring Arab honour, resulting in an almost unanimous international support for peace. Subsequently peace negotiations could begin between Egypt and Israel, leading to the 1978 Camp David Accords. Moreover, one of the most significant indications of a shift in power caused by the war is that the Israeli leadership felt that, after the Yom Kippur war, political settlements were now necessary to avoid future wars. Rather than being a decision where Israel had the luxury to choose peace or not, after the war Israel was in a weakened position, where they felt there were limited alternatives (Rubin, Ginat, Ma’oz, 1994, p62). Israeli Defence Minister and politician during the Yom Kippur war, Moshe Dayan, substantiated that ‘if [he was] ready to admit one mistake it is the fact that we did not accept Sadat’s initiative in 1971. This could have prevented the war’ (Rubin, Ginat, Ma’oz, 1994, p38). Ultimately Sadat’s increase in power resulting from the war is demonstrated in his ability to pursue peace talks that in prior years had been regarded as a joke. The aftermath of the war left Israel considerably exposed which resulted in countries questioning the validity of the widely accepted myth of Israeli invincibility. Due to previous military successes, Israel had a heightened view of its military capability. The military was complacent, feeling that the Arab states offered no serious threat. Contemporary commentators note that Defence Minister Moshe Dayan believed that ‘the 1967 war was the last of wars’ after which there is nothing left for the Arabs but to plead for mercy'( Badri, Magdoub & Zohdy 1978, p203). This is representative of Israel’s impudent attitude towards the Arab states, which led them to heavily underestimate the force of the Arab army. This was further supported by how in the first few hours of the war, Dayan stated that the war ‘[would] end in a few days with victory’ (Samuel, 1989). Arab success in the initial phases of the war destroyed theories of Israeli military invincibility previously accepted worldwide, particularly after Israeli success in the Six Day War. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a concept took hold that the Arabs were unwilling to go to war against Israel. The concept was based on the idea that the 1967 War was such an overwhelming victory that the Arabs would not be able to overcome Israel for the time being. Despite the fact that Israel was ultimately successful, ending the war on the offensive, and certainly better off than the Arabs, the war nonetheless, ‘came as a blow to the people, they expected something easier and better’ (Embassy of Israel, 1976) as Dayan later stated. This is further corroborated by how US Senator William Fulbright substantiated the view suggesting that ‘Israel was forced to drop the myth of absolute military security as achieved through the occupation of territories’ (Badri, Magdoub & Zohdy 1978). Despite Arab success being mainly in the early stages, when combined with factors of surprise and Israeli lack of preparation, it was felt to be a crushing defeat. It undermined the Israeli aura of invincibility and left Israel feeling vulnerable and weak; hence the war is still held in a very negative light by Israel today. Arab oil producing nations established power in the international community by engaging in an oil embargo. This changed many countries foreign policies to focus on achieving Middle East peace, ultimately to prevent the renewal of the embargo. Indeed, the use of Arab control of oil supplies as a political weapon was one of the most significant consequences of the war. Increasing world oil consumption in the years preceding the war made oil a necessity, ‘essential for the functioning of the modern industrial society’ (p235, Laqueur, 1974). In the 1973 Oil Embargo, the Arab oil producing states cut production by 5% and also refused export to the US and other Western countries, in retaliation for external support to Israel (p29, Lesch, 2006). The Daily News Kuwait stated that, in particular the Arab states aimed ‘to make the United States aware of the exorbitant price the great industrial states [could] pay as a result of the blind and limitless support for Israel’ (Laqueur, 1974). Indeed, the embargo had a huge impact on United States economy, Israeli economist, Hanadi Laqeur states, ‘in the twenty years before the war their energy consumption had doubled’ (Laqueur, 1974), causing an increasing dependence on imported Arab oil. Reduced imports combined with the energy crisis occurring in the US, saw closure of US petrol stations, US houses went without heating, and a general crisis in the petroleum market. The Saudi oil minister told US congressmen in 1974 that ‘when there is a shortage in fuel in the United States and your people begin to suffer – the change will begin’ (Laqueur, 1974). This is representative of how the Arab nations used oil as a political weapon to help bargain with the West. Although the oil embargo did not last long it had huge impacts beyond those felt in the US. Using oil as a weapon enabled the Arabs to gain considerable bargaining power in the broader international community, as evident in other changes that occurred as a result of Arab pressure. For example, Egypt was able to impose its will, and reopen the Suez Canal to international navigation (Israel Embassy, 1976, p39). There were also positive consequences for the Egyptian economy. According to American historian, Christopher Westwood, ‘Prior to 1973 the economy of Egypt was under an almost intolerable strain’ Egypt had become the laughing stock of the Arab world’ (Westwood, 1984, p204). The war brought a radical economic transformation, particularly due to oil revenues. This is further supported by how ‘Israel could claim to be the military victor’ Egypt, Syria and the Arab cause in general were clearly the political victors’ (Westwood, 1984, p148). Ultimately the Arab states emerged as an economic and political power and a forced to be reckoned with on the international scale. The international community now saw the Arab coalition as a threat because the Arab morale was boosted considerably after their initial success of the war. Egypt and Syria went into the war hoping to win back land taken by Israel during the Six Day War, the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights. Despite failing to achieve this goal, the Arab coalition was vindicated for its crushing defeat in the Six Day War of 1967 (Parker, 2001, p 68). For example, Egyptian President, Sadat claimed that through their initial success ‘the Arab armed forces performed a miracle in the war as judged by a military measure’ (Bardi & Magdoub & Zohdy, 1978, p 201). This is relevant because it shows how the Arab coalition were up against a much more experienced and equipped enemy and thus the Arab military was now seen as a threat for their ability to get victory against such an opposition. While the war did not conclude in an Arab military victory, according to New Historians, ‘both the Egyptian and Syrian armies had regained their honour and prestige,’ (Badri, Magdoub & Zohdy, 1978, p20), and so emerged feeling victorious nonetheless. Carefully planned Arab use of the element of surprise was critical here, it being not mere chance that Israel was caught off guard. Rather Egypt and Syria actively deceived Israel, to create false ideas of their capabilities, plans and intentions. In particular ‘they conducted secret negotiations’ released reports that gave misleading ideas on the quality of their military’ and masked troop movements prior to the invasion’ (Lai, 2004, p221). By taking Israel unprepared, the initial invasion, ‘provid[ed] them with unique military advantages’ (Lai, 2004, p 226), and demonstrated that ‘the Syrians and Egyptians could fight just as skilfully as the Israelis’ (Heikal, 1975, p246). Although limited, this success restored the Arab world’s confidence in their military forces and governments, and so marked a turning point for Arab countries in relation to the wider conflict. Egyptian President Sadat stated that ‘the Arab world can rest assured that it has now both a shield and a sword.’ (Badri, Magdoub & Zohdy 1978, p201), and also that, ‘now the Israeli soldier is fleeing before the Egyptian solider. It is not only a great triumph for Egypt but has enormous significance outside Egypt’ (Tamir, 1988, p167). This is representative of the unity and solidarity now felt by the Arab countries and is further endorsed by Azir Chahoud, an Arab diplomat in 1974, ‘We may never be unanimous and we will probably never speak in one voice,’ one Arab diplomat said, ‘but for the first time we are now speaking in different accents against a common background with a few exceptions for a common goal.’ As a result of the Yom Kippur War the Arab military’s morale was boosted and thus the international community now saw the Arab coalition as a threat. Ultimately, the repercussions and major developments flowing from the Yom Kippur war were felt in the Middle East and beyond. The most significant consequences of the war included helping to set the stage for peace negotiations between Egypt and Israel and contributing to some progress towards achieving peace in the Middle East, the destruction of the myth of Israeli invincibility, morale was boosted and the oil embargo’s international impacts redefined the strength of Arab positions in significant aspects of international relations.

...(download the rest of the essay above)

About this essay:

If you use part of this page in your own work, you need to provide a citation, as follows:

Essay Sauce, The Yom Kippur War . Available from:<https://www.essaysauce.com/history-essays/essay-the-yom-kippur-war/> [Accessed 27-05-24].

These History essays have been submitted to us by students in order to help you with your studies.

* This essay may have been previously published on Essay.uk.com at an earlier date.

Essay Categories:

- Accounting essays

- Architecture essays

- Business essays

- Computer science essays

- Criminology essays

- Economics essays

- Education essays

- Engineering essays

- English language essays

- Environmental studies essays

- Essay examples

- Finance essays

- Geography essays

- Health essays

- History essays

- Hospitality and tourism essays

- Human rights essays

- Information technology essays

- International relations

- Leadership essays

- Linguistics essays

- Literature essays

- Management essays

- Marketing essays

- Mathematics essays

- Media essays

- Medicine essays

- Military essays

- Miscellaneous essays

- Music Essays

- Nursing essays

- Philosophy essays

- Photography and arts essays

- Politics essays

- Project management essays

- Psychology essays

- Religious studies and theology essays

- Sample essays

- Science essays

- Social work essays

- Sociology essays

- Sports essays

- Types of essay

- Zoology essays

Adrienne Rich

Yom kippur 1984.

#AmericanWriters

Other works by Adrienne Rich...

Your breasts/—sliced-off—The scar… dimmed—as they would have to be years later All the women I grew up with are… half-naked on rocks—in sun

No one’s fated or doomed to love a… The accidents happen, we’re not he… they happen in our lives like car… books that change us, neighborhood… we move into and come to love.

Our whole life a translation the permissible fibs and now a knot of lies eating at itself to get undone Words bitten thru words

Good-by to you whom I shall see t… Next year and when I’m fifty; sti… This is the leave we never really… If you were dead or gone to live i… The event might draw your stature…

If I lay on that beach with you white, empty, pure green water war… and lying on that beach we could n… because the wind drove fine sand a… as if it were against us

A woman in the shape of a monster a monster in the shape of a woman the skies are full of them a woman ‘in the snow among the Clocks and instruments

The dark lintels, the blue and for… of the great round rippled by ston… the midsummer night light rising f… the horizon—when I said “a cleft o… I meant this. And this is not Sto…

I am walking rapidly through stria… I am a woman in the prime of life,… and those powers severely limited by authorities whose faces I rarel… I am a woman in the prime of life

Miracle’s truck comes down the lit… Scott Joplin ragtime strewn behin… and, yes, you can feel happy with one piece of your heart. Take what’s still given: in a room…

I come home from you through the e… flashing off ordinary walls, the P… the Discount Wares, the shoe-stor… of groceries, I dash for the eleva… where a man, taut, elderly, carefu…

Either you will go through this door or you will not go through. If you go through there is always the risk

What kind of beast would turn its… What atonement is this all about? —and yet, writing words like these… Is all this close to the wolverine… that modulated cantata of the wild…

Whatever happens with us, your bod… will haunt mine—tender, delicate your lovemaking, like the half-cur… of the fiddlehead fern in forests just washed by sun. Your traveled,…

Can it be growing colder when I b… to touch myself again, adhesions p… When slowly the naked face turns f… and looks into the present, the eye of winter, city, anger, po…

Wherever in this city, screens fli… with pornography, with science-fic… victimized hirelings bending to th… we also have to walk... if simply… through the rainsoaked garbage, th…

The Helpful Tip That Makes Fasting For Yom Kippur A Little Easier

Y om Kippur, the Day of Atonement, holds profound significance in the Jewish faith. It is observed by solemn reflection, repentance, and prayer. One of the central practices during Yom Kippur is fasting, which spans approximately 25 hours, beginning at sundown and concluding after nightfall the following day. Fasting on Yom Kippur symbolizes spiritual cleansing, self-discipline, and humility.

The decision to fast during Yom Kippur is deeply personal, often rooted in religious devotion and a desire to seek forgiveness. While fasting, individuals abstain from consuming both food and drink, refraining from any sustenance for the entire duration of the fast. The physical challenges of fasting, particularly the sensation of hunger, can sometimes detract from the spiritual experience.

One effective method to ease into the fast is by gradually reducing the intake of certain foods before Yom Kippur. Cutting down on caffeine , specifically coffee, and sugary treats in the days leading up to the fast can be beneficial. Caffeine withdrawal can trigger headaches and increased hunger, making the initial hours of fasting more challenging. By tapering off coffee consumption beforehand, the body has time to adjust, potentially reducing the severity of withdrawal symptoms. Similarly, reducing sugar intake can help stabilize blood sugar levels and prevent sudden cravings that could manifest as hunger during the fast.

Read more: 25 Popular Bottled Water Brands, Ranked Worst To Best

Eat Less And Eat Right

Beyond caffeine and sugar cessation, there are strategies that can be employed to help minimize hunger pangs and make the fast more manageable. These tips can't make hunger disappear but can help tone it down so one can focus on the heart of Yom Kippur.

Staying hydrated before the fast begins is crucial. Drink plenty of water in the hours leading up to and during the fast to ensure your body is adequately hydrated. Dehydration can intensify feelings of hunger, so starting the fast well-hydrated can make a significant difference.

You'll also want to avoid overeating in the hours before the fast begins. Consuming a large meal can lead to discomfort and increased hunger as digestion takes place during the initial stages of the fast. Opt for a balanced meal that includes protein, healthy fats, and complex carbohydrates.

Speaking of a balanced meal, it might seem like vegetables, salads, and other high-fiber foods are a good choice to kick off Yom Kippur fasting. But, be cautious as foods rich in fiber can lead to bloating and digestive discomfort, which may exacerbate feelings of hunger. Instead, opt for easily digestible foods that provide sustained energy without causing digestive disturbances.